Abstract

An outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing the carbapenemase NDM-1 occurred in our ICU during the last COVID-19 wave. Twelve patients were tested positive, seven remained asymptomatic whereas 5 developed an infection. Resistome and in silico multilocus sequence typing confirmed the clonal origin of the strains. The identification of a possible environmental reservoir suggested that difficulties in observing optimal bio-cleaning procedures due to workload and exhaustion contributed to the outbreak besides the inappropriate excessive glove use.

Keywords: Carbapenemase, COVID-19, Hospital infection control, Transmission, ICU, Enterobacterales

Since management of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) patients required improved infection prevention with personal protective equipment (PPE) wearing and rigorous environment cleansing and disinfection, strengthened hospital infection control could be expected. Surprisingly, between mid-March and mid-May 2021, during the third COVID-19 pandemic wave in Paris region.1 an outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing the carbapenemase NDM-1 (NDM-1 K. pneumoniae) occurred in our intensive care unit (ICU). Our study objectives were to report the extent and consequences of this outbreak and to discuss its possible origins since it represented the first outbreak involving highly resistant bacteria in our ICU during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

In agreement with the French guidelines, all patients admitted to our intensive care unit (ICU) were screened routinely for carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE) colonization on admission and weekly thereafter with rectal swabs. During the outbreak period, all NDM-1 K. pneumoniae strains isolated in blood cultures, respiratory samples, urinary samples and rectal swabs were sequenced. The whole genome sequencing of all isolates and their genetic relationships was determined as previously described2 and phylogenetic tree was provided by using the Moabi Bio-informatic platform (http://idfseqit.fr).3 In parallel, the Infection Prevention and Control Team of our hospital investigated the practices of caregivers including environmental infection control, hand hygiene, isolation precautions, fiberscope disinfection and medical device management, providing provided day-by-day advices until the outbreak resolution.

Results

Twelve patients in our intensive care unit (ICU) were tested positive for Klebsiella pneumoniae producing the carbapenemase NDM-1 (NDM-1 K. pneumoniae) between mid-March and mid-May 2021 (Table 1 ). Seven patients were asymptomatic carriers while an infection occurred in five patients. Patients with NDM-1 K. pneumoniae were cohorted in an ICU area with dedicated nursing and medical staff.

Table 1.

Characteristics, antibiotic treatment and outcome of the twelve critically ill COVID-19 patients become NDM-1 producing K. pneumoniae carriers

| Patient | Gender, age | Admission room | Culture site | Antibiotic treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | F, 67 | 115 | Respiratory | Meropenem + tigecycline | Alive |

| 2 | F, 58 | 105 | Respiratory | None | Alive |

| 3 | M, 70 | 115 | Respiratory | Meropenem + colistin | Died |

| 4 | M, 54 | 107 | Blood | Ceftazidime/avibactam + aztreonam | Alive |

| 5 | M, 63 | 115 | Blood | Colistin + tigecycline | Alive |

| 6 | M, 26 | 105 | Respiratory | None | Alive |

| 7 | M, 37 | 103 | Rectal | None | Died |

| 8 | M, 64 | 116 | Blood | Ceftazidime/avibactam + aztreonam | Died |

| 9 | M, 67 | 105 | Rectal | None | Died |

| 10 | F, 69 | 116 | Respiratory | None | Died |

| 11 | F, 72 | 104 | Rectal | None | Alive |

| 12 | M, 35 | 115 | Rectal | None | Alive |

Index case.

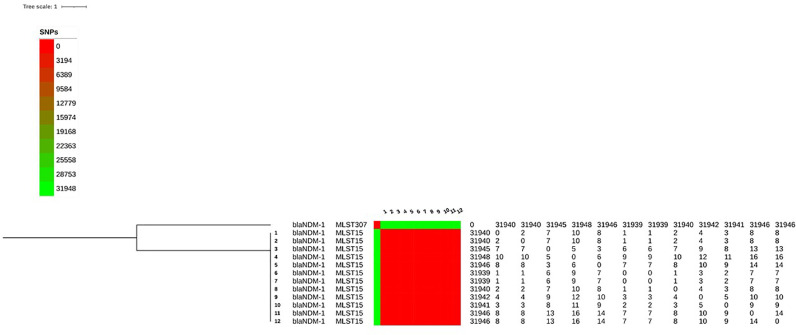

Phylogenetic analyses demonstrated that all strains were related clonally, with less than 16 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within core-genome (Fig 1 ). The resistome of the K. pneumoniae isolates confirmed that all isolates harbored bla NDM-1 gene associated with other beta-lactamase encoding genes (bla TEM-1, bla CTX-M-15, bla OXA-1 and bla CMY-4). Additionally, other determinants conferring resistance to aminoglycosides [aac(6’)-Ib-cr, aac(3)-I, aph(3’)-VI, aph(6’)-I genes], quinolones [S80I mutation in ParC, D87A and S83F mutations in GyrA and acquisition of aac(6’)-Ib-cr, oqxa, oqxB, and qnrB genes], macrolides [mdfA gene], phenicol [floR and cat genes], sulfonamide [sul gene], trimethoprim [dfrA14 gene], tetracycline [tetA gene] and fosfomycin [fosA gene] were detected. In silico Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis revealed that the isolate belonged to the sequence type ST15.

Fig 1.

Phylogenetic tree and sequence types of 12 NDM-1 K. pneumoniae isolates from patients hospitalized in the intensive care unit. The tree is rooted on a K. pneumonia isolate found outside the unit. The phylogenetic tree was built based on 31,973 total core single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) positions using the maximum likelihood method via parSNP. Difference in SNPs is reported between each isolate at the right of the tree.

In parallel, microbiological investigations of the environment revealed the presence of NDM-1 K. pneumoniae on the mattress and in the siphon of a room, where two carriers were identified.

During the outbreak, the Infection Prevention and Control Team of our hospital audited adherence of caregivers to infection control practices. Inappropriate excessive glove use and perfunctory environment hygiene after a patient has left a room were reported. Feedback was given rapidly to the ICU team. Specific measures including strengthening of room and device cleaning, and change of suspect materials were conducted to control NDM-1 K. pneumoniae transmission.

Discussion

In the present study, we report a clonal outbreak of multidrug-resistant K pneumoniae in an ICU already overburdened by a wave of COVID-19 patients. The Infection Prevention and Control team highlighted non-complete compliance with standard and contact precautions.

NDM-1 K. pneumoniae acquisition was likely transmitted from the environment due to the invasive procedures, high antimicrobial selective pressure and immunomodulatory therapy administration in COVID-19 patients, as previously acknowledged.4 Moreover, difficulties in observing and applying optimal bio-cleaning procedures after the prolonged pandemic by exhausted caregivers may have contributed to maintain bacterial reservoir. Transmission between caregivers and patients was facilitated by increased patient density and severity, enhanced workload due to the burden of the disease, and reduced space (e.g., two mechanically ventilated patients managed in rooms routinely dedicated to single patients).

In our ICU, PPE included FFP2-masks, long-sleeved disposable gowns, aprons, goggles and gloves, as recommended internationally.5 Caregivers were encouraged to wear gloves during patient care if contact with blood and other body fluids could be reasonably anticipated. They were advised to carry out hand hygiene systematically with alcohol-based hand rub after removing gloves. However, strengthening PPE wearing and fear of self-contamination by SARS-CoV-2 led the team, especially additional caregivers not trained to manage ICU patients, to wear gloves even if not required. These poor practices such as not changing gloves between two patients likely contributed to the room contamination and cross-transmission between patients.

Based on the MLST findings, our isolate was related to a novel international clone previously associated with multidrug resistance6 and implicated in numerous hospital outbreaks worldwide.7 Interestingly, COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with hospital acquisition of carbapenemase-producing K. pneumonia. 8, 9, 10 In one study, several distinct lineages of carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae were observed suggesting that favoring factors including prolonged critical illness produced an optimal host environment supporting the emergence of diverse CPE.8 The two other studies promoted the continuous use of gloves, which is no longer recommended due to the risk of environmental contamination.9 , 10

Curiously, this outbreak of NDM-1 K. pneumoniae occurred during the third peak of COVID-19 pandemic, more than one year after its start. Burnout, exhaustion and reduced vigilance with rigorous bio-cleaning and hygiene measures may have played a key-role, while caregivers were experienced with the correct use of PPE in adapted situations. Intensive room bio-cleaning was performed and recommendations to improve hand hygiene were provided to caregivers by the IPC team. No further cases occurred.

Conclusions

Although implementation of additional infection control procedures during COVID-19 outbreak was expected to be associated with decrease in healthcare-associated infections, our experience suggests that extra-procedures, which require more attention and time, could exhaust teams and lead to counterproductive effects if prolonged application is required.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Sante Publique France. Coronavirus: chiffres clés et évolution de la COVID-19 en France et dans le Monde. 2020-2021. Available at:https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/dossiers/coronavirus-covid-19/coronavirus-chiffres-cles-et-evolution-de-la-covid-19-en-france-et-dans-le-monde. Accessed June 26, 2021.

- 2.Caméléna F, Morel F, Merimèche M. Genomic characterization of 16S rRNA methyltransferase-producing Escherichia coli isolates from the Parisian area, France. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020;75:1726–1735. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enis A, Dannon B, Marius VDB. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W3–W10. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Connell NH, Humphreys H. Intensive care unit design and environmental factors in the acquisition of infection. J Hosp Infect. 2000;45:255–262. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2000.0768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Rational use of personal protective equipment for COVID-19 and considerations during severe shortages. 2020. Available at:file:///C:/Users/548018/AppData/Local/Temp/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPC_PPE_use-2020.4-eng.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2021.

- 6.Bialek-Davenet S, Criscuolo A, Ailloud F. Genomic definition of hypervirulent and multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal groups. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1812–1820. doi: 10.3201/eid2011.140206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wyres KL, Lam MMC, Holt KE. Population genomics of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18:344–359. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0315-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez-Simmonds A, Annavajhala MK, McConville TH. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales causing secondary infections during the COVID-19 crisis at a New York City hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;76:380–384. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belvisi V, Del Borgo C, Vita S. Impact of SARS CoV-2 pandemic on carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae prevention and control programme: convergent or divergent action? J Hosp Infect. 2021;109:29–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farfour E, Lecuru M, Dortet L. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales outbreak: another dark side of COVID-19. Am J Infect Contr. 2020;48:1533–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]