Abstract

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander holistic health represents the interconnection of social, emotional, spiritual and cultural factors on health and well-being. Social factors (education, employment, housing, transport, food and financial security) are internationally described and recognised as the social determinants of health. The social determinants of health are estimated to contribute to 34% of the overall burden of disease experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Primary health care services currently ‘do what it takes’ to address social and emotional well-being needs, including the social determinants of health, and require culturally relevant tools and processes for implementing coordinated and holistic responses. Drawing upon a research-setting pilot program, this manuscript outlines key elements encapsulating a strengths-based approach aimed at addressing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander holistic social and emotional well-being.

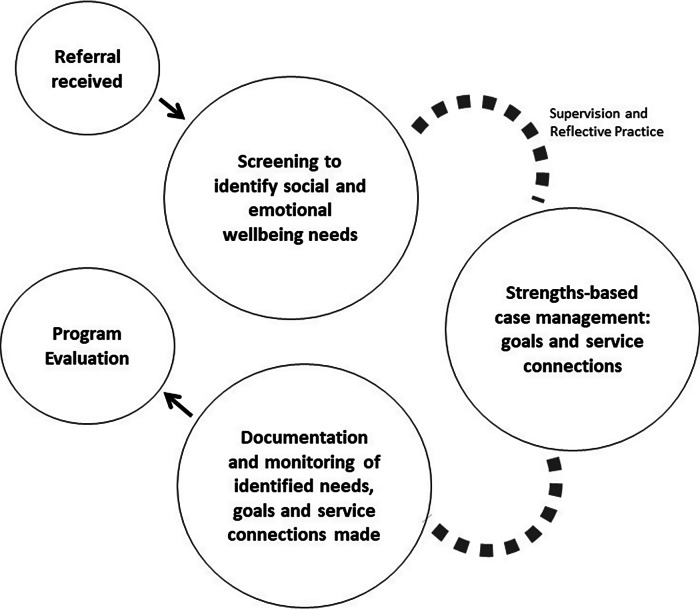

The Cultural Pathways Program is a response to community identified needs, designed and led by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and informed by holistic views of health. The program aims to identify holistic needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the starting point to act on the social determinants of health. Facilitators implement strengths-based practice to identify social and cultural needs (e.g. cultural and community connection, food and financial security, housing, mental health, transport), engage in a goal setting process and broker connections with social and health services. An integrated culturally appropriate clinical supervision model enhances delivery of the program through reflective practice and shared decision making. These embedded approaches enable continuous review and improvement from a program and participant perspective. A developmental evaluation underpins program implementation and the proposed culturally relevant elements could be further tailored for delivery within primary health care services as part of routine care to strengthen systematic identification and response to social and emotional well-being needs.

Key words: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, case management, evidence-based practice, primary health care, social and emotional well-being, social determinants of health

Introduction

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge and wisdom has long recognised the role of social and cultural factors on health and well-being (Bartlett & Boffa, 2001). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander holistic health philosophy describes social and emotional well-being as the interconnection of social emotional, spiritual, cultural factors on health and wellness of not just individuals but communities (NAHSWP, 1989). Social and emotional well-being as conceptualised by Gee et al. (Dudgeon et al., 2014) recognises the ongoing influence of historical, political and social factors on health and social outcomes (Swan & Raphael, 1995; Raphael & Swan, 1997; Dudgeon et al., 2014; Paradies et al., 2015). These social factors (employment, education, housing, income and transport) are internationally described and recognised as the social determinants of health and are estimated to contribute to 34% of the overall burden of disease experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (ABS, 2013). Both internationally and cross-culturally peer-reviewed literature has established associations, explored pathways and biological mechanisms providing a critical knowledge base on the role of social factors on health (Braveman et al., 2011). Despite these understandings, there is limited evidence on effective intervention strategies that address how these social factors influence health outcomes within the population (Bambra et al., 2010; Thornton et al., 2016; Alegría et al., 2018; Luchenski et al., 2018).

Recent government consultations highlight the importance of self-determined and timely action on the social determinants of health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities incorporating system responses that are coordinated, culturally relevant and strengths-based (Andermann, 2016; Commonwealth of Australia, 2017; Frier et al., 2020; Osborne et al., 2013). Health systems face challenges in responding to the complex nature of the social determinants of health with collaborations required across health and social services; nonetheless, the clinical frontline workforce have been recognised as a potential catalyst for change in any systems response (Andermann, 2016). Clinical workforce approaches that include screening clients for social and emotional well-being (which include the social determinants of health) facilitate the early identification and management of needs, planned and coordinated responses and the monitoring of progress and outcomes (Langham et al., 2017).

In a current context, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHOs) and primary health care services are ‘doing whatever it takes’ to meet the social and emotional well-being needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people which includes addressing the social determinants of health in service delivery (CREATE, 2020). Consultations with ACCHOs have highlighted key principles which inform holistic approaches to the social determinants of health including self-determination, accessible and culturally safe care and strong partnerships that support clients to navigate social services (CREATE, 2020). A recent document analysis of 67 ACCHO annual reports found that all services were working to improve clients’ intermediary social determinants of health, specifically material circumstances, biological, behavioural and psychosocial factors (Pearson et al., 2020). Whilst structured and funded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health assessments for preventative care are widely implemented, these assessments are limited by a biomedical focus that inadequately addresses social and cultural factors (Bailie et al., 2019). Across organisations there are varied responses depending on the capacity (i.e. workforce, skills, training and resources) of the primary health care service (CREATE, 2020; Andermann, 2018). Furthermore, service delivery protocols for addressing the social determinants of health and more broadly data systems for monitoring their actions are not well established (Golembiewski et al., 2019; Osborne et al., 2013).

Strengths-based, person centred and empowerment approaches are often used synonymously to describe the delivery of health care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. These approaches promote individuals control over their own lives and focus on abilities and resources to enable self-determination (Bovill et al., 2019; Gibson et al., 2020; Saleebey, 1996). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who have increased control and mastery over their lived experiences are empowered in their engagement with social and health services (Tsey et al., 2010). Health care services commonly describe intentions to deliver strengths-based approaches, yet the practical and genuine implementation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is still emerging in practice (Askew et al., 2020; Gibson et al., 2020). Holistic case management models are well suited for strengths-based practice which focuses on empowering people to take charge of their own lives and to support the identification of existing strengths and resources (Saleebey, 1996). Case management approaches whilst diverse across disciplines and in different contexts usually include the following core functions; assessment, planning, linking, monitoring, advocacy and outreach services (Huber, 2002). Case management approaches in primary health care with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people report improvements in self-rated health status, reduction in depression and improved measures of diabetes control (Askew et al., 2015). These findings suggest that patient-led case management has the potential to enhance holistic approaches to social and emotional well-being (Askew et al., 2015).

The effects of colonisation and the continuing social and political oppression and dispossession of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have contributed to significant socio-economic and health inequities (Gracey & King, 2009). Persistent and disproportionate inequalities experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people highlight the need to better understand and respond to social and emotional well-being needs which includes the social determinants of health. There is a pressing need for coordinated best practice responses to social and emotional well-being screening and management, dedicated resources, training and ongoing monitoring (Langham et al., 2017). Existing evidence has not yet described approaches that collectively inform health care responses for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional well-being. To address this gap, a pilot program has been designed within a research setting and includes the following key elements: i) identifying unmet needs, ii) strengths-based case management, iii) document and monitoring, iv) culturally relevant supervision and v) evaluation. The aim of this manuscript is to describe and critically explore the program’s key elements from an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspective as part of strengthening practice-based evidence on social and emotional well-being.

Discussion

Program context

The Cultural Pathways program is implemented by Wardliparingga Aboriginal Health Equity research team in the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide, South Australia. Wardliparingga undertakes research that is of relevance to South Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities through partnerships, collaboration, respect, reciprocity and for the benefit of community (SAHMRI, 2014). The Cultural Pathways Program is designed and implemented by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as a response to community identified needs. The program is implemented within an Indigenous methodological framework and from inception to implementation the program has been underpinned by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being and doing (Rigney, 1999; Martin & Mirraboopa, 2003; Saunders et al., 2010; Wilson, 2011; Smith, 2012). Priority areas for research were established through extensive consultation and engagement with the community (King & Brown, 2015). All programs of work implemented by Wardliparingga have Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership and governance, through these structures the community consistently highlighted that more holistic responses, which included the social determinants of health, were required. The research team is predominantly Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers who bring wisdom and experience to the development of the program approach and implementation ensuring consistent alignment with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of knowing, being and doing. The program described in this manuscript was approved by the Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee of South Australia (AHREC-04-17-733).

The program approach includes comprehensive screening utilising a specifically developed holistic screening tool to identify unmet social and emotional well-being needs. Following screening, facilitators implement strengths-based case management through goal setting, prioritisation and brokering connections to services. program structures embed documentation and monitoring of the program’s social and emotional well-being responses, actions taken to address needs and outcomes for participants. These elements are underpinned by culturally relevant supervision, reflective practice and evaluation. The program approach critically explores the benefits, cultural relevance and responsiveness of common practices in case management. Through a combined understanding of these approaches, the program seeks to inform the evidence base for strengthened and coordinated responses to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional well-being.

Program delivery is undertaken by male and female facilitators with workforce roles informed by a navigator approach, to assist individuals’ engagement with the health care system and to overcome any barriers to care (Bernardes et al., 2018; Henderson & Kendall, 2011; Whop et al., 2012). Referrals are received from a large-scale population-based biomedical cohort study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander South Australians. As part of the study, all participants receive a comprehensive health assessment that includes questions regarding their social and emotional well-being. Further to this, community engagement and consultations highlighted that post-study follow-up responses for participants would require addressing social and emotional well-being needs such as psychosocial health, financial literacy, food security and material circumstances. Participants are offered a referral to the Cultural Pathways Program, if unmet social and cultural needs are identified during the assessment. The implementation setting replicates real-world service delivery models where presentation may initially be for a physical health need. Upon receipt of referrals from the study team, the Cultural Pathways Program facilitators connect with participants and implement the flexible participant led case management process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cultural Pathways Program elements for responding to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional well-being.

Program elements informing a social and emotional well-being response have been detailed within the following sections, providing the theoretical underpinnings, Cultural Pathways Program approach, embedded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of working and opportunities for strengthening practice.

Identifying unmet needs

Screening and assessment is a common first point of engagement in health settings and appropriate screening delivered as part of routine practice can enhance the timely and effective identification of needs and accordingly inform responses or prompt a more comprehensive assessment (Andermann, 2018). Indigenous specific health assessments are associated with improved preventive care for a range of health needs; however, a greater focus is needed on social and cultural factors (Bailie et al., 2019; Langham et al., 2017). Cultural Pathways Program facilitators implement a modified Social Needs Screening Tool (Health Leads 2016) to identify unmet social needs of participants. Developed through an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researcher led process, with community input to ensure cultural relevance and responsiveness, the adapted holistic tool covers well-being domains including mental health and cultural and community connection and social domains including financial and food security, transport, employment, housing and social isolation. The process of cultural development ensures the questions are relevant, asked the right way, with cultural meaning and are best able to identify the unique needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants (Brown et al., 2013; Langham et al., 2017). Screening processes for the social determinants must be accompanied by plans for action (Gottlieb et al., 2016; Davidson & McGinn, 2019), and as part of the program’s case management approach the screening process assists the Facilitator to understand participant needs and enables the identification and prioritisation of participant goals. By implementing a structured and consistent approach, identifying and documenting unmet needs enable the measurement of actions, activities and the monitoring of participant outcomes.

Strengths-Based case management

The program’s case management approach includes goal setting, prioritisation and brokering connections to services. Facilitators work in partnership with participants and tailor responses to individual circumstances and needs. A strengths-based approach to case management ensures facilitators focus on clients’ abilities, talents and resources to enable client’s self-determination skills, develop resilience and the ability to respond or navigate similar situations in the future (Saleebey, 1996). Goal setting is a common step in the case of management process (Kisthardt et al., 1992) with theoretical concepts highlighting the importance of collaboration for effective goal setting (Vanpuymbrouck, 2014). An individuals’ sense of control and autonomy influence their willingness to set goals and efforts for achieving them (Vieira & Grantham, 2011). The Australian Integrated Mental Health Initiative (AIMhi) is an existing framework that uses strengths based story telling (Nagel & Thompson, 2007). The Cultural Pathways Program implements a goal and priority setting framework utilising the AIMhi Pictorial Care Plan (Menzies School of Health Research, 2020) to explore physical, emotional, spiritual, cultural, family, social and work contexts to identify worries, strengths and resources. Consistent with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ways of working, facilitators work in partnership with participants to identify and prioritise issues of most importance that will support improved well-being. As part of the strengths-based, empowerment and person-centred approaches, participants define their own priorities contributing to enhanced autonomy, control and self-efficacy.

As part of the ‘brokering’ approach to case management, facilitators connect participants with services to meet their needs. Making a referral to other services, organisations or agencies are widely implemented in health and social services. Social and emotional well-being and social determinants of health needs span across sectors with often multiple services and agencies involved, this requires coordination to minimise the burden on service users and to enable referrals and connections (Kowanko et al., 2009). Brokering connections relies on relationships, understandings of what is available across the breadth of health and social needs and understandings of culturally relevant services (McKenna et al., 2015; Treatment Center for Substance Abuse, 2000). To support this approach, facilitators undertake service mapping exercises to identify the available services and will pro-actively seek the most appropriate service to connect a participant to and reduce barriers to access these services (Huber, 2002). Facilitators actively support participants to access services by contacting services on behalf of participants, supporting participants when they contact services themselves and follow up contact with participants to monitor progress. If necessary, facilitators address any challenges or barriers to support the best possible outcome. The active and coordinated approach to brokering connections enhances service access for participants and enables the program to also monitor brokerage outcomes.

Documentation and monitoring

Program monitoring involves measuring and reporting on progress and creates opportunities for continuous quality improvement (Hudson, 2016). Currently, health services rarely systematically collect data about or measure activity on the social determinants of health and require a mechanism to monitor and evaluate the impact of social and emotional well-being services they provide to address health outcomes (Langham et al., 2017; Reeve et al., 2015). Comprehensive understandings of the most appropriate measures for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional well-being and the social determinants of health are still emerging. Existing national measures of well-being include psychological distress, positive well-being, anger, life stressors, discrimination, cultural identification and removal from natural family (AIHW, 2009). Measures for the social determinants of health as described by the World Health Organization (WHO) Conceptual Framework (Solar & Irwin, 2010) and outlined in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework (AHMAC, 2017) include domains such as connection to country, education, employment, health system, housing, income and transport.

The Cultural Pathways Program combines social and emotional well-being and social determinants of health measures as part of the programs’ monitoring framework. The program utilises REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure web platform for managing online databases (Harris et al., 2009). The platform collects participant information, demographics and activity data which include when and how people are contacted and the services provided by social/health domain. The program measures factors such as unmet needs, identified goals, whether they have been achieved and the service connections made. The program utilises routine data for ongoing monitoring, quality improvement and as part of funding requirements and obligations. The data collected by the program was informed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander understandings of health and well-being and the wisdom and expertise of the research team and community. The process included the collective development of culturally relevant measures in relation to social and emotional well-being, specifically practical ways to measure progress towards addressing complex social and cultural factors. This process enabled the program to capture information that is useful and relevant for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. A structured and consistent approach to identifying needs and a specifically designed monitoring framework enables the program to measure progress or outcomes which can be used to understand the needs of service users, to plan responses and to advocate for resources (Harfield et al., 2018).

Culturally relevant supervision

Reflective practice and clinical supervision are recognised by many professions for their role in supporting enhanced clinical practice as well as the health and well-being of the workforce (Koivu et al., 2012; Scerra, 2012; Thompson & Pascal, 2012). This is particularly important for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers and practitioners who have complex experiences including burnout and vicarious trauma (Nelson et al., 2015). The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce and non-Indigenous workers in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health contexts require access to high-quality cultural and clinical supervision which supports cultural safety, improved practice and well-being (Bainbridge et al., 2015; Truong et al., 2014). Available frameworks for culturally appropriate supervision with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people include considerations for working with community, looking after self, understanding of roles and professional practice (Koivu et al., 2012; Nelson et al., 2015; Scerra, 2012; Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA), 2013; Victorian Dual Diagnosis Education and Training Unit (VDDI), 2012). Despite the important role of culturally relevant clinical supervision in enhanced service delivery and the support and retention of the workforce in health care settings (AHCSA, 2020), evidence-based understanding of applied practice models are still emerging in peer reviewed evidence.

The Cultural Pathways Program utilises these existing frameworks as well as the knowledge and experience of program staff to implement a culturally relevant reflective practice and supervision model. An experienced Aboriginal clinician supports facilitators through a range of structures including weekly clinical yarning, one to one yarning and debriefing opportunities as required. Facilitators share perspectives, feelings, challenges, barriers and enablers in relation to both clinical practice as well as system, policy and organisational factors which impact the participant, Facilitator, or the program. Fundamentally, the supervision and reflective practice model are culturally grounded in relationships and yarning to support the cultural safety for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants whilst also enabling the retention and well-being of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforce.

Developmental evaluation

Evaluating health programs and initiatives supports implementation across different contexts utilising insights into how and why they work and whether they have been effective (Lokuge et al., 2017). There is an increasing recognition of the important role of evidence-based programs featuring high quality and culturally relevant evaluation (Productivity Commission, 2019). The Cultural Pathways Program is underpinned by an Indigenous methodological evaluation framework which utilises Developmental Evaluation, an approach to evaluation that supports innovation and adaptation in complex environments (Fagen et al., 2011; Patton, 2010), and is consistent with Indigenous methodology and participatory approaches requiring partnerships, trust and shared decision making (Gamble, 2008). The key to developmental evaluation is that the evaluator works with the team in real-time, asking evaluation questions, examining and tracking implications of adaptations and providing timely feedback as the program is implemented and modified or adapted as needed. The evaluator as an Aboriginal woman is immersed in as an insider drawing heavily on reflective practice and utilising the cultural knowledge and expertise of the evaluator as part of the evaluation method. The aim of the evaluation is to understand the process including what was delivered, how it was implemented and the experiences of program participants. The evaluation through reflective and formative methods supports further understanding on the interactions between facilitators, program participants and the broader health and social service contexts. The evaluation framework includes community engagement, governance and approaches which have been purposely selected for their consistency with Indigenous methodologies. This framework ensures that the participation and voice of the community are therefore embedded throughout implementation to support tangible benefits to the community (SAHMRI, 2014).

Conclusions

There is a knowledge to action gap on how to assess and address the social determinants of health within clinical practice to inform the development of coordinated, culturally relevant and strength-based responses to meet the holistic social and emotional well-being needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities.

Primary health care services, often as the entry point for accessing health services, are well positioned to implement coordinated health equity responses which include addressing the social determinants of health (Pereira et al., 2017; Rasanathan et al., 2011). The absence of a readily applied model creates challenges for the provision of coordinated, resourced and systemic responses to the social determinants of health (CREATE, 2020). Routine screening for unmet needs, implementing strengths-based practice, connecting people to what they need, monitoring service provision and providing clinical and cultural support for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforce align to existing practice and are transferable across contexts. Continuous quality improvement and monitoring enables primary health care services to embed new practices into services, systems and routines (Gardner et al., 2010).

The ability to implement holistic approaches to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health through the intersection of health and social services requires adequate resources, training and support to clinical workforce (Andermann, 2016), including consideration of roles, responsibilities, scope of practice and readiness to implement strengths-based approaches. These changes cannot be implemented without addressing the ongoing impacts of racism and oppression of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, allowing for culturally safe systems which are able to meet holistic social and emotional well-being needs (Curtis et al., 2019; Durey, 2010; Laverty et al., 2017; Muise, 2019; Secombe et al., 2019).

The Cultural Pathways Program builds on existing approaches to contribute to practice-based evidence of culturally relevant case management approaches which can be utilised as part of routine care to strengthen the systematic identification and response in primary health care delivery. The combined understandings of the elements outlined in this manuscript provide a framework to inform service planning and tailored implementation which can strengthen social and emotional well-being responses for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Wyatt Benevolent Institution Inc.

Funding

The program is philanthropically funded by the Wyatt Benevolent Institution Inc. TB is funded by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. AB is funded by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (1137563).

About the contributors

Consistent with cultural protocol we position the contributors to this manuscript:

Tina Brodie is an Aboriginal woman with connections to Yawarrawarrka and Yandruwandha. She is a third year PhD Candidate at The University of Adelaide in the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences and a Clinical Research Associate in Wardliparingga Aboriginal Health Equity, South Australian Health and Medical Institute. Her Research is exploring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Emotional Well-being, specifically the social determinants of health. Tina has over ten years of experience in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health in multiple clinical, project and leadership roles working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and families. Tina has expertise in Indigenous methodologies and culturally responsive and ethical ways of working and engaging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities in research.

Odette Pearson is a Kuku Yalanji/Torres Strait Islander Population Health Platform Lead in Wardliparingga Aboriginal Research Unit at South Australian Health & Medical Research Institute. Her experience and post-doctoral training in Aboriginal health policy, health systems and inequity comprises a unique comprehensive skillset relevant to existing and emerging complexities of Aboriginal health and well-being. Specifically, Odette seeks to understand how institutional policies and practices drive health and social inequities experienced by Indigenous populations. Her novel approach is the use of community-level information to show and explore the reasons for variations in disadvantage both within the Aboriginal community and between the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal community. Integral to her research is the inclusion of Aboriginal communities in defining their health and well-being and how Indigenous data can be governed in the future to derive greater benefit for the population.

Luke Cantley has family connections to the Gunditjmara nation of Victoria and is a Research Associate located within Flinders University. Through his research, Luke is determined to solidify Aboriginal culture as a protective factor within the child protection system, whilst exploring the nuances between child safety and cultural safety. Luke holds extensive knowledge on the role unmet social and cultural needs have on positive health outcomes within the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community and holds a strong passion for advocating for increased health care utilisation for health care consumers. Luke has gained extensive experience working as an Aboriginal Health Worker within a strengths-based approach across diverse sectors including Prison health, Primary Health Care, Public Housing and Mental Health Services. Developing expertise in 1) Culturally appropriate and ethical ways of engaging within the community, 2) Health and Well-being assessment methods fostering participatory action research, and 3) Social inequities generated by reduced access to services or resources.

Peita Cooper has a Bachelor of Social Work and currently works within the justice sector. Peita commenced as a Graduate in Wardliparingga Aboriginal Health Equity Theme, at the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI). As a Program Facilitator, Peita contributed to the delivery of strengths-based case management and developing culturally responsive practice with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ and communities. Her previous experience includes working in the disability sector.

Seth Westhead has family connections to the Awabakal and Wiradjuri nations of NSW and is a Research Associate with Wardliparingga Aboriginal Health Equity Theme, South Australian Health & Medical Research Institute. Through his research work, Seth strives to better understand how social and cultural determinants drive health and social inequities within society, particularly as it relates to the Indigenous population. He seeks to better equip communities and young people with tools and evidence for public health advocacy and enable communities to translate health research into meaningful action. Specifically, Seth has expertise in the: 1) conceptual development of Aboriginal specific social determinants and well-being frameworks and tools, 2) implementation of projects involving community engagement and community-led governance structures 2), and 3) undertaking of qualitative research methodologies and community and stakeholder participation interpretation of findings.

Alex Brown is an Aboriginal medical doctor and researcher, he is the Theme Leader of Wardliparingga Aboriginal Health Equity and Professor of Medicine at the University of Adelaide. He grew up on the south coast of New South Wales (NSW) with family connections to Nowra, Wreck Bay and Wallaga Lake on the far south coast of NSW. Over the last 20 years, Alex has established an extensive and unique research program focused on chronic disease in vulnerable communities, with a particular focus on outlining and overcoming health disparities. He leads projects encompassing epidemiology, psychosocial determinants of chronic disease, mixed methods health services research in Aboriginal primary care and hospital settings, and randomised controlled trials of pharmacological and non-pharmacological chronic disease interventions. Alex has been heavily involved in engaging government and lead agencies in setting the agenda in Aboriginal cardiovascular disease management and control and chronic disease policy more broadly. He sits on a range of national committees, and co-chairs the Indigenous Research Health Fund through the MRFF.

Natasha Howard is the Wardliparingga Platform Lead: Implementation Science. The platform incorporates a systems view and privileges Indigenous knowledge to deliver mixed-method inter-disciplinary perspectives which aim to generate policy and practice-based evidence on the social determinants of health. Her experience spans both the health and social sciences, applying population approaches to investigate how the social and built environment enables and promotes cardiometabolic health and well-being, notably for priority populations. She has been active in advocacy and mentoring of the local population health community in both research and practice.

Conflict(s) of interest

None.

Ethical approval

This program was approved by the Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee of South Australia (AHREC 04-17-733).

References

- Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia (AHCSA) (2020) Valuing and strengthening Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Workforce: A guide to promote supportive working environments in health and human services for organisations and managers viewed 10 September 2020, https://ahcsa.org.au/app/uploads/2014/11/AHC5321_Managers_Booklet_final.pdf.

- Alegría M, NeMoyer A, Falgàs Bagué I, Wang Y and Alvarez K (2018) Social determinants of mental health: where we are and where we need to go. Current Psychiatry Reports 20, 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andermann A (2016) Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. Canadian Medical Association Journal 188, E474–E483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andermann A (2018) Screening for social determinants of health in clinical care: moving from the margins to the mainstream. Public Health Reviews 39, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askew DA, Brady K, Mukandi B, Singh D, Sinha T, Brough M and Bond CJ (2020) Closing the gap between rhetoric and practice in strengths-based approaches to Indigenous public health: a qualitative study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 44, 102–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askew D, Togni S, Schluter P, Rogers L, Egert S, Potter N, Hayman N, Cass A and Brown A (2015) Investigating the feasibility, acceptability and appropriateness of outreach case management in an urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care service: Report prepared for the Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute. Canberra: Kanyini Vascular Collaboration and Southern Queensland Centre of Excellence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2013) Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health survey: first results, Australia, 2012–13, ABS Statistics electronic collection. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC) (2017) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework 2017 report. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2009) Measuring the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Canberra: AIHW. [Google Scholar]

- Bailie J, Laycock A, Matthews V, Peiris D and Bailie R (2019) Emerging evidence of the value of health assessments for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the primary healthcare setting. Australian Journal of Primary Health 25, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge R, McCalman J, Clifford A and Tsey K (2015) Cultural competency in the delivery of health services for Indigenous people. Canberra: AIHW. [Google Scholar]

- Bambra C, Gibson M, Sowden A, Wright K, Whitehead M and Petticrew M (2010) Tackling the wider social determinants of health and health inequalities: evidence from systematic reviews. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 64, 284–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett B and Boffa J (2001) Aboriginal community controlled comprehensive primary health care: the Central Australian Aboriginal Congress. Australian Journal of Primary Health 7, 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardes CM, Martin J, Cole P, Kitchener T, Cowburn G, Garvey G, Walpole E and Valery PC (2018) Lessons learned from a pilot study of an Indigenous patient navigator intervention in Queensland, Australia. European Journal of Cancer Care. 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovill M, Chamberlain C, Bar-Zeev Y, Gruppetta M and Gould GS (2019) Ngu-ng-gi-la-nha (to exchange) knowledge. How is Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s empowerment being upheld and reported in smoking cessation interventions during pregnancy: a systematic review. Australian Journal of Primary Health 25, 395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Egerter S and Williams DR (2011) The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annual Review of Public Health 32, 381–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ADH, Mentha R, Rowley KG, Skinner T, Davy C and O’Dea K (2013) Depression in Aboriginal men in central Australia: adaptation of the Patient Health Questionnaire 9. BMC Psychiatry 13, 271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia (2017) My Life my lead – opportunities for strengthening approaches to the social determinants and cultural determinants of Indigenous health: report on the national consultations December 2017. Australian Government Department of Health, viewed 22/02/2018, http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/indigenous-ipag-consulation. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis E, Jones R, Tipene-Leach D, Walker C, Loring B, Paine S-J and Reid P (2019) Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health 18, 174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson KW and McGinn T (2019) Screening for social determinants of health: the known and unknown. JAMA 322, 1037–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudgeon P, Milroy H and Walker R (2014) Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Durey A (2010) Reducing racism in Aboriginal health care in Australia: where does cultural education fit? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 34, S87–S92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagen MC, Redman SD, Stacks J, Barrett V, Thullen B, Altenor S and Neiger BL (2011) Developmental evaluation: building innovations in complex environments. Health Promotion Practice 12, 645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frier A, Devine S, Barnett F and Dunning T (2020) Utilising clinical settings to identify and respond to the social determinants of health of individuals with type 2 diabetes—a review of the literature. Health & Social Care in the Community 28, 1119–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble JAA (2008) A developmental evaluation primer. J.W. McConnell Family Foundation, Canada.

- Gardner KL, Dowden M, Togni S and Bailie R (2010) Understanding uptake of continuous quality improvement in Indigenous primary health care: lessons from a multi-site case study of the Audit and Best Practice for Chronic Disease project. Implementation Science 5, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson C, Chatfeild K, O’Neill-Baker B, Newman T and Steele A (2020) Gulburra (to understand): Aboriginal Ability Linker’s person-centred care approach. Disability and Rehabilitation 19, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golembiewski E, Allen KS, Blackmon AM, Hinrichs RJ and Vest JR (2019) Combining nonclinical determinants of health and clinical data for research and evaluation: rapid review. JMIR Public Health Surveill 5, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb L, Fichtenberg C and Adler N (2016) Screening for social determinants of health. JAMA 316, 2552–2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracey M and King M (2009) Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. The Lancet 374, 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harfield SG, Davy C, McArthur A, Munn Z, Brown A and Brown N (2018) Characteristics of Indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systematic scoping review. Globalization and Health 14, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N and Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 42, 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Leads (2016) Health leads social needs screening tool. Health Leads, Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson S and Kendall E (2011) Community navigators: making a difference by promoting health in culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities in Logan, Queensland. Australian Journal of Primary Health 17, 347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber DL (2002) The diversity of case management models. Professional Case Management 7, 212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson S (2016) Mapping the Indigenous program and funding maze., ed. S Centre for Independent. Sydney, NSW: The Centre for Independent Studies. [Google Scholar]

- King R and Brown A (2015) Next steps for aboriginal health research: Exploring how research can improve the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal people in South Australia. Adelaide: Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Kisthardt WE, Gowdy E and Rapp, CA (1992) Factors related to successful goal attainment in case management. Journal of Case Management 1, 117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivu A, Saarinen PI and Hyrkas K (2012) Who benefits from clinical supervision and how? The association between clinical supervision and the work-related well-being of female hospital nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing 21, 2567–2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowanko I, de Crespigny C, Murray H, Kit JA, Prideaux C, Miller H, Mills D and Emden C (2009) Improving coordination of care for Aboriginal people with mental health, alcohol and drug use problems: progress report on an ongoing collaborative action research project. Australian Journal of Primary Health 15, 341–347. [Google Scholar]

- Langham E, McCalman J, Matthews V, Bainbridge RG, Nattabi B, Kinchin I and Bailie R (2017) Social and emotional wellbeing screening for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders within primary health care: a series of missed opportunities? Frontiers in Public Health 5, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laverty M, McDermott DR and Calma T (2017) Embedding cultural safety in Australia’s main health care standards. Medical Journal of Australia 207, 15–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokuge K, Thurber K, Calabria B, Davis M, McMahon K, Sartor L, Lovett R, Guthrie J and Banks E (2017) Indigenous health program evaluation design and methods in Australia: a systematic review of the evidence. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 41, 480–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchenski S, Maguire N, Aldridge RW, Hayward A, Story A, Perri P, Withers J, Clint S, Fitzpatrick S and Hewett N (2018) What works in inclusion health: overview of effective interventions for marginalised and excluded populations. The Lancet 391, 266–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin K and Mirraboopa B (2003) Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for Indigenous and Indigenist re-search. Journal of Australian Studies 27, 203–214. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna B, Fernbacher S, Furness T and Hannon M (2015) “Cultural brokerage” and beyond: piloting the role of an urban Aboriginal Mental Health Liaison Officer. BMC Public Health 15, 881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies School of Health Research (2020) AIMhi NT – Aboriginal and Islander mental health initiative, viewed 08 September 2020 2020, https://www.menzies.edu.au/page/Research/Projects/Mental_Health_and_wellbeing/AIMhi_NT_-_Australian_Integrated_Mental_Health_Initiative/

- Muise GM (2019) Enabling cultural safety in Indigenous primary healthcare. Healthcare Management Forum 32, 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel T and Thompson C (2007) AIMHI NT ‘Mental Health Story Teller Mob’: developing stories in mental health. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health 6, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- NAHSWP (1989) A national Aboriginal health strategy/prepared by the National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party. Canberra: National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JR, Bennett-Levy J, Wilson S, Ryan K, Rotumah D, Budden W, Beale D and Stirling J (2015) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health practitioners propose alternative clinical supervision models. International Journal of Mental Health: Mental Health in Australia 44, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne K, Baum F and Brown L (2013) What works? A review of actions addressing the social and economic determinants of Indigenous health. Text, Australian Institute of Family Studies 7,:53:09, https://aifs.gov.au/publications/what-works

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, Gupta A, Kelaher M and Gee G (2015) Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 10, e0138511–e0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2010) Developmental Evaluation: applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. New York: The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson O, Schwartzkopff K, Dawson A, Hagger C, Karagi A, Davy C, Brown A and Braunack-Mayer A (2020) Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations address health equity through action on the social determinants of health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. BMC Public Health, 20 (1), 1859–1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira F, Salvi M and Verloo H (2017) Beliefs, knowledge, implementation, and integration of evidence-based practice among primary health care providers: protocol for a scoping review. JMIR Research Protocols 6, 148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priest NC, Paradies YC, Gunthorpe W, Cairney SJ and Sayers SM (2011) Racism as a determinant of social and emotional wellbeing for Aboriginal Australian youth. Medical Journal of Australia 194, 546–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Productivity Commission (2019) Australian government, indigenous evaluation strategy: productivity commission issues paper.

- Raphael B and Swan P (1997) The Mental Health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. International Journal of Mental Health 26, 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rasanathan K, Montesinos EV, Matheson D, Etienne C and Evans T (2011) Primary health care and the social determinants of health: essential and complementary approaches for reducing inequities in health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 65, 656–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeve C, Humphreys J and Wakerman J (2015) A comprehensive health service evaluation and monitoring framework. Evaluation and Program Planning 53, 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigney L-I (1999) Internationalization of an Indigenous Anticolonial cultural critique of research methodologies: a guide to Indigenist research methodology and its principles. Wicazo Sa Review 14, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Saleebey D (1996) The perspective in social work practice: extensions and cautions. Social Work 41, 296–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders V, West R and Usher K (2010) Applying Indigenist research methodologies in health research: experiences in the borderlands. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 39, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Scerra N (2012) Models of supervision: providing effective support to Aboriginal staff. Australian Aboriginal Studies 2012, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Secombe PJ, Brown A, Bailey MJ and Pilcher D (2019) Equity for Indigenous Australians in intensive care. Medical Journal of Australia 211, 297–299.e291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LT (2012) Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples/Linda Tuhiwai Smith. London: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Solar O and Irwin A (2010) A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO).

- South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI) (2014) South Australian Aboriginal Health Research Accord: Companion Document, Adelaide.

- Swan P and Raphael B (1995) “Ways forward” : national consultancy report on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health. Edited by Swan P. and Raphael B. Canberra: Australian Govt. Publishing Service.

- The Centre of Research Excellence in Aboriginal Chronic Disease Knowledge Translation and Exchange (CREATE) (2020) Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations in practice: sharing ways of working from the ACCHO sector. Adelaide: Wardliparingga Aboriginal Health Equity Theme, South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute.

- Thompson N and Pascal J (2012) Developing critically reflective practice. Reflective Practice 13, 311–325. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton RLJ, Glover CM, Cené CW, Glik DC, Henderson JA and Williams DR (2016) 'Evaluating strategies for reducing health disparities by addressing the social determinants of health. Health affairs (Project Hope) 35, 1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment Center for Substance Abuse (2000) SAMHSA/CSAT treatment improvement protocols, in Integrating Substance Abuse Treatment and Vocational Services, Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong M, Paradies Y and Priest N (2014) Interventions to improve cultural competency in healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Health Services Research 14, 99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsey K, Whiteside M, Haswell-Elkins M, Bainbridge R, Cadet-James Y and Wilson A (2010) Empowerment and Indigenous Australian health: a synthesis of findings from Family Wellbeing formative research. Health & Social Care in the Community 18, 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanpuymbrouck LH (2014)'Promoting client goal ownership in a clinical setting. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy 2, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA) (2013) Our work, our ways: VACCA’s supervision program. Victoria: Northcote. [Google Scholar]

- Victorian Dual Diagnosis Education and Training Unit (VDDI) (2012) Our healing ways: supervision: a culturally appropriate model for Aboriginal workers. Fitzroy, VC: Victorian Dual Diagnosis Education and Training Unit. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira ET and Grantham S (2011) University students setting goals in the context of autonomy, self-efficacy and important goal-related task engagement. Educational Psychology 31, 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S (2011) Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Halifax and Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing, 144. The Canadian Journal for the Study of Adult Education (Online). [Google Scholar]

- Whop LJ, Valery PC, Beesley VL, Moore SP, Lokuge K, Jacka C and Garvey G (2012) Navigating the cancer journey: a review of patient navigator programs for Indigenous cancer patients. (Report). Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology, 8(4), e89–e96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]