Abstract

The NIH-funded Alzheimer’s Biomarker Consortium Down Syndrome (ABC-DS) and the European Horizon 21 Consortium are collecting critical new information on the natural history of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) biomarkers in adults with Down syndrome (DS), a population genetically predisposed to developing AD. These studies are also providing key insights into which biomarkers best represent clinically meaningful outcomes that are most feasible in clinical trials. This paper considers how these data can be integrated in clinical trials for individuals with DS. The Alzheimer’s Clinical Trial Consortium - Down syndrome (ACTC-DS) is a platform that brings expert researchers from both networks together to conduct clinical trials for AD in DS across international sites while building on their expertise and experience.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, down syndrome, clinical trials

Introduction

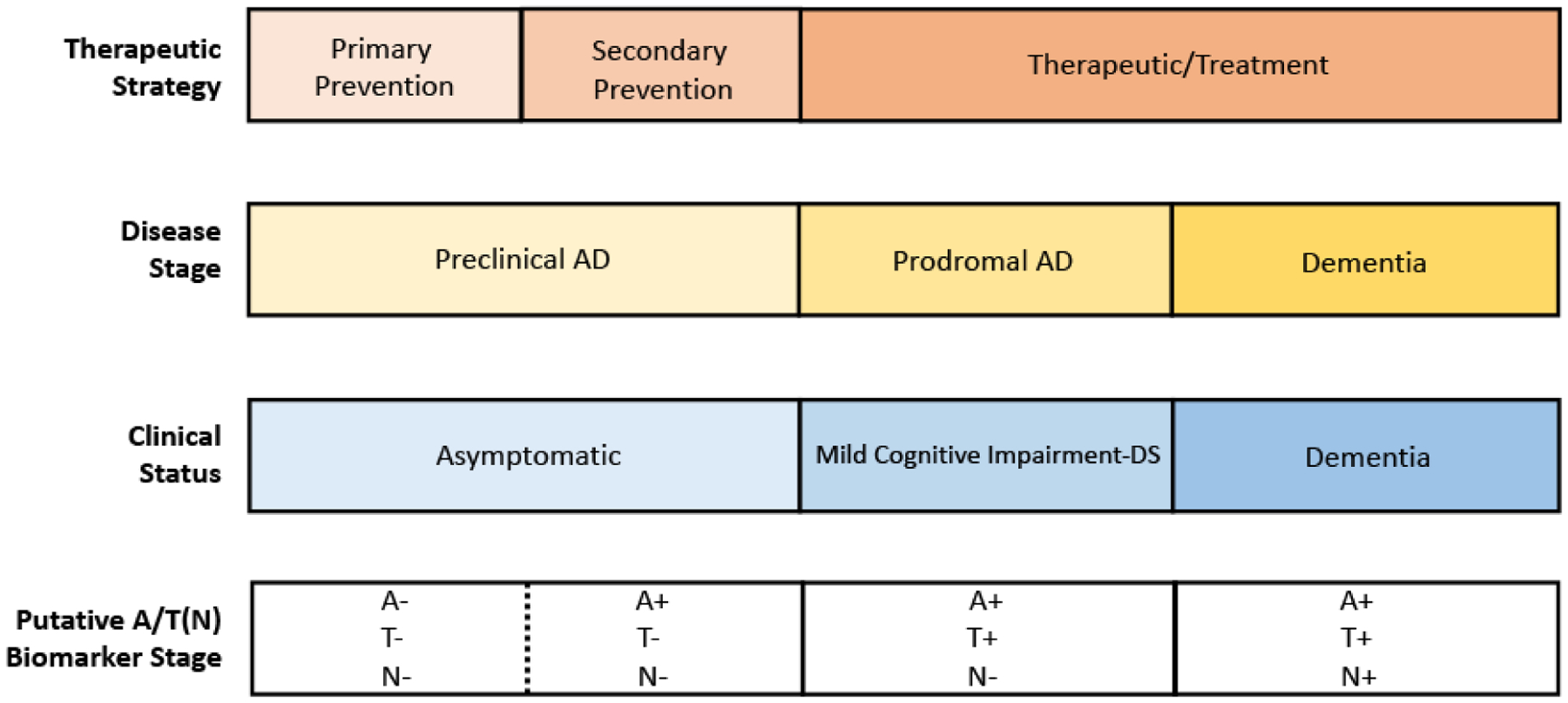

In Down syndrome (DS), which in over 95% cases is caused by trisomy of chromosome 21, the triplication of the APP gene results in increased APP protein expression along with increased Aβ production (1). This leads to the almost universal presence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) neuropathology by the age of 40 years in people with DS and a very high prevalence rate of dementia over the ensuing 20–30 years (2). AD in DS (DSAD) is remarkably similar to AD in the non-DS population, such as autosomal dominant AD (ADAD) and sporadic, late-onset AD (LOAD) in the general population but moderated by the impact of DS neurodevelopmental factors. Although the extra copy of APP, due to its gene dose effect is the key upstream etiology of neurodegeneration that places a necessary major focus on the amyloid cascade, there are multiple downstream manifestations and biomarkers that need to be characterized. Nonetheless, it is believed that the continuum of AD, that is, the asymptomatic or ‘preclinical’, mildly symptomatic or ‘prodromal’ and fully symptomatic or ‘dementia’ stages progress sequentially in DSAD, just as they do in the other forms of AD. Understanding the predictive relationship between longitudinal changes in standard AD biomarkers and clinical outcomes is therefore critical to their successful implementation in clinical trials for DSAD (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Anchoring Clinical Symptoms with Robust Biomarkers Understanding longitudinal change in biomarkers will be critical for staging individuals with DS along the AD continuum and necessary for clinical trials

A-Amyloid, T-Tau; N-Neurodegeneration

Biomarkers play a critical role in drug development including characterization of the disease state and its progression as well as a proxy for potential efficacy of interventions. Following drug discovery, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies, and lead optimization, the candidate compound then enters the clinical trial stages of drug development comprised of phase I, II and III. Phase I studies are first-in-human exposures beginning with single ascending doses and progressing to multiple ascending doses in small cohorts of healthy human volunteers. Phase II studies focus on collecting additional safety and tolerability data as well as biomarker data such as target engagement supporting modification of disease progression. Phase III studies are large, multicenter studies that collect data on clinical efficacy.

In considering the design of clinical trials for DSAD, whether they be for prevention or modification of the disease process, it will be essential to identify the appropriate sample population (e.g. age range, baseline intellectual functioning), the safety profile of the intervention (e.g. pharmacokinetics, common adverse events, especially those that may be unique to people with DS), as well as the proper outcome measures that will reflect impact on objective measures of disease progression and presumably clinically meaningful outcomes.

To support a claim that biomarker data and clinical results are mediated by the same underlying mechanism, the two must be strongly correlated. Preliminary correlations have been established for certain cognitive outcomes and AD biomarkers, which illustrate remarkable similarities in the behavior of biomarkers in DSAD, ADAD and LOAD, as will be discussed in the next few paragraphs.

In DS, where intellectual disability (ID) is neurodevelopmental and relatively stable in early adulthood, preceding cognitive decline associated with AD, the question arises as to what degree cognitive changes are related to the emergence of the clinical features of AD. Given the immense variability in the pre-morbid or baseline cognitive functioning in DS, it can be extremely challenging to assess cognitive change, especially among those with limited premorbid expressive language skills and/or severe ID (3). This fact further highlights the need for validated AD biomarkers in this population. Results from recent biomarker studies suggest that we may be able to accurately discriminate the progressive brain changes due to AD pathology from the baseline ID in DS and perhaps identify cognitive measures sensitive to early decline related to AD pathology in the context of DS-related ID (4).

Key AD Biomarkers in DS

Given the pivotal role of Aβ and tau in AD pathogenesis, it is not surprising that the main biomarkers that have been developed measure amyloid, tau and markers of neurodegeneration. Amyloid PET imaging has been performed using various tracers in adults with DS over the past decade (5–8). Levels of brain amyloid on PET are observed to increase dramatically in people with DS over age 40, mirroring the pathological finding of the universal presence of plaques seen at autopsy (9). Recent imaging studies have demonstrated that amyloid brain accumulation in DS begins in the striatum (10) which is similar to individuals with ADAD (8). Rates of accumulation of amyloid appear to be similar to those observed in the sporadic population with a substantial interval (15–20 years) between elevated brain amyloid and onset of cognitive symptoms (11). This decades-long period defines the ‘preclinical stage’ of AD and is a key target for intervention and allows for secondary prevention, before significant pathology has developed or clinical symptoms have become evident (12, 13).

In DS, the relationship between regional neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and atrophy has been well-established with post-mortem studies, as has the correlation of NFTs and cognitive decline (14). By using the PET tracer 18F-AV-1451, regional accumulation of NFTs in DS has been studied, and as seen in other neurodegenerative diseases, the distribution of tau pathology in DS is greatest in areas with atrophy on MRI, involving the medial temporal lobes and spreading posteriorly into the parietal lobes (15). Moreover, it appears that lower cognitive scores correlate with increased tau pathology just as has been reported in LOAD (15).

Changes in regional glucose metabolism, a measure of neuronal activity have been shown to be associated with cognitive decline in people with DS (16). Interestingly, individuals with DS who are not demented show a pattern of hypometabolism within the posterior cingulate-precuneus, a region which is typically observed as hypometabolic in LOAD (4). There also seems to be an inverse relationship between amyloid accumulation and regional glucose metabolism [6] as well as an inverse relationship between tau pathology and regional glucose metabolism (15). Both of these observations support the notion that biomarkers of DSAD are indeed behaving similarly to the other forms of AD: ADAD and LOAD.

Postmortem studies indicate that, although the brains of individuals with DS are typically smaller than age-matched individuals in the general population, a pattern of atrophy involving the medial temporal lobes is observed in the early stages of DSAD that also seems to correlate with declines in specific memory measures (17). Brain atrophy is considered a late manifestation of AD and reflects extensive neurodegeneration but remains an important AD biomarker and again illustrates similarities between DSAD, LOAD and ADAD.

Perhaps one of the most exciting developments in the field of AD biomarkers has been advances in blood-based biomarkers. Individuals with DS have higher plasma Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 concentrations compared with individuals without DS (18). And in CSF, elevated levels of Aβ42 are seen early in life, but with age Aβ42 levels decline (owing to their deposition into plaques) while tau levels progressively increase (18). Recent work on CSF and plasma levels of neurofilament light (NfL), a component of the axonal cytoskeleton and marker of neuronal damage and degeneration, has shown strong correlation with cognitive status in adults with DS (19). Specifically, plasma NfL levels appear to increase with age and can distinguish between normal aging in DS and AD (19, 20). Plasma NfL levels have also been shown to correlate with standard biomarkers of AD pathology and markers of neurodegeneration as well as cognitive and functional decline (21).

Despite recent advances in our understanding of AD biomarkers in DS, many questions remain. For example, which cognitive outcome measures will reflect clinical meaningfulness? Will the A/T(N) classification framework apply to DSAD and provide any diagnostic or prognostic value? How early in the course AD should we intervene and for how long should we treat? Should we consider early prevention trials prior to the appearance of AD-related neuropathology (e.g. anti-amyloid therapy for individuals with DS younger than 35 years of age)? How well will anti-amyloid therapies, currently under evaluation for ADAD and LOAD, be tolerated in persons with DS? At what stage of DSAD should anti-tau therapeutics be evaluated? How will regulatory agencies view AD in DS, in terms of an indication?

Ongoing Efforts

The landmark ABC-DS is setting the stage for powering clinical trials for DSAD. This observational study launched in 2015, is examining the progression of AD-related biomarkers (Aβ-, tau- and FDG-PET, MRI, cerebrospinal fluid plasma biomarkers and neuropathology) as well as cognitive and functional measures in over 400 adults with DS (22). The data from ABC-DS will enable secondary prevention trials for DSAD by anchoring standard AD biomarkers with cognitive and clinical outcomes in people with DS.

In addition, the Horizon 21 Down Syndrome Consortium in Europe is ongoing, and comprised of various existing DS cohorts from the UK (the London Down Syndrome Consortium [LonDownS] and the Cambridge Dementia in Down’s Syndrome [DiDS] cohort), Netherlands (the Rotterdam Down syndrome study), Germany (AD21 study group, Munich), France (TriAL21 for Lejeune Institute, Paris), and Spain (the Down Alzheimer Barcelona Neuroimaging Initiative (DABNI). This large consortium is collecting longitudinal data on AD-related cognitive and clinical changes along with standard AD biomarkers in over 1,000 participants with DS (23).

The NIH-funded Alzheimer’s Clinical Trial Consortium - Down Syndrome (ACTC-DS) was launched in 2018 to serve as a platform for conducting clinical trials to treat and prevent AD dementia in people with DS. ACTC-DS leverages the infrastructure of the NIA’s Alzheimer Clinical Trial Consortium (ACTC) in order to conduct trials across an international network of sites with expertise in DSAD, including many ABC-DS and Horizon 21performance sites. The first project to be conducted by ACTC-DS is the Trial Ready-Cohort - Down syndrome (TRC-DS), which will enroll 120 nondemented participants with DS into a longitudinal safety-run in study using MRI, amyloid PET, cognitive testing, and fluid biomarkers in preparation for upcoming randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials for DSAD. TRC-DS will allow participants who are medically stable, well-characterized and interested in participating in clinical trials to enroll into a phase II clinical trial of an anti-amyloid therapeutic. Additional therapeutic strategies under consideration for future trials include anti-tau immunotherapy and down-regulation of APP using anti-sense oligonucleotides.

Conclusions

Major advances have been made over the past decade in understanding DSAD by utilizing the latest AD biomarkers such as brain imaging and biofluid assays. Indeed, several research groups from around the world have shown that there exist remarkable similarities between DSAD, ADAD and LOAD. The ABC-DS and Horizon 21 projects are setting the stage for conducting secondary prevention trials for DSAD, while ACTC-DS will employ this knowledge and expertise to test the latest and most promising therapeutics for AD in people with DS.

Funding:

MSR was funded by NIH R61AG066543-01.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: MSR is a consultant to AC Immune.

References

- 1.Mann DM, Yates PO, Marcyniuk B. Alzheimer’s presenile dementia, senile dementia of Alzheimer type and Down’s syndrome in middle age form an age related continuum of pathological changes. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1984. May-Jun;10(3):185–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lott IT, Head E. Dementia in Down syndrome: unique insights for Alzheimer disease research. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(3):135–147. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0132-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran JA, Rafii MS, Keller SM, et al. The National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices consensus recommendations for the evaluation and management of dementia in adults with intellectual disabilities. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(8):831–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthews DC, Lukic AS, Andrews RD, et al. Dissociation of Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease effects with imaging. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2016;2(2):69–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Handen BL, Cohen AD, Channamalappa U, Bulova P, Cannon SA, Cohen WI, Mathis CA, Price JC, Klunk WE. Imaging brain amyloid in nondemented young adults with Down syndrome using Pittsburgh compound B. Alzheimers Dement. 2012. November;8(6):496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rafii MS, Wishnek H, Brewer JB, Donohue MC, Ness S, Mobley WC, Aisen PS, Rissman RA. The down syndrome biomarker initiative (DSBI) pilot: proof of concept for deep phenotyping of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in down syndrome. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015. September 14;9:239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jennings D, Seibyl J, Sabbagh M, Lai F, Hopkins W, Bullich S, Gimenez M, Reininger C, Putz B, Stephens A, Catafau AM, Marek K. Age dependence of brain β-amyloid deposition in Down syndrome: An [18F]florbetaben PET study. Neurology. 2015. February 3;84(5):500–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Annus T, Wilson LR, Hong YT, Acosta-Cabronero J, Fryer TD, Cardenas-Blanco A, Smith R, Boros I, Coles JP, Aigbirhio FI, Menon DK, Zaman SH, Nestor PJ, Holland AJ. The pattern of amyloid accumulation in the brains of adults with Down syndrome. Alzheimers Dement. 2016. May;12(5):538–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lao PJ, Betthauser TJ, Hillmer AT, Price JC, Klunk WE, Mihaila I, Higgins AT, Bulova PD, Hartley SL, Hardison R, Tumuluru RV, Murali D, Mathis CA, Cohen AD, Barnhart TE, Devenny DA, Mailick MR, Johnson SC, Handen BL, Christian BT. The effects of normal aging on amyloid-β deposition in nondemented adults with Down syndrome as imaged by carbon 11-labeled Pittsburgh compound B. Alzheimers Dement. 2016. April;12(4):380–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen AD, McDade E, Christian B, Price J, Mathis C, Klunk W, Handen BL. Early striatal amyloid deposition distinguishes Down syndrome and autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease from late-onset amyloid deposition. Alzheimers Dement. 2018. June;14(6):743–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lao PJ, Handen BL, Betthauser TJ, Mihaila I, Hartley SL, Cohen AD, Tudorascu DL, Bulova PD, Lopresti BJ, Tumuluru RV, Murali D, Mathis CA, Barnhart TE, Stone CK, Price JC, Devenny DA, Mailick MR, Klunk WE, Johnson SC, Christian BT. Longitudinal changes in amyloid positron emission tomography and volumetric magnetic resonance imaging in the nondemented Down syndrome population. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2017. May 23;9:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sperling RA, Jack CR Jr., Aisen PS. Testing the right target and right drug at the right stage. Sci. Transl. Med 2011:3:111–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margallo-Lana ML, Moore PB, Kay DW, et al. Fifteen-year follow-up of 92 hospitalized adults with Down’s syndrome: incidence of cognitive decline, its relationship to age and neuropathology. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2007;51(Pt. 6):463–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rafii MS, Lukic AS, Andrews RD, Brewer J, Rissman RA, Strother SC, Wernick MN, Pennington C, Mobley WC, Ness S, Matthews DC; Down Syndrome Biomarker Initiative and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. PET Imaging of Tau Pathology and Relationship to Amyloid, Longitudinal MRI, and Cognitive Change in Down Syndrome: Results from the Down Syndrome Biomarker Initiative (DSBI). J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;60(2):439–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haier RJ, Head K, Head E, Lott IT. Neuroimaging of individuals with Down’s syndrome at-risk for dementia: evidence for possible compensatory events. Neuroimage. 2008;39(3):1324–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hof PR, Bouras C, Perl DP, Sparks DL, Mehta N, Morrison JH. Age-related distribution of neuropathologic changes in the cerebral cortex of patients with Down’s syndrome. Quantitative regional analysis and comparison with Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(4):379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fortea J, Carmona-Iragui M, Benejam B, Fernandez S, Videla L, Barroeta I, et al. Plasma and CSF biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in adults with Down syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(10):860–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strydom A, Heslegrave A, Startin CM, et al. Neurofilament light as a blood biomarker for neurodegeneration in Down syndrome. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rafii MS, Donohue MC, Matthews DC, Muranevici G, Ness S, O’Bryant SE, et al. Plasma Neurofilament Light and Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers in Down Syndrome: Results from the Down Syndrome Biomarker Initiative (DSBI). J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;70(1):131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Handen BL. The Search for Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease in Down Syndrome. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2020;125(2):97–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strydom A, Coppus A, Blesa R, et al. Alzheimer’s disease in Down syndrome: An overlooked population for prevention trials. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2018;4:703–713. Published 2018 Dec 13. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]