Abstract

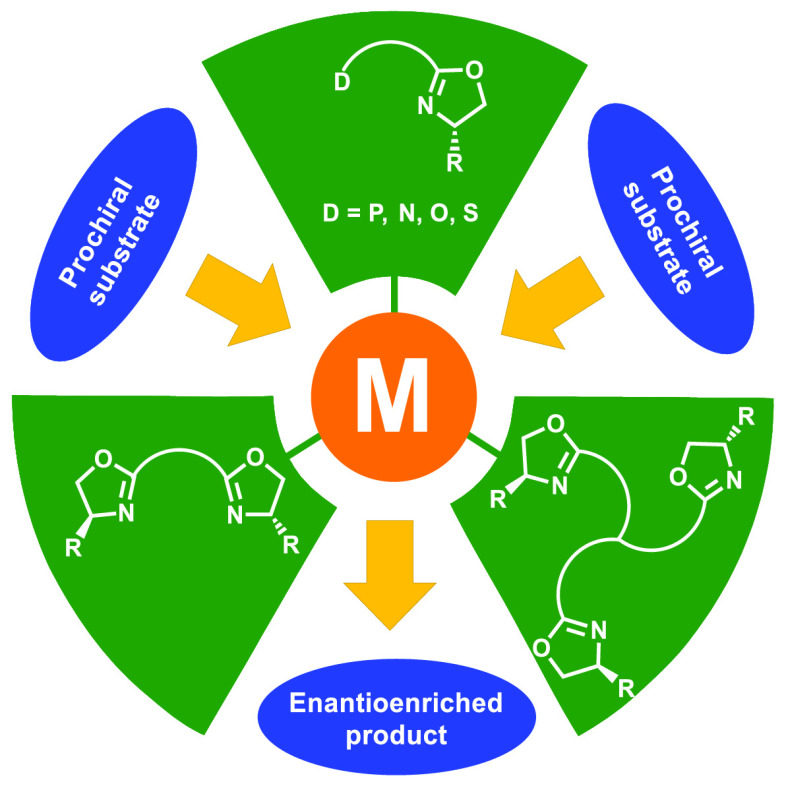

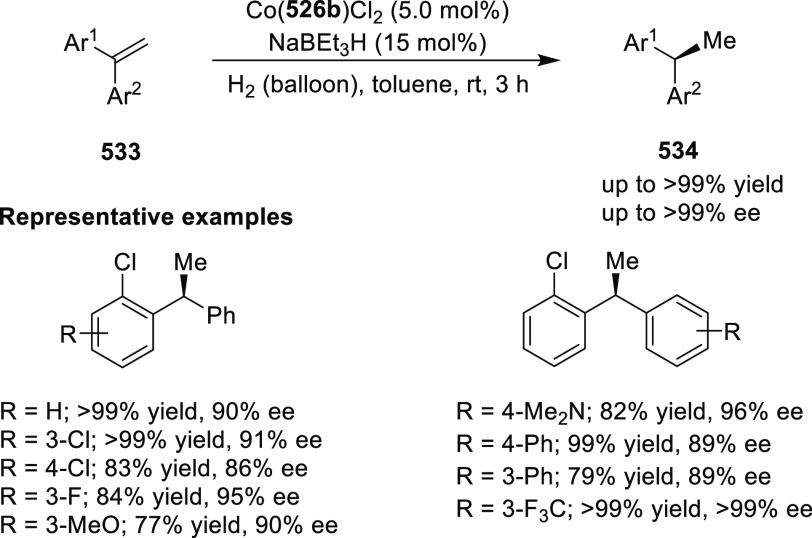

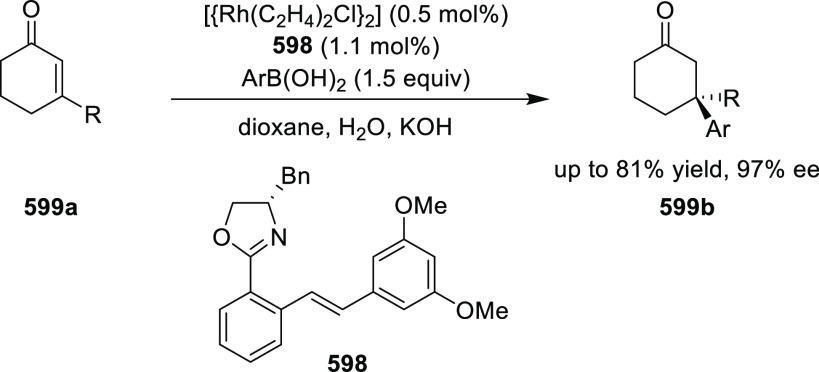

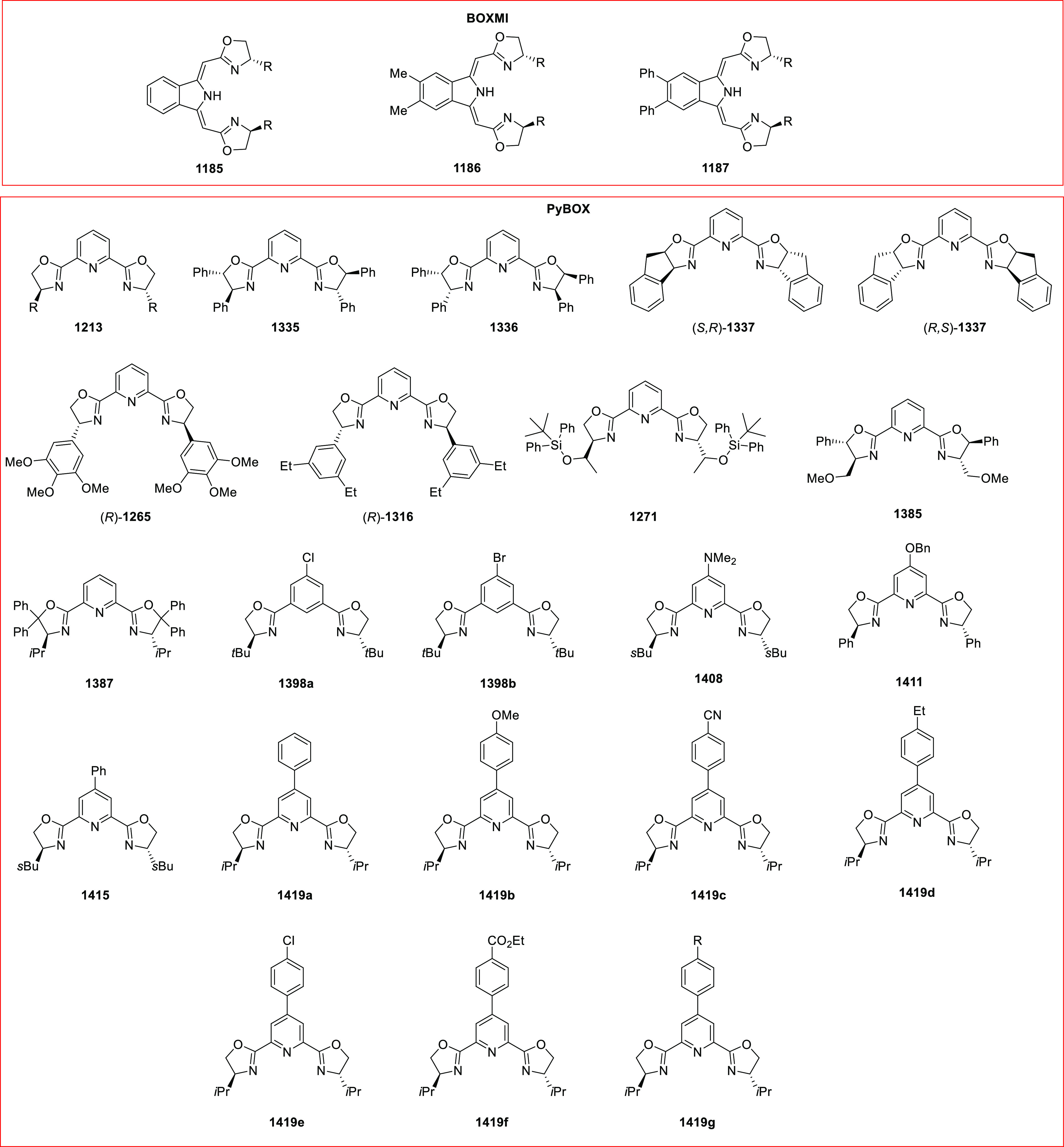

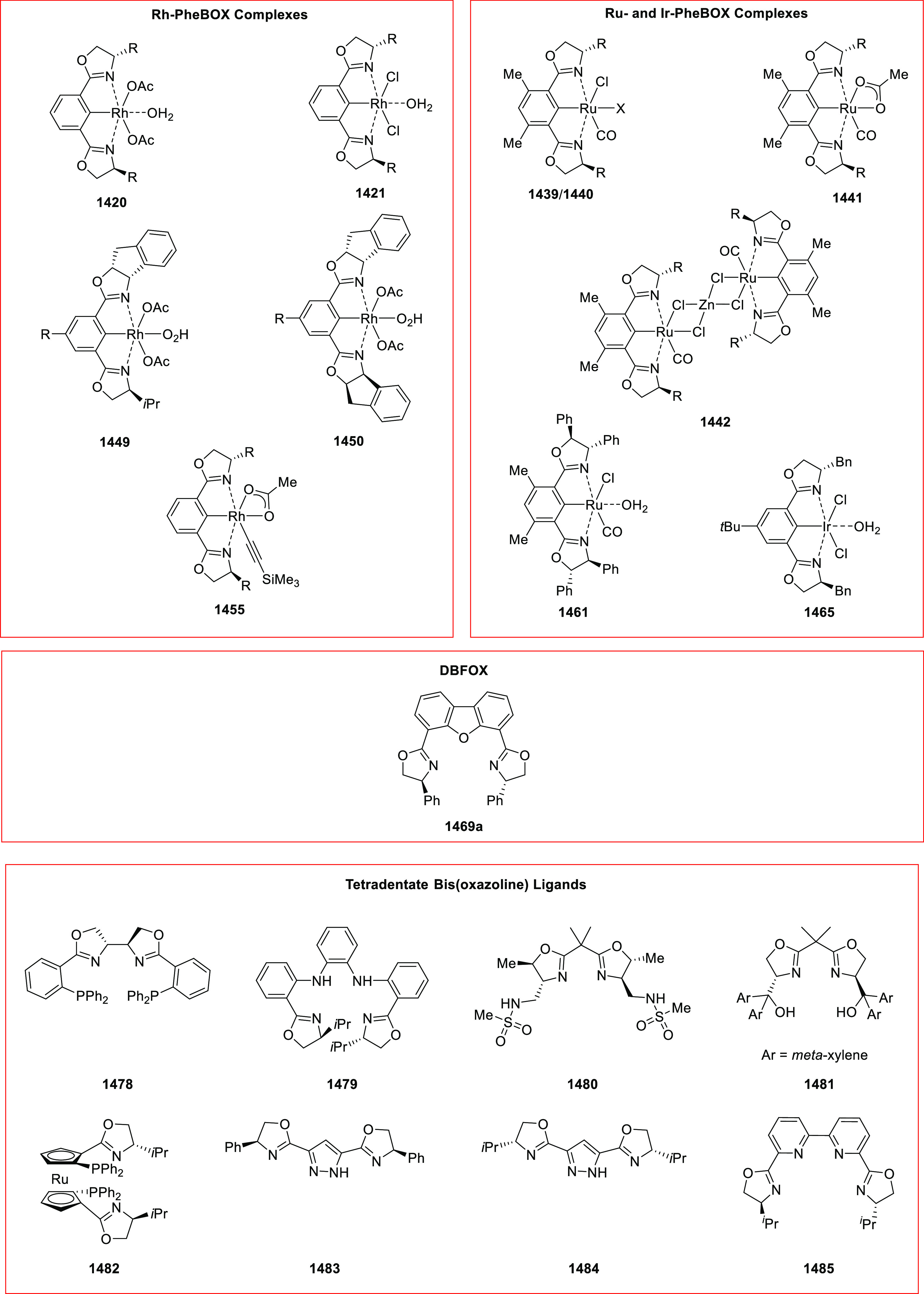

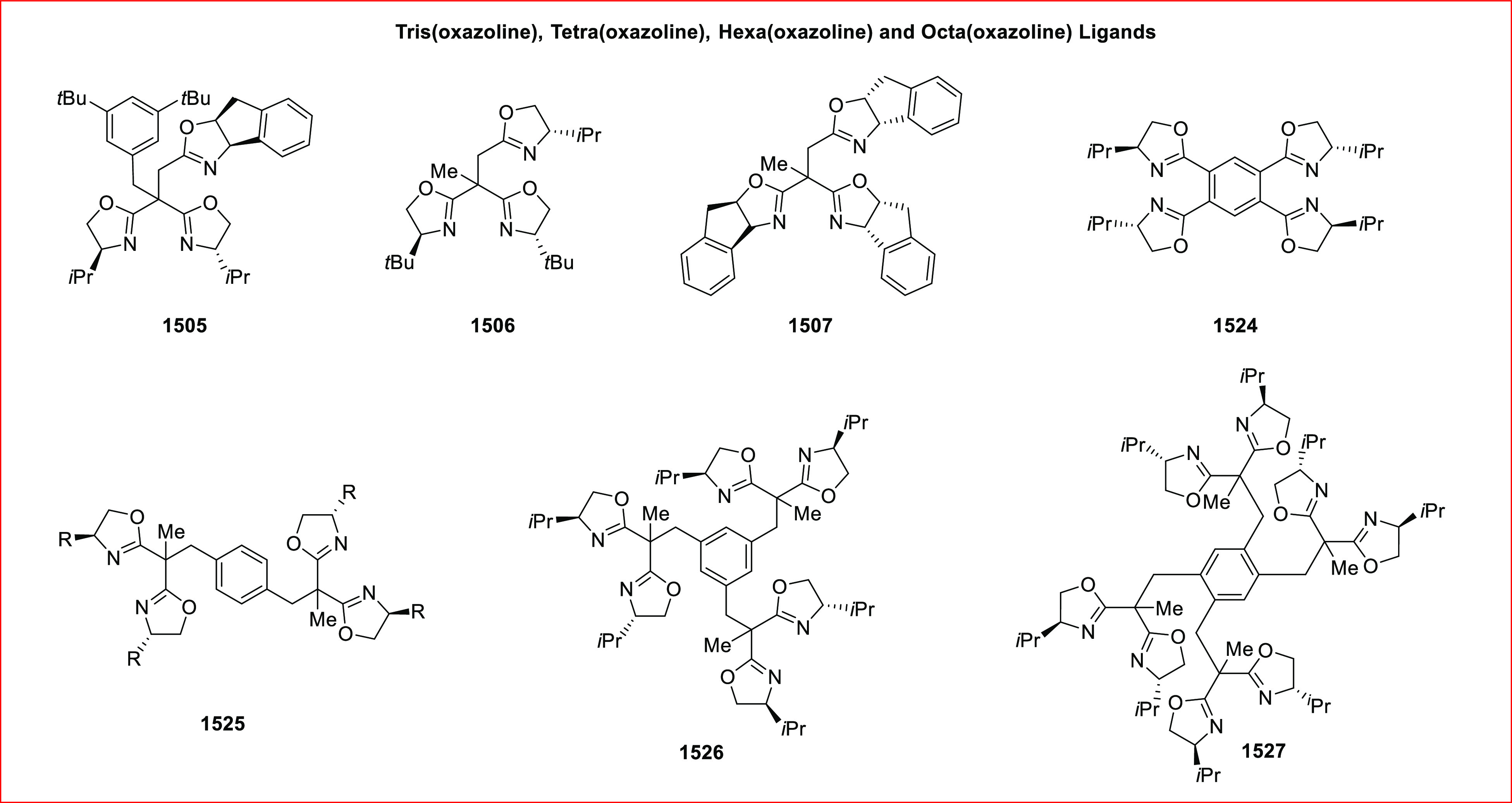

The chiral oxazoline motif is present in many ligands that have been extensively applied in a series of important metal-catalyzed enantioselective reactions. This Review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the most significant applications of oxazoline-containing ligands reported in the literature starting from 2009 until the end of 2018. The ligands are classified not by the reaction to which their metal complexes have been applied but by the nature of the denticity, chirality, and donor atoms involved. As a result, the continued development of ligand architectural design from mono(oxazolines), to bis(oxazolines), to tris(oxazolines) and tetra(oxazolines) and variations thereof can be more easily monitored by the reader. In addition, the key transition states of selected asymmetric transformations will be given to illustrate the features that give rise to high levels of asymmetric induction. As a further aid to the reader, we summarize the majority of schemes with representative examples that highlight the variation in % yields and % ees for carefully selected substrates. This Review should be of particular interest to the experts in the field but also serve as a useful starting point to new researchers in this area. It is hoped that this Review will stimulate both the development/design of new ligands and their applications in novel metal-catalyzed asymmetric transformations.

1. Introduction

Ligands containing a chiral oxazoline are some of the most successful, versatile, and commonly used ligand classes in asymmetric catalysis due to their ready accessibility, modular nature, and applicability in a wide range of metal-catalyzed transformations.

The vast majority of these ligands are formed in short, high yielding synthesis from readily available chiral β-amino alcohols. Therefore, the stereocenter controlling the enantioselectivity of the metal-catalyzed process resides α- to the oxazolinyl nitrogen donor and, as a result, is in close proximity to the metal active site to directly influence the asymmetry induced in the reaction.

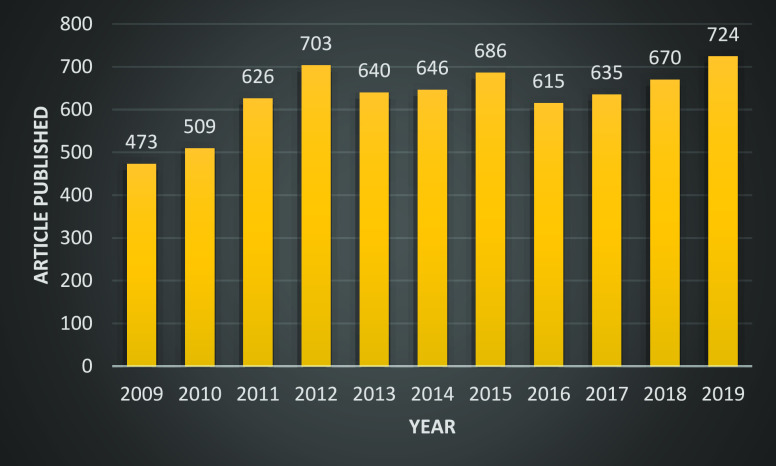

Since the first report of chiral oxazoline-based ligands in asymmetric catalysis in 1986, an enormous range of ligands containing one, two, three or four oxazolines incorporating various heteroatoms, additional chiral elements and other specific structural features have been subsequently developed with great success in a significant range of asymmetric reactions. SciFinder data for the years 2009 to 2019 confirm the significance of research related to the term “oxazoline” (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

SciFinder data on oxazoline-related research for the years 2009 to 2019.

This review reports on the use of such ligands in homogeneous metal-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis since 2009, when the area was last reviewed by us.1 This review does not cover the application of such ligands in heterogeneous systems or in the synthesis of polymers. We cover, in our view, the most significant applications of oxazoline-containing ligands reported in the literature until the end of 2018. This review will be structured in the same manner as our 20042 and 2009 reviews as we classify ligands, not by the reaction to which their metal complexes have been applied, but by the nature of the denticity, chirality and donor atoms involved. As a result, the continued development of ligand architectural design can be more easily monitored. In addition, the key transition states of selected asymmetric transformations employing metal complexes of oxazoline ligands will be given to illustrate the features that give rise to high levels of asymmetric induction. As a further aid to the reader, we summarize the majority of schemes with representative examples which highlight the variation in % yields and % ees for carefully selected substrates.

2. Mono(oxazoline) Ligands

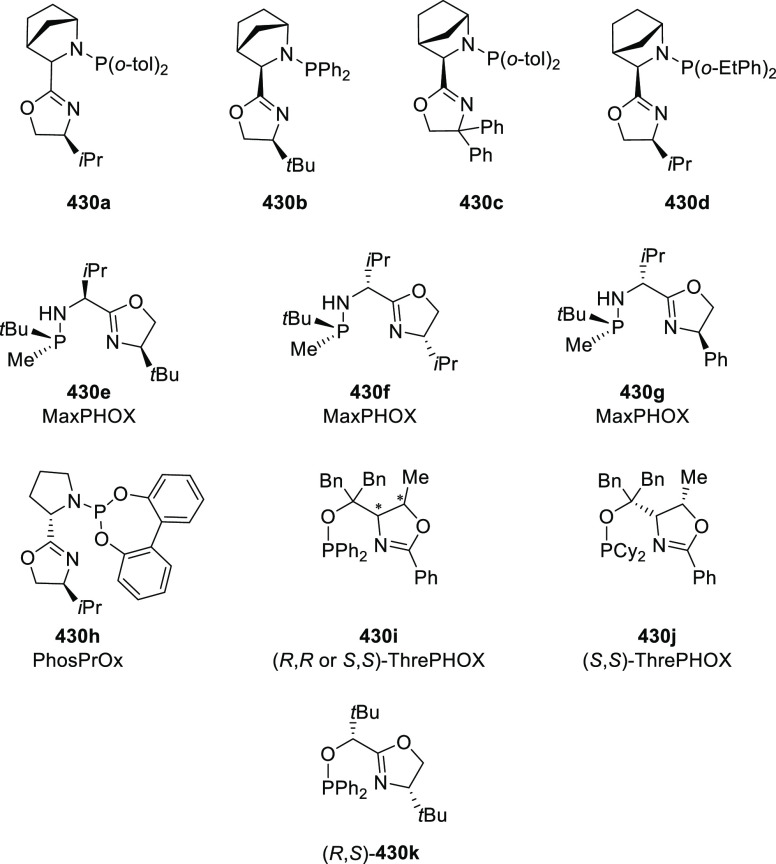

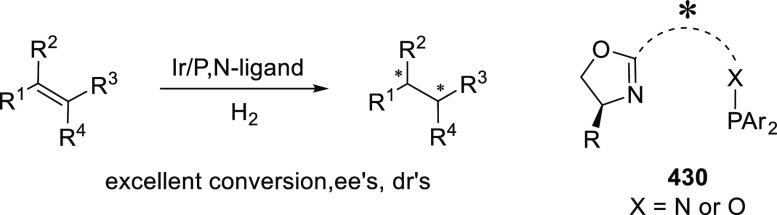

2.1. Mono(oxazoline) P,N-Ligands (Phosphinooxazoline)

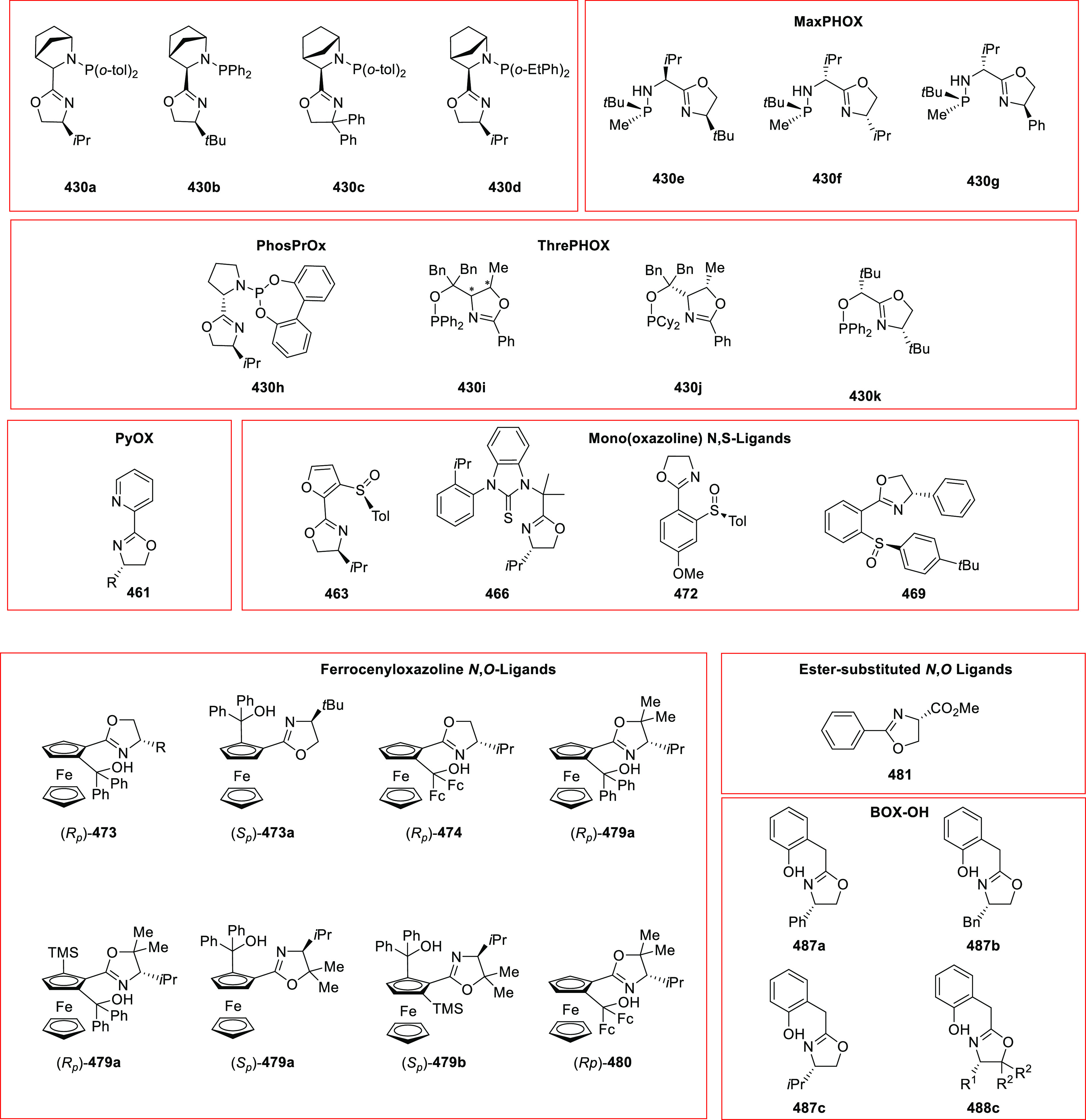

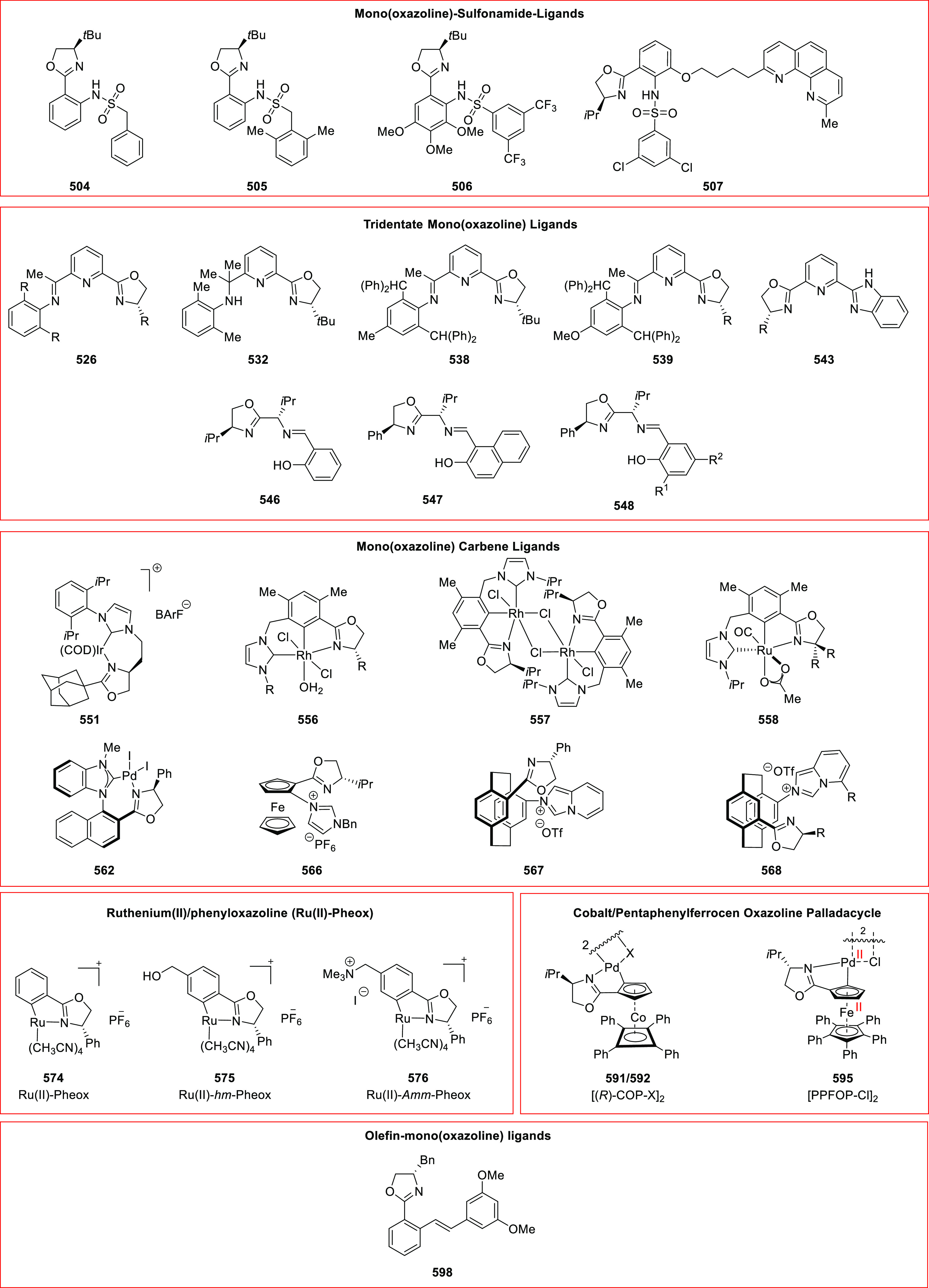

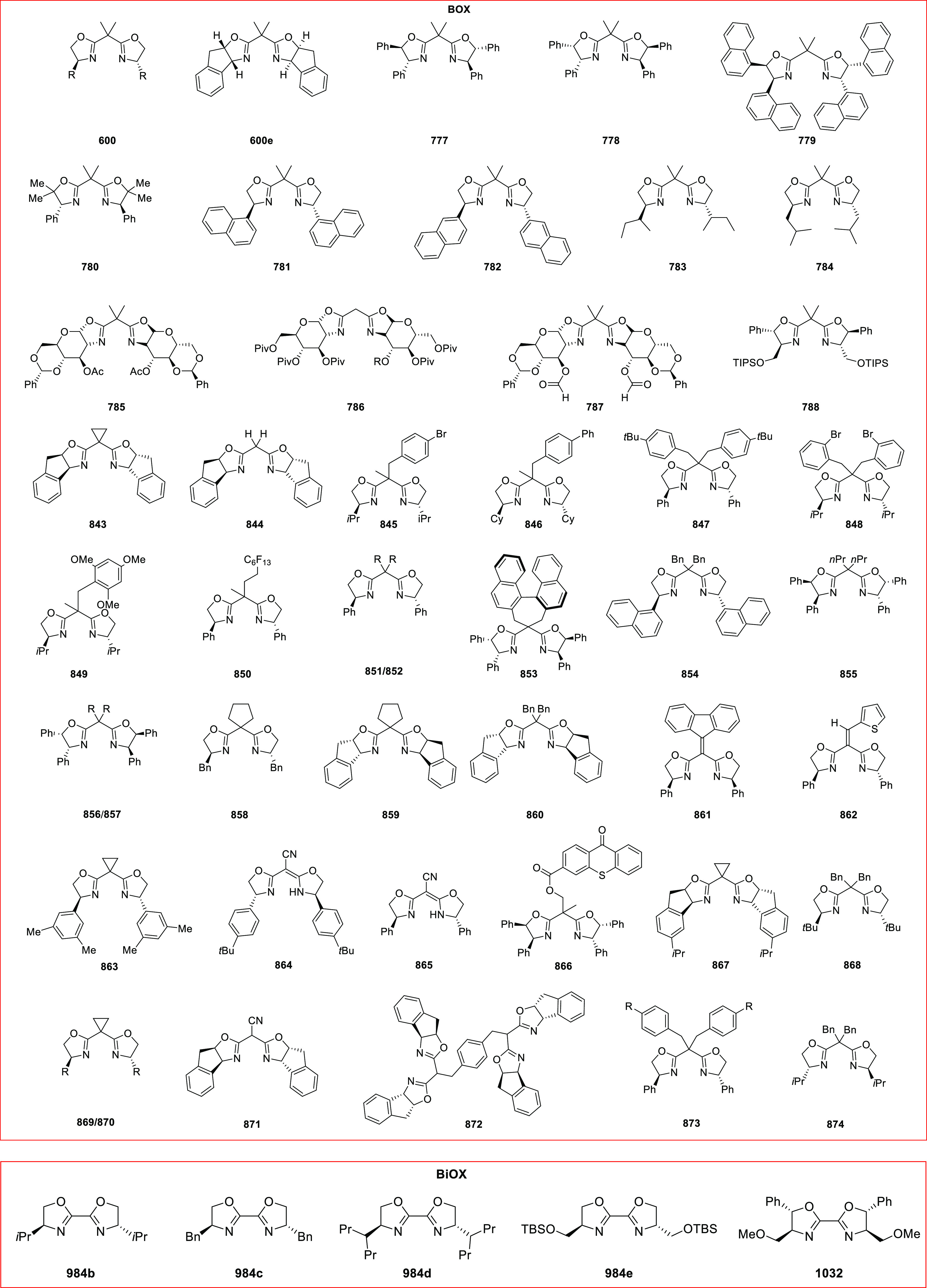

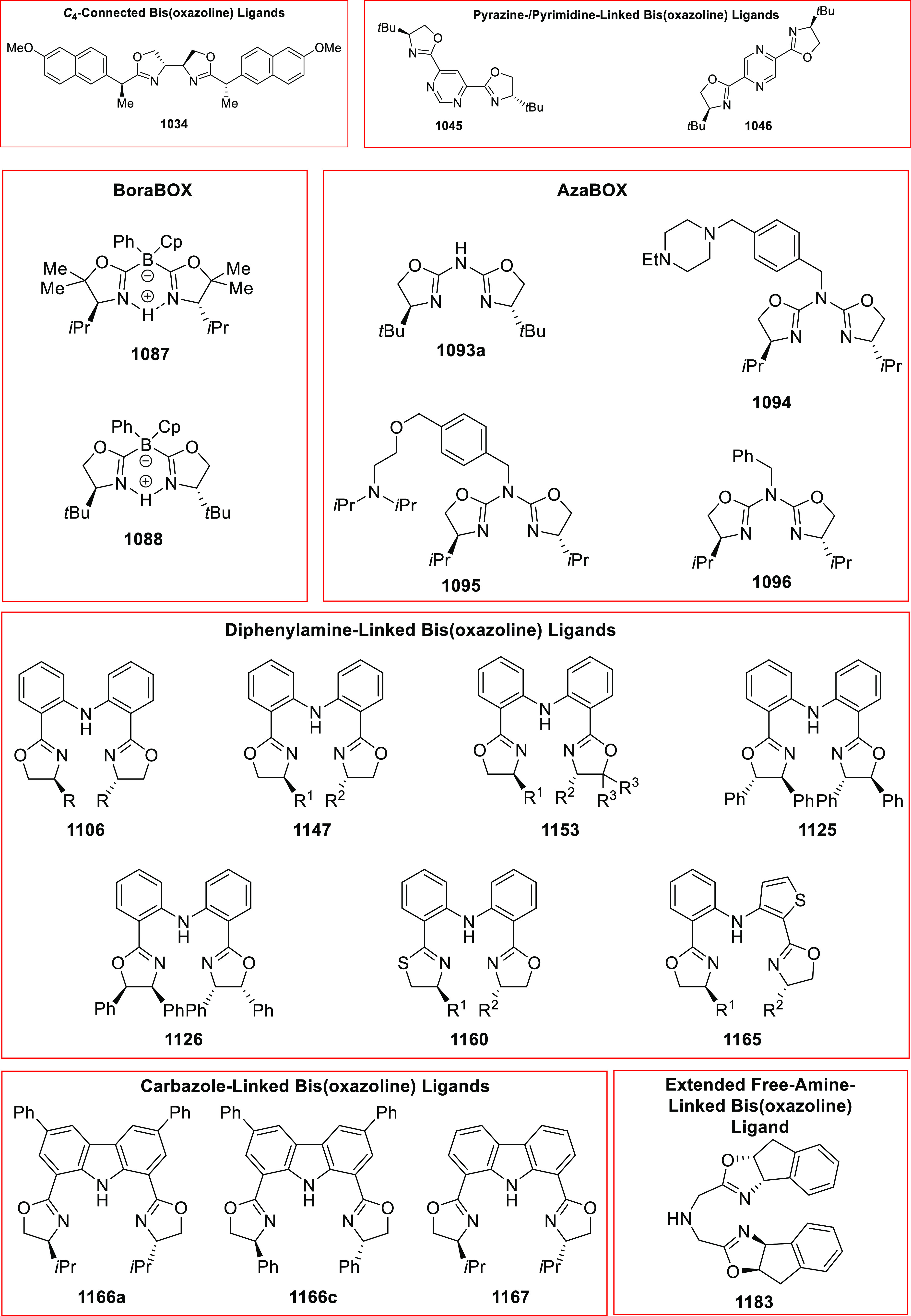

2.1.1. Phosphinooxazoline Ligands with One Stereocenter

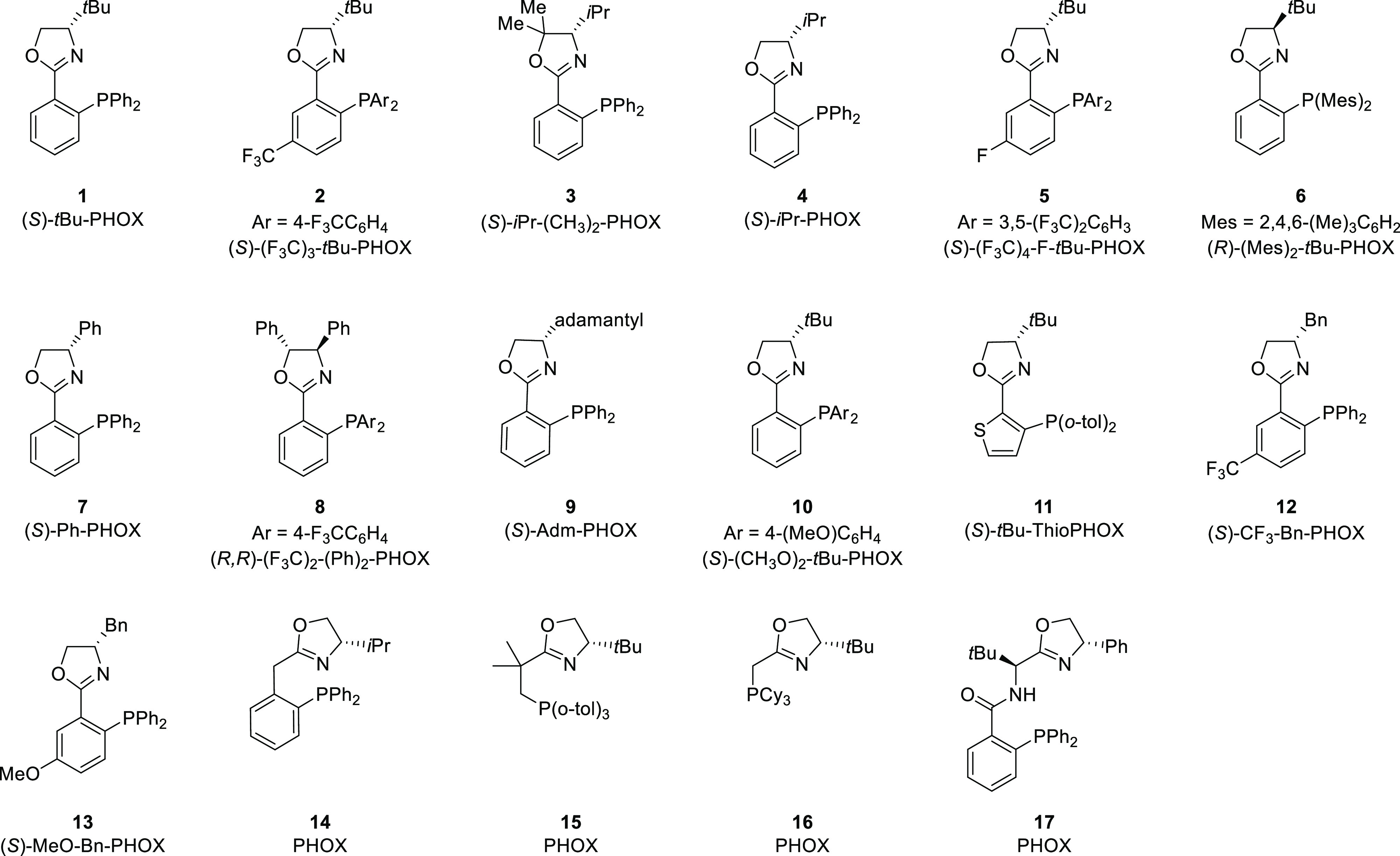

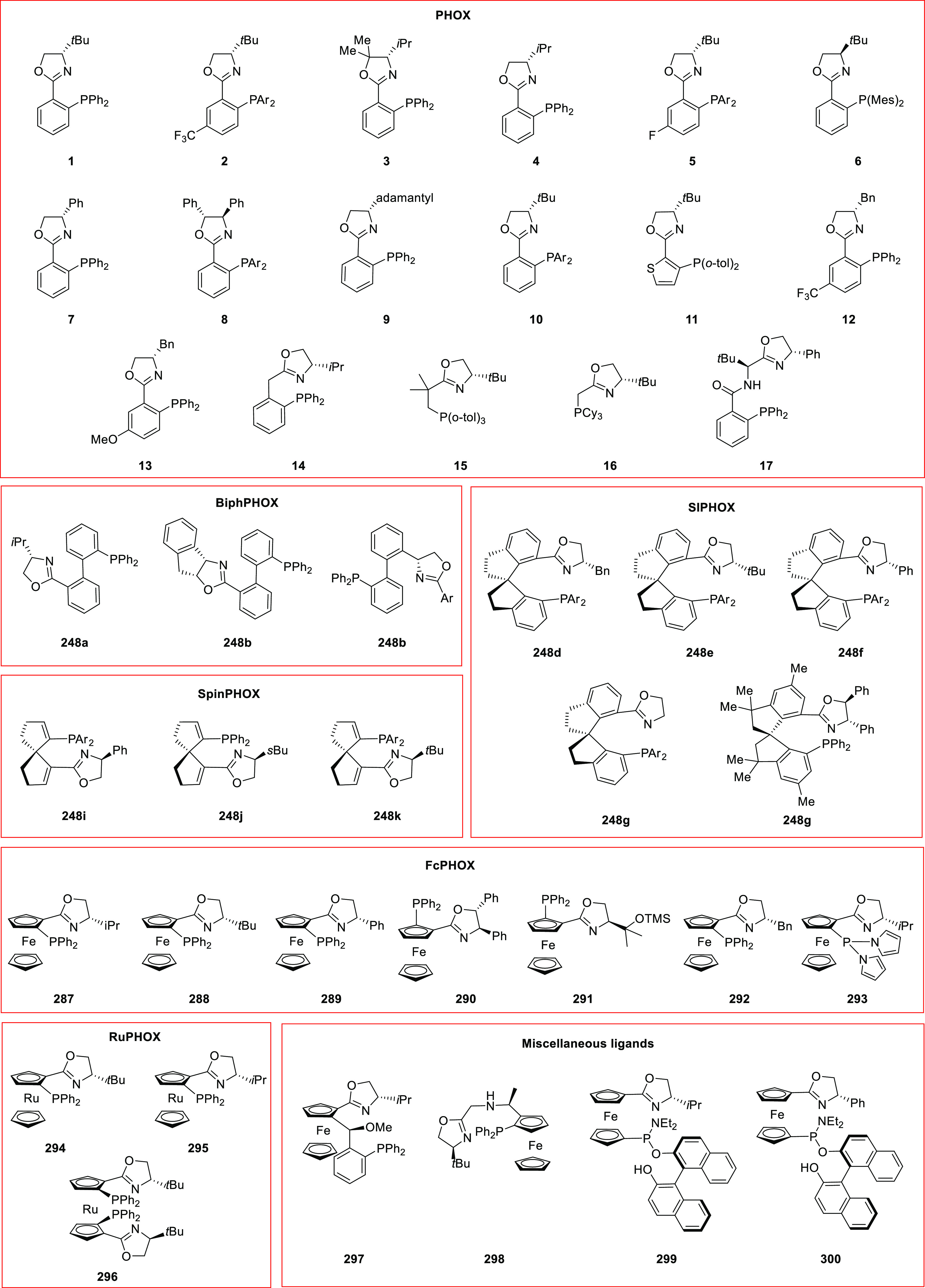

Phosphinooxazoline (PHOX) is a popular class of bidentate ligand in which the chiral oxazoline moiety is solely responsible for asymmetric induction in product formation (Figure 2).3−6 In this section, various PHOX ligands (1–17) and their applications in a broad range of asymmetric transformations will be discussed. This section is further divided into subsections based on the type of reactions the metal complexes of PHOX ligands have been used for.

Figure 2.

Various phosphinooxazoline (PHOX) ligands

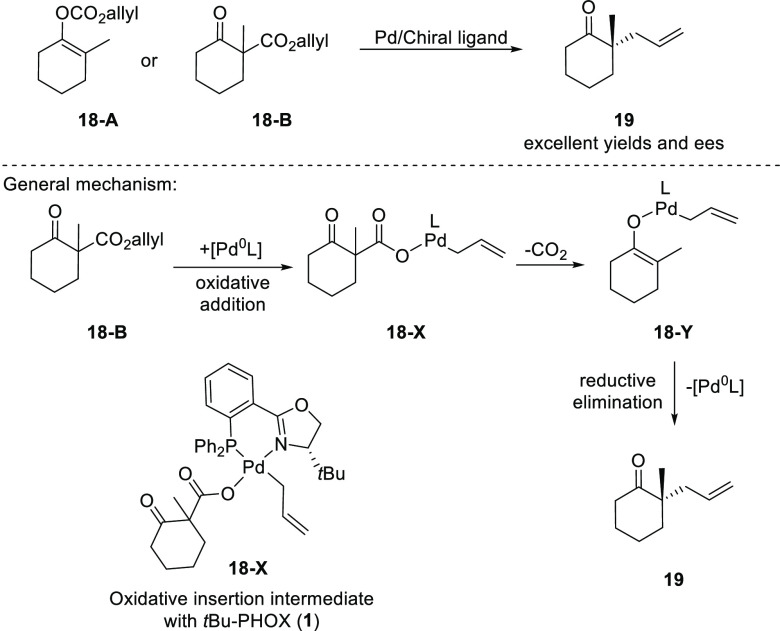

2.1.1.1. Applications of PHOX in Asymmetric Allylation

In late 2004, Stoltz and Trost independently developed a Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative asymmetric allylic alkylation (DAAA) reaction using tBu-PHOX (1) and Trost-type ligands, respectively (Scheme 1).7,8 The generally accepted mechanism of the DAAA involves the coordination of the Pd(0) complex to the allyl moiety leading to oxidative addition, followed by the loss of CO2 to generate the Pd enolate 18-Y, which then attacks the intermediate allyl group to form the enantioenriched product 19 and regenerate the Pd(0) catalyst.9

Scheme 1. Decarboxylative Asymmetric Allylic Alkylation (DAAA).

Since the seminal report from Stoltz, the scope and application of PHOX ligand in DAAA has been expanded to different substrate classes and also in natural products synthesis.

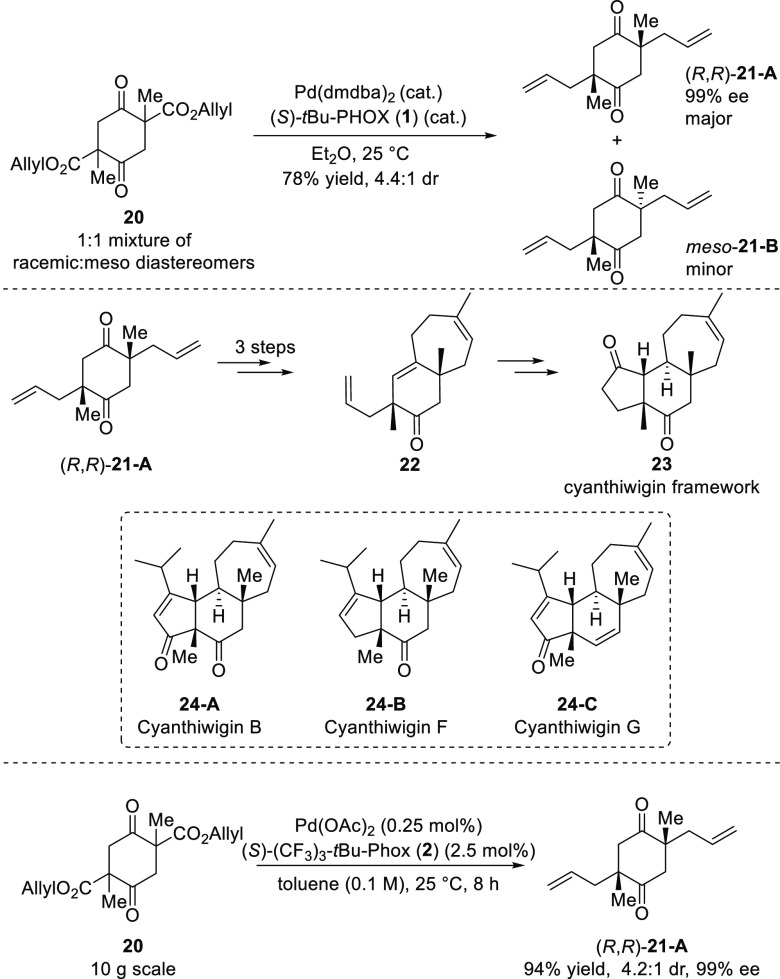

In 2008, Stoltz described a concise and versatile strategy for the preparation of the natural products, cyanthiwigin B, F and G by using a key double stereoablative decarboxylative asymmetric allylic alkylation of bis(β-keto ester) 20 (Scheme 2).10,11 Their strategy involved the synthesis of the central six-membered ring, cyclohexadione 21, with a special emphasis on the early installation of two of the most critical stereocenters of the cyanthiwigin framework in good yield with a high level of stereoselectivity (4.4:1 dr and 99% ee). The major diastereomer of cyclohexadione (R,R)-21-A was subsequently converted for the efficient synthesis of cyanthiwigin B (24-A), F (24-B), and G (24-C). It is worthwhile noting that the observed selectivity in the double decarboxylative allylation with the (S)-tBu-PHOX (1) ligand was excellent given the fact that the reaction begins with a complicated mixture of racemic and meso-diastereomers which leads to several possible stereochemical outcomes, and pathways.

Scheme 2. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Tricyclic Cyanthiwigin Framework.

The key double catalytic enantioselective alkylation was troublesome on a large scale due to the poor solubility of the catalyst which required low reaction concentrations (0.01 M). This problem was improved significantly in their subsequent report wherein the enantioselective alkylation was carried out on a 10 g scale furnishing the desired diketone (R,R)-21-A in 94% yield, 4.2:1 dr and 99% ee.12

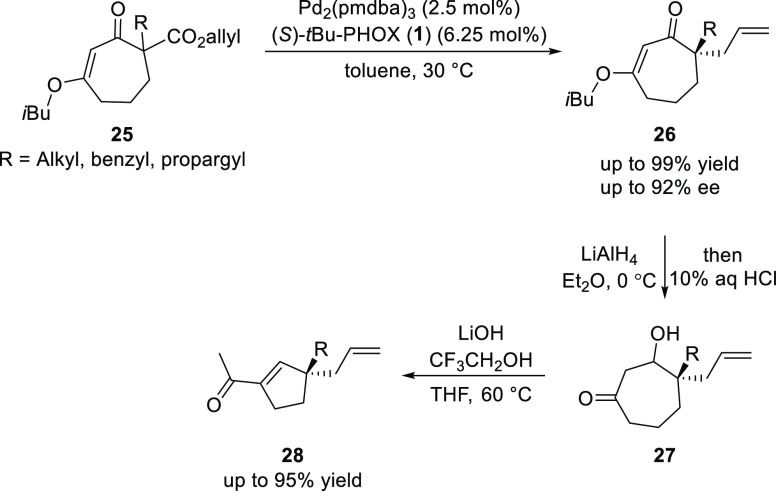

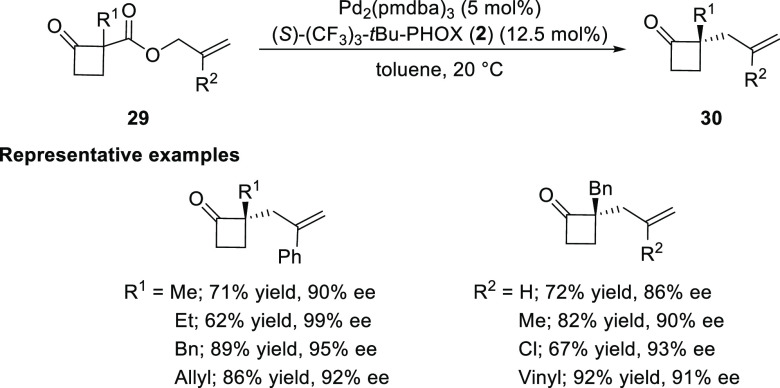

Stoltz extended DAAA to seven membered cyclic β-keto-allyl ester (25) to generate allylated products (26), which were further employed in the asymmetric synthesis of densely functionalized acylcyclopentenes (28), valuable intermediates for the synthesis of natural products, in excellent yields (up to 99%) and high enantioselectivities (up to 92% ee) (Scheme 3).13 The synthesis of 28 from 25 involves a Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative asymmetric allylic alkylation followed by a two-carbon ring contraction.

Scheme 3. Asymmetric Synthesis of Densely Functionalized Acylcyclopentenes.

Later in 2013, Stoltz reported a Pd-catalyzed enantioselective α-alkylation to cyclobutanones (30). The palladium complex of an electron-deficient (S)-(CF3)3-tBu-PHOX (2) ligand demonstrated excellent catalytic activity to afford α-quaternary cyclobutanones in good to excellent yields and enantioselectivities (Scheme 4).14 A wide variety of substituents were compatible at both the α-keto and 2-allyl positions especially considering the presence of highly electrophilic cyclobutanones. Furthermore, chiral cyclobutanones were converted into dialkyl γ-lactams, dialkyl γ-lactones, α-quaternary cyclopentanones, and quaternary [4.5]-spirocycles.

Scheme 4. Enantioselective α-Alkylation of Cyclobutanones.

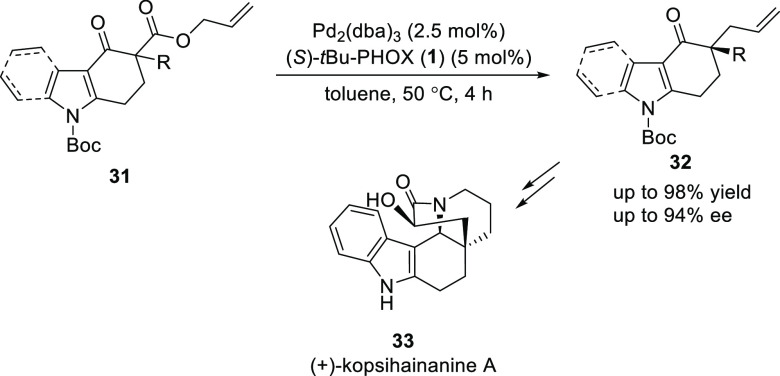

In 2013, Lupton reported a Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative asymmetric allylation for the enantioselective synthesis of carbazolone and indolone heterocycles (32) (Scheme 5).15 A variety of carbazolones and indolones containing a quaternary carbon center were synthesized in excellent yields (up to 98%) and enantioselectivities (up to 94% ee). Moreover, the application of this methodology was shown in the synthesis of (+)-kopsihainanine (33).

Scheme 5. Catalytic Decarboxylative Asymmetric Allylation of Carbazolones and Indolones.

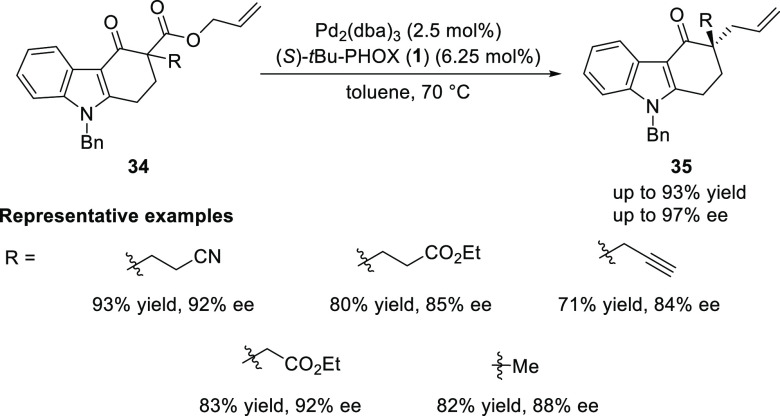

In 2013, Shao reported the Pd-catalyzed enantioselective decarboxylative allylic alkylation of carbazolone heterocycles (34) (Scheme 6).16 A variety of highly functionalized chiral carbazolones (35) featuring an α-quaternary carbon center were synthesized in good yields (up to 93%) with high levels of enantioselectivity (up to 97% ee).

Scheme 6. Catalytic Decarboxylative Asymmetric Allylation of Carbazolones.

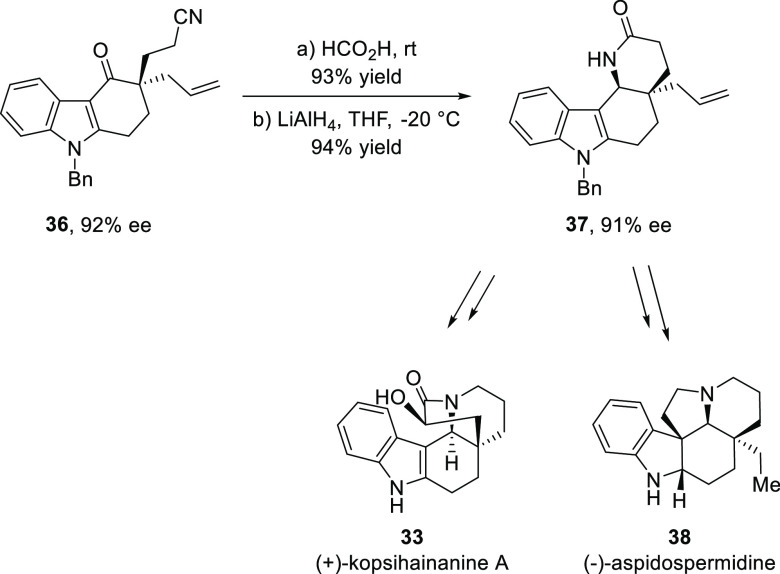

Using this methodology, a catalytic asymmetric strategy for the synthesis of (+)-kopsihainanine A (33) and (−)-aspidospermidine (38) was accomplished from a common intermediate (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of (−)-Aspidospermidine and (+)-Kopsihainanine A.

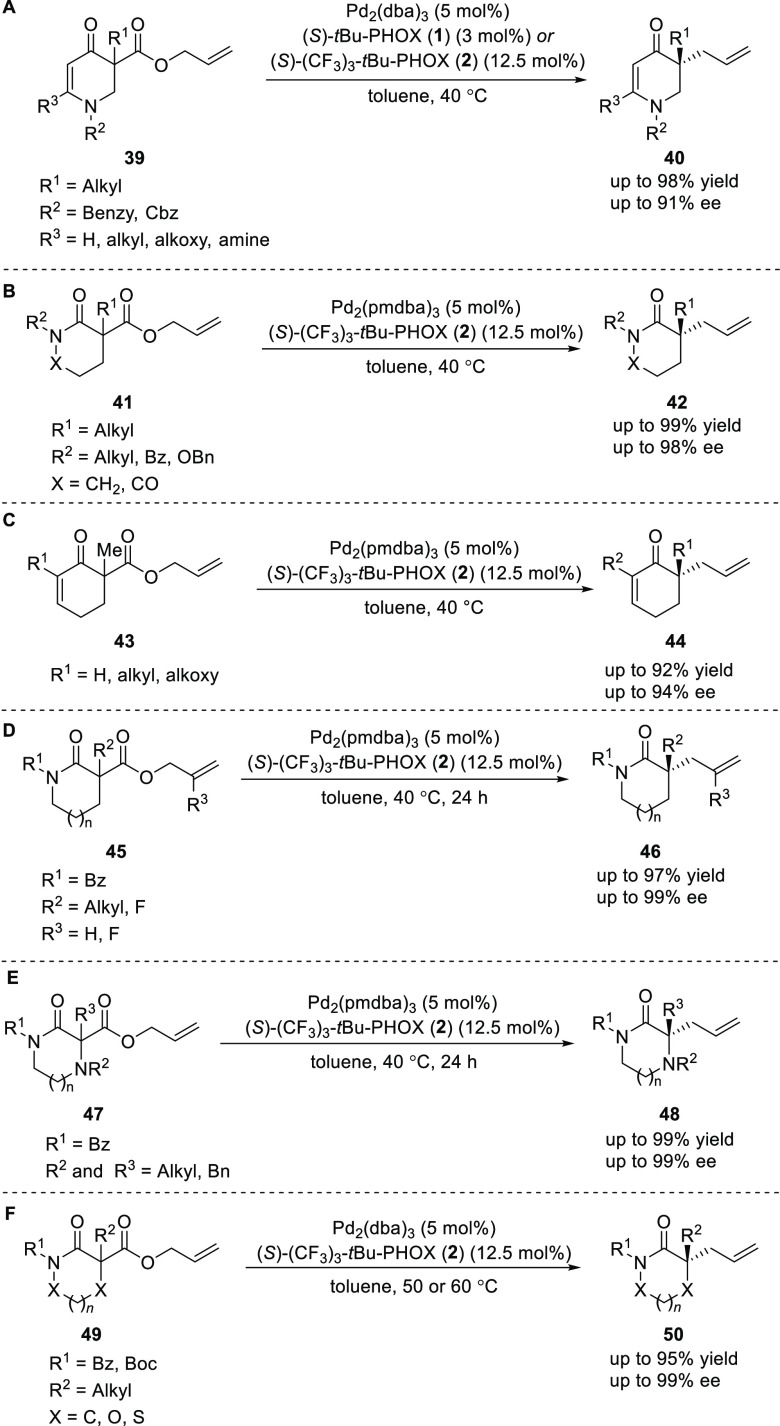

Stoltz in 2013 reported a Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative allylic alkylation of novel allyl ester substrates (39, 41, and 43) to probe the influence of enolate electronics and the role of α-functionality on the selectivity (Scheme 8A–C).17 It was observed that the high enantioselectivities obtained with imides and lactams are due to both electronic and steric effects associated with the α-substituent, and the enolate electronics alone contribute comparatively less to the stereochemical outcome of the reaction.

Scheme 8. Decarboxylative Asymmetric Allylic Alkylation.

In 2012, Stoltz reported the highly enantioselective Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative allylic alkylation of readily available lactams (45) to form 3,3-disubstituted pyrrolidinones, piperidinones, caprolactams and structurally related lactams (46) (Scheme 8D).18 This method was employed for the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of key intermediates previously used for the construction of Aspidosperma alkaloids quebrachamine and rhazinilam.

In 2015, Stoltz reported the synthesis of α-tertiary piperazin-2-ones (48) by a Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative allylic alkylation (Scheme 8E).19 This method employed a more electron-rich Pd catalyst, [Pd2(pmdba)3] and an electron-deficient PHOX ligand to afford products in good to excellent yields and enantioselectivities. Additionally, this method also allows for the synthesis of α-secondary piperazin-2-ones in modest to excellent yields and good to excellent enantioselectivities. A variety of substituents at nitrogen and also at the stereocenter were tolerated under the reaction conditions employed.

In 2015, Stoltz developed a method to synthesize α,α-disubstituted N-heterocyclic carbonyl compounds (50), by using the well-established DAAA reaction (Scheme 8F).20 Various heterocycles including morpholinone, thiomorpholinone, oxazolidin-4-one, 1,2-oxazepan-3-one, and 1,3-oxazinan-4-one performed well to furnish carbonyl products with fully a substituted stereocenter at the α-position. The presence of an electron-deficient N-substituent was required for high reactivity and enantioselectivity.

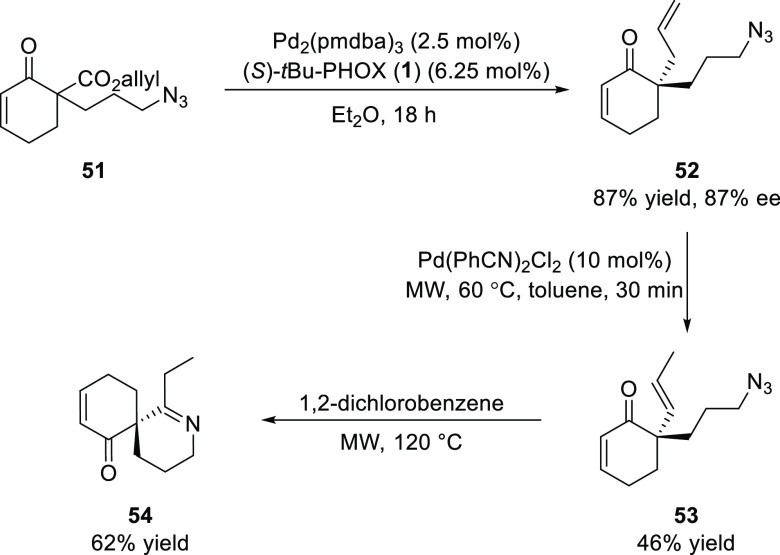

Guillou reported a method to access enantioenriched spiroimines (54) using Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative allylic alkylation (Scheme 9).21 A variety of cyclic ketones (52) having α-allyl, propyl or butyl azido groups were synthesized in moderate to good enantioselectivity which, upon isomerization of the allyl group followed by a [3 + 2]-cycloaddition of the azidoalkene, afforded a variety of chiral spiroimines.

Scheme 9. Enantioselective Synthesis of Spiroimines.

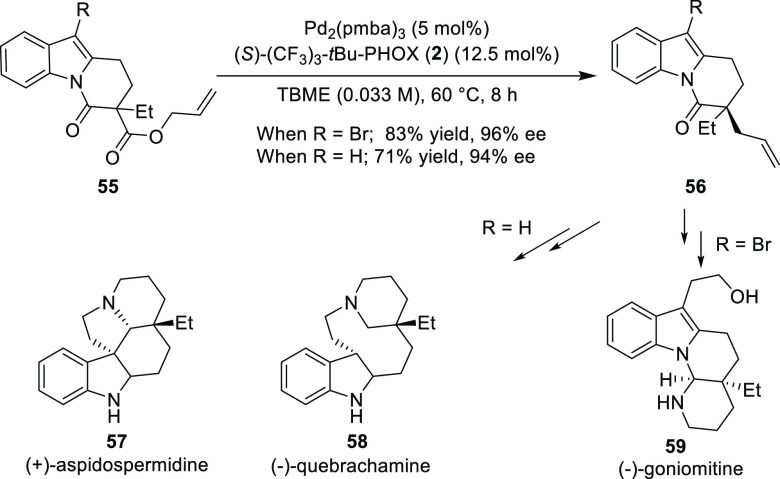

In 2016, Stoltz reported the first catalytic asymmetric total synthesis of (−)-goniomitine (59) starting from indole in 11 steps with an 8% overall yield (Scheme 10).22 The important step during this synthesis involves the Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative allylic alkylation of rationally designed heteroaryl bromide 55 furnishing product in 83% yield and 96% ee. Additionally, the formal synthesis of (+)-aspidospermidine (57) and (−)-quebrachamine (58) was also demonstrated.

Scheme 10. Catalytic Asymmetric Total Synthesis of (−)-Goniomitine, (+)-Aspidospermidine, and (−)-Quebrachamine.

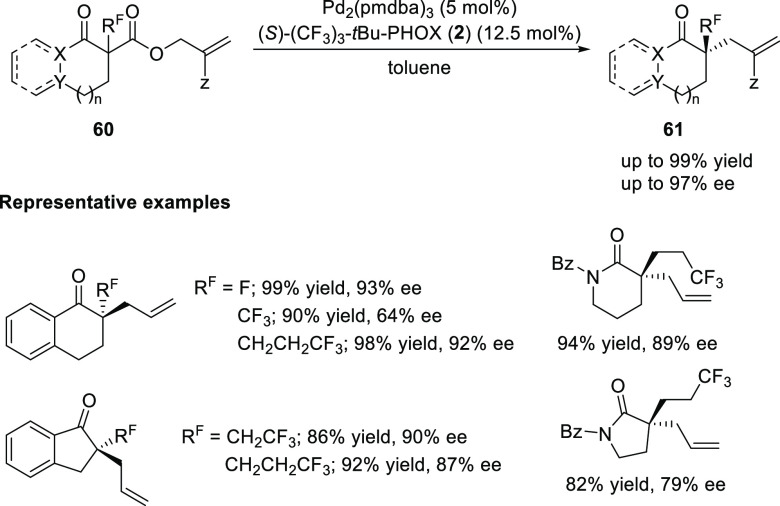

In 2018, Stoltz reported a strategy to construct fluorine-containing tetra-substituted stereocenters by the enantioselective Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative allylic alkylation of various carbonyl compounds (60) (Scheme 11).23 An electron-deficient (S)-(CF3)3-tBu-PHOX (2) ligand was optimal and this reaction showed significant substituent tolerance as a variety of five- and six-membered ketones and lactams (60) afforded the corresponding products with good yields and enantioselectivities.

Scheme 11. Enantioselective Synthesis of Fluorine-Containing Tetra-Substituted Stereocenters.

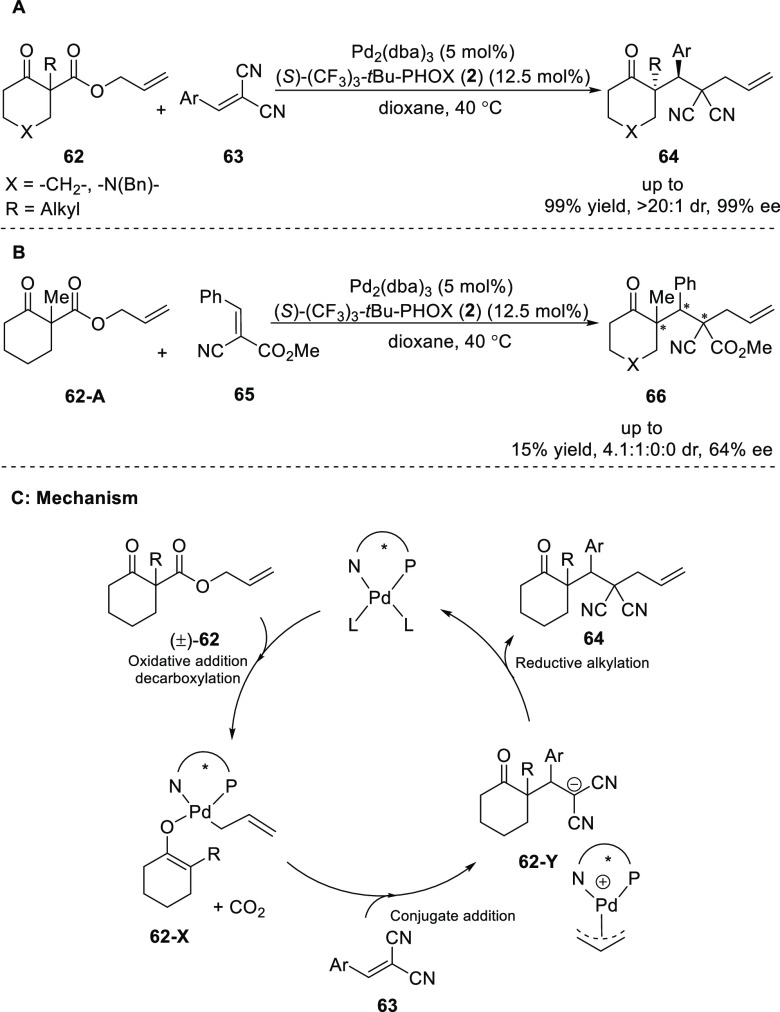

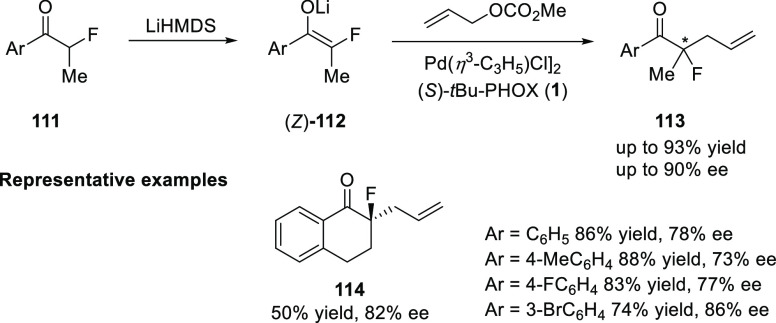

In 2010, Stoltz devised a Pd-catalyzed highly enantio- and diastereoselective α-alkylation cascade protocol (Scheme 12A).24 This method allowed for the installation of vicinal quaternary and tertiary stereocenters in a single step. Cyclohexanone based β-keto-ally esters 62 and arylidene malononitrile 63 were suitable substrates and the desired products 64 were formed in up to 99% ee and with a > 20:1 dr. Small alkyl groups (R) were tolerated best in the reaction, although the use of electron-donating substituents on the arylidene malononitrile gave rise to lower yields. The installation of three stereocenters was also attempted by employing α-nitrile esters 65 (Scheme 12B). However, using a palladium complex of the chiral ligand (CF3)3-t-Bu-PHOX (2) in the reaction gave a poor yield of 15% and 64% ee. The reaction proceeds via the decarboxylation of β-keto-allyl ester (62) to generate a Pd-enolate of cyclohexanone (62-X), followed by a conjugate addition to a prochiral activated Michael acceptor which generates densely functionalized molecules (64) that possess a quaternary stereocenter next to a tertiary center (Scheme 12C).

Scheme 12. Enantioselective Decarboxylative Enolate Alkylation Cascade.

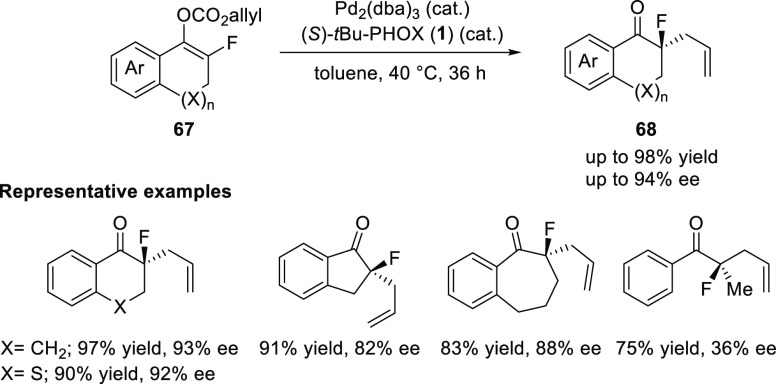

In 2008, Paquin detailed a Pd-catalyzed enantioselective decarboxylative allylic alkylation of fluorinated allyl enol carbonates (67) (Scheme 13).25 They discovered an important and unusual effect of the L/Pd ratio on the enantioselectivity, whereby a L/Pd ratio of 1:1.67 (and as low as 1:4) is required to afford the α-fluoroketones (68) in high enantioselectivity (up to 94% ee).

Scheme 13. Enantioselective Decarboxylative α-Allylation of Fluorinated Allyl Enol Carbonates.

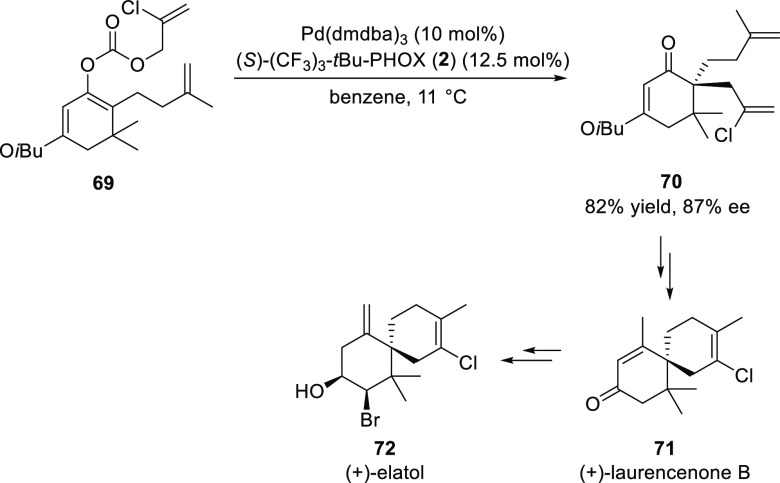

In 2008, Stoltz devised a concise enantioselective strategy for the syntheses of elatol (72) and (+)-laurencenone B (71) (Scheme 14).26 The key Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative enantioselective alkylation was employed to access sterically encumbered enantioenriched vinylogous esters.

Scheme 14. Enantioselective Synthesis of Elatol and (+)-Laurencenone B.

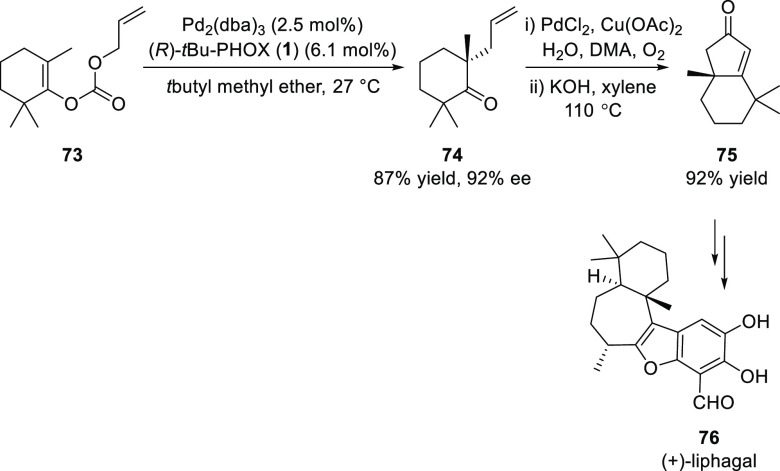

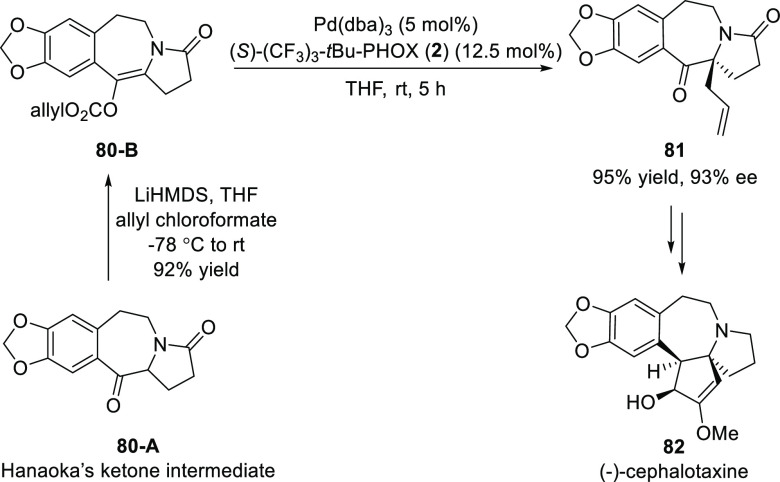

In 2011, Stoltz completed the catalytic enantioselective total synthesis of (+)-liphagal (76) in 19 overall steps from commercially available starting materials (Scheme 15).27 The key step involves a Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative allylic alkylation of enol carbonate 73 to furnish tetra-substituted ketone 74 in 87% yield and 92% ee. This intermediate was elaborated to bicycle 75 in a two-step sequence which was further used for the completion of the first total synthesis of (+)-liphagal.

Scheme 15. Catalytic Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (+)-Liphagal.

In 2011, Stoltz developed a formal synthesis of (+)-hamigeran B 79 starting from tetralone 77 using a key Pd-catalyzed enantioselective decarboxylative allylic alkylation (Scheme 16).28 The other key reaction involves a Ru-mediated cross-metathesis with methyl vinyl ketones and a CuH-mediated domino conjugate reduction-cyclization.

Scheme 16. Formal Synthesis of (+)-Hamigeran B.

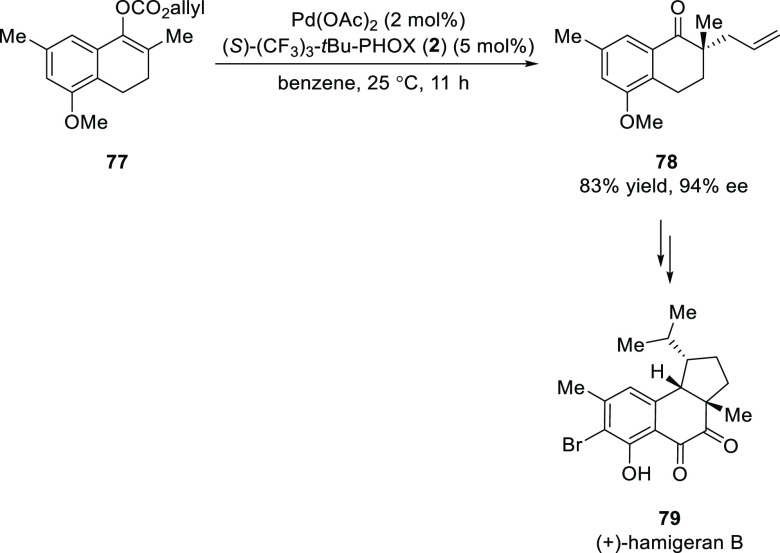

In 2018, Zhang reported a catalytic asymmetric synthesis of (−)-cephalotaxine 82 using a Pd-catalyzed Tsuji allylation (Scheme 17).29 The synthesis involved 15 steps starting from homopiperonylamine with a 6.2% overall yield. The key allyl enol carbonate precursor 80-B was prepared from the classic Hanaoka’s pyrrolobenzazepine intermediate (80-A).

Scheme 17. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of (−)-Cephalotaxine.

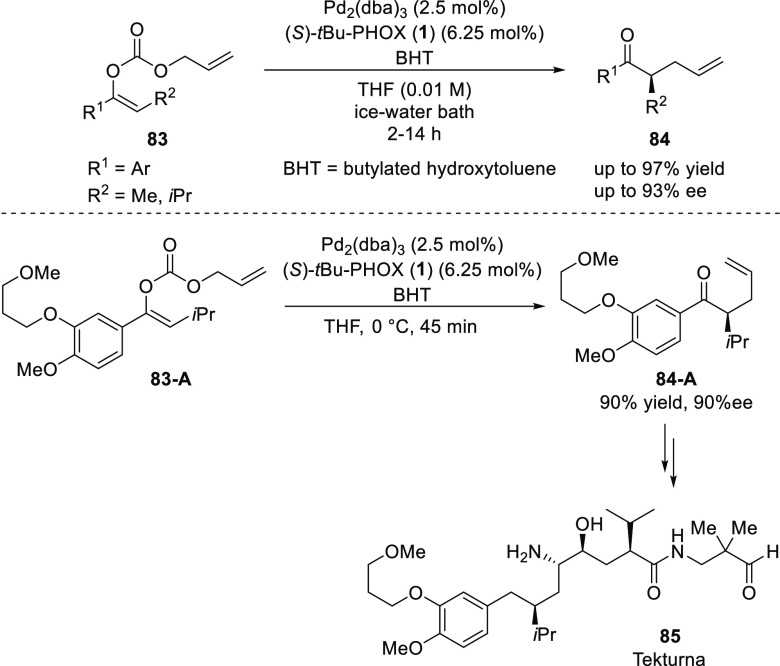

In 2012, Hanessian reported a new approach for the synthesis of tekturma (85), a drug used in the treatment of hypertension. This approach involves a modified Stoltz Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative asymmetric allylation (Scheme 18).30 A remarkable effect of BHT (2,6-di-tBu-p-cresol) as a protic additive on the reaction time and enantioselectivity was discovered. The alkyl aryl enol carbonate (83-A) was converted into intermediate, (R)-α-isopropyl allyl aryl ketone (84-A) in 90% yield and 90% ee which was used for the synthesis of tekturna 85.

Scheme 18. Application of DAAA for Synthesis of Tekturma.

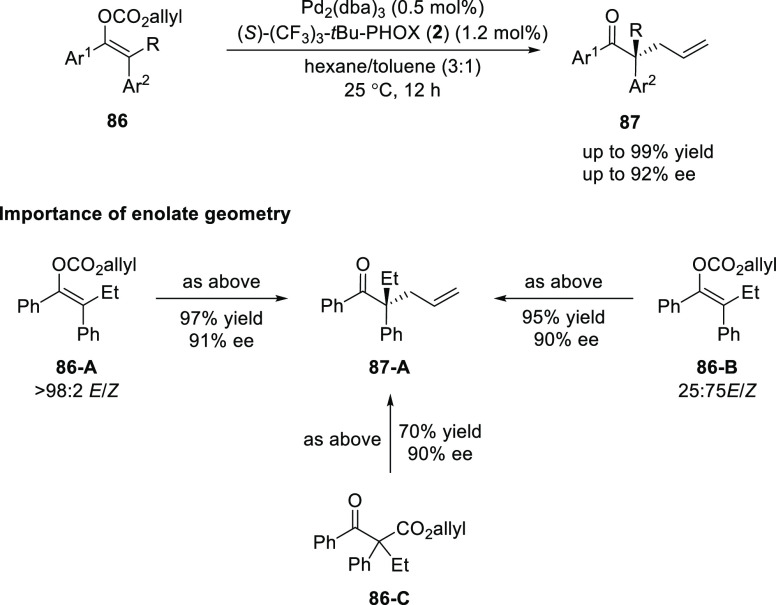

In 2018, Stoltz reported the first enantioselective Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative allylic alkylation of fully substituted acyclic enol carbonates (86) providing linear α-quaternary ketones (87) (Scheme 19).31 High yields and enantiomeric excesses of the product were achieved using the electron-deficient ligand, (S)-(CF3)3-tBu-PHOX (2). Previous reports in Pd-catalyzed allylic alkylation suggested differing selectivities with different enolate geometries but here it was found that the enolate geometry of the starting material has no adverse effect as the same enantiomer of the product was obtained with the same level of selectivity regardless of the starting ratio of enolates. It was postulated that a dynamic kinetic resolution of the two enolate geometries occurs in the reaction possibly due to facile equilibration between O-bound and C-bound Pd enolates in the presence of the electron-deficient PHOX ligand.

Scheme 19. DAAA of Fully Substituted Acyclic Enol Carbonates.

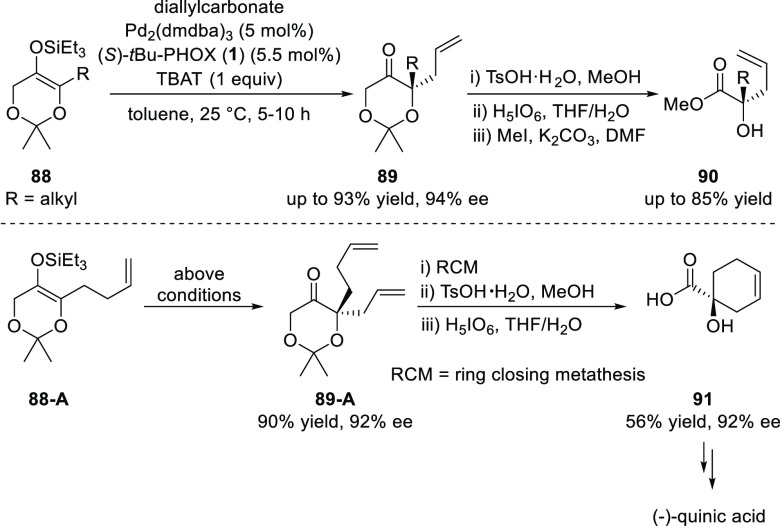

In 2008, Stoltz developed a Pd/(S)-tBu-PHOX-catalyzed asymmetric alkylation of simple dioxanone derivatives (88) to obtain enantioenriched tetra-substituted dioxanone 89 possessing allyl group at α-position (Scheme 20).32 The enantioenriched tetra-substituted dioxanone subsequently was transformed into the enantioenriched α-hydroxyketones, acids, and esters via a three-step sequence which involved acetonide cleavage catalyzed by p-toluenesulfonic acid (TsOH·H2O), oxidative cleavage with periodic acid (HIO4) and finally methylation of the acid moiety. Additionally, this procedure allowed a catalytic enantioselective formal synthesis of (−)-quinic acid, a useful chiral building block.

Scheme 20. DAAA of Dioxanone Derivatives.

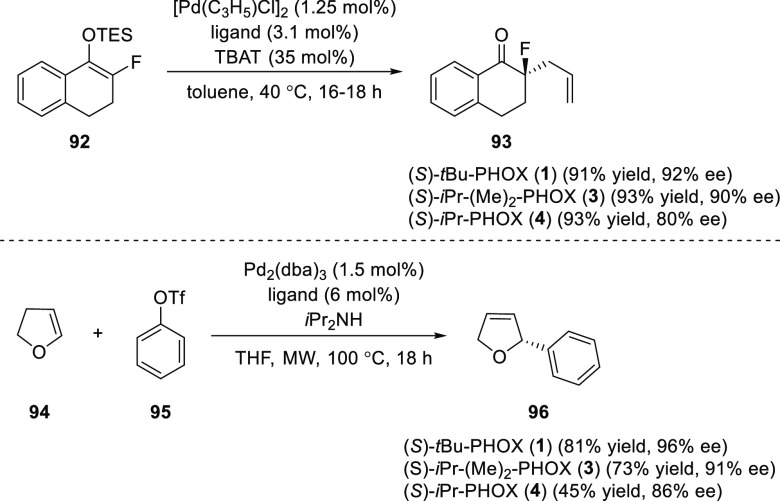

Paquin reported a new member of the PHOX family, 5,5-(dimethyl)-iPr-PHOX (3), having parallel reactivity to (S)-(CF3)3-tBu-PHOX (2) with the key advantage of being easily accessible as both enantiomers (Scheme 21).33 The application of ligand was carried out in the enantioselective allylation of fluorinated silyl enol ether (92) and the enantioselective Heck reaction between 2,3-dihydrofuran (94) and phenyl triflate (95). It was observed that the new ligand’s reactivity was as good as (S)-tBu-PHOX (1) and better than the (S)-iPr-PHOX (4), which lacks the gem-dimethyl at C-5, thus demonstrating the beneficial effect of the substituents at C-5.

Scheme 21. Enantioselective Allylation of Fluorinated Silyl Enol Ether and Heck Reaction.

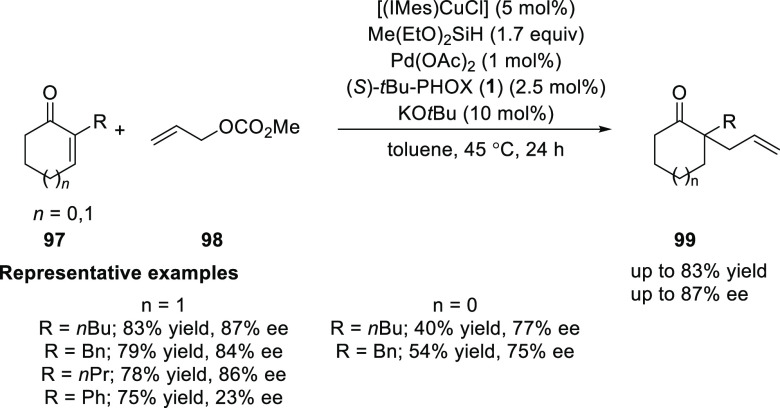

Riant reported a cooperative dual catalysis based on a Pd(0)/Cu(I) system to generate quaternary carbon stereocenters (Scheme 22).34 In this domino process, the first reaction involves a 1,4 reduction of cyclic enones using Cu(I) hydride to generate the Cu enolate species in situ which further reacts with the π-allyl-Pd complex to form the desired allylation product in an asymmetric fashion. The role of KOtBu as an additive was crucial to increase the enantioselectivity. This method showed tolerance toward alkyl and benzyl groups at the α-position of enones furnishing products in comparable yields and enantioselectivities. The presence of the phenyl group at the α-position of enones was also tolerated to give the expected products in good yield, but unfortunately with low levels of enantioselectivity.

Scheme 22. Asymmetric Cooperative Dual Catalysis of α-Substituted Cyclic Enones.

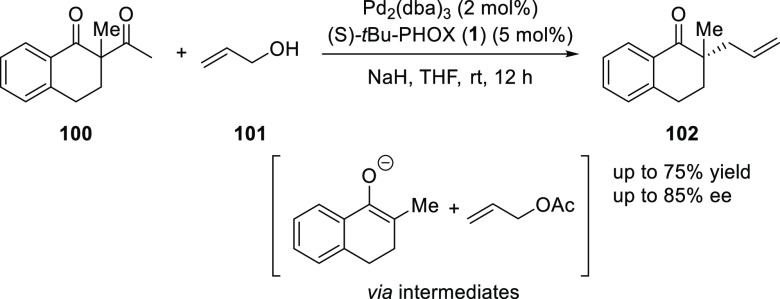

Tunge reported a method for the asymmetric allylic alkylation of α-tetralones via deacylative allylation using Pd(0) and (S)-tBu-PHOX (1) ligand (Scheme 23).35 This method uses a readily available cyclic ketone pro-nucleophile (100) and allylic alcohol (101) as the allyl source. The reaction involves a retro-Claisen cleavage which results in the formation of both reactive intermediates, the active nucleophile (alkoxide) and electrophile (π-allyl). It was observed that the starting acetyl tetralone (100) must be used in slight excess (1.05 equiv) compared to the alkoxide as it had a detrimental effect on ee. The possible explanation for this is that excess alkoxide competes with the enolate for coordination to Pd which interferes with the inner sphere mechanism for allylation as reported by Stoltz.36

Scheme 23. Asymmetric Deacylative Allylation.

After Tunge’s initial report, Aponick extended this intermolecular Tsuji allylation to enol acetates (Scheme 24).37 The enol acetate substrate (103) is advantageous over the Tunge type 1,3-diketones as they can be easily prepared. This intramolecular allylation version facilitates rapid diversification of the α-quaternary stereocenter-containing products. The method tolerates a wide range of functional groups on the allylic part and the enol acetate of both aromatic and aliphatic ketones. The reaction proceeds with enantioselectivity up to 96% ee and the selectivity has a strong dependence on concentration in intermolecular acyl-transfer reactions as the lower concentrations gives products with higher enantioselectivity. The present protocol is better for 2-substituted allyl alcohols compared to simple allyl alcohol substrates.

Scheme 24. Intermolecular Tsuji Allylation of Enol Acetates.

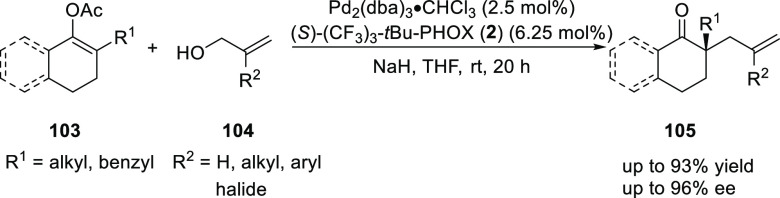

Stoltz disclosed an elegant approach toward the synthesis of the polycyclic norditerpenoid ineleganolide (Scheme 25).38 A key Pd/(S)-tBu-PHOX (1)-catalyzed enantioselective allylic alkylation was employed to synthesize ketone 108, bearing a chloro-substituted allyl moiety and a methyl group at the α-position, in 82% yield and 92% ee. Ketone 108 underwent a series of diastereoselective transformations to provide a 1,3-cis-cyclopentenediol 109 in 91% yield over five steps. This diol served as a building block for the synthesis of ineleganolide (110).

Scheme 25. Synthesis of Polycyclic Norditerpenoid Ineleganolide.

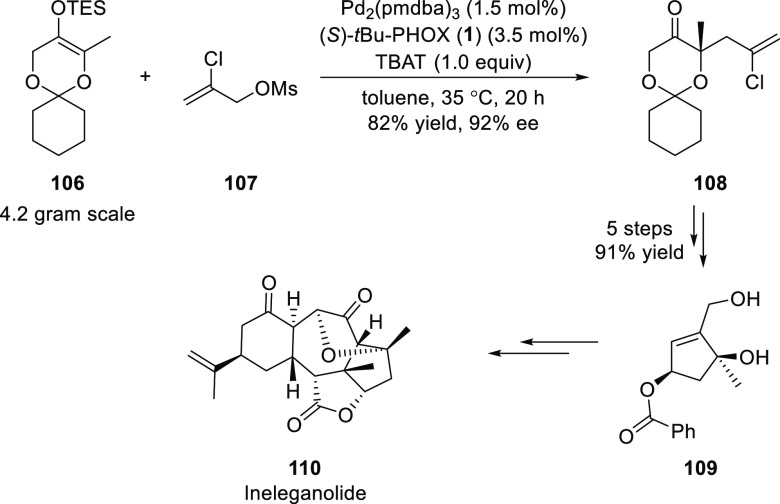

In 2014, Guo and Chen reported a method for the asymmetric synthesis of acyclic α-carbonyl tertiary alkyl fluorides (113) using an enantioselective Tsuji-Trost reaction of racemic acyclic α-fluorinated ketones (111) (Scheme 26).39 The enantioselectivity for the acyclic α-fluoro ketones (113) products formed ranged from 60 to 90% ee. The good (Z)-configuration of in situ generated enolate intermediate and the presence of a fluorine atom in the starting material had a positive effect on the enantioselectivity observed. It is well documented that cyclic ketones give a better level of enantioselectivity compared to acyclic ketones due to the low selectivity of acyclic ketones toward the formation of an E/Z mixture of the Pd enolate in situ.

Scheme 26. Asymmetric Synthesis of Acyclic α-Carbonyl Tertiary Alkyl Fluorides.

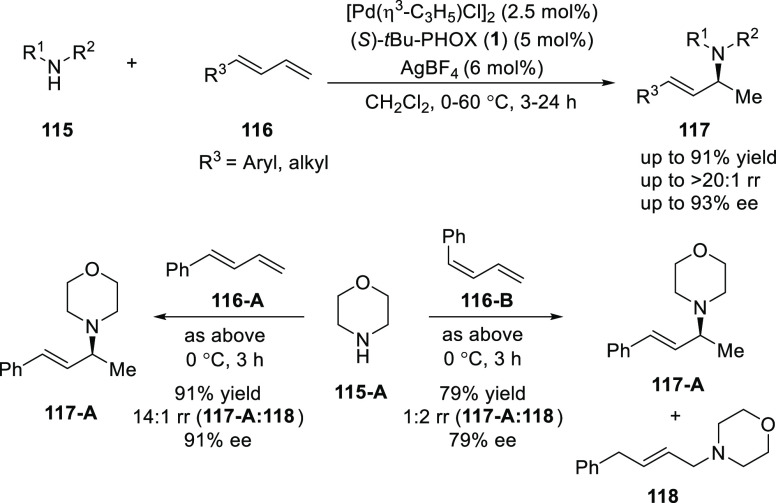

Malcolmson developed a Pd/tBu-PHOX (1)-catalyzed enantioselective intermolecular addition of aliphatic amines (115) with acyclic 1,3-dienes (116) (Scheme 27).40 The chiral allylic amines (117) were synthesized in up to 93% ee. The electron-deficient phosphine ligand not only leads to a more active catalyst but also was important to achieve high levels of enantioselectivity. Mechanistic details revealed that the diene stereochemistry has a strong effect on site selectivity as (Z)-phenylbutadiene (116-B) under optimal conditions furnished a dramatically higher proportion of the 1,4-hydroamination product (118) instead of an expected 1,2-hydroamination product (117-A) (1:2 ratio) compared to the reaction of the (E)-isomer (116-A) which also proceeded with reduced enantioselectivity. It was also noted that both hydroamination products are formed exclusively as the (E)-isomer, indicating that olefin isomerization is faster than amine attack. Additionally, 1,2-hydroamination (117-A) formed the same enantiomer from either the (E)- or (Z)-isomer of the starting 1,3-butadiene. This catalytic system is highly efficient for promoting regio-and enantioselective additions of amines to terminal 1,3-dienes, although internal dienes fail to react.

Scheme 27. Enantioselective Hydroamination of Acyclic 1,3-Dienes.

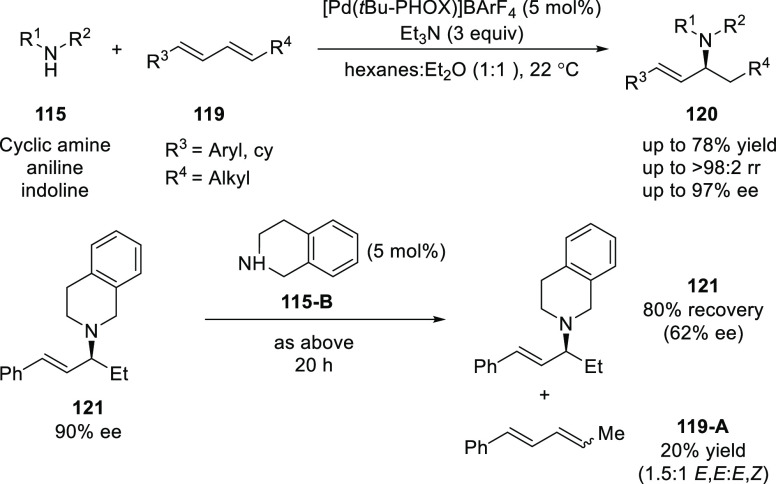

After a year, Malcolmson extended their enantioselective hydroamination strategy to the challenging 1,4-disubstituted acyclic 1,3-dienes (119) (Scheme 28).41 The success of this method was largely due to a Pd-PHOX catalyst with a noncoordinating BArF4 counteranion, triethylamine as an additive and a nonpolar reaction medium. The variety of aryl/alkyl-disubstituted dienes (119) reacted with several aliphatic amines, primary anilines and indoline to generate allylic amines (120) possessing different α-alkyl groups in good yields and selectivities (up to 78% yield, >98:2 rr, 97% ee). Interestingly, secondary amines, such as piperidine and pyrrolidine, were unreactive under the optimal reaction conditions despite having greater nucleophilicity, perhaps due to the higher pKa values of their conjugate acids compared to the more electron-deficient morpholine, piperazines, and tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) which reacts remarkably well in this reaction. Mechanistic details indicated that the hydroamination is reversible as the ee of the product was found to diminish over time.

Scheme 28. Enantioselective Hydroamination of 1,4-Disubstituted Acyclic 1,3-Dienes.

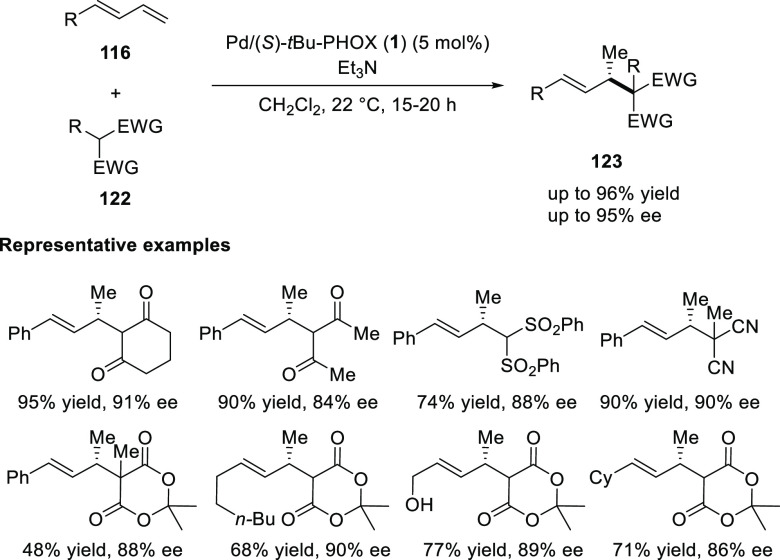

Malcolmson employed a catalytic system of Pd-PHOX for the enantioselective intermolecular hydroalkylation of acyclic 1,3-dienes with Meldrum’s acid derivatives and other activated carbon pro-nucleophiles (Scheme 29).42 A variety of aryl- and alkyl-substituted dienes (116) react with different β-dicarbonyl-like nucleophiles (122) to generate allylic stereogenic centers at the carbonyl’s β-position in up to 96% yield and 95% ee. Similar to hydroamination (Scheme 28), here the use of triethylamine is essential as it acts as a base which upon deprotonation of carbonyl nucleophile would generate the corresponding ammonium enolate and also its protonated source, might potentially act as an acid source for Pd–H formation within the catalytic cycle. Additionally, it is important to note that the reaction is highly site-selective as addition occurs across the diene’s terminal olefin.

Scheme 29. Enantioselective Hydroalkylation of Acyclic 1,3-Diene.

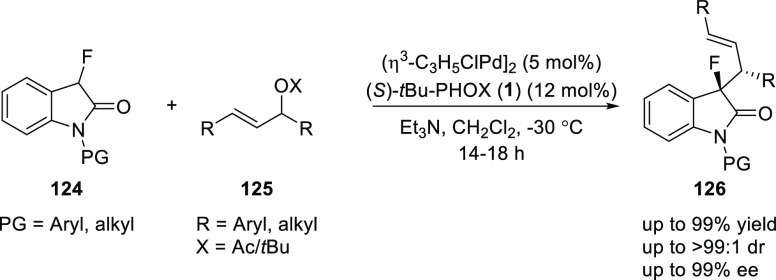

Wolf presented a regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselective allylation of 3-fluorinated oxindoles (124) using catalytic amounts of Pd and (S)-tBu-PHOX (1) (Scheme 30).43 This method offers a synthesis of 3,3-disubstituted fluorooxindole alkaloids (126) possessing vicinal chiral centers. This protocol was effective with allylic acetates which carried only one aryl terminus and C–C bond formation occurs at less hindered sites irrespective of the origin of the acetyl group.

Scheme 30. Enantioselective Allylation of 3-Fluorinated Oxindoles.

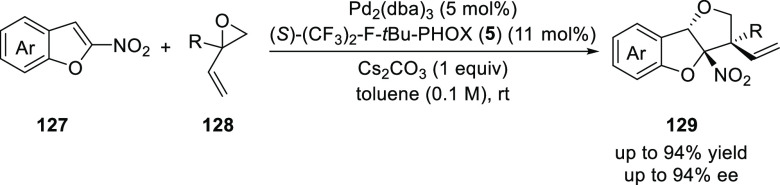

You reported a stereoselective synthesis of tetrahydrofuro-benzofurans (129) and tetrahydrofurobenzothiophenes by the dearomatization of nitrobenzofurans (127) and nitrobenzo-thiophenes, respectively using a Pd/tBu-PHOX (1)-catalyzed formal [3 + 2] cycloaddition (Scheme 31).44 The electronic and steric factors on the phosphine of the PHOX ligand were crucial for the success of this reaction. The products with vicinal stereogenic carbon centers were obtained in good to excellent diastereoselectivity (13/1 to >20/1 dr), and enantioselectivity (75–94% ee).

Scheme 31. Enantioselective [3 + 2] Cycloaddition with 2-Nitrobenzofurans.

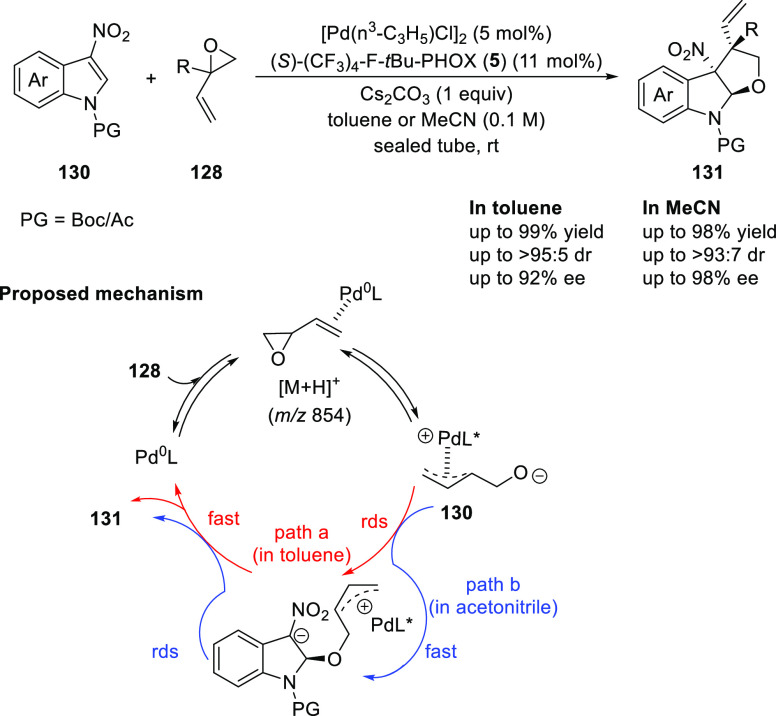

You also extended this methodology to the 3-nitroindole substrates (130) (Scheme 32). A stereodivergent synthesis of tetrahydrofuroindoles (131) is reported through a diastereoselective and enantioselective dearomative formal [3 + 2] cycloaddition by using catalytic Pd and PHOX ligand.45 The polarity of the solvent was key to obtain high levels of diastereoselectivity. The use of toluene furnished tetrahydrofuroindole products in good to excellent yields (70–99%), diastereoselectivity (87:13 → 95:5 dr), and enantioselectivity (70–88% ee) whereas acetonitrile yielded another diastereomer in good to excellent yields (75–98%) and stereoselectivity (78:22–93:7 dr and 86–98% ee). Mechanistic studies suggested that the origin of the diastereodivergency was due to the different rate-limiting steps in different solvents, thereby leading to a reversal of stereocontrol.

Scheme 32. Enantioselective [3 + 2] Cycloaddition with 3-Nitroindoles.

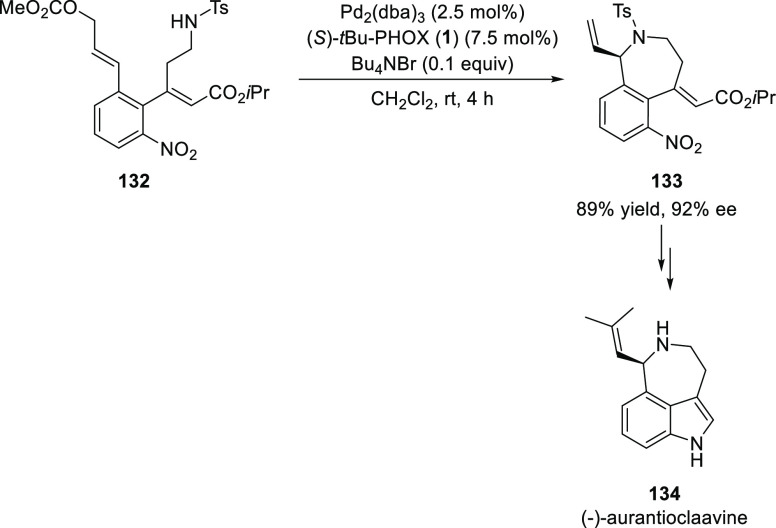

In 2014, Takemoto achieved a catalytic enantioselective total synthesis of (−)-aurantioclavine (134) in 16 steps starting from 3-nitro-2-iodophenol (Scheme 33).46 The key step involves intramolecular asymmetric amination of allylic carbonate (132), which has a TsNHR group, using Pd and (S)-tBu-PHOX (1) which proceeded smoothly to furnish a seven-membered heterocycle (133) in 89% yield and 92% ee. This asymmetric allylic amination reaction is a powerful tool to construct a chiral azepinoindole skeleton.

Scheme 33. Catalytic Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (−)-Aurantioclavine.

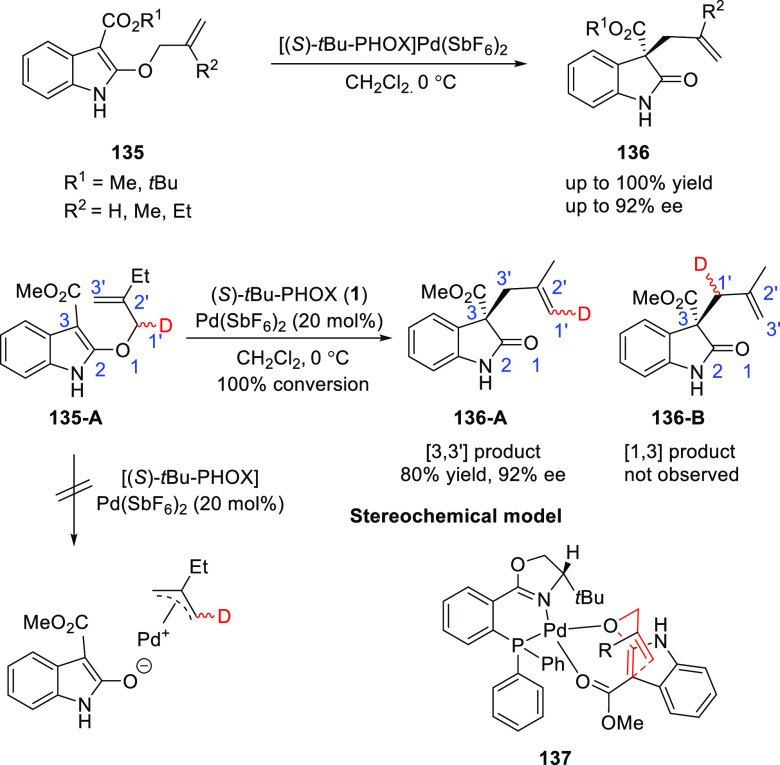

Kozlowski established a first catalytic, enantioselective Meerwein–Eschenmoser Claisen rearrangement using Pd/t-Bu-PHOX (1) complex (Scheme 34).47 This method allowed the synthesis of a range of oxindoles (136) bearing a quaternary stereocenter. The counterion on Pd(II) was crucial in line with catalyst coordination to the β-amidoester substrate (135), the SbF6 and BF4 complexes provided faster rates and greater turnover than the corresponding perchlorates, triflates, and halides. The Pd/tBu-PHOX (1) combination provided the best enantioselectivity with the smaller C3 methyl ester (R1) and the larger C2′ groups (R2). Deuterium labeling experiments suggested a Lewis acid-catalyzed mechanism and excluded the possibility of π-allyl cation chemistry. In the proposed stereochemical model (137), substrate β-amidoester (135) shows two-point coordination from both oxygens to the chiral Pd complex.

Scheme 34. Enantioselective Meerwein–Eschenmoser Claisen Rearrangement.

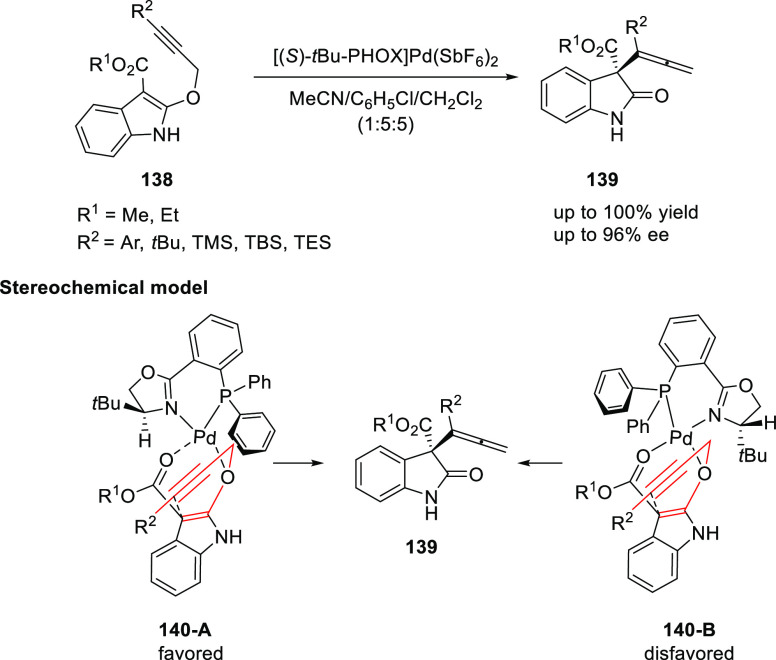

Kozlowski presented the first Pd/tBu-PHOX (1)-catalyzed, enantioselective Saucy–Marbet Claisen rearrangement to generate enantiopure allenyl oxindoles (139) bearing a quaternary stereocenter at C3 from propargyl-substituted indole derivatives (138) (Scheme 35).48 Alkyne substrates possessing ortho-substituted aryl groups at R2 gave high levels of enantioselectivity and rapid conversion (up to 96% ee). However, alkynes with larger groups like trimethylsilyl (TMS), tert-butyl, or N-methyliminodiacetic acid (MIDA) boronate were less successful. The alkyne geometry significantly alters the topology of the rearrangement transition state. Additionally, the ester functionality interacts with larger alkyne terminal substituents and destabilizes the less-favorable reaction pathway. Furthermore, improved results were achieved with nonaryl alkynes using Binap and its congeners.

Scheme 35. Enantioselective Saucy–Marbet Claisen Rearrangement.

2.1.1.2. Application of PHOX in Decarboxylative Asymmetric Protonation (DAP)

PHOX ligands have also been extensively employed in the Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative asymmetric protonation (DAP) to generate products with a tertiary stereocenter adjacent to a carbonyl group.49

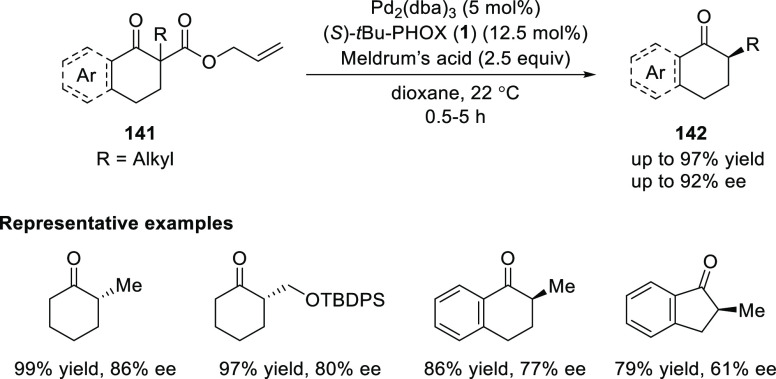

Stoltz reported a Pd/tBu-PHOX (1)-catalyzed DAP of racemic α-aryl-β-ketoallyl esters (141) (Scheme 36).50 The reaction generated α-alkylated cyclic ketones (142) in excellent yields and enantioselectivities (up to 97% yield and 92% ee) with Meldrum’s acid as the proton source.

Scheme 36. Enantioselective Decarboxylative Protonation of α-Aryl-β-ketoallyl Esters.

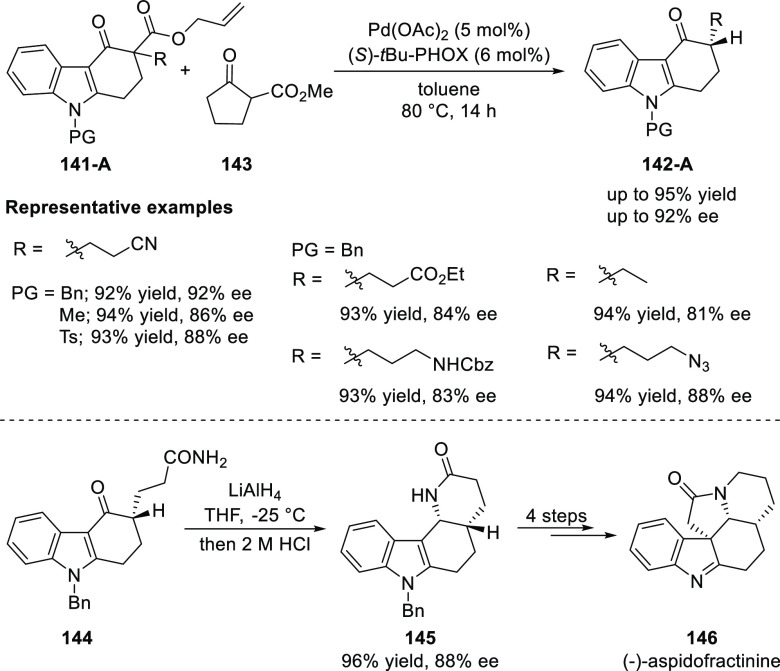

In 2014, Shao reported an enantioselective synthesis of C3-substituted chiral carbazolones (142-A) by using Pd/PHOX-catalyzed decarboxylative protonation of α-alkyl-β-keto allyl esters (141-A) (Scheme 37).51 The use of methyl 2-cyclopentanonecarboxylate (143) as the proton donor was found to be more effective compared to the normally used Meldrum’s acid. A range of C3-monosubstituted chiral carbazolones (142-A) carrying various valuable functionalities such as, nitrile, ester, amine and azide were accessed in excellent yields (up to 95%) with good enantioselectivities (up to 92% ee). The application of this methodology was demonstrated in the synthesis of a key pentacyclic intermediate of the naturally occurring (−)-aspidofractinine (146).

Scheme 37. Enantioselective Synthesis of C3-Substituted Chiral Carbazolones.

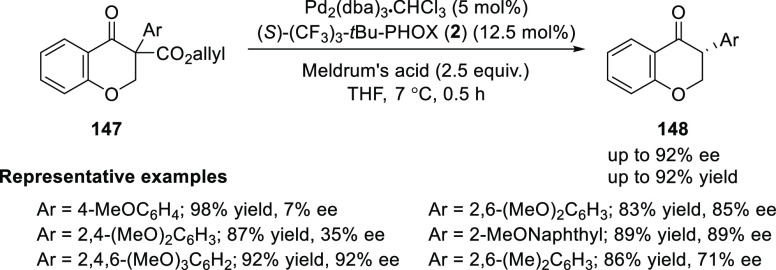

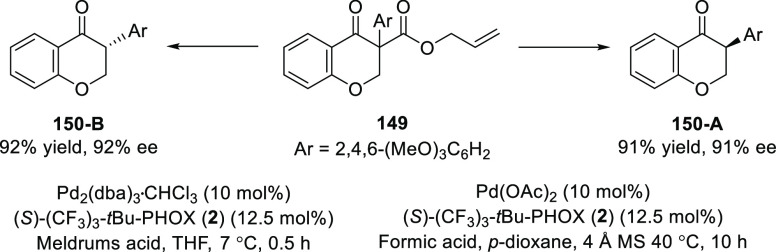

Guiry reported the first catalytic asymmetric synthesis of isoflavanones (148) containing an α-aryl substituent by using enantioselective decarboxylative protonation of α-aryl-β-ketoallyl ester (147) using Meldrum’s acid as the proton source (Scheme 38).52 It was observed that this method is influenced by both the sterics and the electronics on the α-aryl ring of the isoflavanone. The substrate containing coordinating methoxy substituents at both ortho-positions seems to be essential to achieve optimal enantioselectivity. This method allowed them to synthesize highly sterically hindered α-aryl ketones with enantioselectivities of up to 92%.

Scheme 38. Asymmetric Synthesis of Isoflavanones.

In their following report, Guiry developed a Pd-catalyzed decarboxylative asymmetric protonation of α-aryl-β-ketoallyl esters (149) to generate a tertiary α-aryl isoflavanones (150-A) using formic acid as a proton source (Scheme 39).53 It is interesting to note that, a switch in the preferred enantiomer formed was observed with formic acid as the proton source compared to their earlier work using Meldrum’s acid as the proton source. It is one of the rare examples of an asymmetric protonation wherein dual stereocontrol was observed with the same chiral ligand but with a different achiral proton donor. The Pd-enolate formed after decarboxylation of α-aryl-β-ketoallyl esters (149) was protonated by Meldrum’s acid. Remarkably, the rates of the reactions are significantly different as the Meldrum acid-mediated reaction completes in 30 min, whereas the formic acid reaction takes up to 10 h which suggests the necessity for a carbopalladation to occur and subsequent quenching by formic acid. Alternatively, some precoordination of formic acid to the chiral Pd–enolate complex may result in an inner-sphere-type protonation to a different face of the enolate than with Meldrum’s acid.

Scheme 39. Synthesis of Tertiary α-Aryl Isoflavanones.

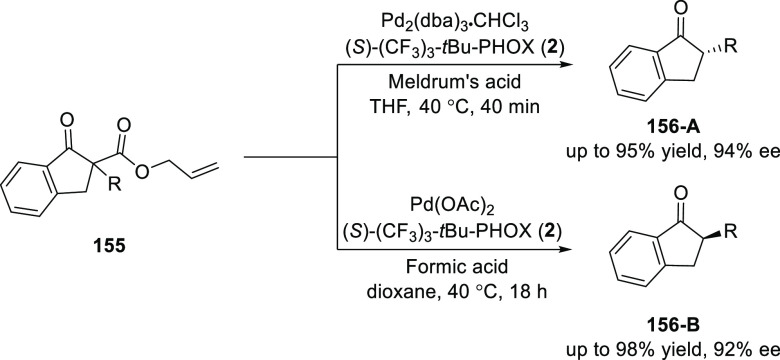

In the same year, Guiry extended the methodology for the synthesis of a series of tertiary α-aryl cyclopentanones (152) and cyclohexanones (154) from α-aryl-β-keto allyl esters (151 and 153) in moderate to good levels of enantioselectivity (Scheme 40).54 Similar to earlier methods, good levels of enantioselectivity were achieved for substrates containing aryl groups with mono- and di-ortho-substitution.

Scheme 40. Asymmetric Synthesis of Tertiary α-Aryl Cyclopentanones and Cyclohexanones.

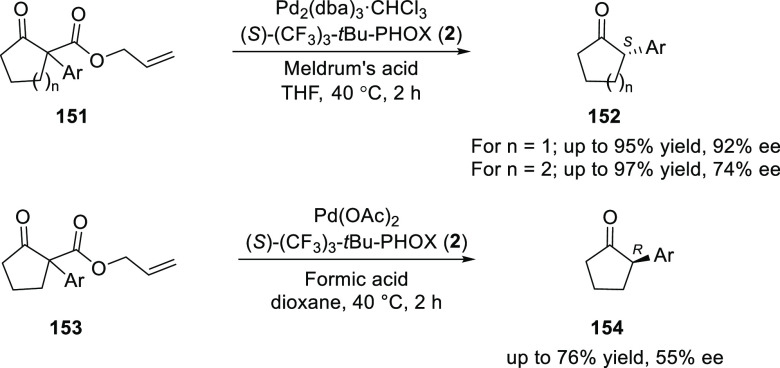

Guiry further studied a scope of the decarboxylative asymmetric protonation with indanone based α-aryl-β-keto allyl ester substrates (155) (Scheme 41).55 As seen with other cyclic ketones, both enantiomers of a series of tertiary α-aryl-1-indanones (156) were accessible by simply switching the achiral proton source. In this example of dual stereocontrol, enantioselectivities up to 92% ee (R) and 94% ee (S) were achieved using formic acid and Meldrum’s acid, respectively.

Scheme 41. Synthesis of Tertiary α-Aryl-1-indanones.

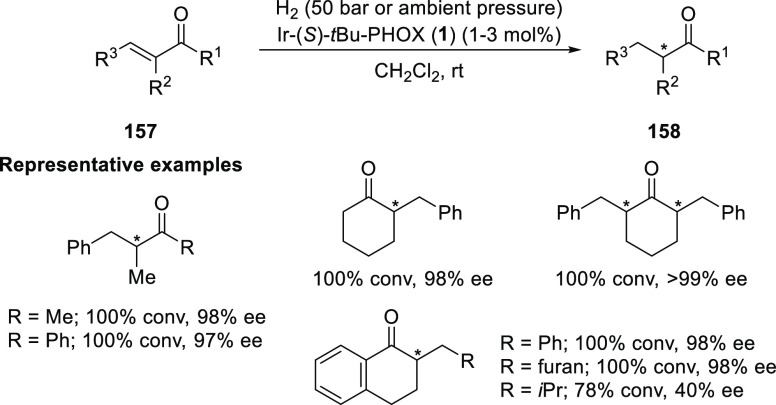

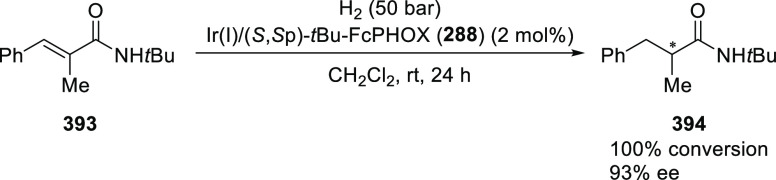

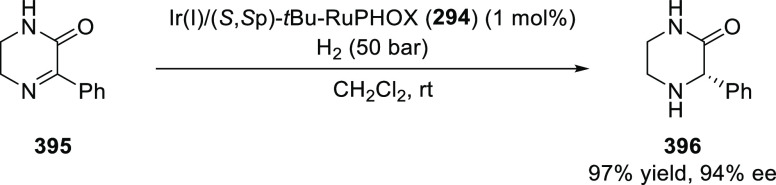

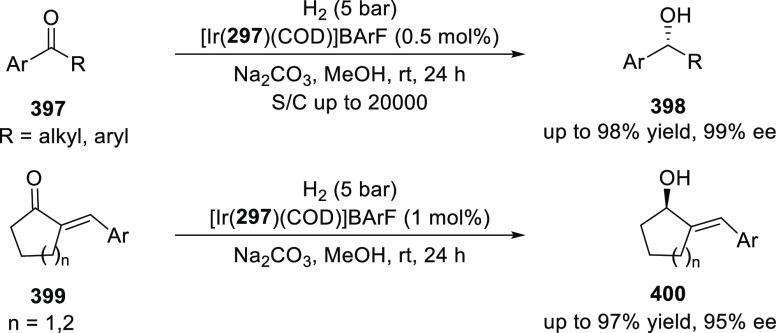

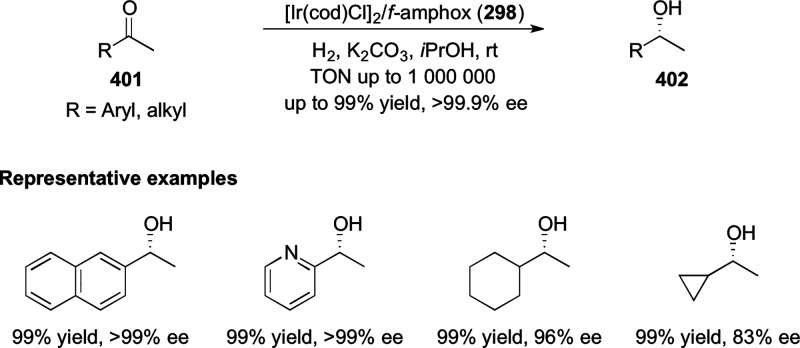

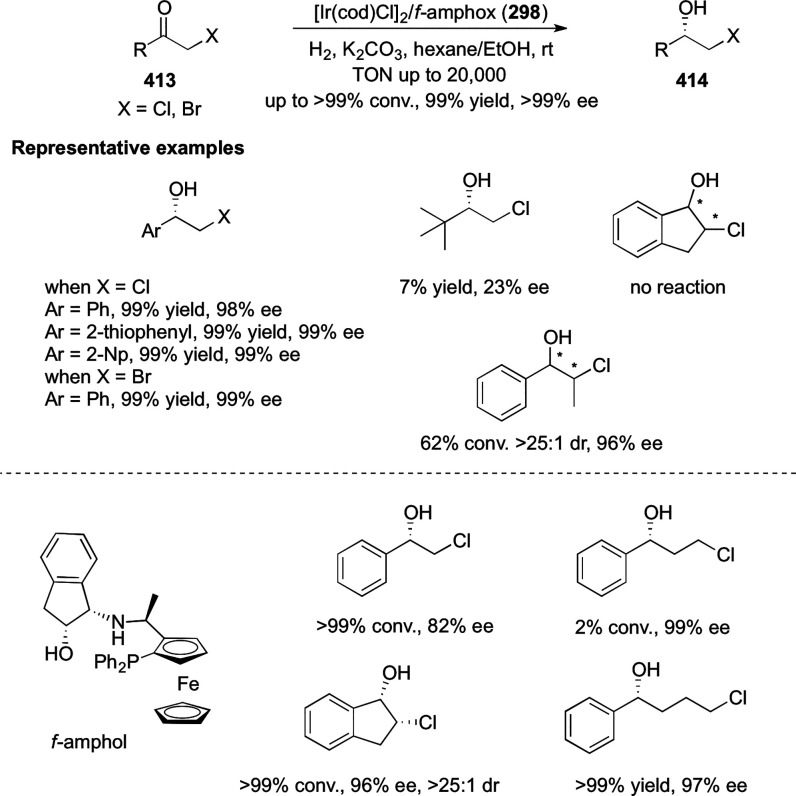

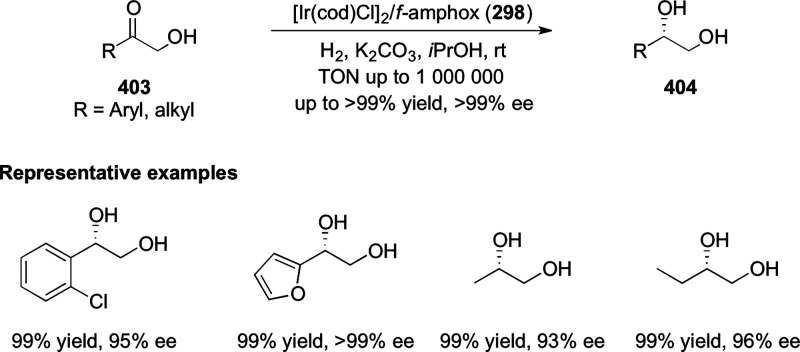

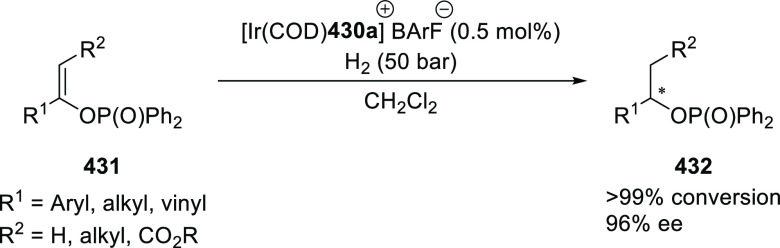

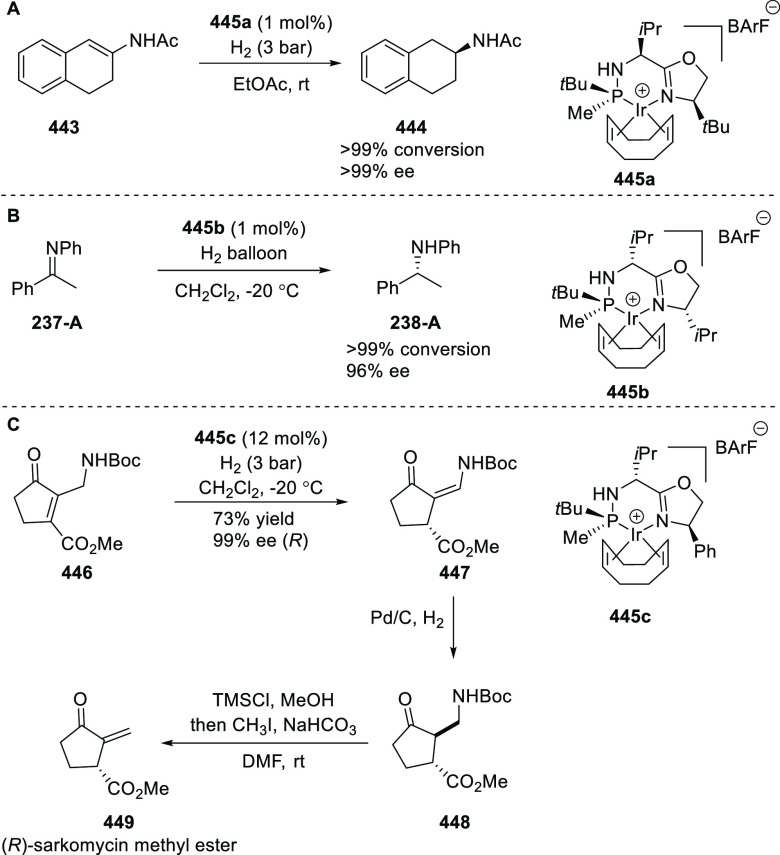

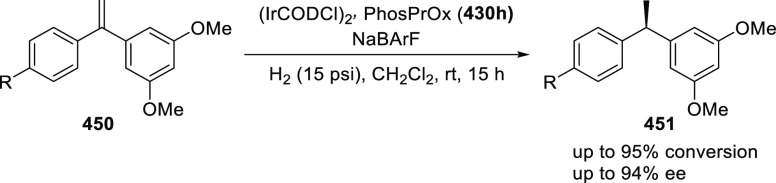

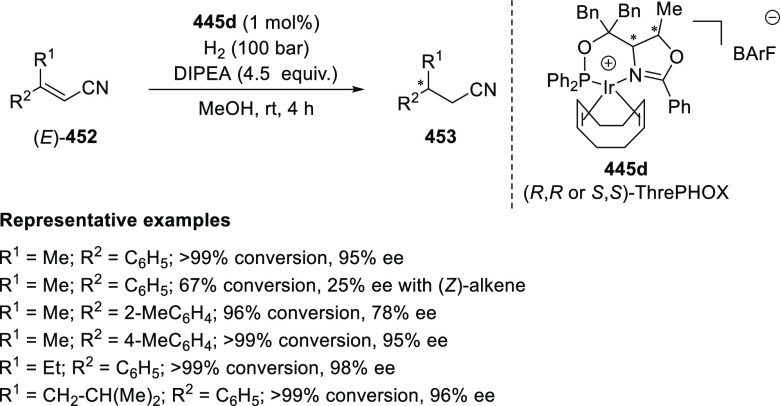

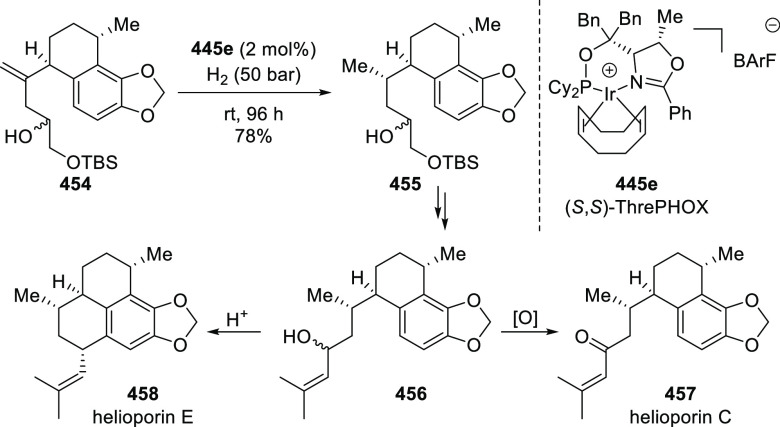

2.1.1.3. Application of PHOX in Asymmetric Hydrogenation

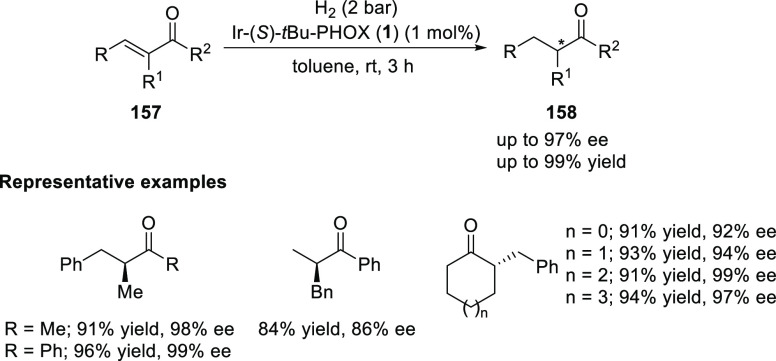

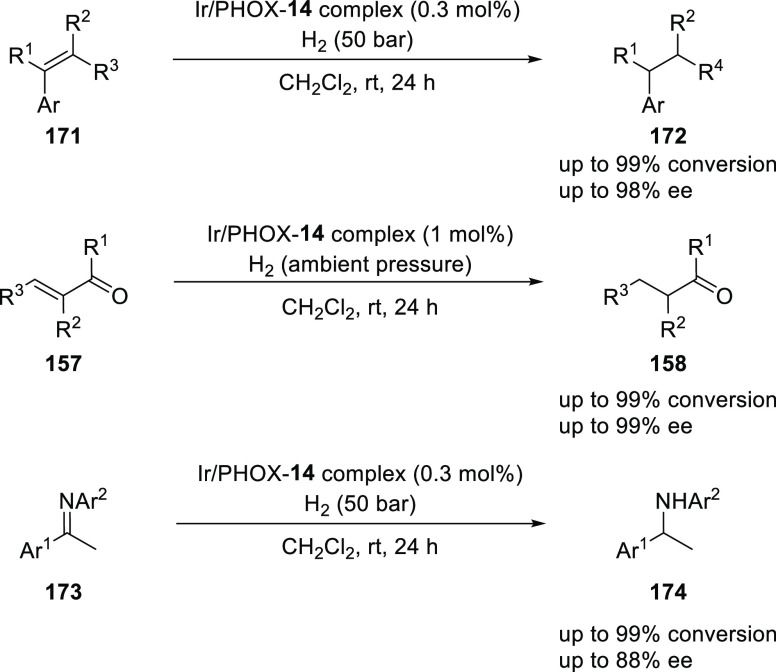

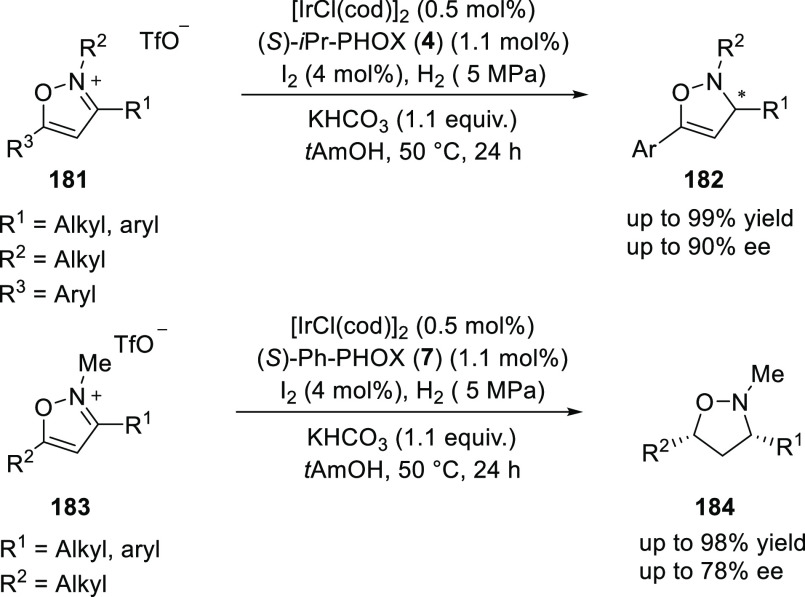

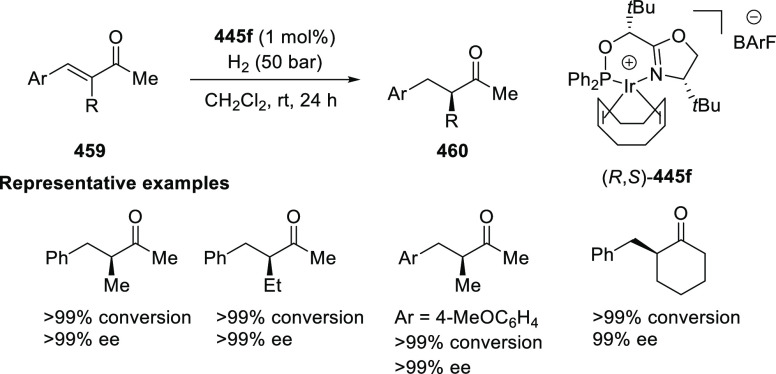

Bolm and Hou independently reported the asymmetric hydrogenation of α-substituted enones (Schemes 42 and 43).

Scheme 42. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of α-Substituted Enones.

Scheme 43. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of α-Substituted Enones.

Bolm discovered a simple and highly efficient asymmetric synthesis of α-substituted ketones (158) from α-substituted enones (157) (Scheme 42).56 Both acyclic and cyclic enones underwent smooth catalytic enantioselective hydrogenations using the Ir complex of tBu-PHOX (1) furnishing α-substituted ketones in high yields and enantioselectivities while tolerating a wide variety of substituents.

Hou reported an Ir-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of α-substituted-α,β-unsaturated ketones (157) to generate a chiral center at the α-position of ketones (158) (Scheme 43).57 Different ketone substrates possessing exocyclic alkenes furnished products in high enantioselectivity, even under ambient pressure of hydrogen.

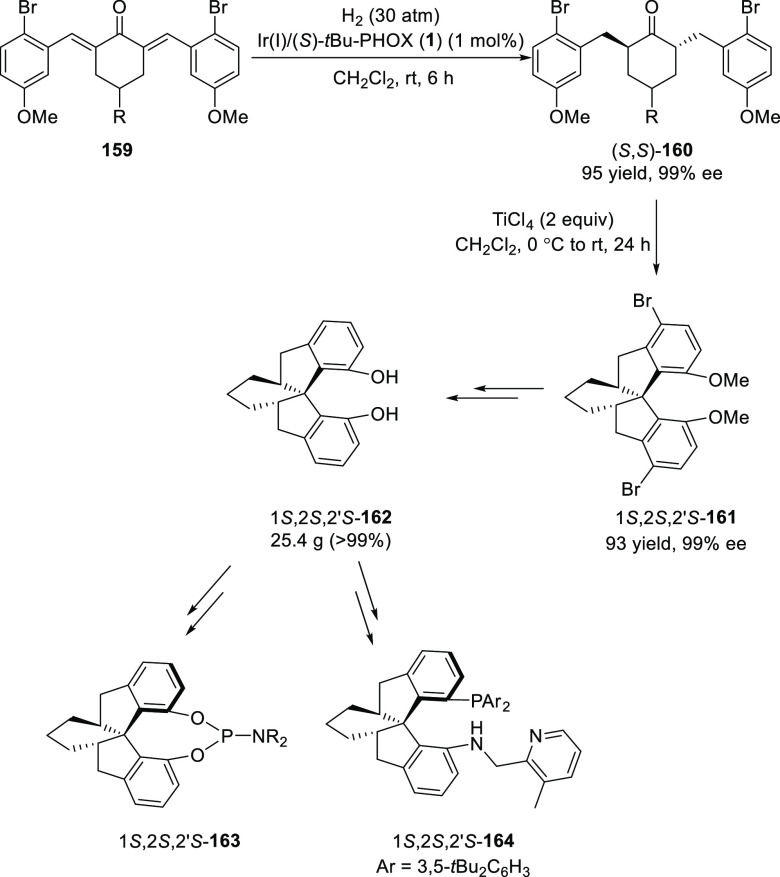

Ding reported an enantioselective synthesis of cyclohexyl-fused chiral spirobiindane derivative (161) via a sequence of an Ir-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of α,α′-bis(arylidene)ketones (159), followed by an asymmetric spiroannulation of hydrogenated chiral ketones (160) promoted by TiCl4 (Scheme 44).58 A variety of cyclohexyl-fused chiral spirobiindanes (161) were synthesized in high yields and excellent stereoselectivities (up to >99% ee). The asymmetric synthesis of cyclohexyl-fused spiroindanediol (1S,2S,2′S)-162, was carried out in >99% ee and 67% overall yield over four steps without chromatographic purification. The (1S,2S,2′S)-162 was then used to access chiral monodentate phosphoramidites 164 and tridentate phosphorus-aminopyridine 164 and the applications of these ligands were shown in various metal-catalyzed enantioselective reactions including hydrogenation, hydroacylation, and [2 + 2] reactions. The catalytic performances of these ligands were very similar to the corresponding well-established spirobiindane backbone based privileged ligands.

Scheme 44. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of α,α′-Bis(arylidene)ketones.

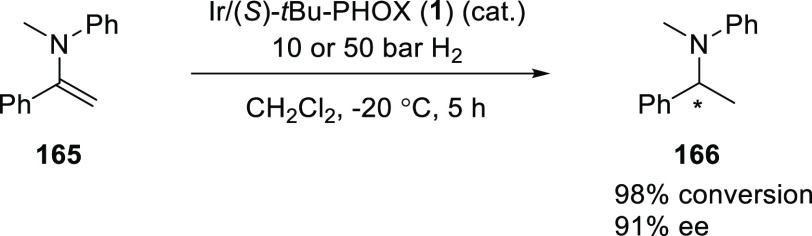

Pfaltz discovered an asymmetric hydrogenation of enamines (165) catalyzed by cationic Ir complexes derived from tBu-PHOX (1) (Scheme 45).59 The level of enantioselectivites observed in these hydrogenations greatly depend on the substitution pattern at the double bond and the nitrogen atom. An N-aryl or N-benzyl group seems to have a beneficial effect on the enantioselectivity (>90% ee), whereas enantioselectivities for the hydrogenation of cyclic and acyclic 1,2-disubstituted enamines were lower.

Scheme 45. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Enamines.

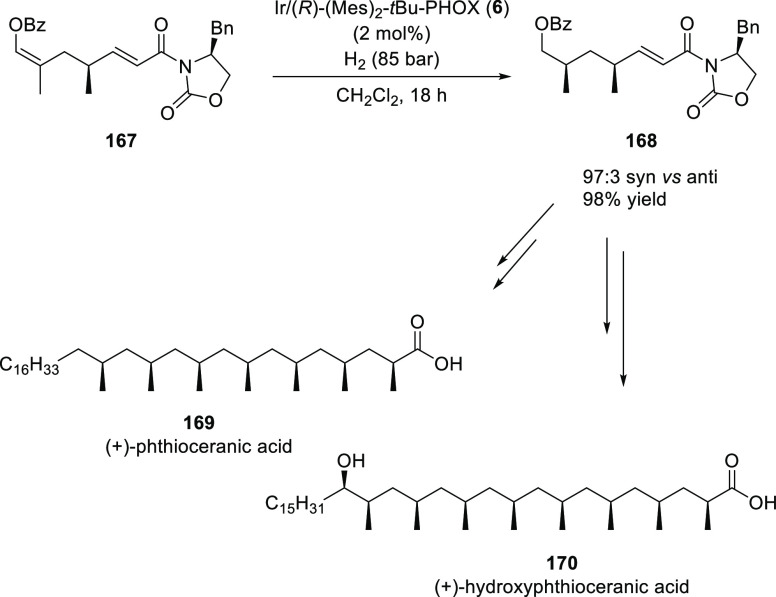

Pfaltz applied an Ir-catalyzed hydrogenation for the stereoselective and flexible synthesis of long-chain polydeoxypropionates (Scheme 46).60,61 The Ir complex of chiral PHOX-ligand 6 catalyzed the hydrogenation of 167 with excellent levels of diastereoselectivity. The benzoate anti-167 were obtained with 96:4 diastereoselectivity and >95% isolated yield. Interestingly the opposite diastereofacial selectivity was obtained when the mesityl group on the phosphine ligand was changed to an o-tolyl or a cyclohexyl. Hydrogenated benzoate 168 was further utilized to complete the synthesis of the glycolipid components (+)-phthioceranic acid (169) and (+)-hydroxyphthioceranic acid (170).

Scheme 46. Stereoselective Hydrogenation of 167.

Hou reported an Ir-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of unfunctionalized alkenes (171), α,β-unsaturated esters (157), allyl alcohols, α,β-unsaturated ketones (157), and ketimines (173) using benzylic substituted PHOX ligand 14 (Scheme 47).62 A wide range of substrates were successfully reduced to the corresponding chiral products (172, 158, and 174) with high conversions and high ee values (>99% conversion and up to 99% ee). The reaction of (Z)- and (E)-alkenes gave rise to enantiomeric products in almost the similar enantiomeric excess catalyzed by the same Ir-PHOX 14 complex. The reported P,N-ligands have a six-membered ring with Ir, whereas ligand 14 which is derived from a benzylic substituted P,N-ligand has a seven-membered ring. The increased tether length is more flexible and is believed to have a better chance to fit the steric demands of various substrates. The slightly larger bite angle of ligand was confirmed by X-ray analysis of the corresponding Ir complex.

Scheme 47. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Unfunctionalized Alkenes.

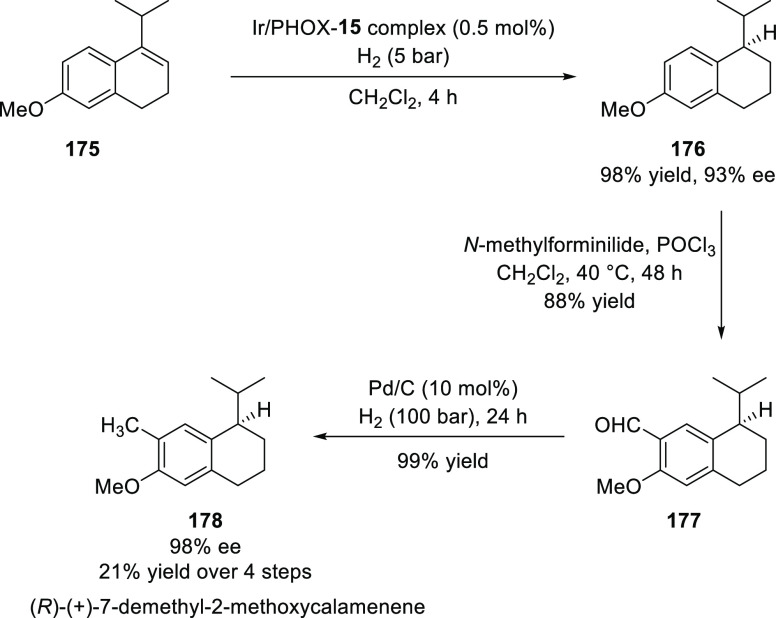

Pfaltz reported a further Ir-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of unfunctionalized and functionalized alkenes (175) using a new P,N-ligand 15 introduced from their group (Scheme 48).63 The application of their methodology was demonstrated in the synthesis of the antitumor natural product, (R)-(+)-7-demethyl-2-methoxycalamenene (178), a superior approach to an earlier published route with respect to the number of steps and the overall yield (4 steps, 21% overall yield and 98% ee). The catalytic system was also extended to the asymmetric hydrogenation of allylic alcohols, α,β-unsaturated esters and imines which resulted in the corresponding products in good to excellent ees (up to 96%).

Scheme 48. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Unfunctionalized Alkenes.

Pfaltz described a cationic Ir/chiral P,N-ligand 16 system for the efficient asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-substituted N-protected indoles (179) (Scheme 49).64 The Ir catalyst employed is highly air and moisture sensitive. Various indoles with N-Boc-, N-acetyl-, and N-tosyl protecting groups were hydrogenated in excellent yields and enantioselectivities. The influence of N-protection on the reactivity and enantiomeric excess was lessened by employing the right combination of the catalytic system.

Scheme 49. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of 2-Substituted N-Protected Indoles.

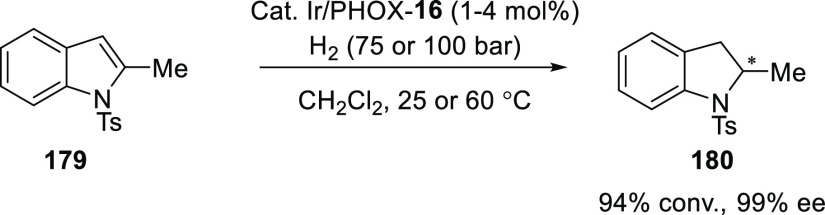

Kuwano developed an Ir-catalyzed enantioselective hydrogenation of isoxazolium triflates (181 and 183) to furnish enantioenriched 4-isoxazolines (182) or isoxazolidines (184) (Scheme 50).65 The hydrogenation of 5-arylisoxazolium triflates (181) exclusively provided the corresponding 4-isoxazolines (182) with good enantioselectivities (up to 90% ee) whereas 5-alkylated isoxazolium triflates (183) selectively furnished cis-3,5-disubstituted isoxazolidines (184) with ees up to 78%. The enantioselectivity was strongly affected by the hindrance from the 5-substituent on the isoxazole ring. Interestingly, the commonly occurred and undesired N–O bond cleavage was not observed under the reaction conditions employed.

Scheme 50. Enantioselective Hydrogenation of Isoxazolium Triflates.

2.1.1.4. Application of PHOX in Addition of Arylboronic Acids to Alkyne, Allene, or Imine

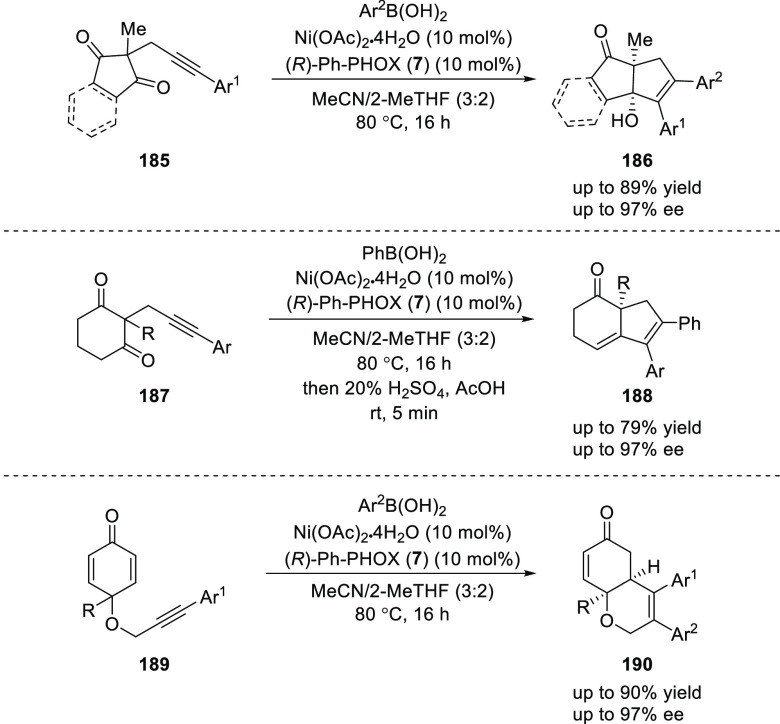

Lam reported a Ni/(R)-Ph-PHOX (7)-catalyzed reaction of arylboronic acids with alkynes (185, 187, and 189) followed by the enantioselective cyclization of an alkenyl Ni species onto a tethered electrophilic trap such as ketones or enones (Scheme 51).66 The success of this domino cyclization is reliant upon the formal anti-carbonickelation of the alkyne, which is suggested to occur by the reversible E/Z-isomerization of an alkenylnickel species.

Scheme 51. Enantioselective Domino Cyclization of Tethered Alkynes.

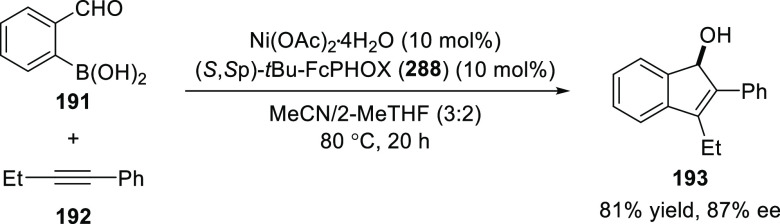

Furthermore, an intramolecular reaction between 1-phenyl-1-butyne (192) and 2-formylphenylboronic acid (191) using (S,Sp)-tBu-FcPHOX (288) (discussed in detail in section 2.3) furnished the expected indene 193 in 81% yield and 87% ee via a syn-arylnickelation of the alkyne followed by cyclization of the resulting alkenylnickel species onto the aldehyde (Scheme 52). Interestingly, the same chiral ligand, (S,Sp)-tBu-FcPHOX (288), earlier furnished a product via anti-arylnickelation. The ability to synthesize enantioenriched products from either a syn- or anti-carbometallative cyclization further suggests that reversible E/Z-isomerization of the alkenylnickel species is operative and also demonstrates the adaptive power of this Ni-based catalytic system.

Scheme 52. Intramolecular Reaction between 1-Phenyl-1-butyne and 2-Formylphenylboronic Acid.

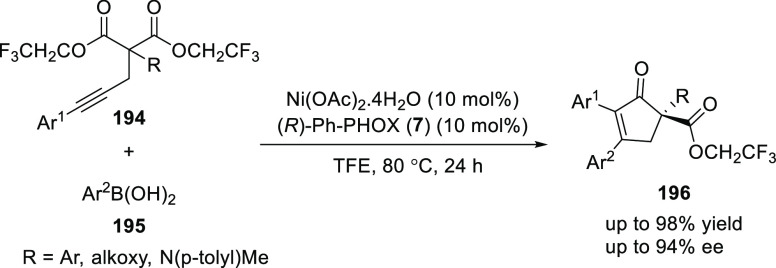

Lam reported a Ni/(R)-Ph-PHOX (7)-catalyzed desymmetrizing arylative cyclization for the enantioselective synthesis of chiral cyclopent-2-enones (196) by using alkynyl bis(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl) malonates (194) and arylboronic acids (195) (Scheme 53).67 A wide variety of cyclopent-2-enones (196) containing a quaternary stereocenter were synthesized in good yields and excellent enantioselectivities (up to 98% and 94% ee). This cyclization was promoted by the reversible E/Z-isomerization of the alkenylnickel species formed during the reaction.

Scheme 53. Desymmetrizing Arylative Cyclization of Alkynyl Bis(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl) Malonates.

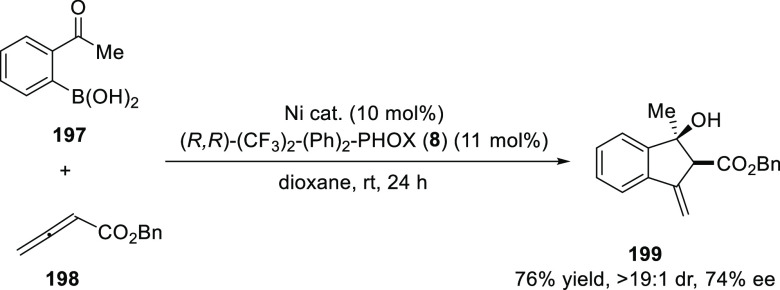

Lam developed a Ni-catalyzed highly diastereoselective annulation between 2-acetylphenylboronic acid (197) or 2-formylarylboronic acid and activated allenes (198) to furnish 3-methyleneindanols (199) (Scheme 54).68 Preliminary results using the chiral phosphinooxazoline ligand, (R,R)-(CF3)2-(Ph)2-PHOX (8) furnished the product in 76% yield and good stereoselectivities (19:1 dr and 74% ee).

Scheme 54. Diastereoselective Annulations between 2-Acetylphenylboronic Acid and Allene.

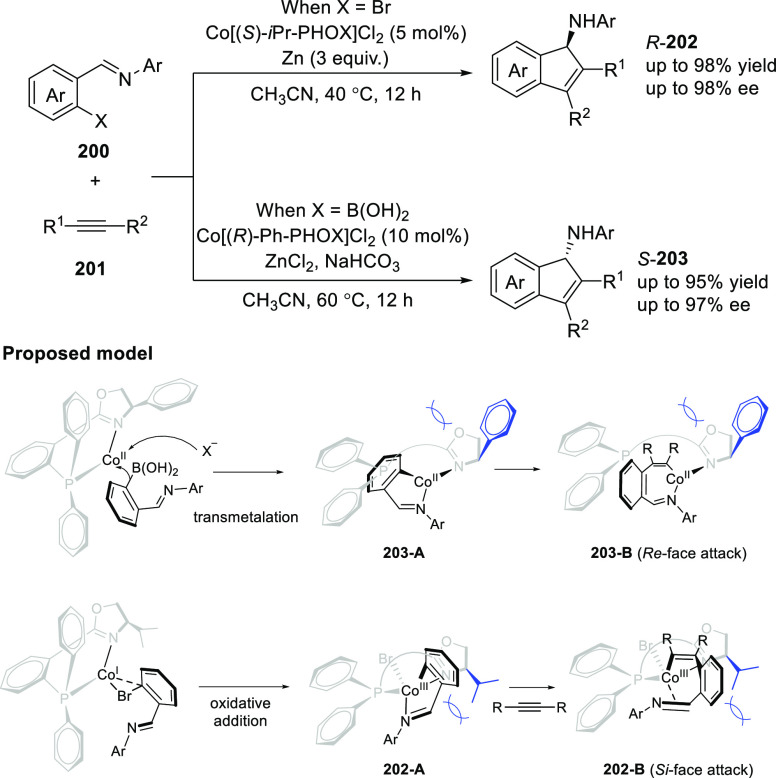

Cheng reported the synthesis of chiral 1-aminoindenes (202/203) through an intramolecular reaction between o-imodoylarylboronic acids or aryl halides or pseudohalides (200) with alkynes (201) using a Co/chiral PHOX-catalyzed enantioselective [3 + 2] annulation reaction (Scheme 55).69 This reaction achieved a controlled synthesis of both enantiomers of variety of 1-aminoindenes (202/203) in high yields and good to excellent enantioselectivities (up to 98% yield and 98% ee). The unsymmetrical alkynes reacted regioselectively affording single stereoisomers in high yield and excellent ee values. The role of ZnCl2 was found to be crucial as it dramatically enhanced the yield without any negative effect on enantioselectivity. The configuration of the desired product is dominated and controlled by the steric bulk of the substituent attached to the nitrogen-adjacent carbon on the oxazoline ring. As demonstrated in the proposed model, the phenyl group of complex 203-A forces the R group to be far away from the oxazoline moiety and leads the subsequent intramolecular addition of imine from the Re-face, while the isopropyl group of complex 202-A leads to Si-face insertion.

Scheme 55. Enantioselective [3 + 2] Annulation Reaction.

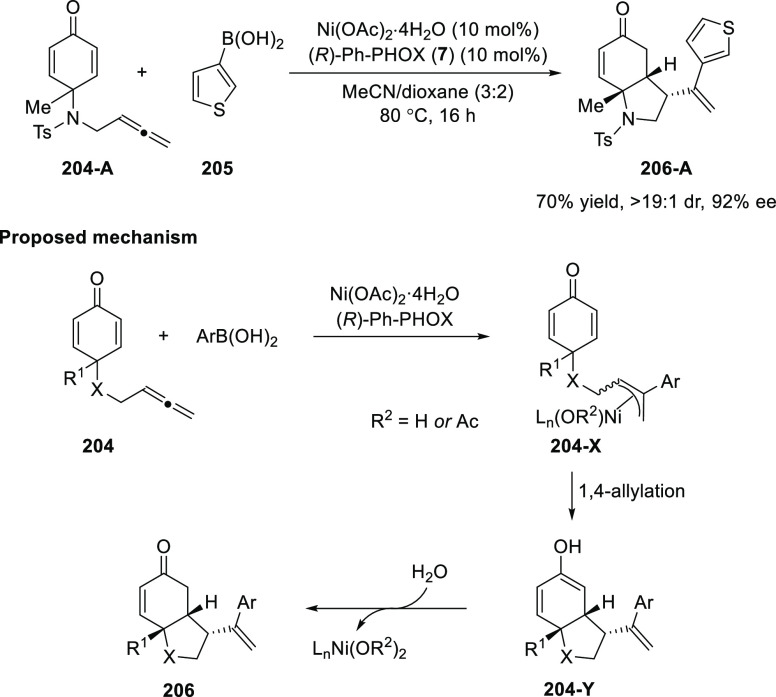

Lam and co-workers earlier discovered that the Ni/(R)-Ph-PHOX (7) complex is highly effective in promoting enantioselective anticarbometallative cyclizations of alkynyl electrophiles with arylboronic acids.66−68 They hypothesized that Ni/(R)-Ph-PHOX (7) complex could also promote a catalytic enantioselective intramolecular 1,4-allylation of substrates containing an allene tethered to an electron-deficient alkene. Considering these facts Lam 2018 described the enantioselective Ni-catalyzed arylative desymmetrization of allenyl cyclohexa-2,5-dienones (204-A) by using arylboronic acids (205) (Scheme 56).70 A variety of hexahydroindol-5-ones and hexahydrobenzofuran-5-ones with three contiguous stereocenters were synthesized in moderate to good yield with high diastereo- and enantioselectivities. The proposed mechanism begins with the Ni/(R)-Ph-PHOX (7)-catalyzed addition of an arylboronic acid to an allenyl cyclohexa-2,5-dienone (204). The resulting allylnickel species 204-X would undergo intramolecular 1,4-allylation to give nickel enolate 204-Y, which upon protonation would liberate the Ni(II) catalyst and a cis-fused hexahydroindol-5-one or hexahydrobenzofuran-5-one (206).

Scheme 56. Enantioselective Ni-Catalyzed Desymmetrization of Allenyl Cyclohexa-2,5-dienones.

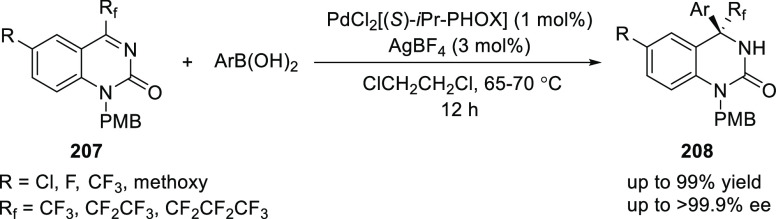

In 2016, Hayashi reported a Pd-catalyzed asymmetric arylation of fluoroalkyl-substituted 2-quinazolinone derivatives (207) with arylboronic acids using (S)-iPr-PHOX (4) ligand (Scheme 57).71 A variety of trifluoromethylated and perfluoromethylated 2-quinazoline (208) products possessing quaternary carbon stereocenters were synthesized in excellent enantioselectivities (>99% ee).

Scheme 57. Pd-Catalyzed Asymmetric Arylation.

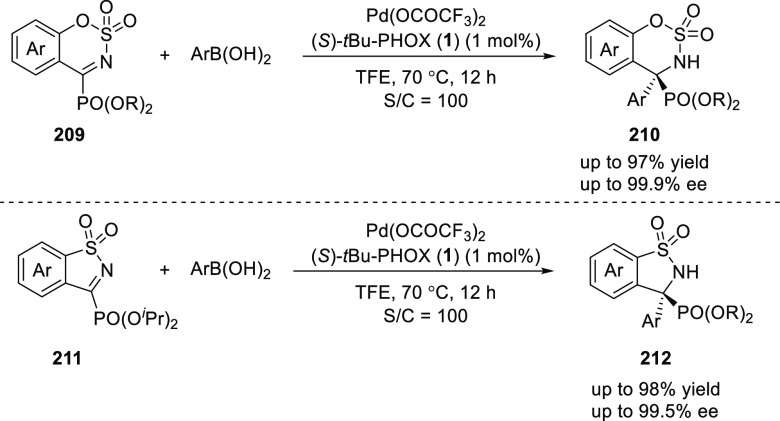

Later, Zhou employed a Pd-catalyzed enantioselective addition of arylboronic acids to five- and six-membered cyclic α-ketiminophosphonates (209/211) using (S)-tBu-PHOX (1) ligand (Scheme 58).72 The method provided an elegant and efficient route to access chiral α-aminophosphonates (210/212) possessing a quaternary carbon stereocenter in high yields and excellent enantioselectivities (up to 99.9% ee). The use of low catalytic loading and a wide substrate scope are the highlights of this arylation methodology.

Scheme 58. Enantioselective Addition of Arylboronic Acids to Cyclic α-Ketiminophosphonates.

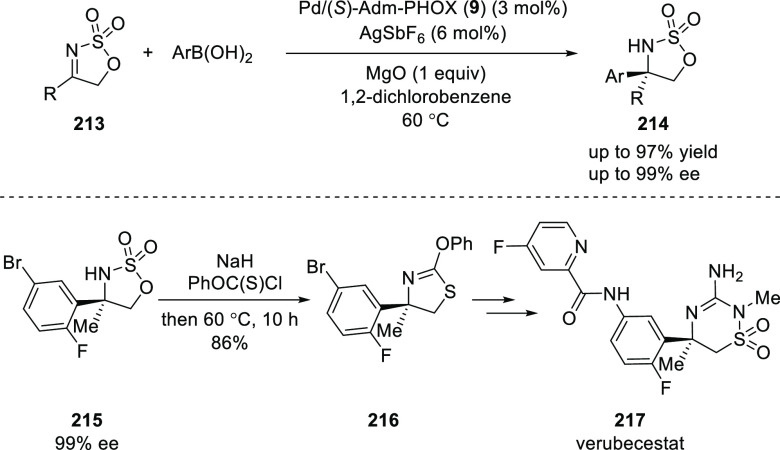

Chen reported a Pd-catalyzed enantioselective addition of arylboronic acids to cyclic iminosulfates (213) using an adamantyl-substituted phosphinooxazoline ligand 9 (Scheme 59).73 This enantioselective arylation tolerates a wide variety of arylboronic acids as well as cyclic iminosulfates to provide cyclic sulfamidates (214) in high yields with excellent ees (up to 97% yield and up to 99% ee). The methodology was applied to synthesize verubecestat (217), a compound under clinical evaluation for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

Scheme 59. Enantioselective Addition of Arylboronic Acids to Cyclic Iminosulfates.

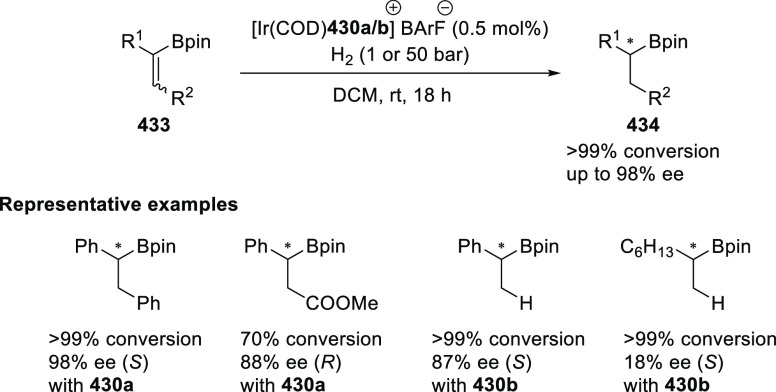

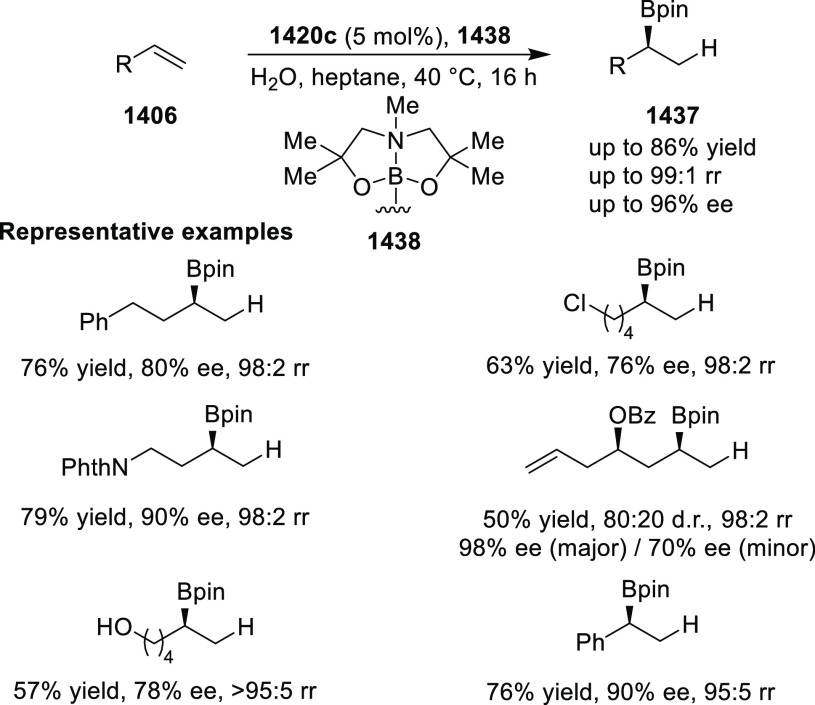

2.1.1.5. Application of PHOX in Asymmetric Borylation of Alkenes

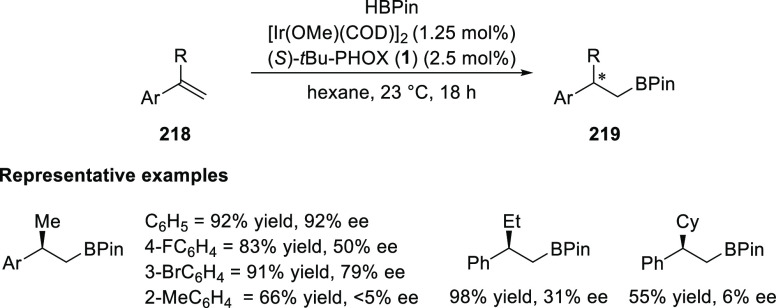

In 2011, Mazet developed an Ir-catalyzed regio- and enantioselective hydroboration of terminal olefins (218) using the tBu-PHOX (1) ligand (Scheme 60).74 The reaction is highly dependent on sterics as changing the R group from methyl to ethyl or cyclohexyl or by replacing the phenyl ring with an o-tolyl group radically decreased the enantioselectivity of the expected hydroboration products.

Scheme 60. Enantioselective Hydroboration of Terminal Olefins.

2.1.1.6. Application of PHOX in Asymmetric α-Arylation

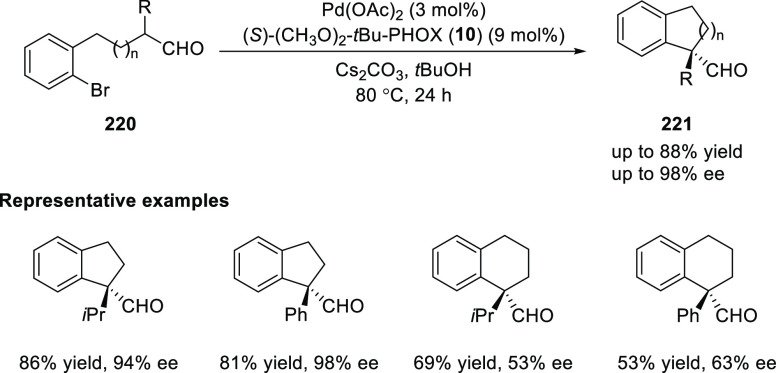

Buchwald reported a Pd-catalyzed α-arylation of aldehydes (220) forming all-carbon-substituted asymmetric centers in high yields and enantioselectivities (Scheme 61).75 Generally, substrates with α-aryl substituents gave rise to products with higher optical purity than these with α-alkyl analogues. The efficiency of the method is excellent for substrates forming five-membered rings, but it dropped significantly for substrates forming a six-membered ring; tetrahydronaphthalene derivatives were prepared in moderate to good yields with moderate levels of enantioselectivity.

Scheme 61. Enantioselective α-Arylation of Aldehydes.

2.1.1.7. Application of PHOX in Asymmetric [2 + 2] Cycloaddition

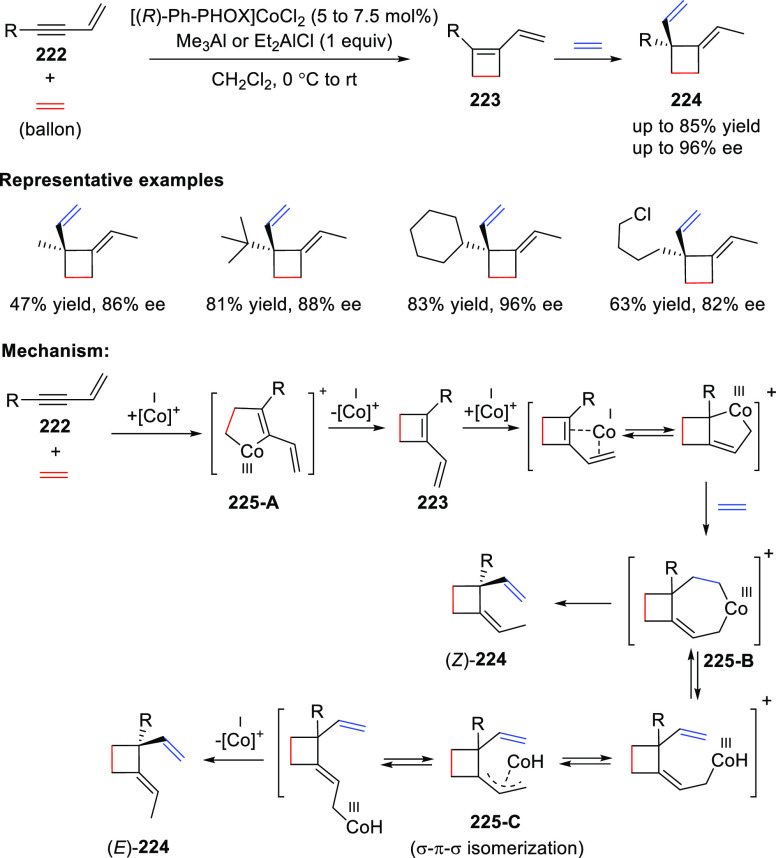

In 2018, Rajanbabu reported a Co/(R)-Ph-PHOX (7)-catalyzed [2 + 2] cycloaddition between 1,3-enynes (222) and ethylene followed by an enantioselective hydrovinylation of the resulting vinylcyclobutene (223) to give highly functionalized cyclobutanes (224) with an all-carbon quaternary stereocenter, as the (E)-isomer (Scheme 62).76 The reaction proceeds in a tandem fashion to form three highly selective C–C bonds in one pot using a single chiral Co catalyst. The use of an activator, Et2AlCl, was important to promote this cycloaddition reaction. The cycloaddition initiates with an oxidative dimerization of ethylene and the enyne (222) in the coordination sphere of an activated Co(I) species to afford a metallacyclopentene 225-A, which after reductive elimination provides cyclobutene 223. This diene 223 further undergoes oxidative dimerization with ethylene to deliver the metallacycloheptene 225-B. Sterically congested 225-B, (Z)-allylcobalt(III)-hydride undergoes (Z)/(E)-isomerization through an η3-(allyl) intermediate 225-C, which upon β-hydrogen elimination and reductive elimination finally leads to the (E)-224 isomer as the major product. The ratio of (Z)- and (E)-isomers depended on the nature of the R substituent and the nature of the ligand used.

Scheme 62. Asymmetric [2 + 2] Cycloaddition between 1,3-Enynes and Ethylene.

2.1.1.8. Application of PHOX in Asymmetric Heck Reaction

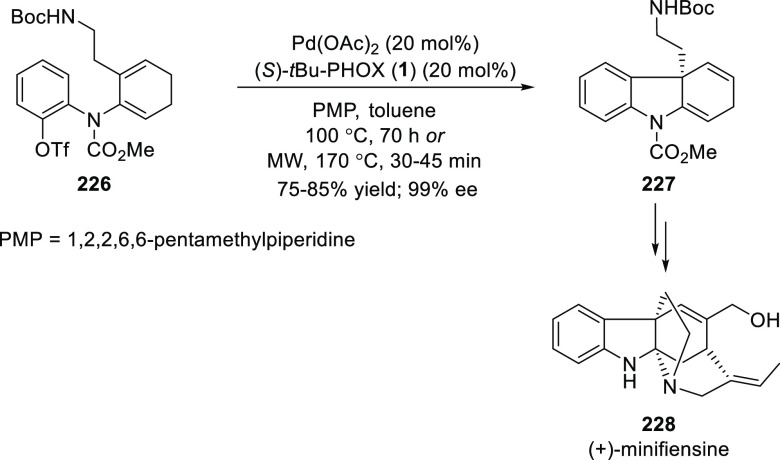

Overman and Wrobleski reported a synthesis of (+)-minifiensine (228), which involves an asymmetric Heck-cyclization of dienyl aryl triflate 226 using a catalytic amount of Pd and (S)-tBu-PHOX (1) as the key step to provide dihydrocarbazole 227 in 99% ee (Scheme 63).77 It is noteworthy that microwave heating (170 °C) was employed to accelerate this catalytic transformation.

Scheme 63. Asymmetric Heck-Cyclization of Dienyl Aryl Triflate 226.

In 2009, Guiry reported a Pd-catalyzed intermolecular asymmetric Heck reaction between 2,3-dihydrofuran (94) and a range of triflates using HetPHOX ligands (Scheme 64).78 The HetPHOX ligand derived from tert-leucinol and di-o-tolylphosphine, (S)-(o-tol)2-tBu-ThioPHOX (11) proved the most effective affording ee values of up to 96, 95, and 94% in the phenylation, cyclohexenylation (using triflate (229)), and naphthylation, respectively, of 2,3-dihydrofuran.

Scheme 64. Intermolecular Asymmetric Heck Reaction.

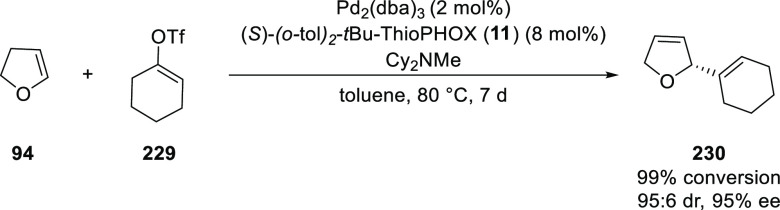

Zhu reported an asymmetric reductive Heck reaction using a catalytic amount of Pd, (S)-tBu-PHOX (1) and diboron-H2O as a hydride source (Scheme 65).79 This method was applied to synthesize a library of enantioenriched oxindoles (232) possessing a C3-quaternary stereocenter in excellent yields and enantioselectivities. Alkenes possessing aryl and alkyl groups at R2 were compatible. The use of D2O instead of H2O as a D-donor enabled the synthesis of CH2D substituted oxindoles. The catalytic cycle initiates with oxidative addition of the tBu-PHOX (1) ligated Pd(0) to aryl triflate 231, followed by intramolecular carbopalladation, generating a cationic alkyl-Pd(II) intermediate 231-A which reacts with B2(OH)4 and H2O in a series of steps to afford alkyl-Pd(II)-H species 231-E Finally, reductive elimination from 231-E provides the desired product 232 with simultaneous regeneration of the Pd(0)/tBu-PHOX (1) catalyst.

Scheme 65. Asymmetric Reductive Heck Reaction.

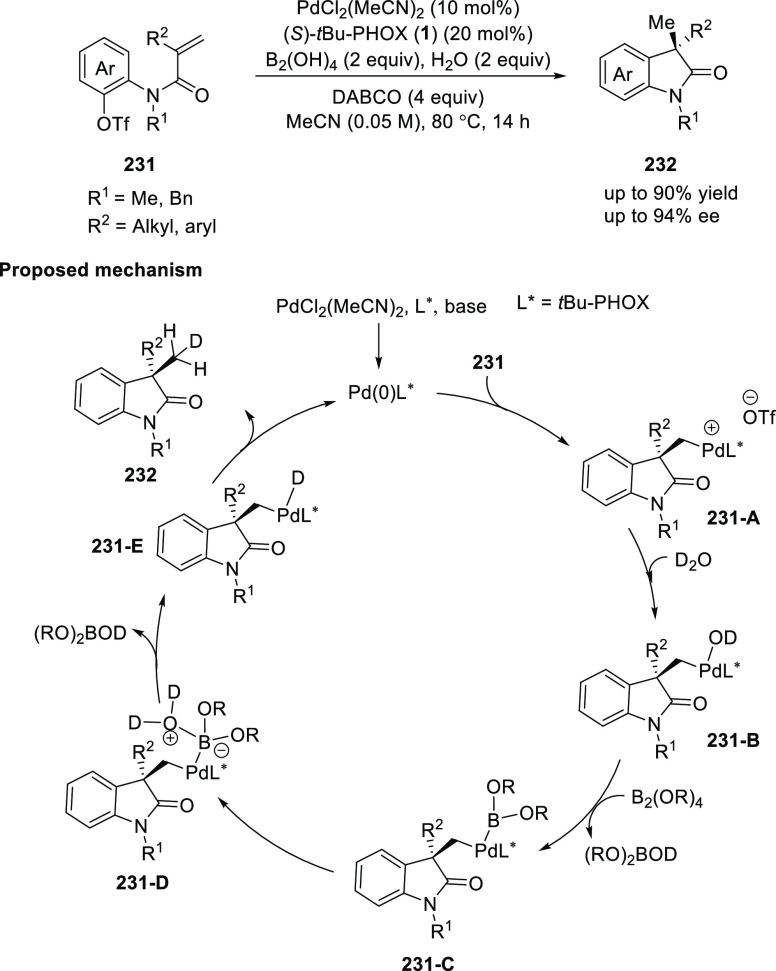

Tong developed a Pd-catalyzed asymmetric vinylborylation of (Z)-1-iodo-diene (233) with B2Pin2 using (S)-CF3–Bn-PHOX (12) (Scheme 66).80 This method allowed them to synthesize a variety of 3,3-disubstituted tetrahydropyridines (234) derivatives in good yields and high enantioselectivities. The choice of the tether between vinyl iodide and the alkene had a strong effect on the reaction outcome, as a tether with a strong coordinating atom with Pd had a positive effect and this protocol was limited to the synthesis of a 6-membered cyclic product. This reaction begins by the oxidative addition of Pd(0) to vinyl iodide followed by a Ag-mediated transmetalation with B2Pin2 to form a vinyl-Pd(II)-Bpin species which, upon intramolecular enantioselective carbopalladation followed by reductive elimination, furnished the expected product. Mechanistic studies revealed that the transmetalation step occurs before the alkene insertion, which was complementary to the previous understanding of a similar reaction.

Scheme 66. Asymmetric Vinylborylation.

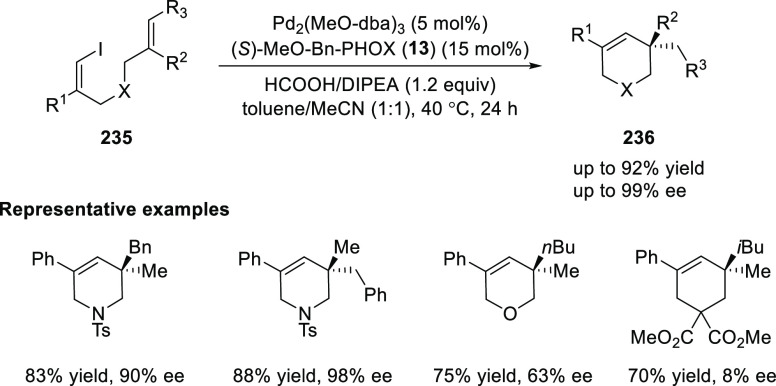

In 2017, Tong developed an asymmetric reductive Heck cyclization of (Z)-1-iodo-1,6-dienes (235) using Pd2(dba-OMe)3 and (S)-MeO-Bn-PHOX (13) as the ligand (Scheme 67).81 This method provided a facile access to chiral quaternary tetrahydropyridines (236) with good to excellent yields and enantioselectivities. Additionally, this method tolerates susceptible β-hydrogen elimination and a substrate bearing a trisubstituted alkene. The linker between the vinyl iodides and alkenes as well as substituent R1, R2, and R3 had a strong influence on the yield and enantioselectivity of product.

Scheme 67. Asymmetric Reductive Heck Cyclization.

2.1.1.9. Application of PHOX in Asymmetric Alkylation

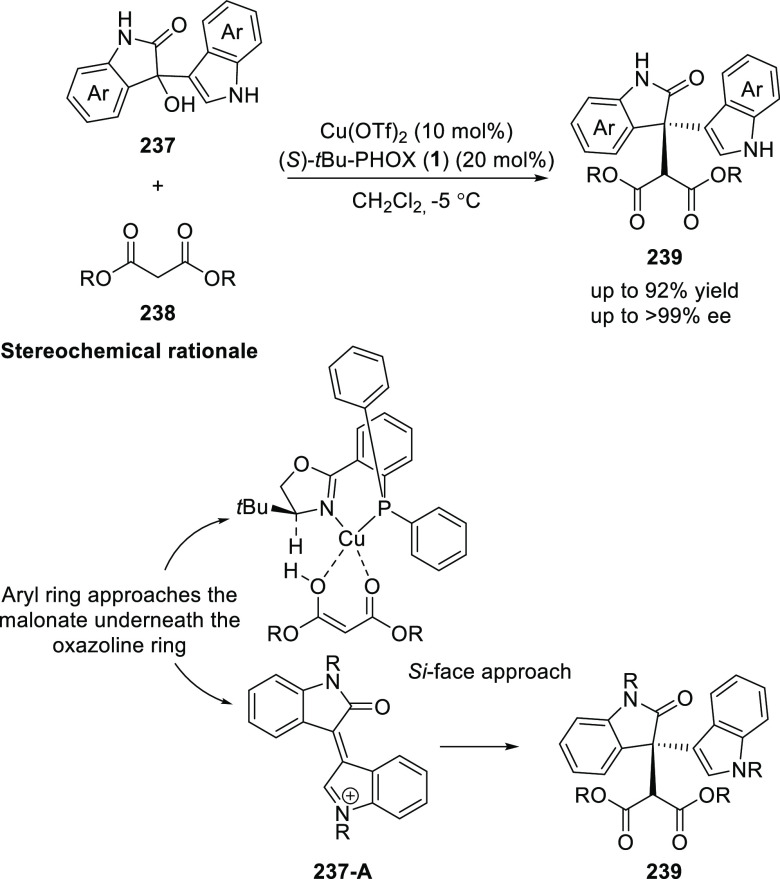

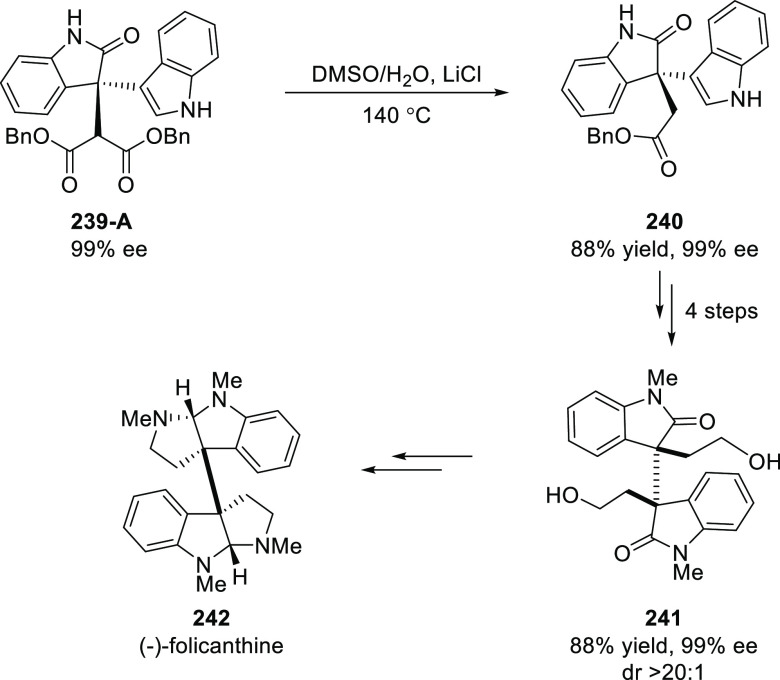

In 2018, Bisai reported a Cu-catalyzed asymmetric alkylation of 3-hydroxy-2-oxindole (237) with a variety of malonates (238) using the tBu-PHOX (1) ligand (Scheme 68).82 The presence of an indole moiety at C3 is critical for success and no reaction occurred when indole was replaced with an alkyl group. This observation suggested in situ formation of a highly reactive intermediate 237-A followed by an enantioselective malonate addition. The mechanistic studies confirmed that the reaction is reversible in nature and the involvement of a Cu(II)-complex with a distorted trigonal bipyramid (TBP) geometry.

Scheme 68. Asymmetric Alkylation of 3-Hydroxy-2-oxindole.

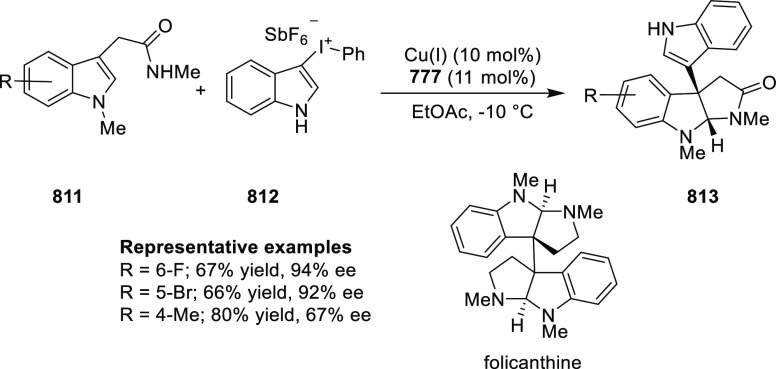

The application of the method was illustrated in the formal total synthesis of (−)-folicanthine (242) by synthesizing a C2-symmetric dimeric 2-oxindole 241 possessing an all-carbon quaternary stereocenter in 5 steps (Scheme 69).

Scheme 69. Synthesis of (−)-Folicanthine.

2.1.1.10. Application of PHOX in Desymmetrizing Cross-Coupling

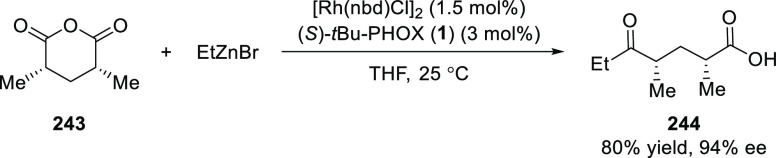

Rovis reported a Rh/tBu-PHOX (1)-catalyzed cross-coupling between sp3 organozinc reagents and 3,5-dimethylglutaric anhydride (243) (Scheme 70).83 A variety of syn-deoxypolypropionates (244) were synthesized in excellent yields and good to excellent enantioselectivities. This catalytic system worked well with alkyl and benzyl zinc reagents possessing various functionalities, however it was less efficient with phenyl and isopropyl zinc reagents.

Scheme 70. Desymmetrizing Cross-Coupling.

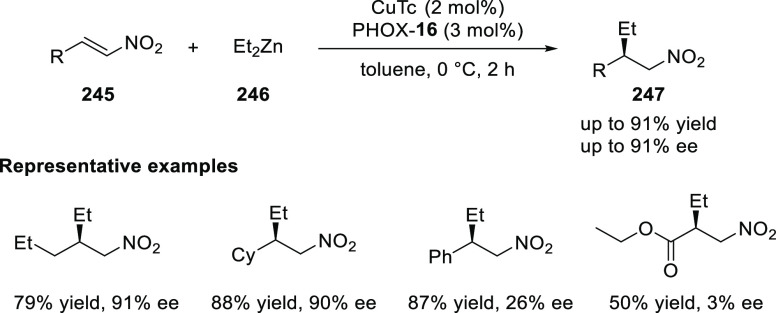

2.1.1.11. Application of PHOX in Asymmetric Conjugate Addition

Jung reported a Cu-catalyzed asymmetric conjugate addition of alkylzinc reagents to nitroalkenes (245) and cyclic enones by using the newly synthesized P,N-ligand 16 (Scheme 71).84 A variety of chiral nitroalkanes (247) and β-alkyl cyclic ketones were synthesized in good yields and good enantioselectivity (up to 92% yield and 95% ee). Computational studies suggested that the chiral substituents in the oxazoline moiety of P,N-ligand 16 are not crucial for the selectivity whereas the other alkyl substituent in the bridging moiety is involved in the steric repulsion during the transition state.

Scheme 71. Asymmetric Conjugate Addition.

Metal complexes of PHOX ligands with one stereocenter (1–17) have been extensively studied in the past decade. These complexes have been successfully applied in various asymmetric transformations. Palladium complexes were excellent for (I) decarboxylative allylic alkylation and protonation, (II) Heck reaction, (III) hydroamination and alkylation of diene, (IV) [3 + 2] cycloaddition, (V) Meerwein-Eschenmoser and Saucy-Marbet Claisen rearrangement, (VI) aryl boronic acid addition to various imines. Iridium complexes were mostly utilized in hydrogenation of diverse types of alkenes and imines wheras nickel complexes showed excellent results when employed in annulation reactions between aryl boronic acids and alkynes, allenes and imines. Cobalt complexes were specifically successful in (I) intramolecular reactions between o-imodoylarylboronic acids or aryl halides or pseudohalides with alkynes, and (II) [2 + 2] cycloadditions between 1,3-enynes and ethylene. Copper complexes were successfully employed in (I) asymmetric alkylations of 3-hydroxy-2-oxindole, and (II) asymmetric conjugate additions of alkylzinc reagents to nitroalkenes while rhodium complexes found their application in desymmetrizations of 3,5-dimethylglutaric anhydride with alkyl zinc bomides. It is evident from the literature covered in this section of the review that PHOX ligands with only one stereocenter are adaptable with various metals and hence researchers should seek to continue to expand their utilization in asymmetric catalysis.

2.1.2. Phosphinooxazoline Ligands with Stereoaxis or Stereocenter

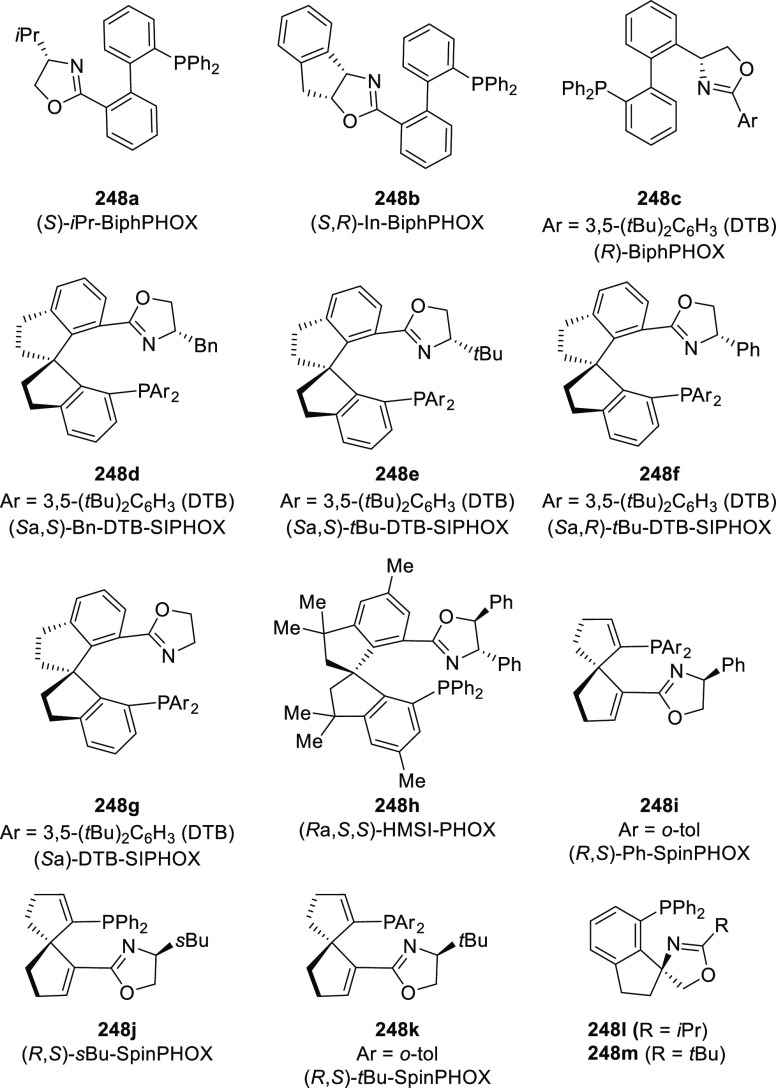

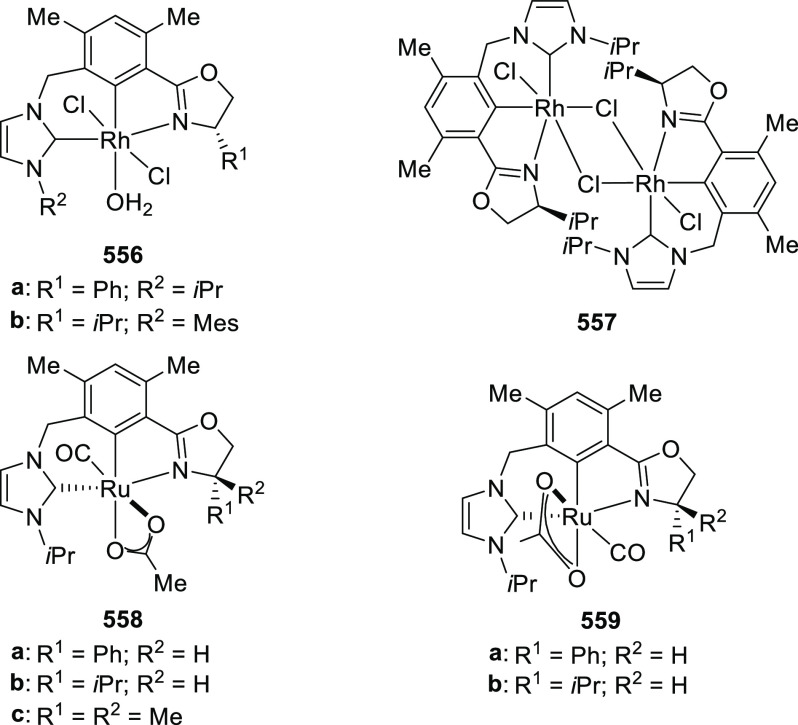

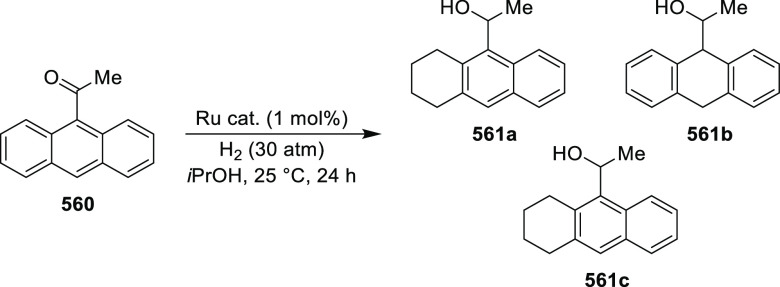

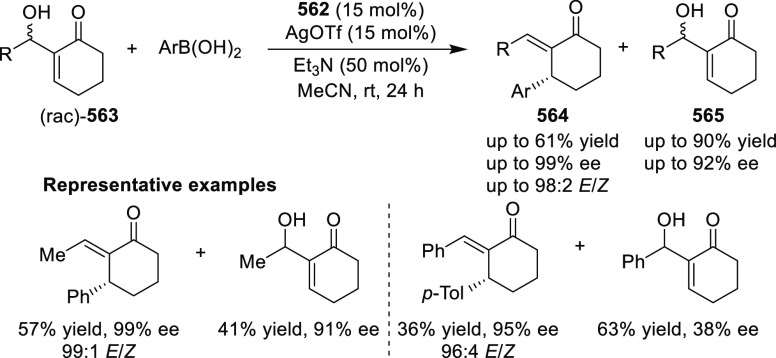

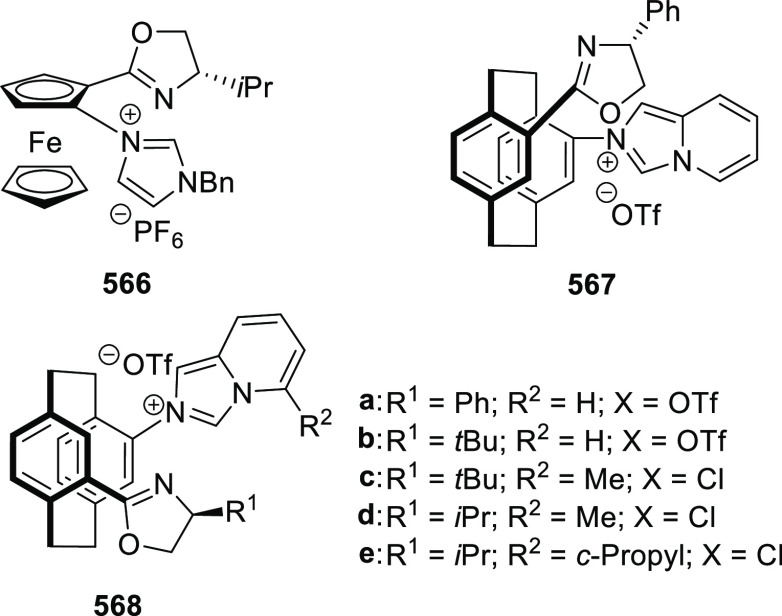

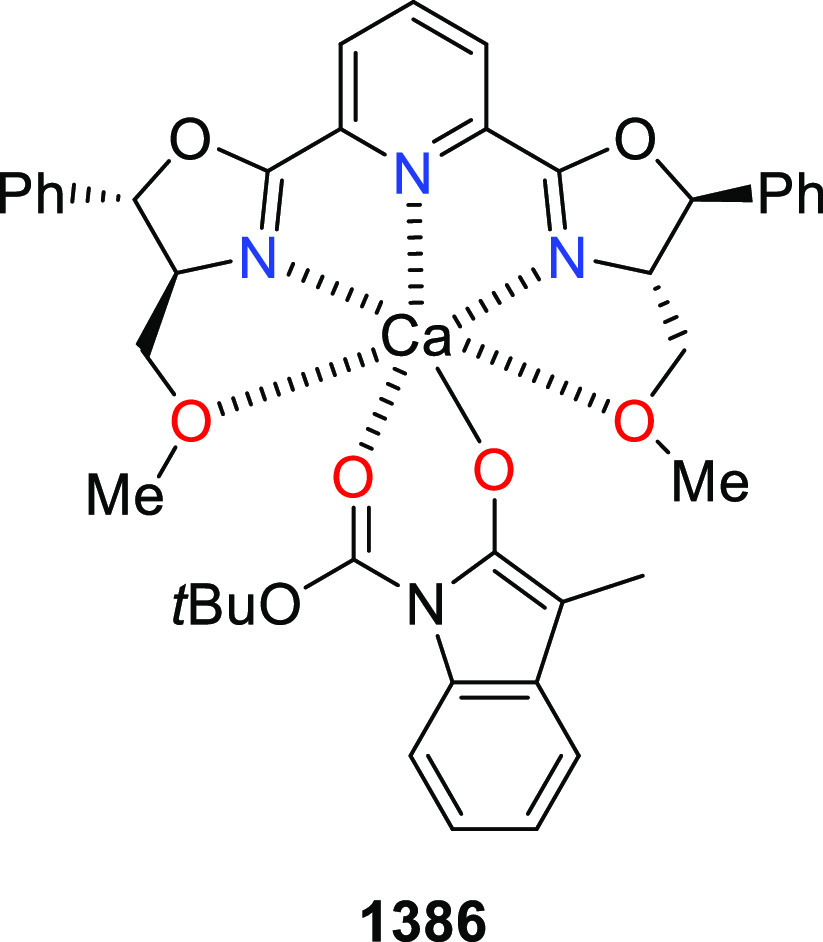

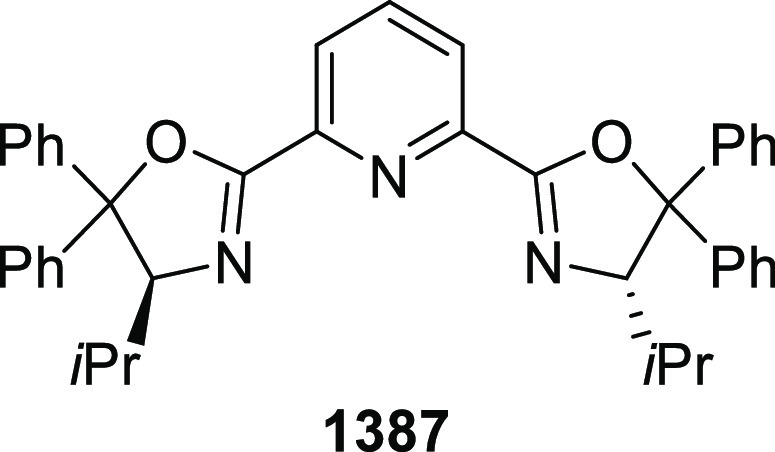

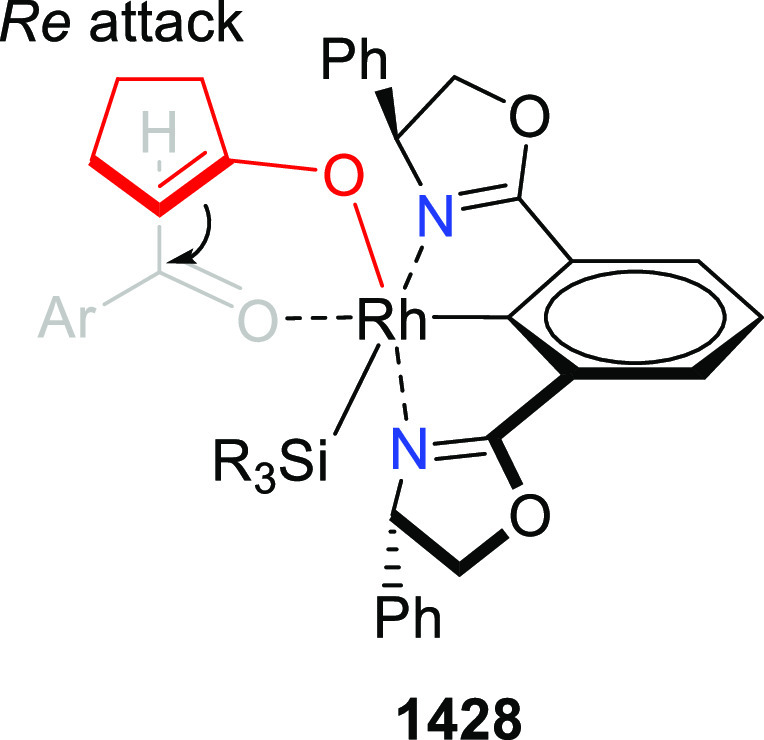

This section deals with the application of phosphinooxazoline ligands (248a–m) possessing a stereoaxis or stereocenter in metal-catalyzed enantioselective reactions (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Phosphinooxazoline ligands with a stereocenter or stereoaxis.

2.1.2.1. BiphPHOX Ligands

BiphPHOX ligands (248a–b) possess a chiral oxazoline ring and exist as an equilibrium mixture of diastereomers in solution due to rotation around the internal bond of the biphenyl groups. Interestingly, when these ligands coordinate to Pd or Ir, only one of two possible diastereomeric complexes are formed. The Zhang group extensively utilized the metal-complexes of BiphPHOX ligands (248a–b) in the Ir-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of variably substituted olefins and in the Ni-catalyzed arylation of cyclic aldimines and ketimines.

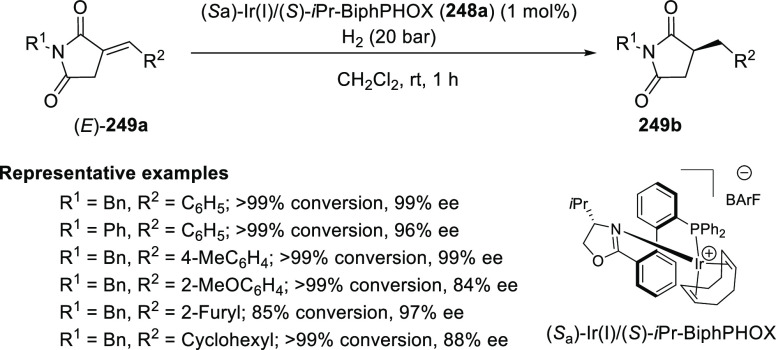

In 2013, Zhang reported the first asymmetric hydrogenation of α-alkylidene succinimides (249a) using an Ir/(S)-iPr-BiphPHOX (248a) complex (1 mol %) to afford hydrogenated products (249b) in excellent yields (>99%) and enantioselectivities (up to 99% ee) under 20 bar H2 (Scheme 72).85 The reactions performed under reduced catalytic loading (0.05 mol %) and reduced pressure (1 bar) were successful although at the expense of a prolonged reaction time. The iPr substituent on the oxazoline ring had a strong impact on the enantioselectivity (99% ee). The α-alkylidene succinimide (249a) with (E)-configuration was essential for the success of hydrogenation whereas the N-protecting group did not affect the yield and enantioselectivity of the reaction.

Scheme 72. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of α-Alkylidene Succinimides.

In a subsequent study, Zhang described the first asymmetric hydrogenation of unfunctionalized exocyclic C=C bonds (250) with Ir and In-BiphPHOX (248b) delivering the expected chiral 1-benzyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-indene products (251) in up to 98% ee (Scheme 73).86 The use of coordinating solvents like THF and dioxane dramatically decreased the conversion by deactivating the Ir catalyst while the additive acetate ion plays a crucial role in improving the enantioselectivity.

Scheme 73. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Unfunctionalized Exocyclic Alkenes.

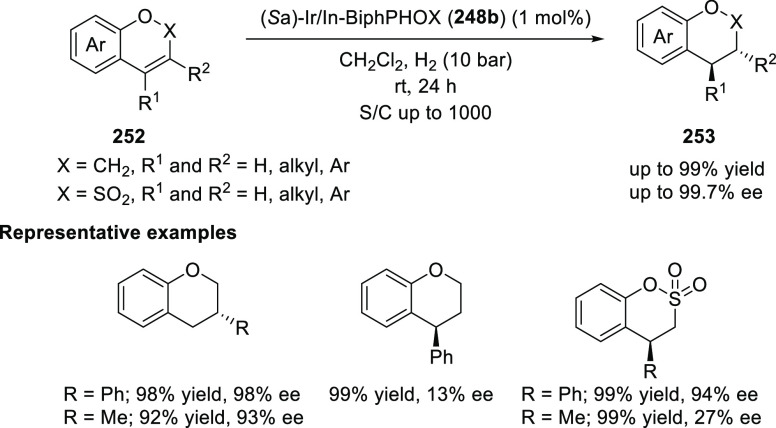

Afterward, Zhang reported the asymmetric hydrogenation of substituted 2H-chromenes and substituted benzo[e][1,2]oxathiine 2,2-dioxides (252) (Scheme 74).87 A variety of 2H-chromenes possessing 3-aryl/alkyl substituents were hydrogenated to the corresponding chiral 3-substituted chromanes (253) in high yields (92–99%) with excellent enantioselectivities (>99% ee). The 4-phenyl substituent on 2H-chromenes also gave the corresponding product in excellent yield but with poor enantioselectivity. Interestingly, benzo[e][1,2]oxathiine 2,2-dioxides with phenyl and methyl substituents produced the desired products in excellent yields but with contrasting enantioselectivity for phenyl (94% ee) and methyl substituents (27% ee).

Scheme 74. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Substituted 2H-Chromenes and Benzo[e][1,2]oxathiine 2,2-Dioxides.

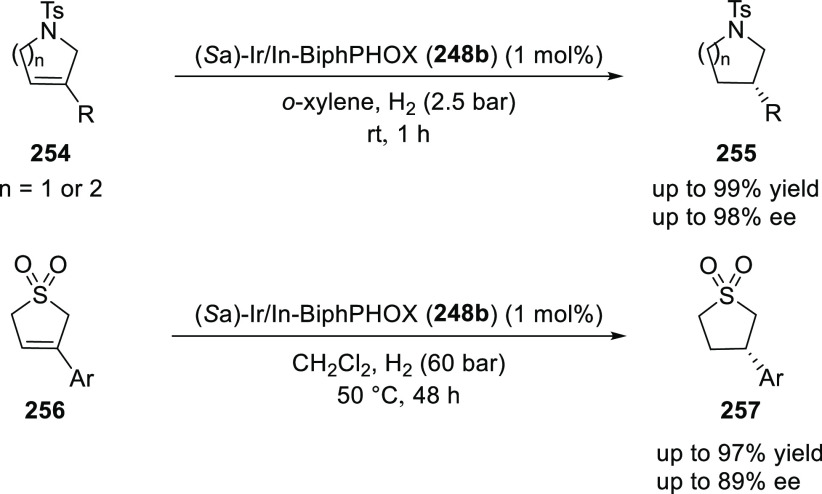

Similarly, Zhang extended their catalytic system for the asymmetric hydrogenation of 3-substituted 2,5-dihydropyrroles (254) and 3-substituted 2,5-dihydrothiophene 1,1-dioxides (256) (Scheme 75).88 The hydrogenation of 3-substituted 2,5-dihydrothiophene 1,1-dioxides was more challenging compared to the 3-substituted 2,5-dihydropyrroles and hence, a higher temperature and hydrogen pressure were required to achieve full conversions.

Scheme 75. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of 3-Substituted 2,5-Dihydropyrroles and 2,5-Dihydrothiophene 1,1-Dioxides.

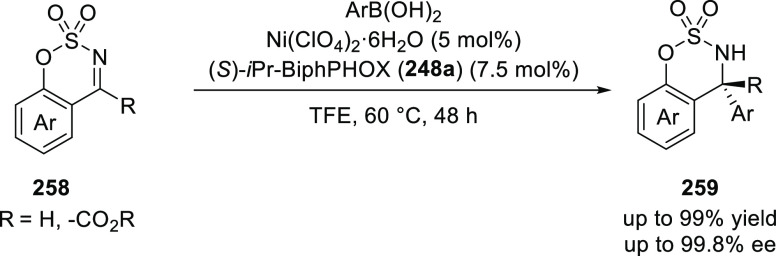

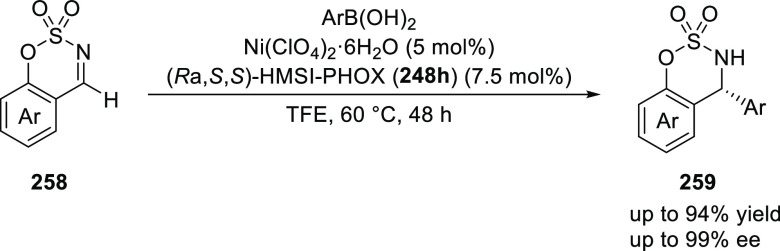

Later on, Zhang employed iPr-BiphPHOX (248a) in a Ni(II)-catalyzed asymmetric addition of arylboronic acids to cyclic aldimines and ketimines (258) furnishing products with excellent yields (up to 99%) and enantioselectivities (>99% ee) (Scheme 76).89 Ligand iPr-BiphPHOX (248a) coordinates with Ni(II) to form a complex with (S)-axial chirality, while the complex with (R)-axial chirality was disfavored because of the steric hindrance of the iPr group and the anion coordinated to Ni(II). Crystallographic studies confirmed the (S)-configuration and tetrahedral geometry of the Ni(II) complex. Interestingly, DFT calculations suggested that in solution the configuration of the Ni(II) complex changes from tetrahedral to planar.

Scheme 76. Asymmetric Arylation of Cyclic Aldimines and Ketimines.

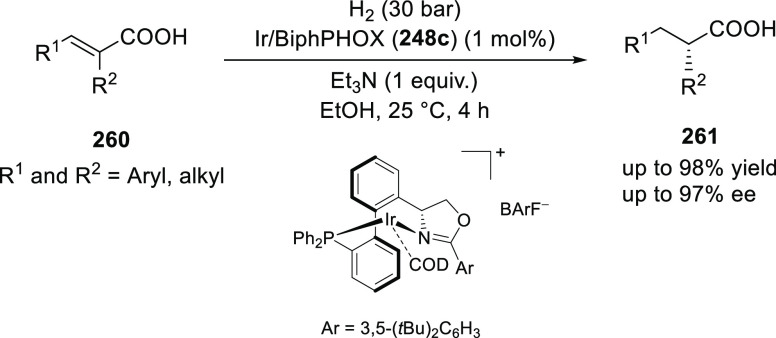

Ligand 248c is architecturally very similar to BiphPHOX (248a–b) and it has been applied in the asymmetric hydrogenation of unsaturated acids.

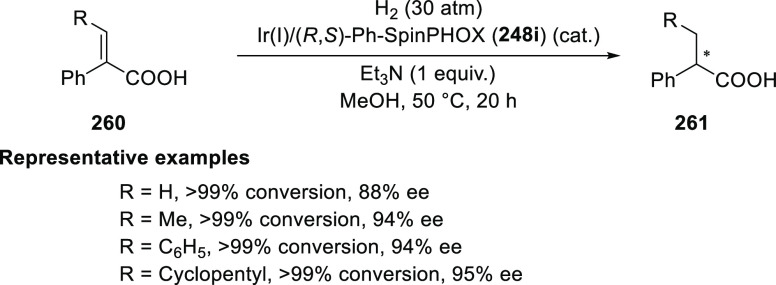

In 2017, Zhang developed a series of highly modular phosphinooxazoline ligands from readily available (S)-(+)-2-phenylglycinol. These ligands were utilized in the Ir-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acids (260) to provide chiral α-substituted carboxylic acids (261) (up to 97% ee, 98% yield, 2000 TON) (Scheme 77).90 Ligand 248c possessing a 3,5-(tBu)2C6H3 substituent on the oxazoline was found to be optimal. Changing the 3,5-(tBu)2C6H3 substituent to a phenyl or a tBu drastically reduced the reactivity and enantioselectivity in hydrogenation. The role of Et3N as an additive was crucial as the reactivity dropped dramatically without it.

Scheme 77. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of α,β-Unsaturated Acids.

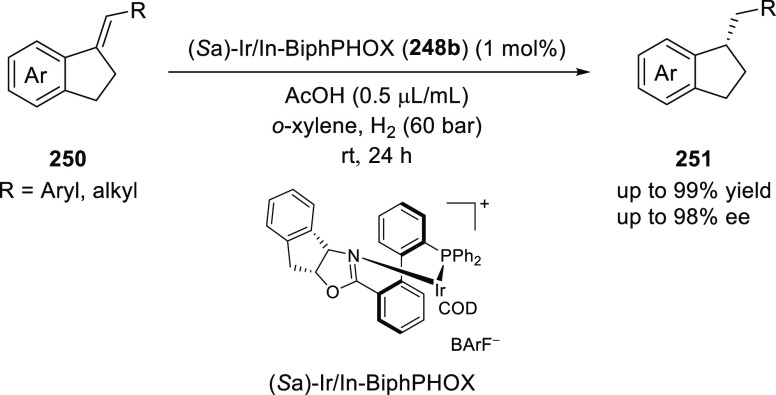

2.1.2.2. SIPHOX Ligands

SIPHOX ligands (248d–g) have been employed in the Ir-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of olefins, Pd-catalyzed Narasaka-Heck cyclization, Pd-catalyzed enantioselective formal [6 + 4] cycloaddition of vinyl oxetanes with azadienes and Ni-catalyzed enantioselective arylation of cyclic N-sulfonyl imines.

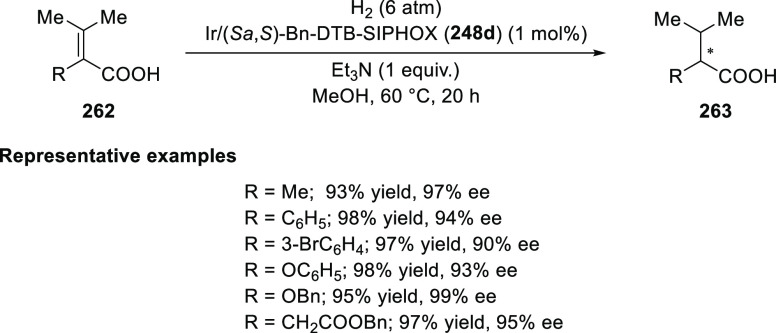

Zhou reported the asymmetric hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated carboxylic acids (262) possessing tetra-substituted olefins using Ir and chiral P,N-ligands (248d) based on the spiro-backbone (Scheme 78).91 This method offers a direct approach to chiral carboxylic acids possessing an α-stereocenter having aryl, alkyl, aryloxy, and alkyloxy substituents. The substituents on both phosphorus (3,5-di-t-butylphenyl) and the oxazoline ring of 248d had a strong effect on the outcome of the reaction. A chiral induction model was proposed which showed that the (R)-aryloxy or (R)-alkyloxy-β,β-dimethyl acrylic acids 262 prefer to coordinate to catalyst (Sa,S)-248d with Re-facial selectivity and consequently generates products 263 preferably with (S)-configuration.

Scheme 78. Asymmetric Hydrogenation Reaction of α,β-Unsaturated Carboxylic Acids.

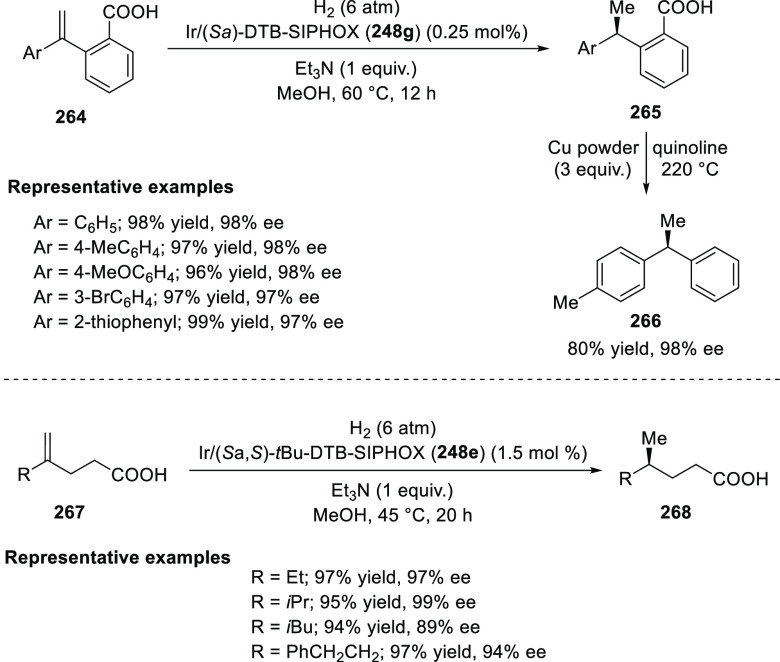

In 2013, Zhou extended the Ir-catalyzed enantioselective hydrogenation strategy to 1,1-diarylethenes (264) and 1,1-dialkylethenes (267) by using a carboxylic acid as a directing group (Scheme 79).92 The carboxylic acid group is essential for the success of this method as no reaction was observed without it or with the corresponding ester. The diphenylethene substrates having a carboxylic acid group either at the meta- or para-position could not be hydrogenated under these reaction conditions. Importantly, no reaction occurred in the absence of the base triethylamine. These experiments revealed that the carboxylic acid reacts with a base and acts as an anchor by coordinating with the Ir catalyst. This enables the catalyst to discriminate between the prochiral faces of the substrates and catalyze their hydrogenation with high levels of enantioselectivity.

Scheme 79. Enantioselective Hydrogenation.

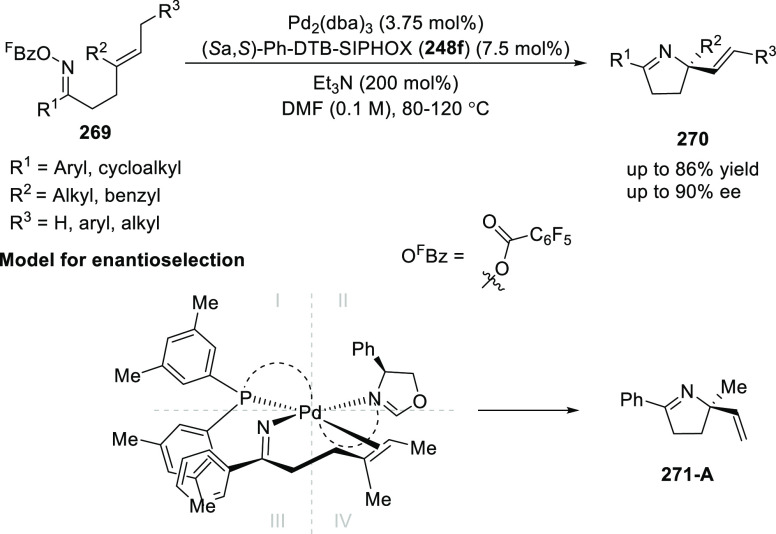

In 2017, Bower developed a Pd-catalyzed highly enantioselective Narasaka-Heck cyclization starting from oxime esters with tethered trisubstituted alkenes (269) using Spinol-derived chiral ligands 248f (Scheme 80).93 This method provides access to dihydropyrrole derivatives (270) with a nitrogen-containing stereocenter in up to 86% yield and 90% ee. It is important to note that the alkene geometry is criticial for reaction success, as cyclization with the (Z)-isomer proceeds with considerably lower ees and yields compared to the corresponding (E)-isomer. Additionally, alkenes with 1,2-disubstitution resulted in a mixture of dihydropyrrole and pyrrole products due to competing β-hydride elimination. The proposed reaction mechanism suggested the enantioselective migratory insertion of alkenes into Pd–N bond was the key step.

Scheme 80. Enantioselective Narasaka–Heck Cyclization.

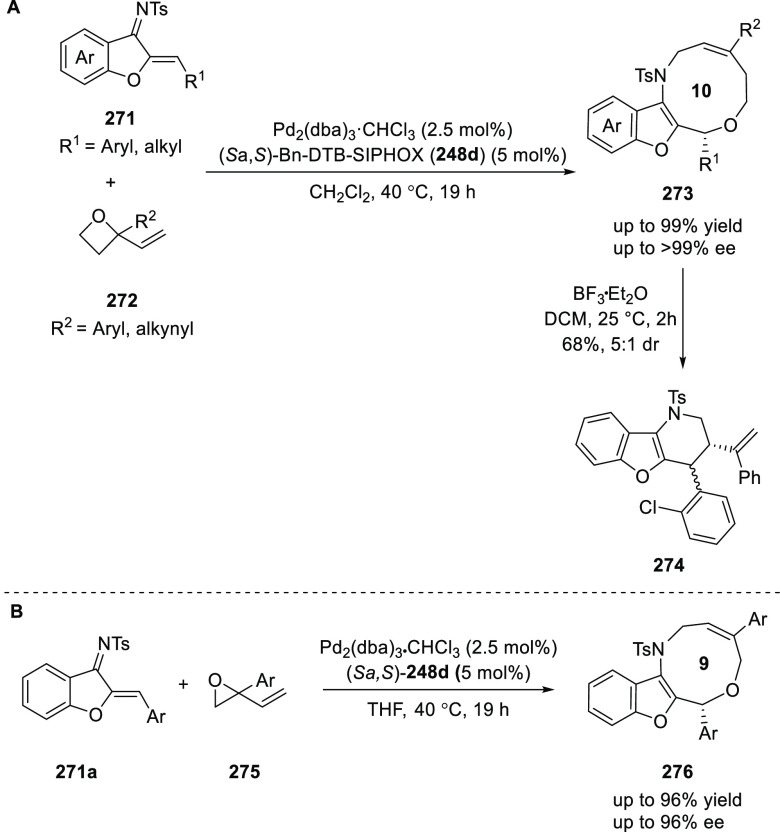

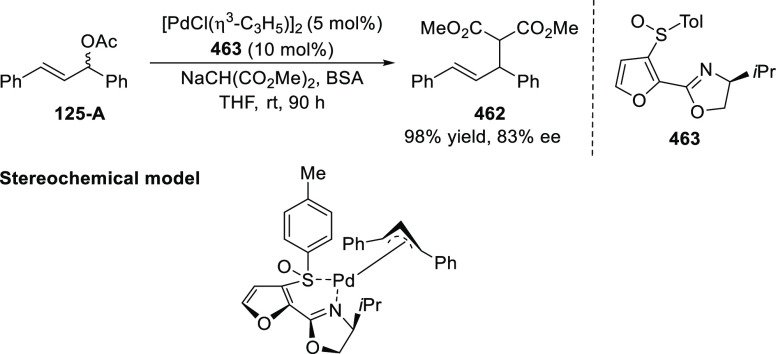

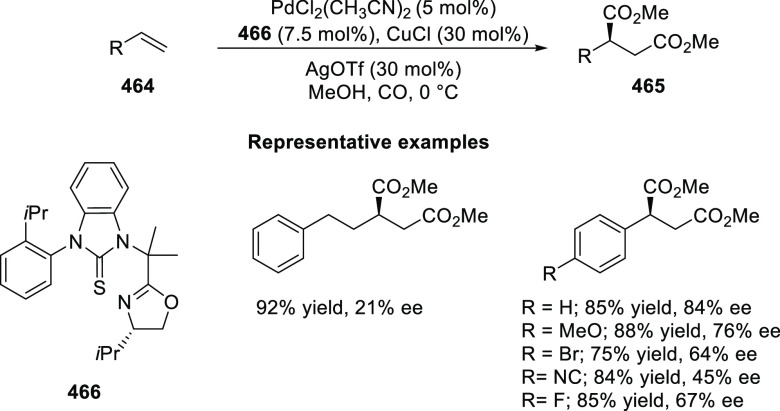

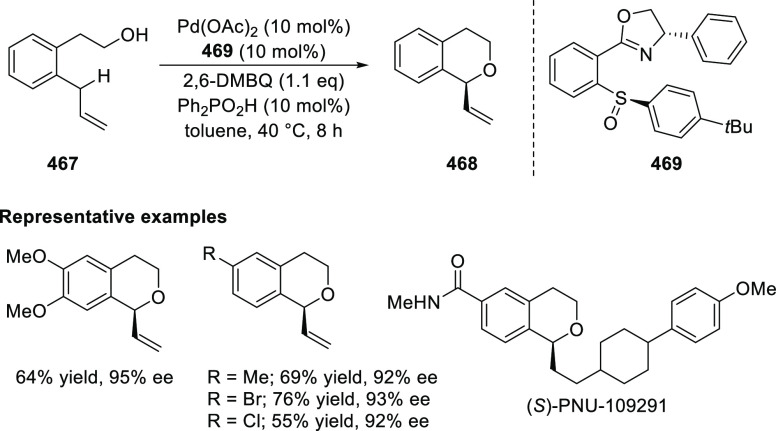

Zhao reported a highly enantioselective synthesis of benzofuran/indole-fused ten-membered heterocycles (273) via a formal [6 + 4] cycloaddition of vinyl oxetanes (272) with azadienes (271) (Scheme 81A).94 A wide range of benzofuran- and indole-fused heterocycles were accessed in excellent yields and enantioselectivities. The use of aryl- and alkynyl-substituted vinyl oxetanes as substrates was successful whereas an alkyl-substituted vinyl oxetane failed to furnish the desired product, possibly due to the difficulty in the formation of the Pd-π-allyl intermediate. Furthermore, a unique fragmentation of these ten-membered heterocycles (273) was achieved under Lewis acid catalysis to furnish a thermodynamically more favorable six-membered ring (274). Additionally, this method was also employed to generate nine-membered heterocycles (276) by reacting azadiene (271a) with vinyl epoxide (275) via a formal [5 + 4] cycloaddition reaction (Scheme 81B).

Scheme 81. Enantioselective Formal [6 + 4] Cycloaddition of Vinyl Oxetanes with Azadienes.

Lin reported a Ni-catalyzed enantioselective arylation of cyclic N-sulfonyl imines (258) with arylboronic acids (Scheme 82).95 A newly developed chiral phosphinooxazoline ligand, (Ra,S,S)-248h, based on the hexamethyl-1,1′-spirobiindane backbone (HMSI-PHOX), which is a derivative of SIPHOX, provided optically active amines in high yields (up to 94%) and enantioselectivities (up to 99% ee).

Scheme 82. Enantioselective Arylation of Cyclic N-Sulfonyl Imines.

2.1.2.3. SpinPHOX Ligands

SpinPHOX ligands (248i–k) have been employed in the Ir-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of α-aryl-β-substituted acrylic acids, exocyclic α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds, and 3-ylidenephthalides.

Ding reported the enantioselective hydrogenation of a series of α-aryl-β-substituted acrylic acids (260) by using an Ir-(R,S)-SpinPHOX (248i) based catalytic system (Scheme 83).96 A series of biologically interesting α-aryl acetic acids (261) were synthesized in excellent yields and enantioselectivity (up to 96% ee). The addition of triethylamine as a basic additive was essential for both conversion and enantioselectivity due to the poor solubility and potential impact of the carboxylate group on the catalysis. Additionally, hydrogenation of the (Z)-isomer with (R,S)-SpinPHOX (248i) was not as successful as the conversion to products was too low. It was found that the chirality at the spiro backbone of (R,S)-SpinPHOX (248i) had a significant impact on the asymmetric induction of the reaction. The (R)-configuration in the spiro backbone and an (S)-configuration on the oxazoline component was found to be the matched ligand whereas the corresponding diastereomeric ligand (S,S)-SpinPHOX gave lower conversion and enantioselectivity for the opposite enantiomer.

Scheme 83. Enantioselective Hydrogenation α-Aryl-β-Substituted Acrylic Acids.

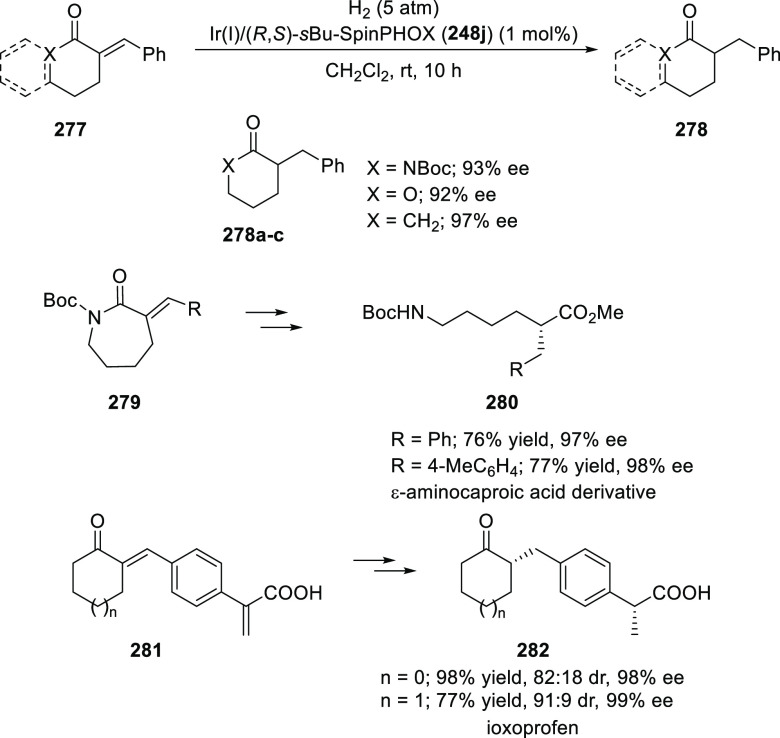

The Ir/SpinPHOX (248j) catalytic system was extended to the enantioselective hydrogenation of six- and seven-membered exocyclic α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds (277) with a focus on the challenging lactam derivatives (Scheme 84).97 A series of optically active carbonyl compounds (278) such as lactams, lactones and cyclic ketones with an α-chiral carbon stereocenter was prepared in excellent enantiomeric excess (up to 97%). An excellent stereoselectivity was observed when either (R,S)-248j or (S,S)-248j were employed in the reaction and opposite enantiomers were formed preferentially, which indicated that the spiro chirality of the ligand primarily controls the sense of asymmetric induction while the chirality of the oxazoline moiety might have some influence on the level of enantioselectivity. Additionally, the application of this methodology was shown by synthesizing an ε-aminocaproic acid derivative (280) and the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug loxoprofen (282).

Scheme 84. Enantioselective Hydrogenation of Exocyclic α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyl Compounds.

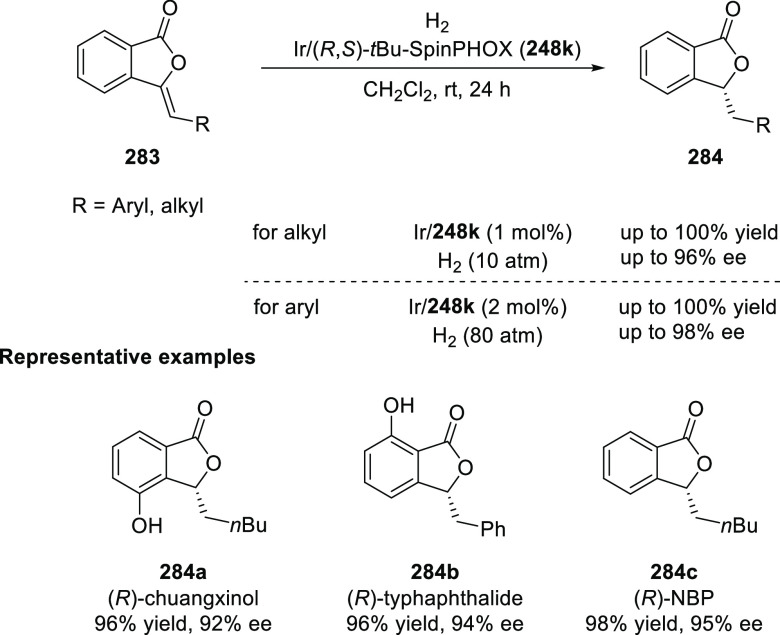

In 2018, Ding reported the enantioselective hydrogenation of 3-ylidenephthalides (283) by using an Ir/SpinPHOX (248k) catalyst (Scheme 85).98 This method provides a straightforward approach to a wide variety of 2-substituted chiral phthalides (284) in high yields with excellent enantioselectivities (up to >99% yield and 98% ee). The application of this methodology was demonstrated in the synthesis of chiral drugs and natural products such as (R)-chuangxinol (284a), (R)-typhaphthalide (284b), and (S)-3-n-butylphthalide (NBP) (284c), a constituent of celery seed oil.

Scheme 85. Enantioselective Hydrogenation of 3-Ylidenephthalides.

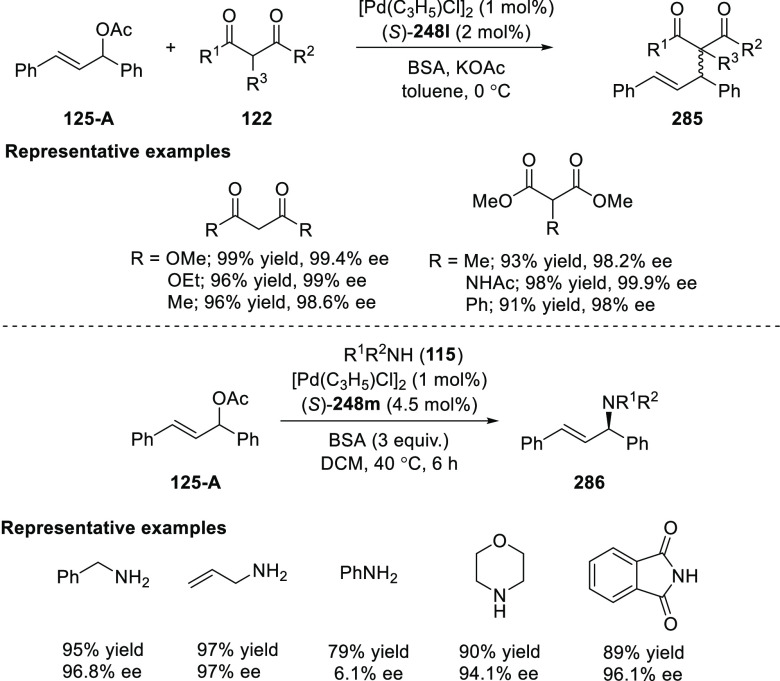

In 2018, Teng reported a new rigid phosphinooxazoline ligand (248l,m) possessing a chiral spiro core and it was applied in Pd-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation and amination with ees up to 99% (Scheme 86).99,100

Scheme 86. Pd-Catalyzed Asymmetric Allylic Alkylation and Amination.

To conclude this section, metal-complexes of PHOX ligands with Stereoaxis or Stereocenter (248a–m) have been employed in various asymmetric transformations. Iridium complexes were successful in the hydrogenation of a variety of alkenes whereas nickel complexes were excellent when used in the addition of aryl boronic acids to imines. Palladium complexes found their application in (I) Narasaka-Heck cyclization, (II) [6 + 4] cycloadditions of vinyl oxetanes with azadienes, and (III) allylic alkylation and amination.

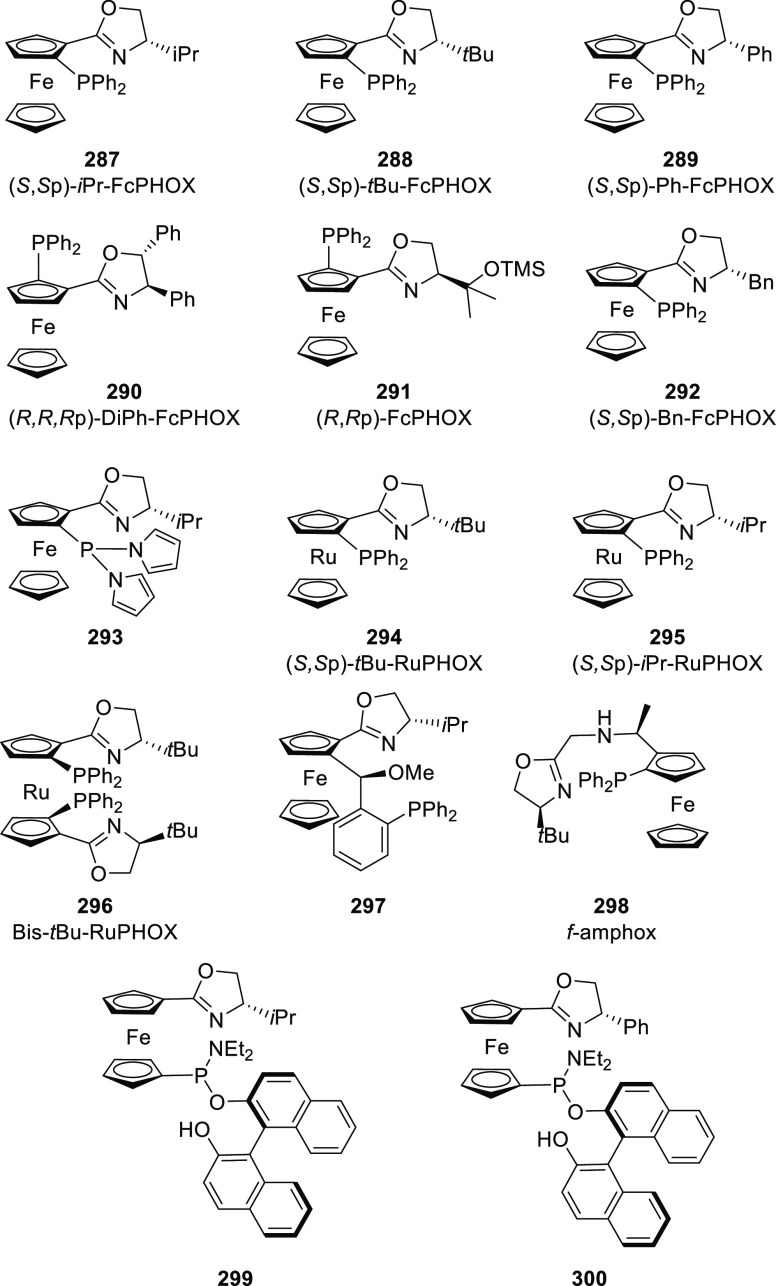

2.1.3. Phosphinooxazoline Ligands with a Stereoplane

Ferrocene phosphinooxazoline (FcPHOX) ligand (other acronyms include FOXAP, Phosferrox, FOX) is the major contributor in this category of P,N-ligands (Figure 4). This ligand was first reported by Richards and Uemura in 1993 for Pd-catalyzed asymmetric allylic alkylation and since then has been employed in a myriad of metal-catalyzed asymmetric transformations.101

Figure 4.

FcPHOX ligands.

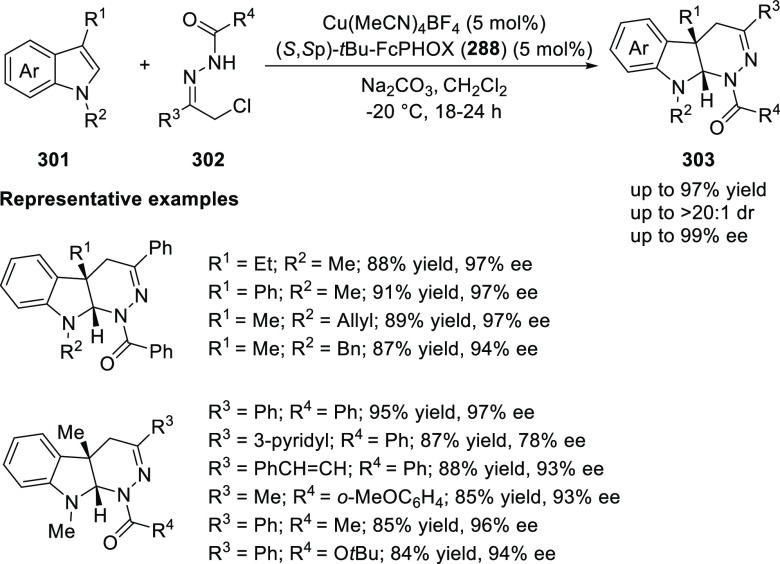

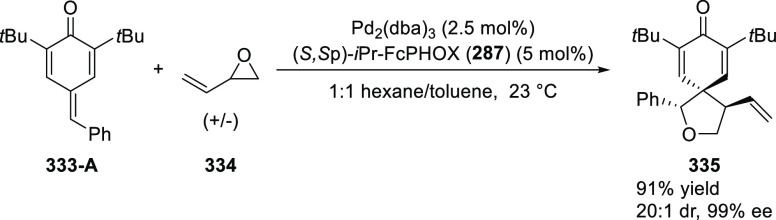

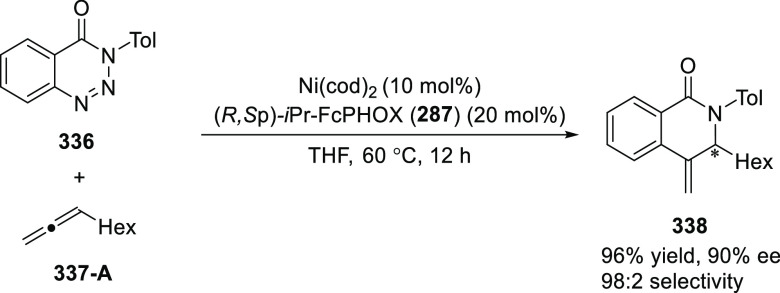

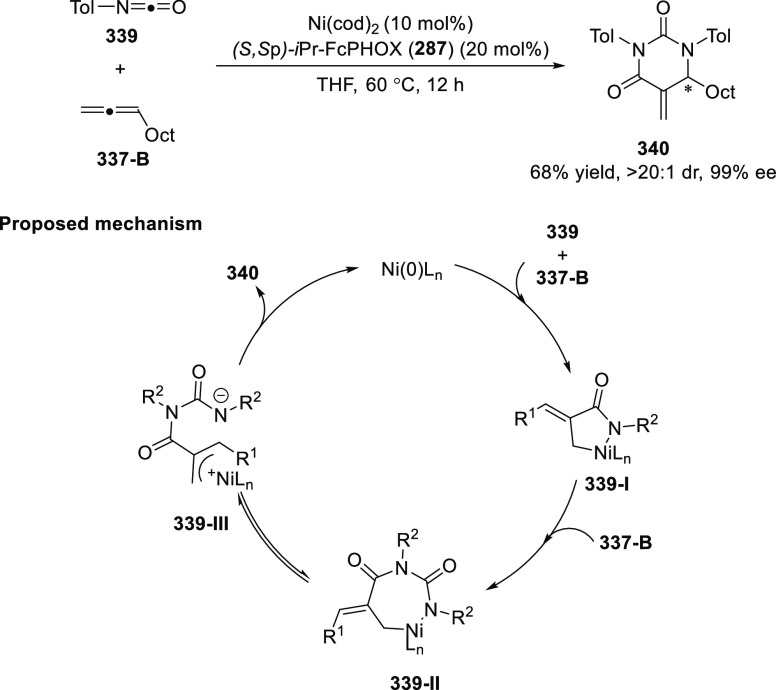

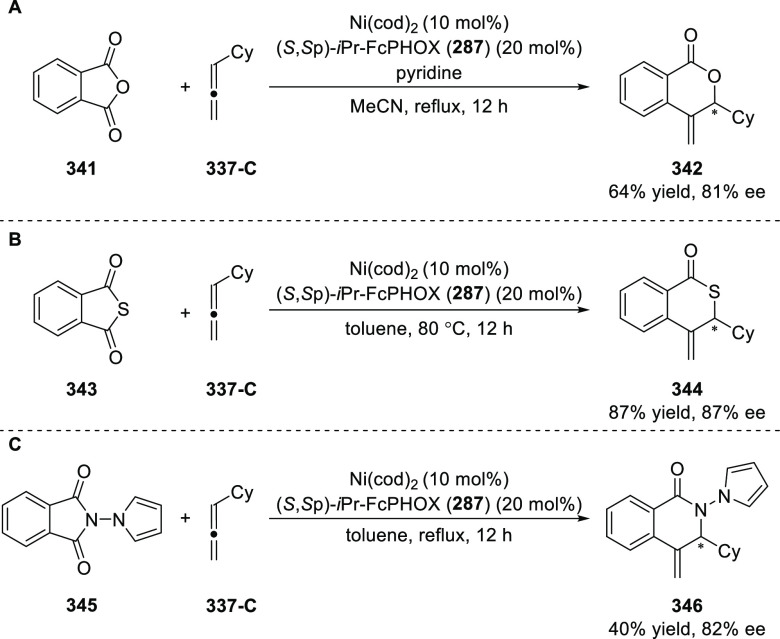

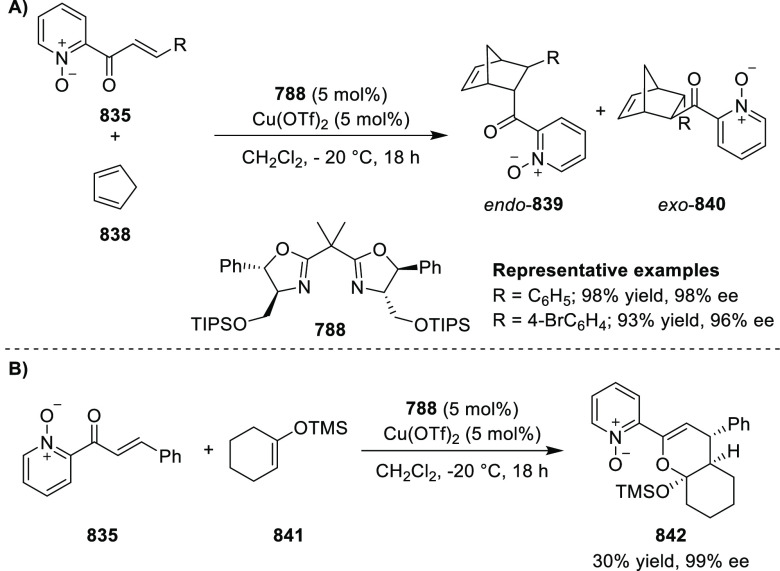

2.1.3.1. FcPHOX Ligands for Asymmetric Cycloaddition Reactions

In 2014, Wang developed a Cu/(S,Sp)-tBu-FcPHOX (288)-catalyzed asymmetric inverse-electron-demand aza-Diels–Alder reaction of indoles (301) with in situ formed azoalkenes (Scheme 87).102 This method provided access to a variety of biologically important [2,3]-fused indoline tetrahydropyridazine heterocycles (303) in good yields (up to 97%) with high regioselectivity and diastereoselectivity (>20:1 dr), and excellent enantioselectivity (up to 99% ee). The success of this reaction lies with the coordination of the chiral Cu/FcPHOX (288) complex to the in situ formed azoalkene.

Scheme 87. Asymmetric Inverse-Electron-Demand aza-Diels–Alder Reaction of Indoles.

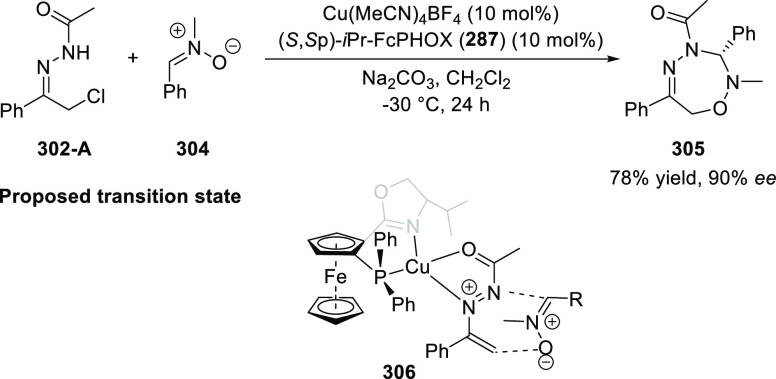

Later, Wang successfully employed azoalkenes in an unprecedented Cu/(S,Sp)-iPr-FcPHOX (287)-catalyzed asymmetric 1,3-dipolar [3 + 4] cycloaddition with nitrones (304) to generate rapid access to biologically important 1,2,4,5-oxatriazepanes (305) in excellent regioselectivity and enantioselectivity (Scheme 88).103 Interestingly, the [3 + 2] cycloadducts which could have potentially been formed were not observed. Alkyl-substituted nitrones resulted in only the racemic products and ortho-substituted aryl hydrazones and alkyl α-chloro-N-acyl hydrazone were not suitable substrates for this reaction. A proposed transition state 306 depicts that the in situ generated azoalkene coordinates with Cu through nitrogen and oxygen. The bulky isopropyl group of the oxazoline ring blocks the backside of the coordinated azoalkene, and hence the nitrone approaches the R group to avoid unfavorable steric congestion between the diphenylphosphine group in the chiral ligand and the R group of the nitrone.

Scheme 88. Asymmetric 1,3 Dipolar [3 + 4] Cycloaddition with Nitrones.

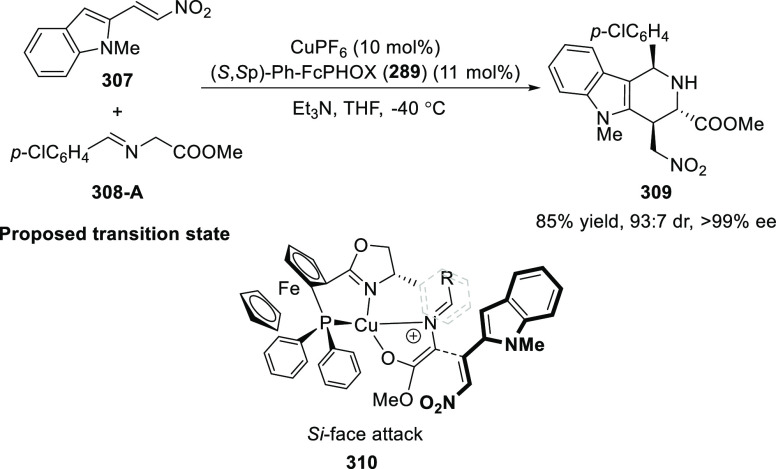

Deng reported the first Cu/(S,Sp)-Ph-FcPHOX (289)-catalyzed asymmetric [3 + 3] cycloaddition of azomethine ylides (308-A) with 2-indolylnitroethylenes (307) which afforded the highly substituted tetrahydro-γ-carboline derivatives (309) in moderate to high yields, and excellent levels of stereoselectivity (up to >98:2 dr, > 99% ee) (Scheme 89).104 This reaction is highly chemoselective toward the formation of the [3 + 3] cycloadduct over the [3 + 2] cycloadduct (up to 94:6 ratio). An alkyl-substituted azomethine ylide afforded the [3 + 2] cycloadduct in 87% yield instead of the expected [3 + 3] cycloadduct, presumably due to the less-reactive nature of the aliphatic imine. Because of the steric effects of the bulkier phenyl group in the oxazoline ring and the diphenylphosphine group of the ligand, the reaction is proposed to involve Si-face attack of nucleophilic complex 310, generated in situ from the chiral Cu/FcPHOX (289) and azomethine ylide (308-A).

Scheme 89. Asymmetric [3 + 3] Cycloaddition of Azomethine Ylides with 2-Indolylnitroethylenes.

During the Michael addition, the carbanion generated adjacent to the nitro group is stable enough at lower temperature and therefore suppresses the Mannich cyclization which gives the [3 + 2] cycloaddition product. Also, similar levels of stereoselectivity were observed for both the [3 + 3] and [3 + 2] cycloadducts suggesting that the Michael addition should be the crucial step for asymmetric induction.

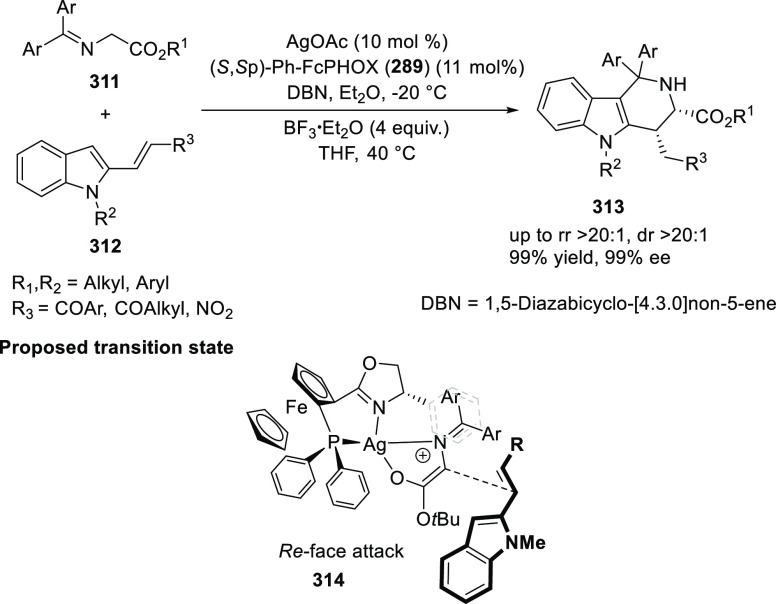

Following their earlier work, Deng described the first example of the Ag(I)/(S,Sp)-Ph-FcPHOX (289)-catalyzed regioselective and stereoselective [3 + 3] annulation of ketone-derived azomethine ylides (311) with 2-indolylethylenes (312) (Scheme 90).105 This tandem method involved a Michael addition followed by a BF3·Et2O-promoted Friedel–Crafts reaction. Like their earlier report, the traditional [3 + 2] cycloaddition was prevented by using sterically hindered ketone-derived azomethine ylides (>20:1 rr). A wide variety of highly substituted tetrahydro-γ-carboline derivatives (313) were obtained in high yields (up to 99%) with excellent stereoselectivities (up to >20:1 dr, up to 99% ee). Remarkably, the stereochemistry for the [3 + 3] annulation of the ketone-derived azomethine ylides was different from that of aldehyde-derived azomethine ylides although the same ligand Ph-FcPHOX (289) was used. This was due to the favored Re-face attack of the nucleophilic ketone-derived azomethine ylide to 2-indolylethylenes because of the steric effect generated by the two bulky phenyl groups in the nucleophile.

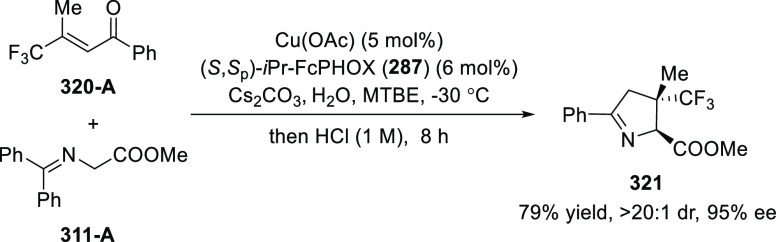

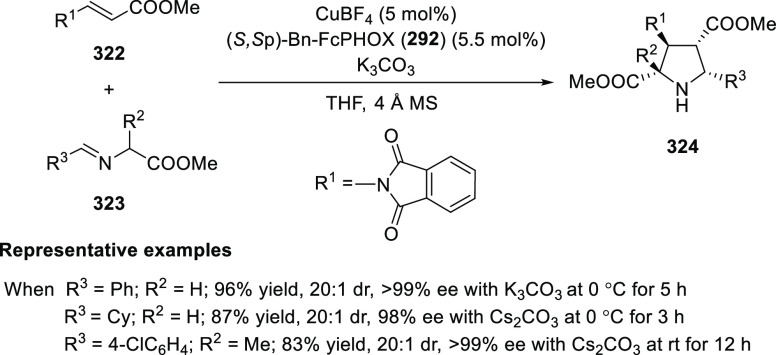

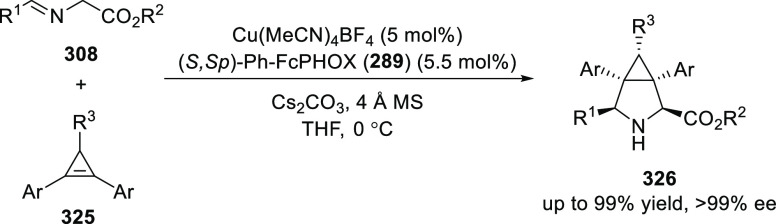

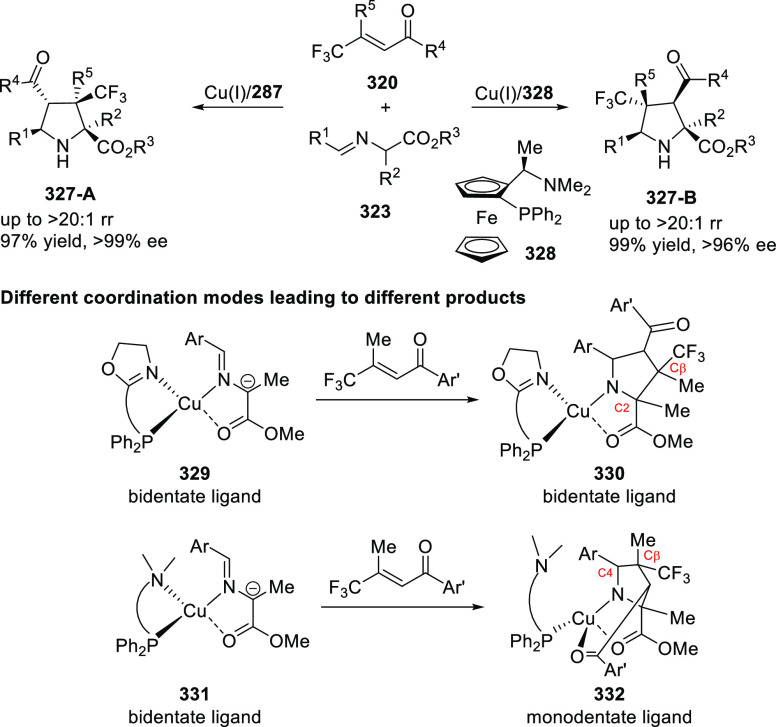

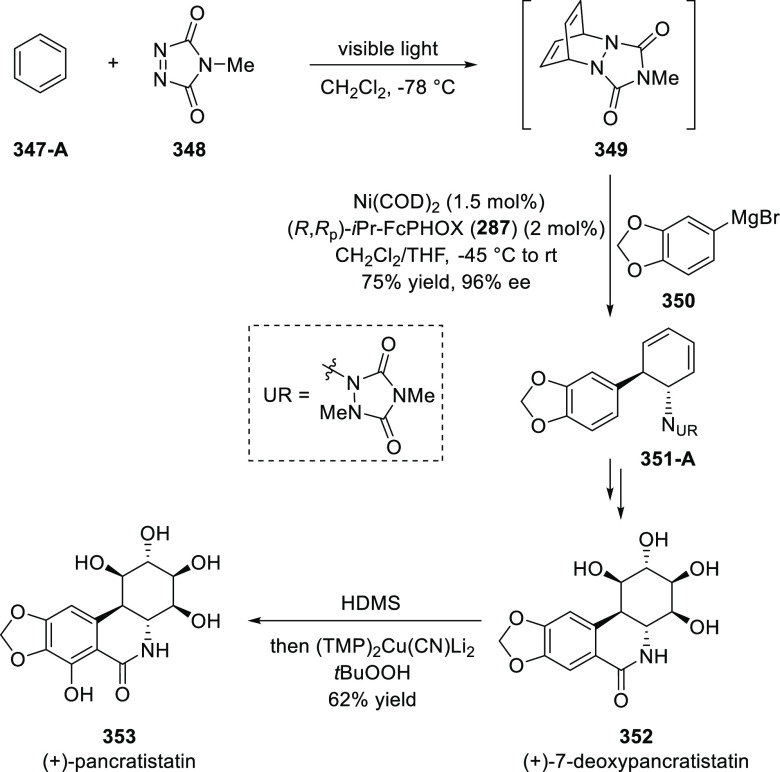

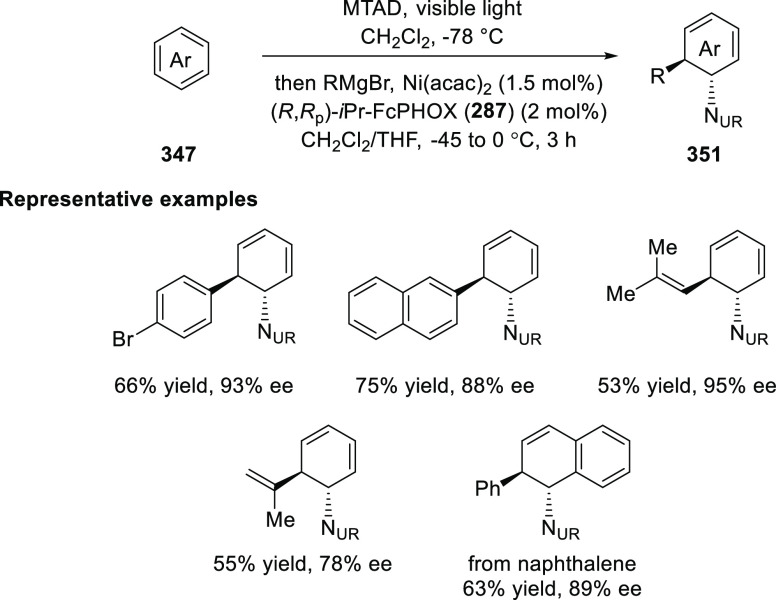

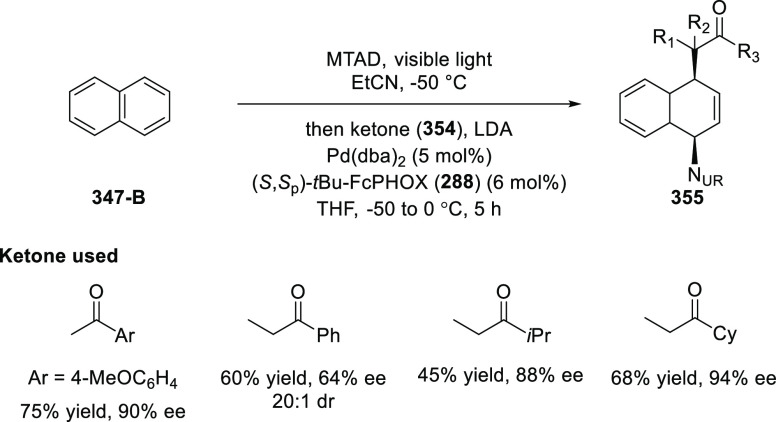

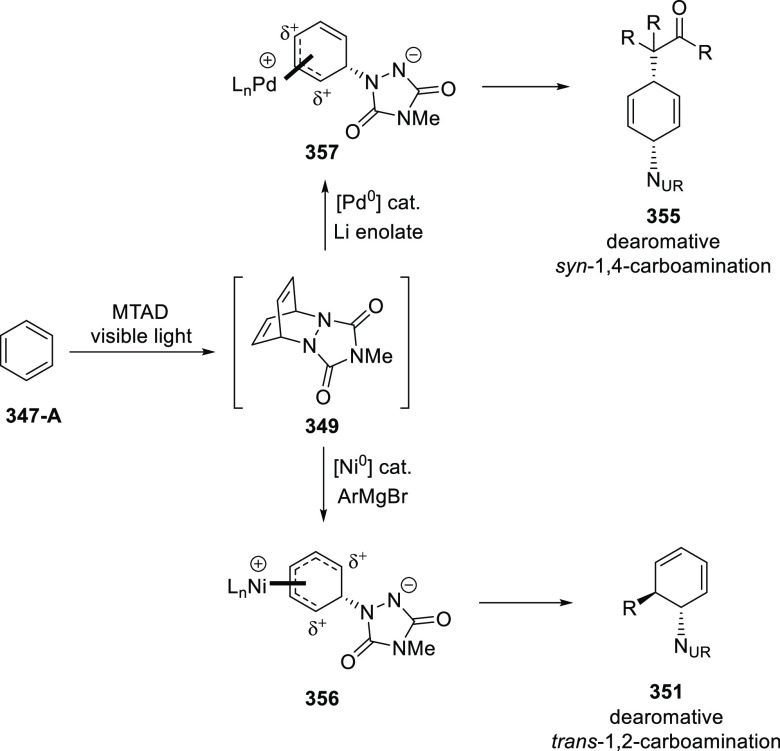

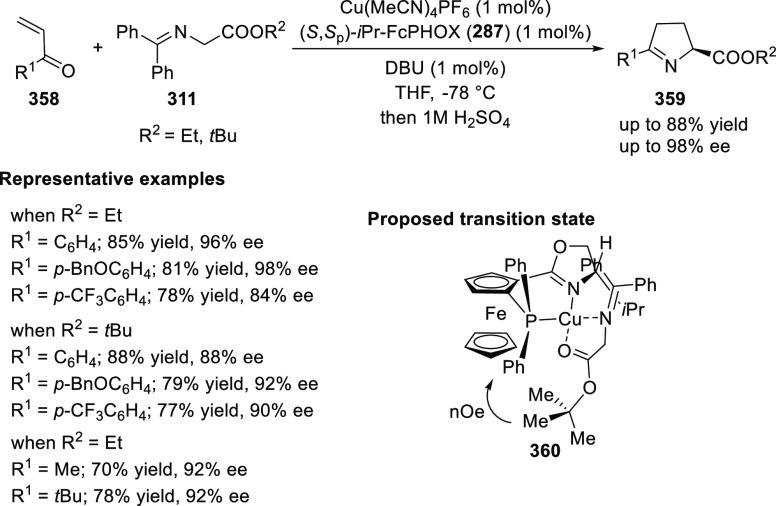

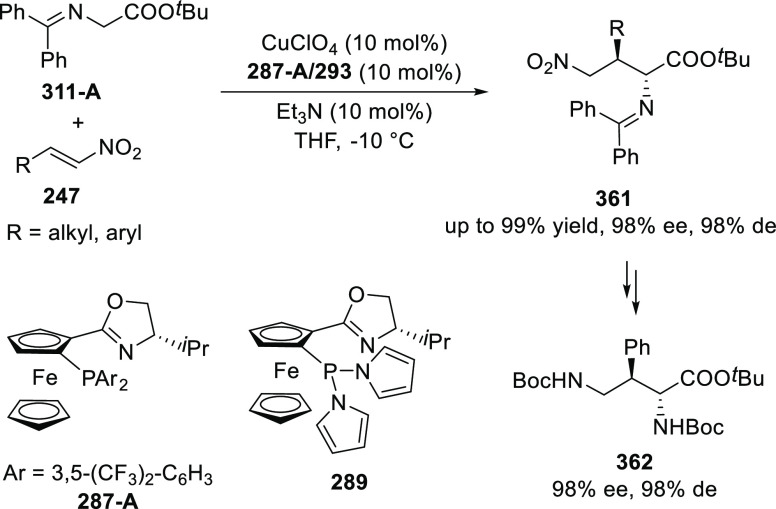

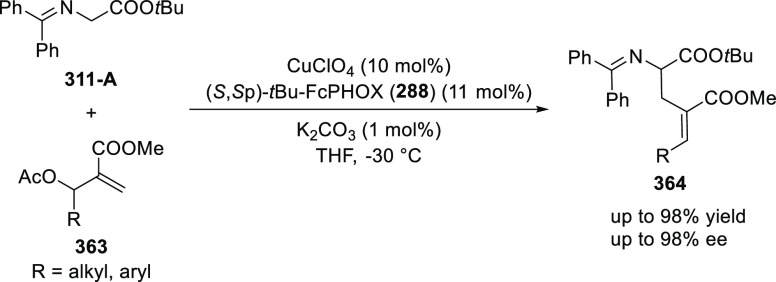

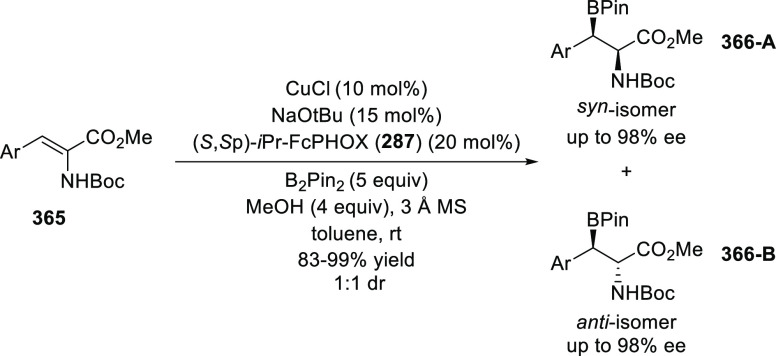

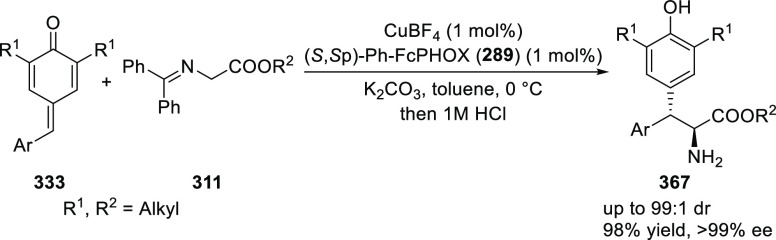

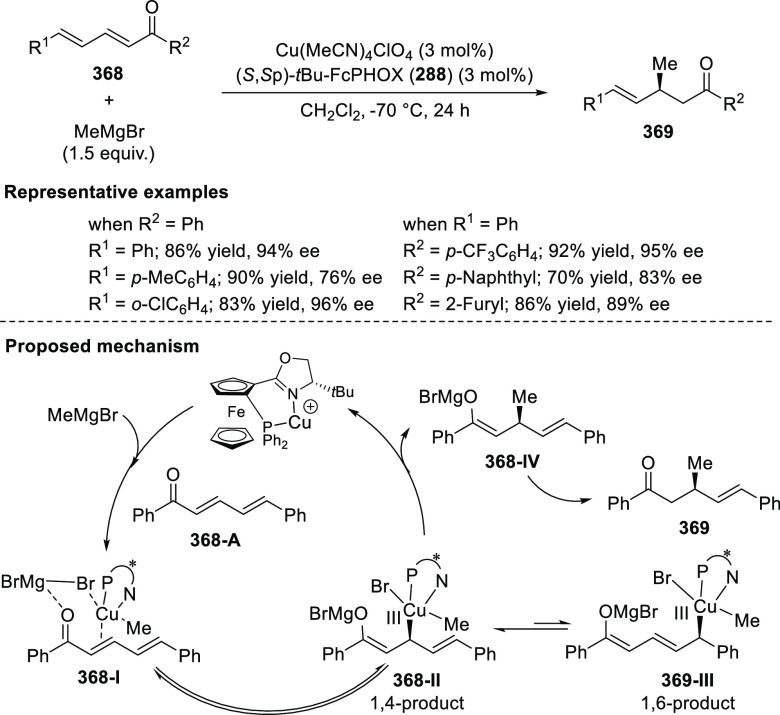

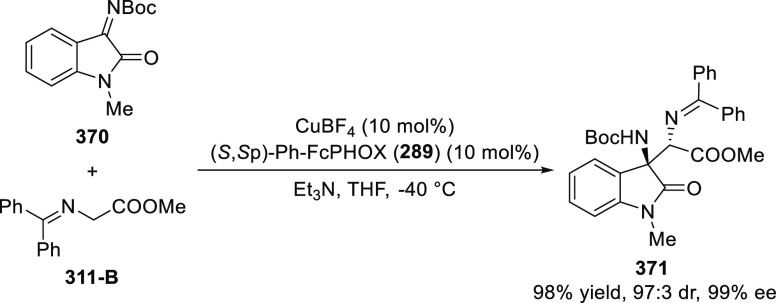

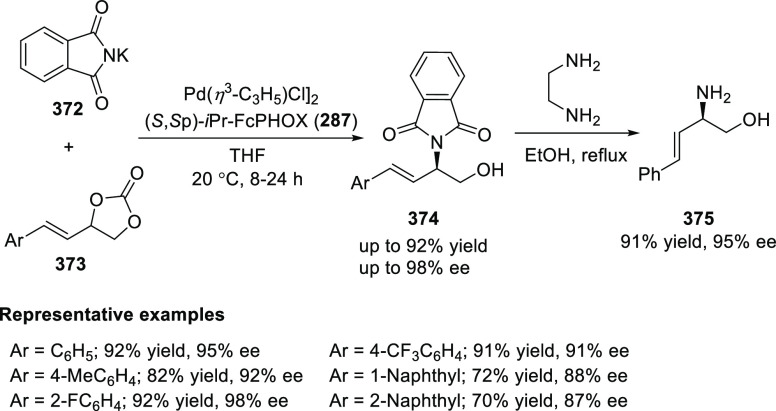

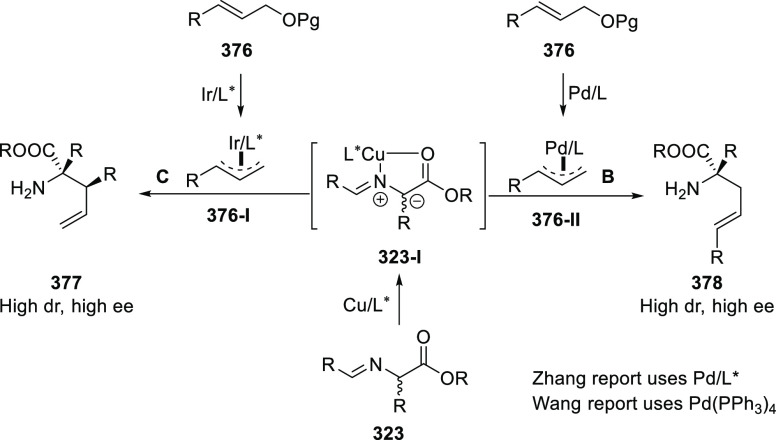

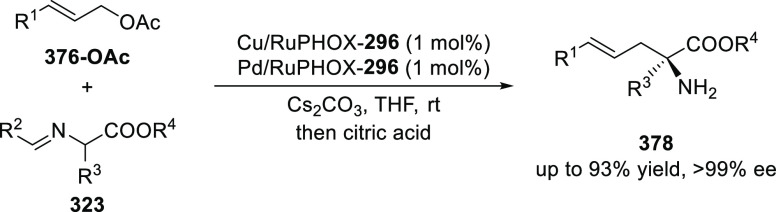

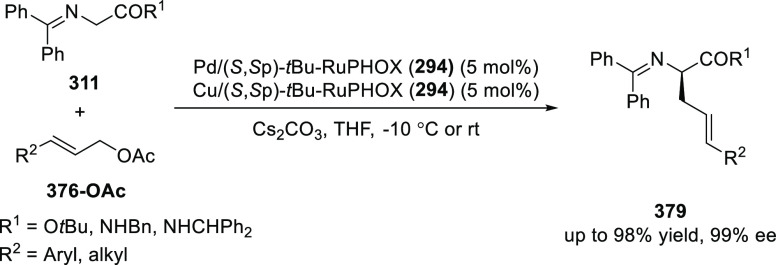

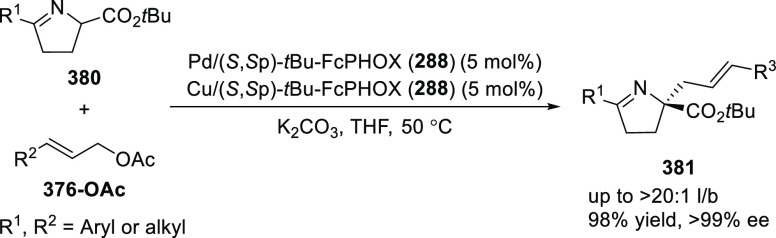

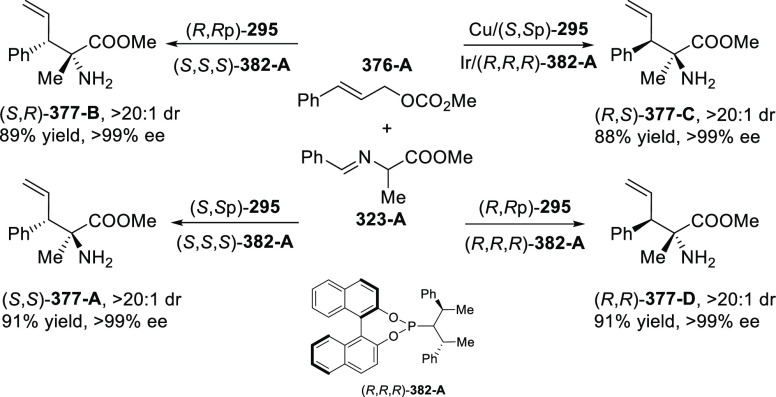

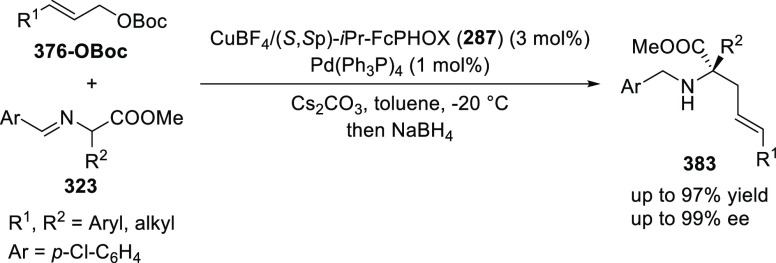

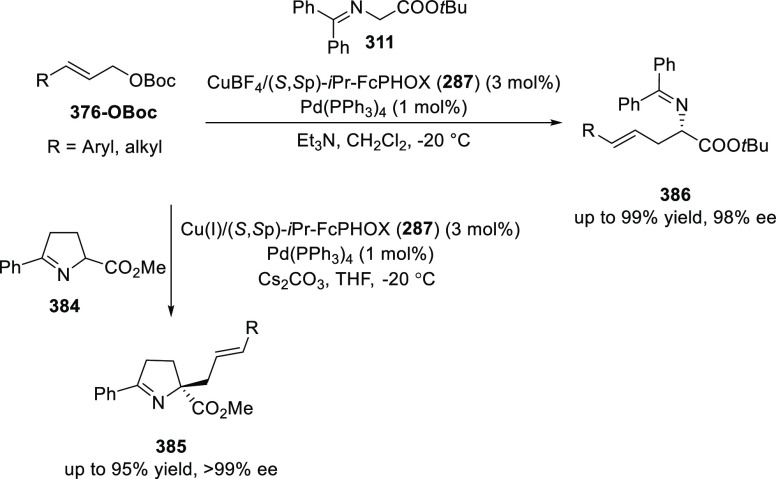

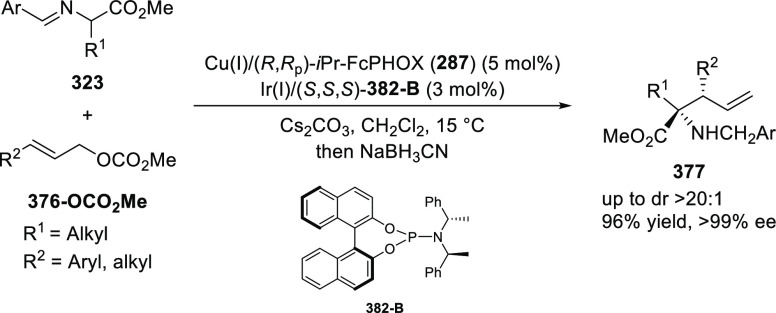

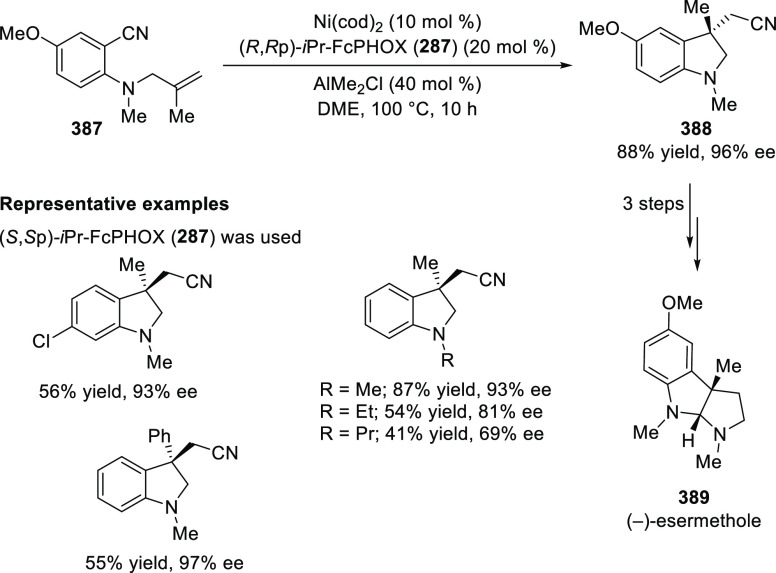

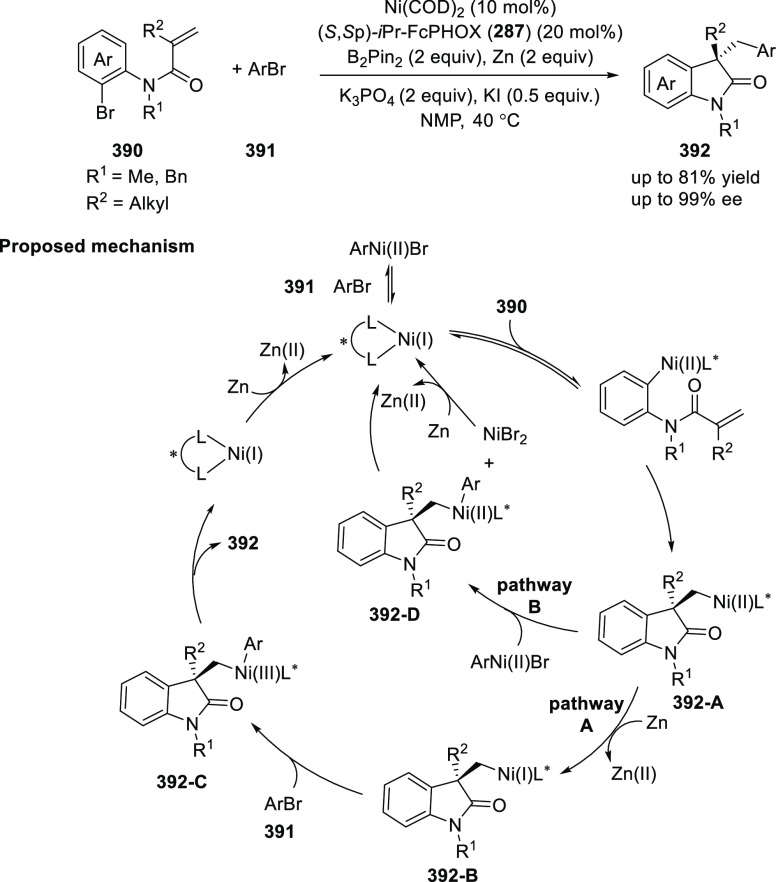

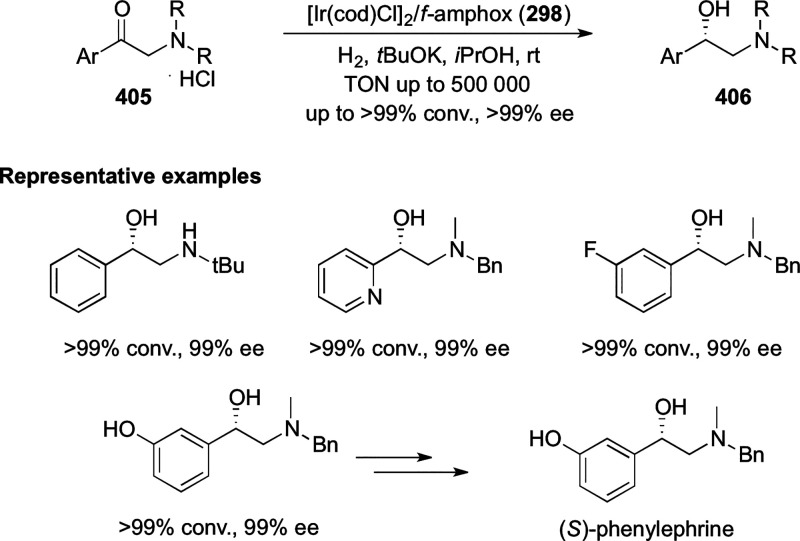

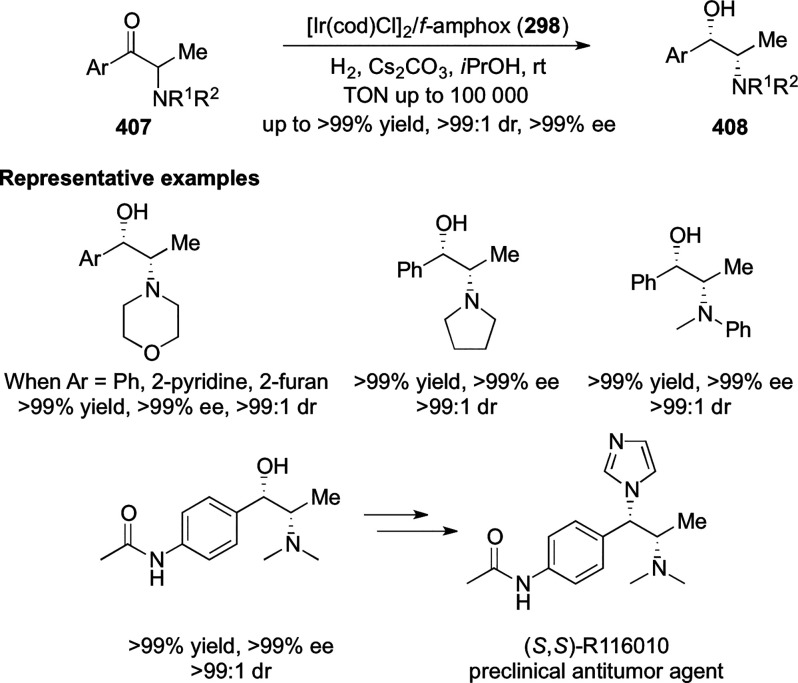

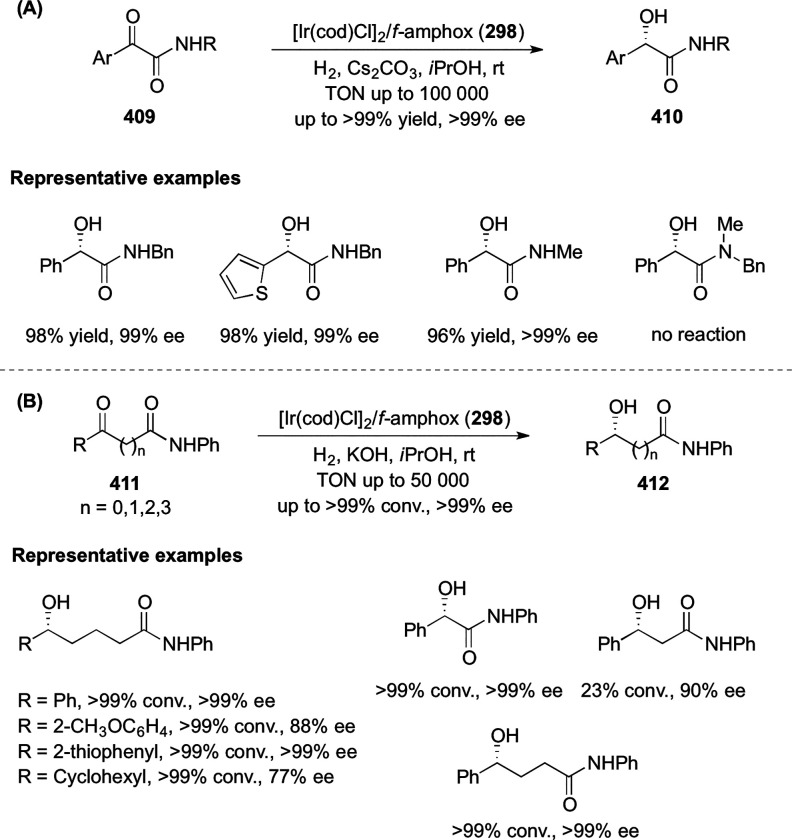

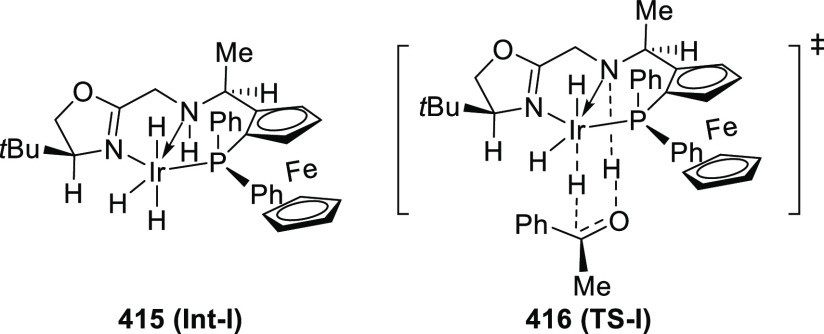

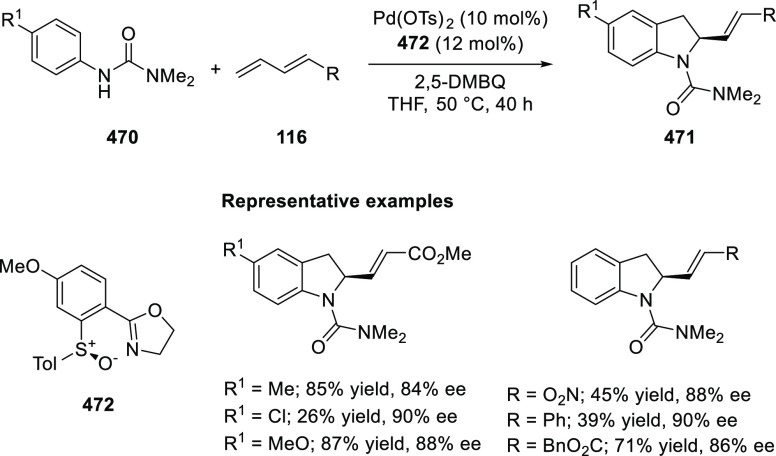

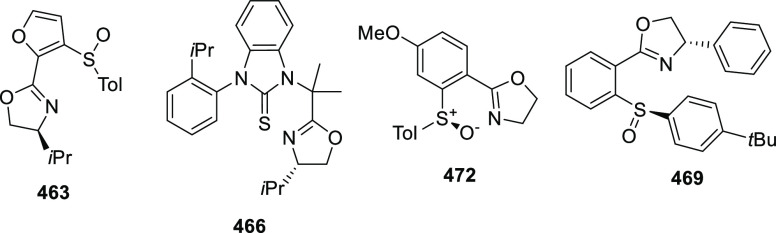

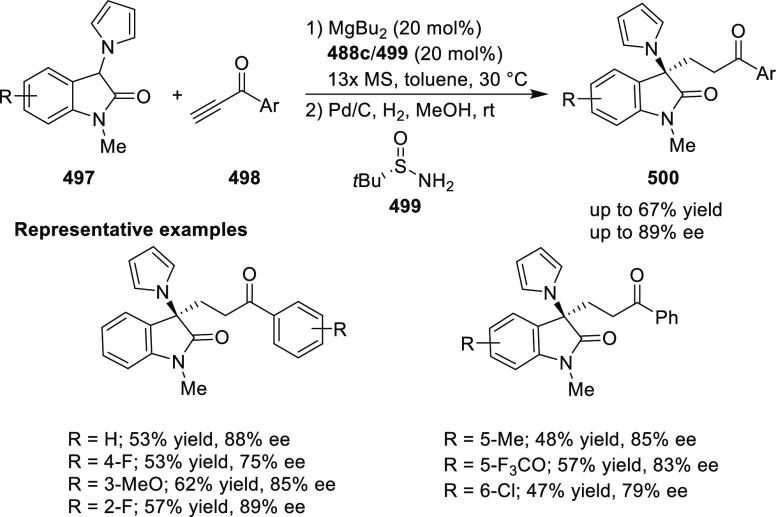

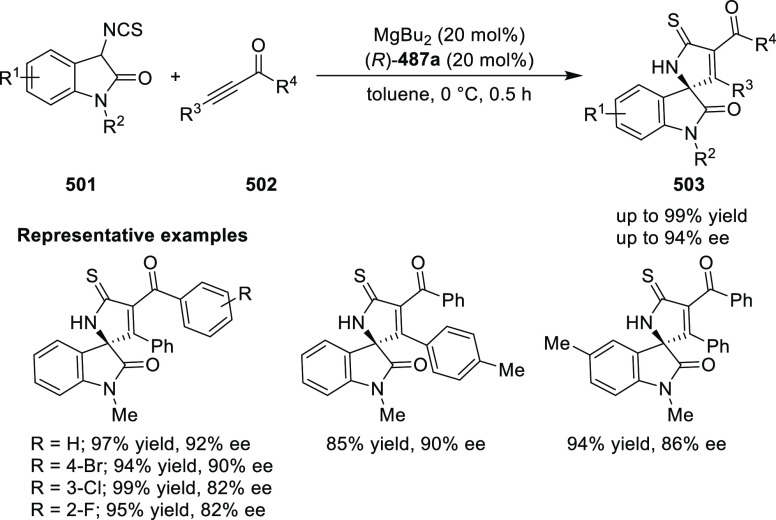

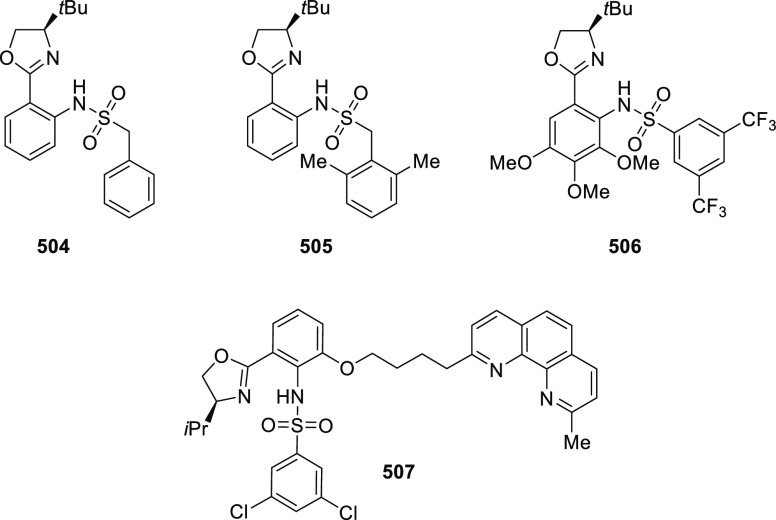

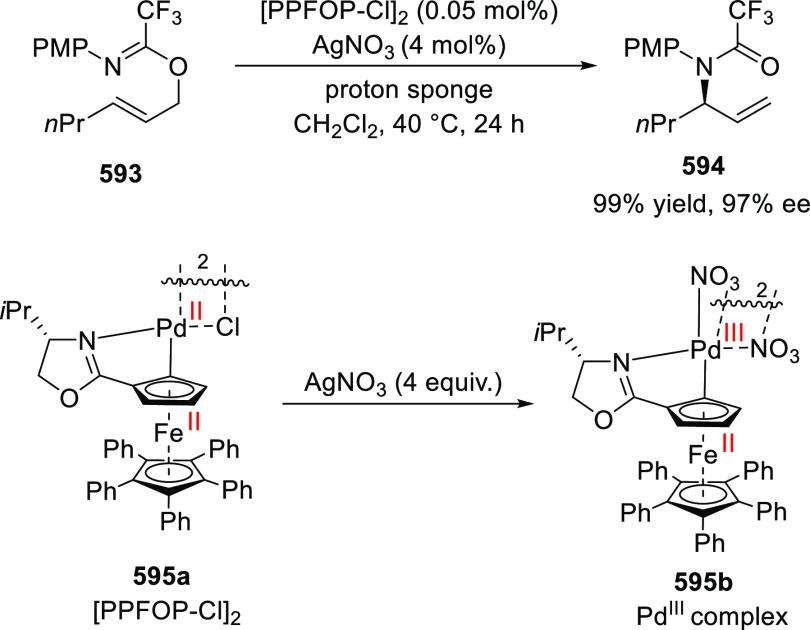

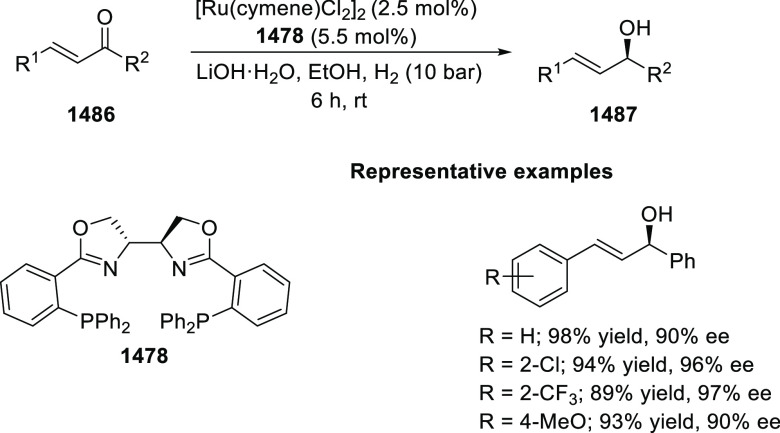

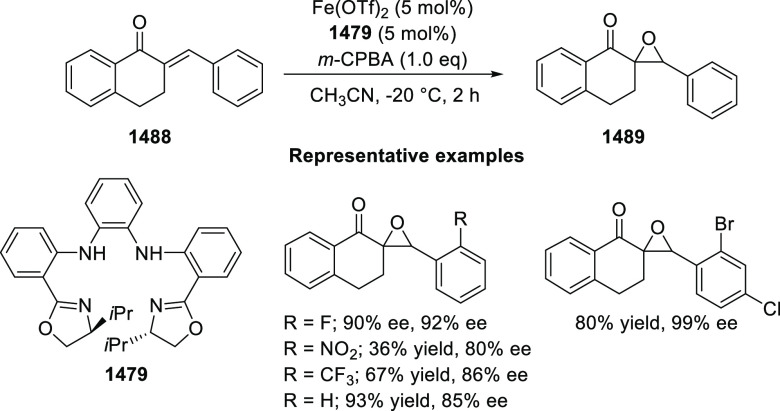

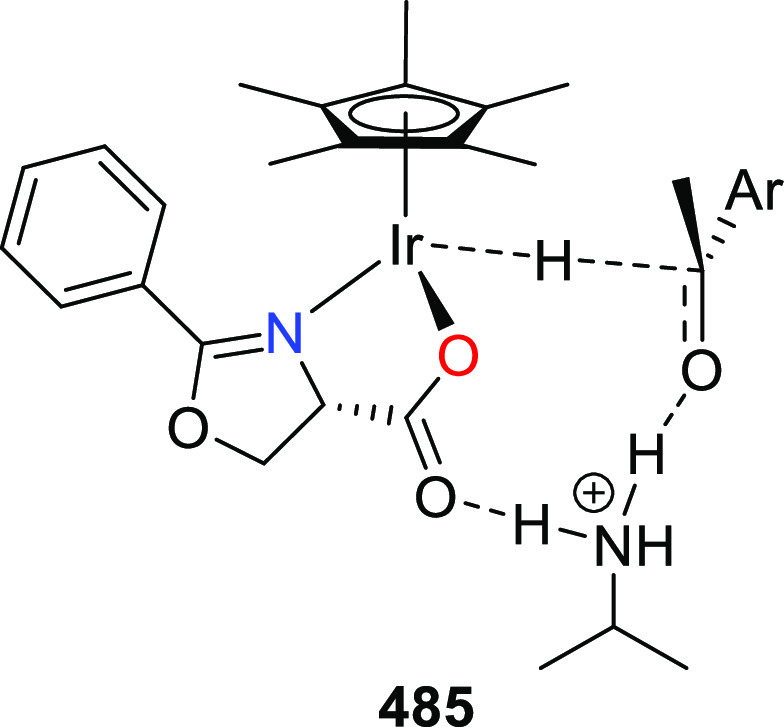

Scheme 90. Regioselective and Stereoselective [3 + 3] Annulation of Ketone-Derived Azomethine Ylides with 2-Indolylethylenes.