Abstract

Background:

Continued substance use is common during opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment. There are still inconsistencies in how continued substance use and concurrent patterns of substance use among patients with OUD varies by gender. There is still more to learn regarding how factors associated with continued and concurrent use might differ for men and women in methadone maintenance treatment (MMT).

Methods:

This cross-sectional study examined predictors of concurrent substance use subgroups among patients receiving MMT. The sample included 341 (n = 161 women) MMT patients aged 18 and older from opioid treatment programs in Southern New England and the Pacific Northwest. Patients completed a survey assessing sociodemographic and clinical characteristics including past-month substance use. Latent class analyses were conducted by gender to identify groups based on substance use and determine predictors of those classes.

Results:

Three-class solutions were the optimal fit for both men and women. For both genders, the first subgroup was characterized as Unlikely Users (59.8% women, 52.8% men). Classes 2 and 3 among women were Cannabis/Opioid Users (23.7%) and Stimulant/Opioid Users (13.0%). Among men, Classes 2 and 3 consisted of Alcohol/Cannabis Users (21.9%) and Cannabis/Stimulant/Opioid Users (25.3%). Ever using Suboxone (buprenorphine/naloxone) and depression/anxiety symptoms were significantly linked to substance use group among women, whereas homelessness and employment status were significantly associated with substance use group among men.

Conclusions:

This study furthers understanding of gender differences in factors associated with continued substance use and distinctive patterns of concurrent substance use that may guide tailored treatments among patients MMT.

Keywords: opioid use disorder, methadone, gender, concurrent substance use, substance use treatment

Introduction

Problems related to opioid use and opioid use disorders (OUD) have increased substantially in recent years. In particular, between 2002 to 2013 rates of heroin use in the United States have increased by 62%, with 67.8% of overdose deaths involving opioids in 2017 (Scholl, Seth, Kariisa, Wilson, & Baldwin, 2018; Soyka, 2017). In 2016, approximately 2 million individuals have OUD associated with prescription opioids and 262,000 have OUDs related to heroin (Florence, Zhou, Luo, & Xu, 2016). The most effective treatment for OUD involves use of medication, including methadone, buprenorphine, and most recently, extended-release naltrexone, often in conjunction with counseling or therapy (CDC, 2018; Lee et al., 2014; Nielsen, Larance, & Lintzeris, 2017).

Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) has been shown to be effective for OUD outcomes including improving quality of life, general health, and abstinence from opioid use (Fei, Yee, Habil, & Bin, 2016; Kreek, Borg, Ducat, & Ray, 2010; Mattick, Breen, Kimber, Davoli, 2014). Continued use of other substances during MMT is common and is a major challenge to treatment retention and abstinence (Noysk et al., 2012; White et al., 2014). Continued use of heroin, alcohol, and cocaine, in particular, are significant factors in termination of treatment and mortality (Jimenez-Treviño et al., 2011); additionally, alcohol and cocaine use has been linked to increased use of illicit opioids among those in MMT (Davstad et al., 2007; Magura & Rosenblum, 2001; Maremmani et al., 2007; Stenbacka, Beck, Leifman, Romelsjö, & Helander, 2007). A study of 611 MMT patients found that more than half reported using at least one illicit substance with 22.3%, 36.8%, 34.9%, and 29.6% reporting misuse of prescription opioids, heroin, cocaine, and cannabis use, respectively (Glenn et al., 2016). Others have found that non-medical use of prescription opioids and benzodiazepines and use of multiple substances during treatment predict MMT attrition (White et al., 2014). Relatively little is known, however, about rates and types of concurrent substance use (i.e., two or more substances used within the same time period) among men and women in MMT. Understanding potential gender differences in these groupings would help identify risk factors to prevent relapse which may, in turn, inform more tailored and person-centered medication-assisted treatments.

Gender differences in continued substance use in MMT may partly vary depending on the substances examined. Some studies have found that men in MMT have increased risk for illicit opioid use and nonmedical use of benzodiazepines as well as higher rates of treatment attrition (White et al., 2014). Others have found that women have an increased risk of co-prescription of methadone and opioids and lower odds of sustained success in tapering methadone (Nosyk et al., 2012; Nosyk et al., 2014). Additionally, several studies have found no gender differences in continued substance use or abstinence of opioids and heroin (Bawor et al., 2015a; Levine et al., 2015; Li, Sangthong, Chongsuvivatwong, McNeil, & Li, 2011).

Less is understood about factors that are associated with concurrent substance use groupings among men and women receiving MMT. Factors that have been linked to continued substance use including sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., being unemployed, being unpartnered/unmarried), depression and anxiety symptoms, and treatment characteristics (e.g., longer treatment episodes; Bawor et al., 2015b; Kurdyak et al., 2012; Proctor et al., 2015; Rosic et al., 2017; Roux et al., 2016). Yet, there little literature examining the risk factors that may lead to continued use of substances in addition to opioids among men and women in MMT. Determining correlates of concurrent substance use groups among men and women in MMT would potentially enable targeting of additional support resources to those in greatest need.

The study builds on the literature exploring continued and concurrent substance use among men and women receiving MMT using cross-sectional data from a multi-site sample. Our first aim was to identify substance use groups among men and women in MMT. Our second aim was to consider how sociodemographic factors (e.g., homelessness, marital status), treatment characteristics (e.g., first time enrollment in MMT), and depressive and anxiety symptoms are associated with these groupings for men and women in MMT. Separate analyses were considered for men and women given that in both the general population and patients in MMT, gender differences have been shown in substance use along with its correlates and consequences (Hasin & Grant, 2015; McCabe, West, Jutkiewicz, & Boyd, 2017; Nicolai, Moshagen, & Demmel, 2016; Vigna-Taglianti et al., 2016).

Materials and Methods

Participants and setting

The sample for this cross-sectional study was recruited from four opioid treatment programs in Southern New England (n = 384) and the Pacific Northwest (n = 100) in 2017. Participants included 484 MMT patients age 18 and older. Individuals who presented for methadone dosing or group support/counseling as part of their treatment were invited by the investigators and other clinical staff to complete an anonymous self-administered paper survey that assessed patient sociodemographic and health information, substance use, psychosocial functioning, and MMT characteristics and outcomes. An informed consent document was included with each survey. Patients who were under 18 or not fluent in English were excluded. There were no significant differences in gender composition between the four recruitment sites, χ2[3] = 7.60, p = .055. Response rates were not collected due to practical difficulties related to recruitment during methadone administration. The study was approved by [blinded for review].

We removed two participants who self-identified as gender nonconforming to compare patients who identified as men and women. Of the remaining 482 patients, 141 had missing data on one or more substance use variables. The analytic sample included 341 patients with 161 women and 180 men with complete data. There were significant differences in terms of demographics between those included and excluded. Excluded patients were older (m = 44.58 vs. m = 39.75 years), t (466) = −4.07, p < .001 and consisted of more men (64.0% vs. 52.8%), χ2[1] = 4.95, p = .026. Those excluded from analyses were also had lower educational attainment, χ2[2] = 9.08, p = .011. That is, compared to included patients, more excluded individuals had completed high school or less levels of education (26.2% vs. 14.7%). Conversely, those included in the analytic sample had slightly higher rates of college education (69.8% vs. 61.0%) and graduate education (15.5% vs. 12.8%) than those excluded. Those who were included also had a greater number of individuals who were currently receiving Medicaid than those who were excluded (52.7% vs. 38.4%),, χ2[2] = 7.32, p = .007. Lastly, compared to included patients, those excluded consisted of more first time enrollees in MMT (57.8% vs. 37.8%), χ2[1] = 15.66, p < .001. A greater frequency of patients included in the analytic sample reported having ever tried to taper their methadone than those who were excluded, (61.6% vs. 33.9%), χ2[1] = 28.64, p < .001.

Measures

Substance use

Patients reported how frequently they used alcohol, cannabis, and illicit opioids (heroin or non-prescribed opioid pain medications) in the past four weeks (did not use, once a month, at least once a week, every day). Patients were also asked whether they used cocaine or non-prescribed stimulant medications (e.g., Adderall® or Ritalin®) and benzodiazepines (e.g., Klonopin®, Xanax®, Ativan®, Valium®) in the past four weeks. We created dichotomous variables to assess whether patients used each substance (1 = did not report use, 2 = reported use).

Covariates

We considered potential covariates that are associated with MMT outcomes to explore correlates of latent class membership (Nosyk et al., 2009; Proctor et al., 2016; Roux et al., 2016; Vigna-Taglianti et al., 2016; Ward, Mattick, & Hall, 1994): sociodemographic characteristics [(marital status: 0 = not married, 1 = married; employment: 0 = unemployed/receiving disability, 1 = employed part-time/fulltime; and homelessness: 0 = own or rent house or apartment/living with friend or family/living in sober house/staying at shelter; 1 = homeless/living in car, on the street/going place to place)]; treatment duration (0 = 1 year or less vs. 1 = 2 or more years); history of treatment [if first time in an opioid treatment program: 0 = no, 1 = yes; ever taken buprenorphine/naloxone (Suboxone®): 0 = no, 1 = yes; ever taken naltrexone (Vivitrol®): 0 = no, 1 = yes]; and depression and anxiety symptoms. Depressive and anxiety symptoms was assessed with the sum of four items from the Patient Health Questionnaire 2-item depression and 2-item anxiety modules, which is a brief validated tool for detecting both anxiety and depressive disorders (PHQ-4; Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, & Lowe, 2009; Löwe et al., 2010). Patients were asked how often in the past two weeks they were bothered by four problems such as having little interest or pleasure in doing things. Response choices consisted of 0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half the days, 3 = nearly every day. A summed score was created (range = 0 – 6, α = .89).

Analytic strategy

Latent class analysis (LCA) was used to identify the class structure of substance use among MMT patients. LCA classifies a population into mutually exclusive categorical latent variables derived from two or more observed discrete indicators (Collins & Lanza, 2010; Goodman, 1974). LCA is a person-centered approach to empirically identifying population subgroups ( i.e., classes) based on common combinations of a set of variables that represent both type and quantity of risk factors in a given population (Lanza & Rhoades, 2013; Lanza, Rhoades, Nix, & Greenberg, 2010). For the present study, models were conducted separately for men and women to allow gender to moderate the number of classes, class sizes, measurement parameters, and associations of covariates with classes (Cleland, Lanza, Vasilenko, & Gwadz, 2017). To address our first aim, we used Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), sample-size-adjusted BIC (a-BIC), and G2 fit statistic to compare relative fit of competing models with one through five classes while accounting for model complexity, entropy (Celeux & Soromenho, 1996), and chi-squared tests.

To address our second aim, we considered potential covariates and their association with latent class membership. First, we conducted separate multivariate analyses of variances (MANOVAs) or independent samples t-tests and chi-squares for men and women between each of the covariates and latent classes, depending on number of classes established in the first aim. If there were only two classes, t-tests were conducted and if classes consisted of three or more subgroups, MANOVAs were conducted. In the interest of parsimony, we only included covariates that were significantly associated with the latent classes. We entered all significant covariates in the same multinomial regression model, which was conducted separately for men and women. Descriptive statistics were obtained using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0 (Armonk, NY) and LCA and regressions were conducted using SAS 9.4 with the publicly available PROC LCA macro (Lanza, Collins, Lemmon, & Schafer, 2007; Lanza, Dziak, Wagner, & Collins, 2015).

Results

In this sample of 341 MMT patients, 47.2% were women. Table 1 depicts patient characteristics for men and women. Compared with men, women had lower rates of being employed, χ2(2) = 15.46, p < .001 and received higher doses of methadone, t(339) = 2.04, p = .042. There were no significant differences in marital status, educational attainment, homelessness, reason for starting treatment, treatment duration, Suboxone use, or Vivitrol use.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients receiving methadone maintenance treatment by gender (N = 341)

| Men (n = 180) | Women (n = 161) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or Percent (n) | Mean (SD) or Percent (n) | p-value | |

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age (range 20 to 70 years) | 40.12 (10.77) | 39.34 (10.77) | .504 |

| Educational attainment | .348 | ||

| Less than high school/GED | 17.2 (31) | 11.8 (19) | |

| High school diploma/GED | 31.7 (57) | 29.2 (47) | |

| Some college | 37.8 (68) | 41.0 (66) | |

| College and beyond | 13.3 (24) | 18.0 (29) | |

| Employment status | < .001 | ||

| Unemployed | 27.8 (50) | 43.5 (70) | |

| On disability | 20.6 (37) | 25.5 (41) | |

| Working part-time or full-time | 51.7 (93) | 31.1 (50) | |

| Married | 15.0 (27) | 11.2 (18) | .298 |

| Homeless | 5.6 (10) | 10.6 (17) | .088 |

| Treatment characteristics | |||

| Methadone dose (range 3 to 240 mg/day) | 78.40 (41.03) | 87.30 (40.23) | .042 |

| First time enrolled | 37.2 (67) | 38.5 (62) | .807 |

| Treatment duration (2 years or more) | 71.1 (128) | 65.8 (106) | .295 |

| Ever used Suboxone® | 72.2 (130) | 64.0 (103) | .102 |

| Ever used Vivitrol® | 2.2 (4) | 2.5 (4) | .873 |

| PHQ-4 depression and anxiety symptoms (range 0 to 12) | 5.14 (3.71) | 5.78 (3.70) | .113 |

Note.

Stimulants consisted of non-prescription stimulants (Adderall®, Ritalin®) or cocaine.

Illicit opioids consisted of heroin or non-prescription pain medications.

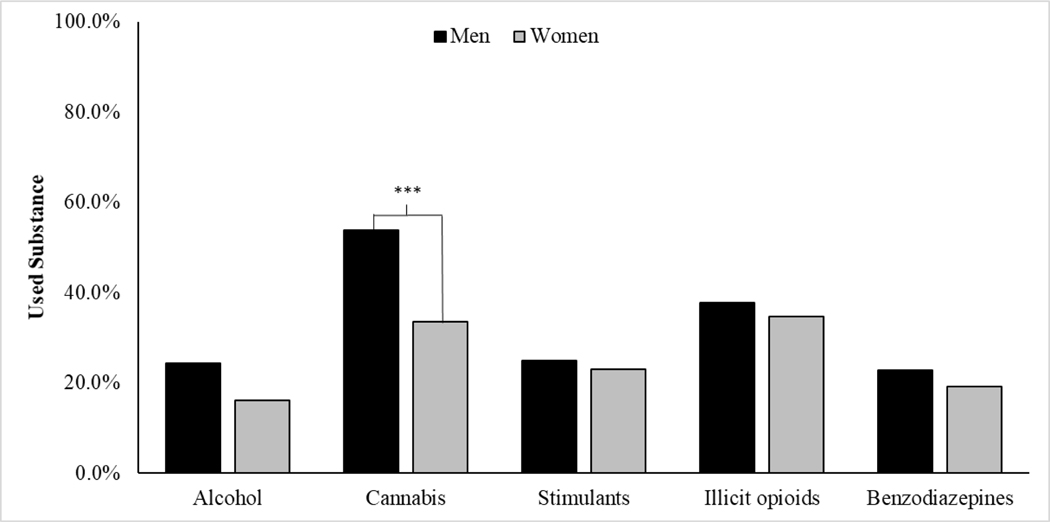

Most patients (74.8%) had used one or more substances in the past month, which was more common among men than women, χ2[1] = 8.10, p = .004. There were gender differences in the types of substances used (see Figure 1). Relative to women, men were significantly more likely to use cannabis (χ2 [1] = 14.62, p < .001) and marginally more likely to use alcohol (χ2 [1] = 3.59, p = .058). There were no gender differences in stimulant, illicit opioid, or benzodiazepine use.

Figure 1.

Use of alcohol, cannabis, stimulants, illicit opioids, and benzodiazepines in the past four weeks among men and women receiving MMT. Note: Stimulants consisted of non-prescription stimulants (Adderall®, Ritalin®) or cocaine. Illicit opioids consisted of heroin or non-prescription opioid pain medications.***Indicates a significant difference between men and women at p < .001.

Latent Classes of Substance Use

Latent class analyses were conducted for the full sample in preliminary analyses to explore gender differences when probabilities were constrained to be equal for men and women compared to freely estimated. Classes differed for the total sample versus women and men individually. For the total sample classes included: Unlikely Users (12.7% women; 37.6% men), or those with low probabilities of substance use in the past four weeks; Cannabis Users (46.9% women, 67.2% men), or those with a high probability of using only cannabis; and Stimulant/Opioid Users those with high probabilities of reporting stimulant and illicit opioid use (20.2% women, 15.4% men).

The three-class model for women was determined to be the best model in terms of fit and interpretability (Table 2). The first class was labeled Unlikely Users (63.3%), or those with low probabilities of substance use in the past four weeks. Class 2, Cannabis/Opioid Users (23.7%),was characterized by a high probability of using both cannabis and illicit opioids (Table 3). The third class, Stimulant/Opioid Users (13.0%), consisted of women with high probabilities of reporting stimulant and illicit opioid use.

Table 2.

Fit statistics of the latent class analyses

| Number of classes | G2 | df | AIC | BIC | a-BIC | Entropy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n =161) | 1 | 63.05 | 26 | 73.05 | 88.46 | 72.63 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 28.05 | 20 | 50.05 | 83.94 | 49.12 | 0.57 | |

| 3 | 18.00 | 14 | 52.00 | 104.38 | 50.56 | 0.67 | |

| 4 | 11.77 | 8 | 57.77 | 128.65 | 55.84 | 0.68 | |

| 5 | 5.99 | 2 | 63.99 | 153.35 | 61.55 | 0.69 | |

| Men (n = 180) | 1 | 52.26 | 26 | 69.26 | 85.22 | 69.39 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 32.65 | 20 | 54.65 | 89.77 | 54.93 | 0.60 | |

| 3 | 19.44 | 14 | 53.44 | 107.72 | 53.88 | 0.69 | |

| 4 | 18.39 | 8 | 64.39 | 137.83 | 64.99 | 0.56 | |

| 5 | 6.31 | 2 | 64.31 | 156.90 | 65.06 | 0.73 | |

Note. Selected models are bolded. AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; a-BIC = adjusted BIC.

Table 3.

Probability of substance use over the past 4 weeks across latent classes (N =341).

| Women(N = 161) | Men(N = 180) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1: Unlikely Users | Class 2: Cannabis/Opioid Users | Class 3: Stimulant/Opioid Users | Class 1: Unlikely Users | Class 2: Alcohol/Cannabis Users | Class 3: Cannabis/Stimulant/Opioid Users | |

| Class membership probabilities | 59.8% | 23.7% | 13.0% | 52.8% | 21.9% | 25.3% |

| Item response probabilities | ||||||

| Alcohol | ||||||

| No alcohol use | 0.88 | 0.68 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.46 | 0.72 |

| Used alcohol | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.54 | 0.28 |

| Cannabis | ||||||

| No cannabis use | 0.78 | 0.20 | 0.97 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.46 |

| Used cannabis | 0.22 | 0.80 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.97 | 0.54 |

| Stimulants | ||||||

| No stimulant use | 0.97 | 0.61 | 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.06 |

| Used stimulants | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.91 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.94 |

| Illicit opioids | ||||||

| No illicit opioid use | 0.85 | 0.44 | 0.11 | 0.76 | 0.64 | 0.33 |

| Used illicit opioids | 0.15 | 0.56 | 0.89 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.67 |

| Benzodiazepines | ||||||

| No benzodiazepine use | 0.89 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.87 | 0.68 | 0.65 |

| Used benzodiazepines | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.35 |

Note. Table entries for the item-response probabilities represent probabilities of endorsing the indicators of substance use on latent class membership. Highest response probabilities within each item are in bold type to facilitate interpretation.

For men, a three-class model was also determined to be the best model (Table 2). Class 1 was labeled Unlikely Users (52.8%) and was characterized by higher probability of not using any substances in the past four weeks (Table 3). Class 2, Alcohol/Cannabis Users, included men with a high probability of using alcohol and cannabis (21.9%). Lastly, the third class (Cannabis/Stimulant/Opioid Users) consisted of men with high probabilities of using cannabis, stimulants, and illicit opioids (25.3%).

Gender Differences in Correlates of Latent Class Membership

Given that class composition of the total sample differed from individual genders, further analyses proceeded to examine correlates of class membership to examine potential risk factors for each group.

Among women, there were no differences in sociodemographic characteristics across groups except for age, F (2, 158) = 7.25, p = .001. Those in the Cannabis/Opioid use class (mage = 33.89, sd = 9.74) were younger than those in the Stimulant/Opioid use class (mage = 43.35, sd = 9.84), Tukey = 7.46 years (95% CI: 0.40, 14.50).

For treatment history, more Unlikely Users (46.2%) were in MMT for the first time than Cannabis/Opioid Users (10.0%) and Stimulant/Opioid Users (31.4%), χ2 [2] = 10.27, p = .006. Conversely, more Cannabis/Opioid Users (85.1%) had ever taken Suboxone® as compared to 70.0% of Stimulant/Opioid Users and 55.7% of Unlikely Users, χ2[2] = 10.67, p = .005. Lastly, among women, there were significant differences in depressive/anxiety symptoms [F (2, 158) = 7.25, p =.001]. Tukey’s test revealed a significant mean difference in PHQ-4 scores between Cannabis/Opioid Users (m = 5.63, sd = 3.05) and Stimulant/Opioid Users (m = 8.60, sd = 3.22); furthermore, there was a significant difference in depressive/anxiety symptoms between Unlikely Users (m = 5.30, sd = 3.77) and Stimulant/Opioid Users. There were no significant differences between groups in current treatment characteristics.

For men, there were significant differences across classes in homelessness (χ2 [2] = 7.68, p =.022) and employment status, χ2 [4] = 12.28, p =.015. Cannabis/Stimulant/Opioid Users had the highest prevalence of homelessness (13.3%) followed by Unlikely Users (4.0%), and Alcohol/Cannabis Users (0.0%). Cannabis/Stimulant/Opioid Users had the highest rate of unemployment (42.2%), followed by Alcohol/Cannabis Users (23.5%), and Unlikely Users (22.8%). There were no significant differences between subgroups in treatment characteristics, treatment history, and depressive/anxiety symptoms among men.

Identifying Correlates of Latent Class Membership

Among women, ever having used use of Suboxone® (2LLΔ = 9.45, df = 2, p = .009) and depressive/anxiety symptoms (2LLΔ = 14.54, df = 2, p = .001) were significantly associated with latent class membership. As shown in Table 4, those who reported ever using use of Suboxone® had 3.97 increased odds of being a Stimulant/Opioid User relative to a Cannabis/Opioid User. Lastly, higher depressive/anxiety symptoms was associated with decreased odds of being a Cannabis/Opioid User (AOR = 0.55) and Stimulant/Opioid User (AOR = 0.80) relative to being an Unlikely User. Put differently, each one-unit increase in depressive/anxiety symptoms was linked to 1.82 times more likely being an Unlikely User than a Cannabis/Opioid User and 1.25 times more likely of being an Unlikely User than a Stimulant/Opioid User. Higher depressive/anxiety symptoms was also associated with a 1.46 increase in likelihood of being a Stimulant/Opioid User relative to a Cannabis/Opioid User. Being a first-time enrollee in MMT was not associated with latent class membership.

Table 4.

Multinomial logistic regression models predicting class membership among women (N = 161).

| Class 2 vs 1 | Class 3 vs 1 | Class 3 vs 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | OR | 95% CI | b | OR | 95% CI | b | OR | 95% CI | |

| First time enrolled in treatmenta | 0.86 | 2.35 | [0.45–12.21] | −0.25 | 0.78 | [0.45–12.21] | −1.10 | 0.33 | [0.13–0.83] |

| Ever used Suboxone®a | −0.30 | 0.74 | [0.16–3.55] | 1.08 | 2.94 | [0.16–3.55] | 1.38** | 3.97 | [1.49–10.57] |

| Depressive/anxiety symptomsb | −0.60** | 0.55 | [0.42–0.72] | −0.23* | 0.80 | [0.42–0.72] | 0.38** | 1.46 | [1.22–1.74] |

Note. Class 1 = Unlikely Users; Class 2 = Cannabis/Opioid Users; Class 3 = Stimulant Opioid Users.

p < .05;

p < .01;

OR = Odds ratio; CI = Confidence interval.

Response choices: 0 = no, 1 = yes

PHQ-4 depressive and anxiety symptom modules (range 0 to 12).

For men, homelessness was associated with class membership, 2LLΔ = 7.48, df = 2, p = .024. Men who were homeless had a 76.88 and 437.37 greater odds of being a Cannabis/Stimulant/Opioid User relative to a Unlikely User and an Alcohol/Cannabis user, respectively (see Table 5). Employment status was also associated with class membership, 2LLΔ = 7.65, p = .022, with employed men showing 0.17 decreased likelihood of being an Alcohol/Cannabis User relative to a Unlikely User. In other words, unemployed men were 5.88 times more likely to be an Alcohol/Cannabis User than an Unlikely User. Conversely, those employed were 4.65 times more likely to be a Cannabis/Stimulant/Opioid User relative to an Alcohol/Cannabis User.

Table 5.

Multinomial logistic regression models predicting class membership among men (N = 180).

| Class 2 vs 1 | Class 3 vs 1 | Class 3 vs 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | OR | 95% CI | b | OR | 95% CI | b | OR | 95% CI | |

| Homelessa | −1.74 | 0.18 | [0.00–33.10] | 4.34* | 76.88 | [1.74–3382.10] | 6.08* | 437.37 | [1.09–176237.00] |

| Employment statusb | −1.80* | 0.17 | [0.03–0.99] | 2.84 | 17.26 | [0.53–561.04] | 4.65* | 104.38 | [2.16–5047.90] |

Note. Class 1 = Unlikely Users; Class 2 = Alcohol/Cannabis Users; Class 3 = Cannabis/Stimulant/Opioid Users.

p < .05.

OR = Odds ratio; CI = Confidence interval.

Response choices: 0 = no, 1 = yes

Employment categories: 0 = not employed (includes those receiving disability benefits), 1 = employed part-time or fulltime.

Discussion

This study characterized subgroup of concurrent substance use and identified correlates of these groupings in a sample of men and women receiving MMT. Three-quarters of patients used at least one substance in the past four weeks. Consistent with previous studies (Hassan & Le Foll, 2019; Li et al., 2011; McCabe et al., 2017; White et al., 2014), these findings suggest that continued and polysubstance use is relatively common among MMT patients. These findings also mirror previous literature showing that men are more likely than women to have multiple substance use disorders and to have concurrently use substances (John et al., 2018; Midanik, Tam, & Weisner, 2007; Zambon et al., 2017). This study suggests that there are gender differences in both groupings of concurrent substance use and correlates of those groupings, which has implications for more patient-centered delivery of MMT.

Rates of Concurrent Substance Use

In the present study, there were distinct subgroups of substance use between men and women in MMT. We found that over one-third of women had a high probability of using either cannabis and illicit opioids (23.7%) or stimulants and opioids (13.0%). By contrast, nearly half of men reported using either alcohol and cannabis (21.9%) or cannabis, illicit opioids, and stimulants (25.3%). There is evidence that cannabis is used to combat effects of “coming down” from stimulants, which might explain the concurrent use of these substance among men (Compton & Volkow, 2006; Olière, Joliette-Riopel, Potvin, & Jutras-Aswad, 2013). Stimulants have a significant potential for abuse that might be intensified when used with opioids (Hobelmann & Clark, 2016, p. 80). Recent research has documented poorer physical and mental health outcomes and greater healthcare utilization among stimulant users who misuse prescription opioids and, in 2017, 50.4% of psychostimulant-involved deaths also included opioids (Kariisa, Scholl, Wilson, Seth, & Hoots, 2019; Timko, Han, Woodhead, Shelley, & Cucciare, 2018). Thus, use of both stimulants and opioids during MMT may be of particular concern, especially among women who tend to escalate their use more rapidly than men and have greater difficulty quitting these substances (Becker & Hu, 2008).

Alcohol and cannabis use were more prevalent among men than women, with cannabis emerging in the two substance use classes for men. These findings mirror research previously documenting gender differences in rate of single use of recreational cannabis among the general population and clinical samples (e.g., Ehlers et al., 2010). Additionally, previous studies have identified cannabis use as a risk factor for opioid use and misuse (e.g., Morley, Ferris, Winstock, & Lynskey, 2017). Given that roughly a quarter of men and women in MMT reported using both cannabis and illicit opioids, it may be important to screen for cannabis use and incorporate additional interventions to support patients to minimize risky substance use during MMT.

Although benzodiazepine misuse was reported by roughly one in five men and women in this sample, there were no significant gender differences as found in previous research (e.g., Maremmani et al., 2010) and it did not emerge within any of the substance use subgroups. This suggests that both men and women in MMT may commonly use benzodiazepines, regardless of other concurrent substance use. Benzodiazepine use during MMT has negative implications for treatment outcomes, overall health, and risk of fatal and non-fatal overdose (Jones, Mogali, & Comer, 2012). Consequently, it will be important for future research to consider ways to address the co-use of benzodiazepines and methadone among both male and female patients.

Correlates of Concurrent Substance Use

Women.

Greater depressive/anxiety symptoms were a risk factor for having co-used stimulants and opioids as compared to cannabis and opioids among women only. Additionally, among women, those with greater depressive/anxiety symptoms were more likely to not have used any substances compared to co-using cannabis and opioids or stimulants and opioids. There is currently a dearth of literature documenting gender differences in depressive and anxiety symptoms within the context of concurrent or single use of opioids with stimulants and cannabis. However, prior studies have documented women having higher rates of comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety) among general and clinical populations than men (Back et al., 2011; Becker & Hu, 2008; Brady et al., 2009; Chen et al, 2011; Huang et al., 2006; Tetrault et al., 2008). There is also evidence suggesting that women with OUD are more likely to report using opioids to cope with negative emotions (McHugh et al., 2013). More recent work has also suggested that women in MMT who experience severe loneliness are more likely to use opioids (Polenick, Cotton, Bryson, & Birditt, 2019). It may be that women who use opioids with cannabis or stimulants do so in part to manage emotional distress, potentially resulting in lower levels of depression/anxiety than those who do not use substances. Additional research is needed to better understand motives regarding concurrent use of substances among women in MMT.

Men.

We found that being homeless was associated with an increased likelihood of having used cannabis, stimulants, and opioids as compared to being an unlikely substance user or using only alcohol and cannabis. Substance use disorders are most prevalent among those who are homeless and have been linked to chronic homelessness (Fazel, Khosla, Doll, & Geddes, 2008). However, there are mixed findings as to whether the link between substance use or related disorders varies by gender. Some studies have reported higher rates among homeless men than women (e.g., Ibabe, Stein, Nyamathi, & Bentler, 2014) and others have documented similar rates in substance use and disorders between homeless men and women (e.g., Edens, Mares, & Rosenheck, 2011). Previous research has documented smaller social networks and less social support among homeless men than women and less satisfaction in social support among men with substance use disorders compared to those without use disorders (de Souza et al., 2014; Winetrobe et al., 2017). Thus, substance using homeless men may be particularly vulnerable to lower quantity or quality of social support as compared to substance using women in the context of MMT.

We also found that being employed was a significant factor for substance use among men. Those who used cannabis, stimulants, and opioids had higher rates of unemployment compared to those who were unlikely to have used any substances in the past month as well as those who used alcohol and cannabis. Further analyses revealed that employment status predicted use subgroup, such that unemployed men were over five times more likely to use alcohol and cannabis than being an unlikely user; conversely, being employed was also associated with over four times increased odds of using cannabis, stimulants, and opioids relative to using only alcohol and cannabis. Using data from the 2002–2010 waves of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Compton and colleagues (2014) found that among those who did not previously use cannabis, future job loss preceded initiation of cannabis use. However, future job loss followed cannabis use among those who had used cannabis before. This may suggest that cannabis use is a risk factor for job loss but is dependent on previous use history.

There is also literature documenting unemployment as a risk of simultaneous use (i.e., co-ingestion) of alcohol and cannabis versus concurrent use (i.e., using within a given period of time; Subbaraman & Kerr, 2015); however, gender was not explored in these associations. Conversely, those who are employed but still co-use cannabis, stimulants, and opioids may be in treatment due to mandates by an employer or other external pressures. More research is needed to determine how these specific substance use groupings are related to socioeconomic factors (e.g., employment status), particularly for men.

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations. First, sample sizes were relatively small for LCA. However, statistical power is largely affected by number of classes, class proportions, strength of the association between class and indicators, and the number of indicators (Gudicha, Tekle, & Vermunt, 2016). That is, when classes are well separated (higher entropy values), sample sizes of low as 100 can achieve a power of .8 or more. It has been demonstrated that with an entropy value of .62 for a 3-class solution with approximately six indicators, a sample size of 140 would be required to achieve such power (Gudicha, Tekle, & Vermunt, 2016). In the present study, three-class models were examined with five indicators, and class separation was adequate with entropy values of .67 and .69 for women (n = 161) and men (n = 180) respectively. This suggests relatively high associations between the indicators and classes; therefore it is reasonable to assume sufficient power for analyses. Still, future studies should replicate the present findings using larger samples.

Second, the cross-sectional data prevented examination of causal associations. The self-selected convenience sample may also not be broadly representative of individuals receiving MMT. Moreover, relative to patients included in this study, patients excluded due to missing data were older, less educated, and more likely to be employed. Hence, the present findings are may not generalize to MMT populations who are older, have lower educational attainment, and are working.

Additionally, the lack of urine analyses to confirm substances use in conjunction with self-reported survey measures is another limitation, which could introduce bias in reporting these behaviors. We also did not assess whether substances were used simultaneously or co-ingested. Similarly, the dichotomized substance use variables (any use in the past month vs. none) may mask important differences in quantity of each substance used and influence the groups that were identified (e.g., the lack of benzodiazepine representation in class makeup). Future research should include biological indicators as well as self-report measures of substance use to examine how and when these substances are used together, ideally using longitudinal data. Additionally, future work should assess other factors important to treatment outcomes (e.g., history of substance use, craving) and include more comprehensive psychiatric assessments (e.g., the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; Sheehan et al., 1998) to better understand how these factors contribute to concurrent use of opioids with other substances. Despite these shortcomings, this study lays the foundation for future work to elucidate risk and protective factors for distinctive patterns of substance use and how this differs by gender for patients during MMT.

Conclusions

In summary, this study suggests that risk factors for continued and concurrent substance use in methadone-maintained patients may differ by gender. The current findings emphasize the need for a better understanding of protective and risk factors for subgroups of patterns of substance use to provide the most effective treatments among men and women using multiple substances in MMT.

Table 6.

Probability of responses to items measuring substance use over the past 4 weeks given latent class membership for total sample (N =341)

| Class 1: Low Users | Class 2: Cannabis | Class 3: Stimulant/Opioid Users | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latent class membership probabilities | |||

| Men | 37.6% | 46.9% | 15.4% |

| Women | 12.7% | 67.2% | 20.2% |

| Item response probabilities for indicators | |||

| Alcohol | |||

| No alcohol use | 0.89 | 0.58 | 0.81 |

| Used alcohol | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.19 |

| Cannabis | |||

| No cannabis use | 0.73 | 0.06 | 0.75 |

| Used cannabis | 0.27 | 0.94 | 0.25 |

| Stimulants | |||

| No stimulant use | 1.00 | 0.71 | 0.08 |

| Used stimulants | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.92 |

| Illicit opioids | |||

| No illicit opioid use | 0.80 | 0.55 | 0.25 |

| Used illicit opioids | 0.20 | 0.45 | 0.75 |

| Benzodiazepines | |||

| No benzodiazepine use | 0.88 | 0.66 | 0.69 |

| Used benzodiazepines | 0.12 | 0.34 | 0.31 |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health [grant number T32 MH073553-11]. Dr. Lin was supported by a Career Development Award (CDA 18-008) from the US Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Service. Dr. Polenick was supported by the National Institute on Aging [grant number K01AG059829]. The funding sources had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Back SE, Lawson KM, Singleton LM, & Brady KT (2011). Characteristics and correlates of men and women with prescription opioid dependence. Addictive Behaviors, 36(8), 829–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawor M, Dennis BB, Varenbut M, Daiter J, Marsh DC, Plater C, … Samaan Z. (2015a). Sex differences in substance use, health, and social functioning among opioid users receiving methadone treatment: a multicenter cohort study. Biology of Sex Differences, 6 (1), 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawor M, Dennis BB, Bhalerao A, Plater C, Worster A, Varenbut M, … Samaan Z. (2015b). Sex differences in outcomes of methadone maintenance treatment for opioid use disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ Open, 3(3), E344–E351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JB, & Hu M. (2008). Sex differences in drug abuse. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 29(1), 36–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, & Hartwell K. (2009). Women and addiction: A comprehensive handbook. (Brady KT, Back SE, & Greenfield SF, eds.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burt MR, Aron LY, Douglas T, Valente J, Lee E, & Iwen B. (1999). Homelessness: Programs and the People They Serve | Findings of the National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/66286/310291-Homelessness-Programs-and-the-People-They-Serve-Findings-of-the-National-Survey-of-Homeless-Assistance-Providers-and-Clients.PDF

- Celeux G, & Soromenho G. (1996). An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification, 13(2), 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Evidence-Based Strategies for Preventing Opioid Overdose: What’s Working in the United States. Retrieved April 19, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2018-evidence-based-strategies.pdf

- Chen KW, Banducci AN, Guller L, Macatee RJ, Lavelle A, Daughters SB, & Lejuez CWW (2011). An examination of psychiatric comorbidities as a function of gender and substance type within an inpatient substance use treatment program. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 118(2–3), 92–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland CM, Lanza ST, Vasilenko SA, & Gwadz M. (2017). Syndemic risk classes and substance use problems among adults in high-risk urban areas: A latent class analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 5(September), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, & Lanza ST (2009). Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: With Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Gfroerer J, Conway KP, & Finger MS (2014). Unemployment and substance outcomes in the United States 2002–2010. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 142, 350–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, & Volkow ND (2006). Abuse of prescription drugs and the risk of addiction. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 83, S4–S7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davstad I, Stenbacka M, Leifman A, Beck O, Korkmaz S, & Romelsjo A. (2007). Patterns of illicit drug use and retention in a methadone program: A longitudinal study. Journal of Opioid Management, 3(1), 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza J, Villar Luis MA, Ventura CA, Barbosa SP, & dos Santos CB (2016). Perception of social support: a comparative study between men with and without substance-related disorders. Journal of Substance Use, 21(1), 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Edens EL, Mares AS, & Rosenheck RA (2011). Chronically homeless women report high rates of substance use problems equivalent to chronically homeless men. Women’s Health Issues, 21(5), 383–389. 10.1016/j.whi.2011.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Gizer IR, Vieten C, Gilder DA, Stouffer GM, Lau P, & Wilhelmsen KC (2010). Cannabis dependence in the San Francisco Family Study: age of onset of use, DSM-IV symptoms, withdrawal, and heritability. Addictive Behaviors, 35(2), 102–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Khosla V, Doll H, & Geddes J. (2008). The prevalence of mental disorders among the homeless in western countries: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Medicine, 5(12), e225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei JTB, Yee A, & Habil MH Bin. (2016). Psychiatric comorbidity among patients on methadone maintenance therapy and its influence on quality of life. The American Journal on Addictions, 25(1), 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichter MM, & Quadflieg N. (2006). Intervention effects of supplying homeless individuals with permanent housing: a 3-year prospective study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 113(s429), 36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink DS, Hu R, Cerdá M, Keyes KM, Marshall BDL, Galea S, & Martins SS (2015). Patterns of major depression and nonmedical use of prescription opioids in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 153, 258–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florence CS, Zhou C, Luo F, & Xu L. (2016). The economic burden of prescription opioid overdose, abuse, and dependence in the United States, 2013. Medical Care, 54(10), 901–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn MC, Sohler NL, Starrels JL, Maradiaga J, Jost JJ, Arnsten JH, & Cunningham CO (2016). Characteristics of methadone maintenance treatment patients prescribed opioid analgesics. Substance Abuse, 37(3), 387–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA (1974). Exploratory latent structure analysis using both identifiable and unidentifiable models. Biometrika. [Google Scholar]

- Gudicha DW, Tekle FB, & Vermunt JK (2016). Power and sample size computation for wald tests in latent class models. Journal of Classification, 33, 30–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, & Grant BF (2015). The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Waves 1 and 2: review and summary of findings. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(11), 1609–1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan AN, & Le Foll B. (2019). Polydrug use disorders in individuals with opioid use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 198, 28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory Hobelmann J, Clark MR, Hobelmann JG, & Clark MR (2016). Benzodiazepines, alcohol, and stimulant use in combination with opioid use. In Staats PS & Silverman SM (Eds.), Controlled Substance Management in Chronic Pain: A Balanced Approach (pp. 75–86). [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Ruan WJ, Saha TD, … Grant BF (2006). Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of nonmedical prescription drug use and drug use disorders in the United States. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(07), 1062–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibabe I, Stein JA, Nyamathi A, & Bentler PM (2014). Predictors of substance abuse treatment participation among homeless adults. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46(3), 374–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John WS, Zhu H, Mannelli P, Schwartz RP, Subramaniam GA, & Wu L-T (2018). Prevalence, patterns, and correlates of multiple substance use disorders among adult primary care patients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 187, 79–87. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Einstein EB, & Compton WM (2018, May 1). Changes in synthetic opioid involvement in drug overdose deaths in the United States, 2010–2016. Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 319, p. 1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariisa M, Scholl L, Wilson N, Seth P, & Hoots B. (2019). Drug overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants with abuse potential — United States, 2003–2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(17), 388–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Borg L, Ducat E, & Ray B. (2010). Pharmacotherapy in the treatment of addiction: methadone. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 29(2), 200–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Janet BW, Williams DSW, Lö B, Williams JBW, & Lowe B. (2009). An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. In Psychosomatics (Vol. 50). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdyak P, Gomes T, Yao Z, Mamdani MM, Hellings C, Fischer B, … Juurlink DN (2012). Use of other opioids during methadone therapy: a population-based study. Addiction, 107(4), 776–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Collins LM, Lemmon DR, & Schafer JL (2007). PROC LCA: A SAS procedure for latent class analysis. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 671–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, & Rhoades BL (2013). Latent class analysis: An alternative perspective on subgroup analysis in prevention and treatment. Prevention Science, 14(2), 157–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Rhoades BL, Nix RL, & Greenberg MT (2010). Modeling the interplay of multilevel risk factors for future academic and behavior problems: A person-centered approach. Development and Psychopathology, 22(2), 313–335. 10.1017/S0954579410000088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JD, Nunes EV, Novo P, Bachrach K, Bailey GL, Bhatt S, … Rotrosen J. (2018). Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): A multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 391(10118), 309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine AR, Lundahl LH, Ledgerwood DM, Lisieski M, Rhodes GL, & Greenwald MK (2015). Gender-specific predictors of retention and opioid abstinence during methadone maintenance treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 54, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Sangthong R, Chongsuvivatwong V, McNeil E, & Li J. (2011). Multiple substance use among heroin-dependent patients before and during attendance at methadone maintenance treatment program, Yunnan, China. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 116(1–3), 246–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwe B, Wahl I, Rose M, Spitzer C, Glaesmer H, Wingenfeld K, … Brähler EA 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: Validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 122(1–2), 86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, & Rosenblum A. (2001). Leaving methadone treatment: lessons learned, lessons forgotten, lessons ignored. The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, New York, 68(1), 62–74. Retrieved from http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/11135508 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maremmani I, Pani PP, Mellini A, Pacini M, Marini G, Lovrecic M, … Shinderman M. (2007). Alcohol and cocaine use and abuse among opioid addicts engaged in a methadone maintenance treatment program. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 26(1), 61–70. 10.1300/J069v26n01_08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, & Davoli M. (2014). Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2). [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, West BT, Jutkiewicz EM, & Boyd CJ (2017). Multiple DSM ‐ 5 substance use disorders: A national study of US adults. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 32(5), e2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, DeVito EE, Dodd D, Carroll KM, Potter JS, Greenfield SF, … Weiss RD (2013). Gender differences in a clinical trial for prescription opioid dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 45(1), 38–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Tam TW, & Weisner C. (2007). Concurrent and simultaneous drug and alcohol use: Results of the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 90(1), 72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley KI, Ferris JA, Winstock AR, & Lynskey MT (2017). Polysubstance use and misuse or abuse of prescription opioid analgesics. PAIN, 158(6), 1138–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolai J, Moshagen M, & Demmel R. (2016). Patterns of alcohol expectancies and alcohol use across age and gender. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 126(3), 347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S, Larance B, & Lintzeris N. (2017). Opioid agonist treatment for patients with dependence on prescription opioids. Journal of the American Medical Association, 317(9), 967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyk B, Fischer B, Sun H, Marsh DC, Kerr T, Rehm JT, & Anis AH (2014). High levels of opioid analgesic co-prescription among methadone maintenance treatment clients in British Columbia, Canada: Results from a population-level retrospective cohort study. The American Journal on Addictions, 23(3), 257–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyk B, MacNab YC, Sun H, Fischer B, Marsh DC, Schechter MT, & Anis AH (2009). Proportional hazards frailty models for recurrent methadone maintenance treatment. American Journal of Epidemiology, 170(6), 783–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyk B, Sun H, Evans E, Marsh DC, Anglin MD, Hser Y-I, & Anis AH (2012). Defining dosing pattern characteristics of successful tapers following methadone maintenance treatment: results from a population-based retrospective cohort study. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 107(9), 1621–1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olière S, Joliette-Riopel A, Potvin S, & Jutras-Aswad D. (2013). Modulation of the endocannabinoid system: Vulnerability factor and new treatment target for stimulant addiction. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 4, 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polenick CA, Cotton BP, Bryson WC, & Birditt KS (2019). Loneliness and illicit opioid use among methadone maintenance treatment patients. Substance Use & Misuse, 0(0), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor SL, Copeland AL, Kopak AM, Hoffmann NG, Herschman PL, & Polukhina N. (2015). Predictors of patient retention in methadone maintenance treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(4), 906–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosic T, Naji L, Bawor M, Dennis B, Plater C, Marsh D, … Samaan Z. (2017). The impact of comorbid psychiatric disorders on methadone maintenance treatment in opioid use disorder: A prospective cohort study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 13, 1399–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux P, Lions C, Vilotitch A, Michel L, Mora M, Maradan G, … Carrieri PM (2016). Correlates of cocaine use during methadone treatment: Implications for screening and clinical management (ANRS Methaville study). Harm Reduction Journal, 13(1), 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, & Baldwin G. (2018). Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths — United States, 2013–2017. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(5152). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, … Dunbar GC (1998). The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-1V and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(S20), 22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyka M. (2017). Treatment of opioid dependence with buprenorphine: Current update. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 19(3), 299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenbacka M, Beck O, Leifman A, Romelsjö A, & Helander A. (2007). Problem drinking in relation to treatment outcome among opiate addicts in methadone maintenance treatment. Drug and Alcohol Review, 26(1), 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaraman MS, & Kerr WC (2015). Simultaneous versus concurrent use of alcohol and cannabis in the National Alcohol Survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39(5), 872–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, Han X, Woodhead E, Shelley A, & Cucciare MA (2018). Polysubstance use by stimulant users: Health outcomes over three years. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(5), 799–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Treviño L, Saiz P, García-Portilla M, Díaz-Mesa E, Sánchez-Lasheras F, Burón P, Casares M…& Bobes J. (2011). A 25-year follow-up of patients admitted to methadone treatment for the first time: Mortality and gender differences. Addictive Behaviors, 36 (12), 1184–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigna-Taglianti FD, Burroni P, Mathis F, Versino E, Beccaria F, Rotelli M, … Bargagli AM (2016). Gender differences in heroin addiction and treatment: Results from the VEdeTTE cohort. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(3), 295–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J, Mattick R, & Hall W. (1994). The effectiveness of methadone maintenance treatment: an overview. Drug and Alcohol Review, 13(3), 327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winetrobe H, Wenzel S, Rhoades H, Henwood B, Rice E, & Harris T. (2017). Differences in health and social support between homeless men and women entering permanent supportive housing. Women’s Health Issues, 27(3), 286–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambon A, Airoldi C, Corrao G, Cibin M, Agostini D, Aliotta F, … Giorgi I. (2017). Prevalence of polysubstance abuse and dual diagnosis in patients admitted to alcohol rehabilitation units for alcohol-related problems in Italy: Changes in 15 years. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 52(6), 699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]