Abstract

Objective

To update primary care providers practising well-child and well-baby clinical care on the evidence that contributed to the recommendations of the 2020 edition of the Rourke Baby Record (RBR).

Quality of evidence

Pediatric preventive care literature was searched from June 2016 to May 2019, primary research studies were reviewed and critically appraised using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodology, and recommendations were updated where there was support from the literature.

Main message

Notable changes in the 2020 edition of the RBR include the recommendations to limit or avoid consumption of highly processed foods high in dietary sodium, to ensure safe sleep (healthy infants should sleep on their backs and on a firm surface for every sleep, and should sleep in a crib, cradle, or bassinette in the parents’ room for the first 6 months of life), to not swaddle infants after they attempt to roll, to inquire about food insecurity, to encourage parents to read and sing to infants and children, to limit screen time for children younger than 2 years of age (although it is accepted for videocalling), to educate parents on risks and harms associated with e-cigarettes and cannabis, to avoid pesticide use, to wash all fruits and vegetables that cannot be peeled, to be aware of the new Canadian Caries Risk Assessment Tool, to note new red flags for cerebral palsy and neurodevelopmental problems, and to pay attention to updated high-risk groups for lead and anemia screening.

Conclusion

The RBR endeavours to guide clinicians in providing evidence-informed primary care to Canadian children. The revisions are rigorously considered and are based on appraisal of a growing, albeit still limited, evidence base for pediatric preventive care.

Primary prevention, through primary care and public health interventions, plays a key role in preventing many of the leading causes of death and morbidity in childhood.1-5 For example, each year, more children die in Canada from injuries than any single disease.1 Motor vehicle–related deaths are the leading cause of injury in children, and numerous studies spanning several decades have demonstrated significantly reduced risk of death when children are properly restrained in car seats compared with children restrained by seat belts or unrestrained children.2,3 Primary prevention in early childhood might also reduce the risk of disease and morbidity in later adult life. A compelling case for the latter is supported by longitudinal studies that have demonstrated how cardiometabolic risk factors in childhood such as high body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, lipid level, and blood glucose level can track into adulthood, resulting in further health issues including metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and atherosclerotic disease.6,7

For the past 3 decades, primary care providers (PCPs) across Canada have used the Rourke Baby Record (RBR) to guide the provision of evidence-informed preventive care in children younger than 6 years of age.8-10 The RBR can be accessed at no cost online (www.rourkebabyrecord.ca) and is endorsed by the College of Family Physicians of Canada, the Canadian Paediatric Society, and Dietitians of Canada. The RBR knowledge translation tools for PCPs to support well-baby and well-child visits include RBR structured forms (Guides I to IV) in a printable version or embedded within electronic medical records, an immunization chart (Guide V), and a summary of supporting evidence and websites for the recommendations (Resources 1 to 4). There are supplemental resources for parents and caregivers on the RBR website. The RBR is also a teaching tool for undergraduate and postgraduate trainees across Canada, as exemplified by LearnFM, a matrix of educational resources developed by the Canadian Undergraduate Family Medicine Education Directors and supported by the College of Family Physicians of Canada.11

This current clinical review aims to highlight the updates of the 2020 RBR. Our goal is to update busy PCPs with the current evidence and recommendations included in this newest version of the RBR.

Quality of evidence

Although the number of pediatric clinical trials and studies has increased in recent years, many challenges remain in developing evidence-based recommendations for pediatric preventive care in the primary care setting.12 The number of topics reviewed by the US Preventive Services Task Force and the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC) for adults still outweigh those for children, and most pediatric recommendations are inconclusive, mainly because of the lack of high-quality evidence to support child-related preventive maneuvers.12,13 Faced with these limitations, the RBR team has continued to use multiple sources to incorporate the best available evidence and expert consensus into the updated recommendations, with a predilection for studies applicable to the Canadian context.

As with previous updates, the 2020 RBR is guided by the AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II; www.agreetrust.org) framework.14 In addition, we engaged in a new partnership with the McMaster Evidence Review and Synthesis Team (MERST) to help streamline our literature review methods. The MERST has previously supported the work of other official bodies that produce guidelines, such as the CTFPHC.15 To update existing or integrate new recommendations into the 2020 RBR, we reviewed the latest evidence in the areas of growth monitoring, nutrition, education and advice (including injury prevention, behaviour and family issues, environmental health, and other issues), developmental surveillance, physical examination, investigations and screening, and immunization. We searched the literature from June 2016 (the last RBR literature update) to May 2019 using previously described methods.9,10 We developed new search strategies for issues pertinent to early childhood health and primary care that have emerged since the last version of the RBR in 2017 (eg, e-cigarettes). We used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodology to critically evaluate primary research studies.16 Based on new evidence, policy statements, and reviews, we modified or added recommendations using our longstanding and user-friendly categorization system of good, fair, and consensus or inconclusive evidence, which are represented in bold, italics, and regular fonts in the RBR tools, respectively.

The core 2020 RBR team initially included an FP (L.R.), a pediatrician (D.L.), a pediatric clinical epidemiologist (P.L.), and research assistants (S.A. and E.T.) who were involved in the literature search, evidence appraisal, and final recommendations. The MERST assisted with organizing and screening the literature using DistillerSR (https://www.evidencepartners.com/products/distillersr-systematic-review-software). In 2019, the team expanded to include further expertise in the clinical practice of family medicine (I.B. and B.K.) and pediatrics (A.R.L.). All of the latter members took part in reviewing pertinent evidence associated with the final recommendations and the knowledge translation tools associated with the final 2020 RBR. A team member (J.R.) has been continuously involved since the original development of the RBR and currently has an oversight role that includes publication input, review, and approval. Our team of stakeholders and advisory members from the College of Family Physicians of Canada, the Canadian Paediatric Society, and Dietitians of Canada reviewed, approved, and endorsed the final 2020 RBR. Furthermore, we created and collaborated with a users’ committee to ensure that the updated evidence was relevant, optimally incorporated, and accessible in the tools. The content of the 2020 RBR was finalized before the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, and hence does not include literature or specific recommendations that might relate to COVID-19 and well-child care.

Main message

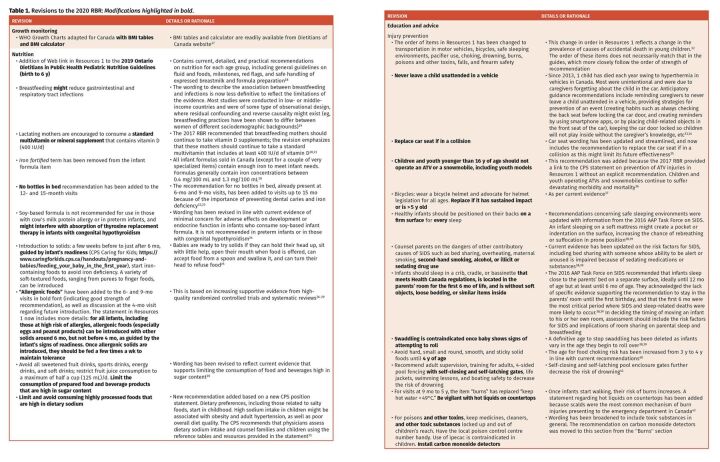

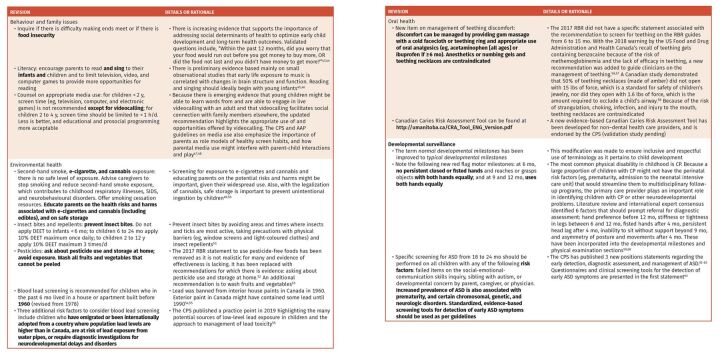

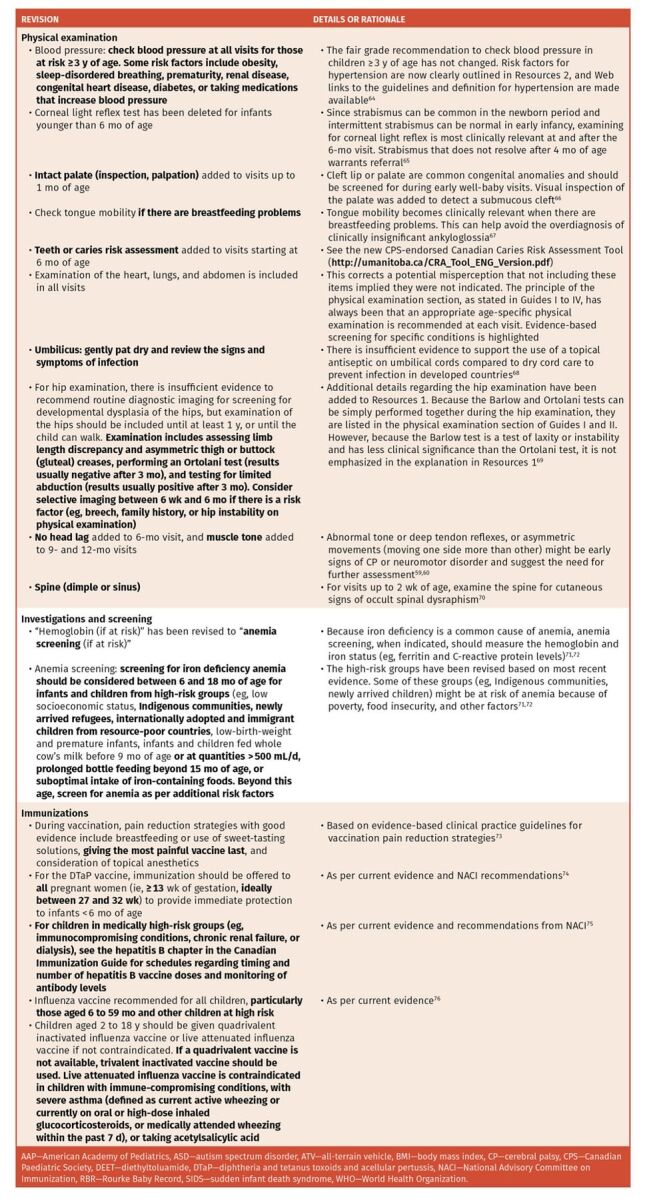

The main content revisions in the 2020 edition of the RBR are outlined below. Table 1 provides the accompanying details and rationale for the changes.17-76 The RBR website includes a version of the 2020 RBR with wording revisions in teal print for easy identification of the changes, as well as a list of the revisions (www.rourkebabyrecord.ca/updates).

Table 1.

Revisions to the 2020 RBR: Modifications highlighted in bold.

General principles

If a baby did not have a visit in the first month of life, it might be important to perform items that are typically part of the early visits, such as femoral pulse, palate, and spine and back examinations, whenever the initial assessment ultimately occurs, since these items are not performed again in later visits. This is particularly relevant if the infant was previously seen by another health care professional, or assessed via virtual care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some items on the RBR are repeated at several visits. The PCP might elect to readdress items previously discussed where they perceive a risk or need.

The order of items in some sections has been revised. In the “Nutrition” and in the “Education and Advice” sections, we have attempted to list items in order of strength of recommendation: items with good evidence appear first, followed by items with fair evidence, and items with inconclusive evidence or consensus appear last. Where possible, physical examination items have been organized from head to toe, taking into consideration the strength of recommendation.

Web links have been revised as per current evidence. They are identified on Resources 1 through 4 with the title or topic followed by the reference organization or journal. There are links on the RBR website for easy accessibility.

A new landscape paper format has a larger font size and more writing space, enabling a double-sided, 3-visits-per-page format. This is similar to the pre-existing “stretched” version that stretches each guide vertically. The original 3 visits per page format is now available as a fillable PDF.

Growth monitoring. Since calculation of BMI is recommended for children older than 2 years of age, there is now a link to Dietitians of Canada BMI tables and calculator resources.17 Body mass index curves are available through the link for growth chart sets.

Nutrition. Several practical online resources for nutrition in children younger than 6 years of age have been added to Resources 1, including guidelines from the Ontario Dietitians in Public Health18 and the Baby-Friendly Initiative Strategy for Ontario,77 and statements from the Canadian Paediatric Society on timing of allergenic food introduction26 and dietary sodium.31 Content changes related to nutrition include the following: some qualification of the association between breastfeeding and gastrointestinal and respiratory infections to reflect the limitations of the evidence19; wording to emphasize that lactating mothers should continue a standard multivitamin supplement with at least 400 IU per day of vitamin D20,21; removal of the words “iron fortified” to describe recommended infant formulas18; repeated advice at 12- and 15-month visits against bottles in bed22,23; advice against using soy-based infant formula in preterm infants and in those with cow’s milk protein allergy, and to use caution in infants being monitored for congenital hypothyroidism24; advice that introduction of solids should be guided by infant readiness, and should start between 4 and 6 months of age25; addition of good strength of recommendation evidence (bold font) for introducing allergenic foods (especially eggs and peanut products) in infants at high risk of allergies, and for maintaining tolerance by continuing those foods several times a week26-29; and advice to limit the consumption of foods (in addition to beverages) high in sugar30 and to limit consumption of highly processed foods high in dietary sodium.31

Education and advice

Injury prevention: The list of preventable injuries in Resources 1 has been placed in order from most to least prevalent cause of accidental death in young children.32 Updates include the following advice: never leave a child unattended in a vehicle33,34; replace any car seat involved in a collision35 and any bicycle helmet if it has sustained an impact or is more than 5 years old37; children and youth younger than 16 years of age should not operate an all-terrain vehicle or a snowmobile, including youth models36; healthy infants should be positioned on their backs on a firm surface for every sleep; avoid use of alcohol or illicit or sedating drugs, as they are risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome; do not swaddle infants once they show signs of attempting to roll38,39; do not introduce solid and sticky foods until 4 years of age because of choking risk (revised from 3 years of age)40; pool fencing should include self-closing and self-latching gates41; and be vigilant with hot liquids on countertops because of the risk of burns.42

Behaviour and family issues: Revised items include validated poverty identification questions about food security,43,44 and advice that both reading and singing should begin with young infants45,46; screen time should be optimally managed by children, parents, and caregivers; and videocalling can improve communication with family and friends.47,48

Environmental health items: Updated items include revised wording to educate parents on the health risks and harms associated with e-cigarettes and cannabis (including edibles) and on their safe storage49,50; advice on how to prevent insect bites51; omission of recommendation for using pesticide-free foods; recommendation to ask about pesticide use and storage at home52; suggestion to wash all fruits and vegetables that cannot be peeled53; and a list of changed and expanded risk factors for blood lead screening.54,55

Oral health: Management of teething discomfort has been added56-58 in addition to the Smiles for Life curriculum for non–dental health professionals (https://www.smilesforlifeoralhealth.org). There is a new Canadian Paediatric Society–endorsed Canadian Caries Risk Assessment Tool (http://umanitoba.ca/CRA_Tool_ENG_Version.pdf).

Developmental surveillance. Revisions regarding specific developmental milestones have been made, including changing the term normal developmental milestones to typical developmental milestones, and expanding motor milestones for early detection of cerebral palsy.59,60 The evidence and full list of associated publications supporting this recommendation on cerebral palsy is available at https://www.childhooddisability.ca/early-detection-of-cp/.

Additional risk factors have been added for autism spectrum disorder, as well as new standardized evidence-based screening tools for autism spectrum disorder detection, assessment, and management.61-63

Physical examination. Examination of the heart, lungs, and abdomen is now included in all visits. This corrects a misperception that not including these items implied they were not indicated. The principle of the physical examination section, as stated on this heading in Guides I to IV, has always been that an appropriate age-specific physical examination is recommended at each visit. Evidence-based screening for specific conditions is highlighted.

Other revised maneuvers include listing risk factors for elevated blood pressure in children older than 3 years of age64; deleting corneal light reflex from the examination of infants younger than 6 months of age65; examining for intact palate66; examining for tongue mobility only if there are breastfeeding problems67; outlining umbilical cord care68; detailing hip assessment and consideration of selective imaging69; expanding muscle tone and motor maneuvers59,60; and examining the back and spine at 1- and 2-week visits.70

Investigations and screening. Anemia screening has been revised to reflect the high-risk groups for iron deficiency anemia based on current evidence.71,72

Immunizations. Guide V and Resources 3 have been updated with the latest recommendations from the National Advisory Committee on Immunization. Changes in this edition of the RBR include the recommendation to give the most painful vaccine last as an additional pain reduction strategy,73 and revisions to recommendations for diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis,74 hepatitis B,75 and influenza vaccines.76

Conclusion

The 2020 edition of the RBR continues its tradition of updating its recommendations for the preventive care of infants and young children based on new evidence. We have increased the rigour of our process of evidence review and appraisal with new partnerships for this 2020 edition. In outlining the rationale and evidence underlying the updates and changes in the RBR recommendations in this article, we hope to help educate clinicians who provide primary care to children on best practices.

In the future, the RBR group is planning an end-user (clinicians and parents) satisfaction evaluation with the RBR guides and resources. This feedback would direct further development to optimize the usability, accessibility, and effectiveness of the tools.

Finally, primary care has dramatically changed since the COVID-19 pandemic onset, with increased reliance on virtual, as opposed to in-person, visits. We will seek ways to support PCPs with the implementation of the RBR within the challenging and shifting landscape of current health care delivery to ensure that infants and children continue to receive high-quality primary care.

Editor’s key points

▸ The 2020 edition of the Rourke Baby Record (RBR) is an update of the 2017 edition and provides updated recommendations for the primary care of children younger than 6 years of age. The knowledge translation tools and supporting literature are available at www.rourkebabyrecord.ca.

▸ Important revisions include the recommendations to limit or avoid consumption of highly processed foods high in dietary sodium, to ensure safe sleep (healthy infants should sleep on their backs and on a firm surface for every sleep, and should sleep in a crib, cradle, or bassinette in the parents’ room for the first 6 months of life), to not swaddle infants after they attempt to roll, to inquire about food insecurity, to encourage parents to read and sing to infants and children, to limit screen time for children younger than 2 years of age (although it is accepted for videocalling), to educate parents on risks and harms associated with e-cigarettes and cannabis, to avoid pesticide use, to wash all fruits and vegetables that cannot be peeled, to be aware of the new Canadian Caries Risk Assessment Tool, to note new red flags for cerebral palsy and neurodevelopmental problems, and to pay attention to updated high-risk groups for lead and anemia screening.

▸ The 2020 edition of the RBR was completed before the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, and thus does not include recommendations regarding virtual care. The RBR will continue to find ways to support primary care providers within the shifting landscape of health care delivery.

Footnotes

Contributors

All authors contributed to the literature review and interpretation, and to the development of the 2020 Rourke Baby Record. Drs Li, L. Rourke, and Rowan-Legg drafted the article. All authors contributed to editing and reviewing the drafts, and approved the final submission.

Competing interests

The Government of Ontario provides annual funding to support the updating and development of the Rourke Baby Record (RBR); funding is administered through McMaster University. For the fiscal year ending March 31, 2020, a total of $63 000 was provided; of this, approximately $19 000 was used for honoraria, which was divided among some of the authors of this manuscript. The licensing fee for electronic medical record use of the RBR (for electronic medical record firms not licensed in Ontario) goes to the Memorial University of Newfoundland Rourke Baby Record Development Fund. No royalties are received for the RBR, and there are no honoraria from commercial interests. In-kind support comes from Memorial University of Newfoundland and the 3 endorsing organizations: the Canadian Paediatric Society, the College of Family Physicians of Canada, and Dietitians of Canada. Dr Li is funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Salary Award.

This article is eligible for Mainpro+ certified Self-Learning credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro+ link.

This article has been peer reviewed.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro de juillet 2021 à la page e157.

References

- 1.Yanchar NL, Warda LJ, Fuselli P.. Child and youth injury prevention: a public health approach. Paediatr Child Health 2012;17(9):511-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams SB, Whitlock EP, Edgerton EA, Smith PR, Beil TL; US Preventive Services Task Force . Counseling about proper use of motor vehicle occupant restraints and avoidance of alcohol use while driving: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2007;147(3):194-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durbin DR, Hoffman BD; Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention . Child passenger safety. Pediatrics 2018;142(5):e20182460. Epub 2018 Aug 30.30166368 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plachta-Danielzik S, Kehden B, Landsberg B, Schaffrath Rosario A, Kurth BM, Arnold C, et al. Attributable risks for childhood overweight: evidence for limited effectiveness of prevention. Pediatrics 2012;130(4):e865-71. Epub 2012 Sep 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuhle S, Allen AC, Veugelers PJ.. Prevention potential of risk factors for childhood overweight. Can J Public Health 2010;101(5):365-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llewellyn A, Simmonds M, Owen CG, Woolacott N.. Childhood obesity as a predictor of morbidity in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2016;17(1):56-67. Epub 2015 Oct 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, Woolacott N.. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 2016;17(2):95-107. Epub 2015 Dec 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rourke JT, Rourke LL.. Well baby visits: screening and health promotion. Can Fam Physician 1985;31:997-1002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li P, Rourke L, Leduc D, Arulthas S, Rezk K, Rourke J.. Rourke Baby Record 2017. Clinical update for preventive care of children up to 5 years of age. Can Fam Physician 2019;65:183-91 (Eng), e99-109 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riverin B, Li P, Rourke L, Leduc D, Rourke J.. Rourke Baby Record 2014. Evidence-based tool for the health of infants and children from birth to age 5. Can Fam Physician 2015;61:949-55 (Eng), e491-8 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keegan DA, Scott I, Sylvester M, Tan A, Horrey K, Weston WW.Shared Canadian Curriculum in Family Medicine (SHARC-FM) . Creating a national consensus on relevant and practical training for medical students. Can Fam Physician 2017;63:e223-31. Available from: https://www.cfp.ca/content/cfp/63/4/e223.full.pdf. Accessed 2021 Jun 14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melnyk BM, Grossman DC, Chou R, Mabry-Hernandez I, Nicholson W, DeWitt TG, et al. USPSTF perspective on evidence-based preventive recommendations for children. Pediatrics 2012;130(2):e399-407. Epub 2012 Jul 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care . Published guidelines. Calgary, AB: Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care; 2019. Available from: https://canadiantaskforce.ca/guidelines/published-guidelines/. Accessed 2020 Jul 29. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brouwers MC, Kerkvliet K, Spithoff K; AGREE Next Steps Consortium . The AGREE Reporting Checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 2016;352:i1152. Erratum in: BMJ 2016;354:i4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warren R, Kenny M, Bennett T, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Ali MU, Sherifali D, et al. Screening for developmental delay among children aged 1-4 years: a systematic review. CMAJ Open 2016;4(1):E20-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64(4):383-94. Epub 2010 Dec 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dietitians of Canada . WHO growth charts for Canada. Toronto, ON: Dietitians of Canada; 2019. Available from: https://www.dietitians.ca/Secondary-Pages/Public/Who-Growth-Charts.aspx. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aqui C, Atkinson L, Cardinal M, Loewenberger E, Morgan R.. Pediatric nutrition guidelines (birth to six years) for health professionals. Ontario Dietitians in Public Health; 2019. Available from: https://www.odph.ca/upload/membership/document/2019-06/york-9367224-v2-2019-finalized-odph-pediatric-nutrition-guidelines.pdf. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horta BL, Victora CG.. Short term effects of breastfeeding: a systematic review on the benefits of breastfeeding on diarrhoea and pneumonia mortality. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/95585/9789241506120_eng.pdf;jsessionid=48A19BDB8BE508E378778B2C9979A81A?sequence=1. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health Canada . Vitamin D and calcium: updated dietary reference intakes. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2020. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/healthy-eating/vitamins-minerals/vitamin-calcium-updated-dietary-reference-intakes-nutrition.html. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godel JC; Canadian Paediatric Society, First Nations, Inuit and Métis Health Committee . Vitamin D supplementation: recommendations for Canadian mothers and infants. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(7):583-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Health Canada, Canadian Paediatric Society, Dietitians of Canada, Breastfeeding Committee for Canada . Nutrition for healthy term infants: recommendations from six to 24 months. A joint statement of Health Canada, Canadian Paediatric Society, Dietitians of Canada, and Breastfeeding Committee for Canada. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2014. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canada-food-guide/resources/infant-feeding/nutrition-healthy-term-infants-recommendations-birth-six-months/6-24-months.html#. Accessed 2020 May 25. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parkin PC, Maguire JL.. Iron deficiency in early childhood. CMAJ 2013;185(14):1237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhatia J, Greer F; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition . Use of soy protein-based formulas in infant feeding. Pediatrics 2008;121(5):1062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caring for Kids . Feeding your baby in the first year. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Paediatric Society; 2020. Available from: https://www.caringforkids.cps.ca/handouts/feeding_your_baby_in_the_first_year. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abrams EM, Hildebrand K, Blair B, Chan ES.. Timing of introduction of allergenic solids for infants at high risk. Paediatr Child Health 2019;24(1):56-7. Epub 2019 Feb 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ierodiakonou D, Garcia-Larsen V, Logan A, Groome A, Cunha S, Chivinge J, et al. Timing of allergenic food introduction to the infant diet and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016;316(11):1181-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Natsume O, Kabashima S, Nakazato J, Yamamoto-Hanada K, Narita M, Kondo M, et al. Two-step egg introduction for prevention of egg allergy in high-risk infants with eczema (PETIT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389(10066):276-86. Epub 2016 Dec 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, Plaut M, Bahnson HT, Mitchell H, et al. Identifying infants at high risk of peanut allergy: the Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP) screening study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;131(1):135-43.E12. Epub 2012 Nov 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pound CM, Critch JN, Thiessen P, Blair B; Canadian Paediatric Society Nutrition and Gastroenterology Committee . A proposal to increase taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Paediatric Society; 2020. Available from: https://www.cps.ca/en/documents/position/tax-on-sugar-sweetened-beverages. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gowrishankar M, Blair B, Rieder MJ.. Dietary intake of sodium by children: why it matters. Paediatr Child Health 2020;25(1):47-61. Epub 2020 Feb 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yao X, Skinner R, McFaull S, Thompson W.. At-a-glance—2015 injury deaths in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2019;39(6-7):225-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho K, Minhas R, Young E, Sgro M, Huber JF.. Paediatric hyperthermia-related deaths while entrapped and unattended inside vehicles: the Canadian experience and anticipatory guidance for prevention. Paediatr Child Health 2020;25(3):143-8. Epub 2019 Jul 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Healthychildren.org . Prevent child deaths in hot cars. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2019. Available from: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/safety-prevention/on-the-go/Pages/Prevent-Child-Deaths-in-Hot-Cars.aspx. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Transport Canada . Choosing a child car seat or booster seat. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2019. Available from: https://tc.canada.ca/en/road-transportation/child-car-seat-safety/choosing-child-car-seat-booster-seat. Accessed 2021 May 25. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yanchar NL. Preventing injuries from all-terrain vehicles. Paediatr Child Health 2012;17(9):513-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.United States Consumer Product Safety Commission . Which helmet for which activity? Bethesda, MD: United States Consumer Product Safety Commission; 2014. Available from: https://www.cpsc.gov/safety-education/safety-guides/sports-fitness-and-recreation-bicycles/which-helmet-which-activity. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome . SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: updated 2016 recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics 2016;138(5):e20162938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moon RY; Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome . SIDS and other sleeprelated infant deaths: evidence base for 2016 updated recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics 2016;138(5):e20162940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cyr C; Canadian Paediatric Society Injury Prevention Committee . Preventing choking and suffocation in children. Paediatr Child Health 2012;17(2):91-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Denny SA, Quan L, Gilchrist J, McCallin T, Shenoi R, Yusuf S, et al. Prevention of drowning. Pediatrics 2019;143(5):e20190850. Epub 2019 Mar 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crain J, McFaull S, Rao DP, Do MT, Thompson W.. At-a-glance. Emergency department surveillance of thermal burns and scalds, electronic Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program, 2013. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2017;37(1):30-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, Coleman SM, Heeren T, Rose-Jacobs R, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics 2010;126(1):e26-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fazalullasha F, Taras J, Morinis J, Levin L, Karmali K, Neilson B, et al. From office tools to community supports: the need for infrastructure to address the social determinants of health in paediatric practice. Paediatr Child Health 2014;19(4):195-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shaw A; Canadian Paediatric Society Community Paediatrics Commitee . Read, speak, sing: promoting early literacy in the health care setting. Paediatr Child Health 2021;26(3):182-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernandez S. Music and brain development. Pediatr Ann 2018;47(8):e306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Canadian Paediatric Society; Digital Health Task Force . Screen time and young children: promoting health and development in a digital world. Paediatr Child Health 2017;22(8):461-77. Epub 2017 Oct 9. Erratum in: Paediatr Child Health 2018;23(1):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Communications and Media . Media and young minds. Pediatrics 2016;138(5):e20162591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grant CN, Bélanger RE.. Cannabis and Canada’s children and youth. Paediatr Child Health 2017;22(2):98-102. Epub 2017 May 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stanwick R. E-cigarettes: are we renormalizing public smoking? Reversing five decades of tobacco control and revitalizing nicotine dependency in children and youth in Canada. Paediatr Child Health 2015;20(2):101-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Onyett H; Canadian Paediatric Society Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee . Preventing mosquito and tick bites: a Canadian update. Paediatr Child Health 2014;19(6):326-32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roberts JR, Karr CJ; Council on Environmental Health . Pesticide exposure in children. Pediatrics 2012;130(6):e1765-88. Epub 2012 Nov 26. Erratum in: Pediatrics 2013;131(5):1013-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trasande L, Shaffer RM, Sathyanarayana S; American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Environmental Health . Food additives and child health. Pediatrics 2018;142(2):e20181410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Government of Canada . Reduce your exposure to lead. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2016. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/home-garden-safety/reduce-your-exposure-lead.html. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buka I, Hervouet-Zeiber C.. Lead toxicity with a new focus: addressing low-level lead exposure in Canadian children. Paediatr Child Health 2019;24(4):293-4. Epub 2019 Jun 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Health Canada . Oragel recall (2018-05-29). Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2018. Available from: https://www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall-alert-rappel-avis/hc-sc/2018/67490r-eng.php. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]

- 57.US Food and Drug Administration . Risk of serious and potentially fatal blood disorder prompts FDA action on oral over-the-counter benzocaine products used for teething and mouth pain and prescription local anesthetics. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2018. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/risk-serious-and-potentially-fatal-blood-disorder-prompts-fda-action-oral-over-counter-benzocaine. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soudek L, McLaughlin R.. Fad over fatality? The hazards of amber teething necklaces. Paediatr Child Health 2018;23(2):106-10. Epub 2017 Nov 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boychuck Z, Andersen J, Bussières A, Fehlings D, Kirton A, Li P, et al. International expert recommendations of clinical features to prompt referral for diagnostic assessment of cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2020;62(1):89-96. Epub 2019 Apr 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Childhood Disability LINK . Early detection of cerebral palsy. Montreal, QC: Childhood Disability LINK; 2020. Available from: https://www.childhooddisability.ca/early-detection-of-cp/. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zwaigenbaum L, Brian JA, Ip A.. Early detection for autism spectrum disorder in young children. Paediatr Child Health 2019;24(7):424-43. Epub 2019 Oct 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brian JA, Zwaigenbaum L, Ip A.. Standards of diagnostic assessment for autism spectrum disorder. Paediatr Child Health 2019;24(7):444-60. Epub 2019 Oct 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ip A, Zwaigenbaum L, Brian JA.. Post-diagnostic management and follow-up care for autism spectrum disorder. Paediatr Child Health 2019;24(7):461-77. Epub 2019 Oct 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, Blowey D, Carroll AE, Daniels SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2017;140(3):e20171904. Epub 2017 Aug 21. Errata in: Pediatrics 2017;140(6):e20173035, Pediatrics 2018;142(3):e20181739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Donahue SP, Baker CN; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Ophthalmology, American Association of Certified Orthoptists, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus . Procedures for the evaluation of the visual system by pediatricians. Pediatrics 2016;137(1):e20153597. Epub 2015 Dec 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lewis CW, Jacob LS, Lehmann CU; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Oral Health . The primary care pediatrician and the care of children with cleft lip and/or cleft palate. Pediatrics 2017;139(5):e20170628. Erratum in: Pediatrics 2017;140(3):e20171921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rowan-Legg A. Ankyloglossia and breastfeeding. Paediatr Child Health 2015;20(4):209-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Imdad A, Bautista RM, Senen KA, Uy ME, Mantaring JB 3rd, Bhutta ZA.. Umbilical cord antiseptics for preventing sepsis and death among newborns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(5):CD008635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shaw BA, Segal LS; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Orthopaedics . Evaluation and referral for developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants. Pediatrics 2016;138(6):e20163107. Epub 2016 Nov 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dias M, Partington M; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Neurologic Surgery . Congenital brain and spinal cord malformations and their associated cutaneous markers. Pediatrics 2015;136(4):e1105-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Unger SL, Fenton TR, Jetty R, Critch JN, O’connor DL.. Iron requirements in the first 2 years of life. Paediatr Child Health 2019;24(8):555-6. Epub 2019 Dec 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baker RD, Greer FR; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition . Diagnosis and prevention of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children (0-3 years of age). Pediatrics 2010;126(5):1040-50. Epub 2010 Oct 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Taddio A, McMurtry CM, Shah V, Riddell RP, Chambers CT, Noel M, et al. Reducing pain during vaccine injections: clinical practice guideline. CMAJ 2015;187(13):975-82. Epub 2015 Aug 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brophy J, Baclic O, Tunis MC.. Summary of the NACI update on immunization in pregnancy with tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and reduced acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine. Can Commun Dis Rep 2018;44(3-4):91-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Health Canada . Hepatitis B vaccine: Canadian immunization guide. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2020. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-7-hepatitis-b-vaccine.html. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Health Canada . Canadian immunization guide chapter on influenza and statement on seasonal influenza vaccine for 2019-2020. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2019. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/vaccines-immunization/canadian-immunization-guide-statement-seasonal-influenza-vaccine-2019-2020.html. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baby-Friendly Initiative Ontario . Infant formula: what you need to know. Toronto, ON: Best Start Resource Centre; 2020. Available from: https://resources.beststart.org/product/b19e-infant-formula-booklet/. Accessed 2020 Jun 23. [Google Scholar]