Abstract

Many animals engage in aggression, but chimpanzees stand out in terms of fatal attacks against adults of their own species. Most lethal aggression occurs between groups, where coalitions of male chimpanzees occasionally kill members of neighboring communities that are strangers. However, the first observed cases of lethal violence in chimpanzees, which occurred at Gombe, Tanzania in the 1970s, involved chimpanzees that once knew each other. They followed the only observed case of a permanent community fission in chimpanzees. A second permanent fission recently transpired at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda. Members of a large western subgroup gradually ceased associating peacefully with the rest of the community and started behaving antagonistically toward them. Affiliation effectively ended by 2017. Here, we describe two subsequent lethal coalitionary attacks by chimpanzees of the new western community on males of the now separate central community, one in 2018 and the second in 2019. The first victim was a young adult male that never had strong social ties with his attackers. The second was a high-ranking male that had often associated with the western subgroup before 2017; he groomed regularly with males there and formed coalitions with several. Other central males present at the start of the second attack fled, and others nearby did not come to the scene. Several western females joined in the second attack; we suggest that female–female competition contributed to the fission. This event highlighted the limits on protection afforded by long-term familiarity and the constraints on costly cooperation among male chimpanzees.

Keywords: Chimpanzees, Conspecific Killing, Male Social Bonds, Permanent Fission

Introduction

Across vertebrate species, individuals fight for access to territories, mating opportunities, and food resources. In many mammal species, aggression against conspecifics can become deadly (Gómez et al. 2016), most notably in the case of infanticide (Hrdy 1979). Lethal aggression can also occur between mature individuals of the same species during male mating competition, as in lions (Panthera leo: Mosser and Packer 2009), white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus: Gros-Louis et al. 2003), and mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei: Rosenbaum et al. 2016). It also can be associated with competition over feeding territories (e.g., female lions: Mosser and Packer, 2009; Packer et al. 1988, 1990; wolves, Canis lupus: Cassidy and McIntyre 2016; Cubaynes et al. 2014; African wild dogs, Lycaon pictus: Creel and Creel 2002).

Aggression can also occur when competition within groups becomes high and groups split in two. Permanent fissions of primate groups have been well documented in baboons and macaques (e.g., Papio cynocephalus: Van Horn et al. 2007) and some other primates (e.g., Cercopithecus mitis: Cords 2012). Such fissions seem to occur when groups are too large and the costs of group living outweigh the benefits (Markham and Gesquiere 2017). Relationships between daughter groups following permanent fissions in monkey species can be hostile, but without involving lethal aggression (e.g., northern muriquis, Brachyteles hypoxanthus: Tokuda et al. 2014; vervets, Chlorocebus aethiops: van de Waal et al. 2017; Formosan macaques, Macaca maura: Hsu et al. 2017). In other species, however, permanent group fissions might lead to lethal aggression between daughter groups. For example, female lions defend feeding territories against those in neighboring prides and sometimes kill neighboring females (Heinsohn 1997; Mosser and Packer 2009; Packer et al. 1988, 1990; Pusey and Packer 1987). New prides form by permanent fission of existing prides; relatedness between daughter prides following fissions is initially high, but declines over time (Pusey and Packer 1987; VanderWaal et al. 2009). New daughter prides are initially more tolerant of each other than of other neighboring prides, but tolerance wanes after several years as relatedness decreases; concomitantly, the risk of serious, potentially lethal wounding in interpride encounters increases (Pusey and Packer 1987; VanderWaal et al. 2009).

Lethal aggression against conspecifics is especially frequent in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), notably in cases of competition between groups (Wilson et al. 2014; Wrangham 1999). Chimpanzees form multimale, multifemale communities characterized by high fission–fusion dynamics in which the entire group is rarely, if ever, together in the same place at the same time (Goodall 1986; Nishida 1979). Nevertheless, community members cooperate to defend their shared territory, and hostility between neighboring communities includes lethal coalitionary attacks by members of one community on those of neighboring communities. Lethal aggression is most likely during territorial boundary patrols, when members of one community search for opportunities to make low-risk attacks on outnumbered members of neighboring communities (Boesch and Boesch-Achermann 2000; Langergraber et al. 2017; Mitani and Watts 2005; Wrangham 1999). Males are the main participants in patrols and lethal attacks, and the frequency of lethal coalitionary intergroup aggression is positively associated with the number of males per community (Wilson et al. 2014). Success in intergroup competition can lead to territorial expansions (Mitani et al. 2010; Williams et al. 2004). Dispersal, via intercommunity transfer, is restricted to females and is almost entirely by nulliparous females (Pusey and Schroepfer-Walker 2013). Extragroup paternity is rare; thus, depending on their success in intergroup aggression, males can gain reproductive benefits by maintaining or increasing access to food for females and young in their communities (Langergraber et al. 2017; Mitani et al. 2010; Williams et al. 2004), by reducing infanticide risk, and by attracting female immigrants.

Besides cooperating in intergroup aggression, males in the same community form strong social bonds with each other that involve frequent association and grooming (Mitani 2009b). Many male dyads also form coalitions that can influence the outcome of intragroup competition for dominance ranks (Mitani 2009a; Nishida and Hosaka 1996; Watts 2018). Participation in coalitions can influence male fitness, both because male reproductive success is positively associated with dominance rank (Langergraber et al. 2013) and because a male’s position in his community’s coalition network can influence his probability of siring offspring independently of his rank (Gilby et al. 2013).

Male grooming and coalition networks give cohesion to chimpanzee communities, but these ties can fray. Researchers have seen or inferred 10 cases of intracommunity coalitionary killings of adult male chimpanzees and several of adult females (Fawcett and Muhumuza 2000; Kaburu et al. 2013; Nishida 1996; Pruetz et al. 2017; Watts 2004; Wilson et al., 2014). Additionally, killings of at least four, and probably five adult males and one adult female occurred over a 4-yr period at Gombe, Tanzania during the 1970s in association with the permanent fission of the community (Feldblum et al. 2018; Goodall 1986; Goodall et al. 1979). The victims were all from the southern of the daughter communities (Kahama), and the attackers were all from the northern community (Kasekela; Goodall 1986). These attacks have entered the literature as intercommunity killings (Goodall 1986; Goodall et al. 1979; Wilson et al. 2014). However, both observations (Goodall 1979; Goodall et al. 1979) and post hoc analysis (Feldblum et al. 2018) showed that the attacking males killed other males with which they had previously associated peacefully and that had been among their grooming partners. In this regard, the killings differed from most documented lethal attacks in chimpanzees, which have occurred between communities in which the attackers and their victims were presumably strangers (Wilson et al. 2014).

The lethal attacks at Gombe in the 1970s also stand out as it is the only prior observed case of a permanent community fission in chimpanzees. Genetic evidence indicates that permanent fissions of chimpanzee communities are extremely rare. The estimated ages of eight communities in western Uganda varied from 125 yr to 2625 yr (Langergraber et al. 2014). The Gombe case suggests that permanent group fissions in chimpanzees may be associated with intense lethal aggression comparable to that typically displayed between groups. Indeed, the fission was not successful, as all members of one of the daughter groups were killed, and the other daughter group regained the territory that had been temporarily lost during the fission (Goodall 1986).

Here we report two lethal attacks associated with a permanent community fission at Ngogo, in Kibale National Park, Uganda, where chimpanzees have been observed continuously since 1995 (Watts 2012; Wood et al. 2017). Our objectives here are 1) to document two coalitionary killings of Central males by West chimpanzees and to present circumstantial evidence of a possible third killing, and 2) to provide contextual information on the previous social relationships between the victims and their attackers and, in one case, illustrate the dissolution of social bonds.

Methods

Study Site and Population

The Ngogo chimpanzee community has been under continuous observation since June 1995. Its composition at the start of the study was uncertain, but it had ca. 145 members at that date. The size of the community subsequently increased and reached around 200, including more than 30 adult males, by 2015 (Langergraber et al. 2017; Wood et al. 2017). Three main sociospatial subgroups were evident early in the history of the study (cf. Mitani and Amsler 2003) and persisted thereafter. Males joined one or another subgroup as they matured; females immigrants also joined one or another of the subgroups; and natal females that did not emigrate either remained in their mothers’ subgroups or switched subgroups as they matured. The Central community had 25 adult males (≥16 yr) and 11 late adolescent males (12–15 yr) at the time of the first attack in 2018, and had 26 adults and eight late adolescents at the time of the second attack in 2019. The West community had seven adult males and two late adolescent males in 2018 and seven adults and four late adolescents in 2019. We also refer in the text that follows to adult females (≥13 yr), adolescent females (9–12 yr), juveniles (6–8 yr), and infants (≥5 yr).

Association and ranging data clearly showed that all study subjects initially belonged to one unusually large community, although adults of both sexes showed variation in association and space use patterns that allowed researchers to identify western, central, and eastern sociospatial subgroups (Langergraber et al. 2007, 2013; Mitani and Amsler 2003; Wakefield 2008, 2013). Despite this subgrouping, all males associated with each other (albeit at varying rates) and jointly defended a shared territory (Langergraber et al. 2017; Mitani and Watts 2005; Mitani et al. 2010; Watts et al. 2006). In 2015, association and affiliation between members of the western subgroup and all other community members started to decline sharply. When members of the western subgroup were close to or encountered central and/or eastern subgroup members, the chimpanzees started to behave as they do during intercommunity interactions. This behavior included outbreaks of male charging and buttress drumming displays, accompanied by calls typical of interactions with neighbors, without direct encounters; similar outbreaks accompanied by charges and chases back and forth during direct encounters; silent avoidance of members of the other subgroup(s) after hearing them call; silent stalking of members of the other subgroup(s) after hearing them call or after direct encounters had broken off; and, eventually, patrol-like behavior, but well within what had been the boundaries of the Ngogo community territory. By the end of 2017, peaceful interactions between western subgroup members and others had ceased. For these reasons, we consider that they now form a separate community (cf. van de Waal et al. 2017 for vervet monkeys; Mitani 2020) and refer to them below as the “West” community. No such changes in agonistic behavior among members of the central and eastern subgroup occurred. In fact, eastern and central males participated jointly in hostile interactions with members of the western subgroup. Thus, we consider that the eastern and central subgroups still form a single community; for convenience, we refer to this as the “Central” community. In collaboration with other Ngogo researchers, we will provide a detailed analysis of the social and demographic antecedents and potential causes of this fission elsewhere.

Names of key individuals involved in the attacks (Table I) follow conventions used by all Ngogo Chimpanzee Project researchers.

Table I.

Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) present at two lethal attacks on chimpanzees of the Central community following the permanent fission at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda

| Community | Name | Sex | Age | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | Erroll | M | 16 | Observed killed 1/24/2018 (Event 1) |

| Central | Basie | M | 33 | Observed killed 6/15/2019 (Event 2) |

| Central | Brownface | M | 53 | Present Events 1 and 2 |

| Central | Jackson | M | 27 | Present Event 2 |

| Central | Mulligan | M | 30 | Present Event 2 |

| Central | Wilson | M | 19 | Present Event 2 |

| Central | Chopin | M | 17 | Present Event 2 |

| Central | Puccini | M | 11 | Present Event 2 |

| Central | Aretha | F | 44 | Present Event 2 |

| Central | Christine | F | 19 | Present Event 2; had infant and juvenile |

| Central | Dolly | F | 13 | Present Event 2 |

| Central | Frida | F | 10 | Present Event 2 |

| West | Garrison | M | 41 | Attacker Event 2 |

| West | Rollins | M | 32 | Attacker Events 1 and 2 |

| West | Richmond | M | 32 | Attacker Events 1 and 2 |

| West | Hutcherson | M | 24 | Attacker Events 1 and 2 |

| West | Wayne | M | 22 | Attacker Events 1 and 2 |

| West | Wes | M | 21 | Attacker Events 1 and 2 |

| West | Buckner | M | 18 | Attacker Event 2 |

| West | Murray | M | 15 | Attacker Event 2 |

| West | Damien | M | 13 | Attacker Events 1 and 2 |

| West | Billy Bragg | M | 14 | Attacker Event 2 |

| West | Senta | F | 33 | Attacker Event 2; had infant and juvenile |

| West | Carson | F | 25 | Attacker Event 2; had infant |

| West | Sabin | F | 22 | Present Event 2; had infant and juvenile |

Event 1 = attack on Erroll (January 2018); Event 2 = attack on Basie (June 2019). Ages are in years (rounded to the nearest year) and are age at death for Erroll and Basie, age in 2018 for participants in Event 1, and age in 2019 for individuals that participated only in Event 2. Brownface originally belonged to the western male subgroup at Ngogo, but by 2018 had joined the Central community following the community fission.

Data Collection

DW conducted 22 annual field seasons from 1998 through 2019. During each field season, he used focal sampling of adult males and focal behavior sampling of grooming bouts involving all visible males to collect data on grooming between adult males and between adult and adolescent males. He used focal and ad libitum sampling to collect data on coalitions between males. He also conducted scans every 30 minutes to collect data on male–male party association. These data provided background information on the social relationships between the attackers and their victims (see Supplementary Methods and Data). AS conducted three field seasons: from August 2014 to August 2015, from October 2017 to June 2018, and from June 2019 to November 2019. He used focal sampling on adolescent and young adult male chimpanzees to collect continuous data on grooming, aggression, and other social interactions, and instantaneous scan sampling of 5-meter proximity at 10-minute intervals. He also recorded all occurrences of grooming, aggression, and tolerated physical contact between males and females of any ages outside of focal sampling sessions. Both of us collected behavioral data opportunistically when Ngogo chimpanzees interacted with members of neighboring communities, either directly or without visual encounters. We also used ad libitum sampling to collect data during the two attacks, during the encounter that preceded the second attack, and while monitoring the victim of that attack on the following morning. We obtained video recordings that helped us to identify specific acts that occurred during the second attack, although the actors were not always identifiable.

Following the two lethal attacks, we inspected the bodies of the chimpanzee victims to assess injuries and take basic morphological measurements, including body mass, which we measured using a hanging scale. Following the first lethal attack, a veterinarian from the Uganda Wildlife Authority assessed injuries from a visual inspection and by palpating the corpse. No veterinarian was present for the second attack, but researchers followed similar procedures, visually inspecting injuries, including using a tape measure to measure the size of wounds, and palpating the body to determine whether any bones were broken. We buried each corpse in a blanket or burlap bag 5–8 h after the chimpanzee had died to allow for the collection and storage of the skeleton. Veterinarian and researchers used full Personal Protective Equipment, including Tyvek coveralls, booties, double gloves, N-95 facemask, and goggles.

Ethical Note

All data were purely observational, and we collected them with the authorization of the Uganda Wildlife Authority, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and Makerere University. Field methods conformed with the ethical guidelines of the International Primatological Society and the American Society of Primatologists and the “Guidelines for the treatment of animals in behavioral research and teaching” of the Animal Behavior Society and were considered exempt from Animal Care and Use approval. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Attack 1: Killing of Young Adult Male Chimpanzee Erroll at Ngogo

The first attack occurred on January 24, 2018. The victim was Erroll, a 15.5-yr-old young adult Central male (Table I). On January 23, 2018, AS had observed Erroll in a party of Central chimpanzees in the middle of the Ngogo territory near a Ficus mucuso (“mucuso,” below) tree where they had been feeding. The party comprised eight adult males, one adolescent male, one juvenile male, two juvenile females, and five adult females. The adult males included Brownface, whose presence and behavior was particularly noteworthy because researchers initially identified him as a member of the western male subgroup, and he continued associating regularly with other West chimpanzees in 2017. By October 2017, however, he associated exclusively with Central chimpanzees. He was the last male to associate peacefully and interact affiliatively with members of both communities.

AS left these Central chimpanzees to search for West chimpanzees. He found all seven adult male West chimpanzees and many adult females and immature individuals <1 km to the west. At 17:30, all the West chimpanzees except one adult male and one juvenile male travelled east. At 17:50, they fell silent and moved cautiously, as if on a territorial boundary patrol. At 18:13, the West chimpanzees, with the males in the front, rushed silently toward the mucuso where the Central chimpanzees had been earlier that day. A chimpanzee gave a “wraaa” call from ahead, out of sight of the observer; this might have been a Central chimpanzee, but the observer could not rule out the possibility that it was a West chimpanzee because not all were visible. The West chimpanzees scattered within 50 m of the mucuso and started to call and give charging displays. They continued doing this for 20 min. Whether any Central chimpanzees were near enough to hear the calls was uncertain, but if they were, they did not respond audibly.

At 07:45 the next morning (January 24), most of the West male and female chimpanzees that had been present the night before were in another fig tree (a Ficus natalensis) near the mucuso. The author was still trying to identify all the individuals in the tree at 08:05 when they suddenly stopped feeding and about half of them, including several males and females, rushed partway down the tree. Their attention was focused on something below them. At this point, AS realized that Erroll was on the ground below the tree, near the edge of stream (Fig. 1a), and that he had been severely attacked. His left ear was completely missing and he had deep cuts on his face, especially on his nose, his left brow, and around his left eye. He also had wounds on his left arm, cuts on his right arm and the left side of his back, and a large, deep wound on his upper thigh. His hair was soaking wet, either from the stream or from blood. Patches of hair were missing from his left arm and the left side of his back. The wounds looked like they were fatal.

Fig. 1.

Lethal attack on adult male chimpanzee, Erroll, in 2018 at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda. Erroll was a low-ranking, young adult male from the Central community, and was attacked by chimpanzees from the West community. (a) Condition when AS first saw him beneath a tree where the other chimpanzees were feeding. (b) Subsequent attack by three West adult males. (c) A fourth West male also joined the attack. (d) Erroll lay prone after five adult West males attacked him. He died within the next 2 h.

Erroll had been lying silently on the ground; he now sat up and emitted “wraaa” alarm calls (Goodall 1986). After 2 min, he slumped forward, his head and chest on the forest floor. He managed to sit again and emitted more calls, but again slumped forward. At 08:16, he shifted position slightly. At 08:35, several West adult males climbed down into a tree adjacent to the fig and watched him. At 08:39 they climbed to the ground. At 08:45, Wes, Wayne, and Richmond rushed toward Erroll, who tried to stand. Wayne leapt forward, bending a sapling toward Erroll. Within seconds, the three of them attacked Erroll: they held him as they bit his arms and back and tossed him back and forth (Fig. 1b). Muscle hung loose from Erroll’s thighs as they flipped him onto his back. Richmond and Wes bit him continuously, while Wayne moved around and bit him opportunistically. Wes stomped on Erroll, then stood on him and bit him. All three had small pieces of Erroll’s flesh in their mouths.

The attackers paused after 35 s. Richmond moved 1 m behind Erroll, Wes released his grip, and Wayne retreated 2 m. This allowed Erroll to sit up. He called as he did so and oriented toward Wes, who was 1 m in front of him, screaming. After only 5 s, a fourth male (Rollins) leapt toward Erroll, landing on him with both feet and then slapping him (Fig. 1c). The four males then sat around Erroll, who was still sitting up, with Wes only centimeters from him and Richmond 1 m away. Richmond moved off, but at 08:47, after a 70-s pause, a fifth male (Hutcherson) jumped on Erroll, grabbed him by the back and legs, and briefly dragged him. Erroll remained prone when he let go. Wes and Richmond touched and sniffed Erroll, and adolescent male Murray approached and also sniffed him, then moved off. A few seconds later Erroll lifted his head and vocalized. Twenty seconds later, Wes also moved off. Rollins was still within 5 m of Erroll. Meanwhile, some other chimpanzees had climbed halfway down a nearby tree, and a natal adolescent female that had transferred from Central to West and that presumably recognized Erroll descended and stood within 3 m of him. By 08:50, Erroll lay prostrate; his eyes were closed, but he moved slightly and repositioned himself (Fig. 1d).

At 08:59, the adult and adolescent West males plus one juvenile male began moving eastward. Brownface started to follow, but then turned and moved west; observers did not see him again that day. The other males silently and vigilantly traveled 500 m E, then gave an outburst of pant-hoots and screams before moving back W.

By 10:00, Erroll was at most barely breathing and was probably dead. Wes and several others returned to his body, and research assistant Isabelle Clark saw them drag Erroll’s body 2–3 m. Around midday, Richmond and Rollins returned to Erroll’s body; Rollins displayed, dragged his body <1 m, and then dragged a branch over it.

The next day, AS saw that adult West male Buckner had two deep puncture wounds on his arm. He had not seen Buckner during the attack, but Buckner could have participated in the initial attack, been wounded by Erroll, and then left. No other West males had observable wounds.

Visual inspection of Erroll’s injuries showed that 1) almost all the wounds were on the front; 2) they included punctures to the lower abdomen, arms, left brow, and inguinal region; 3) many were deep and several bones were visible (e.g., the medial left and right femur); 4) one testicle was gone and the other was bruised; and 5) Erroll had experienced massive external bleeding. He presumably also suffered internal injuries from the blows and stomping.

Attack 2: Killing of Adult Male Chimpanzee Basie at Ngogo

A second lethal attack occurred on June 15, 2019, in what had been the middle of the Ngogo territory (Mitani et al. 2010), but had become a contested overlap area since the community fission. The victim was Basie, a 33-yr-old Central male (Table I). Early that morning, 27 Central chimpanzees, including nine adult and two adolescent males, six adult females and one adolescent female, five juveniles, and four infants gathered in a mucuso. Basie was among them. Most traveled several hundred meters NW at 08:15 to feed in an Aningeria altissima (“aningeria,” below) tree that had an enormous fruit crop. Central chimpanzees had visited this tree repeatedly in the previous several weeks; West chimpanzees had also used it. The Central males descended at 09:30 and rested nearby. At 09:35, 09:43, and 09:45 they alerted and looked NW as if they heard chimpanzees—Ngogo West chimpanzees had been within 1–2 km to the northwest in the preceding 2 days—but quickly resumed resting (DW did not hear calls, but had often seen similar alerts followed by evidence that other chimpanzees were within potential auditory range in that direction).

At 09:47 the chimpanzees at the aningeria heard calls to the SE as other Central chimpanzees arrived at the mucuso. They jumped up, gave a big chorus, and rushed toward the callers. Most, including Basie, went to the mucuso. Alpha male Jackson, Brownface, and several others briefly stopped to rest before reaching the mucuso when they met adult female Aretha, who had a full sexual swelling, then moved SW. The males at the mucuso fed until 11:40, then also moved SW. However, they stopped for a long rest and grooming session without reaching Jackson and Brownface. Brownface joined them at 14:00. Basie charged at him, which initiated several minutes of excited movement. Most of the Central chimpanzees then traveled N and returned to the aningeria. They gave many pant-hoots as they approached the tree. Basie was not with them; he stopped to rest again, and young adult male Wilson groomed him. Shortly thereafter, Jackson appeared and charged at Basie and Wilson; they avoided his charge, but Basie then approached Jackson, who groomed him. After a long grooming session, Basie moved north and joined other Central males on the ground near the aningeria at 15:14. Jackson joined them at 15:18.

At that point, 11 adult and 4 adolescent males plus several females were in or near the aningeria. DW and AS were with them. Several of these chimpanzees returned to the mucuso while the others rested briefly. Researcher Kevin Lee arrived and told DW that he had been following some of the West chimpanzees, but lost contact with them as they moved quickly and silently through dense vegetation toward the aningeria. He thought they might have made the screams at 15:18 and confirmed that West chimpanzees had heard multiple outbreaks of calls from the Central chimpanzees earlier in the day. He then left to resume his search. At 15:29 Jackson traveled about 300 m NNE to a second aningeria on the side of a small valley and fed there. Basie joined him there, as did adult males Mulligan, Brownface, Wilson, and Chopin, adolescent male Puccini, adult female Christine with her infant and juvenile, adult female Aretha and her adolescent daughter Frida, and adolescent female Dolly (Table I). DW followed them to this tree.

Most of these chimpanzees were still feeding at 16:25 (Aretha, Frida, and Dolly were sitting in a smaller adjacent tree) when West chimpanzees rushed in below them. They were nearly silent, but the rustling vegetation and flurry of motion alerted the Central chimpanzees, who stopped feeding and looked down silently and apprehensively. The intruders included all West adult males, adolescent males Billy Bragg and Damien, and adult females Carson with her infant, Sabin with her infant and juvenile, and Senta with her infant and juvenile (Table I). Many other West chimpanzees were nearby but did not join the confrontation.

For about 5 min, the chimpanzees in the canopy and those on the ground sat quietly and tensely watched each other. At 16:30 the Central chimpanzees uttered an outbreak of screams and wraaas. This prompted calls in response from other Central chimpanzees to the S—none of whom came to the site of the confrontation—and prolonged charging displays by West males. Several more outbreaks of charging and screaming occurred over the next 20 min, with the last a prolonged outburst at 16:54 (by which time AS had joined DW at the site). Each outbreak prompted more calls from other Central chimpanzees to the S, but still none came. The situation settled into a tense stalemate by about 17:05. The West chimpanzees sat or lay on the ground and watched those in the canopy, and male dyads groomed each other. The chimpanzees in the canopy sat motionless and vigilantly monitored those on the ground. Neither group seemed inclined to attack the other.

At 17:22 the West males gave another prolonged charging outbreak; the chimpanzees in the canopy again responded with screams and wraas. At 17:26, the West males moved toward the base of the aningeria, and adult male Rollins started to climb a midcanopy level tree that the Central chimpanzees had used to gain entry to the aningeria; he was soon followed by Buckner, Garrison, Richmond, Rollins, and Wes. They initially headed toward Aretha, Frida, and Dolly, but in a series of movement punctuated by brief stops, passed these females to reach a spot where they could use terminal branches of the smaller tree to transfer to the canopy of the aningeria. After another brief pause, they rushed into the larger tree toward the Central male chimpanzees.

The ensuing furious, chaotic action and the constraints on visibility made it impossible for us to keep track of everything that then happened. Most Central chimpanzees somehow escaped from the aningeria’s canopy by going E or SE toward the bottom of the valley and continued to flee from there. West female Carson, with her infant clinging ventrally, chased Central female Christine, who also had a ventral infant; they hit each other, but Christine escaped. Dolly fled without being directly attacked. Meanwhile, West males Garrison, Richmond, and Rollins isolated Central male Mulligan on the edge of the aningeria, high in the canopy, for about 30 s. The West males alternately chased and lunged at Mulligan, who avoided them, and backed off as he sometimes counter-lunged. At one point, Garrison hit and perhaps bit Mulligan on the back as Mulligan leapt away from him. Mulligan then managed to leap into an adjoining large tree and fled N through its canopy. A few West chimpanzees who were on the ground followed underneath him, and one of his attackers apparently started to pursue him. However, these chimpanzees turned after only a few seconds and ran toward the source of an enormous screaming outburst at the bottom of the valley.

At 17:36, five West chimpanzees had trapped Basie in a small tree (Fig. 2a). Richmond, Hutcherson, and Buckner were attacking him as he frantically scrambled down its trunk while trying to fend them off. He jumped/fell ca. 15 m to the ground and was quickly surrounded by all the adult West males and females Carson and Senta, both carrying their infants ventrally. The other West chimpanzees were at the edge of the pile. Hutcherson and Richmond grabbed Basie and held him from his left side, while Garrison held him from the right. Carson bit and hit him from the front. Wes and Rollins quickly joined the attack, followed by Wayne and Buckner. Sabin, her infant clinging ventrally, hit and tried to bite Basie. Basie managed to bite Richmond on his brow, and Richmond moved out of the pile. Senta initially stayed at the edge, but eventually also made physical contact with Basie.

Fig. 2.

Lethal attack on adult male chimpanzee, Basie, in 2019 at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda. Basie was a high-ranking, middle-aged male from the Central community, and was attacked by chimpanzees from the West community. (a) Three adult West male chimpanzees hitting and biting Basie, who screamed before leaping to the ground, at which point (b) West males and females surrounded and attacked him.

Thirty seconds after the attack on the ground started, Central female Aretha reappeared and rushed into the middle of the fray, next to Basie, where she hit at the West chimpanzees for seven seconds. Carson, with Garrison and Murray following, then chased her away.

Buckner, Garrison, Hutcherson, Richmond, Rollins, and Wes were particularly prominent in this initial attack, which was followed by a pause of about 25 s. Basie, who had received many bites and was bleeding profusely, sat passively and continuously screamed during the lull (Fig. 2b). Buckner, Hutcherson, and Rollins then resumed the attack; others joined them intermittently. Basie tried to fend off the attackers and bit several, but none were seriously injured. The attackers again briefly relented at 17:39; Wes stood next to Basie, who sat and screamed. At 17:40, Basie started to walk away, but Wes followed and resumed attacking him. Garrison, Senta, and Carson joined the attack. They let up after about 20 s, and Basie again sat, screaming, while Garrison and Wes sat next to him. Carson hit him. At 17:42, by which time some of the West chimpanzees had left Basie, he slowly walked east, screaming weakly; Garrison and Wes followed, and Buckner, Richmond, and adolescent Billy Bragg stayed nearby. Other Central chimpanzees to the S continued to call, but none came to the site.

Basie sat after moving only a few meters, and Buckner, Wes, and several other West males soon resumed their attack. Rather than piling on, though, they made individual passes during which they hit or stomped on Basie. After this, Buckner, Garrison, Wes, and Billy Bragg, the last West chimpanzees to stay with Basie, left him and started moving W, although Garrison and Wes went only about 15 m before stopping to rest. Their departure allowed Basie to move slowly up the east side of the valley. Garrison and Wes soon traveled to the first aningeria; many West chimpanzees were feeding there, including some that had not been at the attack site and presumably had started to feed while the confrontation was underway. Others were scattered nearby. DW watched these chimpanzees feed until 18:30.

Meanwhile, Basie moved 30 m uphill from the valley bottom. Brownface reappeared; he screamed, reached out his hand, and touched Basie. He then turned and began to walk NE; Basie followed, and AS followed them. Basie stopped intermittently, sometimes lying on his back, with his foot on a sapling, and sometimes sitting; each time, Brownface also stopped and waited. Brownface called repeatedly, and after he and Basie had been traveling and resting for 9 min, other Central chimpanzees that were now to the E responded. Basie then rested, lying supine, for 11 min. Brownface repeatedly approached him and sat within 1 m, then moved as far as 10 m away. Basie eventually followed Brownface for 34 min, until they reached a small stream in a valley 320 m from the attack site. At 18:33, Basie drank from the stream, found a dry spot next to it, and made a rudimentary nest on the ground at 18:37. At 18:50, at least two other Central chimpanzees approached within 30 m and emitted wraas; they repeated this three times over the next 10 min. By 19:00, the forest was dark. Several chimpanzees nearby pant-hooted and screamed at that point, and Brownface made a nest in a small tree across the stream from Basie.

The next morning at 06:12, AS and research assistant Sharifah Namaganda arrived where Basie had nested. When it became light enough to see, they realized that he had moved 30 m NE, where he sat, slumped, his hair wet and matted with blood and dead leaves. Brownface was with him. No other chimpanzees were in the area, although some Central chimpanzees called to the NE and other chimpanzees, presumably from the West community, called from the SW. Brownface moved a few m away, returned, scratched exaggeratedly, then slowly swayed saplings in Basie’s direction, behavior that males use to try to get females to follow them on consortships (Goodall 1986). Basie did not move. Brownface approached to within 1 m, walked 3 m away, swayed branches, returned and put his hands over Basie’s arm as if to groom him, stopped and sniffed a bloody leaf, then swatted at flies hovering over Basie. Brownface again moved off, then returned. He grimaced and reached a hand out to Basie, who did not move. Brownface continued to pace. Finally, Basie moved 1 m, made another rudimentary nest, and lay down. Brownface left at 09:00. Basie did not move again, and he died at 13:35.

Physical examination revealed that Basie suffered many puncture wounds, including one on his left abdomen, another on his thoracic region below his left clavicle, a deep 9 cm long by 5 cm wide puncture on his left axillary region, a 4 cm × 4 cm puncture wound on his left femur, and a deep puncture on the left side of his upper back. Other wounds included a torn left ear, a cut under his chin, a 6 cm slash going from his left ear to his left brow, two slashes on his upper right arm, and a 4 cm long slash on his upper left arm. Both testicles were present, but his penis was removed, and there was a slash on his anus (4 cm long). Like Erroll, he probably also suffered internal injuries due to pounding and stomping.

Possible Third Killing of Adolescent Male Chimpanzee Orff at Ngogo

Orff, a 13-yr-old adolescent Central male, disappeared in November 2017. The circumstances made researchers wonder whether he had been killed, and the later lethal attacks on Erroll and Basie heightened these suspicions. AS had regularly seen Orff in October 2017, and on November 5 Orff was feeding in a Ficus natalensis with a party that included his mother Sutherland, Erroll, Brownface, and several other Central chimpanzees. Three of the adult females present had been seen associating peacefully with West chimpanzees not long before then despite growing West-Central hostility. The next morning, Central chimpanzees were feeding 1 km E of the F. natalensis. Brownface and some of the females that were with Orff on the previous day were among them, but Orff and other females were not. Those females were seen soon thereafter, but Orff was never seen again. Mortality is low for adolescent males at Ngogo (Wood et al. 2017) and Orff had seemed to be in good health; thus, we suspect that West chimpanzees killed him. Perhaps he and the females returned to the F. natalensis and encountered West chimpanzees. The tree was about 100 m ENE of the site where Erroll was killed 2.5 mo later, and later in November, West chimpanzees traveled to that area and had vocal exchanges with Central chimpanzees that resembled auditory intergroup interactions.

Social Context of the Attacks

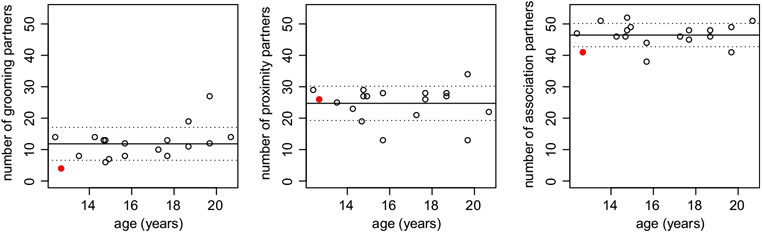

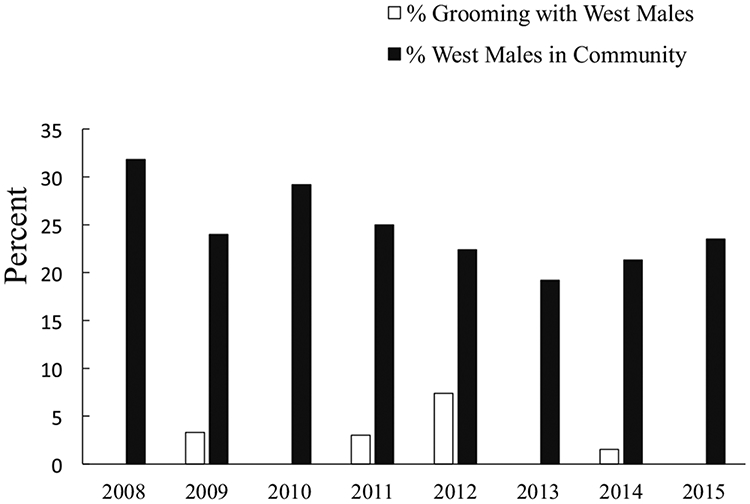

Erroll never had strong social ties to West chimpanzees and was only weakly integrated into Central male social networks. He was among the smallest and lowest ranking of the adult males and was smaller than most adult females (his body mass at death was 25 kg). Between 2008 and 2014, he groomed with fewer than half the adult and adolescent males at Ngogo annually, and most of his grooming was with Central males (Fig. 3). Among West males, he groomed with Brownface, Garrison, Richmond, Buckner, and Brubeck (who died in 2009), but they accounted for very little of his grooming (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] Table SI). His top grooming partner throughout that time was the older of his two maternal brothers (ESM Table SI). From 2014 to 2015, compared to other adolescent and young adult males, Erroll had some of the fewest social partners based on grooming and association (Fig. 4), and he was particularly unlikely to be with West males. His proximity partners included only half (26/53) of the adolescent and adult males in the community, all but one of which were Central males. He was never observed to associate in parties with 9 of 12 West adolescent and adult chimpanzees (including 4 of the 6 that later killed him). In the 3 mo preceding his death, like other Central males, he was never seen associating with, in proximity to, or grooming with West chimpanzees.

Fig. 3.

Grooming between young adult male chimpanzee Erroll and adult and adolescent males in the western subgroup at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda. % Grooming with West Males = % of all grooming given or received by Erroll that was with western males; % West Males in Community = % of all males at Ngogo that belonged to the western subgroup during a given year.

Fig. 4.

Number of social partners among middle- to late-adolescent and young adult male chimpanzees at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda, 3 yr prior to the attack on Erroll. The total number of individuals each male (a) groomed, (b) spent time within 5 m of, and (c) spent time associating in the same party across a 1-yr period between 2014 and 2015. Each point represents an individual male. Erroll is represented by a red point. The solid horizontal line is the mean value, and the dotted lines represent 1 standard deviation above and below the mean.

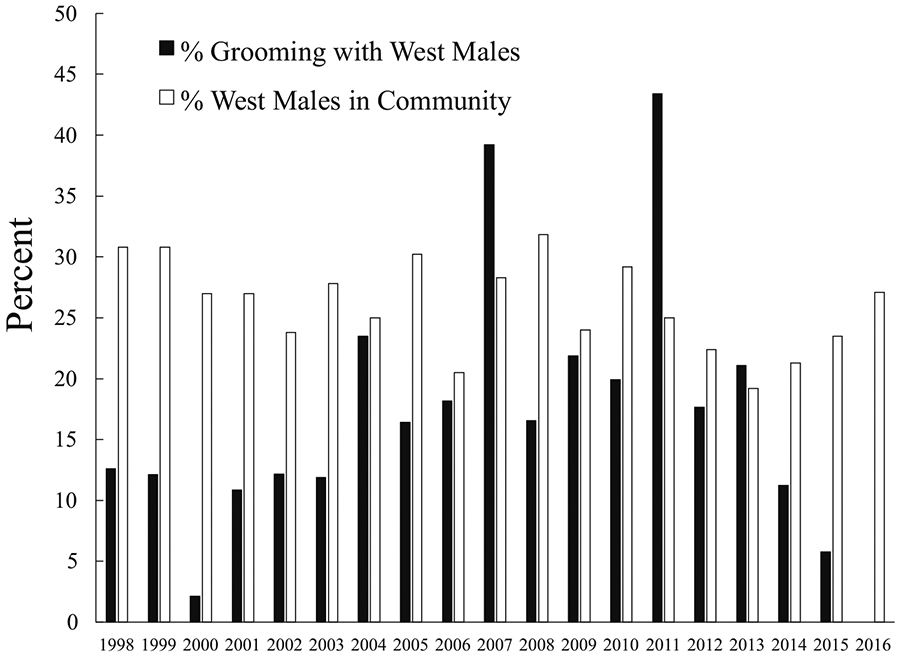

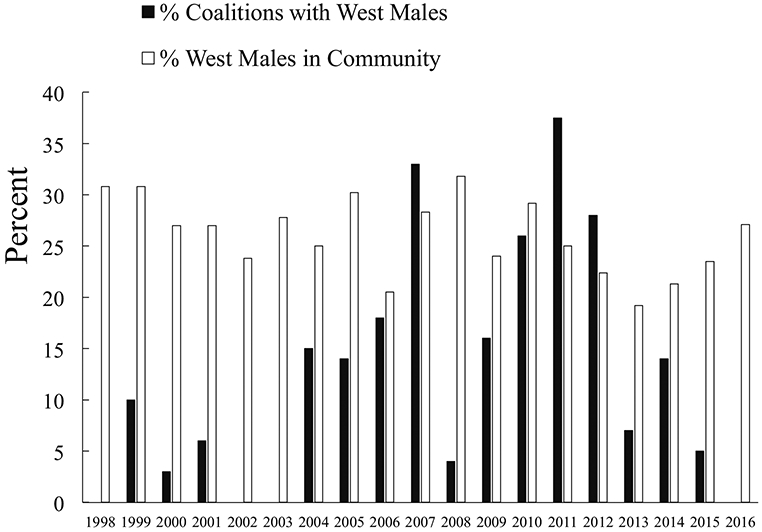

Basie was high ranking: he reached the top quartile of the male dominance hierarchy in 2003 and stayed there until his death. He had close social ties to several other high- or mid-ranking Central males, including current alpha Jackson and several previous alpha males. However, he also spent much time with West chimpanzees prior to 2016. On an annual basis between 1998 and 2015, his average dyadic party association values with western males varied from 12.5% (2014) to 24.8% (2002). His top dyadic values were with Brownface and with three males that had died by 2016, but they approached or exceeded 20% in some years for West males Garrison, Richmond, and Rollins. He mostly groomed with Central males during this time but groomed at least occasionally with most West males (Fig. 5). Basie had particularly close ties with Brownface, who was his top grooming partner among chimpanzees in the western subgroup in 11 of 18 annual data sets between 1998 and 2015 (ESM Table SII). Basie also frequently groomed with Brubeck, Brownface’s younger maternal brother; Brubeck was Basie’s top grooming partner among western subgroup males in six annual data sets before his death in 2009 (ESM Table SII). Basie groomed with Garrison, Richmond, and Rollins through 2015, and Garrison was among his top five grooming partners in 2 yr. Basie was well integrated into coalition networks by 2001 and formed coalitions with many males (ESM Table SIII). His coalition partners were most often other Central males, but he participated in coalitions with multiple West males (Fig. 6), including Garrison (his third ranked coalition partner in 2011), Richmond, and Rollins, all of whom were among his attackers in 2019 (ESM Table SIII). However, his last observed coalitions with Rollins and Richmond were in 2011 and 2012, respectively, and he was never seen to form coalitions with Buckner, Damien, Hutcherson, Murray, Wayne, or Wes, all of whom were among his attackers. Basie also regularly joined West chimpanzees on patrols through 2015.

Fig. 5.

Grooming between adult male chimpanzee Basie and adult and adolescent males in the western subgroup at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda. % Grooming with West Males = % of all grooming given or received by Basie that was with western males; % West Males in Community = % of all males at Ngogo that belonged to the western subgroup during a given year.

Fig. 6.

Coalition formation between adult male chimpanzee Basie and adult and adolescent males in the western subgroup at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda. % Coalitions with West Males = % of all coalitions that Basie formed with western males; % West Males in Community = % of all males at Ngogo that belonged to the western subgroup in a given year.

Discussion

We report two lethal coalitionary attacks by chimpanzees against adult male chimpanzees that were members of the same long-standing community at Ngogo. We suspect a third lethal attack happened against an adolescent male chimpanzee. These attacks appear to be the consequences of a permanent fission of the Ngogo community, the start of which became evident to observers in mid-2015. This is only the second observed permanent fission of a chimpanzee community. The three victims, including the two we observed, were all from the new Central community, and the attackers were from the new West community. The West community is smaller than the Central community and has far fewer adult and adolescent males, but West chimpanzees were the aggressors in both cases. The much greater overall number of Central males did not protect them from attack by cohesive parties of West males. The victim of the first attack, Erroll, was greatly outnumbered, but in the second attack, on Basie, several adult Central males other than the victim fled at the start. Neither those who fled nor other Central males that clearly heard calls from the attack site both during the initial encounter and while the attack was underway intervened to protect the victim. The only intervention was by an adult female; it was ineffective. Several adult West females participated in the second attack, although males were the main aggressors. Long-term data showed that the younger of the two victims, Erroll, a low-ranking young adult, had rarely associated or groomed with any of his attackers prior to the fission. However, the older victim, Basie, a high-ranking prime adult, had often associated with members of the western subgroup, frequently groomed with western males, and repeatedly formed coalitions with some of them prior to the fission. His grooming and coalition partners included several males who attacked him. These long-standing social ties did not protect him from attack. An old adult male who had long belonged to the western subgroup, but remained in the Central community after the split, Brownface, was present at both attacks. He apparently was only a bystander at the first, in which he was not hurt. He fled the site of the second but returned after the attackers had left and stayed with the victim through that night and part of the next morning.

Both lethal attacks resembled those associated with territorial behavior and escalated aggression between communities (Goodall 1986; Manson et al. 1991; Wilson et al. 2014; Wrangham 1999). The West chimpanzees sought the encounter that led to Basie’s death by silently stalking Central chimpanzees they had heard calling. We do not know how the lethal encounter with Erroll started, but West males had briefly patrolled the previous evening and they did so again after attacking him. Researchers have seen both West and Central chimpanzees stalk members of the opposing new community after hearing them; patrol areas that were formerly in the middle of the Ngogo territory, but are now near a boundary between two different territories; and initiate aggressive encounters on other occasions before and since the lethal attacks. However, it might simply have been due to chance that West chimpanzees initiated the only known lethal attacks.

The West chimpanzees clearly had an overwhelming numerical advantage in the attack on Erroll, but lethal escalation was unexpected in the attack on Basie because the initial disparity in the numbers of adult males present was small (Wilson and Wrangham 2003; Wilson et al. 2014; Wrangham 1999). Central males were dispersed in the canopy of the aningeria tree when the West chimpanzees arrived and remained stationary until the West males entered the tree. This could have considerably increased the West males’ actual advantage: if the Central males had congregated near the limited points of ingress to the canopy, they might have fended off the attackers, or the West males might not have tried to enter the tree. Instead, they fled from their isolated positions. They had not been well positioned in the aningeria to make a coalitionary counterattack, but they also did not regroup once they left the tree and make such an attack. Meanwhile, no Central males who had earlier gone south came to the attack site. The absence of defense highlights limits on costly cooperation among male chimpanzees. Once they fled, Basie was greatly outnumbered.

A precedent apparently exists for a lethal attack on an adult male in which the initial imbalance of power was slight, but males from the victim’s community failed to intervene on his behalf. When three Kasekela males attacked Kahama male Dé at Gombe, two other Kahama males were close enough that observers saw them displaying (Goodall et al. 1979). The description of the attack does not specify how close they were or whether they tried to intervene, although the implication is that they did not. However, the Kasekela males were clearly aware of their proximity, because two of them interrupted their attack to chase the Kahama males. Three other Kahama males killed by Kasekela males, one of which one was the last surviving Kahama male, were alone when they were attacked (Goodall 1986; Goodall et al. 1979).

The absence of defense during the attack on Basie highlights the limits in costly cooperation among male chimpanzees. Observers at Ngogo have seen several lethal attacks by Ngogo males on adult males from neighboring communities (Watts et al. 2006; Wilson et al. 2014). Males from those communities did not intervene in those attacks. However, in two cases there was no sign that any males were in the area, and in another Ngogo males broke off their attack while their victim was still alive and quickly returned to their own territory after hearing other neighboring males who were ca. 200–300 m away (Watts et al. 2006). They responded similarly to calls from nearby neighboring males during an infanticidal attack (Watts et al. 2006); those males seemed to be approaching. The failure of the Central males to come to Basie’s defense might have resulted from fear combined with lack of awareness of each other’s locations.

An adult female briefly and ineffectively tried to defend Basie. Although females from neighboring communities were present at the starts of three observed lethal attacks on adult males by Ngogo males, none tried to defend the victims (Watts et al. 2006). Nine or more adult Ngogo males participated in each of other those attacks and several adolescent males were present at each (Watts et al. 2006); intervening would have been highly dangerous. Also, those communities were unhabituated, and the presence of humans might have influenced their behavior. An adult Ngogo female was present at one of those attacks but did not make physical contact with the victim (Watts et al. 2006). Her behavior contrasted with that of the West females that attacked Basie.

The attack on Basie also stands out in regard to the involvement of females as aggressors. Given that Basie was greatly outnumbered after the other Central males fled and could not fight back effectively, they and their offspring faced low risks. Females sometimes participate in boundary patrols and aggressive intercommunity interactions (Boesch and Boesch-Achermann 2000; Watts and Mitani 2001). Participation in lethal intergroup attacks is less common, although Gigi, a sterile female, participated in the lethal attack on Kahama male De at Gombe (Goodall 1986; Goodall et al. 1979) and females participated in a lethal attack on an adult male at Taï (Boesch et al. 2008). Females have also been involved in lethal attacks in other nonhuman primates (e.g., red colobus monkeys, Piliocolobus badius: Starin 1994; mountain gorillas, Gorilla beringei: Rosenbaum et al. 2016). Female chimpanzees sometimes engage in serious aggression toward other females in their own communities that can lead to severe wounding and infanticides (e.g., Lowe et al. 2019; Pusey et al. 2008), which may serve to reduce feeding competition (Pusey and Schroepfer-Walker 2013; Pusey et al. 2008). Basie was attacked in an area with a large Aningeria altissima fruit crop, and the particular tree in which members of both communities fed that day attracted chimpanzees for nearly 2 mo. The last visit, by West chimpanzees, was on July 8, 3 weeks after Basie was killed. So far as researchers were aware, no Central males revisited the tree after the attack. Some Central females did, but most recorded visits were by large parties of West chimpanzees, and at least once a party of Central females left the tree when they heard West chimpanzees nearby (the West chimpanzees later fed in the tree). Moreover, most of the West chimpanzees that had fed in that tree on June 15 were feeding in other aningeria in the same general area the next morning. After they left those trees, they heard Central chimpanzees arrive at them. They stalked and attacked the Central party, the members of which fled. Some nonlethal contact aggression happened during the encounter, and West females were involved in chases of Central chimpanzees. They have also been involved in confrontations and contact aggression in other encounters, some of which have happened in areas to which members of both communities were attracted by currently available fruit crops. Escalated and potentially lethal coalitionary intergroup aggression is associated with feeding competition in several other mammals (e.g., red colobus: Starin 1994; lions: Heinsohn 1997; Packer et al. 1990; spotted hyenas, Crocuta crocuta: Boydston et al. 2001). The outcome of such competition affects fitness in lions (Mosser and Packer 2009; Packer et al. 1988), and intracommunity competition can affect the fitness of female chimpanzees (Pusey and Schroepfer-Walker 2013).

That Erroll and Basie were the victims in the two attacks might have been largely due to chance. Erroll was probably traveling with Brownface on the morning he was killed. He had not associated peacefully with West chimpanzees for about 2 yr prior to his death, and both he and Basie had been present at prolonged hostile interactions with West chimpanzees during this time. Erroll was socially peripheral and had never spent much time associating with West chimpanzees, with whom he rarely groomed. Those he encountered on the day of his death treated him as if he were a stranger. In contrast, Basie had long histories of association with three of the adult West males that attacked and they had been among his grooming and coalition partners as recently as 3 yr earlier. This did not prevent them from joining, and even initiating, the attack. The other males also were familiar with Basie, but he was never seen forming coalitions with the five younger adult males and rarely groomed with them, nor did he groom with the adolescent males.

West females Senta, Carson, and Sabin also had long-standing familiarity with Basie, who had copulated with all of them in the past. Moreover, all the attackers were familiar with all the Central chimpanzees present except perhaps adolescent male Puccini and adolescent female Dolly (who immigrated in early 2019). In fact, Central alpha male Jackson had grown up in the original western subgroup; his mother was a western female that died in 2017, and his adolescent maternal half-brother and juvenile maternal half-sister remained West chimpanzees.

The West chimpanzees did not obviously target Basie; they seemed simply to concentrate their attack on whoever they could trap, with previous social relationships irrelevant. Still, they had ample opportunity to recognize him and could have ceased the attack during any of the lulls; instead, they resumed it. They stopped while he was still alive and could move, despite not facing any threat themselves. Likewise, when Ngogo males made a lethal intracommunity attack on male Grapelli in 2002, they ceased the attack while he was still alive (Watts 2004). None of the four adult Kahama males killed by familiar Kasekela males after the community fission at Gombe were killed outright, either (Goodall 1986; Goodall et al. 1979), and Kasekela male Sherry followed Kahama male Sniff for 20 min without engaging in further aggression after the attack on Sniff ended (Goodall 1986). Failure to kill these victims outright might have been an effect of familiarity, but familiarity per se does not necessarily preclude attacks that are immediately fatal (Kaburu et al. 2013).

The behavior of old male Brownface stood out amidst the lethal aggression. He belonged to the western subgroup before the spit and continued to travel between the two incipient communities until late 2017. He had long-term social ties to all adult males present at both attacks, especially with West males Garrison, Rollins, Richmond, with whom he had often groomed and sometimes formed coalitions. Brownface also has long-standing affiliative relationships with Central males Jackson and Basie. Brownface still associated peacefully with West males until several months before the attack on Erroll, and during the part of the attack that one of us witnessed, West males were not aggressive to him. Whether they would have attacked him as seriously as they did Basie if they had caught him instead of Basie is impossible to know.

Brownface’s behavior in the attack on Basie bore some resemblance to the behavior of adult male Hare during the attack on Grapelli in 2002 (Watts 2004). Hare was present when the attack started; he neither joined the attackers nor initially tried to defend Grapelli, but he defended him from further attack after most of the attackers had left and Grapelli found refuge in a small tree. He then followed Grapelli away from the attack site and stayed with him for at least several hours. Brownface did not rejoin Basie until all the attackers were gone, but he then stayed with Basie until the following morning.

In some other respects, the lethal attacks we observed differed from other intracommunity lethal attacks in chimpanzees, including the one seen at Ngogo in 2002 (Watts 2004). The victim in that case, Grapelli, had associated peacefully with at least some of the other Ngogo males that attacked him within the previous 3 weeks, and the attackers were not from a different Ngogo subgroup. A lethal intragroup attack on an adult male at Mahale, Tanzania, started during a grooming bout (Kaburu et al. 2013). The adult victim of a lethal attack at Fongoli, Senegal, was a former alpha male that had been socially peripheral for the 5 yr preceding that attack, but he was not totally out of contact with other males during the time; he was targeted while trying to reintegrate himself into male social networks (Pruetz et al. 2017). These attacks and that on an adolescent male at Sonso (Budongo, Uganda) killed by adults of his own community (Fawcett and Muhumuza 2000) were not associated with long-standing sociospatial subgrouping like that seen at Ngogo, nor did they follow absences of any tolerated association or affiliative interaction between the attackers and the victims that lasted 1.5–2.5 yr. In this respect, the killings of Erroll and Basie more closely resembled killings of strangers in chimpanzees and intraspecific killings of outgroup members in other primates (e.g., white-faced capuchin, Cebus capucinus: Gros-Louis et al. 2003; mountain gorilla, Gorilla beringei: Rosenbaum et al. 2016) and some nonprimates (e.g., wolves, Canis lupus: Cassidy and McIntyre 2016).

The attacks we saw also resembled the string of lethal attacks at Gombe in the 1970s following the Kasekela-Kahama split (Goodall 1986; Goodall et al. 1979). Those led to the extinction of the Kahama community and to a territorial expansion that conferred fitness benefits on Kasekela females (Williams et al. 2004). Whether the permanent fission at Ngogo will lead to more lethal aggression, how the two communities will partition the habitat into two territories, and what impact the fission will have on fitness for both males and females are subject of ongoing investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Chris Aligarya, Charles Birungi, Davis Kalunga, Brian Kamugyisha, Diana Kanweri, Adolph Magoba, Godfrey Mbabazi, Lawrence Ngandizi, Alfred Tumusiime, and Ambrose Twineomujuni for their invaluable assistance with field research at Ngogo. Fieldwork there would not have been possible without the logistical, administrative, and intellectual support of the late Jeremiah Lwanga and of Samuel Angedakin. We gratefully acknowledge the support and collaboration of John Mitani and Kevin Langergraber. Isabelle Clark provided key assistance in the field from 2017 to 2018 when the first lethal attack was observed. We also thank Sharifah Namaganda, Kevin Lee, Sebastian Ramirez Amaya, and Dr. Timothy Mugabe. We thank Makerere University, the Uganda Wildlife Authority, and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology for permission to work in Kibale National Park. Special thanks to Aggrey Rwetsiba, Nelson Guma, Edward Asalu, and Hillary Agaba. Data from Ngogo were collected with support from NSF grants BCS-0215622, IOB-0516644, 1540259, and F031543; National Institutes of Health grant RO1AG049395; the L. S. B. Leakey Foundation; the National Geographic Society; Arizona State University; the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology; the University of Michigan; the University of Texas at Austin; and Yale University. For comments on earlier versions of the manuscript we thank Joanna Setchell and two anonymous reviewers.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-020-00185-0.

References

- Boesch C, & Boesch-Achermann H (2000). The chimpanzees of the Taï forest: behavioural ecology and evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boesch C, Crockford C, Herbinger I, Wittig R, Moebius Y, & Normand E (2008). Intergroup conflicts among chimpanzees in Tai National Park: Lethal violence and the female perspective. American Journal of Primatology, 70, 519–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boydston EE, Morelli TL, & Holekamp KE (2001). Sex differences in territorial behavior exhibited by the spotted hyena (Hyaenidae, Crocuta crocuta). Ethology, 107, 369–385. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy KA, & McIntyre RT (2016). Do gray wolves (Canis lupus) support pack mates during aggressive inter-pack interactions? Animal Cognition, 19, 939–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cords M (2012). The 30-year blues: What we know and don’t know about life history, group size, and group fission of blue monkeys in the Kakamega Forest, Kenya. In Kappeler PM & Watts DP (Eds.), Long-term field studies of primates. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Creel S, & Creel NM (2002). The african wild dog: behavior, ecology, and conservation. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Cubaynes S, MacNulty DR, Stahler DR, Quimby KA, Smith DW, & Coulson T (2014). Density-dependent intraspecific aggression regulates survival in northern Yellowstone wolves (Canis lupus). Journal of Animal Ecology, 83, 1344–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett K, & Muhumuza G (2000). Death of a wild chimpanzee community member: Possible outcome of intense sexual competition. American Journal of Primatology, 51, 243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldblum JT, Manfredi S, Gilby IC, & Pusey AE (2018). The timing and causes of a unique chimpanzee community fission preceding Gombe's “Four-Year War”. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 166, 730–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilby IC, Brent LJN, Wroblewski EE, Rudicell RS, Hahn BH, et al. (2013). Fitness benefits of coalitionary aggression in male chimpanzees. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 67, 373–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez JM, Verdú M, González-Megías A, & Méndez M (2016). The phylogenetic roots of human lethal violence. Nature, 538, 233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall J (1979). Life and death at Gombe. National Geographic, 155, 592–620. [Google Scholar]

- Goodall J (1986). The chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goodall J, Bandura A, Bergmann E, Busse C, Matam H, et al. (1979). Inter-community interactions in the chimpanzee populations of the Gombe National Park. In Hamburg D & McCown E (Eds.), The great apes (pp. 13–53). Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin/Cummings. [Google Scholar]

- Gros-Louis J, Perry S, & Manson JH (2003). Violent coalitionary attacks and intraspecific killing in wild white-faced capuchin monkeys (Cebus capucinus). Primates, 44, 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinsohn R (1997). Group territoriality in two populations of African lions. Animal Behaviour, 53, 1143–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrdy SB (1979). Infanticide among animals: A review, classification, and examination of the implications for the reproductive strategies of females. Ethology and Sociobiology, 1, 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu MJ, Lin J-F, & Agoramoorthy G (2017). Social implications of fission in wild Formosan macaques at Mount Longevity, Taiwan. Primates, 58, 323–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaburu SS, Inoue S, & Newton-Fisher NE (2013). Death of the alpha: Within-community lethal violence among chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains National Park. American Journal of Primatology, 75, 789–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langergraber K, Mitani J, & Vigilant L (2007). The limited impact of kinship on cooperation in wild chimpanzees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 104, 7786–7790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langergraber K, Mitani J, Watts D, & Vigilant L (2013). Male-female socio-spatial relationships and reproduction in wild chimpanzees. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 67, 861–873. [Google Scholar]

- Langergraber KE, Rowney C, Schubert G, Crockford C, Hobaiter C, et al. (2014). How old are chimpanzee communities? Time to the most recent common ancestor of the Y-chromosome in highly patrilocal societies. Journal of Human Evolution, 69, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langergraber KE, Watts DP, Vigilant L, & Mitani JC (2017). Group augmentation, collective action, and territorial boundary patrols by male chimpanzees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 114, 7337–7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe AE, Hobaiter C, & Newton-Fisher NE (2019). Countering infanticide: Chimpanzee mothers are sensitive to the relative risks posed by males on differing rank trajectories. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 168, 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson JH, Wrangham RW, Boone JL, Chapais B, Dunbar R, et al. (1991). Intergroup aggression in chimpanzees and humans [and comments and replies]. Current Anthropology, 32, 369–390. [Google Scholar]

- Markham CA, & Gesquiere LR (2017). Costs and benefits of group living in primates: An energetic perspective. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372, 20160239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani J (2009a). Cooperation and competition in chimpanzees: Current understanding and future challenges. Evolutionary Anthropology, 18, 215–227. [Google Scholar]

- Mitani J (2009b). Male chimpanzees form enduring and equitable social bonds. Animal Behaviour, 77, 633–640. [Google Scholar]

- Mitani J, Watts D, & Amsler S (2010). Lethal intergroup aggression leads to territorial expansion in wild chimpanzees. Current Biology, 20, R507–R508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani JC (2020). My life among the apes. American Journal of Primatology, e23107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani JC, & Amsler SJ (2003). Social and spatial aspects of male subgrouping in a community of wild chimpanzees. Behaviour, 140, 869–884. [Google Scholar]

- Mitani JC, & Watts DP (2005). Correlates of territorial boundary patrol behaviour in wild chimpanzees. Animal Behaviour, 70, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Mosser A, & Packer C (2009). Group territoriality and the benefits of sociality in the African lion, Panthera leo. Animal Behaviour, 78, 359–370. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T (1979). The social structure of chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains. In Hamburg D & McCown E (Eds.), The great apes. Benjamin/Cummings: Menlo Park, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T (1996). The death of Ntologi, the unparalleled leader of M group. Pan Africa News, 3, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T, & Hosaka K (1996). Coalition strategies among adult male chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains, Tanzania. In McGrew W, Marchant L, & Nishida T (Eds.), Great ape societies (pp. 114–134). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Packer C, Herbst L, Pusey AE, Bygott JD, Hanby J, et al. (1988). Reproductive success in lions. In Clutton-Brock TH (Ed.), Reproductive success: Studies of individual variation in contrasting breeding systems (pp. 363–383). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Packer C, Scheel D, & Pusey AE (1990). Why lions form groups: Food is not enough. The American Naturalist, 136, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pruetz JD, Ontl KB, Cleaveland E, Lindshield S, Marshack J, & Wessling EG (2017). Intragroup lethal aggression in West African chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus): inferred killing of a former alpha male at Fongoli, Senegal. International Journal of Primatology, 38, 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pusey A, Murray C, Wallauer W, Wilson M, Wroblewski E, & Goodall J (2008). Severe aggression among female Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii at Gombe National Park, Tanzania. International Journal of Primatology, 29, 949–973. [Google Scholar]

- Pusey AE, & Packer C (1987). The evolution of sex-biased dispersal in lions. Behaviour, 101, 275–310. [Google Scholar]

- Pusey AE, & Schroepfer-Walker K (2013). Female competition in chimpanzees. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368, 20130077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum S, Vecellio V, & Stoinski T (2016). Observations of severe and lethal coalitionary attacks in wild mountain gorillas. Scientific Reports, 6, 37018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starin ED (1994). Philopatry and affiliation among red colobus. Behaviour, 130, 253–270. [Google Scholar]

- Tokuda M, Boubli JP, Mourthe I, Izar P, Possamai CB, & Strier KB (2014). Males follow females during fissioning of a group of northern muriquis. American Journal of Primatology, 76, 529–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Waal E, van Schaik CP, & Whiten A (2017). Resilience of experimentally seeded dietary traditions in wild vervets: Evidence from group fissions. American Journal of Primatology, 79, e22687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderWaal KL, Mosser A, & Packer C (2009). Optimal group size, dispersal decisions and postdispersal relationships in female African lions. Animal Behaviour, 77, 949–954. [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn RC, Buchan JC, Altmann J, & Alberts SC (2007). Divided destinies: group choice by female savannah baboons during social group fission. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 61, 1823–1837. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield ML (2008). Grouping patterns and competition among female Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda. International Journal of Primatology, 29, 907–929. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield ML (2013). Social dynamics among females and their influence on social structure in an East African chimpanzee community. Animal Behaviour, 85, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar]

- Watts DP (2004). Intracommunity coalitionary killing of an adult male chimpanzee at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda. International Journal of Primatology, 25, 507–521. [Google Scholar]

- Watts DP (2012). Long-term research on chimpanzee behavioral ecology in Kibale National Park, Uganda. In Kappeler PM & Watts DP (Eds.), Long-term field studies of primates. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Watts DP (2018). Male dominance relationships in an extremely large chimpanzee community at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda. Behaviour, 155, 969–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Watts DP, & Mitani JC (2001). Boundary patrols and intergroup encounters in wild chimpanzees. Behaviour, 138, 299–327. [Google Scholar]

- Watts DP, Muller M, Amsler SJ, Mbabazi G, & Mitani JC (2006). Lethal intergroup aggression by chimpanzees in Kibale National Park, Uganda. American Journal of Primatology, 68, 161–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Oehlert G, Carlis J, & Pusey A (2004). Why do male chimpanzees defend a group range? Animal Behaviour, 68, 523–532. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson ML, Boesch C, Fruth B, Furuichi T, Gilby IC, et al. (2014). Lethal aggression in Pan is better explained by adaptive strategies than human impacts. Nature, 513, 414–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson ML, & Wrangham RW (2003). Intergroup relations in chimpanzees. Annual Review of Anthropology, 32, 363–392. [Google Scholar]

- Wood BM, Watts DP, Mitani JC, & Langergraber KE (2017). Favorable ecological circumstances promote life expectancy in chimpanzees similar to that of human hunter-gatherers. Journal of Human Evolution, 105, 41–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrangham RW (1999). Evolution of coalitionary killing. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 110, 1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.