Abstract

There is a need to identify the subset of individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD) symptoms at greatest risk for transitioning from suicidal ideation to a suicide attempt. Contemporary models of suicide risk propose that the capability for suicide is necessary for moving from suicidal ideation to a suicide attempt. Few studies have examined dispositional capability factors for suicide, especially among individuals with BPD symptoms. One candidate may be the catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) Val158Met polymorphism given its influence on pain sensitivity and fear. This study examined the interactive relation of BPD symptoms and the COMT Val158Met polymorphism to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Fifty-nine treatment-seeking patients were recruited. Participants were administered a series of clinical interviews to evaluate BPD symptoms and suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Saliva samples were collected for genotyping. The relation between BPD symptoms and suicidal ideation was not influenced by the Val158Met polymorphism. However, among Val/Val carriers, the probability of a lifetime suicide attempt increased as BPD symptom severity increased. Findings provide preliminary support for the Val/Val variant as a dispositional factor that may increase risk for suicide attempts in BPD; however, results must be interpreted with caution until replication of findings occurs in larger samples.

Keywords: borderline personality disorder, genetics, risk factors, suicidal self-injurious behaviors, suicide risk

Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is characterized by severe instability and dysfunction across interpersonal, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral domains (Gunderson, 2001; Linehan, 1993). Individuals with BPD are frequent consumers of outpatient and inpatient psychiatric services (Zanarini et al., 2001), exhibit high levels of functional impairment (Grant et al., 2008; Skodol et al., 2002a), have high rates of co-occurring psychiatric disorders (Skodol et al., 2002b), and are at elevated risk for a variety of self-destructive and health-compromising behaviors (Linehan, 1993; Skodol et al., 2002b). In particular, BPD is associated with high rates of both suicide attempts (>70% of individuals with BPD report at least one lifetime suicide attempt; Turner et al., 2018; Zanarini et al., 2008) and mortality by suicide (10%; Work Group on Borderline Personality Disorder, 2001). Given the heightened risk for suicide in this population, research is needed to identify the subset of individuals with BPD symptoms who may be at greatest risk for more serious or lethal suicide attempts. One factor warranting attention may be gleaned from contemporary models of suicide risk.

Given that many proposed suicide risk factors are associated with suicidal ideation but not necessarily suicide attempts, recent suicide risk models have highlighted factors that are necessary for the transition from suicidal ideation to a suicide attempt (Klonsky et al., 2018). In particular, both the Three-Step Model of Suicide (3ST; Klonsky & May, 2015) and the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (ITS; Joiner, 2005) propose that suicide capability is a primary factor necessary for an individual to move from suicidal ideation to a suicide attempt. According to the 3ST, capability for suicide is comprised of acquired, practical, and dispositional components. Acquired capability develops over time as an individual habituates to pain and develops fearlessness about death through repeated exposure to painful and provocative experiences. Practical capability encompasses the logistical components that increase the ease with which an individual may employ lethal means (e.g., knowledge of, experience with, access to, or comfort with a firearm). Finally, dispositional capability is influenced by biological and genetic predispositions to fearlessness about death and pain tolerance (Klonsky & May, 2015).

The vast majority of research to date on suicide capability has focused on acquired capability (Chu et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2016), although researchers are also beginning to evaluate the role of practical capability (Anestis & Capron, 2018; Houtsma & Anestis, 2017). Notably, however, studies of dispositional capability and suicide are limited (Paashaus et al., 2019), with the few studies in this area relying on self-report methods (Anestis et al., 2018; Klonsky & May, 2015) or twin studies (Smith et al., 2012). Such designs severely limit the ability to rule out environmental explanations and to thereby distinguish dispositional from acquired capability. Aside from physiological or behavioral components of suicide, research is needed to understand genetic factors associated with suicide, including gene variation associated with fearlessness and pain tolerance that may be related to suicide attempts among individuals with BPD. One candidate may be the catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) Val158Met polymorphism given its impact on fear conditioning and pain sensitivity – the theorized central features of suicide capability.

COMT is involved in the breakdown of estrogen, catecholamines, and the neurotransmitters of dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. A common functional polymorphism (Val158Met) results in a large variation of COMT enzyme activity, with carriers of the homozygous Met/Met variant exhibiting 3–4 times lower neurotransmitter catabolic activity than carriers of the Val/Val variant (with the catabolic activity of heterozygote Val/Met carriers falling in between the homozygous variants). Studies show that the COMT Val158Met polymorphism is associated with responses to pain. Specifically, Val/Val carriers exhibit less thermal pain sensitivity than Val/Met and Met/Met carriers (Schmahl et al., 2012), whereas Met/Met carriers exhibit stronger pain-related fMRI signals in brain structures associated with pain processing (Loggia et al., 2011). Likewise, studies have shown that the Val/Val variant is associated with lower ratings of both pain and negative affective states associated with pain relative to the Met allele (Desmeules et al., 2012; Zubieta et al., 2003). With regard to fearlessness, studies show that the Met/Met variant is associated with higher levels of the personality trait of harm avoidance (Enoch et al., 2008; Hashimoto et al., 2007) and an increased startle response (suggesting greater fear conditioning potential relative to other variants; Montag et al., 2008). Together, these findings suggest that Val/Val carriers may have a greater dispositional capability for suicide due to decreased pain sensitivity and increased fearlessness. However, no research to date has examined this particular gene polymorphism in the context of personality disorder pathology (i.e., BPD symptoms) characterized by the presence of other multiple other suicide risk factors (i.e., emotion dysregulation, suicidal desire, nonsuicidal self-injury; Anestis et al., 2012; Hamza et al., 2012).

Therefore, the goal of this study was to examine the interactive association of BPD symptoms and the COMT Val158Met polymorphism with past-month suicidal ideation and lifetime suicide attempts. We predicted that, among Val/Val carriers, higher levels of BPD symptoms would be associated with a greater likelihood of reporting a lifetime suicide attempt, relative to Val/Met and Met/Met carriers. Conversely, given that dispositional capability is theorized to increase the risk for serious or lethal suicidal behavior versus suicidal desire, we predicted to only find a main effect of BPD symptoms on suicidal ideation. Hypotheses were evaluated within a high-risk sample of patients with substance use disorders (SUD) in residential SUD treatment – a population with elevated rates of both BPD and lifetime suicide attempts (Anestis et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2011).

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were 59 patients from a residential SUD treatment facility. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 58, with a mean age of 31.59 (SD = 10.09). The majority of the participants were men (n = 31, 52.5%), White (n = 51, 86.4%; African-American n = 8, 13.6%), single (n = 38, 64.4%), had a high school education or less (n = 25, 59.3%), had an annual income of less than $20,000 (n = 31, 52.5%), and were unemployed prior to entering treatment (n = 31, 52.5%). Clinical characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1 (see supplemental material for select characteristics of each individual participant).

Table 1.

Current diagnostic data across all participants.

| % (n) | |

|---|---|

| Borderline Personality Disordera | 40.7 (24) |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 40.7 (24) |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 33.9 (20) |

| Panic Disorder with/without Agoraphobia | 5.1 (3) |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 22.0 (13) |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | 16.9 (10) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 30.5 (18) |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | 45.8 (27) |

| Drug Use Disorder | 100 (59) |

| Past-month Suicidal Ideation | 59.3 (35) |

| Lifetime Suicide Attempt | 28.8 (17) |

| COMT | |

| Met/Met | 20.3 (12) |

| Val/Met | 44.1 (26) |

| Val/Val | 35.6 (21) |

Mean borderline personality disorder continuous score = 8.97 (SD = 5.37; scores range from 1 to 18).

2.2. Measures

BPD was assessed using the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV; Zanarini et al., 1996). For each symptom assessed, interviewers provide a score of 0 (absent), 1 (subthreshold), or 2 (threshold). Participants who receive a score of 2 on at least 5 symptoms and report that the endorsed symptoms have been present most of their adult lives and reflect aspects of their personality or temperament are given a diagnosis of BPD. A continuous BPD symptom severity score can also be calculated by summing scores obtained for each symptom. Given evidence that BPD may be best represented as a dimensional construct (Hopwood et al., 2018), we utilized a continuous representation of BPD. Past research indicates that the DIPD-IV demonstrates good inter-rater and test-retest reliability for the assessment of BPD (Zanarini et al., 2000), with an inter-rater kappa coefficient of .68 and a test-retest kappa coefficient of .69. Internal consistency in the current sample was acceptable (α = .84).

The suicidality portion of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Version 6.0 (MINI; Sheehan et al., 2009) was used to assess suicide outcomes. Specifically, the current study used items assessing lifetime suicide attempts and past-month suicidal ideation. These items provide dichotomous outcome variables representing the presence or absence of a lifetime suicide attempt and past-month suicidal ideation. The MINI has shown adequate reliability and validity in the assessment of psychiatric disorders, as well as strong test-retest and inter-rater reliability (Sheehan et al., 1997).

Other psychiatric diagnoses were assessed using the Diagnostic Interview for Anxiety, Mood, and OCD and Related Neuropsychiatric Disorders (DIAMOND; Tolin et al., 2018). The DIAMOND is a structured clinical interview that was designed to assess current and lifetime Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) psychiatric disorders. The DIAMOND demonstrates good test-retest and interrater reliability, as well as convergent validity with corresponding diagnostic self-report measures (Tolin et al., 2018).

Interviews were conducted by bachelors- or masters-level clinical assessors previously trained to reliability with the principal investigator (MTT) and co-investigator (KLG) on the DIPD-IV, MINI, and DIAMOND. Detailed information on each disorder was collected by interviewers, and all data were reviewed by the principal investigator. In the case of ambiguous responses, data were reviewed and discussed by the principal investigator and interviewer until a consensus was reached.

2.3. Genotyping

Saliva samples were submitted to the University of Mississippi Medical Center Molecular and Genomics Core Facility for isolation of DNA and genotyping. DNA was isolated using Invitrogen™ PureLink™ Genomic DNA Mini Kit. On average, each sample resulted in 3.5ug of total DNA or ~100 ng/ul. All samples were normalized to 50 ng/ul to perform an initial quality control evaluation of DNA based on PCR amplification of the human b-actin gene. All samples generated a single band as visualized on 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Subsequently, Taqman genotyping was performed using pre-designed Taqman SNP Genotyping Assay for COMT Val158Met (rs4680, Cat#4362691). TaqMan® is a PCR-based assay for detection of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that provides an accurate and reliable method of genotyping. The assay is based on two allele-specific fluorescent probes (VIC =Allele 1 and FAM=Allele 2) that are amplified and detected using a Real-Time PCR system (see supplemental material). Samples were prepared using iTaq™ Universal Probes Supermix and evaluated on a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real- Time PCR instrument. Allele calls were made using Bio-Rad CFX Manager Software.

2.4. Procedure

All procedures were reviewed and approved by applicable Institutional Review Boards. Data were collected as part of a larger, two-session study examining mechanisms underlying relapse risk among trauma-exposed patients with cocaine use disorders. This study only uses data collected from the first session. To be eligible for inclusion in the larger study, participants were required to: 1) have experienced a Criterion A traumatic event (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013); 2) meet criteria for current cocaine use disorder (although participants could also have other substance use disorders); 3) have a Mini-Mental Status Exam (Folstein et al., 1975) score of ≥ 24 (indicative of no significant cognitive impairment); 4) speak and understand English; and 5) have no current psychotic disorder (as determined by the DIAMOND; Tolin et al., 2018). Eligible participants were recruited for this study no sooner than 72 hours after entry into the facility to limit the possible interference of withdrawal symptoms on study engagement. Those who met inclusion criteria were provided with information about study procedures and associated risks, following which written informed consent was obtained. Following the provision of informed consent, participants were administered diagnostic interviews, completed a series of questionnaires, and provided a saliva sample for genotyping. Upon completion of this session, participants were reimbursed $25.

2.5. Data Analysis

Stata 15.0 was used for all data analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample. Firth-type penalized logistic regression models were used to examine the relations of participants’ BPD symptoms, COMT Val158Met polymorphism, and their interaction to past-month suicidal ideation (absent = 0, present =1) or lifetime suicide attempt (absent = 0, present = 1) using the FIRTHLOGIT Stata module (Coveney, 2008). Unlike maximum likelihood estimates, penalized logistic regression models produce unbiased estimates when the sample is small and events (e.g., lifetime suicide attempts) are rare (Heinze & Schemper 2002; Rahman & Sultana, 2017). COMT Val158Met was dummy coded to compare Val/Val carriers (reference group) with Val/Met and Met/Met carriers. For significant interactions, postestimation commands were used to calculate and plot the probability of each outcome for participants with and without BPD who were Val/Val, Val/Met, or Met/Met carriers. All tests were two-tailed, alpha = .05.

3. Results

A penalized logistic regression model showed that the odds of suicidal ideation increased significantly as the severity of BPD symptoms increased (OR = 1.23, 95% CI: [1.08, 1.41], p = .003). Odds of suicidal ideation among Val/Val carriers did not differ from Val/Met (OR = 0.33, 95% CI: [0.08, 1.34], p = .122) or Met/Met (OR = 0.22, 95% CI: [0.04, 1.19], p = .079) carriers. Tests of interactions showed that the association between BPD symptoms and odds of suicidal ideation did not differ significantly when comparting Val/Val carriers with the Val/Met (OR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.74, 1.30], p = .902) or Met/Met (OR = 1.02, 95% CI: [0.68, 1.54], p = .919) carriers.

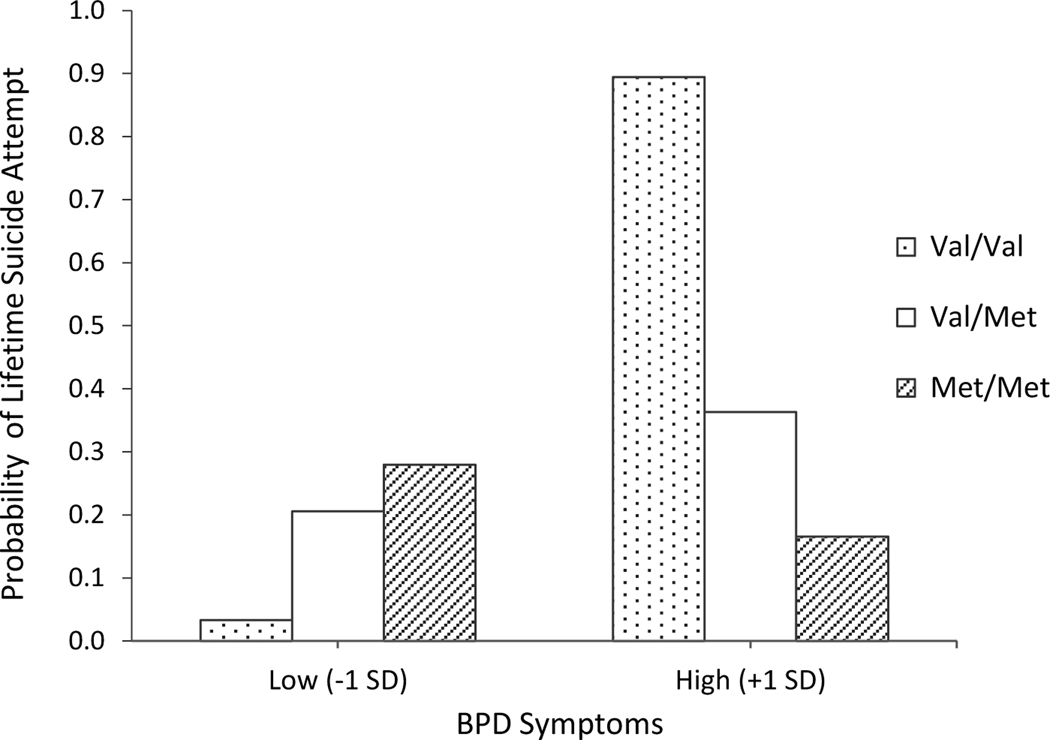

A penalized logistic regression model showed that the odds of lifetime suicide attempt increased significantly at higher levels of BPD symptoms (OR = 1.22, 95% CI: [1.07, 1.38], p = .002). Odds of lifetime suicide attempt among Val/Val carriers did not differ from Val/Met (OR = 0.49, 95% CI: [0.12, 1.94], p = .306) or Met/Met (OR = 0.27, 95% CI: [0.05, 1.57], p = .144) carriers. In addition, tests of interactions showed that the association between BPD symptoms and odds of lifetime suicide attempt was significantly greater among Val/Val carriers as compared to Val/Met (OR = 0.64, 95% CI: [0.42, 1.00], p = .048) or Met/Met (OR = 0.56, 95% CI: [0.34, 0.94], p = .027) carriers. Examination of conditional effects showed that the presence of a greater number of BPD symptoms was associated with significantly greater odds of a lifetime suicide attempt among Val/Val carriers, (OR = 1.67, 95% CI: [1.11, 2.51], p = .014). Specifically, among Val/Val carriers, each one-unit increase in BPD symptoms was associated with a 67% increase in the odds of a lifetime suicide attempt. However, BPD symptoms were not significantly associated with odds of a lifetime suicide attempt among Met/Val (OR = 1.08, 95% CI: [0.96, 1.26], p = .353) or Met/Met (OR = 0.94, 95% CI: [0.69,1.27], p = .687) carriers. Figure 1 depicts the relationship between BPD symptoms and the probability of lifetime suicide attempt among carriers of each COMT Val158Met polymorphism. Results did not change when a dichotomous representation of BPD was used.

Figure 1.

Probability of lifetime suicidal attempt status at low (−1 SD) and high (+1 SD) levels of BPD symptoms among Val/Val, Val/Met, and Met/Met carriers.

4. Discussion

This study is the first to investigate the interactive associations of BPD symptoms and the COMT Val158Met polymorphism with past-month suicidal ideation and lifetime suicide attempts. Consistent with hypotheses, although participants with more BPD symptoms had a greater probability of reporting past-month suicidal ideation, this relation was not influenced by the Val158Met polymorphism. However, a significant BPD symptom by COMT Val158Met polymorphism interaction was found for suicide attempt history, such that participants with higher levels of BPD symptoms who were also Val/Val carriers had a significantly greater probability of reporting a lifetime suicide attempt than all other of participants. Results provide support for the Val/Val variant as a dispositional factor that may increase risk for suicide attempts among individuals with elevated levels of BPD symptoms, and as such, are consistent with the ITS (Joiner, 2005) and 3ST (Klonsky & May 2015), which posit that suicide capability is necessary for the occurrence of a suicide attempt in the context of suicidal desire.

Notably, the Val/Val variant was only found to be associated with increased probability of a lifetime suicide attempt among those with higher levels of BPD symptoms. Multiple studies have examined the relation between the COMT Val158Met polymorphism and suicide, resulting in inconsistent findings (see González-Castro et al., 2018). Our findings suggest that this polymorphism is more likely to be associated with increased probability of having a lifetime suicide attempt in the presence of other risk factors for suicide. This finding is consistent with both the ITS (Joiner, 2005) and 3ST (Klonsky & May, 2015). Within these models, suicide capability is considered to be a necessary but not sufficient risk factor for suicide attempts. Specifically, in the absence of suicidal desire, increased dispositional fearlessness and decreased pain sensitivity are not expected to increase risk for suicide attempts. In some situations and contexts, these dispositional characteristics may even be advantageous. Indeed, although non-significant, the Val/Val variant was associated with lower odds of suicidal ideation and a lifetime suicide attempt relative to the Val/Met and Met/Met variants. However, in the context of suicidal desire, increased dispositional fearlessness and decreased pain sensitivity may increase the likelihood that an individual is able to enact lethal bodily harm and attempt suicide. Although our sample was characterized by high rates of psychopathology and previous traumatic exposure (which are associated with increased risk for suicidal desire and attempts; Goldney et al., 2000; Kelly et al., 2002; Pages et al., 1997), BPD is a psychiatric disorder that is particularly associated with a number of other risk factors for suicide attempts, including suicidal desire (Silva et al., 2015; Soloff et al., 2000; Van Orden et al., 2008), depression (McGlashan et al., 2000), and nonsuicidal self-injury (Gunderson, 2001; Hamza et al., 2012), the latter of which may increase the acquired capability for suicide (Anestis et al., 2012; Willoughby et al., 2015). Thus, in-line with the ITS (Joiner, 2005) and 3ST (Klonsky & May, 2015), although dispositional suicide capability was not associated with lifetime suicide attempt status, it moderated the association between BPD symptoms (which likely capture both heightened suicidal desire and factors that may increase the acquired capability for suicide) and the likelihood of a lifetime suicide attempt.

Findings should be considered in the context of study limitations. First, sample size was modest. Although confidence intervals associated with findings were reasonable, results must still be considered preliminary and interpreted with caution until replication studies utilizing larger samples are conducted. In addition, our cross-sectional design precludes any examination of the extent to which the presence of BPD and the Val/Val polymorphism facilitates the transition from suicidal ideation to a suicide attempt. Indeed, consistent with past studies that have retrospectively examined the relation between the COMT Val158Met polymorphism and suicide attempts (see Calati et al., 2011; Gonzáles-Castro et al., 2018), our findings can only speak to the presence of an association between the Val/Val polymorphism and past suicide attempts among individuals with elevated levels of BPD symptoms. In addition, the available data do not allow us to determine whether the act of a suicide attempt may somehow influence the transcription of COMT, thereby increasing the likelihood of future attempts. Although further research is needed to examine whether a suicide attempt may increase dispositional suicide capability, it is worth noting that Ribeiro et al. (2020) did not find evidence that suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors resulted in a change in suicide capability over a 28-day period. Likewise, although the presence of the Val/Val polymorphism was theorized to be associated with increased capability for suicide attempts via decreased pain sensitivity and increased fearlessness, we did not assess pain sensitivity or fearlessness of death in this study. Thus, we can only speculate as to how the Val/Val polymorphism may be associated with suicide attempts, and we do so with caution so as not to step too far beyond the scope of the present data. Future studies would benefit from the use of prospective designs, as well as the assessment of phenotypes associated with the Val/Val polymorphism.

This study also took a candidate gene approach. Although informed by the extant literature, such an approach limits the ability to determine whether other dispositional factors may be influencing our findings. Future studies may consider using a genome-wide association approach to identify a series of candidate genes that may influence capability for suicide among individuals with elevated BPD symptoms. Furthermore, although our findings are consistent with the notion that dispositional capability contributes to suicidal behavior, we focused on only one dimension of suicide capability outlined in the 3ST (i.e., dispositional capability) and did not assess or control for practical capability or the dimension of capability most prominent in the ITS – acquired capability. In addition, we did not assess for the key risk factors for suicidal desire outlined in the ITS, including perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. As such, we cannot rule out the possibility that our findings may be better explained by other aspects of suicide capability (e.g., acquired capability) or suicidal desire risk factors. Indeed, these factors may be particularly relevant to understanding suicide risk among individuals with elevated BPD symptoms, given research linking BPD to suicidal desire (Glenn et al., 2013; Linehan, 1993; Sansone, 2004), elevated levels of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (Eades et al., 2019; Rogers & Joiner, 2016; Silva et al., 2015), and elevated rates of exposure to a variety of painful and provocative events (e.g., traumatic events, nonsuicidal self-injury; Sinai et al., 2018; Soloff et al., 1994; Turner et al., 2015; Yen et al., 2002) that would be expected to increase the acquired capability for suicide in particular (Anestis et al., 2012; Willoughby et al., 2015). Additionally, some of the self-destructive and risky behaviors that are especially common among individuals with BPD, such as nonsuicidal self-injury (Soloff et al., 1994; Turner et al., 2015) and substance misuse (Trull et al., 2018), may also increase practical capability for suicide, as these behaviors may increase familiarity with and access to potential means for enacting lethal bodily harm. Thus, future studies are needed to examine the combined influence of thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and all suicide capability components on the association between BPD symptom severity and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts.

Additionally, due to sample size limitations, we were unable to compare individuals with a lifetime suicide attempt to individuals with suicidal ideation but no lifetime attempts. We also did not have data on lifetime suicidal ideation. Therefore, we cannot be certain that our findings related to suicide attempts truly differentiate those who think about suicide from those who act upon those thoughts rather than simply differentiating those with lifetime suicidal ideation from those with no history of suicidality. Finally, although our examination of hypotheses within a sample of patients with SUDs may be considered a strength of this study (given evidence of high rates of BPD and suicide attempts among patients with SUDs; Anestis et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2011), it is unclear if findings would generalize to other populations.

Despite limitations, results of this study have both research and clinical implications. First, results begin to add to the literature on suicide risk within BPD by highlighting a potential factor that may represent an inherent elevated capability for suicide within components of this population. Results also add to the small body of literature documenting the relevance of dispositional suicide capability to suicide risk. Consistent with the 3ST (Klonsky & May, 2015), dispositional suicide capability was found to be associated with suicide attempts but not suicidal ideation, thus highlighting the particular relevance of suicide capability to the risk for suicidal behaviors in particular. As such, this finding adds to the growing body of literature that seeks to understand factors that may explain the transition from suicidal ideation to suicide attempts (i.e., an ideation-to-action framework; see Klonsky et al., 2018).

As for the clinical implications of this research, results highlight the importance of considering dispositional capability when evaluating suicide risk among patients with BPD. Although it is likely not feasible within most clinical settings to evaluate for the presence of the Val/Val polymorphism, characteristics associated with this polymorphism could be evaluated, such as harm avoidance, trait anxiety, and pain sensitivity. Suicide risk is multiply-determined and effective suicide risk assessments consider a variety of factors theoretically and empirically shown to be associated with suicidal behavior. Evaluation of dispositional capability (along with other forms of suicide capability) can provide a more comprehensive representation of suicide risk factors, facilitating the early identification of individuals at heightened risk for transitioning from suicidal ideation to a suicide attempt. Early identification of patients at risk for a suicide attempt is an important step in the prevention of suicide within a clinical population characterized by multiple risk factors for suicide. Further, although interventions would not be expected to modify dispositional capability, interventions focused on reducing practical capability (e.g., reducing access to lethal means) could have a major impact on the likelihood that an at-risk patient transitions from ideation to action.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD) are at high risk for suicide.

Current suicide models suggest dispositional capability may explain this risk.

We examined COMT Val158Met polymorphism in the relation between BPD and suicide.

BPD-suicidal ideation relation was not influenced by the Val158Met polymorphism.

Lifetime suicide attempt more likely in Val/Val carriers with more BPD symptoms.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the IDeA Program of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, COBRE Center for Psychiatric Neuroscience (P30GM103328). The work performed through the UMMC Molecular and Genomics Facility is supported, in part, by funds from the NIGMS, including Mississippi INBRE (P20GM103476), Center for Psychiatric Neuroscience (CPN)-COBRE (P30GM103328), Obesity, Cardiorenal and Metabolic Diseases- COBRE (P20GM104357) and Mississippi Center of Excellence in Perinatal Research (MS-CEPR)COBRE (P20GM121334).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

All authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Declarations of interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington. [Google Scholar]

- Anestis JC, Anestis MD, Preston OC, 2018. Psychopathic personality traits as a form of dispositional capability for suicide. Psychiatry. Res 262, 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Capron DW, 2018. Deadly experience: The association between firing a gun and various aspects of suicide risk. Suicide. Life. Threat. Behav 48, 699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Gratz KL, Bagge CL, Tull MT, 2012. The interactive role of distress tolerance and borderline personality disorder in suicide attempts among substance users in residential treatment. Compr. Psychiatry 53, 1208–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calati R, Porcelli S, Giegling I, Hartmann AM, Möller HJ, De Ronchi D, Serretti A, Rujescu D, 2011. Catechol-o-methyltransferase gene modulation on suicidal behavior and personality traits: review, meta-analysis and association study. J. Psychiatr. Res 45, 309–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KW, Banducci AN, Guller L, Macatee RJ, Lavelle A, Daughters SB, Lejuez CW, 2011. An examination of psychiatric comorbidities as a function of gender and substance type within an inpatient substance use treatment program. Drug. Alcohol. Depend 118, 92–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Stanley IH, Hom MA, Tucker RP, Hagan CR, Rogers ML, Podlogar MC, Chiurliza B, Ringer-Moberg FB, Michaels MS, Patros C, Joiner TE, 2017. The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychol. Bull 143, 1313–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coveney J,2008. FIRTHLOGIT: Stata module to calculate bias reduction in logistic regression. Statistical Software Components. [Google Scholar]

- Desmeules J, Piguet V, Besson M, Chabert J, Rapiti E, Rebsamen M, Rossier MF, Curtin F, Dayer P, Cedraschi C, 2012. Psychological distress in fibromyalgia patients: A role for catechol-O-methyl-transferase Val158met polymorphism. Health. Psychol 31, 242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eades A, Segal DL, Coolidge FL, 2019. Suicide risk factors among older adults: exploring thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness in relation to personality and self-esteem. Int. J. Aging. Hum. Dev 88, 150–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch MA, White KV, Waheed J, Goldman D, 2008. Neurophysiological and genetic distinctions between pure and comorbid anxiety disorders. Depress. Anxiety 25, 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR, 1975. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Bagge CL, Osman A, 2013. Unique associations between borderline personality disorder features and suicide ideation and attempts in adolescents. J. Pers. Disord 27, 604–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldney RD, Wilson D, Grande ED, Fisher LJ, McFarlane AC, 2000. Suicidal ideation in a random community sample: attributable risk due to depression and psychosocial and traumatic events. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 34, 98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Castro TB, Hernández-Díaz Y, Juárez-Rojop IE, López-Narváez ML, Tovilla-Zárate CA, Ramírez-Bello J, Pérex-Hernández N, Genis-Mendoza AD, Fresan A, Guzmán-Priego CG, 2018. The role of COMT gene Val108/158Met polymorphism in suicidal behavior: Systematic review and updated meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat 14, 2485–2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, Smith SM, Dawson DA, Pulay AJ, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, 2008. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J. Clin. Psychiatry 69, 533–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG, 2001. Borderline personality disorder: A clinical guide. American Psychiatric Association, Arlington. [Google Scholar]

- Hamza CA, Stewart SL, Willoughby T, 2012. Examining the link between nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: A review of the literature and an integrated model. Clin. Psychol. Rev 32, 482–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto R, Noguchi H, Hori H, Ohi K, Yasuda Y, Takeda M, Kunugi H, 2007. A possible association between the Val158Met polymorphism of the catechol-O-methyl transferase gene and the personality trait of harm avoidance in Japanese healthy subjects. Neurosci. Lett 428, 17–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze G, Schemper M, 2002. A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Stat. Med 21, 2409–2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, Widiger TA, Althoff RR et al. , 2018. The time has come for dimensional personality disorder diagnosis. Personal. Mental. Health 12, 82–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtsma C, Anestis MD, 2017. Practical capability: The impact of handgun ownership among suicide attempt survivors. Psychiatry. Res 258, 88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, 2005. Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly TM, Cornelius JR, Lynch KG, 2002. Psychiatric and substance use disorders as risk factors for attempted suicide among adolescents: a case control study. Suicide. Life. Threat. Behav 32, 301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, May AM, 2015. The three-step theory (3ST): A new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. Int. J. Cog. Ther 8, 114–129. [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Saffer BY, Bryan CJ, 2018. Ideation-to-action theories of suicide: A conceptual and empirical update. Curr. Opin. Psychol 22, 38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM (1993). Cognitive behavioral therapy of borderline personality disorder. GuilfordPress, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Loggia ML, Jensen K, Gollub RL, Wasan AD, Edwards RR, Kong J, 2011. The catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) val158met polymorphism affects brain responses to repeated painful stimuli. PloS One. 6, e27764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Han J, 2016. A systematic review of the predictions of the Interpersonal–Psychological Theory of Suicidal Behavior. Clin. Psychol. Rev 46, 34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, Morey LC, Zanarini MC, Stout RL, 2000. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Baseline axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta. Psychiatr. Scand 102, 256–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montag C, Buckholtz JW, Hartmann P, Merz M, Burk C, Hennig J, Reuter M, 2008. COMT genetic variation affects fear processing: Psychophysiological evidence. Behav. Neurosci 122, 901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pages KP, Russo JE, Roy-Byrne PP, Ries RK, Cowley DS, 1997. Determinants of suicidal ideation: The role of substance use disorders. J. Clin. Psychol 58, 510–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paashaus L, Forkmann T, Glaesmer H, Juckel G, Rath D, Schönfelder A, Engel P, Teismann T, 2019. Do suicide attempters and suicide ideators differ in capability for suicide?. Psychiatry Res. 275, 304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MS, Sultana M, 2017. Performance of Firth-and logF-type penalized methods in risk prediction for small or sparse binary data. BMC Med. Res. Methodol 17, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JD, Harris LM, Linthicum KP, Bryen CP, 2020. Do suicidal behaviors increase the capability for suicide? A longitudinal pretest–posttest study of more than 1,000 high-risk individuals. Clin. Psychol. Sci 8, 890–904. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers ML, Joiner TE, 2016. Borderline personality disorder diagnostic criteria as risk factors for suicidal behavior through the lens of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Arch. Suicide Res 20, 591–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone RA, 2004. Chronic suicidality and borderline personality. J. Pers. Disord 18, 215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahl C, Ludäscher P, Greffrath W, Kraus A, Valerius G, Schulze TG, Treutlein J, Rietschel M, Smolka MN, Bohus M, 2012. COMT val158met polymorphism and neural pain processing. PloS One. 7, e23658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D, Janavs J, Baker R, Harnett-Sheehan K, Knapp E, & Sheehan M, 2009. Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Version 6.0. University of South Florida College of Medicine, Centre Hospitalier Sainte-Anne, Tampa, Paris. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, Schinka J, Knapp E, Sheehan MF, Dunbar GC, 1997. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. Eur. Psychiatry 12, 232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Silva C, Ribeiro JD, Joiner TE, 2015. Mental disorders and thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capability for suicide. Psychiatry Res. 226, 316–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinai C, Hirvikoski T, Wiklander M, Nordström AL, Nordström P, Nilsonne Å, Wilczek A, Åsberg M, Jokinen J, 2018. Exposure to interpersonal violence and risk of post-traumatic stress disorder among women with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res. 262, 311–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Dyck IR, Stout RL, Bender DS, Grilo CM, Shea MT, Zanarini MC, Morey LC, Sanislow CA, Oldham JM, 2002a. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 159, 276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, Widiger TA, Livesley WJ, Siever LJ, 2002b. The borderline diagnosis I: Psychopathology, comorbidity, and personaltity structure. Biol. Psychiatry 51, 936–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AR, Ribeiro JD, Mikolajewski A, Taylor J, Joiner TE, Iacono WG, 2012. An examination of environmental and genetic contributions to the determinants of suicidal behavior among male twins. Psychiatry. Res 197, 60–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloff PH, Lis JA, Kelly T, Cornelius J, Ulrich R, 1994. Self-mutilation and suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. J. Pers. Disord 8, 257–267. [Google Scholar]

- Soloff PH, Lynch KG, Kelly TM, Malone KM, Mann JJ, 2000. Characteristics of suicide attempts of patients with major depressive episode and borderline personality disorder: A comparative study. Am. J. Psychiatry 157, 601–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Gilliam C, Wootton BM, Bowe W, Bragdon LB, Davis E, Hannan SE, Steinman SA, Worden B, Hallion LS, 2018. Psychometric properties of a structured diagnostic interview for DSM-5 anxiety, mood, and obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. Assess. 25, 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Freeman LK, Vebares TJ, Choate AM, Helle AC, Wycoff AM, 2018. Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: an updated review. Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregul 5, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BJ, Dixon-Gordon KL, Austin SB, Rodriguez MA, Rosenthal MZ, Chapman AL, 2015. Non-suicidal self-injury with and without borderline personality disorder: differences in self-injury and diagnostic comorbidity. Psychiatry Res. 230, 28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BJ, Jin HM, Anestis MD, Dixon-Gordon KL, Gratz KL, 2018. Personality pathology and intentional self-harm: Cross-cutting insights from categorical and dimensional models. Curr. Opin. Psychol, 21, 55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, Joiner TE, 2008. Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: Tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 76, 72–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby T, Heffer T, Hamza CA, 2015. The link between nonsuicidal self-injury and acquired capability for suicide: A longitudinal study. J. Abnorm. Psychol 124, 1110–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Work Group on Borderline Personality Disorder, 2001. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen S, Shea MT, Battle CL, Johnson DM, Zlotnick C, Dolan-Sewell R, Skodol AE, Grilo C, Gunderson JG, Sanislow CA, Zanarini MC, Bender DS, Rettew JB, McGlashan TH, 2002. Traumatic exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in borderline, schizotypal, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: fingings from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 190, 510–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Khera GS, Bleichmar J, 2001. Treatment histories of borderline inpatients. Compr. Psychiatry 42, 144–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G, Weinberg I, Gunderson JG, 2008. The 10-year course of physically self-destructive acts reported by borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 117, 177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Sickel AE, Yong L, 1996. The Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV). McLean Hospital, Belmont. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, Morey LC, Grilo CM, Shea MT, McGlashan TH, Gunderson JG, 2000. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Reliability of axis I and II diagnoses. J. Personal. Disord 14, 291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Heitzeg MM,Smith YR, Bueller JA, Xu K, Xu Y, Koeppe RA, Stohler CS, Goldman D, 2003. COMT val158met genotype affects μ-opioid neurotransmitter responses to a pain stressor. Science. 299, 1240–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.