Keywords: Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, Food choices, Alcohol use, Smoking, Lockdown

Objective:

To assess changes in daily habits, food choices and lifestyle of adult Brazilians before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design:

This observational study was carried out with Brazilian adults through an online questionnaire 5 months after the social distance measures implementation. The McNemar, McNemar–Bowker and Wilcoxon tests were used to investigate differences before and during the COVID pandemic period, adopting the statistical significance of P < 0·05.

Setting:

Brazil.

Participants:

Totally, 1368 volunteers aged 18+ years.

Results:

The volunteers reported a lower frequency of breakfast, morning and lunch snacks (P < 0·05) and a higher frequency of evening snacks and other meal categories during the pandemic period (P < 0·05). The results showed an increase in the consumption of bakery products, instant meals and fast food, while the consumption of vegetables and fruits decreased (P < 0·005). There was a significant increase in the frequency of consumption of alcoholic beverages (P < 0·001), but a reduction in the dose (P < 0·001), increased frequency of smoking (P = 0·007), an increase in sleep and screen time in hours and decrease in physical activity (P < 0·001).

Conclusions:

It was possible to observe an increase in screen time, hours of sleep, smoking and drinking frequency. On the other hand, there was a reduction in the dose of alcoholic beverages but also in the practice of physical activity. Eating habits also changed, reducing the performance of daytime meals and increasing the performance of nighttime meals. The frequency of consumption of instant meals and fast food has increased, while consumption of fruits and vegetables has decreased.

At the end of December 2019, the Chinese authorities informed on the cluster of lung infections due to unknown aetiological factors, later identified as a consequence of transmission of the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)(1). SARS-CoV-2 is part of a family of viruses common in numerous animal species, and its infection culminates in an acute respiratory disease named COVID-19, which can be asymptomatic or take on a serious clinical condition(1).

The WHO declared a Public Health Emergency of International Importance in January 2020. According to the terms of International Health Regulations, this situation represents the highest level of alert provided by WHO. This alert prompted countries to take different security measures to minimise transmission, but despite initial efforts, in March 2020, COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by WHO(2). At the beginning of May, more than 150 million cases had already been confirmed, and the number of deaths by COVID-19 was over 3·2 million, with Brazil being one of the countries with the most dramatic situation in the world: more than 15 million cases, exceeding 420 thousand deaths(3).

The transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 occurs mainly via respiratory droplets quickly, through close contact with contaminated people, and one of the main ways found to stop the spread of the new coronavirus was to establish physical and social distancing measures, in addition to other safety measures, such as washing hands frequently, sanitise places of common use, wearing protective masks and interrupt the offer of services not classified as essential(2). Among all, quarantine promoted physical distancing, considered the most effective way to prevent infection by SARS-CoV-2.

Studies carried out in different populations have already identified that the security measures adopted to face the new coronavirus, as the lockdown and home quarantine, promoted a lot of changes(4) and interfered in habits and lifestyle, including increased alcohol consumption and smoking frequency(5), reduced physical activity(6) and changes in dietary patterns and food purchases(7–9). However, studies that evaluate these changes in the Brazilian population are incipient, but already show small changes in the eating habits of adolescents(10), worsening in the quality of life of adults(11) and a possible trend of worse eating patterns in underdeveloped regions of the country(12).

Thus, further research on the behaviours before and during lockdown measures adopted in Brazil is necessary, so that it is possible to carry out necessary interventions to minimise harmful effects in terms of health and quality of life in general. Therefore, the aim of this research was to assess changes in daily habits, food choices and lifestyle of adult Brazilians before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design and participants

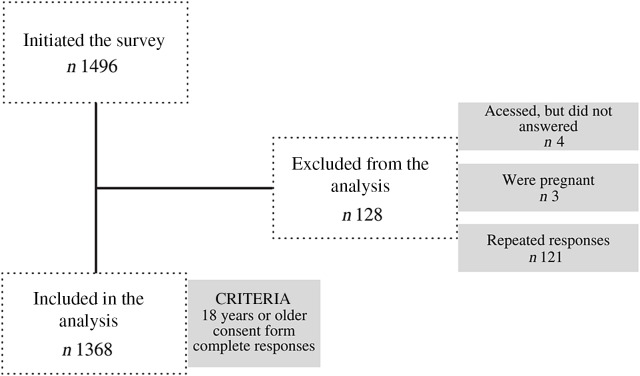

This is an observational study conducted with the Brazilian population, in which data related to daily habits (variables related to time and form of work and time of sleep), lifestyle (screen time, smoking and drinking habits and physical activity) and eating habits were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey was conducted with Brazilian volunteers, 18 years old or older, who agreed to participate and answered an online questionnaire. Pregnant women were excluded from the sample (Fig. 1). The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki(13) and was approved by the institutional Research Ethics Committee.

Fig. 1.

Study recruitment

Data collection

The online questionnaire was created on the Google Forms® search management application and was enabled for responses during 27 d from August to September 2020 – approximately 5 months after the implementation of quarantine. In Brazil, the lockdown measures implemented during that period included (1) suspension of nonessential activities (closing of restaurants, bars, shopping malls and gyms); (2) suspension of schools and universities’ activities and implementation of emergency remote education and (3) an incentive to adhere to social and physical distance measures, among other issues addressed in Federal Law No. 13 979, 6 February 2020(14). For this study, we defined the pre-pandemic period as before January 2020. Information about the survey and the link to access the questionnaire were publicised on the university’s websites and social media. The volunteers could access the questionnaire through any device that had access to the internet, and the response time was around 15 min. When accessing the link, volunteers were directed to the consent form and had the option of consenting to participate or not. Access to the form was given to those who accepted it and, after providing their contact information, the volunteers received by email a copy of the properly signed consent form.

All responses were documented anonymously and saved only when the volunteers selected the ‘Submit’ button. Thus, participants were able to stop their participation in the study at any stage before the submission of the answers. The complete survey was sent to the final database and downloaded as a Microsoft Excel archive.

Variables

The collected variables were divided into three groups of questions. The first group consisted of personal and daily habits, such as age, gender, educational level, personal income, composition of the household, the practice of quarantine, current occupation and perception about the working time during COVID-19 pandemic. The subsequent groups of questions consisted of collecting self-reported lifestyle and eating habits variables before and during the pandemic.

Concerning lifestyle, questions about frequency and dose of alcoholic beverage consumption, smoking, physical activity and sleep time were collected. The habit of drinking alcoholic beverages was investigated using frequency data (nondrinkers: rarely, once a week, 2–3 times/week, 4–6 times/ week and every day) and ingested dose. The smoking habit was investigated through categories divided into units/d. Screen time (smartphones, computer, tablet and TV) before and during the pandemic was assessed by hours, distributed as follows: <4 h/d, 5–8 h/d, 9–12 h/d, 13–16 h/d and >16 h/d. The frequency of physical activity was assessed based on six categories: 0 min/week, <90 min/week, 91–150 min/week, 151–210 min/week, 211–270 min/week and >271 min/week. Self-reported data were used to assess bedtime and wake up, and the difference between times before and during the pandemic was calculated.

To investigate eating habits, questions related to the number of meals were carried out, and an FFQ was applied. For the frequency questionnaire, the categories were (1) fresh fruits and legumes (beans, soybeans, lentils and chickpeas); (2) cereals (rice, corn and oats); (3) bakery products, meat, milk and dairy; (4) vegetables (not considering potatoes, manioc/cassava and yams); (5) instant meals and snacks (noodles, packaged snacks or crackers); (6) sweetened drinks (soda, canned or powdered juice, canned coconut water, guarana/blackcurrant syrup and sugared fruit juice); (7) candies (chocolates, pies, gum, caramel and gelatin); (8) hamburgers and canned products (ham, bologna, salami and sausage) and (9) fast food (pizza and sandwiches). For each food category, participants had the options of the frequency of consumption: never, rarely, once a week, 2 to 3 time/week, 4 to 6 time/week and once a day and more than once a day.

Statistical analysis

Data were evaluated using the Statistical Package for Social Science version 22.0 (SPSS Inc.). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied, and all variables showed a non-parametric distribution. Thus, data were presented in tables and figures, with frequency values (absolute number and percentage), as well as median and interquartile range. McNemar and McNemar–Bowker tests (Bonferroni adjusted) were used to investigate the differences in categorical variables before and during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Wilcoxon test was applied for the comparisons between numerical variables. Lifestyle habits were categorised according to the quartiles that represented the worst outcome, being: frequency of alcohol consumption equal to or greater than once a week (last quartile); dose of alcoholic beverages equal to or greater than 2·5 (last quartile); screen time equal to or greater than 10·5 h (last quartile); physical activity equal to zero minutes a week (first quartile) and hours of sleep equal to or less than 7 h (first quartile). Smoking habits were analysed among those that did not smoke and the ones that did. Based on this categorization, univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were obtained by the enter method. All the covariates with P < 0·20 on univariable analysis (see online supplemental data) were entered in the initial model. The fit of the models was tested by the Hosmer and Lemeshow test (P > 0·05). The statistical significance was determined as P < 0·05.

Results

A total of 1496 participants answered the questionnaire, and after data validation, 1368 respondents were included in the study. The median age of participants was 31·0 (24·0–39·0) years, and the sample was composed mainly of females (80·0 %), people with a complete degree (36·2 %), living with their parents (38·3 %) and practicing quarantine totally (57·2 %) or partially (39·8 %) (Table 1). Volunteers from different Brazilian regions attended the study, but most respondents (89·6 %) reside in the southeast region.

Table 1.

Participants’ general characteristics (n 1368)

| Variable | Median (Q1 – Q3) frequencies (%) | n |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 80·0 | 1094 |

| Male | 19·7 | 269 |

| No answer | 0·3 | 5 |

| Age | ||

| Years | 31·0 | 24·0–39·0 |

| Education level | ||

| Complete primary education | 0·1 | 2 |

| Incomplete high school | 0·3 | 5 |

| Complete high school | 5·1 | 70 |

| Incomplete graduation | 28·4 | 389 |

| Complete graduation | 19·4 | 266 |

| Incomplete postgraduate studies | 10·4 | 141 |

| Complete postgraduate studies | 36·3 | 495 |

| Per capita income | ||

| US$ | 347·46 | 78·37–352·68 |

| Composition of people living in the same household during COVID-19 pandemic | ||

| Alone | 8·0 | 110 |

| With friends, brothers and other | 11·1 | 152 |

| With husband/wife | 17·4 | 238 |

| With husband/wife and children/with children | 25·2 | 344 |

| With parents | 38·3 | 524 |

| Social isolation during COVID-19 pandemic | ||

| Total | 57·2 | 783 |

| Partial | 39·8 | 544 |

| No | 3·0 | 41 |

| Occupational situation during COVID-19 pandemic | ||

| Unemployed | 7·3 | 100 |

| Retired | 3·3 | 45 |

| Work/study remotely full time | 40·6 | 555 |

| Work/study remotely part-time | 30·1 | 412 |

| Work/study unchanged, not remotely | 11·0 | 150 |

| Other | 7·7 | 106 |

| Perception of working time during the pandemic (including housework) | ||

| Increased | 65·9 | 902 |

| Decreased | 12·8 | 175 |

| Remained the same | 21·3 | 291 |

There were significant differences between the periods before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, considering the frequency of alcohol consumption, smoking habits, screen time, physical activity and sleeping time (Table 2). These results indicated an increase in the frequency of consumption of alcoholic beverages, but a reduction in the dose, an increase in the frequency of smoking, but no significant difference in the number of cigarettes smoked per day, an increase in sleep and screen time in hours and a reduction in physical activity in terms of frequency and weekly minutes.

Table 2.

Lifestyle habits before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

| Variable | Before | During | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of alcoholic beverage | n 1323 | n 1323 | |||

| Median (Q1 – Q3) | Frequency/week | 0·5 | 0·00–1·00 | 0·5 | 0·00–1·00 |

| P value | 0·022 (Wilcoxon test) | ||||

| Frequency % (n) | Nondrinkers | 26·3 % | 348 | 29·8 % | 395 |

| Rarely | 27·6 % | 366 | 29·2 % | 386 | |

| Once a week | 23·1 % | 305 | 16·9 % | 224 | |

| 2–3 times/week | 20·9 % | 277 | 18·4 % | 243 | |

| 4–6 times/week | 1·6 % | 22 | 4·9 % | 65 | |

| Every day | 0·5 % | 5 | 0·8 % | 10 | |

| P value | <0·0001(McNemar–Bowker test: 96·38) | ||||

| Dose of alcoholic beverage | n 1354 | n 1354 | |||

| Median (Q1 – Q3) | Dose per occasion | 2·5 | 0·00–2·5 | 1·0 | 0·00–2·5 |

| P value | <0·0001(Wilcoxon test) | ||||

| Frequency % (n) | None | 26·7 % | 362 | 30·2 % | 408 |

| One dose | 21·3 % | 288 | 25·9 % | 351 | |

| 2–3 doses | 22·2 % | 395 | 26·3 % | 356 | |

| 4–5 doses | 11·3 % | 154 | 9·3 % | 126 | |

| ≥6 doses | 11·5 % | 155 | 8·3 % | 113 | |

| P value | <0·0001(McNemar–Bowker test: 77·551) | ||||

| Cigarette | n 1324 | n 1324 | |||

| Median (Q1 – Q3) | Units/d | 0·00 | 0·00–0·00 | 0·00 | 0·00–0·00 |

| P value | 0·227(Wilcoxon test) | ||||

| Frequency % (n) | Nonsmokers | 94·8 % | 1255 | 95·1 % | 1259 |

| <10 cigarettes/d | 4·2 % | 57 | 3·1 % | 41 | |

| 11–20 cigarettes/d | 0·8 % | 10 | 1·2 % | 16 | |

| 21–30 cigarettes/d | 0·1 % | 1 | 0·4 % | 5 | |

| ≥31 cigarettes/d | 0·1 % | 1 | 0·2 % | 3 | |

| P value | 0·007 (McNemar–Bowker test: 19·364) | ||||

| Screen time | n 1311 | n 1311 | |||

| Median (Q1 – Q3) | h/d | 6·50 | 3·00–6·50 | 10·00 | 6·50–10·50 |

| P value | <0·0001(Wilcoxon test) | ||||

| Frequency % (n) | <4 h/d | 43·6 % | 572 | 13·6 % | 177 |

| 5–8 h/d | 37·9 % | 496 | 30·9 % | 406 | |

| 9–12 h/d | 15·4 % | 202 | 6·5 % | 86 | |

| 13–16 h/d | 2·5 % | 33 | 42·1 % | 551 | |

| >16 h/d | 0·6 % | 8 | 6·9 % | 91 | |

| P value | <0·0001(McNemar–Bowker test: 804·910) | ||||

| Physical activity | n 1347 | n 1347 | |||

| Median (Q1 – Q3) | Min/week | 120·00 | 0·00–180·00 | 80·00 | 0·00–120·00 |

| P value | <0·0001(Wilcoxon test) | ||||

| Frequency % (n) | Sedentary | 27·4 % | 369 | 38·7 % | 521 |

| <90 min/week | 16·4 % | 221 | 21·8 % | 294 | |

| 91–150 min/week | 20·9 % | 282 | 16·2 % | 218 | |

| 161–210 min/week | 14·6 % | 197 | 10·9 % | 147 | |

| 211–270 min/week | 8·5 % | 113 | 5·7 % | 77 | |

| >270 min/week | 12·2 % | 165 | 6·7 % | 90 | |

| P value | <0·0001(McNemar–Bowker test: 137·508) | ||||

| Sleep time | n 1352 | n 1352 | |||

| Median (Q1 – Q3) | Hours | 8:00 | 7:00–8:30 | 8:00 | 7:00–9:00 |

| Time to sleep (h) | 10:00 PM | 11:00 PM–4:00 AM | 9:30 PM | 11:00 PM–1:00 AM | |

| Time to wake up (h) | 6:30 AM | 6:00 AM–9:00 AM | 7:30 AM | 6:50 AM–9:00 AM | |

| P value | <0·0001(Wilcoxon test) | ||||

The number of volunteers differed between variables since not all people answered questions before and after.

Table 3 contains all factors independently associated with: consumption of alcoholic beverages equivalent to once a week or more and more than 2·5 doses or more per occasion, smoking habit, screen time per day of 10·5 h or more, do not practice any time of physical activity and sleep 7 h or less per night.

Table 3.

Independent factors associated with the lifestyle habits during the pandemic period in Brazil by multiple logistic regression analysis

| OR | 95 % CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of alcohol consumption* (≥ once a week – last quartile) | |||

| Variables (64·0 % of prediction; Hosmer and Lemeshow test = 0·246) | |||

| †Per capita income (R$) | 1·000 | 1·000, 1·000 | 0·001 |

| Living with children | 1·521 | 1·159, 1·996 | 0·002 |

| Educational level (post-graduate) | 1·599 | 1·245, 2·053 | <0·001 |

| Smoking during pandemic (cigarettes/d) | 1·077 | 1·035, 1·120 | <0·001 |

| Frequency of instant meals and snacks consumption | 0·949 | 0·903, 0·998 | 0·041 |

| Physical activity during pandemic (min/week) | 1·002 | 1·000, 1·003 | 0·022 |

| Working or studying without alterations | 2·004 | 1·399, 2·870 | <0·001 |

| Constant | 0·317 | <0·001 | |

| Dose of alcoholic beverage consumption* (≥ 2·5 doses per occasion – last quartile) | |||

| Variables (62·6 % of prediction; Hosmer and Lemeshow test: 0·200) | |||

| Gender (male) | 1·392 | 1·050, 1·846 | 0·022 |

| Living with parents | 0·765 | 0·606, 0·967 | 0·025 |

| Working or studying without alterations | 1·820 | 1·274, 2·602 | 0·001 |

| Smoking during pandemic (cigarettes/d) | 1·105 | 1·055, 1·157 | <0·001 |

| Physical activity during pandemic (min/week) | 1·003 | 1·001, 1·004 | <0·001 |

| Frequency of fresh fruits consumption | 0·953 | 0·923, 0·985 | 0·005 |

| Constant | 1·037 | 0·834 | |

| Smoking habit (yes) | |||

| Variables (92·2 % of prediction; Hosmer and Lemeshow test: 0·347) | |||

| Age (years) | 1·076 | 1·057, 1·096 | <0·001 |

| ‡Per capita income (R$) | 1·000 | 1·000, 1·000 | 0·006 |

| Educational level (post-graduate) | 0·563 | 0·348, 0·909 | 0·019 |

| Dose of alcoholic beverage during pandemic (dose per occasion) | 1·328 | 1·194, 1·478 | <0·001 |

| Daily breakfast during pandemic | 0·256 | 0·156, 0·418 | <0·001 |

| Daily afternoon snack during pandemic | 0·520 | 0·323, 0·837 | 0·007 |

| Frequency of fresh fruits consumption (times/week) | 0·933 | 0·875, 0·995 | 0·033 |

| Frequency of sweetened drinks consumption (times/week) | 1·112 | 1·048, 1·181 | <0·001 |

| Constant | 0·029 | <0·001 | |

| Screen time (≥ 10·5 h/d – last quartile) | |||

| Variables (64·7 % of prediction; Hosmer and Lemeshow test: 0·264) | |||

| Age (years) | 0·965 | 0·955, 0·976 | <0·001 |

| Remotely full/part-time work or study | 1·953 | 1·427, 2·673 | <0·001 |

| Working or studying without alterations | 0·553 | 0·345, 0·888 | 0·014 |

| Increase in time spent at work (including household chores) | 0·552 | 0·430, 0·707 | <0·001 |

| Sleep time during pandemic (h/d) | 0·859 | 0·785, 0·939 | 0·001 |

| Physical activity during pandemic (min/week) | 0·998 | 0·997, 1·000 | 0·008 |

| Daily breakfast during pandemic | 0·596 | 0·429, 0·829 | 0·002 |

| Constant | 15·294 | <0·001 | |

| Physical activity (0 min/week – first quartile) | |||

| Variables (67·6 % of prediction; Hosmer and Lemeshow test: 0·175) | |||

| Gender (female) | 1·615 | 1·181, 2·209 | 0·003 |

| §Per capita income (R$) | 1·000 | 1·000, 1·000 | 0·038 |

| Living with children | 1·478 | 1·128, 1·937 | 0·005 |

| Remotely full/part-time work or study | 0·610 | 0·471, 0·790 | <0·001 |

| Dose of alcoholic beverage during pandemic (dose per occasion) | 0·856 | 0·800, 0·915 | <0·001 |

| Sleep time during pandemic (h/d) | 0·881 | 0·805, 0·964 | 0·006 |

| Daily afternoon snack during pandemic | 0·632 | 0·465, 0·859 | 0·003 |

| Frequency of bakery products consumption (times/week) | 1·104 | 1·060, 1·150 | <0·001 |

| Frequency of fresh fruits consumption (times/week) | 0·858 | 0·827, 0·889 | <0·001 |

| Frequency of meat consumption (times/week) | 1·053 | 1·011, 1·096 | 0·013 |

| Frequency of sweetened drinks consumption (times/week) | 1·043 | 1·005, 1·082 | 0·027 |

| Constant | 2·527 | 0·039 | |

| Sleep time (≤7 h/d – first quartile) | |||

| Variables (74·0 % of prediction; Hosmer and Lemeshow test: 0·278) | |||

| Gender (male) | 1·632 | 1·195, 2·227 | 0·002 |

| Living with children | 1·433 | 1·056, 1·944 | 0·021 |

| Education level (graduation) | 1·366 | 1·043, 1·790 | 0·024 |

| Increase in time spent at work (including household chores) | 0·509 | 0·378, 0·684 | <0·001 |

| Screen time during pandemic (h/d) | 1·056 | 1·022, 1·090 | 0·001 |

| Frequency of alcoholic beverage during pandemic (times/week) | 0·900 | 0·814, 0·996 | 0·041 |

| Daily afternoon snack during pandemic | 0·591 | 0·433, 0·806 | 0·001 |

| Daily evening snack during pandemic | 1·505 | 1·143, 1·982 | 0·004 |

| Constant | 0·383 | <0·001 | |

The frequency and dose of alcoholic beverages are highly correlated habits in the evaluated population (r = 0.806; P < 0.001), and, therefore, they were causing multicollinearity and interfering in the adjustments of their respective models. Therefore, the dose of alcoholic beverages was not included as a predictor of frequency of alcoholic beverage and vice versa.

OR = 1.000095; IC = 1.000041, 1.000149.

OR = 0.999819; IC = 0.999690, 0.999949.

OR = 0.999942; IC = 0.999886, 0.999997.

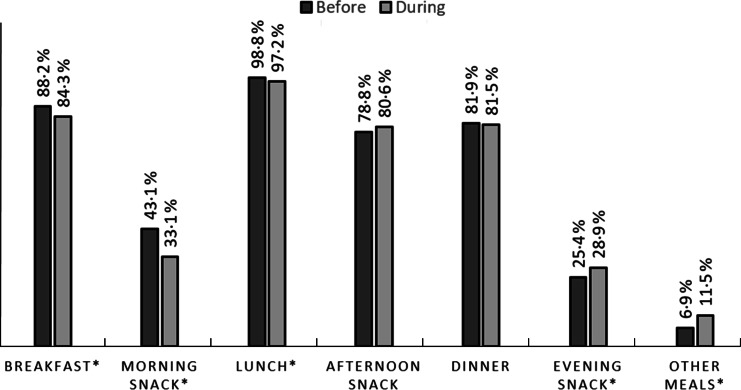

Consumption of meals changed significantly between the previous period and during the period of the pandemic, except dinner and afternoon snack (Fig. 2). The volunteers reported a lower frequency of breakfast, morning snack and lunch and a higher frequency of evening snack and other meals categories during the pandemic period.

Fig. 2.

Comparisons between meals made by participants before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (n 1368). *McNemar test, respectively: P < 0·001; P < 0·001; P = 0·002; P= 0·003; P < 0·001

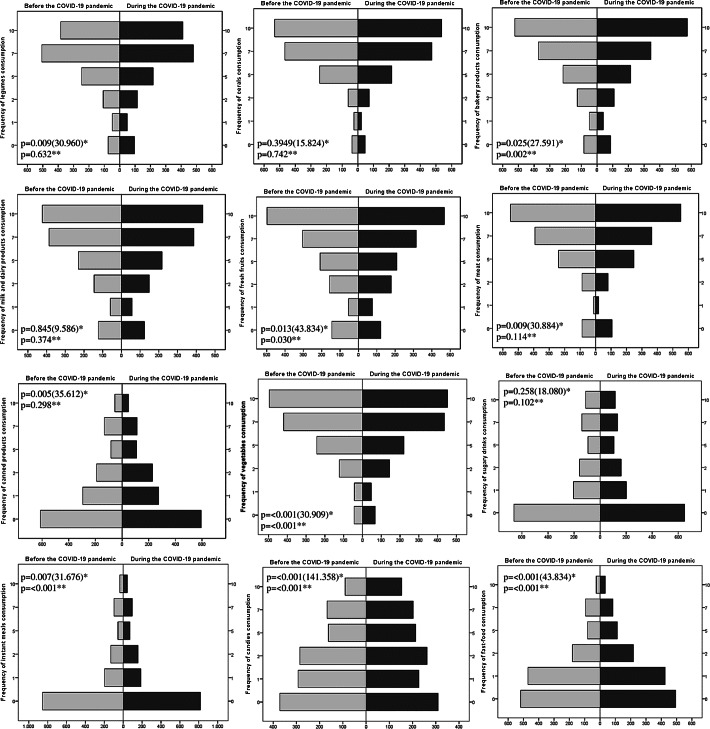

Significant differences were observed between frequency of food consumption before and during COVID-19 pandemic, such as fresh fruits, legumes, bakery products, meat, vegetables, instant meals and snacks, candies, canned products and fast food (Fig. 3). The results of this study showed a significant increase in the consumption of bakery products, instant meals and fast food, while the consumption of vegetables and fruits decreased.

Fig. 3.

Frequency of food consumption before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (n 1368). *McNemar–Bowker Test. **Wilcoxon

Discussion

This study was dedicated to investigate the changes in daily habits, food choices and lifestyle of adult Brazilians before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our main results demonstrated that there was an increase in the screen time, in the hours of sleep, in the habit of smoking and in the frequency of alcoholic beverage ingestion. In addition, eating habits have also changed, and it was possible to observe a significant increase in the consumption of bakery products, instant meals and fast food, while the consumption of vegetables and fruits decreased. Also, the quartiles that represent the worst outcomes of each lifestyle habits evaluated were associated with several factors, including age, gender, per capita income, family composition, arrangement of work adopted during the pandemic period, eating habits, among other variables of lifestyle.

Physical and social distancing is one of the main security measures to combat the spread of the new coronavirus and is highly recommended by health authorities(2). However, studies carried out with populations in other countries have shown that such measures can drastically affect life habits(5,7–9). Our results demonstrate that only 3·0 % of our sample reported not to be fulfilling physical and social distancing at the study time. Therefore, we are confident that the data allowed us to observe the outcomes of interest. The study by Malta et al.(11) also carried out with the Brazilian population also reported a similar result, in which <2 % of the participants were not in quarantine. Our sample was composed mainly of women, which has become common in research investigating eating habits during the pandemic. In other studies carried out in different countries and populations, with people in different clinical conditions and ages, women have represented more than half of the volunteers(5,8,15–18).

The frequency of alcoholic beverage intake has increased significantly during the pandemic in our sample. The increase in drinking frequency can be associated with an attempt to combat stress, boredom and possible negative emotions resulting from physical and social isolation(19). Despite the increased frequency of alcoholic beverages, the dose of consumption has significantly decreased. The decrease in the alcohol consumption/occasion differs from that of most studies that assess lifestyle and COVID-19 have consistently demonstrated(5,20,21). Along with the ban on the operation of bars and the holding of parties in Brazil, one of the possible explanations for the occurrence of these divergences is the fact that our sample is composed mainly of women. Although alcohol consumption has been growing significantly among women in the last decade, men still have a higher prevalence of excessive alcohol consumption(22). The consumption of 2·5 doses or more of alcoholic beverages per occasion was also associated with the male gender in the present study (OR = 1·392). Also, the motivations for drinking alcohol may differ according to gender: men are more likely to drink when exposed to stress, while women prefer to drink in relaxation and entertainment situations(22). In addition to our sample being composed mainly of women, more than a quarter of the interviewees reported living at home with children. Recent research has shown that women avoid consuming excessive doses of alcoholic beverages in this family composition, while men do not change this specific habit(23). Interestingly, our data showed that living with children was a predictive factor for the consumption of alcoholic beverages once a week or more in our sample (OR = 1·521). However, living with parents was inversely associated with consuming, per occasion, 2·5 doses of alcohol or more (OR = 0·765).

Although the number of nonsmokers in our sample exceeds 90 %, our results showed that during the pandemic, the number of nonsmokers decreased. While the number of cigarettes/d increased in the categories of eleven units or more, despite the recommendations of the health authorities, who issued a warning that smoking is associated with an increase in the severity of the disease and death in hospitalised COVID-19 patients and advised that all support should be given to encourage the interruption of this habit(24). Researchers have already shown that one of the reported reasons for smoking in unpleasant situations is that cigarettes seem to cause a momentary feeling of relief(25,26). Other studies also observed an increase in the number of cigarettes during the pandemic period(27,28). However, an Italian survey observed a decrease in smoking habits(8). We hypothesised that due to the atypical content of the present moment, individuals who may have previously dropped the addiction may have faced the need to resume the use of cigarettes during the lockdown, and this habit was associated with the consumption of 2·5 doses or more of alcoholic beverages per occasion (OR = 1·328) and inversely associated having intermediate meals like morning snack (OR = 0·256) and afternoon snack (0·520), in addition to consuming fresh fruits more often (OR = 0·933) and sweetened drinks less often (OR = 1·112). Previous data reported that people who quit addictions are more prone to relapses and fluctuations in atypical and high-pressure periods(29,30).

Another change observed was the increase in screen time, including television, computers, tablets and cell phones. More than half of our respondents reported an increase in working time during the pandemic – including housework. Most of the studied population reported being working/studying remotely full or part-time, and this reflects directly on screen time since people were led to adapt to a way of working called ‘intelligent’, in which the obligations are fulfilled remotely and, for the most part, online(29). Besides working or study remotely (OR = 1·953), other factors were inversely associated with 10·5 h or more of screen time during the pandemic, like being older (OR = 0·965), working or studying without changes (OR = 0·553), increased time spent on work (including household chores) (OR = 0·552) and practicing physical exercise (OR = 0·998).

Undoubtedly, the use of devices during quarantine is an important tool for communication, as they can act as facilitators and can alleviate moments of loneliness. However, in some populations, when in excess, this behaviour negatively interfered in food choices, being associated with worse food choices, including higher consumption of ultra-processed foods(31) and high consumption of snacks, fried foods and sweets(32). Unfortunately, the increase in screen time has been a reality in other populations during the pandemic, having already been demonstrated in Canadians(33) and Iranians(34) and were related to the increase in sedentary lifestyle.

The findings related to the reduction in the practice of physical activity in the present study was already expected, and they are in line with current research. Many studies carried out during pandemic found changes in behaviours related to physical activity, such as 12 % increased sitting time among individuals in Italy(35); 78 % reduction in the time of physical exercise of the Iranian population(36), 79 % among Brazilians(37) and more than 60 % in an analysis carried out in fourteen countries, compared with the period before the pandemic(38). These changes are justified by the difficulty of exercising since, among security measures, gyms, training and recreation centres and parks are closed. Additionally, the lack of necessary equipment and professional guidance are also impediments to the practice of physical activity at home(39).

Physical activity can play an important role in immune function, reducing the risk of developing and worsening chronic non-communicable diseases and obesity – risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection(6,40). Considering this, WHO has launched a guide with tips on how to include physical activity in the daily routine(41). The guide provides exercise suggestions with reference images and reinforces the recommendation that individuals practice at least 150–300 min/week of light/moderate physical activity or 75–150 min/week of vigorous physical activity(42). In addition to these benefits, physical activity can also interfere with eating habits(43) and, in our sample, the higher consumption of bakery products (OR = 1·104), meats (OR = 1·053), sweetened drinks (OR = 1·043) and the lower consumption of fresh fruits (OR = 0·858) were factors independently associated with not practicing physical activity.

An effort has also been made to encourage better eating habits in the quarantine period(44), and in this study, some changes in eating habits have been noticeable. It was observed that some people stopped having breakfast, morning snack and lunch, while they increased the performance of evening snacks and additional meals. Although there is no evidence regarding the adequate number of meals, there is a discussion that the distribution of energy and nutrients between 4 and 5 meals can have a positive effect on health, since the fractionation of meals brings relief from digestive and metabolic overload caused by higher energy density meals, in addition to contributing to the fulfillment of the recommendations of the food and nutrient groups(45). In our sample, people who reported consuming breakfast daily were less likely to smoke (OR = 0·256), as were those who had an afternoon snack (OR = 0·520). In addition, having breakfast was also inversely associated with the last quartile of screen time (OR = 0·596), while the consumption of afternoon snacks was more usual in those volunteers who practice some minutes of physical activity (OR = 0·632) and in those who sleep more than 7 h a night (OR = 0·591; P = 0·001).

Besides the reported changes in the number of meals, our volunteers also showed an increase in hours of sleep during the pandemic, and men were more likely to sleep 7 h or less (OR = 1·632). Sleeping more can justify the reduction in daytime meals and an increase in night time meals; on the other hand, meals close to bedtime can cause nighttime awakenings and worsen sleep quality and routine(46). In our sample, consuming an evening snack was a factor independently associated with the first quartile of sleep time (OR = 1·505; P = 0·004).

Although only 3·9 % of volunteers related to skipping breakfast during the pandemic period, meta-analysis studies have shown that skipping breakfast is associated with a significantly increased risk of heart disease and overweight and obesity(47,48). Breakfast skippers also had significantly worse indicators of quality of life than those who ate that meal, worse quality of the diet in general and worse perceptions of general health, social functioning, emotional role and mental health(49,50). The decrease in the consumption of morning snacks and lunch was also observed by a small percentage of the volunteers. These habits have been associated with the increase in the frequency of evening snacks that can induce worse food choices, being associated with a lower inclusion of fruits and vegetables in the diet and outcomes of higher BMI, obesogenic dietary index and a higher percentage of time eating absently(51,52).

Regarding the food choices reported by the volunteers, the results of the FFQ were very consistent in showing a worsening of the eating pattern, in which there is a decrease in consumption of fruits and vegetables and an increase in the consumption of candies and fast-food. Fruits and vegetables are rich sources of nutrients and bioactive compounds(53), while candies and fast food are usually composed of ultra-processed and energy-dense foods with a high content of sugar, saturated and trans fats and poor in most micronutrients, fibres and proteins, and it is associated with greater risks of chronic diseases with an increased risk of overweight/obesity and metabolic syndrome(54,55).

Negative changes in the food consumption profile were found in studies carried out with Brazilians(11,12) and other populations during the quarantine period(29,56,57). These changes also include low consumption of fruits and vegetables associated with increased consumption of sweets, and high consumption of snacks rich in energies, with low nutritional value(5,9). Such findings have branded a global concern that has highlighted the need to create strategies that contribute to individuals’ health and well-being and the maintenance of healthy habits that can be harmed by security measures adopted to face the pandemic(4–8,18,19,27,39,58).

These results bring a perspective and a base on the changes in the habits of the Brazilian population and agree with much of what has been observed in other populations(59). In the literature, in addition to the changes observed in the perspective of worsening lifestyle habits(59) – as a worsening of the eating pattern, increased consumption of alcoholic beverages, increased sedentary lifestyle – attention has grown over the consequences of the pandemic on psychological and mental health aspects(17,60–62).

Although this study is on a high number of Brazilian individuals during quarantine outbreak pandemic for COVID-19, it has some limitations that deserve a discussion. The main limitation of this study is the use of a self-reported online questionnaire, which can lead to incorrect data filling and allow the participation of only people with internet access. Also, people were asked about a time before the pandemic, and very specific life/dietary issues, and some of them could not remember, or their answers may only reflect their impressions and notions on how the pandemic is affecting them. A strength of our study is the application of the questionnaire 5 months after the start of the pandemic, period of high adhesion of restrictive measures of social isolation in Brazil, being possible to notice the changes that occurred during this period.

In conclusion, the isolation measures adopted in Brazil caused changes in the daily lives of individuals, reflecting an increase in hours worked, screen time, hours of sleep, smoking and drinking frequency. On the other hand, there was a reduction in the dose of alcoholic beverages but also in the practice of physical activity. Eating habits also changed, reducing the performance of daytime meals and increasing the performance of nighttime meals. The frequency of consumption of instant meals and fast food has increased, while consumption of fruits and vegetables has decreased. Studying the repercussions of the pandemic on all these aspects is extremely important. Future studies should deepen this theme to support creating and implementing appropriate health promotion strategies in the current public health emergency.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors are very grateful to the volunteers who participated in this study. Financial support: The present study had no financial support. Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Authorship: All authors contributed substantially throughout the process of conception and design of the study, in which C.M.D.L., J.C.L., L.G.F. and L.R.A. were responsible for conception and design of the study; C.M.D.L., J.C.L., L.G.F., L.A.O. and L.R.A. participated in data collection; L.G.F., L.A.O., L.R.A., M.M.D. and T.C.M.S. participated in the analyses, interpretation of data and writing of the article. All authors carried out the critical review and approved the final version of the paper. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Viçosa, Minas Gerais, Brazil, protocol number 35516720.5.0000.5153. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898002100255X.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Burki T (2020) The origin of SARS-CoV-2. Lancet Infect Dis 20, 1018–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zanke AR, Thenge RR & Adhao VS (2020) COVID-19: a pandemic declare by world health organization. IP Int J Compr Adv Pharmacol 5, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO (2020) Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://Covid19.Who.Int/.

- 4. Scarmozzino F & Visioli F (2020) Covid-19 and the subsequent lockdown modified dietary habits of almost half the population in an Italian sample. Foods 9, 675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sidor A & Rzymski P (2020) Dietary choices and habits during COVID-19 lockdown: experience from Poland. Nutrients 12, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gallè F, Sabella EA, Da Molin G et al. (2020) Comprensión del conocimiento y los comportamientos relacionados con la epidemia por Covid-19 en estudiantes universitarios italianos: estudio EPICO (Understanding knowledge and behaviors related to CoViD-19 epidemic in Italian undergraduate students: the EPICO study). Int J Environ Res Public Health 17, 3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bracale R & Vaccaro CM (2020) Changes in food choice following restrictive measures due to Covid-19. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 30, 1423–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Di Renzo L, Gualtieri P, Pivari F et al. (2020) Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: an Italian survey. J Transl Med 18, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pellegrini M, Ponzo V, Rosato R et al. (2020) Changes in weight and nutritional habits in adults with obesity during the “lockdown” period caused by the COVID-19 virus emergency. Nutrients 12, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ruiz-Roso MB, Padilha PC, Mantilla-Escalante DC et al. (2020) Confinamiento del Covid-19 y cambios en las tendencias alimentarias de los adolescentes en Italia, España, Chile, Colombia y Brasil (Covid-19 confinement and changes of adolescent’s dietary trends in Italy, Spain, Chile, Colombia and Brazil). Nutrients 12, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malta DC, Gomes CS, Szwarcwald CL et al. (2020) Distanciamento social, sentimento de tristeza e estilos de vida da população brasileira durante a pandemia de COVID-19 (Social distancing, feeling of sadness and lifestyles of the Brazilian population during the COVID-19 pandemic). Saúde Em Debate 44, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Steele EM, Rauber F, Costa CDS et al. (2020) Dietary changes in the NutriNet Brasil cohort during the covid-19 pandemic. Rev Saude Publica 54, 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. World Medical Association (2013) Declaration of Helsinki, ethical principles for scientific requirements and research protocols. Bull World Health Organ 79, 373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brasil (2020) Federal Law N. 13.979. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2019-2022/2020/lei/l13979.htm.

- 15. Fornili M, Petri D, Berrocal C et al. (2021) Psychological distress in the academic population and its association with socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: results from a large multicenter Italian study. PLoS One 16, e0248370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gómez-Salgado J, Andrés-Villas M, Domínguez-Salas S et al. (2020) Related health factors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17, 3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M et al. (2020) A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatry 33, 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Botero JP, Farah BQ, Correia MA et al. (2021) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic stay at home order and social isolation on physical activity levels and sedentary behavior in Brazilian adults. Einstein 19, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arora T & Grey I (2020) Health behaviour changes during COVID-19 and the potential consequences: a mini-review. J Health Psychol 25, 1155–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ingram J, Maciejewski G & Hand CJ (2020) Changes in diet, sleep, and physical activity are associated with differences in negative mood during COVID-19 lockdown. Front Psychol 11, 588604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Suffoletto B, Ram N & Chung T (2020) In-person contacts and their relationship with alcohol consumption among young adults with hazardous drinking during a pandemic. J Adolesc Health 67, 671–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Gmel G et al. (2017) Gender differences in binge drinking prevalence, predictors, and consequences. Alcohol Res Curr Rev 39, e1–e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Graham K, Bernards S, Karriker-Jaffe KJ et al. (2020) Do gender differences in the relationship between living with children and alcohol consumption vary by societal gender inequality? Drug Alcohol Rev 39, 671–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. World Health Organization (2020) Smoking and COVID-19. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/smoking-and-covid-19. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lawless M, Harrison K, Grandits G et al. (2015) Perceived stress and smoking-related behaviors and symptomatology in male and female smokers. Addict Behav 51, 80–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fidler JA & West R (2009) Self-perceived smoking motives and their correlates in a general population sample. Nicotine Tob Res 11, 1182–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Đogaš Z, Lušić Kalcina L, Pavlinac Dodig I et al. (2020) The effect of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle and mood in Croatian general population: a cross-sectional study. Croat Med J 61, 309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yan AF, Sun X, Zheng J et al. (2020) Perceived risk, behavior changes and health-related outcomes during COVID-19 pandemic: findings among adults with and without diabetes in China. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 167, 108350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barrea L, Pugliese G, Framondi L et al. (2020) Does Sars-Cov-2 threaten our dreams? Effect of quarantine on sleep quality and body mass index. J Transl Med 18, 318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Sá-Caputo DC, Taiar R, Seixas A et al. (2020) A proposal of physical performance tests adapted as home workout options during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl Sci 10, 4755. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rocha LL, Gratão LHA, Carmo AS et al. (2021) School type, eating habits, and screen time are associated with ultra-processed food consumption among Brazilian adolescents. J Acad Nutr Diet 121, 1136–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Delfino LD, Dos Santos Silva DA, Tebar WR et al. (2018) Screen time by different devices in adolescents: association with physical inactivity domains and eating habits. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 58, 318–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Woodruff SJ, Coyne P & St-Pierre E (2021) Stress, physical activity, and screen-related sedentary behaviour within the first month of the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl Psychol Health Well Being 13, 454–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ranjbar K, Hosseinpour H, Shahriarirad R et al. (2021) Students’ attitude and sleep pattern during school closure following COVID-19 pandemic quarantine : a web-based survey in south of Iran. Environ Health Prev Med 26, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Franco I, Bianco A, Bonfiglio C et al. (2021) Decreased levels of physical activity: results from a cross-sectional study in southern Italy during the COVID-19 lockdown. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 61, 294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Amini H, Isanejad A, Chamani N et al. (2020) Physical activity during COVID-19 pandemic in the Iranian population: a brief report. Heliyon 6, e05411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Martinez EZ, Silva FM, Morigi TZ et al. (2020) Physical activity in periods of social distancing due to Covid-19: a cross-sectional survey. Cienc e Saude Coletiva 25, 4157–4168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wilke J, Mohr L, Tenforde AS et al. (2020) A pandemic within the pandemic? Physical activity levels have substantially decreased in countries affected by COVID-19. SSRN Electron J 383, 2302–2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Górnicka M, Drywień ME, Zielinska MA et al. (2020) Dietary and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 and the subsequent lockdowns among polish adults: PLifeCOVID-19 study. Nutrients 12, 2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Leach RJ, Powis J, Baur LA, et al. (2020) Clinical care for obesity: a preliminary survey of sixty-eight countries. Clin Obes 10, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. World Health Organization (2020. ) Stay Physically Active during Self-Quarantine. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-technical-guidance/stay-physically-active-during-self-quarantine.

- 42. World Health Organization (2020) World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med 54, 1451–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Christofaro DGD, Werneck AO, Tebar WR et al. (2021) Physical activity is associated with improved eating habits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol 12, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. World Health Organization (2020) Food and Nutrition Tips during Self-Quarantine. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/publictions-and-technical-guidance/food-and-nutrition-tips-during-self-quarantine.

- 45. Marangoni F, Martini D, Scaglioni S et al. (2019) Snacking in nutrition and health. Int J Food Sci Nutr 70, 909–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chung N, Bin YS, Cistulli PA et al. (2020) Does the proximity of meals to bedtime influence the sleep of young adults? A cross-sectional survey of university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17, 2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Takagi H, Hari Y, Nakashima K et al. (2019) Meta-analysis of relation of skipping breakfast with heart disease. Am J Cardiol 124, 978–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ma X, Chen Q, Pu Y et al. (2020) Skipping breakfast is associated with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Res Clin Pract 14, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Huang CJ, Hu HT, Fan YC et al. (2010) Associations of breakfast skipping with obesity and health-related quality of life: evidence from a national survey in Taiwan. Int J Obes 34, 720–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pengpid S & Peltzer K (2020) Skipping breakfast and its association with health risk behaviour and mental health among university students in 28 countries. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther 13, 2889–2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Barrington WE & Beresford SAA (2019) Eating occasions, obesity and related behaviors in working adults: does it matter when you snack? Nutrients 11, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zeballos E & Todd JE (2020) The effects of skipping a meal on daily energy intake and diet quality. Public Health Nutr 23, 3346–3355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Slavin JL & Lloyd B (2012) Health benefits of fruits and vegetables. Am Soc Nutr 3, 506–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Srour B, Fezeu LK, Kesse-Guyot E et al. (2019) Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé). BMJ 365, l1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bhurosy T, Kaschalk E, Smiley A et al. (2017) Comment on ‘Ultraprocessed food consumption and risk of overweight and obesity: the University of Navarra Follow-Up (SUN) cohort study’. Am J Clin Nutr 105, 1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Eftimov T, Popovski G, Petković M et al. (2020) COVID-19 pandemic changes the food consumption patterns. Trends Food Sci Technol 104, 268–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rodríguez-Pérez C, Molina-Montes E, Verardo V et al. (2020) Changes in dietary behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak confinement in the Spanish COVIDiet study. Nutrients 12, 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Khan M & Smith J (2020) “Covibesity” a new pandemic. Obes Med 19, 100282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zupo R, Castellana F, Sardone R et al. (2020) Preliminary trajectories in dietary behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a public health call to action to face obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Facer-Childs ER, Hoffman D, Tran JN et al. (2021) Sleep and mental health in athletes during COVID-19 lockdown. Sleep 44, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mattioli AV, Sciomer S, Maffei S et al. (2020) Lifestyle and stress management in women during COVID-19 pandemic: impact on cardiovascular risk burden. Am J Lifestyle Med 15, 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Giuntella O, Hyde K, Saccardo S et al. (2020) Lifestyle and mental health disruptions during COVID-19. SSRN Electron J 118, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898002100255X.

click here to view supplementary material