Abstract

Purpose:

Radioimmunotherapy (RIT) delivered through the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has been shown to be a safe and promising treatment for leptomeningeal metastases. Pharmacokinetic models for intra-Ommaya anti-GD2 monoclonal antibody 131I-3F8 have been proposed to improve therapeutic effect while minimizing radiation toxicity. In this study, we now apply pharmacokinetic modeling to intra-Ommaya 131I-omburtamab (8H9), an anti-B7-H3 antibody which has shown promise in RIT of leptomeningeal metastases.

Methods:

Serial CSF samples were collected and radioassayed from 61 patients undergoing a total of 177 intra-Ommaya administrations of 131I-omburtamab for leptomeningeal malignancy. A two-compartment pharmacokinetic model with 12 differential equations was constructed and fitted to the radioactivity measurements of CSF samples collected from patients. The model was used to improve anti-tumor dose while reducing off-target toxicity. Mathematical endpoints were (a) the area under the concentration curve (AUC) of the tumor-bound antibody, AUC[CIAR(t)], (b) the AUC of the unbound “harmful” antibody, AUC[CIA(t)], and (c) the therapeutic index, AUC[CIAR(t)]÷AUC[CIA(t)].

Results:

The model fit CSF radioactivity data well (mean R=96.4%). The median immunoreactivity of 131I-omburtamab matched literature values at 69.1%. Off-target toxicity (AUC[CIA(t)]) was predicted to increase more quickly than AUC[CIAR(t)] as a function of 131I-omburtamab dose, but the balance of therapeutic index and AUC[CIAR(t)] remained favorable over a broad range of administered doses (0.48–1.40mg or 881–2592MBq). While anti-tumor dose and therapeutic index increased with antigen density, the optimal administered dose did not. Dose fractionization into two separate injections increased therapeutic index by 38%, and splitting into 5 injections by 82%. Increasing antibody immunoreactivity to 100% only increased therapeutic index by 17.5%.

Conclusion:

The 2-compartmental pharmacokinetic model when applied to intra-Ommaya 131I-omburtamab yielded both intuitive and non-intuitive therapeutic predictions. The potential advantage of further dose fractionization warrants clinical validation.

Clinical Trial Registration:

Keywords: Radioimmunotherapy, Cerebrospinal fluid, Pharmacokinetics, Neuroblastoma, 131I-omburtamab

INTRODUCTION

Many tumors develop leptomeningeal metastases, where cancer cells invade the meninges of the central nervous system and spread through the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). There is no standard of care for cure, and in most cases, palliation is possible only with external beam radiation. Thus, leptomeningeal metastases constitute an unmet need, and novel therapies are urgently needed. While CSF bathes the entire brain and spinal cord, providing a conduit for cancer spread, it is also an accessible portal for anti-cancer treatments [1]. Radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies like 131I-3F8 [2] and 131I-omburtamab (formerly 8H9) [3, 4] have been administered directly into the CNS [5] or into the CSF via Ommaya reservoirs (intrathecal/intra-Ommaya administration) [6–8] to bypass the blood-brain barrier. These treatments have proven safe [9] and promising in subsets of patients including those with high-risk neuroblastoma metastatic to the CNS or leptomeninges [8, 10]; While 3F8 targets GD2, a glycolipid antigen expressed by normal neurons and abundant on tumors, omburtamab targets B7-H3, a lower-density glycoprotein with restricted expression in tumor tissues. 131I-omburtamab received FDA breakthrough therapy designation in 2017. After intra-Ommaya injection into the lateral ventricles, the administered antibodies flow unidirectionally through midline ventricles, through the subarachnoid space before being discharged into the arachnoid villi. Along the way, the antibodies bind to antigens on the surface of tumor cells. Multiple models have been proposed for the pharmacokinetics of 131I-3F8 in CSF [11, 12]. Our most recently proposed model, a two-compartment model with the lateral ventricles representing the first compartment, had the best correlation with patient CSF sampling data [11]. In this report, we adapt this two-compartment model to intra-Ommaya 131I-omburtamab, using CSF activity measurements from clinical samples collected after 177 131I-omburtamab administrations in 61 patients. We then use this model to make predictions on anti-tumor dose and therapeutic index when dose, schedule, tumor antigen density, antibody immunoreactivity, CSF volume and CSF clearance were optimized.

METHODS

Model construction

Our 131I-omburtamab pharmacokinetic model follows a similar design as our published two-compartment model for 131I-3F8 pharmacokinetics [11]. The administered activity was assumed to be proportional to the mass dose of the antibody (1 mg=1850 MBq). In this model, the antibody is infused into the ventricular compartment, flows into the subarachnoid compartment, and eventually exits from the CSF (Figure 1). While within the CSF, the 131I-omburtamab antibody binds specifically to the FG loop of B7-H3 [13], an antigen widely expressed among human malignancies [14]. As a mouse IgG1, omburtamab has minimal affinity for human Fc-receptors. Additionally, nonspecific binding was also incorporated; a constant 1% was assumed since the amount had minimal impact in prior literature when varied from 0–10% [11]. The mathematical formulation of the model was derived from mass action laws using previously measured association and dissociation constants of omburtamab [13] (second-order for binding of antigen to antibody) and the antigen density quantitated using fifty-seven tumor cell lines. The twelve differential equations (see supplemental Governing Concentration ODEs) were solved using the numerical computing software MATLAB® (Version 2017a, Mathworks®, Natick, Massachusetts). At time t, the model outputs included 1) the tumor-bound “useful” radioactivity concentration (MBq/mL) CIAR(t), and 2) the unbound “harmful” radioactivity concentration (MBq/mL) CIA(t).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the two-compartment CSF model. Reprinted by permission from “Two-compartment model of radioimmunotherapy delivered through cerebrospinal fluid” by He et al., 2011., Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 38(2):334–42 [11].

Model verification

Model verification was completed using the entire available cohort (no selective filter applied) of 2044 CSF data samples of 177 radiolabeled antibody administrations collected between October 2004 and August 2015 from 61 pediatric and adult patients treated with intra-Ommaya 131I-omburtamab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00089245). All patients had a histologically confirmed diagnosis of high-risk or recurrent CNS/leptomeningeal malignancy known, or documented by immunohistochemistry, to express B7-H3. Patients received 74 MBq (2 mCi, 0.4 mg) of 124I-omburtamab or 131I-omburtamab for dosimetry, followed by 370–2590 MBq (10–70 mCi, 0.2 mg–1.4 mg) of 131I-omburtamab per injection in a 3+3 dose-escalation Phase-I trial (~1mL volume; 1850 MBq/mg [50 mCi/mg] antibody) via an Ommaya reservoir using sterile techniques. Serial CSF samples were obtained for radioactivity counting in an 131I-calibrated scintillation well counter at 6 time points (170 of 177 treatment studies had between 4 and 8 samples), i.e. 0, 5, 15, and 30 minutes, 2–4 hours, 18–24, and 44–48 hours post-injection. At each time point, two CSF samples were measured and averaged to provide a robust estimate of the unbound antibody concentration. Gross dosimetry/PET scans were published previously [10], but were not used here because the CSF does not have enough tumor cells to do dosimetry and guided meningeal biopsy is life-threatening and costly. Finally, 131I-omburtamab antibody immunoreactivities from 61 injections (given from 2009 to 2011) are summarized. All data collection was in compliance with institutional review board and hospital guidelines. Model parameters for ventricular volume and CSF clearance were estimated for each treatment study by minimizing the least square differences between ventricular CSF radioactivity/mL after 131I-omburtamab had diffused and model predictions for the portion of CIA(t) in their ventricular space, CIAV(t) (~6 data points for 2 parameters). The distribution of fitted parameters and model-to-data correlations across the 177 treatment studies was analyzed.

Optimization procedures and operationalization of benefit and harm

Median values of omburtamab immunoreactivity, antigen density, and patient fitted parameters were inserted into the model to investigate how 131I-omburtamab pharmacokinetics was affected when these parameters were changed. As in previous work [11, 12], we used two main metrics: (a) the area under the curve over time (AUC) of tumor bound or “useful” radioactivity concentration, AUC[CIAR(t)]; (b) the therapeutic index (TI), defined as the ratio of AUC[CIAR(t)] to the AUC of unbound “harmful” radioactivity concentration AUC[CIA(t)]. Optimizing both simultaneously could be done by maximizing their product, TI×AUC[CIAR(t)]. The clinical relevance of AUC[CIAR(t)] and TI first proposed in the model [11, 12] was extensively discussed in a recent review [1]. Note that therapeutic index (TI) is synonymous with therapeutic ratio (TR), terminology used in past literature [11, 12].

The defining equations of the above metrics are below (integrals are numerically computed using the trapezoidal method):

We simulated the effects of immunoreactivity, total dose, dose schedule (both dose frequency and dose spacing), antibody binding kinetics, and CSF clearance on AUC[CIAR(t)] and TI to find potential ways of increasing treatment effectiveness. Additionally, antigen concentration on tumor cells, CSF volume, and CSF clearance were analyzed to determine the variability of treatment effectiveness across different patient characteristics. Finally, these 131I-omburtamab optimization findings were compared to the previously reported results from the one-compartment and two-compartment 131I-3F8 models [11, 12].

RESULTS: MODEL CREATION

131I-omburtamab Immunoreactivity

Data from 61 injections in the clinical trial had a median immunoreactivity of 69.1% (mean=68.02%, S.E.=2.35%), identical to the previously reported 69% immunoreactivity in in vitro 131I-omburtamab experiments [13] (See Supplemental Immunoreactivity Data Analysis and Supplemental Figure 1).

Tumor Surface Antigen Density (NR) and Concentration (R0)

The B7-H3 antigen density (target for omburtamab), NR, measured from fifty-seven tumor cell lines (32 neuroblastoma (NB); see supplemental Antigen Concentration Data Analysis), was widely distributed with median 3.521×104 antigens/cell, ranging from 1.0475×103 to 2.4543×105 antigens/cell (Figure 2). Notably, B7-H3 antigen density was significantly lower than that of GD2 (target for 3F8) reported previously as 105–107 antigens/cell [12].

Fig. 2.

B7-H3 antigen density, NR, on human tumor cell lines (neuroblastoma (NB) or non-neuroblastoma) cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37C in 5% CO2. 8H9 was labeled with Alexa Fluor® 488 according to manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Catalog number A10235). B7-H3 quantitation was done using Quantum™ Simply Cellular® anti-Mouse beads (Bangs Laboratories, Catalog Code 815). A) By cell line B) Histogram (logarithmic scale).

Methodology for calculating R0 (antigen/mL) from NR (antigens/cell) was based on calculations previously done for GD2 antigens during the 3F8 analysis [12] (Supplemental Antigen Concentration Data Analysis). Except as noted, for our optimization calculations, we used R0=1.1937×1012 antigens/mL, the value calculated using the median neuroblastoma NR and a subarachnoid surface 3% covered with tumor cells (fcov) (Supplemental Table 1), while noting how changes in R0 affected the predictions.

Assessing Model Fit, CSF Clearance and CSF Volume

The model fit for the 177 131I-omburtamab administrations was generally good with few exceptions (Supplemental Figure 2) and a median R of 99.1766% (mean R=96.4266%) (Supplemental Figure 3C–D). The median fitted clearance (11.97mL/hr) and ventricular volume (36.61mL) were reasonable (for rough comparison, healthy adult literature values are 20mL/hr and 30mL [15, 16]) (Supplemental Figure 3A–B). Additionally, the multiple injections of the same patients were used to show the level of reproducibility of the parameters (Supplemental Figure 3E–F). The following optimizations were computed using the fitted parameter values.

RESULTS: OPTIMIZATION

Effects of 131I-omburtamab Immunoreactivity (IR)

We found that immunoreactivity effects on unbound antibody radiation AUC[CIA(t)] were negligible (<0.1% change across 10–90% immunoreactivity). Hence, the bound antibody radiation AUC[CIAR(t)], was the key determinant of the therapeutic index (AUC[CIAR(t)]÷AUC[CIA(t)]). At low treatment doses (<370MBq [10mCi] or 0.2mg), AUC[CIAR(t)] was directly proportional to immunoreactivity (Figure 3A). However, as the dose increased, the AUC[CIAR(t)]-immunoreactivity curve bent downwards such that increases in immunoreactivity had diminishing benefits (Figure 3B). Over the 10–90% immunoreactivity range, AUC[CIAR(t)] and therapeutic index increased by 746–750% at 74MBq (2mCi), by 361% at 1295MBq (35mCi), and by 299% at 1850MBq (50mCi).

Fig. 3.

Predicted immunoreactivity effects on therapeutic index (and implicitly AUC[CIAR(t)]), relative to the current 69% immunoreactivity, for A) 74MBq (2mCi) and B) 1850MBq (50mCi) doses. Fixed-intercept linear regression is shown to illustrate concavity at high doses.

Considering the current 69% omburtamab immunoreactivity, the model predicted that further immunoreactivity improvements (to 100%) could increase the therapeutic index by 41.8%, 20.3%, and 17.5% for a 74MBq (2mCi), 1295MBq (35mCi), and 1850MBq (50mCi) dose respectively. These potential increases changed only slightly (17.5% became 20.9%) when antigen concentration was increased tenfold. This would imply that 69% immunoreactivity already achieved most of its benefits. Although additional increases could still have impact, especially for smaller 131I-omburtamab doses, the overall benefit was small.

Effects of Administered Activity (Dose) and Specific Activity, As Mediated by Metastasis Size and Antigen/Cell Density (R0)

In this model, changing the specific activity and changing the dose have the same effect on therapeutic endpoints; thus, only dose is mentioned.

While unbound “harmful” radiation AUC[CIA(t)] was approximately linear with increasing dose, AUC[CIAR(t)] tapered off (non-asymptotically) (Figure 4A). Because AUC[CIA(t)] always increased faster than AUC[CIAR(t)], therapeutic index was monotonically decreasing with respect to administered activity, maximized as dose approached 0. This would suggest that the therapeutic index alone was a poor metric of treatment performance, and must be used simultaneously with AUC[CIAR(t)] as done in prior literature [11, 12]. Their product notably had a peak, at 1495MBq (40.41mCi; Note: 1mg omburtamab dose=1850MBq) (Figure 4B). However, this peak was broad, i.e. any administered activity on 881MBq–2592MBq (23.82mCi–70.05mCi) had 95% of the maximum value, and any activity on 703MBq–3321MBq (19.01mCi–89.78mCi) had 90% of the maximum value.

Fig. 4.

Predicted effects of dose on therapeutic effectiveness, AUC[CIAR(t)], and collateral radiation, AUC[CIA(t)], (left vertical axis) and either A) therapeutic index (TI) or B) TI×AUC[CIAR(t)], relative to a reference point of a 1850MBq (50mCi) dose (right vertical axis). The figure uses R0=1.1937×1013 antigens/mL as this made AUC[CIAR(t)] and AUC[CIA(t)] fit concisely in one plot, but the trends are very similar regardless of R0. In Panel B, this changed the peak to 1508MBq (40.75mCi) from 1495MBq (40.41mCi).

The antigen concentration, R0, represented the product of metastasis size and the antigen/cell density (Supplemental Table 1). Previous pharmacokinetic modeling indicated that R0 influenced the relationship of therapeutic index to administered dose [11, 12]. For 131I-3F8, dose would only affect therapeutic index significantly if antigen concentration on tumor was high [11]. In contrast, for 131I-omburtamab, shapes of the AUC[CIAR(t)] and therapeutic index vs dose curves were largely independent of antigen concentration (Supplemental Figures 3–4). Antigen concentration did increase AUC[CIAR(t)] and therapeutic index, but the increase was the same across 131I-omburtamab doses and was essentially directly proportional to the increase in antigen concentration. Moreover, unbound “harmful” antibody AUC[CIA(t)], was not substantially affected by antigen concentration. Details of these relationships were detailed in the Supplemental Antigen Concentration Effects Validation.

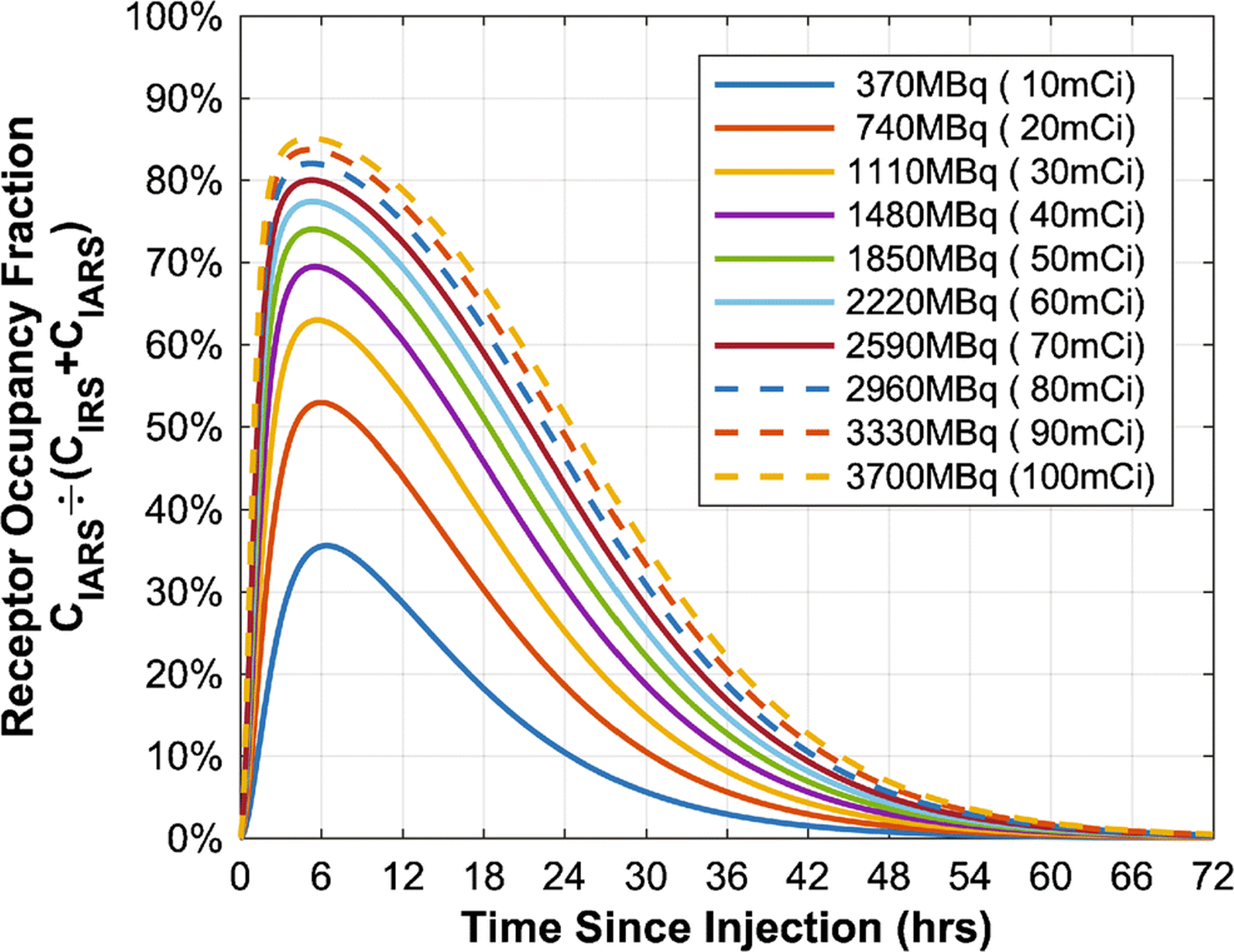

Effects of Dosage Timing (Dose Fractionation) and Assessment of Receptor Occupancy Fraction

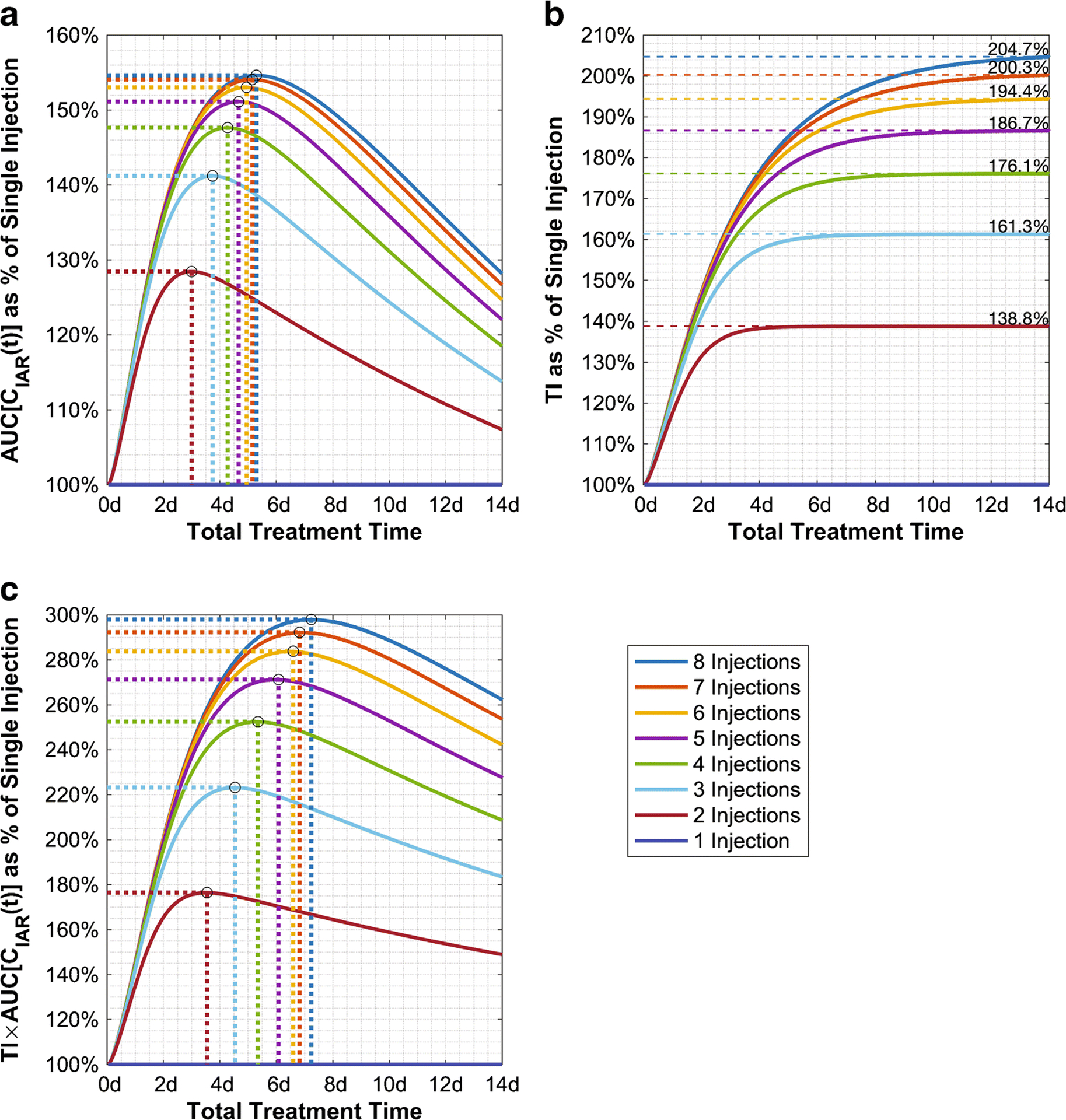

Splitting the 131I-omburtamab dose into fractions given at different times improved both therapeutic index and AUC[CIAR(t)] (Figure 5). For AUC[CIAR(t)], this improvement peaked at a treatment duration specific for each fractionation scheme (Figure 5A). With increasing fractionation, the optimal total treatment duration increased, but the optimal separation between injections decreased. In contrast, therapeutic index monotonically increased with total treatment duration until it plateaued after 4–13 days (Figure 5B). These effects are likely because the smaller per-injection dose from fractionation results in less receptor saturation at any one time (Figure 6, Supplemental Figure 6).

Fig. 5.

Predicted percentage improvement over single injection of A) therapeutic effectiveness, AUC[CIAR(t)], B) therapeutic index (TI), and C) TI×AUC[CIAR(t)] caused by various dose fractionation schemes with a constant total dose of 1850MBq (50mCi).

Fig. 6.

Predicted receptor saturation over time at different doses (R0 = 1.1937×1012 ant/mL). See Supplemental Figure 6 for further details.

Improvements from dose fractionation were significant. Four-way split of 1850MBq (50mCi) could simultaneously increase AUC[CIAR(t)] by 46% and therapeutic index by 73%. Previous modeling of intra-Ommaya 131I-3F8 arrived at similar conclusions [11]. However, while there was only a negligible effect on therapeutic index and AUC[CIAR(t)] after the interval between fractions was increased past 24hrs for two-fraction dosing of 131I-3F8 [11], the AUC[CIAR(t)] of 131I-omburtamab was predicted to maximize at a much longer interval of 72hrs (Table 1). Furthermore, an interval significantly (multiple days) longer precipitated a noticeable decrease in AUC[CIAR(t)] (Figure 5A). When the product of AUC[CIAR(t)] and therapeutic index was used for optimization, the interval of 85hrs was optimal for two-fraction dosing (Figure 5C). Fortunately, the (AUC[CIAR(t)] × therapeutic index) product peak was very broad, and the total duration time had to be extended far beyond the optimal point to see any significant compromise, regardless of the number of fractions.

TABLE 1.

Dose Fractionation Conditions That Maximized Therapeutic Metrics

| Injections* | Maximizing AUC[CIAR(t)] | Maximizing Product, AUC[CIAR(t)]×TI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Time (Days) | Spacing † (Hours) | AUC[CIAR(t)] (Relative) | Total Time (Days) | Spacing † (Hours) | TI ‡ (Relative) | Product § (Relative) | |

| 1 | N/A | N/A | 100.00% | N/A | N/A | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| 2 | 3.00 | 72.1 | 128.43% | 3.55 | 85.2 | 137.70% | 176.43% |

| 1.9–4.8 | 46.7–116 | ≥125.6% | 2.2–6.6 | 53.0–158 | 133–139% | ≥168.8% | |

| 3 | 3.75 | 45.0 | 141.19% | 4.54 | 54.5 | 159.32% | 223.16% |

| 2.4–5.8 | 29.0–70.2 | ≥137.1% | 2.9–7.9 | 34.3–94.2 | 151–161% | ≥210.8% | |

| 4 | 4.28 | 34.2 | 147.64% | 5.35 | 42.8 | 172.55% | 252.48% |

| 2.7–6.6 | 21.9–52.8 | ≥142.9% | 3.4–8.9 | 26.8–71.3 | 162–176% | ≥237.0% | |

| 5 | 4.67 | 28.0 | 151.11% | 6.08 | 36.4 | 181.40% | 271.37% |

| 3.0–7.2 | 17.8–43.0 | ≥146.0% | 3.7–9.8 | 22.5–58.8 | 170–186% | ≥254.3% | |

| 6 | 4.95 | 23.8 | 153.02% | 6.60 | 31.6 | 188.45% | 283.84% |

| 3.1–7.6 | 14.9–36.5 | ≥147.7% | 4.0–10.5 | 19.4–50.5 | 174–194% | ≥265.6% | |

| 7 | 5.15 | 20.6 | 154.07% | 6.83 | 27.3 | 193.38% | 292.24% |

| 3.2–7.9 | 12.8–31.7 | ≥148.7% | 4.3–11.1 | 17.1–40.6 | 178–199% | ≥273.2% | |

| 8 | 5.30 | 18.2 | 154.63% | 7.24 | 24.8 | 196.28% | 297.95% |

| 3.3–8.2 | 11.2–28.0 | ≥149.2% | 4.5–11.7 | 15.3–40.1 | 181–204% | ≥278.1% | |

The given ranges represent the bound of durations that still maintain at least 90% of the maximum benefit possible for that number of injections.

1850MBq (50mCi, 1mg) total dose, evenly distributed across each injection

Spacing is the time between consecutive injections while total time is time from the first to the last injection

TI represents therapeutic index, which monotonically increases with widening spacing.

The relative AUC[CIAR(t)] at these fractionation parameters can be calculated from dividing the product by TI.

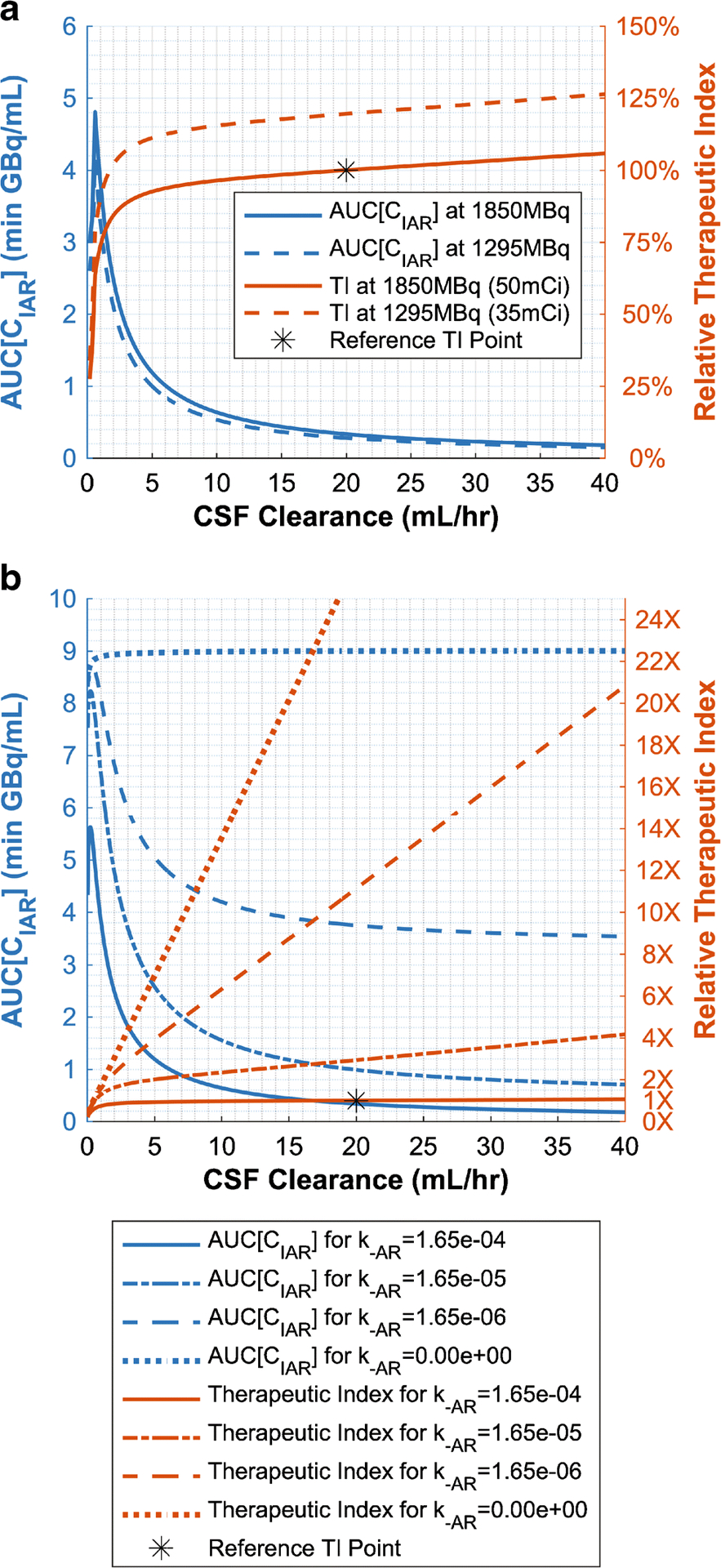

Effects of CSF Clearance (CL) and Affinity (KD)

CSF clearance (equal to CSF flow rate or alternatively CSF production) could vary among patients or be manipulated pharmacologically (see discussion). Interestingly, the 131I-omburtamab model predicted that high clearance could increase therapeutic index, albeit only slightly after CL>5mL/hr (Figure 7A). This was because while bound antibody, AUC[CIAR(t)], would decrease rapidly as clearance increased (because of less time for 131I-omburtamab binding to reach equilibrium), unbound antibody AUC[CIA(t)] decreased even faster. In other words, the loss of effectiveness from decreased antibody binding was offset by greater normal tissue sparing. However, since therapeutic index improved only slightly while the AUC[CIAR(t)] deteriorated markedly with faster clearance, decreasing the clearance could still be a worthwhile strategy. These trends were again similar to those found in the 3F8 one-compartment analysis [12]. For 131I-omburtamab, as CL was decreased from normal (20mL/hr) to 3mL/hr, AUC[CIAR(t)] increased 9.0%/(mL/hr) over the first 10mL/hr range and 26.6%/(mL/hr) over the last 2mL/hr range (comparable with 8.7%/(mL/hr) and 23.5%/(mL/hr), respectively, for 131I-3F8 [12]). In contrast, therapeutic index deteriorated much more slowly, at 0.68%/(mL/hr) over the 20mL/hr to 3mL/hr clearance range.

Fig. 7.

A) Predicted effect of clearance (equal to CSF production or CSF flow rate) on therapeutic effectiveness and therapeutic index (TI). B) Predicted clearance effects mediated by unbinding component, k−AR, of KD. TI values are relative to dose=1850MBq (50mCi), k−AR=1.65×10−4, and CL=20mL/hr. TI at k−AR=0 continues linearly outside of figure bounds.

Intuitively, AUC[CIAR(t)] should increase with slower clearance because 131I-omburtamab lasted longer in the CSF compartment, giving it more time to bind to tumor antigen. Hence, clearance effects were controlled by the dissociation equilibrium constant of the omburtamab-B7H3 antibody-receptor complex, (Figure 7B). Increasing the association rate constant (on rate), kAR, or decreasing the dissociation rate constant (off rate), k−AR, decreased the detrimental effect of clearance on AUC[CIAR(t)]. For irreversible binding (KD = 0), AUC[CIAR(t)] would not decrease with increasing clearance. In contrast, the CSF clearance effects on unbound antibody, AUC[CIA(t)], was unaffected by KD. See Supplemental Figure 7 for 3D visualizations of the clearance and activity relationship on therapeutic endpoints.

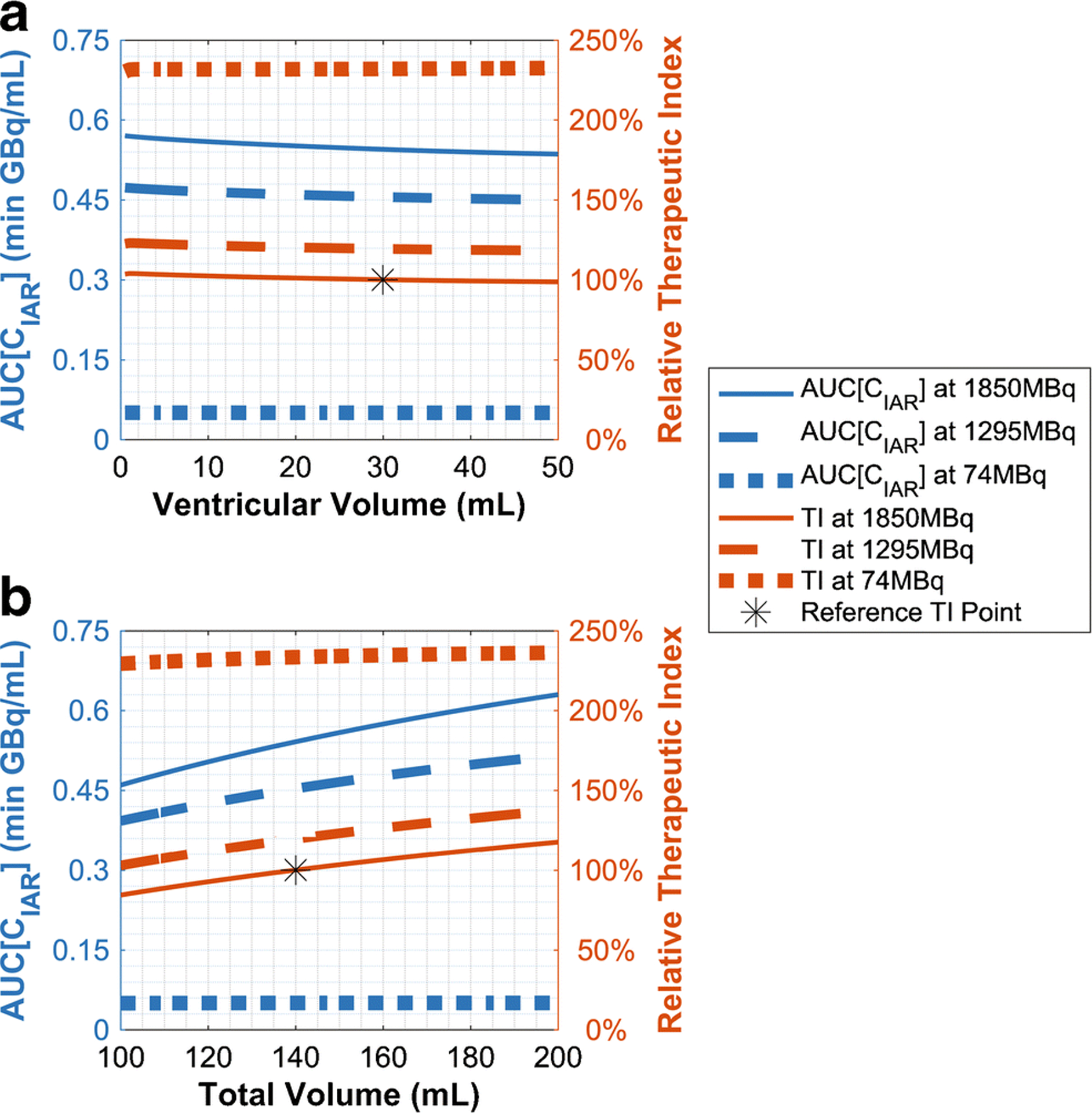

Effects of CSF Volume

As tumor cells were assumed to reside only in the subarachnoid space (Supplemental Default Parameter Values), ventricular volume alone ultimately had little effect on therapeutic metrics (Figure 8A). However, at higher doses, patients with enlarged subarachnoid volumes would have better pharmacokinetics. At a 1850MBq (50mCi) dose, an enlarged total CSF volume of 200mL (same proportional distribution between ventricles and subarachnoid space) had 16.3% greater AUC[CIAR(t)] and 17.6% greater therapeutic index than the standard 140mL CSF volume (Figure 8B). Thus, while larger volumes could dilute the antibody concentration, they also prolonged the transit time of 131I-omburtamab in the CSF since a fixed clearance rate would take longer to drain a larger volume of CSF. At low activities like 74MBq (2mCi), all these effects on therapeutic endpoints were negligible.

Fig. 8.

Predicted effect on therapeutic effectiveness and therapeutic index (TI) by A) ventricular volume (total volume fixed) and B) total volume (compartment volumes proportional). TI values are relative to 30mL ventricular volume, 140mL total volume, and 1850MBq (50mCi) dose.

Comparison Between 131I-omburtamab and 131I-3F8 Radioimmunotherapy AUC[CIA(t)] and Therapeutic Index

We compared AUC[CIAR(t)] and therapeutic index of 131I-omburtamab against previously reported 131I-3F8 values [11] (Supplemental Tables 2–3) across various antibody doses and antibody affinities. For comparison, the maximal antigen density was used for both systems: 500,000 B7-H3 antigen/cell and 10,000,000 GD2 antigen/cell [11, 12] (Tables 2–3). We studied doses and antibody affinity parameters that not only delivered a dose of 25Gy or greater, but also achieved a therapeutic index of 10 or greater, thereby minimizing toxicity. We found that 131I-omburtamab radioimmunotherapy could achieve this for a wider range of antibody affinities and doses than 131I-3F8 radioimmunotherapy could. Against a lower tumor B7-H3 antigen density of 200,000 antigens/cell (Supplemental Tables 4–5), 131I-3F8 was superior, especially at low antibody doses.

TABLE 2.

AUC[CIAR(t)] of 8H9 Assuming 500,000 Antigens/Cell

| Dose | AUC[CIAR(t)] in Gy for Dissociation Constant, KD (nM) of: | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | Mass | 10.0 | 8.0 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| 37MBq | 0.02mg | 4.6 | 5.7 | 7.4 | 10.6 | 18.3 | 28.1 | 31.5 | 35.7 | 41.2 | 48.8 | 53.7 |

| 74MBq | 0.04mg | 9.1 | 11.1 | 14.4 | 20.3 | 34.4 | 52.7 | 59.0 | 67.0 | 77.8 | 93.4 | 104.4 |

| 185MBq | 0.1mg | 21.2 | 25.7 | 32.6 | 44.8 | 72.4 | 106.5 | 118.1 | 133.1 | 153.6 | 185.4 | 211.6 |

| 370MBq | 0.2mg | 38.1 | 45.4 | 56.3 | 74.4 | 111.7 | 152.5 | 165.3 | 181.0 | 201.3 | 229.7 | 250.3 |

| 740MBq | 0.4mg | 63.6 | 73.8 | 88.2 | 110.4 | 150.9 | 189.4 | 200.5 | 213.7 | 230.0 | 251.6 | 266.5 |

| 1110MBq | 0.6mg | 81.9 | 93.4 | 109.0 | 132.0 | 171.5 | 206.7 | 216.6 | 228.2 | 242.2 | 260.5 | 272.8 |

| 1480MBq | 0.8mg | 96.0 | 108.0 | 124.0 | 147.0 | 184.9 | 217.6 | 226.7 | 237.1 | 249.7 | 265.8 | 276.5 |

| 1850MBq | 1.0mg | 107.3 | 119.5 | 135.6 | 158.3 | 194.7 | 225.4 | 233.8 | 243.4 | 254.9 | 269.5 | 278.9 |

TABLE 3.

Therapeutic Index of 8H9 Assuming 500,000 Antigens/Cell

| Dose | TI for Dissociation Constant, KD (nM), of: | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | Mass | 10.0 | 8.0 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| 37MBq | 0.02mg | 7.6 | 9.4 | 12.3 | 17.7 | 31.7 | 51.9 | 59.4 | 69.6 | 84.0 | 106.3 | 123.0 |

| 74MBq | 0.04mg | 7.4 | 9.2 | 11.9 | 17.0 | 29.7 | 48.0 | 54.9 | 64.2 | 77.7 | 99.8 | 117.7 |

| 185MBq | 0.1mg | 6.9 | 8.4 | 10.8 | 14.9 | 24.8 | 37.8 | 42.5 | 48.9 | 58.0 | 73.5 | 87.5 |

| 370MBq | 0.2mg | 6.2 | 7.5 | 9.3 | 12.3 | 18.9 | 26.3 | 28.7 | 31.8 | 35.9 | 41.8 | 46.3 |

| 740MBq | 0.4mg | 5.2 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 9.1 | 12.6 | 16.0 | 17.0 | 18.2 | 19.7 | 21.7 | 23.1 |

| 1110MBq | 0.6mg | 4.5 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 9.5 | 11.5 | 12.1 | 12.8 | 13.6 | 14.7 | 15.5 |

| 1480MBq | 0.8mg | 3.9 | 4.4 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 7.6 | 9.0 | 9.4 | 9.9 | 10.4 | 11.1 | 11.6 |

| 1850MBq | 1.0mg | 3.5 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 5.2 | 6.4 | 7.5 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 8.5 | 9.0 | 9.3 |

Data with TI<10 are light-gray. Otherwise, medium-gray, dark-gray, and black data indicate AUC[CIAR(t)]>25Gy, >50Gy, and >100Gy, respectively. The current value, KD = 8.94nM, is used for the analyses throughout this manuscript. See Supplemental Table 1–4 for more details.

DISCUSSION

Using patient CSF radioactivity measurements following 177 injections of 131I-omburtamab, the two-compartment model fit had a median R of 99.18%, supporting the proposed model and its optimization predictions. The model predicted several intuitively expected or known trends. For example, the model predicted that increasing the immunoreactivity, administered dose, or antigen concentration would increase anti-tumor dose (AUC[CIAR(t)]). The value of such pharmacokinetic models lies in its ability to yield quantitative information and predictions that are not intuitive, such as the relationship of therapeutic index (TI) by administered dose, immunoreactivity, and affinity. Likewise, while “harmful” radiation, AUC[CIA(t)], increased faster than AUC[CIAR(t)] as treatment dose was increased, the optimal dose range (when TI×AUC[CIAR(t)] was maximized) was very broad with respect to dose administered. This suggests that intra-Ommaya 131I-omburtamab did not fit in the class of drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI), which are riskier and more difficult to monitor clinically because dosages must be titrated precisely to prevent toxicity (e.g. warfarin) [17]. Instead, 131I-omburtamab radioimmunotherapy achieved near optimal benefit over a wide range of administered doses. Antigen density on tumor cells did have a significant (essentially proportional) effect on tumor dose and therapeutic index, and likely would play a key factor in the response variability among patients, especially because antigen density varied so greatly. Thus, measuring the B7-H3 antigen density of a patient’s tumor, while not necessary for titrating the treatment dose, could be highly informative as a predictive biomarker to determine patient eligibility for 131I-omburtamab radioimmunotherapy.

The 131I-omburtamab pharmacokinetic models have also provided non-intuitive predictions on the effect of dose schedule. Of the implementable treatment modifications we analyzed, the largest improvement in radioimmunotherapy effectiveness was dose fractionation. Just splitting administration into two injections resulted in up to 28% and 38% increases in AUC[CIAR(t)] and therapeutic index, respectively; further fractionation increased these metrics even further. Also surprising, dose splitting accomplished more than increasing immunoreactivity to 100% (which only improved AUC[CIAR(t)] and TI by a modest 17%). Factoring compliance, clinical feasibility, and decreasing marginal benefit with each additional fraction, a reasonable compromise would be four or five injections with about two-day separation (but at minimum one-day separation) between consecutive injections, which resulted in 46% AUC[CIAR(t)] and 73% TI improvements for four injections (43hrs apart) or 50% AUC[CIAR(t)] and 81% TI improvements for five injections (36hrs apart). There existed an optimal time interval between injections because AUC[CIAR(t)] improvements eventually dissipated with increased spacing. However, since therapeutic index monotonically approached a maximum with increased spacing, this implies that ensuring an adequately long interval between successive injections was more important than concerns of an excessively long interval between injections. Clinically, this could allow for additional flexibility in scheduling treatment injections.

CSF properties were also considered in optimizing 131I-omburtamab radioimmunotherapy. Specifically, CSF clearance, defined as the volumetric flow through the cerebrospinal cavity, could vary from patient to patient, because of age [18] and pathologic or physiologic brain conditions [19]. Reducing CSF production (and therefore CSF flow) could be achieved via medications (e.g. acetazolamide, furosemide) and has resulted in positive outcomes in treating several medical conditions including hydrocephalus [20], epilepsy [21], and mountain sickness [22]. It has also been used to decrease the risk of paraplegia complications from thoracoabdominal aortic surgery [23]. Thus, decreasing CSF flow pharmacologically had the potential for improving 131I-omburtamab radioimmunotherapy. Decreasing CSF clearance from 20mL/hr to 10mL/hr significantly increased antibody binding AUC[CIAR(t)] by 90%. Larger CSF volume (which could also vary across demographics [24] and certain brain conditions [25]) had a similar but considerably smaller effect on AUC[CIAR(t)]. Although therapeutic index deteriorated with decreasing clearance, the latter had an opposite and larger beneficial effect on AUC[CIAR(t)], somewhat supporting the potential of clearance reduction in improving radioimmunotherapy effectiveness. However, these clearance effects were less pronounced as KD decreased. Thus, other potential interventions (i.e. dose fractionation, affinity decrease) are more promising.

There are some limitations and subsequent potential future directions for this modeling. Our model only considered pharmacokinetics (distribution and binding) and not pharmacodynamics (including the mechanics of tumor growth/death). Models of cancer growth and death during radioimmunotherapy (not specifically to 131I-omburtamab or CSF-delivery) have suggested that rapid fractionation results in a higher likelihood of remission, but also a longer time to remission if it happens [26]. It would be fruitful to combine this modeling approach with ours to determine if those findings would apply here to intrathecally-delivered 131I-omburtamab. Additionally, our operationalization of harm is currently oversimplified pharmacokinetically; radiation deposited within fluid does not itself induce toxicity, but only the beta particles reaching adjacent tissues. Although endocytosis of omburtamab is minimal [3], isotope internalization, multicellular architecture of LM disease will influence tumor dosimetry. Incorporation of systemic circulation and specific tissue components (liver, kidneys, lungs, adipose) using 131I-omburtamab’s biodistribution data [10] could be an avenue to more rigorously consider damage, especially to certain vulnerable areas. Finally, our model primarily focuses on capturing the gross pharmacokinetics and uses the law of mass action; thus, it does not model all the cellular processes involved, such as antigen recycling, tumor growth kinetics, or tumor heterogeneity. This was necessary to reduce the complexity and number of variables of this model and because some of the processes (e.g. antigen recycling) have not been well-studied for 131I-omburtamab/B7-H3. While we do not expect these cellular details to change the results of this pharmacokinetic model (for antigen recycling, because 131I-omburtamab’s KD is only 9nM), further research to develop a comprehensive model to include these cellular processes for 131I-omburtamab radioimmunotherapy should be informative.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we have successfully applied a two-compartment pharmacokinetic model to intra-Ommaya 131I-omburtamab radioimmunotherapy. Between this 131I-omburtamab model and the 131I-3F8 model previously published [11], two-compartment models for intrathecal radioimmunotherapy have now been validated using tumor tissue sampling in a total of 86 patients and 202 injections, supporting the clinical observation that intra-Ommaya antibody conjugates could be an effective delivery of therapy to leptomeningeal cancer. This model also predicted that 131I-omburtamab had a wide window of optimal dose using the anti-tumor dose and therapeutic index as outcome metrics. While many parameters could affect these outcome metrics, the most effective approach was fractionation of 131I-omburtamab treatment into multiple administrations (4–5) with a minimum time interval (≥1day, goal: 2days) between injections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Anita Tsen-hui Louie of Vanderbilt University and Ronald Blasberg of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center for their critical review and revisions of the manuscript.

Funding:

This was supported in part by the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748, Enid A. Haupt Endowed Chair (NKC), and the Robert Steel Foundation (NKC).

Conflicts of interest/competing interest:

NKC reports receiving commercial research grants from Y-mabs Therapeutics and Abpro-Labs Inc.; holding ownership interest/equity in Y-Mabs Therapeutics Inc., holding ownership interest/equity in Abpro-Labs, and owning stock options in Eureka Therapeutics. NKC is the inventor and owner of issued patents licensed by MSK to Ymabs Therapeutics, Biotec Pharmacon, and Abpro-labs. Naxitamab and omburtamab were licensed by MSK to Y-mabs Therapeutics. Both MSK and NKC have financial interest in Y-mabs. NKC is an advisory board member for Abpro-Labs and Eureka Therapeutics.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Availability of data and material: Data reported in the manuscript will be shared under the terms of a Data Use Agreement and may only be used for approved proposals. Requests may be made to: crdatashare@mskcc.org.

Code availability: Data and computational parameters used in MATLAB are supplied as supplement to this manuscript.

Ethical approval: Prior to enrolling patients, the human subjects research described in this article was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and listed on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00089245). All patients taking part in the study or their legal guardian provided informed consent to participate in the clinical trial. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

REFERENCES

- 1.Larson SM, Carrasquillo JA, Cheung NK, Press OW. Radioimmunotherapy of human tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:347–60. doi: 10.1038/nrc3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung NK, Landmeier B, Neely J, Nelson AD, Abramowsky C, Ellery S, et al. Complete tumor ablation with iodine 131-radiolabeled disialoganglioside GD2-specific monoclonal antibody against human neuroblastoma xenografted in nude mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986;77:739–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Modak S, Kramer K, Gultekin SH, Guo HF, Cheung NK. Monoclonal antibody 8H9 targets a novel cell surface antigen expressed by a wide spectrum of human solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4048–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Modak S, Guo HF, Humm JL, Smith-Jones PM, Larson SM, Cheung NK. Radioimmunotargeting of human rhabdomyosarcoma using monoclonal antibody 8H9. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2005;20:534–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Souweidane MM, Kramer K, Pandit-Taskar N, Zhou Z, Haque S, Zanzonico P, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery for diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: a single-centre, dose-escalation, phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1040–50. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30322-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kramer K, Humm JL, Souweidane MM, Zanzonico PB, Dunkel IJ, Gerald WL, et al. Phase I study of targeted radioimmunotherapy for leptomeningeal cancers using intra-Ommaya 131-I-3F8. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5465–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer K, Pandit-Taskar N, Humm JL, Zanzonico PB, Haque S, Dunkel IJ, et al. A phase II study of radioimmunotherapy with intraventricular 131 I-3F8 for medulloblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer K, Kushner BH, Modak S, Pandit-Taskar N, Smith-Jones P, Zanzonico P, et al. Compartmental intrathecal radioimmunotherapy: results for treatment for metastatic CNS neuroblastoma. J Neurooncol. 2010;97:409–18. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0038-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer K, Pandit-Taskar N, Zanzonico P, Wolden SL, Humm JL, DeSelm C, et al. Low incidence of radionecrosis in children treated with conventional radiation therapy and intrathecal radioimmunotherapy. J Neurooncol. 2015;123:245–9. doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-1788-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandit-Taskar N, Zanzonico PB, Kramer K, Grkovski M, Fung EK, Shi W, et al. Biodistribution and Dosimetry of Intraventricularly Administered (124)I-Omburtamab in Patients with Metastatic Leptomeningeal Tumors. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:1794–801. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.219576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He P, Kramer K, Smith-Jones P, Zanzonico P, Humm J, Larson SM, et al. Two-compartment model of radioimmunotherapy delivered through cerebrospinal fluid. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:334–42. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1633-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lv Y, Cheung NK, Fu BM. A pharmacokinetic model for radioimmunotherapy delivered through cerebrospinal fluid for the treatment of leptomeningeal metastases. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1324–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed M, Cheng M, Zhao Q, Goldgur Y, Cheal SM, Guo HF, et al. Humanized Affinity-matured Monoclonal Antibody 8H9 Has Potent Antitumor Activity and Binds to FG Loop of Tumor Antigen B7-H3. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:30018–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.679852 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Picarda E, Ohaegbulam KC, Zang X. Molecular Pathways: Targeting B7-H3 (CD276) for Human Cancer Immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3425–31. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2428 [pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brassow F, Baumann K. Volume of brain ventricles in man determined by computer tomography. Neuroradiology. 1978;16:187–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costanzo LS. Physiology. Sixth edition. ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blix HS, Viktil KK, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Drugs with narrow therapeutic index as indicators in the risk management of hospitalised patients. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2010;8:50–5. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552010000100006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.May C, Kaye JA, Atack JR, Schapiro MB, Friedland RP, Rapoport SI. Cerebrospinal fluid production is reduced in healthy aging. Neurology. 1990;40:500–3. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.3_part_1.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silverberg GD, Heit G, Huhn S, Jaffe RA, Chang SD, Bronte-Stewart H, et al. The cerebrospinal fluid production rate is reduced in dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Neurology. 2001;57:1763–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrion E, Hertzog JH, Medlock MD, Hauser GJ, Dalton HJ. Use of acetazolamide to decrease cerebrospinal fluid production in chronically ventilated patients with ventriculopleural shunts. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:68–71. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiry A, Dogne JM, Supuran CT, Masereel B. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors as anticonvulsant agents. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7:855–64. doi: 10.2174/156802607780636726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leaf DE, Goldfarb DS. Mechanisms of action of acetazolamide in the prophylaxis and treatment of acute mountain sickness. Journal of applied physiology. 2007;102:1313–22. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01572.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jafarzadeh F, Field ML, Harrington DK, Kuduvalli M, Oo A, Kendall J, et al. Novel application of acetazolamide to reduce cerebrospinal fluid production in patients undergoing thoracoabdominal aortic surgery. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;18:21–6. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaye JA, DeCarli C, Luxenberg JS, Rapoport SI. The significance of age-related enlargement of the cerebral ventricles in healthy men and women measured by quantitative computed X-ray tomography. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:225–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ott BR, Cohen RA, Gongvatana A, Okonkwo OC, Johanson CE, Stopa EG, et al. Brain ventricular volume and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:647–57 doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Donoghue JA, Sgouros G, Divgi CR, Humm JL. Single-dose versus fractionated radioimmunotherapy: model comparisons for uniform tumor dosimetry. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:538–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.