Abstract

This study aimed to examine whether pulmonary function and cognition are independently associated at multiple time points. We included 8264 participants (49.9% women) aged 50–94 years at baseline from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study in our analysis. Participants were enrolled in 2011 and followed up in 2013 and 2015. Cognitive function was assessed through a face-to-face interview in each survey. Pulmonary function was assessed via peak expiratory flow. Pulmonary function and cognitive function decreased significantly with age in both genders. Individuals in quintile 5 of pulmonary function had a relative increase in immediate memory (β [95% CI]: 0.19 [0.09, 0.30]) and delayed memory (0.16 [0.04, 0.28]) during follow-up compared with those in quintile 1. In the repeated-measures analysis, each standard deviation increment of pulmonary function was associated with a 0.44 (95% CI: 0.34, 0.53), 0.12 (0.09, 0.15), 0.12 (0.08, 0.16), 0.08 (0.06, 0.11), and 0.10 (0.07, 0.14) higher increase in global cognitive score, immediate memory, delayed memory, orientation, and subtraction calculation, respectively. The inverse association between pulmonary function and cognitive decline during follow-up was more evident in women (p for interaction = .0333), low-educated individuals (p for interaction = .0002), or never smokers (p for interaction = .0412). In conclusion, higher baseline pulmonary function was independently associated with a lower rate of cognitive decline in older adults. The positive association between pulmonary function and cognition was stronger in women, lower-educated individuals, or never smokers.

Keywords: Cognitive decline, Memory, Moderation analysis, Pulmonary function

Alois Alzheimer first described dementia in 1906 (1), but it was not until 1999 that the Petersen criteria defined cognitive decline, which is the prelude to dementia (2). The global number of people with dementia was 43.8 million in 2016 (3), with China accounting for approximately one-quarter (4). Although the age-standardized prevalence of dementia worldwide increased by 1.7% from 1990 to 2016, it increased by 5.6% in China during this same period (4). It is imperative to identify modifiable factors for the prevention of dementia and cognitive decline in a rapidly aging global population (5–7).

Many modifiable risk factors including excessive alcohol consumption, obesity, hypertension, smoking, depression, diabetes, social isolation, physical inactivity, and air pollution have been associated with an increased risk of dementia (8). An increasing number of epidemiological and animal studies have shown that exposure to inhaled air pollutants may accelerate neurodegenerative processes through cardiovascular disease, and deposition of the amyloid β-protein (9–11). Poor pulmonary function is of particular interest as a risk factor for cognitive decline, as it is potentially modifiable, both via individual behavioral modification such as smoking cessation (12) and exercise (13) as well as policy changes encouraging air pollution reduction (14). Accumulating research has linked pulmonary function to cognitive function (15,16). Impaired pulmonary function may lessen the supply of oxygen to the brain resulting in ischemic damage through hypoxia, which may cause cognitive decline (17). Impaired pulmonary function and dementia have many shared risk factors, including older age, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, frailty, smoking, socioeconomic deprivation, and physical inactivity (18–23). This also indicates there might be an association between impaired pulmonary function and cognitive decline.

Given the heavy air pollution and its negative consequences on respiratory and all-cause mortality in China (24–26), investigating the association between pulmonary function and cognitive function in Chinese older adults is of great importance. Several longitudinal studies with 3 or more measurement occasions have investigated the association between pulmonary and cognitive function, but these studies are limited by exclusion of some important confounders and small sample sizes, and no such studies have been conducted in China (16). Furthermore, peak expiratory flow (PEF) as the criterion measure of pulmonary function may be a stronger predictor of cognitive function and dementia than other measures. However, its use has only been investigated in a few longitudinal studies (15,16).

The present study, in a nationally representative sample of Chinese older adults, examined whether pulmonary function is predictive of change in cognition in older adults over 4 years. We also examined whether the association between pulmonary function and change in cognition was modified by important factors.

Method

Participants

The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study is a nationally representative longitudinal survey of adults aged 45 years or older initiated in 2011 and followed up in 2013 and 2015 (27). A multistage sampling stratified by region (urban districts and rural counties) and per capita statistics on the gross domestic product was performed to identify participants for study inclusion. A total of 150 district-/county-level units were randomly selected using a probability-proportional-to-size sampling technique from a sampling frame containing all county-level units (except Tibet) in China. A face-to-face computer-assisted personal interview was conducted on 10 257 households from 28 provinces with a response rate of 80.5% at baseline. The participants were then followed up every 2 years.

Of the final sample of 17 708 individual participants who were surveyed at baseline, the following were excluded from the present analysis: those aged less than 50 years (n = 5357), those who had brain disease or memory problems at baseline (n = 508), those who did not have pulmonary function assessed (n = 2573), and those who completed the cognitive assessment at less than 2 surveys (n = 1006). The remaining 8264 participants were included in the final analysis (Supplementary Figure S1).

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Committee at Peking University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Pulmonary Function Assessment

Pulmonary function, in the form of PEF, was measured using a peak flow meter with a disposable mouthpiece (Shanghai Everpure Medical Plastic Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China). Before the test, the investigator demonstrated how the measurement was performed. Participants were asked to stand up, take a deep breath, place lips around the outside of the mouthpiece, and blow as hard and as fast as possible. Three measurements of PEF (L/min) were conducted at 30-second intervals, and the best attempt was used in the analysis. Reasons for not having a complete PEF reading, the extent of effort given to the test (full effort, not full effort because of illness or pain, not full effort with no reason), and position during the test (standing, sitting, or lying down) were recorded. Age- and region-standardized Z-scores of PEF were computed and used in the analysis.

Cognitive Assessment

Cognition was assessed at a face-to-face interview in each wave of the survey (28). The tests (Chinese version) have been validated in a subgroup of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study cohort (29). Four cognitive screening tasks included 1) the immediate and delayed recall of a 10-word list (1 out of 4-word lists was randomly selected), 2) serial 7 subtraction from 100 for 5 times, 3) date orientation, and 4) picture drawing. The total score for immediate recall ranged from 0 to 10 with each correctly recalled word assigned a score of 1; a similar score was assigned for delayed recall. The total score for serial 7 subtraction ranged from 0 to 5 with a score of 1 assigned to each of the 5 subtractions. For date orientation (day, week, month, season, and year), a score of 1 was given to those identified correctly with the total score ranged from 0 to 5. Individuals who were able to correctly redraw a picture of 2 overlapped pentagons shown to them were given a score of 1.

A global cognitive score was computed by summing the scores of all 4 tasks ranging from 0 to 31. The changes in cognitive scores were computed by subtracting the scores at baseline from those at follow-up.

Physical Examination

Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a balance-beam scale. Body mass index was computed as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters.

Confounders

Data on age, gender, education, smoking (never smoked, former smoker, and current smoker), and alcohol consumption (never, <1 drink per month, ≥1 drink per month) were self-reported. Physical activity was assessed based on the duration and frequency spent in different physical activities, from which the metabolic equivalent of task (MET) was calculated (30). MET from moderate and vigorous physical activity was computed by multiplying the length (minutes per week) by an assigned MET value (4 MET for moderate physical activity and 7.5 MET for vigorous physical activity) (30).

Self-reported medical history of lung disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, stroke, heart disease, and psychiatric disorders were also collected. Physical function was assessed by tests scoring functional limitations of the upper and lower body (31,32). Participants were asked whether they had difficulty performing any of the following tasks: running or jogging about 1 km, walking about 1 km, walking about 100 m, getting up from a chair after sitting for a long period, climbing several flights of stairs without resting, stooping, kneeling, or crouching, reaching or extending arms above shoulder level, lifting or carrying weights more than 5 kg, or picking up a small coin from a table. Each task had 4 levels: “No, I don’t have any difficulty,” “I have difficulty but can still do it,” “Yes, I have difficulty and need help,” and “I cannot do it” and the corresponding score was 0, 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The total physical function score was calculated by summing subscores of all tasks with a higher score representing higher physical function limitation.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses, both descriptive tables, and regression models were weighted using individual sample weights. Data were expressed as frequency (percentage) and means ± standard deviations (SDs) for baseline characteristics. Analysis of variance for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables were performed to compare the difference of baseline characteristics across quintiles of pulmonary function.

General linear regression models were used to test the difference in weighted changes in cognitive scores between individuals in different quintiles of pulmonary function at baseline. We tested the following models: (i) age and gender; (ii) Model 1 plus education, region, smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity, physical function, and global cognitive score at baseline; (iii) Model 2 plus height, body mass index, lung disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and psychiatric disorders at baseline.

Repeated-measures generalized estimating equations were used to test the association of pulmonary function with weighted cognitive function over time (33). Three models with the same adjusted covariates mentioned above were tested. We then examined whether the association between pulmonary function and cognitive function over time was modified by age, gender, education, geographic region, smoking, physical function limitation, or lung disease (important determinants for pulmonary function). We also examined the association between variation in performance between trials of the PEF tasks and cognitive decline. The variation was calculated as , where SD and mean were computed based on the PEF of 3 trials at each survey.

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine whether the association of pulmonary function with weighted cognitive function over time persisted in individuals who gave full effort in the pulmonary function assessment.

Data analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc.) and 2-sided p values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 8264 participants (49.9% women) aged 50–94 years (mean ± SD: 61.7 ± 7.5) with complete data on variables of interest were included in the analysis. Individuals excluded from the analysis were more likely to be older, former smokers, and physically inactive, and have a higher prevalence of hypertension, heart disease, stroke, and psychiatric disorders compared with those included in the analysis (Supplementary Table S1). Women and those who had lower education were more likely to have lower PEF. Higher PEF was also associated with higher global cognitive score, memory, subtraction calculation, and orientation at baseline (all p values < .05, Table 1). Higher PEF was associated with a lower prevalence of heart disease, stroke, and lung disease (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics According to Quintiles of Pulmonary Function*

| Pulmonary Function | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1 (n = 1649) | Quintile 2 (n = 1643) | Quintile 3 (n = 1646) | Quintile 4 (n = 1654) | Quintile 5 (n = 1655) | p Value† | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 61.8 (7.3) | 62.5 (7.6) | 61.6 (7.5) | 61.1 (7.2) | 62.5 (7.8) | .91 |

| Age (years), range | 50.0–86.9 | 50.0–90.5 | 50.0–89.9 | 50.0–90.3 | 50.0–94.6 | — |

| Female, n (%) | 848 (51.3) | 822 (50.0) | 823 (49.9) | 832 (50.2) | 790 (47.8) | <.0001 |

| Education, n (%) | <.0001 | |||||

| Illiterate (0 year) | 527 (31.9) | 527 (32.0) | 476 (28.9) | 473 (28.6) | 386 (23.3) | |

| Low (1–9 years) | 757 (45.8) | 736 (44.8) | 730 (44.2) | 699 (42.2) | 707 (42.7) | |

| High (≥10 years) | 370 (22.4) | 380 (23.2) | 442 (26.8) | 482 (29.2) | 561 (33.9) | |

| Rural residents, n (%) | 1029 (62.2) | 1050 (63.9) | 1006 (61.0) | 1044 (63.0) | 1040 (62.8) | <.0001 |

| Non-alcohol drinkers, n (%) | 1102 (66.6) | 1094 (66.5) | 1123 (68.1) | 1092 (66.0) | 1056 (63.7) | <.0001 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 530 (32.1) | 575 (35.0) | 534 (32.4) | 538 (32.5) | 473 (28.6) | <.0001 |

| Physical activity (MET-min/wk), mean (SD) |

1878 (4401) | 1900 (4644) | 2042 (4770) | 1954 (4484) | 1701 (4594) | .38 |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 157.0 (8.5) | 157.2 (8.2) | 157.6 (8.6) | 158.5 (9.4) | 159.9 (9.7) | <.0001 |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 56.6 (11.5) | 57.0 (11.1) | 57.8 (10.9) | 59.6 (11.6) | 62.0 (11.7) | <.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 22.8 (3.9) | 23.0 (3.6) | 23.3 (3.6) | 23.6 (3.7) | 24.1 (3.8) | <.0001 |

| Physical function limitation‡, mean (SD) | 3.70 (4.46) | 3.12 (4.30) | 2.63 (3.75) | 2.29 (3.53) | 2.05 (3.26) | <.0001 |

| Peak expiratory flow (L/min), mean (SD) | 141.7 (52.8) | 226.1 (54.5) | 292.2 (65.4) | 352.7 (74.4) | 438.2 (101.6) | <.0001 |

| Global cognitive score, mean (SD) | 13.98 (5.15) | 14.56 (5.23) | 15.00 (5.26) | 15.50 (5.12) | 16.49 (5.23) | <.0001 |

| Immediate memory, mean (SD) | 3.70 (1.59) | 3.85 (1.56) | 3.98 (1.62) | 4.03 (1.56) | 4.37 (1.69) | <.0001 |

| Delayed memory, mean (SD) | 2.77 (1.81) | 2.91 (1.82) | 3.08 (1.91) | 3.05 (1.89) | 3.33 (1.92) | <.0001 |

| Subtraction calculation, mean (SD) | 2.50 (2.00) | 2.62 (1.99) | 2.72 (1.97) | 2.90 (1.96) | 3.13 (1.94) | <.0001 |

| Date orientation, mean (SD) | 3.56 (1.37) | 3.61 (1.37) | 3.70 (1.33) | 3.89 (1.27) | 4.05 (1.17) | <.0001 |

Notes: ANOVA = analysis of variance; MET = metabolic equivalent of task; SD = standard deviation; BMI = body mass index.

*Pulmonary function was standardized by age and region.

†ANOVA was used to test the difference of continuous variables across quintiles of pulmonary function and chi-square for categorical variables.

‡Physical function limitation score was calculated by summing subscores of all tasks with a higher score representing higher physical function limitation.

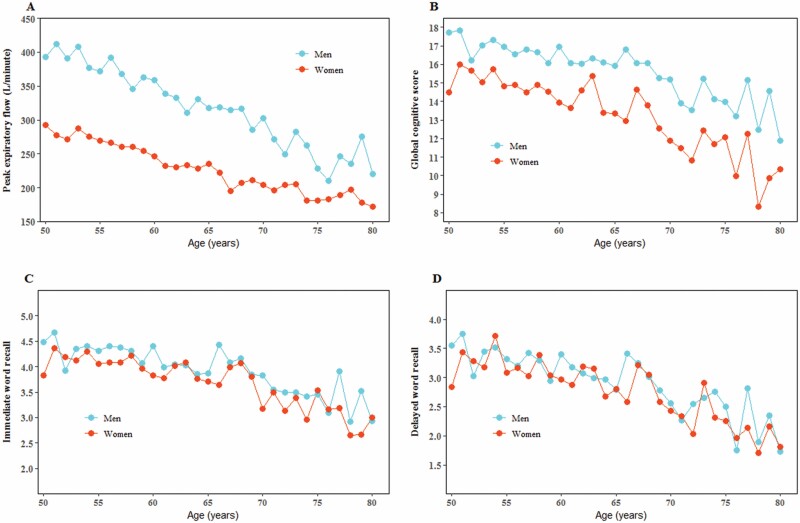

Cognition and Pulmonary Function Changes During Aging

Both global cognitive score and PEF at baseline decreased with age. The average global cognitive score decreased from 17.2 at the age of 50 years to 11.9 at the age of 80 years or older in men, and from 14.5 to 10.3 in women. PEF decreased from 393.3 L/min at age of 50 years to 220.0 L/min at age of 80 years or older in men and from 292.3 L/min to 172.2 L/min in women (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pulmonary function and cognition associated with age.

Pulmonary Function at Baseline and Change in Cognition

PEF at baseline was not significantly associated with the change in global cognitive score. For individual cognition domains, higher pulmonary function at baseline was associated with a relative increase in immediate memory score (β [95% CI] for quintile 5 vs quintile 1: 0.19 [0.09, 0.30]) and delayed (0.16 [0.04, 0.28]) memory score over time but not orientation or subtraction calculation (Table 2).

Table 2.

The Change in Cognitive Scores Associated With Pulmonary Function

| Pulmonary Function | Each SD Increment† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1 | Quintile 2 | Quintile 3 | Quintile 4 | Quintile 5 | p Trend* | ||

| Global cognitive score | |||||||

| Participants | 970 | 945 | 1053 | 1137 | 1180 | ||

| β (95% CI), Model 1‡ | 0 | 0.05 (−0.30, 0.40) | −0.18 (−0.53, 0.17) | −0.19 (−0.53, 0.15) | 0.23 (−0.11, 0.58) | .51 | 0.76 (0.65, 0.87) |

| β (95% CI), Model 2§ | 0 | 0.06 (−0.27, 0.39) | −0.18 (−0.51, 0.15) | −0.07 (−0.40, 0.25) | 0.19 (−0.13, 0.51) | .47 | 0.53 (0.44, 0.62) |

| β (95% CI), Model 3|| | 0 | 0.07 (−0.26, 0.41) | −0.16 (−0.49, 0.17) | −0.09 (−0.42, 0.23) | 0.12 (−0.20, 0.45) | .99 | 0.44 (0.34, 0.53) |

| Immediate memory | |||||||

| Participants | 1310 | 1276 | 1337 | 1405 | 1445 | ||

| β (95% CI), Model 1 | 0 | 0.08 (−0.03, 0.19) | 0.05 (−0.06, 0.16) | 0.11 (0.00, 0.21) | 0.32 (0.21, 0.43) | <.0001 | 0.19 (0.16, 0.22) |

| β (95% CI), Model 2 | 0 | 0.06 (−0.04, 0.17) | 0.03 (−0.08, 0.13) | 0.08 (−0.02, 0.18) | 0.24 (0.14, 0.34) | <.0001 | 0.14 (0.11, 0.17) |

| β (95% CI), Model 3 | 0 | 0.06 (−0.05, 0.16) | 0.01 (−0.10, 0.11) | 0.05 (−0.05, 0.16) | 0.19 (0.09, 0.30) | .0012 | 0.12 (0.09, 0.15) |

| Delayed memory | |||||||

| Participants | 997 | 971 | 1076 | 1159 | 1202 | ||

| β (95% CI), Model 1 | 0 | 0.11 (−0.02, 0.23) | 0.01 (−0.12, 0.13) | 0.05 (−0.07, 0.17) | 0.23 (0.10, 0.35) | .0042 | 0.18 (0.14, 0.22) |

| β (95% CI), Model 2 | 0 | 0.09 (−0.03, 0.21) | 0.00 (−0.12, 0.12) | 0.05 (−0.07, 0.17) | 0.18 (0.06, 0.29) | .0291 | 0.13 (0.10, 0.17) |

| β (95% CI), Model 3 | 0 | 0.10 (−0.03, 0.22) | 0.00 (−0.12, 0.12) | 0.03 (−0.09, 0.15) | 0.16 (0.04, 0.28) | .0718 | 0.12 (0.08, 0.16) |

| Subtraction calculation | |||||||

| Participants | 1630 | 1627 | 1637 | 1650 | 1645 | ||

| β (95% CI), Model 1 | 0 | −0.13 (−0.24, −0.01) | −0.10 (−0.21, 0.02) | −0.08 (−0.20, 0.04) | 0.04 (−0.08, 0.16) | .33 | 0.19 (0.16, 0.23) |

| β (95% CI), Model 2 | 0 | −0.13 (−0.25, −0.02) | −0.12 (−0.24, −0.01) | −0.10 (−0.21, 0.02) | −0.05 (−0.16, 0.07) | .67 | 0.13 (0.10, 0.17) |

| β (95% CI), Model 3 | 0 | −0.13 (−0.25, −0.02) | −0.12 (−0.23, −0.00) | −0.11 (−0.22, 0.01) | −0.08 (−0.19, 0.04) | .30 | 0.10 (0.07, 0.14) |

| Date orientation | |||||||

| Participants | 1655 | 1645 | 1650 | 1657 | 1657 | ||

| β (95% CI), Model 1 | 0 | 0.13 (0.04, 0.21) | 0.16 (0.08, 0.25) | 0.09 (−0.00, 0.17) | 0.15 (0.06, 0.24) | .0100 | 0.16 (0.13, 0.18) |

| β (95% CI), Model 2 | 0 | 0.13 (0.04, 0.21) | 0.15 (0.06, 0.23) | 0.09 (0.01, 0.18) | 0.11 (0.02, 0.19) | .0724 | 0.11 (0.09, 0.13) |

| β (95% CI), Model 3 | 0 | 0.13 (0.04, 0.21) | 0.14 (0.06, 0.23) | 0.07 (−0.01, 0.16) | 0.07 (−0.02, 0.15) | .49 | 0.08 (0.06, 0.11) |

Notes: BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; SD = standard deviation.

*General linear regression models were used to obtain coefficients (β [95% CI]) for the change in cognitive scores for quintiles 2–5 versus the quintile 1 of pulmonary function. Changes in cognitive scores were computed as the scores at baseline subtracting from those at follow-up.

†Repeated-measures generalized estimating equations were used to test cognitive change associated with each SD increment of pulmonary function over time.

‡Model 1 was adjusted for age and gender.

§Model 2 was adjusted for Model 1 plus education, region, smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity, physical function, and global cognitive score at baseline.

||Model 3 was adjusted for Model 2 plus height, BMI, lung disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and psychiatric disorders at baseline.

Repeated-Measures Analysis of the Association Between Pulmonary Function and Cognition at Multiple Time Points

Each SD increment of PEF at baseline was associated with a 0.44 (95% CI: 0.34, 0.53), 0.12 (0.09, 0.15), 0.12 (0.08, 0.16), 0.08 (0.06, 0.11), and 0.10 (0.07, 0.14) higher increase in global cognitive score, immediate memory score, delayed memory score, orientation, and subtraction calculation, respectively (Table 2).

Moderation Analysis

The association between PEF and global cognitive score was modified by gender, education, and smoking. This association, over time, was stronger (p value for interaction = .0333) in women (β [95% CI]: 0.59 [0.44, 0.74]) than in men (0.43 [0.32, 0.53]). It was also stronger (p value for interaction = .0412) in individuals who had never smoked (0.55 [0.42, 0.68]) compared with current smokers (0.38 [0.24, 0.53]) or former smokers (0.33 [0.10, 0.55]). The association between PEF and global cognitive score was significant across education groups, but less evident in those with high education levels (0.37 [0.21, 0.54]) compared to those with low (0.45 [0.24, 0.65]) or moderate education levels (0.52 [0.39, 0.65], Table 3).

Table 3.

Moderation Analysis of the Association Between Pulmonary Function and Cognition

| Participants | β (95% CI)* | p Value | p Interaction† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | .0334 | |||

| Men | 4134 | 0.43 (0.32, 0.53) | <.0001 | |

| Women | 4122 | 0.59 (0.44, 0.74) | <.0001 | |

| Education | .0002 | |||

| Illiterate (0 year) | 2369 | 0.45 (0.24, 0.65) | <.0001 | |

| Low (1–9 years) | 3629 | 0.52 (0.39, 0.65) | <.0001 | |

| High (≥10 years) | 2258 | 0.37 (0.21, 0.54) | <.0001 | |

| Smoking | .0412 | |||

| Current | 2684 | 0.38 (0.24, 0.53) | <.0001 | |

| Former | 778 | 0.33 (0.10, 0.55) | .0043 | |

| Never | 4794 | 0.55 (0.42, 0.68) | <.0001 |

Notes: CI = confidence interval; SD = standard deviation.

*Repeated-measures generalized estimating equations were used to test cognitive change associated with each SD increment of pulmonary function over time.

†We then examined whether the association between pulmonary function and cognitive function over time was modified by age, gender, education, geographic region, smoking, physical function limitation, or lung disease. Stratified analysis was conducted for those with significant interaction.

Variation in Performance Between Trials of PEF and Cognitive Decline

Variation in performance between 3 trials of the PEF at baseline was not significantly associated with the change in cognitive scores. In the repeated-measures analysis, an increase in variation between PEF attempts was associated with a higher decrease in global cognitive score (β [95% CI]: −0.85 [−1.50, −0.19]) and immediate memory (−0.25 [−0.47, −0.03], Supplementary Table S3).

Sensitivity Analysis

The analysis, repeated in individuals who gave full effort in their PEF attempts, showed that each SD increment of PEF was associated with a 0.44 (95% CI: 0.33, 0.55), 0.12 (0.09, 0.16), 0.10 (0.06, 0.14), 0.10 (0.08, 0.13), and 0.10 (0.06, 0.15) higher increase in global cognitive score, immediate memory score, delayed memory score, orientation, and subtraction calculation, respectively (Supplementary Table S4).

Discussion

In this nationwide longitudinal study of older Chinese adults, we found pulmonary function and cognition substantially decreased with age. High baseline pulmonary function was associated with a lower rate of cognitive decline independent of confounders. The inverse association between pulmonary function and cognitive decline was stronger in women, never smokers, or low-educated individuals.

We found that PEF, as a measure of pulmonary function, is a strong predictor of change in cognition over time, particularly in tests of memory. This is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that poorer pulmonary function, as a risk factor, is comparable in magnitude to well-known risk factors of dementia including smoking, physical inactivity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and depression (15). The association between poor pulmonary function and cognitive decline may be partly explained by their shared risk factors including older age, low education, smoking, physical inactivity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and psychiatric disorders (18–20). However, these confounders were adjusted for in our analysis, with the relationship remaining significant, suggesting an independent relationship between poor pulmonary function and cognitive decline. A possible physiological explanation for this is that poor pulmonary function lowers the arterial partial pressure of oxygen, resulting in cognitive decline (34,35). Further analysis suggests the variation in performance between 3 trials of the PEF tasks had a strong association with the change in cognition; however, these findings need to be confirmed in future studies.

There are several different measures of pulmonary function, including forced expiratory flow, forced vital capacity, and PEF, that have all been linked to cognition (16). It has been reported that PEF yielded a higher pooled risk (hazard ratio [95% CI]: 2.21 [1.73–2.82] for the lowest quantile vs the highest quantile) for dementia compared with forced expiratory flow (1.46 [0.77–2.75]) and forced vital capacity (1.58 [1.07–2.33]) (15). A recent meta-analysis by Russ et al reported that only 1 out of 10 studies linking pulmonary function to cognitive decline/dementia used PEF as the measure of pulmonary function (15). However, only PEF was measured in our study; we were unable to determine whether PEF had a stronger association with cognition than other measures of pulmonary function. The association between PEF and cognition remained significant when our analysis was restricted to individuals with known lung disease. Our analysis also showed that results were similar among individuals who gave full effort or were standing when measuring PEF. This suggests that PEF, as a measure of pulmonary function, is a reliable predictor of cognition in older adults.

We found the inverse association between pulmonary function and cognitive decline was stronger in women, those who never smoked, or those who had low education levels. Our results are consistent with a cross-sectional study of older Korean adults demonstrating that the association between pulmonary function and dementia was observed in women but not in men (36). This may be attributed to the fact that women are more sensitive to hypoxia or other physiological changes associated with decreased pulmonary function than men, thus resulting in a higher decrease in cognition (35,37). We also found that individuals with higher education had higher performance in cognition assessment, and that memory, orientation, and global cognition domains were sensitive to changes with age, even in individuals with varying levels of education (Supplementary Figure S2). This indicates the reliability of the cognitive assessment tool used in our study, even in those who were illiterate. The association between pulmonary function and cognition in individuals with higher education was weaker; this may be partly due to the fact that they were less likely to demonstrate cognitive decline during follow-up. Smoking is an independent risk factor for both cognitive decline and lung disease (12,20); however, whether the association between pulmonary function and cognition was modified by smoking is less clear. Our study concurs with a previous study in men, demonstrating that the positive association between pulmonary function and cognitive decline was stronger in those who had never smoked (38). Our findings highlight the importance of the maintenance of pulmonary function for the prevention of the cognitive decline in older adults, especially among women, low-educated individuals, and those who had never smoked.

The strengths of the present study included a large sample as well as the objective measurements of pulmonary function and cognition at multiple time points. It also uniquely examined whether the association between pulmonary function and cognitive decline was modified by gender, smoking, and education. However, this study has several limitations. Firstly, individuals included in our analysis were younger, healthier, and more likely to live in rural areas than those excluded from the analysis. This may limit the generalizability of our findings to the whole population of China, despite the weighting of all these variables in our analysis. Furthermore, there are several measures of pulmonary function. However, only PEF was measured in our study. More longitudinal studies with multiple measures of pulmonary function are needed to examine which of the measures was more predictive of cognitive decline. Thirdly, there may be measurement errors in the cognitive assessment and there are no clear cutoffs for defining a clinical disorder in our study. The reliability of the global cognitive score to interpret the clinical significance of a change in performance is unclear. Fourthly, the present analysis was conducted in a subgroup of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study cohort so that the results may not be generalized to the general population. Fifthly, we did not control for air pollution and this may influence the relationships observed. Future research needs to explore the interaction of air pollution and pulmonary function for cognitive function. Finally, because of the observational nature of the analysis in the present study, causal relations could not be inferred.

Conclusions

High baseline pulmonary function was independently associated with a lower rate of cognitive decline in older Chinese adults. The inverse association between pulmonary function and cognitive decline was stronger in women, lower-educated individuals, or never smokers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Behavioral and Social Research Division of the National Institute on Aging, the Natural Science Foundation of China, the World Bank, and Peking University for financial support. We thank the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) research and field team as well as every respondent in the study for their contribution.

Funding

This work was supported by the Behavioral and Social Research division of the National Institute on Aging of the National Institute of Health (grants 1-R21-AG031372-01, 1-R01-AG037031-01, and 3-R01AG037031-03S1); the Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 70773002, 70910107022, and 71130002), the World Bank (contracts 7145915 and 7159234), and Peking University. There is no funding for the publication of this work.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Alzheimer A. Über einen eigenartigen schweren Erkrankungsproze β der Hirnrincle. Neurol Central. 1906;23:1129–1136. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nichols E, Szoeke CEI, Vollset SE, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:88–106. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30403-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jia J, Wang F, Wei C, et al. The prevalence of dementia in urban and rural areas of China. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390:2673–2734. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31363-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baumgart M, Snyder HM, Carrillo MC, Fazio S, Kim H, Johns H. Summary of the evidence on modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia: a population-based perspective. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:718–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schwingshackl L, Bogensberger B, Hoffmann G. Diet quality as assessed by the healthy eating index, alternate healthy eating index, dietary approaches to stop hypertension score, and health outcomes: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118:74–100.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2017.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–446. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30367-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Power MC, Adar SD, Yanosky JD, Weuve J. Exposure to air pollution as a potential contributor to cognitive function, cognitive decline, brain imaging, and dementia: a systematic review of epidemiologic research. Neurotoxicology. 2016;56:235–253. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen H, Kwong JC, Copes R, et al. Living near major roads and the incidence of dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis: a population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2017;389:718–726. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(16)32399-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kilian J, Kitazawa M. The emerging risk of exposure to air pollution on cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease—evidence from epidemiological and animal studies. Biomed J. 2018;41:141–162. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Willemse BW, Postma DS, Timens W, ten Hacken NH. The impact of smoking cessation on respiratory symptoms, lung function, airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:464–476. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00012704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cooper CB. Exercise in chronic pulmonary disease: aerobic exercise prescription. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(7 suppl):S671–S679. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200107001-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Menzies D, Nair A, Williamson PA, et al. Respiratory symptoms, pulmonary function, and markers of inflammation among bar workers before and after a legislative ban on smoking in public places. JAMA. 2006;296:1742–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.14.1742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Russ TC, Kivimaki M, Batty GD. Respiratory disease and lower pulmonary function as risk factors for dementia: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Chest. 2020;157(6):1538–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duggan EC, Graham RB, Piccinin AM, et al. Systematic review of pulmonary function and cognition in aging. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75:937–952. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yaffe K, Laffan AM, Harrison SL, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, hypoxia, and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older women. JAMA. 2011;306:613–619. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Batty GD, Gunnell D, Langenberg C, Smith GD, Marmot MG, Shipley MJ. Adult height and lung function as markers of life course exposures: associations with risk factors and cause-specific mortality. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21:795–801. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-9057-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:285–293. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.2.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Batty GD, Shipley MJ, Kvaavik E, et al. Biomarker assessment of tobacco smoking exposure and risk of dementia death: pooling of individual participant data from 14 cohort studies. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018;72:513–515. doi: 10.1136/jech-2017-209922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vaz Fragoso CA, Gill TM. Respiratory impairment and the aging lung: a novel paradigm for assessing pulmonary function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:264–275. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stigger FS, Zago Marcolino MA, Portela KM, Plentz RDM. Effects of exercise on inflammatory, oxidative, and neurotrophic biomarkers on cognitively impaired individuals diagnosed with dementia or mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74:616–624. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lahousse L, Ziere G, Verlinden VJ, et al. Risk of frailty in elderly with COPD: a population-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:689–695. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ouyang Y. China wakes up to the crisis of air pollution. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:12. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(12)70065-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yin P, He G, Fan M, et al. Particulate air pollution and mortality in 38 of China’s largest cities: time series analysis. BMJ. 2017;356:j667. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cao Q, Liang Y, Niu X. China’s air quality and respiratory disease mortality based on the spatial panel model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(9):1081. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14091081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:61–68. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Langa KM, Weir DR. Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: the Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66(suppl 1):i162–i171. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meng Q, Wang H, Strauss J, et al. Validation of neuropsychological tests for the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31:1709–1719. doi: 10.1017/s1041610219000693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Heesch KC, Burton NW, Brown WJ. Concurrent and prospective associations between physical activity, walking and mental health in older women. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:807–813. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.103077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rosow I, Breslau N. A Guttman health scale for the aged. J Gerontol. 1966;21:556–559. doi: 10.1093/geronj/21.4.556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nagi SZ. An epidemiology of disability among adults in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1976;54:439–467. doi: 10.2307/3349677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. doi: 10.2307/2531248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wagner PD. The physiological basis of pulmonary gas exchange: implications for clinical interpretation of arterial blood gases. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:227–243. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00039214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McMorris T, Hale BJ, Barwood M, Costello J, Corbett J. Effect of acute hypoxia on cognition: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;74(Pt A):225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yoon S, Kim JM, Kang HJ, et al. Associations of pulmonary function with dementia and depression in an older Korean population. Psychiatry Investig. 2015;12:443–450. doi: 10.4306/pi.2015.12.4.443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. De Leeuw FE, de Groot JC, Achten E, et al. Prevalence of cerebral white matter lesions in elderly people: a population based magnetic resonance imaging study. The Rotterdam Scan Study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:9–14. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.1.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weuve J, Glymour MM, Hu H, et al. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second and cognitive aging in men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1283–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03487.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.