Abstract

Bismuth (III) oxide nanoparticles (Bi2O3 NPs) have shown great potential for biomedical applications because of their tunable physicochemical properties. In this work, pure and Zn-doped (1 and 3 mol %) Bi2O3 NPs were synthesized by a facile chemical route and their cytotoxicity was examined in cancer cells and normal cells. The X-ray diffraction results show that the tetragonal phase of β-Bi2O3 remains unchanged after Zn-doping. Transmission electron microscopy and scanning electron microscopy images depicted that prepared particles were spherical with smooth surfaces and the homogeneous distribution of Zn in Bi2O3 with high-quality lattice fringes without distortion. Photoluminescence spectra revealed that intensity of Bi2O3 NPs decreases with increasing level of Zn-doping. Biological data showed that Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs induce higher cytotoxicity to human lung (A549) and liver (HepG2) cancer cells as compared to pure Bi2O3 NPs, and cytotoxic intensity increases with increasing concentration of Zn-doping. Mechanistic data indicated that Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs induce cytotoxicity in both types of cancer cells through the generation of reactive oxygen species and caspase-3 activation. On the other hand, biocompatibility of Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs in normal cells (primary rat hepatocytes) was greater than that of pure Bi2O3 NPs and biocompatibility improves with increasing level of Zn-doping. Altogether, this is the first report highlighting the role of Zn-doping in the anticancer activity of Bi2O3 NPs. This study warrants further research on the antitumor activity of Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs in suitable in vivo models.

1. Introduction

Bismuth (Bi) is known as one of the least toxic heavy metals for the human body and it has a long history in medicine due to its antibacterial activity.1 Several bismuth-based medical formulations such as ranitidine bismuth citrate and bismuth subsalicylate are utilized for the treatment of gastrointestinal problems.2 Moreover, organic-based bismuth compounds have antitumor effects.3,4 Although organic-based bismuth complexes have potential anticancer activity, they can exert adverse health effects to humans.5,6

Currently, bismuth (III) oxide nanoparticles (Bi2O3 NPs) have received great attention for their applications in chemical, electrical, optical, engineering, and biomedicine due to their excellent physicochemical properties including high stability, high surface area, desirable catalytic activity, low toxicity, and cost-effectiveness.7 The ease of controlling the physicochemical properties of Bi2O3 NPs during synthesis can open new opportunities for its application in medicine.8 A recent study suggested that Bi2O3 NPs can be used as a radiosensitizer in cancer radiotherapy.9 Some studies also observed that Bi2O3 NPs exert toxicity to cancer cells by intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation.10,11

A higher intracellular level of ROS is associated with induction of apoptosis, and cancer cells can be killed by ROS-generating agents.12−14 A low-to-moderate level of ROS is essential for cellular function and survival. However, excessive ROS production can lead to oxidative DNA damage, lipid peroxidation, and apoptosis.15,16 Comparatively, the elevated level of ROS is found in cancer cells than those of their normal counterparts providing a promising strategy to target cancer cells selectively. For example, ZnO NPs and heterocyclic organobismuth (III) kill cancer cells selectively through the ROS pathway.4,17

Research on anticancer potential of Bi2O3 NPs is still in the infancy stage because of their significant side effects.18 Hence, there is a need to prepare Bi2O3 NPs with improved anticancer activity and excellent biocompatibility. Keeping this point in mind, we synthesized pure and Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs with higher toxicity in cancer cells and better biocompatibility to normal cells. Pure and Zn-doped (1 and 3 mol %) Bi2O3 NPs were prepared by a facile chemical method. Synthesized pure Bi2O3 NPs and Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), field emission transmission electron microscopy (FETEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), photoluminescence (PL), and dynamic light scattering (DLS). Anticancer efficacy of pure and Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs was studied in two different cancer cell lines: human lung cancer (A549) and liver cancer (HepG2) cells. Biocompatibility of prepared NPs was examined in primary rat hepatocytes. The possible mechanism of antitumor activity of prepared NPs was explored through ROS generation and caspase-3 (apoptotic marker) activation.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. XRD Analysis

XRD spectra of pure and Zn-doped (1 and 3%) Bi2O3 are presented in Figure 1. The major peaks of all the NPs at 2θ values of 25.96, 28.19, 30.52, 32.02, 32.95, 41.52, 46.50, 47.12, 51.48, 54.46, 55.73, and 57.96 corresponded to the diffractions of the (210), (201), (211), (002), (220), (212), (222), (400), (123), (203), (421), and (402) planes of the tetragonal structure of β-Bi2O3 (JCPDS no. 27-0050). The absence of Zn peaks in Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs could be due to a small amount of Zn2+ concentration (1 and 3%) as well as the smaller ionic radius of Zn2+ ions (0.074 nm) as compared to Bi3+ ions (0.117 nm).

Figure 1.

XRD spectra of pure and Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs.

The crystallite size of prepared samples was determined for the (201) diffraction of Bi2O3 using the Scherrer equation.19 The crystallite size of pure Bi2O3, 1% Zn–Bi2O3, and 3% Zn–Bi2O3 particles was 67, 63, and 54 nm, respectively (Table 1). The reduction in size upon Zn-doping was because of the smaller ionic radius of Zn2+ (0.074 nm) than those of Bi3+ (0.117 nm). Reduction in particle size of Bi2O3 after Zn-doping was also reported by other investigators.20,21

Table 1. Physicochemical Characterization of Pure and Zn-Doped Bi2O3 NPs.

| parameters | Bi2O3 | 1% Zn–Bi2O3 | 3% Zn–Bi2O3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| XRD size (nm) | 67 | 63 | 54 |

| TEM size (nm) | 71 | 64 | 51 |

| SEM size (nm) | 70 | 63 | 52 |

| hydrodynamic size (nm)a | |||

| deionized water | 247 ± 23 | 215 ± 13 | 188 ± 15 |

| culture media | 211 ± 17 | 197 ± 18 | 167 ± 11 |

| zeta potential (mV)a | |||

| deionized water | 15 ± 4 | 19 ± 5 | 25 ± 4 |

| culture medium | 18 ± 3 | 22 ± 6 | 27 ± 3 |

Data presented mean ± SD of triplicates (n = 3).

2.2. TEM Study

Microstructure, morphology, and particle size of prepared samples were characterized by FETEM. Figure 2A,B depicts the representative transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of pure and 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs, respectively. These TEM images display that prepared NPs possess spherical morphology with some degrees of agglomeration. The shape of Bi2O3 NPs remains the same but particle size decreases after Zn-doping (71–51 nm) (Table 1), which is in agreement with size estimated from the Scherrer equation. The tetragonal structure of Bi2O3 NPs is further confirmed by the visible lattice fringes in the high-resolution TEM images (Figure 2C,D). These images demonstrate the presence of both Bi2O3 and Zn with high-quality lattice fringes without distortion. The interplanar spacing of the lattice of Bi2O3 NPs and 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs is 0.325 nm and 0.321 nm, respectively, which relates to the (201) plane of the tetragonal phase of Bi2O3, whereas the lattice fringe of Zn has an interplanar spacing of 0.233 nm which corresponds to the (101) plane of the cubic Zn crystallographic structure. TEM machine-generated EDS spectra of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs showed the presence Bi, Zn, and O peaks without a contamination peak (Figure 3). The presence of Cu and C peaks was due to the use of carbon-coated copper TEM grid.

Figure 2.

TEM characterization. (A) Low-resolution TEM image of pure Bi2O3. (B) Low-resolution TEM image of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs. (C) High-resolution TEM image of pure Bi2O3. (D) High-resolution TEM image of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs.

Figure 3.

Elemental composition of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs by EDS.

2.3. SEM Study

Morphology, elemental composition, and elemental mapping of pure and Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs were further observed by FESEM. Figure 4A–C represents the typical scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of pure Bi2O3, 1% Zn–Bi2O3, and 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs, respectively. In agreement with TEM, these images also suggested spherical morphology, and particle size of Bi2O3 was found to be gradually decreased with the increase in Zn-doping (71–51 nm) (Table 1). The smaller particle size of semiconductor NPs after metal ion-doping would give rise to a higher surface area, which is generally beneficial for increased cytotoxicity to cancer cells.19,22 SEM machine-generated EDS spectra of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs showed the stoichiometric presence Bi (87.46%), O (9.67%), and Zn (2.91%) (Figure 4D). The SEM elemental mapping of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs further confirmed the uniform distribution of Zn in Bi2O3 (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

SEM characterization. (A–C) SEM images of pure Bi2O3, 1% Zn–Bi2O3, and 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs, respectively. (D) EDS spectra of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs.

Figure 5.

SEM elemental mapping of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs. (A) SEM image and (B) bismuth, (C) oxygen, and (D) zinc mapping.

2.4. PL Study

The room-temperature PL spectra of pure and Zn-doped (1 and 3%) Bi2O3 NPs with a 330 nm as an excitation wavelength are given in Figure 6. The visible emission peaks at 431, 451, and 472 nm are observed for all the prepared NPs. However, intensity of Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs decreases with increasing Zn concentrations. Lower intensity of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs suggested the effective migration of charge carriers (electron and holes) from the inner part of NPs to the surface so that they can participate in surface redox reactions.21,23 These phenomena are useful in photocatalysis and biomedicine.12,24

Figure 6.

Photoluminescence spectra of pure and Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs.

2.5. DLS Study

It is crucial to explore the aqueous behavior of prepared NPs before their cytotoxicity investigations. In this study, hydrodynamic size and zeta potential of pure Bi2O3, 1% Zn–Bi2O3, and 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs were measured in deionized water and complete culture medium (DMEM + 10% FBS). Results showed that the hydrodynamic size of pure and Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs in deionized water and culture medium was 3–5 times higher than the primary size of nanopowder calculated from XRD and TEM (Table 1). Higher hydrodynamic size could be due to the tendency of NPs to agglomerate in an aqueous suspension. Such a phenomenon was also reported by other investigators.11,25,26 The zeta potential results demonstrated that the particle surface charge of pure and Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs was ranging from 15 to 25 mV in deionized water and 18–27 in culture medium. These values suggested that prepared NPs were fairly stable in an aqueous suspension. Generally, the zeta potential value of NPs around 30 mV (positive or negative) showed excellent colloidal stability.17,27 The positive surface charge of NPs under the physiological condition as reported in the present study provides an encouraging environment for their interaction with cancer cells as they hold negative surface charges.17

2.6. Cytotoxicity Study

Recent studies highlight the importance of metal-based NPs in biomedical applications including antimicrobial and anticancer activity.28−30 Moreover, metal ion-doping can further improve the biomedical application of metal oxide NPs through the tailoring of properties.22,31 For example, Miri et al. observed that the increase in Ni-doping for Ce2O NPs increased the cytotoxicity in colon cancer cells (HT-29).32 Our previous study also showed that Ag-doping increases the cytotoxicity of TiO2 NPs in cancer cells and improves their biocompatibility in normal cells.19

In the present study, cytotoxicity of pure Bi2O3, 1% Zn–Bi2O3, and 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs was examined in two types of cancer cells (human lung cancer A549 and human liver cancer HepG2) along with the noncancerous normal cells (primary rat hepatocytes). Cells were exposed for 24 h to different concentrations (0–400 μg/mL) of pure and Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs and cytotoxicity was examined by MTT assay. Figure 7A,B shows that all three NPs (Bi2O3, 1% Zn–Bi2O3, and 3% Zn–Bi2O3) induced dose-dependent cytotoxicity in both types of cancer cells (A549 and HepG2). Moreover, Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs induce higher cytotoxicity in comparison with pure Bi2O3 NPs, and cytotoxicity increased with increasing concentration of Zn-doping. IC50’s of A549 cells for pure Bi2O3, 1% Zn–Bi2O3, and 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs were 205, 110, and 63 μg/mL, respectively. Besides, IC50’s of HepG2 cells for pure Bi2O3, 1% Zn–Bi2O3, and 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs were 223, 120, and 73 μg/mL, respectively (Table 2).

Figure 7.

Cytotoxicity of pure and Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs in human lung A549 (A) and liver HepG2 (B) cancer cells. *p < 0.05 vs control.

Table 2. IC50’s (μg/mL) for Different Cells against Pure and Zn-Doped Bi2O3 NPs.

| IC50s for cells (μg/mL) | Bi2O3 | 1% Zn–Bi2O3 | 3% Zn–Bi2O3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| A549 cells | 205 | 110 | 63 |

| HepG2 cells | 223 | 120 | 73 |

| primary rat hepatocytes | 533 | 1136 | 2303 |

The anticancer activity of bismuth-based NPs was also reported by other investigators. For example, a recent study observed that bismuth lipophilic (BisBAL) NPs exhibit significant cytotoxicity to breast cancer MCF-7 cells and relatively low toxicity to noncancerous MCF-10A cells.33 Ouyang and co-workers also found that compared to cisplatin, bismuth-based complex (BiL2Cl3) showed better anticancer activity against tumor cells and lower toxicity to normal cells.34

The Bi is considered as one of the least toxic and biologically less-reactive heavy metals, which is more appropriate for biomedical applications in comparison with other metals such as silver.7 Hence, cytotoxicity of pure and Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs was further examined in noncancerous primary rat hepatocytes. Figure 8 demonstrates that all three prepared NPs did not exert much toxicity to primary rat hepatocytes. Moreover, Zn-doping further improves the biocompatibility of Bi2O3 NPs in primary rat hepatocytes. The IC50’s of primary rat hepatocytes for pure Bi2O3, 1% Zn–Bi2O3, and 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs were 533, 1136, and 2303 μg/mL, respectively. These results suggested that Bi2O3 NPs selectively induced cytotoxicity in cancer cells while not affecting the normal cells. Moreover, Zn-doping increases the cytotoxicity of Bi2O3 NPs in cancer cells and improves their biocompatibility in normal cells. High toxicity of Bi(OH)3 and Bi2O3 NPs in gliosarcoma 9L cells and human breast cancer MCF-7 cells and low toxicity in normal cells were also reported by Bogusz et al.35

Figure 8.

Cytotoxicity of pure and Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs in primary rat hepatocytes. *p < 0.05 vs control.

2.7. Possible Mechanisms of Anticancer Activity of Zn-Doped Bi2O3 Nanoparticles

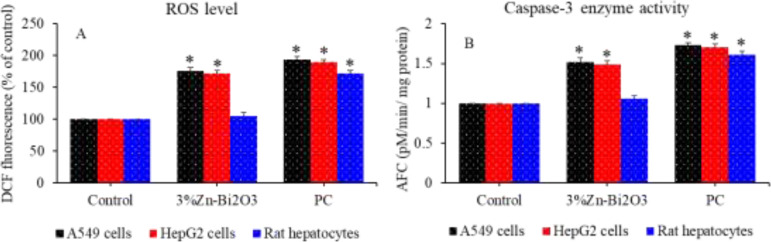

Earlier studies have shown that ZnO NPs have inherent potential of killing cancer cells through ROS while sparing the normal cells.17,36 Some previous reports also demonstrated that Bi-based nanoscale materials selectively induce cytotoxicity to cancer cells via ROS without much affecting the normal cells.33,35 ROS-induced oxidative stress has been also suggested as one of the potential mechanisms of selective cytotoxicity of cancer cells by other semiconductor NPs.37,38 Hence, we further explored the potential mechanisms of anticancer activity and biocompatibility of Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs. Intracellular generation of ROS in cancer cells (A459 and HepG2) and primary rat hepatocytes following exposure to moderate concentration of (50 μg/mL) of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs for 24 h was examined. Figure 9A shows that 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs significantly induce ROS generation in both types of cancer (A549 and HepG2) cells. Interestingly, 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs did not generate ROS in primary rat hepatocytes.

Figure 9.

ROS level (A) and caspase-3 enzyme activity (B) in A549 cells, HepG2 cells, and primary rat hepatocytes following exposure to 50 μg/mL of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs for 24 h. The H2O2 was used as the positive control (PC). *p < 0.05 vs control.

Intracellular ROS generation seems the potential mechanisms of anticancer activity of Zn–Bi2O3 NPs. Zn-doping brings two important changes in the physicochemical properties of Bi2O3 NPs, which plays an important role in the anticancer activity of Zn–Bi2O3 NPs. First, Zn-doping decreases the particle size of Bi2O3 NPs. The ROS-generating potential of NPs increases with decreasing particle size.39 Second, PL study indicated that the intensity of PL spectra of Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs decreases with increasing Zn2+ ion concentration. Lower intensity of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs suggested the effective migration of charge carriers (electron and holes) from the inner part of NPs to the surface so that they can participate in surface redox reactions. This is a favorable condition for intracellular generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which is useful for various applications including photocatalysis, antibacterial activity, and anticancer activity. In the present study, in vitro results demonstrated that Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs exert higher cytotoxicity to cancer cells than those of pure Bi2O3 NPs and cytotoxicity increased with increasing doping concentration of Zn2+ ions.

There are increasing evidences that NPs induced apoptosis in cancer cells through the activation of caspases.40 Caspase-3 gene is a type of proteases that are found in mitochondrial and actively involved in the apoptosis. Caspase-3 enzyme activity of cancer cells (A459 and HepG2) and primary rat hepatocytes was assessed following exposure to 50 μg/mL of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs for 24 h. Figure 9B demonstrates that 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs significantly activate caspase-3 enzyme in both cancer cells. Interestingly, 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs did not affect the activity of caspase-3 enzyme in primary rat hepatocytes. Altogether, Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs exerted cytotoxicity in cancer cells via ROS generation and caspase-3 activation. Potential mechanisms of selective cytotoxicity of Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs in cancer and normal cells are depicted in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Possible mechanisms of selective cytotoxicity of Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs in cancer and normal cells.

3. Conclusions

Pure and Zn-doped (1 and 3%) Bi2O3 NPs were synthesized by a facile chemical method. XRD spectra show that the tetragonal phase of β-Bi2O3 NPs did not change after Zn-doping. HR-TEM and SEM mapping demonstrated the homogeneous distribution of Zn in Bi2O3 with high-quality lattice fringes with no distortion. PL study revealed that the intensity of Bi2O3 NPs decreases with increasing level of Zn-doping. Cytotoxicity studies demonstrated that Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs induce higher toxicity to cancer cells (A549 and HepG2) than those of pure Bi2O3 NPs, and intensity of toxicity increases with increasing concentration of Zn-doping. Mechanistic study indicated that Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs induce toxicity in cancer cells by ROS generation and caspase-3 activation. On the other hand, biocompatibility of Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs in normal cells (primary rat hepatocytes) was greater than that of pure Bi2O3 NPs. Our data provide an alternative strategy for cancer therapy using Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs. This study warrants further research on antitumor activity of Zn-doped Bi2O3 NPs in suitable in vivo models.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis of Pure and Zn-Doped Bi2O3 NPs

Bismuth nitrate (Bi2(NO3)2·5H2O), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and zinc acetate (Zn(CH3COO)2·2H2O) were used as starting materials. All the chemicals were of analytical grade and used as received from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Zinc-doped (1 and 3 mol %) Bi2O3 was prepared by dissolving 1 M bismuth nitrate into 50 mL of deionized water. Then, the stoichiometric amount of zinc acetate dissolved in 50 mL of deionized water was added under magnetic stirring. Moreover, 0.1 M NaOH dissolved in 50 mL of deionized water was added dropwise to the abovementioned solution under stirring. This mixture solution was magnetically stirred for 5 h at 80 °C until a light-yellow precipitate was appeared. Then, the precipitate was washed several times with deionized water and filtered. The precipitate was dried in an oven at 100 °C for 2 h and further annealed at 500 °C for 3 h in a muffle furnace to get Zn-doped (1 and 2 mol %) Bi2O3 NPs. The same protocol was applied for the preparation pure Bi2O3 NPs without adding zinc acetate. A schematic diagram of Zn-doped Bi2O3 NP preparation is provided in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of Zn-doped Bi2O3 NP preparation.

4.2. Characterization

The purity of phase and crystalline nature of prepared pure and Zn-doped (1 and 3%) Bi2O3 NPs were assessed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) (PanAnalytic X’Pert Pro, Malvern Instruments, UK) with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 0.15405 nm, at 45 kV and 40 mA). Structural characterization was carried out by FETEM (JEM-2100F, JEOL, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). In brief, stock suspension of NPs (1 mg/mL in deionized water) further diluted into an appropriate working suspension (50 μg/mL in deionized water). This suspension was sonicated for 15 min at 40 W in a water bath sonicator (Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL, USA). Then, a drop of working suspension of NPs was poured onto TEM grid and air-dried, and the TEM measurements were carried out. Elemental composition assessed by EDS. Surface morphology and elemental mapping were assessed by FESEM (JSM-7600F, JEOL, Inc.). The photoluminescence spectra were observed using a fluorescent spectrophotometer (Hitachi F-4600).

Aqueous behavior of prepared NPs in deionized water and complete culture medium (DMEM + FBS) was carried out by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (ZetaSizer, Nano-HT, Malvern Instruments). In brief, NPs were suspended in deionized water and culture medium at a concentration of 400 μg/mL and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Then, suspensions were sonicated for 15 min at 40 W in a water bath sonicator (Cole-Parmer) and the DLS measurements were carried out.

4.3. Cell Culture

The A549 and HepG2 cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA, USA). Primary rat hepatocytes were isolated by collagenase perfusion methods as described earlier.41 Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) or Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 100 μg/mL of streptomycin (Invitrogen), 100 U/mL of penicillin (Invitrogen), and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen). Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator (5% CO2 supply at 37 °C). At 80–85% confluence, cells were harvested with trypsin (Invitrogen) and subcultured.

4.4. Preparation of Stock Solution of Pure and Zn-Doped Bi2O3 NPs and Exposure Protocol

Stock suspension (1 mg/mL) and different dilutions (1–400 μg/mL) of pure and Zn-doped (1 and 3%) Bi2O3 NPs were prepared in complete culture medium (DMEM + 10% FBS). Different dilutions were sonicated in a water bath for 15 min at 40 W to avoid agglomeration of NPs before exposure to cells. For cytotoxicity endpoint assay, cells were treated for 24 h to various concentrations (0, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 200, and 400 μg/mL) of pure and Zn-doped (1 and 3%) Bi2O3 NPs. For ROS and caspase-3 enzyme assays, cells were exposed for 24 h to a moderate concentration of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs (50 μg/mL). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (200 μM) was used as the positive control in ROS and caspase-3 enzyme assays. Cells without NPs served as the negative control.

4.5. Cytotoxicity Assay

Cell viability was examined by MTT assay42 with some modifications.43 The MTT assay is based on the principle of the ability of mitochondria of living cells to reduce MTT salt into blue formazan crystals. These crystals dissolved in acidified isopropanol and absorbance was recorded at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Synergy-HT, BioTek, Vinnoski, VT, USA).

The probe 2,7-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) was applied to assess the intracellular generation of ROS after exposure to 50 μg/mL of 3% Zn–Bi2O3 NPs for 24 h. The DCGH-DA is a cell-permeable nonfluorescent dye, converted into highly fluorescent DCF when oxidized by intracellular ROS.44 The fluorescence of DCF was measured at the 485 nm excitation and the 520 nm emission using a microplate reader (Synergy-HT, BioTek).

The cell extract was prepared for caspase-3 enzyme assay. In brief, cells were cultured in 75 cm2 culture flask and exposed to 50 μg/mL of 3%Zn–Bi2O3 NPs for 24 h. Then, cells were harvested in ice-cold phosphate buffer saline by scraping and washed with PBS at 4 °C. Cell pellets were further lysed in cell lysis buffer [1× 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1% Triton, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate]. After centrifugation (15,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C), the supernatant (cell extract) was stored at 4 °C for further experiment. The fluorometric assay of the caspase-3 enzyme was examined using the 7-amido-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin (AFC) standard.45 Protein content in the cell extract was quantified using Bradford’s protocol which was adapted to measure the protein level.46

4.6. Statistical Analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dennett’s multiple comparison tests was used for statistical analysis of biological results. The p < 0.05 was ascribed as statistically significant. All the biological quantitative data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments (n = 3).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this work through research group no. RG- 1439-072.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Marcus E. A.; Sachs G.; Scott D. R. Colloidal Bismuth Subcitrate Impedes Proton Entry into Helicobacter Pylori and Increases the Efficacy of Growth-Dependent Antibiotics. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 42, 922–933. 10.1111/apt.13346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli M.; Jagdale P.; Tagliaferro A. A Short Review on Biomedical Applications of Nanostructured Bismuth Oxide and Related Nanomaterials. Materials 2020, 13, 5234. 10.3390/ma13225234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. A.; Deacon G. B.; Jackson W. R.; Tiekink E. R. T.; Rainone S.; Webster L. K. Preparation and Anti-Tumour Activity of Some Arylbismuth(Iii) Oxine Complexes. Met. Base. Drugs 1998, 5, 295–304. 10.1155/mbd.1998.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuchi K.; Hatano Y.; Yagura T. Heterocyclic Organobismuth(III) Induces Apoptosis of Human Promyelocytic Leukemic Cells through Activation of Caspases and Mitochondrial Perturbation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008, 76, 974–986. 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogan D.; Griffith D. Current and Potential Applications of Bismuth-Based Drugs. Molecules 2014, 19, 15258–15297. 10.3390/molecules190915258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R.; Li H.; Sun H.. Bismuth: Environmental Pollution and Health Effects. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Health, 2nd ed.; Elsevier, 2019; pp 415–423. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazi M.-A.; Faghfouri L.; Ferreira M. P. A.; Figueiredo P.; Maleki H.; Sefat F.; Hirvonen J.; Santos H. A. The Versatile Biomedical Applications of Bismuth-Based Nanoparticles and Composites: Therapeutic, Diagnostic, Biosensing, and Regenerative Properties. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 1253–1321. 10.1039/c9cs00283a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Yang X.; Zhao K.; Xu P.; Zong L.; Yu R.; Wang D.; Deng J.; Chen J.; Xing X. Precursor-induced fabrication of β-Bi2O3 microspheres and their performance as visible-light-driven photocatalysts. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 9069–9074. 10.1039/c3ta11652b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Zainudin N. H.; Razak K. A.; Abidin S. Z.; Abdullah R.; Rahman W. N. Influence of Bismuth Oxide Nanoparticles on Bystander Effects in MCF-7 and HFOB 1.19 Cells under 10 MV Photon Beam Irradiation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2020, 177, 109143. 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2020.109143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abudayyak M.; Öztaş E.; Arici M.; Özhan G. Investigation of the Toxicity of Bismuth Oxide Nanoparticles in Various Cell Lines. Chemosphere 2017, 169, 117–123. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed M.; Akhtar M. J.; Khan M. A. M.; Alrokayan S. A.; Alhadlaq H. A. Oxidative Stress Mediated Cytotoxicity and Apoptosis Response of Bismuth Oxide (Bi2O3) Nanoparticles in Human Breast Cancer (MCF-7) Cells. Chemosphere 2019, 216, 823–831. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.10.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perillo B.; Di Donato M.; Pezone A.; Di Zazzo E.; Giovannelli P.; Galasso G.; Castoria G.; Migliaccio A. ROS in Cancer Therapy: The Bright Side of the Moon. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 192–203. 10.1038/s12276-020-0384-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar M. J.; Ahamed M.; Alhadlaq H. A.; Alshamsan A. Mechanism of ROS Scavenging and Antioxidant Signalling by Redox Metallic and Fullerene Nanomaterials: Potential Implications in ROS Associated Degenerative Disorders. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 802–813. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behzad F.; Naghib S. M.; kouhbanani M. A. J.; Tabatabaei S. N.; Zare Y.; Rhee K. Y. An Overview of the Plant-Mediated Green Synthesis of Noble Metal Nanoparticles for Antibacterial Applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 94, 92–104. 10.1016/j.jiec.2020.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Circu M. L.; Aw T. Y. Reactive Oxygen Species, Cellular Redox Systems, and Apoptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 48, 749–762. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar M. J.; Ahamed M.; Kumar S.; Majeed Khan M. A.; Ahmad J.; Alrokayan S. A. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Selectively Induce Apoptosis in Human Cancer Cells through Reactive Oxygen Species. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 845–857. 10.2147/ijn.s29129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed M.; Akhtar M. J.; Khan M. M.; Alhadlaq H. A. SnO2-Doped ZnO/Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites: Synthesis, Characterization, and Improved Anticancer Activity via Oxidative Stress Pathway. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 89–104. 10.2147/ijn.s285392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed M.; Akhtar M. J.; Khan M. A. M.; Alhadlaq H. A. Co-Exposure of Bi2O3 Nanoparticles and Bezo[a]Pyrene-Enhanced in Vitro Cytotoxicity of Mouse Spermatogonia Cells. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 17109–17118. 10.1007/s11356-020-12128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed M.; Khan M. A. M.; Akhtar M. J.; Alhadlaq H. A.; Alshamsan A. Ag-Doping Regulates the Cytotoxicity of TiO2 Nanoparticles via Oxidative Stress in Human Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17662. 10.1038/s41598-017-17559-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen Fatima M. J.; Navaneeth A.; Sindhu S. Improved Carrier Mobility and Bandgap Tuning of Zinc Doped Bismuth Oxide. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 2504–2510. 10.1039/c4ra12494d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viruthagiri G.; Kannan P.; Shanmugam N. Photocatalytic Rendition of Zn2+-Doped Bi2O3 Nanoparticles. Photonics Nanostruct.: Appl. Nematol. 2018, 32, 35–41. 10.1016/j.photonics.2018.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed M.; Khan M. A. M.; Akhtar M. J.; Alhadlaq H. A.; Alshamsan A. Role of Zn Doping in Oxidative Stress Mediated Cytotoxicity of TiO2 Nanoparticles in Human Breast Cancer MCF-7 Cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30196. 10.1038/srep30196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malathy P.; Vignesh K.; Rajarajan M.; Suganthi A. Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance of Transition Metal Doped Bi2O3 Nanoparticles under Visible Light Irradiation. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 101–107. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2013.05.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarese F.; Raimondi V.; Sharova E.; Silic-Benussi M.; Ciminale V. Nanoparticles as Tools to Target Redox Homeostasis in Cancer Cells. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 211. 10.3390/antiox9030211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo F.; Clogston J.; Calzolai L.; Rösslein M.; Prina-Mello A. Measuring Particle Size Distribution of Nanoparticle Enabled Medicinal Products, the Joint View of EUNCL and NCI-NCL. A Step by Step Approach Combining Orthogonal Measurements with Increasing Complexity. J. Controlled Release 2019, 299, 31–43. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud N. N.; Albasha A.; Hikmat S.; Hamadneh L.; Zaza R.; Shraideh Z.; Khalil E. A. Nanoparticle Size and Chemical Modification Play a Crucial Role in the Interaction of Nano Gold with the Brain: Extent of Accumulation and Toxicity. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 1669–1682. 10.1039/c9bm02072a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B.; Iocozzia J.; Zhao L.; Zhang H.; Harn Y.-W.; Chen Y.; Lin Z. Barium Titanate at the Nanoscale: Controlled Synthesis and Dielectric and Ferroelectric Properties. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 1194–1228. 10.1039/c8cs00583d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada A.; Ichimaru H.; Kawagoe T.; Tsushida M.; Niidome Y.; Tsutsuki H.; Sawa T.; Niidome T. Gold-Treated Silver Nanoparticles Have Enhanced Antimicrobial Activity. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 92, 297–301. 10.1246/bcsj.20180232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haghniaz R.; Rabbani A.; Vajhadin F.; Khan T.; Kousar R.; Khan A. R.; Montazerian H.; Iqbal J.; Libanori A.; Kim H.-J.; Wahid F. Anti-bacterial and wound healing-promoting effects of zinc ferrite nanoparticles. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 38. 10.1186/s12951-021-00776-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L.; Rosli N. F.; Chia H. L.; Guan J.; Pumera M. Self-Propelled Autonomous Mg/Pt Janus Micromotor Interaction with Human Cells. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 92, 1754–1758. 10.1246/bcsj.20190104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazal S.; Akbari A.; Hosseini H. A.; Sabouri Z.; Forouzanfar F.; Khatami M.; Darroudi M. Biosynthesis of Silver-Doped Nickel Oxide Nanoparticles and Evaluation of Their Photocatalytic and Cytotoxicity Properties. Appl. Phys. A 2020, 126, 480. 10.1007/s00339-020-03664-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miri A.; Sarani M.; Khatami M. Nickel-Doped Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles: Biosynthesis, Cytotoxicity and UV Protection Studies. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 3967–3977. 10.1039/c9ra09076b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Delgadillo R.; García-Cuellar C. M.; Sánchez-Pérez Y.; Pineda-Aguilar N.; Martínez-Martínez M. A.; Rangel-Padilla E. E.; Nakagoshi-Cepeda S. E.; Solís-Soto J. M.; Sánchez-Nájera R. I.; Nakagoshi-Cepeda M. A. A.; Chellam S.; Cabral-Romero C. In Vitro Evaluation of the Antitumor Effect of Bismuth Lipophilic Nanoparticles (BisBAL NPs) on Breast Cancer Cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 6089–6097. 10.2147/ijn.s179095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang R.; Yang Y.; Tong X.; Yang Y.; Tao H.; Zong T.; Feng K.; Jia P.; Cao P.; Guo N.; Chang H.; Zhou S.; Miao Y. Potential Anti-Cancer Activity of a Novel Bi(III) Containing Thiosemicarbazone Derivative. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2016, 73, 138–141. 10.1016/j.inoche.2016.10.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bogusz K.; Tehei M.; Cardillo D.; Lerch M.; Rosenfeld A.; Dou S. X.; Liu H. K.; Konstantinov K. High toxicity of Bi(OH)3 and α-Bi2O3 nanoparticles towards malignant 9L and MCF-7 cells. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2018, 93, 958–967. 10.1016/j.msec.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed M.; Akhtar M. J.; Raja M.; Ahmad I.; Siddiqui M. K. J.; AlSalhi M. S.; Alrokayan S. A. ZnO Nanorod-Induced Apoptosis in Human Alveolar Adenocarcinoma Cells via P53, Survivin and Bax/Bcl-2 Pathways: Role of Oxidative Stress. Nanomedicine 2011, 7, 907–913. 10.1016/j.nano.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najahi-Missaoui W.; Arnold R. D.; Cummings B. S. Safe Nanoparticles: Are We There Yet?. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 385. 10.3390/ijms22010385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchman J. T.; Hudson-Smith N. V.; Landy K. M.; Haynes C. L. Understanding Nanoparticle Toxicity Mechanisms to Inform Redesign Strategies to Reduce Environmental Impact. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 1632–1642. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z.; Li Q.; Wang J.; Yu Y.; Wang Y.; Zhou Q.; Li P. Reactive Oxygen Species-Related Nanoparticle Toxicity in the Biomedical Field. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 115. 10.1186/s11671-020-03344-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.-W.; Lee C.-H.; Lin M.-S.; Chi C.-W.; Chen Y.-J.; Wang G.-S.; Liao K.-W.; Chiu L.-P.; Wu S.-H.; Huang D.-M.; Chen L.; Shen Y.-S. ZnO Nanoparticles Induced Caspase-Dependent Apoptosis in Gingival Squamous Cell Carcinoma through Mitochondrial Dysfunction and P70S6K Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1612. 10.3390/ijms21051612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldéus P.; Högberg J.; Orrenius S. [4] Isolation and use of liver cells. Methods Enzymol. 1978, 52, 60–71. 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)52006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival: Application to Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed M.; Akhtar M. J.; Siddiqui M. A.; Ahmad J.; Musarrat J.; Al-Khedhairy A. A.; AlSalhi M. S.; Alrokayan S. A. Oxidative Stress Mediated Apoptosis Induced by Nickel Ferrite Nanoparticles in Cultured A549 Cells. Toxicology 2011, 283, 101–108. 10.1016/j.tox.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui M. A.; Alhadlaq H. A.; Ahmad J.; Al-Khedhairy A. A.; Musarrat J.; Ahamed M. Copper Oxide Nanoparticles Induced Mitochondria Mediated Apoptosis in Human Hepatocarcinoma Cells. PLoS One 2013, 8, e69534 10.1371/journal.pone.0069534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar M. J.; Ahamed M.; Alhadlaq H. Gadolinium Oxide Nanoparticles Induce Toxicity in Human Endothelial Huvecs via Lipid Peroxidation, Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Autophagy Modulation. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1675. 10.3390/nano10091675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]