Abstract

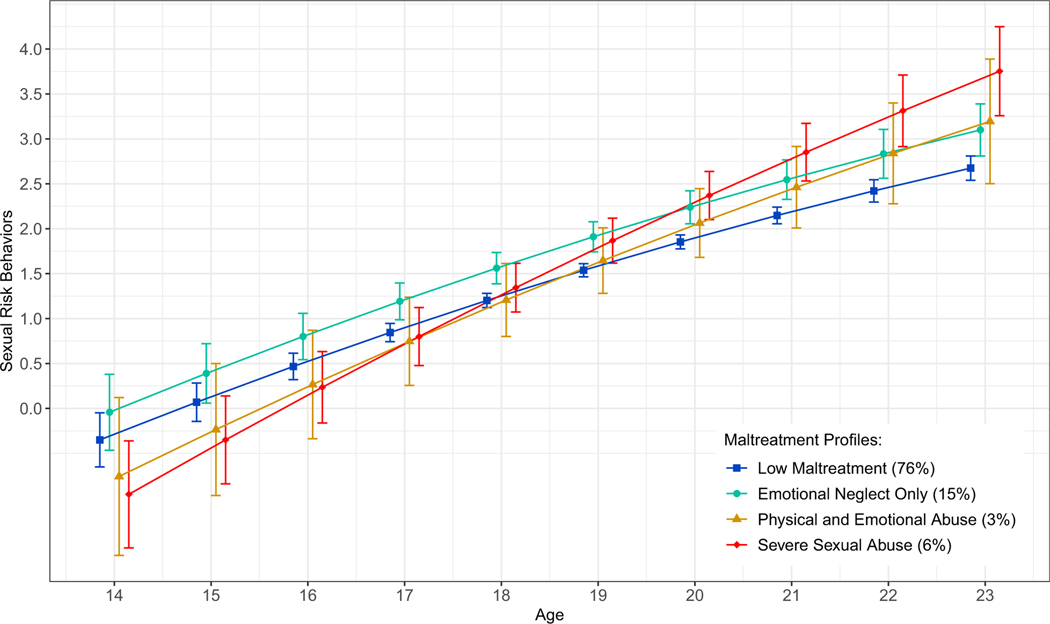

This study examines associations between childhood maltreatment and developmental trajectories of sexual risk behaviors (SRBs) in a sample of 882 sexually active adolescent girls, predominantly Hispanic or Black, assessed every 6 months between 13 and 23 years. Latent profile analyses revealed four distinct maltreatment profiles: Low Maltreatment (76%), Moderate Emotional Neglect Only (15%), Severe Physical/Emotional Abuse (3%), and Severe Sexual Abuse (6%). Multilevel growth analyses showed the Moderate Emotional Neglect Only and Severe Sexual Abuse profiles exhibited more SRBs starting in late adolescence, and the Severe Sexual Abuse profile also exhibited a faster increase than the Low Maltreatment profile. Understanding heterogeneity within maltreated populations may have important implications for healthy sexual development.

Adolescence and young adulthood are key periods of sexual development (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Typically starting around the high school years (ages 13–18 years), many youth become sexually active and may engage in sexual risk behaviors (SRBs) such as infrequent condom use or having multiple partners (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2017). SRBs may have profound health consequences, particularly for racial/ethnic minority girls with less access to healthcare and disruptive socioeconomic factors. Black and Hispanic girls are disproportionately affected by sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and teen pregnancy. For example, Black girls were 3.2 times as likely to test positive for STIs and 1.4 times as likely to have a teen birth compared to White girls; similarly, Hispanic girls were twice as likely to acquire chlamydia and gonorrhea, and 1.6 times as likely to have a teen birth as White girls (Forhan et al., 2009; Pflieger, Cook, Niccolai, & Connell, 2013). These significant racial/ethnic disparities highlight the vital need to understand sexual risk trajectories among girls of color and identify at-risk groups that would benefit from targeted interventions.

Childhood maltreatment is a risk factor for adverse psychological and sexual behaviors (Norman et al., 2012; Trickett, Negriff, Ji, & Peckins, 2011). Approximately, nine out of every 1,000 children had a documented incident of child maltreatment in 2017, with rates three times higher among low-income families and 1.6 times higher in Black children than population averages (Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner, & Hamby, 2014; United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). When unsubstantiated and unreported maltreatment were counted, 38.1% of adolescents aged 14–17 years in the United States reported experiencing child maltreatment in their lifetime (Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, & Hamby, 2015). In a study among urban racial/ethnic minority female adolescents aged 12–20 years (the same sample used in the current study), Diaz et al. (2020) found that 59.6% of girls reported childhood maltreatment. Research has generally supported associations between childhood maltreatment and SRB during adolescence and young adulthood (Senn & Carey, 2010); however, most studies to date only examined individual types of abuse or neglect despite common co-occurrence of different types of maltreatment (Hahm, Lee, Ozonoff, & Van Wert, 2010). Additionally, most studies that have examined links between childhood maltreatment and SRBs have analyzed sexual acts at a single time point or relied on specific SRB such as condom use or number of sexual partners (Haydon, Hussey, & Halpern, 2011; Ryan, Mendle, & Markowitz, 2015; Thibodeau, Lavoie, Hébert, & Blais, 2017). This has limited our knowledge about how maltreatment experiences contribute to developmental trajectories of SRBs. This study aims to address these gaps by exploring profiles of maltreatment experiences regarding types, frequency, and co-occurrence and examining the association between childhood maltreatment and subsequent trajectories of more comprehensively measured SRBs. This study seeks to understand how differences in maltreatment profiles predict developmental changes in adolescent girls’ sexual risk-taking behaviors.

Theoretical Pathways Linking Childhood Maltreatment to SRB

There are several biological and psychological theories proposed to explain why childhood abuse and neglect may increase risks for SRBs in adolescence. Biological theories suggest that early maltreatment exposure disrupts the functioning of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis releases a cascade of hormones in response to stress that culminates in the release of cortisol (McEwen, 1998), which then suppresses the activity of the axis to return to baseline functioning. While this process is adaptive in the short term, chronic or repeated activation of the HPA axis (i.e., in the case of maltreated youth), may cause permanent changes to the stress-response system including elevated basal cortisol levels as well as blunted cortisol reactivity to future stressors (Koss & Gunnar, 2018; Trickett, Noll, & Putnam, 2011). HPA dysregulation can undermine memory performance, decision-making, self-regulation, and coping behaviors (Lupien, Maheu, Tu, Fiocco, & Schramek, 2007; McEwen, 1998), all of which are important for navigating intimate and sexual relationships during adolescence. Another biological theory suggests that the dysfunction of the HPA axis may interact with the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis to accelerate pubertal maturation in girls, which is an independent risk factor for early sexual initiation and sexual risk-taking (Ryan et al., 2015; Trickett & Putnam, 1993). Research suggests that increased androgenic hormones associated with pubertal maturation are associated with increased sexual interest and motivation in early maturers (Negriff, Susman, & Trickett, 2011; Udry, 1988).

Psychosocial theories explaining the link between childhood maltreatment and adolescent SRBs focus on the psychological responses to childhood maltreatment exposure. The traumagenics dynamics model (Finkelhor & Browne, 1985) posits that extreme childhood maltreatment can lead to psychological disruptions such as traumatic sexualization, which increase risky sexual behaviors during adolescence and adulthood. Similarly, the self-trauma model (Briere, 1996) suggests that childhood maltreatment leads to adjustment difficulties through attachment problems, symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, maladaptive coping strategies, and negative appraisals of oneself and others, with several critical implications for adolescent intimate and sexual relationships. First, maltreated girls are more likely to suffer from low self-efficacy and a sense of powerlessness when making decisions in romantic and sexual relationships (Wolfe, Wekerle, Scott, Straatman, & Grasley, 2004). This power imbalance between maltreated girls and their sexual partners may increase the risk of unwanted and unsafe sex (Jones et al., 2010). Additionally, maltreated girls, and sexually abused girls in particular, are more preoccupied with sex (e.g., sexual thoughts and consumption of sexually explicit materials) and often begin sexual relationships at a younger age compared to non-maltreated girls, increasing their likelihood of engaging in risky sexual behaviors (Noll, Haralson, Butler, & Shenk, 2011).

Together, these biological and psychosocial theories provide researchers with a useful framework for understanding the behavioral sequelae following exposure to childhood maltreatment. As maltreated children confront a progression of developmental tasks across adolescence and young adulthood (e.g., formation of secure relationships, autonomy, peer relationships, and intimate relationships), maladaptive biological and psychosocial functioning formed early in development may negatively impact social relationship patterns that are formed during adolescence and continue into adulthood (Trickett, Negriff, et al., 2011). Racial/ethnic minority and low-income youth, who experience maltreatment, may face additional challenges during adolescence such as financial strains, exposure to neighborhood poverty and violence, and perceived discrimination that further increase their vulnerability for adverse outcomes.

Multiple Types of Childhood Maltreatment

Child maltreatment occurs in various ways, often categorized as sexual, physical, emotional (or psychological) abuse, and neglect (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). According to the United States Department of Health and Human Services (2019), the most frequently reported types of child maltreatment in the United States are incidents of neglect (physical and/or emotional), followed by physical abuse, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse. Growing evidence shows that various types of maltreatment most often co-occur (Finkelhor, Turner, Hamby, & Ormrod, 2011). Finkelhor, Ormrod, and Turner (2009) found in a nationally representative study of children aged 2–17 in the United States that children experienced in their lifetime an average of 3.7 types of victimization out of 33 (e.g., sexual abuse, physical abuse, witnessing interparental violence). Another study using case record abstraction found that 65.3% of maltreated youth experienced multiple types of maltreatment (Kim, Mennen, & Trickett, 2017).

Some researchers theorize that multiple types of maltreatment would predict worse developmental outcomes than any single type because the cumulative risk of childhood adversity and trauma may cause more profound cognitive and biological changes (Felitti et al., 1998). Others prioritize the specific constellation of maltreatment types (rather than viewing all maltreatment types as equally impactful), since certain maltreatment types may work in synergy to magnify impacts on developmental outcomes (Hahm et al., 2010; Trickett, 1998). For example, Hahm et al. (2010) examined all possible combinations of subtype co-occurrence in a nationally representative sample, finding that female young adults who had experienced childhood sexual abuse plus other maltreatment types had the poorest risk behavior outcomes, compared to those who had experienced only sexual abuse or physical abuse and neglect combined.

Several recent studies have used cluster analysis or latent profile (LP) analysis to empirically identify groups of children who share similar maltreatment experiences, instead of imposing a predefined classification scheme that may or may not fit a given sample (Armour, Elklit, & Christoffersen, 2014; Hazen, Connelly, Roesch, Hough, & Landsverk, 2009; Nooner et al., 2010; Warmingham, Handley, Rogosch, Manly, & Cicchetti, 2018). Trickett, Kim, and Prindle (2011) examined the patterns of multiple types of maltreatment using cluster analysis, finding four clusters of child maltreatment experiences that were differentially associated with mental, behavioral, and cognitive outcomes. In 795 12-year-old adolescents from the Longitudinal Studies on Child Abuse and Neglect (LONGSCAN), Nooner et al. (2010) conducted LP analysis and identified four profiles of youth: no physical or sexual abuse (85%), high physical and low sexual abuse (6%), no physical abuse and moderate sexual abuse (6%), and high physical and sexual abuse (3%). However, this study did not examine emotional types of abuse and neglect. In a study of 2,980 Danish emerging adults, Armour et al. (2014) identified four profiles of youth: non-abused (86.2%), emotionally abused only (9.7%), co-occurring physical, sexual and emotional maltreatment (2.1%), and sexually abused only (2.0%). In another study of 674 low-income urban children aged 10–12 years in the United States, Warmingham et al. (2018) identified four profiles of youth: non-maltreated (48%), neglect only (16%), multiple subtypes (physical, emotional and sexual abuse; 30%), and single subtypes (6%). These studies demonstrate meaningful constellations of maltreatment types, yet whether specific constellations of prior maltreatment have long-term consequences that persist across the transition from adolescence to young adulthood remains understudied.

Childhood Maltreatment and Trajectories of SRBs

Most adolescents become sexually active around the high school years, and by late adolescence and young adulthood, many develop patterns of SRB that set a negative trajectory for poor sexual health into adulthood (Fergus, Zimmerman, & Caldwell, 2007; Lalor & McElvaney, 2010). Studies have shown that adolescents with a history of abuse and neglect are more prone to sexual risk-taking during adolescence and young adulthood (Hahm et al., 2010; Haydon et al., 2011; London, Quinn, Scheidell, Frueh, & Khan, 2017; Noll et al., 2011). Most literature has focused on the effects of sexual abuse, yielding robust evidence for associations between childhood sexual abuse and specific SRB during adolescence and young adulthood, such as early sexual initiation, unprotected sex, sex trade involvement, multiple sexual partners, teen pregnancy, and STIs (Buffardi, Thomas, Holmes, & Manhart, 2008; Haydon et al., 2011; Senn & Carey, 2010). Physical and emotional abuse and neglect are associated with early initiation of sexual intercourse and more sexual partners in some studies (Black et al., 2009; Negriff, Schneiderman, & Trickett, 2015; Ryan et al., 2015), but not others (Buffardi et al., 2008; Haydon et al., 2011).

Despite the burgeoning literature, most prior studies examining associations between childhood maltreatment and adolescent SRBs have analyzed sexual behaviors at a single time point later in life. Such study design captures only a snapshot of SRBs sometime during adolescence or young adulthood and are insufficient for understanding the extent to which potentially co-occurring child maltreatment experiences predispose youth towards trajectories of increasing SRB. The developmental literature on antisocial behavior (Moffitt, 1993) and sexual behavior (Zimmer-Gembeck & Helfand, 2008) has distinguished two patterns of risk behaviors: “normative risk-taking” that is adolescent limited (i.e., characterized by a steady increase during adolescence, peaking at a certain age and then decreasing) and “risky deviance” that tends to persist into adulthood (i.e., characterized by early onset of risk factors and persistent problems). Most often, SRB increases at the stage of exploration and changing relationships and then decreases as young adults develop longer-term and more committed relationships. For example, SRB was found to follow an inverted U-shaped curve, increasing across adolescence and then decelerating in early adulthood (Brodbeck, Bachmann, Croudace, & Brown, 2013; Fergus et al., 2007). However, some maltreated youth with maladaptive functioning in psychosocial and biological domains may show inadequate resolution of developmental challenges, and engage in SRBs that continue to increase throughout adolescence and young adulthood (London et al., 2017; Senn & Carey, 2010).

Another key limitation of past research involves relying on sexual behaviors that are part of the normative process of adolescent sexuality such as sexual intercourse, condom use, or number of sexual partners (Fergus et al., 2007; Ryan et al., 2015; Thibodeau et al., 2017; Wilson, Samuelson, Staudenmeyer, & Widom, 2015). These behaviors may not fully capture the risk experienced by maltreated girls, particularly those from low-income families, who often face various stressful life circumstances that increase high-risk sexual behaviors such as having sex while under the influence of drugs or alcohol, having sex with a partner known to have an STI, having an older sex partner (e.g., 5 years older than the adolescent girl), or even engaging in sex trade in exchange for money, shelter, or drugs (Lalor & McElvaney, 2010; Naramore, Bright, Epps, & Hardt, 2017). It is thus crucial to examine adolescent SRBs that included a comprehensive set of both moderate and high-risk sexual behaviors to better understand the behavioral risk sequelae of childhood maltreatment among vulnerable populations.

The Current Study

Drawing on data from a longitudinal study of sexually active adolescent girls of color, this study identifies maltreatment profiles based on the frequency and co-occurrence of self-reported childhood maltreatment experiences and examines how different maltreatment profiles predict developmental trajectories of adolescent SRBs. Based on the research to date, it was expected that at least four profiles of youth would be identified: low or no maltreatment, neglect only, sexual abuse primary, and physical and emotional abuse primary. Based on studies that have linked child sexual abuse to SRBs, it was expected that youth with the sexual abuse primary profile would report the greatest SRBs during adolescence among all profiles, with the low maltreatment profile reporting the least SRBs.

Method

Participants

This study consisted of 1,199 sexually active female participants enrolled in an ongoing human papillomavirus (HPV) surveillance study at a large urban adolescent health clinic. Females were eligible to participate in the original HPV study if they (a) were between 13 and 21 years of age at the time of their first study visit, (b) had ever engaged in vaginal intercourse, and (c) intended to get or had already received an FDA approved HPV vaccine (GARDASIL®, Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ). Participants were recruited on a rolling basis from 2007 to 2016. Written informed consent was collected from all participants before enrollment, with a waiver of parental consent for adolescents 13–17 years. Participants were followed every 6 months up to ages 25. During each study visit at the clinic, participants received a comprehensive gynecological examination from a clinician that included sexual, reproductive and psychosocial history, immunization update, and STI screening. Participants also completed self-administered questionnaires assessing demographic characteristics, maltreatment history, and psychosocial functioning in a private office space. A study visit took about one to 1.5 hr to complete. As an incentive to participation, participants received two movie tickets, a roundtrip MetroCard, and a $25 gift card per visit. A full description of the study design has been published previously (Braun-Courville et al., 2014). The original HPV study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and the current study was approved by the IRB at Fordham University.

The analytic sample included 882 youth who were administered the childhood maltreatment questionnaire, which was first introduced in March 2013. The study is an ongoing study and participants can complete a follow-up visit every 6 months until they aged out at age 25. As a result, participants had varying numbers of study visits, ranging from 1 to 18, with an average of 7.3 (SD = 4.05) visits. The current analysis was restricted to a total of 3,518 observations from the first five visits (i.e., baseline, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months), as the original aim of the study involved following up the participants for 2 years and so that our analysis was not heavily weighted by participants with a large number of study visits. Among the participants, the completion rate of follow-up assessment was 73.7% (n = 650) at 6 months, 73.5% (n = 648) at 12 months, 71.8% (n = 633) at 18 months, and 79.9% (n = 705) at 24 months. Compared to participants who completed all five study visits (n = 410, 46.5%), participants who completed less than five visits (n = 472, 53.5%) were more likely to have parents who received public assistance (χ2(1) = 8.74, p = .003), and reported fewer SRB (χ2(1) = 3.64, p = .057).

Measures

Childhood Maltreatment

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), a widely used 28-item self-report questionnaire was used to assess for history of childhood maltreatment in adolescents (Bernstein et al., 2003; Heany et al., 2018). Studies using both clinical and non-clinical samples have supported the reliability and validity of maltreatment history obtained using the CTQ (Bernstein et al., 2003). It has also been shown to have a high correlation with data from child welfare agencies (Bernstein, Ahluvalia, Pogge, & Handelsman, 1997). At the baseline visit, participants were asked to respond to five statements for each type of abuse and neglect (e.g., sexual abuse: “Someone tried to touch me in a sexual way, or tried to make me touch them”; physical abuse: “People in my family hit me so hard that it left me with bruises or marks”; emotional abuse: “I felt that someone in my family hated me”; physical neglect: “I didn’t have enough to eat”; and emotional neglect: “People in my family felt close to each other,” reversed coded). Participants rated the frequency each maltreatment statement occurred when they “were growing up” on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (very often true). Frequency scores for each maltreatment type were calculated by summing responses to the five corresponding items. The scale also included a three-item minimization/denial scale for detecting false-negative childhood maltreatment reports. The internal reliability was high for sexual, physical, and emotional abuse and emotional neglect (αs ranged from .81 to .92) and low for physical neglect (α = .55).

Sexual Risk Behaviors

At each study visit, participants reported their past sexual activities and behaviors as part of a clinical interview. Questions include the following: (a) ever had sex in return for money, drugs, shelter, or food (1 = yes; 0 = no); (b) ever been under the influence of drugs or alcohol and might have had sex but not remember it (1 = yes; 0 = no); (c) ever had sex with someone known to be infected with an STI (1 = yes; 0 = no); (d) ever had sexual partners 5 years or older than you (1 = yes; 0 = no); and (e) whether or not ever used condom during vaginal sex (1 = yes; 0 = no). Participants also reported the number of lifetime sexual partners (male and female) and responses were coded as 1 = five or more and 0 = less than five. A composite score was created based on the sum of these six items at each visit (range 0–6), with a higher score reflecting an increased number of SRBs participants had ever engaged in by each visit date. This cumulative sum approach was consistent with the operationalization of SRB in prior research (Henrich, Brookmeyer, Shrier, & Shahar, 2006; Negriff & Valente, 2018; Raffaelli & Crockett, 2003), and allowed us to understand age-related increase in the total number of risky sexual behaviors individuals engaged in. To address the possibility that the same behavior was reported at each time point, we set the endorsement of each item score to carry over visits such that it was automatically counted as an endorsement at subsequent visits. For example, if a participant at Visit 1 endorsed no SRB, at Visit 2 endorsed only not having used a condom, at Visit 3 endorsed only having had sex in return for money, and at Visits 4 and 5 endorsed no additional risks, she will be coded as 0 at Visit 1, 1 at Visit 2, and 2 at Visits 3–5.

Covariates

Demographic characteristics were assessed at baseline via self-reported race/ethnicity (mutually exclusive categories of non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic Black, non-Black Hispanic, or non-Hispanic other including White, Asian, Native American, and other), nativity status (1 = born in the United States; 0 = not), parent receipt of public assistance such as welfare checks and Medicaid/Medicare, parent(s) living status (mutually exclusive categories of lived together, separated, or deceased), and whether the participant currently attended school. Adolescent body mass index (BMI) calculated from clinician-measured weight and height, and self-reported history of depression and age at menarche were also included as covariates due to their correlations with SRB (Belsky, Steinberg, Houts, & Halpern-Felsher, 2010; Linares et al., 2015). To address underreporting of childhood trauma experiences, a minimization/denial variable was included as a covariate (coded as 1 if participants reported that they strongly agreed with any of the three items: “There was nothing I wanted to change in my family”; “I had the perfect childhood”; and “I had the best family in the world”). Finally, to account for potential intervention effects of clinic service utilization on participants’ SRB, the total number of study visits from enrollment until 2016 was controlled in all analyses.

Statistical Analysis

First, LP analyses were conducted to empirically identify maltreatment profiles based on similar response patterns to questions regarding experiences of sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect (Collins & Lanza, 2013). A set of models was fitted sequentially estimating two to five profiles. The best-fitting model was chosen based on interpretability regarding the theory and literature as well as multiple fit statistics, including Bayesian information criterion (BIC), Akaike information criterion (AIC), log-likelihood test, and entropy (Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007). Specifically, smaller absolute values of BIC, AIC, and log-likelihood indicate better model fit; a significant log-likelihood test p value suggests that the k profile model fits better than the k − 1 profile model; and an entropy value closer to 1 (range from 0 to 1) indicates clearer classification between LPs (Nylund et al., 2007). After identifying the best-fitting model, individuals were assigned to a profile based on their most likely LP membership. We labeled the resulting profiles by evaluating profile average maltreatment exposure (see Figure 1) against the cut points for none to low, moderate, and severe maltreatment according to the CTQ scoring manual: sexual abuse (≤ 7, 8–12, ≥ 13); physical abuse (≤ 9, 10–12, ≥ 13); emotional abuse (≤ 12, 13–15, ≥ 16); physical neglect (≤ 9, 10–12, ≥ 13); and emotional neglect (≤ 14, 15–17, ≥ 18), respectively (Bernstein et al., 2003). To better characterize each profile, we ran a series of analysis of variance and chi-square tests to examine sociodemographic differences across profiles.

Figure 1.

Profiles of childhood maltreatment in average abuse and neglect exposure. Y-axis shows the average scores of sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, and emotional neglect (possible range = 5–25). Cut points for none-to-low (L), moderate (M), and severe (S) were applied to facilitate interpretation according to the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire scoring manual (Bernstein et al., 2003): sexual abuse (≤7, 8–12, ≥13); physical abuse (≤9, 10–12, ≥13); emotional abuse (≤12, 13–15, ≥16); physical neglect (≤9, 10–12, ≥13); and emotional neglect (≤14, 15–17, ≥18), respectively.

Second, multilevel growth curve models were conducted to estimate the effect of maltreatment profiles on trajectories of SRB. Multilevel curve modeling is appropriate given the hierarchical structure of the data: time (i.e., Level 1) nested within adolescents (i.e., Level 2). This approach allowed for estimation of individual variability in the intercept (i.e., the average number of SRBs) and the slope (i.e., the change of SRB over time). Age served as the time variable to estimate developmental changes in SRB. The possible age range during the study period was through 23 years, truncated to 14 through 23 years to avoid potential bias introduced by very small frequencies of specific age groups (2 participants were 13 years and thus combined with the years group). Age was centered at 19 years, the mean age over the study period so that the intercept reflected the number of SRBs at 19 years. A series of growth models were estimated as follows:

Model 1: Unconditional Growth Model

Model 2: Conditional Growth Model

Model 3: Fully Adjusted Growth Model

First, we fit an unconditional growth model (Model 1) to estimate the fixed intercept (b0i, the average SRB at age 19) and fixed linear age (b1i, the rate of change in SRB per year), as well as to evaluate the random intercept (μ0j) and random slope (μ1j) to ensure significant individual variability in the intercept and the slope. We also compared Model 1 against an unconditional quadratic growth model using log-likelihood ratio test to determine the best functional form of change (e.g., intercept, linear, curvilinear) in SRB to be used in subsequent models. Next, we estimated a conditional growth model (Model 2), in which the LP membership, coded as dummy variables with the lowest risk profile as the reference group, were added to predict variations in the intercept and slope estimates of SRB. LP effects (b2i) tested whether a certain LP had significantly different average SRB at age 19 compared to the lowest risk profile. The Age × LP interaction effects (b3i) tested whether a certain LP had significantly different rate of change compared to the lowest risk profile. Finally, we examined the fully adjusted growth model (Model 3), adding covariates (adolescent demographics characteristics, depression, age at menarche, BMI, CTQ minimization/denial, and total number of visits) to the conditional growth model. We examined whether each maltreatment profile, compared to the lowest risk profile, was associated with greater SRBs at age 19 (b2i) and a faster increase over time (b3i), after accounting for potential confounds.

Comparing each profile against the lowest risk profile tests the hypothesis that the low maltreatment profile reported the lowest SRB; we reiterated the fully adjusted model rotating the reference group to test all possible comparisons between profiles (e.g., to test the hypothesis that sexual abuse primary profile reported the greatest SRB). In each iteration, we further conducted post-hoc analyses to first estimate the predicted SRB (and 95% CI) at each age point, and then test the significance of profile differences in the intercept (at each age) and slope (Klein, 2018), to allow profile comparisons across the full age range (vs. only at age 19). We adopted a more a conservative p value (p < .01) to interpret significant profile differences, to adjust for multiple comparisons.

All analyses were conducted in Stata 15.0 (Stata-Corp, 2017). All continuous covariates were grandmean centered before analysis to facilitate interpretation (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). Consistent with recommendations, all models were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood and an unstructured covariance matrix (Molenberghs & Kenward, 2007). As the dependent variable was approximately normally distributed, a Gaussian distribution was specified. All 882 participants with baseline data were included in the analyses as multilevel growth modeling can make use of all available data in the estimation of model parameters. Missing values on the outcome variable and covariates (ranging from 0.01% on age at menarche to 3.75% on self-reported history of depression) were assigned using chained multiple imputation methods (Royston & White, 2011). All independent variables and non-missing covariates were used as predictors in the imputation process using the mi impute command. Ten complete data sets were imputed to help ensure stable parameter estimates. In the estimation and pooling step, analyses were performed separately on each imputed data set and the results were then combined into a single multiple-imputation result using the mi estimate command.

Finally, we ran two sets of sensitivity analyses. First, to address concerns of low reliability of the physical neglect subscale, we excluded physical neglect from the LP analysis to examine whether similar maltreatment profiles, as well as similar associations with sexual risk trajectories, were found. Second, we conducted additional analyses using the number of lifetime sexual partners and frequency of condom use as alternative outcome measures, given that they have been examined in the literature as single indicators of SRB (Choukas-Bradley, Giletta, Widman, Cohen, & Prinstein, 2014; Pingel et al., 2012; Ryan et al., 2015; Thibodeau et al., 2017) and were the two most prevalent SRBs measured in our sample.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 describes the distribution of baseline childhood maltreatment and demographic characteristics as well as SRB over the study period. The majority of the participants were from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds (36.4% non-Hispanic Black, 13.5% Hispanic Black, 45.0% non-Black Hispanic, and 4.9% other). Most participants were born in the United States (89.8%), were attending school (86.0%), and had parents who received public assistance (65.1%). Participants reported an average of 1.15 (SD = 0.95) out of six SRBs at baseline, with the most frequent SRB being no condom use (47.9%), followed by having had five or more lifetime partners (41.7%), and having had a partner 5 years or older (27.3%). Over the study period, the mean age of the participants was 19.21 years (SD = 1.62). The average number of SRBs over the study period was 1.67 (SD = 1.07).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at Baseline

| At baseline (N = 882) | M (SD)/% |

|---|---|

| Age in years | 18.16 (1.38) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 36.4% |

| Hispanic Black | 13.5% |

| Non-Black Hispanic | 45.0% |

| Non-Hispanic other | 4.9% |

| Born in the United States | 89.8% |

| Parent received public assistance | 65.1% |

| Food insecurity | 6.8% |

| Parent living status | |

| Living together | 21.0% |

| Separated | 71.9% |

| Parent(s) deceased | 5.4% |

| Attend school | 86.0% |

| History of depression | 15.9% |

| Age at menarche in years | 11.76 (1.54) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.80 (6.27) |

| Number of study visits | 7.30 (4.05) |

| Childhood maltreatment subscales | |

| Sexual abuse | 6.29 (3.65) |

| Physical abuse | 6.56 (3.05) |

| Emotional abuse | 7.81 (3.99) |

| Physical neglect | 6.71 (2.64) |

| Emotional neglect | 9.65 (4.67) |

| Sexual risk behavior (range 0–6) | 1.15 (0.95) |

| Ever had sex in return for money? | 0.9% |

| Ever drunk while having sex? | 1.5% |

| Ever had sex with someone known to be | 0.5% |

| infected with a sexually transmitted disease? | |

| Had five or more lifetime partners | 41.7% |

| Had a partner 5 years or older | 27.3% |

| No current condom use | 47.9% |

Note. Non-Hispanic other included White (n = 11), Asian (n = 16), Indian American/Native American (n = 3), and other (n = 13).

Research Question 1: What Are Profiles of Childhood Maltreatment?

LP analyses were conducted to examine maltreatment profiles based on three types of abuse (sexual, physical, and emotional) and two types of neglect (physical and emotional). As shown in Table 2, BIC, AIC, and log-likelihood decreased from the two-profile solution to the four-profile solution and remained relatively unchanged for the five-profile solution, indicating improved model fit until the four-profile solution. Log-likelihood ratio tests showed that the three-profile solution fitted the data better than the two-profile solution, and the four-profile solution better than the three-profile solution; however, the five-profile solution did not fit the data better than the four-profile solution. The entropy values of the two-profile, three-profile, and four-profile solutions were all above 0.80, which is considered a desirable entropy value (Collins & Lanza, 2013). Based on the above fit statistics and that the profiles from the four-profile solution generally converged with previous research (Armour et al., 2014; Nooner et al., 2010; Warmingham et al., 2018), the four-profile solution was chosen as the optimal solution.

Table 2.

Fit Statistics From Latent Profile Analysis of Childhood Maltreatment (N = 882)

| Model | Log-likelihood | df | p value | AIC | BIC | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Profiles | −11,023.1 | 16 | — | 22,078.2 | 22,154.7 | 0.97 |

| 3 Profiles | −10,657.9 | 22 | < .001 | 21,359.8 | 21,465.0 | 0.91 |

| 4 Profiles | −10,445.9 | 28 | < .001 | 20,947.9 | 21,081.8 | 0.89 |

| 5 Profiles | −10,445.9 | 34 | ns | 20,959.9 | 21,122.5 | 0.37 |

Note. p values were based on log-likelihood ratio test. BIC = Bayesian information criterion; AIC = Akaike information criterion; Entropy = entropy of classification model.

Figure 1 shows the average abuse and neglect of the four identified profiles. The first profile of girls (76%) had none or low maltreatment on all types, labeled as Low Maltreatment. A second profile (15%) had moderate emotional neglect, and none or low on all other types of abuse and neglect, labeled as Moderate Emotional Neglect Only. A third profile (3%) had severe physical and emotional abuse, as well as moderate sexual abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect, labeled as Severe Physical/Emotional Abuse. The last profile (6%) had severe sexual abuse, moderate physical and emotional abuse, as well as none or low physical and emotional neglect, labeled as Severe Sexual Abuse. Table 3 presents the profile differences in adolescent sociodemographic characteristics. The Low Maltreatment profile had the lowest frequency of participants who had parents on public assistance (61.8%) and reported household food insecurity (3.8%), significantly lower than the other three maltreatment profiles, ps < .01.

Table 3.

Adolescent Sociodemographic Characteristics by Maltreatment Profiles

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Low maltreatment (76%) | Moderate emotional neglect only (15%) | Severe physical/emotional abuse (3%) | Severe sexual abuse (6%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18.20 (1.38) | 17.94 (1.41) | 18.23 (1.31) | 18.19 (1.32) | .26 |

| Race/ethnicity | .31 | ||||

| NH Black | 35.2% | 44.4% | 30.8% | 34.5% | |

| Hispanic Black | 13.5% | 13.5% | 11.5% | 14.5% | |

| NB Hispanic | 46.6% | 36.1% | 57.7.9% | 41.8% | |

| NH Other | 4.5% | 6.0% | 0.0% | 9.1% | |

| Born in the United States | 90.4% | 88.7% | 96.2% | 81.8% | .14 |

| Parent received public assistance | 61.8%a | 74.5%b | 88.9%b | 75.6%b | .003 |

| Food insecurity | 3.8%a | 15.2%b | 11.5%b | 21.8%c | < .001 |

| Parent living status | .62 | ||||

| Lived together | 22.2% | 19.5% | 7.7% | 16.4% | |

| Separated | 71.1% | 73.7% | 76.9.4% | 74.5% | |

| Parent(s) deceased | 5.4% | 4.5% | 7.7% | 7.3% | |

| Attend school | 87.7% | 80.5% | 80.0% | 81.8% | .09 |

Note. Group differences were tested using chi-square test of independence for categorical variables or analysis of variance for continuous variables. Tukey’s post-hoc comparisons were conducted if p < .05. Means with different subscripts within a column are significantly different at p < .05. p values were based on complete case analysis. NH = non-Hispanic, NB = non-Black.

Research Question 2: Do Maltreatment Profiles Predict Adolescent SRB?

Results from the unconditional growth model (Table 4, Model 1) indicated at age 19 girls engaged in 1.61 SRB on average, which differs significantly from zero (p < .001). There was a significant linear and quadratic increase in SRBs from age 14 to 23 years, indicating that on average girls reported 0.35 (p < .001) more SRB per year, but the growth decelerated over time. A log-likelihood ratio test was conducted to compare Model 1 with a model without the quadratic age term. Results suggested that the quadratic functional form was a better fit for these data, thus used in subsequent models.

Table 4.

Estimates From Multilevel Growth Models for Sexual Risk Behaviors

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Predictors | b | SE | β | b | SE | β | b | SE | β |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||

| Intercept at 19 years | 1.61*** | .03 | −.34 | 1.52*** | .04 | −.42 | 1.32*** | .13 | −.53 |

| Linear age | 0.35*** | .01 | .31 | 0.33*** | .01 | .30 | 0.33*** | .01 | .29 |

| Quadratic age | −0.01* | .00 | −.01 | −0.01* | .00 | −.01 | −0.01* | .00 | −.01 |

| Maltreatment classes (ref. = low maltreatment) | |||||||||

| Moderate emotional neglect only | 0.43*** | .09 | .39 | 0.37*** | .09 | .33 | |||

| Severe physical/emotional abuse | 0.16 | .19 | .15 | 0.11 | .19 | .10 | |||

| Severe sexual abuse | 0.39** | .14 | .34 | 0.33** | .13 | .29 | |||

| Interaction effects (ref. = low maltreatment) | |||||||||

| Age × Moderate Emotional Neglect Only | 0.01 | .03 | .01 | 0.01 | .03 | .01 | |||

| Age × Severe Physical/Emotional Abuse | 0.10 | .07 | .08 | 0.10 | .07 | .08 | |||

| Age × Severe Sexual Abuse | 0.19*** | .05 | .17 | 0.19*** | .05 | .17 | |||

| Race/ethnicity (ref. = NB Hispanic) | |||||||||

| NH Black versus NB Hispanic | −0.07 | .07 | −.06 | ||||||

| Hispanic Black versus NB Hispanic | 0.06 | .10 | .05 | ||||||

| NH other versus NB Hispanic | −0.04 | .16 | −.15 | ||||||

| Born in the United States | 0.16 | .11 | .13 | ||||||

| Parent received public assistance | 0.10 | .07 | .08 | ||||||

| Food insecurity | −0.09 | .13 | −.07 | ||||||

| Parent living status (ref. = lived together) | |||||||||

| Separated | 0.10 | .08 | .08 | ||||||

| Parent(s) deceased | 0.23 | .15 | .19 | ||||||

| Attend school | −0.08** | .03 | −.08 | ||||||

| History of depression | 0.16 | .10 | .15 | ||||||

| Age at menarche | −0.11*** | .03 | −.09 | ||||||

| Body mass index | 0.06* | .02 | .05 | ||||||

| Number of study visits | 0.02 | .03 | .02 | ||||||

| CTQ denial scale | −0.15* | .07 | −.12 | ||||||

| Random effects | |||||||||

| Random intercept variance | 0.92*** | .03 | 0.91*** | .03 | 0.89*** | .02 | |||

| Random slope variance | 0.23*** | .01 | 0.23*** | .01 | 0.23*** | .02 | |||

| Random intercept and slope covariance | 0.02 | .06 | 0.01 | .06 | 0.03 | .06 | |||

| Within-person residual variance | 0.44*** | .01 | 0.44*** | .01 | 0.44*** | .01 | |||

Note. Estimates were based on the multiple-imputed data (N = 882, observations = 3,518). The quadratic age term was not significant in Model 1 and was thus removed from subsequent models. NB = non-Black; NH = non-Hispanic; CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Results from the conditional growth model (Table 4, Model 2) showed that SRB at age 19 was 0.43 unit higher in the Moderate Emotional Neglect Only profile and 0.39 unit higher in the Severe Sexual Abuse profile, compared to the Low Maltreatment profile (ps < .01). Results also revealed a significant interaction between the linear growth term and the Severe Sexual Abuse profile (b = 0.19, p < .001), suggesting a faster increase in SRBs among this profile relative to the Low Maltreatment profile. The Severe Physical/Emotional Abuse profile was not significantly different from the Low Maltreatment profile in either the intercept or the rate of change.

After adding a comprehensive set of covariates, the effects of maltreatment profiles (i.e., Moderate Emotional Neglect Only and Severe Sexual Abuse) on SRB intercept remained significant with slightly reduced magnitudes of the coefficients (Table 4, Model 3). Specifically, SRB was 0.37 unit higher in the Moderate Emotional Neglect Only profile and 0.33 unit higher in the Severe Sexual Abuse profile, compared to the Low Maltreatment profile (ps < .01). Consistent with Model 2, girls in the Severe Sexual Abuse (b = 0.19, p < .001) profile exhibited a faster increase in SRB than Low Maltreatment profile. In addition, the fully adjusted growth model revealed that girls who were currently enrolled in school (b = −0.08, p < .01), had an earlier age at menarche (b = −0.11, p < .001), and had a higher BMI (b = 0.06, p < .05) showed significantly higher SRBs, compared to girls who were not enrolled in school, had later ages at menarche, and had a lower BMI. Nativity, family socioeconomic status, parent living status, history of depression, and the number of study visits were not significantly associated with adolescent SRBs in the current model.

Figure 2 presents the estimated means and 95% CIs of SRB for the four maltreatment profiles at each age point. The Moderate Emotional Neglect Only profile showed significantly more SRBs than the Low Maltreatment profile starting at age 17 (b = 0.35, p < .001), increasing to young adulthood (b = 0.41, p < .01 at age 22 and b = 0.42, p < .05 at age 23). The Severe Sexual Abuse profile had significantly more SRBs than the Low Maltreatment profile (b = 0.33, p < .01 at age 19, increasing to b = 1.08, p < .001 at age 23). Across ages 14–23, the Moderate Emotional Neglect Only profile was not statistically different from the Severe Sexual Abuse profile, and the Severe Physical/Emotional Abuse profile was not statistically different from the other profiles. Significant profile differences were found in the slope estimates (i.e., Age × Maltreatment Profile interactions), suggesting that the Severe Sexual Abuse profile had a significantly faster increase in SRB than the Low Maltreatment and Moderate Emotional Neglect Only profiles, b = 0.19, p < .001, and b = 0.18, p < .01, respectively.

Figure 2.

Estimated sexual risk behaviors and 95% CIs across age dependent on maltreatment profiles. At each age point, coefficients are statistically different at p < .05 where CIs do not overlap. Simple slope estimates were 0.32 (Low Maltreatment), 0.33 (Emotional Neglect Only), 0.41 (Severe Physical/Emotional Abuse), and 0.51 (Severe Sexual Abuse), ps < .001. The Severe Sexual Abuse profile had significantly faster slopes than Low Maltreatment profile (b = 0.19, p < .001) and the Moderate Emotional Neglect Only profile (b = 0.18, p < .01).

Due to the low reliability of the physical neglect subscale, sensitivity analyses were conducted removing physical neglect from the estimation of the LPs and testing of associations between the maltreatment profiles and SRBs. These analyses yielded almost identical findings (see Tables S1–S3 and Figure S1). Additional analyses showed consistent findings when predicting the number of lifetime sexual partners (Table S4) while no significant effect of maltreatment profiles was found in predicting the frequency of condom use (Table S5).

Discussion

Childhood maltreatment is a complex and serious public health issue (Finkelhor et al., 2014; United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). Unpacking the underlying patterns of childhood maltreatment experiences is critical to our understanding of sexual health and health disparities across adolescence and young adulthood, and can help inform programmatic decision-making about which at-risk groups are more likely to benefit from targeted interventions. Using a large sample of sexually active adolescent girls, we identified four distinct maltreatment profiles based on retrospective reports of childhood maltreatment experiences. The majority of the sample reported experiencing Low Maltreatment (76%), followed by Moderate Emotional Neglect Only (15%), Severe Physical/Emotional Abuse (3%), and Severe Sexual Abuse (6%). Using a comprehensive assessment of SRBs longitudinally, this study indicated that girls exposed to Moderate Emotional Neglect Only and Severe Sexual Abuse profiles were at an elevated risk for SRBs relative to the Low Maltreatment profile. One profile of youth characterized by Severe Sexual Abuse also exhibited a faster growth of SRB across the developmental period of adolescence and young adulthood relative to the Low Maltreatment and Moderate Emotional Neglect Only profiles. These developmental patterns associated with maltreatment exposure were not explained by risk factors such as parental and sociodemographic characteristics, depression, BMI, and age at menarche. Our findings among an underrepresented sample of racial/ethnic minority female adolescents contribute to the understanding of sexual risk trajectories among girls of color, highlighting the critical role of childhood maltreatment profiles in subsequent sexual health risks and the need for targeted interventions to effectively address the different risks associated with these different patterns of early maltreatment experiences.

We found that the largest maltreated group, which was 15% of the sample, was classified into the Moderate Emotional Neglect Only profile. This is consistent with prior estimates showing that neglect is the most common form of child maltreatment (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). In other studies of maltreated profiles, youth who had experienced neglect only have emerged as the largest group: 16.0% of youth in a U.S. urban sample (Warmingham et al., 2018), and 20.2% of youth from a nationally representative sample of youth (Hahm et al., 2010). It is important to note that this profile reported low levels of emotional abuse, whereas prior studies have found that neglect is comorbid with emotional abuse (Kim et al., 2017; Petrenko, Friend, Garrido, Taussig, & Culhane, 2012), which may reflect that emotional abuse and neglect are complicated constructs and difficult to measure (Baker, 2009). In this study, the Moderate Emotional Neglect Only profile exhibited more SRBs compared to the Low Maltreatment profile from late adolescence to young adulthood, extending the sparse developmental literature regarding the independent effect of emotional neglect on adolescent health and well-being (Negriff et al., 2015). While most studies have used a broader conceptualization of neglect, combining physical and emotional forms (Kim et al., 2017), our study shows that they do not always co-occur, and their effects are distinct. Emotional neglect—characterized by emotional unresponsiveness, unavailability, and limited emotional interactions between parent and child—may interfere with the development of a secure attachment bond and appraisal of the self as a competent agent, precipitating the onset and risky patterns of sexual behavior during middle adolescence (Zimmer-Gembeck & Helfand, 2008). For example, girls exposed to emotional neglect are more motivated by attachment needs than by personal needs, experience psychosocial adjustment difficulties or lower self-esteem, and have immature decision-making skills, which in turn, increase their vulnerability for SRBs across adolescence (Bowlby, 1973; Taillieu, Brownridge, Sareen, & Afifi, 2016).

We found a second profile of youth (3%; Severe Physical/Emotional Abuse) characterized by severe physical and emotional abuse, as well as moderate sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and physical neglect. This profile is similar to the physical abuse group (6%) among another urban adolescent sample (Nooner et al., 2010) and the physical plus emotional maltreatment group (10%) among a sample of youth involved in services systems (Hazen et al., 2009). Girls with this profile experienced severe emotional abuse plus all other maltreatment types, which is consistent with recent conceptualizations in the trauma literature that emotional maltreatment is a core component underlying most forms of child mal treatment (Taillieu et al., 2016). Youth with this profile did not exhibit more SRBs than the Low Maltreatment profile, which contrasts with some past studies that have found significant associations between physical abuse or emotional abuse and SRB (Jones et al., 2010; Negriff et al., 2015; Thibodeau et al., 2017). However, among these studies, significant associations were found for some SRBs, but not others (e.g., physical abuse was associated with ever having had a one night stand, but not with the number of lifetime partners, contraception use, or sex under the influence of drugs; Negriff et al., 2015). Both theoretical and empirical works are needed to further understand the combined risks of emotional and physical abuse given its co-occurrence in the current study and other studies (Kim et al., 2017).

The last group of youth (6%; Severe Sexual Abuse) was characterized by severe sexual abuse plus moderate levels of emotional and physical abuse. This profile configuration is similar to the co-occurring sexual, physical, and emotional groups (2.1%) found by Warmingham et al. (2018) and the physically and sexually abused groups (3%) identified by Nooner et al. (2010) among an U.S. urban sample. Although SRB showed an overall inverted U-shaped curve from adolescence and young adulthood, which is consistent with the developmental literature (Brodbeck et al., 2013; Fergus et al., 2007), it had the fastest increase among girls in this profile. Our finding is consistent with a large body of research showing that childhood sexual abuse increases the risk for adolescent and young adult sexual risk-taking (Hahm et al., 2010; Lalor & McElvaney, 2010; Noll et al., 2011). By age 23, this profile was estimated to exhibit 1.08 more SRBs than the low maltreatment profile; such difference may appear small, but it reflects an increase from the average to one standard deviation above the average, which may tell a pediatrician that without intervention, youth in the Severe Sexual Abuse profile are likely to be among the most high-risk groups (e.g., top 15th percentile) by young adulthood. Our findings suggest there is something unique about experiences of sexual abuse that leave girls increasingly vulnerable to SRBs across the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. According to psychosocial theories of sexual abuse, sexual abuse is characterized by negative emotions including physical and cognitive exploitation and feelings of stigmatization and social isolation (Briere, 1996; Noll et al., 2011; Trickett & Putnam, 1993). According to biological theories, sexual abuse may lead to HPA dysregulation, which, in turn, inhibits the formation of cognitive, emotional, and relational skills necessary for girls to navigate the progression of developmental tasks during adolescence (Koss & Gunnar, 2018; Lupien et al., 2007; McEwen, 1998). For example, sexually abused youth may have difficulty forming trusting relationships and tend to have a lower self-concept at the stage of exploration, and while their peers are developing longer term relationships, they are more likely to form brief but abusive relationships, and acquiesce (or be coerced) to unwanted, unsafe, and risky sexual behaviors (Noll et al., 2011).

Generally, our findings reinforce numerous previous studies showing that youth are frequently exposed to abuse and neglect, with a substantial proportion being exposed to multiple types of maltreatment (Finkelhor et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2017). While the majority of youth (76%) in this sample experienced no or low maltreatment, approximately 24% of our sample were exposed to moderate or severe abuse or neglect, with two profiles experiencing two or more types of moderate or severe maltreatment. All three maltreated profiles were more likely to be identified in youth with parents who received public assistance and youth who did not have enough to eat at home, which supports research that has documented large socioeconomic disparities in child maltreatment (Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner, & Hamby, 2013).

Limitations and Future Research

The current findings should be interpreted within the study’s limitations. First, reports of childhood maltreatment were retrospective; thus, current life situations could bias youth’s recall of their childhood experiences. Although youth retrospective report of maltreatment may be more representative of exposure within community samples than case records documented by child protective services (Hovdestad, Campeau, Potter, & Tonmyr, 2015), future research needs to validate the identified maltreatment profiles using both self-reported data and official records from local jurisdictions. Second, this study only included participants who were administered the CTQ; as a result, participants with missing maltreatment data (n = 317) were exclude from the analysis. However, we did not find significant missing data patterns in regard to race/ethnicity, age, or SRB (results available upon request). Third, childhood maltreatment assessed by the CTQ did not allow an examination of the age of onset, perpetrator, or chronicity regarding the maltreatment exposure, which should be important considerations in future research on childhood maltreatment. Additionally, emotional neglect was scored by reverse coding of positive statements (e.g., “People in my family felt close to each other.”). Although studies have supported the validity of CTQ in screening for a broad dimension of childhood maltreatment (Spinhoven et al., 2014), future research needs to verify the presence of childhood maltreatment using case records or diagnostic interview measures and obtain more information about the nature and context of the maltreatment. The third limitation was the assumption that engaging in certain SRBs confer risk, which may depend on participant’s relationship characteristics and the frequency with which individuals engaged in these behaviors, both of which were not captured in this study. For instance, no condom use in a stable relationship with a committed partner may be due to the use of long-term contraceptive methods. Fourth, SRBs were measured using self-reports, which tend to underestimate females’ sexual experiences (Hovdestad et al., 2015). However, in this study, SRBs were measured during a clinical interview with a primary provider, which has been shown to be more accurate than reports to typical paper questionnaires (Diaz, Peake, Nucci-Sack, & Shankar, 2017). Finally, even though this study controlled for the number of visits in the estimation of SRB trajectories, it is possible that the intervention study participants received through the adolescent health clinic, which may or may not be adequately indexed just by number of study visits, could be exerting a differential influence based on a variety of participant-level characteristics including both maltreatment experiences and SRBs.

Despite these limitations, this study provides unique information about patterns of abuse and neglect and is the first study to date to link profiles of maltreatment to SRB trajectories across adolescence and young adulthood in urban racial/ethnic minority girls. Future research needs to examine mechanisms through which maltreatment may impact SRB and explore resiliency factors in youth in adversity. Prior theoretical literature posits several biological, interpersonal, and psychosocial pathways through which exposure to adverse childhood experience impact developmental outcomes; however, more work is needed to pinpoint unique pathways associated with different constellations of childhood adversity exposure. Additional research should also assess if the effect of childhood maltreatment is moderated by individual characteristics, social support, school environment, and coping strategies.

Conclusion

Using a sample of predominantly Hispanic and Black and low-income adolescent girls and young women, we identified four constellations of maltreatment experiences, with distinct trajectories of SRB from adolescence to young adulthood. Our findings highlight that understanding heterogeneity within maltreated populations could aid prevention efforts in promoting healthy sexual development in our vulnerable populations. The prevalence and implications of abuse and neglect underscore the need for better and more comprehensive tools in clinical and research settings to identify maltreatment exposures and their effects. One effective strategy may be face-to-face unstructured interviews conducted by primary care providers, which has been shown to identify significantly more reports of abuse and neglect than the paper and pencil questionnaire (Diaz et al., 2017). Additionally, results from this longitudinal developmentally focused study can inform tailored prevention and intervention efforts that recognize heterogeneity in the maltreatment experiences of adolescents and young adults and meet their particular needs in a developmentally appropriate manner. Given that SRB increases in adolescence and decelerates in young adulthood, it is necessary to design and implement effective sexual health intervention programs earlier in adolescence (e.g., aiming to increase youth self-efficacy and decision-making skills), particularly among youth with a history of maltreatment. Girls who had experienced co-occurring sexual and non-sexual maltreatment types exhibited heightened SRBs that continue to increase in young adulthood; they would also benefit from additional mental and sexual health services throughout adolescence and young adulthood to mitigate the negative effects of maltreatment that may otherwise lead to life course persistent sexual risk patterns. Ultimately, the larger society needs to recognize crucial social forces (e.g., stigma and victim-blaming) that affect girls’ sexual development, and work together to address factors such as gender inequalities and stereotypes (Marston & King, 2006).

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Profiles of Childhood Maltreatment in Average Abuse and Neglect Exposure

Table S1. Fit Statistics From Latent Class Analy sis of Childhood Maltreatment (N = 882)

Table S2. Adolescent Sociodemographic Characteristics by Maltreatment Profiles

Table S3. Estimates From Multilevel Growth Models for Sexual Risk Behaviors

Table S4. Estimates From Multilevel Growth Models for the Number of Lifetime Sexual Partners

Table S5. Estimates From Multilevel Growth Models for the Frequency of Condom Use

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI072204). The findings and conclusions of this report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funder. The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s website:

Contributor Information

Li Niu, Fordham University and Mount Sinai Adolescent Health Center and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Joshua Brown, Fordham University.

Lindsay Till Hoyt, Fordham University.

Anthony Salandy, Mount Sinai Adolescent Health Center.

Anne Nucci-Sack, Mount Sinai Adolescent Health Center.

Viswanathan Shankar, Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Robert D. Burk, Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Nicolas F. Schlecht, Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center

Angela Diaz, Mount Sinai Adolescent Health Center and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

- Armour C, Elklit A, & Christoffersen MN (2014). A latent class analysis of childhood maltreatment: Identifying abuse typologies. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 19(1), 23–39. 10.1080/15325024.2012.734205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AJ (2009). Adult recall of childhood psychological maltreatment: Definitional strategies and challenges. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 703–714. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Steinberg L, Houts RM, & Halpern-Felsher BL (2010). The development of reproductive strategy in females: Early maternal harshness → earlier menarche → increased sexual risk taking. Developmental Psychology, 46, 120–128. 10.1037/a0015549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, & Handelsman L (1997). Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 340–348. 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, .. . Zule W (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27, 169–190. 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black M, Oberlander S, Lewis T, Knight E, Zolotor M, Litrownik A, ... English D (2009). A prospective investigation of sexual intercourse among adolescents maltreated prior to age 12. Pediatrics, 124, 941–949. 10.1542/peds.2008-3836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1973). Attachment and loss: Volume II: Separation, anxiety and anger. London, UK: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Courville DK, Schlecht NF, Burk RD, Strickler HD, Rojas M, Lorde-Rollins E, ... Diaz A (2014). Strategies for conducting adolescent health research in the clinical setting: The Mount Sinai Adolescent Health Center HPV experience. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 27(5), e103–e108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J (1996). A self-trauma model for treating adult survivors of severe child abuse. In Briere J, Berliner L, Bulkley JA, Jenny C, & Reid T (Eds.), The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment (pp. 140–157). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brodbeck J, Bachmann MS, Croudace TJ, & Brown A (2013). Comparing growth trajectories of risk behaviors from late adolescence through young adulthood: An accelerated design. Developmental Psychology, 49, 1732. 10.1037/a0030873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffardi AL, Thomas KK, Holmes KK, & Manhart LE (2008). Moving upstream: Ecosocial and psychosocial correlates of sexually transmitted infections among young adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 1128–1136. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2017. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/2017-STD-Surveillance-Report_CDC-clearance-9.10.18.pdf

- Choukas-Bradley S, Giletta M, Widman L, Cohen GL, & Prinstein MJ (2014). Experimentally measured susceptibility to peer influence and adolescent sexual behavior trajectories: A preliminary study. Developmental Psychology, 50, 2221. 10.1037/a0037300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, & Lanza ST (2013). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences (Vol. 718). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz A, Peake K, Nucci-Sack A, & Shankar V (2017). Comparison of modes of administration of screens to identify a history of childhood physical abuse in an adolescent and young adult population. Annals of Global Health, 83, 726–734. 10.1016/j.aogh.2017.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz A, Shankar V, Nucci-Sack A, Linares LO, Salandy A, Strickler HD, ... Schlecht NF (2020). Effect of child abuse and neglect on risk behaviors in inner-city minority female adolescents and young adults. Child Abuse & Neglect, 101, 104347. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, & Tofighi D (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12, 121. 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, .. . Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, Zimmerman MA, & Caldwell CH (2007). Growth trajectories of sexual risk behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1096–1101. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, & Browne A (1985). The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 55, 530–541. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, & Turner HA (2009). Lifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 403–411. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner HA, & Hamby SL (2014). Trends in children’s exposure to violence, 2003 to 2011. JAMA Pediatrics, 168, 540–546. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.5296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner H, Hamby SL, & Ormrod R (2011). Polyvictimization: Children’s exposure to multiple types of violence, crime, and abuse. Juvenile Justice Bulletin, NCJ 235504. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, & Hamby SL (2013). Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: An update. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(7), 614–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, & Hamby SL (2015). Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: Results from the national survey of children’s exposure to violence. JAMA Pediatrics, 169, 746–754. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forhan SE, Gottlieb SL, Sternberg MR, Xu F, Datta SD, McQuillan GM, .. . Markowitz LE (2009). Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among female adolescents aged 14 to 19 in the United States. Pediatrics, 124, 1505–1512. 10.1542/peds.2009-0674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm HC, Lee Y, Ozonoff A, & Van Wert MJ (2010). The impact of multiple types of child maltreatment on subsequent risk behaviors among women during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 528–540. 10.1007/s10964-009-9490-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon AA, Hussey JM, & Halpern CT (2011). Childhood abuse and neglect and the risk of STDs in early adulthood. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 43(1), 16–22. 10.1363/4301611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen AL, Connelly CD, Roesch SC, Hough RL, & Landsverk JA (2009). Child maltreatment profiles and adjustment problems in high-risk adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 361–378. 10.1177/0886260508316476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heany SJ, Groenewold NA, Uhlmann A, Dalvie S, Stein DJ, & Brooks SJ (2018). The neural correlates of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire scores in adults: A meta-analysis and review of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Development and Psychopathology, 30, 1475–1485. 10.1017/S0954579417001717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich CC, Brookmeyer KA, Shrier LA, & Shahar G (2006). Supportive relationships and sexual risk behavior in adolescence: An ecological–transactional approach. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31, 286–297. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovdestad W, Campeau A, Potter D, & Tonmyr L (2015). A systematic review of childhood maltreatment assessments in population-representative surveys since 1990. PLoS One, 10, e0123366. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Runyan DK, Lewis T, Litrownik AJ, Black MM, Wiley T, ... Nagin DS (2010). Trajectories of childhood sexual abuse and early adolescent HIV/AIDS risk behaviors: The role of other maltreatment, witnessed violence, and child gender. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39, 667–680. 10.1080/15374416.2010.501286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Mennen FE, & Trickett PK (2017). Patterns and correlates of co-occurrence among multiple types of child maltreatment. Child & Family Social Work, 22, 492–502. 10.1111/cfs.12268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D (2018). MIMRGNS: Stata module to run margins after mi estimate. Statistical Software Components. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s457795.html

- Koss KJ, & Gunnar MR (2018). Annual research review: Early adversity, the hypothalamic–pituitary–-adrenocortical axis, and child psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59, 327–346. 10.1111/jcpp.12784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalor K, & McElvaney R (2010). Child sexual abuse, links to later sexual exploitation/high-risk sexual behavior, and prevention/treatment programs. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 11, 159–177. 10.1177/1524838010378299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares LO, Shankar V, Diaz A, Nucci-Sack A, Strickler HD, Peake K, ... Schlecht NF (2015). Association between cumulative psychosocial risk and cervical human papillomavirus infection among female adolescents in a free vaccination program. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 36, 620–627. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London S, Quinn K, Scheidell JD, Frueh BC, & Khan MR (2017). Adverse experiences in childhood and sexually transmitted infection risk from adolescence into adulthood. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 44, 524–532. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, Maheu F, Tu M, Fiocco A, & Schramek TE (2007). The effects of stress and stress hormones on human cognition: Implications for the field of brain and cognition. Brain and Cognition, 65, 209–237. 10.1016/j.bandc.2007.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston C, & King E (2006). Factors that shape young people’s sexual behaviour: A systematic review. The Lancet, 368, 1581–1586. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69662-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS (1998). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine, 338, 171–179. 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674. 10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molenberghs G, & Kenward M (2007). Missing data in clinical studies. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Naramore R, Bright MA, Epps N, & Hardt NS (2017). Youth arrested for trading sex have the highest rates of childhood adversity: A statewide study of juvenile offenders. Sexual Abuse, 29, 396–410. 10.1177/1079063215603064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negriff S, Schneiderman JU, & Trickett PK (2015). Child maltreatment and sexual risk behavior: Maltreatment types and gender differences. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 36, 708–716. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negriff S, Susman EJ, & Trickett PK (2011). The developmental pathway from pubertal timing to delinquency and sexual activity from early to late adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 1343–1356. 10.1007/s10964-010-9621-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negriff S, & Valente TW (2018). Structural characteristics of the online social networks of maltreated youth and offline sexual risk behavior. Child Abuse & Neglect, 85, 209–219. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Haralson KJ, Butler EM, & Shenk CE (2011). Childhood maltreatment, psychological dysregulation, and risky sexual behaviors in female adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 36, 743–752. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nooner KB, Litrownik AJ, Thompson R, Margolis B, English DJ, Knight ED, ... Roesch S (2010). Youth self-report of physical and sexual abuse: A latent class analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34, 146–154. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, & Vos T (2012). The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 9, e1001349. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, & Muthén BO (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14, 535–569. 10.1080/10705510701575396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrenko CL, Friend A, Garrido EF, Taussig HN, & Culhane SE (2012). Does subtype matter? Assessing the effects of maltreatment on functioning in preadolescent youth in out-of-home care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36, 633–644. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflieger JC, Cook EC, Niccolai LM, & Connell CM (2013). Racial/ethnic differences in patterns of sexual risk behavior and rates of sexually transmitted infections among female young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 903–909. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pingel ES, Bauermeister JA, Elkington KS, Fergus S, Caldwell CH, & Zimmerman MA (2012). Condom use trajectories in adolescence and the transition to adulthood: The role of mother and father support. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22, 350–366. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00775.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, & Crockett LJ (2003). Sexual risk taking in adolescence: The role of self-regulation and attraction to risk. Developmental Psychology, 39, 1036. 10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston P, & White IR (2011). Multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE): implementation in Stata. Journal of Statistical Software, 45, 1–20. 10.18637/jss.v045.i04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Mendle J, & Markowitz AJ (2015). Early childhood maltreatment and girls’ sexual behavior: The mediating role of pubertal timing. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57, 342–347. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, & Carey MP (2010). Child maltreatment and women’s adult sexual risk behavior: Childhood sexual abuse as a unique risk factor. Child Maltreatment, 15, 324–335. 10.1177/1077559510381112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, Hickendorff M, van Hemert AM, Bernstein DP, & Elzinga BM (2014). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: Factor structure, measurement invariance, and validity across emotional disorders. Psychological Assessment, 26, 717. 10.1037/pas0000002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2017). Stata statistical software: Release 15. College: Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]