Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: acute respiratory failure, functional outcomes, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, Pediatric Overall Performance Category, thrombomodulin

OBJECTIVES:

To evaluate the link between early acute respiratory failure and functional morbidity in survivors using the plasma biomarkers interleukin-8, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, thrombomodulin, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. We hypothesized that children with acute respiratory failure with higher levels of inflammation would have worse functional outcomes at discharge, as measured by Pediatric Overall Performance Category.

DESIGN:

Secondary analysis of the Genetic Variation and Biomarkers in Children with Acute Lung Injury (R01HL095410) study.

SETTING:

Twenty-two PICUs participating in the multisite clinical trial, Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure (U01 HL086622) and the ancillary study (Biomarkers in Children with Acute Lung Injury).

SUBJECTS:

Children 2 weeks to 17 years requiring invasive mechanical ventilation for acute airways and/or parenchymal lung disease. Patients with an admission Pediatric Overall Performance Category greater than 3 (severe disability, coma, or brain death) were excluded.

INTERVENTIONS:

None.

MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS:

Among survivors, 387 patients had no worsening of Pediatric Overall Performance Category at discharge while 40 had worsening functional status, defined as any increase in Pediatric Overall Performance Category from baseline. There was no significant relationship between worsening of Pediatric Overall Performance Category and interleukin-8 or plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 on any day. There was no significant relationship between interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, or thrombomodulin, and worsening Pediatric Overall Performance Category on day 1. Plasma interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and thrombomodulin were significantly elevated on days 2 and 3 in those with worse functional status at discharge compared with those without. In multivariable analysis, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and thrombomodulin were associated with a decline in functional status on days 2 and 3 after adjustment for age and highest oxygenation index. However, after adjusting for age and cardiovascular failure, only day 2 thrombomodulin levels were associated with a worsening in Pediatric Overall Performance Category.

CONCLUSIONS:

Higher levels of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist or thrombomodulin following intubation were associated with worse Pediatric Overall Performance Category scores at hospital discharge in children who survive acute respiratory failure. These data suggest that persistent inflammation may be related to functional decline.

Acute respiratory failure is the top diagnosis among children requiring admission to the PICU, with approximately 50% of PICU patients requiring invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation (MV) (1). Survivors often face significant post-discharge morbidity, including a decline in functional status and health-related quality of life (2, 3). Baseline patient characteristics such as age and comorbidities, as well as clinical treatments including sedative medications and duration of MV, have been associated with morbidity following acute respiratory failure (4).

Biomarkers, an objective measurement of a normal or abnormal physiologic state (5), are used in clinical practice and research to improve health through diagnosis, monitoring of response to a therapy, and prediction of outcomes. Within pediatric acute respiratory failure, and in particular pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome (PARDS), plasma biomarkers such as interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) have been associated with presence of PARDS (6). Other markers including interleukin-8 (IL-8), surfactant protein D, and angiopoietin-2 have been associated with mortality (7–9).

To date, we are unaware of any studies that have examined the relationship between inflammatory plasma biomarkers and functional outcomes among children with acute respiratory failure. Thus, our overarching objective was to conduct an exploratory analysis of the relationship between plasma inflammatory biomarkers and change in functional outcome in children with acute respiratory failure using the Genetic Variation and Biomarkers in Children with Acute Lung Injury (BALI) study, which prospectively collected plasma biomarker specimens from children with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure enrolled in the Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure (RESTORE; U01 HL086622) clinical trial (10). Specifically, we examined IL-8, IL-1ra, thrombomodulin, and plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI), which were selected a priori in the parent BALI study. We hypothesized patients with a decline in functional outcome at discharge would have higher plasma biomarker levels compared with those who did not.

METHODS

Study Design

This is a secondary analysis of the BALI study, an ancillary study to the RESTORE trial. Patients age 2 weeks to 17 years requiring invasive MV for acute airways and/or pulmonary parenchymal lung disease were enrolled from 2009 to 2013. Twenty-two of the 31 centers participating in RESTORE participated in BALI (Appendix 1). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (HUM0076118) at all participating sites and informed consent was obtained.

As part of the BALI study, blood samples were collected from patients within 24 hours of consent and again 24 and 48 hours later. Methods were previously published (6). Day of intubation is considered study day 0, irrespective of when consent was obtained. The first sample was obtained as close to consent as possible, with 70% occurring within the first 72 hours. Plasma IL-8, IL-1ra, thrombomodulin, and PAI-1 were measured using two-antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) (IL-8: Number D800C; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; IL-1ra: DRAOOB; R&D Systems; thrombomodulin: ELISA, Asserchrome, Diagnostica Stago, Parsippany, NJ; PAI-1: Number 837 Sekisui Diagnostics, Stamford, CT). The measurements were carried out in duplicate and followed the manufacturer’s protocol. Three-hundred thirty-two patients had at least one sample assayed of the four biomarkers.

Functional status was assessed using the Pediatric Overall Performance Category (POPC) score (11). Baseline (before the acute illness that qualified the patient for participation in RESTORE) and hospital discharge status were determined by study site staff using medical record review (2). POPC scores range from 1 (good), 2 (mild disability), 3 (moderate disability), 4 (severe disability), 5 (vegetative state or coma), and 6 (death). As the goal of our study was to understand the relationship between inflammatory plasma biomarker levels and decline in functional status, patients with a baseline POPC score of 4 or greater (indicating severe disability or coma) were excluded (n = 64). Additionally, we excluded patients who died prior to hospital discharge (n = 47) and patients who did not have a discharge POPC score (n = 11). We were unable to evaluate neurocognitive decline given the small number of patients with a change in Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category (PCPC) score from admission to discharge.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome of this study was worsening of POPC from baseline, which we defined as any increase in the POPC score, as performed in prior studies (2, 12). Thus, we compared the measured biomarker levels (IL-1ra, thrombomodulin, IL-8, and PAI-1) on days 1–3 following intubation between patients who had a worsening of POPC from baseline and patients who did not have a decline in functional status.

Statistical Analysis

Basic descriptive analyses of all clinical and demographic variables, as well as biomarker levels, were conducted comparing patients who had a worsening of POPC from patients who did not using chi-square test, Fisher exact test, or Wilcoxon two-sample test, as indicated.

Multivariable logistic regression models were developed based on the results of the bivariate analysis of the clinical, demographic, and biomarker variables on days 1, 2, or 3 following intubation between outcome groups (i.e., those with worsening of POPC vs those without). In this exploratory investigation, we were unable to include all variables in one single model, and therefore, present separate models to examine pertinent associations due to the limited number of patients with available biomarker samples. Oxygenation index (OI) and cardiovascular failure were included in the analysis as surrogate markers of respiratory failure and hypotension, both of which have been associated with decline in health status (4, 13, 14). To understand the role of illness severity, we examined change in functional outcome adjusting for Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM)-III scores and age. Finally, as biomarkers and functional decline are influenced by systemic inflammation, we accounted for the presence of sepsis by creating multivariable models with biomarker level, age, and sepsis diagnosis (4, 12). Final models examining the association of biomarkers with decline in functional outcome were adjusted for 1) biomarker, age, and highest OI over days 0–3; 2) biomarker level, age, and presence of cardiovascular failure; 3) biomarker, age, and PRISM-III; and 4) biomarker level, age, and sepsis diagnosis. All biomarker levels included in the multivariable models were log-transformed. Of note, if OI was not available, oxygen saturation index was used (15, 16).

RESULTS

Of the 502 survivors of acute respiratory failure enrolled in BALI, 427 patients had a baseline POPC of 3 or less and were included in our analysis. Among the 427, 387 (90.6%) had no change in POPC from baseline, while 40 (9.4%) did.

Overall, the cohort had a median age of 1.9 years (interquartile range [IQR], 0.4–8.7 yr), was 45.4% female, and had a median baseline POPC of 1 (IQR, 1–1) (Table 1). Patients with a worsening of POPC from baseline to discharge were older (6.2 vs 1.7 yr; p < 0.01), had higher PRISM-III scores (11 vs 7; p < 0.01), and longer PICU lengths of stay (16 vs 9.6 d; p < 0.01). Additionally, those with worsening of POPC had higher rates of cardiovascular, hematologic, renal, and hepatic failures during hospitalization and were more likely to have a primary diagnosis of acute respiratory failure due to sepsis (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristics | All (n = 427) | Decline in Functional Status From Baseline (n = 40) | No Decline in Functional Status From Baseline (n = 387) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), yr | 1.9 (0.4–8.7) | 6.2 (1.4–14.3) | 1.7 (0.4–8.2) | < 0.01 |

| Female, n (%) | 194 (45.4) | 19 (47.5) | 175 (45.2) | 0.78 |

| Non-Hispanic, White, n (%) | 218 (51.5) | 22 (57.9) | 196 (50.9) | 0.41 |

| Medical history of, n (%) | ||||

| Prematurity | 58 (13.6) | 5 (12.5) | 53 (13.7) | 0.83 |

| Asthma | 78 (18.3) | 6 (15.0) | 72 (18.6) | 0.57 |

| Seizure disorder | 18 (4.2) | 1 (2.5) | 17 (4.4) | 1.00 |

| Immunodeficiency | 6 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.6) | 1.00 |

| Cancer | 17 (3.9) | 4 (10.0) | 13 (3.4) | 0.06 |

| Chromosomal abnormality | 23 (5.4) | 2 (5.0) | 21 (5.4) | 1.00 |

| Primary diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Pneumonia | 138 (32.3) | 10 (25.0) | 128 (33.1) | 0.30 |

| Bronchiolitis | 105 (24.6) | 5 (12.5) | 100 (25.8) | 0.06 |

| Acute respiratory failure due to sepsis | 69 (16.2) | 13 (32.5) | 56 (14.5) | < 0.01 |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 27 (6.3) | 3 (7.5) | 24 (6.2) | 0.73 |

| Asthma | 53 (12.4) | 3 (7.5) | 50 (12.9) | 0.45 |

| Other | 35 (8.2) | 6 (15.0) | 29 (7.5) | 0.12 |

| Organ failure, n (%) | ||||

| Cardiovascular | 236 (55.3) | 33 (82.5) | 203 (52.5) | < 0.01 |

| Neurologic | 205 (48.0) | 24 (60.0) | 181 (46.8) | 0.11 |

| Hematologic | 91 (21.3) | 19 (47.5) | 72 (18.6) | < 0.01 |

| Hepatic | 120 (28.1) | 28 (70.0) | 92 (23.8) | < 0.01 |

| Renal | 34 (8.0) | 8 (20.0) | 26 (6.7) | < 0.01 |

| Pediatric Risk of Mortality-III, median (IQR) | 8 (3–13) | 11 (8–17.5) | 7 (3–13) | < 0.01 |

| PICU Length of stay, median (IQR), d | 9.9 (6.2–16.7) | 16 (11.0–36.6) | 9.6 (6.0–15.7) | < 0.01 |

| Hospital length of stay, median (IQR), d | 15 (9–26) | 30 (15–51.5) | 14 (9–25) | 0.31 |

| Baseline Pediatric Overall Performance Categorya, median (IQR) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.18 |

| Baseline Pediatric Cerebral Performance Categorya, median (IQR) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | < 0.01 |

| Intervention group, n (%) | 253 (59.4) | 15 (37.5) | 238 (61.7) | 0.31 |

IQR = interquartile range.

aPatients with baseline Pediatric Overall Performance Category or Pediatric Cerebral Performance Category of 4 or greater were excluded.

Of the 427 patients with a POPC of 3 or less, 332 (77.8%) had at least one sample of the biomarkers assayed. The timing of the first biomarker measurement obtained was similar between children with versus without worsening POPC (p = 0.71). There was no difference in patient characteristics between those with versus without available biomarker samples, with the exception of a higher proportion of children with biomarkers assigned to the intervention RESTORE study arm (data not shown).

Association of Plasma Biomarkers With Decline in Overall Functional Status

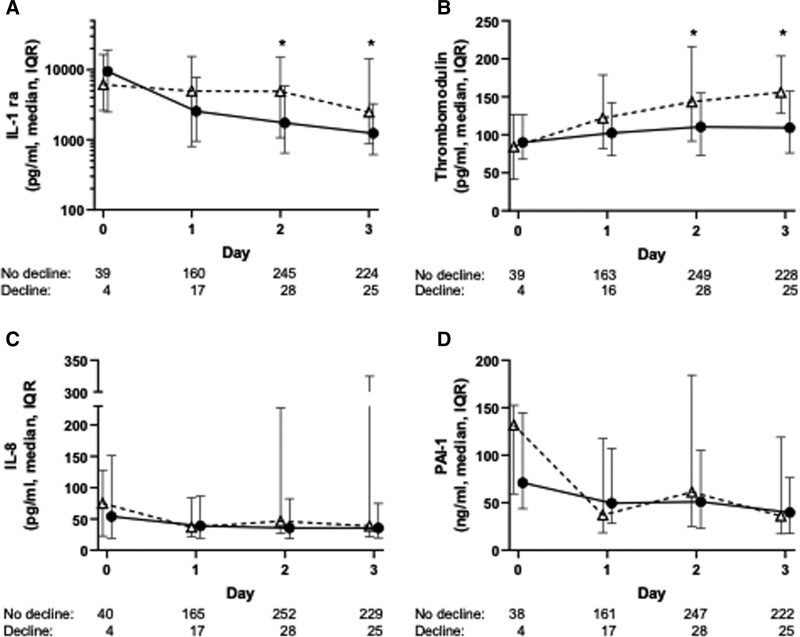

There was no significant relationship between worsening of POPC and IL-8 or PAI-1 on days 1, 2, or 3 following intubation. Similarly, there was no significant relationship between IL-1ra or thrombomodulin and worsening functional status on day 1. However, plasma IL-1ra was significantly elevated on days 2 and 3 in those with worse functional status at discharge compared with those without (day 2: median 4,891 pg/mL [IQR, 1,089–14,600 pg/mL] vs 1,736 pg/mL [IQR, 651–5,794 pg/mL; p = 0.024] and day 3: median 2,490 pg/mL [IQR, 1,007–14,000 pg/mL] vs 1,239 pg/mL [IQR, 619–3,252 pg/mL; p = 0.029]). Similarly, thrombomodulin was significantly elevated on days 2 and 3 in those with worse functional status compared with those without (day 2: median 143 ng/mL [IQR, 92–216 ng/mL] vs 111 ng/mL [IQR, 74–155 ng/mL; p = 0.038] and day 3: median 156 ng/mL [IQR, 128–204 ng/mL] vs 109 ng/mL [IQR, 76–157 ng/mL; p = 0.001]) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Plasma interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) and thrombomodulin levels are significantly higher on days 2 and 3 in patients with a functional decline at hospital discharge. Comparison of plasma biomarker levels in children with and without functional decline at hospital discharge following acute respiratory failure: (A) IL-1ra, (B) thrombomodulin, (C) interleukin-8 (IL-8), (D) plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1). The numbers below each graph represent the number of plasma samples analyzed on each day in those with no decline in functional status and those with worsening of functional status at discharge. *p < 0.05 for comparison of biomarker level in those with and without decline in functional status on the indicated day. IQR = interquartile range.

In multivariable analysis, IL-1ra was associated with a decline in functional status on days 2 and 3 after adjustment for age and highest OI (day 2: odds ratio [OR], 1.43; 1.03–1.97; p = 0.03 and day 3: OR, 1.55; 1.06–2.26; p = 0.02). However, IL-1ra was not associated with a worsening in POPC after adjusting for age and cardiovascular failure on days 1, 2, or 3 (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Multivariable Analysis of the Association of Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist With Decline in Functional Outcome

| Models | Worsening of Pediatric Overall Performance Category | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Model 1 | ||

| Day 1 | ||

| IL-1ra | 1.02 (0.68–1.53) | 0.92 |

| Age | 1.07 (0.98–1.16) | 0.13 |

| Highest OI | 1.02 (0.98–1.05) | 0.40 |

| Day 2 | ||

| IL-1ra | 1.43 (1.03–1.97) | 0.03 |

| Age | 1.09 (1.03–1.17) | < 0.01 |

| Highest OI | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | 0.24 |

| Day 3 | ||

| IL-1ra | 1.55 (1.06–2.26) | 0.02 |

| Age | 1.09 (1.02–1.17) | 0.01 |

| Highest OI | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.01 |

| Model 2 | ||

| Day 1 | ||

| IL-1ra | 0.94 (0.63–1.41) | 0.78 |

| Age | 1.03 (0.95–1.13) | 0.46 |

| CV failure | 5.76 (1.17–28.3) | 0.03 |

| Day 2 | ||

| IL-1ra | 1.31 (0.94–1.83) | 0.12 |

| Age | 1.07 (1.00–1.14) | 0.045 |

| CV failure | 6.66 (1.47–30.16) | 0.01 |

| Day 3 | ||

| IL-1ra | 1.45 (0.98–2.13) | 0.06 |

| Age | 1.07 (0.99–1.15) | 0.055 |

| CV failure | 10.87 (1.40–84.67) | 0.02 |

CV = cardiovascular, IL-1ra = interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, OI = oxygenation index, OR = odds ratio.

Similarly, as shown in Table 3, thrombomodulin was associated with a decline in functional status on days 2 and 3 after adjustment for age and highest OI (day 2: OR, 2.19; 1.11–4.30; p = 0.02 and day 3: OR, 3.03; 1.53–6.01; p < 0.01). Thrombomodulin was also associated with worsening of POPC after adjustment for age and cardiovascular failure on day 3 (OR, 2.57; 1.24–5.35; p = 0.01), but there was no association on day 1 or 2 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Multivariable Analysis of the Association of Thrombomodulin With Decline in Functional Outcome

| Models | Worsening of Pediatric Overall Performance Category | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Model 1 | ||

| Day 1 | ||

| Thrombomodulin | 1.58 (0.66–3.80) | 0.31 |

| Age | 1.09 (0.99–1.18) | 0.06 |

| Highest OI | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) | 0.47 |

| Day 2 | ||

| Thrombomodulin | 2.19 (1.11–4.30) | 0.02 |

| Age | 1.10 (1.03–1.17) | < 0.01 |

| Highest OI | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 0.15 |

| Day 3 | ||

| Thrombomodulin | 3.03 (1.53–6.01) | < 0.01 |

| Age | 1.09 (1.02–1.17) | 0.01 |

| Highest OI | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) | < 0.01 |

| Model 2 | ||

| Day 1 | ||

| Thrombomodulin | 1.52 (0.61–3.79) | 0.37 |

| Age | 1.06 (0.96–1.15) | 0.24 |

| CV failure | 4.36 (0.89–21.35) | 0.07 |

| Day 2 | ||

| Thrombomodulin | 1.97 (0.99–3.92) | 0.052 |

| Age | 1.07 (1.00–1.15) | 0.04 |

| CV failure | 7.56 (1.71–33.52) | < 0.01 |

| Day 3 | ||

| Thrombomodulin | 2.57 (1.24–5.35) | 0.01 |

| Age | 1.07 (0.99–1.15) | 0.054 |

| CV failure | 11.70 (1.51–90.76) | 0.02 |

CV = cardiovascular, OI = oxygenation index, OR = odds ratio.

Additional Multivariable Models

In models adjusting for PRISM-III (to account for overall illness severity) and age, there was no association of IL-1ra or thrombomodulin with decline in functional status on any day (eTable 1, Online Supplement, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A693). To evaluate the influence of a systemic inflammatory process, we included sepsis diagnosis in our model. After adjusting for age and primary diagnosis of sepsis, both IL-1ra and thrombomodulin were associated with a decline in functional status on days 2 and 3 (eTable 2, Online Supplement, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A693). Finally, when highest OI and cardiovascular failure were both included in the model, there was no association between worsening of functional status and IL-1ra on days 1–3. However, thrombomodulin levels measured on days 2 and 3 were associated with worsening of POPC independent of age, highest OI, and cardiovascular failure (eTable 3, Online Supplement, http://links.lww.com/CCX/A693).

DISCUSSION

In this secondary analysis of the BALI study of children with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, elevated levels of IL-1ra and thrombomodulin on days 2 or 3 following intubation were associated with a decline in overall functional status at discharge. There was no association between day 1 biomarker levels and worse functional status at discharge, nor any association between IL-8 or PAI-1 and functional decline.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the association between plasma biomarkers and functional status in children with acute respiratory failure. Prior work has examined the association between plasma biomarkers (5, 17) and clinically relevant outcomes such as duration of MV, mortality, and length of PICU stay in PARDS patients. Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1ra and IL-8, released in response to cell injury, recruit macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils, and activate T-cells and epithelial cells in order to sustain ongoing inflammation (5, 17). In the complete BALI cohort, both IL-1ra and IL-8 were associated with mortality, length of PICU stay, and oxygenation defect (6, 8). PAI-1, an inhibitor of tissue plasminogen activator and subsequent fibrinolysis, has been associated with mortality among children with acute lung injury (18). Higher levels of thrombomodulin, a transmembrane endothelium protein integral to thrombosis hemostasis but also with relevant anti-inflammatory properties in patients with sepsis, are also associated with mortality (19, 20).

While prior studies have demonstrated a relationship between biomarkers (including those measured in our study) and outcomes including organ failure and mortality, this investigation did not uncover an association between IL-8 or PAI-1 and decline in functional status. However, both IL-1ra and thrombomodulin were significantly higher among children with a worsening of POPC at discharge. While the cause of the disparity between results of these four markers remains unclear, the results do suggest the effects of inflammatory biomarkers are nuanced. IL-1ra is elaborated very early in the inflammatory cascade and, in fact, is associated with anti-inflammatory effects (21). Similarly, thrombomodulin has anti-inflammatory properties in that it assists in limiting leukocyte adhesion (22, 23). It could be postulated that continued elevations in these markers for several days after onset of acute respiratory failure reflect the body’s attempt at reversing an ongoing pro-inflammatory processes. As well, it is biologically plausible that patients with prolonged inflammation would be subject to overall worse functional status. It is possible these biomarkers could be used in prognostic or predictive enrichment strategies; however, this requires further investigation in a larger cohort.

In multivariable models, neither thrombomodulin nor IL-1ra was associated with worse functional status after adjustment for severity of illness (in our study PRISM-III). Higher severity of illness measures has been repeatedly associated with subsequent functional decline both at ICU discharge and beyond (13, 24, 25). As PRISM-III accounts for severity of multiple organ system dysfunctions, it is not surprising that this would render the biomarker results statistically insignificant, as it can also be presumed that patients with multiple organ system dysfunction likely, but not always, are hyper-inflamed (26). In two models adjusting for individual organ dysfunctions, represented by OI and cardiovascular dysfunction, thrombomodulin levels on days 2 and 3 were independently associated with functional decline at hospital discharge. IL-1ra, however, was only independently associated with functional decline in the model that included OI. Our results are similar to prior studies that demonstrate a strong association between respiratory failure, cardiovascular dysfunction, and decreased quality of life and new morbidity (4, 13, 14).

Nearly one in 10 patients included in our analysis experienced a decline in POPC from admission to discharge, lower than what has been observed in prior studies (13, 27). New morbidity or abnormal functional status is common among children with PARDS (13) and acute respiratory failure (27), occurring in 25–50% of patients. Similar findings are observed among adult patients, solidifying the association between acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or acute respiratory failure and subsequent functional decline (28, 29). Among the larger RESTORE cohort, a higher percent of patients declined from hospital discharge to 6 months post-discharge compared with baseline to hospital discharge (2). Thus, the lower percentage of patients with functional decline in our cohort compared with others may be in part due to our cutoff at hospital discharge. Finally, this smaller number of patients (n = 40) may have limited our ability to detect an association between biomarkers and decline in functional status, especially when adjusting for covariates very strongly associated with illness severity and outcome, like PRISM-III score.

The association of elevated levels of IL-1ra and thrombomodulin on days 2 and 3 with a decline in function (or worsening of POPC) at discharge suggests these patients may have experienced a prolonged inflammatory process in these patients. These persistent levels provide an opportunity to measure the association between ongoing inflammation and disease progression or other outcome measures (8). Thrombomodulin, an endothelial and pulmonary capillary transmembrane protein, is active in coagulation and inflammatory processes. Normal circulating levels are low; however, in the presence of inflammation such as sepsis and ARDS, plasma levels increase (19, 30). IL-1ra competitively binds to the IL-1 receptor, limiting the binding of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β, which increases in response to infection or inflammation. Thus, while IL-1ra itself is “anti-inflammatory,” high levels suggest a more robust inflammatory response to an insult (6). In our study, and the larger BALI cohort, biomarker levels were highly variable (6, 8). Consequently, they may be used to subphenotype the overall patient cohort or potentially be useful as a marker of therapeutic effectiveness.

Our study has several limitations. We were not able to effectively evaluate the relationship between biomarker status and neurocognitive decline as measured by PCPC. Although the PCPC was measured in this cohort, a smaller portion of patients had a decline in PCPC at discharge and available biomarker measurements (data not shown), rendering us unable to accurately evaluate this relationship. Thus, we recommend greater and more precise studies of functional decline including PCPC, POPC, and Functional Status Scale in future studies. Additionally, change in functional status was measured at hospital discharge. Therefore, we may have underestimated the total number of patients with functional decline as prior studies show a larger decline from discharge to 6 months post-hospitalization (2). Also, we a priori excluded patients with severe functional disability (POPC > 3), who may have had a decline in functional status. However, this accounted for only 12% of the patients. We were also limited by the number of patients with available biomarker data. While 22% of patients did not have samples available, baseline characteristics were similar to those with biomarkers sampled. We do suggest future studies explore the predictive ability of these biomarkers, including trends over time, on functional outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, elevated levels of IL-1ra and thrombomodulin are associated with a decline in functional status among children with acute respiratory failure. This may suggest an association between persistent inflammation and a patient’s overall functional status. Additional investigation with more refined functional outcome measures, such as the Functional Status Score, is warranted to understand the association between biomarker levels and long-term functional outcomes, particularly if in association with randomized clinical trials with long-term outcome measures.

Supplementary Material

APPENDIX 1

BALI study investigators are as follows:

Heidi Flori (Principal Investigator, BALI; University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor, MI); Michael W. Quasney (Principal Investigator, BALI; University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor, MI); Mary K. Dahmer (Principal Investigator, BALI; University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor, MI); Anil Sapru (coinvestigator, BALI; Mattel Children’s Hospital at UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA); Martha Curley (coinvestigator, BALI; principal investigator, RESTORE; School of Nursing and the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA; Critical Care and Cardiovascular Program, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA); Michael A. Matthay (coinvestigator, BALI; University of California at San Francisco School of Medicine, San Francisco, CA); Scot T. Bateman (University of Massachusetts Memorial Children’s Medical Center, Worcester, MA); M. D. Berg (University of Arizona Medical Center, Tucson, AZ); Santiago Borasino (Children’s Hospital of Alabama, Birmingham, AL); G. Kris Bysani (Medical City Children’s Hospital, Dallas, TX); Allison S. Cowl (Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, CT); Cindy Darnell Bowens (Children’s Medical Center of Dallas, Dallas, TX); E. Vincent S. Faustino (Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital, New Haven, CT); Lori D. Fineman (University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospital at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA); A. J. Godshall (Florida Hospital for Children, Orlando, FL); Ellie Hirshberg (Primary Children’s Medical Center, Salt Lake City, UT); Aileen L. Kirby (Oregon Health & Science University Doernbecher Children's Hospital, Portland, OR); Gwenn E. McLaughlin (Holtz Children’s Hospital, Jackson Health System, Miami, FL); Shivanand Medar (Cohen Children's Medical Center of New York, Hyde Park, NY); Phineas P. Oren (St. Louis Children’s Hospital, St. Louis, MO); James B. Schneider (Cohen Children's Medical Center of New York, Hyde Park, NY); Adam J. Schwarz (Children’s Hospital of Orange County, Orange, CA); Thomas P. Shanley (C. S. Mott Children’s Hospital at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI); Lauren R. Sorce (Ann & Robert H. Lurie, Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL); Edward J. Truemper (Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, Omaha, NE); Michele A. Vander Heyden (Children's Hospital at Dartmouth, Dartmouth, NH); Kim Wittmayer (Advocate Hope Children’s Hospital, IL); Athena Zuppa (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA); and the RESTORE data coordination center led by David Wypij, PhD (Department of Biostatistics, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA; Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Department of Cardiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA).

The RESTORE study investigators include the following:

Martha A. Q. Curley (Principal Investigator; School of Nursing and the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA; Critical Care and Cardiovascular Program, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA); David Wypij (Principal Investigator—Data Coordinating Center; Department of Biostatistics, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School; Department of Cardiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA); Geoffrey L. Allen (Children’s Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, MO); Derek C. Angus (Clinical Research, Investigation and Systems Modeling of Acute Illness Center, Pittsburgh, PA); Lisa A. Asaro (Department of Cardiology, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA); Judy A. Ascenzi (The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD); Scot T. Bateman (University of Massachusetts Memorial Children’s Medical Center, Worcester, MA); Santiago Borasino (Children’s Hospital of Alabama, Birmingham, AL); Cindy Darnell Bowens (Children’s Medical Center of Dallas, Dallas, TX); G. Kris Bysani (Medical City Children’s Hospital, Dallas, TX); Ira M. Cheifetz (Duke Children’s Hospital, Durham, NC); Allison S. Cowl (Connecticut Children's Medical Center, Hartford, CT); Brenda L. Dodson (Department of Pharmacy, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA); E. Vincent S. Faustino (Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital, New Haven, CT); Lori D. Fineman (University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospital at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA); Heidi R. Flori (University of California at San Francisco Benioff Children's Hospital at Oakland, Oakland, CA); Linda S. Franck (University of California at San Francisco School of Nursing, San Francisco, CA); Rainer G. Gedeit (Department of Pediatrics, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI); Mary Jo C. Grant (Primary Children’s Hospital, Salt Lake City, UT); Andrea L. Harabin (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD); Catherine Haskins-Kiefer (Florida Hospital for Children, Orlando, FL); James H. Hertzog (Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, DE); Larissa Hutchins (The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA); Aileen L. Kirby (Oregon Health & Science University Doernbecher Children's Hospital, Portland, OR); Ruth M. Lebet (School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA); Michael A. Matthay (University of California at San Francisco School of Medicine, San Francisco, CA); Gwenn E. McLaughlin (Holtz Children’s Hospital, Jackson Health System, Miami, FL); JoAnne E. Natale (University of California Davis Children’s Hospital, Sacramento, CA); Phineas P. Oren (St. Louis Children’s Hospital, St. Louis, MO); Nagendra Polavarapu (Advocate Children’s Hospital-Oak Lawn, Oak Lawn, IL); James B. Schneider (Cohen Children's Medical Center of New York, Hyde Park, NY); Adam J. Schwarz (Children’s Hospital of Orange County, Orange, CA); Thomas P. Shanley (C. S. Mott Children’s Hospital at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI); Shari Simone (University of Maryland Medical Center, Baltimore, MD); Lewis P. Singer (The Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, NY); Lauren R. Sorce (Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL); Edward J. Truemper (Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, Omaha, NE); Michele A. Vander Heyden (Children's Hospital at Dartmouth, Dartmouth, NH); R. Scott Watson (Center for Child Health, Behavior and Development, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, WA); Claire R. Wells (University of Arizona Medical Center, Tucson, AZ).

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccejournal).

Drs. Dahmer, Quasney, Sapru, and Flori were supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01HL095410) for the Biomarkers in Children with Acute Lung Injury study. The parent study (Randomized Evaluation of Sedation Titration for Respiratory Failure) was supported, in part, by a grant from the NIH awarded to Dr. Curley (U01HL086622). The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Heidi Flori, Michael W. Quasney, Mary K. Dahmer, Anil Sapru, Martha Curley, Michael A. Matthay, Scot T. Bateman, M. D. Berg, Santiago Borasino, G. Kris Bysani, Allison S. Cowl, Cindy Darnell Bowens, E. Vincent S. Faustino, Lori D. Fineman, A. J. Godshall, Ellie Hirshberg, Aileen L. Kirby, Gwenn E. McLaughlin, Shivanand Medar, Phineas P. Oren, James B. Schneider, Adam J. Schwarz, Thomas P. Shanley, Lauren R. Source, Edward J. Truemper, Michele A. Vander Heyden, Kim Wittmayer, Athena Zuppa, David Wypij, Martha A. Q. Curley, David Wypij, Geoffrey L. Allen, Derek C. Angus, Lisa A. Asaro, Judy A. Ascenzi, Scot T. Bateman, Santiago Borasino, Cindy Darnell Bowens, G. Kris Bysani, Ira M. Cheifetz, Allison S. Cowl, Brenda L. Dodson, E. Vincent S. Faustino, Lori D. Fineman, Heidi R. Flori, Linda S. Franck, Rainer G. Gedeit, Mary Jo C. Grant, Andrea L. Harabin, Catherine Haskins-Kiefer, James H. Hertzog, Larissa Hutchins, Aileen L. Kirby, Ruth M. Lebet, Michael A. Matthay, Gwenn E. McLaughlin, JoAnne E. Natale, Phineas P. Oren, Nagendra Polavarapu, James B. Schneider, Adam J. Schwarz, Thomas P. Shanley, Shari Simone, Lewis P. Singer, Lauren R. Source, Edward J. Truemper, Michele A. Vander Heyden, R. Scott Watson, and Claire R. Wells

REFERENCES

- 1.Khemani RG, Smith L, Lopez-Fernandez YM, et al. ; Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress syndrome Incidence and Epidemiology (PARDIE) Investigators; Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network. Paediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome incidence and epidemiology (PARDIE): An international, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7:115–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson RS, Asaro LA, Hertzog JH, et al. ; RESTORE Study Investigators and the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network. Long-term outcomes after protocolized sedation versus usual care in ventilated pediatric patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 197:1457–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward SL, Gildengorin V, Valentine SL, et al. Impact of weight extremes on clinical outcomes in pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 2016; 44:2052–2059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson RS, Asaro LA, Hutchins L, et al. Risk factors for functional decline and impaired quality of life after pediatric respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 200:900–909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlton EF, Flori HR. Biomarkers in pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Transl Med 2019; 7:505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahmer MK, Quasney MW, Sapru A, et al. ; BALI and RESTORE Study Investigators and Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist is associated with pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome and worse outcomes in children with acute respiratory failure. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2018; 19:930–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahmer MK, Flori H, Sapru A, et al. ; BALI and RESTORE Study Investigators and Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network. Surfactant protein D is associated with severe pediatric ARDS, prolonged ventilation, and death in children with acute respiratory failure. Chest 2020; 158:1027–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flori H, Sapru A, Quasney MW, et al. ; BALI and RESTORE Study Investigators, Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network. A prospective investigation of interleukin-8 levels in pediatric acute respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care 2019; 23:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yehya N, Thomas NJ, Meyer NJ, et al. Circulating markers of endothelial and alveolar epithelial dysfunction are associated with mortality in pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med 2016; 42:1137–1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curley MAQ, Wypij D, Watson RS, et al. Protocolized sedation vs usual care in pediatric patients mechanically ventilated for acute respiratory failure. JAMA 2015; 313:379–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiser DH. Assessing the outcome of pediatric intensive care. J Pediatr 1992; 121:68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sankar J, Moodu S, Kumar K, et al. Functional outcomes at 1 year after PICU discharge in critically ill children with severe sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2021; 22:40–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keim G, Watson RS, Thomas NJ, et al. New morbidity and discharge disposition of pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors. Crit Care Med 2018; 46:1731–1738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmerman JJ, Banks R, Berg RA, et al. ; Life After Pediatric Sepsis Evaluation (LAPSE) Investigators. Critical illness factors associated with long-term mortality and health-related quality of life morbidity following community-acquired pediatric septic shock. Crit Care Med 2020; 48:319–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khemani RG, Thomas NJ, Venkatachalam V, et al. ; Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Network Investigators (PALISI). Comparison of SpO2 to PaO2 based markers of lung disease severity for children with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 2012; 40:1309–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muniraman HK, Song AY, Ramanathan R, et al. Evaluation of oxygen saturation index compared with oxygenation index in neonates with hypoxemic respiratory failure. JAMA Netw Open 2019; 2:e191179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orwoll BE, Sapru A. Biomarkers in pediatric ARDS: Future directions. Front Pediatr 2016; 4:765–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sapru A, Curley MA, Brady S, et al. Elevated PAI-1 is associated with poor clinical outcomes in pediatric patients with acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med 2010; 36:157–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orwoll BE, Spicer AC, Zinter MS, et al. Elevated soluble thrombomodulin is associated with organ failure and mortality in children with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): A prospective observational cohort study. Crit Care 2015; 19:435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sapru A, Calfee CS, Liu KD, et al. ; NHLBI ARDS Network. Plasma soluble thrombomodulin levels are associated with mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med 2015; 41:470–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dinarello CA. Overview of the IL-1 family in innate inflammation and acquired immunity. Immunol Rev 2018; 281:8–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishizawa S, Kikuta J, Seno S, et al. Thrombomodulin induces anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting the rolling adhesion of leukocytes in vivo. J Pharmacol Sci 2020; 143:17–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okamoto T, Tanigami H, Suzuki K, et al. Thrombomodulin: A bifunctional modulator of inflammation and coagulation in sepsis. Crit Care Res Pract 2012; 2012:614545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ong C, Lee JH, Leow MKS, et al. Functional outcomes and physical impairments in pediatric critical care survivors. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2016; 17:e247–e259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keim G, Yehya N, Spear D, et al. ; Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network. Development of persistent respiratory morbidity in previously healthy children after acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med 2020; 48:1120–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calfee CS, Delucchi KL, Sinha P, et al. ; Irish Critical Care Trials Group. Acute respiratory distress syndrome subphenotypes and differential response to simvastatin: Secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6:691–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yagiela LM, Barbaro RP, Quasney MW, et al. Outcomes and patterns of healthcare utilization after hospitalization for pediatric critical illness due to respiratory failure*. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2019; 20:120–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herridge MS, Moss M, Hough CL, et al. Recovery and outcomes after the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients and their family caregivers. Intensive Care Med 2016; 42:725–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, et al. ; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:1293–1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faust SN, Levin M, Harrison OB, et al. Dysfunction of endothelial protein C activation in severe meningococcal sepsis. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:408–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.