Abstract

Background and aims

Having anecdotally noted a high frequency of lobar-restricted cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) mimicking cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) in patients with previous cardiac surgery (especially valve replacement) presenting to our transient ischaemic attack (TIA) clinic, we set out to objectively determine the frequency and distribution of microbleeds in this population.

Methods

We performed a retrospective comparative cohort study in consecutive patients presenting to two TIA clinics with either: (1) previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) (n=41); (2) previous valve replacement (n=41) or (3) probable CAA (n=41), as per the Modified Boston Criteria, without prior cardiac surgery. Microbleed number and distribution was determined and compared.

Results

At least one lobar-restricted microbleed was found in the majority of cardiac surgery patients (65%) and 32/82 (39%) met diagnostic criteria for CAA. Valve replacement patients had a higher microbleed prevalence (90 vs 51%, p<0.01) and lobar-restricted microbleed count (2.6±2.7 vs 1.0±1.4, p<0.01) than post-CABG patients; lobar-restricted microbleed count in both groups was substantially less than in CAA patients (15.5±20.4, p<0.01). In postcardiac surgery patients, subcortical white matter (SWM) microbleeds were proportionally more frequent compared with CAA patients. Receiver operator curve analysis of a ‘location-based’ ratio (calculated as SWM/SWM+strictly-cortical CMBs), revealed an optimal ratio of 0.45 in distinguishing cardiac surgery-associated microbleeds from CAA (sensitivity 0.56, specificity 0.93, area under the curve 0.71).

Conclusion

Lobar-restricted microbleeds are common in patients with past cardiac surgery, however a higher proportion of these CMBs involve the SWM than in patients with CAA.

Keywords: stroke, amyloid, cardiology

Introduction

Cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) are small perivascular haemosiderin deposits detectable on blood sensitive MRI sequences. They commonly represent a radiologic marker of cerebral small vessel disease. Among the most common causes of CMBs is cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA).1 2 The pattern of CMB distribution is important for determining underlying vascular pathology and in turn risk of intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH), since CAA is associated with the highest bleeding risk.3 This is especially relevant for decided antithrombotics treatments and determining thrombolysis risk should ischaemic stroke occur.1 4 5

It has been suggested that cortical/subcortical predominant CMBs can develop acutely postcardiac surgery, such as in the setting of valve replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).6–8 These findings, if persisting chronically, provide a diagnostic challenge as a ‘lobar’ pattern of microbleed distribution mimics that seen in CAA and may fulfil the Modified Boston Criteria for ‘probable CAA’. This could lead to inappropriate cessation of antithrombotic therapy or avoidance of reperfusion treatments in patients whose microbleeds are secondary to cardiac surgery, rather than underlying CAA.

We have observed through our neurovascular services several patients with ‘lobar-restricted’ microbleeds and a history of cardiac surgery. Longitudinal imaging did not show increasing microbleed burden, suggesting a chronic pattern.

Aims

We, therefore, set out to systematically investigate the incidence and distribution of CMBs in patients presenting to our transient ischaemic attack (TIA) clinics with a history of cardiac surgery (with and without valve surgery) and those without cardiac surgery but meeting ‘probable’ CAA diagnostic criteria, in order to determine whether anatomical differences in distribution exist.

Method

Patient cohort

We performed a retrospective two-centre cohort study of 2022 consecutive patients presenting to the TIA clinic at the Royal Adelaide Hospital and Lyell McEwin Hospital spanning 2012–2019. Patients were referred to our clinic from general practitioners or emergency physicians across multiple hospitals in South Australia, having presented with ‘possible’ or ‘probable’ TIA symptoms. TIA clinic protocol included neuroimaging (diffusion weighted imaging (DWI), fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI)) prior to appointment, followed by review of clinical and radiological information by a neurovascular consultant neurologist.

All patients with either a history of cardiac surgery, (CABG and/or cardiac valve replacement) or MRI changes consistent with ‘probable CAA’ (as per the Modified Boston criteria) were identified. From this cohort, we reviewed patients in a consecutive fashion starting from 2012. Patients with a history of valve replacement were less numerous, totalling 41 during this time period. We then compared these patients with 41 consecutively-identified patients with CAA and 41 with previous CABG. Several patients were excluded in this process in the setting of: (1) probable CAA diagnosed prior to cardiac surgery (n=3); (2) other potential causes for lobar-restricted CMBs (n=1); (3) non-compatible pacemaker device that precluded MRI (n=15); (4) refusal to have MRI (n=2) and (5) patients without cardiac surgery in whom MRI changes were reported by a radiologists as demonstrating ‘probable CAA’, however, in whom on review had deep microbleeds precluding a diagnosis of CAA in accordance with the Modified Boston criteria (n=7).

Demographics, cardiovascular risk factors and cardiac procedure details were extracted from medical records. Follow-up was extracted from SA public hospital databases.

Data availability statement

Anonymised data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.

Neuroimaging

MRI was performed across four Adelaide sites (three major hospitals and one private imaging centre). The majority of scans were performed using a 3 Tesla machine (otherwise 1.5 Tesla) with equal representation of the three patient cohorts imaged in each machine. Scans were performed in the following order: 3-plane localiser; DWI; SWI; and FLAIR. GRE was not used. Either CT angiography arch to vertex or MR angiography of intracranial and extracranial vessel was performed in all patients. Images were independently reviewed (MDS and WV). Differences in final microbleed count and location were resolved by consensus.

CMBs were characterised as small, rounded, or circular, well-defined hypointense lesions within brain parenchyma with clear margins and a size of ≤10 mm on the SWI image.5 Microbleed mimics such as vessels, calcification, partial volumes and haemorrhages within or adjacent to an infarct were carefully excluded. Furthermore, microbleeds seen in close proximity of infarcted tissue (acute or chronic) were excluded. We used a modified version of the Brain Observer Micro Bleed Scale to measure the presence, amount, and topographical distributions of CMBs in each subject.9 Only ‘certain’ CMBs were counted in this study. Microbleeds were categorised as cortical or juxta-cortical (includes subcortical microbleeds that touch the grey-white matter junction), subcortical white matter (SWM) (includes periventricular white matter and deep portions of the centrum semiovale), deep (includes any CMBs within the basal ganglia, thalamus, brainstem and internal or external capsules) and the cerebellum, see figure 1. Brain images were also examined for evidence of: (1) acute ischaemia or haemorrhage; (2) old areas of ischaemia or haemorrhage; (3) leukoaraiosis with severity rated using the modified Fazekas scale10 and (4) superficial siderosis.

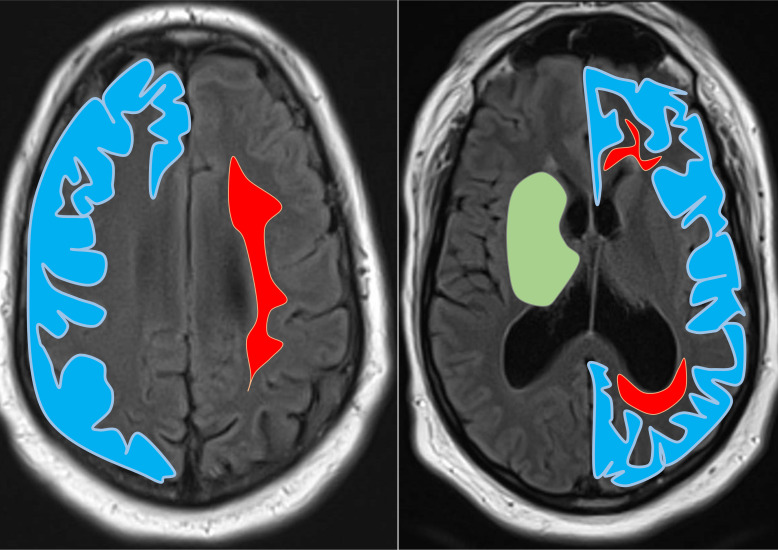

Figure 1.

Diagrams illustrating lobar and deep regions superimposed on MRI. Blue=cortex; red=subcortical white matter; green=deep matter (includes caudate head, lentiform nucleus, thalamic nucleus, internal and external capsule). Microbleeds abutting grey-white matter junction were classified as juxtacortical.

Data collection and statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean (±SD) unless stated otherwise. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS (V.25; SPSS). Differences with a p<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant, without adjustment for multiple comparisons. Clinical demographic variables between the three patient cohorts were compared using Fisher’s exact test, t-test, or χ2 test as appropriate. Comparisons of CMBs between the CABG, valve replacement and CAA cohorts (total and location-based) were made using analysis of variance and Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference tests. Similar methods were used to calculate statistical difference between the three groups for ratio of CMBs distributed within the SWM and cortex. We performed a receiver operating characteristic curve to assess the validity of ratio of CMB distribution in differentiating between underlying cause (cardiac surgery vs CAA) controlling for anticoagulation as a variable (warfarin or direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC)). Further analysis of the curve and a Mann-Whitney U test were used to generate the optimal ratio cut-off and area under the curve (AUC) respectively. Inter-rater reliability was assessed by Cohen’s kappa coefficient with the kappa value interpreted as follows: κ<0.20 = poor, κ: 0.21–0.40=fair, κ: 0.41–0.60=moderate, κ: 0.61–0.80=good, κ: 0.81–1.0=very good.11 12

Results

Patient demographics

One hundred and twenty-three patients were analysed; 41 post-CABG (33%), 41 post-valve replacement (33%), of which 15 were mechanical (37 %) and 26 tissue (63%); and 41 patients with a history of CAA (33%). The majority of patients were male (61%) with a mean age 74±12 years. Patient characteristics are detailed in table 1.

Table 1.

Patient demographics across the three groups

| Group | Amyloid (n=41) |

CABG (n=41) |

Valve replacement (n=41) | P value |

| Age (years) | 77±10 | 76±11 | 69±13 | 0.005 |

| Sex (females) | 21 (51%) | 11 (27%) | 16 (39%) | 0.12 |

| Hypertension | 26 (63%) | 34 (83%) | 31 (76%) | 0.12 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (17%) | 16 (39%) | 12 (29%) | 0.09 |

| Smoking history | 15 (36%) | 17 (41%) | 19 (46%) | 0.65 |

| Antithrombotic therapy | 21 (54%) | 38 (93%) | 40 (98%) | <0.01 |

| Single antiplatelet | 19 (46%) | 32 (78%) | 12 (29%) | <0.01 |

| Dual antiplatelet | 1 (2%) | 3 (7%) | 3 (7%) | 0.55 |

| Warfarin | 0 | 1 (2%) | 19 (46%) | <0.01 |

| DOAC | 2 (4%) | 2 (5%) | 6 (15%) | 0.18 |

| Past ischaemic stroke | 11 (27%) | 18 (44%) | 20 (48%) | 0.35 |

| Past haemorrhagic stroke | 5 (12%) | 0 | 0 | <0.05 |

| Cognitive impairment | 6 (15%) | 2 (5%) | 2 (5%) | 0.18 |

Values are mean±SD or expressed as percentage.

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant.

The three cohorts were matched for sex, cognitive impairment and cardiovascular risk factors. Valve replacement patients were younger than CABG and CAA patients (p=0.01). Antiplatelet/anticoagulation therapy was significantly different between the three groups (p=<0.01). Predictably, a higher proportion of valve replacement patients were on warfarin therapy, including all patients with mechanical valves. Target INR was not reliably recorded.

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation among the three groups was as follows: CABG n=3 (7%), valve n=9 (22%) and CAA n=6 (15%), p=0.18. Forty of the 123 patient cohort (33%) seen in the TIA clinic had an acute symptomatic MRI lesion. The majority were ischaemic (35/40; 88%) and evenly spread across the three groups (CABG 15, valve 9, CAA 11). The remaining 5 (12%) were acute convexity subarachnoid haemorrhage, all of whom had background CAA. Of the remaining 83 patients, final TIA clinic diagnosis was TIA (n=14; 17%), migraine aura with or without headache (n=18; 22%), seizure (n=4; 5%), non-neurological cause (n=32; 39%) and transient neurological focal episodes (TNFEs) in the setting of CAA (n=15; 18%). The prevalence of such TNFEs within the CAA cohort was 37%, manifesting mostly as transient sensory, motor and speech deficits.

Evidence of previous stroke on FLAIR was seen in 43% (n=53) of the patient cohort with an even spread across the three groups (CABG 18, valve 20, CAA 16; p>0.35). These strokes were ischaemic in all 38 cardiac surgery patients. Among the CAA cohort, 11/16 (69%) were ischaemic and 5/16 (31%) past lobar macrohaemorrhage.

Evaluation of CMBs

Inter-rater reliability

There was a statistically significant agreement between the two investigators with a kappa value of 0.82, indicating ‘very good’ interrater reliability (95% CI 0.61 to 0.98, p<0.01).

CABG versus valve replacement

The frequency, numbers and topographic distribution of CMBs are listed in table 2. CMBs were more prevalent in patients post-valve replacement surgery compared with post-CABG (90 vs 51%, p<0.01) and average microbleed burden was greater (3.9±3.3 vs 1.8±2.3 respectively; p=0.01). Valve replacement subtype (mechanical vs tissue) did not impact CMB burden (mechanical valves n=15, 3.7±2.8 vs tissue n=26, 3.6±3.4; p=0.94). In the total non-CAA cohort, DOAC use was associated with higher CMB burden (n=6, 7.3±4.1) compared with warfarin (n=20, 4.0±3.1; p=0.02.)

Table 2.

Prevalence and distribution of microbleeds between CABG and valve replacement patients

| CABG (n=41) | Valve (n=41) | P value | |

| Prevalence | 51% | 90% | <0.01 |

| Total | 1.8±2.3 | 3.9±3.3 | 0.01 |

| Cortical | 1.0±1.4 | 2.6±2.7 | 0.01 |

| SWM | 0.4±0.9 | 0.8±1.3 | 0.16 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; SWM, subcortical white matter.

Within both cardiac surgery cohorts there was a lobar predominant pattern of microbleed distribution. A lobar-restricted pattern was seen in 26 of the 37 CMB positive patients post-valve replacement (70%) and 14 of the 21 microbleed-positive CABG cohort (67%) p=0.81. In 8 of these patients (four post-CABG, four postvalve) only a single microbleed was evident. A mixed (lobar and deep) pattern was seen in 30% of valve replacement patients (11/37) and 33% of CABG patients (7/21; (p=0.81)). Furthermore 12/18 (15% of the post-surgery cohort) were lobar predominant (defined as ratio of cortical/juxtacortical/subcortical CMBs to deep CMBs >2:1), see table 2. The majority of microbleeds were located within the cortical/juxtacortical tissue (valve replacement: 2.6±2.7, 64% of total; CABG 1±1.4, 56% of total). A smaller, yet significant proportion were located within the SWM (valve replacement: 0.8±1.3, 19% of total; CABG 0.4±0.9, 25% of total), see figure 2. There was a higher prevalence of cortical/juxta-cortical CMBs in valve replacement patients (p=0.01), however, no significant difference for frequency of microbleeds within the SWM (p=0.16) or deep grey matter (p=0.17).

Figure 2.

Susceptibility-weighted imaging from a valve replacement patient demonstrating lobar and subcortical white matter microbleeds. (A) Microbleed within the frontal cortex; (B) Microbleed within the subcortical white matter. White arrows point to microbleed.

Subanalysis of solely patients who were microbleed positive showed no significant difference for total number of microbleed between the valve replacement and CABG groups (4.2±4.1 vs 3.5±2.3, p=0.99). Similarly, there was no significant difference in local CMB burden between CMB positive valve replacement and CABG cohorts, whether (1) strictly cortical (2.7±2.7 vs 2.0±1.0; p=0.98), (2) SWM (0.8±1.3 vs 0.9±0.9; p=0.99); and (3) cerebellar (0.3±0.6 vs 0.2±0.6; p=0.9).

CAA versus CABG/valve replacement

Almost by definition, all patients with CAA had microbleeds evident on imaging. In comparison with the CMB positive valve replacement cohort, CMB burden was higher (18.0±25.9 vs 4.2±4.1 respectively; p<0.01) including strictly cortical burden (15.5±20.4 vs 2.7±2.7, respectively; p<0.01). Findings were similar in comparison with CMB positive CABG patients (18.0±25.9 vs 3.5±2.3 for total burden (p<0.01) and 15.2±20.4 vs 2.0±1.0 for strictly cortical CMB burden (p<0.01). Contrastingly, there was no significant differences in SWM CMB burden (CAA patients 1.5±3.0 vs 0.8±1.3 CMB positive valve replacement patients (p=0.74) and (0.9±0.9) in CMB positive CABG patients (p=0.87)), see table 3. A greater proportion of the total microbleed burden was located within the SWM among the CMB positive cardiac surgery cohort (valve replacement 19%, CABG 25%) compared with patients with CAA (7%).

Table 3.

Correlation between topographic distribution of microbleeds and underlying medical history significant for either CABG, valve replacement or CAA

| Amyloid (n=41) | CABG (n=21) | Valve (n=37) | P value* | CABG-Amyloid† | Valve-Amyloid† | Valve-CABG† | |

| Total CMB | 18.0±25.9 | 3.5±2.3 | 4.1±4.1 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.99 |

| Cortical | 15.5±20.4 | 2.0±1.0 | 2.7±2.7 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.98 |

| SWM | 1.5±3.0 | 0.9±0.9 | 0.8±1.3 | 0.74 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 0.99 |

| Ratio‡ | 0.05±0.08 | 0.26±0.28 | 0.18±0.17 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.01 | 0.25 |

*P value calculated using ANOVA.

†P value calculated using Tukey honest significant difference test.

‡Ratio=SWM/SWM+cortical microbleeds.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; CAA, cerebral amyloid angiopathy; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CMB, cerebral microbleeds; SWM, subcortical white matter.

Superficial siderosis was identified in 20/41 (45%) patients with CAA. Contrastingly, superficial siderosis was not identified in any post-cardiac surgery patient.

Boston criteria ‘false positivity’ and CMB location ratio

In total, 32 (39%) of the 82 post-cardiac surgery patients met both clinical and radiological Modified Boston Criteria for ‘probable CAA’. While target INR or anticoagulation fluctuation was not recorded, sixteen of these patients (50%) were anticoagulated (warfarin n=10 or DOAC n=6). CMB burden did not differ between groups (anticoagulated 4.1±2.5; non-anticoagulated 3.8±1.5), suggesting that anticoagulation does not explain this association.

As we had determined that SWM CMB proportions were higher in cardiac surgery patients than those with CAA, we set out to identify whether a distribution ratio would allow for differentiation. The ratio of SWM:strictly cortical CMBs was substantially lower in CAA patients than CMB positive valve replacement (0.05±0.08 vs 0.18±0.17; p=0.01) or CABG (0.05±0.08 vs 0.26±0.28; p<0.01) patients (p=0.25 for comparison of the two cardiac surgery cohorts). We then analysed this ratio of microbleeds as a distinguishing variable. We found that a ratio of 0.45 was optimal in distinguishing underlying cause of microbleeds, as either in the setting of previous cardiac surgery or probable CAA, in patients presenting with asymptomatic CMBs with a sensitivity of 0.56 and specificity of 0.93 with an AUC=0.71.

Evaluation of white matter disease

A greater proportion of CAA patients showed severe white matter disease on MRI (n=16; 39%) compared with the valve replacement (n=5; 12%) and CABG (n=11; 27%) cohorts. The degree of white matter disease was associated with an increased number of CMBs (online supplemental file 1).

bmjno-2021-000166supp001.pdf (33.3KB, pdf)

Discussion

CMB frequency and location

Our retrospective dual centre cohort study demonstrated that lobar restricted microbleeds are seen in the majority of patients with a past history of cardiac surgery, who presented to our TIA clinic. Further, the majority of these met diagnostic criteria for CAA. However, the pattern of microbleed distribution differed from that of CAA, with proportionally greater CMB burden in the SWM.

The findings of our study are consistent with those of previous acute post-cardiac surgery studies,6 7 and, together with these studies, strongly suggests that cardiac surgery is a cause of lobar-restricted microbleeds, which persist chronically. In a recent study, new SWI-detected CMBs were seen acutely postcardiac surgery in 76% (57/75) of patients in a lobar-predominant distribution (>90% of total microbleeds). A third of this cohort developed >5 new microbleeds.7 Similarly to our study, incidence of post-operative CMBs was higher in patients post valve replacement (86%) than post-CABG (58%), mirroring our findings (90% vs 51%, respectively).7 This study also confirmed that a proportion of these incidental microbleeds can involve the deep matter (18/295 total microbleeds).7 As such, most postcardiac surgery microbleeds are strictly cortical, but the deep white matter is not uncommonly involved.

We found that 39% of our cardiac surgery patients met the Modified Boston Criteria for the diagnosis of probable CAA, and that this was not explained by use of anticoagulation. Such patients are therefore vulnerable to the misdiagnosis of CAA based on radiological changes alone. However, we also identified that a greater proportion of the lobar microbleeds were localised to the deep white matter compared with microbleeds seen in the probable CAA cohort. Therefore, a distribution ratio assessing the proportion of microbleeds within the deep white matter to that of total cortical microbleeds provides reasonable sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing between CMBs secondary to CAA compared with past valvular surgery or CABG. It may help provide reassurance if such patients require anticoagulation or thrombolysis. Further reassurance may be given by the absence of severe white matter disease, and in particular superficial siderosis, which was seen in zero of our postcardiac surgery patients. Further revision of the Boston Criteria for diagnosing CAA could be considered to exclude patients with a history of cardiac bypass surgery.

Mechanisms of CMB formation

The underlying mechanism of microbleed formation during cardiac surgery remains unclear. The most commonly proposed explanation is microembolisation of debris from either cross-clamping of the aorta or manipulation of a calcified valve,6 supported by the increased incidence in patients undergoing valve replacement.6 7 Although length of time on bypass is another correlation.6 7 Our study is potentially consistent with both explanations. We also showed that among our cardiac surgery patients meeting the Boston Criteria for CAA, there was no statistical difference in microbleed burden based on anticoagulation use, thus suggesting that the formation of microbleeds was unlikely a result of anticoagulation and more consistent with an intraoperative cause.

Anticoagulation use

The safety of anticoagulation in patients with asymptomatic CMBs remains undetermined.13 In particular, results from the CROMIS-2 study showed that despite previous findings of increased microbleed burden being associated with greater haemorrhagic complications with long-term anticoagulation, the presence of CMBs is not a contraindication for anticoagulation.14 As such, an evidence-based approach to the safe management of patients with asymptomatic CMBs requiring long-term anticoagulation remains lacking. Larger observational cohort analyses to refine risk prediction based on the underlying cause of CMB are warranted. However, combining the results of our study with the acute post-surgery MRI study of Patel et al, it seems likely that CMBs following cardiac surgery are chronic and do not entail an elevated risk of antithrombotic treatments.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, our study was a convenience sample of patients presenting with transient neurological symptoms to neurovascular clinics. Thus, our study may not be representative of the broader population of patients with a remote past history of either cardiac surgery or CAA. In addition, our findings of a distribution ratio able to differentiate underlying CMB pathology requires further validation among an independent cohort of patients.

Second, we did not collect data on target INR or its variability post cardiac surgery which may have impacted on the incidence of microbleeds among some patients (ie, in the setting of sub or supratherapeutic INR). However, a similar CMB distribution pattern was evident in non-anticoagulated postcardiac surgery patients.

Third, this retrospective study was not designed or powered to assess subsequent rates of symptomatic ICH among the 3 groups of patients, nor was longitudinal stability of CMBs in cardiac surgery patients assessed. Future longitudinal observational studies are therefore needed.

Finally, given the lack of baseline MRI prior to cardiac surgery, we were unable to identify cases of subclinical CAA that may have otherwise been allocated to the post-cardiac surgery cohort but with pre-existing microbleeds.

Conclusion

Lobar restricted or predominant CMBs are a common finding in patients with a history of past cardiac surgery. A significant proportion of these patients meet clinical and radiological Modified Boston Criteria for ‘probable’ CAA. This may lead to an incorrect diagnosis and deleteriously alter antithrombotic management. However, we found that lobar CMBs in cardiac surgery patients were relatively more common within the SWM, and that a distribution ratio of SWM:SWM/cortical microbleeds is reasonably accurate in differentiating the underlying association as either CAA or past cardiac surgery. These findings warrant further investigation among an independent cohort of patients to validate our proposed threshold for a distribution ratio abling to differentiate underlying CMB pathology. If proven, the modified Boston criteria could be further modified to exclude patients with previous cardiac valve replacement or CABG and multiple lobar microbleeds.

Finally, larger observational studies are needed to better delineate pathophysiology and therapeutic implications, especially clarifying the temporal development and longer-term stability of cardiac surgery-associated microbleeds, and providing further reassurance that these patients are not at elevated ICH risk with either antithrombotic or thrombolytic treatments.

Footnotes

Contributors: MDS: project concept and design, imaging analysis, data collection and analysis, write-up. PDS: data analysis. WV: imaging analysis. TK: project concept and design, interpretation of data, critical revisions.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Deidentified participant data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study was performed with the approval of the local ethical review board (Central Adelaide Local Health Network Human Research Ethics Committee).

References

- 1.Renard D. Cerebral microbleeds: a magnetic resonance imaging review of common and less common causes. Eur J Neurol 2018;25:441–50. 10.1111/ene.13544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fanou EM, Coutinho JM, Shannon P, et al. Critical Illness–Associated cerebral microbleeds. Stroke 2017;48:1085–7. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.016289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg SM, Vernooij MW, Cordonnier C, et al. Cerebral microbleeds: a guide to detection and interpretation. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:165–74. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70013-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai HH, Tsai1LK, Chen Y. Correlation of cerebral microbleed distribution to amyloid burden in patients with primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Sci Rep 2017;17:44715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberg SM, Charidimou A. Diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: evolution of the Boston criteria. Stroke 2018;49:491–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michałowska I, Furmanek MI, Smaga E, et al. Evaluation of brain lesions in patients after coronary artery bypass grafting using MRI with the emphasis on susceptibility-weighted imaging. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol 2015;12:1–7. 10.5114/kitp.2015.50560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel N, Banahan C, Janus J, et al. Perioperative cerebral microbleeds after adult cardiac surgery. Stroke 2019;50:336–43. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.023355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim PPC, Nasman BW, Kinne EL, et al. Cerebral microhemorrhage: a frequent magnetic resonance imaging finding in pediatric patients after cardiopulmonary bypass. J Clin Imaging Sci 2017;7:27. 10.4103/jcis.JCIS_29_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cordonnier C, Potter GM, Jackson CA, et al. Improving interrater agreement about brain microbleeds: development of the Brain Observer MicroBleed Scale (BOMBS). Stroke 2009;40:94–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.526996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, et al. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer’s dementia and normal aging. American Journal of Roentgenology 1987;149:351–6. 10.2214/ajr.149.2.351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med 2012;22:276–82. 10.11613/BM.2012.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 1960;20:37–46. 10.1177/001316446002000104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charidimou A, Shoamanesh A, Al-Shahi Salman R, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, cerebral microbleeds and implications for anticoagulation decisions: the need for a balanced approach. Int J Stroke 2018;13:117–20. 10.1177/1747493017741384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson D, Ambler G, Shakeshaft C, et al. Cerebral microbleeds and intracranial haemorrhage risk in patients anticoagulated for atrial fibrillation after acute ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack (CROMIS-2): a multicentre observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:539–47. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30145-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjno-2021-000166supp001.pdf (33.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Anonymised data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.

Deidentified participant data are available on reasonable request.