Abstract

Background

Many patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are asymptomatic. The prevalence of COVID-19 in orthopaedic populations will vary depending on the time and place where the sampling is performed. The idea that asymptomatic carriers play a role is generalizable but has not been studied in large populations of patients undergoing elective orthopaedic surgery. We therefore evaluated this topic in one large, metropolitan city in a state that had the ninth-most infections in the United States at the time this study was completed (June 2020). This work was based on a screening and testing protocol that required all patients to be tested for COVID-19 preoperatively.

Questions/purposes

(1) What is the prevalence of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection in patients planning to undergo orthopaedic surgery in one major city, in order to provide other surgeons with a framework for assessing COVID-19 rates in their healthcare system? (2) How did patients with positive test results for COVID-19 differ in terms of age, sex, and orthopaedic conditions? (3) What proportion of patients had complications treated, and how many patients had a symptomatic COVID-19 infection within 30 days of surgery (recognizing that some may have been missed and so our estimates of event rates will necessarily underestimate the frequency of this event)?

Methods

All adult patients scheduled for surgery at four facilities (two tertiary care hospitals, one orthopaedic specialty hospital, and one ambulatory surgery center) at a single institution in the Philadelphia metropolitan area from April 27, 2020 to June 12, 2020 were included in this study. A total of 1295 patients were screened for symptoms, exposure, temperature, and oxygen saturation via a standardized protocol before surgical scheduling; 1.5% (19 of 1295) were excluded because they had COVID-19 symptoms, exposure, or recent travel based on the initial screening questionnaire, leaving 98.5% (1276 of 1295) who underwent testing for COVID-19 preoperatively. All 1276 patients who passed the initial screening test underwent nasopharyngeal swabbing for COVID-19 via reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction before surgery. The mean age at the time of testing was 56 ± 16 years, and 53% (672 of 1276) were men. Eighty-seven percent (1106), 8% (103), and 5% (67) were tested via the Roche, Abbott, and Cepheid assays, respectively. All patients undergoing elective surgery were tested via the Roche assay, while those undergoing nonelective surgery received either the Abbott or Cepheid assay, based on availability. Patients with positive test results undergoing elective surgery had their procedures rescheduled, while patients scheduled for nonelective surgery underwent surgery regardless of their test results. Additionally, we reviewed the records of all patients at 30 days postoperatively for emergency room visits, readmissions, and COVID-19-related complications via electronic medical records and surgeon-reported complications. However, we had no method for definitively determining how many patients had complications, emergency department visits, or readmissions outside our system, so our event rate estimates for these endpoints are necessarily best-case estimates.

Results

A total of 0.5% (7 of 1276) of the patients tested positive for COVID-19: five via the Roche assay and two via the Abbott assay. Patients with positive test results were younger than those with negative results (39 ± 12 years versus 56 ± 16 years; p = 0.01). With the numbers available, we found no difference in the proportion of patients with positive test results for COVID-19 based on subspecialty area (examining the lowest and highest point estimates, respectively, we observed: trauma surgery [3%; 2 of 68 patients] versus hip and knee [0.3%; 1 of 401 patients], OR 12 [95% CI 1-135]; p = 0.06). No patients with negative preoperative test results for COVID-19 developed a symptomatic COVID-19 infection within 30 days postoperatively. Within 30 days of surgery, 0.9% (11 of 1276) of the patients presented to the emergency room, and 1.3% (16 of 1276) were readmitted for non-COVID-19-related complications. None of the patients with positive test results for COVID-19 preoperatively experienced complications. However, because some were likely treated outside our healthcare system, the actual percentages may be higher.

Conclusion

Because younger patients are more likely to be asymptomatic carriers of disease, surgeons should emphasize the importance of taking proper precautions to prevent virus exposure preoperatively. Because the rates of COVID-19 infection differ based on city and time, surgeons should monitor the local prevalence of disease to properly advise patients on the risk of COVID-19 exposure. Further investigation is required to assess the prevalence in the orthopaedic population in cities with larger COVID-19 burdens.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Introduction

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus emerged in Wuhan, China, resulting in the development of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [24]. The virus responsible for this pandemic is severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). Based on data from the preliminary wave of SARS-CoV-2 infections reported in China, the virus has a 3- to 7-day incubation period [10]. Although many patients with positive detection of SARS-CoV-2 are asymptomatic, they have viral loads comparable to that of symptomatic patients [6, 8, 12, 13, 15, 25]. Early recognition of infection, in both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, is crucial to prevent disease transmission. However, because of the large number of asymptomatic carriers and the lack of testing of these individuals, the true rate of asymptomatic infection is unknown [1, 7, 18].

Given the importance of orthopaedic surgery in providing pain relief and functional gains to patients, understanding the asymptomatic carrier rate is vital in decreasing SARS-CoV-2 exposure in healthcare systems. Airway management during surgery can result in the generation of aerosols, which can increase SARS-CoV-2 exposure among healthcare workers [2, 21]. Additionally, patients with positive test results for COVID-19 have increased perioperative respiratory complications and a 19% risk of death [5]. Therefore, identifying patients with COVID-19 is imperative to minimize complications, protect healthcare workers from unnecessary SARS-CoV-2 exposure, and control the spread of infection. Furthermore, although the rates of COVID-19 and asymptomatic carriers vary by location and time, it is important for providers to be aware of the prevalence of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection in their patient population in order to understand the impact on these patients entering their healthcare system. At the time of this study, Pennsylvania had the ninth-most reported cases of COVID-19 and continued to be in the top 10 as of late 2020. Our institution adopted a protocol in which all patients were screened for symptoms and tested for COVID-19 preoperatively to minimize the risk of SARS-CoV-2 exposure and complications; thus, we used this as the setting to ascertain the risk of asymptomatic carriage of COVID-19.

In this retrospective study, we asked, (1) What is the prevalence of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection in patients planning to undergo orthopaedic surgery in one major city, in order to provide other surgeons with a framework for assessing COVID-19 rates in their healthcare system? (2) How did patients with positive test results for COVID-19 differ in terms of age, sex, and orthopaedic conditions? (3) What proportion of patients had complications treated, and how many patients had a symptomatic COVID-19 infection within 30 days of surgery (recognizing that some may have been missed and so our estimates of event rates will necessarily underestimate the frequency of this event)?

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Setting

We recorded data longitudinally, and we performed the data analysis retrospectively. All adult patients (older than 18 years) scheduled for either elective or nonelective surgery at four facilities (two tertiary care hospitals, one orthopaedic specialty hospital, and one ambulatory surgery center) at a single institution in the Philadelphia metropolitan area from April 27, 2020 until June 12, 2020 were included in this study. This period correlated with Pennsylvania allowing elective surgery (April 27, 2020) and a week beyond when the state began Phase 1 reopening (June 5, 2020).

Patients

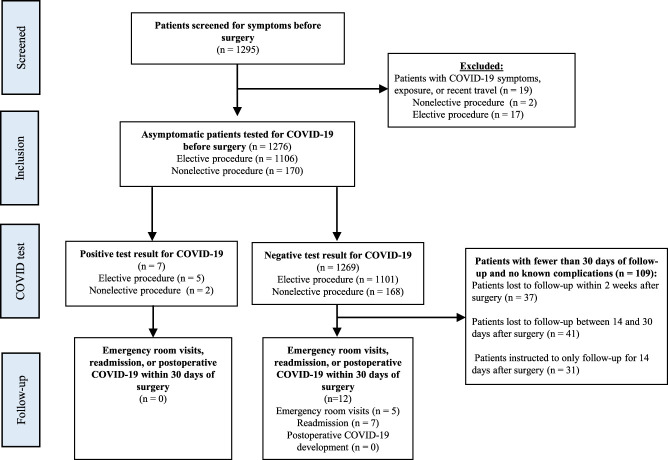

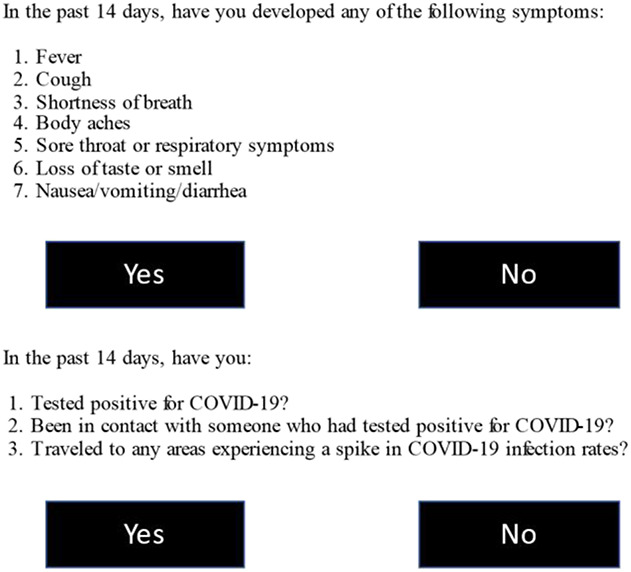

Between April 20, 2020 and June 12, 2020, 1295 patients were scheduled for surgery. All patients were screened for symptoms, exposure, temperature, and oxygen saturation via a standardized protocol before surgical scheduling (Fig. 1) [14]. A total of 1.5% (19 of 1295) were excluded because they had COVID-19 symptoms, exposure, or recent travel based on an initial screening questionnaire, leaving 98.5% (1276 of 1295) who underwent testing for SARS-CoV-2 preoperatively (Fig. 2). Patients scheduled for elective surgery with positive test results had their surgery canceled and were asked to quarantine. These patients needed to be asymptomatic for 2 weeks and have a negative test result for COVID-19 twice before surgery. Patients who presented to the hospital for nonelective surgery without COVID-19 symptoms underwent surgery regardless of their COVID-19 status. However, for patients who tested positive for COVID-19, extra precautions were taken during surgery to decrease the risk of hospital staff exposure to COVID-19. Surgical procedures classified as Priority A (emergency) or Priority B (urgent) by Massey et al. [11] were considered nonelective for this study.

Fig. 1.

The preoperative COVID-19 screening questionnaire for COVID-19 symptoms and exposure is shown.

Fig. 2.

This flowchart shows the study population screened and tested for COVID-19 preoperatively.

Testing

Patients underwent nasopharyngeal swabbing for SARS-CoV-2 via reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction using the Cobas SARS-CoV-2 assay (Roche Diagnostics), Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 assay (Cepheid), or ID Now SARS-CoV-2 assay (Abbott) preoperatively. The Cobas, Xpert Xpress, and ID Now assays can determine SARS-CoV-2 status in 3.5 hours, 45 minutes, and 13 minutes, respectively [3]. The Cobas assay was performed 36 to 72 hours before all elective surgeries. The Xpert Xpress and ID Now assays were performed within 72 hours of surgery for hospitalized patients undergoing nonelective surgery. Procop et al. [17] found the sensitivities for the Cobas, Xpert Xpress, and ID Now tests were 96.5%, 97.6%, and 83.3%, respectively, and the false-negative rate of the Cobas, Xpert Xpress, and ID Now were 3.5%, 2.4%, and 16.7% respectively. At the time of our study, all three diagnostic test systems were approved by the FDA for emergency use authorizations. All patients scheduled to undergo elective surgery underwent testing with the Roche assay. Patients in the tertiary care hospital who were scheduled for nonelective surgery underwent testing via the Abbott assay or Cepheid assay based on availability.

Samples were collected according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendations. Over 46 days, 1276 asymptomatic patients who passed the initial screening were scheduled to undergo orthopaedic surgery and underwent preoperative testing for COVID-19. The mean age at the time of testing was 56 ± 16 years, and 53% (672) were men. Eighty-seven percent (1106) of patients underwent testing via the Roche assay, 8% (103) underwent testing via the Abbott assay, and 5% (67) underwent testing using the Cepheid assay. All asymptomatic patients with positive test results for COVID-19 were contacted 3 to 6 weeks afterward to determine whether they developed symptoms at any time. In addition, we reviewed the records of all patients at 30 days postoperatively for emergency room visits, readmissions, and COVID-19-related complications via electronic medical records and surgeon-reported complications. Furthermore, our institution’s quality department collects data on readmission and emergency room visit rates at outside hospital networks via the HealthShare Exchange database. The quality department’s data were reviewed to accurately report emergency room visits, readmission, and COVID-19 infections. Ninety-nine percent (1262 of 1276) of the patients lived within 50 miles of our institution, where many of the surrounding hospitals participate in the HealthShare Exchange database. Additionally, at each postoperative visit, all patients were screened for COVID-19 symptoms via a questionnaire and underwent a temperature check. Of the 1276 patients included in this study, 97% (1239 of 1276) had at least 14 days of follow-up and 91% (1167 of 1276) had at least 30 days of follow-up with their surgeons.

Ethical Approval

This study was reviewed by Thomas Jefferson University and was determined to be exempt from institutional review board approval (IRB number 20E.492).

Statistical Analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis of the data. We assessed outcomes using chi-square and independent t-tests for parametric data and Fisher exact tests and Mann-Whitney U tests when data were nonparametric or normally distributed. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Science Version 26 (IBM Corp). Statistical significance was defined as p value < 0.05.

Results

Prevalence of COVID-19 Among Asymptomatic Patients Undergoing Surgery

A total of 0.5% of the patients in this series (7 of 1276) had positive test results for SARS-CoV-2. Five underwent testing via the Roche assay, and two underwent testing via the Abbott assay (Table 1). Four of these patients did not develop symptoms associated with COVID-19 during the surveillance period, two reported 1 to 2 days of mild rhinorrhea, and one developed more severe COVID-19 symptoms (fever, sore throat, fatigue, headache, and diarrhea) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with positive test results for COVID-19 preoperatively

| Patient number | Age in years | Sex, M/F | BMI in kg/m2 | Division | Location | Positive test result |

| 1 | 50 | F | 32 | Hip and knee | Orthopaedic specialty hospital | Roche |

| 2 | 31 | F | 30 | Trauma | Tertiary care hospital | Abbott |

| 3 | 49 | F | 34 | Foot and ankle | Ambulatory surgery center | Roche |

| 4 | 35 | M | 35 | Shoulder and elbow | Ambulatory surgery center | Roche |

| 5 | 53 | M | 28 | Spine | Tertiary care hospital | Roche |

| 6 | 30 | M | 31 | Spine | Tertiary care hospital | Roche |

| 7 | 22 | M | 25 | Trauma | Tertiary care hospital | Abbott |

Table 2.

Symptoms of patients with positive test results for COVID-19 preoperatively

| Patient number | Symptoms | Length of time with symptoms in days | Method tested | Number of days between first positive COVID-19 test result and first negative COVID-19 test result in days |

| 1 | None | Roche | 28 | |

| 2 | None | Abbott | 26 | |

| 3 | Clear rhinorrhea | 1 | Roche | 17 |

| 4 | Fever, sore throat, fatigue, headache, diarrhea | 7 | Roche | 21 |

| 5 | None | Roche | 29 | |

| 6 | Clear rhinorrhea | 2 | Roche | 36 |

| 7 | None (subsequent use of a ventilator after trauma) | Abbott | 10 |

Factors Associated with Positive COVID-19 Test Results

Patients with positive test results were younger than those with negative results (39 ± 12 years [95% CI, 30-48] versus 56 ± 16 years [95% CI, 55-57]; p = 0.01) (Table 3). The age of patients with positive test results ranged from 22 to 50 years. There was no difference in sex between those with positive test results and those with negative results (OR 1.2; 95% CI 0.3-5.4; p > 0.99). The percentage of asymptomatic patients with positive test results for COVID-19 before elective surgery was 0.5% (5 of 1106) compared with 1.2% (2 of 170) among those before nonelective surgery (p = 0.24). With the numbers available, we found no difference in the proportion of patients with positive results for COVID-19 based on subspecialty area (examining the lowest and highest point estimates, respectively, we observed: trauma surgery [3%; 2 of 68 patients] versus hip and knee [0.3%; 1 of 401 patients], OR 12 [95% CI 1-135]; p =0.06). With the numbers available, we found no difference between asymptomatic patients with positive test results at the tertiary care hospitals (0.8%; 4 of 501), orthopaedic specialty hospital (0.2%; 1 of 484), and ambulatory surgery center (0.7%; 2 of 291; p = 0.42).

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients tested for COVID-19

| Demographics | COVID-19 status | ||

| Negative (n = 1269) | Positive (n = 7) | p value | |

| Age in years | 56 ± 16 | 39 ± 12 | 0.01 |

| Sex, M/F | 601 F, 668 M | 3 F, 4 M | > 0.99 |

| BMI in kg/m2 | 29 ± 6 | 31 ± 3 | 0.28 |

| Surgery classification | 0.23 | ||

| Elective | 87% (1101) | 71% (5) | |

| Nonelectivea | 13% (168) | 29% (2) | |

| Division | |||

| Foot and ankle | 9% (117) | 14% (1) | |

| Hand | 10% (124) | 0% (0) | |

| Hip and knee | 31% (399) | 14% (1) | |

| Shoulder and elbow | 11% (141) | 14% (1) | |

| Spine | 20% (249) | 29% (2) | |

| Sports | 11% (139) | 0% (0) | |

| Trauma or acute fractures | 5% (66) | 29% (2) | |

| Tumor | 3% (34) | 0% (0) | |

| Location of surgery | 0.42 | ||

| Tertiary care hospitals | 39% (497) | 57% (4) | |

| Orthopaedic specialty hospital | 38% (483) | 14% (1) | |

| Surgery center | 23% (289) | 29% (2) | |

Nonelective procedures: all procedures classified as Priority A (emergency) or Priority B (urgent) by Massey et al. [11]. Data presented as mean ± SD or % (n).

Complications Within 30 Days of Surgery

Two percent of the patients (27 of 1276) presented to the emergency room or were readmitted within 30 days of surgery (Table 4). However, because some were likely treated outside our healthcare system, the actual percentages may be higher. None of these patients presented with shortness of breath or pneumonia. Furthermore, no patients with positive test results for COVID-19 developed symptomatic COVID-19 or surgical complications within 30 days of surgery.

Table 4.

Complications within 30 days of surgery

| Patient number | Division | ED visit versus readmission | Complications | Postoperative day |

| 1 | Hip and knee | Readmission | Deep wound infection | 20 |

| 2 | Hip and knee | Readmission | Deep wound infection | 24 |

| 3 | Hip and knee | Readmission | Wound drainage | 9 |

| 4 | Hip and knee | ED visit | Pain | 11 |

| 5 | Hip and knee | ED visit | Fever | 29 |

| 6 | Hip and knee | Readmission | Periprosthetic fracture | 21 |

| 7 | Hip and knee | ED visit | Calf swelling | 7 |

| 8 | Hip and knee | ED visit | Syncope | 0 |

| 9 | Hip and knee | Readmission | Syncope | 22 |

| 10 | Hip and knee | Readmission | Ambulatory dysfunction | 10 |

| 11 | Hip and knee | ED visit | Atrial fibrillation | 2 |

| 12 | Shoulder and elbow | Readmission | Dislocation | 15 |

| 13 | Spine | ED visit | Pain | 2 |

| 14 | Spine | ED visit | Pain | 2 |

| 15 | Spine | Readmission | UTI | 14 |

| 16 | Spine | ED visit | UTI | 11 |

| 17 | Spine | ED visit | Colitis | 14 |

| 18 | Spine | Readmission | UTI | 8 |

| 19 | Spine | ED visit | Calf pain and swelling | 26 |

| 20 | Spine | Readmission | Acute renal failure | 11 |

| 21 | Spine | Readmission | Hematoma | 11 |

| 22 | Spine | Readmission | Change in mental status, hyponatremia | 4 |

| 23 | Spine | Readmission | Disc re-herniation | 28 |

| 24 | Spine | ED visit | Deep vein thrombosis | 8 |

| 25 | Spine | Readmission | Superficial wound infection | 27 |

| 26 | Spine | Readmission | Superficial wound infection | 25 |

| 27 | Spine | Readmission | Pulmonary embolism | 14 |

ED = emergency department; UTI = urinary tract infection.

Discussion

As the pandemic continues into 2021, the number of patients with COVID-19 entering health systems with plans to undergo orthopaedic procedures will continue to pose exposure risks to the healthcare system and the patients treated there. To provide patients with pain relief and functional improvements through orthopaedic surgery, it is vital to properly identify asymptomatic patients with COVID-19, because many patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 are asymptomatic but carry viral loads comparable to those of symptomatic patients [6, 8, 12, 13, 25]. The prevalence of asymptomatic patients undergoing orthopaedic surgical procedures remains unclear. Although the data in this study are specific to one time and location, this information can be used by surgeons to develop a framework for assessing the proportion of asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 in their patient populations. This study showed that in a large United States city with a high incidence of COVID-19 infections, the overall prevalence of asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 scheduled for orthopaedic surgery was very low, and no patients developed symptomatic COVID-19 postoperatively. Through proper screening and testing of all patients preoperatively, alongside appropriate use of personal protective equipment and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines, we believe orthopaedic procedures can be performed with a minimal risk of SARS-CoV-2 exposure, particularly in cities with a COVID-19 disease burden similar to or less than that of Philadelphia.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the prevalence of COVID-19 differs based on location and time. Therefore, the prevalence of COVID-19 in our patients differs from that of other cities. However, many findings of this study can be applied to the general orthopaedic population, particularly in states with lower disease burdens. This study indicates that the overall prevalence of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection in the orthopaedic population is low. Surgeons, particularly in cities with a lower COVID-19 disease burden, can use this study in other locations to create a framework for assessing the prevalence of asymptomatic COVID-19 among their patients to better inform their patients on the current rates of COVID-19. The results and conclusions of this study will likely differ in larger cities or cities with much higher rates of COVID-19.

Second, the true prevalence of COVID-19 is likely higher in the general population than reported in our study because patients with mild symptoms were not scheduled for surgery. Third, this study was performed at an institution where more than 85% of surgical procedures were elective. Although there was no difference in the rates of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection between elective and non-elective procedures, we speculate that at institutions with a much higher proportion of urgent and emergent procedures (such as trauma surgery), the incidence of COVID-19 may more closely reflect the prevalence of COVID-19 in the general population than the rates seen in our study.

Fourth, the sample size of patients with positive test results for COVID-19 was smaller than anticipated, making it difficult to draw meaningful statistical conclusions on some comparisons. However, we noticed that younger patients had a higher likelihood of asymptomatic carriage, which is an important finding. Fifth, postoperative, symptomatic COVID-19 infection was used to assess for iatrogenic COVID-19 infection. Because polymerase chain reaction testing is not commonly performed for asymptomatic patients, this study was only able to assess for the development of symptomatic COVID-19 via screening questionnaires at each postoperative visit and reviewing electronic medical record data regarding emergency department visits and readmission. Therefore, patients may have developed asymptomatic COVID-19 infection that was missed in this study.

We acknowledge that the Roche, Abbott, and Cepheid assays have varying false-positive and false-negative rates, which may have affected the reliability of our data. Some patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection may have been missed (false-negative), while some patients who had positive test results for SARS-CoV-2 may not have been truly infected and may have fallen victim to errors in molecular testing [3, 20]. At the time of this study, all three studies were approved by the FDA for emergency use authorizations and their false-negative rates were unknown. In this study, it is possible that a higher percentage of patients had asymptomatic COVID-19 infection than reported, especially in patients undergoing urgent surgery. It is vital for providers to test patients using the most accurate SARS-CoV-2 assays available. The rates of COVID-19 seen in our study may differ greatly from those of an institution that only uses the ID Now test. Additionally, preoperatively, patients completed a self-reported questionnaire denying symptoms, creating the possibility of false reporting that might have affected the results.

Prevalence of COVID-19 Among Asymptomatic Patients Undergoing Surgery

We found that only 0.5% of asymptomatic patients (7 of 1276) undergoing orthopaedic surgery had positive test results for COVID-19 at a single institution in the Philadelphia metropolitan area from April 27, 2020 to June 12, 2020. The overall proportion of positive COVID-19 test results in this study was very low, indicating that the overall prevalence of asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 in this orthopaedic population was low and testing is an effective method for reducing any additional unnecessary COVID-19 exposure. Patients should be made aware that although the risk of SARS-CoV-2 exposure from orthopaedic surgery is minimized because of preoperative testing and the use of personal protective equipment, there is still a risk of COVID-19 exposure. The risk of COVID-19 exposure will fluctuate based on the local prevalence of COVID-19. Therefore, because of false-negative test results, it is crucial for providers to monitor the local prevalence of disease to properly advise patients on the risk of COVID-19 exposure [17]. Furthermore, patients seeking elective orthopaedic surgery should be counseled to take proper precautions to prevent COVID-19 infection preoperatively, especially given possible false-negative test results. Because the rates of COVID-19 infection differ based on city and time, a further investigation is required to assess the prevalence in the orthopaedic population in cities with more-severe COVID-19 burdens.

Factors Associated with Positive COVID-19 Test Results

Patients with positive test results for COVID-19 were younger than those with negative results. Although younger patients have a higher prevalence of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection, preoperative testing is an effective method of preventing young, asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 from entering the healthcare system [4, 19]. Previous studies have also shown that younger individuals are more likely to have asymptomatic COVID-19 than older individuals [8, 9, 22, 23]. Because symptomatic infection occurs more often in older individuals, these patients may have canceled their surgery or may not currently be considering undergoing elective operations. There was no difference in the rates of asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 scheduled for elective surgery and those scheduled for nonelective surgery (0.5% versus 1.2%; p = 0.24). However, the small sample size of patients with positive test results for COVID-19 was smaller than anticipated, making it difficult to draw meaningful statistical conclusions. Future studies are needed to compare the rates of asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 between elective and nonelective procedures.

Complications Within 30 Days of Surgery

Complications within 30 days of surgery were uncommon in this series; however, we recognize that our estimates are necessarily on the low side—perhaps the very low side—because we do not know how many patients may have been treated outside our healthcare system. No patients had symptomatic COVID-19 after surgery, although we realize that patients with asymptomatic COVID-19 infection may have been missed. However, we speculate that the continual use of personal protective equipment was an important factor in minimizing SARS-CoV-2 exposure in patients entering healthcare systems for orthopaedic surgery. This is critical because the development of COVID-19 infection postoperatively can lead to devastating complications [14, 16].

Conclusion

The prevalence of asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 in this study was very small. With proper screening of patients, we believe orthopaedic surgery can be performed with a minimal risk of COVID-19 exposure if proper precautions are maintained. Because the prevalence of COVID-19 infections varies based on location and time, it remains critical for providers to actively monitor the local prevalence of disease to properly advise patients on the risk of COVID-19 exposure. Surgeons should be aware that younger patients are more likely to be asymptomatic carriers of disease; thus, surgeons should emphasize to their patients that proper precautions should be taken to prevent viral exposure preoperatively. Finally, with the introduction of a vaccine, the number of patients with COVID-19 will likely decrease. However, testing should continue in order to prevent unnecessary exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in the healthcare system.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that neither he nor she, nor any member of his or her immediate family, has funding or commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA approval status, of any drug or device before clinical use.

This study was reviewed by Thomas Jefferson University and was determined to be exempt from institutional review board approval (IRB #20E.492).

Contributor Information

Michael J. Gutman, Email: mxg263@jefferson.edu.

Manan S. Patel, Email: msp131@med.miami.edu.

Christina Vannello, Email: Chris.Vannello@rothmanortho.com.

Mark D. Lazarus, Email: shoulderdoc@comcast.net.

Javad Parvizi, Email: Javad.Parvizi@rothmanortho.com.

Alexander R. Vaccaro, Email: alex.vaccaro@rothmanortho.com.

References

- 1.Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. Presumed asymtomatic carrier tranmission of COVID 19. JAMA. 2020;323:1406-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balakrishnan K, Schechtman S, Hogikyan ND, Teoh AYB, McGrath B, Brenner MJ. COVID-19 pandemic: what every otolaryngologist–head and neck surgeon needs to know for safe airway management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;162:804-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basu A, Zinger T, Inglima K, et al. Performance of Abbott ID NOW COVID-19 rapid nucleic acid amplification test in nasopharyngeal swabs transported in viral media and dry nasal swabs in a New York City academic institution. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:e01136-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumberg TJ, Adler AC, Lin EE, et al. Universal screening for COVID-19 in children undergoing orthopaedic surgery: a multicenter report. J Pediatr Orthop . 2020;40:e990-e993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.COVIDSurg Collaborative. Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet. 2020;396: 27-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day M. COVID-19: four fifths of cases are asymptomatic, China figures indicate. BMJ. 2020;369:m1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furukawa NW, Brooks JT, Sobel J. Evidence supporting transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 while presymptomatic or asymptomatic. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:e201595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao Z, Xu Y, Sun C, et al. A systematic review of asymptomatic infections with COVID-19. J Microbiol Immunol Infect . Published online May 15, 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Hu Z, Song C, Xu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 24 asymptomatic infections with COVID-19 screened among close contacts in Nanjing, China. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63:706-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199-1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Massey PA, McClary K, Zhang AS, Savoie FH, Barton RS. Orthopaedic surgical selection and inpatient paradigms during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28:436-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mizumoto K, Kagaya K, Zarebski A, Chowell G. Estimating the asymptomatic proportion of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship, Yokohama, Japan, 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:2000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishiura H, Kobayashi T, Miyama T, et al. Estimation of the asymptomatic ratio of novel coronavirus infections (COVID-19). Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:154-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parvizi J, Gehrke T, Krueger CA, et al. Resuming elective orthopaedic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2020;102:1205-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel MS, Gutman MJ, Abboud JA. Orthopaedic considerations following COVID-19: lessons from the 2003 sars outbreak. JBJS Rev . 2020;8:e2000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price A, Shearman AD, Hamilton TW, Alvand A, Kendrick B. 30-day outcome after orthopaedic surgery in patients assessed as negative for COVID-19 at the time of surgery during the peak of the pandemic. Bone Jt Open. 2020;1:474-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Procop GW, Brock JE, Reineks EZ, et al. A comparison of five SARS-CoV-2 molecular assays with clinical correlations. Am J Clin Pathol . 2021;155:69-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:970-971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singer JS, Cheng EM, Murad DA, et al. Low prevalence (0.13%) of COVID-19 infection in asymptomatic pre-operative/pre-procedure patients at a large, academic medical center informs approaches to perioperative care. Surgery. 2020;168:980-986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smithgall MC, Scherberkova I, Whittier S, Green DA. Comparison of Cepheid Xpert Xpress and Abbott ID Now to Roche cobas for the rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobti A, Fathi M, Mokhtar MA, et al. Aerosol generating procedures in trauma and orthopaedics in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic; what do we know? Surgeon . Published online August 13, 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.surge.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Wang Y, Liu Y, Liu L, Wang X, Luo N, Ling L. Clinical outcome of 55 asymptomatic cases at the time of hospital admission infected with SARS-Coronavirus-2 in Shenzhen, China. J Infect Dis. 2020;221:1770-17740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang R, Gui X, Xiong Y. Comparison of clinical characteristics of patients with asymptomatic vs symptomatic coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2014310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727-733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1177-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]