Abstract

Aim The purpose of this official guideline published and coordinated by the German Society for Psychosomatic Gynecology and Obstetrics [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychosomatische Frauenheilkunde und Geburtshilfe (DGPFG)] is to provide a consensus-based overview of psychosomatically oriented diagnostic procedures and treatments for fertility disorders by evaluating the relevant literature.

Method This S2k guideline was developed using a structured consensus process which included representative members of various professions; the guideline was commissioned by the DGPFG and is based on the 2014 version of the guideline.

Recommendations The guideline provides recommendations on psychosomatically oriented diagnostic procedures and treatments for fertility disorders.

Key words: psychosomatics, fertility disorders, guideline, reproductive medicine

I Guideline Information

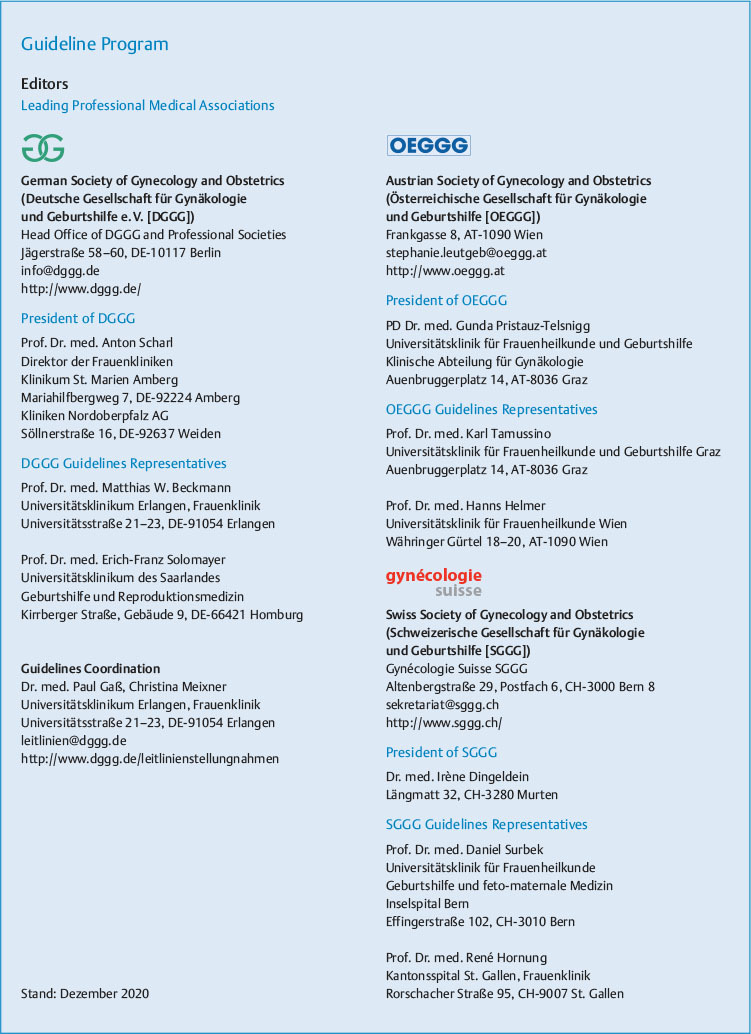

Guidelines program of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG

For information on the guidelines program, please refer to the end of this guideline.

Citation format

Psychosomatically Oriented Diagnostics and Therapy for Fertility Disorders. Guideline of the DGPFG (S2k-Level, AWMF Registry Number 016/003, December 2019). Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2021; 81: 749 – 768

Guideline documents

The complete long version and a slide version of this guideline as well as a list of the conflicts of interest of all of the authors are available in German on the homepage of the AWMF: http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/016-003.html

Guideline authors

Table 1 Lead author and/or coordinating guideline author.

| Author | AWMF professional society |

|---|---|

| Prof. Dr. sc. hum. Dipl.-Psych. Tewes Wischmann (lead author) | German Society for Psychomatic Gynecology and Obstetrics [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychomatische Frauenheilkunde und Geburtshilfe e. V.] (DGPFG) |

| Prof. Dr. med. Heribert Kentenich | German Society for Gynecological Endocrinology and Reproductive Medicine [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologische Endokrinologie und Fortpflanzungsmedizin e. V.] (DGGEF) |

Table 2 Contributing guideline authors and mandate holders.

| Author Mandate holder |

DGGG working group/AWMF/non-AWMF professional society/organization/association |

|---|---|

| * Author of the long version of the guideline text. | |

| PD Dr. Ada Borkenhagen* | German Psychoanalytic Society [Deutsche Psychoanalytische Gesellschaft] (DPG) |

| Prof. Dr. Matthias David* | – |

| Dr. Almut Dorn* | German Association for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde] (DGPPN) |

| Prof. Dr. Christoph Dorn* | – |

| Dr. Friedrich Gagsteiger | Professional Association of Gynecologists [Berufsverband der Frauenärzte] (BVF) |

| Dr. Maren Goeckenjan | German Society for Reproductive Medicine [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Reproduktionsmedizin] (DGRM) |

| Prof. Dr. Heribert Kentenich* | German Society of Gynecological Endocrinology and Reproductive Medicine [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologische Endokrinologie und Fortpflanzungsmedizin] (DGGEF) |

| Prof. Dr. Annika Ludwig* | – |

| Dipl.-Psych. Anne Meier-Credner | Donor Offspring Association [Verein Spenderkinder] |

| Michelle Röhrig | Endometriosis Association [Endometriose-Vereinigung] |

| Dr. Dipl.-Psych. Ingrid Rothe-Kirchberger | German Society for Psychoanalysis, Psychosomatics and Psychodynamic Psychology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychoanalyse, Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Tiefenpsychologie e. V.] (DGPT) |

| M. Sc. Psych. Maren Schick* | German Society of Medical Psychology [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Medizinische Psychologie] (DGMP) |

| Prof. Dr. Stefan Siegel | German Society for Sexual Medicine, Sexual Therapy and Sexual Science [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Sexualmedizin, Sexualtherapie und Sexualwissenschaft] (DGSMTW) |

| Dr. Andreas Tandler-Schneider | Association of Centers for Reproductive Medicine [Bundesverband Reproduktionsmedizinischer Zentren] (BRZ) |

| Dr. Petra Thorn* | Infertility Counseling Network Germany [Beratungsnetzwerk Kinderwunsch Deutschland] (BKiD) |

| Dr. Anna Julka Weblus* | German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe] (DGGG) |

| Prof. Dr. Tewes Wischmann* | German Society for Psychosomatic Gynecology and Obstetrics [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychosomatische Frauenheilkunde und Geburtshilfe] (DGPFG) |

This guideline was moderated by Dr. med. Monika Nothacker (AWMF-certified guideline moderator).

II Guideline Application

Purpose and objectives

The number of diagnostic procedures and therapies carried out in Europe to treat fertility disorders has continually increased over the last few years. Scientific research is increasingly focusing on the psychosocial and psychosomatic aspects of fertility disorders, but they are barely or only inadequately acknowledged in everyday life. This is why, in 2019/2020, it was thought to be time to update AWMF guideline no. 016-003 (dating from 2014).

The aim of the guideline is to evaluate recent scientific literature and expert opinions and compile recommendations to provide optimal psychosomatically oriented care to women and men (and couples) whose wish to have children has not been fulfilled. Care of these patients ranges from diagnostic procedures to potential therapies to considering alternative perspectives and successfully managing the crisis posed by a fertility disorder.

Targeted area of patient care

Outpatient care is offered to women, men, and couples of reproductive age who are involuntarily childless.

Target user group/target audience

All inpatient-based and outpatient-based physicians who are involved in the care and treatment of infertile women, men, and couples who wish to have children. This includes, in particular, gynecologists, andrologists, physicians specializing in gynecological endocrinology and reproductive medicine (fertility specialists). Other target users are psychologists, medical and psychological psychotherapeutists, psychiatrists, psychosomatic physicians and other counselors and professionals involved in the psychosocial and psychosomatic care of individuals and couples with fertility disorders.

Adoption and period of validity

This version 4.0 of the guideline was adopted at the consensus conference held on December 9, 2019. If changes are urgently required, the guideline may be updated earlier. Similarly, if a guideline continues to reflect the current state of knowledge, its period of validity may be extended for a maximum period of 5 years (meaning that this guideline is maximally valid until December 8, 2024).

III Methodology

Basic principles

The method used to prepare this guideline was determined by the class to which this guideline was assigned. The AWMF Guidance Manual (version 1.0) has set out the respective rules and requirements for different classes of guidelines. Guidelines are differentiated into lowest (S1), intermediate (S2), and highest (S3) class.

This guideline has been classified as: S2k .

Grading of recommendations

The grading of evidence based on the systematic search, selection, evaluation and synthesis of an evidence base which is then used to grade the recommendations is not envisaged for S2k guidelines. The different individual statements and recommendations are only differentiated linguistically, not by the use of symbols ( Table 3 ).

Table 3 Grading of recommendations (in English, according to Lomotan et al. Qual Saf Health Care 2010).

| Description of binding character | Expression |

|---|---|

| Strong recommendation with highly binding character | must/must not |

| Regular recommendation with moderately binding character | should/should not |

| Open recommendation with limited binding character | may/may not |

Statements

Expositions or explanations of specific facts, circumstances or problems without any direct recommendations for action included in this guideline are referred to as “Statements”. It is not possible to provide any information about the grading of evidence for these Statements.

Achieving consensus and level of consensus

At structured NIH-type consensus-based conferences (S2k/S3 level), authorized participants attending the session vote on draft statements and recommendations. The process is as follows. A recommendation is presented, its contents are discussed, proposed changes are put forward, and finally, all proposed changes are voted on. If a consensus is not achieved (> 75% of votes), there is another round of discussions, followed by a repeat vote. Finally, the extent of consensus is determined based on the number of participants ( Table 4 ).

Table 4 Level of consensus based on extent of agreement.

| Symbol | Level of consensus | Extent of agreement in percent |

|---|---|---|

| +++ | Strong consensus | > 95% of participants agree |

| ++ | Consensus | > 75 – 95% of participants agree |

| + | Majority agreement | > 50 – 75% of participants agree |

| – | No consensus | < 51% of participants agree |

Expert consensus

As the name already implies, this refers to consensus decisions taken specifically with regard to recommendations/statements made without a prior systematic search of the literature (S2k) or where evidence is lacking (S2e/S3). The term “expert consensus” (EC) used here is synonymous with terminology used in other guidelines such as “good clinical practice” (GCP) or “clinical consensus point” (CCP). The strength of the recommendation is graded as previously described in the chapter on the grading of recommendations; it is only expressed semantically (“must”/“must not” or “should”/“should not” or “may”/“may not”) without the use of symbols.

IV Guideline

1 Definition and scope

The following guidelines cover psychosomatically oriented diagnostic procedures and treatments for involuntary childlessness. The WHO defines infertility as a failure to achieve a pregnancy after twelve months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse. It can be assumed that biological, psychological and social factors play a role in the development, course, diagnostic procedures, and treatment of involuntary childlessness. In this guideline, the terms fertility disorders or subfertility are used synonymously for sterility or infertility as most couples are not definitely or permanently infertile.

2 Psychosomatic diagnostics

3.1 Prognostic criteria for achieving pregnancy in involuntarily childless couples

3.2 Pregnancy, childrenʼs health, and family dynamics after successful assisted reproduction

3.3 Psychological consequences of involuntary childlessness

4.1 Diagnostic measures from a psychosomatic point of view

4.2 Treatment

4.3 Counseling and psychotherapy

4.3.1 Prevention of fertility disorders

4.3.2 Older couples wanting to have children

5 Reproductive medicine for couples with migration background

6 Starting a family with third party help

7 Gender incongruence and fertility

8 Reproductive medical treatment abroad

9 Media offering information and advice

10 Self-help groups

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The conflicts of interest of all of the authors are listed in the long version of this guideline./Die Interessenkonflikte der Autoren sind in der Langfassung der Leitlinie aufgelistet.

Statement 2.1-S1.

The prevalence of psychopathological abnormalities is not higher in women and men who are involuntarily childless, even if no organic causes of the childlessness could be identified.

A behavior-related fertility disorder (which could be potentially related to psychosocial causes) is found in 5% or at most 10% of all couples.

For many couples, experiencing a fertility disorder as well as the psychological impact of assisted reproductive treatment is a significant emotional burden. Both women and men experience this as stressful.

However, according to the findings of a number of large studies and meta-analyses, the direct impact of everyday stresses on a fertility disorder and on the success of IVF/ICSI treatment is relatively negligible (cf. also Section 3.1). It is not possible to generalize these findings to couples who are not being treated (cf. AWMF-LL 015-085).

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 2.1-E1.

As involuntary childlessness generally puts a strain on both partners in a relationship, psychosomatically oriented treatment should be explicitly offered to the involuntarily childless couple.

Existing counseling services should be expanded to also address the needs of the male partner, couples with a migrant background, and couples in all social classes (cf. also Section 4.1.5).

These counseling services should be offered proactively and in a non-stigmatizing manner, and the threshold for counseling (financially and organizationally) should be low.

Lifestyle and behavioral factors known to lower fertility should be proactively addressed during the coupleʼs psychosomatically oriented counseling.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 3.1-S2.

The womanʼs age, duration of infertility und behavioral factors are significant prognostic preconditions for achieving pregnancy.

Based on general or specific psychosocial factors (e.g., anxiety, depression or specific partnership-related aspects), it is not possible to predict whether a woman will become pregnant after she has undergone reproductive medical treatment.

Psychological stress is known to be a possible consequence of a fertility disorder. Increased depression and anxiety may result from the psychological burden during or following unsuccessful assisted reproductive treatment.

Whether psychological stress could be a causative factor for infertility is still being discussed. The direct impact of everyday stresses on a fertility disorder or on the success of IVF/ICSI treatment is considered to be negligible (cf. also Section 2.1).

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 3.1-E2.

More consideration should be given to psychosocial factors in the context of assisted reproductive treatment and additionally, accompanying psychosomatically oriented counseling sessions should focus on them.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement: 3.2-S3.

The risk of complications of pregnancy is higher after ART compared to spontaneous conceptions. During the course of the pregnancy, there is a higher probability of preeclampsia (1.5 times higher), placenta praevia (3 times higher), stillbirth (2.5 times higher), lower birth weight (1.7 times higher) and growth restriction (1.5 times higher).

Proposed causes of these increased complications of pregnancy and neonatal complications are currently being discussed and mainly point to subfertility as a background risk but also the direct impact of fertility treatment.

Multiple pregnancies have a higher risk of complications of pregnancy and preterm birth with all the consequent neonatal and postnatal complications. This also applies to singleton pregnancies after a pregnancy which was initially conceived as a multiple pregnancy (“vanishing twin”).

Compared to the risk factor “multiple pregnancy”, the type of conception appears to be less important, meaning that it is no longer significant for twin pregnancies.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 3.2-E3.

Infertile couples wanting to have children must be informed about the increased risk of pregnancy complications.

Multiple pregnancies must be avoided where possible, even if the couple explicitly wants to have a multiple pregnancy. This also affects the problem of the “vanishing twin”.

Couples must be informed in detail about the increased risks associated with a multiple pregnancy before starting fertility treatment. Couples may be advised that if a twin pregnancy occurs, the pregnancy risks do not appear to be higher than those occurring after spontaneous conception of twins.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 3.2-S4.

The risk of malformation after IVF and ICSI is, on average, 1.3 times higher (about every 12th pregnancy) compared to spontaneous conception (about every 15th pregnancy).

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 3.2-E4.

Infertile couples wanting to have children must be informed about the increased risk of malformations after IVF and ICSI.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 3.2-S5.

The risk of hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, preterm birth, and low birth weight are higher after implantation of a donor egg compared to conventional IVF treatment.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 3.2-E5.

Couples should be advised about the increased risks following implantation of a donor egg (compared to conventional IVF treatment) and these risks should be taken into account when caring for a pregnant woman who has been implanted with a donor egg.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 3.2-S6.

The risk of pregnancy complications with surrogacy is comparable to the level of risk associated with conventional ART but higher than that of spontaneous conception.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 3.2-S7.

Children conceived with ART develop similarly to spontaneously conceived children, provided they are born at term and with a normal birth weight. According to the most recent studies, the overall risk of malignancy does not appear to be significantly increased. Some studies have reported higher neurological morbidity rates, but these appear to be due most likely to the higher rate of multiple pregnancy. Despite a possibly slightly higher relative risk, the absolute risk for the individual child remains low.

Data on cardiovascular risk factors must be treated with caution because of the limited cohort sizes and heterogeneity of the studies. Some studies have reported higher blood pressure in children and adolescents following ART, but other studies were unable to confirm this.

Initial data on puberty development and surrogacy parameters on the fertility of boys conceived with ICSI suggest that their fertility in later life may be lower.

Further data on the long-term health of children and adolescents are required.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 3.2-E6.

Infertile couples must be informed about the overall lower absolute risks to the health and development of (singleton) children conceived with ART, based on current knowledge.

Because of the increased risk associated with multiple pregnancy due to the higher rate of preterm births associated with a multiple pregnancy, couples must be informed about these risks.

The risk of multiple pregnancy after ART must be kept to a minimum (“single embryo transfer”).

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 3.2-S8.

Children conceived with donated gametes appear to develop normally.

There is currently insufficient evidence about the psychosocial development of children born through surrogacy.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 3.2-E7.

Women (and their partners) who have a miscarriage after fertility treatment should be offered low-threshold psychosomatic support.

Level of consensus: ++

Statement 3.2-S9.

If couples have been unable to have a child for a long time, it is conceivable that they will have a lot of anxiety about the pregnancy and the child. Moreover, couples may idealize parenthood and therefore place high demands on themselves as parents.

The existing data show that the risk of postpartum depression is not higher after ART. The data on pregnancy-related anxiety are inconsistent. Some studies have pointed to higher pregnancy-related anxiety, but other studies have not confirmed this.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 3.2-S10.

There are no differences in family dynamics after assisted reproduction using the partnerʼs sperm compared to spontaneous conception.

A multiple birth may be associated with a higher psychosocial risk (both for the parents and the children), particularly in the case of births of more than two children.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 3.3-S11.

Long-term changes to the psychosocial situation of couples for whom assisted reproductive treatment was unsuccessful show that the unfulfilled wish to have children often plays a big role in the coupleʼs life. Infertility is perceived by many affected people as a difficult stage in their lives. Most couples cope with the situation over the long term and their psychological wellbeing is no longer affected later on.

In the long term, there is very little difference in the quality of life and life situation between childless people and people who had children with fertility treatment. However, for some of the affected persons, involuntary childlessness remains a life event which repeatedly triggers feelings of regret (e.g., in certain stages of life such as menopause or when people of the same age become grandparents) and may require repeated efforts to adapt.

Involuntary childlessness becomes a constant burden when the capacity to develop new perspectives on life is limited. This capacity is influenced by the individualʼs psychological predisposition, the course of the infertility crisis, the motives behind the wish to have children, the intensity of the wish to have children, the individualʼs satisfaction with their partner and the attribution of the cause. Severe social isolation has been found to be an unfavorable prognostic factor.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 3.3-E8.

Couples or women who have remained involuntarily childless should be informed about the largely favorable prognosis in terms of quality of life and partnership but also about possible risk factors (e.g., social isolation) and protective factors (e.g., early development of new life goals and concepts). In cases with an unfavorable course, affected persons should be pointed in the direction of appropriate psychosomatically oriented counseling options.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 4.1-S12.

From a scientific point of view, there are (still) no clear psychological contraindications for assisted reproductive treatment. Individual decisions should be taken based on the coupleʼs reproductive autonomy and following interdisciplinary consultation about the childʼs best interests.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 4.1-E9.

A first talk and a final discussion should be held with the couple (unless the issue affects a single woman wanting to have a child; cf. Section 4.3.5).

Psychosomatically oriented counseling should be optional with low-threshold availability at every timepoint during medical diagnostic procedures and treatment. Prior to starting treatment with donated gametes or donated/adopted embryos, the couple or individual must be offered psychosomatic counseling. Whether or not the offer of counseling is taken up must be recorded.

Counseling should also be available to couples/individuals who have not (yet) started or are no longer receiving assisted reproductive treatment.

In principle, psychosomatically oriented diagnostics must be carried out during the initial discussion (with the couple) (cf. also the German Medical Association 2018):

They should particularly be used in the following situations:

counseling or accompanying discussions prior to invasive medical procedures (e.g., when switching from IUI to IVF, prior to starting treatment abroad or similar),

prior to gamete donation or embryo donation/adoption,

prior to fetocide,

if the partner has a chronic illness,

in the event of multiple pregnancy,

if reproductive medical treatment is unsuccessful (failure to become pregnant, miscarriage or stillbirth), and

in the final discussion.

Level of consensus: ++

Recommendation 4.2-E10.

Medical care provided in the context of infertility treatment must be carried out in accordance with the principles of primary psychosomatic care. Psychosocial aspects must be included more in the treatment of infertility.

Assisted reproductive treatment must allow space for the need for psychosocial counseling. Irrespective of the reproductive medical treatment, low-threshold, psychosomatically oriented counseling must always be available.

The need for counseling increases when using donated gametes (cf. Recommendation E16 – E19) or embryos (cf. Recommendation E22).

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 4.3-S13.

The limited number of available studies on the effects of psychosocial interventions in subfertile women and men emphasizes the importance of carrying out more high-quality, methodologically sound research into psychosocial counseling and treatment for fertility disorders.

The studies consulted for this review (the majority focused on behavioral therapies and combined treatments) reported predominantly positive effects, with psychosocial interventions reducing the psychological stresses associated with reproductive medical treatment; the studies are, however, inconclusive with regard to increased pregnancy rates in subgroups.

To date, the increasing number of internet-based support programs have also been insufficiently scientifically evaluated.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 4.3-E11.

All persons who decide to begin fertility treatment must be given the opportunity to obtain information, explanations and counseling in the sense of emotional support and help to deal with problems.

Counseling services should be independent of treatment and address all women and men, particularly if they have previously had negative experiences of subfertility or had several unsuccessful treatment attempts.

Psychosomatic interventions should primarily aim to provide information, improve psychological wellbeing, and reduce stress.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 5-S17.

While many couples have personal and partner-related reasons for wanting to have children, the wish to have children expressed by couples from especially pronatalist countries is often also strongly influenced by social motives.

The pressures on many couples with a migration background when a desired and expected pregnancy does not occur appears to be particularly high and may lead to increased psychological stress for both partners.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 5-E15.

Before giving detailed explanations about the course of reproductive medical treatments, the treating physician should get an overview of the respective coupleʼs existing knowledge of biological processes and sexuality.

Couples with a migration background should also be informed in detail about the causes of infertility to help to reduce at least part of the possibly existing feelings of guilt and shame associated with involuntary childlessness.

When providing advice about subfertility and information about medical reproductive treatment, specific culturally sensitive approaches should be used, which take account of social and cultural aspects when interacting with subfertile women or couples with a migration background.

Although it is important to be aware of the specific cultural and religious considerations of the couple, the treating physician should be impartial when describing all the treatment options and ask questions which invite the couple to present their personal perspectives, concerns, and questions.

In many cases there may be problems communicating with immigrant women and their partners because of language barriers. Centers of reproductive medicine should therefore have appropriate information materials in different languages and, if necessary, also insist on involving an interpreter. Using laypersons as interpreters should be avoided if possible.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 6-S18.

There are no indications for adverse developments in children conceived with donated sperm and growing up in heterosexual families, as long as these children are informed about the conception and the sperm donation was not anonymous.

In Germany, persons conceived with donated sperm have the right to learn about their genetic origin.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 6-E16.

Children should be given age-appropriate explanations early on (when they are still of preschool age), not least because this avoids having difficult family secrets with potential betrayals of confidence within the family.

If contacts between the child and the donor and/or half-siblings are planned, all persons involved should be able to attend psychosomatically oriented counseling to suitably prepare themselves, and such contacts should be accompanied by counseling, if required.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 6-S19.

The motivation of lesbian couples to become parents does not differ much from that of heterosexual couples. Lesbian couples face the task of deciding about who will be the mother and the importance of the donor/genetic procreator for their future family.

Children in lesbian families develop normally, and their psychosexual development is also unremarkable.

Level of consensus: ++

Recommendation 6-E17.

Children born to lesbian parents should be informed about how they were conceived early on and, if they want to, be able to meet with the donor/genetic procreator, irrespective of whether their parentsʼ treatment was carried out in the form of medically assisted conception, privately, or abroad.

Level of consensus: ++

Statement 6-S20.

There is very little data available on families born to single women who had fertility treatment. Initial studies indicate that the children of these solo mums develop just as well as those growing up with two parents and that solo mums also have no distinctive characteristics. However, there are still no conclusive long-term studies.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 6-E18.

The special counseling needs of solo mums in terms of psychosocial care, safeguarding and the childʼs legal position should be considered.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 6-S21.

Insemination with the sperm of a man known to the would-be parents changes traditional and genetic family relationships.

There is no scientific knowledge available, particularly about the long-term effects of this approach to create a family.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 6-E19.

All persons involved in this type of family creation must be offered comprehensive psychosomatically oriented counseling.

Level of consensus: ++

Statement 6-S22.

Studies have shown that men are prepared to donate sperm even if they can be identified to the children conceived in this manner.

Because of the provisions of the German Sperm Donor Registry Act, men who donate sperm for medically assisted conception procedures are no longer liable for child support or similar.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 6-E20.

Men who donate sperm for medically assisted conception procedures must be informed about the legal regulations, particularly about the childʼs right of information and the possibility that the child could contact them.

They must also be informed about the possible consequences of DNA tests and gene databases.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 6-S23.

Co-parenting is a type of family about which there is very limited empirical evidence and no scientific information.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 6-E21.

Persons involved in co-parenting families should obtain detailed advice beforehand about all (potential) implications (including about who the legal parents are).

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 6-S24.

According to currently available studies, children conceived by embryo donation/adoption develop normally.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 6-E22.

Children conceived by embryo donation/adoption should be given an age-appropriate explanation early on and have the right to know about their origin.

Psychosomatically oriented counseling must be offered to both the donating parent and the parent accepting the donation. As with families created with the help of donated gametes, all persons involved should have low-threshold access to psychosocial support before there is any contact between the child (and their family) and the donor (and their family).

Level of consensus: ++

Statement 6-S25.

According to prospective comparative studies, the development of children conceived by oocyte donation is unremarkable and does not differ from that of children conceived spontaneously or with conventional ART, and they generally have a stable parent-child bond. Long-term studies are not available.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 6-E23.

Children conceived by oocyte donation must have the right to know about their origins and should be given age-appropriate explanations early on.

As with all types of families created by gamete donation or embryo donation/adoption, the persons involved should have access to psychosomatically oriented support before there is any contact between the child (and their family) and the donor (and their family).

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 6-S26.

Existing studies show that children born to surrogate mothers under legally regulated conditions develop normally. Just like children born by gamete donation or embryo donation/adoption, they are interested in their surrogate mother and should therefore be able to contact them.

According to the limited studies available, this type of family does not appear to be problematic, including for the surrogate mother herself, her children and the would-be parents, if the family was created under legally regulated conditions.

Long-term studies are not available.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 6-E24.

Children born to surrogate mothers should be given an age-appropriate explanation early on.

Level of consensus: +++

Statement 7-S27.

Many trans people want to have children at some time in their life.

Some trans people seek to change their body in accordance with their gender identity, using hormone treatments and/or surgery.

Most hormone treatments and particularly gender reassignment surgery may limit or result in an irreversible loss of reproductive capacity.

The (long-term) effects of gender reassignment hormone treatment on fertility are not clear.

There are no indications of any threats to the wellbeing of a child growing up with a trans parent.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 7-E25.

Trans people should have access to all available options for reproductive medical treatment.

Before starting gender reassignment treatment, all trans people must be advised about the possible impact on fertility and the options to protect fertility and have a family.

Trans men who keep their reproductive organs should be advised about contraception.

Children who are conceived after gender reassignment should be informed both about the reasons, type and circumstances of conception and about their parentsʼ gender identity in an age-appropriate manner.

Interactions should be respectful and the trans personʼs preferred pronouns should be used. Gender-neutral terms should be used during medical consultations and/or treatment.

Medical staff should be trained to understand the special concerns of trans patients.

Level of consensus: ++

Statement 8-S28.

There is almost no scientific data available on couples and individuals who travel abroad for subfertility treatment. Descriptions of individual cases and clinical experience, however, show that there is great demand for medical, legal and psychosocial counseling among these couples.

Level of consensus: ++

Recommendation 8-E26.

Couples and individuals who intend to undergo subfertility procedures abroad that are forbidden in Germany should be able to fall back on both medical and psychosocial counseling in Germany. It is therefore necessary that such counseling is not subject to prosecution.

Would-be parents should be made aware of the different legislation respecting subfertility treatment abroad and the implications of that for creating a family.

Level of consensus: ++

Statement 9-S29.

Information materials about the course and the technical aspects of fertility treatment probably help affected persons to cope with infertility and fertility treatment. Such information may be provided in the form of brochures or educational films but also online. The efficacy of these forms of psychosocial intervention should be evaluated.

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 9-E27.

Up-to-date easy-access and low-threshold information on coping with infertility and infertility treatments should be available to all persons wanting to have children.

Treating physicians should be made aware of the advantages of the internet (e.g., low-threshold availability of national and international guidelines and information portals) and its downsides (e.g., few opportunities to validate other information).

Level of consensus: +++

Recommendation 10-E28.

Even though currently no scientific evaluations of the efficacy of self-help groups for subfertile/infertile persons wanting to have children are available, couples/individuals should be informed about such psychosocial offers of support and the relevant places to contact.

Level of consensus: +++

References

- The literature is listed in the long version of this guideline./Die Literatur ist der Langversion zu entnehmen.