Abstract

Background

Alzheimer's disease and related forms of dementia are becoming increasingly prevalent with the aging of many populations. The diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease relies on tests to evaluate cognition and discriminate between individuals with dementia and those without dementia. The Mini‐Cog is a brief, cognitive screening test that is frequently used to evaluate cognition in older adults in various settings.

Objectives

The primary objective of this review was to determine the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog for detecting dementia in a community setting.

Secondary objectives included investigations of the heterogeneity of test accuracy in the included studies and potential sources of heterogeneity. These potential sources of heterogeneity included the baseline prevalence of dementia in study samples, thresholds used to determine positive test results, the type of dementia (Alzheimer's disease dementia or all causes of dementia), and aspects of study design related to study quality. Overall, the goals of this review were to determine if the Mini‐Cog is a cognitive screening test that could be recommended to screen for cognitive impairment in community settings.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE (OvidSP), EMBASE (OvidSP), PsycINFO (Ovid SP), Science Citation Index (Web of Science), BIOSIS previews (Web of Science), LILACS (BIREME), and the Cochrane Dementia Group's developing register of diagnostic test accuracy studies to March 2013. We used citation tracking (using the database’s ‘related articles’ feature, where available) as an additional search method and contacted authors of eligible studies for unpublished data.

Selection criteria

We included all cross‐sectional studies that utilized the Mini‐Cog as an index test for the diagnosis of dementia when compared to a reference standard diagnosis of dementia using standardized dementia diagnostic criteria. For the current review we only included studies that were conducted on samples from community settings, and excluded studies that were conducted in primary care or secondary care settings. We considered studies to be conducted in a community setting where participants were sampled from the general population.

Data collection and analysis

Information from studies meeting the inclusion criteria were extracted including information on the characteristics of participants in the studies. The quality of the studies was assessed using the QUADAS‐2 criteria and summarized using risk of bias applicability and summary graphs. We extracted information on the diagnostic test accuracy of studies including the sensitivity, specificity, and 95% confidence intervals of these measures and summarized the findings using forest plots. Study specific sensitivities and specificities were also plotted in receiver operating curve space.

Main results

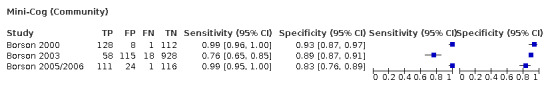

Three studies met the inclusion criteria, with a total of 1620 participants. The sensitivities of the Mini‐Cog in the individual studies were reported as 0.99, 0.76 and 0.99. The specificity of the Mini‐Cog varied in the individual studies and was 0.93, 0.89 and 0.83. There was clinical and methodological heterogeneity between the studies which precluded a pooled meta‐analysis of the results. Methodological limitations were present in all the studies introducing potential sources of bias, specifically with respect to the methods for participant selection.

Authors' conclusions

There are currently few studies assessing the diagnostic test accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in community settings. The limited number of studies and the methodological limitations that are present in the current studies make it difficult to provide recommendations for or against the use of the Mini‐Cog as a cognitive screening test in community settings. Additional well‐designed studies comparing the Mini‐Cog to other brief cognitive screening tests are required in order to determine the accuracy and utility of the Mini‐Cog in community based settings.

Keywords: Aged; Aged, 80 and over; Humans; Alzheimer Disease; Alzheimer Disease/diagnosis; Cognitive Dysfunction; Cognitive Dysfunction/diagnosis; Cross-Sectional Studies; Dementia; Dementia/diagnosis; Memory, Short-Term; Mental Status and Dementia Tests; Sensitivity and Specificity

Plain language summary

A brief cogntive screening test (Mini‐Cog) for the assessment of possible dementia

With the aging of our populations there are increasing numbers of older adults with memory complaints and possible dementia. Identifying older adults who have dementia is important in order to help with planning their care needs and starting dementia specific treatments. In order to diagnose dementia, healthcare professionals or other service providers rely on tests of memory and other areas of cognition in combination with additional investigations. Brief memory tests, such as the Mini‐Cog, may be useful as screening tests to help identify those individuals that might benefit from further evaluation in order to determine if dementia is present. The Mini‐Cog is a brief cognitive test that involves an assessment of an older person's ability to recall three words and draw a clock. In this review, we searched medical literature databases to identify studies which evaluated how well the Mini‐Cog is able to distinguish between individuals who have dementia and those who do not have dementia when compared to in‐depth evaluation by dementia specialists. Our review focussed on those studies that were conducted in community based settings. We identified three unique randomised controlled studies that evaluated the Mini‐Cog. In these studies the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog varied and importantly there were some potential limitations within the studies which may have led to an overestimation of the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog. Based on the information that we obtained from our review, we felt that further research into the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog was required before it could be recommended for routine use for identifying dementia in community settings.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Mini‐Cog for the detection of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias within a community setting.

| Title: Mini‐Cog for the detection of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias within a community setting | ||||

| Population | Community‐dwelling older adults | |||

| Setting | Community setting was intended to represent a population based sample of older adults in which the Mini‐Cog may be used as a screening tests. Studies that included populations where participants were identified from community settings but then evaluated using the Mini‐Cog and reference standard were included in the review | |||

| Index test | Mini‐Cog either administered as a single test or Mini‐Cog scores for the clock drawing test and three‐word delayed recall were derived from larger tests | |||

| Reference Standard | Clinical diagnosis of dementia using any recognized classification system | |||

| Studies | Cross‐sectional studies, case control studies were excluded | |||

| Study | Accuracy (95% CI) | Number of participants | Dementia prevalence | Implications |

| Borson 2000 | Sensitivity: 0.99 (0.96 to 1.00) Specificity: 0.93 (0.87 to 0.97) Positive LR: 14.88 Negative LR: 0.0083 |

249 | 51.8% | Excluded individuals with questionable dementia (CDR = 0.5) from study population, accuracy of Mini‐Cog in diagnosing mild dementia not determined which may have overestimated the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog. The prevalence of dementia is higher than would be anticipiated from most community based studies |

| Borson 2003 | Sensitivity: 0.76 (0.65 to 0.85) Specificity: 0.89 (0.87 to 0.91) Positive LR: 6.92 Negative LR: 0.07 |

1119 | 6.8% | Excluded individuals with questionable dementia (CDR = 0.5) from analysis which may have resulted in an overestimation of the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog |

| Borson 2005/2006 | Sensitivity: 0.99 (0.95 to 1.00) Specificity: 0.83 (0.76 to 0.89) Positive LR: 5.78 Negative LR: 0.01 |

252 | 44.4% | Individuals referred from community agencies to Alzheimer's centre. The prevalence of dementia is higher that would be expected from most community based studies, which may have affected the test accuracy of the Mini‐Cog |

Background

Target condition being diagnosed

Alzheimer's disease and related forms of dementia are common among older adults with a prevalence of 8% in individuals over the age of 65 years, increasing to a prevalence of approximately 43% in adults aged 85 years and older (Thies 2012). Given the increasing number of older adults in most developing countries, the prevalence of dementia is expected to increase considerably in the coming years. Currently, an estimated 35 million individuals are diagnosed with dementia worldwide and this number is expected to increase to 150 million by 2050 (Prince 2013). Alzheimer's disease and related forms of dementia are incurable and result in considerable direct and indirect costs, both in terms of formal health care and lost productivity from both the affected individual and their caregivers (Thies 2012). Despite being incurable, there are several benefits to diagnosing Alzheimer's disease and related dementias early in the disease course. Most individuals with dementia, and their caregivers, would prefer to know a diagnosis of dementia, and earlier diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease allows these individuals to make decisions regarding future planning while they retain the capacity to do so (Prorok 2013). A diagnosis of dementia is also necessary to access certain services and support for individuals and their caregivers, and pharmacological treatments such as cholinesterase inhibitors (Birks 2006; Rolinski 2012) or memantine (McShane 2006; Wilkinson 2011) may help slow the progression of the disease.

The diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease is clinical and based on a history of decline in cognitive functioning, in memory and with deficits in at least one other area of cognitive functioning (for example apraxia, agnosia or executive dysfunction). There must be a decline from a previous level of functioning which results in significant social or occupational impairment (American Psychiatric Association 2000; McKhann 2011). A definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease can only be achieved at autopsy, but a clinical diagnosis using standardized criteria is associated with a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 70% when compared to autopsy‐proven cases (Knopman 2001).

Approximately 50% to 80% of all individuals with dementia are ultimately classified as having Alzheimer's disease (Blennow 2006; Brunnström 2009; CSHA 1994). While patients with dementias share common characteristics, subtle differences can help to provide a diagnosis in the absence of neuropathological examination. A smaller proportion of dementias are associated with dementia with Lewy bodies (Brunnström 2009) or Parkinson's disease dementia (Aarsland 2005). Dementia with a mixed etiology is present in 10% to 30% of cases (Brunnström 2009; Crystal 2000; Feldman 2003). Vascular dementias may occur more abruptly or present with a step‐wise decline in cognitive functions over time and account for approximately 15% to 20% of dementias (Brunnström 2009; CSHA 1994; Feldman 2003; Lobo 2000). Patients experiencing frontotemporal dementia account for a smaller proportion of dementias (4% to 8%) and often present with problems in executive function and changes in behaviour, while memory is relatively preserved (Brunnström 2009; Greicius 2002). Distinguishing between different types of dementias is important as the management and prognosis of dementia can vary depending on the dementia subtype.

Index test(s)

The Mini‐Cog is a brief cognitive test consisting of two components, a delayed three‐word recall and the clock drawing test (Borson 2000). The Mini‐Cog was initially developed in a community setting to provide a relatively brief cognitive screening test. Different scoring algorithms were tested to determine which combination had the optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity (McCarten 2011; Scanlan 2001). The Mini‐Cog takes approximately three to five minutes to complete in routine practice (Borson 2000; Holsinger 2007; Scanlan 2001). The Mini‐Cog has been reported to have little potential for bias in terms of education or language (Borson 2000; Borson 2005).

Clinical pathway

Dementia develops over a trajectory of several years. There is a presumed period when people are asymptomatic although disease pathology may be accumulating. Individuals or their relatives may first notice subtle impairments of short‐term memory. Gradually, more cognitive deficits become apparent with difficulty completing complex tasks such as management of finances or medications. At this point the attribution of cognitive and memory symptoms to normal aging may cause delays in the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer's disease. This underscores the need for accurate, brief cognitive screening tests to help distinguish the cognitive changes associated with normal aging from the changes that might indicate dementia. Most older adults with memory complaints will first present to their general practitioner or other primary healthcare provider. Primary healthcare providers may then administer brief cognitive screening tests and, depending on the results of the cognitive screening, an individual may then have additional investigations or cognitive tests to determine if dementia is present. In some settings, a positive result on a brief cognitive screening test may result in a referral to a dementia specialist such as a neurologist, geriatrician or geriatric psychiatrist. Some countries have also recommended that brief cognitive screening tests be administered to all older adults in order to help screen for undetected or asymptomatic cognitive impairment (Cordell 2013), although there is controversy about the utility of population based screening.

Alternative test(s)

We are not including alternative tests in this review because there are currently no standard tests available for the diagnosis of dementia.

The Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group (CDCIG) is conducting a series of diagnostic test accuracy reviews of biomarkers and scales (see list below). Although the CDCIG is conducting reviews on individual tests compared to a reference standard, we plan to compare our results in an overview.

Positron emission tomography F‐2‐fluoro‐2‐deoxy‐D‐glucose (18F‐FDG‐PET)

Positron emission tomography Pittsburgh compound‐C (11C‐PIB‐PET)

Structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI)

Neuropsychological tests (Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE); Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA))

Informant interviews (Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE); AD8)

Apolipoprotein e4 (APOE e4)

Fluoropropyl‐carbomethoxy‐iodophenyl‐tropane single‐photon emission tomography (FP‐CIT SPECT)

Rationale

Cognitive diagnostic tests are required to assess cognition and assist in diagnosing conditions such as mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation conducted by psychologists or dementia specialists such as general psychiatrists, geriatric psychiatrists, geriatricians or neurologists would be the most accurate clinical procedure for assessing cognition and diagnosing dementia in older adults. However, these specialized resources are scarce and expensive and as such are not practical for routine use in the evaluation of cognitive complaints (Pimlott 2009; Yaffe 2008). While there are some cognitive tests that can be performed by healthcare providers who are not dementia specialists, many of these tests are time consuming and may not be practical to use routinely in primary care or community settings (Brodaty 2006; Harris 2009; Pimlott 2009). As such, brief but relatively accurate cognitive screening tests are required for healthcare providers in community settings to identify individuals who may require more in‐depth evaluation of cognition. It has been recommended that brief cognitive screening tests for community settings should be simple, take less than five minutes to administer, have a misclassification rate similar to or better than the MMSE and have a negative value similar to or better than the MMSE (Brodaty 2006).

Utilizing a standard diagnostic or screening tests also promotes effective communication between healthcare providers. The sensitivity and specificity of such tests vary depending upon the setting in which they are utilized (Holsinger 2007). Some studies have found that the majority of older adults with dementia in primary care are undiagnosed (Boustani 2005; Sternberg 2000). In addition, many primary care providers have difficulty in accurately diagnosing dementia, and mild dementia is particularly under‐diagnosed (van den Dungen 2011). Early diagnosis and treatment of dementia can have clinical and economic benefits for the patient, their community and the public healthcare system (Bennett 2003; Thies 2012). Accurate diagnosis of dementia is also important in order to initiate dementia therapeutics including both non‐pharmacological and pharmacological treatments such as cholinesterase inhibitors (Birks 2006; Rolinski 2012) or memantine (McShane 2006). A brief and simple cognitive screening test that could be used in routine community settings would allow healthcare professionals or lay people to initially screen older adults for the presence of dementia. Individuals that screen positive for dementia on the Mini‐Cog may then be further investigated for the presence of dementia using additional cognitive tests or other investigations. Given that the Mini‐Cog is brief, widely available and easy to administer (Brodaty 2006), it may be well suited for use as a cognitive screening test in community settings. Other cognitive screening tests that may also be suitable for use in the community or primary care settings include the MMSE (Holsinger 2007), the General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (Brodaty 2002) or the Memory Impairment Screen (Buschke 1999). The current review examined the diagnostic accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in community settings. Separate diagnostic test accuracy reviews are being undertaken for primary and secondary care settings.

Objectives

To determine the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog for detecting dementia in a community setting.

Secondary objectives

To investigate the heterogeneity of test accuracy in the included studies and potential sources of heterogeneity. These potential sources of heterogeneity include the baseline prevalence of dementia in study samples, thresholds used to determine positive test results, the type of dementia (Alzheimer's disease dementia or all causes of dementia), and aspects of study design related to study quality.

We will also identify gaps in the evidence where further research is required.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all cross‐sectional, population based studies with a well‐defined population that utilized the Mini‐Cog as an index cognitive screening test compared to a reference standard. The included studies utilized a reference standard to determine whether or not a dementia was present. The included studies also had to utilize the Mini‐Cog as a screening test and not for confirmation of diagnosis. While some studies utilized the test on patients with a previously known diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or a related dementia, when possible, studies administered the index and reference tests to individuals where their diagnosis was not already known.

Participants

Study participants were sampled from a community setting and may or may not have been ultimately diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease or a related dementia. Participants may have had cognitive complaints or dementia at baseline although their cognitive status should not have been known to the individual administering the Mini‐Cog or the reference standard. Studies on participants with a developmental disability which prevented them from completing the Mini‐Cog were excluded. Studies including participants in either primary or secondary care settings have been excluded as these are the topics of other reviews.

Index tests

Mini‐Cog test

The Mini‐Cog consists of a three‐word recall task and the clock drawing test. The standard scoring system involves assigning a score of 0 to 3 points on the word recall task for the correct recall of 0, 1, 2 or 3 words, respectively. The clock drawing test is scored as being either 'normal' or 'abnormal'. A positive test on the Mini‐Cog (that is dementia) is assigned if either the delayed recall score is 0 out of 3 or if the delayed recall score is either 1 or 2 and the clock drawing test is abnormal. A score of 3 on the delayed recall or 1 to 2 on delayed recall with a normal clock drawing is a negative test (that is no dementia) (Borson 2000).

Studies had to include the results of the Mini‐Cog.

Target conditions

Target conditions included any stage of Alzheimer's disease or other types of dementia including vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson's disease dementia or frontotemporal dementia.

Reference standards

While a definitive diagnosis can only be made post‐mortem at autopsy, there are clinical criteria for diagnosis of most forms of dementia. All dementia diagnostic criteria require that an individual have impairment in multiple areas of cognition that result in impairment in daily functioning and are not caused by either the effects of a substance or a general medical condition. The standard clinical diagnostic criteria commonly used for Alzheimer's disease dementia include the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS‐ADRDA) criteria for probable or possible dementia (McKhann 1984; McKhann 2011), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (American Psychiatric Association 2000) or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD 2010) criteria. Diagnostic criteria for other types of dementia include the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and Association Internationale pour la Recherché et l'Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINCDS‐AIREN) criteria for vascular dementia (Roman 1993), and standard criteria for dementia with Lewy bodies (McKeith 2005) and frontotemporal dementia (McKhann 2001). The evaluation for dementia should also include a number of laboratory investigations, many of which are useful for excluding alternative diagnoses (Feldman 2008). Additional procedures to help confirm the diagnosis include specific findings on neuroimaging (either computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging). These investigations are typically used to confirm the diagnosis, rather than rule out the possibility of dementia. While these clinical criteria for dementia were considered the reference standard for the purposes of our review, the sensitivity and specificity of these clinical reference standards may vary when compared to neuropathological criteria for dementia (Nagy 1998).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1950 to March 2013), EMBASE (OvidSP) (1974 to 04 March 2013), PsycINFO (OvidSP) (1806 to March week 1 2013), Science Citation Index (Web of Science) (1945 to March 2013), BIOSIS Previews (Web of Science) (1926 to March 2013), and the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group's developing register of diagnostic test accuracy studies. See Appendix 1 for details of the sources searched, the search strategies used and the number of hits retrieved, and to view the 'generic' search that is run regularly for the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group's registry.

We made no attempt to restrict studies based on sampling frame or setting in the searches developed. This was to maximize sensitivity and allow inclusion on the basis of population based sampling to be assessed at testing (see below, Selection of studies). We did not use search filters (collections of terms aimed at reducing the number needed to screen) as an overall limiter because those published have not proved sensitive enough (Beynon 2013; Whiting 2011a). We did not apply any language restriction to the electronic searches; we used translation services as necessary.

A single researcher with extensive experience of systematic reviews performed the searches. Two independent authors conducted the screening of abstracts and titles.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of all relevant studies for additional relevant studies as this has been found to be a useful method to minimize missing potentially relevant studies in complex reviews (Greenhalgh 2005; Horsley 2011). We also used these studies to search the electronic databases to identify additional studies through the use of the related article feature. We asked research groups authoring studies used in the analysis for unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

To be included, studies had to:

make use of the Mini‐Cog as a cognitive diagnostic tool;

include patients from a community setting who may or may not have dementia or cognitive complaints; and

clearly explain how a diagnosis of dementia was either confirmed according to a reference standard such as the DSM IV‐TR or NINCDS‐ADRDA at the same time or within the same four‐week time period that the Mini‐Cog was administered. Formal neuropsychological evaluation was not required for a diagnosis of dementia.

We first selected articles based on abstract and title. Two independent authors located selected articles and assessed them for inclusion. We settled disagreements by involving a third author.

Data extraction and management

Two study authors extracted the following data from all included studies.

Author, journal and year of publication.

Scoring algorithm used for the Mini‐Cog including cut‐points used to define a positive screen. Method of Mini‐Cog administration, including who administered and interpreted the test, and their training and whether or not the raters of the Mini‐Cog and reference standard were blinded to the results of the other test.

Reference criteria and method used to confirm diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or a related dementia.

Baseline demographic characteristics of the study population including age, gender, ethnicity, severity of presenting symptoms, comorbidity, educational achievement, language, baseline prevalence of dementia, country, APOE status, methods of participant recruitment and sampling procedures.

Length of time between administration of index test (Mini‐Cog) and reference standard.

The sensitivity and specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios of the index test in defining dementia.

Version of translation (if applicable).

Prevalence of dementia in the study population.

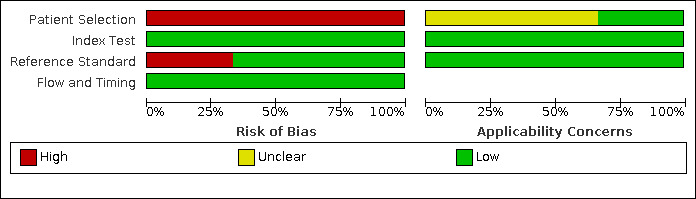

Assessment of methodological quality

We used the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS‐2) criteria to assess data quality (Whiting 2011b). The QUADAS‐2 criteria contain assessment domains for patient selection, index test, reference test, and flow and timing. Each domain has suggested signalling questions to assist with the 'risk of bias' assessment for each domain. The potential risk of bias associated with each domain is rated as being at high, low, or uncertain risk of bias. In addition, we determined an assessment of the applicability of the study to the review study question for each domain using the guide provided in the QUADAS‐2. We utilized a standardized 'risk of bias' template to extract data on the risk of bias for each study using the form provided by the UK Support Unit for Cochrane Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. See Appendix 1 for details. We summarized quality assessment results using the methodological quality summary table and methodological summary graph in RevMan 5.3 (RevMan 2012).

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

We performed statistical analysis as per the Cochrane guidelines for diagnostic test accuracy reviews (Macaskill 2010). Study specific two‐by‐two tables were constructed using information extracted from the included studies. We planned to construct separate two‐by‐two tables for Mini‐Cog results for both Alzheimer's disease dementia and all‐cause dementia.

We used data from two‐by‐two tables to calculate the study specific sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios as well as measures of statistical uncertainty (for example 95% confidence intervals). We obtained rates of false positives, true positives, false negatives, and true negatives from RevMan. We presented data from each study graphically by plotting sensitivities and specificities on a coupled forest plot. The study specific sensitivities and specificities were also plotted in the receiver operating curve (ROC) space. We planned to use the bivariate random‐effects model approach for meta‐analysis of the sensitivity and specificity (Reitsma 2005). If multiple thresholds were reported for the Mini‐Cog we planned to use the hierarchical summary ROC (HSROC) method of Rutter and Gastconis for meta‐analysis (Rutter 2001). While meta‐analysis was planned for this review, there were a limited number of studies all of which had methodological limitations and as such meta‐analysis was not undertaken with the final results.

Investigations of heterogeneity

The potential sources of heterogeneity that we planned to examine included baseline prevalence of cognitive impairment in the target population, the cut‐points used to determine a positive test result, the type of dementia (Alzheimer's disease dementia or all‐cause dementia) and aspects related to study quality. To investigate the effects of the sources of heterogeneity, we performed a descriptive analysis by visual examination of the forest plot of sensitivity and specificity and the ROC plot. As meta‐analysis was not undertaken in this review we were unable to perform any statistical analyses of heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analyses

We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis in order to investigate the influence of study quality on the overall diagnostic accuracy of the Mini‐Cog test by omitting studies that were at high risk of bias on any of the QUADAS‐2 domains. We also planned to determine the impact of individual studies on summary outcome measures. However, due to the small number of studies we were not able to conduct a meta‐analysis and these sensitivity analyses were not undertaken.

Assessment of reporting bias

We did not investigate reporting bias because of current uncertainty about how it operates in test accuracy studies and the interpretation of existing analytical tools such as funnel plots (Deeks 2005; van Ernst 2014).

Results

Results of the search

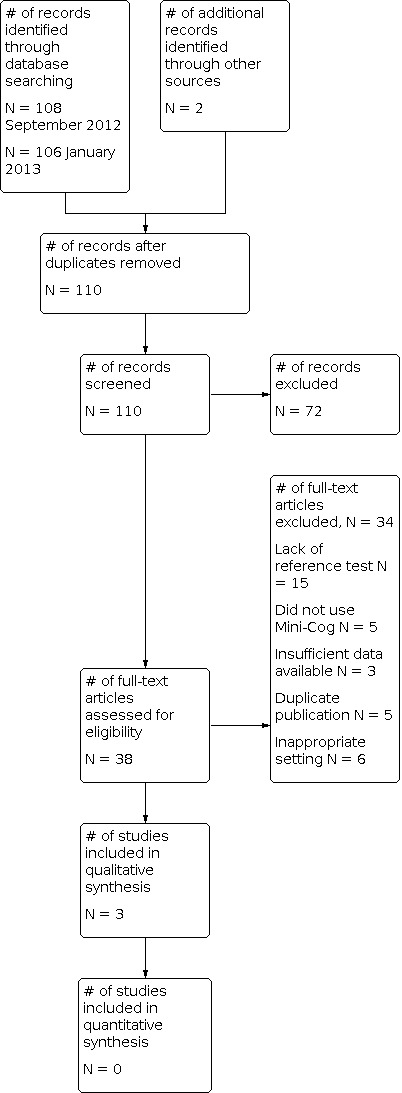

The results of the literature search are outlined below in Figure 1. A review of the electronic databases yielded 108 articles in September 2012 and 106 in January 2013, and an additional 2 were identified through handsearches. After de‐duplication this left 110 articles. All 110 were independently assessed by two authors and there were no disagreements about either the number of studies eligible for inclusion or data results.

1.

Study flow diagram.

After initial evaluation, 38 studies were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 34 were excluded. Reasons for exclusion included the lack of a reference standard (N = 15), no use of the Mini‐Cog (N = 5), duplicate publication (N = 5), inappropriate setting (N = 6) and insufficient available data (N = 3).

The search identified three independent studies from four different study reports. A summary of the characteristics of the included studies are provided in Table 2. Notably, all of the studies were published by the same author group. Borson 2000 was the first study to use the Mini‐Cog, sampling a multilingual population of older adults identified through community social services agencies. Of the 249 participants, 124 were non‐English speaking. The study aimed to compare the newly‐developed Mini‐Cog with the MMSE and Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI). The diagnosis of dementia was for all‐cause dementia although the majority of participants in this study had Alzheimer's disease.

1. Characteristics of included studies.

| Study ID | Country | Participants (N) | Setting | Mini‐Cog scoring | Dementia diagnosis | Dementia prevalence | Notes |

| Borson 2000 | Seattle, US | 249 | Community sample assessed at memory clinic | Standard scoring | DSM‐IV, NINCDS‐ADRDA | 51.8% | Excluded participants with MCI |

| Borson 2003 | Pennsylvania, US | 1119 | Random sample of persons in geographic region | Standard scoring | DSM‐III R, NINCDS‐ADRDA | 6.8% | Excluded participants with MCI |

| Borson 2005/2006 | Seattle, US | 252 | Community sample referred for cognitive screening | Standard scoring | DSM‐IV, NINCDS‐ADRDA | 44.4% |

Borson 2003 included the largest sample size, utilizing a random sample of 1119 older adults enrolled in the Monogahela Valley Independent Elders Survey (MoVIES). The study was a post hoc analysis, using combined data from standard neuropsychological testing to create the Mini‐Cog. The study found that the Mini‐Cog, when compared to the MMSE at a cut‐point of 25, had similar sensitivity and specificity for differentiating between 'possibly impaired' and 'probably normal'. The diagnosis of dementia in this study was specifically for Alzheimer's disease dementia.

Two reports (Borson 2005/2006) used the same study sample. The 2005 report again compared the Mini‐Cog and MMSE, determining that the tools were similar in detecting clinically significant cognitive impairment. The 2006 report re‐examined the data in an attempt to compare the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog when compared to spontaneous detection by primary care physicians. The diagnosis of dementia in this study was Alzheimer's disease dementia.

Further details concerning the design, setting, population, target condition and reference standard of the four included studies can be found in the Characteristics of included studies.

Methodological quality of included studies

The results of the QUADAS‐2 assessment for each of the three included studies are presented in Figure 2. All studies were judged as being at high risk of bias in the patient selection domain. For Borson 2000 and Borson 2005/2006 it was unclear whether or not a consecutive, random sampling of patients was employed, and all studies failed to avoid inappropriate exclusions for a variety of reasons (incomplete health records, visual or motor impairment, failure to meet minimum education requirements). In addition, the reference standard assessment used in Borson 2000 was administered and interpreted with knowledge of the Mini‐Cog results, introducing a high risk of bias.

2.

Risk of bias and applicability concerns graph: review authors' judgements about each domain presented as percentages across included studies.

Two of the studies excluded individuals with questionable dementia from the analysis (Borson 2000; Borson 2003). Therefore the analysis of the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in these studies was limited to individuals with normal cognition and those with certain diagnoses of dementia. It was likely that this may introduce a spectrum bias to the results as the Mini‐Cog would only be comparing individuals who had no dementia to those with more severe cognitive impairment.

A few additional features common to all the included studies may have introduced other potential sources of bias. First, all studies were published by the same author group. Second, all studies used a version of the Mini‐Cog that was derived from components of larger neuropsychological tests (that is using the three‐word recall from the MMSE). The performance of the Mini‐Cog when the component tests were administered by themselves as compared to when the results of the Mini‐Cog were derived from the results of more comprehensive testing may also have affected the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog.

Findings

There were four study reports on three unique study populations that were selected for the final review (Borson 2000; Borson 2003. Borson 2005/2006). The characteristics of these studies are summarized in the Characteristics of included studies section of this review. Additional features of these studies are also summarized in Table 1. Two of the publications reported on the same study sample (Borson 2005/2006) and information from both publications were used to complete the quality assessment for this study. All of the studies were completed by the same research group. Two studies recruited participants from community settings, who were then assessed at a memory clinic (Borson 2000; Borson 2005/2006) and the third study evaluated a random sample of community dwelling individuals from a defined geographic area (Borson 2003). Two of the studies also excluded individuals with mild cognitive impairment or possible dementia, only including individuals who were cognitively normal or had dementia in the final analysis (Borson 2000; Borson 2003). The baseline prevalence of dementia in the overall study samples varied from 6.8% (Borson 2003) to 51.8% (Borson 2000). All studies utilized the original scoring system proposed by Borson et al (Borson 2000).

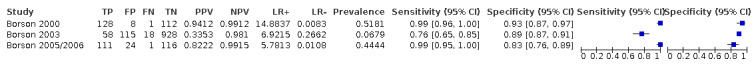

Meta‐analysis of the diagnostic test accuracy of the Mini‐Cog was planned, although due to the small number of studies and methodological limitations of included studies we did not perform a meta‐analysis. The extracted data, including sensitivity, specificity and forest plots for the Mini‐Cog in each study, are summarized in Table 1 and in the forest plot presented in Figure 3. The sensitivities of the Mini‐Cog in the individual studies were reported as 0.99 (Borson 2000), 0.76 (Borson 2003) and 0.99 (Borson 2005/2006). The specificity of the Mini‐Cog varied in the individual studies and was 0.93 (Borson 2000), 0.89 (Borson 2003) and 0.83 (Borson 2005/2006). The values for the positive and negative predictive values and positive and negative liklihood ratios for the individual studies are summarized in the Table 1 and in Figure 3.

3.

Forest plot of 1 Mini‐Cog (Community).

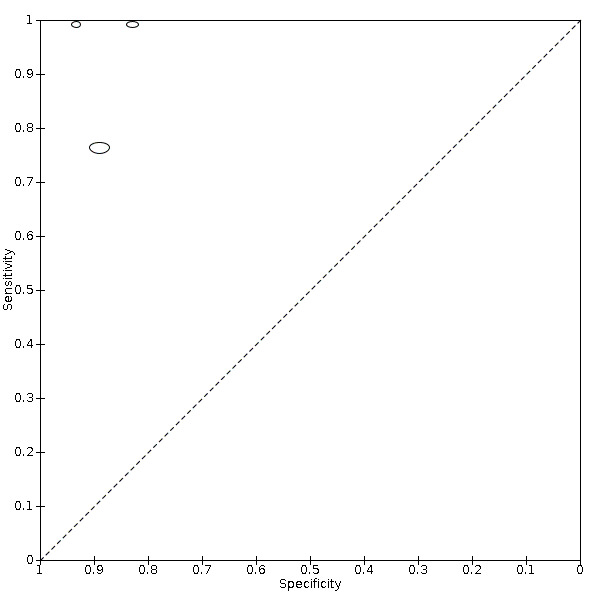

The small number of studies and overall poor quality of the included studies precluded the use of meta‐analysis to arrive at pooled estimates for the diagnostic test accuracy. The study specific sensitivity and specificity were plotted in a forest plot (Figure 3) and the summary test characteristics of the individual studies were plotted in a graph (Figure 4).

4.

Plot of study sensitivity and specificity in receiver operating curve space.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The Mini‐Cog is a commonly utilized brief cognitive screening test that has been recommended as a potential cognitive screening test for community settings. Our review found that there are only three studies that evaluated the Mini‐Cog in community settings. These three studies were all conducted by the original developers of the Mini‐Cog. The sensitivity and specificity of the Mini‐Cog in these studies were relatively high in two of the studies, which may be influenced by significant methodological limitations that may have led to overestimation of the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog due to the exclusion of individuals with mild cognitive impairment or possible dementia. The results of this review suggest that the Mini‐Cog may be useful in distinguishing between individuals with moderate to severe cognitive impairment when compared to individuals with normal cognition. Overall, additional well‐designed studies with large sample sizes are required to better evaluate the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in order to determine whether it can be recommended as a screening test for dementia.

Strengths and weaknesses of the review

There are several strengths to this review. We used a standardized search strategy to identify potential articles including unpublished studies, which would reduce the risk of publication bias. These search methods included a single‐concept search across multiple sources along with a search of the Cochrane Collaboration diagnostic test accuracy registry. This sensitive search approach may have identified studies that would have potentially been overlooked using less rigorous search methods. Our review also provided a detailed assessment of the quality using the QUADAS‐2, which provides important information about potential sources of bias in the included studies and provides context for the interpretation of the reported results.

Some weaknesses of this review are related to the small number of studies that have been conducted. Also, the methodological limitations of the included studies limits the conclusions that can be drawn from the current studies that have evaluated the Mini‐Cog in community settings. In particular, two of the three studies that were included in this review (Borson 2000; Borson 2003) excluded individuals with questionable or uncertain dementia from the analysis, which may have led to overestimation of the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog. The Mini‐Cog was only evaluated in a single country and its accuracy for detecting dementia in community settings outside of the United States is not known. Also, all of the studies included in this review derived the Mini‐Cog scores from components of larger neuropsychological tests. It is likely that the Mini‐Cog will frequently be utilized differently in routine clinical settings and the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog when performed as a single test may differ when compared to when it is derived from a larger test. In particular, the amount of time that passes between the administration of the three words and the recall of these three words may differ with these different methods of administration, which may affect the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog for detecting dementia.

Applicability of findings to the review question

Our review question was to determined the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in the diagnosis of dementia in a community setting. Of the three studies identified in this review, only one (Borson 2003) study was conducted using methods that would closely replicate how the Mini‐Cog would typically be used in community based settings. Therefore, the results of only a single study are available on the use of the Mini‐Cog in a manner that most closely matched the research question of this review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

At the present time there is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of the Mini‐Cog as a screening test for dementia in community settings. Individuals in community settings who are being screened for cognitive impairment are likely to have a wide range of cognitive abilities, ranging from normal cognitive aging to advanced dementia. The information currently available on the diagnostic test accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in community settings is limited by the poor quality of the studies. In particular, two of the three studies which evaluated the Mini‐Cog excluded individuals with mild cognitive impairment or possible dementia from the study populations, which likely leads to overestimation of the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog for detecting milder forms of cognitive impairment or dementia. Therefore, the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog for diagnosing mild dementia is unknown at this time, although it would be anticipated that the Mini‐Cog would be less accurate for detecting mild dementia than more advanced dementia. Two of the studies included in our review included study populations with more advanced dementia. Although there is limited information to support the Mini‐Cog as an accurate brief screening test, the Mini‐Cog has been recommended as a potential initial screening test for primary care settings (Cordell 2013) and a systematic review concluded that the Mini‐Cog had acceptable test performance for screening of cognitive impairment (Lin 2013).

Another consideration with the use of the Mini‐Cog in clinical practice relates to the study population in which it is used. The prevalence of dementia among adults aged 65 years and older in community settings is typically reported to be between 5% and 8% (CSHA 1994; Matthews 2013), in contrast the prevalence of dementia in two of the studies which evaluated the Mini‐Cog were 44.4% and 51.8%. The high prevalence of dementia in these studies also likely affected the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog, overestimating the positive predictive value of the Mini‐Cog in these populations when compared to a more typical community sample with a lower prevalence of dementia.

In community settings where the prevalence of dementia is low, screening for cognitive impairment has been recommended by some health administrators and the Mini‐Cog has been recommended as one potential initial cognitive screening tool among others such as the Memory Impairment Screen and General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (Cordell 2013). In the current review direct comparisons of the diagnostic test accuracy of the Mini‐Cog when compared to other cognitive tests were not undertaken. Separate reviews of the diagnostic test accuracy of some of these screening tests are being completed (Creavin 2014; Harrison 2014; Hendry 2014). Therefore, the relative accuracy of the Mini‐Cog when compared to longer cognitive screening tests are not known and clinicians will need to consider the known strengths and limitations of the Mini‐Cog when compared to other, longer cognitive tests.

There are, however, some potential reasons why clinicians may consider using the Mini‐Cog despite these limitations. The Mini‐Cog is a very brief screen and as such it can be utilized in settings where there may be limited time or resources available to clinicians to complete a brief cognitive screening test which may guide further investigations. The Mini‐Cog is also easy to administer from memory and doesn't require any special forms or access to a computer to complete, which is another reason that it may have some utility for clinicians in some clinical situations.

Implications for research.

There are several opportunities for additional research on the diagnostic test accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in community settings. A large, well‐designed community based study evaluating the diagnostic test accuracy of the Mini‐Cog would provide important additional information about the the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog. It would be important in future studies to include a more representative sample of community dwelling older adults who have a broader range of underlying cognitive abilities including individuals with normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment, early dementia and more advanced dementia to better understand the accuracy of the Mini‐Cog in these specific populations. We did not compare the Mini‐Cog against other brief cognitive screening tests such as the MMSE that are subjects of separate Cochrane reviews (Creavin 2014; Harrison 2014; Hendry 2014). The potential advantage of the Mini‐Cog is that it is very brief, even when compared to other cognitive screening tests. Whether the Mini‐Cog is as accurate when compared to other brief screening tests was not evaluated in the current review but may be important to study in future reviews.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 June 2021 | Amended | The title and objectives have been changed to make it clear that screening tests alone cannot give a diagnostic formulation. There have been no other changes. Similar changes have been made to other Cochrane diagnostic test accuracy reviews relating to dementia. These changes were made by Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement in conjunction with the Cochrane Mental Health and Neuroscience Network and the review authors, following feedback from a group of dementia researchers, expressing concern that the review titles implied that short screening tests could make a diagnosis of a dementia subtype like Alzheimer’s disease. This interpretation was not intended, but the revised titles and objectives clarify the reviews’ scope. Further details are available here: https://dementia.cochrane.org/our-reviews/feedback-about-reviews |

| 15 June 2021 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Title and objectives have changed for clarification |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 11, 2013 Review first published: Issue 2, 2015

Appendices

Appendix 1. QUADAS‐2

| Domain | Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | Flow and timing |

| Description | Describe methods of patient selection: describe included patients (prior testing, presentation, intended use of index test and setting) | Describe the index test and how it was conducted and interpreted | Describe the reference standard and how it was conducted and interpreted | Describe any patients who did not receive the index test(s) and/or reference standard or who were excluded from the 2 x 2 table (refer to flow diagram): describe the time interval and any interventions between index test(s) and reference standard |

| Signalling questions (yes/no/unclear) | Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Was a case control design avoided? Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? |

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? |

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? |

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Did all patients receive the same reference standard? Were all patients included in the analysis? |

| Risk of bias: (high/low/unclear) |

Could the selection of patients have introduced bias? | Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? | Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? | Could the patient flow have introduced bias? |

| Concerns regarding applicability: (high/low/unclear) |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? | Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? | Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? | — |

Anchoring statements to assist with assessment of risk of bias

Domain 1: Patient selection

Risk of bias: could the selection of patients have introduced bias? (high, low, unclear)

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled?

Where sampling is used, the methods least likely to cause bias are consecutive sampling or random sampling, which should be stated and/or described. Non‐random sampling or sampling based on volunteers is more likely to be at high risk of bias.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Was a case‐control design avoided?

Case control study designs have a high risk of bias, but sometimes they are the only studies available especially if the index test is expensive and/or invasive. Nested case control designs (systematically selected from a defined population cohort) are less prone to bias but they will still narrow the spectrum of patients that receive the index test. Study designs (both cohort and case control) that may also increase bias are those designs where the study team deliberately increase or decrease the proportion of subjects with the target condition, for example a population study may be enriched with extra dementia subjects from a secondary care setting.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions?

We will automatically grade the study as unclear if exclusions are not detailed (pending contact with study authors). Where exclusions are detailed, we will grade the study as 'low risk' if exclusions are felt to be appropriate by the review authors. Certain exclusions common to many studies of dementia are: medical instability; terminal disease; alcohol or substance misuse; concomitant psychiatric diagnosis; other neurodegenerative condition. However if 'difficult to diagnose' groups are excluded this may introduce bias, so exclusion criteria must be justified. For a community sample we would expect relatively few exclusions. We will label post hoc exclusions 'high risk' of bias.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Applicability: are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? (high, low, unclear)

The included patients should match the intended population as described in the review question. If not already specified in the review inclusion criteria, setting will be particularly important – the review authors should consider population in terms of symptoms; pre‐testing; potential disease prevalence. We will classify studies that use very selected subjects or subgroups as having low applicability, unless they are intended to represent a defined target population, for example, people with memory problems referred to a specialist and investigated by lumbar puncture.

Domain 2: Index test

Risk of bias: could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? (high/low/unclear)

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the reference standard?

Terms such as 'blinded' or 'independently and without knowledge of' are sufficient and full details of the blinding procedure are not required. This item may be scored as 'low risk' if explicitly described or if there is a clear temporal pattern to the order of testing that precludes the need for formal blinding, that is all (neuropsychological test) assessments were performed before the dementia assessment. As most neuropsychological tests are administered by a third party, knowledge of dementia diagnosis may influence their ratings; tests that are self administered, for example using a computerized version, may have less risk of bias.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Were the index test thresholds pre‐specified?

For neuropsychological scales there is usually a threshold above which subjects are classified as 'test positive'; this may be referred to as threshold, clinical cut‐off or dichotomisation point. Different thresholds are used in different populations. A study is classified as at higher risk of bias if the authors define the optimal cut‐off post hoc based on their own study data. Certain papers may use an alternative methodology for analysis that does not use thresholds and these papers should be classified as not applicable.

Weighting: low risk of bias

Were sufficient data on (neuropsychological test) application given for the test to be repeated in an independent study?

Particular points of interest include method of administration (for example self completed questionnaire versus direct questioning interview); nature of informant; language of assessment. If a novel form of the index test is used, for example a translated questionnaire, details of the scale should be included and a reference given to an appropriate descriptive text, and there should be evidence of validation.

Weighting: low risk of bias

Applicability: are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? (high, low, unclear)

Variations in the length, structure, language, and/or administration of the index test may all affect applicability if they vary from those specified in the review question.

Domain 3: Reference standard

Risk of bias: could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? (high, low, unclear)

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition?

Commonly used international criteria to assist with clinical diagnosis of dementia include those detailed in DSM‐IV and ICD‐10. Criteria specific to dementia subtypes include but are not limited to NINCDS‐ADRDA criteria for Alzheimer's dementia; McKeith criteria for Lewy Body dementia; Lund criteria for frontotemporal dementias; and the NINDS‐AIREN criteria for vascular dementia. Where the criteria used for assessment are not familiar to the review authors and the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group this item should be classified as 'high risk of bias'.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test?

Terms such as 'blinded' or 'independent' are sufficient and full details of the blinding procedure are not required. This may be scored as 'low risk' if explicitly described or if there is a clear temporal pattern to order of testing, i.e. all dementia assessments performed before (neuropsychological test) testing.

Informant rating scales and direct cognitive tests present certain problems. It is accepted that informant interview and cognitive testing is a usual component of clinical assessment for dementia, however specific use of the scale under review in the clinical dementia assessment should be scored as high risk of bias.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Was sufficient information on the method of dementia assessment given for the assessment to be repeated in an independent study?

Particular points of interest for dementia assessment include the training and expertise of the assessor, whether additional information was available to inform the diagnosis (for example neuroimaging, other neuropsychological test results), and whether this was available for all participants.

Weighting: variable risk, but high risk if method of dementia assessment not described

Applicability: are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? (high, low, unclear)

There is the possibility that some methods of dementia assessment, although valid, may diagnose a far smaller or larger proportion of subjects with disease than in usual clinical practice. In this instance the item should be rated as having poor applicability.

Domain 4: Patient flow and timing (Figure 1)

Risk of bias: could the patient flow have introduced bias? (high, low, unclear)

Was there an appropriate interval between the index test and reference standard?

For a cross‐sectional study design, there is potential for the subject to change between assessments, however dementia is a slowly progressive disease, which is not reversible. The ideal scenario would be a same‐day assessment, but longer periods of time (for example, several weeks or months) are unlikely to lead to a high risk of bias. For delayed‐verification studies the index and reference tests are necessarily separated in time given the nature of the condition.

Weighting: low risk of bias

Did all subjects receive the same reference standard?

There may be scenarios where subjects who score 'test positive' on the index test have a more detailed assessment for the target condition. Where dementia assessment (or reference standard) differs between subjects this should be classified as high risk of bias.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Were all subjects included in the final analysis?

Attrition will vary with study design. Delayed verification studies will have higher attrition than cross‐sectional studies due to mortality, and it is likely to be greater in subjects with the target condition. Dropouts (and missing data) should be accounted for. Attrition that is higher than expected (compared to other similar studies) should be treated as a high risk of bias. We have defined a cut‐off of greater than 20% attrition as being high risk but this will be highly dependent on the length of follow‐up in individual studies.

Weighting: high risk of bias

Appendix 2. Sources searched and search strategies

| Source | Search strategy | Hits retrieved |

| ALOIS DTA (CDCIG Specialised Register) (see below for detailed explaination of what is contained within the ALOIS register) | Mini‐cog | Sept 2012: 19 Jan 2013: 0 |

| 1. MEDLINE In‐Process and other non‐indexed citations and MEDLINE 1950 to present (January 2013) (Ovid SP) | 1. "mini‐Cog".ti,ab. 2. minicog.ti,ab. 3. (MCE and (cognit* OR dement* OR screen* OR Alzheimer*)).ti,ab. 3. or/1‐3 |

Sept 2012: 91 Jan 2013: 12 |

| 2. EMBASE 1974‐2013 January 02 (OvidSP) |

1. "mini‐cog*".mp. 2. minicog*.mp. 3. 1 or 2 |

Sept 2012: 96 Jan 2013: 37 |

| 3. PsycINFO 1806 to January week 1 2013 (OvidSP) |

1. minicog*.mp. 2. "mini‐cog*".mp. 3. 1 or 2 |

Sept 2012: 69 Jan 2013: 28 |

| 4. Biosis previews 1926 to present (January 2013) (ISI Web of Knowledge) | Topic=("mini‐cog*" OR "minicog*") Timespan=All Years. Databases=BIOSIS Previews. Lemmatization=On |

Sept 2012: 33 Jan 2013: 7 |

| 5. Web of Science and conference proceedings (1945 to January 2013) | Topic=("mini‐cog*" OR "minicog*") Timespan=All Years. Databases=BIOSIS Previews. Lemmatization=On |

Sept 2012: 93 Jan 2013: 20 |

| 6. LILACS (BIREME) (January 2013) | "mini‐cog" OR minicog [Words] | Sept 2012: 2 Jan 2013: 2 |

| TOTAL before de‐duplication | Sept 2012: 403 Jan 2013: 106 |

|

| TOTAL after de‐dupe and first‐assess | Sept 2012: 108 Jan 2013: 41 |

|

In addition to the above single concept search based on the Index test, the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group run a more complex, multi‐concept search each month primarily for the identification of diagnostic test accuracy studies of neuropsychological tests. Where possible the full texts of the studies identified are obtained. This approach is expected to help identify those papers where the index test of interest (in this case Mini‐cog) is used and the paper contains usable data but where Mini‐cog was not alluded to in the report's citation.

The MEDLINE strategy used is below. Similar strategies are also run in EMBASE and PsycINFO.

The MEDLINE generic search run for the CDCIG DTA register:

1. "word recall".ti,ab.

2. ("7‐minute screen" OR “seven‐minute screen”).ti,ab.

3. ("6 item cognitive impairment test" OR “six‐item cognitive impairment test”).ti,ab.

4. "6 CIT".ti,ab.

5. "AB cognitive screen".ti,ab.

6. "abbreviated mental test".ti,ab.

7. "ADAS‐cog".ti,ab.

8. AD8.ti,ab.

9. "inform* interview".ti,ab.

10. "animal fluency test".ti,ab.

11. "brief alzheimer* screen".ti,ab.

12. "brief cognitive scale".ti,ab.

13. "clinical dementia rating scale".ti,ab.

14. "clinical dementia test".ti,ab.

15. "community screening interview for dementia".ti,ab.

16. "cognitive abilities screening instrument".ti,ab.

17. "cognitive assessment screening test".ti,ab.

18. "cognitive capacity screening examination".ti,ab.

19. "clock drawing test".ti,ab.

20. "deterioration cognitive observee".ti,ab.

21. ("Dem Tect" OR DemTect).ti,ab.

22. "object memory evaluation".ti,ab.

23. "IQCODE".ti,ab.

24. "mattis dementia rating scale".ti,ab.

25. "memory impairment screen".ti,ab.

26. "minnesota cognitive acuity screen".ti,ab.

27. "mini‐cog".ti,ab.

28. "mini‐mental state exam*".ti,ab.

29. "mmse".ti,ab.

30. "modified mini‐mental state exam".ti,ab.

31. "3MS".ti,ab.

32. “neurobehavio?ral cognitive status exam*”.ti,ab.

33. "cognistat".ti,ab.

34. "quick cognitive screening test".ti,ab.

35. "QCST".ti,ab.

36. "rapid dementia screening test".ti,ab.

37. "RDST".ti,ab.

38. "repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status".ti,ab.

39. "RBANS".ti,ab.

40. "rowland universal dementia assessment scale".ti,ab.

41. "rudas".ti,ab.

42. "self‐administered gerocognitive exam*".ti,ab.

43. ("self‐administered" and "SAGE").ti,ab.

44. "self‐administered computerized screening test for dementia".ti,ab.

45. "short and sweet screening instrument".ti,ab.

46. "sassi".ti,ab.

47. "short cognitive performance test".ti,ab.

48. "syndrome kurztest".ti,ab.

49. ("six item screener" OR “6‐item screener”).ti,ab.

50. "short memory questionnaire".ti,ab.

51. ("short memory questionnaire" and "SMQ").ti,ab.

52. "short orientation memory concentration test".ti,ab.

53. "s‐omc".ti,ab.

54. "short blessed test".ti,ab.

55. "short portable mental status questionnaire".ti,ab.

56. "spmsq".ti,ab.

57. "short test of mental status".ti,ab.

58. "telephone interview of cognitive status modified".ti,ab.

59. "tics‐m".ti,ab.

60. "trail making test".ti,ab.

61. "verbal fluency categories".ti,ab.

62. "WORLD test".ti,ab.

63. "general practitioner assessment of cognition".ti,ab.

64. "GPCOG".ti,ab.

65. "Hopkins verbal learning test".ti,ab.

66. "HVLT".ti,ab.

67. "time and change test".ti,ab.

68. "modified world test".ti,ab.

69. "symptoms of dementia screener".ti,ab.

70. "dementia questionnaire".ti,ab.

71. "7MS".ti,ab.

72. ("concord informant dementia scale" or CIDS).ti,ab.

73. (SAPH or "dementia screening and perceived harm*").ti,ab.

74. or/1‐73

75. exp Dementia/

76. Delirium, Dementia, Amnestic, Cognitive Disorders/

77. dement*.ti,ab.

78. alzheimer*.ti,ab.

79. AD.ti,ab.

80. ("lewy bod*" or DLB or LBD or FTD or FTLD or “frontotemporal lobar degeneration” or “frontaltemporal dement*).ti,ab.

81. "cognit* impair*".ti,ab.

82. (cognit* adj4 (disorder* or declin* or fail* or function* or degenerat* or deteriorat*)).ti,ab.

83. (memory adj3 (complain* or declin* or function* or disorder*)).ti,ab.

84. or/75‐83

85. exp "sensitivity and specificity"/

86. "reproducibility of results"/

87. (predict* adj3 (dement* or AD or alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

88. (identif* adj3 (dement* or AD or alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

89. (discriminat* adj3 (dement* or AD or alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

90. (distinguish* adj3 (dement* or AD or alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

91. (differenti* adj3 (dement* or AD or alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

92. diagnos*.ti.

93. di.fs.

94. sensitivit*.ab.

95. specificit*.ab.

96. (ROC or "receiver operat*").ab.

97. Area under curve/

98. ("Area under curve" or AUC).ab.

99. (detect* adj3 (dement* or AD or alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

100. sROC.ab.

101. accura*.ti,ab.

102. (likelihood adj3 (ratio* or function*)).ab.

103. (conver* adj3 (dement* or AD or alzheimer*)).ti,ab.

104. ((true or false) adj3 (positive* or negative*)).ab.

105. ((positive* or negative* or false or true) adj3 rate*).ti,ab.

106. or/85‐105

107. exp dementia/di

108. Cognition Disorders/di [Diagnosis]

109. Memory Disorders/di

110. or/107‐109

111. *Neuropsychological Tests/

112. *Questionnaires/

113. Geriatric Assessment/mt

114. *Geriatric Assessment/

115. Neuropsychological Tests/mt, st

116. "neuropsychological test*".ti,ab.

117. (neuropsychological adj (assess* or evaluat* or test*)).ti,ab.

118. (neuropsychological adj (assess* or evaluat* or test* or exam* or battery)).ti,ab.

119. Self report/

120. self‐assessment/ or diagnostic self evaluation/

121. Mass Screening/

122. early diagnosis/

123. or/111‐122

124. 74 or 123

125. 110 and 124

126. 74 or 123

127. 84 and 106 and 126

128. 74 and 106

129. 125 or 127 or 128

130. exp Animals/ not Humans.sh.

131. 129 not 130

Data

Presented below are all the data for all of the tests entered into the review.

Tests. Data tables by test.

| Test | No. of studies | No. of participants |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Mini‐Cog (Community) | 3 | 1620 |

1. Test.

Mini‐Cog (Community)

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Borson 2000.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient Sampling | Patients were identified through community social service agencies and evaluated at the University of Washington's Alzheimer's Disease Research Center. Excluded individuals with Clinical Dementia Rating = 0.5 | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Patients were selected regardless of language spoken, education, race. Patients were excluded when they had a history of severe brain injury, CNS infection, active alcohol or drug abuse history, poorly controlled diabetes or kidney, heart, respiratory failure Participant mean age (SD), dementia: 77.9 (9.1), no dementia: 69.0 (9.0) Gender: 173 women, 76 men Education: varied Dementia: 129, no dementia: 120 Mean MMSE Scores (SD), dementia: 14.1 (6.7), no dementia: 27.5 (2.4) |

||

| Index tests | Mini‐Cog using original scoring and Mini‐Cog score was derived from the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument | ||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Clinical diagnosis of dementia based on criteria of DSM‐IV, CERAD and NINCDS‐ADRDA | ||

| Flow and timing | All patients were reported | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | |||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Unclear | ||

| Was a case‐control design avoided? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | No | ||

| Could the selection of patients have introduced bias? | High risk | ||

| Are there concerns that the included patients and setting do not match the review question? | Unclear | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test (All tests) | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | Yes | ||

| Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? | Low risk | ||

| Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? | Low concern | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | No | ||

| Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? | High risk | ||

| Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the question? | Low concern | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Yes | ||

| Could the patient flow have introduced bias? | Low risk | ||

Borson 2003.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient Sampling | Age stratified, random sample for 65 year old and older from population of 17,000 adults across 23 communities in Pennsylvannia. Individuals with questionable dementia (CDR = 0.5) were excluded from the analysis | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Patients were English speakers, 65 year old and older with > 6 years of formal education and living in the community

Participant age: mean age (SD) 73.1 (6)

Gender: 611 women, 508 men

Education: median 12 years, minimum 6 years of formal education

Dementia: 76, no dementia: 1043 Mean MMSE Scores (SD): dementia 21.3 (5.8), no dementia 27.8 (1.9) |

||

| Index tests | Mini‐Cog scored according to Borson 2000 | ||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Clinical diagnosis of dementia, as per the criteria of DSM‐IV‐TR and NINDS‐ADRDA | ||

| Flow and timing | Complete data for all patients | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | |||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Yes | ||

| Was a case‐control design avoided? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | No | ||

| Could the selection of patients have introduced bias? | High risk | ||

| Are there concerns that the included patients and setting do not match the review question? | Low concern | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test (All tests) | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Unclear | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | Yes | ||

| Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? | Low risk | ||

| Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? | Low concern | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | Unclear | ||

| Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? | Low risk | ||

| Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the question? | Low concern | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Yes | ||

| Could the patient flow have introduced bias? | Low risk | ||

Borson 2005/2006.

| Study characteristics | |||

| Patient Sampling | Non‐random sampling of patients referred to University of Washington Alzheimer Disease Research Center Satellite by community service agencies and other outreach methods | ||

| Patient characteristics and setting | Heterogeneous community sample that was over‐represented with ethnic minority elderly. Patients with motor or sensory impairment precluding administration of cognitive screens were excluded. Patients with fragmentary outpatient records were excluded Participant age: unclear Gender: unclear Education: unclear Severity of cognitive impairment, Alzheimer's disease dementia: 112, no dementia:140 |

||

| Index tests | Mini‐Cog derived from a larger neuropsychological test battery, the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instruments | ||

| Target condition and reference standard(s) | Clinical diagnosis of dementia based on the criteria of DSM‐IV, NINCDS‐ADRDA. Patients were evaluated by consensus process that excluded cognitive testing | ||

| Flow and timing | Complete data on all patients | ||

| Comparative | |||

| Notes | |||

| Methodological quality | |||

| Item | Authors' judgement | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns |

| DOMAIN 1: Patient Selection | |||

| Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? | Unclear | ||

| Was a case‐control design avoided? | Yes | ||

| Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? | No | ||

| Could the selection of patients have introduced bias? | High risk | ||

| Are there concerns that the included patients and setting do not match the review question? | Unclear | ||

| DOMAIN 2: Index Test (All tests) | |||

| Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? | Yes | ||

| If a threshold was used, was it pre‐specified? | Yes | ||

| Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias? | Low risk | ||

| Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? | Low concern | ||

| DOMAIN 3: Reference Standard | |||

| Is the reference standards likely to correctly classify the target condition? | Yes | ||

| Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index tests? | Unclear | ||

| Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias? | Low risk | ||

| Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the question? | Low concern | ||

| DOMAIN 4: Flow and Timing | |||

| Was there an appropriate interval between index test and reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Did all patients receive the same reference standard? | Yes | ||

| Were all patients included in the analysis? | Yes | ||

| Could the patient flow have introduced bias? | Low risk | ||

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Costa 2012 | Study did not have gold standard evaluation using standardized diagnostic criteria. Unclear whether participants were without dementia or cognitive complaints at baseline |

| Lorentz 2003 | Insufficient information. |

| Scanlan 2004 | Study did not have gold standard evaluation using standardized diagnostic criteria |

| Scanlan 2007 | Study did not have gold standard evaluation using standardized diagnostic criteria |

| Tappen 2010 | Study did not have gold standard evaluation using standardized diagnostic criteria. Unclear if all participants were without dementia or cognitive complaints at baseline |

Contributions of authors

BF wrote a draft of the protocol and contributed to revisions of the protocol. CC, SG, ANS, NS, NH, NS, VN and DS contributed to revising the protocol and contributing the final protocol. All authors contributed to final review and have approved it for publication.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support provided

External sources

-

Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canada

This project was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant KAL#114493

Declarations of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Borson 2000 {published data only}