Abstract

Objective

to analyse cataract surgery outcomes and related factors in eyes presenting with good visual acuity.

Subject and Methods

A retrospective longitudinal study of patients undergoing phacoemulsification between 2014 and 2018 in Moorfields Eye Hospital was conducted. Pre- and post-operative visual acuities were analysed. Inclusion criteria were age ≥40 years and pinhole visual acuity ≥6/9 pre-operatively. Exclusion criteria were no post-operative visual acuity data. The visual acuity change variable was also defined according to post-operative visual acuity being above or below the Snellen 6/9 threshold.

Results

2,720 eyes were included. The unaided logMAR visual acuity improved from 0.54 to 0.20 (p < 0.001), the logMAR visual acuity with glasses improved from 0.35 to 0.05 (p < 0.001), and the logMAR pinhole visual acuity improved from 0.17 to 0.13 (p < 0.001); 8.1% of patients had Snellen visual acuity <6/9 post-operatively. Mean follow-up period was 23.6 ± 9.9 days. In multivariate analysis, factors associated with visual acuity <6/9 post-operatively were age (OR = 0.96, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.95, 0.98], p < 0.001), vitreous loss (OR = 0.21, 95% CI [0.08, 0.56], p = 0.002), and iris trauma (OR = 0.28, 95% CI [0.10, 0.82] p = 0.02).

Conclusions

Visual acuity improved significantly, although at least 8.1% of them did not reach their pinhole preoperative visual acuity. Worse visual acuity outcomes were associated with increasing age, vitreous loss, and iris trauma. The 6/9 vision threshold may not be able to accurately differentiate those who may benefit from cataract surgery and those who may not.

Keywords: Vitreous loss, Iris trauma, Clear lens extraction

Highlights of the Study

The ongoing practice of offering earlier cataract extraction makes it crucial to identify whether patients benefit or not.

The objective of this retrospective longitudinal study is to preoperatively assess the outcomes of cataract surgery in patients with good visual acuity.

Visual acuity improved in the majority of patients.

Older age, vitreous loss, and iris trauma were associated with worse outcomes post-operatively.

Introduction

Cataract is a major health problem in people older than 50 worldwide [1], and cataract surgery is the most frequent surgical procedure performed in healthcare today [2]. Surgical techniques and instrumentation have improved significantly during the last decades improving the safety of the procedure and the visual prognosis overall [3]. This has changed the general recommendations for cataract surgery, and more patients are operated nowadays, at least in the developed world, with an early cataract and a good visual acuity at presentation or even if visual acuity can improve with glasses [4, 5, 6, 7].

The general recommendation about cataract surgery is that it is indicated when cataracts interfere with daily activities or lifestyle. Assessment of visual function is a necessity when deciding for surgery [8]. There are limited data in the literature to assess the change in visual acuity in eyes with good visual acuity before cataract surgery and the related factors that could possibly affect the outcomes. A study in the Chinese population reported that even patients with good preoperative visual acuity benefit from early cataract surgery [9]. Moreover, potential visual acuity tests and objective measures of cataract progression (such as stray light measurement and Scheimpflug photography) have limited predictive value and clinical use [10, 11].

Vision of 6/9 is still used in several units in the UK National Health Service (NHS) as a threshold so that someone can be considered eligible for cataract surgery. Analysing outcomes of cataract surgery in patients with vision of 6/9 or better may help clarify whether this threshold is justified or not. If vision improves in this group of patients, this may mean that the cut-off used may not accurately distinguish those benefitting from surgery and those who do not. More specifically, in the present study, it is assessed whether unaided, best-corrected, and pinhole visual acuity improved in these patients and whether specific intraoperative complications and related factors are associated with worse visual acuity outcomes. Considering the change in refraction following cataract surgery, the possible induction of astigmatism because of the cornea incisions (even if this is minimal) and the possibility of an intraoperative complication which may affect visual acuity post-operatively, these patients may benefit less than patients with worse visual acuity before cataract surgery. The aim of this study was to assess the outcomes of cataract surgery in patients with good visual acuity (pinhole visual acuity ≥6/9) before cataract surgery and the factors that may affect these outcomes.

Subjects and Methods

This is a retrospective longitudinal study of patients undergoing cataract surgery by a single experienced surgeon, at the level of consultant or senior fellow, able to perform independently phacoemulsification between the years 2014–2018 in Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. This study has been reviewed by the Moorfields Eye Hospital Ethics Committee and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. Inclusion criteria were age of 40 years or older, in order to exclude patients with congenital cataracts or other secondary causes which may be associated with worse visual prognosis (traumatic or uveitic cataract, etc.) and pinhole visual acuity 6/9 or higher at the time of listing for cataract surgery. Exclusion criteria included no post-operative visual acuity data. The electronic medical record software used was screened to identify these patients and extract all relevant data from their records. Amongst others, data about patient age, pre- and post-operative visual acuity (unaided, with glasses, with pinhole), the presence of intraoperative complications (posterior capsular tear, anterior capsular tear, conversion to extracapsular cataract extraction, vitreous loss, unplanned anterior vitrectomy, dropped nucleus, iris prolapse, iris trauma, hyphaema, and zonular dialysis), time of post-operative follow-up visit and post-operative subjective refraction were extracted. As best, preoperative logMAR visual acuity used the pinhole visual acuity in order to include patients in this study instead of the unaided or best-corrected vision considering that up-to-date glasses prescription was not provided for all patients and pinhole visual acuity may be a simple test to predict post-operative visual acuity in cataract patients [12, 13]. Snellen charts were used to measure visual acuity pre- and post-operatively, and consequently, logMAR visual acuities were calculated. Post-operative best logMAR VA was defined as the best post-operative visual acuity amongst unaided, best corrected, and pinhole. VA change was also defined with values: failure when post-operative VA < 6/9 and success when post-operative VA ≥ 6/9.

SPSS version 23 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analysis, and values p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant for the present study. Mean values were used for continuous variables, and odds ratios were used for categorical values; 95% confidence intervals (CI) have been used to give a range of plausible values for the parameters of interest. No statistical tests for normality have been performed because of the large sample size. Descriptive statistics were used to quantitatively describe and summarize the data. Independent samples t tests have been performed to assess associations. Multivariable logistic regression was used to identify the factors associated with VA change in the population. Only variables with n > 10 were included in the model for statistical reasons.

Results

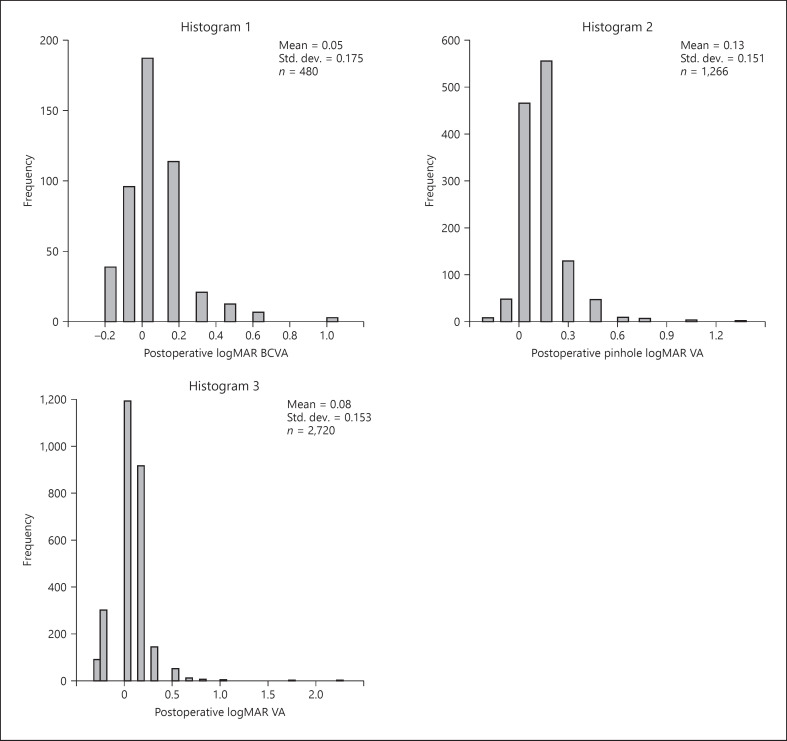

2,720 patients were included in the analysis. The mean age was 70.3 ± 10.6 years and the mean logMAR pinhole visual acuity preoperatively was 0.17 ± 0.07. The mean time for the follow-up appointment was 23.6 days, and the mean logMAR post-operative VA was 0.08 ± 0.15. Descriptive statistics of study participants and frequency of intraoperative complications are summarized in Table 1 and histograms 1–7. Posterior capsule rupture rate in our population was 22 eyes (0.8%). Visual acuity improved after surgery as all paired-sample t test comparisons were statistically significant with p < 0.001. More specifically, the unaided logMAR visual acuity improved from 0.54 ± 0.33 to 0.20 ± 0.24, the best-corrected logMAR visual acuity improved from 0.35 ± 0.19 to 0.05 ± 0.17 and the pinhole logMAR visual acuity improved from 0.17 ± 0.07 to 0.13 ± 0.15. Similarly, post-operative, best logMAR visual acuity was 0.08 ± 0.15 and significantly improved compared to the preoperative pinhole logMAR visual acuity (0.17 ± 0.07) (Fig. 1). Results of the univariate analysis are summarized in Table 2. The VA change data are summarized in Table 3. Specifically, 221 eyes (8.1%) had visual acuity <6/9 post-operatively. In the first multivariable regression model we included all statistically significant variables in the unadjusted model (age, posterior capsule tear, vitreous loss and iris trauma). In the second multivariable regression model we included the 3 factors that remained statistically significant after the first model (age, vitreous loss and iris trauma). All 3 remained statistically significant in that model, and results are summarized in Table 4. According to this adjusted model, for every year of age, subjects are 0.96 times less likely to have visual acuity above Snellen 6/9. Furthermore, patients with intraoperative vitreous loss are 0.21 times less likely to have visual acuity above Snellen 6/9. At last, patients with intraoperative iris trauma are 0.28 times less likely to have visual acuity above Snellen 6/9. Both anterior and posterior capsular tear and iris prolapse do not affect visual acuity regarding the Snellen 6/9 threshold.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and post-operative complications

| Characteristic/complication | N | Summary measure |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| mean | SD | ||

| Age, years | 2,720 | 70.3 | ±10.6 |

| [Min, max] | [40.0, 97.0] | ||

| Post-operative days until follow-up | 2,720 | 23.6 | ±9.9 |

| [Min, max] | [7.0, 97.0] | ||

| Cylindrical reading, dioptres | 1,734 | −1.12 | ±0.99 |

| [Min, max] | [–8.00, 5.00] | ||

| Spherical reading, dioptres | 1,831 | −0.11 | ±3.67 |

| [Min, max] | [–24.50, 11.25] | ||

| Complications | n | (%) | |

| No complication | 2,720 | 2,636 | (96.9) |

| Posterior capsular tear | 2,720 | 22 | (0.8) |

| Anterior capsular tear | 2,720 | 24 | (0.9) |

| Converted to ECCE | 2,720 | 2 | (0.1) |

| Vitreous loss | 2,720 | 22 | (0.8) |

| Unplanned vitrectomy | 2,720 | 23 | (0.8) |

| Dropped nucleus | 2,720 | 2 | (0.1) |

| Iris prolapse | 2,720 | 19 | (0.7) |

| Iris trauma | 2,720 | 17 | (0.6) |

| Hyphaema | 2,720 | 5 | (0.2) |

| Zonular dialysis | 2,720 | 9 | (0.3) |

Fig. 1.

Histograms showing postoperative logMAR visual acuity distribution.

Table 2.

Visual acuity comparisons

| Visual acuity (logMAR) | n | Preoperative mean ± SD [min, max] | n | Post-operative mean ± SD [min, max] | Difference mean ± SD [min, max] | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaided | 1,442 | 0.54±0.33 | 2,611 | 0.20±0.24 | 0.34±0.38 | <0.001 |

| [–0.08, 1.85] | [–0.18, 2.30] | [0.34, 0.38] | ||||

| BCVA | 1,926 | 0.35±0.19 | 480 | 0.05±0.17 | 0.30±0.28 | <0.001 |

| [–0.08, 1.85] | [–0.18, 1.00] | [0.25, 0.31] | ||||

| Pinhole | 2,720 | 0.17±0.07 | 1,266 | 0.13±0.15 | 0.05±0.15 | <0.001 |

| [–0.18, 0.18] | [–0.18, 1.30] | [0.01, 0.03] | ||||

| Best | 2,720 | 0.17±0.07 | 2,720 | 0.08±0.15 | 0.09±0.07 | <0.001 |

| [–0.18, 0.18] | [–0.18, 2.30] | [0.06, 0.07] |

Univariate preoperative and post-operative visual acuity comparisons using t test. Overall, visual acuity improved statistically significantly postoperatively in all comparisons.

Table 3.

VA change results

| VA change | Frequency | Percentage, % |

|---|---|---|

| Loss | 221 | 8.1 |

| 6/9 < Visual acuity <6/24 | 209 | 7.7 |

| 6/24 < Visual acuity <6/60 | 10 | 0.3 |

| 6/60 < Visual acuity | 2 | 0.1 |

| Win | 2,499 | 91.9 |

| Total | 2,720 | 100 |

Table 4.

Patient characteristics associated with post-operative loss of visual acuity below Snellen 6/9

| Characteristic | Unadjusted model |

p value | Adjusted model 1a |

p value | Adjusted model 2b |

p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | [95% CI] | OR | [95% CI] | OR | [95% CI] | ||||

| Age, per year | 0.96 | [0.95, 0.98] | <0.001 | 0.96 | [0.95, 0.98] | <0.001 | 0.96 | [0.95, 0.98] | <0.001 |

| Vitreous loss | 0.19 | [0.07, 0.46] | <0.001 | 0.14 | [0.03, 0.68] | 0.015 | 0.21 | [0.08, 0.56] | 0.002 |

| Iris trauma | 0.16 | [0.06, 0.43] | <0.001 | 0.28 | [0.10, 0.83] | 0.021 | 0.28 | [0.10, 0.82] | 0.020 |

| Posterior capsular tear | 0.3 | [0.11, 0.81] | 0.018 | 1.82 | [0.30, 11.1] | 0.516 | |||

| Anterior capsular tear | 0.97 | [0.23, 4.16] | 0.97 | ||||||

| Iris prolapse | 0.47 | [0.14, 1.62] | 0.23 | ||||||

CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted for all variables with p < 0.05 in the unadjusted models.

Adjusted for all statistically significant variables in adjusted model 1.

Discussion

The subgroup analysis of phacoemulsification outcomes performed in our study is important because not only is cataract surgery offered to patients earlier today, but also because clear lens extraction is considered a tool in the armamentarium of the refractive surgeon. The very first person to propose the concept of clear lens extraction for refractive reasons was Abbé Desmonceaux in 1776 [14]. Nowadays, advances in cataract surgery have changed its role from an operation primarily aiming at removing the cataractous lens to a procedure refined to yield the best possible post-operative uncorrected vision. Moreover, recent technical developments in surgical techniques and instrumentation have improved the overall safety of the procedure which encourages patients and surgeons to consider surgery at an earlier stage [4].

The idea of performing cataract surgery earlier may have to do with achieving optimal refraction post-operatively [5], or improving contrast sensitivity and optical aberrations [15] even when visual acuity can be improved with spectacles, and may not affect common daily activities. Moreover, second eye cataract surgery can be performed earlier due to anisometropia after first eye surgery [7]. Clear lens or early cataract extraction with multifocal IOL implantation may also be offered to patients as a means to correct presbyopia [16, 17]. However, intraoperative complications (such as posterior capsule rupture, zonular dehiscence, and iris trauma) or post-operative complications (such as posterior capsule opacification, cystoid macular oedema, or retinal detachment especially in long eyes) may adversely affect outcomes of cataract surgery [18, 19, 20, 21]. Even in uncomplicated surgery, visual symptoms like halos, night glare, and starbursts are not uncommon, especially with premium intraocular lenses, and these may sometimes result in unhappy patients post-operatively [22]. Another point that should be kept in mind when considering cataract surgery earlier in these patients is the cost-effectiveness ratio and the functional improvement, particularly in the NHS setting where the service demand is high and waiting lists are continually growing.

Keeping in mind all of the above, it is crucial to ascertain whether patients benefit objectively (in terms of visual acuity improvement) from early cataract surgery and which preoperative and intraoperative factors may affect the functional outcome of surgery. Our results suggest that visual acuity improved significantly overall in this group of patients, although at least 8.1% did not reach their preoperative pinhole visual acuity values post-operatively. A previous small study also suggested that functional vision in patients with best-corrected visual acuity 20/20 or better improved significantly after cataract surgery. However, no intraoperative complications were observed in that study [23]. Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis has shown that the outcome of cataract surgery did not correlate with preoperative visual acuity values [24]. The fact that visual acuity improved post-operatively in our group of patients suggests that the 6/9 threshold used to consider someone eligible for surgery cannot accurately differentiate those who benefit from surgery from those who do not. Even patients with vision of 6/9 or better preoperatively improve their vision after cataract surgery and should be considered eligible for surgery if no other issues are involved.

We found that increasing age, vitreous loss, and iris trauma are independently associated with worse visual acuity outcomes. Increasing age may be a surrogate of other pre-existing ocular pathologies (such as glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration, and early cornea endothelium failure) that may affect early post-operative visual acuity [25]. Vitreous loss is also known to be associated with early post-operative complications of cataract surgery (such as macular oedema or intraocular lens dislocation) and worse visual acuity outcomes [26]. Interestingly, posterior capsule rupture is not independently associated with worse post-operative visual acuity which underlines the importance or proper management of this complication so that chances of vitreous loss are minimized. Similarly, iris trauma was found to be associated with worse outcome and this may have to do with an increased risk of post-operative inflammation and a higher incidence of post-operative macular oedema following this complication [27].

Limitations of this study include the fact that it is a retrospective analysis; Snellen visual acuities were used to calculate logMAR, retinal pathology, and other potential factors and comorbidities (e.g., presence of diabetes mellitus and status of the corneal endothelium) that may affect outcomes were not assessed; the follow-up period was short, and some potential participants (e.g., patients with central posterior sub-capsular cataracts and patients with macular pathology) may have been excluded from our study as we decided to use pinhole visual acuity values as inclusion criteria. Most importantly, no patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have been taken into consideration. Although objective vision measurements can be very helpful in evaluating the outcome of surgery, subjective PROMs may be more important from the patient's point of view as they assess patient perspective on the outcome of surgery [28]. The main positive features of our study are the large sample size and the robust methodology. These have enabled us, not only to assess the outcomes of surgery in patients with good visual acuity preoperatively, but also to identify the factors affecting the post-operative outcomes.

Conclusion

In our subgroup of cataract patients, visual acuity improved significantly post-operatively; this suggests that the 6/9 vision threshold cannot accurately differentiate those who may benefit from surgery and those who may not. However, at least 8% of patients did not reach their pinhole visual acuity values post-operatively. We identified that older age, vitreous loss, and iris trauma were associated with worse outcomes while posterior capsule rupture without vitreous loss, independently, did not seem to affect the outcomes. Vitreous loss may be the result of posterior capsule rupture or zonular dehiscence. We believe that the pathophysiology of worse visual acuity in vitreous loss is the same regardless of whether vitreous loss is associated with posterior capsule rupture or zonular dehiscence. Thus, according to our results, posterior capsule rupture without vitreous loss should not be considered a prognostic factor for bad visual outcomes. Further research to assess PROMs is this subgroup of patients which could help evaluate the patient's perspective on the outcome of surgery.

Statement of Ethics

The present study is in compliance with ethical standards. The study has been approved by the Moorfields Eye Hospital Institutional Audit Ethics Committee and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

The authors did not receive any funding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Brian Little and Anna Praidou; methodology: Brian Little, Anna Praidou, and Nikolaos Dervenis; formal analysis and investigation: Nikolaos Dervenis; writing − original draft preparation: Nikolaos Dervenis, Anna Praidou, and Panagiotis Dervenis; writing − review and editing: Brian Little, Anna Praidou, Panagiotis Dervenis, Nikolaos Dervenis, and Dimitrios Chiras; resources: Dimitrios Chiras and Panagiotis Dervenis; supervision: Brian Little.

References

- 1.Flaxman SR, Bourne RR, Resnikoff S, Ackland P, Braithwaite T, Cicinelli MV, et al. Global causes of blindness and distance vision impairment 1990–2020: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5((12)):e1221–e34. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30393-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly SP, Astbury NJ. Patient safety in cataract surgery. Eye. 2006;20((3)):275. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haripriya A, Sonawane H, Thulasiraj RD. Changing techniques in cataract surgery: how have patients benefited? Community Eye Health. 2017;30((100)):80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessel L, Haargaard B, Boberg-Ans GE, Henning VA. Time trends in indication for cataract surgery. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;2 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falck A, Virtanen P, Tuulonen A. Is more always better in cataract surgery? Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90((8)):e653. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day A, Donachie P, Sparrow J, Johnston R. The royal college of ophthalmologists' national ophthalmology database study of cataract surgery: report 1, visual outcomes and complications. Eye. 2015;29((4)):552. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundström M, Goh PP, Henry Y, Salowi MA, Barry P, Manning S, et al. The changing pattern of cataract surgery indications: a 5-year study of 2 cataract surgery databases. Ophthalmology. 2015;122((1)):31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamaguchi T, Negishi K, Dogru M, Saiki M, Tsubota K. Improvement of functional visual acuity after cataract surgery in patients with good pre- and postoperative spectacle-corrected visual acuity. J Refract Surg. 2009 May;25((5)):410–5. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20090422-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu X, Ye H, He W, Yang J, Dai J, Lu Y. Objective functional visual outcomes of cataract surgery in patients with good preoperative visual acuity. Eye. 2017 Mar;31((3)):452–9. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vianya-Estopa M, Douthwaite WA, Funnell CL, Elliott DB. Clinician versus potential acuity test predictions of visual outcome after cataract surgery. Optometry. 2009;80((8)):447–53. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skiadaresi E, McAlinden C, Pesudovs K, Polizzi S, Khadka J, Ravalico G. Subjective quality of vision before and after cataract surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130((11)):1377–82. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melki SA, Safar A, Martin J, Ivanova A, Adi M. Potential acuity pinhole: a simple method to measure potential visual acuity in patients with cataracts, comparison to potential acuity meter. Ophthalmology. 1999;106((7)):1262–7. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)00706-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uy HS, Munoz VM. Comparison of the potential acuity meter and pinhole tests in predicting postoperative visual acuity after cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31((3)):548–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt D, Grzybowski A. Vincenz Fukala (1847–1911): versatile surgeon and early historian of ophthalmology. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011 Nov–Dec;56((6)):550–6. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu X, Ye H, He W, Yang J, Dai J, Lu Y. Objective functional visual outcomes of cataract surgery in patients with good preoperative visual acuity. Eye. 2017;31((3)):452. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Vries NE, Webers CA, Touwslager WR, Bauer NJ, de Brabander J, Berendschot TT, et al. Dissatisfaction after implantation of multifocal intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011 May;37((5)):859–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schallhorn SC, Schallhorn JM, Pelouskova M, Venter JA, Hettinger KA, Hannan SJ, et al. Refractive lens exchange in younger and older presbyopes: comparison of complication rates, 3 months clinical and patient-reported outcomes. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:1569–81. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S143201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siganos DS, Pallikaris IG. Clear lensectomy and intraocular lens implantation for hyperopia from +7 to +14 diopters. J Refract Surg. 1998 Mar–Apr;14((2)):105–13. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19980301-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laube T, Brockmann C, Lehmann N, Bornfeld N. Pseudophakic retinal detachment in young-aged patients. PLoS One. 2017;12((8)):e0184187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grimfors M, Lundström M, Höijer J, Kugelberg M. Intraoperative difficulties, complications and self-assessed visual function in cataract surgery. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96((6)):592–9. doi: 10.1111/aos.13757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schallhorn JM, Schallhorn SC, Teenan D, Hannan SJ, Pelouskova M, Venter JA. Incidence of intraoperative and early postoperative adverse events in a large cohort of consecutive refractive lens exchange procedures. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019 Sep 4;208:406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang JS, Ng JC, Lau SY. Visual outcomes and patient satisfaction after presbyopic lens exchange with a diffractive multifocal intraocular lens. J Refract Surg. 2012 Jul;28((7)):468–74. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20120612-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amesbury EC, Grossberg AL, Hong DM, Miller KM. Functional visual outcomes of cataract surgery in patients with 20/20 or better preoperative visual acuity. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35((9)):1505–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kessel L, Andresen J, Erngaard D, Flesner P, Tendal B, Hjortdal J. Indication for cataract surgery. Do we have evidence of who will benefit from surgery? A systematic review and meta–analysis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016;94((1)):10–20. doi: 10.1111/aos.12758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavallotti C, Cerulli L. Age-related changes of the human eye. Springer Science & Business Media; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ionides A, Minassian D, Tuft S. Visual outcome following posterior capsule rupture during cataract surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85((2)):222–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gulkilik G, Kocabora S, Taskapili M, Engin G. Cystoid macular edema after phacoemulsification: risk factors and effect on visual acuity. Can J Ophthalmol. 2006;41((6)):699–703. doi: 10.3129/i06-062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lundström M, Pesudovs K. Catquest-9SF patient outcomes questionnaire: nine-item short-form Rasch-scaled revision of the Catquest questionnaire. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35((3)):504–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]