Abstract

Temperamental behavioral inhibition (BI) is a robust endophenotype for anxiety characterized by increased sensitivity to novelty. Controlling parenting can reinforce children’s wariness by rewarding signs of distress. Fine-grained, dynamic measures are needed to better understand both how children perceive their parent’s behaviors and the mechanisms supporting evident relations between parenting and socioemotional functioning. The current study examined dyadic attractor patterns (average mean durations) with state space grids, using children’s attention patterns (captured via mobile eye-tracking) and parental behavior (positive reinforcement, teaching, directives, intrusion), as functions of child BI and parent anxiety. 40 5- to 7-year-old children and their primary caregivers completed a set of challenging puzzles, during which the child wore a head-mounted eye-tracker. Child BI was positively correlated with proportion of parent’s time spent teaching. Child age was negatively related, and parent anxiety level was positively related, to parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength. There was a significant interaction between parent anxiety level and child age predicting parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength. This study is a first step to examining the co-occurrence of parenting behavior and child attention in the context of child BI and parental anxiety levels.

Keywords: Behavioral inhibition, mobile eye-tracking, parenting, anxiety, state space grids

Introduction

The temperamental trait of behavioral inhibition (BI) is one of the most robust endophenotypes for anxiety (Fox, Hane, & Pine, 2007), with an up to seven-fold risk for children with BI to go on to develop an anxiety disorder in adolescence (Clauss & Blackford, 2012). BI is characterized by increased sensitivity to novelty or the unfamiliar and the later emergence of social withdrawal and anxious behaviors (e.g., Garcia Coll, Kagan, & Reznick, 1984). Children with higher levels of BI often use freezing or avoidance strategies in response to novel situations, which decreases their experienced fear in the moment. Over time, however, momentarily escaping fear-eliciting situations can reinforce these anxious behaviors. When children use avoidance behaviors over time, they canalize their inhibited tendencies, which in turn can lead to social wariness and anxiety (Fox, Henderson, Marshall, Nichols, & Ghera, 2005).

Overly responsive and intrusive parenting can also reinforce wariness in novel situations by rewarding children’s initial signs of distress as the parent takes control of the situation for the child (Burgess, Rubin, Cheah, & Nelson, 2001; Fox et al., 2005). Parents with an anxiety disorder are often more likely to engage in these behaviors (Budinger, Drazdowski, & Ginsburg, 2013; Teetsel, Ginsburg, & Drake, 2014). How children respond to their parents is less clear. Research on parent-child interactions has often relied on more global ratings of dyadic behaviors (e.g., Rubin, Burgess, & Hastings, 2002). No research to date has directly observed how inhibited children visually attend to their parent’s behavior over the course of an interaction task. Further, research has yet to characterize how parental anxiety levels in a community sample may alter the relations among child BI, parenting, and attention.

To address these questions, fine-grained, dynamic measures are needed to better understand whether children attend to their parent’s controlling behaviors, potentially serving as a mechanism to support the relations between parenting and socioemotional functioning. Mobile eye-tracking methodology can capture child attention patterns within the dynamics of parent-child interactions. The current study examined attractors in parent-child dyads with state space grids, using indicators of children’s attention patterns (captured via mobile eye-tracking) and parenting behaviors. Additionally, we investigated whether this dyadic behavior differed depending on levels of child BI and parent anxiety symptoms.

Relationships between Parents and their Behaviorally Inhibited Children

Early and middle childhood is an important time for engaging in tasks more independently, forming goals for activities, and self-monitoring experiences and mental processes. The dyad transitions from parents’ regulation of their children’s behavior to the child initiating their own course of action. When entering formal schooling, children face new developmental tasks, and gaining autonomy is now necessary for skill mastery (Collins, Madsen, & Susman-Stillman, 2002). Parents are critical resources for teaching children how to navigate problems, while also letting children complete tasks with minimal help (Ladd & Pettit, 2002). Further, at this time in development, children are more adept at inferring the motivations behind other people’s behaviors (Crick & Dodge, 1994) and are therefore more sensitive to parents’ behaviors and intentions. Given the transformations of the parent-child relationship beginning in early childhood, this is a developmental window that is ripe for examining variability in how parents and children navigate this new territory in their relationship.

There is a large body of work on the role of parenting in the development and maintenance of children’s fearful temperament (Hastings, Rubin, Smith, & Wagner, 2019). Parental criticism and control are robust predictors of child anxiety (e.g., Chorpita, Albano, & Barlow, 1996; Rapee, 2001). Thomasgard and Metz (1993) define overcontrol as demonstrations of warmth, intrusiveness, and restrictiveness in situations that do not warrant this type of behavior. Overcontrol encompasses a broad range of behaviors that share a common factor of encouraging children’s dependence on parents (Wood, McLeod, Sigman, Hwang, & Chu, 2003). Mother-reported child fearful temperament has been positively associated with BI observed with peers, only for children whose mothers were over-solicitous (i.e., helped when the child did not ask for help, displayed exaggerated positivity, and did not attend to child cues; Rubin, Hastings, Stewart, Henderson, & Chen, 1997). Parents’ negative control moderates the relation between fearful temperament and internalizing problems in young children (Karreman, de Haas, van Tuijl, van Aken, & Deković, 2010). Consistently high levels of BI in children across early and middle childhood predict higher symptoms of social anxiety in adolescence for children whose mothers are high in over-control at age 7 years (Lewis-Morrarty et al., 2012). Thus, parents may reinforce these negative coping behaviors in their child, sending the message that the child may not be able to handle potentially stressful situations which then maintains or heightens their fearful tendencies. In contrast, parents who show acceptance of children’s negative affect, rather than attempt to criticize or minimize, promote children’s emotion regulation by facilitating learning through trial and error (Gottman, Katz, Hooven, 1997).

In general, these studies suggest that controlling parenting spills over into the social functioning of BI children. In examining parent-child relationships in dyads where the child has higher levels of BI, research has most often examined parent-driven effects (i.e., behaviors the parent initiates in the dyad) and how the prevalence and breadth of these behaviors may vary with child factors (i.e., temperament). Little research on child BI has observed how parenting behaviors co-occur with child behaviors throughout an interaction. More research is needed on parent-child dynamics to elucidate how parenting a temperamentally fearful child comes to predict developmental outcomes for that child (Wood et al., 2003). The investigation of children’s visual attention patterns during a parent-child interaction is a first step to understanding if, and under what circumstances, children attend to these controlling behaviors of their parents to eventually explain the evident relations between parenting in one context and children’s inhibited behavior in the next (e.g., with peers).

Children’s anxiety-related behaviors may emerge through interactions with an anxious parent. Parents with social anxiety disorder demonstrate less warmth and greater negativity in parent-child interactions relative to parents without a social anxiety disorder (Budinger et al., 2013). Relative to anxious parent/non-anxious child dyads, dyads with non-anxious parents and children have demonstrated significantly more productive engagement, fewer negative parenting behaviors, and less child negative interaction (Schrock & Woodruff-Borden, 2010). The impact of parental anxiety on their productive engagement may have deleterious consequences for their role as a model of appropriate behavioral regulation for their children when faced with a novel or difficult task. Parents may also be more likely to engage in controlling behavior when both parent and child are anxious. For instance, anxious mothers are more intrusive during a parent-child interaction when their child expresses more anxious behaviors (Creswell et al., 2013). In sum, anxiety-related behaviors in both parents and children drive the nature of the dyadic interaction that can have important implications for child functioning.

Using a First-Person Approach to Capture Social Referencing

Children may come to internalize parents’ overcontrolling behaviors through social referencing, as the child gains information about an uncertain situation by looking to their parent’s responses. Social referencing studies have traditionally been conducted with infants, indicating that infants show higher levels of social referencing to parents’ positive affect and use that information as cues for engaging with novel toys (Walden & Ogan, 1988). In addition, researchers have linked social referencing to the intergenerational transmission of anxiety (e.g., Aktar, Majdandžić, de Vente, & Bögels, 2014; Murray et al., 2008). A child’s temperament may make them more likely to reference their parent during novel or stressful situations. For instance, mothers’ anxious responding during a stranger interaction in an experimental laboratory task was related to avoidance behaviors in-task for temperamentally high-fear infants compared to low-fear infants (de Rosnay, Cooper, Tsigaras, & Murray, 2006). The current study aimed to describe how parents of children with higher levels of BI, as a function of their own varying levels of anxiety, engaged in controlling behaviors (e.g., directives, intrusion) that may have sent the message that the child could not complete the task on their own. Additionally, we examined how often the child visually referenced the parent during these behaviors. Therefore, this study deviated from traditional social referencing studies, such that children were not necessarily learning scaffolding or controlling behaviors by looking at parents. Rather, they referenced the parent to gain information about the task, and we surmised that how and what information was delivered could have consequences for their socioemotional functioning.

As previously mentioned, the extant literature has established associations between overcontrolling parenting behaviors and children’s BI (e.g., Hastings et al., 2019; Lewis-Morrarty et al., 2012; Rubin et al., 1997). Additionally, research suggests that children of anxious parents may demonstrate less productive engagement and are more controlling in tasks than children of non-anxious parents (e.g., Budinger et al., 2013; Schrok & Woodruff-Borden, 2010; Teetsel et al., 2014). Lastly, temperamentally fearful children may reference their parents more during novel situations than non-fearful children (e.g., de Rosnay et al., 2006). However, no research to date has examined how children’s attention patterns co-occur with parenting behavior over the course of a novel, challenging task, and whether these interactions are associated with level of BI or the parent’s anxiety symptoms.

Until recently, studies investigating social gaze have relied on gaze cueing with static stimuli or manual coding of looking behavior from a third-person perspective (e.g., Kiel & Buss, 2011). While stationary eye-tracking has provided critical insights into how, at the level of milliseconds, individuals orient to social stimuli, it cannot capture real-life social interactions. Along the same line, manual coding of looking behavior from a room camera is manageable for coding gross social referencing during a real-life interaction, but the areas of interest must be large enough and far enough apart to be easily differentiated and support reliable behavior coding. Mobile eye-tracking can capture, from a first-person perspective, fine-grained and continuous data of an individual’s attention orienting (Pérez-Edgar, MacNeill, & Fu, 2020). This could facilitate the identification of mechanisms linking parenting and the development of anxiety.

Researchers are just beginning to use eye-tracking methodology to capture attention patterns in temperamentally fearful children. For example, Fu and colleagues (Fu, Nelson, Borge, Buss, & Pérez-Edgar, 2019) examined threat-related attention in BI children using mobile eye-tracking. They found that BI children had a lower frequency of gaze shifts to a stranger during a temperament paradigm versus non-BI children. This is one of the first studies to assess attention to potential threat during a real-life interaction, demonstrating distinct patterns of attention for BI children in a relatively ecologically valid setting.

Leveraging mobile eye-tracking technology, the current study employed a more ecologically valid assessment of behavior to examine how often children attended to parental behavior during a novel task. Because parenting and looking behaviors occurred simultaneously in the current study, we propose that social referencing could potentially represent two different functions. First, it may be that the child looks to different parenting behaviors as they are occurring, because these behaviors may be important for learning about and completing the task. Second, the child may look to the parent to prompt scaffolding or controlling behaviors for task completion, and the parent then engages in either more positive (e.g., positive reinforcement, teaching) or more controlling behaviors. In this way, we may begin to see individual differences in behavior emerge depending on child temperament and parent anxiety symptom levels. Using information from mobile eye-tracking, particularly within a dynamic systems framework, will provide a novel way of characterizing individual differences in parent-child interactions patterns.

Between-Family Differences in Within-Family Dynamics: State Space Grids

Examining parental socialization as a mutually interactive process supports efforts to effectively study parent-child relationships. Transactional models of development highlight the interactions between parenting and temperament across the spectrum of parental behaviors (Putnam, Sanson, & Rothbart, 2002). Although behavioral composites and their averages shed light on common aggregate behaviors, they cannot explain reciprocal response patterns over the course of an interaction. Dynamic systems research argues that parents should move through states of responding depending on the child and context. Rigidly remaining in a negative state for too long may be harmful to the child (Hollenstein, Granic, Stoolmiller, & Snyder, 2004).

State space grids portray dyadic variation over time by plotting how members of the dyad move within a figurative space (Lewis, Lamey, & Douglas, 1999), elucidating broader socioemotional profiles (Lunkenheimer, Albrecht, & Kemp, 2013). Research has conceptualized dynamic aspects of parent-child interactions using state space grids in several ways, examining how many grid cells each dyad visited, how long dyads remained in each state on average, how many transitions the dyad made during an interaction, and the overall dispersion across the grid (Hollenstein et al., 2004; Lunkenheimer et al., 2013; Lunkenheimer, Hollenstein, Wang, & Shields, 2012).

Dynamic aspects of interactions are also evident in attractor patterns. Attractors are states that pull the dyadic system from other states under particular conditions (Thelen & Smith, 1998). Attractors can be measured by calculating the average mean duration (AMD) for a particular grid sequence (Hollenstein et al., 2004). A higher AMD in a given state typically indicates a greater attractor and more time is spent in this state at every visit, implying that dyads may get “stuck” in a particular behavioral pattern (Lunkenheimer & Dishion, 2009). The adaptiveness of attractors may depend on the context of the attractor. Specifically, in a task meant to elicit emotion socialization, researchers have considered emotion coaching as an adaptive attractor and emotion dismissing as a maladaptive attractor (Lunkenheimer et al., 2012).

The Current Study

Building on this work, the current study plotted areas of interest (AOIs) captured by mobile eye-tracking and video-coded parenting behavior using state space grids. Specifically, we were interested in characterizing dyadic interaction patterns separately for what we considered to be task-focused/positive parenting states (i.e., child looking to the puzzle task while the parent engaged in positive reinforcement and teaching behaviors) and parent-focused/controlling parenting states (i.e., child looking to the parent while the parent engaged in directive and intrusive behaviors). We were interested in characterizing attractors, defined by AMDs in task-focused/positive parenting and parent-focused/controlling parenting states. Our measures and interpretation of attractors are novel and exploratory, thus we cannot assume that these attractors will necessarily lead to adaptive or maladaptive outcomes for children and their parents. The current study had four aims.

The first aim was to assess whether child level of BI was related to child engagement in social referencing (i.e., proportion of time the child looked to the parent and objects to which the parent referenced) during the challenge task. We expected that higher levels of BI would be related to proportionally longer durations of child social referencing.

The second aim was to examine whether child level of BI was associated with parent’s proportional time spent in different parenting behaviors during the task. We expected that higher levels of child BI would be associated with greater parent’s proportional time spent in controlling behaviors (i.e., directives and intrusion) and less time spent in positive behaviors (i.e., positive reinforcement and teaching).

The third aim examined whether level of parent anxiety symptoms was related to proportional time spent in different parenting behaviors during the task. We expected that higher levels of anxiety would be related to more proportional time spent in controlling behaviors and less time spent in positive behaviors.

The fourth aim assessed whether attractors for task-focused/positive parenting and parent-focused/controlling parenting states were associated with child BI and parent anxiety symptoms. We predicted that dyads with children higher in BI would have stronger parent-focused/controlling parenting attractors when parents had higher levels of anxiety. We also predicted that dyads with children lower in BI would have stronger task-focused/positive parenting attractors when parents had lower levels of anxiety. Alternatively, less anxiety in parents may buffer the potentially negative effects of BI, such that higher BI would be related to stronger task-focused/positive parenting attractors when parents were less anxious.

Child age and sex were added to the models if they were significantly related to the outcomes of interest. In those cases, their interactions with BI and parent anxiety levels were also examined. We predicted that dyads with younger children would have stronger parent-focused/controlling parenting attractors, as younger children may expect more help from parents while parents may expect their children to have more difficulty completing the task. These effects would be stronger in higher-BI/higher-anxiety dyads. Children higher in BI may attend to their parent’s behavior more if they are younger and have less experience to draw on when tackling these tasks on their own. Similarly, parents with higher levels of anxiety may be more likely to try to control the situation for the child, in part to alleviate their own anxiety, if they have lower expectations for their child to complete the task due to the child’s age. Regarding child sex, some work suggests that parents respond more warmly to inhibited girls than boys (see Burgess et al., 2001 for review). While sex differences have been found in spatial skills with boys outperforming girls (Levine, Huttenlocher, Taylor, & Langrock, 1999), playing with puzzles is often not gender stereotyped (Serbin & Connor, 1979). Given these mixed findings, these associations were considered exploratory.

Method

Participants

Participants were 40 5- to 7-year-old children (Mage = 6.05; SDage = .62; 19 girls) and their caregivers (5 fathers), drawn from a larger, multi-visit study that oversampled for BI. The sample was predominantly White non-Hispanic (92.5%), which reflects the surrounding rural community. The remaining families self-identified as Asian (n = 1), Hispanic (n =1), and Other (n = 1). Families were recruited using the University’s databases of families interested in participating in research studies, community outreach, and word-of-mouth in the area. Exclusion criteria for participating in this study included being non-English speakers, having gross developmental delays, or having severe neurological or medical illnesses. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Pennsylvania State University. All parents and children completed written consent/assent and received monetary compensation for their participation.

In the larger study, 53 children and their caregivers completed the dyadic interaction task. Of those 53 dyads, 13 dyads were excluded for: technical problems (3), poor calibration (5), unclear task instructions (2), refusing to wear the eye-tracker (2), and a language spoken other than English during the task (1).

Procedure and Measures

Before visiting the lab, the parent completed online questionnaires assessing their child’s temperament, socioemotional functioning, their own characteristics, and their parenting behaviors. During the lab visit, parents and their children completed a modified version of the Parent-Child Challenge Task (PCCT; Lunkenheimer, Kemp, Lucas-Thompson, Cole, & Albrecht, 2017), during which the child wore a head-mounted eye-tracker.

Parent Anxiety.

Parents completed the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck, Epstein, Brown, & Steer, 1988) to measure their anxiety symptoms over the past month. The BAI is comprised of 21 items, ranging on a 4-point scale from 0 (“Not at All”) to 3 (“Severely”). The items were summed to reflect a total anxiety severity score. In the current study, the BAI had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .83).

Behavioral Inhibition.

Parents completed the Behavioral Inhibition Questionnaire (BIQ; Bishop, Spence, & McDonald, 2003) to measure their child’s BI. The BIQ is comprised of 30 items that assess BI-related behavior associated with social and situational novelty and has been correlated with laboratory observations of BI (Dyson, Klein, Olino, Dougherty, & Durbin, 2011). Parents rated items on a scale of 1 (“Hardly Ever”) to 7 (“Almost Always”). In the current study, the BIQ had good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .95) and the total score was analyzed continuously.

Mobile Eye-Tracking Recording during the PCCT.

Eye gaze during the PCCT was captured using a head-mounted eye-tracker (PUPIL; Kassner, Patera, & Bulling, 2014). The eye-tracker had two infrared eye cameras that recorded binocular pupil and corneal reflections from the images of both eyes at a resolution of 640x480 pixels, a framerate of 60 frames per second, and a sampling rate of 60 Hz. The eye-tracker also had a world camera that captured a first-person, 90° diagonal field of view of the individual’s environment at a resolution of 1280x720 pixels, a framerate of 60 frames per second, and a 30 Hz sampling rate. The eye-tracking system’s average gaze estimate accuracy was 0.6° of visual angle (0.08° precision; Kassner et al., 2014). This system allowed for eye fixation information to be integrated with visual information from the perspective of the participant. The head-mounted eye-tracker was connected to an MSI VR One Backpack PC computer worn by the child. The data were recorded with Pupil Capture v.0.9.12 (Pupil Labs) on this computer. The computer backpack and mobile eye-tracker were light enough so that the child could move freely throughout the visit. In order to monitor data collection in real-time, a computer monitor, located in the control room, was wirelessly connected to the computer backpack.

Prior to beginning any of the mobile eye-tracking tasks, the eye-tracker was placed on the child’s head, and eye cameras were adjusted to ensure that each of the child’s pupils was captured by one of the two eye cameras. The experimenter then performed a five-point calibration followed by a validation procedure (see Supplementary Materials for details). This procedure facilitated offline processing of each task, such that the fixation could be corrected, provided that the child had good initial calibration.

In the PCCT (adapted from Lunkenheimer, Kemp, Lucas-Thompson, Cole, & Albrecht, 2017), dyads were asked to complete three tangram puzzles in six minutes. The dyad was seated at a table at the child’s height and given a small magnetic white board with seven tangram puzzle pieces and pictures of the completed puzzles. The white board and puzzle pictures were angled so that the world camera on the eye-tracker could capture the child’s looking behavior toward the task. Parents were instructed to help their children complete the puzzles as they normally would, but only with their words. They could not offer physical help. The tangram puzzles were challenging so that the children could not complete them without guidance. The dyads were asked to work on the puzzles in the order presented and instructed not to move onto the next puzzle until they completed the one prior.

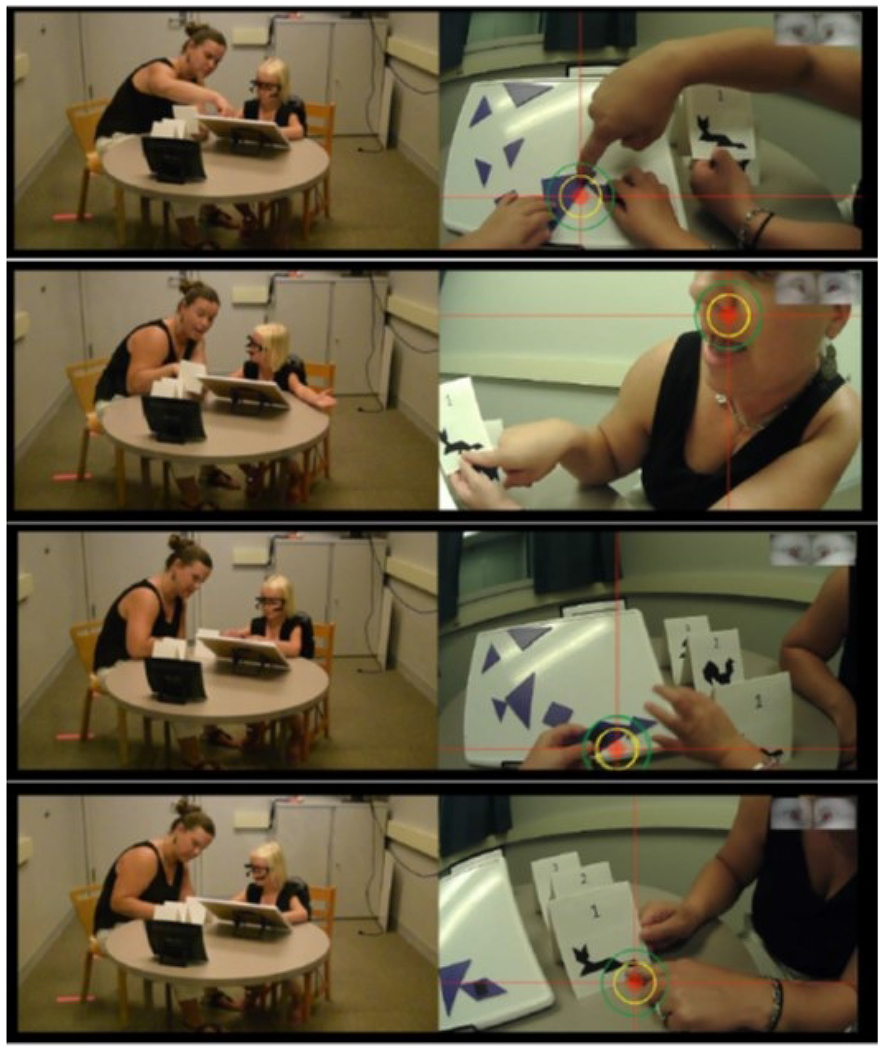

The child was told that if they completed three puzzles in 6 minutes they would receive a prize. In the end, every child received a prize. Four minutes into the task, the experimenter knocked on the door and told the dyad that they had only two minutes left to complete the puzzles. Because the task involved deception about the conditions regarding the prize, parents were debriefed at the end of the task. In addition to the eye-tracker recordings, the PCCT was video-recorded with a room camera to capture the full scope of the room for parenting behavior coding. Figure 1 illustrates the PCCT, displaying the room and eye-tracker recordings side-by-side. An example of the task is also presented here [https://osf.io/f5up9/].

Figure 1.

Example of a parent-child dyad during the PCCT. Room camera is on the left and eye tracking world camera is on the right.

Mobile Eye-Tracking Processing and Coding.

Data from the world and eye cameras were recorded to separate files. To facilitate gaze coding, we processed eye-tracking recordings in Pupil Player v.0.9.12 (Pupil Labs). Details of the processing are provided in the Supplementary Materials (also see Figure 1).

Trained coders coded child eye gaze using an open source video coding program, Datavyu 1.3.4, drawing on previously published methods (Franchak, Kretch, & Adolph, 2018; Fu et al., 2019). Eye gaze data were coded continuously frame-by-frame at a frame rate of 30 frames per second. Coders used the red circle to determine looking behavior. Coders used the yellow circle as a margin of error, rather than the red circle, if: 1) optimal accuracy was not achieved with the manual gaze correction procedures but coders were able to reliably align the gaze location with the yellow circle, or 2) the red circle dropped out of view from the world view, but the coder could use the yellow circle to reliably report where the child was looking. A valid fixation was identified when eye gaze had rested on a location for at least 3 consecutive frames (99.9 milliseconds) or more. Coders documented the onset and offset times for indeterminate frames (i.e., gazes less than 3 consecutive frames, blinks, fixation cross missing). The parameters of each fixation consisted of the AOI and the absolute onset and offset times of the fixation. Coders assessed four minutes (both two minutes before and after the interruption) of the task to minimize coder burden and document behavior surrounding the interruption. This length of time provided approximately 7,200 possible datapoints for each participant. Because fixations could be as short as 100 milliseconds in duration, we expected that four minutes of gaze data would be sufficient to capture variability in looking behavior.

The following AOIs were coded: parent face, parent body, puzzle task (i.e., pictures, puzzle pieces, puzzle board), parent reference (i.e., wherever the parent was pointing/referencing during the task, such that their hand/finger was within the outer margin of error), other (i.e., anything not covered by the other AOIs), and indeterminate. A master coder coded 20% of each video and coders achieved an average kappa of .95. Proportion of looking time on each AOI was calculated by dividing the amount of time the child spent fixated on each AOI by the duration of usable time for that dyad (Total task time – time in indeterminate frames = usable time). On average, 68% of the task had usable eye-tracking data.

Parenting Behavior Coding.

Parenting behaviors were event-coded using an adapted version of the Dyadic Interaction Coding system (Lunkenheimer, 2009) in Datavyu 1.3.4. All codes were mutually exclusive, and the parameters contained parental behaviors, as well as the onset and offset times. The same four minutes of the task used for mobile eye-tracking coding was used. The following codes were used: positive reinforcement, teaching, directives, and intrusion. These behavior codes were selected based on the high likelihood of occurring during a challenging task (Lunkenheimer, Kemp, Lucas-Thompson, Cole, & Albrecht, 2017), as well as behaviors that were likely to occur in the context of BI/Anxiety (Rubin, Cheah, & Fox, 2001).

The Positive Reinforcement code captured instances when the parent praised the child verbally (e.g., “Good job!”). The Teaching code captured instances of verbal teaching and nonverbal teaching. Verbal teaching was when the parent explained a component of the task to the child (e.g., “To make the head, it looks like we’ll need a triangle”) or asked an open-ended question that allowed for a learning opportunity (e.g., “Where do you think this piece goes?”). Nonverbal teaching indicated when the parent referenced part of the task with a gesture, such as tracing shapes with their fingers. If other coded behaviors during nonverbal teaching occurred, those behaviors were coded instead of nonverbal teaching. The Directive code measured the parent instructing the child to do an action during the task, often phrased as a command (e.g., “Move that piece there”). Intrusion was coded when the parent physically took control over the task (e.g., moved the puzzle pieces for the child) or physically moved the child (e.g., restrained the child from playing in a certain way). All 40 parents (100% of the sample) were double-coded. Inter-rater reliability was established at an average kappa of .76 for positive reinforcement, .75 for teaching, .82 for directives, and .94 for intrusion. Proportion of time spent in each behavior was calculated by dividing the amount of time the parent spent in each behavior by the duration of the task for that dyad.

Statistical Analyses

Preliminary Analyses.

Because the proportion of time spent in “parent face” and “parent body” were relatively low (Mparent face = 1%; Mparent body = < 1%), we created a composite variable of “parent” that subsumed any time the child looked at the parent or to where the parent was referencing for all proportion analyses (Aims 1 through 3). Analyses using state space grid attractor measures (Aim 4) treated parent face, body, and reference as separate AOIs. For Aims 1 through 3, we tested zero-order correlations between continuous variables: the relation between child level of BI and child’s proportion of looking time to the parent (Aim 1), the relations between child level of BI and parent’s proportion of time spent in each parenting behavior (Aim 2), and the relations between parent anxiety symptoms and proportion of time spent in each parenting behavior (Aim 3).

To explore the co-occurrence of children’s ambulatory gaze patterns and parents’ behaviors (Aim 4), we constructed state space grids in Gridware 1.15 (Hollenstein et al., 2004; Lamey, Hollenstein, Lewis, & Granic, 2004; Lewis et al., 1999). With the grids, we aimed to document attractor strength (AMD) in task-focused/positive parenting and parent-focused/controlling parenting states. For all measures, task-focused/positive parenting states were comprised of two cells: 1) child looking to puzzle and parent engaging in positive reinforcement, 2) child looking to puzzle and parent engaging in teaching. Parent-focused/controlling parenting states were comprised of six cells: 1) child looking to parent face and parent engaging in directives, 2) child looking to parent face and parent engaging in intrusion, 3) child looking to parent body and parent engaging in directives, 4) child looking to parent body and parent engaging in intrusion, 5) child looking to parent reference and parent engaging in directives, 6) child looking to parent reference and parent engaging in intrusion. AMD refers to the total duration in a specific cell divided by the number of times the dyad occupied that cell, averaged across task-focused/positive parenting cells and parent-focused/controlling parenting cells separately. A higher AMD indicates more time spent at each visit. The child’s AOI fixations were assigned to the x-axis and the parent’s behaviors to the y-axis. The five AOI fixations (parent face, parent body, parent reference, puzzle task, other) and four parenting behaviors (positive reinforcement, teaching, directives, intrusion) resulted in a 5x4 grid with 20 total cells. Grids were pooled across participants to reflect sample means.

Two multiple regression models were used to predict 1) attractor strength in task-focused/positive parenting states, and 2) attractor strength in parent-focused/controlling parenting states. The parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength variable was heavily positively skewed (4.42). Therefore, for this outcome variable, we used a generalized linear model with a Gamma distribution and a log link to handle the positive-skewed, continuous, and non-negative nature of the data (Breen, 1996).

Preliminary analyses also indicated that child age and sex did not significantly predict task-focused/positive parenting attractor strength in regression analyses. Age, however, significantly predicted parent-focused/controlling parenting (b = −0.42, t = −2.61, p = .01) and was thus retained in the model. We also included age by BI and age by anxiety interactions.

Due to the dyadic nature of the state space grids, looking behavior and parenting behavior that did not co-occur were dropped from these analyses. On average, the proportion of the video that had looking and parenting behavior co-occurring was 40%. There are two key reasons for the low proportion of coded data. First, although eye-tracking was coded continuously, there were periods of time that were marked “indeterminate” and were therefore considered missing data. Even with good calibration, the fixation cross would be missing due to incidences such as gross head movements or looking toward the extremes of one’s field of view. The second reason for the low proportion of coded data in the state space grid analyses is the fact that parenting was not coded continuously. We event-coded parenting behavior to capture parenting behaviors of interest and relevance to the current aims. As such, there were periods of time when either no parenting behavior occurred, or a behavior occurred that was not of interest (e.g., emotional support). The amount of available coded data for the dyad may affect the length of time in each state or the number of visits to each state (e.g., dyads with smaller proportions of coded time may have had fewer opportunities to occupy different states). There is the additional possibility that children who moved their head more often were less focused on the task, which may be related to the amount of time they spent attending to the different AOIs. Therefore, all regression analyses controlled for the proportion of time that was coded for each participant (i.e., time when coded attention and behavior occurred simultaneously).

Interaction terms were created by multiplying predictor variables (Aiken & West, 1991). Significant interactions were plotted with regions of significance using the Johnson-Neyman method (Johnson & Neyman, 1936).

Results

Tables present descriptive statistics (Table 1) and Pearson correlations among study variables (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, minimum and maximum values, and skewness of study variables

| M | SD | Min | Max | Skewness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 6.05 | 0.62 | 5.02 | 7.01 | −0.09 |

| BI | 99.55 | 26.00 | 43.00 | 149.00 | −0.28 |

| Parent Anxiety | 3.75 | 4.63 | 0.00 | 20.00 | 1.57 |

| Proportion Parent Face | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 2.07 |

| Proportion Parent Body | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 2.03 |

| Proportion Parent Reference | 0.14 | 0.10 | <0.01 | 0.37 | 0.80 |

| Proportion Puzzle Task | 0.77 | 0.11 | 0.49 | 0.96 | −0.68 |

| Proportion Other | 0.06 | 0.05 | <0.01 | 0.20 | 0.89 |

| Proportion Parent | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.39 | 0.65 |

| Proportion Positive Reinforcement | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.27 |

| Proportion Teaching | 0.26 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.63 | 0.90 |

| Proportion Directives | 0.24 | 0.13 | <0.01 | 0.61 | 0.65 |

| Proportion Intrusion | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 3.59 |

| Total Grid Cells Visited | 9.50 | 2.30 | 5.00 | 16.00 | 0.25 |

| AMD Task-Focus/Pos. Parenting (ms) | 1741.75 | 637.16 | 784.53 | 3075.06 | 0.40 |

| AMD Par.-Focus/Con. Parenting (ms) | 773.73 | 805.96 | 0.00 | 5313.00 | 4.42 |

| SSG Proportion Coded | 0.40 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.71 | −0.27 |

Note. BI = Behavioral Inhibition; AMD = Average Mean Duration; Par-Focus/Con. Parenting = Parent-Focused/Controlling Parenting; SSG = State Space Grid. “Proportion Parent” collapses across face, body, and reference. “Task-Focused/Positive Parenting” states are dyadic states that contain looking behavior to the puzzle task and parent engagement in positive reinforcement and teaching behaviors. “Parent-Focused/Controlling Parenting” states are dyadic states that contain looking behavior to the parent (face, body, reference) and parent engagement in directives and intrusion. “SSG Proportion Coded” indicates what proportion of the video was codeable in the state-space grids (i.e., states where both looking behavior and parenting behavior occurred simultaneously).

Table 2.

Pearson correlations among age, BI, anxiety, and proportion scores

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | ---- | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.18 | −0.10 | 0.10 | 0.06 | −0.14 | −0.06 | −0.21 | 0.17 | −0.18 |

| 2. BI | ---- | ---- | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.26 | −0.17 | 0.03 | 0.16 | −0.12 | 0.19 | 0.35 * | −0.01 | −0.22 |

| 3. Parent Anxiety | ---- | ---- | ---- | −0.18 | 0.18 | 0.07 | −0.20 | 0.37 * | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.26 | −0.26 | −0.16 |

| 4. Prop. Parent Face | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | 0.17 | −0.32* | 0.04 | 0.12 | −0.11 | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.12 | −0.13 |

| 5. Prop. Parent Body | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | 0.00 | −0.24 | 0.29 † | 0.12 | −0.05 | 0.20 | −0.07 | −0.04 |

| 6. Prop. Parent Ref. | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | −0.85** | −0.07 | 0.97 ** | −0.24 | 0.26 | −0.02 | 0.33 * |

| 7. Prop. Puzzle | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | −0.43** | −0.89** | 0.21 | −0.32* | 0.28 † | −0.27* |

| 8. Prop. Other | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | −0.03 | 0.05 | 0.16 | −0.46** | −0.11 |

| 9. Prop. Parent | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | −0.25 | 0.28 † | −0.08 | 0.35 * |

| 10. Prop. PosR | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | 0.15 | 0.29 † | −0.28† |

| 11. Prop. Teaching | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | −0.31† | −0.26† |

| 12. Prop. Directives | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | −0.20 |

| 13. Prop. Intrusion | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

BI = Behavioral Inhibition; Prop. = Proportion; Ref. = Reference; PosR = Positive Reinforcement;

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 3.

Pearson correlations among age, BI, anxiety, and dyad scores

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | ---- | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.26 | −0.04 | −0.14 |

| 2. BI | ---- | ---- | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.15 |

| 3. Parent Anxiety | ---- | ---- | ---- | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.25 |

| 4. Total Grid Cells Visited | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | −0.26 | 0.08 |

| 5. AMD Task-Focus/Pos. Parenting | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | −0.21 |

| 6. AMD Par.-Focus/Con. Parenting | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

BI = Behavioral Inhibition; AMD = Average Mean Duration; Task-Focus/Pos. Parenting = Puzzle AOI, Positive Reinforcement and Teaching; Par.-Focus/Con. Parenting = Parent AOIs, Directives and Intrusion.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Aim 1: Relation between BI and Proportion of Time Spent Referencing the Parent.

The zero-order correlation between child BI level and proportion of time spent looking to the parent during the task was not significant.

Aim 2: Relation between BI and Proportions of Time Spent in Parenting Behaviors.

Child BI level was not significantly correlated with the proportion of parent’s time spent in positive reinforcement, directives, or intrusion. However, child BI level and proportion of parent’s time spent in teaching were positively related.

Aim 3: Relation between Parent Anxiety and Proportions of Time Spent in Parenting Behaviors.

Parent anxiety level was not associated with proportion of parent’s time spent in positive reinforcement, teaching, directives, or intrusion.

Aim 4: State Space Grid Analyses to Test Relations between Attractors, Child BI, and Parent Anxiety.

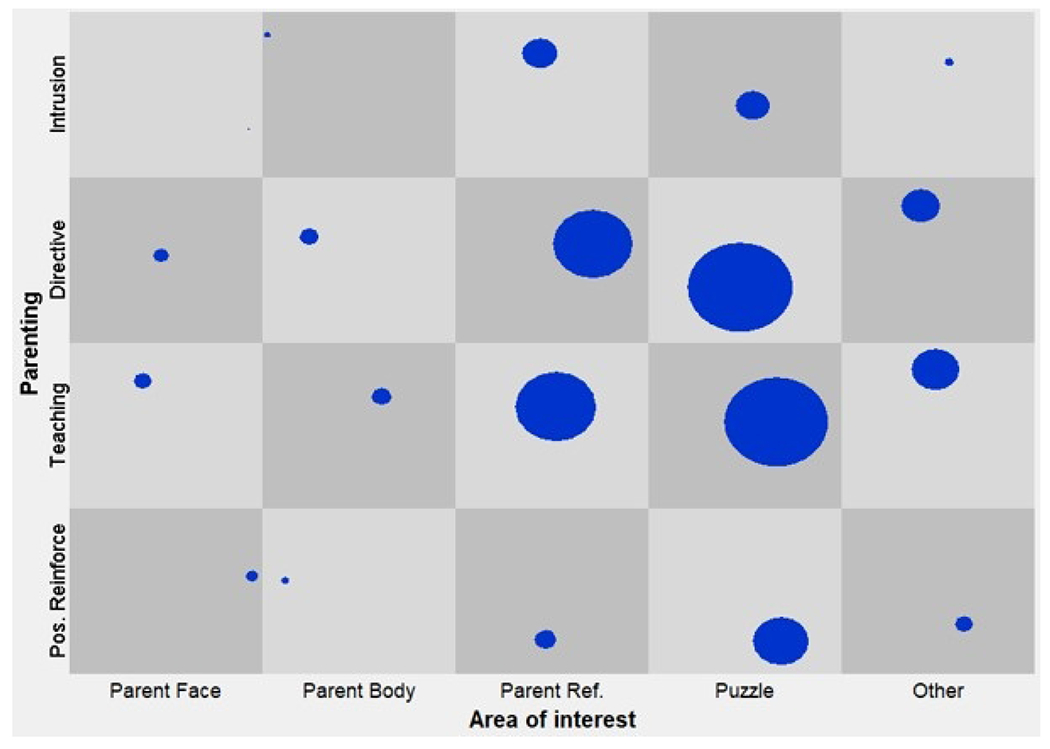

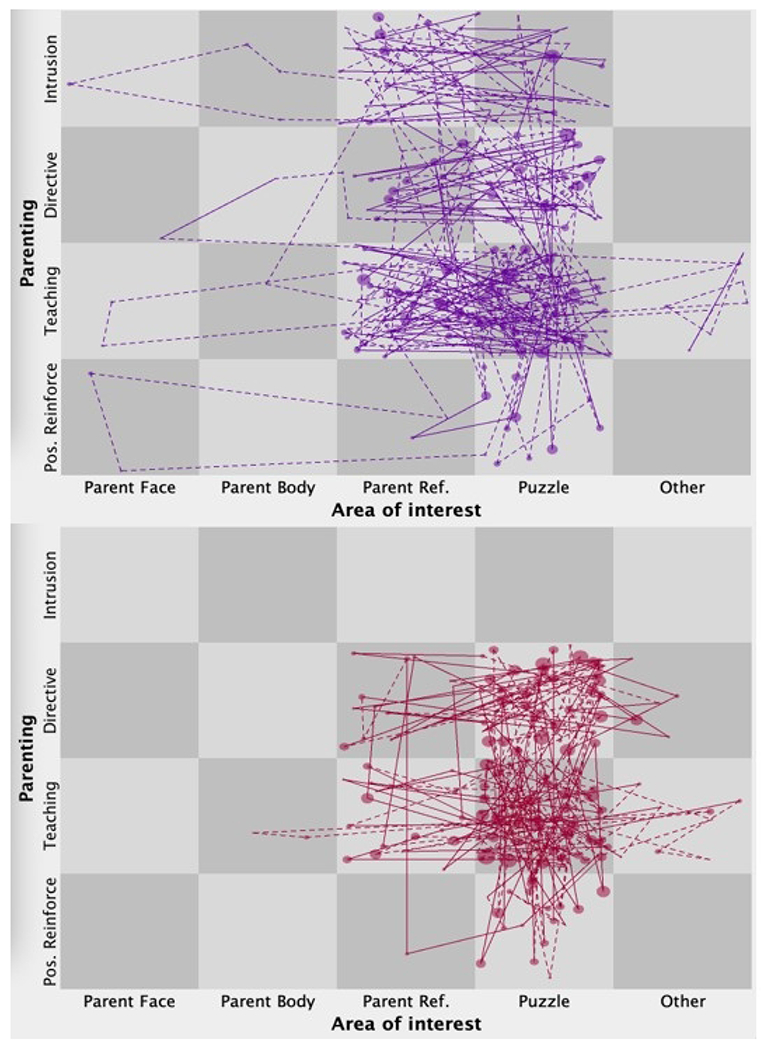

Figure 2 depicts a summary grid of the total time spent in each dyadic state across all dyads, visually demonstrating that dyads spent a longer duration of time overall in states where the child was looking at the parent reference or puzzle while the parent engaged in teaching or directives. Intraindividual variability in dyadic behavior for two unique dyads is demonstrated in Figure 3. Means for all study variables are presented in Table 1. On average, dyads visited 9.50 out of 20 total cells during the task (SD = 2.30; Range = 5.00 – 16.00). Average mean duration across participants was 1741.75 milliseconds (SD = 637.16 milliseconds; Range = 784.53 – 3075.06 milliseconds) in task-focused/positive parenting states and 773.73 milliseconds (SD = 805.96 milliseconds; Range = 0.00 – 5313.00 milliseconds) in parent-focused/controlling parenting states.

Figure 2.

Summary grid of total time spent in each dyadic state across all dyads. Ref. = Reference; Pos.Reinforce = Positive Reinforcement.

Figure 3.

Intraindividual variability of dyadic behavior. State space grid examples of two individual dyads. Dotted lines connect event nodes prior to missing events to nodes that follow the missing events. Ref. = Reference; Pos. Reinforce = Positive Reinforcement.

The first moderation model examining the effects of child BI, parent anxiety, and their interaction predicting task-focused/positive parenting attractor strength was not significant, F(4,35) = 0.90, p = .48, R2 = 0.09 (Table 4). Therefore, none of the effects were considered statistically significant.

Table 4.

Liner regression model predicting attractor strength in task-focused/positive parenting states

| Variable | Estimate | SE | t | F | df | R2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Model | 0.90 | 4, 35 | .09 | .48 | |||

| Intercept | 1784.47*** | 104.01 | 17.16 | ||||

| Proportion Coded | 369.72 | 627.08 | 0.59 | ||||

| BI | 0.60 | 4.10 | 0.15 | ||||

| Anxiety | 21.31 | 26.60 | 0.80 | ||||

| BI x Anxiety | −1.55† | 0.86 | −1.81 |

Note. Estimates are unstandardized regression coefficients. SE = Standard Error. BI = Behavioral Inhibition.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

The second moderation model examined the effects of child age, child BI, parent anxiety, and their interactions predicting parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength (Table 5). McFadden’s pseudo-R2 for the total model was .21. Child age was negatively related to parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength, suggesting that younger children spent more time at each visit in the parent-focused/controlling parenting states. Parent anxiety was positively related to parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength, suggesting that parents with higher levels of anxiety spent more time in parent-focused/controlling parenting states at each visit with their child. Proportion of coded data was positively related to parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength.

Table 5.

Generalized linear model assuming a Gamma distribution predicting attractor strength in parent-focused/controlling parenting states

| Variable | Estimate | SE | t | df | Pseudo R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Model | 7, 32 | .21 | |||

| Intercept | 6.50 *** | 0.10 | 67.75 | ||

| Proportion Coded | 1.89 ** | 0.57 | 3.29 | ||

| Age | −0.42* | 0.16 | −2.61 | ||

| BI | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 1.12 | ||

| Anxiety | 0.06* | 0.03 | 2.10 | ||

| BI x Age | < 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.12 | ||

| Anxiety x Age | −0.11* | 0.04 | −2.57 | ||

| BI x Anxiety | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.48 |

Note. Estimate results are estimated coefficients from the generalized linear model. SE = Standard Error. BI = Behavioral Inhibition.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

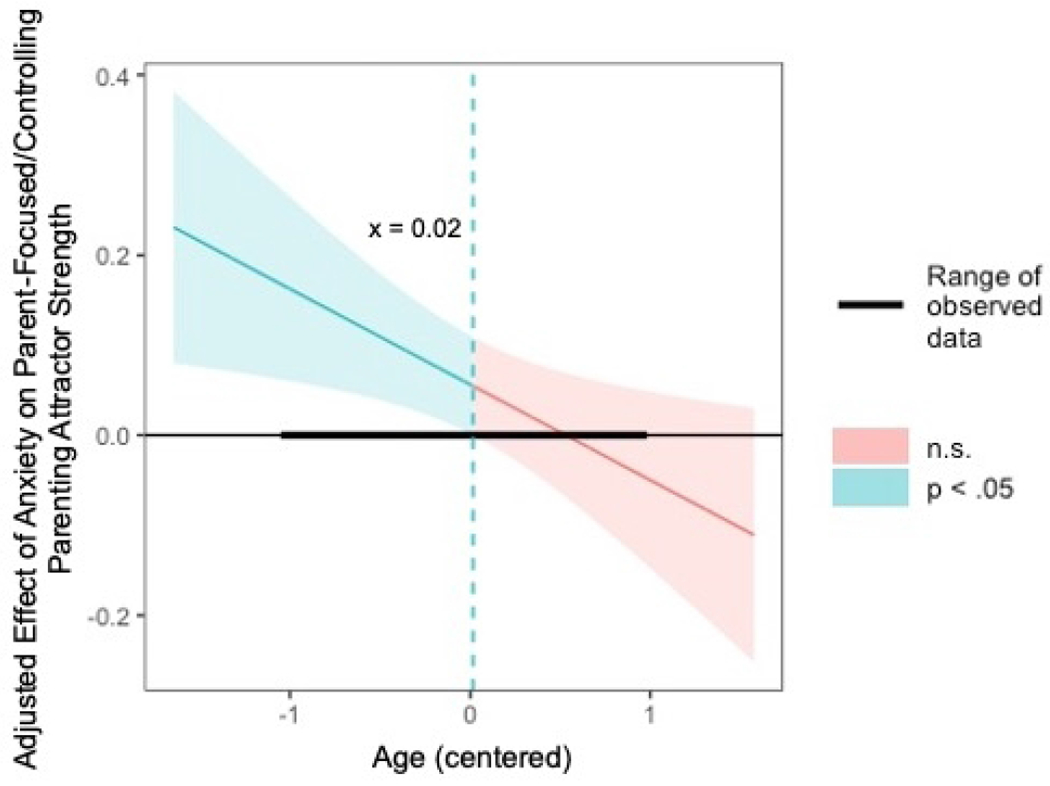

The interaction between parent anxiety and child age significantly predicted parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength. The regions of significance test, demonstrated in Figure 4, indicated that parent anxiety level was positively related to parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength for children ages 0.02 above the mean (6.07 years) and younger. For children older than 6.07 years, there was no significant relation between parent anxiety level and parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength. The interaction between child BI and age was not significant, nor was the interaction between child BI and parent anxiety level.

Figure 4.

The interaction between parent level of anxiety and child age predicting parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength. Y-axis portrays the continuous range of values for the adjusted effect of anxiety level on attractor strength. Diagonal line represents values of the adjusted effect that correspond to age values. Curved area represents 95% confidence bands around the adjusted effect. Regions of significance analyses indicated that parent level of anxiety was positively related to parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength for children ages 0.02 (mean centered) and younger.

Discussion

The current study used mobile eye-tracking to investigate children’s naturalistic attention patterns in a challenging and novel task with their parent. This study is one of the first to capture how children visually attend to their parent’s behaviors during a real-life interaction, enabling relatively ecologically valid measurements of how child attention and parenting behavior co-occur in parent-child interactions. The extant literature has strived to understand how parents behave in the context of their child’s BI (Hastings et al., 2019). A large assumption of this literature is that the parent sends a message to the child that they require help in novel situations. The current study adds to the existing literature by examining whether school-aged children attend to controlling behaviors from parents versus the task at hand, as well as whether these attention patterns depend on the level of anxiety risk in the parent-child dyad.

Aim 1: Relation between BI and Proportion of Time Spent Referencing the Parent

The first aim of the study examined whether the child’s level of BI was related to their time spent referencing the parent during the challenging task. We expected that children higher in BI would look more to their parents during the task, given the previous work suggesting that more fearful children tend to elicit, or look for, more support from their social environment (de Rosnay et al., 2006; Rubin et al., 2002; Rubin et al., 1997). However, our hypothesis was not supported. This was the first study to directly measure individual differences in children’s looking time to the parent during an interactive task in the context of child BI. While previous literature has found that parents engage in more overcontrolling parenting with temperamentally fearful children than with non-fearful children (Hastings et al., 2019), the ways in which children evoke these behaviors is largely understudied.

It is important to note that while there was variability in looking time to the parent overall (2–39% of the task), children spent on average 1% of the task looking to the parent’s face and less than 1% of the task looking at the parent’s body, distinct from the parent’s physical reference to the task. When children looked to the parent, they spent most of that time looking at the part of the task the parent was referencing, rather than the parent’s face or body. These findings are consistent with the existing, albeit small, mobile eye-tracking literature. Recent work from Jung, Zimmerman, and Pérez-Edgar (2018) found that during a child’s 30-minute museum exploration session, the child spent only 43 seconds fixating on his mother. Franchak and colleagues (2018) found a similar pattern of looking behavior, such that crawling infants looked at parents only 4% of the time and walking infants looked at parents 4.8% of the time during a parent-infant free-play session.

One possible reason for why children did not fixate on parents’ bodies or faces is that they did not need to look at the parent to engage them in task-related behavior. In contrast, children attended to parent referencing for 14% of the session, on average. Research in infants has found that hands provide a better cue for attention engagement than a face (Yu & Smith, 2013, 2017). The children in our study, therefore, may be directing attention to the parent’s hands or the task during parent behavior, or to initiate parent help, rather than the face given the demands of this particular task. Also, children may attend to their parent’s speech more than they attend to their face. The current study examined child attention only during a structured teaching task with a built-in incentive, which may explain why the child’s attention was heavily task-focused overall. Future research may benefit from examining child attention across a range of parent-child tasks while coding for emotional expressions. For instance, an unstructured free-play task may elicit a wider range of emotions for both the parent and the child, which may cause children to look to their parent’s face more often to engage with and interpret their emotions, as emotions are often expressed by the face. A free-play task would also change the goal of the task from one that is heavily structured to ones that are governed by the individual children and their parents.

Aim 2: Relation between BI and Proportions of Time Spent in Parenting Behaviors

The second aim of the study examined whether children’s level of BI was related to different parenting behaviors. In contrast to our hypotheses focused on controlling behaviors, such as directives and intrusion, we found that child BI was positively related to parent’s proportion of time spent teaching. Positive reinforcement, directives, and intrusion were not related to BI levels. Previous research has found that parents of inhibited children often engage in more directive and intrusive behaviors, perhaps as ways of alleviating stress or preventing the onset of distress (Hastings et al., 2019). In doing so, they decrease opportunities for encouraging their children to take part in important learning situations (Chronis-Tuscano, Danko, Rubin, Coplan, & Novick, 2018).

The current study used a challenging teaching task that was likely to elicit more solicitous behaviors from parents so that the child would stay engaged to complete the task. Rubin and colleagues (2001) found that when mothers and children engaged in a challenging task and a free-play task, mothers’ solicitous behaviors in the free-play task predicted more reticence with peers, while these same behaviors predicted less reticent behavior when observed in the challenge task. Therefore, more controlling behaviors might be expected in this type of task, regardless of BI level. Further, the incentive to complete the task may have placed additional pressure on parents to engage in more goal-directed behaviors than they would have if the task was not incentivized. Parents in the current study may have engaged in more teaching behaviors with their high BI children because these parents may be aware of how their children typically respond in challenging situations, responding in a relatively sensitive and calm manner. The sample in the current study was relatively homogenous, and the relation between teaching and BI may not generalize to diverse populations with a larger distribution of risk.

Another possible reason for why particular parenting behaviors were not related to child BI was the amount of time these behaviors actually occurred during the task. Intrusion, for instance, only occurred for 2% of the task on average and was positively skewed. This marked lack of variability could have contributed to the non-significant relation between BI and intrusion. The current sample was relatively homogenous and healthy, which may explain the low occurrence of intrusion. Also, because parents were specifically instructed not to move the pieces for the child, it is likely that this instruction impacted the likelihood that parents would demonstrate intrusive behavior. A structured teaching task without this explicit rule may have allowed for more variability in intrusion and a potential significant association with BI. However, the occurrence of intrusion when parents are explicitly instructed not to intrude may reveal when intrusion is most problematic. Alternatively, intrusion may serve as a last-resort strategy for parents when working with their specific child. A next step for this research is to code other child behavior, in addition to looking behavior, to contextualize these relatively infrequent parenting behaviors.

Aim 3: Relation between Parent Anxiety and Proportions of Time Spent in Parenting Behaviors

The third aim of the study examined whether parent level of anxiety was related to different parenting behaviors during the puzzle task. We predicted that higher levels of anxiety would be related to spending more time in directives and intrusion and less time in positive reinforcement and teaching. However, we found no significant relations. Previous work suggests that socially anxious mothers promote less autonomy during a challenging task with their infants than non-anxious mothers (Murray et al., 2012), and parents’ levels of anxious behaviors are higher under challenging conditions (Ginsburg, Grover, Cord, & Ialongo, 2006). Therefore, it was surprising to find that the parent’s level of anxiety was not related to any of the observed parenting behaviors. The mean anxiety score in the current sample was relatively low (M = 3.75) and positively skewed (skewness = 1.57), thus there may not have been enough variability to detect significant correlations with parenting behavior alone. The positive skewness for anxiety in a community sample is unsurprising (e.g., Costa & Weems, 2005), however, many studies relying on community samples find associations with maternal anxiety and parenting (e.g., Stevenson-Hinde, Shouldice, & Chicot, 2011). Although the use of a community sample in the current study helps limit bias and confounding variables common in clinical samples, it may have limited the range of parental anxiety symptoms. In a clinical sample, we may expect to find positive associations between parental anxiety and directive and intrusive behavior, as parents with clinical levels of anxiety have demonstrated more controlling behaviors (e.g., Hirshfeld, Biederman, Brody, Faraone, & Rosenbaum, 1997; Murray et al., 2012).

However, one meta-analysis examining relations between parent anxiety and parent control found no significant effect (Van der Bruggen, Stams, & Bögels, 2008). The authors note that anxious behaviors were not triggered during the tasks where controlling parenting was measured, suggesting that parents who score high on survey measures for trait anxiety may only be controlling in the situations that foster their own anxiety. Parent anxiety can also promote withdrawal (Woodruff-Borden, Morrow, Bourland, & Cambron, 2002).

The current study used the Beck Anxiety Inventory (Beck et al., 1988), which covers common symptoms of anxiety for severity or level. Previous work with anxious parents has used symptoms or diagnoses of specific anxiety disorders, such as social anxiety (Murray et al., 2012), or anxiety-related behaviors (Ginsburg et al., 2006). Capturing symptoms of specific anxiety disorders or anxiety-related behaviors, in addition to parenting behaviors, could have provided a more comprehensive assessment of parental anxiety with which to measure anxiety’s relation to other critical parenting behaviors. Future research should examine a broad range of anxiety-related symptoms and behaviors, including withdrawal, in parent-child interactions in both community and clinical samples.

Aim 4: State Space Grid Analyses to Test Relations between Attractors, Child BI, and Parent Anxiety

Finally, we used state space grids to visualize and generate within- and between-dyad differences in children’s gaze patterns and parenting behaviors as they co-occurred during the dyadic interaction, as well as whether these patterns depended on the child’s level of BI and the parent’s level of anxiety. To summarize these dynamic relations, we computed attractor strength of dyadic states that may be considered more positive (i.e., task-focused/positive parenting) and more negative (i.e., parent-focused/controlling parenting). Stronger attractor strength represents a behavioral exchange that the dyad may be attracted to, or rely upon, during this challenging interaction that may demonstrate adaptive or maladaptive family processes. Examining proportions of looking behavior or parenting behavior alone provides little new information for the potential mechanisms linking parenting and BI to children’s socioemotional functioning. By examining looking behavior and parenting simultaneously, we can demonstrate whether levels of child BI and parent anxiety matter for the monitoring, as well as the initiation, of controlling parenting that has been theorized to contribute to the canalization of BI in children.

First, we found a negative association between child age and parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength, such that younger children spent more time in parent-focused/controlling parenting states. Younger children may rely more on parent help during this challenging task. Parents of younger children may believe that their child needs more hands-on guidance to complete the task in a timely manner. Five-year-old children have not yet entered, or have just entered, formal schooling and may not be used to tackling problem-solving situations as independently as 6- or 7-year-old children. Alternatively, parents of older children may be more likely to expect their children to attempt the task on their own with less direction.

In line with our expectations, there was a positive association between parent anxiety and parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength, demonstrating that parents who had higher levels of anxiety spent more time in parent-focused/controlling parenting states with their children. Previous work has demonstrated that anxious mothers grant less autonomy, are less warm and positive, are more critical, and catastrophize more during conflict and anxiety conversations with their 7- to 14-year-old children (Whaley, Pinto, & Sigman, 1999). Parents who are anxious may struggle to manage situations that are uncertain or challenging, which may lead to controlling parenting, at least in part to alleviate their own distress (Woodruff-Borden et al., 2002). The child may respond to these controlling behaviors with their attention, as directive and intrusive behaviors imply a sense of urgency to the child.

It is important to note that child attention and parenting were measured simultaneously with the state space grids, so in some circumstances, the child may have looked to the parent before the parent engaged in controlling behaviors. Such looks to the parent could have triggered more controlling behaviors from the relatively more anxious parent. Although this is a possibility, the positive relation between parent anxiety level and attractor strength was maintained when looking to parent face and body were removed from the AMD calculation to only reflect looking to parent reference (see Supplementary Materials, Table S4). Therefore, it is highly likely that child gaze followed the parent during times of directives and intrusion. Future studies should use time lagged models to examine how child gaze and parenting behavior predict one another across the interaction to disentangle when attention motivates parenting behavior from when parenting behavior motivates attention.

Child age also moderated the relation between parent anxiety and parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength (Figure 4). Parents with some anxiety may have difficulties regulating their anxious behavior during a challenging and potentially stressful task with their child, particularly if they think their child might need more help due to their age or skill level. These parents may try to manage their own distress by engaging in controlling behaviors with their child (Kiel & Buss, 2012), prompting their child to attend to these controlling behaviors.

It is important to note that parent anxiety level or the interaction between parent anxiety level and child age was not associated with proportion of time spent in controlling parenting, nor were they related to proportion of looking time to the parent (see Supplementary Materials), indicating that characteristics of the child and parent were not related to parenting practices or gaze behavior alone, but rather how looking behavior and parenting operated together. These findings highlight the importance of examining parenting behavior in conjunction with child attention, as these preliminary descriptions of attention in the parenting context may have critical implications for mechanisms supporting the reliance on parents’ controlling behavior in the context of parent anxiety.

Inconsistent with expectations, parent anxiety did not moderate the relation between child BI and parent-focused/controlling parenting attractor strength in the generalized linear model (see also Supplementary Materials). According to the developmental-transactional model of child BI and anxiety (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2018; Rubin, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009), parent anxiety, child BI, and parenting undergo a transactional process across development that leads to adaptive outcomes or anxiety problems for children. Therefore, we expected that children with higher levels of BI would signal to the parent to help them during new situations, with parents responding to these “pulls” from the child by taking control of the situation for the child to alleviate any distress. The findings from the current study provide preliminary evidence for the role parental anxiety may play in dictating how long, on average, the child attends to their parent’s controlling behaviors in this type of instructional task, irrespective of child temperament.

While there is ample research to suggest that parents accommodate their behaviors and routines for their anxious child (e.g., McShane & Hastings, 2009; Rubin et al., 2001; Rubin et al., 1997), little research has studied child behavior related to parenting behavior in real time. By studying child attention patterns, we can better understand how children take in and internalize parental behavior. Visually monitoring their parent’s behavior may be the conduit by which children receive the message that they cannot complete the novel task on their own. By spending more time looking at the parent, they also may be “sending” the message of helplessness back to the parent, triggering the more anxious parent to engage in controlling behaviors.

Although attractor strength in parent-focused/controlling parenting states was non-normally distributed, we also examined a linear model as a test of sensitivity and robustness of the results from the generalized linear model (see Supplementary Materials). The results were maintained across models. In addition, the child BI by parent anxiety level interaction was significant in the linear model, suggesting that children with higher levels of BI and parents with higher levels of anxiety, on average, may have spent more time in states where the child looked to the parent while the parent engaged in controlling behaviors. The findings across models demonstrate while there is some preliminary evidence for dyads at most anxiety risk spending more time in these parent-focused/controlling parenting states, more research using larger sample sizes and a full distribution of anxiety risk is needed to assess whether temperament contributes to time spent in these particular dyadic states in the context of parent anxiety. This research is particularly important in the context of the existing literature, which suggests that the ways in which BI children handle peer situations are informed by parents’ controlling behaviors. Parent anxiety, on the other hand, appears to be a relatively robust predictor of attractor strength, as evidenced by the significant association in both the linear and generalized linear models.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to measures attractors, a key concept of dynamic systems theory, using mobile eye-tracking data. Although this work is a novel contribution to the literature, these attractors must be interpreted with caution, given what little research uses mobile eye-tracking data in dynamic systems theory. The AMDs for the current study were less than two seconds for the puzzle-focused/positive parenting states and less than one second for the parent-focused/controlling parenting states. These durations are not much lower than AMDs found in other studies measuring attractors (e.g., Hollenstein et al., 2004), and looking behavior/fixations are very short in duration relative to more overt social behaviors (e.g., Range = 0.53–2.16 seconds; Franchak & Adolph, 2010; Fu et al., 2019; Yu & Smith, 2016). However, it is difficult to say whether they truly represent attractors in the most traditional sense when examining studies employing behaviors that are carried out over a larger time scale. Indeed, fixations are typically quantified as three or more consecutive frames (assuming a rate of 30 frames per second). Given the relative length in duration seen here, the AMDs in the current study, which include gaze, may be particularly meaningful. However, more research combining AMDs with mobile eye-tracking technology is needed to contextualize the current findings.

Limitations and Conclusions

While the current study is the first to examine how child looking behavior and parenting behavior co-occur in the context of child BI and parent level of anxiety, there are important limitations. First, we did not use patterns of dynamic interactions between parents and their children to predict child outcomes. The current study aimed to characterize attention and parenting patterns for children at varying levels of BI and parents at varying levels of anxiety, which can inform future longitudinal work assessing whether these patterns of dyadic behavior influence later child functioning such as the development of anxiety.

Second, participants were predominantly White, therefore these findings may not generalize to diverse populations. Third, the sample size was small for detecting interaction effects. While this sample size is comparable to, or larger than, other mobile eye-tracking studies with children (Allen et al., 2020; Franchak et al., 2018; Fu et al., 2019; Hutchinson et al., 2019; Jung et al., 2018), we were not able to collect a full distribution of risk, and it limits our ability to do more advanced modeling. Because mobile eye-tracking data collection and processing are time-intensive, it is difficult to acquire large sample sizes. Automated detection of fixation AOIs would allow for greater efficiency in processing large, within-person samples. With a larger sample size, it would be potentially meaningful for future research to explore dyadic patterns of behavior, such as attractors, for groups of dyads that incorporate children that do or do not meet criteria for a BI profile and parents that do or do not meet criteria for clinical anxiety, creating four distinct groups of dyads. There is much to be gleaned from parent-child interactions when measuring dyadic risk at the group level, as well as at what levels of symptoms contribute to dysregulated patterns of behavior at the continuous level.

Fourth, these data were acquired in the laboratory setting. Therefore, we cannot assume full ecological validity. Fifth, only five fathers participated in the current study, thus we did not control for parent gender or examine differences between parents. Although there are few studies examining the role of fathers, there is some evidence suggesting gender differences in socialization of inhibited behavior in children. For instance, fathers, and not mothers, spend a greater proportion of time attending to their daughter’s submissive emotions during a parent-child task than they do to their son’s submissive emotions (Chaplin, Cole, & Zahn-Waxler, 2005). Hudson and Rapee (2002) observed that mothers of clinically anxious children (aged 6–17) were more involved in a puzzle task than mothers of non-anxious children. This effect was not found for fathers. Fathers’ criticism, control, and negativity have been associated with young children’s withdrawn behaviors, but there is little work comparing mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behavior in the context of BI, specifically (see Hastings et al., 2019 for review). The inclusion of both mothers and fathers in research examining the parenting of inhibited children is critical for gaining a more comprehensive understanding of the development and maintenance of BI.

Lastly, the duration of missing data for the state space grids was high (M = 154.65 sec), reflecting over half the coded time. As such, we controlled for the proportion of coded data for each family for these analyses. However, the state space grid data may not have captured the scope of dyadic behaviors for these families. Additional eye-tracking data would have allowed us to analyze more dyadic behavior. For instance, parents may have engaged in the observed behaviors and the child may have attended to them, but if fixation was missing, this dyadic behavior would also be missing. In light of these limitations, and given how short in duration gaze behavior can be, the amount of data that was usable provides an important snapshot of how younger children attend to controlling behavior when parents are more anxious.

The current study demonstrates that by capturing children’s looking behavior during ecologically valid parent-child interactions, we can characterize under what circumstances children attend to their parent’s controlling behavior. Parents may play a key role in the reinforcement of anxious behaviors, controlling situations for the child that would otherwise foster autonomy and self-efficacy. The current study contributes to the literature by offering preliminary evidence suggesting that parents higher in anxiety send and receive messages that the child cannot complete such challenging tasks on their own. The use of mobile eye-tracking technology to capture social referencing from the first-person perspective allows researchers to distinguish between small and proximal AOIs that might otherwise go undocumented, enriching the examination of individual differences in attention. By integrating mobile eye-tracking into these real-life interactions between parents and their children, we can better tease apart the mechanisms underlying the parent-child dynamics that contribute to anxiety vulnerability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Preparation for this manuscript was supported by a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development T32 HD007376, Carolina Consortium on Human Development Training Program (to L.M.) and a National Institute of Mental Health grant R21 MH111980 (to K.P.E.). We gratefully acknowledge the families who generously gave their time and effort to participate in this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Declaration

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Aktar E, Majdandžić M, de Vente W, & Bögels SM (2014). Parental social anxiety disorder prospectively predicts toddlers’ fear/avoidance in a social referencing paradigm. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 77–87. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen KB, Woody ML, Rosen D, Price RB, Amole MC, & Silk JS (2020). Validating a mobile eye tracking measure of integrated attention bias and interpretation bias in youth. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 44, 668–677. doi: 10.1007/s10608-019-10071-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett PM, Rapee RM, Dadds MM, & Ryan SM (1996). Family enhancement of cognitive style in anxious and aggressive children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 24, 187–203. doi: 10.1007/BF01441484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, & Steer RA (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.56.6.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop G, Spence SH, & McDonald C (2003). Can parents and teachers provide a reliable and valid report of behavioral inhibition? Child Development, 74, 1899–1917. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00645.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen R (1996). Regression models: Censored, sample selected or truncated data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Budinger MC, Drazdowski TK, & Ginsburg GS (2013). Anxiety-promoting parenting behaviors: A comparison of anxious parents with and without social anxiety disorder. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 44, 412–418. doi: 10.1007/s10578-012-0335-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess K, Rubin KH, Cheah C, & Nelson LJ (2001). Socially withdrawn children: Parenting and parent–child relationships. In Crozier R & Alden LE (Eds.), The self, shyness and social anxiety: A handbook of concepts, research, and interventions (pp. 99–119). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Cole PM, & Zahn-Waxler C (2005). Parental socialization of emotion expression: gender differences and relations to child adjustment. Emotion, 5, 80–88. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Albano AM, & Barlow DH (1996). Cognitive processing in children: Relation to anxiety and family influences. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25, 170–176. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2502_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Danko CM, Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, & Novick DR (2018). Future directions for research on early intervention for young children at risk for social anxiety. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47, 655–667. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1426006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss JA, & Blackford JU (2012). Behavioral inhibition and risk for developing social anxiety disorder: a meta-analytic study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51, 1066–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Madsen SD, Susman-Stillman A (2002). Parenting during middle childhood. U M.H. Bornstein (Ur.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 1. Children and parenting (2nd ed., pp. 73–101). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell C, Apetroaia A, Murray L, & Cooper P (2013). Cognitive, affective, and behavioral characteristics of mothers with anxiety disorders in the context of child anxiety disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 26–38. doi: 10.1037/a0029516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]