Abstract

Introduction

Despite learning health systems' focus on improvement in health outcomes, inequities in outcomes remain deep and persistent. To achieve and sustain health equity, it is critical that learning health systems (LHS) adapt and function in ways that directly prioritize equity.

Methods

We present guidance, including seven core practices, borne from theory, evidence, and experience, for actors within LHS pursuing equity.

Results

We provide a foundational definition of equity. We then offer seven core practices for how LHS may effectively pursue equity in health: establish principle, measure for equity, lead from lived experience, co‐produce, redistribute power, practice a growth mindset, and engage beyond the healthcare system. We include three use cases that illustrate ways in which we have begun to center equity in the work of our own LHS.

Conclusion

The achievement of equity requires real transformation at individual, institutional, and structural levels and requires sustained and persistent effort.

Keywords: co‐production, health equity, improvement science, learning networks, population health, social determinants of health

1. BRIEF INTRODUCTION

The original description of learning health systems from the Institute of Medicine focused on their use to improve outcomes across a range of health conditions. 1 Yet inequities in health outcomes across such conditions remain deep and persistent. To achieve and sustain health equity, it is critical that learning health systems adapt and function in ways that directly prioritize equity as a health outcome.

We present guidance, borne from theory, evidence, and experience, for actors within learning health systems to consider when initiating or furthering this pursuit of equity. We begin by anchoring in a shared definition of equity. We then offer seven practices for how learning health systems may effectively pursue equity in health. As we present these practices, we describe ways to embed equity within the necessary improvement work. To support the guidance provided, we include three use cases that illustrate ways in which we have begun to center equity in the work of our own learning health system. Importantly, we share our current thinking with humility, recognizing that we are all on a pathway toward deeper understanding, better execution, and greater realization of equity.

2. SHARED DEFINITION OF EQUITY

Equity is predicated on the ethical principle of distributive justice 2 ; one that requires our decisions regarding the allocation of resources, benefits, and burdens across society be informed by the social conditions of individuals and communities. 3 Health equity—the absence of socially unjust, unfair, and avoidable health disparities 4 —cannot be achieved without an understanding of what produces and perpetuates equity gaps. The root causes of inequity are complex. Laws and policies form the building blocks of interwoven social, political, economic, and medical systems that confer advantage or disadvantage to groups of individuals within a society. 3 As a result, inequitable systems disenfranchise individuals and communities—a reality made most apparent in the form of racism and differential exposure to other social determinants of health (SDOH). For example, Black, Latinx, and Native American people disproportionately experience poverty, housing insecurity, and food insecurity. They are more likely to live in neighborhoods branded by the history of red‐lining, 5 marred by disinvestment, and left unprotected from environmental hazards and disasters. 6 , 7 Not surprisingly, these marginalized populations experience differential health outcomes across age groups and diagnoses that are unequal, inequitable, and unjust. A state of equity can only be achieved through an intentional, coordinated, and multifaceted approach that disassembles inequitable systems while reimagining and co‐creating equitable ones with those who are most impacted by the inequities.

Learning health systems are networks that aim to transform health and healthcare via evidence‐based knowledge generation, data transparency, stakeholder engagement, and quality improvement. 8 They are well suited to pursue equity in health because they create the opportunity for patients, healthcare professionals, researchers, and other stakeholders to come together as a community, utilize population‐level data, and drive rapid learning. 9 , 10 , 11 Strong partnerships with patients, community members, and community organizations provide an opportunity to understand the impact of structural factors—such as those rooted in racist policies and systems—on a range of SDOH. This is particularly important as the majority of equity gaps are tied to systems external to healthcare, 10 systems that influence the labor force, housing, and social services. Thus, we will discuss ways in which actors, both internal and external to health systems, must lead and be engaged to work together in learning health systems in pursuit of equity. Ultimately, actors in a learning health system will include those who work for the health system, those who partner with the health system, and those who are patients of the health system.

3. PRACTICES FOR PURSUING EQUITY THROUGH A LEARNING HEALTH SYSTEM

To be successful in the deeply difficult yet necessary endeavor of pursuing, achieving, and sustaining equity, a learning health system must adapt its targeted outcomes, internal processes, and structure. 12 , 13 Herein, we offer seven core practices vital to this pursuit that can map to these areas of outcomes (practices 1 and 2), processes (practices 3, 4, and 5), and structure (practices 6 and 7) 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 :

| Seven Core Practices for the Pursuit of Equity through a Learning Health System |

| Establish principle. Position equity as an essential focus of the learning health system |

| Measure for equity. Track data that matter to drive and sustain success |

| Lead from lived experience. Ensure people with lived experience are leading the work |

| Co‐produce. Design, create, learn, act, and sustain together |

| Redistribute power. Reallocate power and leadership across the system |

| Practice a growth mindset. Cultivate an environment and expectation for growth |

| Engage beyond the healthcare system. Catalyze change across systems that produce health |

3.1. PRACTICE 1: Establish principle

To achieve and sustain equity, a learning health system needs to position equity as an essential guiding focus. 18 Equity will be pursued as a primary outcome of the system with actors within the learning health system aligned, committed, and resourced to achieve equity, even when faced with the inertia of the status quo.

A learning health system should commit in its stated principles to being driven by equity. As one example of this practice, the first stated principle of the All Children Thrive Learning Network in Cincinnati, OH reads:

Equity is foundational to improving children's health. We believe that financial, social, environmental, and racial inequities affect the health and well being of children. Solutions must address basic needs of families first. 19

As a second example, the 100 Million Healthier Lives initiative convened by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement asserted from its inception “equity is the price of admission,” further stating:

We are committed to working to achieve the conditions in which all people have the opportunity to attain their highest possible level of health and wellbeing, removing barriers that prevent them from doing so. This commitment stems from three sources: 1) a recognition that it is not possible to achieve the health outcomes we seek as a country without addressing equity; 2) a recognition of the tremendous waste in human potential that results from inequity; and 3) a belief in our interconnectedness and common opportunity and destiny. 20

A critical step to positioning equity as a primary outcome of the system is defining what equity, when achieved, will look like. In this, the actors within the learning health system will intentionally identify equity gaps and set explicit aims to narrow or eliminate these gaps. Equity gaps occur when one subpopulation is systematically disadvantaged or experiencing a worse outcome in comparison to another subpopulation due to different positions in a social hierarchy. 3 In the United States, these gaps exist across groups defined by the social constructs of race and ethnicity. 21 Gaps also extend to other sociodemographic characteristics, including by language and socioeconomic status.

Equity gaps are ubiquitous in health and healthcare—some readily apparent, while others are more hidden. In our own learning health system, we examine a range of child health outcomes stratified by socially constructed factors like race and ethnicity 21 as well as language and neighborhood poverty. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 In doing so, we seek to illuminate—in order to eliminate—gaps that emerge from racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic oppression or exclusion. As we have built such an approach, we have identified a range of outcome gaps. For example, Black children experience higher hospitalization rates across a range of diagnoses. As another example, children living in higher poverty neighborhoods experience a disproportionate number of inpatient bed‐days across conditions. 25 Gaps such as these would have been masked as we only considered the overall count or average and not assessed such measures stratified by these sociodemographic characteristics. Once gaps are identified, the work of narrowing and eliminating those gaps can begin.

3.2. PRACTICE 2: Measure for equity

In the pursuit of equity, a learning health system needs to adopt an approach that embeds measures for equity throughout its improvement efforts—the outcomes to be achieved, processes to be transformed, and balancing measures to be minded. The learning health system must also incorporate measures that assess the very means through which the pursuit of equity is being done (ie, how the learning health system does its work).

This measurement approach will guide, inform, and assess improvement efforts aimed at eliminating equity gaps. While aims are strengthened when they are made specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time‐bound, 27 they are further strengthened when informed by those who have been directly impacted by the inequity. 28 Learning health systems would also benefit from prioritizing measures that are meaningful to those experiencing inequities. Indeed, learning health system‐driven efforts will benefit from the inclusion of person‐centered measures that center, elevate, and empower the voice of those experiencing inequities, including holistic, positively framed, strengths‐based measures like those of well‐being and its drivers. 29 , 30 , 31

Enacting a measurement approach often involves leveraging accessible and reliable data to define and then track equity gaps over time. In this, we offer an essential caution about how data can become sources of bias, particularly in equity work. For example, learning health systems often collect, track, and analyze data on race and ethnicity. Those who collect such data, however, need to recognize that “race” is not a biological entity but rather a social construct with sociopolitical implications. 21 , 32 Therefore, disparities in outcomes stratified by race, ethnicity, and language most likely result from racism and other systems of oppression and exclusion. Though it is important to collect these data and stratify based on the social constructs of race and ethnicity to identify gaps in equity, variations in outcomes should be considered with this frame in mind. Further, variations are likely to be narrowed only by dismantling those systems of oppression and exclusion. As such, it is essential that learning health systems are mindful in how they think about and respond to their data.

We now offer an example of our local work that demonstrates one way in which we applied the core practice of measuring for equity. Several other core practices essential to this work are also highlighted in this use case.

| Use Case 1. Closing equity gaps experienced by children with type 1 diabetes |

|

The Diabetes Center at Cincinnati Children's Hospital cares for nearly all children with type 1 diabetes (T1D) in the Greater Cincinnati region. T1D is the third most common pediatric chronic disease affecting children across all ages. Recent data, both local and national, suggest that significant and persistent equity gaps characterize T1D morbidity. These trends likely mirror those seen in other chronic disease and parallel the rise in T1D incidence in racial/ethnic minority groups. 33 Although successful treatment with insulin can curtail morbidity and mortality, T1D management is complicated; made even more complex by nonmedical barriers (eg, structural barriers such as racism and adverse social determinants of health) that affect care delivery and susceptibility to complications. Thus, as a first step, to identify and define an equity gap in our setting, the Diabetes Center extracted data from the Cincinnati Children's T1D clinical registry, which includes all patients with T1D seen at our center. The Diabetes Center team saw significant, notable variation in measures like HbA1c, emergency department visits, and likelihood of admission for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) by both race and neighborhood poverty. With a gap identified, Diabetes Center staff assembled an improvement team that then articulated an improvement aim. The SMART aim focused on reduction of emergency room visits among a cohort of children with T1D living in high poverty, high minority population neighborhoods. The improvement team started with approximately 20 patients within the Diabetes Center for whom disease control had proven difficult. A measurement approach was developed to track outcome, process, and balancing measures for patients during their care. The team used existing registries of patients within our electronic health record to identify patient addresses which were then linked to neighborhood variables, facilitating an evaluation of contextual factors that could potential widen (or narrow) equity gaps. The school each patient attended was identified so as to extend partnership not only with the patient and family but also with in‐school providers. An iterative approach to measurement with a delineated theory for change was depicted using a key driver diagram. Example drivers included: (1) a personalized, effective, and balanced patient‐centered treatment plan; (2) community resources leveraged to partner with families and the healthcare team; and (3) informed community prepared to support the patient and family. 34 , 35 With theory developed, the team moved into a testing phase. First, although care was provided by several professionals, including physicians, diabetes researchers, nurse practitioners, psychologists, certificated diabetes educators, registered nurses, medical assistants, and insurance advocates, the improvement team recognized the challenge of a lack of time meaningfully engaging with the patient and family. Thus, a dedicated community health worker (CHW) was employed to fill gaps between and within healthcare visits. 36 Second, the improvement team implemented a qualitative evaluation of patient perspectives of environmental, cultural, physical, emotional, community, and social factors in caregiving using CareMaps (https://atlasofcaregiving.com/). CareMaps are unique visual tools diagramming a patient's support systems providing insight into the patient's “ecosystem” of care. A critical step to outcome improvement and disparity reduction was thought to be the acknowledgement that most care is provided outside the clinic setting. A third testing example was the development of an innovation fund. Using biweekly patient case reviews, and data reports, it became apparent that financial resources were required to remove barriers faced by families. T1D care was often directly challenged by an array of competing priorities families faced. Therefore, the innovation fund was used to help families circumnavigate this range of barriers. Examples include provision of temporary hotel rooms to remove families from dangerous housing situations, ride arrangements for transportation to needed therapies and resources, emergency food vouchers, and funding for participation in diabetes‐related events such as diabetes camp. Through these equity‐oriented tests pursued to meet the stated SMART aim, and using the iterative and often nonlinear processes depicted in Figure 1, the improvement team is now seeing outcome improvements for this cohort of at‐risk patients. There is much to still learn, including how to move toward scale—more patients with T1D—and spread to other, similar conditions. |

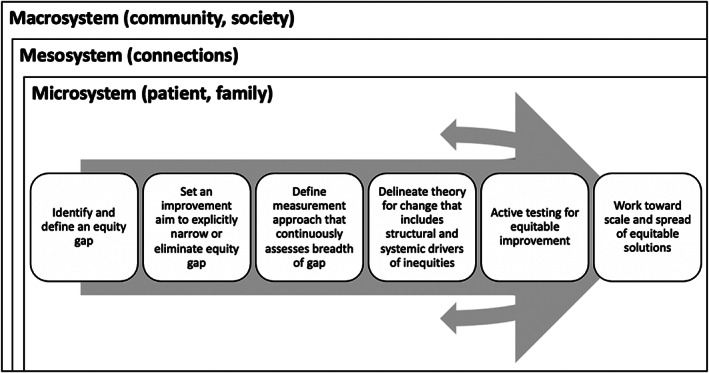

FIGURE 1.

The elements of equity‐centered improvement work in a learning health system

Foundational to the improvement work of learning health systems is the tenet that “every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets”. 37 To disassemble systems that have produced inequities, reimagine and create ones that produce equity, and overcome the inertia of the status quo along the way, learning health systems need to transform the people and processes through which the improvement work itself is done. To achieve and sustain equity, learning health systems need not only embed equity‐centric measurement across their learning and improvement work but also measure the ways in which they do their own internal learning and improvement work. For example, lack of diversity across teams and the influence of hierarchy may be important contributors to current state and therefore become key drivers for change. Measuring and tracking them could lead to transformative insights and improvement. Learning health systems may recognize that their pursuit of equity will be more successful if they not only address the outcome of how they work (eg, more diverse teams, more distributed leadership) but also interrogate and transform the practices or policies that resulted in current state (eg, recruitment and pipeline practices, culture around power). The actors in a learning health system can improve the diversity of their teams and also intentionally create an environment where newly introduced voices will be heard and amplified.

3.3. PRACTICE 3: Lead from lived experience

To achieve equity, it is vital that learning health systems ensure people with lived experience are leading the work. This requires that learning health systems intentionally include patients, families, and community members in the learning and improvement work, not as bystanders or informants but rather as designers and leaders.

People with lived experience are those who have experienced or are currently experiencing the problems the learning health system is seeking to address. 38 They can also be understood as the people who would have benefitted or would now benefit directly from the solutions or improvements being generated. 39 , 40 People with lived experience are most often those who have been marginalized and bear the burden of disadvantage, adversity, and poorer outcomes. People with lived experience provide essential expertise to inform the system's learning and improvement work and leaning on their expertise aligns with the principles of design justice—which is both procedural and distributive. 39 They can propose and evaluate potential solutions from a place of having experienced the system—and how the system advantages others—thereby bringing unique knowledge about what works, what does not work, what already exists, and what does not yet exist. 38 , 39 Also, people with lived experiences display vulnerability by sharing their personal stories; their contributions need to be honored with deep, respectful listening that leads to immediate, responsive action.

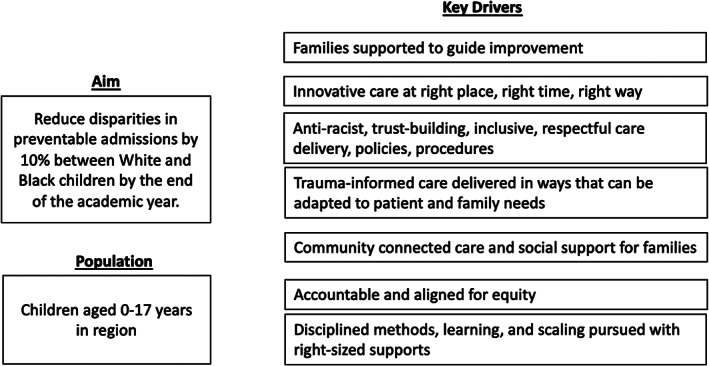

Crucially, the pursuit of equity requires identification of and intervention on the contextual factors that contribute to the creation, maintenance, and worsening of defined equity gaps—the structural and systemic drivers at the root of inequities. To uncover these root causes, it is essential to elucidate if and how the healthcare system has contributed to the creation and sustainment of specific equity gaps. We cannot fully understand and address existing inequities without recognizing and naming how systems, including and beyond the learning health system, advantage some above others. Building a theory for change that identifies these factors and that will lead to effective and efficient action requires the inclusion and leadership of people with lived experience of inequities (Figure 2). It requires time and intentional planning to make the necessary shifts within a learning health system to create an environment in which equitable partnering occurs, as new leaders are embedded within the learning health system, including those with lived experience. As learning health systems work to create, iterate, and improve their theory for change, we suggest they consider:

What can we do to center and amplify the voices of marginalized people and communities in the learning and improvement (eg, include people with lived experience of inequities in the improvement work from the early design phase)?

What can we do to learn from the lived experience of marginalized people and embed that wisdom in the theory of change or improvement?

How do we support historically marginalized populations when they do share lived experience? How do we honor what they are telling us as more than data/strategy?

How do we demonstrate our trustworthiness to communities who have been historically excluded, oppressed, and marginalized?

What is the current state of existing laws, policies, and other procedures? Do they enable the narrowing of gaps or do they widen them, even if unintentionally?

What are the pathways through which existing policies and procedures have enabled and currently enable the narrowing or widening of gaps, even if unintentionally?

What cross‐sector partnerships, new or existing, are needed to better address the social determinants of health that drive and exacerbate equity gaps?

Given the impact of the social determinants of health, what should we measure to drive change in social determinants necessary to achieving equity?

How do we listen and act in response to direct critiques of how our own healthcare system has contributed to inequities?

FIGURE 2.

Example key driver diagram for health equity work

3.4. PRACTICE 4: Co‐produce

To achieve equity, the learning and improvement work of a learning health system needs all actors actively working and learning together. 41 This co‐production will mean that actors within the learning health system will design, create, learn, act, and sustain together. As above in Practice 3, the learning and improvement process should not be restricted to select roles within the learning health system. Each actor in the learning health system brings unique perspectives and insights. Ideally, all of the actors relevant to the particular equity work will be involved across all phases of the work: identifying equity gaps, setting aims, defining measures that matter, delineating theory for change, testing for equitable improvement, and working toward scale and spread. 10 If a learning health system has not practiced co‐production, introducing the practice will represent a fundamental transformation in and of itself. To be done well, it will require that the actors in the learning health system do the challenging work of interrogating and changing the culture, practices, and policies that have guided how they have worked before.

Creating an environment that allows for the co‐production of aims, theory, and testable interventions requires trust, belief in the benefit of the work, and ongoing relationships invested in achieving the goals. 42 In evolving our learning health system, we have found that authentic co‐production also requires capacity building for everyone involved. As such, over time, we continue to change the way that we work. For example, we encourage individuals from within academia or the health system to communicate without the use of jargon; we strive for all individuals engaged in the work to define commonly used terms and acronyms together; we include discussion of historical context in our work; we strive to apply a strength‐based as opposed to a deficit‐based approach; we provide direct one‐on‐one support of patient, family, and community partners throughout the working relationship; and we ensure that in meetings, we take time for reflection and provide opportunities for vulnerability from all involved. Starting small and learning deeply is especially important early on in equity work. Building meaningful partnerships with shared goals and expectations requires care. The pace of initial partnership building can feel slow, especially when actors from within learning health systems are developing relationships within communities in which there is a long, deep history of being undervalued and disrespected by the healthcare system. As in any relationship, there will be missteps and failures along the way; acknowledging missteps and failures is uncomfortable but necessary.

A horizon scan for inequitable care practices may identify areas in which there is obvious opportunity for immediate change. In other areas, solutions may not be immediately clear. We expect that different drivers will be ready for testing at different times or scales. Indeed, there may be aspects of our work that are ready to change in clear, easy‐to‐conceptualize ways. Thus, starting small and learning deeply may help identify where meaningful solutions can be developed more quickly. That said, when working to address equity gaps, even small changes might require more effort and time than initially expected. For instance, before testing a new solution, it may be that old practices and old ways of thinking or behaving must be made apparent, challenged, and even undone. Such transformation in thinking and behaving, though essential, requires intention, vigilance, and perseverance in the face of challenge and resistance.

3.5. PRACTICE 5: Re‐distribute power

To achieve and sustain equity in a learning health system, power must be distributed across that system, with a particular focus on growing the leadership of those who experience the greatest burden of inequitable systems and poorer outcomes. Social hierarchies and the power differential that result from racism and other forms of systemic oppression cannot be overstated. Attempts to dismantle these hierarchies will be met with resistance in active and passive forms. As such, in this practice, the actors within a learning health system acknowledge and understand this reality. Then, those traditionally at the top of the hierarchy recognize the value and necessity of authentically sharing power in ways that increase the agency and leadership of people traditionally with less power, including those with lived experience of inequities. 43 In this, those traditionally at the top of the hierarchy need recognize that they may not have the essential expertise of people in other positions across the system and likely of those with lived experience. With power shared and leadership capacity increased across the system, the learning health system may be transformed in ways that achieve and then sustain equity, fueled by leadership from lived experience and co‐production that grows as‐of‐yet unimagined solutions and increases the numbers of engaged hearts and minds. 20

To enact this principle, the learning health system must intentionally center dialogue, decision‐making, and resource allocation on the pursuit of equity. 10 , 44 To do so will most likely require transforming—even dismantling and recreating the processes by which and the people with whom dialogue occurs, decision‐making happens, and resources are allocated. In our own work, we have come to appreciate the importance of love and kindness as essential components and drivers of the work. As an example, we name the potential discomfort associated with giving and receiving critical feedback but then recognize how pushing through that discomfort is an act of love; an investment in one another despite the discomfort of the process. We have also appreciated the value of measurement as a guide. Though early in our use of measurement in this aspect of the work, we are beginning to incorporate measures of co‐production, distributive leadership, and racial equity into our own learning health system work. 45 , 46

3.6. PRACTICE 6: Practice a growth mindset

To pursue equity, the learning health system needs to cultivate an environment that not only ensures safety for those who enter into the work but also produces creativity, innovation, and generosity. Such an environment is supported by actors within a learning health system operating from a position of curiosity and wonder, maintaining shared purpose at the center of the work and embracing failure as an opportunity to learn and adapt, among other behaviors. It can also be helpful to note that this kind of work, in which co‐production and distributed leadership are essential components, necessarily integrates across cultures. Indeed, the partnering of the academic team and the community team enables the creation of another culture, one that is inclusive of the skill, perspectives, and resources of both groups. 47 , 48 In this aspect of the work, we have learned to recognize how patient, family, and community partners have been, in the past, kept from roles in which they would inform and drive the work. Therefore, they may be hesitant to trust that their voices are wanted, valued, and will prompt helpful responses. We have learned that we must apply ourselves consistently and intentionally—still often with failure—to establishing an environment of love and kindness in which we all teach, all learn, and all lead.

It is necessary to recognize and appreciate that the pace of the work may be slower than expected when partnering with people and communities that have been historically undervalued and/or disrespected by the institution. 44 This has important implications for working toward scale. Starting small and learning deeply is necessary and important early work. Clarity from the start on what full scale would be is valuable so that attention to theory for scaling is also given its full due in the work (eg, scaling by geography, agency, and/or policy change). To that end, different projects require different scale plans. If efforts begin in one clinic, or one neighborhood, what would it take to work in 5 additional clinics or 5 other neighborhoods? What would be the same, and what would have to be designed in different ways to meet different needs? After 5, what would it take to get to 25? We have found that different aspects of our work scale faster than others, and that certain strategies are highly amenable to scale or spread while others need to be reconceptualized.

In Use Case 2, we provide a look at our early work in antiracism in which we have sought to co‐produce, redistribute power, and practice a growth mindset.

| Use Case 2. Initiating antiracism work within one learning network |

|

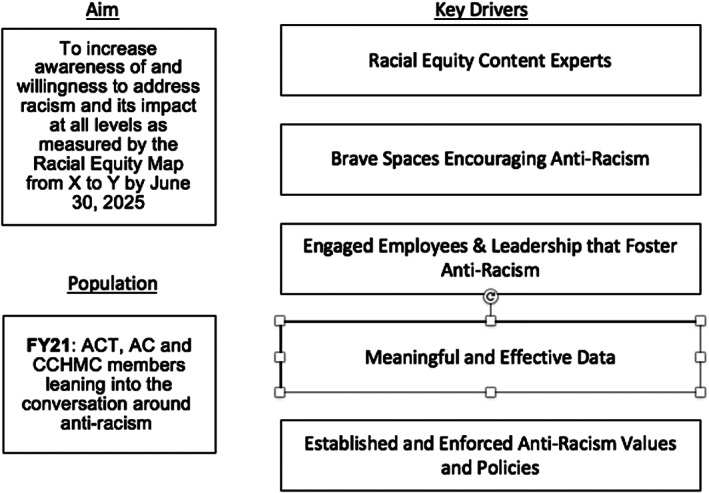

The All Children Thrive Learning Network in Cincinnati, OH (ACT) is a learning network launched by Cincinnati Children's Hospital (CCHMC) and more than 30 other organizations to apply the science of quality improvement to some of the toughest, most complex problems affecting community health. ACT convenes improvement teams including members of the healthcare system, community organizations, the public school system, and parents from the community. In Spring 2019, at the biannual learning session, a gathering of network members to accelerate progress of the improvement teams, those with lived experience, including parents, challenged all people present to recognize and meaningfully address the influence of racism in achieving the goals of every improvement team. This call to action served as a catalyst for the development of antiracism work within ACT. The antiracism team convened to initiate the antiracism effort, which included members of ACT who had expertise in Critical Race Theory and/or lived experience with racism. Prior to starting the antiracism work, the members of this team had many conversations about racism in general as well as how it impacted the goals that ACT is working to accomplish as well as our daily interactions at work. These conversations were opportunities to practice interrogating and naming their participation in and/or experiences with white supremacy, white privilege, and racism and increased the team's comfort in doing so. Supported by the call to action and this foundational relationship, the antiracism team established a global aim to create an antiracist environment within the ACT network and an initial SMART aim to increase awareness of and willingness to address racism at all levels of the organization as measured by the Racial Equity Map (REM) by June 30, 2021. The REM was developed by the Racial Equity Learning and Action Community as a measurement tool for organizations to identify their place on the racial equity journey, catalyze conversation, and identify actions steps to advance racial equity together. 49 The team subsequently worked to build a theory of change (Figure 3). Other components of the anti‐racism work included creating a stakeholder diagram based on two categories: (1) level of support for anti‐racism work and (2) importance of buy‐in for the success of this work. The team also conducted informal interviews with a variety of internal ACT network members (eg, those members who also work at CCHMC) to inform where to start the antiracism work, learn about the historical context of antiracism work in the network, and build will for the effort. Collectively, these efforts led the team to testable interventions. Based on this process of developing our theory of change, conducting a stakeholder analysis, and conducting informal interviews, the antiracism team learned that internal members of the ACT network did not know how to talk about racism nor where to start to address racism. The antiracism team therefore developed a meeting series focused on antiracism‐related education and capacity building. In this series, the team created brave spaces 50 of learning in which a volunteer group of ACT network members were able to have open and honest dialog regarding racism and its impact on both their personal and professional lives. The team chose the term “brave spaces” intentionally to set the expectation that the team could not promise the comfort many associate with “safety” (eg, safe spaces). Instead the group (eg, the volunteer group and the antiracism Team) would have to lean in to the challenging nature of these conversations. 50 Additionally, we emphasized the importance of embracing failure. The group was there to provide critical feedback with the understanding that critical feedback is an investment in another's continued improvement. The group then worked together to develop a common language by defining terms including race, racism, white privilege, and white supremacy. The antiracism team, led by the needs of the group, also provided education about the historical impact of racism, and the group worked together to identify and name the influence of racism on the work of ACT. Building on this foundation, the group used case studies to identify and then practice addressing racism in the work and the work environment. Our early experience in the antiracism work has affirmed that this work is hard, and resistance to this work shows up both at the individual and institutional levels. The following are learnings based on our experience about how to do this equity work within our network—generalizable principles that could be applied to equity within Learning Health Systems. First, our experience affirmed that time, space, and access to resources, including subject matter experts and measurement tools, are critical. Dismantling structural racism and other forms of systemic oppression that thrive on mutually reinforcing inequitable systems requires time. 51 While quick wins are important for building early will, long‐term support is necessary to achieve sustained change. Second, the experience affirmed that it is essential to include diversity in race, ethnicity, age, gender identity, role within CCHMC, and perspective. Working in an echo chamber decreases a team's ability to identify blind spots. This is particularly important when working to identify and dismantle white supremacy within a system built upon white supremacy. Third, our early experience affirmed the need to create an environment in which team members can call out hesitations and motivations, examine and discuss root causes, and openly contemplate whether or not their efforts are producing the desired outcome. We are now working to scale this intervention to other groups across CCHMC. |

FIGURE 3.

Example key driver diagram for antiracism work

3.7. PRACTICE 7: Engage beyond the healthcare system

Health is largely produced outside of healthcare. 52 As such, most inequities in health are tied to systems and factors external to healthcare. 10 Therefore, to achieve and sustain health equity, learning health systems must not only act within its own system but also partner across systems that influence health and health equity. In this, learning health systems can catalyze and collaborate in change across systems that together produce health. In doing so, a learning health system moves from being driven by actors who work within the healthcare system, and thereby centered largely in healthcare, to being driven by the broader set of actors including those who partner with and receive care from the healthcare system, therefore shifting the center of the learning health system.

To illustrate the practice of engaging beyond the healthcare system, we describe one pilot project that we completed as we furthered this practice.

| Use Case 3. Testing a cross‐sector process to inform housing policy in one US city |

|

Children living in unstable, unaffordable, unsafe, and low‐quality housing are at significant disadvantage. Such housing insecurity creates a hostile environment. The complexity of challenges range from substandard conditions to impending housing loss to eviction to homelessness plague families in cities across the US. These problems arise in part from dysfunctional housing systems in which those working within these systems are often siloed from one another, rules are disconnected from lived experience, power gradients are reinforced, and response times are considered nonurgent to nonexistent by those poised to intervene. In Cincinnati, OH, the Housing Action Team (HAT), including the Wellbeing with Community Improvement team of ACT and housing stakeholders, sought to identify solutions to persistent housing challenges by implementing strategies that disrupt these system factors while maintaining a focus on child health and wellbeing. To form HAT, the Wellbeing with Community team convened a cross‐sector team, placing child experience at the center of our process. HAT included individuals actively engaged in solving housing insecurity with families, including healthcare, social service agencies, and nonprofit organizations. In weekly huddles with structured sharing of active housing insecurity cases, HAT members collaborated to identify root causes, real‐time solutions, gaps, and immediate action steps. We generated cross‐sector, child‐centered, evidence‐based policy recommendations and created a process that may be applied to other content and settings. The HAT conducted a case‐based, action‐oriented learning process using quality improvement and qualitative methods. Prompted by discussions with stakeholders, our team generated learnings about how the housing system functions for children. We huddled weekly, with one member presenting one to two active cases of families experiencing housing insecurity, using a standard situation‐background‐assessment‐recommendation format adapted from healthcare communication. We analyzed discussion content to identify themes from which we developed housing problem categories. For each category, we completed a failure‐mode‐and‐effects analysis to outline existing processes, ways in which processes fail, and opportunities for improvement. Our team assessed each case for whether existing policy and/or policy under consideration could contribute to preventing or solving identified problems. We determined the number of families that would have been helped by each policy under consideration and the number that would still be affected by policy gaps. Over 13 weeks, HAT discussed 17 cases, averaging nine participants per huddle. We identified common housing problems for children, provided a forum for rapid cross‐sector action and learning, and developed a process by which child experience could inform policy. We identified four categories (housing displacement, legal eviction, substandard housing conditions, and lack of affordable housing) and documented real‐time solutions for seven cases (41%). We identified a policy under consideration that would have helped three to four times more families than any other candidate policy. We identified 14 gaps for future policy to address to improve housing security for children. The top three gaps were unequal accountability between landlord and tenant, lack of funding for civil cases concerning housing, and lack of robust tenant education. We presented findings to stakeholders and policymakers to inform decisions on housing policy. We are now adapting this approach to address multiple unmet social needs for children and families in Cincinnati. |

4. CONCLUSION

This work is deeply complex and challenging at individual, institutional, and structural levels and requires sustained and persistent effort. Essentially all learning health systems, including our own, have a long way to go to fully manifest what is needed to pursue, achieve, and then sustain health equity. The achievement and sustainment of equity in and through learning health systems will require real transformation, both within and by those systems. We offer seven practices that can support the necessary transformation: establish principle, measure for equity, lead from lived experience, co‐produce, redistribute power, practice growth mindset, and act within and beyond. With such transformation comes the promise of equitable systems and places co‐producing better outcomes and narrowed gaps.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Riley has received funding from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Heluna Health to support her effort in developing and implementing the measurement framework for the 100 Million Healthier Lives initiative and Wellbeing in the Nation. None of the other authors have a conflict of interest.

Parsons A, Unaka NI, Stewart C, et al. Seven practices for pursuing equity through learning health systems: Notes from the field. Learn Health Sys. 2021;5(3):e10279. 10.1002/lrh2.10279

REFERENCES

- 1. Wolfe A. Institute of Medicine report: crossing the quality chasm: a new health care system for the 21st century. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2001;2(3):233‐235. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford University; 1994. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2003;57(4):254‐258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Health Promot Int. 1991;6(3):217‐228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Appel I, Nickerson J. Pockets of poverty: The long‐term effects of redlining; 2016. Available at SSRN 2852856.

- 6. Adeola FO, Picou JS. Hurricane Katrina‐linked environmental injustice: Race, class, and place differentials in attitudes. Disasters. 2017;41(2):228‐257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hanna‐Attisha M, LaChance J, Sadler RC, Schnepp C, Allison . Elevated blood lead levels in children associated with the Flint drinking water crisis: a spatial analysis of risk and public health response. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):283‐290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Friedman C, Rubin J, Brown J, et al. Toward a science of learning systems: a research agenda for the high‐functioning Learning Health System. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(1):43‐50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boothroyd RI, Flint AY, Lapiz AM, Lyons S, Jarboe KL, Aldridge WA. Active involved community partnerships: co‐creating implementation infrastructure for getting to and sustaining social impact. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(3):467‐477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brooks D, Douglas M, Aggarwal N, Prabhakaran S, Holden K, Mack D. Developing a framework for integrating health equity into the learning health system. Learn Health Syst. 2017;1(3):e10029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Forrest CB, Margolis P, Seid M, Colletti RB. PEDSnet: how a prototype pediatric learning health system is being expanded into a national network. Health Aff. 2014;33(7):1171‐1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donabedian A. Models for organizing the delivery of personal health services and criteria for evaluating them. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1972;50(4):103‐154. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Donabedian A, Wheeler JRC, Wyszewianski L. Quality, cost, and health: an integrative model. Med Care. 1982;XX(10):975‐992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chin MH. Advancing Health Equity in Patient Safety: A Reckoning, Challenge and Opportunity. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lion KC, Raphael JL. Partnering health disparities research with quality improvement science in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):354‐361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Woodward EN, Matthieu MM, Uchendu US, Rogal S, Kirchner JAE. The health equity implementation framework: proposal and preliminary study of hepatitis C virus treatment. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):1‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wyatt R, Laderman M, Botwinick L, Mate K, Whittington J. Achieving Health Equity: A Guide for Health Care Organizations. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Israel B, Eng E, Schulz A, Parker E. Methods in Community‐Based Participatory Research for Health. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19. All Children Thrive . All Children Thrive Principles; 2019. https://www.actnowcincy.org/principles.

- 20. 100 Million Healthier Lives . 100 Million Healthier Lives Advancing Equity Tools; 2020a.

- 21. Crenshaw K, Gotanda N, Peller G, Thomas K. Critical race theory. The Key Writings that Formed the Movement. New York; The New Press; 1995:276‐291. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Andrist E, Riley CL, Brokamp C, Taylor S, Beck AF. Neighborhood poverty and pediatric intensive care use. Pediatrics. 2019;144(6):1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beck AF, Florin TA, Campanella S, Shah SS. Geographic variation in hospitalization for lower respiratory tract infections across one county. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(9):846‐854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Beck AF, Huang B, Wheeler K, Lawson Nikki R, Kahn Robert S, Riley Carley L. The child opportunity index and disparities in pediatric asthma hospitalizations across one Ohio Metropolitan Area, 2011–2013. J Pediatr. 2017;190:200‐206. e201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Beck AF, Riley CL, Taylor SC, Brokamp C, Kahn RS. Pervasive income‐based disparities in inpatient bed‐day rates across conditions and subspecialties. Health Aff. 2018;37(4):551‐559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Riney LC, Brokamp C, Beck AF, Pomerantz WJ, Schwartz HP, Florin TA. Emergency medical services utilization is associated with community deprivation in children. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23(2):225‐232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Langley Gerald J, Moen Ronald D, Nolan Kevin M, Nolan Thomas W, Norman Clifford L, Provost Lloyd P. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. San Francisco, CA: Josey‐Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shmitz P. Community engagement toolkit; 2014. https://www.collectiveimpactforum.org/resources/community-engagement-toolkit.

- 29. 100 Million Healthier Lives . Well‐being in the Nation (WIN) Measurement Framework; 2019. https://insight.livestories.com/s/v2/win-measures/2fda874f-6683-49bd-adb2-22f6f3c5a718/.

- 30. Milstein B, Roulier M, Hartig E, Kellerher C, Wegley S. Thriving Together: A Springboard for Equitable Recovery and Resilience in Communities Across America. CDC Foundation and Well Being Trust. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stiefel M, Riley C, Roy B, McPherson M, Nagy J. Health and Well‐being Measurement Approach and Assessment Guide; 2020. www.ihi.org/100MLives.

- 32. Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR. On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog. 2020;10. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Divers J, Mayer‐Davis EJ, Lawrence JM, et al. Trends in incidence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among youths—selected counties and Indian reservations, United States, 2002–2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(6):161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berry Jay G, Bloom S, Foley S, Palfrey Judith S. Health inequity in children and youth with chronic health conditions. Pediatrics. 2010;126(suppl. 3):S111‐S119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marrero DG. Diabetes care and research: what should be the next frontier? Diabetes Spectrum. 2016;29(1):54‐57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stiles S, Thomas R, Beck AF, et al. Deploying community health workers to support medically and socially at‐risk patients in a pediatric primary care population. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(8):1213‐1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Batalden P. Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets; 1984.

- 38. 100 Million Healthier Lives . Engaging People with Lived Experience Toolkit ; n.d.. https://www.communitycommons.org/collections/Engaging‐Lived‐Experience‐Toolkit.

- 39. Costanza‐Chock S. Design justice: Towards an intersectional feminist framework for design theory and practice. Proc Design Res Soc. 2018.

- 40. Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics [1989]. New York: Routledge; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 41. McNulty M, Smith JD, Villamar J, et al. Implementation research methodologies for achieving scientific equity and health equity. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(suppl 1):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Goodman MS, Thompson S, Vetta L. The science of stakeholder engagement in research: classification, implementation, and evaluation. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(3):486‐491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wallerstein N, Oetzel JG, Sanchez‐Youngman S, et al. Engage for equity: A long‐term study of community‐based participatory research and community‐engaged research practices and outcomes. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47(3):380‐390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wilkins CH, Alberti PM. Shifting academic health centers from a culture of community service to community engagement and integration. Acad Med. 2019;94(6):763‐767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. 100 Million Healthier Lives . Co‐Design/Distributed Leadership Debrief Discussion Tool; 2020b. https://www.communitycommons.org/entities/1f6e894a‐c413‐493b‐a92d‐eabb78259606.

- 46. Racial Equity Learning and Action Community . Racial Equity Map; 2020.

- 47. Lasker RD, Weiss ES, Miller R. Partnership synergy: a practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Milbank Q. 2001;79(2):179‐205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lucero JE, Boursaw B, Eder MM, Greene‐Moton E, Wallerstein N, Oetzel JG. Engage for equity: The role of trust and synergy in community‐based participatory research. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47(3):372‐379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Racial Equity Map ; 2020. https://www.communitycommons.org/entities/e9c36078-d467-4b97-bad0-47e426c421a3.

- 50. Arao B, Clemens K. From safe spaces to brave spaces. The Art of Effective Facilitation: Reflections From Social Justice Educators; Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing; 2013:135‐150. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. The Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453‐1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Givens M, Gennuso K, Jovaag A, Van Dijk J. County Health Rankings Key Findings Report. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute; 2019. [Google Scholar]