Abstract

Colanic acid is a glycopolymer loosely associated with the outer membrane of Escherichia coli that plays a role in pathogen survival. For nearly six decades since its discovery, the functional identities of the enzymes necessary to synthesize colanic acid have yet to be assessed in full. Herein, we developed a method to detect the lipid-linked intermediates from each step of colanic acid biosynthesis in E. coli. The accumulation of each enzyme product was made possible by inactivating sequential genes involved in colanic acid biosynthesis and upregulating the colanic acid operon by inducing rcsA transcription. LC-MS analysis revealed that these accumulated materials were consistent with the well-documented composition analysis. Recapitulating the native bioassembly of colanic acid enabled us to identify the functional roles of the last two enzymes, WcaL and WcaK, associated with the formation of the lipid-linked oligosaccharide repeating unit of colanic acid. Importantly, biochemical evidence is provided for the formation of the final glycosylation hexasaccharide product formed by WcaL and the addition of a pyruvate moiety to form a pyruvylated hexasaccharide by WcaK. These findings provide insight toward the development of methods for the identification of enzyme functions during cell envelope synthesis.

Keywords: Colanic acid, LC-MS, Capsule, bactoprenyl phosphate, undecaprenyl phosphate, cell envelope

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The bacterial cell envelope is a formidable barrier providing protection from numerous environmental stressors, antimicrobials, and host immune systems. Surface polysaccharides comprise a major component of the cell envelope and play specific roles in mediating cell adhesion, immune system evasion, and biofilm formation, among other important physiological functions that are central to bacterial proliferation.1 The exopolysaccharide colanic acid confers protection to members of the Enterobacteriaceae family such as Escherichia coli while in inhospitable environments, including providing protection against desiccation, oxidative stress, and low pH.2–4 Colanic acid may also act as a scaffold for biofilm formation.5 First reported nearly 60 years ago, all but the last two steps associated with colanic acid production have been elucidated to date.6, 7 Corroborating genetic predictions with biosynthetic function is important not only to characterize enzymatic activity, but also to identify conditions in which colanic acid can be produced in controlled environments.

The colanic acid operon contains genes encoding six glycosyltransferases and three sugar modifying enzymes that lead to the production of the repeating unit pyruvylated hexasaccharide (Figure 1).8 Like many bacterial surface glycans, colanic acid is produced on the scaffold bactoprenyl phosphate (BP), a 55-carbon isoprenoid with eight E- and two Z- configuration isoprene units. The identification of the first six enzymatic roles associated with early stages of colanic acid bioassembly were previously identified with a nonnative fluorescently-modified polyisoprenoid.7 In vitro reconstitution revealed that sequential glycosylation and modification of the polyisoprenoid led to the formation of the diacetylated pentasaccharide. The putative galactose transferase, WcaL, and subsequent pyruvylation by WcaK remain unconfirmed in vitro to date. It is not clear whether the inactivity of these last two steps was due to the unnatural lipid substrate used to characterize each step, or perhaps other reasons associated with glycan bioassembly in vitro.

Figure 1.

Bioassembly of the colanic acid repeating unit. Bactoprenyl monophosphate, a common lipid carrier, is comprised of five-carbon isoprenoid building blocks (either E or Z double bond configuration). The colanic acid repeating unit is assembled on bactoprenyl phosphate and is comprised of glucose, two fucoses, two galactoses, and a glucuronic acid. Nine glycosyltransferases or glycan-modifying enzymes have been implicated in the production of the pyruvylated hexasaccharide. However, the function of the enzymes WcaL and WcaK have not been reconstituted in vitro. The repeating unit is flipped by WzxC to the periplasm and polymerized by WcaD before exportation to the cell surface by a Wza transporter.

Various superfluous artifacts can arise during in vitro bioassays. Relaxed substrate specificity of glycans has been observed with some glycosyltransferases.9–11 For instance, the initiating phosphoglycosyltransferase WbaP from Salmonella enterica transfers phospho-glucose, a non-native substrate, in vitro but does not extensively catalyze this reaction in vivo.11, 12 Membrane-associated proteins are notoriously difficult to express and purify for several reasons that include unstable plasmids, toxic proteins, low yields, and inclusion body formation (i.e., misfolded proteins).13, 14 Similarly, obtaining naturally occurring lipid-linked intermediates from live cells is challenging due to competition for BP and the lack of methods available to detect these materials.15 Some essential cell envelope intermediates are present in detectable quantities but it is not known if non-essential surface glycans like colanic acid are also sequentially accumulated.15, 16 Increasing capsule production by modifying regulatory genes has been shown to enhance mucoid phenotypes associated with colanic acid production.12, 17–19 However, genetic disruption of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis negatively affects cell physiology.20, 21 This is explained by sequestration of BP in the form of over-accumulation of dead-end intermediates and also the reduction of free BP for peptidoglycan cell wall synthesis, an essential component of the cell envelope.

Methods for detecting lipid-linked oligosaccharide intermediates have recently been reported by our group. Enterobacterial Common Antigen was elucidated by coupling deletion mutants with LC-MS detection.22 Therefore, we hypothesized that it might also be possible to detect colanic acid intermediates by utilizing a similar approach. Lipid-linked oligosaccharides were extracted from cells containing a single deletion of each gene involved in colanic acid synthesis. These were compared to in vitro synthesized intermediates which served as standards.7 Lastly, we corroborated the in vitro activity of the last two steps of colanic acid biosynthesis with genetic analysis. This could address whether isolated enzymes could indeed use native substrates, or if other problems were present with substrate recognition. Our findings provide methods to reconstruct early stages of non-essential surface glycan synthesis as they exist in nature.

Materials and Methods

Standard Growth and Lysis of Mutants

A single colony selected from agar plates incubated overnight at 37 °C was used to inoculate 5 mL of modified TB media.23 The media composition included: 2.4 % yeast extract, 2.0 % tryptone, 0.5 % glycerol, 100 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM IPTG, and 10 μg/mL tetracycline. Cultures were incubated at 25 °C with shaking (300 rpm) for 22 h and then harvested with centrifugation. Cell pellets were washed with 0.9 % NaCl after which the supernatant was decanted. Cells were then resuspended in 700 μL water (approx. total volume ~800 μL) and transferred to glass tubes with 3 mL of Methanol:Chloroform (2:1) for 20 min to ensure complete lysis. Glass tubes were then placed in a CentriVap allowed to spin for an additional 20 min without vacuum. The soluble supernatant was then transferred to new glass tubes and placed at −80 °C until a slurry formed. Tubes were then placed back on the CentriVap with vacuum and dried to completion. The crude cell lysate was then stored in 200 μL of n-propanol and 0.1 % ammonium hydroxide (1:3) at − 20 °C for up to one month.

Two Phase Extraction of Crude Cell Lysates

To assess partition of colanic acid intermediates, cells were grown and lysed as described above. Additional water and chloroform was added to induce a two phase mixture (1.8:2:2 total Water: Methanol:Chloroform). The phases were placed in a CentriVap and spun for 20 min and the upper methanol/aqueous phase was transferred to a new glass tubes and then dried to completion. The aqueous fractions were then resuspended in 2 mL water and extracted with an equal volume of n-butanol in a second step. The resulting emulsion was placed on a CentriVap and spun for 20 min and the upper organic phase was transferred to a new glass tube. All dried fractions (Chloroform, Aqueous, and n-Butanol) were stored in in 500 μL of n-propanol and 0.1 % ammonium hydroxide (1:3) at − 20 °C.

LC-MS Analysis of Cell Lysates and in vitro Materials

Samples were analyzed on an Agilent 1260 Infinity II system equipped with a single quadrupole electrospray ionization MS detector. A high-pH stable Waters Xbridge Peptide BEH C18 column (4.6 × 50 mm with 2.5 μM particle size) was used for separation. The mobile phases used included 0.1% Ammonium Hydroxide (A) and n-propanol (B), unless otherwise stated. A gradient was used to separate oligosaccharides starting at 5% B which was increased to 65% over 10 min at 1 mL/min. All LC-MS runs were performed in negative ion mode with a peak width of 0.1 min. Samples were analyzed in both scanning mode (500–2,000 m/z) as well as selected ion mode (SIM) for either the [M-1H]−1 or [M-2H]−2 ion species as indicated. The highest peak in the SIM chromatogram was then used to identify the time in the scan used for extracted ion counts spectrum and to monitor for other ion species. A fragmentor voltage of 240 V was used for BPP or BP, and 100 V for oligosaccharide intermediates and during the scan. Unless otherwise stated, 5 μL of each sample following resuspension was injected.

In vitro Activity Assays with Cell Extracts

A 20 μL aliquot of the cell extract was dried under a gentle stream of air. The crude cell material was resuspended in 100 mM Bicine (pH 8), 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 1% Triton X-100 then sonicated briefly. The enzyme, WcaL or WcaK, was added at 10 μg total protein with either 5 mM UDP-Gal or 10 mM PEP, respectively. The total volume for each reaction was 40 μL. Reactions were left overnight at room temperature and analyzed following the above described LC-MS methods.

Morphological analysis of colanic acid deletion mutants

Overnight cultures were diluted 1:200 in TB media containing carbenicillin (to select for puppS), 1 mM IPTG (to induce uppS expression), and tetracycline (to induce rcsA expression), and grown at 25 °C for 5 h. Live cells were spotted on 1% agarose pads and imaged by phase-contrast microscopy using an Olympus BX51 microscope fitted with an XM10 monochrome camera.

Results & Discussion

In vitro Preparation of Colanic Acid Pentasaccharide

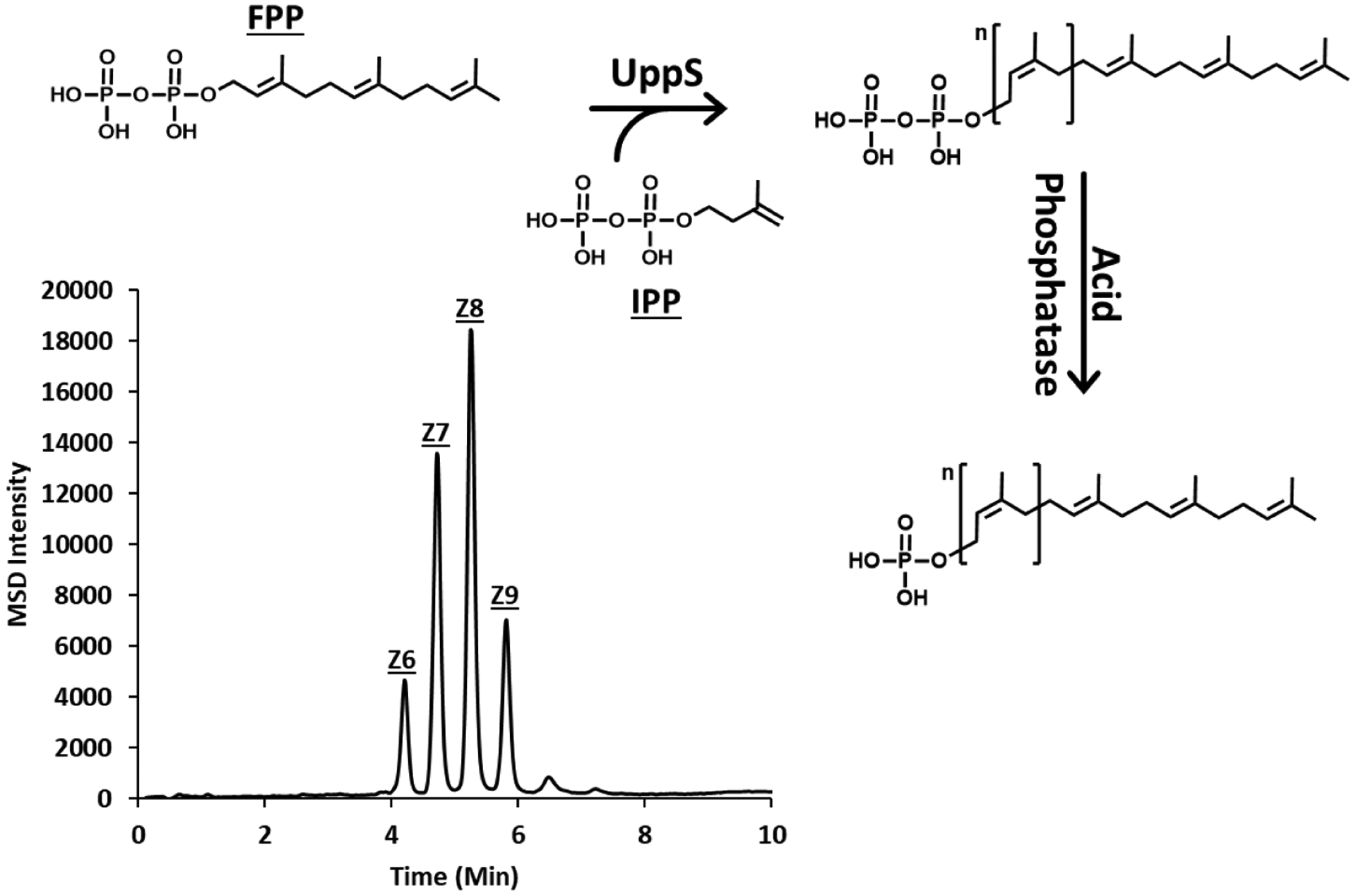

Previous work from our group has demonstrated the in vitro preparation of the colanic acid pentasaccharide on a fluorescent analogue of BP.7 To analyze the cellular production of colanic acid intermediates, we first assembled a set of standards to later compare to cell-derived materials. To do this, we used the same set of proteins described previously to prepare the pentasaccharide on native bactoprenyl phosphate.11 A two-step procedure was used to prepare polyisoprenoid diphosphates with UppS and the native substrate, farnesyl diphosphate. Subsequent extraction and acid phosphatase treatment then generated the corresponding BP. Product formation was monitored in selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode for all Z1–10 isoprenoid monophosphates, where Z represents the number of Z-configuration isoprene units incorporated by UppS (Figure 2). Mass to charge ratios corresponding to the Z6–9 products were observed. Unlike with fluorescent polyisoprenoids, BPs eluted with a retention time approximately 0.5 min earlier than BPPs (SI Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Production of bactoprenyl monophosphates. Elongation of bactoprenyl monophosphate occurs by sequential condensation of eight isopentenyl diphosphates (IPP) to a single farnesyl diphosphate (FPP). Monophosphates were prepared by UppS and subsequent acid phosphatase treatment. LC-MS analysis of acid phosphatase products showed the presence of Zn (n=6–9) BPs, where n is the number of Z configuration isoprene units added by UppS in vitro.

The colanic acid pentasaccharide was then assembled on purified B(Z8)P (native BP) with established methods.7 Colanic acid intermediate formation was monitored in SIM with the indicated mass to charge ratios selected individually for each intermediate, with indicated ion species (Figure 3A). This resulted in a unique SIM chromatogram corresponding to stepwise enzyme product formation for each intermediate numbered 1–10 (Figure 3B). Retention time shifts of −0.1 min occurred after each glycan addition for the mono-, di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharide products. Retention shifts were absent with acetyl modifications of the di- and tetrasaccharide. These results are consistent with previous observations when utilizing fluorescent BP analogues. A notable shift of −1.1 min was seen for the pentasaccharide after the addition of glucuronic acid.7 Inactivity of WcaL prevented us from acquiring the hexasaccharide and subsequent pyruvylated hexasaccharide, which was reported for the fluorescent substrate as well.7

Figure 3.

LCMS of in vitro produced standards of colanic acid intermediates. (A) Structures of colanic acid enzyme products starting with bactoprenyl phosphate. Indicated mass to charge ratios of charged intermediate species were used for selected ion monitoring in the subsequent detection of colanic acid intermediates. (B) One-pot preparation of the colanic acid intermediates with indicated isolated glycosyltransferase enzymes (CPS2E was used as a membrane fraction, all others were purified proteins). Eluted products were observed at 7.1, 6.9, 6.8, 6.8, 6.7, 6.6, 6.6, and 5.7 min for 1–8, respectively. WcaL activity could not be reconstituted in vitro, therefore both the final reactions with WcaL and WcaK showed no new product formation. A membrane fraction containing overexpressed recombinant WcaL was also attempted, but failed to provide product.

Colanic Acid Intermediates do not Readily Accumulate in Single Deletion Mutants

To test whether inactivation of sequential transferase or glycan modifying enzymes could lead to the accumulation of colanic acid intermediates in vivo, single genes associated with colanic acid synthesis were individually deleted in E. coli to produce null mutants used in this work (SI Table S1). Disruptions within the wca operon were engineered to be nonpolar using plasmid pKD3 which, when used as template, generates a scar that has an idealized ribosome binding site and start codon to drive downstream gene expression.24 Cells were grown at 25 °C to promote formation of colanic acid and extracts were prepared for LC-MS as described in the methods and materials.5,25, 26 Each sample was analyzed in selected ion mode for the presence of m/z values corresponding to BP, isoprenoid-linked oligosaccharide intermediates, or the colanic acid repeating unit (Figure 4). BP (solid black chromatogram) was eluted at an identical retention time as in vitro synthesized materials at 7.1 min. The wild-type (WT) parent strain (MG1655) and a complete deletion of the colanic acid operon (ΔCA) acted as controls. Background cell material eluted at 3.3 min and was present in both the WT and ΔCA strains. However, no intermediates were detected utilizing this method, suggesting either they do not accumulate or accumulate below our limit of detection (SI Figure S2).

Figure 4.

Bactoprenyl monophosphate is observed in colanic acid deletion mutants. Bactoprenyl monophosphate (solid black), oligosaccharide intermediates (solid blue), and colanic acid repeat unit (dashed black) expected m/z in selected ion mode. Detectable quantities of bactoprenyl monophosphate, but not lipid-linked oligosaccharides, were observed. Background cellular material eluting at 3.8 min (gray arrow) was not associated with colanic acid production and is likely cellular background with an m/z similar to the colanic acid repeat unit. Mass to charge ratios used for detection were the same as in Figure 3.

It was surprising that intermediate accumulation was absent in these cells despite detectable quantities of BP. The native BP pool was therefore not a limiting factor for intermediate accumulation with these cells. Transcription of the colanic acid operon is induced by the regulators of capsule synthesis (Rcs) signaling pathway.19, 27 Environmental (e.g. low pH or high salt) or cell envelope stressors activate this cascade terminating at the positive regulator of colanic acid synthesis, RcsA.28, 29 Conversely, protease degradation of RcsA limits the production of colanic acid.30 Regulation of Rcs may therefore account for either the lack of intermediate accumulation, or accumulation that lies below our LC-MS detection limit.

Increasing rcsA Expression Promotes Colanic Acid Intermediate Accumulation

We next examined if promoting transcriptional production of the Rcs system could increase the accumulation of colanic acid intermediates. To do this, we incorporated a tetracycline inducible promoter upstream of rcsA which, when induced by tetracycline, prompted cells to produce a thick mucoid layer that was absent from ΔCA cells (SI Figure S3).19, 31 To further promote the possibility of detecting colanic acid intermediates, we supplemented cells with a plasmid encoding IPTG-inducible uppS to bolster native BP levels.22 Cells induced with tetracycline and IPTG were then lysed under identical conditions as the original mutants and were found to accumulate intermediates detectable under identical conditions as in vitro synthesized materials (Figure 5). A total ion scan was performed for each sample and total ion counts generated to demonstrate the presence of all anticipated ion species (SI Figure S4). Each glycan addition produced an analyte with an earlier retention time consistent with in vitro colanic acid intermediates. In addition, cell extracts were analyzed for all other intermediates, which demonstrated the presence of only the anticipated intermediate (SI Figure S5). The WT parent and complete colanic acid deletion (ΔCA) strains were also analyzed in SIM for all intermediate ion species (1–9).

Figure 5.

LC-MS detection of colanic acid intermediate accumulation. Indicated single deletion mutants containing tetracycline- and IPTG-inducible rcsA and uppS, respectively, were lysed and analyzed by SIM in negative mode. Selected mass to charge ratios were identical to in vitro synthesized materials in Figure 3. *Indicates that all intermediate ion species were selected during SIM monitoring except the repeating unit mass Data showing all masses monitored in a single chromatogram are shown in SI Figure S5.

These results demonstrate that rcsA induction is required to detect colanic acid intermediates. Yet, even with induction, intermediates were not observed in the WT strain. Thus, gene inactivation is required to observe the accumulation of lipid-linked colanic acid intermediates. Deletion of wcaM, a gene without a proposed function, did not lead to detectable intermediate formation (SI Figure S5). This was not surprising since loss of WcaM does not affect colanic acid production in E. coli.8, 32 Curiously, mutants accumulating early colanic acid intermediates, corresponding to materials 1–9, produced normally shaped cells (SI Figure S6). This is presumably because sufficient levels of BP were being produced by uppS overexpression to meet the demand for peptidoglycan synthesis.

Under typical conditions, RcsA is readily degraded by the Lon protease, which acts to modulate capsular polysaccharide synthesis, among other numerous housekeeping functions.17, 18 Overexpressing rcsA or deleting lon is a common strategy for inducing colanic acid production (i.e., mucoid) in E. coli.12,33 During our efforts to overproduce colanic acid, we constructed strains with lon deleted, which produced a noticeable mucoid layer (SI Figure S3). However, rcsA overexpression was preferentially chosen to induce colanic acid production since deleting lon is otherwise deleterious.18, 34 Mucoid colonies were not observed when tetracycline was used to induce rcsA in cells that were grown at 37 °C, likely because RcsA is less stable at temperatures above 30 °C.35, 36

Pyruvylated Hexasaccharide Accumulates in Polymerase and Flippase Deficient Mutants but Not Transporter Deficient Mutants

We next sought to accumulate the pyruvylated hexasaccharide repeating unit by removing later enzymes involved in colanic acid biosynthesis, such as the flippase (WzxC), polymerase (WcaD), or exporter (Wza). Mutants lacking these factors were grown and lysed; cell extracts were then analyzed by LC-MS monitoring for the most abundant ion species typically [M-3H]−3, of the repeating unit (Figure 6A). Pyruvylated hexasaccharide was observed in the polymerase mutant (ΔwcaD) with apparent ions from the [M-2H]−2, [M-3H]−3, [M-4H]−4 charged species observed (Figure 6B). Deletion of the colanic acid exporter (wza) did not result in the formation of detectable quantities of intermediates nor the colanic acid repeating unit. We reasoned that the formation of polymerized colanic acid may account for the lack of repeating unit accumulation in exporter deficient cells.

Figure 6.

Full length colanic acid repeating unit is formed in wcaD but not wza deficient cells. (A) SIM chromatograms of the [M-3H]−3 ion species for the Δwza and ΔwcaD mutants. (B) A section of the total ion scan corresponding to the elution of the colanic acid pyruvylated hexasaccharide demonstrating the presence of the [M-2H]−2, [M-3H]−3, [M-4H]−4. (C) The colanic acid repeating unit with anticipated mass to charge ratios. (D) Morphological phenotypes produced by mutants with the indicated genotypes. Background cellular material eluting at 3.8 min (gray arrow) not associated with colanic acid production from both strains. The white bar represents 3 μm.

Whereas disrupting earlier stages in colanic acid assembly had no appreciable effect on cell shape (SI Figure S6), mutants lacking the colanic acid exporter (wza) or polymerase (wcaD) grew as misshapen rods and spheres despite uppS overexpression (Figure 6C). These findings suggests that BP levels are limiting in mutants lacking Wza or WcaD. Though these cells appeared similar, we expected more severe phenotype defects with the polymerase mutant than those of the exporter mutant since the latter should titrate less BP because of polymerization. One possible explanation why ΔwcaD cells did not appear worse was offloading of the repeating unit, but not polymerized intermediate, onto lipopolysaccharide by the WaaL ligase.37 A greater amount of available BP, and thus lower cell rounding, could be expected from liberating colanic acid in this way. Indeed, deleting waaL from cells lacking WcaD resulted in extensive cell lysis when rcsA was induced (Figure 6D). Thus, promiscuous activity by WaaL suppresses defects in the colanic acid polymerase (and probably other BP-related polymerases).

A previously reported flippase (wzxC†) mutant produced a product consistent with the formation of a tetrasaccharide intermediate rather than the pyruvylated hexasaccharide repeating unit (SI Figure S7).20 Surprisingly, lack of pyruvylated hexasaccharide accumulation in ΔwzxC† cells was reproducible and led us to initially consider the possibility of co-regulation. However, the ΔwzxC† null mutant was produced by using plasmid pKD13,20 which does not generate a scar with translation signals.24 Since wcaK and wcaL (which produce the pyruvylated hexasaccharide repeating unit) are located downstream of wzxC, we considered it likely that tetrasaccharide accumulation in ΔwzxC† cells was due to a polar mutation, which may have a further knock-on effect for WcaA activity. With this in mind, primers were redesigned to delete wzxC using pKD3. As expected, the resulting non-polar deletion mutant revealed the anticipated accumulation of the colanic acid repeat unit (Figure 7A and B). These cells demonstrated cell rounding and lysis similar to Δwza and ΔwcaD cells (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Pyruvylated hexasaccharide accumulation in a wzxC deficient mutant. (A) A SIM chromatogram of the [M-3H]−3 ion species. (B) A section of the total ion scan corresponding to the elution of the colanic acid pyruvylated hexasaccharide repeating unit demonstrating the presence of the [M-2H]−2, [M-3H]−3, [M-4H]−4. (C) Morphological phenotypes produced by ΔwzxC cells with pUppS and rcsA induction. Background cellular material eluting at 3.8 min (gray arrow) not associated with colanic acid production. The white bar represents 3 μm.

In vitro Evidence for WcaK Activity, but not WcaL

Lack of recombinant WcaL activity prevented our group from tracking the in vitro formation of the hexasaccharide. Subsequently, it was also not possible to evaluate WcaK activity without WcaL product in hand. Some radiolabeling assays have successfully used endogenous BP as the lipid donor source for in vitro reactions.33, 38, 39 We therefore wondered if supplying the crude cell extract from intermediate accumulating mutants could provide the needed substrate instead. Both WcaL and WcaK were expressed and purified as previously described, and then incubated with crude cell extracts containing accumulated penta- or hexasaccharide, respectively.7 In agreement with our previous observations, WcaL failed to catalyze the formation of the hexasaccharide when supplied ΔwcaL extract and UDP-galactose (Figure 8A). However, WcaK produced the pyruvyl modification when given ΔwcaK lipid extract and phosphoenolpyruvate (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

In vitro functional assays of WcaL and WcaK with intermediate extracts. (A) Isolated WcaL did not catalyze the formation of the hexasaccharide with extracted pentasaccharide from ΔwcaL cells. (B) Conversion of the hexasaccharide to a m/z consistent with a pyruvylated product occurs in the presence of WcaK and extracted hexasaccharide from ΔwcaK cells. Background cellular material eluting at 3.8 min (gray arrow) not associated with colanic acid production.

The absence of WcaL activity after the addition of endogenous material demonstrates that even the native acceptor substrate was insufficient for turnover. Analysis on the chemical composition of colanic acid strongly suggests that galactose is present in the pentasaccharide.40, 41,6, 42 Indeed, our analysis of the ΔwcaK mutant confirms the mass associated with a hexose in the hexasaccharide. Instead, we ascribe the lack of WcaL activity to problems associated with the recombinant protein expression, resulting in loss of downstream activity. The rate of transcription/translation, lysis conditions, and buffer composition can all contribute to failed enzyme activity.13 WcaL is not predicted to contain transmembrane domains, however we observed consistent localization in the membrane fraction of our protein preparations (see SI material in Scott, PM et al).7 This aberrant solubility may further indicate protein aggregation. However, it cannot yet be ruled out that a different sugar than galactose is incorporated by WcaL and the stereochemistry is then altered by the activity of WcaK to give galactose. Attempts to utilize UDP-Glucose as an alternative substrate for WcaL also failed though.

Partitioning of Colanic Acid Intermediates

Two-phase Bligh and Dyer mixtures are commonly employed to extract polyprenyl linked glycans into the organic phase. However, it is not clear how many sugars can be added before the glycan no longer separates into the organic phase. We wondered if certain glycan lengths might be sufficient to solubilize BPP-oligosaccharides into the non-buffered aqueous or organic phase. A two-phase Bligh and Dyer system was used to assess this, followed by a secondary extraction with n-butanol of the aqueous layer (SI Figure S8). All intermediates including BP up until the pentasaccharide were chloroform miscible. Penta-, hexa- and pyruvylated hexasaccharide were aqueous-miscible with marginal solubility in n-butanol at neutral pH. Surprisingly, just five glycan moieties can overcome the hydrophobicity of the polyisoprenoid chain. It should be noted that the pentasaccharide contains a negatively charge glucuronic acid moiety at neutral pH unlike earlier oligosaccharide intermediates. The increasing polarity and introduction of a charged species may contribute to this unexpected shift in hydrophobicity of later intermediates.

Conclusion

A method for tracking the in vivo formation of colanic acid biosynthesis with single deletion mutants is herein reported. Accumulation of detectable quantities of intermediates ultimately required upregulation of Rcs translation of the colanic acid operon. It has been proposed that this stress response is one possible mechanism by which BP utilization is modulated.43 Presumably essential cell well features, such as peptidoglycan, are prioritized first given the limited BP pool. However, whether peptidoglycan synthesis is prioritized over other surface glycans is not known. It is interesting to consider if the accumulation of colanic acid intermediates in this case might further incite this response due to changes in membrane composition. This could explain why mutants without RcsA induction did not produce detectable quantities of oligosaccharides despite the presence of BP. Reconstituting colanic acid synthesis by accumulating stepwise intermediates provided a full map of the functional roles associated with producing this exopolysaccharide. Our efforts highlight the need to establish alternative methods for evaluating bacterial surface glycans as they occur in nature.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank Dr. Kevin Young and Dr. Dev Ranjit for supplying some of the strains used in this work.

Funding Sources

Funding supporting this work was received through grants from the National Institutes of Health General Medical Sciences grant numbers: R01GM123251 and F31GM130065. MAJ is supported by R01GM061019.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BPP

Bactoprenyl diphosphate

- BP

Bactoprenyl phosphate

- Rcs

Regulation of capsule synthesis

- SIM

Selected ion monitoring

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Total ion counts and a complete screen of all intermediates are presented in the SI. Primers and strains used in this work can also be found in the SI, as well as detailed procedures for producing these strains. All SI Figures and Tables are available in the supporting information available free of charge.

REFERENCES

- [1].Whitfield C, and Paiment A (2003) Biosynthesis and assembly of Group 1 capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli and related extracellular polysaccharides in other bacteria, Carbohyd Res 338, 2491–2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chen J, Lee SM, and Mao Y (2004) Protective effect of exopolysaccharide colanic acid of Escherichia coli O157:H7 to osmotic and oxidative stress, Int J Food Microbiol 93, 281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mao Y, Doyle MP, and Chen J (2001) Insertion mutagenesis of wca reduces acid and heat tolerance of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7, J Bacteriol 183, 3811–3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ophir T, and Gutnick DL (1994) A role for exopolysaccharides in the protection of microorganisms from desiccation, Appl Environ Microbiol 60, 740–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Prigent-Combaret C, Prensier G, Le Thi TT, Vidal O, Lejeune P, and Dorel C (2000) Developmental pathway for biofilm formation in curli-producing Escherichia coli strains: role of flagella, curli and colanic acid, Environ Microbiol 2, 450–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Goebel WF (1963) Colanic acid, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 49, 464–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Scott PM, Erickson KM, and Troutman JM (2019) Identification of the Functional Roles of Six Key Proteins in the Biosynthesis of Enterobacteriaceae Colanic Acid, Biochemistry 58, 1818–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stevenson G, Andrianopoulos K, Hobbs M, and Reeves PR (1996) Organization of the Escherichia coli K-12 gene cluster responsible for production of the extracellular polysaccharide colanic acid, J Bacteriol 178, 4885–4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Harding CM, Haurat MF, Vinogradov E, and Feldman MF (2018) Distinct amino acid residues confer one of three UDP-sugar substrate specificities in Acinetobacter baumannii PglC phosphoglycosyltransferases, Glycobiology 28, 522–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Das D, Kuzmic P, and Imperiali B (2017) Analysis of a dual domain phosphoglycosyl transferase reveals a ping-pong mechanism with a covalent enzyme intermediate, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 7019–7024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Reid AJ, Scarbrough BA, Williams TC, Gates CE, Eade CR, and Troutman JM (2020) General Utilization of Fluorescent Polyisoprenoids with Sugar Selective Phosphoglycosyltransferases, Biochemistry 59, 615–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Patel KB, Toh E, Fernandez XB, Hanuszkiewicz A, Hardy GG, Brun YV, Bernards MA, and Valvano MA (2012) Functional characterization of UDP-glucose:undecaprenyl-phosphate glucose-1-phosphate transferases of Escherichia coli and Caulobacter crescentus, J Bacteriol 194, 2646–2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rosano GL, and Ceccarelli EA (2014) Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli: advances and challenges, Front Microbiol 5, 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schaffer C, Wugeditsch T, Messner P, and Whitfield C (2002) Functional expression of enterobacterial O-polysaccharide biosynthesis enzymes in Bacillus subtilis, Appl Environ Microbiol 68, 4722–4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].van Heijenoort J (2007) Lipid intermediates in the biosynthesis of bacterial peptidoglycan, Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71, 620–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Piepenbreier H, Diehl A, and Fritz G (2019) Minimal exposure of lipid II cycle intermediates triggers cell wall antibiotic resistance, Nat Commun 10, 2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Luo S, McNeill M, Myers TG, Hohman RJ, and Levine RL (2008) Lon protease promotes survival of Escherichia coli during anaerobic glucose starvation, Arch Microbiol 189, 181–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Van Melderen L, and Aertsen A (2009) Regulation and quality control by Lon-dependent proteolysis, Res Microbiol 160, 645–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gottesman S, Trisler P, and Torres-Cabassa A (1985) Regulation of capsular polysaccharide synthesis in Escherichia coli K-12: characterization of three regulatory genes, J Bacteriol 162, 1111–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ranjit DK, and Young KD (2016) Colanic Acid Intermediates Prevent De Novo Shape Recovery of Escherichia coli Spheroplasts, Calling into Question Biological Roles Previously Attributed to Colanic Acid, Journal of Bacteriology 198, 1230–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jorgenson MA, Kannan S, Laubacher ME, and Young KD (2016) Dead-end intermediates in the enterobacterial common antigen pathway induce morphological defects in Escherichia coli by competing for undecaprenyl phosphate, Mol Microbiol 100, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Eade CR, Wallen TW, Gates CE, Oliverio CL, Scarbrough BA, Reid AJ, Jorgenson MA, Young KD, and Troutman JM (2021) Making the Enterobacterial Common Antigen Glycan and Measuring Its Substrate Sequestration, ACS Chem Biol 16, 691–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Studier FW (2005) Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures, Protein Expr Purif 41, 207–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Datsenko KA, and Wanner BL (2000) One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 6640–6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Whitfield C, and Roberts IS (1999) Structure, assembly and regulation of expression of capsules in Escherichia coli, Mol Microbiol 31, 1307–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Henderson JC, O’Brien JP, Brodbelt JS, and Trent MS (2013) Isolation and chemical characterization of lipid A from gram-negative bacteria, J Vis Exp, e50623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Stout V (1996) Identification of the promoter region for the colanic acid polysaccharide biosynthetic genes in Escherichia coli K-12, J Bacteriol 178, 4273–4280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wall E, Majdalani N, and Gottesman S (2018) The Complex Rcs Regulatory Cascade, Annu Rev Microbiol 72, 111–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Castanie-Cornet MP, Cam K, and Jacq A (2006) RcsF is an outer membrane lipoprotein involved in the RcsCDB phosphorelay signaling pathway in Escherichia coli, Journal of Bacteriology 188, 4264–4270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ebel W, and Trempy JE (1999) Escherichia coli RcsA, a positive activator of colanic acid capsular polysaccharide synthesis, functions To activate its own expression, J Bacteriol 181, 577–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gossen M, and Bujard H (1992) Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89, 5547–5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Adcox HE, Vasicek EM, Dwivedi V, Hoang KV, Turner J, and Gunn JS (2016) Salmonella Extracellular Matrix Components Influence Biofilm Formation and Gallbladder Colonization, Infect Immun 84, 3243–3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Amer AO, and Valvano MA (2002) Conserved aspartic acids are essential for the enzymic activity of the WecA protein initiating the biosynthesis of O-specific lipopolysaccharide and enterobacterial common antigen in Escherichia coli, Microbiology (Reading) 148, 571–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Charette MF, Henderson GW, and Markovitz A (1981) ATP hydrolysis-dependent protease activity of the lon (capR) protein of Escherichia coli K-12, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 78, 4728–4732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Navasa N, Rodriguez-Aparicio L, Martinez-Blanco H, Arcos M, and Ferrero MA (2009) Temperature has reciprocal effects on colanic acid and polysialic acid biosynthesis in E-coli K92, Appl Microbiol Biot 82, 721–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Clarke DJ (2010) The Rcs phosphorelay: more than just a two-component pathway, Future Microbiol 5, 1173–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Meredith TC, Mamat U, Kaczynski Z, Lindner B, Holst O, and Woodard RW (2007) Modification of lipopolysaccharide with colanic acid (M-antigen) repeats in Escherichia coli, J Biol Chem 282, 7790–7798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kramer NE, Smid EJ, Kok J, de Kruijff B, Kuipers OP, and Breukink E (2004) Resistance of Gram-positive bacteria to nisin is not determined by lipid II levels, FEMS Microbiol Lett 239, 157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Dietrich CP, Colucci AV, and Strominger JL (1967) Biosynthesis of the peptidoglycan of bacterial cell walls. V. Separation of protein and lipid components of the particulate enzyme from Micrococcus lysodeikticus and purification of the endogenous lipid acceptors, J Biol Chem 242, 3218–3225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Grant WD, Sutherland IW, and Wilkinson JF (1969) Exopolysaccharide colanic acid and its occurrence in the Enterobacteriaceae, J Bacteriol 100, 1187–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Johnson JG, and Wilson DB (1977) Role of a sugar-lipid intermediate in colanic acid synthesis by Escherichia coli, J Bacteriol 129, 225–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sutherland IW (1971) Enzymic hydrolysis of colanic acid, Eur J Biochem 23, 582–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Huang YH, Ferrieres L, and Clarke DJ (2006) The role of the Rcs phosphorelay in Enterobacteriaceae, Res Microbiol 157, 206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.