Abstract

Background

The American Orthopaedic Association (AOA) released the standardized letter of recommendation (SLOR) form to provide standardized information to evaluators of orthopaedic residency applicants. The SLOR associates numerical data to an applicant’s letter of recommendation. However, it remains unclear whether the new letter form effectively distinguishes among orthopaedic applicants, for whom letters are perceived to suffer from “grade inflation.” In addition, it is unknown whether letters from more experienced faculty members differ in important ways from those written by less experienced faculty.

Questions/purposes

(1) What proportion of SLOR recipients were rated in the top 10th percentile and top one-third of the applicant pool? (2) Did letters from program leaders (program directors and department chairs) demonstrate lower aggregate SLOR scores compared with letters written by other faculty members? (3) Did letters from away rotation program leaders demonstrate lower aggregate SLOR scores compared with letters written by faculty at the applicant’s home institution?

Methods

This was a retrospective, single institution study examining 559 applications from the 2018 orthopaedic match. Inclusion criteria were all applications submitted to this residency. Exclusion criteria included all letters without an associated SLOR. In all, 1852 letters were received; of these, 26% (476) were excluded, and 74% (1376) were analyzed for SLOR data. We excluded 12% (169 of 1376) of letters that did not include a final summative score. Program leaders were defined as orthopaedic chairs and program directors. Away rotation letters were defined as letters written by faculty during an applicant’s away rotation. Our study questions were answered accounting for each subcategory on the SLOR (scale 1-10) and the final ranking (scale 1-5) to form an aggregated score from the SLOR form for each letter. All SLOR questions were included in the creation of these scores. Correlations between program leaders and other faculty letter writers were assessed using a chi-square test. We considered a 1-point difference on 5-point scales to be a clinically important difference and a 2-point difference on 10-point scales to be clinically important.

Results

We found that 36% (437 of 1207) of the letters we reviewed indicated the candidate was in the top 10th percentile of all applicants evaluated, and 51% (619 of 1207) of the letters we reviewed indicated the candidate was in the top one-third of all applicants evaluated. We found no clinically important difference between program leaders and other faculty members in terms of summative scores on the SLOR (1.9 ± 0.7 versus 1.7 ± 0.7, mean difference -0.2 [95% CI -0.3 to 0.1]; p < 0.001). We also found no clinically important difference between home program letter writers and away program letter writers in terms of the mean summative scores (1.9 ± 0.7 versus 1.7 ± 0.7, mean difference 0.2; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

In light of these discoveries, programs should examine the data obtained from SLOR forms carefully. SLOR scores skew very positively, which may benefit weaker applicants and harm stronger applicants. Program leaders give summative scores that do not differ substantially from junior faculty, suggesting there is no important difference in grade inflation between these faculty types, and as such, there is no strong need to adjust scores by faculty level. Likewise, away rotation letter writers’ summative scores were not substantially different from those of home institution letters writers, indicating that there is no need to adjust scores between these groups either. Based on these findings, we should interpret letters with the understanding that overall there is substantial grade inflation. However, while weight used to be given to letters written by senior faculty members and those obtained on away rotations, we should now examine them equally, rather than trying to adjust them for overly high or low scores.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Introduction

The application process for orthopaedic residency training is a challenging path for highly competitive medical students [5]. Many obstacles may impede admission, including United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) testing, medical school grades, interviews, and letters of recommendation. The American Orthopaedic Association (AOA) and Council of Orthopaedic Residency Directors (CORD) released a standardized letter of recommendation (SLOR) form for orthopaedic residency applicants in 2017. According to the AOA, the intent of the SLOR is to “provide residency programs a more concise perspective on a candidate than what is traditionally outlined in a letter [1].” Letter writers (evaluators) are asked to forgo writing a personalized letter in exchange for completing this form. The letter of recommendation is an important tool used by residency programs to differentiate highly qualified applicants in a competitive field.

Although the SLOR form makes the process more uniform for evaluators and for those evaluating applications, no studies haved validated this form or have reported the consistency of usage across programs or other specialties using similar evaluation tools [3, 6, 8]. Anecdotally, orthopaedic letters of recommendation were prone to skew positively before the SLOR, and they typically and tended to contain very few poor evaluations. It is unknown whether the SLOR form has helped to reduce this bias. In addition, letters are written by a wide range of faculty members, from very inexperienced instructors to senior faculty and program leaders (like program directors and department chairs). The degree to which letters of recommendation may or may not skew positively as a function of faculty member experience is unknown. Likewise, the degree to which “home” and “away” rotation faculty differ also is unknown. More information on these factors can help letter readers interpret what they read in an era of grade inflation.

We therefore asked: (1) What proportion of SLOR recipients were rated in the top 10th percentile and top one-third of the applicant pool? (2) Did letters from program leaders (program directors and department chairs) demonstrate lower aggregate SLOR scores compared with letters written by other faculty members? (3) Did letters from away rotation program leaders demonstrate lower aggregate SLOR scores compared with letters written by faculty at the applicant’s home institution?

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This retrospective, descriptive observational study was performed at one allopathic orthopaedic residency program (Prisma Health-Midlands University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA) for the 2018 National Resident Matching Program (NRMP).

Participants and Descriptive Data

We considered all 559 applications in the applicant pool of medical students for the year 2018 and all 1852 letters as provided as part of their application packets. We excluded withdrawn applications and letters without an associated SLOR because we could not obtain an associated quantitative score for comparison with letters that included a SLOR. This resulted in excluding 26% (476 of 1852), leaving 74% (1376 of 1852) for SLOR data analysis. We excluded 12% (169 of 1376) of letters that did not include a final summative score.

In our study, 759 program leaders wrote letters of recommendation; 60% (455) were penned by department chairs and 40% (304) by program directors. Further, 65% (889 of 1376) of evaluated letters were written by program leaders and 35% (487 of 1376) were composed by other faculty. Of the evaluated letters, 58% (803 of 1376) were from a student’s home institution. Median (range) step 1 score was 241 (189 to 279). Students were AOA recognized in 26% (360 of 1376) of applications and were Gold Humanism Award recipients in 9% (129 of 1376).

Primary and Secondary Study Outcomes

The primary outcome for this study was the proportion of SLOR recipients rated in the top 10th percentile and the proportion ranked in top one-third of the applicant pool in their summative score. The summative score was on a 5-point scale. Summative scores were separated into ranked to match, top one-third, middle one-third, lower one-third, and not a fit. After examining each SLOR, we identified applicants who received letters with this criteria.

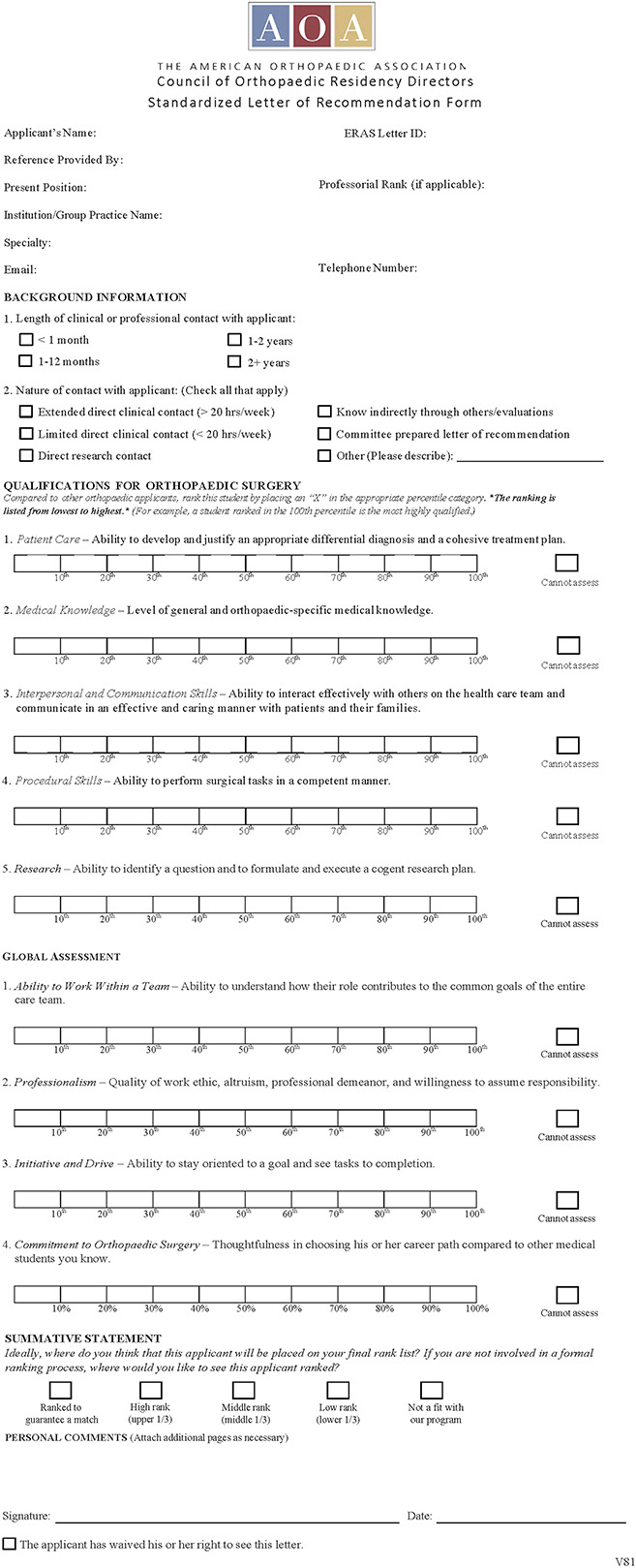

The secondary outcome was twofold. We compared letters from program leaders (program directors and chairs) with letters written by other faculty members to see if there were lower aggregate scores. We then compared letters from away rotation program leaders with letters written by faculty at the applicant’s home institution to see if there were lower aggregate and summative scores. Each letter writer gave a summative score as described above. We also calculated an aggregate score across patient care, medical knowledge, interpersonal skills, procedure, research skills, teamwork, professionalism, commitment, initiative, and the summative score. The summative score was on a 5-point scale and the aggregate scores were on a 10-point scale. As such, we doubled the summative score when computing the aggregate score. For each person, only those scores that had been collected were used, and then each aggregate score was scaled by the number of scores collected. The SLOR form (Fig. 1), demonstrates these 10 categories and the questions assigned to letter writers [1].

Fig. 1.

Blank sample of the American Orthopaedic Association Council of Residency Directors Standardized Letter of Recommendation form. Reprinted with permission from the American Orthopaedic Association.

Sources of Bias

Several letters reviewed were written by coauthors at this institution. However, these letters were written before the inception of this research study. Only 1 year of data was examined in this study, which may not be applicable to the wider residency community as these data were evaluated in the second year of SLOR use.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this study was waived by the Prisma Health-Midlands Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analysis

Data were retrieved from the REDCap system (Research Electronic Data Capture, Vanderbilt, National Institutes of Health [NIH/NCATS UL1 TR000445]). Comparisons were made using complete-case analyses. Comparisons of scores between leaders and others were assessed using two-sample independent t-tests assuming equal variances; 95% confidence intervals were also calculated for the difference in the two population means. We considered a 1-point difference on 5-point scales to be a clinically important difference and a 2-point difference on 10-point scales to be clinically important.

Results

Proportion of Letters in Top 10% and Top One-third

We found that 36% (437 of 1207) of the letters we reviewed indicated the candidate was in the top 10th percentile of orthopaedic candidates reviewed that year by the letter writer, and 51% (619 of 1207) of the letters we reviewed indicated the candidate was in the top one-third of orthopaedic candidates reviewed that year by the letter writer.

Were Scores from Program Leaders Lower than Those from Other Faculty?

We found no clinically important difference between program leaders and other faculty members in terms of summative scores on the SLOR (1.9 ± 0.7 versus 1.7 ± 0.7, mean difference -0.2 [95% CI -0.3 to 0.1]; p < 0.001). The mean aggregate scores for program directors and chairs were not higher than those for other program faculty (8.2 ± 1.5 versus 8.4 ± 1.4, mean difference 0.2 [95% CI -0.1 to 0.3]; p = 0.20) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Aggregate and summative scores by leadership

| Parameter | Leaders, mean ± SD | Others, mean ± SD | Mean difference (95% CI) | p value |

| Aggregate score | 8.2 ± 1.5 (n = 537) | 8.4 ± 1.4 (n = 675) | 0.2 (-0.1 to 0.3) | p = 0.20 |

| Summative score | 1.9 ± 0.7 (n = 533) | 1.7 ± 0.7 (n = 666) | -0.2 (-0.3 to 0.1) | p < 0.001a |

This difference is unlikely to be clinically important.

The possible range of summative scores ranging from highest to lowest are on a 5-point scale, with 1 being ranked to match and 5 being not a fit for our program. The possible range of aggregate scores is from lowest (1) to highest (10) to include all medical and personal attributes and summative scores.

Were Scores from Home Rotations Higher than Those from Away Rotations?

We found no clinically important difference between home program letter writers and away program letter writers in terms of the mean summative scores (1.9 ± 0.7 versus 1.7 ± 0.7, mean difference 0.2 [95% CI 0.1 to 0.2]; p < 0.001). The mean aggregate scores for home program letter writers were not higher than letters from away programs (8.3 ± 1.5 versus 8.1 ± 1.5, mean difference 0.2 [95% CI -0.2 to 0.1]; p = 0.41).

Discussion

The letter of recommendation is an important tool used by residency programs to differentiate highly qualified applicants in a competitive field. Although the letter can be useful, it is generally believed that letters are highly complimentary and often do not distinguish one applicant from another in their application packet; however, it is not known whether the SLOR has reduced this problem in any meaningful way. We found that the problem appears to persist with letters that use the SLOR; more than one-third of applicants are ranked in the top 10th percentile of the SLOR. We found no important differences between program leaders and other faculty in terms of this “grade inflation” and no important differences between letters from home and away residency programs.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this study compares SLOR data only. We were unable to compare this with letters written in the standard format before SLOR implementation. Readers should consider that trends seen between the two letter formats were not compared in this paper, and readers should interpret our findings with the understanding that similar trends may be seen in standard letters, but we did not evaluate those. Second, this study is from a single allopathic institution with 1 year of application data for the 2018 NRMP Match. These data were collected in the second year of the SLOR’s implementation, and it is possible that fewer writers were using this form than are now. It is possible that with increasing familiarity, writers will become more adept at making use of the whole scale; however, if so, this would need to be proven.

Third, letter writers were asked to quantify the time they spent with each applicant for whom they completed a SLOR. Even though this variable was not examined as a goal of the study, it could confound the quality of the score given to applicants who were known for shorter or longer periods of time. Letter writers from away rotations know applicants for shorter lengths of time than those at home institutions in most situations. Future studies will have to address this in greater detail if researchers believe it is important; the very small differences we found suggest it may not be a worthwhile avenue to pursue. Lastly, our institution, Prisma Health-Midlands University of South Carolina in Columbia, SC, USA, is in a medium-sized urban setting and may not provide data that apply to osteopathic orthopaedic residencies or allopathic residencies in different regions of the country. Program type and location play a large role in applicants’ choice of programs for the Match.

Proportion of Letters in Top 10% and Top One-third

We found that a very high percentage (36% [437 of 1207]) of the letters reviewed indicated the candidate was in the top 10th percentile of candidates reviewed that year by the letter writer, and 51% (619 of 1207) of the letters reviewed indicated the candidate was in the top one-third of candidates reviewed this year by the letter writer. We discovered that a disproportionate number of applicants are ranked in the top 10% and top one-third given the pool of applicants to a single allopathic institution. Although the SLOR applies a numeric score to the letter-writing process, it is important to remember when evaluating applicants’ SLOR forms that these data are still heavily skewed toward an overly positive evaluation of most applicants. Similar studies of the orthopaedic SLOR confirm overly positive evaluations of applicants, with one study ranking 48% of applicants in the top 10% and another placing 88% of applicants in the top 10% and top one-third [5, 9]. Knowing that these trends persist across multiple studies, when applicants have a lower ranking, it may push their application to one that is not reviewed. For a top applicant, it may make them appear equal to those who are not of the same academic standing.

Were Scores from Program Leaders Lower than Those from Other Faculty?

We found no important differences between the summative scores and aggregate scores of program leaders and those of other faculty members. In the past, anecdotally, weight often has been given to a well-known or more senior letter writers’ strong praise of an applicant. To our knowledge, no studies have formally tried to correlate or compare the level or experience of orthopaedic faculty members with the SLOR scores they provide in their letters. By contrast, in emergency medicine, which has had a SLOR in place for almost a decade, one study found that 41% of program directors believed inexperienced writers diminished the value of the SLOR score [7]. We theorized, based on some preliminary data from a Council of Emergency Residency Director’s study [2], that we might observe lower scores for letter writers who have assisted in training and written more letters, but we did not find this to be the case. We believe the difference between our findings and those of the emergency medicine study [2] may have been driven by differences in the definition of faculty experience levels. The Council of Emergency Residency Director’s study defined “experienced” using the number of letters written previously, while we divided the groups into faculty leadership and other faculty; we did this because we felt that program leaders might write letters that are more overtly promotional of the program, but our findings suggest there is no need to adjust scores downward when reviewing letters from program leadership.

Were Scores from Home Rotations Higher than Those from Away Rotations?

We found no important difference between the summative and aggregate scores of letters from home programs and those from away programs. We had theorized that letters from an applicant’s home institution are written by faculty who may have known the applicant longer or more intimately, which we thought might result in higher scores. We did not find this to be true. To our knowledge, this comparison has not been made in prior studies of the orthopaedic SLOR. However, one otolaryngology study found that better SLOR scores were associated with faculty who had longer duration of contact among home letter writers [4]. We did not specifically measure duration of time in this study, but we found no important differences in summative scores between home and away program letter writers. For that reason, we believe that letter readers should not adjust scores upward or downward based on whether they came from an applicant’s home institution.

Conclusion

We found that more than one-third of letters ranked candidates in the top 10th percentile, and they ranked more than half in the top one-third. This represents substantial “grade inflation” even when using the SLOR. However, we found no important differences between program leaders and junior faculty in SLOR scores. We also found no important differences in SLOR scores between away and home institution letter writers. Application readers should consider the skewed distribution toward complimentary applicant evaluations during the application review and recognize that the SLOR may not be a fair assessment. Similar to ACGME orthopaedic residency milestones, specific criteria could be added to the instructions of the SLOR for letter writers so that a more normal distribution of applicants would result. Readers should recognize that scores from senior faculty and away letters do not differ substantially from those of junior faculty and home letters, and as such, we found no reason why letter readers should mentally adjust their opinions of applicants based on those differences in letter writers when evaluating applications. Future studies should reexamine the SLOR data now that the SLOR has been used for several more years to see if a wider or different distribution of scores has resulted. Additional studies could also evaluate the SLOR data compared with the traditional narrative letter of recommendation to see if there are differences in the evaluation of an applicant’s qualifications for orthopaedic residency.

Footnotes

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that neither he, nor any member of his immediate family, has funding or commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Ethical approval for this study was waived by the Prisma Health-Midlands Institutional Review Board.

This work was performed at Prisma Health-Midlands University of South Carolina, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Columbia, SC, USA.

Contributor Information

Zachary T. Thier, Email: zach.thier@gmail.com.

J. Benjamin Jackson, III, Email: benjamin.jackson@prismahealth.org.

David E. Koon, Jr, Email: david.koon@uscmed.sc.edu.

Gregory Grabowski, Email: greg.grabowski@uscmed.sc.edu.

References

- 1.American Orthopaedic Association. Electronic standardized letter of recommendation (eSLOR). Available at: https://www.aoassn.org/standardized-electronic-letter-of-recommendation-eslor/. Accessed September 14, 2018.

- 2.Beskind D, Hiller K, Stolz U, et al. Does the experience of the writer affect the evaluative components on the standardized letter of recommendation in emergency medicine? J Emerg Med. 2014;46:544-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhat R, Takenaka K, Levine B, et al. Predictors of a top performer during emergency medicine residency. J Emerg Med. 2015;49:505-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu A, Gu J, Wong B. Objective measures and the standardized letter of recommendation in the otolaryngology residency match. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:603-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inclan P, Cooperstein A, Powers A, et al. When (almost) everyone is above average: a critical analysis of American Orthopaedic Association Committee of Residency Directors standardized letters of recommendation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;5:e20.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimple A, McClurg S, Del Signore A, et al. Standardized letters of recommendation and successful match into otolaryngology. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:1071-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Love J, Smith J, Weizberg M, et al. Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors' standardized letter of recommendation: the program director's perspective. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:680-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts C, Khanna P, Rigby L, et al. Utility of selection methods for specialist medical training: a BEME (best evidence medical education) systematic review: BEME guide no. 45. Med Teach. 2018;40:3-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samade R, Balch Samora J, Scharschmidt T, Goyal K. Use of standardized letters of recommendation for orthopaedic surgery residency applications: a single-institution retrospective review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102:e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]