Abstract

Background

Androgen deficiency is common among prostate cancer survivors, but many guidelines consider history of prostate cancer a contraindication for testosterone replacement. We determined the safety and efficacy of a selective androgen receptor modulator (OPK-88004) in symptomatic, testosterone-deficient men who had undergone radical prostatectomy for low-grade, organ-confined prostate cancer.

Methods

In this placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind trial, 114 men, ≥19 years of age, who had undergone radical prostatectomy for low-grade, organ-localized prostate cancer, undetectable PSA (<0.1 ng/mL) for ≥2 years after radical prostatectomy and testosterone deficiency were randomized in stages to placebo or 1, 5, or 15 mg OPK-88004 daily for 12 weeks. Outcomes included PSA recurrence, sexual activity, sexual desire, erectile function, body composition, muscle strength and physical function measures, mood, fatigue, and bone markers.

Results

Participants were on average 67.5 years of age and had severe sexual dysfunction (mean erectile function and sexual desire domain scores 7.3 and 14.6, respectively). No participant experienced PSA recurrence or erythrocytosis. OPK-88004 was associated with a dose-related increase in whole-body (P < 0.001) and appendicular (P < 0.001) lean mass and a significantly greater decrease in percent body fat (P < 0.001) and serum alkaline phosphatase (P < 0.001) than placebo. Changes in sexual activity, sexual desire, erectile function, mood, fatigue, physical performance, and bone markers did not differ among groups (P = 0.73).

Conclusions

Administration of OPK-88004 was safe and not associated with PSA recurrence in androgen-deficient men who had undergone radical prostatectomy for organ-confined prostate cancer. OPK-88004 increased lean body mass and decreased fat mass but did not improve sexual symptoms or physical performance.

Keywords: androgen treatment in prostate cancer, quality of life, sexual function, body composition, muscle performance

The majority of men diagnosed today with prostate cancer have low-grade, organ-confined prostate cancer and excellent prospects of long-term survival (1-4). Substantial improvement in survival of men with prostate cancer has focused attention on the high prevalence of sexual dysfunction, physical dysfunction, and low energy, which are important contributors to suboptimal health-related quality of life among survivors (5-9). The pathophysiology of these symptoms after radical prostatectomy is multifactorial, but androgen deficiency is an important remediable contributor to some of the bothersome symptoms, such as low libido, erectile dysfunction, low energy, and physical dysfunction (10-17).

Androgen signaling plays an important role in prostate cancer growth (18-20). Testosterone therapy promotes the growth of metastatic prostate cancer and androgen deprivation causes the regression of metastatic prostate cancer (21-23). However, epidemiologic studies have not revealed a consistent relationship between testosterone levels and prostate cancer risk (24). Intervention studies found little or no effect of testosterone administration on intraprostatic androgen concentrations or on androgen-dependent gene expression in the prostate (25, 26). Retrospective analyses and open-label studies of testosterone replacement in men with prostate cancer who had undergone radical prostatectomy have reported low rates of disease recurrence (27-36). However, Mendelian randomization analysis of the UK biobank data found that genetically determined higher testosterone levels are associated with increased risk of prostate cancer (37). Furthermore, men with Klinefelter syndrome have reduced incidence of prostate cancer and prostate cancer-specific mortality (38). These data suggest that long-term exposure to testosterone could increase prostate cancer risk. The guidelines of many professional societies list history of prostate cancer as a contraindication for testosterone treatment (11, 39). However, testosterone use has been growing among prostate cancer survivors, who have undergone radical prostatectomy and have symptoms of testosterone deficiency (27), even though neither the safety nor the efficacy of testosterone therapy has been established in randomized trials in this population.

Selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs) are a class of ligands that bind androgen receptor and display tissue-selective anabolic activity in the muscle, antiresorptive and anabolic activity in bone, and selectivity for muscle vs prostate (40-44). OPK-88004 (Transition Therapeutics, a subsidiary of OPKO Pharmaceuticals, Miami, FL), a tissue-selective SARM, displays agonist activity in the muscle and osteoanabolic properties on bone mass and biomechanical strength at doses that exhibit no significant effect on prostate and seminal vesicles in gonadectomized mice, induces prostate atrophy in dogs, and suppresses the growth of androgen receptor–positive prostate cancer explants in mice (unpublished data provided by Transition Therapeutics, a subsidiary of OPKO Pharmaceuticals, Miami, FL). In phase 1 human studies, the administration of OPK-88004 suppressed PSA in healthy men. A SARM would be particularly attractive in prostate cancer survivors because it could mitigate the potential risk of prostate cancer growth associated with testosterone administration. This proof-of-concept trial was conducted to determine the safety and generate preliminary evidence of efficacy of this SARM in men who had undergone radical prostatectomy for low-grade, organ-confined prostate cancer and had symptomatic testosterone deficiency. As this was the first randomized trial of an androgen in prostate cancer survivors, there was substantial concern about safety of administering an androgen to men with history of prostate cancer. Therefore, it was necessary to proceed cautiously, starting with a short-term 12-week trial.

Study Design

The study, A Selective Androgen Receptor Modulator in Prostate Cancer Trial (SARM-PC Trial, NCT02499497), was a phase 2 randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel group, double-blind trial approved by the institutional review boards at Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, and by the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions in Baltimore, Maryland. All participants provided written informed consent. An independent data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) reviewed the study’s progress and safety every 6 months.

The trial was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (1R01NR014502). Transition Therapeutics, a subsidiary of OPKO Health, provided OPK-88004 and placebo at no cost to the trial. The sponsor played no role in study design, analysis of data, writing the manuscript, or in the decision to publish.

Participants

The participants were men 19 years of age or older, with confirmed diagnosis of prostate cancer, who had undergone radical prostatectomy for low-grade, organ-localized prostate cancer with very low risk of disease recurrence (Gleason score 6 or 7 [3 + 4]), preoperative PSA < 10 ng/mL; and undetectable PSA levels (<0.1 ng/mL using a sensitive PSA assay) for 2 or more years after radical prostatectomy. The participants were required to have a fasting morning serum testosterone level, measured using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry in a central laboratory (Quest Diagnostics, Chantilly, VA), less than 300 ng/dL and/or free testosterone measured by the equilibrium dialysis method ≤70 pg/mL, and one or more of the following: sexual dysfunction (low sexual desire [DeRogatis Inventory of Sexual Function for Men—II score (DISF-M-II) ≤20 in the sexual desire domain]) (45); erectile dysfunction (International Index of Erectile Function [IIEF] erectile function domain score < 25) (46); fatigue (Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Fatigue [FACIT-F] scale score < 30) (47); or physical dysfunction indicated by self-reported difficulty in walking a 1/4 mile or climbing 2 flights of stairs, and Short Physical Performance Battery score (SPPB) between 4 and 9 points. The testosterone threshold used for eligibility was consistent with that used in other pivotal testosterone trials (14, 15, 48, 49); we did not use the reference range reported by Quest Diagnostics because these ranges have varied over time and the information on the population in which these reference ranges were derived has not been published.

Men who had received radiation therapy or androgen deprivation therapy were excluded. We also excluded men with hematocrit level >50%; serum creatinine >2.5 mg/dL; alanine transaminase (ALT) or aspartate transaminase (AST) above the normal limits; hemoglobin A1c >7.5% or diabetes requiring insulin therapy; body mass index (BMI) >40 kg/m2; myocardial infarction or stroke within 3 months of screening; untreated severe sleep apnea; or major untreated psychiatric condition.

Subject Recruitment

The participants were enrolled from the urology practices of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, and from the Brady Urological Research Institute at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institute, Baltimore, MD. The men who had radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer were identified by searching the electronic medical records (EMR) using a structured process approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of the participating institutions. The EMR-eligible subjects underwent a 2-stage screening process. The first-stage screening was performed on the telephone using an IRB-approved script in which conformity to major eligibility criteria was confirmed, and those who did not have major exclusionary criteria were invited for the second-stage screening. During the in-person screening visit, informed consent was obtained, medical history, medications, and pathology reports were reviewed, and blood counts, chemistries, total and free testosterone levels, and PSA were measured in a fasting sample obtained in the morning. The participants meeting eligibility criteria were scheduled for baseline assessments.

Randomization

To minimize risk to the participants, initially, the participants were randomized in 1:1:1 ratio to placebo, 1 mg OPK-88004 or 5 mg OPK-88004 using permuted block with varying block sizes, stratified by age group (19-50 and >50 years) and phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor (PDEI) use. A prespecified blinded safety analysis of PSA recurrence rates was performed after 50 participants had completed the study. Because none of the first 50 randomized participants experienced a biochemical PSA recurrence or clinical disease recurrence, the 1 mg dose, which in phase 1 studies was found to be at the low end of dose response curve, was discontinued and a 15-mg dose was added with the approval of the trial’s DSMB and the IRB. Subsequently, the eligible subjects were randomized in 1:1:3 ratio to placebo, 5 mg OPK-88004 or 15 mg OPK-88004. Twenty-four participants were randomized using this scheme. The study team became of aware of reversible AST and ALT elevations at the 15-mg dose in another contemporary trial of OPK-88004 in older adults; therefore, the 15-mg dose was discontinued and the remaining 10 participants were randomized to placebo or the 5-mg dose. In total, 114 participants were enrolled: 36 in the placebo arm, 28 in the 1 mg OPK-88004, 36 in the 5 mg OPK-88004, and 14 in the 15 mg OPK-88004 groups.

Intervention

The study intervention included 1 of 3 doses of OPK-88004 (1, 5, or 15 mg daily) taken orally. The comparator group received matching placebo tablets. In phase 1 trials in healthy volunteers, and the phase 2 trial of 6-months duration, these doses of OPK-88004 were safe and efficacious in increasing fat-free mass. Serum PSA levels reach a plateau within 3 months after starting testosterone treatment; therefore, a 3-month intervention duration was deemed sufficient to detect meaningful changes in PSA (50).

Adherence

The adherence was measured during weeks 4, 8, and 12 by counting the number of tablets used, expressed as a percentage of the total number of doses that should have been used.

Blinding

The study staff and participants were blinded to treatment assignment, which was known only to investigational drug pharmacist and the unblinded statistician.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was change from baseline in sexual activity score, assessed by the Harbor-UCLA 7-Day Psychosexual Diary (51). Erectile function was assessed using the 15-item International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) (46), sexual desire using the 25-item DeRogatis Inventory of Sexual Function for Men—Sexual Desire (45) and by the 25-item Male Sexual Health Questionnaire (MSHQ) (52). The health-related quality of life (HRQOL) was assessed using the hormonal and sexual domains of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) (53), a 50-item, disease-specific HRQOL questionnaire designed to evaluate the impact of treatments on HRQOL in men with prostate cancer. Wellbeing was assessed using the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) (54).

Whole-body, appendicular, and trunk lean mass were measured using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), calibrated using a soft tissue phantom before each scan. The maximal voluntary muscle strength was measured in the leg press exercise using the 1-repetition method, and physical function was assessed by measuring the stair-climbing speed and power, 6-minute walking distance, and loaded and unloaded 50-meter walking speed, as described previously (55).

Serum total testosterone levels during screening was measured in the Quest Diagnostics Laboratory, Chantilly, VA, using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method certified by the Hormone Standardization Program for Testosterone (HoST) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia. Free testosterone level for screening was measured using an equilibrium dialysis method. Serum sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) and luteinizing hormone (LH) levels were measured using 2-site directed immuno-chemiluminescence assays with sensitivity 2.5 nmol/L, and 0.1 U/L, respectively, and coefficients of variation less than 10% in low, medium, and high range.

Safety Monitoring

Serum PSA levels, complete blood counts, plasma lipids, AST, ALT, and bilirubin were measured at baseline and during weeks 4, 8, and 12. Biochemical recurrence was defined a priori as …“a PSA during the intervention period of ≥0.2 ng/mL with a second confirmatory level of PSA ≥0.2 ng/mL,” as proposed by an Expert Panel of American Urological Association (56). Adverse events (AE) and serious adverse events (SAE) summary reports were classified using MeDRA and System Organ Classification and reviewed by the trial’s DSMB every 6 months.

Statistical Analyses

The analyses were performed using intention-to-treat strategy; the participants were analyzed according to assignment at randomization. Exploratory analysis assessed data distribution, skewness, heteroscedasticity, and modeling assumptions. Primary and secondary outcomes were expressed as change from baseline and were analyzed using mixed effects regression models with time-in-treatment, randomization, and time-by-treatment interaction as fixed effects controlling for baseline values and stratification (age and PDEI use) and subjects treated as a random factor. The primary targets of estimation were direct comparison of the 5-mg dose group to placebo and overall dose effect. Point estimates along with 95% CIs and P values were extracted from the models using treatment contrasts. Sensitivity analyses were performed adjusting for stage of enrollment effect. For missing data, multiple imputation by chained equations method was used in accordance with the mixed effects model. All analyses used 2-sided type I error probability of 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC) and R software version 3.2.5 (R foundation, Vienna, Austria).

The total sample size of 114 subjects per arm was required to achieve more than 90% power to reject the null hypothesis of no overall dose effect, and to detect the difference between the 5-mg group and placebo in the primary outcome (change in sexual activity score derived from Harbor-UCLA 7-Day Psychosexual Diary), assuming 2-sided type I error of 0.05 and 20% attrition rate and moderate to large effect sizes. As enrollment to 15-mg group was stopped and insufficient number of participants were randomized to this group (N = 14), there was no formal analysis testing difference between the 15-mg arm and placebo. Similarly, simulation results indicated that this design provided 90% statistical power to detect moderate to large effects on other measures of sexual function and difference between groups in lean body mass change.

Results

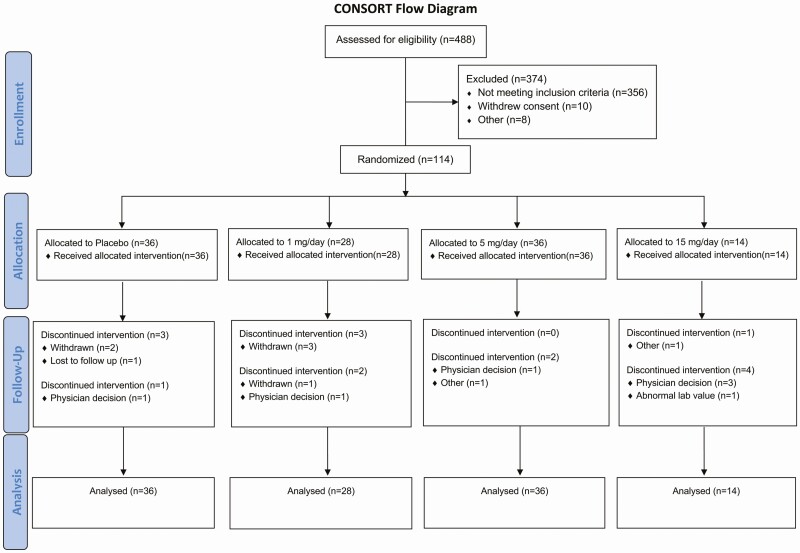

Among the 2729 men who underwent telephone screening, 488 were assessed in person and 114 eligible participants were randomized (87 at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and 27 at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institute) to 1 of 4 treatment groups to receive placebo (N = 36), 1 mg OPK-88004 (N = 28), 5 mg OPK-88004 (N = 36), or 15 mg OPK-88004 (N = 14) daily (Fig. 1, CONSORT Diagram). The most frequent reasons for screen failure included participant concerns about using an androgen and time commitment, exclusionary medical conditions, exclusionary medications, out-of-range testosterone level, out-of-range BMI, and not meeting the qualifying criteria for symptoms or conditions.

Figure 1.

The CONSORT diagram. The flow of subjects through the various phases of the trial is shown.

Participant Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the participants were similar among the 4 groups (Table 1). The participants were on average 67.5 years of age and overweight (BMI mean ± SD: 29.0 ± 4.1 kg/m2). The vast majority of participants were included based on sexual symptoms (low sexual desire or erectile dysfunction [ED]). The IIEF erectile function domain average score was 7.3 ± 7.9, indicating severe ED. The baseline Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) score was 11.2 ± 1.2, indicating that the majority of participants had mild or no physical dysfunction.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants by treatment arm and overall

| Placebo N = 36 | 1 mg/day N = 28 | 5 mg/day N = 36 | 15 mg/day N = 14 | Overall N = 114 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 67.1 ± 6.1 | 67.1 ± 7.87 | 67.4 ± 8.6 | 69.6 ± 7.1 | 67.5 ± 7.5 |

| Weight, kg | 84.9 ± 12.7 | 92.7 ± 10.7 | 89.7 ± 15.4 | 86.7 ± 12.5 | 88.5 ± 13.4 |

| BMI, kg/m 2 | 27.9 ± 3.8 | 29.8 ± 3.89 | 29.3 ± 4.1 | 29.2 ± 5.1 | 29.0 ± 4.1 |

| SPPB score | 11.4 ± 1.15 | 11.1 ± 1.21 | 11.1 ± 1.42 | 11.1 ± 1.07 | 11.2 ± 1.24 |

| PDQ-4 | |||||

| Sexual Activity score | 1.55 ± 1.20 | 1.38 ± 1.28 | 1.76 ± 1.54 | 0.97 ± 1.20 | 1.50 ± 1.32 |

| Mood | |||||

| Positive | 5.22 ± 1.12 | 5.53 ± 0.86 | 5.44 ± 1.11 | 5.17 ± 0.93 | 5.36 ± 1.03 |

| Negative | 1.12 ± 0.86 | 1.38 ± 1.14 | 1.09 ± 0.95 | 1.58 ± 0.92 | 1.23 ± 0.97 |

| IIEF | 22.4 ± 16.9 | 21.0 ± 14.7 | 22.9 ± 16.0 | 22.2 ± 17.3 | 22.2 ± 15.9 |

| Erectile Function | 7.2 ± 8.6 | 6.5 ± 6.9 | 8.0 ± 7.8 | 7.2 ± 8.9 | 7.3 ± 7.9 |

| Intercourse Satisfaction | 2.4 ± 4.2 | 1.8 ± 3.6 | 2.6 ± 3.9 | 2.5 ± 4.5 | 2.3 ± 4.0 |

| Orgasmic Function | 4.2 ± 3.3 | 4.0 ± 3.7 | 4.0 ± 3.6 | 3.8 ± 4.0 | 4.1 ± 3.5 |

| Sexual Desire | 4.4 ± 1.7 | 4.6 ± 2.0 | 4.8 ± 1.9 | 4.6 ± 1.6 | 4.6 ± 1.8 |

| Overall Satisfaction | 4.3 ± 2.1 | 4.1 ± 1.9 | 3.6 ± 1.9 | 4.6 ± 1.8 | 4.1 ± 1.9 |

| IPSS | |||||

| Symptom | 7.1 ± 5.1 | 7.8 ± 6.0 | 5.6 ± 3.9 | 6.9 ± 3.2 | 6.7 ± 4.8 |

| Quality of Life Due to Urinary Symptoms | 2.0 ± 1.4 | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 1.7 ± 1.5 | 2.0 ± 1.5 | 1.8 ± 1.4 |

| DISF-M-II | 48.1 ± 20.5 | 42.4 ± 19.1 | 39.9 ± 17.3 | 40.8 ± 20.8 | 43.2 ± 19.3 |

| Sexual Desire | 14.6 ± 3.97 | 14.4 ± 6.22 | 14.9 ± 4.43 | 14.3 ± 5.44 | 14.6 ± 4.87 |

| Sexual Arousal | 5.06 ± 6.18 | 4.21 ± 5.31 | 4.58 ± 4.64 | 4.86 ± 5.63 | 4.68 ± 5.39 |

| Sexual Activity | 8.78 ± 4.11 | 7.18 ± 3.83 | 6.64 ± 4.11 | 6.43 ± 3.39 | 7.42 ± 4.03 |

| Orgasm | 8.58 ± 5.75 | 8.00 ± 6.45 | 6.97 ± 5.26 | 8.50 ± 6.37 | 7.92 ± 5.82 |

| Sexual Satisfaction | 11.0 ± 6.9 | 8.61 ± 5.00 | 6.75 ± 5.43 | 6.71 ± 4.58 | 8.55 ± 5.97 |

| MSHQ | |||||

| Erection | 5.32 ± 3.10 | 4.84 ± 2.90 | 5.92 ± 3.47 | 5.92 ± 4.23 | 5.48 ± 3.30 |

| Ejaculation | 7.12 ± 6.94 | 7.92 ± 6.14 | 8.61 ± 8.04 | 8.67 ± 8.75 | 7.98 ± 7.31 |

| Satisfaction | 19.1 ± 4.84 | 17.1 ± 3.82 | 15.7 ± 5.68 | 15.4 ± 3.70 | 17.1 ± 4.99 |

| FACIT-F | 41.9 ± 8.82 | 42.1 ± 8.07 | 43.2 ± 7.55 | 42.4 ± 6.42 | 42.4 ± 7.89 |

| PANAS | |||||

| Positive Affect | 33.4 ± 7.07 | 34.5 ± 5.21 | 34.8 ± 6.38 | 34.1 ± 7.62 | 34.2 ± 6.46 |

| Negative Affect | 14.9 ± 6.08 | 13.7 ± 2.97 | 14.0 ± 4.71 | 17.2 ± 6.56 | 14.6 ± 5.15 |

| Physical function | |||||

| Gait speed in 6-minute walk, m/sec | 1.54 ± 0.20 | 1.54 ± 0.14 | 1.45 ± 0.22 | 1.44 ± 0.21 | 1.50 ± 0.20 |

| Unloaded 50m walk gait speed, m/sec | 2.01 ± 0.30 | 2.05 ± 0.27 | 2.04 ± 0.39 | 1.74 ± 0.29 | 1.99 ± 0.33 |

| Loaded 50m walk gait speed, m/sec | 1.97 ± 0.27 | 1.98 ± 0.26 | 1.94 ± 0.37 | 1.75 ± 0.31 | 1.93 ± 0.31 |

| Unloaded stair climb power, watts | 464.0 ± 116.3 | 525.6 ± 103.0 | 471.0 ± 133.9 | 442.6 ± 122.3 | 476.5 ± 121.3 |

| Loaded stair climb power, watts | 523.8 ± 122.3 | 600.3 ± 119.4 | 557.0 ± 176.6 | 544.8 ± 100.9 | 552.2 ± 134.8 |

| Leg Press 1-RM, N | 2333.6 ± 470.9 | 2294.0 ± 441.5 | 2407.3 ± 420.8 | 2347.2 ± 384.8 | 2351.4 ± 430.8 |

| Physical function domain of MOS SF-36 score | 88.4 ± 12.4 | 87.8 ± 15.2 | 84.4 ± 17.3 | 85.4 ± 24.1 | 86.6 ± 16.3 |

| DXA | |||||

| Appendicular fat mass, kg | 10.9 ± 2.8 | 13.2 ± 3.5 | 11.8 ± 3.7 | 10.9 ± 3.2 | 11.7 ± 3.4 |

| Trunk Fat Mass, kg | 15.7 ± 4.4 | 18.5 ± 5.1 | 16.5 ± 4.8 | 16.5 ± 5.8 | 16.7 ± 4.9 |

| Total fat mass, kg | 27.8 ± 6.9 | 33.0 ± 8.3 | 29.5 ± 8.2 | 28.6 ± 9.1 | 29.7 ± 8.1 |

| Appendicular lean mass, kg | 23.7 ± 3.2 | 24.7 ± 2.4 | 24.1 ± 3.8 | 23.7 ± 3.6 | 24.0 ± 3.3 |

| Trunk lean mass, kg | 26.9 ± 3.8 | 27.1 ± 5.7 | 27.4 ± 4.0 | 26.9 ± 3.4 | 27.1 ± 4.3 |

| Total Lean Mass, kg | 54.0 ± 6.9 | 56.3 ± 5.0 | 55.0 ± 7.9 | 54.1 ± 6.9 | 54.9 ± 6.8 |

| Total percent fat, % | 32.6 ± 5.08 | 35.4 ± 6.03 | 33.3 ± 4.34 | 32.9 ± 6.50 | 33.5 ± 5.33 |

| Laboratory hematology | |||||

| White blood cell count, K/uL | 6.20 ± 1.46 | 5.66 ± 1.65 | 5.98 ± 1.48 | 5.87 ± 1.52 | 5.96 ± 1.52 |

| Red blood cell count, Mcells/uL | 4.89 ± 0.34 | 4.81 ± 0.38 | 4.85 ± 0.47 | 4.85 ± 0.56 | 4.85 ± 0.42 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 14.9 ± 1.23 | 15.0 ± 0.84 | 14.9 ± 0.95 | 14.7 ± 1.04 | 14.9 ± 1.02 |

| Hematocrit, % | 44.6 ± 3.19 | 45.1 ± 2.71 | 44.7 ± 3.04 | 44.0 ± 3.34 | 44.7 ± 3.03 |

| MCV, fL | 91.3 ± 3.39 | 94.0 ± 5.05 | 92.5 ± 4.69 | 91.3 ± 6.91 | 92.3 ± 4.81 |

| MCH, pg | 30.4 ± 1.47 | 31.2 ± 1.76 | 30.9 ± 1.91 | 30.4 ± 2.08 | 30.8 ± 1.77 |

| MCHC, g/dL | 33.3 ± 0.86 | 33.2 ± 0.64 | 33.4 ± 0.76 | 33.4 ± 0.89 | 33.3 ± 0.77 |

| RDW, % | 13.9 ± 1.16 | 14.0 ± 0.72 | 14.0 ± 1.20 | 13.6 ± 1.14 | 13.9 ± 1.07 |

| Platelet count, K/uL | 213.8 ± 43.4 | 198.4 ± 45.8 | 213.7 ± 58.7 | 205.6 ± 41.3 | 209.0 ± 48.9 |

| MPV, fL | 9.58 ± 0.99 | 9.21 ± 0.97 | 9.36 ± 1.03 | 9.97 ± 1.43 | 9.47 ± 1.07 |

| PSA, ng/mL | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 | <0.1 |

| Glucose homeostasis | |||||

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 5.80 ± 0.45 | 5.68 ± 0.45 | 5.63 ± 0.48 | 5.61 ± 0.53 | 5.69 ± 0.47 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 104.0 ± 17.5 | 99.4 ± 14.0 | 97.3 ± 10.0 | 103.2 ± 20.8 | 100.6 ± 15.2 |

| Insulin, uIU/mL | 8.33 ± 4.83 | 10.5 ± 5.21 | 10.0 ± 5.65 | 9.06 ± 5.02 | 9.49 ± 5.23 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.15 ± 1.52 | 2.74 ± 1.46 | 2.45 ± 1.44 | 2.32 ± 1.23 | 2.40 ± 1.44 |

| Liver function tests | |||||

| AST, U/L | 21.4 ± 6.76 | 23.3 ± 5.80 | 19.7 ± 3.83 | 25.1 ± 7.87 | 21.7 ± 6.10 |

| ALT, U/L | 22.3 ± 7.63 | 28.4 ± 17.2 | 21.4 ± 7.47 | 25.5 ± 10.9 | 23.9 ± 11.3 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.69 ± 0.23 | 0.73 ± 0.26 | 0.77 ± 0.39 | 0.65 ± 0.22 | 0.72 ± 0.30 |

| Lipid panel | |||||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 178.4 ± 28.0 | 174.9 ± 29.6 | 173.4 ± 33.1 | 179.3 ± 30.6 | 176.1 ± 30.1 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 56.1 ± 14.6 | 51.5 ± 13.9 | 51.3 ± 13.2 | 50.7 ± 15.4 | 52.8 ± 14.1 |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 102.4 ± 25.1 | 100.8 ± 28.1 | 100.7 ± 28.8 | 103.7 ± 24.2 | 101.6 ± 26.6 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 99.2 ± 41.3 | 122.0 ± 56.8 | 107.9 ± 46.2 | 142.1 ± 90.2 | 112.8 ± 55.6 |

| Bone markers | |||||

| NTx, nM BCE | 13.8 ± 6.25 | 13.2 ± 4.81 | 12.2 ± 4.41 | 11.3 ± 5.59 | 12.8 ± 5.28 |

| Osteocalcin, ng/mL | 9.33 ± 4.47 | 9.24 ± 4.42 | 9.37 ± 4.51 | 6.89 ± 2.27 | 9.02 ± 4.28 |

| PINP, ug/L | 53.1 ± 23.8 | 51.0 ± 16.2 | 45.2 ± 14.4 | 42.2 ± 14.0 | 48.6 ± 18.4 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 73.0 ± 16.9 | 62.3 ± 16.3 | 59.3 ± 15.9 | 63.3 ± 11.5 | 64.9 ± 16.7 |

| Bone alkaline phosphatase, ng/mL | 18.5 ± 7.18 | 15.4 ± 4.90 | 15.9 ± 4.73 | 14.5 ± 3.01 | 16.4 ± 5.62 |

| Testosterone | |||||

| Total testosterone, ng/dL | 391.1 ± 120.7 | 379.7 ± 140.9 | 398.5 ± 192.6 | 392.1 ± 102.7 | 391.0 ± 149.4 |

| Free testosterone, pg/mL | 28.2 ± 9.4 | 31.0 ± 12.8 | 30.2 ± 9.7 | 30.0 ± 9.0 | 29.7 ± 10.2 |

| SHBG, nmol/L | 36.2 ± 14.1 | 36.5 ± 14.1 | 39.1 ± 16.1 | 38.5 ± 17.7 | 37.5 ± 15.1 |

| LH, mIU/mL | 5.68 ± 5.24 | 4.50 ± 2.89 | 6.03 ± 6.10 | 4.04 ± 2.46 | 5.34 ± 4.89 |

| Estradiol, pg/mL | 24.8 ± 8.4 | 25.4 ± 8.1 | 27.0 ± 7.9 | 27.4 ± 5.3 | 26.0 ± 7.8 |

Values are presented as mean ± SD.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; BMI, body mass index; DISF-M-II, DeRogatis Inventory of Sexual Function for Men—II; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Fatigue; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance; IIEF, International Index of Erectile Function; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Scale; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LH, luteinizing hormone; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MSHQ, Male Sexual Health Questionnaire; NTx, N-telopeptide of type I collagen; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Scale; PDQ-4, Psychosexual Daily Questionnaire, Question 4; PINP, procollagen I intact N-terminal; RDW, red blood cell distribution width; SHBG, sex hormone–binding globulin; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Adherence

The adherence to study medication, measured using the medication logs and pill counts, ranged from 93.3% to 99.0% in the various intervention arms.

Prostate Safety

Serum PSA levels fluctuated between <0.1 ng/mL and 0.1 ng/mL in all groups throughout the intervention period and no subject in the trial experienced biochemical recurrence, using the prespecified definition (see “Methods”). There were no significant changes in lower urinary tract symptoms, assessed using the International Prostate Symptom Score (P = 0.10).

Other Safety Measures

No participants in any intervention arm experienced erythrocytosis. One participant randomized to the 15-mg dose had AST and ALT elevations above the upper limit of normal. The proportions of men with AEs or SAEs were similar across groups (Table 2). Three SAEs, not considered drug-related, were observed during the study: 1 participant in the 1-mg group underwent coronary artery bypass grafting; 1 participant in the 15-mg group was diagnosed with lung and liver cancer; and 1 individual in the placebo group was diagnosed with renal cancer. The observed AEs were mild and of variable clinical significance (Table 2). For instance, the dermatologic effects reported by subjects included poison ivy rash, bug bites, itchy sensation, skin rash, arm hematomas, skin cuts, sunburn, bruises and abrasions, benign cysts, and removal of actinic keratosis and basal cell carcinoma. The musculoskeletal AEs included sore muscles, achy muscles and joints, sore neck, sore shoulders, sprains, sciatica, tendinitis, and muscle cramps. The infectious disease AEs included coughs and colds, flu symptoms, nasal congestion, sore throat, sinus infection, and acute respiratory illnesses.

Table 2.

Number of AEs and participants with one or more on-treatment adverse events, by physiologic system

| 1 mg/day (n = 28) | 5 mg/day (n = 36) | 15 mg/day (n = 14) | Placebo (n = 36) | P value* (5 mg/day vs Placebo) | P value* (any effect) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | 9 (5) | 5 (5) | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 0.73 | 0.10 |

| Dermatologic | 12 (7) | 19 (11) | 18 (5) | 12 (10) | 0.55 | 0.018 |

| Endocrine/metabolic | 3 (2) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0.25 | 0.27 |

| Gastrointestinal | 5 (3) | 9 (8) | 3 (2) | 15 (7) | 0.065 | 0.09 |

| Genital/urinary | 1 (1) | 5 (4) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0.065 | 0.12 |

| Hematologic/lymphatic | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 1(1) | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Hepatic/biliary | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | -- | 0.16 |

| Musculoskeletal | 4 (4) | 21 (15) | 10 (5) | 13 (9) | 0.37 | 0.033 |

| Neurologic | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 0.18 | 0.37 |

| Psychiatric | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0.99 | 0.82 |

| Respiratory | 3 (2) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 5 (3) | 0.52 | 0.77 |

| Infectious disease | 15 (6) | 8 (7) | 1 (1) | 7 (5) | 0.90 | 0.004 |

| Other | 8 (5) | 17(10) | 7 (5) | 18 (13) | 0.40 | 0.37 |

| One or more SAEa | 1b | -- | 1c | 1d | -- | -- |

Abbreviation: SAE, serious adverse event.

*Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for the difference between number of events across all 4 groups and comparison between placebo and 5 mg/day dose.

a There was 1 SAE (myocardial infarction) reported from the 1 mg/day dose group; however, it occurred before drug administration, hence it is not counted in this table.

b Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (hospitalization).

c Renal cancer.

d Lung and liver cancer.

Sexual Function

The changes from baseline in Psychosexual Daily Questionnaire 4 (PDQ-4) score over the 12-week intervention period did not differ significantly across groups (P = 0.73), and there was no significant difference between study arms (Table 3). Overall, there were no significant differences in the change from baseline in erectile function domain scores among the intervention arms either using the IIEF (P = 0.15) or the MSHQ erection domain score (P = 0.08), or in the DISF-M-II sexual desire (P > 0.50) across the study arms (Table 3). There were no significant differences in changes in other domains of sexual function (eg, arousal, ejaculation, orgasm) assessed using either the DISF or the MSHQ (Table 3).

Table 3.

Estimated changes from baseline in sexual function outcomes by treatment arm

| Variable | Placebo | 1 mg/day | 5 mg/day | 15 mg/day | P value (5 mg/day vs placebo) | P value (any effect) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDQ-4 | ||||||

| Sexual Activity score | 0.04 (−0.36, 0.44) | 0.31 (−0.14, 0.76) | 0.09 (−0.28, 0.45) | −0.05 (−0.62, 0.53) | 0.85 | 0.73 |

| IIEF | ||||||

| Erectile Function | 2.48 (0.56, 4.40) | 1.18 (−1.05, 3.41) | −0.15 (−1.99, 1.69) | 2.92 (−0.13, 5.97) | 0.041 | 0.15 |

| Total score | 4.89 (1.16, 8.63) | 2.69 (−1.65, 7.03) | −0.40 (−3.97, 3.16) | 4.92 (−1.03, 10.9) | 0.035 | 0.16 |

| MSHQ | ||||||

| Erection | 0.64 (−0.05, 1.34) | 0.67 (−0.15, 1.50) | −0.33 (−0.97, 0.32) | 0.91 (−0.22, 2.03) | 0.037 | 0.08 |

| Ejaculation | 1.22 (−0.95, 3.39) | 2.68 (0.06, 5.30) | −0.29 (−2.35, 1.78) | −1.01 (−4.55, 2.54) | 0.30 | 0.22 |

| Satisfaction | 1.08 (−0.17, 2.33) | 1.11 (−0.36, 2.59) | −0.45 (−1.70, 0.81) | 1.00 (−1.02, 3.02) | 0.08 | 0.25 |

| DISF-M-II | 0.90 (−4.93, 6.73) | 2.56 (−4.14, 9.27) | 0.94 (−4.55, 6.44) | 3.48 (−5.40, 12.37) | 0.99 | 0.94 |

| Sexual Desire | −0.58 (−2.56, 1.41) | 0.56 (−1.76, 2.87) | −0.32 (−2.22, 1.58) | 1.69 (−1.36, 4.75) | 0.84 | 0.58 |

| Sexual Arousal | 0.42 (−0.87, 1.72) | 0.47 (−1.05, 1.98) | 0.61 (−0.62, 1.85) | 0.87 (−1.13, 2.87) | 0.83 | 0.98 |

| Sexual Activity | 0.34 (−0.94, 1.62) | 0.78 (−0.68, 2.24) | 0.53 (−0.67, 1.74) | 0.14 (−1.79, 2.08) | 0.82 | 0.95 |

| Orgasm | 0.63 (−0.94, 2.21) | 0.12 (−1.70, 1.94) | 0.30 (−1.19, 1.79) | −0.04 (−2.45, 2.38) | 0.75 | 0.96 |

| Sexual Satisfaction | 0.54 (−1.03, 2.12) | 0.89 (−0.89, 2.66) | −0.21 (−1.67, 1.26) | 0.71 (−1.65, 3.08) | 0.48 | 0.76 |

Estimates and 95% CIs extracted from mixed model framework. P values for overall dose effect and comparison between 5mg/day and placebo groups.

Abbreviations: DISF-M-II, DeRogatis Index of Sexual Function Male II; IIEF, International Index of Erectile Function; MSHQ, Male Sexual Health Questionnaire; PDQ-4, Psychosexual Daily Questionnaire 4.

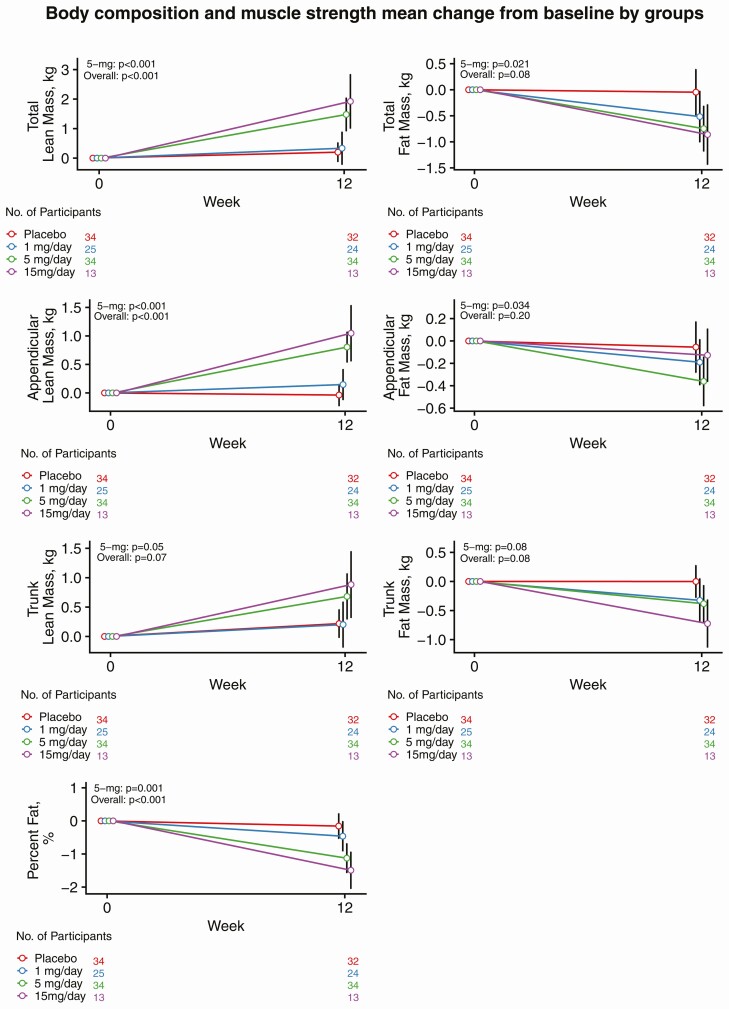

Body Composition

The administration of OPK-88004 was associated with a dose-related increase in whole-body lean mass (P < 0.001; Fig. 2). The changes in whole-body lean mass from baseline were significantly greater in men randomized to the 5-mg dose (average increase +1.5 kg; 95% CI: 1.0, 2.0) than in those randomized to placebo (average change +0.3 kg; 95% CI: −0.3, 0.8). OPK-88004 treatment was also associated with a significant increase in appendicular lean mass (P < 0.001); the increase in appendicular lean body mass was significantly greater in men treated with the 5 mg (average increase +0.8 kg; 95% CI: 0.6, 1.1) relative to placebo (average change −0.03 kg; 95% CI: −0.29, 0.23). Percentage whole-body fat mass decreased modestly but significantly in men randomized to OPK-88004 (P < 0.001); the decrease in percent fat was significantly greater in the 5 mg (average change −1.1%; 95% CI: −1.5, −0.7) group than in the placebo group (average change −0.1%; 95% CI: −0.6, 0.3) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The changes from baseline in whole-body, appendicular, and trunk lean and fat mass by treatment arms. Estimates and 95% CIs for change from baseline extracted from mixed model framework are shown. P values are for overall dose effect and comparison between 5 mg/day and placebo groups.

Muscle Performance and Physical Function

Changes in gait speed (6-minute walk, unloaded and loaded 50 meters walk tests) did not differ across all 4 groups and between 5 mg and control arm (Table 3: all P values > 0.20). Similarly, there were no statistically significant differences among arms in changes from baseline in unloaded or loaded stair climb and the maximal voluntary strength in the leg press exercise (Table 4: all P values > 0.2).

Table 4.

Estimated changes from baseline in muscle performance and physical function outcomes by treatment arm

| Variable | Placebo | 1 mg/day | 5 mg/day | 15 mg/day | P value (5 mg/day vs Placebo) | P value (any effect) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gait speed in 6-minute walk, m/sec | 0.06 (0.02, 0.10) | 0.08 (0.04, 0.13) | 0.09 (0.05, 0.12) | 0.06 (−0.001, 0.12) | 0.32 | 0.71 |

| Unloaded 50m walk gait speed, m/sec | 0.06 (−0.01, 0.12) | 0.13 (0.05, 0.20) | 0.03 (−0.03, 0.09) | 0.08 (−0.03, 0.19) | 0.52 | 0.26 |

| Loaded 50m walk gait speed, m/sec | 0.05 (−0.02, 0.12) | 0.12 (0.03, 0.20) | 0.05 (−0.02, 0.12) | 0.11 (0.001, 0.22) | 0.93 | 0.44 |

| Unloaded stair climb power, watts | 7.2 (−35.2, 49.5) | 26.6 (−26.1, 79.2) | 0.14 (−40.5, 40.7) | 45.0 (−26.8, 116.9) | 0.80 | 0.65 |

| Loaded stair climb power, watts | 10.9 (−31.7, 53.5) | −6.6 (−59.2, 45.9) | −6.8 (−54.1, 40.6) | 72.2 (2.99, 141.4) | 0.56 | 0.25 |

| Leg press 1-RM, N | 7.5 (−87.9, 102.9) | 138.6 (17.9, 259.3) | 55.6 (−28.0, 139.2) | 98.9 (−35.6, 233.5) | 0.44 | 0.30 |

The data are point estimates and 95% CIs extracted from mixed model framework. P values for overall and for prespecified comparison of 5-mg vs placebo.

Abbreviation: 1-RM, one repetition maximum in Newtons.

Bone Turnover Markers

The changes in serum osteocalcin, N-telopeptide of type I collagen (NTx), and procollagen I intact N-terminal propeptide (PINP) did not differ significantly between arms during intervention period (Table 5: all P values > 0.20). Serum alkaline phosphatase showed significant difference in change from baseline across the intervention arms (P < 0.001); the men randomized to the 5-mg group had a significantly greater decrease in serum alkaline phosphatase levels than placebo (−10.2 U/L; 95% CI: −12.9, −7.6, and −2.6 U/L; 95% CI: −5.4, 0.3, respectively). Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase did not show an overall dose effect but decreased significantly in men assigned to the 15-mg dose group.

Table 5.

Estimated changes from baseline in laboratory measures by treatment arm

| Variable | Placebo | 1 mg/day | 5 mg/day | 15 mg/day | P value (5 mg/day vs Placebo) | P value (any effect) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory hematology | ||||||

| White blood cell, K/uL | −0.22 (−0.54, 0.09) | 0.14 (−0.22, 0.50) | −0.23 (−0.52, 0.06) | 0.18 (−0.29, 0.65) | 0.98 | 0.19 |

| Red blood cell, K/uL | −0.07 (−0.14, −0.01) | −0.05 (−0.12, 0.03) | 0.02 (−0.04, 0.08) | −0.02 (−0.12, 0.09) | 0.038 | 0.20 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | −0.32 (−0.51, −0.12) | −0.05 (−0.28, 0.18) | 0.08 (−0.11, 0.27) | −0.20 (−0.50, 0.11) | 0.003 | 0.026 |

| Hematocrit, % | −0.58 (−1.19, 0.03) | 0.0004 (−0.71, 0.71) | 0.58 (−0.002, 1.16) | −0.29 (−1.23, 0.65) | 0.005 | 0.040 |

| MCV, fL | 0.41 (−0.24, 1.07) | 0.73 (−0.04, 1.50) | 0.84 (0.22, 1.46) | 0.02 (−0.98, 1.03) | 0.32 | 0.50 |

| RDW, % | 0.06 (−0.18, 0.29) | 0.10 (−0.17, 0.37) | 0.23 (0.01, 0.46) | −0.22 (−0.58, 0.13) | 0.25 | 0.18 |

| Platelet count, K/uL | −0.78 (−9.93, 8.36) | 0.62 (−10.02, 11.3) | 11.2 (2.52, 19.9) | 43.0 (29.0, 56.9) | 0.050 | <0.001 |

| Glucose homeostasis | ||||||

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | −0.06 (−0.14, 0.03) | −0.07 (−0.16, 0.03) | −0.04 (−0.11, 0.04) | −0.09 (−0.22, 0.03) | 0.70 | 0.87 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 0.62 (−2.39, 3.63) | 1.65 (−1.81, 5.11) | −3.63 (−6.47, −0.80) | −7.54 (−12.1, −2.96) | 0.035 | 0.003 |

| Insulin, uIU/mL | 0.27 (−1.11, 1.65) | 0.67 (−0.99, 2.33) | −0.34 (−1.63, 0.95) | −0.37 (−2.41, 1.67) | 0.50 | 0.74 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.03 (−0.37, 0.44) | 0.18 (−0.31, 0.67) | −0.20 (−0.57, 0.18) | −0.22 (−0.82, 0.38) | 0.39 | 0.56 |

| Liver function tests | ||||||

| AST, U/L | −0.61 (−3.19, 1.98) | −0.49 (−3.50, 2.52) | 3.14 (0.64, 5.65) | 8.57 (4.51, 12.6) | 0.032 | <0.001 |

| ALT, U/L | −1.51 (−7.36, 4.34) | −2.03 (−8.92, 4.85) | 0.93 (−4.65, 6.50) | 17.6 (8.66, 26.6) | 0.53 | 0.003 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | −0.13 (−0.17, −0.09) | −0.04 (−0.09, 0.01) | −0.14 (−0.18, −0.10) | −0.17 (−0.24, −0.11) | 0.84 | 0.003 |

| Lipid panel | ||||||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | −7.25 (−14.9, 0.41) | −14.9 (−23.8, −6.01) | −15.8 (−23.1, −8.42) | −13.3 (−25.1, −1.52) | 0.10 | 0.36 |

| HDL, mg/dL | −2.43 (−4.43, −0.43) | −5.48 (−7.82, −3.15) | −13.5 (−15.4, −11.6) | −18.4 (−21.5, −15.4) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| LDL, mg/dL | −5.34 (−11.8, 1.13) | −6.70 (−14.2, 0.83) | −0.07 (−6.25, 6.12) | 7.44 (−2.51, 17.4) | 0.22 | 0.09 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 1.97 (−11.0, 14.9) | −14.7 (−29.9, 0.53) | −15.0 (−27.4, −2.70) | −14.0 (−34.0, 6.01) | 0.050 | 0.18 |

| Bone markers | ||||||

| NTX, nM BCE | 0.60 (−0.53, 1.73) | −0.33 (−1.65, 0.99) | 0.54 (−0.51, 1.58) | 0.54 (−1.15, 2.24) | 0.93 | 0.67 |

| Osteocalcin, ng/mL | 0.10 (−0.64, 0.84) | −0.29 (−1.15, 0.57) | −0.08 (−0.77, 0.61) | 0.09 (−1.02, 1.20) | 0.72 | 0.90 |

| PINP, ug/L | 2.41 (−0.66, 5.49) | 1.89 (−1.68, 5.46) | 5.13 (2.31, 7.96) | 0.07 (−4.50, 4.63) | 0.18 | 0.20 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | −2.56 (−5.43, 0.30) | −3.38 (−6.54, −0.21) | −10.2 (−12.9, −7.61) | −16.9 (−21.1, −12.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Bone alkaline phosphatase, ng/mL | −0.44 (−0.99, 0.11) | −0.27 (−0.90, 0.36) | −0.46 (−0.95, 0.04) | −1.28 (−2.08, −0.48) | 0.96 | 0.23 |

| Testosterone | ||||||

| Total testosterone, ng/dL | −2.9 (−46.8, 41.0) | −91.2 (−140.4, −42.0) | −165.1 (−206.1, −124.0) | −178.4 (−241.6, −115.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Free testosterone, pg/mL | 1.9 (−2.1, 6.0) | 6.9 (2.3, 11.4) | 15.1 (11.3, 18.9) | 17.9 (12.2, 23.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| SHBG, nmol/L | −2.4 (−6.1, 1.4) | −12.3 (−16.5, −8.2) | −22.7 (−26.1, −19.3) | −25.4 (−30.5, −20.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| LH, mIU/mL | −0.19 (−2.10, 1.71) | −0.27 (−2.37, 1.84) | 0.39 (−1.41, 2.18) | −1.15 (−3.79, 1.49) | 0.60 | 0.78 |

| Estradiol, pg/mL | −0.9 (−3.7, 1.9) | −1.4 (−4.6, 1.7) | −5.2 (−7.8, −2.6) | −7.3 (−11.2, −3.4) | 0.012 | 0.008 |

The data are point estimates and 95% CIs extracted from mixed model framework. P values for overall and for prespecified comparison of 5-mg vs placebo.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; LDL, low-density lipoprotein, LH, luteinizing hormone; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; RDW, red blood cell distribution width; NTx, N-telopeptide of collagen; PINP, procollagen I intact N-terminal; SHBG, sex hormone–binding globulin.

Other Patient-Reported Outcomes

There were no significant differences among study arms for Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite hormonal (P = 0.94) and sexual (P = 0.62) domains, FACIT -F (P = 0.54) and PANAS scores (Positive Affect: P = 0.83, Negative Affect: P = 0.08) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Estimated changes from baseline in patient-reported outcomes by treatment arm

| Variable | Placebo | 1 mg/day | 5 mg/day | 15 mg/day | P value (5 mg/day vs Placebo) | P value (any effect) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPSS | ||||||

| Symptom | −0.07 (−1.01, 0.87) | −1.48 (−2.59, −0.38) | 0.08 (−0.82, 0.99) | 0.13 (−1.31, 1.57) | 0.80 | 0.10 |

| Quality of Life Due to Urinary Symptoms | −0.02 (−0.25, 0.21) | −0.22 (−049, 0.06) | −0.02 (−0.25, 0.20) | −0.17 (−0.53, 0.18) | 0.99 | 0.58 |

| FACIT-F | −0.74 (−2.89, 1.41) | 1.52 (−0.98, 4.03) | −0.11 (−2.17, 1.95) | 0.47 (−2.83, 3.77) | 0.66 | 0.54 |

| PANAS | ||||||

| Positive Affect | 0.79 (−1.12, 2.70) | 0.57 (−1.63, 2.78) | 1.15 (−0.66, 2.95) | −0.45 (−3.36, 2.46) | 0.78 | 0.83 |

| Negative Affect | −1.52 (−2.62, −0.42) | −1.78 (−3.06, −0.50) | −0.14 (−1.19, 0.91) | −2.19 (−3.90, −0.49) | 0.06 | 0.08 |

Hormone Levels

OPK-88004 treatment was associated with a significant dose-related suppression of serum SHBG, total testosterone, and estradiol levels (Table 5). However, SARM administration was associated with a significant increase in free testosterone levels. (Table 5).

Other Laboratory Tests

There was statistically significant difference between arms in change from baseline in hematocrit (P = 0.040), hemoglobin (P = 0.026), and total testosterone levels (Table 5). The increases in hematocrit and hemoglobin levels were significantly greater in the 5-mg group than in the placebo group (P = 0.005 and P = 0.003, respectively), but the increase was small and none of the participants experienced erythrocytosis. There was statistically significant treatment effect on platelet counts (P < 0.001). However, changes in leukocyte count did not differ significantly among groups (Table 5).

OPK-88004 treatment was associated with a significant dose-related suppression of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels (Table 4: P < 0.001). Serum total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and triglycerides did not change significantly (Table 5).

There was a significantly greater decrease in fasting glucose levels between the placebo and 5-mg groups (P = 0.035) and overall (P = 0.003). (Table 5) However, the changes in insulin and homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) did not differ significantly across groups (P = 0.74 and P = 0.56, respectively).

Sensitivity Analyses

The effect modification due to the staged randomization during the trial was assessed by models adjusted for the 3 stages of randomization; the treatment effects did not differ among groups for any of the reported outcomes (not shown).

Discussion

The administration of a SARM was well tolerated in prostate cancer survivors with organ-confined low-grade disease who had undergone radical prostatectomy. Neither an interim analysis of the first 50 participants who were randomized to placebo, 1 mg, or 5 mg OPK-88004 and who had completed 12-weeks of intervention, nor the analysis of the entire cohort at the trial’s completion revealed evidence of biochemical recurrence in any subject. Lower urinary tract symptoms did not change significantly in any group. Only 1 participant, randomized to the 15-mg dose, experienced AST and ALT increase above the upper limit of normal, which returned to baseline after discontinuation of study medication. OPK-88004 treatment was associated with the expected decrease in serum HDL-cholesterol (39-43); total and LDL-cholesterol did not change significantly. Although there were modest dose-related increases in hemoglobin and hematocrit in participants treated with the OPK-88004, no subject developed erythrocytosis and the average change was less than that reported with testosterone replacement therapy (57).

Although this initial trial was neither large enough nor long enough to determine effects on clinical recurrence of prostate cancer, or clinically meaningful improvements in function or disability, OPK-88004 administration was efficacious in improving whole-body and appendicular lean body mass as well as reducing percent fat mass. The increase in whole-body lean mass averaged 1.6 and 2.0 kg in the 5- and 15-mg dose groups, respectively; as a reference for comparison, the gains in fat-free mass with replacement doses of testosterone in hypogonadal men have averaged ~1.6 kg (58). There were numerical increases in maximal voluntary strength in the leg press exercise, but these changes were not statistically significant. One possible reason for the inability to show changes in physical performance in spite of gains in lean body mass could be that the participants were physically fit and did not have functional limitations as indicated by their excellent baseline performance in the SPPB and other performance measures. Other studies that have recruited subjects with mild or no functional limitations at baseline also have generally failed to show improvements in measures of physical performance (59, 60). It is also possible that the 12-week intervention duration was insufficient to develop neuromuscular adaptations needed to translate strength gains into functional improvements. Men receiving androgen deprivation therapy, who are generally older, more functionally limited, and have substantially lower testosterone levels at baseline than the relatively healthy subjects recruited in this trial, may be more likely to show improvements in performance measures.

OPK-88004 treatment did not significantly improve sexual desire, erectile function, overall sexual activity, or fatigue, in spite of evidence that OPK-88004 was exerting androgenic effects in multiple organ systems (significant increases in whole-body and appendicular lean mass, hemoglobin and hematocrit, a reduction in percent fat mass, serum alkaline phosphatase, LH, and HDL-cholesterol levels). The lack of an effect on sexual function measures could be due to many reasons: (1) The study participants had severe ED, as indicated by an average erectile function domain score of 7.3 at baseline, which may not respond to androgen treatment alone; (2) OPK-88004 suppressed endogenous testosterone level; (3) it is generally believed that the beneficial effects of testosterone on sexual desire may require its conversion to estradiol (61). OPK-88004 does not undergo aromatization, although administration of dihydrotestosterone, which does not undergo direct aromatization to estradiol, has been shown to maintain sexual desire in older men (62); and (4) OPK-88004 was developed as muscle anabolic agent, and was not selected for promoting sexual function. It is possible that the baseline testosterone levels in the participants were not sufficiently low to observe the treatment effect and that the OPK-88004 might be more efficacious in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy who have very low endogenous testosterone levels.

SARM administration was associated with a marked suppression of SHBG and total testosterone levels. However, perhaps due to the marked suppression of SHBG, free testosterone levels showed a small increase rather than a decrease. Serum LH levels were not significantly suppressed.

Alanine aminotransferase gene expression is downregulated by castration and upregulated by androgen administration in the muscle and prostate but not in the liver of rodent (63). Increased transaminases could also be due to direct hepatotoxic effects that have been reported typically with alkylated androgens and nonsteroidal anti-androgens. We cannot be certain from the available information whether the increase in transaminase levels is due to androgen-induced increase in the transcription in nonhepatic tissues or a direct liver effect. Bilirubin uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase activity is a sexually dimorphic enzyme whose activity is regulated by testosterone and estradiol (64). Similarly, the suppression of alkaline phosphatase is a recognized androgen effect believed to be due to the suppression of bone turnover (65, 66). Androgen treatment is known to suppress alkaline phosphatase in hypogonadal men, and the decrease in alkaline phosphatase is associated with an increase in bone mineral density (65). Because the changes in bone-specific alkaline phosphatase were not statistically significant, we cannot be certain whether this represents a SARM effect on bone osteoblastic activity.

Similar to other oral androgens and SARMs (40-44), OPK-88004 was associated with HDL-cholesterol suppression, but LDL-cholesterol did not change. HDL-cholesterol has been negatively associated with the risk of coronary artery disease in epidemiological studies; however, pharmacologically induced changes in HDL-cholesterol have not been associated with changes in cardiovascular risk and the pharmaceutical efforts to develop drugs to increase HDL to prevent cardiovascular disease have proven unsuccessful (67). The increases in HDL-cholesterol due to overproduction of apolipoprotein A1, but not due to inhibition of HDL catabolism, have been found to be atheroprotective (68-70). The HDL-lowering effect of oral androgens has been attributed to the upregulation of scavenger receptor B1 (SR-B1) and the hepatic lipase (69, 70). Thus, clinical significance of the changes in HDL-cholesterol associated with oral androgens remains unclear. Long-term studies are needed to clarify the effects of SARM administration on cardiovascular risk.

This first randomized trial of a SARM in prostate cancer survivors has several strengths and some limitations. The trial has many attributes of good trial design: concealed randomized allocation of participants, blinding of the participants as well as the investigators, and parallel groups. The safety was assessed prospectively using a prespecified structured monitoring plan. We used several validated measures of sexual function, energy, and prostate cancer–specific HRQOL. The trial also had some limitations. To minimize risk to the participants in this first randomized trial in prostate cancer survivors, the intervention duration was limited to 12 weeks and the randomization was staged with the enrollment limited to lower doses initially. The trial was neither long enough nor large enough to assess risk of clinical recurrence. We selected a subset of prostate cancer survivors with a very low risk of disease recurrence. These findings should not be extrapolated to patients with high grade prostate cancer (Gleason 7 [4 + 3] or higher) or those in whom the cancer is not confined to the prostate or those who are treated with radiation therapy as their primary treatment.

Conclusions

The administration of a SARM in androgen-deficient men who had undergone radical prostatectomy for low-grade organ-confined prostate cancer was safe and not associated with PSA recurrence. OPK-88004 increased lean body mass and decreased fat mass but did not improve sexual symptoms or physical performance. The short-term safety data are reassuring and provide the rationale for investigating the efficacy of SARMs, such as the OPK-88004, that were developed for their preferential muscle and bone anabolic effects, among prostate cancer survivors with physical dysfunction, and for developing novel SARMs that preferentially improve sexual function.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The SARM-PC trial was funded by a research grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research (R01NR014502). Transition Therapeutics, Inc. provided the study drug and matching placebo at no cost to the trial. The implementation of the trial at the Boston site was supported partly by infrastructural resources of the Boston Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG31679) and the Harvard Clinical Translational Science Center (UL1TR002541).

Clinical Trial Information: ClinicalTrials.gov Registration No. NCT02499497.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AE

adverse event

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- AST

aspartate transaminase

- BMI

body mass index

- DISF-M-II

DeRogatis Inventory of Sexual Function for Men—II

- DSMB

data and safety monitoring board

- DXA

dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- FACIT-F

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Fatigue

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HOMA-IR

homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance

- HRQOL

health-related quality of life

- IIEF

International Index of Erectile Function

- IRB

institutional review board

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LH

luteinizing hormone

- MSHQ

Male Sexual Health Questionnaire

- NTx

N-telopeptide of type I collagen

- PANAS

Positive and Negative Affect Scale

- PDEI

phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor

- PINP

procollagen I intact N-terminal

- PSA

prostate-specific antigen

- SAE

serious adverse event

- SARM

selective androgen receptor modulator

- SHBG

sex hormone–binding globulin

- SPPB

Short Physical Performance Battery score

Additional Information

Disclosures: Dr Bhasin reports receiving research grant support from the NIA, NINR, NICHD, FNIH, AbbVie, Transition Therapeutics, Alivegen, and Metro International Biotechnology, Inc. These grants are managed by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. He has received consulting fees from OPKO Pharmaceuticals and POXEL, Inc, and has equity interest in FPT, LLC. Dr Burnett reports receiving research grants from Pfizer, and consulting fees from Astellas, Futura Medical, Eli Lilly and Co., Myriad Genetics, Novartis, and Reflexonic, LLC, and ownership interest in MHN Biotech. Other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(5):363-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sun F, Oyesanmi O, Fontanarosa J, et al. Therapies for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: Update of a 2008 Systematic Review [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2014. (Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 146.) Introduction. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK269309/. Accessed November 15, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hernandez DJ, Nielsen ME, Han M, et al. Natural history of pathologically organ-confined (pT2), Gleason score 6 or less, prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2008;72(1):172-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB, et al. Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1998;280(11):969-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burnett AL. Impotence after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2017;197(2S):S171-S172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(12):1250-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maliski SL, Kwan L, Elashoff D, Litwin MS. Symptom clusters related to treatment for prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(5):786-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maliski SL, Kwan L, Orecklin JR, Saigal CS, Litwin MS. Predictors of fatigue after treatment for prostate cancer. Urology. 2005;65(1):101-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stanford JL, Feng Z, Hamilton AS, et al. Urinary and sexual function after radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer: the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. JAMA. 2000;283(3):354-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khera M. Androgens and erectile function: a case for early androgen use in postprostatectomy hypogonadal men. J Sex Med. 2009;6 Suppl 3:234-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bhasin S, Brito JP, Cunningham GR, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(5):1715-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Helgason AR, Adolfsson J, Dickman P, Arver S, Fredrikson M, Steineck G. Factors associated with waning sexual function among elderly men and prostate cancer patients. J Urol. 1997;158(1):155-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Snyder PJ, Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, et al. ; Testosterone Trials Investigators . Effects of Testosterone Treatment in Older Men. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):611-624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brock G, Heiselman D, Maggi M, et al. Effect of testosterone solution 2% on testosterone concentration, sex drive and energy in hypogonadal men: results of a placebo controlled study. J Urol. 2016;195(3):699-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Steidle C, Schwartz S, Jacoby K, Sebree T, Smith T, Bachand R; North American AA2500 T Gel Study Group . AA2500 testosterone gel normalizes androgen levels in aging males with improvements in body composition and sexual function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(6):2673-2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morgentaler A, Caliber M. Safety of testosterone therapy in men with prostate cancer. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2019;18(11):1065-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khera M, Crawford D, Morales A, Salonia A, Morgentaler A. A new era of testosterone and prostate cancer: from physiology to clinical implications. Eur Urol. 2014;65(1):115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Auchus RJ, Sharifi N. Sex hormones and prostate cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2020;71:33-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berry PA, Maitland NJ, Collins AT. Androgen receptor signalling in prostate: effects of stromal factors on normal and cancer stem cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;288(1-2):30-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heinlein CA, Chang C. Androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Endocr Rev. 2004;25(2):276-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huggins C, Hodges CV. Studies on prostate cancer. I. The effects of castration, of estrogen, and of androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. Cancer Res. 1941;1(4):293-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fowler JE Jr, Whitmore WF Jr. The response of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate to exogenous testosterone. J Urol. 1981;126(3):372-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prout GR Jr, Brewer WR. Response of men with advanced prostatic carcinoma to exogenous administration of testosterone. Cancer. 1967;20(11):1871-1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roddam AW, Allen NE, Appleby P, Key TJ. Endogenous sex hormones and prostate cancer: a collaborative analysis of 18 prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:170-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marks LS, Mazer NA, Mostaghel E, et al. Effect of testosterone replacement therapy on prostate tissue in men with late-onset hypogonadism: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296(19):2351-2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Page ST, Lin DW, Mostaghel EA, et al. Persistent intraprostatic androgen concentrations after medical castration in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(10):3850-3856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaplan AL, Trinh QD, Sun M, et al. Testosterone replacement therapy following the diagnosis of prostate cancer: outcomes and utilization trends. J Sex Med. 2014;11(4):1063-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kardoust Parizi M, Abufaraj M, Fajkovic H, et al. Oncological safety of testosterone replacement therapy in prostate cancer survivors after definitive local therapy: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Urol Oncol. 2019;37(10):637-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Khera M, Grober ED, Najari B, et al. Testosterone replacement therapy following radical prostatectomy. J Sex Med. 2009;6(4):1165-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaufman JM, Graydon RJ. Androgen replacement after curative radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer in hypogonadal men. J Urol. 2004;172(3):920-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shahine H, Zanaty M, Zakaria AS, et al. Oncological safety and functional outcomes of testosterone replacement therapy in symptomatic adult-onset hypogonadal prostate cancer patients following robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. World J Urol. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00345-020-03475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Agarwal PK, Oefelein MG. Testosterone replacement therapy after primary treatment for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2005;173(2):533-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nabulsi O, Tal R, Gotto G, Narus J, Goldenberg L, Mulhall JP. Outcomes analysis of testosterone supplementation in hypogonadal men following radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2008;179(suppl):406 (abstract 1181). [Google Scholar]

- 34. Davila HH, Arison CN, Hall MK, Salup P, Lockhart JL, Carrion RE. Analysis of the PSA response after testosterone supplementation in patients who have previously received management for their localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2008;179(suppl):428 (abstract 1247). [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ory J, Flannigan R, Lundeen C, Huang JG, Pommerville P, Goldenberg SL. Testosterone therapy in patients with treated and untreated prostate cancer: impact on oncologic outcomes. J Urol. 2016;196(4):1082-1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gray H, Seltzer J, Talbert RL. Recurrence of prostate cancer in patients receiving testosterone supplementation for hypogonadism. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(7):536-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ruth KS, Day FR, Tyrrell J, et al. ; Endometrial Cancer Association Consortium . Using human genetics to understand the disease impacts of testosterone in men and women. Nat Med. 2020;26(2):252-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Swerdlow AJ, Schoemaker MJ, Higgins CD, Wright AF, Jacobs PA; UK Clinical Cytogenetics Group . Cancer incidence and mortality in men with Klinefelter syndrome: a cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(16):1204-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang C, Nieschlag E, Swerdloff R, et al. ; International Society of Andrology (ISA); International Society for the Study of Aging Male (ISSAM); European Association of Urology (EAU); European Academy of Andrology (EAA); American Society of Andrology (ASA) . Investigation, treatment, and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males: ISA, ISSAM, EAU, EAA, and ASA recommendations. J Androl. 2009;30(1):1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Narayanan R, Coss CC, Dalton JT. Development of selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs). Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;465:134-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bhasin S, Calof OM, Storer TW, et al. Drug insight: testosterone and selective androgen receptor modulators as anabolic therapies for chronic illness and aging. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2(3):146-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Basaria S, Collins L, Dillon EL, et al. The safety, pharmacokinetics, and effects of LGD-4033, a novel nonsteroidal oral, selective androgen receptor modulator, in healthy young men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(1):87-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dalton JT, Barnette KG, Bohl CE, et al. The selective androgen receptor modulator GTx-024 (enobosarm) improves lean body mass and physical function in healthy elderly men and postmenopausal women: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2011;2(3):153-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dobs AS, Boccia RV, Croot CC, et al. Effects of enobosarm on muscle wasting and physical function in patients with cancer: a double-blind, randomised controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):335-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Derogatis LR. The DeRogatis interview for sexual functioning (DISF/DISF-SR): an introductory report. J Sex Marital Ther. 1997;23(4):291-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cappelleri JC, Rosen RC, Smith MD, Mishra A, Osterloh IH. Diagnostic evaluation of the erectile function domain of the International Index of Erectile Function. Urology. 1999;54(2):346-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Acaster S, Dickerhoof R, DeBusk K, Bernard K, Strauss W, Allen LF. Qualitative and quantitative validation of the FACIT-fatigue scale in iron deficiency anemia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Swerdloff RS, Wang C, Cunningham G, et al. Long-term pharmacokinetics of transdermal testosterone gel in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(12):4500-4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang C, Harnett M, Dobs AS, Swerdloff RS. Pharmacokinetics and safety of long-acting testosterone undecanoate injections in hypogonadal men: an 84-week phase III clinical trial. J Androl. 2010;31(5):457-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cunningham GR, Ellenberg SS, Bhasin S, et al. Prostate-specific antigen levels during testosterone treatment of hypogonadal older men: data from a controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(12):6238-6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lee KK, Berman N, Alexander GM, Hull L, Swerdloff RS, Wang C. A simple self-report diary for assessing psychosexual function in hypogonadal men. J Androl. 2003;24(5):688-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rosen RC, Catania J, Pollack L, Althof S, O’Leary M, Seftel AD. Male Sexual Health Questionnaire (MSHQ): scale development and psychometric validation. Urology. 2004;64(4):777-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Szymanski KM, Wei JT, Dunn RL, Sanda MG. Development and validation of an abbreviated version of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite instrument for measuring health-related quality of life among prostate cancer survivors. Urology. 2010;76(5):1245-1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. LeBrasseur NK, Bhasin S, Miciek R, Storer TW. Tests of muscle strength and physical function: reliability and discrimination of performance in younger and older men and older men with mobility limitations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(11):2118-2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cookson MS, Aus G, Burnett AL, et al. Variation in the definition of biochemical recurrence in patients treated for localized prostate cancer: the American Urological Association Prostate Guidelines for Localized Prostate Cancer Update Panel report and recommendations for a standard in the reporting of surgical outcomes. J Urol. 2007;177(2):540-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ponce OJ, Spencer-Bonilla G, Alvarez-Villalobos N, et al. The efficacy and adverse events of testosterone replacement therapy in hypogonadal men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Isidori AM, Giannetta E, Greco EA, et al. Effects of testosterone on body composition, bone metabolism and serum lipid profile in middle-aged men: a meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2005;63(3):280-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Snyder PJ, Peachey H, Hannoush P, et al. Effect of testosterone treatment on body composition and muscle strength in men over 65 years of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(8):2647-2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Srinivas-Shankar U, Roberts SA, Connolly MJ, et al. Effects of testosterone on muscle strength, physical function, body composition, and quality of life in intermediate-frail and frail elderly men: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(2):639-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Finkelstein JS, Yu EW, Burnett-Bowie SA. Gonadal steroids and body composition, strength, and sexual function in men. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(25):2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sartorius GA, Ly LP, Handelsman DJ. Male sexual function can be maintained without aromatization: randomized placebo-controlled trial of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in healthy, older men for 24 months. J Sex Med. 2014;11(10):2562-2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Coss CC, Bauler M, Narayanan R, Miller DD, Dalton JT. Alanine aminotransferase regulation by androgens in non-hepatic tissues. Pharm Res. 2012;29(4):1046-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Muraca M, Fevery J. Influence of sex and sex steroids on bilirubin uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase activity of rat liver. Gastroenterology. 1984;87(2):308-313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dabaja AA, Bryson CF, Schlegel PN, Paduch DA. The effect of hypogonadism and testosterone-enhancing therapy on alkaline phosphatase and bone mineral density. BJU Int. 2015;115(3):480-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Brown JP, Albert C, Nassar BA, et al. Bone turnover markers in the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Clin Biochem. 2009;42(10-11):929-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Riaz H, Khan SU, Rahman H, et al. Effects of high-density lipoprotein targeting treatments on cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26(5):533-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Tang JJ, Srivastava RA, Krul ES, et al. In vivo regulation of apolipoprotein A-I gene expression by estradiol and testosterone occurs by different mechanisms in inbred strains of mice. J Lipid Res. 1991;32(10):1571-1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Krieger M. Charting the fate of the “good cholesterol”: identification and characterization of the high-density lipoprotein receptor SR-BI. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:523-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Langer C, Gansz B, Goepfert C, et al. Testosterone up-regulates scavenger receptor BI and stimulates cholesterol efflux from macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296(5):1051-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.