Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD), the triad of asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (CRSwNP), and respiratory reactions to cyclooxygenase-1 inhibitors, is characterized by difficult-to-treat upper and lower respiratory symptoms. It is a type 2-mediated inflammatory disease marked by blood and tissue eosinophilia, dysregulated cysteinyl leukotriene production, and mast cell activation (1). Nasal polyposis in AERD is often severe and refractory to standard-of-care management including topical and systemic corticosteroids, endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS), and aspirin desensitization followed by high-dose daily aspirin (2). Respiratory biologic medications targeting interleukin (IL) 4Rα, IL-5, IL-5α, and IgE are approved for severe asthma and are recently approved or being studied for CRSwNP. Treatment with biologic medications targeting type 2 cytokines and cytokine receptors are attractive options for treating AERD, but data guiding selection of the appropriate agent are limited.

Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-4Rα, is Food and Drug Administration approved for moderate-to-severe eosinophilic asthma and inadequately controlled CRSwNP and has shown efficacy for upper and lower airway symptoms in AERD(3–5). Monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-5 and IL-5Rα are approved for severe eosinophilic asthma(6,7)and are in phase III studies for CRSwNP. Mepolizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-5, has demonstrated some efficacy in managing upper and lower airway symptoms in patients with AERD(8). While biologics targeting IL-5/IL-5Rα and IL-4α are promising treatments for respiratory symptoms, there are no head-to-head studies comparing them. Recent studies raised concerns that biologics targeting IL-5 may have only modest effects on CRSwNP (9). Here we evaluate response to biologic therapy in subjects with AERD who underwent sequential treatment with an anti-IL-5 or IL-5Rα followed by anti-IL-4Rα for management of asthma and/or CRSwNP.

We conducted a retrospective chart review of subjects with physician-diagnosed AERD treated at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), Massachusetts General Hospital, or Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary between March 2016 and July 2020 and who were enrolled in the BWH AERD patient registry. The study was approved by the Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board. Electronic medical records (Epic Systems, Verona, WI) were reviewed for all subjects who had been treated with mepolizumab, benralizumab, or reslizumab. Demographics, medications, clinical characteristics, AERD history, Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22 (SNOT-22) and Asthma Control Test (ACT) scores, spirometry results, and laboratory data were extracted from the medical record. We compared patient-reported outcomes, lung function, and clinical outcomes (A) prior to initiating biologic therapy, (B) at least 60 days after initiating an anti-IL-5/IL-5Rα monoclonal antibody, and (C) for patients who switched biologic therapies, after 60 or more days of treatment with dupilumab, accounting for a wash-out period between treatments. Data were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test, paired t-test, unpaired t-test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate, with GraphPad Prism v7.0d (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA).

We identified 41 AERD patients who were treated with mepolizumab (92.7%, 38/41), reslizumab (2.4%, 1/41), or benralizumab (4.9%, 2/41) for severe eosinophilic asthma. Of those, 27 subsequently transitioned to dupilumab for inadequately controlled upper and/or lower respiratory symptoms, and the remaining 14 continued mepolizumab. Subjects transitioned from anti-IL-5/IL-5Rα therapies (24/27 on mepolizumab, 1/27 on reslizumab, and 2/27 on benralizumab) to dupilumab due to waning efficacy (n=4), inadequate asthma control (n=23), and/or inadequate CRSwNP control (n=6). There were no significant baseline differences in lung function, number of previous sinus surgeries, physician-diagnosed atopy, or absolute eosinophil count (AEC) between those who transitioned to dupilumab vs those who continued with mepolizumab (Table 1). Subjects who continued with mepolizumab had lower baseline serum IgE than those who switched to dupilumab (P=0.04).

Table 1:

Patient Demographics and Baseline* Markers of AERD Severity

| Respiratory biologic treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-IL-5/IL-5Rα then dupilumab (inadequate response to anti-IL-5/IL-5Rα) | Mepolizumab only (satisfactory response to anti-IL-5) | P-value | |

| N = 27 | N = 14 | ||

| Age (y), median (range) | 58 (18 – 76) | 58 (42 – 78) | NS** |

| Gender Female N (%) | 13 (48%) | 7 (50%) | NS^ |

| Race, % White (N/total) | 70% (19/27) | 93% (13/14) | NS^ |

| Weight in kg, mean ± SD | 80.4 ± 17 | 85.1 ± 20.7 | NS** |

| Current or former smoker, N (%) | 7 (26%) | 4 (29%) | NS^ |

| FEV1# % Predicted, mean ± SD | 67.4 ± 16 | 74.2 ± 21.8 | NS** |

| Duration of AERD (y), mean ± SD | 16.2 ± 13.1 | 22 ± 14 | NS** |

| Lifetime number of sinus surgeries, mean ± SD | 3.2 ± 2.8 | 2.8 ± 2.9 | NS** |

| Age of nasal polyp diagnosis (y), median ± SD | 39.5 ± 15.3 | 32 ± 14 | NS** |

| History of aspirin desensitization and daily aspirin therapy@, N (%) | 18 (67%) | 11 (79%) | NS^ |

| Current use of aspirin therapy@ at baseline timepoint, N (%) | 9 (33%) | 6 (43%) | NS^ |

| Oral corticosteroid use in past year (days), mean ± SD | 96.8 ± 130 | 103.2 ± 127.4 | NS** |

| Physician-diagnosed atopy, N (%) | 17 (63%) | 11 (79%) | NS^ |

| Absolute eosinophil count (cells/μL), mean ± SD | 673 ± 403.8 | 528.4 ± 386.6 | NS** |

| Total IgE (IU/mL), mean ± SD | 593.8 ± 876.7 | 80.3 ± 33.8 | 0.04** |

| Duration of anti-IL-5/IL-5R use (months), mean ± SD | 16 ± 8.5 | 40.8 ± 8.6 | |

| Mepolizumab, N = 24 | |||

| Benralizumab, N = 2 | |||

| Reslizumab, N = 1 | |||

| Duration of dupilumab use (months), mean ± SD | 14 ± 5.1 | N/A | |

Baseline values are from allergy/immunology visit prior to start of any respiratory biologic therapy

Unpaired t-test

Fisher’s exact test

Forced expiratory volume in one second

Aspirin therapy: either 650 mg daily or 1300 mg daily

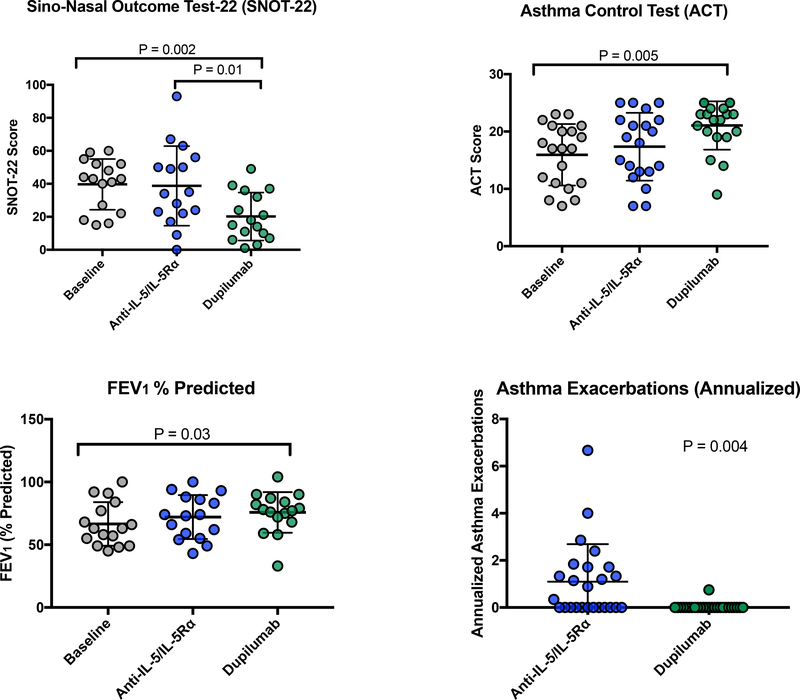

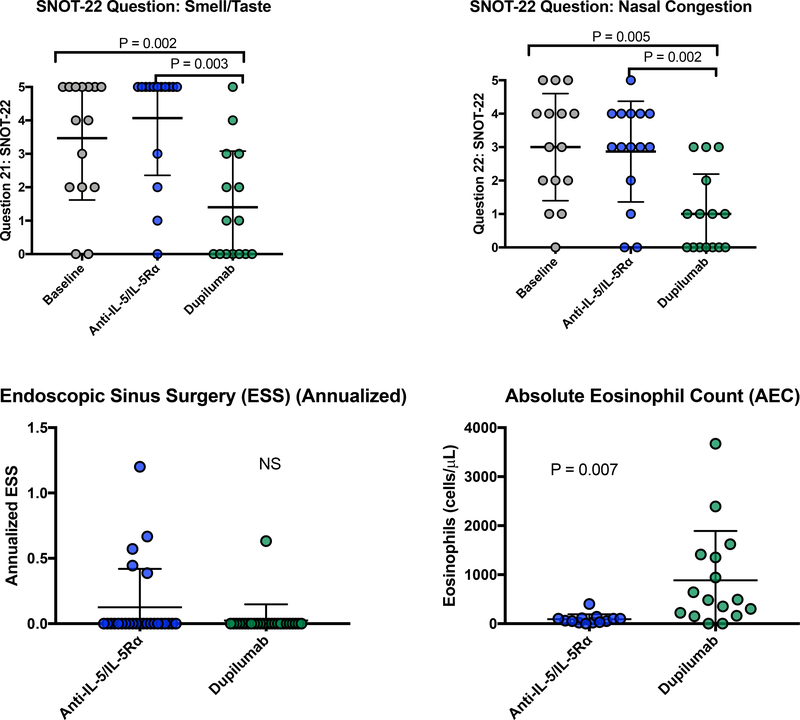

For the 65.9% (27/41) subjects who transitioned to dupilumab, their initial treatment with anti-IL-5/IL-5Rα did not lead to significant improvement in total SNOT-22 scores, smell/taste- or congestion-specific SNOT-22 questions, ACT scores, or FEV1% predicted (Figure 1 and E1). In contrast, total SNOT-22, smell/taste, and congestion scores significantly improved following dupilumab treatment, compared to baseline and to post-anti-IL5/IL-5Rα treatment(Figure 1 and E1). Additionally, ACT scores and FEV1% predicted significantly improved from baseline following dupilumab treatment (Figure 1). There were no differences in FEV1, FVC, and FVC% predicted between baseline, anti-IL-5/IL-5Rα, and dupilumab (data not shown). The annualized asthma exacerbation rate was significantly higher during treatment with anti-IL-5/IL-5Rα compared to dupilumab treatment (P=0.004, Figure 1). Few patients underwent ESS and there was no difference in annualized surgery rate between treatments (Figure E1). As expected, AEC was lower during anti-IL-5/IL-5Rα treatment than during dupilumab treatment (Figure E1).

Figure 1:

For subjects who switched to dupilumab, treatment with ≥60 days of dupilumab led to improved SNOT-22 score, ACT score, and FEV1 % predicted. Annualized asthma exacerbations decreased on dupilumab. Analysis with repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test or paired t test.

Figure E1:

For subjects who switched to dupilumab, treatment with ≥60 days of dupilumab led to improved SNOT-22 patient reported anosmia and congestion. There was no change in annualized ESS. AEC was lower on anti-IL-5/IL-5Rα versus dupilumab. Analysis with repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test or t test.

Comparatively, the 34.1% (14/41) patients who continued on mepolizumab noted significant improvements in total SNOT-22 (mean difference 20, P=0.007), SNOT-22 congestion-specific question (mean difference 1.2, P=0.01), and ACT scores (mean difference 5.4, P=0.02), but not for the SNOT-22 smell/taste-specific question. There was no mepolizumab-induced difference in lung function compared to baseline (Table E1).

Table E1:

Comparison of patient reported outcome measures, lung function, and absolute eosinophil count from baseline compared to treatment with mepolizumab in 14 patients undergoing long-term treatment with mepolizumab.

| Baseline (mean ± SD) | On mepolizumab (mean ± SD) | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNOT-22# | 47.8 ± 14 | 27.8 ± 20.1 | 0.007 |

| SNOT-22, smell | 3.1 ± 2.2 | 1.9 ± 2 | 0.11 |

| SNOT-22, congestion | 2.3 ± 1.7 | 1.1 ± 1.1 | 0.01 |

| Asthma Control Test | 14.3 ± 5.9 | 19.7 ± 5.4 | 0.02 |

| FEV1@ (Liters) | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 0.44 |

| FEV1 % Predicted | 72.1 ± 21.8 | 74.2 ± 21.1 | 0.78 |

| FVC$ (Liters) | 3.4 ± 1 | 3.4 ± 1 | 0.59 |

| FVC % Predicted | 82.1 ± 21.5 | 80 ± 20.2 | 0.35 |

| Absolute eosinophil count (cells/μL) | 528.5 ± 386.6 | 96.7 ± 57.9 | 0.007 |

Paired t-test

Sino-Nasal outcome test-22

Forced expiratory volume in one second

Forced Vital Capacity

While the availability of respiratory biologic medications has broadened treatment options for AERD patients, limited data exists to guide biologic selection. To our knowledge, this is the first comparison of monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-5/IL-5Rα and IL-4Rα in patients with AERD. All subjects with inadequate response to mepolizumab, benralizumab, or reslizumab then had significant improvements in upper and lower airway symptoms and reductions in asthma exacerbations during dupilumab treatment. In contrast, subjects with a satisfactory response to mepolizumab who did not change therapies reported improvements in upper and lower airway symptoms with mepolizumab. The only baseline difference between the two groups was serum IgE level, which may be a useful biomarker to help guide respiratory biologic selection in AERD patients. Our study suggests the possibility of different AERD endotypes, which may be partially driven by specific type 2 cytokines.

This retrospective analysis has limitations as it is not randomized or placebo-controlled, and it relies largely on patient-reported outcomes in a small number of patients. Nonetheless, in this real-world setting we found that AERD patients who failed to improve with mepolizumab, benralizumab, or reslizumab had improvements in asthma control, nasal congestion and anosmia, and reduced asthma exacerbations during subsequent dupilumab treatment. Clinicians should consider dupilumab for AERD patients with inadequate response to anti-IL-5/IL-5Rα therapy. Head-to-head, prospective studies of respiratory biologics for AERD patients would allow for further identification of the responder endotype to guide selection of appropriate biologic therapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants K23AI139352, R01HL128241 and by generous contributions from the Vinik and Kaye Families.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: K.B. has served on scientific advisory boards for AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline. T.L has served on scientific advisory boards for Regeneron, Sanofi, and GlaxoSmithKline. J.B. has served on scientific advisory boards for GlaxoSmithKline. N.B., D.G., and A.M. have no conflicts.

Clinical implications: This study provides evidence for the use of dupilumab in patients with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD) who previously had inadequate response to monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-5 or IL-5Rα. Dupilumab should be considered in patients with AERD who have persistent upper and/or lower respiratory symptoms despite anti-IL-5/IL-5Rα treatment.

References:

- 1.Laidlaw TM, Boyce JA. Aspirin-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease--New Prime Suspects. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(5):484–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kowalski ML, Agache I, Bavbek S, Bakirtas A, Blanca M, Bochenek G, et al. Diagnosis and management of NSAID-Exacerbated Respiratory Disease (N-ERD)-a EAACI position paper. Allergy. 2019;74(1):28–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laidlaw TM, Mullol J, Fan C, Zhang D, Amin N, Khan A, et al. Dupilumab improves nasal polyp burden and asthma control in patients with CRSwNP and AERD. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(7):2462–5 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachert C, Han JK, Desrosiers M, Hellings PW, Amin N, Lee SE, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (LIBERTY NP SINUS-24 and LIBERTY NP SINUS-52): results from two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019;394(10209):1638–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castro M, Corren J, Pavord ID, Maspero J, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, et al. Dupilumab Efficacy and Safety in Moderate-to-Severe Uncontrolled Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(26):2486–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, Brusselle GG, FitzGerald JM, Chetta A, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nair P, Wenzel S, Rabe KF,Bourdin A, Lugogo NL, Kuna P, et al. Oral Glucocorticoid-Sparing Effect of Benralizumab in Severe Asthma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(25):2448–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuttle KL, Buchheit KM, Laidlaw TM, Cahill KN. A retrospective analysis of mepolizumab in subjects with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(3):1045–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan R, RuiWen Kuo C, Lipworth B. Disconnect between effects of mepolizumab on severe eosinophilic asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(5):1714–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]