Abstract

Since its outbreak in late December 2019 in Wuhan, coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has posed a therapeutic challenge for the world population, with a plenty of clinical pictures and a broad spectrum of severity of the manifestations. In spite of initial speculations on a direct role of primary or acquired immune deficiency in determining a worse disease outcome, recent studies have provided evidence that specific immune defects may either serve as an experimentum naturae entailing this risk or may not be relevant enough to impact the host defense against the virus. Taken together, these observations may help unveil pathogenetic mechanisms of the infection and suggest new therapeutic strategies. Thus, in this review, we summarize current knowledge regarding the mechanisms of immune response against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection and clinical manifestations with a special focus on children and patients presenting with congenital or acquired immune deficiency.

Key words: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, MIS-C, Inborn errors of immunity, Acquired immunodeficiency, Immunosuppression

Abbreviations used: ACE2, Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; ARDS, Acute respiratory distress syndrome; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; ICU, Intensive care unit; IEI, Inborn errors of immunity; IFN-I, Type I interferon; MIS-C, Multisystemic inflammatory syndrome in children; NK, Natural killer; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; S protein, Spike protein; TLR, Toll-like receptor

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has emerged as a novel infectious disease that spread worldwide, causing nearly 4 million deaths, presenting with pulmonary symptoms and, in some cases, evolving to multiorgan failure and death.1 Since its first description, the huge variability of the clinical manifestations has prompted studies aimed at identifying risk factors and predictors of worse outcome. To date, older age, male sex, and preexisting comorbidities have been recognized as the main risk factors of worse outcome. However, it has not yet been completely understood why, in rare occasions, younger patients and even children develop severe COVID-19. The role of defects of the innate immunity in predisposing to a worse outcome has been hypothesized since the beginning of the pandemic. However, although initially it was speculated that all the immunocompromised patients were at increased risk of a worse outcome, we are now understanding that the correct functioning of specific branches of the immune system is pivotal to define the outcome of the infection. On the other hand, even a complete absence of an entire immune compartment, as observed in agammaglobulinemic patients, is not always associated with a worse outcome. In this review, we will summarize the mechanisms of virus-host interaction and the immune alterations responsible for worse outcome.

Mechanisms of Immune Response to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 features

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a member of the Coronavirinae subfamily, including HKU1 and OC43, which cause the common cold. In the past 2 decades, new highly pathogenic human coronaviruses have emerged, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1, Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus, and, more recently, SARS-CoV-22 , 3 causing acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), with high morbidity and mortality. The natural host of the progenitors of the novel coronavirus is the bat, and a possible intermediate host for the passage to humans has been recently identified in Malayan pangolin.4 Human-to-human transmission occurs through respiratory droplets.5

Virus-host interaction

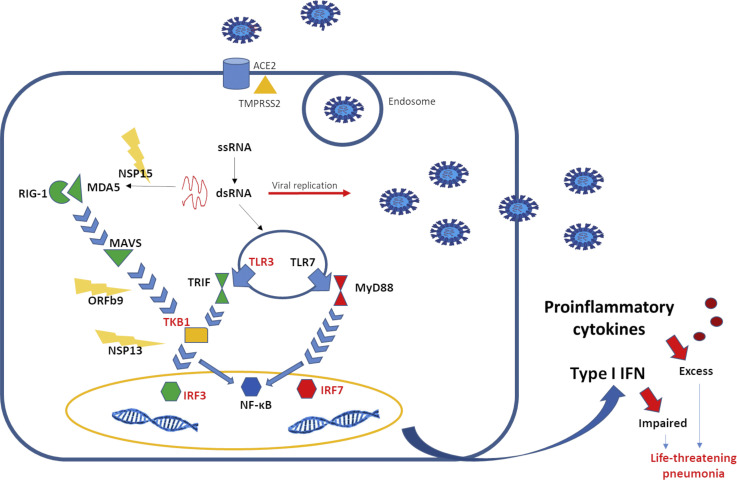

SARS-CoV-2 reaches the pulmonary alveoli and attacks its target cells, alveolar epithelial type 2 cells. The entrance in the host cell is mediated by the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor.6 , 7 Alveolar epithelial type 2 cells represent 83% of all ACE2-expressing cells, but ACE2 receptors are also expressed in kidney, heart, enterocytes, and endothelial cells. The binding between ACE2 receptor and SARS-CoV-2 is mediated by the spike protein (S protein),8 composed of 2 subunits: S1, which is the site of receptor-binding domain, and S2, which plays a critical role in the fusion of viral and cellular membranes. After binding ACE2 receptor, the S protein undergoes 2 steps of sequential protease cleavage. S protein priming is mediated by endosomal cysteine proteases, cathepsin B and L, or the serine protease such as transmembrane protease serine 2.9 Transmembrane protease serine 2 is expressed in nasal goblet and ciliated cells, esophagus, ileum, colon, and cornea together with ACE2 receptor.10 Given its role in favoring virus entrance in the host cells, transmembrane protease serine 2 inhibitors, such as camostat mesylate and nafamostat mesylate, have become a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of COVID-19 (Figure 1 ).11

Figure 1.

Virus-host interaction. SARS-CoV-2 protein S binds ACE2 receptor expressed on the surface of alveolar epithelial type 2. After 2 processes of cleavage, which involve the serine protease TMPRSS2, the viral particles are internalized and released into the cytoplasm. As viral replication occurs, double-stranded DNA is recognized by the TLR3 in the endosome and RIG-I and MDA5 in the cytosol. On activation, RIG-I–like receptors and TLRs induce signaling cascades, leading to the activation of transcription factors, such as NF-κB and IRF, and ultimately to the production and release of inflammatory mediators, such as IFN-I and cytokines. SARS-CoV-2 is able to compromise the production of IFN-I, through evasion mechanisms, including NSP15, which cuts the 5' polyuridines, which would have been recognized by MDA5, and ORF9b and NSP13, which interfere with signaling mediated by MAVS and TANK-binding kinase 1, respectively. The importance of a rapid IFN-I–mediated response against the virus is also demonstrated by the fact that mutations in IFN-I–related genes, indicated in red in the figure, are associated with a worse outcome. IRF, Interferon regulatory factor; MAVS, mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein; MDA5, melanoma differentiation–associated protein 5; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; NSP, Covs nonstructural protein; RIG-I, retinoic acid–inducible gene I; RLR, RIG-I–like receptor; TRIF, TIR-domain–containing adapter-inducing IFN-β; TKB1, TANK-binding kinase 1; TMPRSS2, transmembrane protease serine 2.

Activation of the immune system and phases of the disease

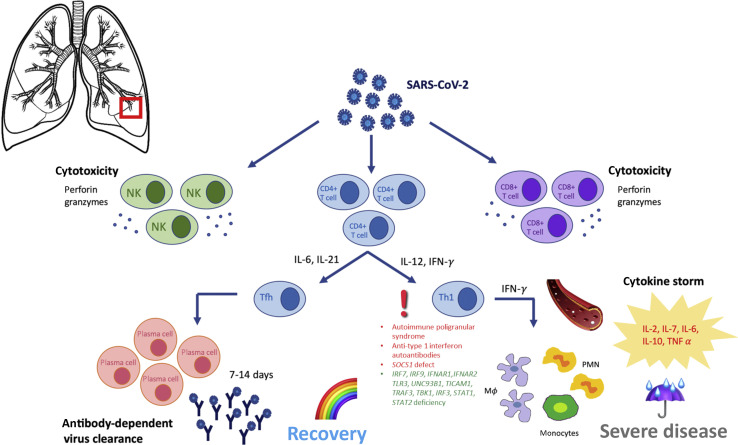

The entry of SARS-CoV-2 into human cells triggers both an innate and adaptive immune response to eliminate viral infection. Type I interferon (IFN-I) is directly produced by the respiratory epithelial cells. Retinoic acid–inducible gene I cytoplasmic receptors recognize viral RNA and, interacting with mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein, induce IFN-Iβ transcription. IFN-Iβ activates natural killer (NK) lymphocytes that kill infected cells inducing viral resistance. Toll-like receptor (TLR)3, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9, located on the endosomal membranes of NK lymphocytes and plasmacytoid dendritic cells, recognize viral RNA, activating the nuclear factor-κappa B pathway with the transcription of inflammatory cytokines IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α.12 The virus also triggers nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor pyrin domain-containing 3 family in macrophages, leading to the activation of the inflammasome, which synthesizes active IL-1 and IL-18, contributing to the virus-induced inflammatory response.13 Infected respiratory epithelial cells also present viral peptides to CD8+ T cells, which, in turn, are activated and expand, leading to cytotoxic virus-specific immune response.14 Dendritic cells and macrophages present the antigens to CD4+ T cells, which differentiate into TH1, TH17, and T follicular helper cells. T follicular helper cells induce the production of plasma cells from B cells. The early production of specific IgM reaches its peak in 7 days, whereas IgG and IgA appear a few days later.15 In nonsevere cases, adaptative immunity neutralizes the virus and terminates the immune response. In these cases, the normal immune response results in a typical self-limiting viral respiratory disease. In this phase (phase 1), lung damage depends on the cytopathic effect of the virus. When the adaptive immunity fails to clear the infection, the prolonged stimulation causes excessive cytokine release, leading to bilateral interstitial pneumonia with disseminated inflammation (phase 2) and can culminate in cytokine storm, sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, ARDS, and multiorgan failure. The severity of the clinical manifestations depends on a fine balance between host immune response and inflammation (Figure 2 ).16

Figure 2.

Activation of the immune system and phases of the disease. The entry of SARS-CoV-2 into human cells triggers both an innate and adaptive immune response to eliminate viral infection. Both NK cells and CD4 and CD8 T cells are involved in the adaptive response. In particular, CD4 T cells differentiate into Tfh and TH1 subtypes. Tfh induce the production of plasma cells from B cells, which produce specific immunoglobulin. In nonsevere cases, adaptive immunity neutralizes the virus and terminates the immune response. Prolonged stimulation of the innate branch of immunity causes excessive differentiation of CD4 cells into the TH1 subtype, with increased cytokine release culminating in cytokine storm. Cytokine storm leads to bilateral interstitial pneumonia with disseminated inflammation, which may culminate in sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, ARDS, and multiorgan failure. The IEIs that have been associated with more severe outcomes are indicated in red, whereas the IEIs for which a worse outcome can be predicted, based on data from the literature, are indicated in green. Tfh, T follicular helper.

Failure of the immune response and development of cytokine storm

Different causes may explain the variability of severity. For example, high doses of virus seem to hinder the immune response, thus delaying viral clearance (phase 3), especially in patients with other comorbidities.17 Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 can escape the pathways of innate immunity through several mechanisms. SARS-CoV-2 components such as Nsp13, Nsp15, and Orf9b can impair the activation of the IFN-1 pathway, inducing resistance against the host immune response.18 To evade pattern recognition receptors , SARS-CoV-2 modifies and shields its replicating RNA, through the processes of guanosine-capping, methylation, and/or other mechanisms.19, 20, 21 Additional strategies to escape innate immunity are related to the interaction between viral proteins and signaling mediators of the TLR/retinoic acid–inducible gene I–like receptor pathways, such as TANK-binding kinase 1 (TRAF-associated NF-κB activator) and interferon regulatory factor 3, which results in an inhibition of signal transduction.18 The escape from innate immunity receptors leads to an impaired production of IFN-I, which has been shown to be lower in patients with severe disease.22 Nevertheless, in patients with severe disease, a higher plasma concentration of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-2, IL-7, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α, was found.23 This cytokine storm is caused by the massive recruitment of monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils from the bloodstream to the site of infection, eliciting an excessive and poorly controlled inflammatory response and tissue damage/systemic inflammation.24 , 25 Another mechanism implicated in the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection is represented by the antibody-dependent enhancement. Antibody-dependent enhancement is due to the presence of low-affinity IgG antibodies, which are unable to eliminate the virus and facilitate its entry into the cell. The antibody/S protein complex binds to the Fc receptor on monocytes/macrophages and to alveolar epithelial cells, favoring the entry of the virus in the cell.3 , 26 , 27 This mechanism also elicits a proinflammatory response.

The cytokine storm

Cytokine storm is frequent in severe COVID-19 cases and leads to the development of ARDS, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and multiorgan failure, increasing infection-associated mortality. It is characterized by unremitting high fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, hyperferritinemia, hemodynamic instability, cytopenia, and abnormalities of the central nervous system with a frequent progression toward multiorgan failure.28, 29, 30, 31, 32 This condition has been described in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, where the mutation of genes involved in the granule release hinders cytotoxic activity of NK and CD8+ T cells or in other forms of congenital immune deficiencies when a failure of viral clearance occurs.33 Under these conditions, the ineffective clearance of the antigenic stimuli leads to macrophages and TH1 cells hyperactivation with excessive secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, in particular IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10, which amplify the typical cytokine storm hyperinflammatory state.34 , 35 Endothelial activation mediated by IL-6 and IFN-γ is involved in the pathogenesis of cytokine storm, contributing to hemodynamic instability, capillary leak, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.36 Endothelial cells are stimulated to produce von Willebrand factor and angiopoietin-II, as well as IL-6 itself, leading to a hypercoagulability status.37

Predictors of worse outcome

Lymphopenia is considered a criterion of severity. In patients with severe COVID-19, T cells and NK cells are usually low, while B cells are at the lower levels of the normal range.23 , 38, 39, 40 In severe cases, significant reduction of regulatory T cells, causing T-cell dysregulation and hyperinflammation, may be observed.39 , 40 Lymphocyte subsets express an exhausted phenotype as suggested by the high level of expression of programmed death 1 and NK group 2 members A, on CD4 T cells and CD8 T cells, respectively.41 , 42 Different mechanisms may explain lymphopenia including increased apoptosis, pyroptosis induced by IL-1β,43 , 44 direct infection of lymphocytes through CD147 protein,45 bone marrow suppression during cytokine storm, and pulmonary sequestration. Cytokine excess, particularly IL-6, induces Fas-mediated T-cell apoptosis.46 Severe patients also have higher specific IgM and IgG titers.17 Finally, hospitalized patients manifest significantly increased levels of C-reactive protein, D-dimer, and procalcitonin, when compared with patients with mild pathology.47

COVID-19 in Children

Children have a limited role in COVID-19 pandemic.48 , 49 As of June 2021, in the United States, children account for approximately 14% of laboratory-confirmed cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.50 In the early phases of the outbreak, children were rarely tested for the virus because symptoms of COVID-19 are usually less severe and most cases are asymptomatic or show mild to moderate clinical features.1 , 6 , 24 , 27 , 40 , 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78 In September and October, the case notification rate increased rapidly and so did the number of pediatric cases as compared with the start of the pandemic79; however, percentages of pediatric cases remain far below those of adults.80

Children have higher probability to have extrarespiratory symptoms81 as diarrhea and vomiting. The case-fatality rate for children and adolescents in Europe is less than 1%, thus confirming that children may also experience a severe course of disease. In a meta-analysis grouping more than 1000 children younger than 5 years, 43% were asymptomatic and 7% required intensive care unit (ICU) admission.82 Risk factors for a worse outcome in children are age younger than 1 month, male sex, presence of lower respiratory tract infection signs or symptoms at presentation, and presence of a preexisting medical condition.79 Children with viral coinfection were more likely to require ICU support.79

Children may also experience severe multisystem inflammation with clinical features in common with Kawasaki disease and toxic shock syndrome. It can be associated with actual or previous positivity to SARS-CoV-2.83 This syndrome has been recently named multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C).84, 85, 86, 87 The main clinical features of MIS-C include fever, gastrointestinal features, cardiovascular symptoms, and mucocutaneous alterations. Inflammatory markers in this syndrome are significantly increased.84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90 Even though MIS-C has been initially confused with Kawasaki disease, difference exists between these 2 entities. In particular, in MIS-C, patients show higher levels of C-reactive protein, neutrophils, ferritin, troponin, D-dimer, and lower platelets levels. Moreover, in patients with MIS-C, the prevalence of myocarditis and shock is higher.87 , 91 Patients developing MIS-C usually have a positive SARS-CoV-2 serology although RT-PCR test results for SARS-CoV-2 are usually negative, proving that MIS-C is a postinfectious inflammatory process.89 , 92

COVID-19 in Immune Compromised Patients

Inborn errors of immunity

Inborn errors of immunity (IEIs) are listed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as risk factors for severe COVID-19. However, evidence of the actual impact of different IEIs on infection is limited, especially in the pediatric population. In a small case series on 7 patients with primary antibody deficiencies and COVID-19, a different clinical outcome between patients with common variable immune deficiency and patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia was reported, the latter having a mild disease. The authors hypothesized that B lymphocytes might enhance the inflammatory response against the virus through the release of IL-6, while an increased risk of relapse may be hypothesized because of the absence of antibodies.93 , 94 The authors also argue in favor of an indirect advantage for patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia provided by the lack of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase. In myeloid/macrophage cells, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase is, indeed, responsible for the production of cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6,95 and for the activation of NOD-like receptor pyrin domain-containing 3 inflammasome with the secretion of IL-1β.96 In an off-label clinical study on 19 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and severe hypoxia, who received a selective Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor, acalabrutinib, normalization of laboratory markers and improved oxygenation was observed after the treatment.97

A retrospective study conducted on a cohort of 94 patients, median age 25 to 34 years, with SARS-CoV-2 infection and IEI including antibody deficiency, innate immune defect, combined immunodeficiency, phagocyte defect, immune dysregulation syndrome, autoinflammatory disorders, and bone marrow failure showed that more than half the subjects were managed as inpatients while a mild clinical picture was observed in more than 30% of patients. Asymptomatic or mild clinical picture was observed in patients affected with X-linked agammaglobulinemia or ZAP70, PGM3, and STAT3. Similar to the general population, a male predominance was noted, not only for infection incidence but also for ICU admission. Also, the association between preexisting risk factors (eg, kidney, lung, or heart disease, diabetes, and obesity) and severe COVID-19 mirrored the general population.1 , 23 However, the authors underlined the younger age of severely affected patients and an increased ICU admission rate in IEI.98 In a recent study on patients affected with IEI or symptomatic secondary immune deficiency, authors found higher morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 among adult patients, when compared with the general population and survival of all the pediatric patients.99 In a retrospective study in Israel, only 20 of 1000 patients with IEI experienced COVID-19, all displaying a mild disease course, without need of hospitalization and 35% were even asymptomatic.100 In a study on an Italian cohort, a total of 131 cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection were notified among 3263 patients with IEI, including adult and pediatric patients. The outcome was similar to what was previously reported. In addition, we described a longer duration of viral shedding among patients with humoral immunodeficiencies.101

However, defects at 8 loci implicated in the TLR3- and interferon regulatory factor 7–dependent IFN-I immunity were identified in 23 of 659 patients presenting with life-threatening COVID-19 pneumonia.102

In this scenario, the identification in 3 patients with autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome type I who suffered from life-threatening COVID-19 pneumonia of anti–IFN-I autoantibodies paved the way to investigating the impact of these neutralizing autoantibodies.103 Bastard et al104 compared anti–IFN-I autoantibodies among patients with either critical or asymptomatic/mild disease and healthy controls. In the latter group, only 4% were positive, whereas patients with asymptomatic or mild clinical picture were negative. In contrast, high titers of neutralizing anti–IFN-I autoantibodies were found in more than 10% of patients with severe disease, especially men (12.5% vs 2.6% of women), partially contributing to explain the sex bias. One of the women with life-threatening COVID-19 and autoantibodies had X chromosome–linked incontinentia pigmenti.104 Finally, an enhanced IFN signaling leading to an increased immune cell activation was noted in 2 pediatric patients who presented with infection-related Evans syndrome and MIS-C. Next-generation sequencing revealed heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in SOCS1 gene, a negative regulator of type I and type II IFN signaling, unleashing a hyperinflammatory response.105

Secondary immune deficiency

The study of patients with acquired immunodeficiency further confirmed the hypothesis that an immunosuppressive status alone may not be responsible for a worse prognosis. In a systematic review on the impact of immunosuppressive condition on SARS-CoV-2 infection outcome, patients affected with leukemia and patients who had undergone liver transplantation had an overall favorable disease course, as compared with the general population.106 , 107 In a study by D’Antiga,54 in a cohort of 200 pediatric transplant patients, 3 developed SARS-CoV-2 infection, in the absence of pulmonary disease. Therefore, immunosuppression has been proposed by the authors as a protective factor, preventing tissue damage. In addition, similarly to general population, age, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease were identified as risk factors for a worse outcome in immunocompromised hosts. In a small series on 8 immunocompromised patients with COVID-19, symptoms ranged from mild febrile syndrome to moderate respiratory distress requiring oxygen therapy. The cohort included patients who were on hemodialysis or who had undergone solid-organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, on immunosuppressive treatment. In 62% of the cases, their monitoring was performed as outpatients, considering hospitalization only in the presence of respiratory distress or hyperpyrexia. Chemotherapy within a month before COVID-19 diagnosis as well as metastatic disease did not represent a significant risk of severe COVID-19 in patients with cancer, who displayed a mild disease course, as reported by Robilotti et al.108

Different articles focused on COVID-19 infection in patients receiving immunosuppressive medications as treatment for rheumatic or inflammatory diseases. By far, evidence suggests not to withdraw this treatment with no need for dose adjustment unless specific symptoms are present.109, 110, 111 Haberman et al112 reported on a case series of patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease on anticytokine biologic therapy: among them, the incidence of hospitalization did not exceed that of the general population, implying that the use of biologics is not associated with worse COVID-19 outcome.112 Similarly, among 8 children with inflammatory bowel disease diagnosed with COVID-19, a mild infection was noticed, although they were on immunomodulators treatment.113 However, glucocorticoid use at a prednisone-equivalent dose of greater than or equal to 10 mg/d has been associated with an increased odds of hospitalization, in keeping with earlier reports showing an augmented infection risk with a higher dose of glucocorticoids.114 , 115

Patients coinfected with HIV and SARS-CoV-2 displayed clinical, biochemical, and radiological findings that appeared similar to those of the general population with COVID-19, suggesting that similar standard of care should be warranted for both. HIV-positive patients with lower CD4 often have a more severe disease course, higher IL-6 levels, and an increased risk of mortality.116 , 117

Characteristics of immunocompromised patients, with both IEI and acquired immunodeficiency, who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 are collectively summarized in Tables I and II .

Table I.

Main characteristic of patients with IEI and SARS-CoV-2 infection

| IEI type (no. of patients) | Outcome | Note | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CVID (5) XLA (1) ARA (1) |

20% death; mild disease course and favorable outcome in agammaglobulinemic patients in contrast to severe course and need for mechanical ventilation in patients with CVID | Authors speculate on a role of B lymphocytes in virus-induced inflammation | 93,94 |

| APECED (1) | Life-threatening COVID-19 pneumonia needing mechanical ventilation and ICU admission in a patient with anti–type I IFN autoantibodies | Beccuti et al103 speculate on an increased infection risk in patients with adrenal insufficiency, while Bastard et al104 highlighted the contribution of anti–type I IFN autoantibodies to disease outcome | 103,104 |

| PAD (53) CID (14) IDS (9) Autoinflammatory disorder (7) Phagocyte defect (6) Innate immune defect (3) Bone marrow failure (2) |

9% death; mild disease course in 37% of patients. All adult patients who died presented with preexisting comorbidities | Risk factors for severe COVID-19 in patients with IEI mirror those of the general population and IEI itself does not represent an independent risk factor. However, patients with a severe course requiring ICU admission are younger compared with the general population | 98 |

| CVID (23) PAD (12) CID (4) XLA (4) CGD (3) NF-kB deficiency (2) Others (12) |

17% death; 20% infection-fatality ratio, 31.6% case-fatality ratio, 37.5% inpatient mortality in patients with IEIs | Patients with IEIs succumb to COVID-19 at a younger age. Morbidity and mortality in patients with IEI exceed that of the general population | 99 |

| WAS (1) | Mild course in a patient who underwent gene therapy (GT) 5 mo before infection | GT-induced immune reconstitution enabled an adequate response against the infection | 98,118 |

| Good syndrome (1) | Death | Authors hypothesize the role of immune dysfunction or anatomical alterations predisposing the patient to a fatal infection outcome | 119 |

| PAD (1) | Mild disease course treated with supportive measures and no need for ICU admission | 120 | |

| CVID (4) HIGM (4) CID (5) XLA (2) CGD (2) Others (3) |

30% asymptomatic, 65% mild disease course; the whole IEI cohort was treated as outpatient | Authors point out the possible role of social distancing and precautions in determining the mild disease course observed in the cohort | 100 |

| NFKB2 LOF | Life-threatening COVID-19 pneumonia needing mechanical ventilation and ICU admission | Authors emphasize how aggressive management of the consequences of underlying immune dysregulation in the patient enabled his recovery from severe SARS-CoV-2 infection | 121 |

| CID (10) PAD (4) Phagocyte defect (2) IDS (2) Autoinflammatory disorders (1) |

42% death Almost all patients who succumbed were younger than 10 y. All subjects with IEI with SARS-CoV-2 infection were hospitalized |

Authors observed a reverse pattern of age and a 10-fold higher mortality rate in SARS-CoV-2–infected patients with IEIs compared with the population | 122 |

APECED, Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy; ARA, autosomal-recessive agammaglobulinemia; CGD, chronic granulomatous disease; CID, combined immune deficiency; CVID, common variable immune deficiency; HIGM, hyper-IgM syndrome; IDS, immunedysregulation syndrome; NFKB2 LOF, nuclear factor kappa B loss of function; PAD, primary antibody deficiency; XLA, X-linked agammaglobulinemia.

Table II.

Main characteristics of patients with acquired immunodeficiencies and SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Acquired immunodeficiency (no. of patients) | Principal diagnosis (no. of patients) | Outcome (no. of patients) | Note | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prednisolone and mycophenolate mofetil (1) Steroid (1) Chemotherapy (1) |

SLE (1) Nephrotic syndrome (1) Extrarenal rhabdoid tumor (1) |

All recovered without any sequelae | The clinical course after SARS-CoV-2 infection was not different compared with the general population | 123 |

| MTX (1) Canakinumab (3) |

AID (3) FMF (1) |

All recovered without any sequelae | The clinical course after SARS-CoV2 infection was not different compared with the general population | 124 |

| Sirolimus (2) Tacrolimus (1) |

Renal trasplant (3) | Mild course | The clinical course after SARS-CoV-2 infection was not different compared with the general population | 125 |

| Ruxolitinib (1) Methotrexate (1) Prednisone and tacrolimus (2) |

HSCT (1) T-ALL (1) Trasplant kidney/liver (2) |

Secondary HLH (1) | The clinical course after SARS-CoV-2 infection was not different compared with the general population | 126 |

| Chemotherapy (2) | Ewing sarcoma (1) Wilms tumor (1) |

Mild course | Pediatric cancer patients have milder disease compared with adults with malignancies | 127 |

| Cyclosporine and prednisone (2) Prednisone and tacrolimus (1) Tacrolimus and azathioprine (1) |

Heart transplant (4) | Mild course | Young patients have a mild SARS-CoV-2 clinical course | 128 |

| Immunosuppressive chemotherapy (98) | Cancer (leukemia, lymphoma, CSN tumor, solid tumor) (98) | Severe course (17) Mechanical ventilation (7) Death (4) |

Pediatric cancer patients have a higher risk of severe course after SARS-CoV-2 infection compared with the general population, but the risk is lower compared with the adult counterparts | 129 |

| Methotrexate (17) Hydroxychloroquine (8) Oral glucocorticoids (8) TNF inhibitor (38) Other (15) |

Psoriatic arthritis (21) Rheumatoid arthritis (20) Ulcerative colitis (17) Crohn disease (20) Other (9) |

Required hospitalization (14) Admission to intensive care (1) Invasive mechanical ventilation (1) Death (1) |

The clinical course after SARS-CoV-2 infection was not different compared with the general population | 112 |

| Prednisone (12) Immunosoppressive agent (7) |

SLE (17) | Required hospitalization (14) Admission to intensive care (7) Invasive mechanical ventilation (5) Death (4) |

130 | |

| Prednisolone (189) DMARDs (492) |

Rheumatoid arthritis (230) Systemic lupus erythematosus (85) Psoriatic arthritis (74) Axial spondyloarthritis or other spondyloarthritis (48) Vasculitis (44) Sjögren syndrome (28) Other inflammatory arthritis (21) Inflammatory myopathy (20) Gout (19) Systemic sclerosis (16) Polymyalgia rheumatica (12) Other (38) |

Required hospitalization (277) Death (55) |

The clinical course after SARS-CoV-2 infection was not different compared with the general population | 114 |

| HIV (5) | All 5 patients were symptomatic and required hospitalization. Oxygen therapy (2) |

131 | ||

| HIV (5) | Required hospitalization (5) Admission to intensive care (2) Invasive mechanical ventilation (1) |

132 | ||

| HIV (33) | Critical course (8) Required hospitalization (8) Admission to intensive care (6) Invasive mechanical ventilation (4) Death (3) |

The clinical course after SARS-CoV-2 infection was not different compared with the general population | 133 | |

| HIV (38) | Severe course (13) Admission to intensive care (6) Invasive mechanical ventilation (5) Death (2) |

The clinical course after SARS-CoV2 infection was not different compared with the general population | 134 | |

| HIV (88) | Severe course (18) Death (18) |

The clinical course after SARS-CoV2 infection was not different compared with the general population | 135 | |

| HIV (31) | Severe/critical course (28) Mechanical ventilation (8) Death (8) |

The clinical course after SARS-CoV-2 infection was not different compared with the general population | 136 |

AID, Autoinflammatory diseases; CNS, central nervous system; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; FMF, familial Mediterranean fever; MTX, metothrexate; SLE, systemic lupus erythematous; T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Therapeutic Approaches to SARS-CoV-2 in IEI

Therapeutic strategies for the treatment of severe COVID-19 in IEI are not different from those used in the general population. Among the different antiviral drugs, remdesivir is the preferred agent in adults and children. It is a monophosphate prodrug that, once activated to C-adenosine nucleoside triphosphate analogue, binds to viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, prematurely terminating the RNA chain.137 , 138 Based on randomized clinical trials in adult population treated with remdesivir, the Food and Drug Administration authorized its emergency use in pediatric patients with normal renal and liver function also. A phase 2/3 clinical trial (NCT04431453) to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of remdesivir in patients younger than 18 years is underway.139 Alternative options in patients who are not eligible for the treatment with remdesivir or when remdesivir is not available include lopinavir/ritonavir, a Food and Drug Administration–approved protease inhibitor indicated for treatment of HIV.140 , 141 However, recent reports claimed no benefits of this agent in pediatric and adult populations.

A preventive anticoagulant therapy with subcutaneous enoxaparin may be considered for patients in whom a higher incidence of thrombotic complications has been observed.142 Since the beginning of the pandemic, chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine have emerged as potential drugs for their supposed antiviral and immunomodulatory effects and their use was initially approved by the Food and Drug Administration.143 , 144 Recently, because of safety concerns regarding high risk for arrhythmias and QT-interval prolongation outweighing the limited evidence of its efficacy, National Institutes of Health guidelines have recommended against these drugs.145 A progressive deterioration of respiratory function and a marked increasing trend of IL-6 and/or D-Dimer and/or ferritin and/or C-reactive protein may suggest adding immunomodulatory agents. As for the use of glucocorticoids, preliminary results of the controlled multicenter clinical trial Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) support the use of dexamethasone in patients needing ventilatory assistance, reducing mortality.146 Thus, dexamethasone 0.2 to 0.4 mg/kg (maximum 6 mg) in patients requiring oxygen may be considered. Also, methylprednisolone, at either low or high dose up to 30 mg/kg, has been associated with a decrease in death risk among patients experiencing deteriorating clinical conditions such as ARDS.147 The main limitations to the use of corticosteroids in COVID-19 are the potential delayed viral clearance, the increased risk of secondary infections,148 and the possible complications.149 However, treatment stopping is not needed in patients with other underlying conditions. Other immunomodulatory agents are being evaluated for their potential roles in the context of hyperinflammatory syndrome due to cytokine release including convalescent plasma, intravenous immunoglobulins, anakinra, tocilizumab, and Janus Kinase (JAK) inhibitors. Anakinra is a nonglycosylated human IL-1 receptor antagonist, acting against proinflammatory cytokines IL-1α and -1β, that reduces both need for intensive care and mortality among patients with COVID-19 severe forms.150 Although preclinical data and observational studies support treatment with tocilizumab, no randomized controlled trial has proved, so far, the effectiveness or the safety of this biologic drug in COVID-19.151 In keeping with available, yet inconclusive data, National Institutes of Health guidelines recommend against its use. Convalescent plasma has displayed some efficacy in reducing inflammatory markers, pulmonary lesions, and mortality. However, only case reports of few critically ill adults and 1 pediatric patient are available.

Conclusions

The outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection in both adult and pediatric patients mainly depends on underlying risk factors including older age, male sex, obesity, and preexisting comorbidities such as chronic lung disease.

Recent studies suggest that IEIs do not represent an independent risk factor for severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, a severe disease course leading to ICU admission or death has been documented at a younger age in patients affected with specific IEI compared with the general population, suggesting a role for selected branches of the immune system in the response to SARS-CoV-2. Similarly, secondary immunosuppression does not significantly impact the disease outcome. However, several aspects of this novel infection in the immunocompromised host still remain to be clarified. For example, especially in patients suffering from humoral immune defects, it is necessary to clarify the viral load kinetics and duration of viral shedding, whether the virus may persist and establish a state of chronic infection, the risk of reinfection, and the effectiveness of active immune-prophylaxis. Further studies on larger populations, with longer follow-up, are needed to deal with these unanswered questions.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui J., Li F., Shi Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang C., Gu J., Chen Q., Deng N., Li J., Huang L. Clinical characteristics of 34 children with coronavirus disease-2019 in the west of China: a multiple-center case series [preprint published online March 16, 2020] medRxiv. [DOI]

- 4.Zhang T., Wu Q., Zhang Z. Probable pangolin origin of SARS-CoV-2 associated with the COVID-19 outbreak. Curr Biol. 2020;30:1346–1351.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu X., Zhang L., Du H., Zhang J., Li Y.Y., Qu J. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1663–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Z., Tomlinson A.C., Wong A.H., Zhou D., Desforges M., Talbot P.J. The human coronavirus HCoV-229E S-protein structure and receptor binding. Elife. 2019;8:e51230. doi: 10.7554/eLife.51230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang T., Bidon M., Jaimes J.A., Whittaker G.R., Daniel S. Coronavirus membrane fusion mechanism offers a potential target for antiviral development. Antiviral Res. 2020;178:104792. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sungnak W., Huang N., Bécavin C., Berg M., Queen R., Litvinukova M. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat Med. 2020;26:681–687. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0868-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann M., Schroeder S., Kleine-Weber H., Müller M.A., Drosten C., Pöhlmann S. Nafamostat mesylate blocks activation of SARS-CoV-2: new treatment option for COVID-19. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e00754-20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00754-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conti P., Caraffa A., Gallenga C.E., Ross R., Kritas S.K., Frydas I. Coronavirus-19 (SARS-CoV-2) induces acute severe lung inflammation via IL-1 causing cytokine storm in COVID-19: a promising inhibitory strategy. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020;34:1971–1975. doi: 10.23812/20-1-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deftereos S.G., Siasos G., Giannopoulos G., Vrachatis D.A., Angelidis C., Giotaki S.G. The Greek study in the effects of colchicine in COvid-19 complications prevention (GRECCO-19 study): rationale and study design. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2020;61:42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.hjc.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jansen J.M., Gerlach T., Elbahesh H., Rimmelzwaan G.F., Saletti G. Influenza virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell-mediated immunity induced by infection and vaccination. J Clin Virol. 2019;119:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2019.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long Q.X., Tang X.J., Shi Q.L., Li Q., Deng H.J., Yuan J. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Med. 2020;26:1200–1204. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0965-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Florindo H.F., Kleiner R., Vaskovich-Koubi D., Acúrcio R.C., Carreira B., Yeini E. Immune-mediated approaches against COVID-19. Nat Nanotechnol. 2020;15:630–645. doi: 10.1038/s41565-020-0732-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azkur A.K., Akdis M., Azkur D., Sokolowska M., van de Veen W., Brüggen M.C. Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and mechanisms of immunopathological changes in COVID-19. Allergy. 2020;75:1564–1581. doi: 10.1111/all.14364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon D.E., Jang G.M., Bouhaddou M., Xu J., Obernier K., O’Meara M.J. A SARS-CoV-2-human protein-protein interaction map reveals drug targets and potential drug-repurposing. Nature. 2020;583:459–468. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouvet M., Debarnot C., Imbert I., Selisko B., Snijder E.J., Canard B. In vitro reconstitution of SARS-coronavirus mRNA cap methylation. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000863. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y., Cai H., Pan J., Xiang N., Tien P., Ahola T. Functional screen reveals SARS coronavirus nonstructural protein nsp14 as a novel cap N7 methyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3484–3489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808790106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivanov K.A., Thiel V., Dobbe J.C., van der Meer Y., Snijder E.J., Ziebuhr J. Multiple enzymatic activities associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus helicase. J Virol. 2004;78:5619–5632. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5619-5632.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadjadj J., Yatim N., Barnabei L., Corneau A., Boussier J., Smith N. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Science. 2020;369:718–724. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su L., Ma X., Yu H., Zhang Z., Bian P., Han Y. The different clinical characteristics of corona virus disease cases between children and their families in China—the character of children with COVID-19. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:707–713. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1744483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu L., Wei Q., Lin Q., Fang J., Wang H., Kwok H. Anti-spike IgG causes severe acute lung injury by skewing macrophage responses during acute SARS-CoV infection. JCI Insight. 2019;4:e123158. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.123158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qian G., Yang N., Ma A.H.Y., Wang L., Li G., Chen X. COVID-19 transmission within a family cluster by presymptomatic carriers in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:861–862. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behrens E.M., Koretzky G.A. Review: Cytokine storm syndrome: looking toward the precision medicine era. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:1135–1143. doi: 10.1002/art.40071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen H., Wang F., Zhang P., Zhang Y., Chen Y., Fan X. Management of cytokine release syndrome related to CAR-T cell therapy. Front Med. 2019;13:610–617. doi: 10.1007/s11684-019-0714-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chousterman B.G., Swirski F.K., Weber G.F. Cytokine storm and sepsis disease pathogenesis. Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39:517–528. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0639-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A., Gödel P., Subklewe M., Stemmler H.J., Schlößer H.A., Schlaak M. Cytokine release syndrome. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:56. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0343-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murthy H., Iqbal M., Chavez J.C., Kharfan-Dabaja M.A. Cytokine release syndrome: current perspectives. Immunotargets Ther. 2019;8:43–52. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S202015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Filipovich A.H., Chandrakasan S. Pathogenesis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2015;29:895–902. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carter S.J., Tattersall R.S., Ramanan A.V. Macrophage activation syndrome in adults: recent advances in pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019;58:5–17. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Billiau A.D., Roskams T., Van Damme-Lombaerts R., Matthys P., Wouters C. Macrophage activation syndrome: characteristic findings on liver biopsy illustrating the key role of activated, IFN-gamma-producing lymphocytes and IL-6- and TNF-alpha-producing macrophages. Blood. 2005;105:1648–1651. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hay K.A., Hanafi L.A., Li D., Gust J., Liles W.C., Wurfel M.M. Kinetics and biomarkers of severe cytokine release syndrome after CD19 chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell therapy. Blood. 2017;130:2295–2306. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-06-793141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gust J., Hay K.A., Hanafi L.A., Li D., Myerson D., Gonzalez-Cuyar L.F. Endothelial activation and blood-brain barrier disruption in neurotoxicity after adoptive immunotherapy with CD19 CAR-T cells. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:1404–1419. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y., Zhang J., Huang L., Zhang C. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qin C., Zhou L., Hu Z., Zhang S., Yang S., Tao Y. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:762–768. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qiu H., Wu J., Hong L., Luo Y., Song Q., Chen D. Clinical and epidemiological features of 36 children with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Zhejiang, China: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:689–696. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30198-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahn J.Y., Sohn Y., Lee S.H., Cho Y., Hyun J.H., Baek Y.J. Use of convalescent plasma therapy in two COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e149. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng H.Y., Zhang M., Yang C.X., Zhang N., Wang X.C., Yang X.P. Elevated exhaustion levels and reduced functional diversity of T cells in peripheral blood may predict severe progression in COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:541–543. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0401-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qu R., Ling Y., Zhang Y.H., Wei L.Y., Chen X., Li X.M. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with prognosis in patients with coronavirus disease-19. J Med Virol. 2020;92:1533–1541. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tay M.Z., Poh C.M., Rénia L. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:363–374. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang K., Chen W., Zhang Z., Deng Y., Lian J.Q., Du P. CD147-spike protein is a novel route for SARS-CoV-2 infection to host cells. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:283. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00426-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feng Z., Diao B., Wang R., Wang G., Wang C., Tan Y. The novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) directly decimates human spleens and lymph nodes [preprint published online March 31, 2020]. medRxiv. [DOI]

- 47.Ko J.H., Park G.E., Lee J.Y., Lee J.Y., Cho S.Y., Ha Y.E. Predictive factors for pneumonia development and progression to respiratory failure in MERS-CoV infected patients. J Infect. 2016;73:468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ladhani S.N., Amin-Chowdhury Z., Davies H.G., Aiano F., Hayden I., Lacy J. COVID-19 in children: analysis of the first pandemic peak in England. Arch Dis Child. 2020;105:1180–1185. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Demographic trends of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the US reported to CDC. Accessed March 1, 2021. www.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/index.html#demographics.

- 51.Xing Y.H., Ni W., Wu Q., Li W.J., Li G.J., Wang W.D. Prolonged viral shedding in feces of pediatric patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang X.F., Yuan J., Zheng Y.J., Chen J., Bao Y.M., Wang Y.R. [Retracted: Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 34 children with 2019 novel coronavirus infection in Shenzhen] Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;58:E008. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2020.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang D., Ju X.L., Xie F., Lu Y., Li F.Y., Huang H.H. Clinical analysis of 31 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in children from six provinces (autonomous region) of northern China [in Chinese] Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;58:269–274. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112140-20200225-00138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.D’Antiga L. Coronaviruses and immunosuppressed patients: the facts during the third epidemic. Liver Transpl. 2020;26:832–834. doi: 10.1002/lt.25756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xia W., Shao J., Guo Y., Peng X., Li Z., Hu D. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID-19 infection: different points from adults. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55:1169–1174. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feng K., Yun Y.X., Wang X.F., Yang G.D., Zheng Y.J., Lin C.M. Analysis of CT features of 15 children with 2019 novel coronavirus infection [in Chinese] Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;58:275–278. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112140-20200210-00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu Y., Li X., Zhu B., Liang H., Fang C., Gong Y. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat Med. 2020;26:502–505. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu H., Liu F., Li J., Zhang T., Wang D., Lan W. Clinical and CT imaging features of the COVID-19 pneumonia: focus on pregnant women and children. J Infect. 2020;80:e7–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li W., Cui H., Li K., Fang Y., Li S. Chest computed tomography in children with COVID-19 respiratory infection. Pediatr Radiol. 2020;50:796–799. doi: 10.1007/s00247-020-04656-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ji L.N., Chao S., Wang Y.J., Li X.J., Mu X.D., Lin M.G. Clinical features of pediatric patients with COVID-19: a report of two family cluster cases. World J Pediatr. 2020;16:267–270. doi: 10.1007/s12519-020-00356-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou Y., Yang G.D., Feng K., Huang H., Yun Y.X., Mou X.Y. Clinical features and chest CT findings of coronavirus disease 2019 in infants and young children [in Chinese] Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;22:215–220. doi: 10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Park J.Y., Han M.S., Park K.U., Kim J.Y., Choi E.H. First pediatric case of coronavirus disease 2019 in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e124. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu Y., Yang Y., Zhang C., Huang F., Wang F., Yuan J. Clinical and biochemical indexes from 2019-nCoV infected patients linked to viral loads and lung injury. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63:364–374. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1643-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chan J.F., Yuan S., Kok K.H., To K.K., Chu H., Yang J. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cai J.H., Wang X.S., Ge Y.L., Xia A.M., Chang H.L., Tian H. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in children in Shanghai [in Chinese] Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;58:86–87. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen F., Liu Z.S., Zhang F.R., Xiong R.H., Chen Y., Cheng X.F. First case of severe childhood novel coronavirus pneumonia in China [in Chinese] Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;58:179–182. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2020.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kam K.Q., Yung C.F., Cui L., Tzer Pin Lin R., Mak T.M., Maiwald M. A well infant with coronavirus disease 2019 with high viral load. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:847–849. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang G.X., Zhang A.M., Huang L., Cheng L.Y., Liu Z.X., Peng X.L. Twin girls infected with SARS-CoV-2 [in Chinese] Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2020;22:221–225. doi: 10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wei M., Yuan J., Liu Y., Fu T., Yu X., Zhang Z.J. Novel coronavirus infection in hospitalized infants under 1 year of age in China. JAMA. 2020;323:1313–1314. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shen K.L., Yang Y.H. Diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in children: a pressing issue. World J Pediatr. 2020;16:219–221. doi: 10.1007/s12519-020-00344-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lou X.X., Shi C.X., Zhou C.C., Tian Y.S. Three children who recovered from novel coronavirus 2019 pneumonia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2020;56:650–651. doi: 10.1111/jpc.14871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tang A., Tong Z.D., Wang H.L., Dai Y.X., Li K.F., Liu J.N. Detection of novel coronavirus by RT-PCR in stool specimen from asymptomatic child, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1337–1339. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li Y., Guo F., Cao Y., Li L., Guo Y. Insight into COVID-2019 for pediatricians. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55:E1–E4. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pan X., Chen D., Xia Y., Wu X., Li T., Ou X. Asymptomatic cases in a family cluster with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:410–411. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30114-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang H., Kang Z., Gong H., Xu D., Wang J., Li Z. The digestive system is a potential route of 2019-nCov infection: a bioinformatics analysis based on single-cell transcriptomes [preprint published online January 31, 2020]. bioRxiv. [DOI]

- 76.Shen Q., Guo W., Guo T., Li J., He W., Ni S. Novel coronavirus infection in children outside of Wuhan, China. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55:1424–1429. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coronavirus disease 2019 in Children—United States, February 12-April 2, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:422–426. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Parri N., Lenge M., Buonsenso D. Children with Covid-19 in pediatric emergency departments in Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:187–190. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Götzinger F., Santiago-García B., Noguera-Julián A., Lanaspa M., Lancella L., Calò Carducci F.I. COVID-19 in children and adolescents in Europe: a multinational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:653–661. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30177-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Borrelli M., Corcione A., Castellano F., Fiori Nastro F., Santamaria F. Coronavirus disease 2019 in children. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:668484. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.668484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zimmermann P., Curtis N. Coronavirus infections in children including COVID-19: an overview of the epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and prevention options in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:355–368. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bhuiyan M.U., Stiboy E., Hassan M.Z., Chan M., Islam M.S., Haider N. Epidemiology of COVID-19 infection in young children under five years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2021;39:667–677. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.11.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schroeder A.R., Wilson K.M., Ralston S.L. COVID-19 and Kawasaki disease: finding the signal in the noise. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10:e1–e3. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-000356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Riphagen S., Gomez X., Gonzalez-Martinez C., Wilkinson N., Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1607–1608. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Belhadjer Z., Méot M., Bajolle F., Khraiche D., Legendre A., Abakka S. Acute heart failure in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in the context of global SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Circulation. 2020;142:429–436. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Toubiana J., Poirault C., Corsia A., Bajolle F., Fourgeaud J., Angoulvant F. Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children during the covid-19 pandemic in Paris, France: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2020;369:m2094. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Verdoni L., Mazza A., Gervasoni A., Martelli L., Ruggeri M., Ciuffreda M. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki-like disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1771–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31103-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Whittaker E., Bamford A., Kenny J., Kaforou M., Jones C.E., Shah P. Clinical characteristics of 58 children with a pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2020;324:259–269. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dufort E.M., Koumans E.H., Chow E.J., Rosenthal E.M., Muse A., Rowlands J. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children in New York State. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:347–358. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Feldstein L.R., Rose E.B., Horwitz S.M., Collins J.P., Newhams M.M., Son M.B.F. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shulman S.T. Pediatric coronavirus disease-2019-associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2020;9:285–286. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Viner R.M., Whittaker E. Kawasaki-like disease: emerging complication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1741–1743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31129-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Quinti I., Lougaris V., Milito C., Cinetto F., Pecoraro A., Mezzaroma I. A possible role for B cells in COVID-19? Lesson from patients with agammaglobulinemia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:211–213.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Soresina A., Moratto D., Chiarini M., Paolillo C., Baresi G., Focà E. Two X-linked agammaglobulinemia patients develop pneumonia as COVID-19 manifestation but recover. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020;31:565–569. doi: 10.1111/pai.13263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Page T.H., Urbaniak A.M., Espirito Santo A.I., Danks L., Smallie T., Williams L.M. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase regulates TLR7/8-induced TNF transcription via nuclear factor-κB recruitment. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;499:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.03.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu X., Pichulik T., Wolz O.O., Dang T.M., Stutz A., Dillen C. Human NACHT, LRR, and PYD domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activity is regulated by and potentially targetable through Bruton tyrosine kinase. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:1054–1067.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Roschewski M., Lionakis M.S., Sharman J.P., Roswarski J., Goy A., Monticelli M.A. Inhibition of Bruton tyrosine kinase in patients with severe COVID-19. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eabd0110. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abd0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Meyts I., Bucciol G., Quinti I., Neven B., Fischer A., Seoane E. Coronavirus disease 2019 in patients with inborn errors of immunity: an international study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:520–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shields A.M., Burns S.O., Savic S., Richter A.G. COVID-19 in patients with primary and secondary immunodeficiency: the United Kingdom experience. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:870–875.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.12.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Marcus N., Frizinsky S., Hagin D., Ovadia A., Hanna S., Farkash M. Minor clinical impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with primary immunodeficiency in Israel. Front Immunol. 2020;11:614086. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.614086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Milito C., Lougaris V., Giardino G., Punziano A., Vultaggio A., Carrabba M. Clinical outcome, incidence, and SARS-CoV-2 infection-fatality rates in Italian patients with inborn errors of immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:2904–2906.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang Q. Human genetics of life-threatening influenza pneumonitis. Hum Genet. 2020;139:941–948. doi: 10.1007/s00439-019-02108-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Beccuti G., Ghizzoni L., Cambria V., Codullo V., Sacchi P., Lovati E. A COVID-19 pneumonia case report of autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type 1 in Lombardy, Italy: letter to the editor. J Endocrinol Invest. 2020;43:1175–1177. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01323-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bastard P., Rosen L.B., Zhang Q., Michailidis E., Hoffmann H.H., Zhang Y. Autoantibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science. 2020;370:eabd4585. doi: 10.1126/science.abd4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lee P.Y., Platt C.D., Weeks S., Grace R.F., Maher G., Gauthier K. Immune dysregulation and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) in individuals with haploinsufficiency of SOCS1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:1194–1200.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Guan J., Wei Y., Zhao Y., Chen F. Modeling the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 epidemic: a systematic review. J Biomed Res. 2020;34:422–430. doi: 10.7555/JBR.34.20200119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Minotti C., Tirelli F., Barbieri E., Giaquinto C., Donà D. How is immunosuppressive status affecting children and adults in SARS-CoV-2 infection? A systematic review. J Infect. 2020;81:e61–e66. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Robilotti E.V., Babady N.E., Mead P.A., Rolling T., Perez-Johnston R., Bernardes M. Determinants of COVID-19 disease severity in patients with cancer. Nat Med. 2020;26:1218–1223. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0979-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Koker O., Demirkan F.G., Kayaalp G., Cakmak F., Tanatar A., Karadag S.G. Does immunosuppressive treatment entail an additional risk for children with rheumatic diseases? A survey-based study in the era of COVID-19. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40:1613–1623. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04663-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Monti S., Montecucco C. The conundrum of COVID-19 treatment targets: the close correlation with rheumatology. Response to: ‘Management of rheumatic diseases in the time of covid-19 pandemic: perspectives of rheumatology practitioners from India’ by Gupta et al and ‘Antirheumatic agents in covid-19: is IL-6 the right target?’ by Capeechi et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:e3. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Filocamo G., Minoia F., Carbogno S., Costi S., Romano M., Cimaz R. Absence of severe complications from SARS-CoV-2 infection in children with rheumatic diseases treated with biologic drugs. J Rheumatol. 2021;48:1343–1344. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.200483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Haberman R., Axelrad J., Chen A., Castillo R., Yan D., Izmirly P. Covid-19 in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases—case series from New York. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:85–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Marlais M., Wlodkowski T., Vivarelli M., Pape L., Tönshoff B., Schaefer F. The severity of COVID-19 in children on immunosuppressive medication. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4:e17–e18. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30145-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gianfrancesco M., Hyrich K.L., Al-Adely S., Carmona L., Danila M.I., Gossec L. Characteristics associated with hospitalisation for COVID-19 in people with rheumatic disease: data from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician-reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:859–866. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Strangfeld A., Eveslage M., Schneider M., Bergerhausen H.J., Klopsch T., Zink A. Treatment benefit or survival of the fittest: what drives the time-dependent decrease in serious infection rates under TNF inhibition and what does this imply for the individual patient? Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1914–1920. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.151043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Guo W, Ming F, Dong Y, Zhang Q, Zhang X, Mo P. Survey for COVID-19 among HIV/AIDS patients in two districts of Wuhan, China [preprint published online March 4, 2020]. SSRN. 10.2139/ssrn.3550029. [DOI]

- 117.Davies M.A. HIV and risk of COVID-19 death: a population cohort study from the Western Cape Province, South Africa [preprint published online July 3, 2020]. medRxiv. [DOI]

- 118.Cenciarelli S., Calbi V., Barzaghi F., Bernardo M.E., Oltolini C., Migliavacca M. Mild SARS-CoV-2 infection after gene therapy in a child with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome: a case report. Front Immunol. 2020;11:603428. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.603428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Pozzi M.R., Baronio M., Janetti M.B., Gazzurelli L., Moratto D., Chiarini M. Fatal SARS-CoV-2 infection in a male patient with Good’s syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2021;223:108644. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ahanchian H., Moazzen N. COVID-19 in a child with primary antibody deficiency. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:755–758. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Abraham R.S., Marshall J.M., Kuehn H.S., Rueda C.M., Gibbs A., Guider W. Severe SARS-CoV-2 disease in the context of a NF-κB2 loss-of-function pathogenic variant. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:532–544.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Delavari S., Abolhassani H. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on patients with primary immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2021;41:345–355. doi: 10.1007/s10875-020-00928-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.El Dannan H., Al Hassani M., Ramsi M. Clinical course of COVID-19 among immunocompromised children: a clinical case series. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:e237804. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-237804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Welzel T., Samba S.D., Klein R., van den Anker J.N., Kuemmerle-Deschner J.B. COVID-19 in autoinflammatory diseases with immunosuppressive treatment. J Clin Med. 2021;10:605. doi: 10.3390/jcm10040605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Solomon S., Pereira T., Samsonov D. An early experience of COVID-19 disease in pediatric and young adult renal transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 2021;25:e13972. doi: 10.1111/petr.13972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Pérez-Martinez A., Guerra-García P., Melgosa M., Frauca E., Fernandez-Camblor C., Remesal A. Clinical outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection in immunosuppressed children in Spain. Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:967–971. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03793-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pérez-Heras I., Fernandez-Escobar V., Del Pozo-Carlavilla M., Díaz-Merchán R., Valerio-Alonso M.E., Domínguez-Pinilla N. Two cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pediatric oncohematologic patients in Spain. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:1040–1042. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lee H., Mantell B.S., Richmond M.E. Varying presentations of COVID-19 in young heart transplant recipients: a case series. Pediatr Transplant. 2020;24:e13780. doi: 10.1111/petr.13780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Madhusoodhan P.P., Pierro J., Musante J., Kothari P., Gampel B., Appel B. Characterization of COVID-19 disease in pediatric oncology patients: the New York-New Jersey regional experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68:e28843. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Mathian A., Mahevas M., Rohmer J., Roumier M., Cohen-Aubart F., Amador-Borrero B. Clinical course of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a series of 17 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus under long-term treatment with hydroxychloroquine. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:837–839. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ridgway J.P., Farley B., Benoit J.L., Frohne C., Hazra A., Pettit N. A case series of five people living with HIV hospitalized with COVID-19 in Chicago, Illinois. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2020;34:331–335. doi: 10.1089/apc.2020.0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Blanco J.L., Ambrosioni J., Garcia F., Martínez E., Soriano A., Mallolas J. COVID-19 in patients with HIV: clinical case series. Lancet HIV. 2020;7:e314–e316. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30111-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Härter G., Spinner C.D., Roider J., Bickel M., Krznaric I., Grunwald S. COVID-19 in people living with human immunodeficiency virus: a case series of 33 patients. Infection. 2020;48:681–686. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01438-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Vizcarra P., Pérez-Elías M.J., Quereda C., Moreno A., Vivancos M.J., Dronda F. Description of COVID-19 in HIV-infected individuals: a single-centre, prospective cohort. Lancet HIV. 2020;7:e554–e564. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30164-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sigel K., Swartz T., Golden E., Paranjpe I., Somani S., Richter F. Coronavirus 2019 and people living with human immunodeficiency virus: outcomes for hospitalized patients in New York City. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2933–2938. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Shalev N., Scherer M., LaSota E.D., Antoniou P., Yin M.T., Zucker J. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in people living with human immunodeficiency virus hospitalized for coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2294–2297. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Smith E.C., Blanc H., Surdel M.C., Vignuzzi M., Denison M.R. Coronaviruses lacking exoribonuclease activity are susceptible to lethal mutagenesis: evidence for proofreading and potential therapeutics. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003565. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Agostini M.L., Andres E.L., Sims A.C., Graham R.L., Sheahan T.P., Lu X. Coronavirus susceptibility to the antiviral remdesivir (GS-5734) is mediated by the viral polymerase and the proofreading exoribonuclease. mBio. 2018;9:e00221-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00221-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of remdesivir (GS-5734™) in participants from birth to < 18 years of age with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (CARAVAN). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04431453. Updated June 21, 2021. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04431453 Available from: Accessed March 1, 2021.

- 140.Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D., Liu W., Wang J., Fan G. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Venturini E., Montagnani C., Garazzino S., Donà D., Pierantoni L., Lo Vecchio A. Treatment of children with COVID-19: position paper of the Italian Society of Pediatric Infectious Disease. Ital J Pediatr. 2020;46:139. doi: 10.1186/s13052-020-00900-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Jaffray J., Young G. Developmental hemostasis: clinical implications from the fetus to the adolescent. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60:1407–1417. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zhou D., Dai S.M., Tong Q. COVID-19: a recommendation to examine the effect of hydroxychloroquine in preventing infection and progression. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020;75:1667–1670. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Devaux C.A., Rolain J.M., Colson P., Raoult D. New insights on the antiviral effects of chloroquine against coronavirus: what to expect for COVID-19? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105938. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.National Institutes of Health Special considerations in children. 2021. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/special-populations/children/ Available from: Accessed March 1, 2021.

- 146.Horby P., Lim W.S., Emberson J.R., Mafham M., Bell J.L., Linsell L. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]