Abstract

Introduction:

Phytosterols are implicated in the development of parenteral nutrition–associated liver disease. A newly proposed mechanism for phytosterol-mediated parenteral nutrition–associated liver disease is through phytosterol-facilitated hepatic proinflammatory cytokine release following exposure to intestinally derived bacteria. Whether the proinflammatory effects are liver cell specific is not known.

Aim:

To determine if phytosterols cause inflammation in hepatocytes or Kupffer cells independently or require costimulation by lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

Methods:

In an in vivo study, neonatal piglets on parenteral nutrition for 11 days received an 8-hour infusion of LPS. In the in vitro studies, neonatal piglet Kupffer cells and hepatocytes were treated with media, media + 1% soy oil, or media + 1% soy oil + 100μM phytosterols. After 24-hour incubation, cells were treated with farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist obeticholic acid or liver X receptor (LXR) agonist GW3965 and challenged with LPS or interleukin 1β.

Results:

LPS administration in piglets led to transient increases in proinflammatory cytokines and suppression of the transporters bile salt export pump and ATP-binding cassette transporter G5. In hepatocytes, phytosterols did not activate inflammation. Phytosterol treatment alone did not activate inflammation in Kupffer cells but, combined with LPS, synergistically increased interleukin 1β production. FXR and LXR agonists increased transporter expression in hepatocytes. GW3965 suppressed proinflammatory cytokine production in Kupffer cells, but obeticholic acid did not.

Conclusions:

LPS suppresses transporters that control bile acid and phytosterol clearance. Phytosterols alone do not cause inflammatory response. However, with costimulation by LPS, phytosterols synergistically maximize the inflammatory response in Kupffer cells.

Keywords: soybean oil, phytosterols, Kupffer cells, inflammation, hepatocyte, bile salt export pump, ATP-binding cassette transporter G5, parenteral nutrition–associated liver disease

Introduction

Infants who cannot tolerate enteral feeds require parenteral nutrition (PN) to support nutrient and growth needs. For the past 40 years, the primary lipid source for PN in infants has been soy oil (SO) based. Short-term use of SO in infants is safe and effective. However, prolonged use of SO can lead to elevated concentrations of serum and hepatic bile acids, hepatic steatosis, and high serum conjugated bilirubin, which together constitute PN-associated liver disease (PNALD). The use of new-generation fish oil (FO)–based lipid emulsions can resolve SO-mediated PNALD in infants.1 FO and SO lipid emulsion compositions vary considerably in fatty acid profiles and bioactive constituents. SO contains phytosterols, which accumulate during PN and have been correlated with the severity of PNALD.2 FO does not contain phytosterols, but in mice, the addition of phytosterols to FO can cause PNALD.3

Serum phytosterol levels in healthy infants are typically <100 μmol/L but in PN can increase to >1000 μmol/L over time.2,4 At low levels, phytosterols do not appear to be harmful, as infants in the early period of PN do not display signs of liver injury. Likely, a progressive increase in phytosterols is required for PNALD to manifest. The heterodimeric transporters ATP-binding cassette transporter G5/8 (ABCG5/8) clear phytosterols from the hepatocyte into the bile duct and from the enterocyte into the lumen of the intestine.5 There has not been much research on how the expression of these key genes is affected by PN or by accumulation of phytosterols themselves. In piglets, expression of hepatic ABCG5/8 is unchanged between enterally fed piglets and those receiving SO-based or FO-based emulsions.6 In mice, there is evidence to suggest that ABCG5/8 expression increases with FO administration, but expression is similar in enterally fed mice or mice receiving SO or FO supplemented with phytosterols.3

The mechanisms of phytosterol-mediated PNALD are not clearly understood. SO contains a mixture of phytosterols, with the most abundant being β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, and campesterol. Stigmasterol can antagonize the nuclear hormone receptor farnesoid X receptor (FXR), a key regulator in bile acid homeostasis, which could lead to impaired bile acid clearance and cholestasis through suppression of the bile salt export pump (BSEP).7 Stigmasterol may also promote an exaggerated inflammatory response in resident hepatic macrophages (Kupffer cells) that have already been activated by exposure to other inflammatory mediators, such as gram-negative bacteria from bacterial translocation or sepsis.3 Inflammation can lead to hepatic dysregulation of bile acid homeostasis through suppression of BSEP directly.8 However, whether phytosterols can cause inflammation directly in the hepatocyte to cause suppression of BSEP has thus far been unexplored.

The primary aim of our study is to determine if phytosterols directly cause hepatic inflammation or facilitate inflammation through lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in a cell-specific manner. Two nuclear hormone receptors—FXR and liver X receptor (LXR)—are involved in the regulation of bile acid and phytosterol clearance, respectively. Both FXR and LXR also display anti-inflammatory properties, which could prove highly relevant in the context of phytosterol-mediated inflammation in the liver. The second aim of this study is to examine agonists for FXR and LXR to see if they can rescue phytosterol-mediated inflammation and the inflammation-mediated suppression of BSEP and ATP-binding cassette transporter G5 (ABCG5).

Methods

Animal Care and Surgical Procedures

All neonatal piglet study procedures were done in accordance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” under the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Baylor College of Medicine. Pregnant sows (domestic pigs, species Sus scrofa, from mixed breeds Duroc, Hampshire, Yorkshire, and Landrace) were obtained from either the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (Huntsville, TX) or a commercial swine farm and housed within the Children’s Nutrition Research Center. Piglets were delivered via caesarian section at gestational day 108. Surgical procedures have been described in detail.9 Piglets were implanted with a jugular catheter for the administration of total PN (TPN) with a similar nutrient administration previously described, and they received a lipid dose of SO at 10 g·kg−1 ·d−1.10 On the day of delivery, piglets received 50% of their calculated nutrient needs, which was gradually increased to 100% (10 mL·kg−1·h−1) within 7 days and maintained until the end of the 11-day study.

On day 11, piglets received an 8-hour infusion of either saline (control) or LPS (10 μg·kg−1·h−1, Escherichia coli 0111:B4; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) that had been added to the lipid infused. Blood was collected every hour for serum and plasma samples, which were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for later analysis. At the end of the 8-hour infusion, pigs were euthanized (Beuthanasia; Schering-Plough, Kenilworth, NJ), with tissues collected and stored in the same manner as serum and plasma samples.

Primary Hepatocyte and Kupffer Cell Isolation

From a separate group of piglets, cells were isolated from term-born piglets (2–6 days old) from the same commercial farm described in our in vivo study. Following the liver perfusion as described previously, hepatocytes and Kupffer cells were isolated according to a modified method by Liu etal.11 Briefly, the initial/raw Kupffer cell fraction was suspended in 17.6% Optiprep solution (Sigma-Aldrich). Layered on top of the cells was an 8.2% Optiprep solution, followed by Dulbecco’s PBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 0.1 % bovine serum albumin. Cells were spun at 1400 × g for 17 minutes with the brake turned off. Cells at the interphase of the 17.6% and 8.2% gradient were collected, washed twice in Dulbecco’s PBS, and then plated on untreated plastic sterile plates for Kupffer cell adhesion. Unattached cells were washed off, and Kupffer cells were replated for experiments. For each piglet, cells were treated in triplicate for technical replicates. Each piglet’s cells were treated on separate days, with a final number of 4 total piglets used for each treatment.

Cell Culture Study Design

Isolated cells were switched to serum-free media for 24 hours before treatments. Hepatocytes were treated with either serum-free William’s E media alone (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) or media supplemented with 1% SO (v/v; 1 mL per 100 mL of media; final phytosterol concentration, approximately 10 μM; Intralipid) for 24 hours. For some treatments, an additional phytosterol mixture of 67.4% β-sitosterol, 16.9% campesterol, and 15.6% stigmasterol (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared, as described previously, and dissolved in ethanol to a concentration of 50 mM.12 The cells were treated with 0.2% of the phytosterol/ethanol solution to a final added concentration of 100 μM. This concentration of phytosterol is within the low end of observed plasma concentrations of infants with PNALD.2 Following the 24-hour incubation, cells were treated for 24 hours with FXR agonist obeticholic acid (OCA; 1 μM; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) or LXR-agonist GW3965 (2 μM; Sigma-Aldrich), without and with addition of LPS (50 ng/mL) or interleukin 1β (IL-1β; 10 ng/mL). The selected concentrations for OCA and GW3965 have been determined in the literature to be within a nontoxic range that maximally induces target gene transcription.13 Kupffer cells were treated similarly in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) serum-free media. Media and cells were collected separately at the end of the treatment period.

Histology

Hepatocytes and Kupffer cells were plated on either glass cover slips or Nunc Lab-Tek II Chamber Slide System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were incubated in media alone or media supplemented with 1% SO for 24 hours. Cells were then stained with oil red O and Mayer’s hematoxylin.

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA was isolated from tissues and cell culture with Trizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific) per the manufacturer’s protocol. The quantity of RNA was determined with a NanoDrop nd-1000 (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE). Synthesis of cDNA was performed with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Determination of gene expression was done with previously used primers designed for Sybr Green amplification technology with PowerUP Sybr Green Master Mix (Applied Biosciences) on a Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).6,12,14 Fold change of samples was calculated with the ΔΔ-CT method with β-actin used as the normalizing gene.

Phytosterol Uptake

Cellular phytosterol uptake was performed as previously described by Brauner et al with modification.15 Media were prepared with 50μM phytosterol spiked with [22,23-3H β-sitosterol] (3H-β-sitosterol; American Radio-labeled Chemical Inc, St Louis, MO) to a specific activity of 3 μCi/μmol. The experiments consisted of 2 separate phytosterol preparations. First, stigmasterol acetate (Sigma Aldrich) was dissolved in ethanol and incorporated into TransIT transfection reagent (Mirus Bio LLC, Madison, WI) as described by El Kasmi etal.3 The second media preparation was a mixture of β-sitosterol, campesterol, and stigmasterol to ratios found in soy-based lipid emulsions, which was dissolved in ethanol and then incorporated in SO as described previously.12 This phytosterol-supplemented SO was added to the media at 1% v/v. The cells were treated with the 3H-β-sitosterol for 24 hours; then, cells and media were collected for determination of phytosterol incorporation. Cellular uptake of 3H-β-sitosterol was assessed with a scintillation counter (LS6500; Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL).

Serum and Cell Culture Cytokine Analysis

For Kupffer cells, cells were plated in a 96-well format and treated as outlined in the experimental study section for 24 hours. Then, 50 μL of media was collected and used for cytokine concentration with commercially available ELISA kits for porcine IL-1β and IL-6 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Plasma samples collected from TPN-fed pigs were assayed with an electrochemiluminescence multiplex detection system (Sector Imager 2400 and Discovery Workbench Software; both from Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD) that had been validated for porcine cytokines by comparisons with traditional ELISA.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with SigmaPlot software (Systat Software Inc, Chicago, IL). For data that utilized multiple sampling time points of piglets, 2-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed. For control samples in the cytokine array that were below the limit of detection, the following formula was used: limit of detection / √2.16 For gene expression analysis in piglets, a 1-sided t test was used. For cell culture experiments with multiple treatment groups, 2-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis was done for normalized data. The ANOVA on ranks with Dunn’s post hoc analysis was used for nonnormalized data. P values <.05 were considered significant. Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

Piglet In Vivo Study

Cytokine response to LPS infusion.

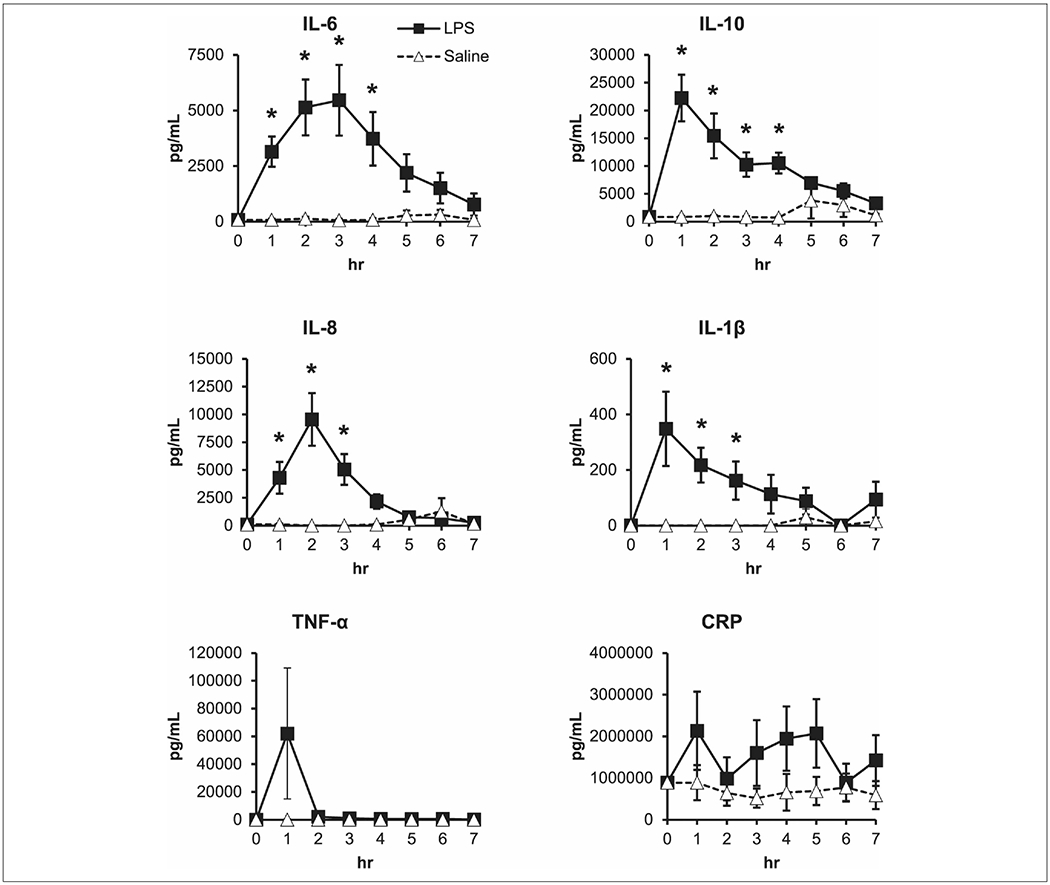

LPS-treated pigs showed significant transient increases from 0 to 1 hour in plasma proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor α and anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (Figure 1). Although cytokine profiles varied in their peak response time, all trended toward a decrease in concentration by the end of the infusion period. Saline-treated piglets had very low to undetectable concentrations of circulating cytokines.

Figure 1.

Short-term lipopolysaccharide (LPS) administration transiently increases proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in preterm pigs. Piglets were administered saline or 80 μg of LPS at a rate of 10 μg·h−1 for 8 hours, and blood samples were taken each hour. Each point is an individual piglet’s measured value. n = 8 pigs per group. Two-way repeated measures analysis of variance. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 vs saline. CRP, c-reactive protein; IL, interleukin; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α.

BSEP and ABCG5 expression from LPS infusion.

Target genes in the liver that regulate transport of bile acids and sterols similarly responded to LPS vs saline treatment. LPS decreased BSEP (Figure 2A) to 0.27-fold (P < .05) of saline-treated piglets and 0.37-fold (P < .05) in sterol efflux transporter ABCG5 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) administration suppressed bile acid and phytosterol transporter expression. Hepatic gene expression measured by real-time polymerase chain reaction for (A) bile salt export pump (BSEP) and (B) ATP-binding cassette transporter G5 (ABCG5). n = 3–8 pigs per group. One-sided t test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 vs saline.

Liver Cell In Vitro Study

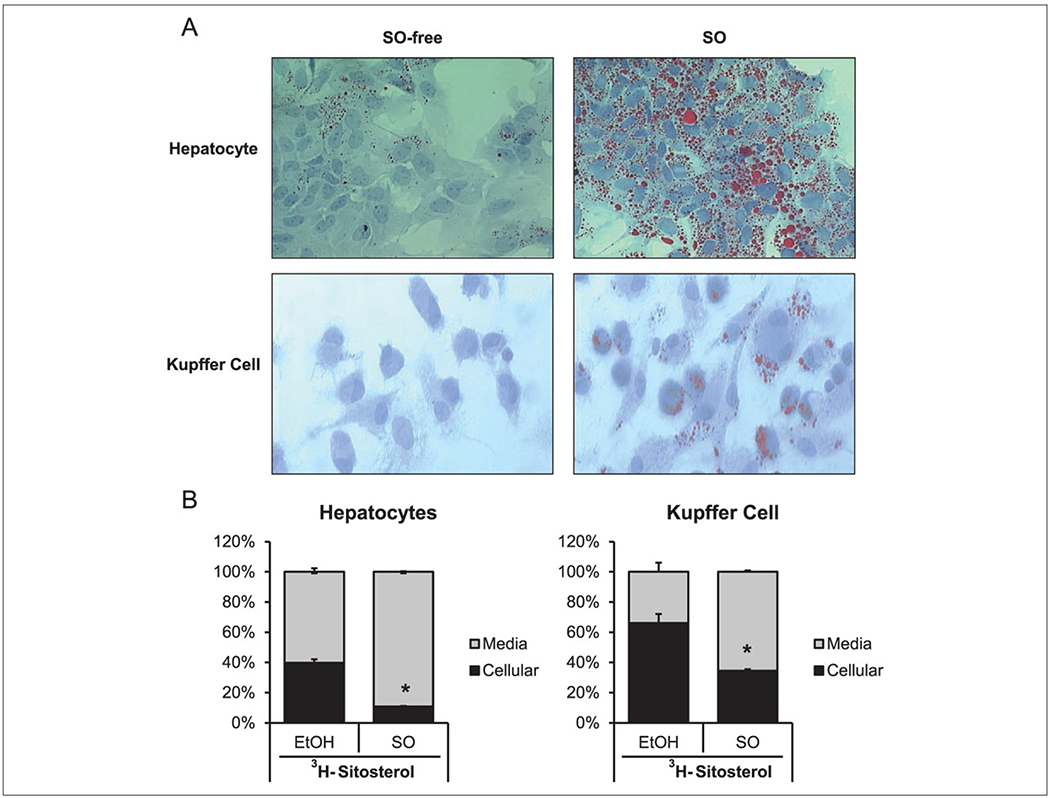

Hepatocyte and Kupffer cell uptake of 1% SO and 3H-β-sitosterol.

SO-free media had little accumulation of lipid, as evidenced by red staining from oil red O (Figure 3A). There was a marked increase in stained lipid in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells when incubated in SO-containing media. At 48 hours, the lipid accumulation from 1% SO did not increase cell death as assessed by MTT assay (data not shown). In SO-free media, hepatocyte uptake of 3H-β-sitosterol was 39.7% of the total labeled dose added to the media. In SO-supplemented media, hepatocyte uptake of 3H-β-sitosterol was limited to 10% (P < .05) of the total labeled dose added to the media. In contrast, Kupffer cells had greater uptake in general as compared with hepatocytes. In SO-free media, hepatocyte uptake of 3H-β-sitosterol was 66% of the total labeled dose. Kupffer cells incubated with media containing 1% SO accumulated 34.5% of labeled 3H-β-sitosterol, which was significantly lower (P < .05) than the SO-free group.

Figure 3.

Hepatocytes and Kupffer cells accumulated lipid and phytosterols when incubated with media supplemented with 1% soy oil (SO). (A) Representative images of lipid accumulation in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells show oil red O staining of cells incubated with 1% Intralipid for 24 hours. (B) Hepatocytes and Kupffer cells incubated with media containing [22,23-3H] β-sitosterol in either 50μM stigmasterol acetate in ethanol (EtOH) or 1% Intralipid for 24 hours. n = 3 independent experiments. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 vs EtOH.

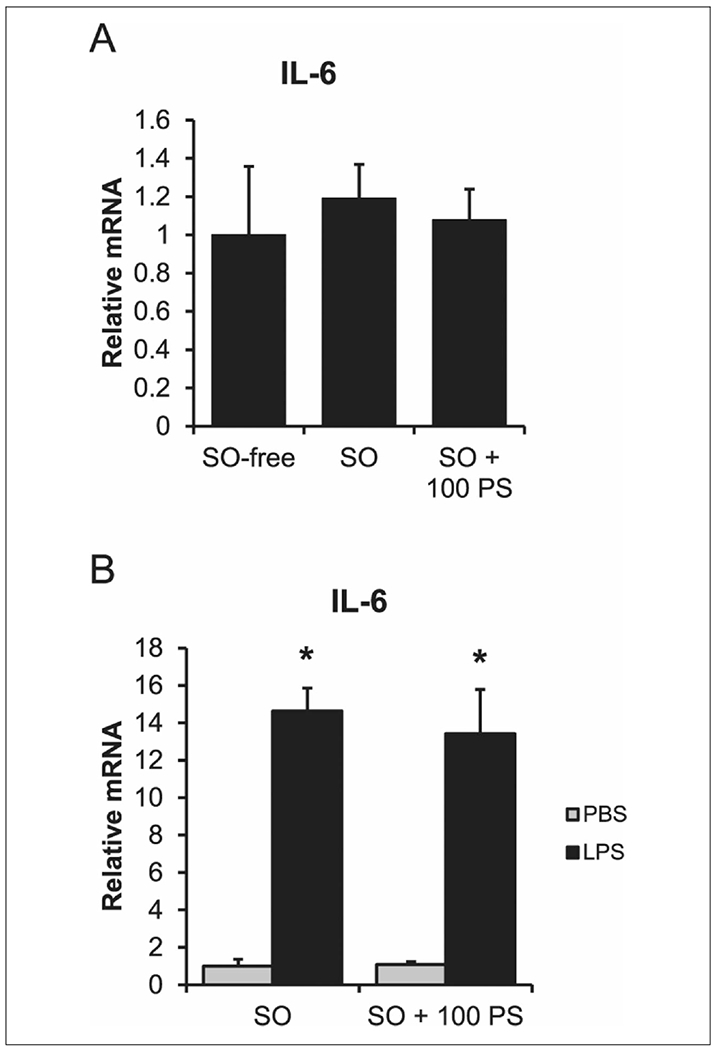

Hepatocyte cytokine response to phytosterols.

The addition of SO to the media did not change the expression of IL-6 (Figure 4A) in hepatocytes. When 100μM phytosterol was added to the SO-supplemented media, there was still no change in IL-6 expression in hepatocytes. The cells still had a capacity to functionally respond to inflammation, though, as administration of LPS led to a significant increase (P < .05) in gene expression of IL-6 (Figure 4B). The combined treatment of SO + 100μM phytosterols with LPS did not change the cytokine gene expression when compared with LPS alone.

Figure 4.

Phytosterols do not cause an inflammatory response in hepatocytes. (A) Hepatocytes treated in media alone (SO-free), media containing 1% SO (v/v) (SO), or media containing SO and 100μM PS (SO + 100 PS). (B) PBS or 50 ng/mL of LPS-treated cells in either SO-free or SO + 100 PS media for 24 hours. n = 4 piglets (hepatocytes). One-way analysis of variance. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 vs untreated. IL, interleukin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PS, phytosterol.

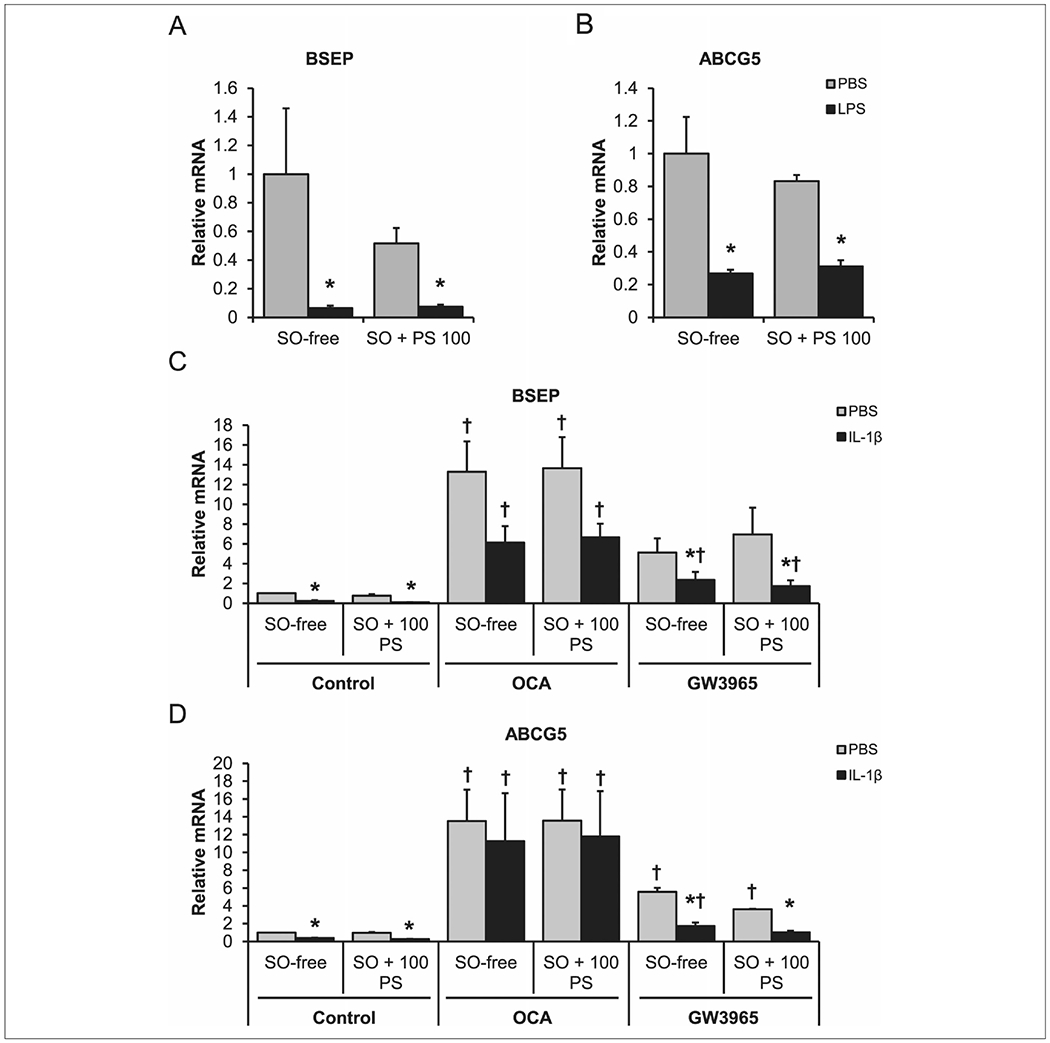

FXR and LXR agonist treatment of hepatocytes.

LPS treatment in SO-free and SO-supplemented media suppressed (P < .05) transporter expression of BSEP (Figure 5A) and ABCG5 (Figure 5B) to less than half the expression level of cells not treated with LPS. IL-1β treatment recapitulated the results from LPS treatment with suppression (P < .05) of BSEP (Figure 5C) and ABCG5 (Figure 5D). GW3965 treatment did increase expression of ABCG5 (P < .05; Figure 5D) and, when combined with IL-1β, was able to restore ABCG5 expression to its basal level. BSEP and ABCG5 expression increased (P < .05) in response to OCA treatment (Figure 5C, 5D). The magnitude of increase was particularly large (10-fold BSEP, 11-fold ABCG5). The addition of IL-1β to OCA-treated cells led to slightly lower expression in BSEP relative to treatment with OCA alone. Similarly, ABCG5 expression (Figure 5D) significantly increased when compared with the cells treated with IL-1β (P < .05).

Figure 5.

Obeticholic and GW3965 can rescue inflammation-mediated suppression of hepatocyte efflux transporters. Hepatocytes incubated in media only (SO-free) or media supplemented with 1% SO and 100μM PS (SO + 100 PS) for 24 hours. Cells were treated with either PBS or LPS (50 ng/mL) for an additional 24 hours: (A) BSEP and (B) ABCG5. Additional cells were treated with SO-free or SO + 100 PS media for 24 hours, then treated with control, 1μM OCA, or 2μM GW3965 in the presence of either PBS or 10 ng/mL of IL-1β for an additional 24 hours: (C) BSEP gene expression and (D) ABCG5 gene expression. n = 4 piglets hepatocytes. Two-way analysis of variance. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 vs PBS. †P < .05 vs control. ABCG5, ATP-binding cassette transporter; BSEP, bile salt export pump; IL, interleukin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; OCA, obeticholic acid; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; PS, phytosterol; SO, soy oil.

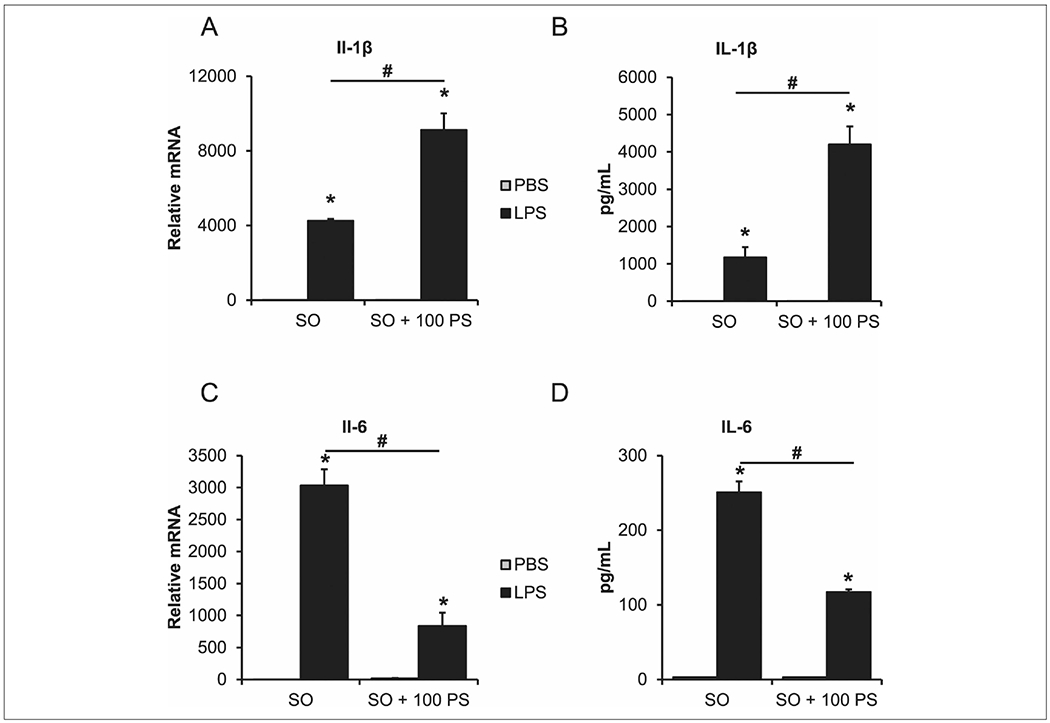

Kupffer cell cytokine expression from coadministration of phytosterol and LPS.

The administration of LPS led to a robust (P < .05) increase in the concentration of IL-1β (Figure 6B) and IL-6 (Figure 6D) protein in the media of treated cells. Phytosterols alone did not lead to a detectable increase in either cytokine. When LPS and phytosterols were administered in combination, the IL-1β (Figure 6B) concentration more than doubled (P < .05) when compared with LPS alone. However, the IL-6 (Figure 6D) concentration decreased by half (P < .05) with the combined treatments.

Figure 6.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and phytosterols have a synergistic effect on Kupffer cells’ inflammatory response. Cells were treated with media supplemented with 1% SO (SO) or media supplemented with 1% SO and 100μM PS (SO + 100 PS) with either PBS or 50 ng/mL of LPS for 24 hours: (A) IL-1β transcript expression, (B) IL-1β protein concentration in collected media, (C) IL-6 transcript expression, (D) IL-6 protein concentration in collected media. n = 4 piglets (Kupffer cells). Two-way analysis of variance. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 vs PBS. #P < .05 vs SO. IL, interleukin; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; PS, phytosterol; SO, soy oil.

FXR and LXR agonist treatment of Kupffer cells.

OCA increased (P < .05) the expression of IL-1β (Figure 7A) protein in the media of treated cells when combined with LPS (vs control) and LPS + phytosterols (vs LPS alone). The IL-6 response to the combination of OCA and LPS displayed a similar increase (P < .05); however, the increase was not as large as IL-1β. The addition of phytosterols to the OCA and LPS treatment led to a decrease in IL-6 protein concentration similar to results seen in Figure 6B. GW3965 suppressed (P < .05) the LPS-mediated increase in IL-1β (Figure 7A) and IL-6 (Figure 7B). The coadministration of phytosterol and LPS did lead to an increase (P < .05) in IL-1β protein concentration that was not completely suppressed by the administration of GW3965 (Figure 7A). IL-6 protein concentration decreased when phytosterols were added to LPS and GW3965 treatments (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Obeticholic acid and GW3965 suppression of the synergistic effect of LPS and phytosterols on Kupffer cell inflammatory response. Cells were incubated in media supplemented with 1% SO (SO) or media supplemented with 1% SO and 100μM PS (SO + 100 PS) for 24 hours. Cells were then treated with control, 1μM OCA, or 2μM GW3965 in the presence of either PBS or 50 ng/mL of LPS for an additional 24 hours. Protein concentration in collected media of cells: (A) IL-1β and (B) IL-6. n = 4 piglets (Kupffer cells). Two-way analysis of variance. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < .05 vs PBS. †P < .05 vs control. #P < .05 vs SO. IL, interleukin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; OCA, obeticholic acid; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; PS, phytosterol; SO, soy oil.

Discussion

We have shown that LPS transiently increases multiple cytokines in piglets receiving TPN, which can lead to suppression of bile acid and phytosterol transporters in the liver. We further characterized the effect of phytosterols and LPS in 2 of the main cells types in the liver to better understand phytosterol-mediated development of PNALD through cytokine and transporter regulation. We showed that phytosterols exert cell-specific effects, with the capacity to synergistically enhance LPS-mediated cytokine induction in Kupffer cells but not hepatocytes. LPS and the cytokine IL-1β, but not phytosterols, suppressed hepatocyte expression of bile acid and phytosterol transporters BSEP and ABCG5, respectively. Both FXR and LXR agonists restored BSEP and ABCG5 gene expression to basal levels following their cytokine-mediated suppression in hepatocytes. However, the LXR agonist, but not FXR agonist, was effective in suppressing LPS and phytosterol-mediated cytokine expression in Kupffer cells.

Infants receiving prolonged TPN, especially those with complications due to intestinal failure, have elevated bacterial translocation and activation of the inflammatory cascade through Toll-like receptor 4 signaling.17 The activation of hepatic inflammation through Toll-like receptor 4 could lead to liver injury in PNALD similar to that described for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.18 Piglets receiving TPN for approximately 2 weeks have elevated serum phytosterol concentrations.6 Eight-hour administration of LPS to piglets that were receiving TPN for 11 days led to an early but transient spike in serum cytokine levels. The adaptive response to endotoxin to prevent continuous elevation of cytokines is functional even when the piglets are receiving, with elevated serum phytosterols, a constant infusion of LPS. This endotoxin resistance is consistent with other reports across multiple species.19 The administration of LPS led to suppression of hepatic bile acid and phytosterol transporters BSEP and ABCG5, confirming results seen in mouse models.20 The suppression of these FXR target genes is consistent with clinically observed elevations in serum and liver concentrations of bile acids and phytosterols during long-term TPN-fed in infants with PNALD.4,21

Normal uptake of dietary phytosterols is through esterification and incorporation into chylomicrons.22 In TPN, the phytosterols are bound in micelles formed by the lipid emulsion and are presumably absorbed directly by the liver. However, some phytosterol is incorporated into low-density lipoproteins.23 It is not clear if much exchange with lipoproteins takes place during TPN and, therefore, which method is the most direct route for uptake into the liver. In our cell culture model, the uptake of endogenous 3H-sitosterol provides evidence that hepatocytes can directly take up the phytosterols. The hepatocytes and Kupffer cells take up phytosterols when they are mixed with lipid (in 1% SO) or added separately as free phytosterols.

The hepatocyte response to LPS led to increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines, yet phytosterols did not cause a similar response. This is interesting given that with Kupffer cells, we observed an increase in cytokine levels in the media when LPS and phytosterols were coadministered. Phytosterols do not directly induce an inflammatory response, since administration of phytosterols alone did not increase cytokine levels. Cytokine expression is regulated though positive effects, such as NF-κB binding to promoter regions of cytokine genes, and through negative effects, such as inhibition of further signaling through SOCS3 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 3) binding to NF-κB promoter regions of cytokine genes. Given that we do not see an increase in cytokine expression with phytosterol treatment alone, we hypothesize that phytosterols may work to suppress negative feedback regulation of cytokine expression, rather than directly promote cytokine expression. Hepatocyte and Kupffer cell negative feedback regulation of cytokine signaling differs by the predominant negative feedback regulators in the cell types. Hepatocytes have high expression of SOCS3 but very low expression of RelB.24 RelB is another transcription factor that inhibits NF-κB binding to the promoter of proinflammatory genes, and its degradation can lead to an exaggerated cytokine release in macrophages.25 The lack of this RelB protein or other inflammatory mediators in the hepatocyte may account for the differential effects in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells. Further studies are needed to delineate proinflammatory pathways in both cell types to confirm this potential mechanism.

Phytosterols did not directly suppress the hepatocyte expression of BSEP in our study. This results contrasts with other work that has shown phytosterols to directly suppress BSEP.6,7 The cells were treated for 24 hours in the prior studies and 48 hours in our current experiment. Hepatocytes in culture begin to rapidly de-differentiate when plated in a monolayer.26 We cannot exclude the possibility that the extended course of treatment for our cell culture may have altered hepatocyte gene response to mask smaller effects by phytosterols. As there is no observable difference in the cells treated with or without SO on BSEP expression, we do not think that lipid directly affected the cells’ capacity to respond to phytosterol treatment; however, there were minor effects on cell viability with SO that cannot be completely excluded from consideration. BSEP and ABCG5 were suppressed by LPS in our in vivo and in vitro experiments. The administration of IL-1β also decreased the expression of these transport genes. The large increase in IL-1β from the coadministration of LPS and phytosterols in the Kupffer cells suggests that phytosterols in TPN could exacerbate the development of cholestasis and phytosterol accumulation through paracrine cytokine secretion from Kupffer cells to nearby hepatocytes. Rescue of cytokine-suppressed transporters by FXR and LXR agonists in the hepatocyte was effective. The FXR agonist OCA had a robust response when exposed to hepatocytes. The use of CDCA (chenodeoxycholic acid), an endogenous bile acid ligand for FXR, prevents PNALD development in TPN-fed piglets.27 Moreover, studies in primary human hepatocytes show that CDCA upregulates ABCG5 expression.28 Therefore, our current finding of the strong effect of OCA, a more potent FXR agonist, on BSEP and ABCG5 upregulation is in agreement with other findings of FXR-mediated regulation of hepatocyte bile acid and phytosterol transporters.29,30

In contrast to our finding in hepatocytes, OCA treatment did not effectively suppress the cytokine response in Kupffer cells but instead exacerbated the response. Vavassori et al showed that LPS-mediated inflammation in mouse splenic macrophages can be suppressed by administration of OCA.10 We have also observed the same cytokine-suppressive effect of OCA in hepatocytes that are treated with regular media (data not shown). Our study does differ as we treat cells in the presence of 1% SO in combination with the nuclear receptor agonist. The Kupffer cells do uptake the lipid, and this may cause an increased cholesterol synthesis 31 FXR is also a key regulator in activating cholesterol synthesis.32 Increased cholesterol biosynthesis in the macrophage via FXR could contribute to additional inflammation that is exacerbated in the presence of LPS and phytosterols.33 However, we did not measure expression of genes associated with cholesterol biosynthesis in the Kupffer cells to determine if OCA led to an increase in expression. There may be an increase in oxidative stress with the lipid from elevated concentrations of free fatty acids.34 More research needs to be done to confirm the underlying mechanisms for the elevated cytokine response from OCA treatment in the Kupffer cells.

Activation of LXR with GW3965 promoted beneficial effects regarding upregulation of the transporter ABCG5 in the hepatocytes and suppression of inflammation in Kupffer cells. There is concern with the use of LXR agonists in the clinical setting, as there is some evidence to suggest that activation of LXR could contribute to the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. LXR is a strong activator of lipogenesis, and LXR suppression does reduce hepatic triglyceride accumulation in mouse models of fatty liver disease.4,35 Hepatic triglyceride accumulation could increase disease progression and severity. However, endotoxin-mediated injury in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is prevented with LXR activation in mouse models.36 As our model and work by El Kasmi et al suggest, phytosterols cause a similar endotoxin-mediated injury, which can lead to the liver disease in PNALD.3 The use of an LXR agonist would be appropriate to help reduce the inflammation caused by phytosterols and so warrants further examination in preclinical models of PNALD.

In conclusion, our findings support the idea that phytosterols in lipid emulsions present a potential risk to populations receiving TPN who are prone to bacterial exposure, such as infants with intestinal resection or sepsis line infection. The benefit of FXR (OCA) and LXR (GW3965) agonists in suppressing the effect of inflammation and potentially decreasing phytosterol levels through increased ABCG5 expression is promising. Preclinical models of PNALD that include both treatments would be informative to understand the more relevant mechanism in ameliorating the onset of PNALD during SO administration.

Clinical Relevancy Statement.

Parenteral nutrition–associated liver disease (PNALD) occurs in infants who are on parenteral nutrition for prolonged periods. This study provides further evidence that soy-based lipid emulsions can facilitate the onset of PNALD through enhancing hepatic inflammation. Furthermore, this study provides preliminary results from an investigation of 2 commercially available agonists of farnesoid X receptor and liver X receptor to suppress inflammation and facilitate clearance of phytosterols and bile acids consistently elevated in patients with PNALD.

Financial disclosure:

D. G. Burrin received lipid emulsions donated from Fresenius Kabi for the study. This work was supported in part by federal funds from the US Department of Agriculture (Agricultural Research Service, cooperative agreement 58-6250-6-001), the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Rhoads Research Foundation (G. Guthrie), the Texas Medical Center Digestive Diseases Center (National Institutes of Health, P30 DK-56338), and the National Institutes of Health (DK-094616; D.G.B). G. Guthrie was supported by a training fellowship from the National Institutes of Health (T32-DK07664).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Gura KM, Duggan CP, Collier SB, et al. Reversal of parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease in two infants with short bowel syndrome using parenteral fish oil: implications for future management. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):e197–e201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clayton PT, Bowron A, Mills KA, Massoud A, Casteels M, Milla PJ. Phytosterolemia in children with parenteral nutrition-associated cholestatic liver disease. Gastroenterology. 1993;105(6):1806–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Kasmi KC, Anderson AL, Devereaux MW, et al. Phytosterols promote liver injury and Kupffer cell activation in parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(206):206ra137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bai Q, Zhang X, Xu L, et al. Oxysterol sulfation by cytosolic sulfotransferase suppresses liver X receptor/sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c signaling pathway and reduces serum and hepatic lipids in mouse models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2012;61(6):836–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee MH, Lu K, Hazard S, et al. Identification of a gene, ABCG5, important in the regulation of dietary cholesterol absorption. Nat Genet. 2001;27(1):79–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vlaardingerbroek H, Ng K, Stoll B, et al. New generation lipid emulsions prevent PNALD in chronic parenterally fed preterm pigs. J Lipid Res. 2014;55(3):466–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter BA, Taylor OA, Prendergast DR, et al. Stigmasterol, a soy lipid-derived phytosterol, is an antagonist of the bile acid nuclear receptor FXR. Pediatr Res. 2007;62(3):301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elferink MGL, Olinga P, Draaisma AL, et al. LPS-induced down-regulation of MRP2 and BSEP in human liver is due to a post-transcriptional process. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G1008–G1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gay AN, Lazar DA, Stoll B, et al. Near-infrared spectroscopy measurement of abdominal tissue oxygenation is a useful indicator of intestinal blood flow and necrotizing enterocolitis in premature piglets. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46(6):1034–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vavassori P, Mencarelli A, Renga B, Distrutti E, Fiorucci S. The bile acid receptor FXR is a modulator of intestinal innate immunity. J Immunol. 2009;183(10):6251–6261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu W, Hou Y, Chen H, et al. Sample preparation method for isolation of single-cell types from mouse liver for proteomic studies. Proteomics. 2011;11(17):3556–3564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng K, Stoll B, Chacko S, et al. Vitamin E in new-generation lipid emulsions protects against parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease in parenteral nutrition-fed preterm pigs [published online January 16, 2015]. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verbeke L, Mannaerts I, Schierwagen R, et al. FXR agonist obeticholic acid reduces hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in a rat model of toxic cirrhosis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guthrie G, Kulkarni M, Vlaardingerbroek H, et al. Multi-omic profiles of hepatic metabolism in TPN-fed preterm pigs administered new generation lipid emulsions. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(9):1696–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brauner R, Johannes C, Ploessl F, Bracher F, Lorenz RL. Phytosterols reduce cholesterol absorption by inhibition of 27-hydroxycholesterol generation, liver X receptor alpha activation, and expression of the basolateral sterol exporter ATP-binding cassette A1 in Caco-2 enterocytes. J Nutr. 2012;142(6):981–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Croghan C, Egeghy P. Methods of dealing with values below the limit of detection using SAS. Paper presented at: Southeastern SAS User Group; September 22-24, 2003; St Petersburg, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziegler TR, Luo M, Estivariz CF, et al. Detectable serum flagellin and lipopolysaccharide and upregulated anti-flagellin and lipopolysaccharide immunoglobulins in human short bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294(2):R402–R410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wenfeng Z, Yakun W, Di M, Jianping G, Chuanxin W, Chun H. Kupffer cells: increasingly significant role in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2014;13(5):489–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biswas SK, Lopez-Collazo E. Endotoxin tolerance: new mechanisms, molecules and clinical significance. Trends Immunol. 2009;30(10):475–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kosters A, Tian F, Wan YJ, Karpen SJ. Gene-specific alterations of hepatic gene expression by ligand activation or hepatocyte-selective inhibition of retinoid X receptor-alpha signalling during inflammation. LiverInt. 2012;32(2):321–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Premkumar MH, Carter BA, Hawthorne KM, King K, Abrams SA. High rates of resolution of cholestasis in parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease with fish oil-based lipid emulsion monotherapy. J Pediatr. 2013;162(4):793–798, e791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda I, Tanaka K, Sugano M, Vahouny G, Gallo L. Discrimination between cholesterol and sitosterol for absorption in rats. J Lipid Res. 1988;29(12):1583–1591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhattacharyya AK, Connor WE. Beta-sitosterolemia and xanthomatosis: a newly described lipid storage disease in two sisters. J Clin Invest. 1974;53(4):1033–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrasco D, Ryseck RP, Bravo R. Expression of relB transcripts during lymphoid organ development: specific expression in dendritic antigen-presenting cells. Development. 1993;118(4):1221–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deng H, Maitra U, Morris M, Li L. Molecular mechanism responsible for the priming of macrophage activation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(6):3897–3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Godoy P, Hengstler JG, Ilkavets I, et al. Extracellular matrix modulates sensitivity of hepatocytes to fibroblastoid dedifferentiation and transforming growth factor beta-induced apoptosis. Hepatology. 2009;49(6):2031–2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain AK, Stoll B, Burrin DG, Holst JJ, Moore DD. Enteral bile acid treatment improves parenteral nutrition-related liver disease and intestinal mucosal atrophy in neonatal pigs. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302(2):G218–G224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J, Lu H, Lu YF, et al. Potency of individual bile acids to regulate bile acid synthesis and transport genes in primary human hepatocyte cultures. Toxicol Sci. 2014;141(2):538–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu L, Gupta S, Xu F, et al. Expression of ABCG5 and ABCG8 is required for regulation of biliary cholesterol secretion. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(10):8742–8747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ananthanarayanan M, Balasubramanian N, Makishima M, Mangelsdorf DJ, Suchy FJ. Human bile salt export pump promoter is transactivated by the farnesoid X receptor/bile acid receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(31):28857–28865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Posokhova EN, Khoshchenko OM, Chasovskikh MI, Pivovarova EN, Dushkin MI. Lipid synthesis in macrophages during inflammation in vivo: effect of agonists of peroxisome proliferator activated receptors alpha and gamma and of retinoid X receptors. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2008;73(3):296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambert G, Amar MJ, Guo G, Brewer HB Jr, Gonzalez FJ, Sinal CJ. The farnesoid X-receptor is an essential regulator of cholesterol homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(4):2563–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tall AR, Yvan-Charvet L. Cholesterol, inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(2):104–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soardo G, Donnini D, Domenis L, et al. Oxidative stress is activated by free fatty acids in cultured human hepatocytes. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2011;9(5):397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cha JY, Repa JJ. The liver X receptor (LXR) and hepatic lipogenesis: the carbohydrate-response element-binding protein is a target gene of LXR. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(1):743–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y, Han X, Bian Z, et al. Activation of liver X receptors attenuates endotoxin-induced liver injury in mice with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(2):390–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]