Abstract

Mesoporous silica shells were formed on nonporous spherical silica cores during the sol–gel reaction to elucidate the mechanism for the generation of secondary particles that disturb the efficient growth of mesoporous shells on the cores. Sodium bromide (NaBr) was used as a typical electrolyte for the sol–gel reaction to increase the ionic strength of the reactant solution, which effectively suppressed the generation of secondary particles during the reaction wherein a uniform mesoporous shell was formed on the spherical core. The number of secondary particles (N2nd) generated at an ethanol/water weight ratio of 0.53 was plotted against the Debye–Hückel parameter κ to quantitatively understand the Debye screening effect on secondary particle generation. Parameter κa, where a is the average radius of the secondary particles finally obtained in the silica coating, expresses the trend in N2nd at different concentrations of ammonia and NaBr. N2nd was much lower than that expected theoretically from the variation of secondary particle sizes at a constant Debye–Hückel parameter. A similar correlation with κa was observed at the high and low ethanol/water weight ratios of 0.63 and 0.53, respectively, with different hydrolysis rate constants. The good correlation between N2nd and κa revealed that controlling the ionic strength of the silica coating is an effective approach to suppress the generation of secondary particles for designing mesoporous shells with thicknesses appropriate for their application as high-performance liquid chromatography column packing materials.

Introduction

Monodispersity in particle size distribution is important for extending the practical application scope of particulate functional materials.1−4 The core–shell structure is a type of particle structure in which both monodispersity and functionality of particles are achieved.5−9 In the field of column packing materials for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC),5,6 monodisperse core particles coated with a mesoporous shell have been extensively used to enhance the separation performance in HPLC.

Five-micron-sized core–shell particles with porous shells were reported in the 1960s by Horvath5 and Kirkland.6 In their subsequent research,10 relatively small-sized core–shell particles (average diameter: 2.7 μm) called halo particles were developed. Various core–shell particles in the size range of 2.7–5.0 μm, including halo particles, were fabricated for use as commercial packing materials.10−12 Decreasing the size of particles used for packing materials is an effective approach for improving the contact efficiency of the analyte solution with the packing material.13,14 Core–shell particles smaller than 2 μm were rarely studied until the early 2000s because the usage of downsized core–shell particles required high column pressure for the flow of the analyte solution. Further reduction of the size of core–shell particles to sub-2 μm was also achieved11−13,15−18 because of the recent mechanical progress in the HPLC apparatus.19

The micelle templating method has been widely employed for preparing porous materials since its discovery by Beck et al.20 in 1992. The micelle templating method is also applicable for coating spherical silica particles with mesoporous shells (SiO2@mSiO2).21,22 Our research group23−26 succeeded in synthesizing spherical mesoporous silica particles with and without nonporous cores using the micelle templating method in which a cationic surfactant, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), was used.20,21,27,28 Some other researchers reported an approach to effectively form mesoporous shells on the core particles. The conditions for the synthesis of SiO2@mSiO2, including the concentrations of the silica source24,25,29 and core particles,21,25 were varied to control the thickness of the mesoporous shells. A multistep coating process was also employed to further thicken the mesoporous shell.10,15,21 The oil–water biphase stratification reaction,30−33 layer-by-layer method,11,34,35 partial etching method,36,37 and sonication-assisted synthesis method38 are alternative approaches to control the shell thickness. In the previous reports based on the abovementioned methods, the monodispersity of the core–shell particles was sufficient for their application as column packing materials. However, the thickness of the mesoporous shells formed in the presence of micron-sized nonporous cores was insufficient to meet the dimension requirement for their commercial application as column packing materials because the generation of a large number of secondary particles suppressed efficient shell growth during the formation of mesoporous silica shells.

During the formation of silica-based materials wherein alkoxysilanes were used as silica sources, i.e., through the sol–gel method, the hydrolysis rate in the solution has been regarded as an important factor for tuning the growth rate of the mesoporous silica shell.39−41 The rate of the sol–gel reaction depended on the concentration of [OH–].1,42 Because of the high correlation between the hydrolysis rate and pH of the solution, ammonia (NH3) is commonly employed as a basic catalyst to promote the hydrolysis of alkoxysilanes, including tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS).42

During the initial or middle stage of the formation of porous shells on nonporous silica cores, the surface reaction rate between the cores and the silica moieties in the reactant solution should also be considered to suppress the generation of secondary particles.43,44 This is because secondary particles are generated when the formation rate of silica moieties exceeds the rate at which the silica moieties are consumed during the surface reaction on the cores.28 Moreover, the use of a reactant solution with high ionic strength weakens the electrostatic interaction between the ionized silica moieties and the charged cores, which also promotes the diffusivity of the charged silica moieties to the core surface with the same polarity as the silica moiety to suppress the generation of secondary particles.45,46

Many research groups15,31,38,47 have attempted to thicken mesoporous shells formed on cores through the suppression of secondary particle generation. The addition of an electrolyte is a promising way to thicken the shell; however, the addition of an excessive amount of electrolyte reportedly leads to the inter-core aggregation due to the Debye screening effect.48 Nevertheless, approaches for suppressing secondary particle generation during the sol–gel reaction need further investigation. To this end, in this study, the quantitative relationship between the mesoporous shell thickness and the silica moieties formed by the hydrolysis of TEOS was examined, considering the number of secondary particles generated in the sol–gel reaction to explore the efficient growth of mesoporous silica shells on the cores. We believe that this quantitative analysis of secondary particle generation deepens the understanding of the reaction system for further functionalization of particulate materials. The Debye–Hückel parameter κ of the solution was also calculated to clarify the relationship between the number of secondary particles and diffusivity of the ionized silica moiety toward the cores during the coating process.

Results and Discussion

Ammonia and Electrolyte Concentrations Appropriate for Uniform Silica Coating

Ammonia is commonly used as a basic catalyst in the sol–gel method. The effect of ammonia concentration on particle growth has been studied to primarily examine the kinetic balance between hydrolysis and condensation of TEOS.50 Another advantage of using ammonia is the availability of cationic species (NH4+), which increases the ionic strength of the reactant solution.42,46 In this section, various concentrations of ammonia and electrolytes added to the solution of CTAB were investigated to determine the optimal experimental conditions for the uniform silica coating of the cores. Several concentrations of ammonia and electrolytes were tested to obtain mononuclear core–shell silica particles with an ethanol/water weight ratio of 0.53.

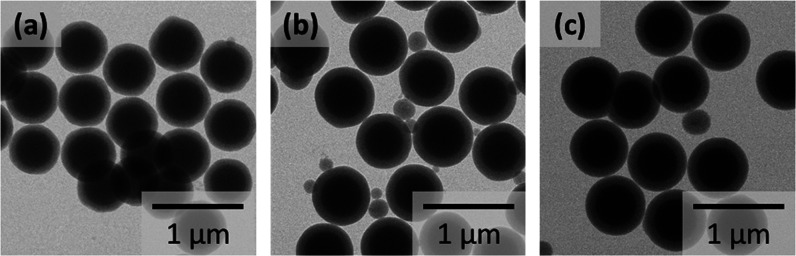

Figure 1 shows the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of SiO2@mSiO2 obtained at different ammonia concentrations and a fixed CTAB concentration of 20 mM. The images were taken for the samples obtained after centrifugation, to clearly observe the silica shell formed on the cores. In the ammonia concentration range of 10–100 mM, a uniform coating of the core with silica shells was observed along with the generation of secondary silica particles. The average diameter and shell thickness of each particle are summarized in Table 1, where the porosities of SiO2@mSiO2 are also listed. The estimation of the secondary particle number from the mass balance of the silicon atoms during shell formation is discussed in the following section.

Figure 1.

TEM images of SiO2@mSiO2 prepared at different NH3 concentrations: 10 mM (a), 50 mM (b), and 100 mM (c). An ethanol/water weight ratio of 0.53. The images were taken for the samples obtained after several centrifugations to clearly observe the silica shell formed on the cores.

Table 1. Characteristics of SiO2@mSiO2 Particles Synthesized at Different NH3 Concentrations Ranging from 10 to 100 mM.

| NH3 conc. [mM] | DV [nm] | TS [nm] | CV [%] | SBET [m2/g]a | VP [cm3/g]b | dP, BJH [nm]c | kh [min–1]d | [Si]soln[mmol/L]e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 596 | 73 | 3.7 | 265 | 0.22 | 2.7 | 0.0178 | 0.21 |

| 50 | 658 | 103 | 3.8 | 416 | 0.37 | 2.7 | 0.0764 | 0.16 |

| 100 | 663 | 106 | 3.5 | 426 | 0.35 | 2.7 | 0.147 | 0.086 |

Calculated by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method.

At p/p0 = 0.990.

Calculated by the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method.

Calculated from the TEOS concentration measured by GC.

Measured by an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS).

Furthermore, the effect of ionic strength on shell formation was investigated by an electrolyte addition experiment, in which sodium bromide (NaBr) was chosen because it offers a typical alkaline metal cation and the anion same as CTAB. Figure 2 shows the TEM images of SiO2@mSiO2 obtained at different concentrations of NaBr in the CTAB solution. The TEM images illustrate that the silica cores were uniformly coated with a silica shell when the NaBr concentration was 0–4 mM at [NH3] = 10 mM. The number of secondary particles formed when the NaBr concentration was ≤4 mM can also be estimated from the Si balance in the sol–gel reaction to correlate the shell thickness with the number of secondary particles in the following section.

Figure 2.

TEM images of SiO2@mSiO2 prepared at different NaBr concentrations: 1 mM (a), 2 mM (b), and 4 mM (c). NH3 concentration was 10 mM and the ethanol/water weight ratio was 0.53. The images were taken for the samples obtained after several centrifugations to clearly observe the silica shell formed on the cores.

Effect of the Debye Screening Effect on the Suppression of Secondary Particle Generation

The discussion about the number of secondary particles generated was preceded by confirming the conversion of TEOS during the sol–gel reaction at [NH3] = 10–100 mM. According to hydrolysis rate constants (kh) listed in Table 1, >99% of TEOS in the concentration range of ammonia was expected to be hydrolyzed within 8 h. The hydrolysis rates in Table 1 suggest that almost all TEOS molecules hydrolyzed in the reaction system were dissolved in the solution and condensed into silica to be precipitated as a shell on the core or generated as secondary particles. Because the amount of silica dissolved in a mixed solvent of alcohol and water is much lower than the number of TEOS molecules present in the reaction system,51,52 we calculated the number of secondary particles from a combination of the average size of secondary particles finally obtained (DV,2nd) and Si concentration in the solution ([Si]soln). Here, the secondary particles were collected from the supernatant of the reaction mixture after one-time centrifugation (see the Supporting Information for details).

The upper part of Table 2 summarizes the values of shell thickness (TS), secondary particle size (DV,2nd), and number of secondary particles (N2nd) generated from the data shown in Figures 1 and 2. Because the highest [Si]soln was measured for the thinnest silica shell of 73 nm, N2nd values at [NH3] = 10 mM and [NaBr] = 0 mM were used for normalizing other N2nd values such as Nmax. As shown in Table 2, the shell formed on the core was thickened upon a decrease in the number of secondary particles generated in the sol–gel reaction. The decrease in N2nd is presented in Figure 3, wherein the Debye–Hückel parameter (κ) is used to evaluate the Debye screening effect on the suppression of secondary particle generation. The decrease in N2nd with increasing κ in Figure 3 suggests that the destabilization caused by the Debye screening effect for ionized silica moieties in the reactant solution could suppress the generation of secondary particles. Interestingly, as shown in Table 2, the size of the secondary particles generated during the formation of a thick silica shell exceeded that during the formation of a thin shell, implying that the presence of ionized silica with high ionic strength facilitates its diffusivity to form large secondary particles. Another interesting point is that the secondary particles were not twice as large as TS, which can be supported by the surface-reaction-limited growth mechanism proposed for the formation of silica particles in the absence of CTAB.43,53

Table 2. Mesoporous Shell Thickness of SiO2@mSiO2 (TS) and the Secondary Particle Size (DV,2nd) and the Number of Secondary Particles (N2nd) Generated.

| NH3 [mM] | NaBr [mM] | ethanol/water weight ratio | TS [nm] | DV,2nd [nm] | N2nd/1019 [L–1]a | N2nd/Nmax |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0 | 0.53 | 73 | 129 | 35.1 | 1 |

| 50 | 0 | 0.53 | 103 | 161 | 13.9 | 0.39 |

| 100 | 0 | 0.53 | 106 | 180 | 5.34 | 0.15 |

| 10 | 1 | 0.53 | 110 | 144 | 23.1 | 0.66 |

| 10 | 2 | 0.53 | 111 | 152 | 6.54 | 0.19 |

| 10 | 4 | 0.53 | 117 | 161 | 4.97 | 0.14 |

| 10 | 0 | 0.63 | 130 | 178 | 5.40 | 0.15 |

| 50 | 0 | 0.63 | 142 | 265 | 0.578 | 0.016 |

| 100 | 0 | 0.63 | 194 | 354 | 0.183 | 0.0052 |

| 10 | 2 | 0.63 | 135 | 205 | 1.46 | 0.042 |

| 10 | 4 | 0.63 | 129 | 234 | 1.64 | 0.047 |

Measured by ICP-MS.

Figure 3.

Relationship between the number of secondary particles (N2nd) and the Debye–Hückel parameter (κ) at an ethanol/water weight ratio of 0.53. Filled circles (●) show N2nd at different NH3 concentrations without any electrolyte addition. Filled squares (■) show N2nd at [NH3] = 10 mM and different NaBr concentrations.

Similar experiments on shell formation were conducted at a higher ethanol/water weight ratio of 0.63 to clarify the relationship between the Debye screening effect and N2nd in the solution, which is presented in the TEM images of Figure 4. The results for TS, DV,2nd, and N2nd at high ethanol/water weight ratios are summarized in the lower part of Table 2. Figure 4c shows the image of the thickest shell of the core–shell particles with the lowest number of secondary particles in this study, whereas Figure 4a depicts the smallest size of the secondary particles generated when the ethanol/water weight ratio is high. The TEM images illustrate that the formation of the thickest silica shell was accompanied by the generation of the largest secondary particles in the silica-coating experiments.

Figure 4.

TEM images of SiO2@mSiO2 prepared at an ethanol/water weight ratio of 0.63. The sol–gel reactions without any electrolyte addition were conducted at different NH3 concentrations: 10 mM (a), 50 mM (b), 100 mM (c). For the addition of electrolyte at the fixed NH3 concentration of 10 mM, the NaBr concentration was set to 2 mM (d) and 4 mM (e). The images were taken for the samples obtained after several centrifugations to clearly observe the silica shell formed on the cores.

To comprehend the effect of the diffusivity of ionized silica on secondary particle generation in all silica-coating experiments, the normalized N2nd values are plotted against κa, which is the Debye–Hückel parameter multiplied by the average secondary particle radius (a (= DV,2nd/2)) in Figure 5. Because it has been reported that the electrical double layer at κa > 10 can be regarded as a layer that is sufficiently thinner than the secondary particle size,54 the overlapping of the electrical double layers of adjacent secondary particles can be neglected in the present silica coatings. Figure 5 clearly shows that the normalized κa can effectively express the generation trend of secondary particles and predict the number of secondary particles generated at different agent concentrations. The red line in Figure 5 shows N2nd expected at a fixed concentration of [Si]soln, which was measured at [NH3] = 10 mM and the low ethanol/water weight ratio without the addition of any electrolyte. It indicates the maximum number of secondary particles completely collected by centrifugation when secondary particles of different sizes were finally obtained. For the experimental N2nd at the different concentrations of ammonia and NaBr, it is noteworthy that the N2nd values almost lie on a single line steeper than the red line.

Figure 5.

Relationship between κa and the relative number of secondary particles. The red solid line shows the theoretical N2nd expected from variation in the secondary particle size (a) at the same κ and [Si]soln. The squares (■, □) show the relative N2nd generated at different concentrations of NaBr. The circles (●, ○) indicate those generated at different concentrations of NH3 without any addition of NaBr. Filled and open symbols represent the relative N2nd formed at the ethanol/water weight ratios of 0.53 and 0.63, respectively.

Because it was reported that the rate of hydrolysis of TEOS is barely changed upon the addition of an electrolyte with several millimolar (mM) concentration,55 the significant decrease in N2nd with the addition of NaBr (Figure 5) must originate predominantly from the Debye screening effect on ionized silica moieties in the coating experiments.

An increase in ammonia concentration without the addition of any electrolyte, which is depicted by circles in Figure 5, not only promotes both hydrolysis and condensation reactions but also weakens the electrostatic interaction in the reactant solution.56 Although the former effect facilitates the generation of secondary particles during the early stage of silica coating, the latter is attributable to the Debye screening effect, which can impact the secondary particle generation promoted by the hydrolysis and condensation reactions, thereby thickening the silica shell formed on the cores. Good correlations of N2nd with κa were observed at the low and high ethanol/water weight ratios, which are indicated by the filled and open symbols in Figure 5, respectively, indicating that the variation of reaction rates by changing the solvent composition is less significant for determining N2nd in the studied silica coating.

The comparison of N2nd generated at different agent concentrations revealed that the control of ionic strength in the silica coating based on the Debye screening effect is an effective approach to suppress the generation of secondary particles for thickening the mesoporous shell, which can facilitate its application as an HPLC column packing material.

Conclusions

The number of secondary particles generated in the sol–gel reaction in the presence of nonporous spherical cores and a cationic surfactant, CTAB, was examined to determine the thickening of the mesoporous shell formed on the cores. At ammonia concentrations of ≥150 mM, uniform mesoporous shells were not formed on the cores because of core aggregation during the reaction. The addition of NaBr of several millimolar concentrations to the reaction system could suppress the generation of secondary particles and cause minimal aggregation of cores, thereby thickening the mesoporous shell formed on the cores. The drastic decrease in N2nd observed at different concentrations of ammonia and NaBr correlated well with κa, which was the Debye–Hückel parameter normalized with the secondary particle radius. The good correlation of N2nd observed at different ethanol/water weight ratios indicated that the generation of secondary particles was predominantly suppressed by the Debye screening effect. These results revealed that the control of the Debye–Hückel parameter can be an effective approach for tuning the thickness of functional shells formed on cores during the sol–gel reaction.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Submicron-sized silica particles (Sciqas series, Sakai Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. (Sakai, Japan)) were used as received as core particles. The average diameter of the silica core particles (Dcore) was 451 nm. The coefficient of variation of diameters (CV), which is commonly used to evaluate the monodispersity of particles, was 4.9%. Sodium bromide (NaBr, 99.9%), tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, 95%), cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, 98%), ammonia aqueous solution (NH3, 25%), and ethanol (99.5%) were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Osaka, Japan). Deionized water (>18.2 MΩ·cm) was prepared by Direct-Q3 UV (Merck KGaA; Darmstadt, Germany).

Mesoporous Shell Coating of Silica Cores

The formation of mesoporous silica shells on core particles was conducted by the micelle templating method using CTAB as a cationic surfactant. A suspension of the core particles in the presence of CTAB was sonicated for 1 h. In the case of electrolyte addition, the electrolyte was added after the sonication. An aqueous solution of NH3 and ethanol was added to the suspension and this mixture was stirred by a magnetic stirrer bar at 35 °C for 30 min. The reaction for shell formation was initiated by TEOS injection, and the mixed suspension was reacted at 35 °C for 18 h. The reaction was carried out in a sealed glass reactor with a total reaction volume of 50 mL. The volume fraction of core particles was 0.40 vol % (the number of core particles: 8.39 × 1016 m–3). The concentrations of CTAB and TEOS were 20 and 60 mM, respectively. After the reaction, silica particles coated with mesoporous shell (SiO2@mSiO2) were separated by centrifugation and were washed twice with water to collect secondary particles. The SiO2@mSiO2 particles separated were dried under reduced pressure at 60 °C overnight. The dried particles were calcined at 550 °C for 4 h to remove the CTAB templates in the particles.

Hydrolysis Rates of TEOS

An aliquot of the reactant suspension was sampled during the reaction to measure the concentration of unreacted TEOS with a gas chromatograph (GC: GC-4000 Plus, GL Science (Tokyo, Japan)). The hydrolysis rate constant of TEOS, kh, was estimated assuming a first-order reaction of the TEOS concentration.

Evaluation of Electrostatic Interparticle Interactions Based on the Debye–Hückel Parameter

The Debye–Hückel parameter was calculated as eq 1, where ε is the relative dielectric constant of the solvent, ε0 is the dielectric constant of the vacuum, and kb, T, and e are Boltzmann’s constant, reaction temperature, and elementary charge, respectively. The ionic strength (I) in eq 1 was calculated based on the measured pH at the time of 50% TEOS conversion (see Figure S1). The other parameters used for the calculation of I are shown in Tables S1 and S2.

| 1 |

Thickness of the Mesoporous Shell

SiO2@mSiO2 synthesized in the present work was observed with FE-STEM (Hitachi, HD-2700). The diameter (Dcore–shell) and monodispersity (CV) of SiO2@mSiO2 were determined by directly measuring particles in the TEM images (200 particles or more). The shell thickness TS was calculated by the following equation:

| 2 |

Number of Secondary Particles

The number of secondary particles (N2nd) was calculated in eq 3 with the average size of secondary particles (DV,2nd) and the Si atomic concentration ([Si]soln) measured by an inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometer (ICP-MS, Agilent-8800 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA)). The [Si]soln in eq 3 is the total concentration of silicon, including secondary silica particles and other silica moieties in the supernatant, that was obtained by centrifuging the resultant suspension.

| 3 |

where M is the molecular weight of silica (= 60.08 g/mol), ρ is the density of silica, and V is the reaction volume (50 mL). A density of 1.9 g/cm3 was used as a typical value for silica formed in sol–gel reactions43,49 because the exact density of secondary particles is unknown in this study. The average diameter of secondary particles (DV,2nd) was obtained from TEM images.

To examine the porosity of SiO2@mSiO2, N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms were measured with BELSORP-mini II (Bel Japan Inc.) at 77 K. Their pore size distributions were calculated by Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method. The surface areas and the total pore volumes of SiO2@mSiO2 were determined using the adsorption isotherms with Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis from the adsorbed amounts of nitrogen at a relative pressure (p/p0) of 0.99.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the technical support staff in the department of Engineering, Tohoku University, for STEM observation and ICP-MS measurements.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c02293.

Variations of pH in the reaction mixtures of SiO2@mSiO2 synthesis at different NH3 concentrations (Figure S1); equations for calculation of ionic strength, parameters used for the calculation, and solvent properties at different ethanol/water weight ratios (Tables S1 and S2); and the detailed procedure of evaluation of secondary particles generated in the silica-coating process by ICP-MS (PDF)

This research was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 16J03375, 17H02744, and 20K21097 and Materials Processing Science project (“Materealize”) of MEXT, Grant Number JPMXP0219192801).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Harris M. T.; Brunson R. R.; Byers C. H. The Base-Catalyzed Hydrolysis and Condensation Reactions of Dilute and Concentrated TEOS Solutions. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1990, 121, 397–403. 10.1016/0022-3093(90)90165-i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto E.; Mori S.; Shimojima A.; Wada H.; Kuroda K. Fabrication of Colloidal Crystals Composed of Pore-Expanded Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Prepared by a Controlled Growth Method. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 2464–2470. 10.1039/C6NR07416B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto E.; Kitahara M.; Tsumura T.; Kuroda K. Preparation of Size-Controlled Monodisperse Colloidal Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles and Fabrication of Colloidal Crystals. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 2927–2933. 10.1021/cm500619p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yahata A.; Ishii H.; Nakamura K.; Watanabe K.; Nagao D. Three-Dimensional Periodic Structures of Gold Nanoclusters in the Interstices of Sub-100 nm Polymer Particles toward Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Adv. Powder Technol. 2019, 30, 2957–2963. 10.1016/j.apt.2019.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath C. G.; Preiss B. A.; Lipsky S. R. Fast Liquid Chromatography: An Investigation of Operating Parameters and the Separation of Nucleotides on Pellicular Ion Exchangers. Anal. Chem. 1967, 39, 1422–1428. 10.1021/ac60256a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland J. J. Controlled Surface Porosity Supports for High-Speed Gas and Liquid Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 1969, 41, 218–220. 10.1021/ac60270a054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohama N.; Suwabe C.; Ishii H.; Hayashi K.; Nagao D. Characterization on Magnetophoretic Velocity of the Cluster of Submicron-Sized Composite Particles Applicable to Magnetic Separation and Purification. Colloids Surf., A 2019, 568, 141–146. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2019.02.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao K. L. A.; Arif A. F.; Kamikubo K.; Izawa T.; Iwasaki H.; Ogi T. Controllable Synthesis of Carbon-Coated SiOx Particles through a Simultaneous Reaction between the Hydrolysis–Condensation of Tetramethyl Orthosilicate and the Polymerization of 3-Aminophenol. Langmuir 2019, 35, 13681–13692. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b02599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui H.; Gao Z.; Guo J.; Wang Y.; Yuan J.; Hao J.; Dong S.; Cui J. Dual PH-Responsive Polymer Nanogels with a Core–Shell Structure for Improved Cell Association. Langmuir 2019, 35, 16869–16875. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b03107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeStefano J. J.; Langlois T. J.; Kirkland J. J. Characteristics of Superficially-Porous Silica Particles for Fast HPLC: Some Performance Comparisons with Sub-2-μm Particles. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2008, 46, 254–260. 10.1093/chromsci/46.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes R.; Ahmed A.; Edge T.; Zhang H. Core–Shell Particles: Preparation, Fundamentals and Applications in High Performance Liquid Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1357, 36–52. 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langsi V. K.; Ashu-Arrah B. A.; Glennon J. D. Sub-2-μm Seeded Growth Mesoporous Thin Shell Particles for High-Performance Liquid Chromatography: Synthesis, Functionalisation and Characterisation. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1402, 17–26. 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete S.; Guillarme D. Kinetic Evaluation of New Generation of Column Packed with 1.3μm Core-Shell Particles. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1308, 104–113. 10.1016/j.chroma.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M.; Eon C.; Guiochon G. Study of the Pertinency of Pressure in Liquid Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1974, 99, 357–376. 10.1016/S0021-9673(00)90870-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Omamogho J. O.; Hanrahan J. P.; Tobin J.; Glennon J. D. Structural Variation of Solid Core and Thickness of Porous Shell of 1.7μm Core–Shell Silica Particles on Chromatographic Performance: Narrow Bore Columns. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 1942–1953. 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Q.; Si Y.; Xuan H.; Zhang K.; Chen X.; Ding Y.; Feng S.; Yu H.-Q.; Abdullah M. A.; Alamry K. A. Dendritic Core-Shell Silica Spheres with Large Pore Size for Separation of Biomolecules. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1540, 31–37. 10.1016/j.chroma.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu R.; Zhang W.; Liu N.; Zhang Q.; Liu Y.; Li X.; Wei Y.; Feng L. Antioil Ag3PO4 Nanoparticle/Polydopamine/Al2O3 Sandwich Structure for Complex Wastewater Treatment: Dynamic Catalysis under Natural Light. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 8019–8028. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b01469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Aller M.; Gurny R.; Veuthey J.-L.; Guillarme D. Coupling Ultra High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography with Mass Spectrometry: Constraints and Possible Applications. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1292, 2–18. 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.-L.; Dong P.; Yang G.-H. The Size Dependence of Growth Rate of Monodisperse Silica Particles from Tetraalkoxysilane. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 189, 268–272. 10.1006/jcis.1997.4809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck J. S.; Schmitt K. D.; Higgins J. B.; Schlenkert J. L.; Vartuli J. C.; Roth W. J.; Leonowicz M. E.; Kresge C. T.; Chu C. T. W.; Olson D. H.; et al. A New Family of Mesoporous Molecular Sieves Prepared with Liquid Crystal Templates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 10834–10843. 10.1021/ja00053a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. Core/Shell Structured Silica Spheres with Controllable Thickness of Mesoporous Shell and Its Adsorption, Drug Storage and Release Properties. Colloids Surf., A 2013, 428, 79–85. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2013.03.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.; Wan G.; Ma S.; Xia H.; Wang J.; Liu J.; Liu Y.; Chen G.; Bai Q. Synthesis and Optimization of SiO2@SiO2 Core-Shell Microspheres by an Improved Polymerization-Induced Colloid Aggregation Method for Fast Separation of Small Solutes and Proteins. Talanta 2020, 207, 120310 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.120310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii H.; Kawai S.; Nagao D.; Konno M. Synthesis of Phosphor-Free Luminescent, Monodisperse, Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles in the Co-Presence of Double- and Single-Chain Cationic Surfactants. Adv. Powder Technol. 2016, 27, 448–453. 10.1016/j.apt.2016.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii H.; Kawai S.; Nagao D.; Konno M. Phosphor-Free Silica-Coating of Monodisperse Cores for Dual Functionalization with Luminescent and Mesoporous Shell. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 241, 366–371. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2016.12.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii H.; Nara M.; Hashimoto Y.; Kanno A.; Ishikawa S.; Nagao D.; Konno M. Uniform Formation of Mesoporous Silica Shell on Micron-Sized Cores in the Presence of Hydrocarbon Used as a Swelling Agent. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2018, 85, 539–545. 10.1007/s10971-018-4589-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto K.; Watanabe K.; Ishikawa S.; Ishii H.; Suga K.; Nagao D. Pore Expanding Effect of Hydrophobic Agent on 100 nm-Sized Mesoporous Silica Particles Estimated Based on Hansen Solubility Parameters. Colloids Surf., A 2021, 609, 125647 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto E.; Kuroda K. Colloidal Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2016, 89, 501–539. 10.1246/bcsj.20150420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H.; Urata C.; Yamamoto E.; Higashitamori S.; Yamauchi Y.; Kuroda K. Effective Use of Alkoxysilanes with Different Hydrolysis Rates for Particle Size Control of Aqueous Colloidal Mesostructured and Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles by the Seed-Growth Method. ChemNanoMat 2015, 1, 194–202. 10.1002/cnma.201500010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ran Z.; Sun Y.; Chang B.; Ren Q.; Yang W. Silica Composite Nanoparticles Containing Fluorescent Solid Core and Mesoporous Shell with Different Thickness as Drug Carrier. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 410, 94–101. 10.1016/j.jcis.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen D.; Yang J.; Li X.; Zhou L.; Zhang R.; Li W.; Chen L.; Wang R.; Zhang F.; Zhao D. Biphase Stratification Approach to Three-Dimensional Dendritic Biodegradable Mesoporous Silica Nanospheres. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 923–932. 10.1021/nl404316v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Q.; Min Y.; Zhang L.; Xu Q.; Yin Y. Silica Microspheres with Fibrous Shells: Synthesis and Application in HPLC. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 9631–9638. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b02511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Q.; Li W.; Wu Q. Formation Mechanism of Silica Particles with Dendritic Structure. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 6656–6661. 10.1002/slct.201900952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Q.; Li W.; Wu Q.; Chen X.; Wang F.; Asiri A. M.; Alamry K. A. The Formation Mechanism of the Micelle-Templated Mesoporous Silica Particles: Linear Increase or Stepwise Growth. Colloids Surf., A 2019, 577, 62–66. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2019.05.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tong W.; Song X.; Gao C. Layer-by-Layer Assembly of Microcapsules and Their Biomedical Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 6103–6124. 10.1039/c2cs35088b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H.; Brennan J. D. Rapid Fabrication of Core–Shell Silica Particles Using a Multilayer-by-Multilayer Approach. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 1207–1209. 10.1039/C0CC04221H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.; Zhang T.; Ge J.; Yin Y. Permeable Silica Shell through Surface-Protected Etching. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 2867–2871. 10.1021/nl8016187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Zhang Q.; Goebl J.; Zhang T.; Yin Y. Control over the Permeation of Silica Nanoshells by Surface-Protected Etching with Water. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 11836–11842. 10.1039/c0cp00031k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L.; Cai J.; Ke Y. Ultrasonic-Assisted Sol–Gel Synthesis of Core–Shell Silica Particles for High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 859–868. 10.1007/s10904-019-01239-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H.; Urata C.; Ujiie H.; Yamauchi Y.; Kuroda K. Preparation of Aqueous Colloidal Mesostructured and Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles with Controlled Particle Size in a Very Wide Range from 20 nm to 700 nm. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 6145–6153. 10.1039/c3nr00334e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H.; Ujiie H.; Urata C.; Yamamoto E.; Yamauchi Y.; Kuroda K. A Multifunctional Role of Trialkylbenzenes for the Preparation of Aqueous Colloidal Mesostructured/Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles with Controlled Pore Size, Particle Diameter, and Morphology. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 19557–19567. 10.1039/C5NR04465K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. W.; Jang H.-G.; Sim H.-I.; Shin C.-H.; Kim J.-H.; Seo G. Preparation of Dandelion-Type Silica Spheres and Their Application as Catalyst Supports. J. Porous Mater. 2014, 21, 797–809. 10.1007/s10934-014-9828-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao D.; Osuzu H.; Yamada A.; Mine E.; Kobayashi Y.; Konno M. Particle Formation in the Hydrolysis of Tetraethyl Orthosilicate in PH Buffer Solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 279, 143–149. 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao D.; Satoh T.; Konno M. A Generalized Model for Describing Particle Formation in the Synthesis of Monodisperse Oxide Particles Based on the Hydrolysis and Condensation of Tetraethyl Orthosilicate. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2000, 232, 102–110. 10.1006/jcis.2000.7195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao D.; Mine E.; Kobayashi Y.; Konno M. Synthesis of Silica Particles in the Hydrolysis of Tetraethyl Orthosilicate with Amine Catalysts. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 2004, 37, 905–907. 10.1252/jcej.37.905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.-L.; Dong P.; Yang G.-H.; Yang J.-J. Characteristic Aspects of Formation of New Particles during the Growth of Monosize Silica Seeds. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1996, 180, 237–241. 10.1006/jcis.1996.0295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao D.; Mine E.; Katakura T.; Konno M. Influence of Ammonia Concentration on Particle Size Distributions in Seeded Reaction of Hydrolysis and Condensation of Tetraethyl Orthosilicate. Kagaku Kogaku Ronbunshu 2003, 29, 546–550. 10.1252/kakoronbunshu.29.546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Zhen Z.; Tang W.; Todd T.; Chuang Y. J.; Wang L.; Pan Z.; Xie J. Label-Free Luminescent Mesoporous Silica Nanoparti-Cles for Imaging and Drug Delivery. Theranostics 2013, 3, 650–657. 10.7150/thno.6668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. H.; Beyer F. L.; Furst E. M. Synthesis of Monodisperse Fluorescent Core-Shell Silica Particles Using a Modified Stöber Method for Imaging Individual Particles in Dense Colloidal Suspensions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 288, 114–123. 10.1016/j.jcis.2005.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimoto S.; Dick W. D.; Hunt B.; Szymanski W. W.; McMurry P. H.; Roberts D. L.; Pui D. Y. H. Characterization of Nanosized Silica Size Standards. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 936–945. 10.1080/02786826.2017.1335388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y.; Lu Z.; Teng Z.; Liang J.; Guo Z.; Wang D.; Han M.-Y.; Yang W. Unraveling the Growth Mechanism of Silica Particles in the Stöber Method: In Situ Seeded Growth Model. Langmuir 2017, 33, 5879–5890. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b01140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buining P. A.; Liz-Marzán L. M.; Philipse A. P. A Simple Preparation of Small, Smooth Silica Spheres in a Seed Alcosol for Stöber Synthesis. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1996, 179, 318–321. 10.1006/jcis.1996.0220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iler R. K.The Chemistry of Silica, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Van Blaaderen A.; Van Geest J.; Vrij A. Monodisperse Colloidal Silica Spheres from Tetraalkoxysilanes: Particle Formation and Growth Mechanism. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1992, 154, 481–501. 10.1016/0021-9797(92)90163-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshima H. Primary Electroviscous Effect in a Moderately Concentrated Suspension of Charged Spherical Colloidal Particles. Langmuir 2007, 23, 12061–12066. 10.1021/la701768a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao D.; Kon Y.; Satoh T.; Konno M. Electrostatic Interactions in Formation of Particles from Tetraethyl Orthosilicate. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 2000, 33, 468–473. 10.1252/jcej.33.468. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakabayashi H.; Yamada A.; Noba M.; Kobayashi Y.; Konno M.; Nagao D. Electrolyte-Added One-Pot Synthesis for Producing Monodisperse, Micrometer-Sized Silica Particles up to 7 μm. Langmuir 2010, 26, 7512–7515. 10.1021/la904316f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.