Brazil is one of the countries most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, with more than 16 million confirmed cases and 454 429 confirmed deaths by May 26, 2021 (according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center). The beginning of 2021 was marked by a second wave of COVID-19, which had different features to the first wave,1 with simultaneous, explosive surges of COVID-19 cases across different regions of the country that added enormous pressure to a health system already under strain after a year of the pandemic. This second wave was contemporary with the discovery, expansion, and dominance of variants of interest (VoI) and variants of concern (VoC) in Brazil.2

We previously characterised the first 250 000 hospital admissions for COVID-19 in Brazil, including resource use and in-hospital mortality of patients.1 We now compare the burden, severity (number of patients with hypoxaemia), resource use (intensive care unit admission and respiratory support), and in-hospital mortality of COVID-19 hospitalised patients between the first and second waves. From the Brazilian nationwide surveillance database for severe acute respiratory infections, SIVEP-Gripe (Sistema de Informação de Vigilância Epidemiológica da Gripe), we extracted 1 217 332 COVID-19 hospital admissions from Feb 16, 2020, to May 24, 2021 (ie, epidemiological week 8, 2020, to epidemiological week 21, 2021). For the quantitative comparison between waves, we extracted data available until May 24, 2021, and excluded the previous four epidemiological weeks to account for a potential delay in notifications appearing on the database, resulting in 1 187 840 hospital admissions (for a link to data sources and additional analyses, see appendix p 1; national and regional comparisons will be updated regularly on the SIVEP COVID-19 Brazil app).

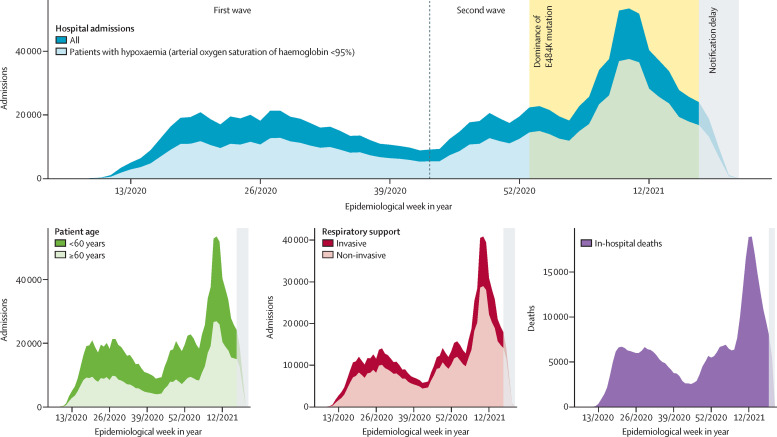

The hospital admission dynamic showed a second surge after epidemiological week 43 in 2020, defined by the lowest value per week of hospitalised cases (figure ). Comparing the first wave with the second wave (ie, comparing the period of weeks 8 to 43 in 2020 vs the period from week 44 in 2020 to week 21 in 2021), average figures per week had increased for admissions by 59% (14 220 vs 22 703; appendix p 1), for patients with hypoxaemia by 72% (8606 vs 14 845), for non-invasive ventilation by 74% (6746 vs 11 773), and for invasive mechanical ventilation by 53% (2452 vs 3747). Remarkably, the maximum number of admitted patients per week requiring advanced respiratory support (ie, non-invasive ventilation, or invasive mechanical ventilation, or both) was 13 985 (week 28 in 2020) in the first wave, which increased by 192% to 40 797 (week 10 in 2021) in the second wave. Although more patients with hypoxaemia received respiratory support in the second wave than in the first wave, there was no increase in the proportion of patients admitted to the intensive care unit (37·6% vs 37·5%), which suggests a potential limitation in access to critical care (appendix p 1). Interestingly, there were fewer admissions from state capitals in the second wave than in the first wave (48·2% vs 37·5%).

Figure.

Temporal increases in COVID-19 hospital admissions and deaths in Brazil, stratified by severity (hypoxaemia), age, and respiratory support

Data are for all hospital admissions (n=1 217 332). The x-axis denotes the epidemiological week when symptom onset occurred for hospital admissions, and week of outcome for in-hospital deaths. The first and second waves are defined by the lowest value per week of hospitalised people with COVID-19 in Brazil (dashed line, epidemiological week 43 in 2020: Oct 18, 2020, to Oct 24, 2020) whereas the yellow area starts after the E484K mutation's dominance (epidemiological week 53 in 2020, Dec 27, 2020, to Jan 02, 2021). The grey area shows a period of uncertainty, particularly for deaths, owing to an expected delay in notifying the SIVEP-Gripe database (data were exported on May 24, 2021).

During the second wave, on May 26, 2021, in epidemiological week 53, Outbreak.info reported that the E484K mutation among SARS-CoV-2 variants in Brazil was present in more than 50% of viral genomes,3 motivating specific comparisons of admissions before and after dominance of VoI or VoC. The median age of patients decreased (63 years vs 59 years), with a relative increase of 18% in the proportion of patients younger than 60 years. The in-hospital mortality increased from 33·1% to 40·6% in the general population, and also in patients who received respiratory support (24·8% vs 28·6% non-invasive ventilation, 78·8% vs 84·1% invasive mechanical ventilation). However, the proportion of deaths should be interpreted with caution because of a substantial number of ongoing admissions (appendix p 1).

Based on the available data of 1 217 332 COVID-19 adult hospitalisations in Brazil, the second wave's progression resulted in an increased burden of severe cases similar to the situation seen in the UK4 and Africa.5 The Brazilian health-care system was overwhelmed during the first wave, and now indicates resource constraints, or even collapse, in a scenario of low adherence to non-pharmacological interventions and convergent dominance of the VoC. However, our research cannot establish a causal relationship between VoC lineages and higher burden of severe cases or increased pathogenicity of the virus. These findings indicate the need for urgent action to contain transmission, expand vaccination coverage, and improve critical care for COVID-19, by providing access to health services and disseminating better available evidence.

LSLB and OTR are joint first authors. LSLB is supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brasil (finance code 001), outside of this work. OTR is funded by a Sara Borrell fellowship (CD19/00110) from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Centro de Excelencia Severo Ochoa 2019–2023 Programme) and the Generalitat de Catalunya (CERCA Programme), outside of this work. TMLS reports grants from the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation Fiocruz Innovation Promotion Programme, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ). SH reports a grant from CNPq outside of this work. FAB reports grants from CNPq and FAPERJ, outside of this work.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Ranzani OT, Bastos LSL, Gelli JGM, et al. Characterisation of the first 250 000 hospital admissions for COVID-19 in Brazil: a retrospective analysis of nationwide data. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:407–418. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30560-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faria NR, Mellan TA, Whittaker C, et al. Genomics and epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science. 2021;372:815–821. doi: 10.1126/science.abh2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wise J. COVID-19: the E484K mutation and the risks it poses. BMJ. 2021;372:n359. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Challen R, Brooks-Pollock E, Read JM, Dyson L, Tsaneva-Atanasova K, Danon L. Risk of mortality in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/1: matched cohort study. BMJ. 2021;372:n579. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salyer SJ, Maeda J, Sembuche S, et al. The first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2021;397:1265–1275. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00632-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.