In 30% of patients, common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is associated with noninfectious manifestations such as enteropathy, interstitial lung disease, granuloma, splenomegaly, autoimmunity, malignancy, and liver disease.1 Liver disease typically involves nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH), granulomatous hepatopathy, and less frequently, autoimmune hepatitis.2,3 Although liver function is often preserved, most patients with NRH present with portal hypertension associated with the development of ascites and esophageal varices that can cause life-threatening upper-gastrointestinal bleeding.4

Variceal bleeding and recurrent ascites are major indications for the implantation of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in patients with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension.5 Whether TIPS implantation is also a feasible option to treat CVID patients who develop complications of portal hypertension is currently addressed only in individual case reports.6

We therefore retrospectively collected the clinical data of 13 CVID patients from five clinical centers in Europe and North America who were treated with TIPS implantation. Patients’ laboratory, clinical, ultrasound, and endoscopy data were exported and manually validated from the hospital information systems of the respective centers. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Freiburg (FR354/19).

Nine patients experienced NRH; two had granulomatous liver disease, one had cryptogenic cirrhosis, and one had hepatitis C–related liver cirrhosis (Table I). For the 13 patients, the indication for TIPS implantation was secondary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in five (39%), large and persisting varices despite endoscopic band ligation in six (46%), portal hypertensive gastropathy in one (7.7%) and hepatopulmonary syndrome in one (7.7%). Five patients (39%) also had clinically relevant ascites (Table I). Two TIPS implantations were performed as early implantations (within 72 hours of variceal bleeding). All patients showed splenomegaly; none had a history of hepatic encephalopathy. Seven patients were treated with β-blockers, and 11 with diuretics (Table II) before TIPS implantation.

TABLE I.

Patient characteristics.NA= not available, X= none, “unknown” may refer to not available or no relevant mutation identified

| ID | Sex | First diagnosis of CVID (age, y) | First manifestation of CVID (age, y) | Genetics | Gastrointestinal disease | Spleen diameter before TIPS, cm | First diagnosis of liver disease (age, y | Etiology of liver disease | Indication for TIPS | Age at TIPS, y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freiburg-1 | F | 39 | 6 | Unknown | Previous bacterial GI infection, chronic norovirus infection | Splenectomy 2006 | 51 | Granulomatous liver disease with epithelioid cell granuloma | Varices | 51 |

| Freiburg-2 | F | 48 | 38 | Unknown | Previous bacterial GI infection | 7 × 20 | 56 | Nodular regenerative hyperplasia | Ascites, varices | 61 |

| Freiburg-3 | F | 42 | 39 | Unknown | X | 7 × 20 | 52 | Nodular regenerative hyperplasia | Varices, early TIPS implantation after recurrent variceal bleeding with hemorrhagic shock and esophagus perforation | 52 |

| Freiburg-4 | F | 34 | 3 | Unknown (no relevant mutation identified) | Previous infection with lamblia, celiac like disease | 5.1 × 14.25 | 40 | Nodular regenerative hyperplasia | Varices | 43 |

| Freiburg-5 | M | 15 | NA | ICOS Ex2–3 DEL | X | 7.5 × 17.6 | 53 | Nodular regenerative hyperplasia | Varices | 54 |

| Freiburg-6 | M | 35 | 28 | het NFKB1 p.W294C | Celiac-like disease | 7.2 × 19.6 | 63 | Nodular regenerative hyperplasia | Early TIPS implantation owing to postoperative wound healing problems caused by ascites after incarcerated umbilical hernia, varices | 63 |

| Freiburg-7 | M | 40 | 26 | het NFKB1 p.Y89S | X | 5.9 × 17.5 | 40 | Hepatitis C virus associated liver cirrhosis | Subacute portal vein thrombosis | 62 |

| Freiburg-8 | F | 33 | 28 | het TACI p.A181E | Undefined enteropathy | 9 × 17 | 55 | Cryptogenous liver cirrhosis differential diagnosis toxic with unclear toxin | Varices | 57 |

| Rome-1 | F | 44 | 10 | Unknown | Previous bacterial GI infection | Longitudinal diameter: 31.4 | 55 | Nodular regenerative hyperplasia | Ascites, varices | 63 |

| Aarhus-1 | F | 35 | 29 | Without relevant findings | X | 21 × 10 × 25 | 46 | Nodular regenerative hyperplasia, autoimmune hepatitis | Ascites, varices | 49 |

| Aarhus-2 | M | 22 | 10 | Without relevant findings | X | 26.6 × 23.8 | 41 | Nodular regenerative hyperplasia | Ascites, varices | 52 |

| Lisbon-1 | M | 38 | 18 | Unknown | Previous bacterial GI infection, previous infection with lamblia, celiac-like disease | 22 | 38 | Nodular regenerative hyperplasia | Ascites, varices, hypertensive gastropathy | 48 |

| New York-1 | F | 24 | 21 | STAT3 GOF pArg246Gln | Previous infection with Entamoeba histolytica | Splenectomy 1994 | 33 | Granulomatous liver disease | Hepatopulmonary syndrome | 51 |

GI, gastrointestinal; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

TABLE II.

Clinical and laboratory parameters before and after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt implantation and follow-up

| ID | Varices before TIPS | Ascites before TIPS | Bacteremia/sepsis before TIPS | Treatment for portal hypertension | TIPS open in duplex ultra sound | Vmax portal vein before TIPS, cm/s | Vmax portal vein after TIPS, cm/s | Portosystemic gradient before TIPS, mm Hg | Portosystemic gradient after TIPS, mm Hg | Periinterventional complications | Change in leukocytes after TIPS implantation (×103/μL) | Change in platelets after TIPS implantation (×103/μL) | Change in hemoglobin after TIPS implantation, g/dL | Change in bilirubin after TIPS implantation, mg/dL | Time point of follow-up after TIPS implantation, d | Degree of hepatic encephalopathy (West Haven classification) | Ascites | Vmax TIPS, cm/s | Vmax Portal vein, cm/s | Spleen diameter, cm | Treatment for portal hypertension | Deceased (days after TIPS implantation) | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freiburg-1 | Varices | Moderate | None | None | Yes | X | X | 15 | 7 | No | 0.5 | −80 | 3.7 | 0 | 371 | No | None | 200 | X | Removed | No | No, 2273 d (LV) | |

| Freiburg-2 | X | Moderate | None | Torsemide, spirono lactone | Yes | X | 60 | 26 | 10 | No | −1.2 | −26 | −0.4 | 2 | 299 | No | Moderate | 50 | 20 | 6 × 17 | Torsemide, spironolactone | Yes, 1213 d | Septic shock with multiorgan failure due to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis with detection of E coli |

| Freiburg-3 | Variceal bleeding | None | None | Amiloride, HCT | X | X | X | 13 | 3 | No | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Yes, 483 d | Septic shock due to smoldering mediastinitis after esophageal perforation, multiple pathogens |

| Freiburg-4 | Varices | None | None | Spirono lactone, propranolol | X | 16.7 | 33.6 | 24 | 11 | No | 6.3 | 36 | −1.3 | 1.2 | 512 | Yes, 1° (L-ornithine, L-aspartate) | Moderate | 130 | 27 | 4.6 × 13.7 | Triamterene, HCT | Yes, 688 d | Multiorgan failure due to Staphylococcus aureus sepsis |

| Freiburg-5 | Variceal bleeding | Moderate | None | Spirono lactone, carvedilol | Yes | 29.7 | 30 | 20 | 13 | Fever with unclear focus | 3.6 | 50 | 4.3 | −0.3 | 660 | No | Moderate | 72 | 23 | 5.5 × 16.9 | No | No, 1192 d (LV) | |

| Freiburg-6 | Varices | Moderate | None | Torsemide, spirono lactone, propranolol | Yes | 23 | 26 | 23 | 3 | Severe liver dysfunction, Escherichia coli bacteremia | 0.5 | 3 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 35 | No | None | 130 | 40 | 11.8 × 22.9 | Torsemide | Yes, 160 d | Staphylococcus haemolyticus sepsis |

| Freiburg-7 | Variceal bleeding | None | None | Spirono lactone, propranolol | Yes | 16.9 | 33 | 29 | 12 | No | −2.4 | −13 | −0.9 | X | 271 | No | None | 147 | X | 6.7 × 19.4 | X | No, 445 d (LV) | |

| Freiburg-8 | Varices | Moderate | None | Torsemide, spirono lactone, propranolol | Yes | 13 | X | 21 | 10 | No | 0.5 | 37 | −1.6 | X | 421 | Yes, 2° (lactulose, L-ornithine, L-aspartate) | Moderate | 113 | 44.9 | 6.5 × 14.4 | Spironolactone | No, 948 d (LV) | |

| Rome-1 | Varices | Severe | None | Furosemide, spirono lactone | Yes | 13.3 | 14.6 | 31 | 28 | Acute respiratory failure | 0.3 | −11 | 0 | 0.4 | 7 | No | Moderate | 127.2 | 14.6 | 27.9 | Furosemide, spironolactone | Yes, 180 d | Sepsis, interstitial pneumonia, and cardiac and hepatic failure |

| Aarhus-1 | Variceal bleeding | Moderate | None | Spirono lactone, furosemide, propranolol | Yes (8th of July 2015) | X | X | 22 | 16 | No | 6.0 | 9 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 643 | Yes, 2°, only short episode after TIPS | Moderate | 130 | X | X | Spironolactone, furosemide | No, 1624 d (LV) | |

| Aarhus-2 | Variceal bleeding | Moderate | None | Spirono lactone, furosemide, propranolol | Yes (8th of February 2019) | X | X | 22 | 16 | No | 1.1 | −2 | 4.5 | 1.2 | 442 | No | Moderate | 130 | X | 19 | Spironolactone, furosemide | No, 442 d (LV) | |

| Lisbon-1 | Varices | Severe | Yes | Furosemide, spirono lactone | Yes | 11.8 | 30 | 17 | 10 | No | 0.9 | 0 | 1.3 | 1.38 | 68 | No | Moderate | X | 30 | 19 | Furosemide | Yes, 69 d | Multiorgan failure due to E coli sepsis |

| New York-1 | None | Moderate | Yes | None | X | X | X | X | X | No | 3.8 | 159 | −3.4 | 0 | 2902 | Yes, 2° | None | X | X | Removed | No | No, 2902 d (LV) |

HCT, hydrochlorothiazide; LV, last visit; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; Vmax, maximal blood flow velocity; X, information not available.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt implantation reduced the portosystemic gradient in 12 of 13 patients (mean portosystemic gradient before TIPS, 21.9 mm Hg ± 5.3 vs 11.6 mm Hg ± 6.6 after TIPS; P < .001), and on color Doppler ultrasound the Vmax of the portal vein increased (mean Vmax before: 17.8 cm/s ± 6.5 vs mean Vmax after: 32.5 cm/s ± 13.7; P = .03).

Immediately after TIPS implantation, one patient had a fever of unknown origin, one experienced severe liver dysfunction, and one had respiratory failure (Table II). Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt revision occurred in two of 13 patients (15.4%); in patient Freiburg-4 it took place after 637 days owing to shunt thrombosis and the subsequent recurrence of varices and ascites. Patient Rome-1 underwent a TIPS revision 60 days after TIPS implantation because of the recurrence of ascites, which responded to medical treatment. In all other patients, during a mean follow-up of 948 days, there were no signs of TIPS dysfunction, including TIPS stenosis or thrombosis.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt implantation was able to prevent further variceal bleeding in all patients. The spleen size decreased in six patients, although not to normal size. Moderate ascites was detected in eight of 10 patients, but required no intervention. β-Blocker therapy was discontinued in all patients. After TIPS implantation, four patients showed signs of hepatic encephalopathy grades I to II (Table II). Interestingly, five of nine patients (56%) had higher levels of immunoglobulin G after TIPS implantation despite the unchanged immunoglobulin G replacement dose (data not shown). The increase in leukocytes in most patients, but less consistently in platelets and hemoglobin after TIPS implantation, was ascribed to a reduction of splenomegaly and thus hypersplenism. The increase in bilirubin after TIPS implantation (mean before: 1.3 mg/dL; after: 2.2 mg/dL; P < .05) may have been caused by a delayed development of the hepatic buffer response (increased arterial perfusion) owing to the hemodynamic alterations. In the general TIPS population, liver enzymes have been shown to increase within 2 to 5 days of TIPS implantation in patients with acute hepatic decompensation, but to normalize within a month.7

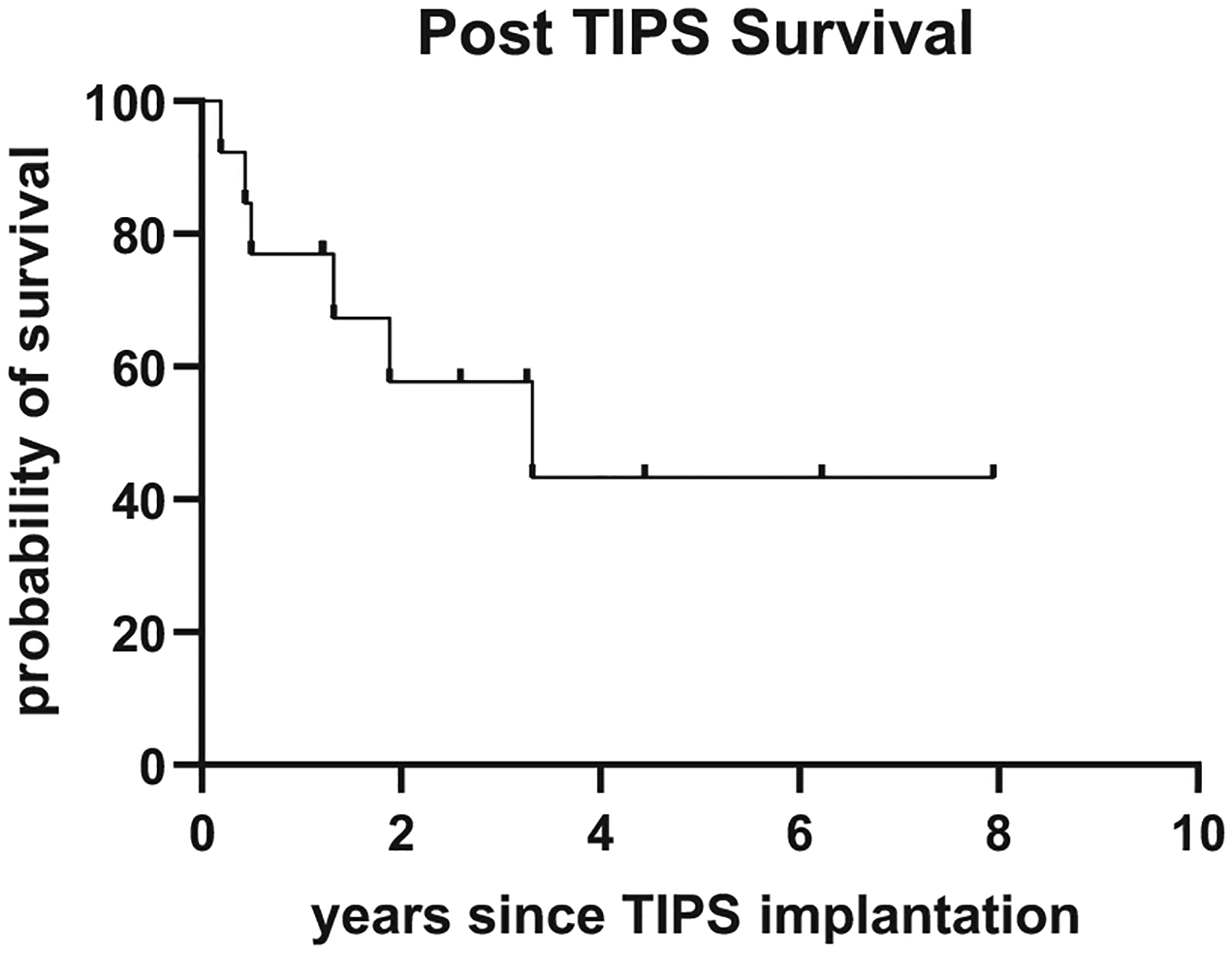

Six of 13 patients died during the follow-up (Table II): two patients died of septic shock and multiorgan failure as a result of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis with detection of Escherichia coli; another patient died of septic shock owing to smoldering mediastinitis after esophagus perforation with intestinal translocation and detection of E coli, Enterobacter cloacae, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and Enterococcus faecium. One patient died of multiorgan failure owing to Staphylococcus aureus sepsis with a pulmonary focus; another patient died of sepsis, interstitial pneumonia, and cardiac and hepatic failure. A final patient died soon after TIPS implantation, from Staphylococcus haemolyticus sepsis; his death was therefore classified as procedure-related. Given the low incidence of sepsis in CVID, it is remarkable that six of 13 patients died of sepsis after implantation of TIPS. We speculate that the impaired gastrointestinal barrier in CVID patients might lead to bacterial translocation that would normally be intercepted in the liver more efficiently, preventing bacteria from reaching the systemic bloodstream. In the general TIPS population, infectious non–procedure-related complications have been observed in 5.1% of patients; spontaneous bacterial peritonitis occurred in 0.8% of patients.7 Median survival after TIPS in the general TIPS population was reported to be 33.9 months,7 as opposed to 39.84 months in the current cohort (see Figure E1 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). In patients with idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension treated with TIPS implantation, bacteremia was reported in 5% and variceal rebleeding in 7%, and 27% of patients died within 5 years after TIPS.8 Moreover, 18% of patients who died had sepsis or multiorgan failure.6,8 The reported outcome for idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension patients was affected by extrahepatic conditions.8 Because these are regularly seen in CVID patients with portal hypertension (data not shown), they may contribute to the high mortality observed in the current patient cohort. The high mortality of the procedure observed in this cohort calls for a control cohort. However, this is difficult to obtain, because the procedure is taken as the last step of treatment for insufficiently controlled portal hypertension.

FIGURE E1.

Kaplan-Meier plot depicting survival of common variable immunodeficiency patients after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) implantation.

In the absence of better alternatives, and considering mixed outcomes after liver transplantation in CVID patients with a reduced survival compared with non-CVID patients, increased susceptibility to infections, and early disease recurrence,9 TIPS remains a valid treatment option for CVID patients with relevant portal hypertension owing to hepatopathy (mostly NRH). Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt implantation effectively controlled the risk for variceal rebleeding in all patients up to 8 years after implantation. Nevertheless, there was a highly relevant risk for death owing to sepsis even up to almost 4 years after implantation, which requires better ways of prevention, possibly by adding antibiotic prophylaxis.

Clinical Implications.

Portal hypertension owing to liver disease can be a clinically significant complication in patients with common variable immunodeficiency. A transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt can provide symptomatic relief, but an increased risk for septic complications that led to death in six of 13 patients within 5 years needs to be addressed.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF), Grant No. BMBF 01EO1303. AMG, MH, and DB were supported by the Berta-Ottenstein-Programme for Clinician Scientists, and VS by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, SFB1160, Impath, Project A04).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Dr Globig reports travel grants from AbbVie and Janssen. Dr Larsen received lecture and conference fees from Behring and Shire/Takeda; was the PI in the Hyqvia study; conducted the CSL-Behring-SQ Device Clinical trial; and received a Behring speaker honorarium. Dr Cunningham-Rundles conducted the CSL-Behring-SQ Device Clinical trial; was a consultant for Atara Biotherapeutics; wrote a manuscript for Shire/Takada; was on the advisory committee for UCB Biosciences and Momenta; and was a consultant to the advisory committee for Pharming. Dr Bettinger was consultant for Bayer Healthcare and Boston Scientific and a lecturer for the Falk Foundation. Dr Schultheiß was on the advisory committees of Bayer Healthcare and the Falk Foundation, wrote a manuscript, and received lecture fees. Dr Warnatz received a CSL-Behring speaker honorarium. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonilla FA, Barlan I, Chapel H, Costa-Carvalho BT, Cunningham-Rundles C, de la Morena MT, et al. International Consensus Document (ICON): common variable immunodeficiency disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2016;4:38–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pecoraro A, Crescenzi L, Varricchi G, Marone G, Spadaro G. Heterogeneity of liver disease in common variable immunodeficiency disorders. Front Immunol 2020;11:338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuss IJ, Friend J, Yang Z, He JP, Hooda L, Boyer J, et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia in common variable immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol 2013;33:748–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reshamwala PA, Kleiner DE, Heller T. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia: not all nodules are created equal. Hepatology 2006;44:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Franchis R Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2015;63:743–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regnault D, d’Alteroche L, Nicolas C, Dujardin F, Ayoub J, Perarnau JM. Ten-year experience of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;30:557–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bettinger D, Schultheiss M, Boettler T, Muljono M, Thimme R, Rössle M. Procedural and shunt-related complications and mortality of the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS). Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;44:1051–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bissonnette J, Garcia-Pagán JC, Albillos A, Turon F, Ferreira C, Tellez L, et al. Role of the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of severe complications of portal hypertension in idiopathic noncirrhotic portal hypertension. Hepatology 2016;64:224–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azzu V, Elias JE, Duckworth A, Davies S, Brais R, Kumararatne DS, et al. Liver transplantation in adults with liver disease due to common variable immunodeficiency leads to early recurrent disease and poor outcome. Liver Transpl 2018;24:171–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]