Abstract

Eliciting broadly protective antibodies is a critical goal for the development of more effective vaccines against influenza. Optimizing protection is of particular importance in newborns, who are highly vulnerable to severe disease following infection. An effective vaccination strategy for this population must surmount the challenges associated with the neonatal immune system as well as mitigate the inherent immune subdominance of conserved influenza virus epitopes, responses to which can provide broader protection. Here, we show that prime-boost vaccination with a TLR7/8 agonist (R848)-conjugated influenza A virus vaccine elicits antibody responses to the highly conserved hemagglutinin stem and promotes rapid induction of virus neutralizing stem-specific antibodies following viral challenge. These findings support the efficacy of R848 as an effective adjuvant for newborns and demonstrate its ability to enhance antibody responses to subdominant antigenic sites in this at-risk population.

Keywords: influenza vaccine, newborns, HA stem, universal vaccine, antibody, adjuvant, NHP

Vaccines capable of eliciting broadly protective antibodies in newborns would be of benefit. Here we show newborn vaccination with an R848-conjugated influenza vaccine elicits responses to the conserved hemagglutinin stem and promotes rapid generation of neutralizing stem-specific antibodies following challenge.

Current influenza virus vaccines, while effective in reducing the burden of influenza, are limited by the requirement for annual updates as a result of viral antigenic drift as well as by poor effectiveness in the very young and very old. The naive status and immature immune system of newborns leaves them particularly vulnerable to the development of severe disease [1, 2]. Thus, there is a critical need to develop vaccines that are effective in these individuals. In addition, the ability to elicit broadly protective responses is a highly sought-after goal [3, 4].

The antibody (Ab) response generated by influenza vaccination protects against virus infection via direct neutralization as well as Ab-mediated innate immune cellular functions, for example, Ab-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity and Ab-dependent cellular phagocytosis [5, 6]. The hemagglutinin (HA) protein of influenza A virus (IAV) is a major target of neutralizing Ab. HA consists of a globular head containing the receptor-binding site atop a stem containing the membrane-fusion–mediating peptide. Compared to the head, the stem region is substantially more conserved, likely due to structural constraints related to its function in mediating membrane fusion [7–9]. Abs that bind sites in the globular head domain near the receptor binding site are most effective for neutralization [10]. While Abs to HA stem are less potent in this activity, they can nonetheless protect against disease in animal models [11]. Stem-specific Abs are desirable as they are broadly reactive against multiple strains [12, 13]. However, these are more challenging to elicit as Abs to stem are immunologically subdominant to the conserved head epitopes [14, 15].

Overcoming the subdominance of conserved stem epitopes is not a trivial undertaking. However, limiting the immunogen to the stem region or modifying the stem region to increase its immunogenicity has been shown to increase stem-specific Ab responses [15–19]. To our knowledge, there have been no studies investigating the immunogenicity of the HA stem region as a result of vaccination in newborns. We recently demonstrated that newborn nonhuman primates (NHP) generate robust anti-stem Ab responses following IAV infection, suggesting that the newborn repertoire is permissive for elicitation of these Abs [20]. We have also shown that the direct conjugation of R848, a small molecule Toll-like receptor 7/8 (TLR7/8) agonist, to inactivated virus can promote a more robust humoral response to vaccination and provide increased protection against viral challenge in newborn NHP compared to a nonadjuvanted vaccine; furthermore, there was no evidence of adverse inflammatory effects that might contraindicate the use of R848 as an adjuvant [21, 22]. Previous studies in adults have demonstrated that some adjuvants can increase Ab diversity and alleviate epitope subdominance, particularly upon subsequent antigen exposure [23–27]. Here we investigate a fundamental question—do newborns have the ability to produce stem-specific Abs in response to vaccination with inactivated influenza virus?. In addition, we evaluate the ability of an R848-conjugate vaccine to increase generation of these Abs.

METHODS

Animals

African green monkeys were housed at Wake Forest School of Medicine; the animal care and use protocol was adherent to the US Animal Welfare Act and Regulations and approved by the institutional animal care and use committee. Infants were removed from their mothers at 1–3 days of age and moved to individual nursery housing as described in [21].

Vaccinations

Infants, 4–6 days old, were vaccinated with inactivated A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1) (PR8) either directly conjugated to R848 or with an inactive flagellin mutant (m229), the latter serving as a nonadjuvanted vaccine. The m229 construct encodes the biologically inactive hypervariable region [28]. Utilization of this control was done in an animal sparing approach as we had also evaluated vaccines containing flagellin in another study where these animals served as the optimal control for that adjuvant [29]. Vaccines were prepared as in [21]; in brief, an amine derivative of R848 was incubated with SM(PEG)4 for 24 hours in dimethyl sulfoxide at 37°C followed by incubation with PR8 for 24 hours to produce IPR8-R848. Excess R848 was removed by dialysis. Virus was inactivated with 0.74% formalin. Each vaccine contained 45 µg of PR8. Vaccine was delivered intramuscularly into the deltoid muscle in 500 µL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Animals were boosted at day 21 postvaccination. Seven animals were given IPR8-R848, 5 animals IPR8 with m229 (nonadjuvanted), and 3 animals PBS.

Virus Challenge

At day 23–26 following boost, infants were challenged with a total of 1 × 1010 50% egg infective dose (EID50) of PR8 divided equally between intranasal and intratracheal routes. This combined route approach was selected based on prior NHP IAV challenge studies [30, 31]. Animals were sedated with isoflurane for infection and sampling. Blood was collected at day 8 and day 14 postchallenge.

Quantification of Stem-Specific Ab

Ab titers to whole HA and HA stem were assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Plates were coated overnight with 5 ng/well of recombinant PR8 HA produced in HEK293 cells [10] or a recombinant A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) HA stabilized stem (Ca09) [12]. Plates were blocked and washed with PBS plus 0.01% Tween-20. Serially diluted plasma was added in blocking buffer. Starting dilutions were as stated for each assay. Plates were washed and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-NHP immunoglobulin G (IgG; Fitzgerald) or immunoglobulin M (IgM; LifeSpan Bioscience) added for 1 hour. Plates were developed using 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB Ultra; Fisher), after which the reaction was stopped with 0.1 N H2SO4. Ab binding was determined by subtracting the OD450 value of uncoated wells from that of sample wells. The threshold for detectable signal was defined as 3 times the assay background.

Microneutralization

Microneutralization assays were performed on Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells as previously described [10]. Briefly, MDCK cells were plated at 4 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium plus GlutaMAX plus 7% fetal calf serum and allowed to reach confluency. Plasma samples were heat inactivated and 2-fold dilutions incubated with 100 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infectious dose) of a virus with a chimeric HA consisting of A/Vietnam/1203/2004(H5N1) head and PR8 stem, and N2 neuraminidase from A/Udorn/307/1972(H3N2). Samples were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Following incubation, plasma and virus mixtures were added to the MDCK cells in quadruplicate, then maintained at 37°C. Cytopathic effects were assessed after 5 days by crystal violet staining following methanol fixation.

Avidity

Avidity assays were performed as ELISAs described above with the addition of a sodium thiocyanate (NaSCN) dissociation step following sample incubation. Plasma was added at a single concentration selected for each animal based on the dilution that yielded 50% of the maximum optical density at 450 nm (OD450) in the ELISA binding curve to ensure consistency across Ab titers. Following incubation with plasma, 2-fold dilutions of NaSCN starting at 5 M were added to the plate for 15 minutes. Plates were then washed 5 times and incubated with goat anti-IgG-HRP and developed as in the ELISA protocol. The 50% maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated using GraphPad Prism software.

Statistics

Statistical significance was determined by Mann-Whitney test for pairwise comparisons or ordinary 1-way ANOVA with uncorrected Fisher least significant difference test for multiple comparisons as appropriate. All titers were log2 transformed prior to statistical analysis.

RESULTS

R848 Conjugation Improves Inactivated Virus Vaccine Prime-Boost Ab Responses to HA Stem

We previously reported that an R848-conjugated inactivated IAV vaccine increased Ab responses to IAV following vaccination of newborn NHP [21]. We hypothesized that this vaccination approach would also increase the production of a stem-specific Ab response in the newborn animals. We vaccinated 4 to 6-day-old African green monkeys (AGM) with either formalin-inactivated A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (PR8) virus (H1N1) to which R848 was covalently conjugated (IPR8-R848) or inactivated PR8 (IPR8) administered with a biologically inactive flagellin mutant protein (m229) that lacks TLR5 signaling capability, which served as a nonadjuvanted control. m229 was utilized here in an effort to minimize animal use as we had performed a previous study assessing IPR8 admixed with active flagellin for which m229 served as the appropriate control [29]. Stem-specific IgG was assessed by ELISA using a stabilized headless HA stem construct from the California/2009 pandemic strain (Ca09) [32] as the goal of eliciting stem reactive Ab is to protect from infection with heterologous strains [12].

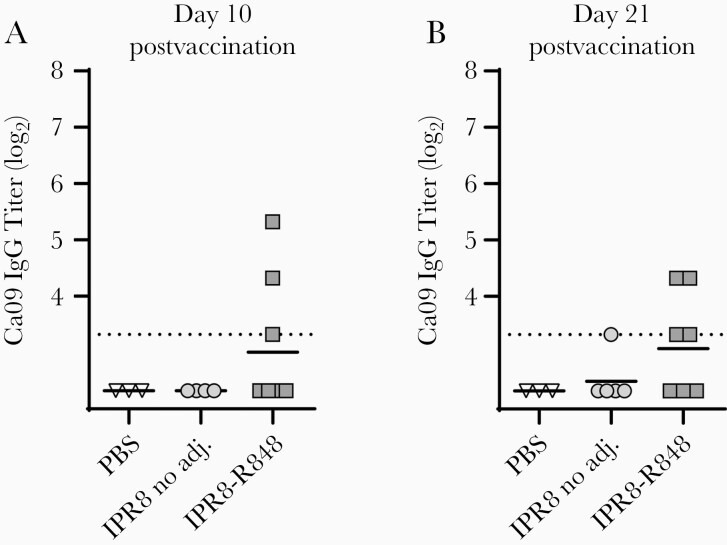

The IPR8-R848 vaccine induced Ca09 stem-specific IgG responses at or above the limit of detection in 3 (day 10 postvaccination) and 4 (day 21 postvaccination) of the 7 newborns assessed (Figure 1). In contrast, only 1 animal receiving nonadjuvanted IPR8 displayed a detectable Ab response to Ca09 stem and the threshold level of Ab was only achieved at the later (day 21 postvaccination) timepoint (Figure 1). Ca09 stem-specific Abs were not detected in nonvaccinated (PBS) newborns. Of note, the size of the response to the Ca09 stem in individual animals did not directly correspond to the titer of IgG to the whole PR8 virion measured in our previous analysis of these infants [21], suggesting the ability to detect stem-specific IgG was not simply the result of a global increase in Ab in individual animals.

Figure 1.

Primary IPR8 vaccination does not produce a consistent response to HA stem. Newborn African green monkeys were administered IPR8 with either no adjuvant (n = 4–5) or conjugated R848 (n = 7), or a vehicle control (n = 3) by intramuscular injection. Blood was drawn at day 10 (A) and day 21 (B) postvaccination and plasma collected for quantification of circulating antibody. IgG to HA stem was assessed by ELISA using plates coated with 5 ng of Ca09-stabilized stem construct and reported as threshold titer, or the lowest dilution at which sample optical density was at least 3 times that of the assay background. Each animal is designated by a distinct symbol; these symbols are consistent across timepoints to allow longitudinal visualization of individual responses. The limit of detection (dotted line) is defined as the lowest sample dilution for each assay. The line for each data set reflects the geometric mean. Abbreviations: adj., adjuvant; Ca09, A/California/04/2009 (H1N1); ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HA, hemagglutinin; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IPR8, inactivated A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1); OD, optical density; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

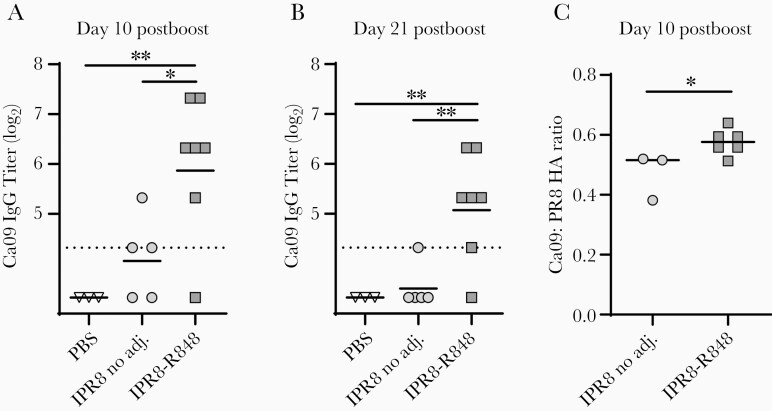

We next evaluated the effect of boosting on the HA stem-specific Ab response. Prime-boosting is standard for many Food and Drug Administration-approved vaccines and will likely be necessary in newborns. Although a traditional homologous prime-boost approach does not efficiently boost stem-specific Abs in adults, use of dendritic cell (DC)-stimulating adjuvants has been demonstrated to partially alleviate epitope subdominance upon secondary exposure [23]. To investigate whether boosting with our R848-conjugated vaccine might increase stem-specific Abs in newborns, we boosted animals at day 21 postvaccination. Following prime-boost with IPR8-R848, IgG titers to Ca09 stem were significantly higher than those in the no adjuvant group, with all but 1 animal in the IPR8-R848 vaccinated group producing Ca09 stem-specific IgG at or above the limit of detection on both day 10 and day 21 postboost (Figure 2A and 2B). While 3 of 5 animals given IPR8 without adjuvant mounted detectable Ca09 stem-specific responses by day 10 postboost (Figure 2A), titers fell below threshold 10 days later (day 21 postboost), with only 1 animal continuing to display detectable Ab (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Secondary encounter with IPR8-R848 elicits robust expansion of HA stem-specific IgG. Infant African green monkeys were boosted at 21 days after initial vaccination with the same vaccination treatment as they had previously received A and B, Plasma samples were collected and stem-specific IgG quantified as described in Figure 1. C, The relative representation of stem-specific IgG within the total HA IgG in animals with a stem-specific response was calculated as the ratio between log2-transformed titers to the Ca09 headless stem construct and PR8 HA in its native conformation. The geometric mean is shown for each data set. The dotted line represents the limit of detection for the assay. Statistical significance in (A) and (B) was determined by 1-way ANOVA, and in (C) by unpaired t test. *P < .05, **P < .01. Abbreviations: adj., adjuvant; ANOVA, analysis of variance; Ca09, A/California/04/2009 (H1N1); HA, hemagglutinin; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IPR8, inactivated A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1); PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

To examine the relationship between the magnitude of the IgG response to Ca09 stem alone and that to PR8 HA, we assessed the ratio of titers to HA and stem in the animals with detectable stem-specific Ab at day 10 postboost. While this does not provide a perfect metric for the percent of the PR8 HA response that is attributable to stem due to differences in antigen density on ELISA plates, which compromises direct comparison of numerical values, it does reflect relative differences among animals. Comparison of the IPR8-R848 versus the no adjuvant group revealed a significantly higher proportion of stem-specific IgG in animals given R848 than those vaccinated in the absence of adjuvant (Figure 2C). This result is consistent with a dampening of the subdominance of the HA stem region when the TLR7/8 agonist R848 is included during vaccination.

Animals receiving the R848 conjugated vaccine show a rapid increase in stem-specific Ab following challenge compared to those receiving the nonadjuvanted vaccine. Ideally, vaccination not only elicits pathogen-specific Abs that can provide protection from disease, but also generates memory B cells that can quickly differentiate into Ab-secreting cells and boost Ab levels following antigen reencounter. In our previous study we found the infants that received the R848 adjuvanted vaccine had more total influenza-specific Ab than their counterpart vaccinated with the nonadjuvanted vaccine following challenge, even in the face of increased clearance resulting in reduced viral load [21].

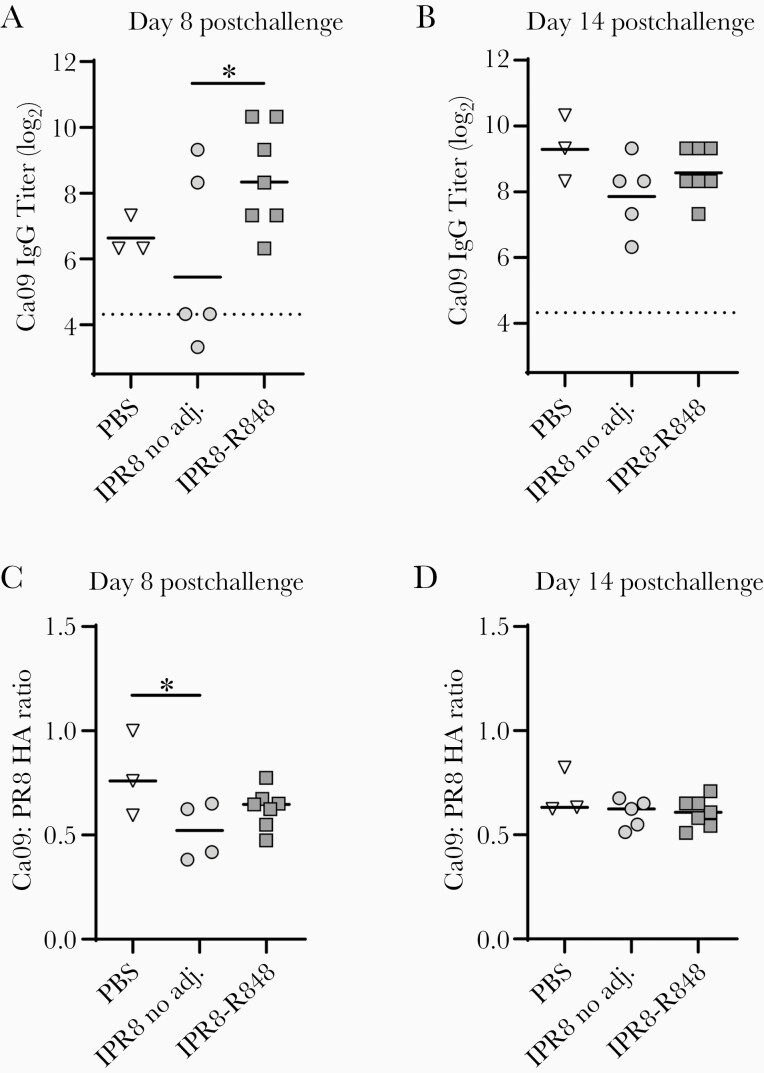

If vaccination generated memory B cells specific to the HA stem, we would expect a more rapid increase in IgG Ab following challenge compared to naive newborns. To determine the effect of infection on Ab to the Ca09 stem, we assessed Ab level at days 8 and 14 postchallenge. At day 8 postchallenge, newborns receiving the IPR8-R848 vaccine displayed a robust IgG response to Ca09 stem that was significantly higher than the IPR8 without adjuvant group (Figure 3A). The average titer was also higher than in the naive group, although this did not reach significance. Comparison of the stem-specific Ab level at day 21 postboost and day 8 postchallenge showed a significant increase in IgG to Ca09 stem in IPR8-R848 vaccinated newborns (P = .0004). This assessment was not possible in the no adjuvant group because all but 1 animal had levels below the limit of detection prior to challenge. As such, the value that would provide an accurate ratio from this calculation is not known. By day 14 postchallenge, all animals had similar levels of stem-specific Ab (Figure 3B). When the representation of stem-specific IgG relative to the total HA response was assessed, the ratio was reduced at day 8 postchallenge in the IPR8-m229 group compared to nonvaccinated infected animals (PBS) (Figure 3C), although all groups were similar by day 14 postchallenge (Figure 3D). This may reflect the poor generation of stem-specific Ab with inactivated virus vaccines [33]. Infection likely results in the most permissive environment for elicitation of these responses.

Figure 3.

Vaccination with R848-conjugated virus promotes early IgG recall response to HA stem after viral challenge. At 23–26 days following boost, all vaccinated infants as well as the PBS controls were challenged with PR8 influenza A virus. IgG titers to Ca09-stabilized stem (A and B) as well as relative representation within the total HA response (C and D) were assessed at days 8 and 14 following infection. The geometric mean is shown for each data set. Significance was assessed by 1-way ANOVA; *P < .05, ****<.0001. Abbreviations: adj., adjuvant; ANOVA, analysis of variance; Ca09, A/California/04/2009 (H1N1); HA, hemagglutinin; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IPR8, inactivated A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1); PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

To gain further insights into the early Ab response to stem in vaccinated versus naive animals, we assessed IgM titers to Ca09 stem at day 8 postchallenge. This was of interest given the efficient generation of stem-specific Ab in the naive infants. We expected that while primary encounter would elicit a robust early IgM response, a recall response would be skewed towards IgG as a result of previous class-switch recombination during differentiation. Indeed, only nonvaccinated animals produced detectable stem-specific IgM at day 8 postchallenge (Supplemental Figure 1), providing additional evidence that the IgG response in IPR8-R848 vaccinated newborns is likely the result of a recall response. Together, these data support the model that a stem-specific memory response was generated that undergoes reactivation following challenge.

Animals Receiving the R848-Conjugated Vaccine Have Higher Neutralizing Titers to HA Stem at Day 14 Postchallenge

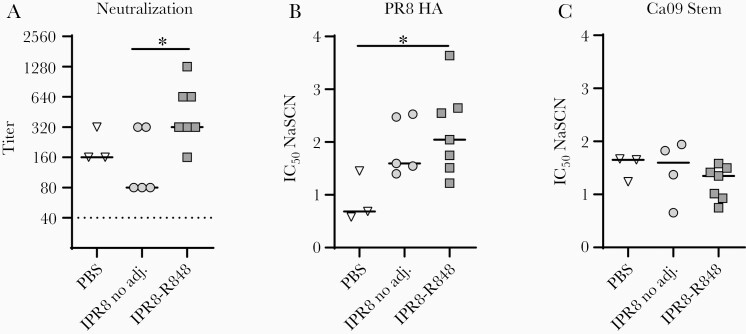

We assessed plasma neutralizing Ab to the HA stem at day 14 postchallenge by microneutralization using a chimeric PR8 construct with an H5 HA head region and N2 neuraminidase, effectively limiting binding of PR8-specific Ab to the stem region [34]. Despite the similar titers of stem-specific Ab present at day 14 postchallenge across the 3 groups, animals receiving the R848-conjugated vaccine displayed higher neutralizing titers than those receiving the inactivated virus without adjuvant (Figure 4A). Neutralization titers in the PBS group were similar to those we previously observed 14 days after infection of naive NHP [20]. These data reveal an adjuvant-dependent effect on the level of stem-specific neutralizing Ab generated following influenza virus challenge.

Figure 4.

Animals vaccinated with IPR8-R848 have higher stem-specific neutralization titers after viral challenge despite similar average avidity. A, Neutralizing capacity of stem-specific Ab present day 14 postchallenge was assessed by microneutralization assay using a chimeric virus bearing an H5 head and N2 neuraminidase to eliminate confounding neutralization to nonstem epitopes. The geometric mean is shown for each data set. The dotted line indicates the assay limit of detection. Average avidity of IgG to PR8 HA (B) and Ca09 stem (C) was calculated by determining the NaSCN concentration that gave a 50% reduction in optical absorbance compared to the untreated sample. Significance was determined by a Kruskal-Wallis test; *P < .05. Abbreviations: adj., adjuvant; Ca09, A/California/04/2009 (H1N1); HA, hemagglutinin; IC50, 50% maximum inhibitory concentration; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IPR8, inactivated A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1); NaSCN, sodium thiocyanate; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Affinity maturation is often a significant contributor to the Ab function. To determine if the higher neutralizing titer was associated with an increase in avidity, we measured the disruption of Ab binding by the presence of NaSCN. Although Ab avidity is difficult to accurately assess among polyclonal Abs, the sensitivity to chaotropic agents often correlates with Ab off-rates [26, 35]. While the average avidity of total anti-HA IgG was highest in animals that had received the IPR8-R848 vaccine (Figure 4B), no significant differences in Ab avidity to the Ca09 stem were observed across vaccine groups (Figure 4C). This finding suggests additional factors beyond avidity are responsible for the superior neutralizing capacity of the HA stem-specific Ab in IPR8-R848 vaccinated animals.

DISCUSSION

The vulnerability of newborns to IAV infection makes it critical that we better understand newborn immune responses to vaccination to identify opportunities for modulation that can result in better protection. In particular, the induction of Ab to conserved HA epitopes—including the HA stem—is a highly sought-after goal as it promotes protection against a wide range of IAV strains [36, 37]. Using a newborn NHP model we provide the first evidence that newborns can generate HA-stem–specific IgG Ab as a result of vaccination with inactivated virus. Further, adjuvanting through conjugation of the TLR7/8 agonist R848 can efficiently drive a response to this region. While the immunodominance of the HA head is not eliminated, it appears to be lessened; that is, the stem Ab to total HA Ab ratio is increased. In addition, although not formally demonstrated, our data are consistent with elicitation of a memory response that results in the rapid expansion of stem-specific Abs following viral challenge.

While the IgG response to Ca09 stem was present in only a subset of IPR8-R848 vaccinated newborns following primary vaccination, we found that boosting with IPR8-R848 elicited a response in all but 1 member of the cohort. We note that the interpretation of the response generated following the initial vaccination is limited by the potential that all animals respond, but not always above our detection threshold. Alternatively, it is possible that the increased Ab to stem present following boost represents a discrepancy in epitope specificity between the early plasmablasts generated following the priming dose and reactivated memory cells.

In the early stages of the humoral response, higher-affinity clones appear to adopt extrafollicular plasmablast fates while lower or intermediate affinity clones enter the germinal center [38], potentially leading to a preferential fate decision for head versus stem-specific clones, as has shown to be the case with other influenza epitopes [39]. In adult mice, stem-specific B cell clones exhibit lower starting affinities than their counterparts recognizing head epitopes despite similar precursor frequencies [40]. Our analysis shows lower avidity of stem-specific Ab in challenged animals that received IPR8-R848 vaccination compared to the avidity of the total HA-specific Ab.

Although not directly tested, the increase in stem-specific IgG at day 8 postchallenge in IPR8-R848 vaccinated animals compared to newborns vaccinated without adjuvant and the lack of IgM response to stem in the face of a consistent viral challenge employed across the 3 groups supports the ability of IPR8-R848 vaccination to generate stem-specific memory B cells. The potential of an R848-conjugated inactivated influenza vaccine to increase stem-specific memory cells is promising considering prior data demonstrating low frequencies of clones binding stem epitopes in pools of memory B cells resulting from seasonal vaccination [14, 40, 41]. It is possible that regulatory effects of vaccine-elicited, preexisting Ab may impact the activation/expansion of stem-specific B cells in vaccinated newborns following challenge given the absence of an increased stem-specific response in vaccinated infants at day 14 postchallenge compared to naive infected animals. This is in contrast to what we previously observed for the total influenza-specific IgG response as IPR8-R848 vaccinated infants had higher levels of influenza-specific Ab at day 8 and day 14 following challenge compared to naive and IPR8 plus m229 vaccinated newborns [21].

The improved capacity for neutralization via stem binding in animals given IPR8-R848 despite similar titers across groups suggests that the stem-specific IgG present in these newborns following viral challenge may be more protective than that present in animals vaccinated in the absence of adjuvant. Unexpectedly, this was not associated with increased avidity. It is tempting to speculate that the discrepancy in neutralizing titer and avidity is the result of different Ab footprints or binding conformations that are selected for by vaccination with IPR8-R848 versus the nonadjuvanted vaccine. While most characterized stem-specific mAbs recognize similar regions of the stem and inhibit fusion machinery, there are multiple distinct (if overlapping) binding sites that can permit binding from a variety of Ab structures; precise Ab footprint, rotation, and angle of approach may dictate neutralization efficacy [42].

Further investigation is needed to determine the mechanism by which R848 facilitates the expansion of the stem-specific repertoire as well as the capacity of other adjuvants to produce a similar effect, particularly in a newborn model. In adult animals, addition of adjuvants such as CpG oligodeoxynucleotides have been shown to increase the ability to boost broadly reactive Ab [23]. Adjuvants may facilitate generation of these responses by promoting DC activation, which increases antigen availability in the germinal center and provides cytokines and costimulatory signals that improve B- and T-cell function, all of which are factors implicated in overcoming Ab subdominance [14, 43, 44]. R848 has several potential mechanisms by which it might facilitate expansion of subdominant clones via TLR7/8 signaling, including DC activation, T regulatory cell (Treg) suppression, and direct activation of B cells [45–47]; however, other adjuvants should also be considered as our understanding of immunodominance grows. NHP will be an important model for these studies considering potential differences in human versus murine TLR function and expression on innate immune cells [48]. For example, TLR7 is expressed on most DC and macrophage subsets in mice but is relatively restricted, mainly to plasmacytoid DC, in humans [49, 50].

In summary, our findings demonstrate that newborns can generate an HA stem-specific Ab response following vaccination with inactivated influenza virus. These studies are not possible in human newborns and, as such, this is the first indication that these responses may be generated following vaccination in this age group. Further, adjuvanting an inactivated influenza virus vaccine by direct conjugation of the TLR7/8 agonist R848 facilitates the relative increase in IgG responses to the HA stem following vaccination and subsequent viral challenge compared to the nonadjuvanted vaccine. In addition to an increase in the absolute titer of stem-specific IgG in animals receiving IPR8-R848, the Ab produced has higher neutralizing potential. Future studies are needed to understand the long-term effects of R848-conjugated IAV vaccination on newborns, particularly with regard to the development and maintenance of a long-lived memory response and how this might affect future immune responses to heterologous challenge. Further investigation of the mechanisms by which R848 can drive this response in the challenging situation of the newborn should provide valuable insight into strategies to manipulate the specificity of the Ab response to influenza vaccination.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the Wake Forest Animal Resources Program, Dr Matthew J. Jorgensen, and the veterinary and technical staff of the Vervet Research Colony for care of animals and assistance with animal procedures, especially in regards to the establishment and maintenance of the newborn nursery. We also thank Dr Marlena Westcott for insightful comments and feedback related to the manuscript.

Financial support . This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant number 5R01AI098339 to M. A. A.-M.). The Vervet Research Colony is supported in part by the NIH (grant number P40 OD010965 to M. J. J.). J. W. Y. is supported by Director funds and B. S. G. and M. K. by Vaccine Research Center funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Groothuis JR, Levin MJ, Rabalais GP, Meiklejohn G, Lauer BA. Immunization of high-risk infants younger than 18 months of age with split-product influenza vaccine. Pediatrics 1991; 87:823–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Poehling KA, Edwards KM, Weinberg GA, et al. ; New Vaccine Surveillance Network . The underrecognized burden of influenza in young children. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gostic KM, Ambrose M, Worobey M, Lloyd-Smith JO. Potent protection against H5N1 and H7N9 influenza via childhood hemagglutinin imprinting. Science 2016; 354:722–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gostic KM, Bridge R, Brady S, Viboud C, Worobey M, Lloyd-Smith JO. Childhood immune imprinting to influenza A shapes birth year-specific risk during seasonal H1N1 and H3N2 epidemics. PLoS Pathog 2019; 15:e1008109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brandenburg B, Koudstaal W, Goudsmit J, et al. Mechanisms of hemagglutinin targeted influenza virus neutralization. PLoS One 2013; 8:e80034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DiLillo DJ, Tan GS, Palese P, Ravetch JV. Broadly neutralizing hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies require FcγR interactions for protection against influenza virus in vivo. Nat Med 2014; 20:143–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kirkpatrick E, Qiu X, Wilson PC, Bahl J, Krammer F. The influenza virus hemagglutinin head evolves faster than the Stalk domain. Sci Rep 2018; 8:10432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu Rev Biochem 2000; 69:531–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okuno Y, Isegawa Y, Sasao F, Ueda S. A common neutralizing epitope conserved between the hemagglutinins of influenza A virus H1 and H2 strains. J Virol 1993; 67:2552–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Angeletti D, Gibbs JS, Angel M, et al. Defining B cell immunodominance to viruses. Nat Immunol 2017; 18:456–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sutton TC, Lamirande EW, Bock KW, et al. In vitro neutralization is not predictive of prophylactic efficacy of broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies CR6261 and CR9114 against lethal H2 influenza virus challenge in mice. J Virol 2017; 91:e01603-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yassine HM, McTamney PM, Boyington JC, et al. Use of hemagglutinin stem probes demonstrate prevalence of broadly reactive group 1 influenza antibodies in human sera. Sci Rep 2018; 8:8628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sui J, Hwang WC, Perez S, et al. Structural and functional bases for broad-spectrum neutralization of avian and human influenza A viruses. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2009; 16:265–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tan HX, Jegaskanda S, Juno JA, et al. Subdominance and poor intrinsic immunogenicity limit humoral immunity targeting influenza HA stem. J Clin Invest 2019; 129:850–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu WC, Jan JT, Huang YJ, Chen TH, Wu SC. Unmasking stem-specific neutralizing epitopes by abolishing N-linked glycosylation sites of influenza virus hemagglutinin proteins for vaccine design. J Virol 2016; 90:8496–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kanekiyo M, Joyce MG, Gillespie RA, et al. Mosaic nanoparticle display of diverse influenza virus hemagglutinins elicits broad B cell responses. Nat Immunol 2019; 20:362–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van der Lubbe JEM, Huizingh J, Verspuij JWA, et al. Mini-hemagglutinin vaccination induces cross-reactive antibodies in pre-exposed NHP that protect mice against lethal influenza challenge. NPJ Vaccines 2018; 3:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Valkenburg SA, Mallajosyula VV, Li OT, et al. Stalking influenza by vaccination with pre-fusion headless HA mini-stem. Sci Rep 2016; 6:22666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krammer F, Pica N, Hai R, Margine I, Palese P. Chimeric hemagglutinin influenza virus vaccine constructs elicit broadly protective stalk-specific antibodies. J Virol 2013; 87:6542–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clemens E, Angeletti D, Holbrook BC, et al. Influenza-infected newborn and adult monkeys exhibit a strong primary antibody response to hemagglutinin stem. JCI Insight 2020; 5:135449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Holbrook BC, Kim JR, Blevins LK, et al. A novel R848-conjugated inactivated influenza virus vaccine is efficacious and safe in a neonate nonhuman primate model. J Immunol 2016; 197:555–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holbrook BC, D’Agostino RB Jr, Tyler Aycock S, et al. Adjuvanting an inactivated influenza vaccine with conjugated R848 improves the level of antibody present at 6 months in a nonhuman primate neonate model. Vaccine 2017; 35:6137–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim JH, Davis WG, Sambhara S, Jacob J. Strategies to alleviate original antigenic sin responses to influenza viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012; 109:13751–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ndifon W. A simple mechanistic explanation for original antigenic sin and its alleviation by adjuvants. J R Soc Interface 2015; 12:20150627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khurana S, Chearwae W, Castellino F, et al. Vaccines with MF59 adjuvant expand the antibody repertoire to target protective sites of pandemic avian H5N1 influenza virus. Sci Transl Med 2010; 2:15ra5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khurana S, Verma N, Yewdell JW, et al. MF59 adjuvant enhances diversity and affinity of antibody-mediated immune response to pandemic influenza vaccines. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3:85ra48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Khurana S, Coyle EM, Manischewitz J, et al. ; and the CHI Consortium . AS03-adjuvanted H5N1 vaccine promotes antibody diversity and affinity maturation, NAI titers, cross-clade H5N1 neutralization, but not H1N1 cross-subtype neutralization. NPJ Vaccines 2018; 3:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Honko AN, Mizel SB. Mucosal administration of flagellin induces innate immunity in the mouse lung. Infect Immun 2004; 72:6676–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim JR, Holbrook BC, Hayward SL, et al. Inclusion of flagellin during vaccination against influenza enhances recall responses in nonhuman primate neonates. J Virol 2015; 89:7291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Go JT, Belisle SE, Tchitchek N, et al. 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus elicits similar clinical course but differential host transcriptional response in mouse, macaque, and swine infection models. BMC Genom 2012; 13:627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Matsuoka Y, Suguitan A Jr, Orandle M, et al. African green monkeys recapitulate the clinical experience with replication of live attenuated pandemic influenza virus vaccine candidates. J Virol 2014; 88:8139–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yassine HM, Boyington JC, McTamney PM, et al. Hemagglutinin-stem nanoparticles generate heterosubtypic influenza protection. Nat Med 2015; 21:1065–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ellebedy AH, Krammer F, Li GM, et al. Induction of broadly cross-reactive antibody responses to the influenza HA stem region following H5N1 vaccination in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:13133–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kosik I, Angeletti D, Gibbs JS, et al. Neuraminidase inhibition contributes to influenza A virus neutralization by anti-hemagglutinin stem antibodies. J Exp Med 2019; 216:304–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Klasse PJ. How to assess the binding strength of antibodies elicited by vaccination against HIV and other viruses. Expert Rev Vaccines 2016; 15:295–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Corti D, Suguitan AL Jr, Pinna D, et al. Heterosubtypic neutralizing antibodies are produced by individuals immunized with a seasonal influenza vaccine. J Clin Invest 2010; 120:1663–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sahini L, Tempczyk-Russell A, Agarwal R. Large-scale sequence analysis of hemagglutinin of influenza A virus identifies conserved regions suitable for targeting an anti-viral response. PLoS One 2010; 5:e9268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lam JH, Baumgarth N. The multifaceted B cell response to influenza virus. J Immunol 2019; 202:351–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rothaeusler K, Baumgarth N. B-cell fate decisions following influenza virus infection. Eur J Immunol 2010; 40:366–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Angeletti D, Kosik I, Santos JJS, et al. Outflanking immunodominance to target subdominant broadly neutralizing epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019; 116:13474–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jegaskanda S, Andrews SF, Wheatley AK, Yewdell JW, McDermott AB, Subbarao K. Hemagglutinin head-specific responses dominate over stem-specific responses following prime boost with mismatched vaccines. JCI Insight 2019; 4:e129035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee PS, Wilson IA. Structural characterization of viral epitopes recognized by broadly cross-reactive antibodies. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2015; 386:323–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tesfaye DY, Gudjonsson A, Bogen B, Fossum E. Targeting conventional dendritic cells to fine-tune antibody responses. Front Immunol 2019; 10:1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Woodruff MC, Kim EH, Luo W, Pulendran B. B cell competition for restricted T cell help suppresses rare-epitope responses. Cell Rep 2018; 25:321–7.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Peng G, Guo Z, Kiniwa Y, et al. Toll-like receptor 8-mediated reversal of CD4+ regulatory T cell function. Science 2005; 309:1380–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Levy O, Suter EE, Miller RL, Wessels MR. Unique efficacy of Toll-like receptor 8 agonists in activating human neonatal antigen-presenting cells. Blood 2006; 108:1284–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tomai MA, Miller RL, Lipson KE, Kieper WC, Zarraga IE, Vasilakos JP. Resiquimod and other immune response modifiers as vaccine adjuvants. Expert Rev Vaccines 2007; 6:835–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kugelberg E. Making mice more human the TLR8 way. Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14:6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol 2004; 5:987–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Edwards AD, Diebold SS, Slack EM, et al. Toll-like receptor expression in murine DC subsets: lack of TLR7 expression by CD8 alpha+ DC correlates with unresponsiveness to imidazoquinolines. Eur J Immunol 2003; 33:827–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.