Abstract

Background:

Individualized hemodynamic management during surgery relies on accurate titration of vasopressors and fluids. In this context, computer systems have been developed to assist anesthesia providers in delivering these interventions. We tested the hypothesis that computer-assisted individualized hemodynamic management could reduce intraoperative hypotension in patients undergoing intermediate to high-risk surgery.

Methods:

This single-center, parallel, two-arm, prospective randomized controlled single blinded superiority study included 38 patients undergoing abdominal or orthopedic surgery. All included patients had a radial arterial catheter inserted after anesthesia induction and connected to an uncalibrated pulse contour monitoring device. In the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group (N=19), the individualized hemodynamic management consisted of manual titration of norepinephrine infusion to maintain mean arterial pressure (MAP) within 10% of the patient’s baseline value, and mini-fluid challenges to maximize stroke volume index (SVI). In the computer-assisted group (N=19), the same approach was applied using a closed-loop system for norepinephrine adjustments and a decision-support system for the infusion of mini-fluid challenges (100ml). The primary outcome was intraoperative hypotension defined as the percentage of intraoperative case time patients spent with a MAP < 90% of the patient’s baseline value, measured during the preoperative screening. Secondary outcome was the incidence of minor postoperative complications.

Results:

All patients were included in the analysis. Intraoperative hypotension was 1.2% [0.4-2.0%] in the computer-assisted group compared to 21.5% [14.5-31.8%] in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group (difference −21.1 (95% CI −15.9 to −27.6%); p<0.001). The incidence of minor postoperative complications was not different between groups (42 versus 58%, p=0.330). Mean SVI and cardiac index were both significantly higher in the computer-assisted group than in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group (p<0.001).

Conclusion:

In patients having intermediate to high-risk surgery, computer-assisted individualized hemodynamic management significantly reduces intraoperative hypotension compared to a manually controlled goal directed approach.

Keywords: Fluid resuscitation, cardiac output, personalized medicine, hemodynamic monitoring, mean arterial pressure, abdominal surgery, blood pressure

INTRODUCTION

Intraoperative hypotension occurs frequently and negatively affects postoperative outcomes.1, 2 Using large database analyses, several research groups have reported a significant relationship between intraoperative hypotension during non-cardiac surgery and postoperative complications.3–10 The incidence of these complications appears to be related to the magnitude and the duration of the hypotension. Specifically, only one minute with a mean arterial pressure (MAP) less than 55-65 mmHg intraoperatively has been associated with a higher risk of morbidity.3 In a multicenter, randomized controlled trial, Futier et al demonstrated that maintaining an “individualized” arterial pressure during surgery (within 10% of the patient’s baseline reference value) reduced postoperative organ dysfunction compared to standard management.11 This was achieved using a continuous norepinephrine infusion started at anesthesia induction and continued until the end of surgery. Following this study, this approach is being used by several teams around the world to minimize intraoperative hypotension during high-risk surgery. However, the use of vasoconstrictors to maintain an individualized arterial pressure may mask the development of hypovolemia, exposing patients to risks associated with reduced end organ blood flow.

Optimizing flow and pressure requires repeated measurement of both variables and use of established protocols for vasopressor and fluid administration. This strategy, called “individualized hemodynamic management”, has been shown to be associated with decreased postoperative complications compared to routine care.12 However, efficient and accurate control of MAP and CO is a challenge during major surgery, as it requires frequent manual adjustments of vasopressor infusion rates and timely fluid administration, thus necessitating continuous attention of the care provider, which can prove difficult to achieve.

We have developed closed-loop systems for automated vasopressor and fluid administration.13–17 When used separately, these systems have been shown to be more effective at maintaining hemodynamic targets (MAP and stroke volume index (SVI)) than manual management for patients undergoing major surgery.13, 18 Unfortunately, a “single” closed-loop system allowing the simultaneous co-administration of vasopressors and fluid is not currently available for widespread clinical use, although we are actively working on its development. An important step in this process is the combination of a closed-loop system for vasopressor administration and a decision-support system for bolus fluid administration.

The hypothesis for this prospective randomized controlled study was therefore to demonstrate that patients managed using a computer-assisted system would experience less intraoperative hypotension (defined as a MAP < 90% of the patient’s baseline value) during intermediate to high-risk surgery when compared to patients in whom vasopressor and fluid administration were controlled manually.

Materials and Methods

This single-center, prospective, two-arm, parallel, randomized controlled, superiority study was approved by the institutional review board of Bordeaux (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Ouest et Outre Mer III, Bordeaux, France N°DC2015/117) and the study protocol was published on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03965793) on May 29, 2019 before patient enrollment began (Principal Investigator: Alexandre Joosten). Importantly, since 2018, clinical research protocols are not reviewed by the local institutional review board but rather are randomly directed to a different institution’s review board in France to reduce bias in reviews. The study was conducted at Bicetre Hospital from October 28, 2019, through June 26, 2020. All patients were approached by the principal investigator and after presentation of the study purposes, written informed consent were obtained before inclusion.

Inclusion & non-inclusion criteria

Adult patients scheduled for an elective intermediate to high-risk abdominal or orthopedic surgical procedure 19 who were expected to be managed according to an individualized hemodynamic protocol using a radial catheter coupled to an advanced hemodynamic monitoring device (EV1000, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, USA) as part of their anesthetic care were eligible for this protocol. Non-inclusion criteria were minor patients (< 18 years), pregnancy, cardiac arrhythmias and refusal to participate. The trial was conducted in accordance to the original protocol and as a result, no change has been made in the protocol after trial commencement.

Randomization and blinding

Randomization assignments were generated without restriction and was generated on October 24, 2019 by our research nurse using an internet-based software (http://www.randomization.com), to either closed-loop vasopressor and decision-support-guided fluid therapy (computer-assisted group) or manually adjusted goal directed therapy group. Opaque envelopes in recruitment sequence were then created by an unaffiliated research nurse. The morning of the surgery, a sealed opaque envelope containing the assigned patient number was opened. The envelopes were kept in the research office of Bicetre hospital. Patients were blinded to group allocation, but anesthesia providers were not. However, outcome data were collected by collaborators blinded to both the study group allocation and the reasoning for the research protocol. Importantly, as stipulated by the institutional review board, the principal investigator could not be the primary anesthesiologist but should be present in order to supervise the computer-assisted systems. Patients in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group were managed by an anesthesiologist not involved in the current study who applied the individualized hemodynamic protocol (manually) that is routine in our institution for these surgical procedures (Appendix 1).

Anesthesia Procedure

Pre-operatively, all patients stopped taking angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor drugs and/or angiotensin receptor blocker drugs 48 hours prior to surgery per institutional standard of care.

Standard monitoring was applied to all patients and included a three-lead electrocardiogram, non-invasive pulse oximetry, standard arm arterial pressure cuff, capnography, central temperature assessment (esophageal probe) and a depth of anesthesia monitor (BIS™, Medtronic, Bièvres, France). A radial artery catheter was also inserted during induction and linked via the Flotrac™ sensor to a pulse contour analysis hemodynamic monitor (EV1000 ™, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA). Anesthesia was induced with sufentanil (2 μg/kg) and propofol (2 mg/kg). Atracurium (0.6 mg/kg) was administered for intubation and 10 mg boluses were added as needed to maintain the train-of-four ratio < 2 (TOF Scan technology, Idmed, France). Anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane to keep a BIS value between 40-60. Sufentanil boluses (0.1 to 0.2 μg/kg) could be administered, at the discretion of the primary anesthesia provider. All patients received mechanical ventilation using a volume control mode with tidal volumes of 7-8 ml/kg of predicted body weight and a respiratory rate adjusted to achieve an end tidal CO2 between 34 and 38 cmH2O. Recruitment maneuvers were done at the discretion of the anesthesiologist in charge of the patient. Prophylactic antibiotics and antiemetics were administered 30 minutes before surgical incision.

It is common practice in our hospital that fluid management for intermediate to high-risk abdominal and orthopedic surgical patients be standardized This is achieved with a baseline maintenance infusion of Ringer’s lactate solution (Fresenius Kabi, Sevres, France) set at a rate of 2 to 4 ml/kg/h (laparoscopic vs open) and additional fluid boluses based on an advanced uncalibrated hemodynamic device (EV1000, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA). This monitor provides flow-based variables (SVI and cardiac index (CI)), and stroke volume variation (SVV), a dynamic predictor of fluid responsiveness. To avoid intraoperative hypothermia, a forced-air warming system (Bair Hugger®, SEBAC, Flaxlanden, France) and a blood-fluid warming system (Fluido® Compact, SEBAC, Flaxlanden, France) were utilized during the surgical procedure. Packed red blood cells were infused to maintain the hemoglobin concentration between 7 and 9 g/dl, depending on each patient’s status and comorbidities.

For postoperative pain management, all patients who had a laparotomy had a thoracic epidural catheter inserted by the anesthesiologist before induction. The epidural was activated after a test dose (4-ml lidocaine 2% with 1:200,000 epinephrine) and was infused with ropivacaine 2mg/ml in a bag of 200 ml of normal saline into which morphine 10 mg was added. The mixture was infused at a rate of 5-6 ml/h from skin incision until postoperative day 3.

Individualized fluid and vasopressor administration protocol

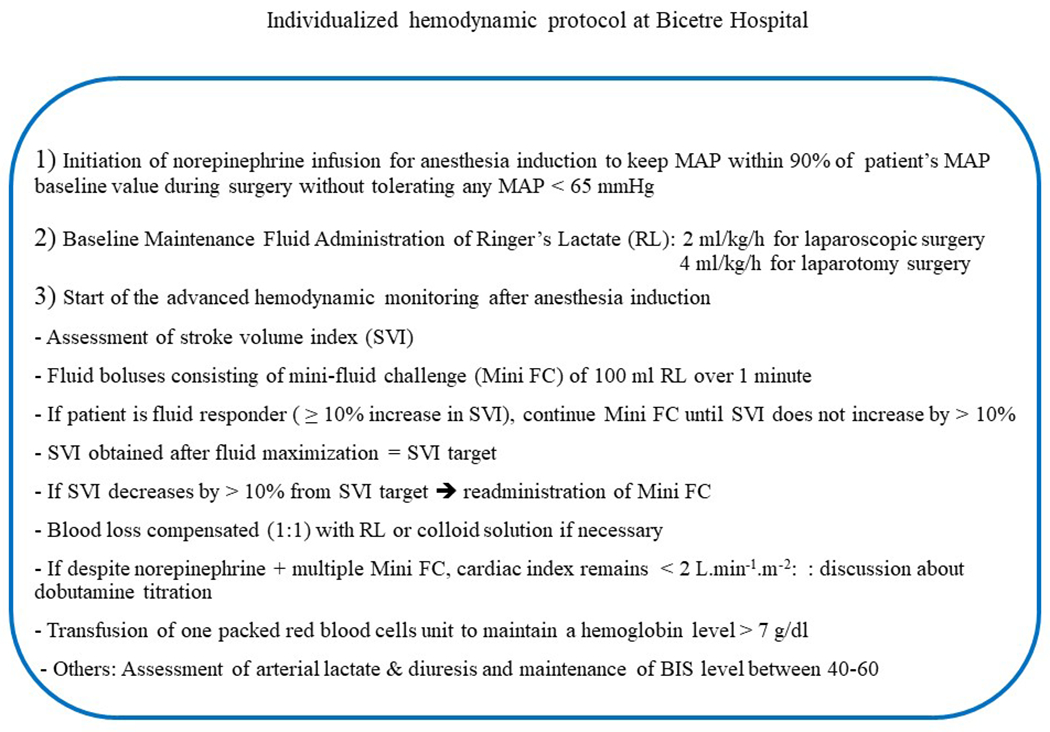

In the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group, vasopressor and fluid administration was adjusted manually by anesthesia providers and/or nurse anesthetists using our institutional individualized hemodynamic protocol. This protocol consists of two main components: 1) individualized MAP control starting at anesthesia induction and continued until the end of the surgery and 2) SVI maximization using mini-fluid challenges of 100-ml fluid boluses. Details regarding this individualized hemodynamic protocol are shown in Appendix 1.

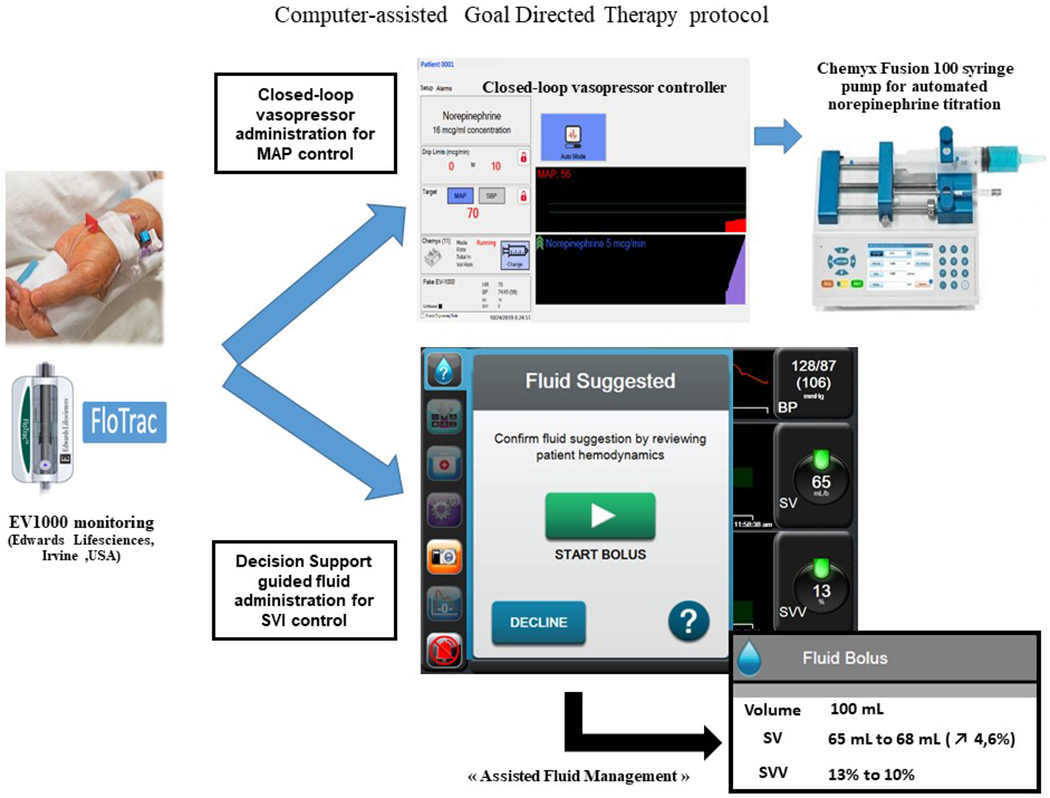

In the computer-assisted group, the same strategy was applied but using a computer-assisted system including:

A closed-loop vasopressor system was used to titrate vasopressor administration. Details on this system are described in our previous publications 16, 17, 20–23 and in the online Supplemental Digital Content 1. As review, MAP values from an EV1000 monitor are collected by the closed-loop vasopressor and the proportional, integral, and derivative errors (if any) converted into a dose titration of a norepinephrine infusion. The closed-loop vasopressor controller itself is a hybrid proportional integral derivative (PID) and rules-based system. The algorithm was coded in Microsoft Visual C (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA), and software version 2.93 of the closed-loop system was used exclusively for patients enrolled in the computer-assisted group. The system was run on an ACER laptop using Windows 7 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, CA). It collected MAP data from the EV1000 monitor via a serial RS232 connection and controlled a Chemyx Fusion 100 syringe pump (Chemyx Inc, Stafford, TX, United States) via USB. Importantly, a second norepinephrine syringe not associated with the system was also available to the primary team if the system experienced errors or for emergency use. Per protocol, the primary team was only to give “rescue” boluses of vasopressors in the event the system performance was inadequate.

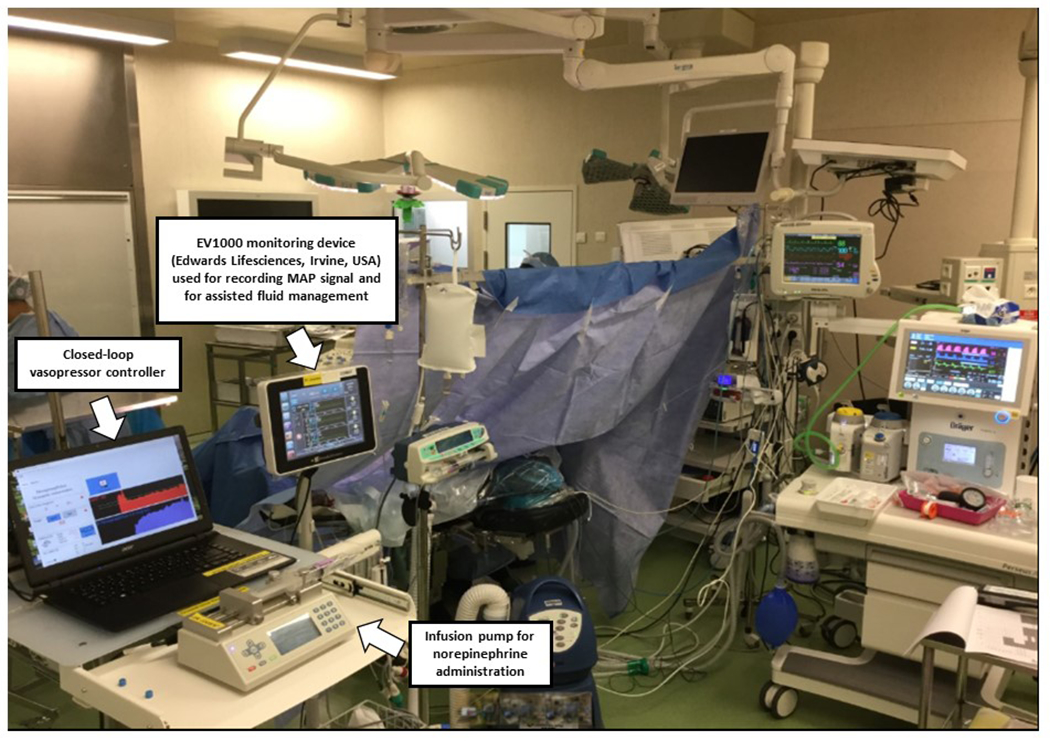

A real time clinical decision support system called “assisted fluid management” (AFM™, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) was used to guide mini-fluid challenges. Briefly, this system suggests to the anesthesia provider that a fluid bolus should be administered, analyses the effects of the bolus, and continually re-assesses the patient for further fluid requirements.24 The AFM algorithm core is the same as the closed-loop algorithm we used in previous publications; 100% compliance with the AFM prompts would result in identical treatment that achieved by closed-loop control, although with minimal time delays for acceptance of recommendations. Figure 1 presents the schematic for the computer-assisted group. In both groups, the norepinephrine infusion was administered through an intravenous line not used for any other purpose. Appendix 2 shows the computer-assisted set-up in the operating room at Bicetre hospital. Importantly, in both groups, no other vasopressor than norepinephrine was allowed.

Figure 1:

Schematic representation of our computer-assisted individualized hemodynamic management protocol.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was intraoperative hypotension defined as the percentage of intraoperative case time patients spent with a MAP < 90% of the patient’s baseline value, measured during the preoperative screening. This cutoff has been chosen based on the implementation of our individualized hemodynamic protocol already in place in our institution a few months before the beginning of the current study. The primary outcome was calculated on a per-patient basis as:

It was assumed that with the modest sample size, we would be unlikely to see differences in major complications, so our secondary outcome measure was the incidence of minor postoperative complications measured at postoperative day 30 (including postoperative nausea and vomiting, delirium, wound infection, urinary infection, pneumonia, acute kidney injury, paralytic ileus, other infections and readmission to hospital within 30 days post-surgery). These complications have been defined in our previous publications. 25, 26

Other hypothesis generating outcome measures included major complications (at postoperative day 30), percentage of case time with a MAP < 65 mmHg, percentage of case time “in target” (MAP ± 10 mmHg of the baseline MAP), percentage of case time above target (MAP > 10 mmHg), mean SVV, CI, SVV, SVI during the first and last 30 minutes of the case, and the percentages of case time with a SVV < 13%, with a CI < 2 l.min−1.m−2, and with a SVI < 30 ml.m−2. We also recorded total intraoperative volumes of fluids administered, net fluid balance, total doses of norepinephrine given, the number of norepinephrine rate modifications during surgery, lactate values measured before skin incision and at arrival in the post-anesthesia care unit, and lengths of stay in the post-anesthesia care unit, intensive care unit, and the hospital. No change in the outcomes has been made after trial commencement.

Data Collection

All hemodynamic variables were collected at 20-second intervals via the EV1000 monitor. The study started once the radial artery catheter had been inserted and connected to the EV1000 monitor, approximately 5 minutes after anesthesia induction.

Study power

Power calculation was performed based on the primary objective. Our data showed that patients spent 12±8% of intraoperative case time with a MAP < 90% of their preoperative value when norepinephrine was titrated manually.27 To detect a 50% reduction in the time spent in hypotension in the computer-assisted group, the study needed 19 patients per group (38 patients total) to achieve 80% power with Welch’s unequal variances t-test and bilateral alpha risk fixed at 5%. No drop out was taken into account.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using an intention-to-treat approach and in a blinded fashion. Normality of data was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Variables normally distributed were compared with independent samples t-test and are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Non-normally distributed variables were compared with a Mann-Whitney U-test and were expressed as median [25%-75%] percentiles. Discrete data are expressed as a number and percentage and were compared using a Chi square or a Fisher’s exact test when indicated.

The primary outcome was evaluated using a Mann-Whitney U-test; difference between groups with 95% confidence interval was also calculated. The secondary outcome were evaluated using Chi-squared. The analyses were not adjusted for additional variables. No interim analysis was planned on the data. Statistical significance was set at a p-value <0.05 and all tests were two-tailed. Analysis were performed using Minitab (Paris, France).

Results

Patient’s population

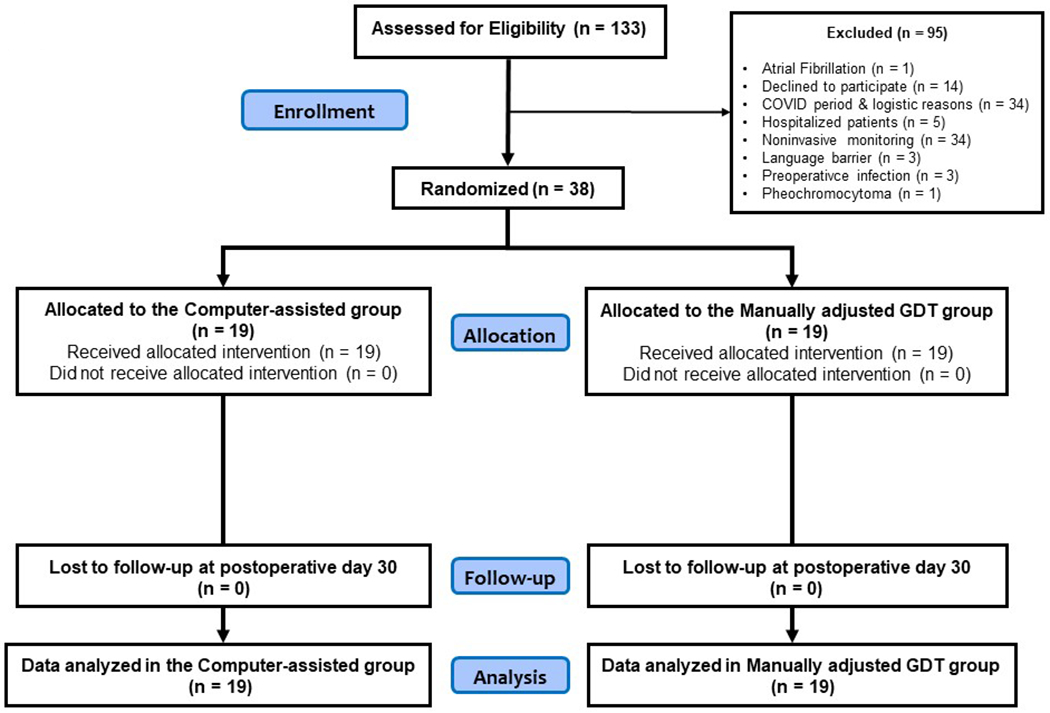

Between October 28, 2019 and June 26, 2020, 133 patients were screened for eligibility and 38 patients were enrolled and randomized. As a result, the trial was not stopped prior to obtaining the sample size goal. Reasons for non-inclusion are shown in Figure 2. All patients were included in this intention to treat analysis.

Figure 2:

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram of patient flow.

Preoperative and intraoperative data

Patients in both groups had similar baseline MAP. Importantly, there were no differences between groups in the numbers of patients undergoing a laparoscopic surgery or having a thoracic epidural analgesia (Table 1).

Table 1:

Patient’s baseline characteristics

| Variable | Control (N=19) | Computer-assisted (N=19) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 63 ± 15 | 64 ± 13 |

| Male, N (%) | 12 (63) | 15 (79) |

| Weight (kg) | 70 ± 15 | 79 ± 18 |

| Height (cm) | 169 ± 12 | 171 ± 9 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24 ± 5 | 27 ± 5 |

| Patients with ASA status II / III, ; N (%) | 14 (74) / 5 (26) | 9 (47) / 10 (53) |

| Preoperative hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.1 ± 1.8 | 13.1 ± 1.7 |

| Preoperative creatinine (mmol/l) | 73.3 ± 18.9 | 84.1 ± 28.6 |

| Preoperative MAP (mmHg) | 90 [85-90] | 90 [85-90] |

| Minimum MAP target for surgery (mmHg) * | 81 [76-81] | 81 [76-81] |

| Medications, N (%) | ||

| Aspirin | 0 (0) | 6 (32) |

| ß-blocker | 3 (16) | 5 (26) |

| Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor | 3 (16) | 4 (21) |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 0 (0) | 2 (11) |

| Statin | 1 (5) | 2 (11) |

| Calcium blocker | 3 (16) | 4 (21) |

| Hypoglycemic agent | 1 (5) | 6 (32) |

| Comorbidities, N (%) | ||

| Myocardial injury | 0 (0) | 2 (11) |

| Hypertension | 6 (32) | 11 (58) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1 (5) | 3 (16) |

| Diabetes | 1 (5) | 7 (37) |

| Type of surgery, N (%) | ||

| High-risk abdominal surgery | 11 (58) | 11 (58) |

| Moderate-risk abdominal surgery | 6 (32) | 5 (26) |

| High-risk orthopedic surgery | 2 (11) | 3 (16) |

| Patients having a laparoscopic surgery, N (%) | 6 (31) | 4 (21) |

| Patients having a Thoracic epidural analgesia, N (%) | 13 (68) | 13 (68) |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median and [25 -75] percentiles or number and (%). N: number; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists

Minimum MAP target = minimal MAP to be maintained by anesthesiologists in charge of the patient, defined as preoperative MAP – 10%

There were no significant differences between groups in anesthesia duration, baseline fluid infusion, or the total volume of fluid boluses received (Table 2). However, estimated blood loss and urine output were significantly higher in the computer-assisted group than in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group. Consequently, the net fluid balance at the end of the surgery was significantly lower in the computer-assisted group than in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group (Table 2). The total dose of norepinephrine was more than 40% lower in the computer-assisted group than in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group. The computerized closed-loop vasopressor system made more than 1000 modifications of the infusion rate per case compared to a median of 15 in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group (Table 2).

Table 2:

Intraoperative data

| Variables | Manually adjusted GDT group (N=19) | Computer-assisted GDT group (N=19) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anesthesia duration (min) | 340 [260-480] | 330 [280-435] | 0.493 |

| Surgery duration (min) | 265 [190-370] | 240 [210-359] | 0.651 |

| Baseline maintenance crystalloid (ml) | 1487 ± 751 | 1608 ± 723 | 0.616 |

| Total volume of fluid bolus (crystalloid and colloid) (ml) £ | 1937 ± 1024 | 1753 ± 857 | 0.551 |

| Packed red blood cells (ml) | 721 ± 315 | 331 ± 129 | 0.070 |

| Patients transfused (%) | 3 (16) | 4 (21) | 0.676 |

| Total IN (ml) | 2600 [2250-5000] | 3300 [2800-4200] | 0.770 |

| Estimated blood loss (ml) | 400 [200-550] | 1000 [400-1500] | 0.022 |

| Urine output (ml) | 400 [300-500] | 950 [600-1200] | 0.002 |

| Gastric suction (ml) | 100 [50-100] | 150 [100-250] | 0.049 |

| Total OUT (ml) | 800 [600-1150] | 1900[1150-3002] | 0.002 |

| Fluid balance (ml) | 2050 [1650-4060] | 1400 [700-2100] | 0.034 |

| Mean BIS values | 49.4 ± 3.2 | 49.6 ± 3.1 | 0.838 |

| Total dose of norepinephrine (mcg) | 1340 [710-2240] | 765 [535-1426] | 0.068 |

| Mean rate of norepinephrine (mcg.min−1) | 5.8 [2.7-9.1] | 2.7 [2.0-6.7] | 0.133 |

| Norepinephrine rate modifications (N) | 15 [12-20] | 1271 [999-1432] | <0.001 |

| Percentage of case time when norepinephrine infusion was running | 95 [95-95] | 96 [91-99] | 0.438 |

| Lactate before skin incision (mEq/l) | 1.3 [0.8-1.9] | 1.0 [0.9-1.5] | 0.401 |

| Lactate at PACU arrival (mEq/l) | 2.7 [1.6-3.2] | 1.2 [0.9-2.3] | 0.011 |

Total IN is the sum of crystalloid, colloid and blood product administration while total OUT is the sum of estimated blood loss, urine output and gastric suction. Fluid balance is the difference between total IN – total OUT. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median and [25th -75th] percentiles or number (%). GDT: goal directed therapy; PACU: post-anesthesia care unit.

: only one patient received a colloid solution in the control group. Bold indicates statistically significant P values

Outcomes

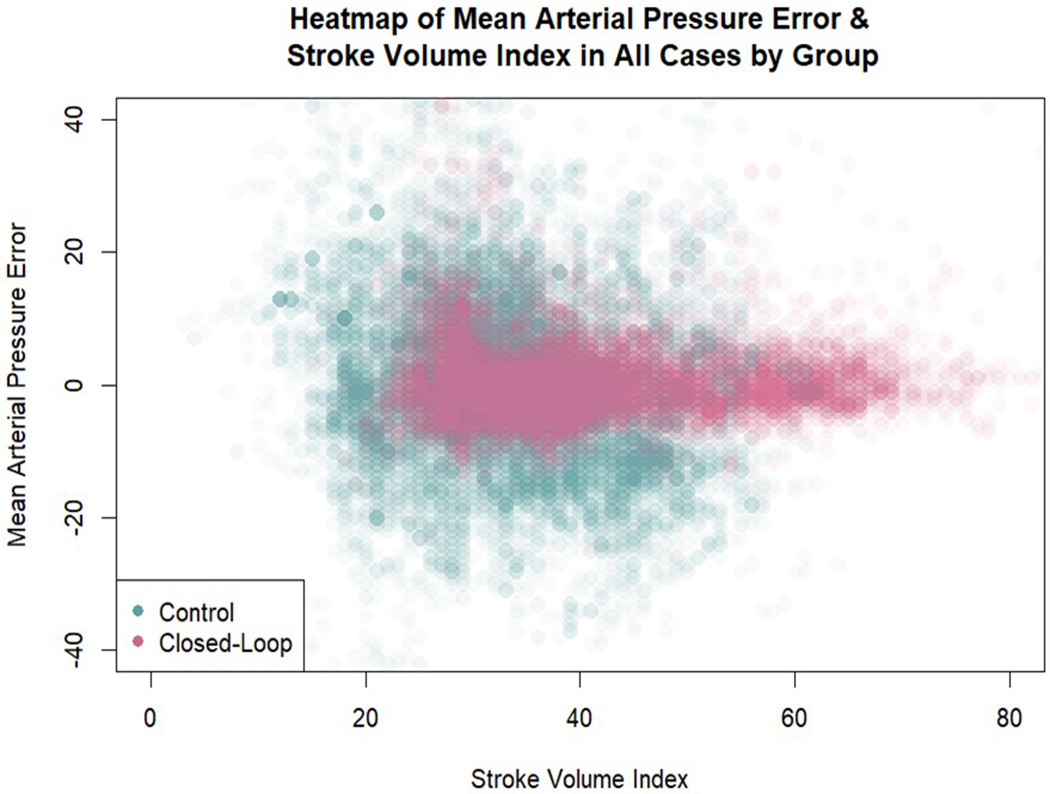

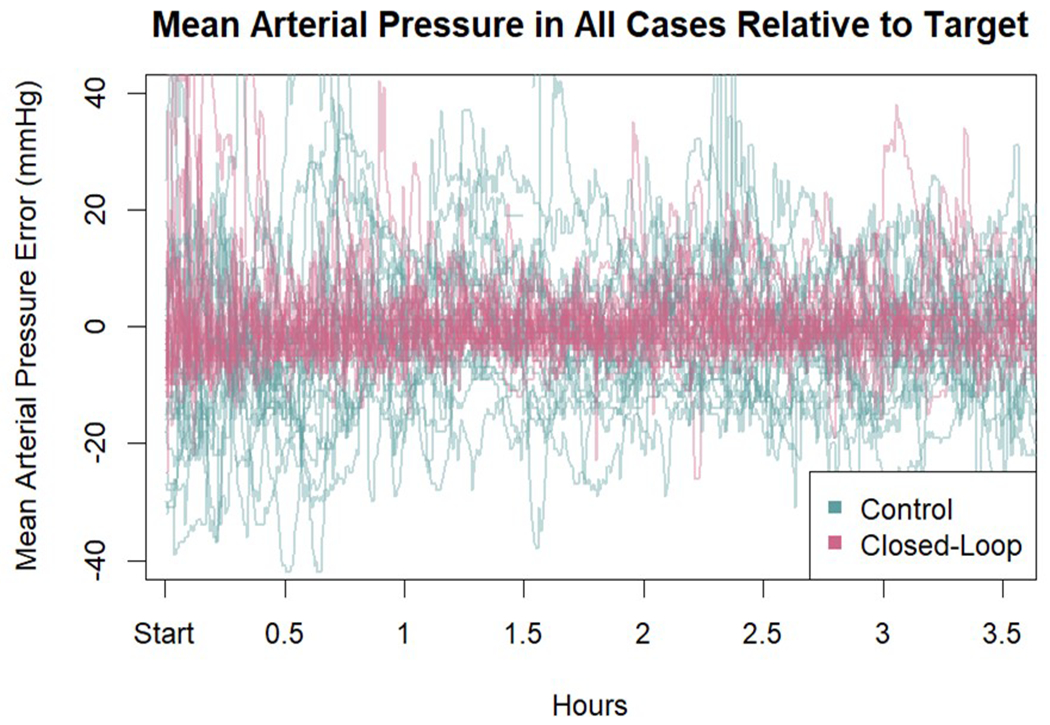

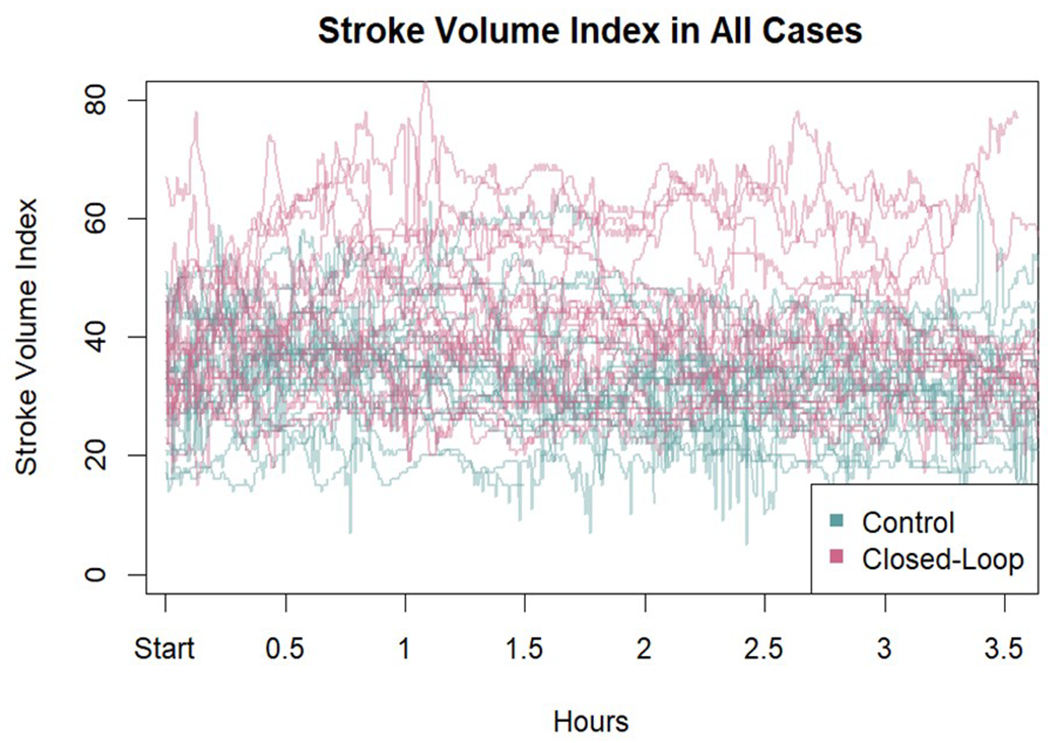

The primary outcome, i.e., the percentage of intraoperative case time a patient had hypotension (defined as a MAP < 90% of their baseline MAP) was 1.2% [0.4-2.0] in the computer-assisted group compared to 21.5% [14.5-31.8] in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group (difference −21.1 (95% CI −15.9 to −27.6); P<0.001) (Table 3). The percentage of intraoperative case time with a MAP <65 mmHg was also lower in the computer-assisted group than in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group (0.0% [0.0-0.0] vs 1.9% [1.2-5.0]; P<0.001). Patients in the computer-assisted group were within the target MAP range (± 10 mmHg of their baseline MAP value) for a greater percentage of time than those in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group (97.2% [95.0-97.7] vs 58.8% [48.3-70.5]; P<0.001). The percentage of time with hypertension (defined as a MAP >10 mmHg of the MAP target) was also lower in the computer-assisted group than in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group (2.5% [1.-4.9] vs 12.9% [5.7-22.8]; P=0.001) (Table 4). A heatmap of MAP error and stroke volume index by group for all patients is shown in Figure 3. The MAP error relative to target MAP in all 38 cases is given in Appendix 3.

Table 3:

Primary and secondary outcome variables

| Variables | Manually adjusted GDT group (N=19) | Computer-assisted GDT group (N=19) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| Intraoperative hypotension (%)* | 21.5 [14.5 - 31.8] | 1.2 [0.4 - 2.0] | <0.001 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Patients with minor complications, N (%) £ | 11 (58) | 8 (42) | 0.330 |

| Postoperative nausea and vomiting | 1 (5) | 3 (16) | 0.290 |

| Delirium / confusion | 1 (5) | 1 (1) | >0.999 |

| Acute kidney injury (KDIGO 1 to 3) | 1 (5) | 2 (11) | 0.547 |

| Superficial wound infection | 5 (21) | 1 (5) | 0.034 |

| Urinary infection | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 0.146 |

| Other infections | 2 (11) | 4 (21) | 0.374 |

| Pneumonia | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | >0.999 |

| Paralytic ileus | 5 (26) | 4 (21) | 0.703 |

| 30-day readmission to hospital | 3 (16) | 1 (5) | 0.290 |

Data are expressed as number and percentage (%) or median [25th -75th] percentiles

Intraoperative hypotension defined as the percentage of case time with a MAP < 90% of MAP target

some patients had more than one minor complication

GDT: goal directed therapy; KDIGO: Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes

Table 4:

Other outcome variables

| Variable | Manually adjusted GDT group (N=19) | Computer-assisted GDT group (N=19) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean stroke volume index (ml.m−2) | 33.5 ± 7.5 | 40.9 ± 9.7 | 0.012 |

| Stroke volume index first 30 minutes (ml.m−2) | 34.8 ± 8.6 | 39.4 ± 9.6 | 0.129 |

| Stroke volume index last 30 minutes (ml.m−2) | 31.7 ± 8.4 | 42.1 ± 10.0 | 0.001 |

| Mean cardiac index (l.min−1.m−2) | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Mean stroke volume variation (%) | 9.6 [7.6-12.5] | 7.3 [6.5-9.6] | 0.022 |

| Percentage of case time with | |||

| ➢ stroke volume index < 30 ml.m−2 | 22.6 [10.6-57.2] | 1.7 [0.0-31.5 ] | 0.030 |

| ➢ cardiac index < 2 l.min−1.m−2 | 21.6 [1.4-38.0] | 1.5 [0.0-3.7] | 0.001 |

| ➢ stroke volume variation < 13 % | 76.6 [60.8-88.3] | 96.1 [86.6-99.2] | 0.001 |

| ➢ MAP ± 10 mmHg of MAP target | 58.8 [48.3-70.5] | 97.2 [95.0-97.7] | <0.001 |

| ➢ MAP > 10 mmHg of MAP target | 12.9 [5.7-22.8] | 2.5 [1.5-4.9] | 0.001 |

| ➢ MAP < 65 mmHg | 1.9 [1.2-5.0] | 0.0 [0.0-0.0] | <0.001 |

| ➢ MAP < 60 mmHg | 0.4 [0.0-2.1] | 0.0 [0.0-0.0] | <0.001 |

| ➢ MAP < 55 mmHg | 0.0 [0.0-0.6] | 0.0 [0.0-0.0] | 0.027 |

| Patients with any major complication, N (%)* | 5 (26) | 2 (10) | 0.209 |

| ➢ Anastamotic leakage | 2 (11) | 1 (5) | 0.547 |

| ➢ Pulmonary edema | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | >0.999 |

| ➢ Reoperation | 3 (16) | 1 (5) | 0.290 |

| ➢ Bleeding | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| ➢ Atrial Fibrillation | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | >0.999 |

| Postoperative hemoglobin (g.dl−1) $ | 10.8 ± 1.9 | 11.3 ± 2.0 | 0.479 |

| Postoperative creatinine (mmol.l−1) $ | 76 [58 - 96] | 76 [61 - 99] | 0.540 |

| PACU-ICU length of stay (hours) | 9.0 [4.0-24.0] | 9.0 [5.0-24.0] | 0.988 |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 9.0 [6.0-16.0] | 7.0 [5.0-16.0] | 0.609 |

Data are expressed as number and percentage (%) or median [25th -75th] percentiles. GDT: goal directed therapy; PACU: post-anesthesia care unit, ICU: intensive care unit.

mortality at 30 days, stroke, renal replacement therapy and pulmonary embolism was 0% in both groups.

postoperative hemoglobin and creatinine was measured on postoperative day 1 or 2.

Figure 3:

Heatmap of mean arterial pressure error and stroke volume index in all cases by group. A total of 34,000 data points are represented in the figure (3 observations of MAP/SVI per minute per patient). Density of color in a location indicates the relative proportion of error for that combination of stroke volume index and mean arterial pressure error. The computer-assisted group error is visually clustered much more tightly than the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group error around zero. Additionally, this figure illustrates higher stroke volume indexes in the computer-assisted group.

All flow-based variables were better maintained within optimal targets during surgery in the computer-assisted group than in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group despite a greater estimated blood loss during surgery in the computer-assisted group. There was no significant difference in baseline SVI between groups, but the average SVI during the last 30 minutes of the case was significantly higher in the computer-assisted group than in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group (P=0.001) Appendix 4 shows SVI in all patients. Importantly, we did not have any missing data among the primary and secondary outcomes.

Lactate concentration at the beginning of the surgery was similar in the two groups, but on arrival in the post-anesthesia care unit, patients in the computer-assisted group had a lower lactate concentration than those in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group (1.2 [0.9-2.3] μmol/L vs. 2.7 [1.6-3.2] μmol/L, P=0.011; Table 2). The incidence of postoperative minor complications (secondary outcome) was not different between groups (computer-assisted: 42%; control: 58%; mean difference 16%, 95% CI −16 to 48; p=0.330, Table 3). Major complications as well as lengths of stay (post-anesthesia care unit, intensive care unit, or hospital), were similar between groups (Table 4). No patient died within 30 days post-surgery.

The closed-loop vasopressor system did not experience any technical failures during use and the anesthesiologists in the computer-assisted group never used backup vasopressor options throughout the surgery. Lastly, the second norepinephrine infusion was never used in the computer-assisted group.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that use of computer-assisted hemodynamic management clearly outperforms standard hemodynamic management in intermediate and high-risk abdominal and orthopedic surgery. Patients in the computer-assisted group had less hypotension, less hypertension, higher mean CI and SVI, and lower lactate concentrations on arrival in the PACU. When using the usual “population” definition of hypotension (MAP < 65 mmHg), patients in the computer-assisted group had no detectable hypotension. Moreover, these results occurred despite twice the amount of blood loss in the computer-assisted group compared to the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group. In addition to all the differences noted above, the computer-assisted group also had lower positive net fluid balance at the end of surgery, and a higher end-case SVI.

One concern with targeting an individualized MAP during surgery may be that CO (flow) may be sacrificed at the expense of pressure, and that hypovolemia may not be corrected if it is hidden by a blood pressure considered as acceptable. However, patients in the computer-assisted group exhibited statistically superior flow-based measures than those in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group. The lower postoperative lactate concentrations in the computer-assisted group compared to the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group suggest that the balance between oxygen transport and oxygen consumption was maintained better in the former group.

Although the incidence of postoperative complications was not significantly different in the two groups, the higher incidence of superficial wound infection in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group could reflect less optimal tissue oxygenation in these patients. A larger study is necessary to evaluate the effect of this strategy on postoperative complications.

Individualized hemodynamic management (previously called “goal directed hemodynamic therapy”) has been associated with improved patient outcomes compared to routine care during major surgery, as recently confirmed by two meta-analysis.28, 29 Futier et al 11 also reported that “individualized” arterial pressure management resulted in less postoperative organ dysfunction. More recently, Nicklas et al demonstrated that individualizing hemodynamic management by using patient baseline CI value as a target to guide fluid administration resulted in fewer postoperative complications.12 However, adoption of these strategies by clinicians has been slow and, even if used during surgery, results may be limited because of poor protocol compliance. Computer-assisted systems may present a bridge between implementing the evidence-based intervention and ensuring compliance, reducing provider workloads while delivering consistent high-compliance therapy that is still directed by the physician. Moreover, the ‘packaging’ of goal-directed strategies into a device reduces the barrier to implementation. Indeed, computer systems are designed for highly repetitive and attention dependent tasks but thankfully do not suffer with problems associated with vigilance fatigue. Therefore, computational systems are consistently more accurate at maintaining a target set point than anesthesia providers. Moreover, the choice of target set points, and indeed whether a given patient should be placed on a protocol in the first place, are decisions that appropriately remain in the hands of the clinicians. As a result, we believe that automated systems are the best option for automation of non-cognitive tasks moving forward. 30, 31

Our study has several limitations that should be considered. Firstly, the principal investigator supervised the computer systems for each patient in the computer-assisted group (in addition to the primary anesthesia provider). This is an impractical setup for widespread adoption, so assurance that the system can be used effectively and safely by a wide range of providers will be necessary for dispersed use. Secondly, the presence of this additional investigator in the operating room also has the potential to confound the results collected (Hawthorne effect), although the interventions in the “computer-assisted group” are mostly decided by the automated systems in place and will unlikely succumb to any significant observation bias. Similarly, as the primary anesthesia care provider in the manual adjusted group was not involved in the current study, it cannot be ruled out that they were less focused at optimizing hemodynamic status than if they were aware of the study purpose. The specific providers present and level of training (i.e. nurse anesthetists, residents of different years, faculty of different levels of experience) in individual cases was not controlled in the present study. It is possible that some effect due to group differences in these dimensions may have been overlooked, though the randomization of assignment should have mitigated this. Thirdly, we were unable to record the amount of surgical time each patient was hypotensive during induction as our system required post induction arterial line placement. It is unfortunate as recording these data would have enabled us to determine whether computer-assisted management functions well with hypotension following induction. Maheswhari et al. demonstrated that approximately 30% of all hypotensive events occur during induction, so management of this period is an important consideration.32 Additionally, the MAP target chosen to define hypotension (MAP taken during the preoperative screening) could of course be challenged especially in view of the recent literature33 but it is the best and the most standardized we have in our institution. Fourthly, our protocol was limited to intermediate to high-risk abdominal and orthopedic surgical procedures and the present findings may not be broadly applicable to other surgeries or clinical settings (e.g., cardiac surgery or intensive care unit). Fifthly, the difference in blood loss between the groups is presumed to be random chance; bleeding episodes were surgical in nature and not due to coagulopathy for example. The design of our study does not rule out the possibility that bleeding might actually be a result of our intervention and not random, however, so this is a question that will also need future study. There is a theoretical risk of increased blood pressure possibly leading to increased bleeding at the surgery site, although the benefits of increased perfusion may outweigh this potential risk. Of note, patients in the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group spent more time during the procedure with a MAP > 10 mmHg above the individualized target. We also cannot rule out an observer effect in the computer-assisted group impacting estimated blood loss estimates, although this difference in estimated blood loss might have been related to the fact that more patients in the computer-assisted group were treated with aspirin.

Future directions

A key consideration for fully automated hemodynamic management is that multiple factors can influence MAP. An ideal computer-assisted hemodynamic management system should be informed not just of current pressure, but also intravascular volume, anesthetic depth, some measure of sympathetic inhibition, heart rate, and cardiac function. Although our closed-loop system can tightly control MAP, it is not sufficient to rely solely on such a system to ensure adequate hemodynamic management. Looking forward, a holistic hemodynamic management system should be able to monitor and modify all the factors implicated in hemodynamic status. Implementation of such systems in clinical practice will still take time – there are many technological, practical, and regulatory considerations. That said, independently operating automated systems have been reported that manage hypnosis, analgesics, fluid and vasopressor administration. There are even recent experiments using several systems simultaneously.34–36 Given all these technological advances in computing power, it is evident that we will see much more of this work in the years to come.37 Specifically regarding fully automated system for both fluid and vasopressor administration, there is only one team (to our knowledge) that has designed such a system although it is still experimental.38, 39 Our team is also actively working on the development of such a system.

Conclusion

In patients undergoing intermediate and high-risk abdominal and orthopedic surgery, use of computer-assisted individualized hemodynamic management significantly reduced intraoperative hypotension compared to the manually adjusted goal directed therapy group. Computer-assisted systems can help anesthesia providers maintain adequate hemodynamic targets during surgery.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental digital content 1: Closed-Loop Vasopressor Controller

Summary statement:

Computer-assisted individualized vasopressor and fluid titration significantly outperforms manual control by reducing intraoperative hypotension and can help anesthesia providers maintain good compliance with goal-directed hemodynamic protocols.

Acknowledgement:

We wish to thank all the anesthesiology and the surgical teams of Bicetre hospital for their support in this study and the sponsor which was Assistance Publique – Hôpitaux de Paris (Délégation à la Recherche Clinique et à l’Innovation)

Research Support: Development of the closed-loop system was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number U54HL119893, and by NIH/NCATS UL1 TR00001414 (Joseph Rinehart). This work was also supported in part by NIH R01 HL144692 and R01 EB029751 (Maxime Cannesson)

Appendix 1:

Manual individualized hemodynamic protocol

Appendix 2:

Computer-assisted set up in the operating room at Bicetre hospital, Le Kremlin Bicetre, France

Appendix 3:

Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) in all cases relative to target

Appendix 4:

Stroke volume index (ml.m−2) in all cases

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03965793 published on May 29, 2019 - Principal Investigator: Alexandre Joosten.

Prior Presentations: None

Authors Conflicts of Interests:

Maxime Cannesson, Alexandre Joosten, and Joseph Rinehart are consultants for Edwards Lifesciences (Irvine, CA, USA), and have ownership interest in Perceptive Medical Inc (Newport beach, CA, USA) which is developing closed-loop physiologic management systems. In addition, Maxime Cannesson and Joseph Rinehart have ownership interest in Sironis (Newport beach, CA, USA), and Sironis has developed a fluid closed-loop system that has been licensed to Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, USA and was used in this study as a decision support system (assisted fluid management). The closed-loop system for vasopressor administration used in this study is new, and is the sole creation of three of the authors (MC, JR and AJ). A provisional patent has been submitted through the University of California Irvine covering aspects of closed-loop vasopressor administration, but does not cover any of the processes discussed in the current manuscript.

The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Reproducible Science: Full protocol (in French only) and raw data available at: joosten-alexandre@hotmail.com or alexandre.joosten@aphp.fr

REFERENCES

- 1.Sessler DI, Bloomstone JA, Aronson S, Berry C, Gan TJ, Kellum JA, Plumb J, Mythen MG, Grocott MPW, Edwards MR, Miller TE. Perioperative Quality Initiative consensus statement on intraoperative blood pressure, risk and outcomes for elective surgery. Br J Anaesth 2019; 122: 563–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wesselink EM, Kappen TH, Torn HM, Slooter AJC, van Klei WA. Intraoperative hypotension and the risk of postoperative adverse outcomes: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth 2018; 121: 706–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh M, Devereaux PJ, Garg AX, Kurz A, Turan A, Rodseth RN, Cywinski J, Thabane L, Sessler DI. Relationship between intraoperative mean arterial pressure and clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery: toward an empirical definition of hypotension. Anesthesiology 2013; 119: 507–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sessler DI, Khanna AK. Perioperative myocardial injury and the contribution of hypotension. Intensive Care Medicine 2018; 44: 811–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sessler DI, Meyhoff CS, Zimmerman NM, Mao G, Leslie K, Vásquez SM, Balaji P, Alvarez-Garcia J, Cavalcanti AB, Parlow JL, Rahate PV, Seeberger MD, Gossetti B, Walker SA, Premchand RK, Dahl RM, Duceppe E, Rodseth R, Botto F, Devereaux PJ. Period-dependent Associations between Hypotension during and for Four Days after Noncardiac Surgery and a Composite of Myocardial Infarction and Death: A Substudy of the POISE-2 Trial. Anesthesiology 2018; 128: 317–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun LY, Wijeysundera DN, Tait GA, Beattie WS. Association of intraoperative hypotension with acute kidney injury after elective noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 2015; 123: 515–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mascha EJ, Yang D, Weiss S, Sessler DI. Intraoperative Mean Arterial Pressure Variability and 30-day Mortality in Patients Having Noncardiac Surgery. Anesthesiology 2015; 123: 79–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roshanov PS, Sheth T, Duceppe E, Tandon V, Bessissow A, Chan MTV, Butler C, Chow BJW, Khan JS, Devereaux PJ. Relationship between Perioperative Hypotension and Perioperative Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease Undergoing Major Noncardiac Surgery. Anesthesiology 2019; 130: 756–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Waes JA, van Klei WA, Wijeysundera DN, van Wolfswinkel L, Lindsay TF, Beattie WS. Association between Intraoperative Hypotension and Myocardial Injury after Vascular Surgery. Anesthesiology 2016; 124: 35–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ngu JMC, Jabagi H, Chung AM, Boodhwani M, Ruel M, Bourke M, Sun LY. Defining an Intraoperative Hypotension Threshold in Association with De Novo Renal Replacement Therapy after Cardiac Surgery. Anesthesiology 2020; 132: 1447–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Futier E, Lefrant JY, Guinot PG, Godet T, Lorne E, Cuvillon P, Bertran S, Leone M, Pastene B, Piriou V, Molliex S, Albanese J, Julia JM, Tavernier B, Imhoff E, Bazin JE, Constantin JM, Pereira B, Jaber S. Effect of Individualized vs Standard Blood Pressure Management Strategies on Postoperative Organ Dysfunction Among High-Risk Patients Undergoing Major Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama 2017; 318: 1346–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicklas JY, Diener O, Leistenschneider M, Sellhorn C, Schön G, Winkler M, Daum G, Schwedhelm E, Schröder J, Fisch M, Schmalfeldt B, Izbicki JR, Bauer M, Coldewey SM, Reuter DA, Saugel B. Personalised haemodynamic management targeting baseline cardiac index in high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery: a randomised single-centre clinical trial. Br J Anaesth 2020; 125: 122–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rinehart J, Lilot M, Lee C, Huynh T, Canales C, Imagawa D, Demirjian A, Cannesson M. Closed-loop assisted versus manual goal-directed fluid therapy during high-risk abdominal surgery: a case-control study with propensity matching. Crit Care 2015; 19: 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joosten A, Huynh T, Suehiro K, Canales C, Cannesson M, Rinehart J. Goal-Directed fluid therapy with closed-loop assistance during moderate risk surgery using noninvasive cardiac output monitoring: A pilot study. Br J Anaesth 2015; 114: 886–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joosten A, Raj Lawrence S, Colesnicenco A, Coeckelenbergh S, Vincent JL, Van der Linden P, Cannesson M, Rinehart J. Personalized Versus Protocolized Fluid Management Using Noninvasive Hemodynamic Monitoring (Clearsight System) in Patients Undergoing Moderate-Risk Abdominal Surgery. Anesth Analg 2019; 129: e8–e12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joosten A, Alexander B, Duranteau J, Taccone FS, Creteur J, Vincent JL, Cannesson M, Rinehart J. Feasibility of closed-loop titration of norepinephrine infusion in patients undergoing moderate- and high-risk surgery. Br J Anaesth 2019. October;123(4):430–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joosten A, Delaporte A, Alexander B, Su F, Creteur J, Vincent JL, Cannesson M, Rinehart J. Automated Titration of Vasopressor Infusion Using a Closed-loop Controller: In Vivo Feasibility Study Using a Swine Model. Anesthesiology 2019; 130: 394–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joosten A, Chirnoaga D, Van der Linden P, Barvais L, Alexander B, Duranteau J, Vincent JL, Cannesson M, Rinehart J. Automated closed-loop versus manually controlled norepinephrine infusion in patients undergoing intermediate- to high-risk abdominal surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 2020. January;126(1):210–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kristensen SD, Knuuti J, Saraste A, Anker S, Bøtker H, De Hert S, Ford I, Ramón Gonzalez-Juanatey J, Gorenek B, Heyndrickx G, Hoeft A, Huber K, Iung B, Kjeldsen K, Longrois D, Lüscher T, Pierard L, Pocock S, Price S, Roffi M, Anton Sirnes P, Sousa-Uva M, Voudris V, Funck-Brentano C. 2014 ESC/ESA Guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management: The Joint Task Force on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA). Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 2383–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinehart J, Ma M, Calderon MD, Cannesson M. Feasibility of automated titration of vasopressor infusions using a novel closed-loop controller. J Clin Monit Comput 2018; 32: 5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rinehart J, Joosten A, Ma M, Calderon MD, Cannesson M. Closed-loop vasopressor control: in-silico study of robustness against pharmacodynamic variability. J Clin Monit Comput 2019; 33: 795–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joosten A, Coeckelenbergh S, Alexander B, Cannesson M, Rinehart J. Feasibility of computer-assisted vasopressor infusion using continuous non-invasive blood pressure monitoring in high-risk patients undergoing renal transplant surgery. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2020. October;39(5):623–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rinehart J, Cannesson M, Weeraman S, Barvais L, Obbergh LV, Joosten A. Closed-Loop Control of Vasopressor Administration in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Revascularization Surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2020. November;34(11):3081–3085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joosten A, Hafiane R, Pustetto M, Van Obbergh L, Quackels T, Buggenhout A, Vincent JL, Ickx B, Rinehart J. Practical impact of a decision support for goal-directed fluid therapy on protocol adherence: a clinical implementation study in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. J Clin Monit Comput 2019; 33: 15–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joosten A, Delaporte A, Ickx B, Touihri K, Stany I, Barvais L, Van Obbergh L, Loi P, Rinehart J, Cannesson M, Van der Linden P. Crystalloid versus Colloid for Intraoperative Goal-directed Fluid Therapy Using a Closed-loop System: A Randomized, Double-blinded, Controlled Trial in Major Abdominal Surgery. Anesthesiology 2018; 128: 55–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joosten A, Coeckelenbergh S, Delaporte A, Ickx B, Closset J, Roumeguere T, Barvais L, Van Obbergh L, Cannesson M, Rinehart J, Van der Linden P. Implementation of closed-loop-assisted intra-operative goal-directed fluid therapy during major abdominal surgery: A case-control study with propensity matching. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2018; 35: 650–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rinehart J, Ma M, Calderon MD, Bardaji A, Hafiane R, Van der Linden P, Joosten A. Blood pressure variability in surgical and intensive care patients: Is there a potential for closed-loop vasopressor administration? Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2019; 38: 69–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng QW, Tan WC, Zhao BC, Wen SH, Shen JT, Xu M. Is goal-directed fluid therapy based on dynamic variables alone sufficient to improve clinical outcomes among patients undergoing surgery? A meta-analysis. Crit Care 2018; 22: 298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chong MA, Wang Y, Berbenetz NM, McConachie I. Does goal-directed haemodynamic and fluid therapy improve peri-operative outcomes?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2018; 35: 469–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joosten A, Rinehart J. Part of the Steamroller and Not Part of the Road: Better Blood Pressure Management Through Automation. Anesth Analg 2017; 125: 20–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michard F, Liu N, Kurz A. The future of intraoperative blood pressure management. J Clin Monit Comput 2018; 32: 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maheshwari K, Turan A, Mao G, Yang D, Niazi AK, Agarwal D, Sessler DI, Kurz A. The association of hypotension during non-cardiac surgery, before and after skin incision, with postoperative acute kidney injury: a retrospective cohort analysis. Anaesthesia 2018; 73: 1223–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saugel B, Reese PC, Sessler DI, Burfeindt C, Nicklas J, Pinnschmidt H, Reuter D, Südfeld S. Automated Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurements and Intraoperative Hypotension in Patients Having Noncardiac Surgery with General Anesthesia: A Prospective Observational Study. Anesthesiology 2019; 131: 74–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joosten A, Delaporte A, Cannesson M, Rinehart J, Dewilde JP, Van Obbergh L, Barvais L. Fully Automated Anesthesia and Fluid Management Using Multiple Physiologic Closed-Loop Systems in a Patient Undergoing High-Risk Surgery. A A Case Rep 2016; 7: 260–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joosten A, Jame V, Alexander B, Chazot T, Liu N, Cannesson M, Rinehart J, Barvais L. Feasibility of Fully Automated Hypnosis, Analgesia, and Fluid Management Using 2 Independent Closed-Loop Systems During Major Vascular Surgery: A Pilot Study. Anesth Analg 2019; 128: e88–e92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joosten A, Rinehart J, Bardaji A, Van der Linden P, Jame V, Van Obbergh L, Alexander B, Cannesson M, Vacas S, Liu N, Slama H, Barvais L. Anesthetic Management Using Multiple Closed-loop Systems and Delayed Neurocognitive Recovery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology 2020; 132: 253–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hemmerling TM. Robots Will Perform Anesthesia in the Near Future. Anesthesiology 2020; 132: 219–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Libert N, Chenegros G, Harrois A, Baudry N, Cordurie G, Benosman R, Vicaut E, Duranteau J. Performance of closed-loop resuscitation of haemorrhagic shock with fluid alone or in combination with norepinephrine: an experimental study. Ann Intensive Care 2018; September 17;8(1):89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Libert N, Chenegros G, Harrois A, Baudry N, Decante B, Cordurie G, Benosman R, Mercier O, Vicaut E, Duranteau J. Performance of closed-loop resuscitation in a pig model of haemorrhagic shock with fluid alone or in combination with norepinephrine, a pilot study. J Clin Monit Comput 2020. June 12 ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental digital content 1: Closed-Loop Vasopressor Controller