Abstract

The study explores work motivation of autistic adults through the lens of Self-Determination Theory (SDT). Twelve autistic employees (ages 28–47; 3 females) participated in semi-structured qualitative interviews about their work experience. Analysis combined inductive and deductive approaches, identifying motivational themes emerging from the interviews, and analyzing them according to SDT concepts. Two major themes emerged: (1) work motivation factors positioned on the self-determination continuum: income and self-reliance; a daily routine; social/familial internalized norms; meaning and contribution; and job interest; and (2) satisfaction of psychological needs at work, postulated by SDT: competence, social-relatedness, and autonomy and structure. Findings are discussed in relation to current literature, and practical applications are suggested for meeting the motivational needs of autistic employees and promoting employment stability.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10803-021-05185-4.

Keywords: Autistic adults, Employment, Self-determination theory, Work motivation

Introduction

Successful employment integration is a desired outcome in adulthood, but growing research shows that for autistic adults this goal is not easily achieved. Research assessing employment outcomes of autistic adults shows lower employment rates and inferior job conditions (e.g., fewer hours of work per week, lower salary, reduced job variation) in relation to the general population and to other adults with disabilities (Beenstock et al., 2020; Roux et al., 2013; Wilczynski et al., 2013). Further evidence suggests that while some autistic adults manage to obtain a job, fewer are able to maintain their position over time. Instead, they tend to experience postsecondary vocational disruption (Taylor & DaWalt, 2017; Taylor & Mailick, 2014).

Poor employment outcomes are related to both personal and environmental factors. Personal factors are associated with the autism diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), expressed in communication and social interaction difficulties in the workplace, as well as restricted repetitive patterns of behavior, and sensory sensitivities that affect one’s work experience and performance. Additional challenges stem from co-occurring neuro-psychiatric conditions such as ADHD, anxiety, and depression (Anderson et al., 2020; Black et al., 2020; Hedley et al., 2018; Scott et al., 2019), that are commonly associated with autism. Environmental factors that impede work possibilities may include stigma, a lack of modifications in recruitment processes, and work settings that do not enable proper accommodations (Black et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2020; Waisman-Nitzan et al., 2019). Therefore, efforts to promote employment outcomes of autistic adults call for collaboration between multiple stakeholders (Nicholas et al., 2018).

In attempt to improve vocational integration of autistic adults, several studies have aimed to identify factors that predict positive employment outcomes. Key factors highlighted include daily functional performance (e.g. daily living skills, communication abilities, self-care skills), family background and parental involvement, work environment accommodations, vocational supports, and transition services providing early workplace experience (Black et al., 2020; Hayward et al., 2019; Wong et al., 2020). The concept of self-determination has also received growing attention in recent years. Although the conceptualization of the term is somewhat different across disciplines and studies, definitions share the common theme of a behavior that is self-regulated, volitional, goal-directed and autonomous (Cheak-Zamora et al., 2020; Test et al., 2014; Wehmeyer et al., 2017). Scholars highlight fostering self-determination as an important element in high quality transition services for young autistic adults (Lee & Carter, 2012). Common work-related self-determination skills are self-advocating for job accommodations, solving problems in the workplace, fulfilling work responsibility and developing career plans (Wong et al., 2020). However, at least in the employment arena, associations between self-determination and employment outcomes did not show significant results (Wong et al., 2020; Zalewska et al., 2016). Thus, further research employing different measures and refined methods is needed in order to capture the role of self-determination in employment processes of autistic adults.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) of motivation has been suggested as a useful framework for navigating employment for autistic adults (Goldfarb et al., 2019). The theory is concerned with the motivation behind work choices, focusing on the degree to which an individual's behavior is self-determined. Employee motivation is a fundamental concept in work-related research, affecting performance, job satisfaction and commitment, and promoting job success (Kehr et al., 2018). However, this concept was seldom mentioned in relation to employment of autistic adults. Work motivation seems particularly relevant in this population, due to a commonly found mismatch between interests, individual skills and employment (Anderson et al., 2020). Consequently, in order to secure a job, autistic individuals are often obligated to work in jobs that might not fit their abilities and perform tasks they may not find interesting. These are demonstrated in the common gap between educational attainment and job characteristics in autism, known as 'over-education' (Baldwin et al., 2014). When jobs do not match interests or do not manifest abilities, a decrease in work motivation may follow, possibly leading to turnover and reduced employment stability.

Theories of motivation commonly differentiate intrinsic motivation (i.e., an engagement in work primarily for its own sake, because the work itself is satisfying or interesting) from extrinsic motivation (i.e. receiving something apart from the work itself, such as income and other benefits). SDT goes beyond this dichotomous view, and suggests a further distinction between autonomous and controlled motivation (Gagné & Deci, 2005). Autonomous motivation is experienced as self-determined, an act of choice and free will, while controlled motivation is determined by external factors. According to SDT, intrinsic motivation presents the highest level of autonomous behavior. However, extrinsic motivations for work can also be experienced as autonomous, even in the absence of an intrinsic drive (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

The extent of autonomy driving the behavior is described by means of a continuum ranging from amotivation, lacking self-determination, to intrinsic motivation, which is invariantly self-determined. Between amotivation and intrinsic motivation, different types of extrinsic motivation are situated, ordered by the degree of self-determination regulating them (Gagné & Deci, 2005). External regulation, the classic type of extrinsic motivation, is described as acting in order to obtain an external purpose. The succeeding extrinsic motivations are considered to have an internalized self-regulatory nature which does not demand an external contingency. Introjected regulation refers to behaviors led by ego-involvement and self-esteem, such as pressure to feel worthy and avoidance of shame. Identified regulation describes activities that are instrumentally important for personal goals, even though not enjoyable. For example, a teacher may be motivated to grade papers because she thinks it supports her students’ learning, even if she does not enjoy the activity. According to this model, the more internalized the motives are, the more self-determined the motivation is, promoting pathways to meaningful work (Duffy et al., 2016). See Table 1 for an illustration of the continuum, ranging from amotivation to intrinsic motivation.

Table 1.

The self-determination continuum (Gagné & Deci, 2005) according to levels and types of motivation

| Amotivation | Extrinsic motivation | Intrinsic motivation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absence of intentional regulation | External regulation | Introjected regulation | Identified regulation | Interest in and enjoyment of the task |

| Contingencies of reward and punishment | Self-worth contingent on performance—ego involvement | Importance of goals, values and regulations | ||

| Lack of motivation | Controlled motivation | Moderately controlled motivation | Autonomous motivation | Inherently autonomous motivation |

SDT further states that the process of internalization does not occur in a void but can rather be supported and promoted by satisfaction of three psychological needs in the workplace: competence, social-relatedness, and autonomy. Competence refers to a person's need for experiencing mastery of performance; Social-relatedness means being connected to others in meaningful ways; and autonomy provides a sense of authenticity, choice, and volition. Accordingly, SDT suggests that frustration of these needs can decrease motivation (Baard et al., 2004; Deci et al., 2001; Gagné et al., 2015; Reis et al., 2000). Among these basic psychological needs, addressing the need for social-relatedness appears to be especially relevant for autistic adults, since social difficulties are at the core of the autism diagnosis. While there is evidence of diminished motivation for social stimuli and social ties (Chevallier et al., 2012; Clements et al., 2018), studies that look into experiences of autistic adults clearly show an expression of social interest (Jaswal & Akhtar, 2018; Krieger et al., 2012), highlighting it as a potentially important work-related need. A central benefit of recognizing the relevance of these needs to autistic adults, is the idea that motivation is not just a given state a person either has or does not have, but rather something that can be facilitated. Thus, the theory holds the promising possibility of promoting self-determined motivation by providing an environment that responds to these needs, even in the absence of intrinsic motivation.

The purpose of the current study is to explore work motivation of autistic employees through the lens of SDT. Due to the preliminary nature of this inquiry, qualitative methodology was chosen. The research questions were: (1) What are the motivational factors that guide autistic adults in their work? (2) How do they relate to the SDT self-determination continuum? and (3) How are the needs for competence, social-relatedness and autonomy, defined by SDT, experienced and fulfilled by autistic adults in the workplace?

Method

Study Design

The research design is embedded within a realist/essentialist paradigm, assuming that experience and meaning are shared in a straightforward way, which is fitted for assessing the construct of motivation (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Semi-structured interviews were carried out, constructed and analyzed according to two methodological approaches: thematic analysis, offering an inductive (‘bottom up’) process, coding the content of the data in order to recognize emerging themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006); and theory-driven analysis (MacFarlane & O’Reilly-De Brún, 2012), analyzing the data in a deductive (‘top down’) process, relating the content to SDT constructs. These approaches inform the design of the interview protocol, which included both general questions regarding work motivation and specific questions relating to SDT concepts. These approaches also guide the process of data analysis.

Participants

A purposeful selection of participants was carried out through organizations and service-providers working with autistic adults (such as vocational counselors and vocational rehabilitation coaches). They were asked to forward an advertisement including information about the study to potential participants. The advertisement included information about the study and the criteria for participation. Inclusion criteria were: (1) a formal diagnosis of ASD by a psychiatrist or a psychologist, based on DSM-IV or DSM-5 criteria. An alternative criterion was the approval and formal recognition of an ASD diagnosis as the individual’s primary disability by the National Insurance Institute or by the Ministry of Labor, Social Affairs and Social Services of Israel—since they require a formal DSM-based diagnosis; (2) a minimum age of 18; (3) at least 12 years of formal education (i.e. completion of secondary education, which is a prerequisite for many jobs in the competitive job-market). (4) having worked for at least 6 consecutive months in competitive employment (i.e. earning a salary), within the last 2 years, either in the current job, or in a former one.

Participants who expressed interest in participating, contacted the researcher through an e-mail address or a phone number mentioned in the advertisement. They were contacted in response, in order to validate inclusion criteria, provide further information about the study, and schedule an interview. All of the participants who answered the advertisement and agreed to participate were included in the study, without further exclusion.

Interviews were conducted with twelve adults (3 females), ages 28–47 (M = 35.0, SD = 5.5). A sample size consisting of 12 participants was established according to the researcher's evaluation that data saturation was achieved at this point, meaning that no new information or themes were observed from additional interviews (Boddy, 2016). Participants’ educational level varied. One participant had a high-school diploma, one was a student beginning his academic education track, six attained non-academic vocational training in various fields, and four had an academic degree. As for job descriptions, five worked in jobs related to computer and science (e.g. quality assurance or data science), and the others had various jobs in fields such as music, food services, gardening, and administrative office-work. Participants' education and employment information are presented in Table 2. Most of the participants reported disclosing their diagnosis to their employers. Recruitment through vocational coaching and employment services perhaps influenced this proportion since work-place job coaching and accommodations require such disclosure.

Table 2.

Participants' education and employment information

| Participant | Gender | Age | Post-secondary education (highest degree) | Current/most recent job |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benny | M | 28 | Vocational training—technical | Salesmen—food industry |

| Michelle | F | 29 | Vocational training—caregiving | General worker—catering services |

| Eli | M | 29 | None | General worker—manufacturing |

| Joey | M | 31 | First year BA student—sciences | Usher—entertainment industry |

| Noah | M | 33 | Practical engineering—computer software | Quality assurance—telecommunications |

| Sarah | F | 34 | Vocational training—gardening | Gardening store employee |

| Andy | M | 35 | Bookkeeping; Software quality assurance | QA—educational institution |

| Nathan | M | 36 | Vocational training—software development | Data scientist—insurance sector |

| Rey | M | 37 | MA in arts | Musician and Technical support—IT |

| Shelley | F | 41 | BA in special education | Administrative assistant—health service organization |

| Leo | M | 41 | BA in design & engineering MA in science | Lab manager—educational institution |

| Aaron | M | 47 |

MA in humanities Software quality assurance |

Data labeling—automotive industry |

Instruments

Demographic Questionnaire

Participants were asked to fill out a short questionnaire collecting background information regarding: gender, age (at time of interview), post-secondary education, and current or most recent job.

Semi-structured Interview

According to the study’s design, the interview protocol included both general questions tapping into work motives, and specific questions relating to SDT concepts. At first, participants were asked to share information about occupational background, including prior and current work experiences. Succeeding questions related to general work motives, and motivational factors at the current job. For example, “why do you work”? and “what do you enjoy in your work”? These general questions were followed by more specific open-ended questions guided by the SDT conceptual framework, specifically addressing work experiences related to the three basic psychological needs (a) autonomy at work (e.g., “to what extent do you feel you have freedom of choice in doing your job”?); (b) relationships with the employer and co-workers at the workplace (e.g., “tell me about the social environment at your workplace”); and (c) the feeling of competence at work (e.g., “do you feel you are doing your job well”?). To broaden the scope of information collected, questions about interviewees’ perceptions of supporting factors and barriers in vocational integration were included. Finally, questions about interests and hobbies were asked in order to identify interest areas and their possible relation to employment. See Online appendix 1 for the full interview protocol.

Procedure

The research was approved by the ethics committee of the first author’s University. Coordination of the recruitment process and all interviews were carried out by the first author, a vocational psychologist with extensive experience counseling autistic adults. The interview took place in a quiet location agreed upon with the participant, mostly at a university office or the counseling clinic of the interviewer. Before the interview, participants expressed their informed consent in writing and filled out a written demographic questionnaire. Interviews were conducted in a fluent associative manner, allowing the participant to lead the conversation with little intervention, while the protocol was used by the interviewer to ensure all subjects were addressed. Therefore, the sequence of the questions varied from one interview to the other. The interviewer's professional background helped her navigate the interview and ensure that the questions were understood by the participants. At the end of the interview, participants were monetarily compensated for their time. Interview duration ranged between 48 and 75 min. Interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim. All names mentioned (of people, places, and institutions) were changed in the transcription process. Data were collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and therefore did not affect the participants’ experiences.

Data Analysis

Analysis involved two processes (Moran et al., 2014): (1) An inductive process using thematic analysis to identify motivational themes that emerged from the interview materials. (2) A deductive process in which themes were related to SDT constructs, observing congruencies with SDT, supplemented by unique aspects portrayed by the study's participants.

It included the following stages (Howard et al., 2019): (a) reading of the first transcript line by line; (b) noting descriptive comments and coding initial segments of the data which seemed relevant to the research questions; (c) noting emergent themes. Codes included both information that was ‘data-driven’, i.e., statements relating to work motivation in general, and ‘theory-driven’, i.e., statements relating to SDT constructs that address work-related needs; (d) repeating stages a-c for all transcripts; (e) gathering and reorganizing data into a coding book, allowing the researcher to attain a comprehensive overall assessment and identify emerging themes across accounts; (f) clustering themes into a list of master and sub-themes.

The coded data converged under two major themes. The first, related to general work motives, i.e., reasons that participants stated as to why they work or invest in their work. The theme was further sub-categorized into the different work motives mentioned in the data. Finally, each sub-theme was assessed in relation to a specific category of the self-determination continuum, (illustrated in Table 1). The second theme included statements about work-related needs and their satisfaction or frustration in the workplace. Sub-themes were informed by SDT construct of the basic psychological needs at work—competence, relatedness and autonomy.

The following measures were taken in order to enhance the credibility of the study (Brantlinger et al., 2005):

The interviews and initial analysis were carried out by the first author, a vocational psychologist who was aware of her position outside of the autistic community, possibly representing neurotypcial expectations of adjustment to work. This position was kept in mind when attentively listening to the work motives mentioned, some were not the common motives that come to mind (such as the need for a daily structure), and may seem different from career advancement or prestige, motivations that come to mind for neurotypicals.

In order to enhance reflectivity and trustworthiness, a reflective diary was sketched, documenting the interviewer's thoughts and feelings and their impact on study process and data interpretation. While documenting the first author’s thoughts, she noticed that for some of the participants, her presence was experienced as a representative of normative society and expectations, and the content of the interviews was shaped by their reactions to such figures (whether a tendency to please the other, or a defiance of work-related norms). These impressions complimented the motives that participants portrayed, as work itself is a societal construct to which they react in various ways.

After the initial analysis made by the interviewer, further analysis was conducted, in collaboration with the second and third authors, evaluating the data. Both are researchers with extensive knowledge and experience in the field of autism, rooted in different professional disciplines (clinical psychology and occupational therapy), thus conducting investigator triangulation to enhance credibility. Like the first author, they are not members of the autistic community. All authors reviewed the coding book comprising coding categories and themes and agreed upon the themes and sub-themes presented in the findings. The relations between the findings and SDT were specifically discussed in length, aiming to highlight which motives may appear to be more common in the general population and SDT literature, and which are more unique, possibly relating to employment circumstances of autistic adults.

Thick descriptions of the themes and demonstrative quotes are provided in order to support interpretations and conclusions suggested in the findings. Since the number of quotes that can be provided is limited in a report of this length, the number of participants making a statement associated with a theme is mentioned to enhance credibility of the analysis.

Findings

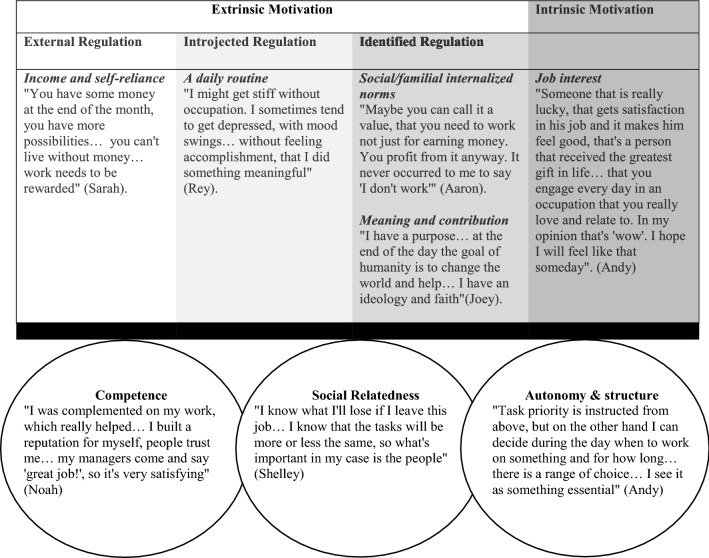

Two major themes emerged from the data. The first theme offers an answer to the first research question—what are the motivational factors that guide autistic adults in their work? It focuses on motives that the participants stated for working and putting effort into work. In the initial analysis, these motives were grouped into five sub-themes. Subsequently, the motives were positioned progressively along the self-determination continuum, from the most extrinsically regulated behavior, to more self-determined behavior. This procedure, positioning the motives in relation to the continuum, responds to the second research question asking how do they relate to the SDT self-determination continuum. The second theme corresponded with the psychological needs described by SDT, and with the third research question examining how the needs for competence, social-relatedness and autonomy are experienced and fulfilled by autistic adults in the workplace. The categories and representative quotes are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Emerging themes and quotes, positioned along to the self-determination continuum (Gagné & Deci, 2005), and in relation to the three psychological needs postulated by SDT

Theme 1: Work Motivation Positioned on the Self-determination Continuum

A variety of motivations for work emerged from the data. The majority of the participants reported more than one work motivation and different types of regulations guiding their behaviors simultaneously.

Sub-theme 1: Income and Self-reliance

Income was the most mentioned motivation for working, raised by ten of the participants. Often, participants who mentioned this motivation also said it is the main or most prominent reason why they go to work every day. For some it was a necessity, enabling subsistence. Others mentioned it in relation to self-reliance, permitting them to be their own masters, make decisions, and live independently without having to rely on their parents. Most of the participants did not refer to the level of income, but to the fact that they needed money for their everyday necessities:

"Why do I work? for a living… I don't need to elaborate because it's obvious… the only thing that's important to me is to work and earn really well so that I can move into my own apartment" (Eli).

Only a few mentioned they strive to reach a high salary, or progress in their income level. This externally regulated reason for working fits the common definition of extrinsic motivation, depending on a contingency of reward.

Sub-theme 2: A Daily Routine

Another common motivation to work, raised by seven of the participants, was having a daily routine, a structure arranging their daily lives. Work is experienced as a positive way of keeping busy and finding a sense of stability:

"It's not just the money, it's being occupied. I can't sit as home… [when I work,] I go out, I see places, I see people… it fills an important part of the day, there's a daily schedule, you don't feel like your life is wasting" (Michelle).

Concurrently, the absence of routine holds negative emotional consequences, leading to depression and feelings of emptiness. In relation to the self-determination continuum, the theme posits an internal motive, which fits the 'introjected regulation' category, valuing the positive effect of being active, and avoiding the negative emotions that arise from unemployment. While this theme does not fully match the motives commonly related to introjected regulation which emphasize ego-involvement and are more socially dependent (e.g., strive for prestige or shame resulting from failure) they are actions regulated by internal states of emotion.

Sub-theme 3: Social/familial Internalized Norms

Five participants referred to their work motivation as a basic given state, nested in family and society. Principles of work as a fundamental value were mentioned along with experiences of working from a relatively early age. Work was considered a 'normal' human experience and a way of being, that all individuals should be included in:

"That's what I saw at home. I was educated on work, responsibility and diligence. My brothers started to work at the age of 13. I also went to work. I think I would have gone crazy at home and I think that I am qualified enough to work. I know my value, in spite of all my difficulties". (Shelley).

The unquestioned norm of working was suggested to come at the expense of trying to find a job that fits abilities and needs:

"I always felt I had to work… I think you can say it motivated me all these years and as a consequence I worked in jobs that didn't fit me" (Aaron).

Others associated not working with negative values such as immorality, being a 'bum', and living on other people's expenses. To a further extent, work motivation was mentioned by Joey from a global modern economic perspective: "Without the institution called work, the human society would have not progressed…".

The experiences shared demonstrate how voices of family and values of society are internalized to become in inner-voice identifying with the value of work as an aim for itself, and thus can be positioned within the category of identified extrinsic regulation.

Sub-theme 4: Meaning and Contribution

Finding meaning in work was the second most common motive mentioned, raised by seven of the participants. Meaning was sometimes directly related to the role and tasks performed. Leo for example, worked as a lab manager in an educational environment, and was driven by being able to positively influence students: "This job is a mission, it's education. It's the job of making others love science". For others, the sense of meaning was indirect. Aaron found meaning in working in a company which manufactured products that could better the lives of the consumers, and even referred to the possible change led by the product as "healing". Shelley found meaning in giving service to clients in a medical setting and contrasted her experience to other jobs that, according to her, do not contribute to others, such as sales.

Two of the participants did not fulfill an aspect of contributing to others in their current job, but mentioned it as something they aspire to, or enjoyed in the past. They expressed a desire to do good and stated that even if not being able to manifest it in a paying job, they would volunteer: "I would have liked to be of service to someone… I would volunteer and donate money for different causes" (Andy). Future plans for higher education were also related to purpose and meaning. It is evident in the experiences shared that the values expressed through jobs and career goals reflect personal goals and as such also align with identified regulation.

Sub-theme 5: Job Interest

Eight of the participants addressed the issue of job interest, but only three of them mentioned some degree of interest in their current job and added reservations about their level of interest. Although participants were not asked to rate their work motives, descriptions suggest that it was not the first and most important motivation, and that this aim was compromised for the goal of finding and maintaining a job. Noah, working in software quality assurance, expressed overall satisfaction with his job, but nonetheless did not find inherent enjoyment in it:

"I learned software programming and there's nothing in this job that would make me want to invest more in the field in my spare time. I mostly do the job and just turn to a different mode".

Aaron also mentioned a certain extent of interest in his job, but it was not equivalent to his priority interest in history:

"It's relatively nice… I like that there's a huge variety… I have some interest in high-tech and that we're working on something innovative… but to tell you it's a source of joy? No, it isn't. If it was up to me, I would work in what I love…".

Other participants did not find particular interest in their jobs but did mention it as an aspiration. Two participants addressed the combination of income and interest as a contradiction. All in all, interest in a job did encompass a theme that threaded through the experiences of the participants, but other motivations were more prominent in work choice, and those who did achieve this aspiration did so partially.

Theme 2: Satisfaction of Psychological Needs

Participants extensively related to all three psychological needs defined by SDT as nutriments of the motivational process: competence, social-relatedness, and autonomy. All three components were mentioned as positive factors when satisfied, and negative factors when these needs were not fulfilled. Specific information regarding fulfillment of these needs emerged from the data, outlining how satisfaction can be achieved by the participants.

Sub-theme 1: Competence

All of the participants described experiences of competence in a positive light and experiences of incompetence in a negative context, mostly in relation to former jobs from which they were fired. Many described the feeling of competence as building up over time and established with experience:

"I persisted because once you are experienced at your job you know how to practice, it's like football training, that you perform many times and then you become a better player" (Joey).

The feeling of competence grew as the job became more familiar, concurrently with an elevated feeling of independence since having a familiar work schedule reduced dependence on instructions from others. A collective aspect of competence was that it depended on explicit feedback about the quality of the work. The feeling of competence was related to external evaluations.

Feelings of incompetence were sometimes associated with the autism diagnosis or other co-occurring disabilities such as dyscalculia, spatial orientation difficulties, insufficient initiative, or social deficits. The satisfaction of the need for competence was vividly portrayed in Rey's experience, after being repositioned within the organization:

"When they figured out I had a problem with costumers, they let me run quality assurance and sort hardware. They gave me boxes and boxes and boxes of hardware that wasn't surely working. And you need to clean it, and sort it, and rearrange, and I was very good at it... I was alone and I sorted, and everything was okay" (Rey).

The participants' descriptions stress the necessity of gaining work experience and external feedback in building competence. When a stable feeling of competence was achieved, it was contextually related to work satisfaction and motivation.

Sub-theme 2: Social-relatedness

Social-relatedness was a highly referenced theme, described by all of the participants. Two kinds of workplace relationships reflected the feeling of social-relatedness: friendly relationships with colleagues, and constructive relationships with employers, that included a sense of care and security.

Social-relatedness to Employers and Supervisors

Positive emotions were associated with employer-employee relationships that included compassion and respect. Participants mentioned a specific understanding of their needs due to their diagnosis, and flexibility in relation to these needs, such as individual work hours or longer breaks. These aspects were evident in Noah's words:

"I was accepted to work by a person who treated me very respectfully. He learned quickly that if I need to stay overtime, he should give me an early notice so I can prepare myself… the managers were attuned to my needs".

A positive relationship with an employer was also evident in Sarah's description portraying a reciprocal relationship and feelings of caring and empathy:

"When the owner and I work together—it's positive… the dynamic is good, there's cooperation. Maybe because it's one-on-one… you can trust… and also say the unpleasant things… feedback, what you liked, what you didn't like… you sometimes need to sit together and ask, how are you feeling? Is there something you need?".

Participants also gave examples of reassurance they received from their supervisors, that gave them a sense of security. Aaron thankfully described a situation in which his manager protected his rights when HR wanted to cut back in his days off and successfully demanded his work conditions are preserved.

In contrast, examples of mistreatment were described as negatively affecting the work experience:

"If someone speaks to me in an unpleasant way, I take it personally and then it brings me to, I wouldn't say anxiety, but it would lead to a touch of depression. How could he speak to me that way? What did I do?" (Rey)

The influence of negative experiences in employer-employee relationships is evident in the data and reflects a personal feeling of hurt and injustice.

Social-relatedness to Colleagues

Participants articulated the feeling of social-relatedness through descriptions of work anecdotes that reflected positive feelings of being part of a social atmosphere, sharing inner-jokes and being accepted:

"I had an amazing team. Well connected, knew the work… we also had funny moments… jokes and nonsense, laughter. You sit and talk about what you're going through and then someone throws a comment and then there's a joke. There was a really really good feeling of friendship" (Joey).

As with employer-employee relationships, a sense of reciprocity was also evident as contributing to a feeling of social-relatedness and satisfaction: "I feel I could ask for help, and they would come and help me. And when they ask, I would come. It feels like a reciprocal interaction" (Eli).

Not all participants shared experiences of ideal social interactions, but the importance of the factor and a yearning for closer social relationships at work was evident:

"Relationships are okay. We're not friends outside of work, but we're like a family in the workplace… we sit together and see each other more than any other person in the world. A comfortable and positive atmosphere. But the restaurant vouchers destroyed social relationships. Each person prefers something else and eats alone. In my former workplace, there was time in the cafeteria when everyone ate lunch together" (Nathan).

For some of the participants, the feeling of social relatedness specifically differentiated a good workplace from a bad one:

"I had good company, people that are warm and supportive…everything flows like a river, fun and smooth… in other places, like now, I don't have the fun. I come without energy." (Michelle).

Social-relatedness was also mentioned as a buffer, helping to manage work pressure: "We are constantly being monitored so we make use of the time to do more… it's a lot of pressure, but on the other hand, when you're together then there's the feeling that everyone pitches in and contributes" (Aaron).

The various experiences shared reflect the centrality of social-relatedness in the workplace. Satisfaction of the need positively influences well-being at work, and negative consequences follow when these needs are unfulfilled.

Sub-theme 3: Autonomy and Structure

Eleven of the participants referred to autonomy and choice as a relevant and meaningful factor in their job. The importance of autonomy was evident along various stages of the work integration process: choosing post-secondary education; choosing a specific workplace; choosing which tasks to perform as part of the job; and managing the daily schedule. One of the participants described work itself as promoting a feeling of autonomy and independence in transition to adulthood.

There was some variability in the degree of the need for autonomy. Michelle expressed the highest need for support, mentioning difficulty with decision making, needing to constantly consult with a trusted friend. She also expressed a need for a very structured daily routine, with little room for change. On the other end of the scale, Sarah expressed a high need for autonomy, reflected in a preference for working as a self-employed event-designer:

"Tell me in the morning what you want me to do. But in the middle of the day don't tell me 'you didn't do this, you didn't do that'. That’s unacceptable because I have my order. I don't work the way that other people plan".

Most of the participants ranged between these two ends.

The need for choice and autonomy was expressed along with a preference for a stable structure and/or a person that can offer advice. In fact, it appears that structure functions as a facilitator, enabling the fulfillment of the need for autonomy. Participants mostly preferred to be given a few options to choose from, instead of having an undefined range of possibilities. For one participant autonomy took the form of disobedience and unwillingness to conform to the job rules that he didn't agree with. This was an exception, as most participants described a combination of understanding the norms and demands of the job, seeking a structure, while still having a sense of choice and control.

Discussion

The current study offers a first look into work motivation of autistic adults through the lens of SDT. We combined inductive and deductive approaches that allowed to identify motivational themes emerging from interviews, and then to analyze them according to SDT concepts. Findings highlight the motives that drive participants to enter the work force and sustain their jobs, situate them in relation to the self-determination continuum and to the subjective experiences of satisfaction and frustration of psychological needs in the workplace.

Next, we present the associations between the work motives found and current literature, highlighting resemblances to the SDT literature along with unique characteristics of autistic employees. Further, we discuss ways to promote satisfaction of basic psychological needs of autistic employees and suggest practical implications of the study’s findings.

Work Motivation Positioned on the Self-determination Continuum

The first and most widely stated motivation for work was earning money. It is apparent from the data that money is not an aim by itself, but a mean for achieving independence and basic subsistence. This motivation is in line with Maslow's (1943) classic hierarchical model of psychological needs defining that behavior is governed first by physiological and safety needs, deemed more urgent for survival. At the same time, it also expresses a desire for self-support, reducing reliance. Further on the continuum, the need for daily occupation was also a widely stated work motivation. This motive is not commonly demonstrated in the STD literature. Although the participants held fairly stable jobs, many of them described a discontinuous employment history, common for autistic adults (Taylor & DaWalt, 2017). Given the negative influence of unemployment on mental health (Paul & Moser, 2009), it may be that individuals who experienced the undesirable consequences of being unemployed, have learned to appreciate the daily routine that a regular job can offer.

Other motives showed a more internalized drive for work. The process of internalization was demonstrated through references to environmental factors, such as family values and cultural conventions. This process highlights how familial and societal values are intertwined with the voices of the participants and their value systems. Parents are often an ongoing source of support in the transition of autistic youth to adulthood, and parental expectations were shown to impact adult outcomes in employment (Carter et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2019; Kirby, 2016). Our findings portray a possible underlying process through which familial values are internalized to become a self-determined work motivation. Furthermore, they demonstrate the influence of cultural norms establishing the centrality of work aspirations, and align with previous findings that show the influence of cultural scripts on self-perception of autistic people (Brezis et al., 2016).

Other internalized motives describing a sense of purpose and meaning were the most self-determined extrinsic motivations mentioned. Participants strive to find meaning in their jobs, on different levels—the role, the organization and the workforce. This is a central aspect in SDT literature (Gagné & Deci, 2005), and a vital component in the possibility of maintaining work motivation in limiting circumstances (Duffy et al., 2016). Autistic employees appear to share this drive with the general population and can benefit from active attempts to promote their connectedness to organizational goals.

The motivation for working in an interesting job, (i.e., 'intrinsic motivation'), was addressed by the participants, but rarely fulfilled. Even participants who found some interest in their job, would have preferred a different vocation if interests were the main motivation driving them. For others, manifesting interests was not a goal they achieved at all, or even expected to. In a recent study examining the role of self-determination in shaping university experiences (Lei & Russell, 2021), autistic students stated being motivated only to pursue goals that aligned with their intrinsic interests, focusing on specific related professions. In our group of employed autistic adults who maintain a steady job, interests do not appear to be a primary consideration. Arguably, motivations and characteristics that drive and enable academic success may differ from those that lead to job integration, adding complexity to the transition from academic education to job-market integration.

Satisfaction of Psychological Needs

The minimal emphasis in the data on intrinsic motivation for work, highlights the importance of recognizing other motivational incentives. These can be found in the need for competence, social-relatedness and autonomy defined by SDT. Findings support the notion that satisfaction of these needs plays an important role in work integration of autistic adults, and further point to modifications specifying how these needs could be satisfied. Autistic adults are often considered to prefer and even enjoy monotonic repetitive tasks (Hagner & Cooney, 2005). Our data suggests that these tasks are not necessarily liked, in the sense of enjoyment or intrinsic motivation. Even so, it may be that the familiarity of the structured activity, along with the feeling of competence it fulfills, may outweigh the desire to work in an interesting job and help maintain motivation over time. Participants' accounts in the current study mostly associate an established feeling of competence to the existence of explicit feedback from managers. Previous studies support this relation, suggesting that autistic individuals show better assessment of self-knowledge when it is inferred through external cues (Dritschel et al., 2010; Mynatt et al., 2014) and prefer an explicit manner of communication (Waisman-Nitzan et al., 2019).

Findings show the centrality of social-relatedness through many references and anecdotes about the motivational implications of social experiences. Our findings support previous research stating that that even though autistic people might appear less socially interested, they often crave social relationships, and seek them in the workplace (Krieger et al., 2012; Pfeiffer et al., 2018). Furthermore, findings associate social relatedness to managerial figures who are familiar with the autism diagnosis and allow proper workplace accommodations. These aspects were previously related to positive employment outcomes (Lindsay et al., 2021. The undesirable consequences of negative relationships in the workplace align with SDT literature in the general population (Van den Broeck et al., 2016), and in employees with psychiatric disabilities (Moran et al., 2014), but seem especially harmful for autistic employees who may not easily recuperate from such detrimental employment experience. Recent findings suggest that highly negative employment-related social interactions can cause individuals to be left out of the work cycle for long periods of time (Anderson et al., 2020), perhaps also by consequently reducing work motivation.

Findings highlight autonomy as a necessity in the workplace, in line with the literature supporting recent findings suggesting autonomy is an occupational enabler (Hayward et al., 2019). In the current study, satisfaction of autonomy mostly occurs under the specific condition of a structured work environment. The relation between autonomy and structure as complimenting each other in fostering motivation was previously suggested within SDT literature in a learning context (Jang et al., 2010), and appears to also be a substantial factor in employment contexts of autistic adults. Studies in the general population show the positive aspects of creating a work environment that supports employee autonomy through acknowledging employee perspectives, and providing them with opportunities for volition over what they do and how they do it (Baard et al., 2004; Moreau & Mageau, 2012). A proposed way of promoting autonomy satisfaction is through allowing 'job crafting', a method by which employees reshape their tasks to create a better fit between their individual skills and preferences and the demands of their jobs (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Slemp et al. (2015) link job crafting to autonomy supportive work climates, which synergistically promote well-being in the workplace. Allowing autistic employees, the opportunity to craft their own jobs can be beneficial in answer to the differences in autonomy needs pronounced by the participants in this study. For example, employees might request to obtain more or less decision-making authority according to their preferences and control the extent of sameness vs. change and diversity in their jobs. This preposition aligns with previous studies stressing the role of both individual workplace behaviors and the environmental/organizational context in promoting employment success of autistic adults (Black et al., 2020; Goldfarb et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2020). The value of job crafting seems particularly relevant for autistic employees who often present heterogenous profiles of interests, abilities and emotional sensitivity (Goldfarb et al., 2019).

Practical Implications

Findings suggest a number of practical implications for stakeholders dedicated to promoting work integration of autistic adults. For the individual, a focus on motivation can help an informed process of work choice, weighing advantages and disadvantages in different work setting and making a choice that aligns with personal work-motives and enables need fulfillment. Career counselors can enrich counseling processes by addressing the SDT construct of work motivations and psychological need fulfillment and assisting clients in understanding their needs and setting priorities. On the organizational level, the outcomes highlight factors that form an autonomy-supportive environment for autistic employees, for example: providing clear instructions and expectations and offering constructive feedback can promote competence; supportive communication with the employer and a sense of respect and compassion can promote social-relatedness; and providing a clear structure and allowing the employee to prioritize can potentially enhance autonomy. Furthermore, connecting employees to organizational goals can support the motivation for meaning and purpose. Autonomy promoting practices such as 'job crating' appear to be highly relevant. Findings can also help parents understand the work-related motivational processes of their children, and minimize potential discrepancies in employment goals and preferences that sometimes occur (Anderson et al., 2020).

Some of these suggested practices may already be implemented in programs aimed to promote employment integration of autistic youth and young adults such as project 'SEARCH plus ASD supports' (Wehman et al., 2013) and 'TEACCH supported employment program' (Keel et al., 1997). For example, both programs include job coaches who help create structured schedules and clearly defined work tasks, but also promote self-monitoring and collaborative goal setting. This practice aligns with the basic psychological need for autonomy along with a stable structure. Furthermore, the program goals of promoting interaction with co-workers by improving the employees' social skills and educating coworkers about autism potentially promote social relatedness. Nevertheless, the theoretical lens of SDT can offer an understanding of the needs that underlie these employment-related goals. When a decline in motivation occurs, assessment of possible need-frustration, can help highlight specific areas that need attention, such as increasing a feeling of social-relatedness by encouraging social-encounters or promoting the need for autonomy by purposefully offering a choice between several possibilities. The SDT perspective can be especially relevant given that these programs usually offer internships that include a wide variety of tasks for which a profession is not a prerequisite, thus potentially limiting possibilities for the manifestation of intrinsic motivation.

Findings do not contradict or dismiss the aspired goal of matching skills, interests, and jobs to satisfy intrinsic motivation. At the same time, accumulating research on employment of autistic adults informs us that barriers are high, and compromise is often essential. For individuals who are not fortunate to work in a job they inherently enjoy, applications of the theory hold the potential to boost motivation and improve job outcomes.

Limitations

The aim of this qualitative study was to achieve an in-depth understanding of the participants' work motivation through the lens of SDT, and to suggest inferences that may inform us about the general population of autistic employees. We acknowledge the relative homogeneity of the sample, which includes cognitively-able and mostly educated autistic adults. Therefore, transferring the findings to a wide population of autistic adults should be considered with caution. The study focuses on working autistic adults with fairly stable jobs, that may be more inclined to compromise. Lastly, participants were mostly reached by service providers offering vocational support to autistic adults. It is possible that such participants had more barriers to overcome, influencing their decision to seek help. Such barriers could have limited the options of finding an intrinsically motivating job, a possibility that may be more common in a wider population of autistic adults.

Further Research Directions

Expanding research to the wider autism community, both more independent and less independent (such as sheltered employment), can give a broader picture about work motivations of this population. Additionally, conducting similar research with unemployed participants can promote identification of factors that impede employment integration, motivations that are difficult to satisfy, or aspects that relate to a-motivation. These complementary viewpoints can form a comprehensive picture of motivations and needs that promote or inhibit work integration of autistic adults. A wider, more inclusive framework can extend the reach of employment interventions to individuals dealing with prolonged unemployment, and consequently diminish unemployment rates.

Given the qualitative methods used, motivations were not scaled and participants were not questioned about their relative importance. They each expressed a number of motives, that like in real life, are interrelated. SDT research has established tools that enable a quantitative examination of self-determined motivation, need satisfaction and associations between these factors. Quantitative studies that validate the applicability of these tools are necessary in order to generalize and validate the relevance of SDT for the population of autistic adults. Finally, longitudinal data, taken in different time-points of the employment integration process may reveal possible changes in motivation over time, and assess effects of experience, intervention programs or other life events on work motivation.

Conclusion

The current research offers a preliminary examination of work motivation of autistic adults. Findings support the relevance of the SDT framework and lead to practical implications, suggesting not only 'what works' in employment integration practices, but also why certain environment adjustments are important, and what motivational needs they serve. Emphasis on the work environment, which can be shaped and adjusted in order to respond to the workers' needs, contributes the encouraging notion that motivation is not just a given state, but something that can be facilitated towards a sense of self-determination.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study has been supported graduate research grants to Yael Goldfarb from the Organization for Autism Research and the National Insurance Institute of Israel. We thank the participants for devoting their time and sharing their valuable expericnes.

Author Contributions

YG, EG and OG designed the study. YG collected the data and analyzed it with EG and OG. YG drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in revising the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee, University of Haifa.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C, Butt C, Sarsony C, Anderson C. Young adults on the autism spectrum and early employment—related experiences: Aspirations and obstacles. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04513-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baard PP, Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic need satisfaction: A motivational basis of performance and well-being in two work settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2004;34(10):2045–2068. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02690.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin S, Costley D, Warren A. Employment activities and experiences of adults with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014;44(10):2440–2449. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2112-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenstock M, Pinto O, Rimmerman A. Transition into adulthood with autism spectrum disorders: A longitudinal population cohort study of socioeconomic outcomes. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1044207320943590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black MH, Mahdi S, Milbourn B, Scott M, Gerber A, Esposito C, Falkmer M, Lerner MD, Halladay A, Ström E, D’Angelo A, Falkmer T, Bölte S, Girdler S. Multi-informant international perspectives on the facilitators and barriers to employment for autistic adults. Autism Research. 2020 doi: 10.1002/aur.2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy CR. Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research. 2016 doi: 10.1108/QMR-06-2016-0053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brantlinger E, Jimenez R, Klingner J, Pugach M, Richardson V. Qualitative studies in special education. Exceptional Children. 2005;71(2):195–207. doi: 10.1177/001440290507100205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brezis RS, Singhal N, Daley T, Barua M, Piggot J, Chollera S, Mark L, Weisner T. Self- and other-descriptions by individuals with autism spectrum disorder in Los Angeles and New Delhi: Bridging cross-cultural psychology and neurodiversity. Culture and Brain. 2016;4(2):113–133. doi: 10.1007/s40167-016-0040-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter EW, Austin D, Trainor AA. Predictors of postschool employment outcomes for young adults with severe disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 2012;23(1):50–63. doi: 10.1177/1044207311414680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheak-Zamora NC, Maurer-Batjer A, Malow BA, Coleman A. Self-determination in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2020;24(3):605–616. doi: 10.1177/1362361319877329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Cohn ES, Orsmond GI. Parents’ future visions for their autistic transition-age youth: Hopes and expectations. Autism. 2019;23(6):1363–1372. doi: 10.1177/1362361318812141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier C, Kohls G, Troiani V, Brodkin ES, Schultz RT. The social motivation theory of autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2012;16(4):231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements CC, Zoltowski AR, Yankowitz LD, Yerys BE, Schultz RT, Herrington JD. Evaluation of the social motivation hypothesis of autism a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(8):797–808. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM, Gagné M, Leone DR, Usunov J, Kornazheva BP. Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27(8):930–942. doi: 10.1177/0146167201278002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dritschel B, Wisely M, Goddard L, Robinson S, Howlin P. Judgements of self-understanding in adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Autism. 2010;14(5):509–518. doi: 10.1177/1362361310368407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy RD, Blustein DL, Diemer MA, Autin KL. The psychology of working theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2016;63(2):127–148. doi: 10.1037/cou0000140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagné M, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2005;26(4):331–362. doi: 10.1002/job.322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gagné M, Forest J, Vansteenkiste M, Crevier-Braud L, van den Broeck A, Aspeli AK, Bellerose J, Benabou C, Chemolli E, Güntert ST, Halvari H, Indiyastuti DL, Johnson PA, Molstad MH, Naudin M, Ndao A, Olafsen AH, Roussel P, Wang Z, Westbye C. The multidimensional work motivation scale: Validation evidence in seven languages and nine countries. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. 2015;24(2):178–196. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2013.877892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb Y, Gal E, Golan O. A conflict of interests: A motivational perspective on special interests and employment success of adults with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2019;49(9):3915–3923. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb Y, Gal E, Golan O. Employment of adults with ASD: A motivational perspective. In: Volkmar F, editor. Encyclopedia of autism spectrum disorders. Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hagner D, Cooney BF. “I Do That for Everybody”: Supervising employees with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2005;20(2):91–97. doi: 10.1177/10883576050200020501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward SM, McVilly KR, Stokes MA. Autism and employment: What works. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2019;60:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2019.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hedley D, Cai R, Uljarevic M, Wilmot M, Spoor JR, Richdale A, Dissanayake C. Transition to work: Perspectives from the autism spectrum. Autism. 2018;22(5):528–541. doi: 10.1177/1362361316687697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard K, Katsos N, Gibson J. Using interpretative phenomenological analysis in autism research. Autism. 2019;23(7):1871–1876. doi: 10.1177/1362361318823902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H, Reeve J, Deci EL. Engaging students in learning activities: It is not autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2010;102(3):588–600. doi: 10.1037/a0019682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaswal VK, Akhtar N. Being vs. appearing socially uninterested: Challenging assumptions about social motivation in autism. Journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2018 doi: 10.1017/S0140525X18001826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KR, Ennis-Cole D, Bonhamgregory M. Workplace success strategies for employees with autism spectrum disorder: A new frontier for human resource development. Human Resource Development Review. 2020;19(2):122–151. doi: 10.1177/1534484320905910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keel JH, Mesibov GB, Woods AV. TEACCH-supported employment program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1997 doi: 10.1023/A:1025813020229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehr HM, Strasser M, Paulus A. Motivation and volition in the workplace. In: Jutta Heckhausen HH, editor. Motivation and action. 3. Springer; 2018. pp. 819–852. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby AV. Parent expectations mediate outcomes for young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016;46(5):1643–1655. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2691-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger B, Kinébanian A, Prodinger B, Heigl F. Becoming a member of the work force: Perceptions of adults with Asperger Syndrome. Work. 2012;43(2):141–157. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GK, Carter EW. Preparing transition-age students with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders for meaningful work. Psychology in the Schools. 2012;49(10):988–1000. doi: 10.1002/pits.21651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lei J, Russell A. Understanding the role of self-determination in shaping university experiences for autistic and typically developing students in the United Kingdom. Autism. 2021 doi: 10.1177/1362361320984897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay S, Osten V, Rezai M, Bui S. Disclosure and workplace accommodations for people with autism: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2021;43(5):597–610. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1635658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFarlane A, O’Reilly-De Brún M. Using a theory-driven conceptual framework in qualitative health research. Qualitative Health Research. 2012;22(5):607–618. doi: 10.1177/1049732311431898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review. 1943;50(4):370–396. doi: 10.1037/h0054346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moran GS, Russinova Z, Yim JY, Sprague C. Motivations of persons with psychiatric disabilities to work in mental health peer services: A qualitative study using self-determination theory. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2014;24(1):32–41. doi: 10.1007/s10926-013-9440-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau E, Mageau GA. The importance of perceived autonomy support for the psychological health and work satisfaction of health professionals: Not only supervisors count, colleagues too! Motivation and Emotion. 2012;36(3):268–286. doi: 10.1007/s11031-011-9250-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mynatt BS, Gibbons MM, Hughes A. Career development for college students with Asperger’s syndrome. Journal of Career Development. 2014;41(3):185–198. doi: 10.1177/0894845313507774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas DB, Mitchell W, Dudley C, Clarke M, Zulla R. An ecosystem approach to employment and autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2018;48(1):264–275. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul KI, Moser K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2009;74(3):264–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer B, Brusilovskiy E, Davidson A, Persch A. Impact of person-environment fit on job satisfaction for working adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2018;48(1):49–57. doi: 10.3233/JVR-170915. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Sheldon KM, Gable SL, Roscoe J, Ryan RM. Daily well-being: The role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26(4):419–435. doi: 10.1177/0146167200266002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roux AM, Shattuck PT, Cooper BP, Anderson KA, Wagner M, Narendorf SC. Postsecondary employment experiences among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(9):931–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 2000;25(1):54–67. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott M, Milbourn B, Falkmer M, Black M, Bӧlte S, Halladay A, Lerner M, Taylor JL, Girdler S. Factors impacting employment for people with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. Autism. 2019;23(4):869–901. doi: 10.1177/1362361318787789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slemp GR, Kern ML, Vella-Brodrick DA. Workplace well-being: The role of job crafting and autonomy support. Psychology of Well-Being. 2015 doi: 10.1186/s13612-015-0034-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, DaWalt LS. Brief report: Postsecondary work and educational disruptions for youth on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2017;47(12):4025–4031. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3305-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Mailick MR. A longitudinal examination of 10-year change in vocational and educational activities for adults with autism spectrum disorders. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50(3):699–708. doi: 10.1037/a0034297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Test DW, Smith LE, Carter EW. Equipping youth with autism spectrum disorders for adulthood: Promoting rigor, relevance, and relationships. Remedial and Special Education. 2014;35(2):80–90. doi: 10.1177/0741932513514857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Broeck A, Ferris DL, Chang CH, Rosen CC. A review of self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. Journal of Management. 2016;42(5):1195–1229. doi: 10.1177/0149206316632058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waisman-Nitzan M, Gal E, Schreuer N. Employers’ perspectives regarding reasonable accommodations for employees with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Management and Organization. 2019;25(4):481–498. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2018.59. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wehman P, Schall C, McDonough J, Molinelli A, Riehle E, Ham W, Thiss WR. Project SEARCH for youth with autism spectrum disorders: Increasing competitive employment on transition from high school. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2013;15(3):144–155. doi: 10.1177/1098300712459760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wehmeyer ML, Shogren KA, Little TD, Lopez SJ. Development of self-determination through the life-course. Springer. 2017 doi: 10.1007/978-94-024-1042-6_7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski SM, Trammell B, Clarke LS. Improving employment outcomes among adolescents and adults on the autism spectrum. Psychology in the Schools. 2013;50(9):876–887. doi: 10.1002/pits.21718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J, Coster WJ, Cohn ES, Orsmond GI. Identifying school-based factors that predict employment outcomes for transition-age youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesniewski A, Dutton JE. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review. 2001;26(2):179–201. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2001.4378011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zalewska A, Migliore A, Butterworth J. Self-determination, social skills, job search, and transportation: Is there a relationship with employment of young adults with autism? Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2016;45(3):225–239. doi: 10.3233/JVR-160825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.