Abstract

The Covid-19 outbreak has taken a substantial toll on the mental and physical wellbeing of healthcare workers (HCWs), impacting healthcare systems at a global scale. One year into the pandemic, the need to establish the prevalence of sleep dysfunction and psychological distress in the face of COVID-19, identify risk and protective factors and explore effective countermeasures remains of critical importance. Despite implicit limitations relating to the quality of available studies, a plethora of evidence to-date suggests that a considerable proportion of HCWs experience significant sleep disturbances (estimated to afflict every two in five HCWs) as well as mood symptoms (with more than one in five reporting high levels of depression or anxiety). Younger age, female gender, frontline status, fear or risk of infection, occupation, current or past mental health concerns, and a lower level of social support were all associated with a greater risk of disturbed sleep and adverse psychological outcomes. Furthermore, we discuss the link between sleep deprivation, susceptibility to viral infections and psychosocial wellbeing, in relevance to COVID-19 and summarize the existing evidence regarding the presence and predictors of traumatic stress/PTSD and burnout in HCWs. Finally, we highlight the role of resilience and tailored interventions in order to mitigate vulnerability and prevent long-term physical and psychological implications. Indeed, promoting psychological resilience through an enhanced social support network has proven crucial for HCWs in coping under these strenuous circumstances. Future research should aim to provide high quality information on the long-term consequences and the effectiveness of applied interventions.

Keywords: COVID-19, Healthcare workers, Sleep dysfunction, Mental health, PTSD, Burnout

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak began with the emergence of a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in December 2019, in Wuhan, China [1] and was declared a pandemic on March 11th 2020 by the World Health Organization (WHO) [2]. As a result, the rapid spread of COVID-19 has placed a significant strain on healthcare services across the globe. The general population have been directed to stay at home, maintain social distance and minimise contact with others. As a way of mitigating the spread of the virus, many countries have adopted a national lockdown policy, the economic and societal implications of which have been felt hard. Yet, in the face of the pandemic, healthcare workers (HCWs) find themselves in a particularly vulnerable position. Tasked with combating the effects of the virus, they are placed at the core of the pandemic, and thus predisposed to a number of risks. Due to the nature of their work, they are subject to heavy workloads, unpredictable work patterns, and a high risk of COVID-19 infection [3].

Multiple work pressures increase the risk of adverse mental health outcomes, such as depression, anxiety, burnout, PTSD and sleep dysfunction. Indeed, during a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, the quality of sleep in HCWs becomes of essence. Poor quality or lack of sleep can impair cognitive functioning and decision-making processes, thereby reducing work efficiency and increasing risk of medical errors [4]. Compromised performance results in not only poor patient outcomes, but also reduced job and personal satisfaction and increased burnout and adverse mental health in healthcare professionals. It can compromise immune response and increase risk of COVID-19 infection, which itself can lead to a number of physical and mental complications [5].

Therefore, the consequences of poor sleep in HCWs during the COVID-19 response are multiple, varied and unduly harmful. One year into the pandemic, the need to establish the prevalence of sleep dysfunction in the face of COVID-19, identify the risk factors for its development, and explore ways in which we can minimise its impact remains of critical importance. In addition to this, we further discuss the links between psychosocial stress, sleep deprivation, and susceptibility to viral infections in relevance to COVID-19 and summarize the evidence to-date regarding the presence and predictors of depression, anxiety, traumatic stress/PTSD and burnout in HCWs. Finally, we highlight the role of resilience and tailored interventions in order to mitigate vulnerability and prevent long-term physical and psychological implications.

2. Sleep dysfunction

Sleep dysfunction is characterised by diminished sleep quality and quantity and encompasses a number of sleep-related problems such as difficulty falling asleep at night, waking up in the early hours and using sedative medication on a regular basis, among others. Poor or disturbed sleep can have a detrimental impact on quality of life and is associated with various physical complications, including increased risk of obesity, diabetes, heart attack and stroke [6]. On the contrary, fair sleep is thought to boost energy levels, relieve fatigue, maintain psychological well-being and improve overall bodily functioning [7].

Unusual work schedules, exposure to night shifts and other contextual work factors already place HCWs at an increased risk of sleep problems. In addition, HCWs are often exposed to severe job stresses and burnout associated with the development of mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression, which in turn further increase the likelihood of sleep-related concerns. This can hinder the provision of quality healthcare services, and adversely affect patient care [8].

2.1. Sleep and COVID-19: a bidirectional relationship

A number of additional stressors during COVID-19 outbreak seem to have accentuated a pre-existing trend, notwithstanding the fact that HCWs are at increased risk of COVID-19 infection [9]. This is particularly true for frontline HCW's (ie those directly involved in the care of COVID-infected patients) for whom the likelihood of hospital admission due to COVID-infection was 3.3-fold higher than for their non-frontline counterparts [10]. Hence, alongside a number of other risk factors discussed in detail below, it is well established that a high risk of COVID-19 infection (composed of factors such as frontline status, occupation, etc.) increases the chance of experiencing sleep disturbances in HCWs. There is extensive evidence of the link between sleep and immunity: disturbed sleep and insomnia have been associated with an increased probability of respiratory infections such as common cold and pneumonia and several studies have found a relationship between sleep duration and vaccination response. Furthermore, there appears to be a bi-directional relationship between sleep, mental health problems and burnout [5.9] with a recent study showing that less sleep duration, poorer sleep quality (with a higher number of sleep problems), and feelings of burnout are associated with higher odds of COVID-19 infection in HCWs [5]. The underlying mechanism proposed is that lack of quality sleep can have a negative impact on the immune system, impair performance and cognitive functioning, thus leading to heightened risk of error and increasing susceptibility to viral transmission and infection. These studies, despite their implicit limitations, add to the evidence base confirming that sufficient and good quality sleep is essential for both physical and mental wellbeing in a multitude of ways and particularly in vulnerable or exposed groups.

2.2. Prevalence of sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic

Mild symptoms of stress, anxiety and fear in the face of a crisis may be considered a partly normal emotional reaction. However, in past epidemics, such as H1N1 Influenza, MERS and SARS, HCWs have demonstrated considerable levels of sleep problems and distress [11]. Still, COVID-19 has proved both more infectious and prevalent than other recent viral pandemics and created new challenges regarding the physical and psychological wellbeing of high risk groups such as HCWs.

More than a year into the pandemic, several studies and systematic reviews have reported on the prevalence of sleep disturbances and insomnia in HCWs. Despite a degree of variation, reports of disturbed sleep were significant: in four different systematic reviews with meta-analysis pooled prevalence rates for sleep problems in HCWs ranged from 36% [12] to 37% [35], 39% [13] and 45% [14]. On the whole, around two in five HCWs experienced a degree of sleep dysfunction during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Most studies quantified sleep habits with the use of self-administered validated psychometric scales such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), and Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS) while some utilised researcher-designed questionnaires. Outcome measure selection can have a significant impact on the results and can partly explain the heterogeneity in rates of sleep dysfunction across different studies [15,16]. It is important to note that different outcome measures assess symptoms across different timeframes, and that the cut-off score will vary between studies. Such considerations are crucial when attempting to generalise across studies. In the review by Jahrami et al. [12], for example, the researcher-developed measures (with a reported prevalence rate of 25.2%) appeared to be less sensitive in detecting sleep problems compared to the well-established self-assessment tools such as the PSQI (with a prevalence rate of 39.6%). Likewise, PSQI demonstrated higher rates compared to AIS and ISI; this is possible due to the fact that PSQI evaluates quality of sleep in general (capturing a broad range of sleep-related issues eg nightmares, snoring, sleep medication use), whereas AIS is more specific to insomnia and more comparable to the ISI.

Sleeping difficulties were a common concern in the general population, too, with estimates similar or slightly lower than those reported for HCWs. Both groups were found to have comparative rates of sleep problems (36% in HCWs vs 32% in the general population) in a recent systematic review with meta-analysis including forty-four papers and a total of 54,231 participants from 13 countries, though significant variation within the literature was noted with estimates for sleep problems among all populations using any measure ranging from 8% to 91% [12]. Unsurprisingly, SARS-COV-2-infected patients appeared to be the most affected group at 75% [12]. The symptomatology of the disease is characterised by cough, fever and difficulty breathing, all of which are associated with poor sleep, while pain levels and medication side effects may further contribute to a lack of quality sleep in this group [17,18].

As mentioned above, sleep concerns are a common feature in HCWs in ordinary times; the prevalence of sleep disruption in nurses, the largest group of HCWs, for example, has been stipulated as 32.6% in a pre-COVID study [19]. However, there appears to be an increase in prevalence following the COVID-19 outbreak. In one Iraqi study, 68.3% of physicians reported poor sleep during COVID-19, whereas a similar study, conducted a year prior in the same region, reported an estimate of 45.5% [20]. Likewise, a Chinese meta-analysis found that the pooled prevalence of sleep disturbances during the COVID-19 pandemic was 45%, which was higher than that in Chinese HCWs before the outbreak (39%) [14].

2.3. Risk factors for sleep dysfunction

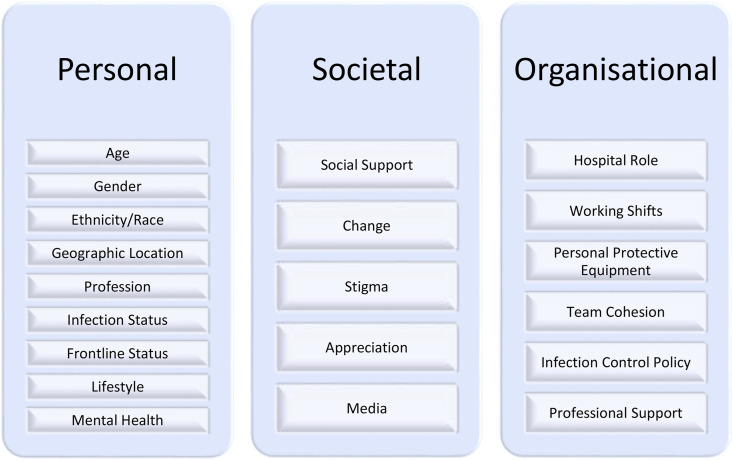

To help identify risk of adverse mental health outcomes in HCWs during COVID-19, a number of risk and protective factors have been suggested [21]. We have stratified these into three socio-ecological levels, namely individual, social and organisational, as shown in Fig. 1 . Available evidence has demonstrated the validity and importance of factors at each level [22,23].

Fig. 1.

Risk factors for sleep dysfunction.

2.3.1. Personal factors

Personal-level factors include socio-demographic and other characteristics, such as age, sex, ethnicity, race, marital status, previous psychiatric illness, geographic distribution, COVID-19 status, frontline status, and profession.

-

•

Gender: Despite an established gender gap for anxious and depressive symptoms (usually higher among females), the relationship between sex and sleep dysfunction has been inconsistent. Across all populations, male gender presented as a risk factor for sleep disturbances, yet amongst a HCW cohort, sleep dysfunction in females was higher than in males [14]. The issue, however, of sex differences remains controversial across mental health outcomes in HCWs during the pandemic.

-

•

Age: A younger age was associated with an increased number of sleeping problems among HCWs during COVID-19. However, one meta-analysis identified a peculiar trend: while the prevalence of sleep disturbances among nurses decreased with increasing age among nurses the reverse was observed among physicians [15], though the reasoning behind this is unclear.

-

•

Ethnicity, Race: Although HCWs of a Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) background were disproportionately affected by COVID-19, there is little evidence pointing towards ethnicity as a risk factor for sleep dysfunction under the current parameters. One survey of HCWs in Missouri found that ethnic minority correspondents displayed fewer signs of anxiety and alcohol abuse, although this may due to an underrepresented sample [24]. Nevertheless, given the relationship between infection status, psychological wellbeing and sleep quality, further research and insight into the role of race and ethnicity in sleep dysfunction would be valuable.

-

•

Occupation: Mental health outcomes, including sleep dysfunction, were found to be worse for nurses and other non-medical HCWs compared with doctors [13,25]. However, this is not a consistent finding with some studies failing to confirm a difference while a meta-analysis by Salari et al. [15] demonstrated that the prevalence of sleep disturbances may be even greater in physicians rather than nurses.

-

•

Frontline status: Frontline HCWs demonstrated a greater rate and severity of sleep disturbances than non-frontline HCWs, with one study reporting sleep dysfunction as 57.4% and 40%, respectively [26]. While there is some disparity regarding the definition of ‘frontline’, this commonly refers to the provision of care to COVID-infected patients. For example, those working in COVID-positive wards or hospitals experienced reduced sleep quality and duration, greater psychological distress and a increased number of comorbid mental health problems [6]. This is thought to relate, in part, to the reduced social support and stigmatisation experienced by this cohort alongside the higher risk of infection and moral injury; experienced as a traumatic existential crisis in response to bearing witness to an act opposing one's moral beliefs [27].

-

•

Geographic Distribution: A meta-analysis by Xia et al. [14], found a higher prevalence of sleep disturbances in HCWs in Wuhan than in other regions. As the epicentre of the outbreak, Wuhan suffered from a greater number of cases, a shortage of medical and personal protective equipment, and pressure to contain the virus [25]. While a direct link between sleep and geographic location per se is unlikely, we can assume that other factors, such as staffing shortages and increased exposure to COVID-positive patients, would make working in areas with a high transmission rates a risk factor.

-

•

COVID-19 status: Infected HCWs, regardless of frontline status, demonstrated the highest rates of sleep disturbance [12]. This group experienced greater fear and isolation, in addition to the range of physical symptoms associated with infection.

-

•

Mental Health Status: An Italian study by Cellini et al. [28] reported that sleep problems in the general public were more prominent among people with a higher level of depression, anxiety, and stress. Likewise, a pre-existing mental health condition was a predictor of subsequent mental health problems, such as anxiety, depression, and sleep dysfunction in HCWs [29].

-

•

Lifestyle changes: Lifestyle factors, such as physical activity levels, smoking, alcohol and substance use may play a role in mediating sleep among HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic, although there is still limited evidence in this regard [9].

2.3.2. Societal & organisational factors

Society-level factors include perceived social support, change in living circumstances, and satisfaction with local and national government responses to COVID- 19, community appreciation or stigmatisation of HCWs. As above, previous studies have identified social support as a protective factor for mental health while absence of a support network, such as family and friends, had a significant impact on mental health outcomes. In a study for example, level of social support was found to positively correlate with self-efficacy and sleep quality and negatively with anxiety and stress [27].

Organisation-level factors include changes in hospital role or work hours, and lack or shortages of PPE, as well as team cohesion, satisfaction with hospital infection control policy and the availability of wider professional support. An inability to provide necessary care may lead to HCWs feeling unsupported. Given the novelty of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, a lack of hospital protocol, clear communication, protective equipment and appropriate professional support may further elicit feelings of fear and hopelessness amongst HCWs, leading to psychological distress and sleeping difficulties [30].

2.4. Improving sleep in HCWs

Evidently, there is a need to improve sleep hygiene in HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Identification of various risk factors at individual, interpersonal, institutional and community levels and early and accurate recognition of sleep dysfunction and psychological distress on a personal level enables the provision of effective and tailored management strategies. Practical recommendations include expressing stress and concerns to family members, relaxing by reading or performing yoga, exercising and addressing the consequences of sleep problems in a timely manner [31]. Other methods include administrative support, relaxation techniques, such as mindfulness, and reasonable working schedules to allow for appropriate rest and recovery [14]. At a societal level, there is a need to provide quality family and emotional support, while still mitigating risk of COVID transmission. Interventions should, in part, aim to improve cohesion within hospital teams, and target PPE and clinical care barriers in the hospital setting [21]. Finally, it may be helpful to address community stigma and pandemic-related negative media coverage relating to HCWs.

3. Depression and anxiety

The first rapid systematic review and meta-analyses of 13 cross-sectional studies and a total of 33,062 participants provided early evidence and raised awareness that a high proportion of healthcare professionals experience significant levels of anxiety, depression and insomnia during COVID-19 pandemic. It included 12 studies performed in China and one study from Singapore and showed that more than one of every five healthcare workers suffered from anxiety and/or depression, with pooled prevalence rates of 22.8% for depression and 23.2% for anxiety [13].

A number of subsequent systematic reviews reported broadly similar rates: estimated prevalence of depression and anxiety was 25% and 26%, respectively, among health care workers in a systematic review of 19 studies focussed on COVID-19 [32]. Depressive symptoms were ranging between 27.5 and 50.7% and anxiety symptoms were reported in 45% in the systematic review by Preti et al. [33] while the median prevalence of at 21% for depression and 24% for anxiety in another rapid systematic review [34].

These estimates are akin or at the lower end of the outcomes previously reported among HCWs during and after the MERS and SARS epidemics where high rates of depression and anxiety as well as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and moral injury were observed [[35], [36], [37], [38], [39]]. They are also strikingly higher compared to the global figures on common mental disorders provided by WHO ie 4.4% for depression and 3.6% for anxiety disorders [40].

Findings, however, are inconsistent when comparing rates between HCWs and the general population during the same period of time. Luo et al. [32] found that rates were highest among patients with pre-existing conditions and COVID-19 infection (56% and 55%) and overall similar between healthcare workers and the general public; though noted that studies from a number of countries such as China, Italy, Turkey, Spain and Iran reported higher-than-pooled prevalence among healthcare workers and the general population [32]. Vindegaard and Benros [41] review, identified twenty studies of healthcare workers in a subgroup analysis and concluded that they generally reported more anxiety, depression, and sleep problems compared to the general population.

Anxiety symptoms were overall more frequent than depression; an observation consistent across most studies to date. Although, the application of different assessment scales and cut-off scores introduced great between-study heterogeneity, it appears that the majority of the HCWs experienced mild or mild-to-moderate symptoms both for depression and anxiety, while more severe symptoms were less common among participants.

Pappa et al. [13], revealed potentially important gender and occupational differences in their sub-analysis. Female and nursing staff exhibited higher prevalence estimates both for anxiety and depression compared to their male counterparts and physicians respectively. These results may be partly confounded by the fact that nurses are mostly female while also reflecting the already established gender gap for anxious and depressive symptoms [42]. Nevertheless, it could be also attributed to the fact that the pandemic has generally fallen hard on woman [43] while nurses may be more exposed to risk of infection and moral injury as they spend more time on wards and are in closer contact with patients providing direct care [44].

A subsequent meta-analysis [32] found that rates of depression were highest among those with a pre-existing mental health condition which in fact has been noted for most psychological outcomes. Other common risk factors included direct contact with Covid-19 patients, high infection risk and fear of infection, lower socioeconomic status and social isolation and protective factors having sufficient medical resources and protection and up-to-date and accurate information. Unsurprisingly, level of social support was found to positively correlate with better sleep and negatively with levels of anxiety and stress [27]. In fact, a cross-sectional study of 1092 HCWs across the US identified social support need as the only consistently significant predictor of probable depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalised anxiety disorder, and alcohol use disorder while the other, personal, societal and organisational factors varied by mental health outcome [21]. Moreover, the psychological impact of the crisis is not only felt by frontline respiratory and intensive care physicians and nurses but also by HCW of other specialties including, for example, surgeons, anaesthesiologists [45] and mental health workers [13]. Sadly, there have been also reports of suicides, amongst HCWs [3,46] which may be a particular concern given the fact that physicians are already at an increased risk of suicide compared to the general population [47].

4. Traumatic stress and post-traumatic stress disorder

HCWs remain vulnerable not only to the acute and immediate effects of the stress caused by exposure to trauma but also to the delayed onset and long-term psychological consequences of viral outbreaks. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) presents as a range of cognitive and behavioral symptoms, including irritability, fear, flashbacks and avoidant behavior, following exposure to a life-threatening or extremely stressful life event. In 2014, the global estimate for the frequency of a PTSD diagnosis was 1.1% among the general population [48]; yet, early evidence may suggest an increase in the face of COVID-19 [49].

A meta-analysis of 44 studies that examined the psychological impact of recent outbreaks on HCWs, including MERS/SARS/COVID-19/Ebola/Influenza A, reported the prevalence of PTSD symptoms to be between 11 and 73.4%, with symptoms lasting between 1 and 3 years in 10–40% of the sample [33]. Additionally, in the pooled prevalence, 51.5% of HCWs scored above the Impact of Event Scale- Revised (IES-R) cut-off, meeting the threshold for a possible PTSD diagnosis [33]. Subsequent COVID-19 studies have suggested lower, yet significant rates; for example, prevalence of traumatic stress was reported as 3.8% by Yin et al. [50], 9.8% by Wang et al. [51] and 27% by Caillet et al., [52]. A recent systematic review of 15 studies with a total sample of 5628 HCWs, by Salehi et al. [49] estimated the frequency of PTSD symptoms at 18%. It also revealed a higher frequency of PTSD-related symptoms among HCWs, with roughly every two in ten suffering as compared to one in ten in the general population.

As with other psychological outcomes, there is significant variability in reported figures. Confounding factors include a difference in the reproduction rate of the virus across different outbreaks, as well as discrepancies in quarantine measures, health care system preparedness, HCW workload, and social support across different countries.

Furthermore, evidence from the SARS epidemic showed a positive correlation between perceived risk of exposure and PTSD symptoms, with similar findings reported during the COVID-19 pandemic [53]. In fact, direct contact with COVID-19 patients appeared to be the leading predictor for development of PTSD symptoms during this outbreak, closely followed by female gender, older age, and greater concern regarding infection spread to relatives or within the occupational environment [35,[54], [55], [56], [57]]. Exposure to COVID-related patient death was a significant predictor for the development of secondary traumatic stress, with over 67% of this sub-group experiencing symptoms as opposed to 33% in the group with no direct exposure [56]. Similarly, prevalence in frontline HCWs was also reportedly higher than those working in other units (47.5% and 30.3% respectively). In addition, higher PTSD scores appeared to be associated with insomnia, burnout, and peri-traumatic distress [57,58].

Stress-related symptoms were more frequent in women than men, and this was reported consistently across studies. Overall, women scored higher on various clinical scales assessing traumatic stress and PTSD symptoms, including the two most frequently utilized scales IES-R and PCL-5 (PTSD Checklist for DSM-5) [50,55,57,59]. Yin et al. [50] tracked the trajectory of PTSD symptoms 1 month after the COVID-19 outbreak in China, and revealed a hazard ratio of 2.1.

Comparing to previous epidemics, data from the aforementioned meta-analysis showed that PTSD features in HCWs were more prevalent in the MERS outbreak (40.7%) than both in SARS (16.7%) and COVID-19 (7.7%). Likewise, the frequency of PTSD features amongst HCWs exposed to MERS/SARS appeared to be lower (20.7%) than in the general population suffering from MERS/SARS (32.5%) [39,60]. However, PTSD symptoms typically have a delayed onset and may manifest several months or years after the initial traumatic event (NICE) [61]. It is worth noting that early assessment of post-traumatic symptoms may not reflect a true PTSD diagnosis, but rather a temporary affliction, such as acute stress disorder (ASD) or peritraumatic stress (PTS). Hence, it might be too early to accurately assess the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, as seen from previous viral outbreaks [62].

Nevertheless, timely intervention has the potential to halt the progression of early traumatic stress symptoms into PSTD. To date, several studies have indicated that HCWs prefer occupational security, personal protection, and social support rather than professional psychological intervention [35,51,63]. This can be used to guide first-line interventions in HCWs suffering from PTSD-related symptoms during COVID-19. Nevertheless, further research is required to evaluate the long-term projections of COVID-19-related trauma and stress, both in HCWs and in the general public.

5. Burnout and resilience

In 2019, Burn-out was added by the WHO to the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) as an occupational phenomenon and defined as “a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterized by three dimensions: feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; increased mental distance from one's job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one's job; and reduced professional efficacy”. In fact, the role of burnout and the importance of resilience in healthcare professionals had garnered increased interest over recent years [3,64]. A systematic review from 2017 [65], for example, including studies from the past 20 years, reported on the presence of moderate to high Emotional Exhaustion-EE (31–54.3%) and Depersonalization-DP (17.4–44.5%) as well as low Personal Accomplishment-PA (6–39.6%) in doctors in the UK. The previous year, a systematic review published in The Lancet warned that burnout had reached “epidemic levels” amongst physicians [66].

Indeed, excessive levels of burnout may have important implications for both staff wellbeing and the capacity and efficiency of the healthcare systems given the known associations between burnout and long-term physical and psychological sequelae such as reduced productivity, increased physician turnover, sick leave and absenteeism as well as medical errors, road accidents, mental health concerns and suicidality [47].

As mentioned above, burnout is already high among physicians and other HCWs in ordinary times with prevalence rates up to or over 50% [67] and was also a frequently associated feature during previous epidemics particularly for HCWs working long hours [39,68]. During the current pandemic, prevalence of burnout has initially attracted less attention compared to other psychological outcomes but an increasing number of studies have since emerged confirming the presence of considerable levels of emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and sense of reduced accomplishment [[69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79]].

The majority of these studies used the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) tool to evaluate the burnout with the remainder either using alternative validated scales (ie Stanford Professional Fulfillment Index, Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, Professional Quality of Life Scale) or non-validated, self-designed questionnaires [80]. Participants were usually auto-selected and assessments were based on self-reporting. None of the studies followed up participants or provided long-term outcomes. Some studies focused on frontline and/or patient facing services while others included all HCWs. In addition, some reported exclusively or separately on different occupational groups such as doctors and nurses or level of seniority and experience eg trainees/residents or sub-specialties.

Prevalence rates varied across different areas and settings but was overall significant; the noted variation in reported figures may be further explained by socioeconomic and cultural differences alongside disparity in transmission rates, preparedness and infrastructure of healthcare systems. In the study by Giusti et al. [81], for example, that evaluated the psychological impact of Covid-19 pandemic on HCWs in Italy –one of the harder hit regions during the initial stages of the outbreak - moderate to severe levels of EE were present in 67% and of PA in 26% of the sample while PA was recorded in more than 60%. Interestingly, a multi-centre study from Greece [82] reported even greater levels of burnout (EE 69%, DP 86% and low PA 50%) despite the largely benign course of the outbreak during the same period of time.

There are conflicting findings concerning the rate of burnout among HCWs working with Covid-19 patients and/or in COVID-19 wards with most, but not all, demonstrating higher prevalence for first-line staff. A study, for example found that burnout rate was higher among frontline staff of emergency departments and intensive care units (ICUs) [75]. Likewise, another study from Italy, involving 1153 HCWs showed that those who were directly involved with COVID-19 patients experienced higher levels of burnout and associated somatic symptoms (such as muscle tension, sleep problems and changes in eating) [73]. Other studies however failed to confirm these differences including this study from Belgium in 647 HCWs were higher level of burnout, insomnia, and anxiety were noted among nurses in comparison to physicians but not in HCWs working in Covid-19 care units compared to those working in non-Covid-19 care units or in both [83]. Similarly, in a study from Romania first-line trainees (eg working in emergency departments and ICUs), experienced considerable but still lower levels of burnout (76%) compared to trainees working on different wards (86%); these findings are in contrast with those from a different study in which residents who were exposed to COVID-19 patients had higher rates of burnout compared to those in the non-exposed group [84].

Previous studies have shown higher rates of depression and burnout amongst psychiatrists [85,86] and mental health nurses [87] compared to other medical specialties, which have been attributed to both personal and organisational factors [88]. In a study of mental health care worker in the UK (another hard hit area from the early stages of the outbreak), more than half of the participants showed moderate to high EE and low to moderate PA and one in five demonstrated moderate to high DP [89].

Regarding sociodemographic and personal factors, younger age, female sex, occupation and current or past mental health status have all been implicated with a higher risk of burnout. Unsurprisingly, as women comprise up to 70% of the workforce and are also more likely to experience higher levels of work–family conflict, female gender was associated with higher emotional fatigue and a reduced sense of self-adequacy in several studies; although this finding was not consistent across studies. Similarly, nurses were found to have high or higher levels of burnout. In a study of HCWs working in COVID-19 wards, nurses were more likely to experience burnout (45%) compared to physicians (31%) [72]. Furthermore, in a recent systematic review of sixteen studies, including 18,935 nurses, the overall prevalence of emotional exhaustion was 34%, depersonalization was 12% and lack of personal accomplishment was 15% [90]. Mental health problems were also found to correlate with more frequent burnout which in turn may lead to increased rates of psychological difficulties, substance use and self-harm among HCWs [63].

Various studies have mentioned several other associated social and occupational factors that affect burnout levels including increased workload, inadequate PPE and training, lack of medical resources, working longer hours and in high-risk environment, worries about self-contamination and spread of infection, frequent or drastic changes in ways of working and policies, conflicting information, decreased social support, isolation and community stigma [80,90].

Though, most available studies did not evaluate any intervention to prevent or reduce burnout during the current crisis, authors provided recommendations based on their findings, highlighting that both organizational solutions and individual-focused interventions are required to support wellbeing, prevent the development of burnout and enhance resilience [63,66,91,92].

Psychological resilience broadly refers to the ability to cope with or overcome adversity and is critical for HCWs in coping through the continuous exposure to loss, distress and moral injury [93]. A meta-analysis showed that resilience significantly reduces burnout [94]. Therefore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is necessary to not only recognize the risk factors associated with burnout but also identify protective factors that promote resilience such as a sense of agency, close family bonds, community cohesion and social support [95]. Previous studies suggest that being female [87,96] and feeling supported at work [92] inferred higher levels of resilience in HCWs. Furthermore, several studies showed that an enhanced social support network during the COVID-19 pandemic can combat feelings of isolation and strengthen resilience among HCWs [[97], [98], [99]] and that providing psychological support during and after a crisis can significantly improve the coping abilities of HCWs exposed to trauma, thus leading to positive adaptations to adversity [100].

6. Conclusions

More than one year into the pandemic, the overwhelming evidence –although quantity has not always been matched by quality-points to the magnitude of effect of the COVID-19 crisis on the sleep and psychological wellbeing of healthcare workers, showcasing increased prevalence rates of sleep problems, burnout, depression, anxiety, and traumatic stress across a medley of healthcare staff. Findings can be utilized to advise targeted countermeasures in light of the current circumstances, taking heed of identified risk factors and predictors of poor sleep and ill mental health. Future research should aim to provide high quality, reliable information on the long-term implications and the effectiveness of applied interventions.

Funding

No source of funding.

Contributors

SP conceptualized the content. SP, NS and ES performed the literature search and created the tables. SP, NS and ES created the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and accepted the final form of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

All authors have nothing to disclose in relation to the submitted work.

The ICMJE Uniform Disclosure Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest associated with this article can be viewed by clicking on the following link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2021.07.009.

Conflict of interest

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

Multimedia component 1

References

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation Pneumonia of unknown cause- China. https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/ Last accessed 12/04/2021. Available from:

- 3.Papoutsi G., Giannakoulis V., Ntella V., et al. Global burden of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(2):195–2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00195-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medic G., Wille M., Hemels M.E. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep. 2017;9:151–161. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S134864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim H., Hedge S., LaFiura C., et al. COVID-19 illness in relation to sleep and burnout. BMJ NPH. 2021 doi: 10.1136/bmjnph-2021-000228. bmjnph-2021-000228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu K., Wei X. Analysis of psychological and sleep status and exercise rehabilitation of front-line clinical staff in the fight against COVID-19 in China. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2020;26:924085. doi: 10.12659/MSMBR.924085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva-Costa A., Griep R.H., Rotenberg L. Associations of a short sleep duration, insufficient sleep, and sleep disturbances with self-rated health among nurses. PloS One. 2015;10(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang C.X., Yang L., Liu S., et al. Survey of sleep disturbances and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front Psychiatr. 2020;11:306–312. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen L.H., Drew D.A., Graham M.S., et al. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:475–483. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.29.20084111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah A.S.V., Wood R., Gribben C., et al. Risk of hospital admission with coronavirus disease 2019 in healthcare workers and their households: nationwide linkage cohort study. BMJ. 2020;371:3582. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blake H., Bermingham F., Johnson G., et al. Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a digital learning package. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17(9):2997–3003. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17092997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jahrami H., BaHammam A.S., Bragazzi N.L., et al. Sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic by population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(2):299–313. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pappa S., Ntella V., Giannakas T., et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xia L., Chen C., Liu Z., et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances and sleep quality in Chinese healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatr. 2021;12:646342. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.646342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salari N., Khazaie H., Hosseinian-Far A., et al. The prevalence of sleep disturbances among physicians and nurses facing the COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Health. 2020;16:92. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00620-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pappa S., Giannakoulis V., Papoutsi E., et al. Author reply–Letter to the editor “The challenges of quantifying the psychological burden of COVID-19 on healthcare workers.”. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;92:209–210. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh D.P., Jamil R.T., Mahajan K. In: StatPearls. Cascella M., Rajnik M., Cuomo A., et al., editors. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): 2021. Nocturnal cough.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532273/ [Internet] Last accessed 11/04/2021. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi L., Lu Z.A., Que J.Y., et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):2014053. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai K., Lee T.Y., Chung M.H. Sleep disturbances in female nurses: a nationwide retrospective study. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2017;23(1):127–132. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2016.1248604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdulah D.M., Musa D.H. Sleep disturbances and stress of physicians during COVID-19 outbreak. Sleep Med X. 2020:100017. doi: 10.1016/j.sleepx.2020.100017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hennein R., Mew E.J., Lowe S.R. Socio-ecological predictors of mental health outcomes among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. PloS One. 2021;16(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sallis J.F., Owen N., Fisher E.B. 4th ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2008. Ecological models of health behavior. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice; pp. 465–485. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention The social-ecological model: a framework for prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/publichealthissue/social- ecologicalmodel.html Last accessed 10/04/2021. Available from:

- 24.Evanoff B.A., Strickland J.R., Dale A.M., et al. Work-related and personal factors associated with mental well-being during the COVID-19 response: survey of health care and other workers. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):21366. doi: 10.2196/21366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan B.Y.Q., Chew N.W.S., Lee G.K.H., et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(4):317–320. doi: 10.7326/M20-1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiao H., Zhang Y., Kong D., et al. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in January and February 2020 in China. Med Sci Mon. 2020;26:923549. doi: 10.12659/MSM.923549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cellini N., Canale N., Mioni G., et al. Changes in sleep pattern, sense of time and digital media use during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. J Sleep Res. 2020:13074. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L., Wu C., Gan Y., et al. Insomnia and the risk of depression: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Psychiatr. 2016;16:375. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1075-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moll S.E. The web of silence: a qualitative case study of early intervention and support for healthcare workers with mental ill-health. BMC Publ Health. 2014;14(1):138. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altena E., Baglioni C., Espie C.A., et al. Dealing with sleep problems during home confinement due to the COVID-19 outbreak: practical recommendations from a task force of the European CBT-I Academy. J Sleep Res. 2020;29:13052. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo M., Guo L., Yu M., et al. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatr Res. 2020;291:113190. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Preti E., Di Mattei V., Perego G., et al. The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review of the evidence. Curr Psychiatr Rep. 2020;22:43. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01166-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller A.E., Hafstad E.V., Himmels J.P.W., et al. The mental health impact of the covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: a rapid systematic review. Psychiatr Res. 2020;293:113441. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lancee W.J., Maunder R.G., Goldbloom D.S.D. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among Toronto hospital workers one to two years after the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:91–95. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tam C., Pang E., Lam L., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hongkong in 2003: stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1197–1204. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee S.M., Lang W.S., Cho A.R., et al. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantines hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatr. 2018;87:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koh D., Lim M.K., Chia S.E., et al. Risk perception and impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) on work and personal lives of healthcare workers in Singapore: what can we learn? Med Care. 2005;43:676–682. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000167181.36730.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Pablo G.S., Serrano J., Catalan A., et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2017. https://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/prevalence_global_health_estimates/en/ Last accessed 10/04/2021. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vindegaard N., Benros M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albert P.R. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015;40:219–221. doi: 10.1503/jpn.150205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burki T. The indirect impact of COVID-19 on women. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(8):904–905. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30568-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Z., Han B., Jiang R., et al. Mental health status of doctors and nurses during COVID-19 epidemic in China. SSRN Electron J. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3551329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu J., Xu Q.H., Wang C.M., et al. Psychological status of surgical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatr Res. 2020;288:112955. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montemurro N. The emotional impact of COVID-19: from medical staff to common people. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:23–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.West C., Dyrbye L., Shanafelt T. Physician burnout: contribution, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516–529. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karam E.G., Friedman M.J., Hill E.D., et al. Cumulative traumas and risk thresholds: 12-month PTSD in the World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(2):130–142. doi: 10.1002/da.22169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salehi M., Amanat M., Mohammadi M., et al. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder related symptoms in Coronavirus outbreaks: a systematic-review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin Q., Sun Z., Liu T., et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms of health care workers during the corona virus disease 2019. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2020;27(3):384–395. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y., Ma S., Yang C., et al. Acute psychological effects of Coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak among healthcare workers in China: a cross-sectional study. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:348. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01031-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Caillet A., Coste C., Sanchez R., et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on ICU caregivers. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2020;39(6):717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2020.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Si M.Y., Su X.Y., Jiang Y., et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on medical care workers in China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9:113. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chew N.W.S., Lee G.K.H., Tan B.Y.Q., et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benfante A., Di Tella M., Romeo A., et al. Traumatic stress in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: a review of the immediate impact. Front Psychol. 2020;11:569935. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.569935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Orrù G., Marzetti F., Conversano C., et al. Secondary traumatic stress and burnout in healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2021;18(1):337. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18010337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blekas A., Voitsidis P., Athanasiadou M., et al. COVID-19: PTSD symptoms in Greek health care professionals. Psychol Trauma: Theo Res Pract Pol. 2020;12(7):812–819. doi: 10.1037/tra0000914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dobson H., Malpas C.B., Burrell A.J., et al. Burnout and psychological distress amongst Australian healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Australas Psychiatr. 2021;29(1):26–30. doi: 10.1177/1039856220965045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Di Tella M., Romeo A., Benfante A., et al. Mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(6):1583–15877. doi: 10.1111/jep.13444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rogers J.P., Chesney E., Oliver D., et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiat. 2020;7(7):611–627. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK) Gaskell; Leicester (UK): 2005. Post-traumatic stress disorder: the management of PTSD in adults and children in primary and secondary care.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116/evidence/march-2005-full-guideline-pdf-6602623598 Last accessed 12/04/21. Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chong M.Y., Wang W.C., Hsieh W.C., et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:127–133. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Restauri N., Sheridan A.D. Burnout and posttraumatic stress disorder in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: intersection, impact, and interventions. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:921–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lemaire J., Wallace J. Burnout among doctors. BMJ. 2017;358:3360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Imo U. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among doctors in the UK: a systematic literature review of prevalence and associated factors. BJ Psych Bull. 2017;41:197–204. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.116.054247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.West C., Dyrbye L., Erwin P., et al. Intervention to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388:2272–2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rotenstein L., Torre M., Ramos M., et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. J Am Med Assoc. 2018;320:1131–1150. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim J., Choi J. Factors Influencing emergency nurses' burnout during an outbreak of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Korea. Asian Nurs Res. 2016;10:295–299. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Morgantini L., Naha U., Wang H., et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid turnaround global survey. PloS One. 2020;15(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elhadi M., Msherghi A., Elgzairi M., et al. Burnout syndrome among hospital healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and civil war: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatr. 2020;11:579563. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.579563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dimitriu M.C.T., Pantea-Stoian A., Smaranda A.C., et al. Burnout syndrome in Romanian medical residents in time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Hypotheses. 2020;144:109972. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sung C.W., Chen C.H., Fan C.Y., et al. Burnout in medical staffs during a coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. SSRN. 2020:3594567. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3594567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barello S., Palamenghi L., Graffinga G. Burnout and somatic symptoms among frontline healthcare professionals at the peak of the Italian COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr Res. 2020;290:113129. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu Y., Wang J., Luo C., et al. A comparison of burnout frequency among oncology physicians and nurses working on the frontline and usual wards during the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2020;60(1):60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sahin T., Aslaner H., Eker O.O., et al. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and burnout levels in emergency healthcare workers: a questionnaire study. Res Square. 2020 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-32073/v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hu D., Kong Y., Li W., et al. Frontline nurses' burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear statuses and their associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Clin Med. 2020;24:100424. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Luceno-Moreno L., Talavera-Velasco B., Garcia-Albuerne Y., et al. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress, anxiety depression, levels of resilience and burnout in Spanish health personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2020;17:15. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zerbini G., Ebigbo A., Reicherts P., et al. Psychosocial burden of healthcare professionals in times of OCVID-19 – a survey conducted at the University Hospital Augsburg. GMS. 2020;18:5. doi: 10.3205/000281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wan Z., Lian M., Ma H., et al. Factors associated with burnout among Chinese nurses during COVID-19 epidemic: a cross-sectional study. Res Square. 2020 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-31486/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sharifi M., Asadi-Pooya A.A., Mousavi-Roknabadi R.S. Burnout among healthcare providers of COVID-19; A systematic review of epidemiology and recommendations. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2021;9(1):7. doi: 10.22037/aaem.v9i1.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Giusti E.M., Pedroli E., D'Aniello G.E., et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on health professionals: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1684. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pappa S., Athanasiou N., Sakkas N., et al. From recession to depression? Prevalence and correlated of depression, anxiety, traumatic stress and burnout in healthcare workers during the OCVID-19 pandemic in Greece: a multi-centre, cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2021;18:2390. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tiete J., Guatteri M., Lachaux A., et al. Mental health outcomes in healthcare workers in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 care units: a cross-sectional survey in Belgium. Front Psychol. 2021;11:612241. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.612241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kannampallil T.G., Goss C.W., Evanoff B.A., et al. Exposure to COVID-19 patients increases physician trainee stress and burnout. PloS One. 2020;15(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dreary I., Agius R., Sadler A. Personality and stress in consultant psychiatrists. Int J Soc Psychiatr. 1996;42(2):112–123. doi: 10.1177/002076409604200205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kumar S., Hatcher S., Huggard P. Burnout in psychiatrists: an etiological model. Int J Psychiatr Med. 2005;25:405–416. doi: 10.2190/8XWB-AJF4-KPRR-LWMF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.López-López I.M., Gómez-Urquiza J.L., Cañadas G.R., et al. Prevalence of burnout in mental health nurses and related factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2019;28(5):1032–1041. doi: 10.1111/inm.12606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Firth-Cozens J. Improving the health of psychiatrists. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13(3):161–168. doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.106.003277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pappa S., Barnett J., Berges I., et al. Tired, worried and burned out but still resilient: a cross-sectional study of mental health workers during Covid-19 pandemic. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202104.0091/v1 Preprint accepted. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.Galanis P., Vraka I., Fragkou D., et al. Nurses' burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2021 doi: 10.1111/jan.14839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shanafelt T., Noseworthy J. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:129–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hofmeyer A., Taylor R., Kennedy K. Fostering compassion and reducing burnout: how can health system leaders respond in the Covid-19 pandemic and beyond? Nurse Educ Today. 2020;91:104502. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Balme E., Gerada C., Page L. Doctors need to be supported, not trained in resilience. BMJ. 2015;351:4709. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Deldar K., Froutan R., Dalvand S., et al. The Relationship between resiliency and burnout in Iranian burses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Sci. 2018;6(11):2250–2256. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2018.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bonanno G.A., Romero S.A., Klein S.I. The temporal elements of psychological resilience: an integrative framework for the study of individuals, families, and communities. Psychol Inq. 2015;25:139–169. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2015.992677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McCann C., Beddoe E., McCormick K., et al. Resilience in the health professions: a review of recent literature. Int J Wellbeing. 2013;3:60–81. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v3i1.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.[a] Sull A., Harland N., Moore A. Resilience of health-care workers in the UK; A cross-sectional survey. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2015;10:20. doi: 10.1186/s12995-015-0061-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; [b] Hou T., Zhang T., Cai W., et al. Social support and mental health among health care workers during coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak: a moderated mediation model. PloS One. 2020;15(5) doi: 10.1186/s12995-015-0061-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Southwick S.M., Southwick F.S. The loss of social connectedness as a major contributor to physician burnout: applying organizational and teamwork principles for prevention and recovery. JAMA Psyciat. 2020;77(5):449. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wu P.E., Styra R., Gold W.L. Mitigating the psychological effects of COVID-19 on health care workers. CMAJ (Can Med Assoc J) 2020;192(17):459–460. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kahn M.D., Bulanda J.J., Weissberger A., et al. Evaluation of a support group for Ebola hotline workers in Sierra Leone. Int J Cult Ment Health. 2016;9(2):164–171. doi: 10.1080/17542863.2016.1153121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Multimedia component 1