Abstract

Weight loss, the most established therapy for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is frequently followed by weight regain and fluctuation. The aim of this study was to investigate whether body weight change and variability were independent risk factors for incident NAFLD. We conducted a longitudinal cohort study. Among the 1907 participants, incident NAFLD occurred in 420 (22.0%) cases during median follow-up of 5.6 years. In the multivariate analysis, there was no significant association between weight variability and the risk of incident NAFLD. The risk of incident NAFLD was significantly higher in subjects with weight gain ≥ 10% and 7% < gain ≤ 10% [hazard ratios (HR), 2.43; 95% confidence intervals (CI), 1.65–3.58 and HR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.26–2.39, respectively], while the risk of incident NAFLD was significantly lower in those with −7% < weight loss ≤ -−3% (HR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.22–0.51). Overall body weight gain rather than bodyweight variability was independently associated with the risk of incident NAFLD. Understanding the association between body weight variability and incident NAFLD may have future clinical implications for the quantification of weight loss as a treatment for patients with NAFLD.

Subject terms: Hepatology, Obesity

Introduction

Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease worldwide1,2. It encompasses a spectrum of progressive liver disease from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis, hepatic fibrosis, and cirrhosis3. Obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and dyslipidemia are the key risk factors for the development of NAFLD. Although there is no currently available treatment for NAFLD, there have been several studies showing that NAFLD is somewhat reversible. Changes in lifestyle habits such as weight reduction, and regular exercise were associated with remission of NAFLD4.

Body weight loss is the most established therapy for obesity-associated metabolic risk factors and NAFLD, with an evident dose-dependent association5. Accordingly, several guidelines recommend a 7–10% weight loss as the target of lifestyle modifications in overweight or obese NAFLD patients6–8. However, weight loss is frequently followed by weight regain or variability, with 80% of subjects who lose > 10% weight regaining it within one year9. Recent studies have reported that weight variability is associated with the increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with established coronary artery disease10 or diabetes mellitus11. Furthermore, weight variability has been found to be associated with higher risk of incident type 2 diabetes in the general population12,13. However, few studies have investigated the association between weight variability and NAFLD. In addition, differences in its effects regarding baseline weight or change in weight have yet to be evaluated.

Therefore, the aim of the present study is to investigate whether body weight variability and weight change are independent risk factors for incident NAFLD in a health check-up population.

Methods

Study population

The study participants were part of a previous cohort study14. Briefly, the initial cohort for this study consisted of 34,080 subjects who had completed a comprehensive health check-up including abdominal ultrasonography and laboratory exams from January 2007 to February 2015 at Seoul National University Hospital Healthcare System Gangnam Center. Baseline and follow-up examinations were conducted annually or biennially between March 2008 and December 2017 at the same institute. Individuals who have at least one cause of chronic liver disease were excluded; positive for serum hepatitis B surface antigen, positive for antibody against hepatitis C virus, and/or a history of chronic liver disease as identified by a detailed questionnaire. Among them, we enrolled subjects who had undergone more than three exams with an interval of one year or more between each test.

The total number of eligible subjects for the study was 5636 at baseline. We excluded 2258 participants with NAFLD at the time of baseline and 1382 subjects with significant alcohol consumption (> 30 g/day for men and > 20 g/day for women)7. We further excluded 89 subjects with missing baseline information. As a result, a total of 1907 participants were included in the analysis. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (2003-122-1110) and confirmed to the ethical guidelines of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. As the study used de-identified secondary data, the requirement for informed consent from individuals was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital.

Clinical parameters and biochemical analysis

As previously described15, standardized self-reported questionnaires were used to collect data at the time of enrollment. Height and weight were measured using a digital scale. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of the person’s height (m). Well-trained personnel measured the waist circumference (WC) at the midpoint between the lower costal margin and the iliac crest. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured twice on the same day. Systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mm Hg and/or previous use of antihypertensive medication were used to define hypertension. Fasting glucose levels ≥ 126 mg/dL and/or an oral hypoglycemic agent or insulin treatment were defined as clinical presentations of diabetes mellitus.

After an overnight fast of ≥ 8 h, blood specimens were obtained from each participant. Laboratory tests included serum levels of total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose and alanine transaminase (ALT).

Definition of body weight variability and change

Intra-individual body weight variability can be measured by various methods. Widely used indices in previous studies include standard deviation (SD), coefficient of variation (CV), average real variability (ARV), and variability independent of the mean (VIM)16,17. CV is calculated as the ratio of SD to the mean. ARV is defined as the average absolute differences between successive body weight measurements and reflects the order of measurements. VIM is a measure of variability that has no correlation with mean levels over visits. VIM is calculated as the SD divided by the mean to the power x and multiplied by the population mean to the power x, that is the regression coefficient based on the natural logarithm of the SD over the natural logarithm of the mean17. We divided the body weight variability indices into quartiles for analysis (Q1 = lowest quartile; Q4 = highest quartile). In addition, we categorized the overall body weight change (OBC) into three or seven groups to evaluate the direction of body weight variability; [loss ≥—5%, < -5% to < 5%, and gain ≥ 5%] and [loss ≥—10%, -10% < loss ≤ -7%, -7% < loss ≤ -3%, < -3% to < 3%, 3% < gain ≤ 7%, 7% < gain ≤ 10%, and gain ≥ 10%]16.

Definitions of NAFLD

NAFLD was defined by the evidence of hepatic steatosis based on the characteristic ultrasonographic features without excessive alcohol consumption or concomitant liver disease6,7. Hepatic ultrasonography (Acuson Sequoia 512; Siemens, Mountain View, CA) was performed to diagnose fatty liver by experienced radiologists who were blinded to the clinical characteristics of the subjects. Fatty liver was diagnosed based on characteristic ultrasonographic features consistent with a ‘‘bright liver,’’ evident contrast between hepatic and renal parenchyma, vessel blurring, focal sparing, and luminal narrowing of the hepatic veins18.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed, continuous variables and as proportions for categorical variables, unless otherwise indicated. Log transformations were performed for non-normally distributed variables. The comparison of baseline characteristics was conducted using independent t-tests and analysis of variance for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Among variables with a P value < 0.05 in univariate analyses, those with clinical importance were subjected to multivariate analyses. Cox-proportional hazard regression was performed to estimate the risk of incident NAFLD. To control for confounding, we adjusted the model for baseline body weight, age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, waist circumference, BMI, triglyceride, HDL-cholesterol, ALT, and number of measurements. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R version 4.0.4 (R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, http://www.Rproject.org). A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study population

The mean age of the study population was 50.8 years, and 47.6% was male. Among the total 1,907 subjects, incident NAFLD occurred in 420 (22.0%) cases during the median follow-up period of 5.6 years (interquartile range, 4.6–6.3). The mean number of weight measurements was 6.7 ± 3.1 and the body weight of each subject was measured 3 times (15.8%), 4 times (15.2%), or more than 5 times (69.0%).

The baseline characteristics of the subjects according to quartiles of weight variability are shown in Table 1. Higher weight variability was more frequently discovered in subjects who were younger and in males with higher waist circumference and BMI. Total cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol levels decreased with higher weight variability, whereas triglyceride showed an increasing trend with higher weight variability. Fasting glucose and ALT levels were not significantly different between the groups. Prevalence of diabetes and hypertension were also similar across the groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population according to quartiles of weight variability.

| Q1 (lowest) | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 (highest) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 477 | N = 480 | N = 477 | N = 473 | ||

| Age (years) | 51.3 ± 8.9 | 51.3 ± 8.0 | 51.1 ± 8.6 | 49.3 ± 9.4 | < 0.001 |

| Male (number, percent) | 206 (43.2%) | 226 (47.1%) | 217 (45.5%) | 258 (54.5%) | 0.003 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 79.8 ± 7.2 | 81.6 ± 6.7 | 81.5 ± 7.2 | 82.8 ± 7.0 | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.8 ± 2.4 | 22.3 ± 2.3 | 22.3 ± 2.4 | 22.9 ± 2.5 | < 0.001 |

| Weight change | < 0.001 | ||||

| < -5% | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (1.5%) | 34 (7.1%) | 119 (25.2%) | |

| −5 to 5% | 477 (100.0%) | 451 (94.0%) | 335 (70.2%) | 154 (32.6%) | |

| ≥ 5% | 0 (0.0%) | 22 (4.6%) | 108 (22.6%) | 200 (42.3%) | |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Diabetes | 21 (4.4%) | 16 (3.3%) | 15 (3.1%) | 24 (5.1%) | 0.380 |

| Hypertension | 44 (9.2%) | 48 (10.0%) | 53 (11.1%) | 60 (12.7%) | 0.340 |

| Laboratory findings | |||||

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 92.1 ± 14.5 | 91.5 ± 13.2 | 91.2 ± 11.9 | 92.5 ± 16.1 | 0.820 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 196.5 ± 33.3 | 191.6 ± 32.7 | 193.2 ± 32.1 | 189.2 ± 31.5 | 0.003 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 58.3 ± 13.4 | 56.1 ± 12.8 | 56.9 ± 12.2 | 54.7 ± 12.4 | < 0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 81.2 ± 43.9 | 85.0 ± 40.4 | 85.0 ± 43.7 | 90.6 ± 48.2 | 0.002 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 20.2 ± 10.3 | 21.0 ± 13.7 | 20.8 ± 12.0 | 21.3 ± 12.0 | 0.230 |

| Number of weight measurements | 0.004 | ||||

| 3 (number, percent) | 99 (20.8%) | 71 (14.8%) | 61 (12.8%) | 71 (15.0%) | |

| 4 (number, percent) | 94 (19.7%) | 56 (11.7%) | 62 (13.0%) | 77 (16.3%) | |

| 5 (number, percent) | 52 (10.9%) | 50 (10.4%) | 59 (12.4%) | 55 (11.6%) | |

| 6 (number, percent) | 61 (12.8%) | 68 (14.2%) | 64 (13.4%) | 53 (11.2%) | |

| More than 7 (number, percent) | 172 (36.1%) | 235 (49.0%) | 231 (48.4%) | 217 (45.9%) | |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and n (%) for categorical variables.

Q quartile, HDL high density lipoprotein, ALT alanine transaminase.

Body weight variability and incident NAFLD

First, we evaluated the association of weight variability and incident NAFLD (Table 2). In the univariate analysis, most body weight variability indices including SD, CV and VIM were significantly associated with lower risk of incident NAFLD (p < 0.05). However, no significant association between weight variability and the risk of incident NAFLD after adjusting for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, waist circumference, BMI, total cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL-cholesterol levels, ALT, and number of measurements. Similar results were observed when subjects were divided according to the direction of weight change metrics (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2.

The risk of incident NAFLD regarding level of body weight variability.

| Body weight variability | No. of patients | No. of events | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Overall P-value |

Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Overall P-value |

|||

| SD | ||||||||

| Q1 | 477 | 81 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | ||||

| Q2 | 480 | 100 | 0.71 (0.53, 0.95) | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.75 (0.55, 1.01) | 0.06 | 0.23 |

| Q3 | 477 | 105 | 0.75 (0.56, 1.00) | 0.05 | 0.77 (0.57, 1.04) | 0.09 | ||

| Q4 | 473 | 134 | 0.94 (0.72, 1.25) | 0.69 | 0.85 (0.64, 1.13) | 0.27 | ||

| CV | ||||||||

| Q1 | 483 | 98 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | ||||

| Q2 | 481 | 103 | 0.71 (0.54, 0.94) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.82 (0.62, 1.08) | 0.16 | 0.31 |

| Q3 | 469 | 103 | 0.64 (0.49, 0.85) | 0.002 | 0.78 (0.59, 1.04) | 0.09 | ||

| Q4 | 474 | 116 | 0.7 (0.54, 0.92) | 0.01 | 0.8 (0.60, 1.06) | 0.12 | ||

| ARV | ||||||||

| Q1 | 464 | 88 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | ||||

| Q2 | 470 | 97 | 0.87 (0.65, 1.16) | 0.34 | 0.08 | 1.01 (0.75, 1.36) | 0.94 | 0.90 |

| Q3 | 492 | 120 | 1.03 (0.78, 1.35) | 0.85 | 1.03 (0.78, 1.36) | 0.85 | ||

| Q4 | 481 | 115 | 1.24 (0.94, 1.63) | 0.13 | 0.93 (0.70, 1.24) | 0.63 | ||

| VIM | ||||||||

| Q1 | 484 | 95 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | ||||

| Q2 | 478 | 101 | 0.7 (0.53, 0.93) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.81 (0.60, 1.07) | 0.14 | 0.39 |

| Q3 | 470 | 104 | 0.66 (0.50, 0.88) | 0.004 | 0.81 (0.61, 1.08) | 0.16 | ||

| Q4 | 475 | 120 | 0.75 (0.57, 0.98) | 0.04 | 0.82 (0.62, 1.08) | 0.15 | ||

Adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, waist circumference, body mass index, triglyceride, high density cholesterol, total cholesterol, alanine transaminase, and number of measurements.

NAFLD nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, CI confidence interval, SD standard deviation, CV coefficient of variation, ARV average real variability, VIM variability independent of mean, Q quartile.

Incident NAFLD risk according to overall weight change

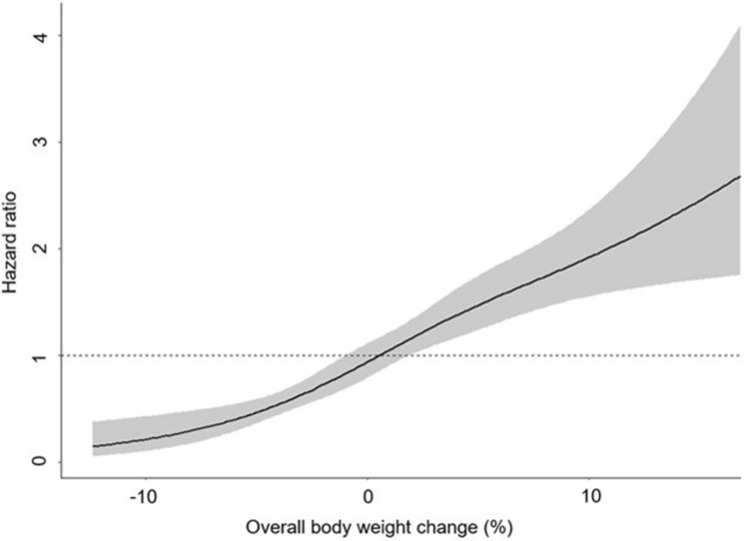

Next, we evaluated the effect of OBC on the development of NAFLD. OBC per 10% increase was associated with the risk of NAFLD development (adjusted HR 2.28, 95% CI, 1.90–2.74). When the participants were categorized into three groups according to OBC, the risk of incident NAFLD increased 63% for those who gained ≥ 5% of body weight, and decreased 65% for subjects who lost ≥ 5% of body weight [adjusted hazard ration (HR) 1.63, 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.30–2.04 and adjusted HR 0.35, 95% CI, 0.21–0.59, respectively, Table 3]. When the subjects were further divided into 7 groups, the risk of incident NAFLD significantly increased in two groups including weight gain ≥ 10% and 7% ≤ gain < 10% (adjusted HR 2.43, 95% CI, 1.65–3.58 and adjusted HR 1.73, 95% CI, 1.26–2.39, respectively), while the risk of incident NAFLD significantly decreased in the group with -7% < weight loss ≤ -3% (adjusted HR 0.33, 95% CI, 0.22–0.51, Table 3). The HR ratio plot dysplaying the correlation between OBC and risk of incident NAFLD is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Table 3.

The risk of NAFLD according to overall bodyweight change.

| Overall bodyweight change | No. of patients | No. of events | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Overall P-value |

Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Overall P-value |

|||

| Per 10% increase | 1907 | 420 | 1.81 (1.53, 2.14) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 2.28 (1.90, 2.74) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Loss ≥ 5% | 160 | 16 | 0.39 (0.23, 0.64) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.35 (0.21, 0.59) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Stable weight (within ± 5% change) | 1417 | 288 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||||

| Gain ≥ 5% | 330 | 116 | 1.40 (1.13, 1.74) | 0.002 | 1.63 (1.30, 2.04) | < 0.001 |

| Loss ≥ 10% | 24 | 2 | 0.28 (0.07, 1.12) | 0.07 | < 0.001 | 0.3 (0.07, 1.21) | 0.10 | < 0.001 |

| 10% < loss ≤ 7% | 56 | 7 | 0.56 (0.26, 1.19) | 0.13 | 0.53 (0.25, 1.13) | 0.10 | ||

| 7% < loss ≤ 3% | 254 | 24 | 0.31 (0.21, 0.48) | < 0.001 | 0.33 (0.22, 0.51) | < 0.001 | ||

| Stable weight (within ± 3% change) | 985 | 207 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||||

| 3% ≤ gain < 7% | 407 | 98 | 0.9 (0.71, 1.14) | 0.38 | 1.19 (0.93, 1.52) | 0.17 | ||

| 7% ≤ gain < 10% | 112 | 49 | 1.69 (1.24, 2.31) | < 0.001 | 1.73 (1.26, 2.39) | < 0.001 | ||

| Gain ≥ 10% | 69 | 33 | 1.51 (1.04, 2.18) | 0.03 | 2.43 (1.65, 3.58) | < 0.001 |

Adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, waist circumference, body mass index, triglyceride, high density cholesterol, total cholesterol, alanine transaminase, and number of measurements.

NAFLD nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, CI confidence interval.

Figure 1.

The hazard ratio plot showing the correlation between overall body weight change and risk of incident NAFLD. The models were fitted with restricted cubic splines with 4 knots placed at the 5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles of overall body weight change (model selection and knot placement via Bayesian information criterion) and the curves were adjusted for variables in a multivariate model including age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, waist circumference, body mass index, ALT, triglyceride, high density cholesterol and total cholesterol. NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; ALT, alanine transaminase.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that overall weight gain of more than 7% significantly increased the risk of incident NAFLD while weight loss of more than 3% reduced the risk of incident NAFLD. Also, overall weight gain was associated with increased risk of incident NAFLD in a dose-dependent manner. However, body weight variability was not associated with the risk of NAFLD. These findings suggest that overall weight change, more than weight variability is associated with the NAFLD development.

Several studies have demonstrated the association between weight loss and the improvement of NAFLD. A 5% or greater weight reduction for one year was associated with ALT improvement and a 3.6-fold increased rate of ALT normalization, suggesting that a 5% reduction in body weight could be recommended as an initial therapeutic target for NAFLD patients4. However, one limitation of this study is that an elevated level of transaminase was used as a surrogate marker of NAFLD. A randomized controlled trial showed that a 7% to 10% weight reduction through intensive lifestyle intervention for 48 weeks resulted in improvements in liver chemistry and histology of steatosis, necro-inflammation19. The participants in this study were required to have elevated ALT > 41 and BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, and histologically confirmed non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Another prospective study reported that greater (≥ 10%) weight loss was associated with the level of improvement in histologic features of NASH including fibrosis, or portal inflammation4. A recent study showed that the frequency of NAFLD remission reached a plateau of 43% in subjects with 1–2%/year weight loss20. Similar with previous results, in the present study, weight loss between 3 and 7% was associated with a decreased risk of incident NAFLD, suggesting that even a weight loss rate less than 5% may help improve NAFLD. There was no significant association between weight loss more than 7% and the risk of incident NAFLD in this study, which might be due to the small number of patients (24 in the group with loss ≥ 10% and 56 in the group of 10% < loss ≤ 7%, respectively).

Body weight gain is a well-known risk factor of NAFLD. In a prospective study with a 7-year follow-up, weight gain was independently associated with incident NAFLD (odds ratio = 1.14)21. Another study found that body weight gain in earlier and later adulthood were all associated with increased risk of NAFLD, with relation to insulin and insulin resistance as key mediators22. A large-population study performed among Korean men showed that subjects with weight gain more than 2.3 kg had an approximately 26% higher risk of NAFLD compared to those with stable body weight23. However, the quartile was divided based on the absolute value of weight change without taking into account the relative ratio of individual weight change. In this study, overall weight gain was associated with increased risk of incident NAFLD in a dose-dependent manner, as 7% ≤ gain < 10% with aHR 1.73 and gain ≥ 10% with aHR 2.43, respectively.

Although weight loss is commonly recommended as a lifestyle modification in NAFLD patients, weight loss is usually followed by weight gain, leading to weight variability8. The effect of body weight variability on clinical prognosis is still controversial24,25. Several studies have reported that weight variability was associated with incident diabetes in obese patients13,26, and the linking mechanism is suggested as insulin resistance27. On the contrary, a community-based prospective cohort study reported that weight variability was a risk factor for abdominal obesity; however, it did not increase the risk of metabolic syndrome28. An analysis of Framingham study participants showed that BMI variability was associated with higher risks of getting type 2 diabetes (58%), and getting hypertension (74%) among nonobese participant29. However, subjects with high BMI variability were also 163% more likely to get obesity, indicating mixed effects of overall weight gain and weight variability. In addition, a recent study based on the secondary analysis of randomized controlled trial results reported that weight variability did not have significant association with changes in cardio-metabolic risk factors or body composition whereas weight loss improved outcome independent of the degree of variability30. Similar with these results, body weight variability per se was not associated with the risk of NAFLD in our study, suggesting that the overall weight change is more important than weight variability in the process of NAFLD development. In this study, the population comprised mostly of lean/non-obese subjects with mean BMI of 22.5 kg/m2 at baseline, and laboratory measurements were, on average, within a healthy range. Weight variability is considered as a risk factor for disease specifically in metabolically unhealthy and underweight or overweight/obese populations31–33, and therefore effects may be limited in our study.

Recently, a term of “metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD)” is proposed in patients with fatty liver34. MAFLD include fatty liver patients with other etiologies including alcohol and concomitant liver disease, and exclude NAFLD patients with less than 2 metabolic abnormalities. This term is better to identify population who are at a higher risk of metabolic disease-related outcomes than traditional NAFLD. As we could not evaluate metabolic syndrome components at the follow up time, we could not assess the association of weight variability and incident MAFLD. Further studies are warranted to evaluate the impacts of weight variability on the disease course of MAFLD.

The present study has some limitations. First, we were unable to obtain liver histological samples, the gold standard for the diagnosis of NAFLD. Ultrasonography may produce false-negative results when fatty infiltration of the liver falls below 20%35, representing inter- and intra-observer diagnostic variability. In addition, we could not assess the disease severity of NAFLD since ultrasonography cannot differentiate nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) from NASH and noninvasive fibrosis markers or serum ALT at the follow up time were not available in this study. Second, this study’s cohort is a selected population, and may not be representative of the general population. Considering that the study population consisted mainly of relatively healthy subjects, majority of the incident NAFLD cases might present NAFL rather than NASH. Third, although unintentional weight change may be attributed to some underlying diseases, we could not evaluate whether the body weight changes were intentional or unintentional. Lastly, this study lacks information on the dietary habits or physical activity of the participants. Further studies are needed to validate our results.

In conclusion, overall body weight changes rather than bodyweight variability was found to be independently associated with the risk of incident NAFLD. High levels of weight gain more than 7% were significantly associated with incident NAFLD, while 3% to 7% weight loss was associated with decreased risk of incident NAFLD. Such results may have clinical implications for weight loss quantification guidelines for treatment of NAFLD patients.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

E.J.C. and G.E.C. drafted and revised the manuscript. S.J.Y., M.-S.K., J.I.Y., J.Y.Y. collected and reviewed the data and revised the manuscript. G.C.J. performed the statistical analysis and revised the manuscript. G.E.C. conceived the idea, developed the study design, collected the data, and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-93883-5.

References

- 1.Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Younossi ZM. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease—A global public health perspective. J. Hepatol. 2019;70:531–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen JC, Horton JD, Hobbs HH. Human fatty liver disease: Old questions and new insights. Science. 2011;332:1519–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.1204265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki A, Lindor K, St Saver J, et al. Effect of changes on body weight and lifestyle in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2005;43:1060–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vilar-Gomez, E., Martinez-Perez, Y., Calzadilla-Bertot, L., et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology149, 367–78.e5, quiz e14–5 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.European Association for the Study of the L, European Association for the Study of D, European Association for the Study of O. EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol.64, 1388–1402 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67:328–357. doi: 10.1002/hep.29367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Guideline Centre (UK). Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Assessment and Management. (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2016). [PubMed]

- 9.Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005;82:222s–225s. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bangalore S, Fayyad R, Laskey R, et al. Body-weight fluctuations and outcomes in coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:1332–1340. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeboah P, Hsu FC, Bertoni AG, et al. Body mass index, change in weight, body weight variability and outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus (from the ACCORD trial) Am. J. Cardiol. 2019;123:576–581. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kataja-Tuomola M, Sundell J, Männistö S, et al. Short-term weight change and fluctuation as risk factors for type 2 diabetes in Finnish male smokers. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010;25:333–339. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9444-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park, K. Y., Hwang, H. S., Cho, K. H. et al. Body weight fluctuation as a risk factor for type 2 diabetes: Results from a Nationwide Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med.8, 950 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Chung GE, Heo NJ, Kim D, et al. Association between advanced fibrosis in fatty liver disease and overall mortality based on body fat distribution. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;35:90–96. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung GE, Kim D, Kwak MS, et al. The serum vitamin D level is inversely correlated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2016;22:146–151. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2016.22.1.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee HJ, Choi EK, Han KD, et al. Bodyweight fluctuation is associated with increased risk of incident atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yano Y. Visit-to-visit blood pressure variability—What is the current challenge? Am. J. Hypertens. 2017;30:112–114. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpw124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angulo P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:1221–1231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra011775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Promrat K, Kleiner DE, Niemeier HM, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:121–129. doi: 10.1002/hep.23276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshioka N, Ishigami M, Watanabe Y, et al. Effect of weight change and lifestyle modifications on the development or remission of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Sex-specific analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:481. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57369-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zelber-Sagi S, Lotan R, Shlomai A, et al. Predictors for incidence and remission of NAFLD in the general population during a seven-year prospective follow-up. J. Hepatol. 2012;56:1145–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du S, Wang C, Jiang W, et al. The impact of body weight gain on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome during earlier and later adulthood. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2016;116:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang Y, Ryu S, Sung E, et al. Weight gain within the normal weight range predicts ultrasonographically detected fatty liver in healthy Korean men. Gut. 2009;58:1419–1425. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.161885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor CB, Jatulis DE, Fortmann SP, et al. Weight variability effects: A prospective analysis from the Stanford Five-City Project. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1995;141:461–465. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turicchi, J., O'Driscoll, R., Horgan, G., et al. Body weight variability is not associated with changes in risk factors for cardiometabolic disease. Int. J. Cardiol. Hypertens.6, 100045 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Oh TJ, Moon JH, Choi SH, et al. Body-weight fluctuation and incident diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and mortality: A 16-year prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019;104:639–646. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anastasiou CA, Yannakoulia M, Pirogianni V, et al. Fitness and weight cycling in relation to body fat and insulin sensitivity in normal-weight young women. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010;110:280–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chin YR, So ES. The effects of weight fluctuation on the components of metabolic syndrome: A 16-year prospective cohort study in South Korea. Arch. Public Health. 2021;79:21. doi: 10.1186/s13690-021-00539-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sponholtz, T. R., van den Heuvel, E. R., Xanthakis, V., Vasan, R. S. Association of variability in body mass index and metabolic health with cardiometabolic disease risk. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e010793 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Turicchi, J., O'Driscoll, R., Horgan, G., Duarte, C., Santos, I., Encantado, J., Palmeira, A.L., Larsen, S.C., Olsen, J.K., Heitmann, B.L. et al. Body weight variability is not associated with changes in risk factors for cardiometabolic disease. Int. J. Cardiol. Hypertens.6, 100045 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Aucott, L. S., Philip, S., Avenell, A., Afolabi, E., Sattar, N., Wild, S. Patterns of weight change after the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in Scotland and their relationship with glycaemic control, mortality and cardiovascular outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open6, e010836 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Zoppini, G., Verlato, G., Targher, G., Bonora, E., Trombetta, M., Muggeo, M. Variability of body weight, pulse pressure and glycaemia strongly predict total mortality in elderly type 2 diabetic patients. The Verona Diabetes Study. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev.24, 624–628 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Montani JP, Schutz Y, Dulloo AG. Dieting and weight cycling as risk factors for cardiometabolic diseases: Who is really at risk? Obes. Rev. 2015;16(Suppl 1):7–18. doi: 10.1111/obr.12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, Anstee QM, Targher G, Romero-Gomez M, Zelber-Sagi S, Wai-Sun Wong V, Dufour JF, Schattenberg JM, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J. Hepatol. 2020;73(1):202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanyal AJ, American GA. AGA technical review on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1705–1725. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.