Traditionally, Indigenous women commanded the highest respect in their communities as water carriers and the givers of life. They are sacred1 and powerful beings because they “birth the whole world.”2 Unfortunately, racism, sexism, and colonialism3 have disrupted respect for Indigenous peoples and women. As a result, it has perpetuated violence, including the forced and coerced sterilization of Indigenous women and girls.

Coerced sterilization refers to the practice of sterilizing Indigenous women without free and informed consent. Based on eugenics beliefs and policies, Sexual Sterilization Acts were passed in Alberta (1928 to 1972) and British Columbia (1933 to 1973) and were not repealed until the 1970s. Under the Acts, a board of eugenics could order sterilization of institutionalized patients who “if discharged without being subjected to an operation for sexual sterilization would be likely to beget or bear children who by reason of inheritance would have a tendency to serious mental disease or mental deficiency.”4

Research demonstrates that “74% of all Aboriginals presented to the Board were eventually sterilized (compared to 60% of all patients presented).”5 In her book, An Act of Genocide, Stote6 documents 580 sterilizations across Canada in Indian Hospitals between 1970 and 1975. Between 1966 and 1976, it is estimated that more than 1200 sterilizations (approximately 1150 Indigenous women, and 50 remaining men or of undocumented sex) were sterilized. From 1966 to 1976, more than 70 sterilizations were also performed on women in Nunavut.6

In October 2017, a proposed class-action lawsuit was filed in Saskatchewan from more than 100 women across Canada who reported they were forced to be or were coercively sterilized,7 thus demonstrating the lived experiences of Indigenous women.8 However, although Alisa Lombard indicated that she was contacted by approximately 100 women, not all of them were from Saskatchewan (https://sencanada.ca/en/Content/Sen/Committee/421/RIDR/54643-e). On January 28 and 29, 2020, the National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health led a gathering on “Culturally Informed Choice and Consent in Indigenous Women’s Health Services” in Ottawa, Ont. The objectives of the gathering were to address the coerced and forced sterilization of Indigenous women and girls in Canada and to explore concepts of informed choice, informed consent, and culturally safe health care practices. Attendees from across Canada discussed guidelines and actions to stop the coerced or forced sterilization of Indigenous women and girls by identifying strategies on how to change structures (organizations, standards, and regulations), systems (policies, programs, and services), and individual practices and actions.

As a speaker at the conference, I was asked to address the resiliency of Indigenous women and culture, and the strengths that Indigenous peoples, communities, and allies could build upon to address forced and coerced sterilization. While reflecting on ways to restore respect toward Indigenous women and girls as sacred and powerful water carriers and givers of life, I lit a smudge and prayed and asked for guidance and wisdom from our ancestors. When I thought about the strengths we need to build upon, I heard the voices of my great grandparents: Oma ondaas meenun obinoji. Oma meenun-aabi Ikwezance. They said, “Come here my blueberry child. Come here my blueberry-eyed little girl.” It was those words meenun obinoji (blueberry children) that reminded me that our strengths lie in our families, our cultures, our teachings, our languages, and our stories.

I would like to share a story about meenun obinoji, blueberry children. My favourite memory as a child is going blueberry picking with my sister, cousins, mom, auntie Shirley, and my nanny (grandmother) and her sisters, all 6 of my great aunts. I spent many childhood summers in Dryden and Blueberry Lake, Ont. We would camp, swim, and pick berries (and pinecones) in July to August and would sell the berries to buyers who would randomly show up on my great-grandmother’s doorstep. As we got older, we picked bottles and pinecones, but as a child, I specifically remember the berries. I would sit in one spot and pick as far as I could reach, fighting off mosquitoes and no-see-ums as they crawled up my nose and into my eyes while I shoved handfuls of berries into my mouth.

Jennifer Leason

Berry picking with my family was instrumental in shaping me into the woman, sister, daughter, and mother I am today. The “old ladies” would talk and tell us that we women, like the berries and pinecones, carry seeds inside us and that these seeds are gifts from the creator. They talked about how each and every one of us are gifted with the seeds of creation and that those seeds are a spark of the greater spirit. They taught me that because these seeds are a gift of creation, that they must be respected, honoured, and most importantly, protected. While sitting beside the women in my life and picking and cleaning berries or pinecones, and preparing and participating in ceremonies, berry tea, berry feasts, fasts, and stories from my grandmother and aunties, I listened and learned. They canned berries and reminisced about pregnancy and labour and shared their fears and hopes of being good mothers. I remember jars of canned strawberries, blueberries, and saskatoons in Nanny’s dark and scary basement cellar that were pulled out for every celebration, picnic, and ceremony.

The stories, jars of canned meenun, and berry picking with the women in my life were my education on sexual and reproductive health, our rights, and our responsibilities to our families. My aunties and sisters, as well as the berries and land, are my teachers. They instilled in me the foundation and power to be grounded and connected to a matriarchal tradition and an inherent Indigenous wisdom and knowledge. This is our Indigenous law and legal tradition that comes from the berries and land, our oldest and greatest teacher. This is a strength we can build upon.

As Indigenous communities, we have a responsibility to protect, educate, support, and empower the next generation of women and girls. This includes connecting to stories, ceremonies, and traditions as a way of building connections and empowering women and girls through Indigenous traditional matriarchal wisdom; empowering, educating, and informing women and girls who will be armed with knowledge, skills, and a voice to defend their rights and stand up for others; and providing support, mentorship, and guidance to ensure women and girls do not feel alone, disconnected, or filled with doubt.

Jennifer Leason

However, empowering and teaching Indigenous women, girls, boys, men, and families is not enough. Forced and coerced sterilization of Indigenous women is rooted in power and inequity. Maori Elder Merida Mita said, “we have a history of people putting Maori [Indigenous peoples] under a microscope in the same way a scientist looks at an insect. The ones doing the looking are giving themselves the power to define.”9 Rather than focus on Indigenous women, families, and communities under the microscope, it is time to redirect our critical gaze and put the people and structures who continue to perpetuate violence, oppression, and genocide under the microscope. The historical and perpetuated racism, sexism, discrimination, and colonial violence is embedded in our institutions, systems, structures, policies, and everyday racism. Those who have historically given themselves the power to define have also given themselves the power to impose judgment, prescription, and genocide. We must take a good hard look through the microscope; only then will we be able to head in the direction of love, respect, bravery, truth, honesty, humility, and wisdom.10

As family physicians, there are 2 calls for action: one is to create culturally safe11 and appropriate sexual and reproductive health care supports and services. Another is to address Indigenous-specific racism and discrimination in health care12 through ongoing reconciliation efforts and activities13 and by respecting the rights of Indigenous peoples.14

We all have a responsibility to protect our seeds of creation: our meenun obinoji, our blueberry children. We have a responsibility to educate and support women (and birth partners) to do what is best for them. We have a responsibility to share our matriarchal traditional teachings and inherent Indigenous wisdom. We have a responsibility to uphold the teachings and values in which we speak. We have a responsibility to speak up and speak out against violence and injustice. We have a responsibility to transform our systems and structures.

We have a responsibility to act.

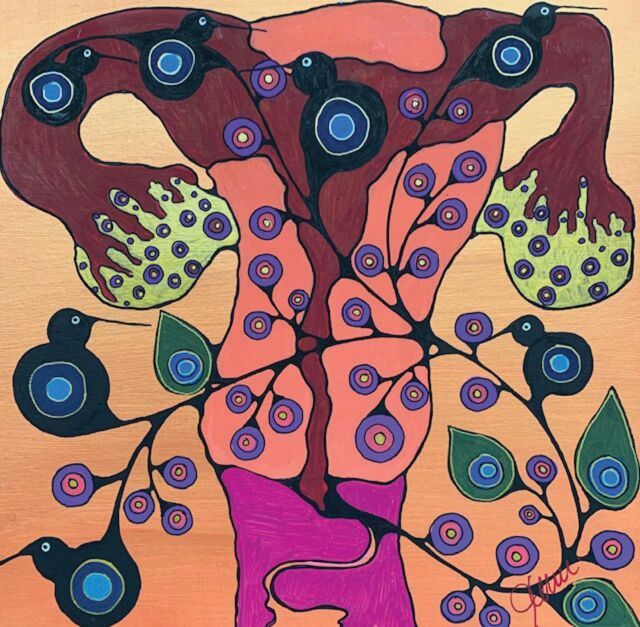

Art piece: Matriarchal Wisdom

My painting of the woman with the womb is dedicated to all women, sisters, daughters, and okitcheta-Ike: women warriors who continue to fight systemic injustices to create a better future. The woman in the painting represents all mothers who carry the seeds of creation within them. The child represents the past, present, and future of our shared humanity. The 7 leaves represent the 7 sacred teachings and values of humility, courage, wisdom, respect, love, honesty, and truth. The berries represent the seeds of creation and our responsibility to the 7 generations before and after each of us. We all have a responsibility to protect the sacredness of life. The water inside the womb represents all life and the power and sacredness of all women as water carriers. The moon is Grandmother moon and represents Indigenous matriarchal wisdom and the power of a woman’s moon time (menstruation), which is also represented by the blood and placenta inside the womb. The stars in the sky represent all the ancestors and the life force of Kitche Manidou: Creation.

Matriarchal Wisdom, Jennifer Leason

Footnotes

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Anderson K. A recognition of being: reconstructing native womanhood. Toronto, ON: Sumach Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bear S. Equality among women. Can Lit 1990;124-125:133-6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourassa C, McKay-McNabb K, Hampton M.. Racism, sexism, and colonialism: the impact on the health of Aboriginal women in Canada. In: Monture P, McGuire PD, editors. First voices: an Aboriginal women’s reader. Toronto ON: Inanna Publications and Education; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyck E. Facing eugenics: reproduction, sterilization and the politics of choice. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grekul J, Krahn A, Odynak D.. Sterilizing the “feeble-minded”: eugenics in Alberta, Canada, 1929-1972. J Hist Sociol 2004;17(4):358-358-84. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stote K. An act of genocide: colonialism and the sterilization of aboriginal women. Black Point, NS: Fernwood Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zingel A. Indigenous women come forward with accounts of forced sterilization, says lawyer. CBC News 2019. Apr 18. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/forced-sterilization-lawsuit-could-expand-1.5102981. Accessed 2021 Jun 11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyer Y, Bartlett J.. External review: tubal ligation in the Saskatoon Health Region: the lived experience of Aboriginal Women. Saskatoon, SK: Saskatchewan Health Authority; 2017. Available from: https://www.saskatoonhealthregion.ca/DocumentsInternal/Tubal_Ligation_intheSaskatoonHealthRegion_the_Lived_Experience_of_Aboriginal_Women_BoyerandBartlett_July_22_2017.pdf. Accessed 2021 Jun 11. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith LT. Decolonizing methodologies: research and Indigenous peoples. New York, NY: Zed Books Ltd; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benton-Banai E. The Mishomis book: the voice of the Ojibway. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenwood M, Lindsay N, King J, Loewen D.. Ethical spaces and places: Indigenous cultural safety in British Columbia healthcare. AlterNative 2017;13(3):179-89. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turpel-Lafond ME. In plain sight: addressing Indigenous-specific racism and discrimination in B.C. health care. Victoria, BC: Government of British Columbia; 2020. Available from: https://engage.gov.bc.ca/app/uploads/sites/613/2020/11/In-Plain-Sight-Full-Report.pdf. Accessed 2021 Jun 11. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada . Calls to action. Winnipeg, MB: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; 2015. Available from: http://trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf. Accessed 2021 Jun 11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.United Nations . United Nations declaration of the rights of Indigenous peoples. New York, NY: United Nations; 2008. Available from: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf. Accessed 2021 Jun 11. [Google Scholar]