Abstract

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a common psychiatric illness with high prevalence and disease burden. Accumulating susceptibility genes for BD have been identified in recent years. However, the exact functions of these genes remain largely unknown. Despite its high heritability, gene and environment interaction is commonly accepted as the major contributing factor to BD pathogenesis. Intestine microbiota is increasingly recognized as a critical environmental factor for human health and diseases via the microbiota‐gut‐brain axis. BD individuals showed altered diversity and compositions in the commensal microbiota. In addition to pro‐inflammatory factors, such as interleukin‐6 and tumour necrosis factor‐α, type 1 interferon signalling pathway is also modulated by specific intestinal bacterial strains. Disruption of the microbiota‐gut‐brain axis contributes to peripheral and central nervous system inflammation, which accounts for the BD aetiology. Administration of type 1 interferon can induce the expression of TRANK1, which is associated with elevated circulating biomarkers of the impaired blood‐brain barrier in BD patients. In this review, we focus on the influence of intestine microbiota on the expression of bipolar gene TRANK1 and propose that intestine microbiota‐dependent type 1 interferon signalling is sufficient to induce the over‐expression of TRANK1, consequently causing the compromise of BBB integrity and facilitating the entrance of inflammatory mediators into the brain. Activated neuroinflammation eventually contributes to the occurrence and development of BD. This review provides a new perspective on how gut microbiota participate in the pathogenesis of BD. Future studies are needed to validate these assumptions and develop new treatment targets for BD.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, blood‐brain barrier, gut microbiota, TRANK1, type 1 interferon

1. INTRODUCTION

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a serious, recurring and highly disabling affective mental disorder. 1 According to data released by the World Health Organization in 2011, the global lifetime prevalence of BD is 2.4%. 1 The suicide risk of BD patients is much higher than that of the general population, and the proportion of suicide deaths among BD individuals is as high as 6% to 7%. 2 BD frequently occurs in the adolescence and early adulthood, severely impairing the cognitive and social functions of patients, and causes a huge burden of disease to the family and society. 3 However, the pathogenesis of BD remains largely unclear. The existing diagnostic criteria for BD are mainly based on clinical symptoms and lack of objective biomarkers. In clinical practice, it can easily cause missed diagnosis and misdiagnosis, which is not conducive to the treatment and prognosis of patients. 3 Therefore, further exploring the pathogenesis and exploring the targeted markers of the disease is of great significance for the clinical diagnosis and treatment of BD.

The interaction of genetic and environmental factors is considered to be one of the major aetiology of BD. 4 Different environmental factors (such as early childhood trauma, stress events, pathogen infection and intestinal ecosystem imbalance) act on genetically susceptible individuals, hindering the normal growth of neurons and promoting neuroinflammation, metabolism disturbance and oxidative stress, leading to dysfunction of the brain areas related to emotion regulation, and eventually causes emotional and behavioural abnormalities. 4 However, it is still unclear how environmental factors and genetic factors influence each other and contributes to the onset of BD. In the current review, special attention is paid to the bipolar risk gene, etratricopeptide repeat and ankyrin repeat containing 1 (TRANK1) and its potential interaction with the gut microbiota, which is speculated to impair the integrity of blood‐brain barrier (BBB) and facilitates the neuroinflammation in BD.

2. TRANK1, A RISK GENE FOR BD

Epidemiological studies of twins have shown that the genetic heritability of BD is as high as 70%‐85%, suggesting that genetic factors play an important role in the pathogenesis of BD. 5 , 6 In previous studies, we also found that specific single nucleotide polymorphisms were associated with the age of onset for BD patients. 7 In recent years, several important large‐sample whole‐genome sequencing studies have suggested that ADCY2, ANK3, CACNA1C, TENM4, SYNE1, ERBB2, TRANK1, etc, may be the risk genes for BD. 8 , 9 , 10 In a newly published study, TRANK1 has been further confirmed as the susceptibility gene for BD. 11 The TRANK1 gene is located on the short arm of chromosome 3 (3p22.2). The autoantibody of TRANK1 protein was originally found in the brain tissue of a mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus. It is mainly produced and secreted by immune cells such as neutrophils and natural killer cells in the peripheral blood and is widely expressed in the cerebral cortex, including the hippocampus, amygdala and cerebellum. 12 It is worth noting that the expression level of TRANK1 gene in the postmortem brain tissue of BD patients was significantly higher than that of healthy controls. 13 Compared with healthy individuals, circulating anti‐TRANK1 IgG was increased in a group of 356 plasma samples from patients with schizophrenia. 14 An integrated analysis of mRNA co‐expression network revealed that genes highly correlated with TRANK1 were significantly involved in the biological processes related to synaptic plasticity, dendritic spine, axon guidance and circadian rhythm. 11 In addition, TRANK1 rs71947856 variant was associated with circadian regulation and reported birth difficulties in patients with Kleine‐Levin syndrome, which is a rare disease characterized by severe episodic hypersomnia, with cognitive impairment and apathy or disinhibition. 15 However, the specific function of the TRANK1 gene in BD has not been clarified so far.

Previous studies have shown that TRANK1 may be involved in immune‐related signal regulation. In a mouse model where the interferon (IFN) regulatory factor 7 was knocked out or up‐regulated, it was found that the change in the expression level of this regulatory factor can affect the transcription level of TRANK1 through the type 1 IFN signalling pathway. 16 In differentiated hepatocytes, IFN‐α can up‐regulate the expression of TRANK1 through the STAT/JAK signalling pathway. 17 In a socially isolated mouse model, it was found that the expression level of the TRANK1 gene in the prefrontal lobe was significantly increased, and the expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) and plasma membrane vesicle‐associated protein‐1 (PV‐1) was up‐regulated, which indicated that the integrity of the blood‐brain barrier (BBB) was impaired, and the permeability was increased. 18 Elevation in pro‐inflammatory factors, such as interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) and tumour necrosis factor‐α (TNF‐α) in the brain, was also observed and further confirmed the activation of the central immune reaction. 18 Based on these findings, it is plausible to speculate that the expression of TRANK1 is regulated by the IFN signalling pathway, and the TRANK1 gene may be an important mediator affecting BBB permeability and neuroinflammation in the brain. However, how the expression of TRANK1 gene is regulated under pathological processes of BD remains to be further studied.

3. DISTURBANCE OF INTESTINAL MICROBIOTA IN BD

Recent researches have taken an increasing focus on the microbiota‐gut‐brain (MGB) axis regulation in neuropsychiatric diseases. 19 On the one hand, microorganisms inhabiting in the intestine, such as bacteria, fungi, viruses and bacteriophages, can synthesize and release various metabolites, including small molecule hormones, inflammatory mediators, neurotransmitters and short‐chain fatty acids, which send ascending signals to the brain through the endocrine, immune and vagus nerve pathways. 19 Notably, the vagal transmission from the gut to the brain influences monoaminergic systems and is crucial for various bodily functions, such as mood regulation and immune response. 20 , 21 The vagus nerve plays as an immune modulator of intestinal homeostasis via three different approaches, including the hypothalamus‐pituitary‐adrenal (HPA) axis, the splenic sympathetic anti‐inflammatory and the cholinergic anti‐inflammatory pathways. 20 Therefore, although the vagal transmission may not directly influence the expression of TRANK1, its regulation on the intestinal immune responses may link gut microbes to host gene expression. On the other hand, stress in particular, along with other factors, such as diet choice and the HPA regulation, represents up‐to‐bottom regulation of the gut microbiota. 19 , 22 The bidirectional communication of the MGB axis is now considered to play an important role in maintaining physical and mental well‐being. 22 , 23

Preliminary studies have shown that the diversity and structure of the intestinal microbiota of BD patients are different from that of healthy individuals. 24 , 25 A previous study has reported that the faecal abundance of Faecalibacterium and Ruminococcaceae decreased in the BD patients, and the abundance of Faecalibacterium was negatively correlated with the severity of depression. 24 The diversity of gut microbiota in BD patients is negatively correlated with the course of the disease. The abundance of Actinobacteria and Coriobacteria in the intestine was increased, and the abundance of Lactobacillus was positively correlated with serum IL‐6, lipid, tryptophan levels and other indicators. 25 In recent years, our research team has also shown great interest in gut microbiota and has carried out a serious of studies to investigate its characteristics in depressed patients. Using 16sRNA sequencing, we reported gut microbial changes in diversity and compositions in BD depression. 26 Compared with healthy controls, untreated depressed BD patients showed decreased diversity in gut microbiota and reduced abundance of butyrate‐producing bacteria, 26 which may foster systemic inflammation in BD patients. 27 Based on specific bacterial operational taxonomic units, microbial markers could be established to distinguish depressed BD patients from healthy controls and predict one‐month treatment outcome of quetiapine monotherapy. 26 Moreover, we reported gut microbiol signatures can effectively distinguish unipolar and bipolar patients during depressive episodes. 28 In addition, we have systematically reviewed the research advances on gut microbiota in mood disorders and have proposed future research directions in this field. 27 , 29 , 30 Given the limited number of studies, small to moderate sample sizes, different ethnicity and regions, uncontrolled clinical characteristics and medications across studies, findings in these studies have both similarities and differences, and thus should be interpreted carefully.

Above research results suggest that the disturbance of intestinal microbiota may be an important environmental factor in the onset of BD. However, it is still unclear how the gut microbiota affects the MGB axis, which in turn leads to abnormal mood and behaviour in BD individuals.

4. IMPAIRED BLOOD‐BRAIN BARRIER FUNCTION IN BD

The BBB is an important barrier for the exchange of substances and nutrients between the peripheral circulation and the central nervous system (CNS) and plays a key role in maintaining normal physiological functions of the brain. 31 Previous studies have suggested that oxidative stress and chronic inflammation also exist in patients with BD, which may lead to the destruction of the integrity of the BBB, but the specific pathological mechanism remains unclear. 32 A recent study has shown that in BD patients with manic episodes or remission, the levels of claudin‐5 and zonulin in peripheral blood were increased. 33 Using qRT‐PCR and immunohistochemistry, another study reported that the expression of claudin‐5, a tight junction protein, was reduced in the hippocampus of individuals diagnosed with major psychiatric disorders and was correlated with disease duration and age at onset. 34 In addition, blood levels of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 (ICAM‐1), a transmembrane glycoprotein, were elevated in BD patients in a state‐independent pattern. 35 Higher soluble ICAM‐1 seems to be associated with altered permeability of the BBB. Thus, these preliminary studies indicated that the integrity of BBB in BD patients was damaged. Impaired BBB function in BD patients was also verified by contrast‐enhanced dynamic MRI scanning for quantitative assessment of BBB leakage, which was associated with more severe symptoms of depression and anxiety and longer course of illness. 36

In recent years, studies have reported the influence of metabolites of intestinal microbiota on the BBB function, which may act as a protective or detrimental factor under different conditions. 37 , 38 In germ‐free mice, the expression of the tight junction proteins, occludin and claudin‐5, was lower compared with those with a normal glora. Germ‐free adult mice exposed to gut microbiota from pathogen‐free mice can reverse the increased BBB permeability and up‐regulate the expression of tight junction proteins. 39 In addition, propionate produced by bacterial metabolism can reduce the damage caused by oxidative stress to BBB through a CD14 cell‐dependent mechanism. 40 While in patients with multiple sclerosis, the interaction between the disturbed intestinal microbiota and the BBB can even affect the course of disease. 37 In adult rhesus monkeys, antibiotic treatment caused changes in gut microbial compositions, especially a decrease in acetic acid‐ and propionic acid‐producing phyla and genera, accompanied by the increase in BBB permeability. 41 Intestinal microorganisms can produce a variety of microbial‐associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), such as bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), lipoprotein and double‐stranded RNA. On the one hand, as a result of the "leaky gut", LPS produced by the intestinal microbiota can enter the blood circulation through the intestinal mucosal barrier, and interact with the Toll‐like receptor 4 (TLR4) on the surface of immune cells, such as peripheral macrophages and neutrophils, activating the downstream signalling pathway of TLR4 and releasing inflammatory factors including IL‐1β, IL‐6 and TNF‐α. These inflammatory factors can enter the CNS through the compromised BBB. On the other hand, as a result of the impaired BBB function in BD patients, LPS in the blood circulation can also directly penetrate the BBB and bind to the TLR4 on the surface of microglia, which then activates the neuroinflammation process in the CNS. 42 A recent published study showed that the levels of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in the brain of TLR4 knockout mice were significantly alleviated, suggesting that the inhibition of the LPS‐TLR4 signalling pathway could be an alternative strategy to alleviate gut microbiota‐associated neuroinflammation. 43 Therefore, changes in diversity and compositions of gut microbiota, and even its metabolome, may serve as underlying source for both systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation.

Notably, mounting evidence has confirmed the close relationship between BD and immune dysfunction. 44 BD immunology is an evolving field concerning non‐infectious inflammatory alterations in the peripheral and CNS. 44 In a previous study, we reported elevated serum IL‐6 levels in depressed BD patients, accompanied with abnormalities in T‐cell sub‐populations. 45 Other pro‐inflammatory cytokines including TNF‐α, soluble TNF‐type 1 receptor, IL‐2 receptor, IL‐1β and C‐reactive protein were also elevated in patients with acute depressive or manic episodes. 44 , 46 When the pro‐inflammatory messages enter into the CNS, brain microglia is activated and induces neuroinflammtion. Under inflammatory conditions, the metabolic process of kynurenine turns towards the neurotoxic quinolinic acid pathway rather than the neuroprotective kynurenic acid pathway, 30 thus disrupting the neural growth and neurotransmitter production, and contributing to the abnormalities in mood and behaviours.

Taken together, the above findings indicate that intestinal dysbiosis may be related to the impairment of BBB integrity. BBB dysfunction facilitates the entrance of peripheral inflammatory mediators into the CNS, thus promoting neuroimmune response and participating in the occurrence and development of BD.

5. INTESTINAL MICROBIOTA REGULATE TRANK1 EXPRESSION VIA TYPE 1 IFN SIGNALLING

The interaction between microorganisms and host genome has been designated as one of the major research directions of the Human Microbiology Project. 47 Intestinal microbes are involved in the regulation of host development and physiological processes, including the formation of various organs, energy metabolism and host immune response. 48 However, disturbances of the intestinal microbiota may also participate in the occurrence and development of diseases by affecting the expression of host genes. 49 , 50 For example, the complex interaction between the host genome and the intestinal microbiota may affect the age of onset and clinical manifestations of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. 49 In BD patients, it was also found that the diversity of intestinal commensal bacteria was negatively correlated with the methylation level of cg05733463 on the biological clock gene ARNTL. 50 However, few studies have ever explored the relationships between gut microbiota and susceptibility genes of BD.

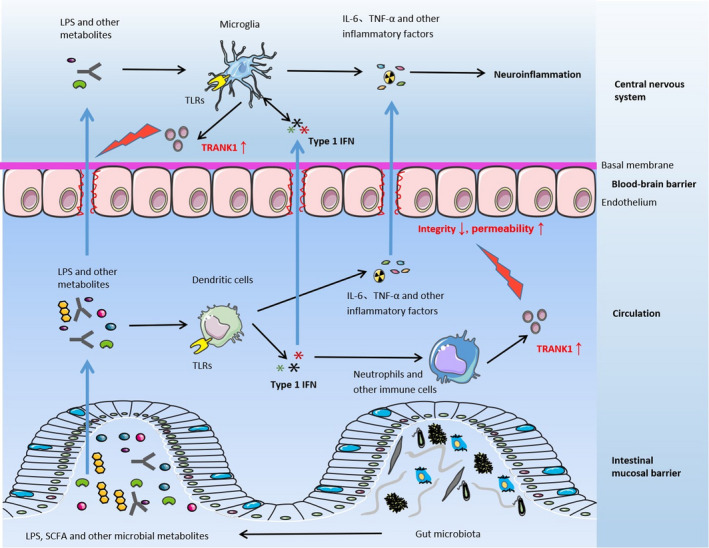

In addition to the regulatory role of gut microbiota on pro‐inflammatory factors, such as IL‐1β, IL‐6 and TNF‐α, type 1 IFN pathway is also modulated by the signals from the commensal micriobiota. 51 As a pleiotropic family of cytokines, type 1 IFN plays as a critical mediator of host immune response to intestine‐derived antigens, including bacteria and virus. 51 However, only some specific bacterial strains have been confirmed to induce type 1 IFN production in vitro studies. 52 , 53 Double‐stranded RNA from the intestinal lactic acid bacteria triggered IFN‐β production from murine bone marrow‐derived dendritic cells (DCs) via a TLR3‐dependent pathway. 52 Two specific L acidophilus strains, rather than other probiotic strains, were able to induce IFN‐β production from murine bone‐marrow‐derived DCs in a TLR2‐dependent manner, 53 which could be inhibited by Bifidobacterium bifidum. 54 In mice deficient in autophagy proteins, responses to intestinal bacterial pathogen Citrobacter rodentium were enhanced by type 1 IFN‐dependent signalling. 55 Interestingly, a fungus, Debaryomyces hansenii, was found to impair mucosal healing in Crohn's disease intestinal tissue through the myeloid‐specific type 1 IFN‐CCL5 pathway. 56 Moreover, type 1 IFN signalling was involved in prostaglandin E2‐induced intestinal inflammation via disrupting the microbiota‐regulatory T‐cell communication. 57 Therefore, the type 1 IFN signalling pathway manifests as an important coordinator of human immune response to the intestinal microbiota. As shown in previous studies, type 1 IFN signalling is sufficient to induce the expression of TRANK1 gene. 16 , 17 Overexpression of TRANK1 was associated with impaired BBB function, as revealed by increased levels of MMP9 and PV‐1. 18 These findings together indicate that gut microbiota‐dependent type 1 IFN signalling may up‐regulate the expression of TRANK1 and further damaged the integrity of the BBB, thus increasing its permeability and exacerbating the neuroinflammatory basis of BD (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Gut microbiota‐dependent type 1 IFN signalling induces TRANK1 expression and BBB impairment. Compared with healthy individuals, the diversity and compositions of the intestinal microbiota of BD patients is altered. Various metabolites produced by the commensal microbiota, such as bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), short‐chain fatty acids (SFCA) and other metabolites, can enter the peripheral circulation through the intestinal mucosal barrier. Circulating bacterial antigens, such as LPS, are recognized by the Toll‐like receptors on the surface of dendritic cells and stimulate the release of cytokines including type 1 IFN, IL‐6, TNF‐α and other inflammatory mediators. Type 1 IFN stimulates neutrophils and other immune cells to synthesize and secrete TRANK1 protein. TRANK1 protein in the peripheral circulation acts on the BBB, resulting in decreased integrity and increased permeability of the BBB. Various inflammatory mediators are more easily to enter the central nervous system and activate microglia to induce neuroinflammation, which is involved in the pathogenesis of BD

6. CONCLUDING REMARKS

Despite advances in biotechnology, the underlying pathogenesis of BD remains a mystery. A series of susceptibility genes of BD have been identified, but the exact functions of these genes have been rarely claimed. In this brief review, we provide a new perspective to investigate the role of these genes by paying special attention to TRANK1 and its interaction with human intestine microbiota, which is also recognized as a critical environmental factor for human health. 58 The immune pathway is an important approach that the gut and the brain communicate bidirectionally. Indeed, the peripheral inflammation and neuroinflammation in the CNS is a distinguished hallmark of BD and may have a close relationship with the gut microbial compositional alterations. Increasing evidence has revealed that gut microbiota can regulate local and systemic inflammation via the type 1 IFN signalling. Herein, we propose that the gut mircobiota‐derived type 1 IFN signalling is essential in regulating the host expression of TRANK1 gene, which participates in the destruction of BBB integrity and facilitates CNS inflammatory processes. Over‐activated neuroinflammation thereby promotes the occurrence and development of BD.

More evidence is needed to confirm this speculation mechanistically. For example, germ‐free mice receiving faecal microbiota transplantation from critically ill BD patients should be constructed to verify the disease‐like phenotypes, inflammatory status, expression level of TRANK1 and markers of impaired BBB. Whether inhibition of the type 1 IFN signalling can down‐regulate the expression of TRANK1 and protect the BBB integrity remains to be studied. In human tissues, although up‐regulated expression of TRANK1 in postmortem brain from BD patients has been observed, 13 the expression level of TRANK1 in the peripheral circulation also needs to be explored. Researches in TRANK1 knockout animals can help to elucidate the gene function and its interaction with the gut microbiota.

Overall, it is intriguing that if the expression of bipolar susceptibility genes can be regulated by targeting the gut microbiota, microorganism‐derived metabolites or downstream type 1 IFN signalling pathway. Better understanding the role of gut microbiota in human health and diseases helps to elucidate the pathogenesis of BD and provides novel treatment strategies.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jianbo Lai: Conceptualization (lead); Writing‐original draft (lead). Jiajun Jiang: Conceptualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal). Peifen Zhang: Conceptualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal). Caixi Xi: Conceptualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal). Lingling Wu: Conceptualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal). Xingle Gao: Conceptualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal). Yaoyang Fu: Conceptualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal). Danhua Zhang: Conceptualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal). Yiqing Chen: Conceptualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal). Huimin Huang: Conceptualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal). Yiyi Zhu: Conceptualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (equal). Shaohua Hu: Conceptualization (lead); Supervision (lead); Writing‐review & editing (lead).

Lai J, Jiang J, Zhang P, et al. Impaired blood‐brain barrier in the microbiota‐gut‐brain axis: Potential role of bipolar susceptibility gene TRANK1 . J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25:6463–6469. 10.1111/jcmm.16611

Jianbo Lai and Jiajun Jiang contributed equally to this work.

Funding information

This study was partly supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: 81971271), the Zhejiang Provincial Key Research and Development Program (Grant number: 2021C03107), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant number: LQ20H090013) and the Program from the Health and Family Planning Commission of Zhejiang Province (Grant number: 2020KY548).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable – no new data generated.

REFERENCES

- 1. Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:241‐251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Webb RT, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Geddes JR, Fazel S. Suicide, hospital‐presenting suicide attempts, and criminality in bipolar disorder: examination of risk for multiple adverse outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:e809‐e816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bauer M, Andreassen OA, Geddes JR, et al. Areas of uncertainties and unmet needs in bipolar disorders: clinical and research perspectives. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(11):930‐939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vieta E, Berk M, Schulze TG, et al. Bipolar disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McGuffin P, Rijsdijk F, Andrew M, Sham P, Katz R, Cardno A. The heritability of bipolar affective disorder and the genetic relationship to unipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(5):497‐502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Edvardsen J, Torgersen S, Røysamb E, et al. Heritability of bipolar spectrum disorders. Unity or heterogeneity? J Affect Disord. 2008;106(3):229‐240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hu SH, Han YQ, Mou TT, et al. Association of genetic polymorphisms with age at onset in Han Chinese patients with bipolar disorder. Neurosci Bull. 2019;35(4):591‐594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hou L, Bergen SE, Akula N, et al. Genome‐wide association study of 40,000 individuals identifies two novel loci associated with bipolar disorder. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(15):3383‐3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mühleisen TW, Leber M, Schulze TG, et al. Genome‐wide association study reveals two new risk loci for bipolar disorder. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ikeda M, Takahashi A, Kamatani Y, et al. A genome‐wide association study identifies two novel susceptibility loci and trans population polygenicity associated with bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(3):639‐647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li W, Cai X, Li HJ, et al. Independent replications and integrative analyses confirm TRANK1 as a susceptibility gene for bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46(6):1103‐1112. 10.1038/s41386-020-00788-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moore PM, Vo T, Carlock LR. Identification and cloning of a brain autoantigen in neuro‐behavioral SLE. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;82:116‐125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gandal MJ, Zhang P, Hadjimichael E, et al. Transcriptome‐wide isoform‐level dysregulation in ASD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Science. 2018;362(6420):eaat8127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Whelan R, St Clair D, Mustard CJ, Hallford P, Wei J. Study of novel autoantibodies in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1341‐1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ambati A, Hillary R, Leu‐Semenescu S, et al. Kleine‐Levin syndrome is associated with birth difficulties and genetic variants in the TRANK1 gene loci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(12):e2005753118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim TH, Zhou H. Functional analysis of chicken IRF7 in response to dsRNA analog poly(I:C) by integrating overexpression and knockdown. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Irudayam JI, Contreras D, Spurka L, et al. Characterization of type I interferon pathway during hepatic differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells and hepatitis C virus infection. Stem Cell Res. 2015;15:354‐364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schiavone S, Mhillaj E, Neri M, et al. Early loss of blood‐brain barrier integrity precedes NOX2 elevation in the prefrontal cortex of an animal model of psychosis. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(3):2031‐2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cryan JF, O'Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, et al. The microbiota‐gut‐brain axis. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(4):1877‐2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Breit S, Kupferberg A, Rogler G, Hasler G. Vagus nerve as modulator of the brain‐gut axis in psychiatric and inflammatory disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Munshi S. A depressed gut makes for a depressed brain via vagal transmission. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;S0889–1591(21):00119‐00127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Burokas A, Moloney RD, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Microbiota regulation of the Mammalian gut‐brain axis. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2015;91:1‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pennisi E. Gut bacteria linked to mental well‐being and depression. Science. 2019;363(6427):569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Evans SJ, Bassis CM, Hein R, et al. The gut microbiome composition associates with bipolar disorder and illness severity. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;87:23‐29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Painold A, Mörkl S, Kashofer K, et al. A step ahead: Exploring the gut microbiota in inpatients with bipolar disorder during a depressive episode. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(1):40‐49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hu S, Li A, Huang T, et al. Gut microbiota changes in patients with bipolar depression. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2019;6(14):1900752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zheng P, Yang J, Li Y, et al. Gut microbial signatures can discriminate unipolar from bipolar depression. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2020;7(7):1902862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang TT, Lai JB, Du YL, Xu Y, Ruan LM, Hu SH. Current understanding of gut microbiota in mood disorders: an update of human studies. Front Genet. 2019;10:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lai J, Jiang J, Zhang P, et al. Gut microbial clues to bipolar disorder: State‐of‐the‐art review of current findings and future directions. Clin Transl Med. 2020;10(4):e146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sublette ME, Cheung S, Lieberman E, et al. Bipolar disorder and the gut microbiome: a systematic review. Bipolar Disord. 2021. 10.1111/bdi.13049. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zlokovic BV. The blood‐brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 2008;57(2):178‐201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patel JP, Frey BN. Disruption in the Blood‐Brain Barrier: The Missing Link between Brain and Body Inflammation in Bipolar Disorder? Neural Plast. 2015;2015:708306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kılıç F, Işık Ü, Demirdaş A, Doğuç DK, Bozkurt M. Serum zonulin and claudin‐5 levels in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2020;266:37‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Greene C, Hanley N, Campbell M. Blood‐brain barrier associated tight junction disruption is a hallmark feature of major psychiatric disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Müller N. The role of intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 in the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kamintsky L, Cairns KA, Veksler R, et al. Blood‐brain barrier imaging as a potential biomarker for bipolar disorder progression. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;26:102049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Alvarez JI, Cayrol R, Prat A. Disruption of central nervous system barriers in multiple sclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812(2):252‐264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Logsdon AF, Erickson MA, Rhea EM, Salameh TS, Banks WA. Gut reactions: how the blood‐brain barrier connects the microbiome and the brain. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2018;243(2):159‐165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Braniste V, Al‐Asmakh M, Kowal C, et al. The gut microbiota influences blood‐brain barrier permeability in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(263):263ra158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hoyles L, Snelling T, Umlai UK, et al. Microbiome‐host systems interactions: protective effects of propionate upon the blood‐brain barrier. Microbiome. 2018;6(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wu Q, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, et al. Potential effects of antibiotic‐induced gut microbiome alteration on blood‐brain barrier permeability compromise in rhesus monkeys. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1470(1):14‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sampson TR, Mazmanian SK. Control of brain development, function, and behavior by the microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17(5):565‐576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Perez‐Pardo P, Dodiya HB, Engen PA, et al. Role of TLR4 in the gut‐brain axis in Parkinson's disease: a translational study from men to mice. Gut. 2019;68(5):829‐843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fries GR, Walss‐Bass C, Bauer ME, Teixeira AL. Revisiting inflammation in bipolar disorder. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2019;177:12‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wu W, Zheng YL, Tian LP, et al. Circulating T lymphocyte subsets, cytokines, and immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with bipolar II or major depression: a preliminary study. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Horsdal HT, Köhler‐Forsberg O, Benros ME, Gasse C. C‐reactive protein and white blood cell levels in schizophrenia, bipolar disorders and depression ‐ associations with mortality and psychiatric outcomes: a population‐based study. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;44:164‐172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Integrative HMP (iHMP) Research Network Consortium . The Integrative Human Microbiome Project: dynamic analysis of microbiome‐host omics profiles during periods of human health and disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16(3):276‐289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sommer F, Bäckhed F. The gut microbiota–masters of host development and physiology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11(4):227‐238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Imhann F, Vich Vila A, Bonder MJ, et al. Interplay of host genetics and gut microbiota underlying the onset and clinical presentation of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2018;67(1):108‐119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Patrignani P, Tacconelli S, Bruno A. Gut microbiota, host gene expression, and aging. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(Suppl 1):S28‐S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bengesser SA, Mörkl S, Painold A, et al. Epigenetics of the molecular clock and bacterial diversity in bipolar disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;101:160‐166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kawashima T, Kosaka A, Yan H, et al. Double‐stranded RNA of intestinal commensal but not pathogenic bacteria triggers production of protective interferon‐β. Immunity. 2013;38(6):1187‐1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Weiss G, Rasmussen S, Zeuthen LH, et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus induces virus immune defence genes in murine dendritic cells by a Toll‐like receptor‐2‐dependent mechanism. Immunology. 2010;131(2):268‐281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Weiss G, Rasmussen S, Nielsen Fink L, Jarmer H, Nøhr Nielsen B, Frøkiaer H. Bifidobacterium bifidum actively changes the gene expression profile induced by Lactobacillus acidophilus in murine dendritic cells. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Martin PK, Marchiando A, Xu R, et al. Autophagy proteins suppress protective type I interferon signalling in response to the murine gut microbiota. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3(10):1131‐1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jain U, Ver Heul AM, Xiong S, et al. Debaryomyces is enriched in Crohn's disease intestinal tissue and impairs healing in mice. Science. 2021;371(6534):1154‐1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Crittenden S, Goepp M, Pollock J, et al. Prostaglandin E2 promotes intestinal inflammation via inhibiting microbiota‐dependent regulatory T cells. Sci Adv. 2021;7(7):eabd7954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kataoka K. The intestinal microbiota and its role in human health and disease. J Med Invest. 2016;63(1–2):27‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable – no new data generated.