Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma are chronic respiratory diseases with high prevalence and mortality that significantly alter the quality of life in affected patients. While the cellular and molecular mechanisms engaged in the development and evolution of these two conditions are different, COPD and asthma share a wide array of symptoms and clinical signs that may impede differential diagnosis. However, the distinct signaling pathways regulating cough and airway hyperresponsiveness employ the interaction of different cells, molecules, and receptors. Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) plays a major role in cough and airway inflammation. Consequently, its agonist, capsaicin, is of substantial interest in exploring the cellular effects and regulatory pathways that mediate these respiratory conditions. Increasingly more studies emphasize the use of capsaicin for the inhalation cough challenge, yet the involvement of TRPV1 in cough, bronchoconstriction, and the initiation of inflammation has not been entirely revealed. This review outlines a comparative perspective on the effects of capsaicin and its receptor in the pathophysiology of COPD and asthma, underlying the complex entanglement of molecular signals that bridge the alteration of cellular function with the multitude of clinical effects.

Keywords: capsaicin, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, cough, signaling pathways, inflammation, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1

1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma are two common respiratory diseases with distinct pathophysiology that share some clinical features such as cough, shortness of breath, and wheezing, making differential diagnosis an essential step in their management (1-3). Despite great progress in understanding the molecular mechanisms governing the development and evolution of these conditions, there is still room for improvement in setting an early diagnosis and providing effective therapy.

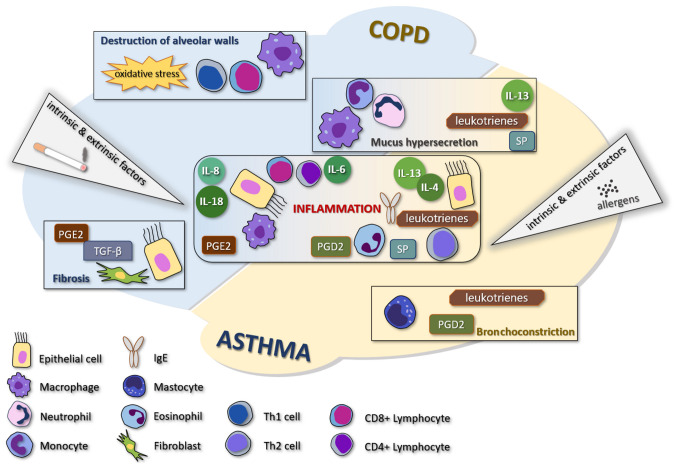

COPD is one of the most common causes of death, an important chronic morbidity, and is characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation due to anomalies of the airways and/or alveolae caused by exposure to toxic particles or gases (1). Asthma is a treatable and common disease that causes symptoms such as shortness of breath, chest tightness, and wheezing (2). Even though the two diseases are characterized by an obstructive syndrome, there are many differences between the two entities, the most representative consisting of the fact that COPD has less variability and is never completely cured, while asthma shows reversibility. Some patients may be affected by both diseases simultaneously (3). The comparative pathogenesis of COPD and asthma is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Comparative presentation of the most common cellular mechanisms involved in the development of the major symptoms and clinical elements of COPD and asthma. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; PG, prostaglandin; SP, substance P; IL-13, interleukin-13.

Capsaicin, the most pungent substance in chilli peppers, is an intensely studied molecule, with many applications in various diseases due to its anti-inflammatory and antitumoral properties (4-7). In the pulmonary system, capsaicin is used as an index of bronchial hypersensitivity, being able to produce cough and sustained bronchoconstriction, in a dose-dependent manner when inhaled (8-10). Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) is the receptor for capsaicin in the human body. Capsaicin cough challenge shows a good correlation with the presence or absence of pathological cough (11). Capsaicin is used in many studies as a chemical agent in the diagnosis or treatment of various disorders, including respiratory conditions (12-15). A better understanding of the effects of capsaicin in COPD and asthma may reveal new ways to diagnose and differentiate these diseases and potentially new directions of treatment.

2. Capsaicin and its receptor in the pulmonary system

Intensely studied in various conditions and on different experimental models, in the respiratory system, capsaicin has demonstrated great pleomorphism in its actions and is closely involved in triggering an abundance of signaling pathways, at times showing converse effects in pathological situations (16). Prolonged exposure to capsaicin aerosols such as those dispersed for crowd control may be toxic, irritating the respiratory tract and causing nerve damage (17,18). In extreme doses and under certain conditions, capsaicin may cause significant respiratory symptoms such as sneezing, cough, excessive mucus secretion, pain, and severe complications, and was demonstrated to be lethal in certain concentrations on test animals (18,19). Moreover, in murine models, it was shown that the intravenous administration of capsaicin instantly induces apnea, followed by an increase in the respiratory rate (20). These acute effects could be reduced by vagotomy, but not in all situations (20,21). However, in a clinical setting, when studying the beneficial effects of capsaicin in respiratory conditions, the doses of inhaled capsaicin are far too low to trigger significant adverse effects (22-24).

While capable of inducing direct effects, most of capsaicin's actions are mediated through its receptor, TRPV1. TRPV1 is a non-selective receptor that structurally belongs to the TRP family of ion channels. Besides capsaicin, it may be activated by different factors such as high temperature, acidity (pH <6.0), endocannabinoids, endogenous lipids, and other potential activators, such as numerous mediators of inflammation or various neurotransmitters (25,26). The receptor activation sends impulses to the spinal cord and brain producing a variety of effects, such as sensations of burning, stinging, itching, warming, or tingling. The terminations of the capsaicin-sensitive nerves include numerous neuropeptides, for example, substance P (SP) or calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). Their activation is followed by a temporary inflammatory process known as neurogenic inflammation because of the local release of pro-inflammatory peptides (27-30). Even though the number of TRPV1 receptors in the respiratory tract is not as high as in the other regions of the body (31), they can be found in all organs and structures of the respiratory system (32). Various pathogenic processes may influence the distribution of receptors, as was revealed in patients with emphysema which show higher levels of TRPV1 receptors in the respiratory system compared with healthy subjects (33,34). TRPV1 receptors are mainly expressed in lung C-fiber afferents (35) generally recognized as fibers with polymodal sensitivity, which originate from nociceptive neurons (36). Most C-fibers are receptive to capsaicin, which acts as an important respiratory irritant (37). TRPV1 was also identified in bronchial epithelial cells (28). Alongside TRPV1, the Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) receptor was revealed as being co-expressed in the airways in a population of C-fibers, and it was shown to be permeable to calcium ions (38). Although not directly stimulated by capsaicin, TRPA1 may be activated by various natural products (39), but also may be sensitized through inflammatory signaling pathways that also involve TRPV1, potentially contributing to increased chemical sensitivity (38,40,41).

TRPV1 may be activated by various ligands, including derivates of ployunsaturated fatty acids, oxytocin, neurotransmitters, chalcone derivatives, and cannabinoids (42-46). Cannabinoids are of particular interest, as they have demonstrated some similarities to capsaicin in regard to their anti-inflammatory and anti-tumoral effects in various organs, albeit some of these are mediated by specific receptors (47). Cannabinoids are not able to induce similar channel states as capsaicin on TRPV1 but they manage to target the receptor and can interact with other receptors from the TRP family, as well, which emphasises the potential interaction and synergic effects of these substances (48). Cannabinoids exert a series of TRPV1 effects and the modulation of the endocannabinoid system has proven extremely important in managing a variety of disorders affecting the central nervous system as well as conditions with intestinal, pulmonary, and cutaneous locations, a virtual structure termed ‘gut-lung-skin axis’ (49-52).

The activation of TRPV1 has demonstrated a variety of effects (53). Several studies have shown that TRPV1 agonists may cause apoptosis of human lung cells in alveolar epithelial cells (54,55). The inhalation of capsaicinoids for 30 min in rats causes an inflammatory reaction of the airways, destruction of epithelial cells of the trachea and nasal cavity, and injury to the bronchiolar and alveolar cells (54). Furthermore, an in vivo murine study has shown that a TRPV1 antagonism reduces the destruction of epithelial cells, preventing apoptosis (56). One of the frequently studied TRPV1 antagonists is capsazepine. Capsazepine is a specific antagonist of capsaicin-induced C-fiber activation and has been used to uncover additional roles of the TRPV1 receptor, specifically, its involvement in the onset of clinical respiratory symptoms (57-59).

TRPV1 may mediate cough (60) and bronchoconstriction, and the use of capsazepine reduces these symptoms in vivo (61). Furthermore, two additional TRPV1 antagonists demonstrated similar effects in inhibiting acid-induced cough in guinea pigs. These antagonists have similar effects and efficacy to that of codeine (62).

Within the respiratory system, identical signaling pathways regulate the onset of cough, bronchoconstriction, and airway narrowing, while also enhancing the sensation of irritation as well as fluid secretion. Stimulation of airway neurons may have favorable or unfavorable effects. It was reported that it might contribute to airway protection, disposing of chemical irritants and pathogens that cause infections, while preserving and initiating tissue recovery and favoring the immune responses in murine models (63,64). However, the stimulation of airway neurons may cause inflammation in the respiratory airways that complicates underlying diseases, as was demonstrated on TRPV1 neurons in mouse models of asthma (65). A recent study by Baral et al indicates that pulmonary TRPV1 neurons are involved in cross-talk with immune cells via CGRP, SP, glutamate, and other signaling molecules, showing that these neurons may cause neutrophil depletion as well as cytokine and T-cell release impairment (66). These converse findings reinforce the need to further study the cascade of intricate effects triggered by TRPV1 activation and to develop novel models capable of properly translating the in vivo actions of capsaicin. In some respiratory diseases, a variety of pro-inflammatory mediators and peptides are involved, such as histamine, prostaglandins, cysteinyl leukotrienes, proteases, growth factors, and bradykinin (64,67). Bradykinin is a pro-inflammatory molecule, acting through B1 and B2 receptors found in the respiratory system, which can also be involved in neuroinflammation associated with an increase in SP and CGRP (64). Bradykinin causes cough and bronchoconstriction (67,68) and is involved in airway chronic inflammation, responsiveness, and remodeling through activation of a variety of cells that cause these unfavorable effects (69).

Capsaicin and the major clinical respiratory symptoms

Inhaled capsaicin is the main agent for the measurement of cough reflex sensitivity because of a lack of side effects when properly administered, low price, and good correlation with the presence or absence of pathological cough. A review from 2005 that contained 122 published studies (1984-2005) on 4.833 subjects, including healthy subjects, patients with COPD, asthma, and other diagnoses, did not manage to isolate a single serious adverse effect of inhaled capsaicin in controlled conditions when using regulated concentrations (11). The usual symptoms reported during capsaicin cough challenge are increased cough, rhinorrhea, and throat and eye irritation (70).

Asthmatics without cough could not be differentiated from healthy individuals after the capsaicin cough challenge. Moreover, it was demonstrated that hyperresponsiveness of airways and cough were mediated through different neural pathways (71).

In vitro research using fiberoptic bronchoscopy in order to obtain mucosal biopsies from 29 patients with chronic cough showed an increase in the number of TRPV1 receptors in these subjects compared to 16 controls. Those data demonstrate a correlation between chronic cough and TRPV1 receptors. The cause of the increase was not determined. The subjects also received aerosols of a capsaicin solution dissolved in 0.9% sodium chloride until cough was produced five or more times. Results suggest an increased frequency of cough when capsaicin was inhaled by patients with chronic cough (72). In addition, cold air seems to increase the sensitivity of TRPV1 to capsaicin and increase cough sensitivity (73).

In an in vivo study on guinea pigs, the delivery of capsaicin by aerosol to the airways induced cough, while the administration of a capsaicin antagonist caused a decrease in the induced cough (74). The antagonist for capsaicin used in that study completely blocked the receptor for capsaicin and prevented its response to the variation of pH. Additionally, it inhibited the influx of Ca2+ that blocks the effects of capsaicin. This is paramount evidence of the major role of capsaicin in cough and is an important finding for basing future human trials. In terms of the action mechanism, it appears that the effects of capsaicin were carried on by direct TRPV1 effects but also mediated by tachykinins such as SP and neurokinin A (NKA) (74).

Long-term respiratory effects after exposure to capsaicin aerosols were analyzed in several major studies. Two studies showed no difference between hot pepper workers and healthy individuals in regard to their pulmonary function (75,76).

In vitro and in vivo studies suggested that capsaicin can be mutagenic; conversely, multiple studies revealed that topical, dietary, or injected capsaicin may demonstrate a chemoprotective effect (77-80).

Two decades of experience with capsaicin demonstrated that the capsaicin cough challenge is a safe investigation, and this procedure may prove to be an extremely important tool for future research.

The effects of capsaicin on mucus secretion in COPD and asthma were also investigated. In vitro, findings of several studies showed that SP stimulates mucus secretion in the respiratory system (81-83) and an increase of SP appears after stimulation of sensory nerves by capsaicin (84). In an in vivo study by Karmouty-Quintana et al increased mucus production caused by the activation of airway sensory nerves with intratracheal administered capsaicin was observed, and the results were confirmed showing a reduced level of mucin concentration after administration of capsazepine, a TRPV-1 antagonist. These effects seem to be mostly determined by SP, CGRP, and NKA released as a response to sensory nerve stimulation by capsaicin (85).

Dyspnea is a common respiratory symptom in both COPD and asthma, however, it has different attributes. In COPD, dyspnea is progressive and proportional to the airflow obstruction, while in asthma it appears simultaneously with the transitory bronchoconstriction (86). Dyspnea is a symptom that appears after the stimulation of adenosine receptors, and capsaicin shows no interference with these receptors (87). When investigated in clinical applications, no evidence that capsaicin may cause dyspnea was found, neither inhaled nor administered intravenously, in tolerable doses (88,89).

Smoking is a major causative and aggravating factor in lung inflammation. However, acute and chronic infection, whether viral, bacterial, or fungal, may influence the prognosis of these patients and their response to treatment (90). Some of the infections trigger exacerbations and cause a decline in lung function, while the patient does not benefit from effective therapeutical strategies, which poses significant problems in the management of these patients (91). The lung microbiome may experience changes related to the exacerbations and may influence biomarkers such as sputum neutrophils percentage and IL-8, as well as serum IL-10 and MMP-7(92). Capsaicin has demonstrated antimicrobial properties and may provide an added benefit in COPD patients with concurring infections, a research direction which needs to be further explored (93).

3. Capsaicin in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

COPD is one of the leading causes of death and an important chronic morbidity featuring limitation of airflow, cough, mucus hypersecretion, and dyspnea. It is caused by long-term exposure to toxic particles or gases, usually tobacco smoke, and may sometimes affect patients with various genetic abnormalities or concurring respiratory diseases (94). COPD demonstrates a steady increase in mortality and morbidity and is estimated to maintain this trend (95). Besides the clinical context, spirometry is necessary for the diagnosis by confirming the airflow limitation that is established when forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio is under 70% of the normal limits after the use of a bronchodilator (96). In their clinical evolution, patients with COPD can have periods of time when they show no symptoms, and periods of exacerbations (1).

Capsaicin, smoking and inflammation in COPD

Inflammation is one of the fundamental characteristics of COPD. It accelerates the disease progression and it is not reversible. Inflammation in COPD is usually a consequence of smoking, which is a major factor in the pathogenesis of COPD. Most cigarette smokers have a chronic cough, which is usually present prior to the onset of airflow obstruction. Smoking induces airway inflammation causing an increase in the number of neutrophils, macrophages, and T lymphocytes (CD8+ and CD4+) (97). These cells release a large number of cytokines and mediators that initiate and maintain the inflammatory process (98). The mediators with increased concentrations in COPD are leukotriene B4, neutrophil and T-cell chemoattractant, chemotactic factors such as interleukin (IL)-8 and growth-related oncogene α, pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF)-α, IL-1β, IL-6), and transforming growth factor-β (98,99). Alongside the inflammatory process, an imbalance between protease and antiprotease activity can be identified in COPD. This results from the intensified production and activity of proteases and decreased production and activity of antiprotease, caused by cigarette smoke and inflammation. Neutrophils release elastase, cathepsin G, and protease 3, while macrophages produce cysteine protease, cathepsins E, A, L, S, and matrix metalloproteinase-8, -9 and -12. α1 antitrypsin, secretory leucoprotease inhibitor, and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteases are the major antiproteases that participate in emphysema in COPD (31,98,100). The alteration of parasympathetic afferent and efferent fibers may contribute to the onset of bronchospasm, cough, and dyspnea (101).

In vivo, in a study on mice after exposure to cigarette smoke, the levels of leukocyte infiltration and the high level of inflammatory mediators caused the progression of COPD and the decline of lung function. These processes increased the production of IL-1β and IL-18, two cytokines released in association with the stimulating action of TRPV1 agonists, including capsaicin, in a cell-based model using primary human cells (33). Moreover, TRPV1 is found in CD4- T cells in mice. These receptors are activated after stimulation of the T-cell antigen receptor, which contributes to the influx of Ca2+. After this influx, the T cells are activated playing an important role in the development of inflammation. This process indicates that TRPV1 may have a fundamental function in the inflammatory process, particularly after smoke exposure, which is the main cause of COPD (102).

Recent studies also revealed the role of TRPV1 in mediating the effects of cigarette smoke on the alveolar epithelial cells through the increase of inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial damage (103,104). In patients with COPD, TRPV1 mRNA expression is increased in comparison with non-smokers (33).

The expression of TRPV1 is related to the intensity of the inflammatory process induced by cigarette smoking (105). In a mouse model, Jian et al have shown that the decreased expression of TRPV1 by using total flavonoids is followed by a subsequent decrease in the inflammation and oxidative stress in the lung parenchyma (106). A 2020 article has shown that single nucleotide polymorphisms of TRPV1 are associated with a higher risk of developing COPD in smokers (107).

In another study, human cells were exposed to cigarette smoking, and the expression of TRPV1 in pulmonary tissue was increased, as was the concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines (108).

Stimulation of TRPV1 in COPD releases inflammatory neuropeptides which increase vascular permeability, cause extravasation of plasma proteins, bronchoconstriction, and amplify the concentration of mucus (109,110). Mucus hypersecretion causes increased sputum production and seems to correlate with the severity of COPD (111).

Interestingly, in vitro studies showed that cigarette smoke can cause neuropeptide release by stimulating TRPA1 and acetylcholine receptors, contributing to the inflammatory process, with decreased or lack of TRPV1 involvement (112). Conversely, in vivo murine models suggest that the mediation of inflammation is exclusively performed by activation TRPV1 and 4, and not by TRPA1(33). These contradictory findings require the need for future studies, ideally on human subjects.

Capsaicin stimulates TRPV1 with further release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the airways. Activation of TRPV1 by capsaicin in patients with COPD stimulates the secretion of ILs, TNF-α, and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) (113). Special attention was paid to the capsaicin-induced stimulation of IL-6 production in human respiratory epithelial cells (114). IL-6 has a very important role in the transition from acute to chronic inflammation because it stimulates T-cells and B-cells. This stimulation favors a chronic inflammatory response due to the activation of endothelial cells that release IL-8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 and activate the expression of adhesion molecules (115). Nassini et al used mouse models and in vitro studies on human small airway epithelial cells, fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells exposed to cigarette smoke to demonstrate that capsaicin inhalation stimulates TRPV1 receptors in sensitive nerve fibers promoting neurogenic inflammation and favoring the release of IL-8, most likely through coactivation of TRPA1 receptors in non-neuronal cells (116). This mechanism may maintain and even increase inflammation in patients with COPD, enhancing its negative effects. Furthermore, bronchoconstriction may exacerbate the airflow limitation and intensify the dyspnea of patients.

Studying the in vivo response of the exposure of guinea pigs to cigarette smoke revealed that nebulized capsaicin enhances cough production in smoke-exposed animals, through a non-cyclo-oxygenase-mediated mechanism. The increased responsiveness to capsaicin appears to depend on sensory nerves containing CGRP-like substances (117). Moreover, while increasing sensitivity to capsaicin, exposure to smoke seems to decrease the response to PGE2, promoting the concept that sensory nerves are affected in COPD in a disease-specific manner (118).

A consensus was not yet reached regarding the overall effects of capsaicin in patients with airflow obstruction. A large cross-sectional study by Blanc et al (119) compared the effects of inhaled capsaicin on non-smokers and smokers with and without airflow obstruction. An increase of responsiveness in all groups of patients was demonstrated, more significantly in patients with COPD. Asymptomatic smokers registered no complaint, despite their hyperresponsiveness to capsaicin compared to non-smokers. In the same study, women were more sensitive than men in all three groups (119). However, no correlation was identified between the cough response intensity and the degree of airflow obstruction in COPD patients appreciated by FEV1 values, and these findings were confirmed in another study, by Doherty et al (120). Conversely, research data published in 1999 showed no significant difference in cough sensitivity to capsaicin between patients with COPD and airflow obstruction compared to healthy controls (121).

Capsaicin and cough in COPD

TRP channels have a protective role in physiological situations when the airways are not affected by pathological changes. In a disorder such as COPD, this role can be altered, and TRP channels may be responsible for the symptoms of COPD, especially cough and they may also participate in the inflammatory process identified in COPD (32).

Cough is usually the first symptom in patients with COPD. Cough may be sporadic and sometimes unproductive (1), it can affect the quality of life in patients with COPD and this is an important reason to research it and potentially identify new therapies (122). C and Aδ fibers are expressed in the mechanism of pathological cough, so TRP ion channels are an important component of this process (38). Capsaicin is the most common and usable agonist of TRPV1, used in a variety of studies on patients with chronic cough, a category that includes patients suffering from COPD (123,124).

Several clinical studies using capsaicin aerosols have been developed for patients with cough and COPD. Capsaicin responsiveness and cough in COPD was researched in a study by Doherty et al (120). The presented data suggest that inhaled capsaicin caused an increase in cough in patients with COPD and no relationship between cough and airflow limitation after exposure to capsaicin was observed (120). Another study, by Terada et al (125), showed an increase in the number and frequency of exacerbations after capsaicin inhalation in patients with COPD compared to controls, demonstrated by lower concentrations of capsaicin needed to produce five or more coughs; furthermore, bronchial hypersensitivity correlated with the frequency of exacerbations and the serum C-reactive protein, indicating that ongoing airway inflammation is associated with hypersensitivity of the cough reflex to capsaicin and may precipitate the exacerbations (125). Capsaicin cough challenge may be an important aid in assessing, managing COPD and its complications, and advancing the development of a new antitussive therapy. It does not yield serious adverse effects as it was demonstrated in a paper reviewing 20 years of practicing capsaicin cough challenge (11). A cough challenge test performed on 20 patients with exacerbated COPD revealed that their sensitivity to capsaicin was increased compared to the repeated test after recovery, and if hypersensitivity was maintained during recovery this announced future exacerbations (126).

4. Capsaicin in asthma

Asthma is a chronic, frequent, and treatable pulmonary disease characterized by respiratory symptoms, limitation of activity, and exacerbations that occasionally need urgent medical care, and can be a potentially lethal condition. The most common respiratory symptoms in asthma are wheezing, shortness of breath, cough, chest tightness, and variable expiratory airflow. The main risk factors that may aggravate asthma are viral infections, allergens, tobacco smoke, pollens, food, drugs, or exercise. Spirometry is required to set the diagnosis: FEV1 increases by 12% and a minimum of 200 ml of the baseline values post-bronchodilator (2).

Asthma is regarded as a typical Th2 disease, with increased immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels, airway inflammation, and the presence of numerous eosinophils. Usually, patients begin suffering from asthma in childhood. The allergens are inhaled and stimulate Th2-helper cell proliferation and the increase of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 levels (127). A fundamental characteristic of these patients is long-term airway inflammation. Consequently, chronicity and disease evolution disease may occur. The roles of IL-4 are to support B-cell isotype swapping, increase the response of stimulus of adhesion molecules, eotaxin creation, and improvement of airway hyperresponsiveness and goblet cell metaplasia (128-130). IL-13 partly shares its receptor with IL-4 and plays a critical role in the pathophysiology of asthma by increasing mucus secretion and modulating the functions of epithelial cells (131). Eosinophils and IgE are also of great importance in asthma and act via distinctive pathways which do not interfere with the mechanisms of IL-13 (132,133).

TRPV1 and allergens in asthma

TRPV1 may play important roles in the modulation of the pathogenic changes occurring in asthma (105). The expression of TRPV1 and Th2 levels seems to correlate with the asthmatic debut in the pediatric population (134). Recent data showed that TRPV1 can mediate the response of epithelial cells to allergens, increasing IL-33 secretion and the activation of dual oxidase 1 and epidermal growth factor receptor (135). Furthermore, an in vivo study on mice published in 2020 has shown that TRPV1 stimulates the production of mucus and cytokines in asthma by regulating the expression of MUC5AC and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B-cell pathway, with probable involvement of neuropeptides SP and CGRP (136). TRPV1 also mediates the appearance of cough via a neuronal mechanism and shows increased expression after exposure to allergens (137,138). Although expressed on airway smooth muscle cells, TRPV1 activation does not significantly contribute to the initiation of bronchoconstriction (139). In vitro studies have shown that coal fly ash causes TRPV1 activation and worsens asthma symptom control (140). A study on ovalbumin (OVA)-induced asthmatic mice showed that exposure to nanoparticles causes neuroinflammation mediated through TRPV1 and TRPV4, and is accompanied by an increase in SP, CGRP, and bradykinin (64). A similar study showed that a pollutant known as trimellitic anhydride can increase TRPV1 expression as well as amplify the levels of IL-13, SP, prostaglandin D2, and nerve growth factor in the lungs of OVA asthmatic mice (141). In the same experimental model, Li et al identified ozone as an environmental pollutant with similar effects on TRPV1 and the inflammation pattern in asthma as the allergens mentioned above (142). Small particulate matter can also inflict bronchial mucosal damage and thickening of bronchial smooth muscles in asthmatic mice (143). Combining pollutants builds a model closer to real-life situations (144), and, by doing so on allergic Balb/c mice, activation of TRPV1 signaling and increases of CGRP and SP levels were observed contributing to the neurogenic inflammation of asthma (145). Allergen exposure may lead to pathological changes outside the respiratory tract. In an in vivo study, Spaziano et al (146) showed that sensitization of the nucleus solitary tract (NST) occurs following exposure to allergens, and this is a basis for increased airway sensitivity. When capsaicin was inhaled, an increase in the neural firings of the NST were identified. However, TRPV1 may play a complex role in modulating excitation as its activation by endocannabinoids may stimulate glutamatergic signaling and alter the bronchoconstrictive reflex (146).

These observations were demonstrated by studies on the same animal model showing that inhibition of the TRPV1 mRNA and protein expression using various antagonists including capsazepine caused an improvement in pulmonary function, decreased airway hyperresponsiveness, and reduced cytokine concentrations in aggravated asthma (145,147-149). In addition, the use of allergens to induce bronchoconstriction seems to increase the TRPV1 response to capsaicin, increasing cough reflex sensitivity, as demonstrated in a recent clinical trial (150). The effects of stimulating TRPV1 receptors with capsaicin are increased in mice with atopic dermatitis to the extent that asthmatic-like inflammation of the airways is produced while compliance of the lungs is decreased (151).

In an in vitro study, by McGarvey et al, the TRPV1 protein was found in a culture with primary bronchial epithelial cells through patch-clamp experiments. That study confirmed that capsaicin induces the release of IL-8 especially in patients with chronic airway inflammation (152).

Capsaicin and inflammation in asthma

In asthma, chronic inflammation is one of the fundamental features of the disease. Inflammation progresses when inflammatory cells interact with local cells to create a cascade of events that triggers and maintains chronic inflammation and causes clinical symptoms. The consequences of inflammation in asthma are bronchospasm, airways mucus secretion and edema, bronchoconstriction, and bronchial epithelial damage (153).

The role of capsaicin in the process of inflammation in asthma is unclear, as some studies cite pro-inflammatory properties of capsaicin, while other recent studies revealed its anti-inflammatory effects (154).

However, TRPV1 activation seems to play an important role in the inflammatory cascade of asthma, and pharmacological inhibition of TRPV1 leads to a reduction in IgE levels as well as an attenuation of airway inflammation in mice (155).

In vitro, after using a TRPV1 antagonist, inflammation in the airway tissues of patients with chronic asthma was attenuated. These results may suggest that blocking TRPV1 may be a new direction for the anti-inflammatory treatment in asthma (156).

A study by Rehman et al showed in vivo that blocking TRPV1 in a murine model attenuates the symptomatology of asthma, probably by alleviating the inflammation of the airways. TRPV1 inhibition reduced the concentration of IL-13 and its effects on inflammation in the airways. Consequently, hyperresponsiveness and inflammation were reduced (157). Conversely, a different murine study revealed that inhibition of the TRPV1 gene may increase airway inflammation. The levels of the IgE, eosinophils, and IL-4 may be increased in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in this case. The authors revealed that the effects achieved by TRPV1 employ multiple mechanisms, both direct and mediated by SP, CGRP, NkA, and somatostatin (158).

Capsaicin and cough in asthma

Cough is a frequent and important symptom that influences the quality of life in patients with asthma (159) and is regulated by sensory nerves in the airways (60,160). In the previously mentioned in vitro study by McGarvey et al, the expression of TRPV1 in bronchial biopsies from asthmatics refractory to corticotherapy was found to be higher than that in patients without asthma or in those with asthma that were responsive to corticoids (152). Those findings were supported by Chen et al by analyzing TRPV1 mRNA in the peripheral blood of asthmatics and concluding that TRPV1 expression levels are major factors for bronchial asthma in children (161). As mentioned before, cold air seems to increase the effects of capsaicin on TRPV1, but humified warm air has been shown to trigger cough and bronchoconstriction in mild asthmatic patients via increased activation of C-fibers (162). While spirometry is useful in investigating the response of the large airways to capsaicin, impulse oscillometry system has proven more sensitive in detecting peripheral airway function in asthmatics and the changes induced by capsaicin (163).

In a study performed in vivo on asthmatic mice with cough, the inhalation of capsaicin caused a more frequent cough and was accompanied by eosinophil infiltration detected in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (164). There are also data showing neutrophil infiltration in the submucosal layer in asthmatic rats after the capsaicin cough challenge, an effect of both direct TRPV1 action as well as due to the release of neuropeptides (SP and CGRP) inducing neurogenic inflammation (165). A study on guinea pigs sensitized with capsaicin showed that the rate of coughs was notably increased, and the proposed mechanism was associated with airway tract eosinophilic inflammation (166).

Previous findings showed an increase in the frequency of cough in patients with asthma after inhalation of capsaicin. This is an effect of the hyperresponsiveness that characterizes patients with asthma. The mechanism probably involves neuronal dysfunction. When capsaicin stimulates the TRPV1 receptor, inflammatory mediators are released with further increased stimulation of the nerve fibers. This process determines membrane depolarization and release of the inflammatory mediators which are in high concentration in asthmatic patients (167). This is a possible explanation of why increased sensitivity to capsaicin has been identified as a risk factor for severe forms of asthma (168).

A study from 2019 comparing asthmatics and healthy controls showed no difference in the cough threshold after inhaled capsaicin between the two groups (163). However, in patients with asthma, the frequency of cough is higher than in healthy subjects. In addition, a higher sensitivity to capsaicin was identified in women and older patients (169). In asthmatic children, there is a decreased sensitivity to capsaicin compared to controls, which seems to be mediated by neurotransmitters released from parasympathetic neurons (170). This finding is strengthened by another recent study showing that some nervous phenotypes may induce excessive coughing in asthmatic patients due to a neuronal dysfunction (137,171). Capsaicin cough challenge is more sensitive in patients with cough-variant asthma even if bronchodilators were used in these patients (120). These patients have a lower quality of life because of their frequent exposure to irritants in daily life and due to their permanent discomfort. Research data have shown a direct correlation between the quality of life and sensitivity to capsaicin, as asthmatic patients with hyperactivity to inhaled capsaicin have a significantly poorer quality of life than controls (172,173).

A study published in 2020 tested the effects of inhaled capsaicin on 385 chronic cough patients, revealing that the capsaicin cough challenge is a proper method for investigating patients with variable clinical factors in asthma (174). Additionally, the test is a safe method to employ in severe asthma (175).

However, in regard to therapeutic prognostic, cough sensitivity to capsaicin may hold an important role in predicting the response to bronchial thermoplasty when used for treating patients with severe asthma (176). Alongside the different diagnostic benefits cited in asthma, capsaicin is a molecule gaining attention and is increasingly studied in animal models and human trials.

The intended finality of these findings is to improve the management of asthmatic cough. The use of the antimuscarinic bronchodilator Tiotropium has proved effective in controlling asthmatic cough in patients unresponsive to corticosteroids and long-acting β2 agonists, and it improved capsaicin cough reflex sensitivity, leading to the conclusion that its effects are mediated through sensory nerves, rather than effective bronchoconstrictors (177).

In summary, capsaicin demonstrates complex effects on cough and inflammation in COPD and asthma, either through direct TRPV1 activity or mediated by released factors, and these findings were summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Comparison of capsaicin effects on cough and inflammation in COPD and asthma.

| Component | Effect | Study type | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| COPD | |||

| Cough | Increase in frequency | In vitro (mucosal cells) | (60) |

| Increase in frequency | In vivo (guinea pigs) | (62) | |

| Increase in frequency | Trial | (104,109) | |

| Rise of exacerbation incidence | (109) | ||

| Inflammation | Release of IL-1α, TNF-α and PGE2 | In vitro (human primary bronchial fibroblasts) | (97) |

| Release IL-8 and pro-inflammatory cytokines | In vitro (primary bronchial epithelia cells) | (92,136) | |

| Release IL-1β and IL-18 | |||

| Maintain inflammation | In vivo (mice) | (32) | |

| Asthma | |||

| Cough | Increase in frequency | In vitro (bronchial cells) | (136) |

| Increase in frequency | In vivo (guinea pigs) | (149,150) | |

| Increase in frequency | Trial | (151,153) | |

| Inflammation | Pro-inflammatory | In vitro (bronchial cells) | (140) |

| Eosinophil infiltration | In vivo (guinea pigs) | (150) | |

| Pro- and anti-inflammatory | In vivo (mice) | (141,142) |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; PG, prostaglandin; IL, interleukin.

5. Conclusions

Capsaicin may exhibit a variety of clinical and paraclinical effects in COPD and asthma. Some are similar in both diseases, while others may be significantly different or opposite. In many cited studies, the frequency and intensity of cough are increased after capsaicin inhalation in COPD, while other authors report only an increase in the frequency of cough in asthmatic patients. The effects of capsaicin on inflammation in these two diseases are different. In COPD, several studies showed that capsaicin has pro-inflammatory effects, while, in asthma, the role of capsaicin in inflammation is unclear, as various studies showed conflicting results, citing pro-inflammatory as well as anti-inflammatory effects. Most authors revealed that the hyperresponsiveness to capsaicin is higher in smokers with airflow obstruction than non-smokers and smokers without airflow obstruction. Capsaicin appears to be a safe product as we failed to identify any studies showing an increase of dyspnea in COPD or asthma after capsaicin administration, when used in tolerable doses. Capsaicin may be a very promising, cost-effective, natural, and safe tool in expediting the diagnosis of COPD and asthma in the future, with increased accuracy in selected cases, especially due to its effects on cough and inflammation.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

Funding: This research and APC were funded by the following grants: PN.19.29.01.01/2019, PN-III-P1-1.2-PCCDI-2017-0341 and PN-III-P1-1.2-PCCDI-2017-0782.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

MDD, CS, and CCa conceived and designed the review. CS and CCa have developed the methodology and scientific approach. Preliminary documentation, data selection and analysis, writing and editing of the original draft were performed by MDD, ASJ, CS, IAB, GDAP, AC, DOC, RSC, CCo, MN, and CCa. Content review and editing were performed by CS, AC, and CCa. Supervision was conducted by IAB, CCo, MN, and CCa. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: Pocket Guide to COPD Diagnosis, Management and Prevention: A Guide for Health Care Professionals. Independently published, November 20, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Global Initiative for Asthma: Pocket Guide for Asthma Management: For Adults and Children over 5 years. Independently published, April 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collard CD. Harrison's Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. Tex Heart Inst J. 2010;37(736) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popescu GD, Scheau C, Badarau IA, Dumitrache MD, Caruntu A, Scheau AE, Costache DO, Costache RS, Constantin C, Neagu M, et al. The effects of capsaicin on gastrointestinal cancers. Molecules. 2020;26(26) doi: 10.3390/molecules26010094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheau C, Mihai LG, Bădărău IA, Caruntu C. Emerging applications of some important natural compounds in the field of oncology. Farmacia. 2020;68:984–991. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Căruntu C, Boda D. Evaluation through in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy of the cutaneous neurogenic inflammatory reaction induced by capsaicin in human subjects. J Biomed Opt. 2012;17(085003) doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.8.085003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frydas S, Varvara G, Murmura G, Saggini A, Caraffa A, Antinolfi P, Tete' S, Tripodi D, Conti F, Cianchetti E, et al. Impact of capsaicin on mast cell inflammation. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2013;26:597–600. doi: 10.1177/039463201302600303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuller RW, Dixon CM, Barnes PJ. Bronchoconstrictor response to inhaled capsaicin in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1985;58:1080–1084. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.58.4.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Midgren B, Hansson L, Karlsson JA, Simonsson BG, Persson CG. Capsaicin-induced cough in humans. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:347–351. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forsberg K, Karlsson JA, Theodorsson E, Lundberg JM, Persson CG. Cough and bronchoconstriction mediated by capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons in the guinea-pig. Pulm Pharmacol. 1988;1:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0952-0600(88)90008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dicpinigaitis PV, Alva RV. Safety of capsaicin cough challenge testing. Chest. 2005;128:196–202. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caruntu C, Negrei C, Ghita MA, Caruntu A, Ba AI. Capsaicin, a hot topic in skin pharmacology and physiology. Farmacia. 2015;63:487–491. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavaliere C, Masieri S, Cavaliere F. Therapeutic applications of capsaicin in upper airways. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19:1166–1176. doi: 10.2174/1389450118666171117123825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ternesten-Hasséus E, Johansson EL, Millqvist E. Cough reduction using capsaicin. Respir Med. 2015;109:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fattori V, Hohmann MS, Rossaneis AC, Pinho-Ribeiro FA, Verri WA. Capsaicin: Current understanding of its mechanisms and therapy of pain and other pre-clinical and clinical uses. Molecules. 2016;21(21) doi: 10.3390/molecules21070844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ilie MA, Caruntu C, Tampa M, Georgescu SR, Matei C, Negrei C, Ion RM, Constantin C, Neagu M, Boda D. Capsaicin: Physicochemical properties, cutaneous reactions and potential applications in painful and inflammatory conditions. Exp Ther Med. 2019;18:916–925. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Copeland S, Nugent K. Persistent respiratory symptoms following prolonged capsaicin exposure. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2013;4:211–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Satpute RM, Kushwaha PK, Nagar DP, Rao PV. Comparative safety evaluation of riot control agents of synthetic and natural origin. Inhal Toxicol. 2018;30:89–97. doi: 10.1080/08958378.2018.1451575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steffee CH, Lantz PE, Flannagan LM, Thompson RL, Jason DR. Oleoresin capsicum (pepper) spray and ‘in-custody deaths’. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1995;16:185–192. doi: 10.1097/00000433-199509000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedner J, Hedner T, Jonason J. Capsaicin and regulation of respiration: Interaction with central substance P. mechanisms. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 1985;61:239–252. doi: 10.1007/BF01251915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaczyńska K, Szereda-Przestaszewska M. Respiratory effects of capsaicin occur beyond the lung vagi in anaesthetized rats. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Warsz) 2000;60:159–165. doi: 10.55782/ane-2000-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar P, Deb U, Kaushik MP. Evaluation of oleoresin capsicum of Capsicum frutescenes var. Nagahari containing various percentages of capsaicinoids following inhalation as an active ingredient for tear gas munitions. Inhal Toxicol. 2012;24:659–666. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2012.709547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dicpinigaitis PV. Review: Effect of drugs on human cough reflex sensitivity to inhaled capsaicin. Cough. 2012;8(10) doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costanzo MT, Yost RA, Davenport PW. Standardized method for solubility and storage of capsaicin-based solutions for cough induction. Cough. 2014;10(6) doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tominaga M, Tominaga T. Structure and function of TRPV1. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:143–150. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1457-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filippi A, Caruntu C, Gheorghe RO, Deftu A, Amuzescu B, Ristoiu V. Catecholamines reduce transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 desensitization in cultured dorsal root ganglia neurons. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;67:843–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holzer P. Local effector functions of capsaicin-sensitive sensory nerve endings: Involvement of tachykinins, calcitonin gene-related peptide and other neuropeptides. Neuroscience. 1988;24:739–768. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Logu F, Patacchini R, Fontana G, Geppetti P. TRP functions in the broncho-pulmonary system. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38:321–329. doi: 10.1007/s00281-016-0557-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grigore O, Mihailescu AI, Solomon I, Boda D, Caruntu C. Role of stress in modulation of skin neurogenic inflammation. Exp Ther Med. 2019;17:997–1003. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.7058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghiţă MA, Căruntu C, Rosca AE, Căruntu A, Moraru L, Constantin C, Neagu M, Boda D. Real-time investigation of skin blood flow changes induced by topical capsaicin. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunert-Keil C, Bisping F, Krüger J, Brinkmeier H. Tissue-specific expression of TRP channel genes in the mouse and its variation in three different mouse strains. BMC Genomics. 2006;7(159) doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grace MS, Baxter M, Dubuis E, Birrell MA, Belvisi MG. Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels in the airway: Role in airway disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:2593–2607. doi: 10.1111/bph.12538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baxter M, Eltom S, Dekkak B, Yew-Booth L, Dubuis ED, Maher SA, Belvisi MG, Birrell MA. Role of transient receptor potential and pannexin channels in cigarette smoke-triggered ATP release in the lung. Thorax. 2014;69:1080–1089. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belvisi MG, Birrell MA. The emerging role of transient receptor potential channels in chronic lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(1601357) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01357-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fisher JT. The TRPV1 ion channel: Implications for respiratory sensation and dyspnea. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;167:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gu QD, Joe DS, Gilbert CA. Activation of bitter taste receptors in pulmonary nociceptors sensitizes TRPV1 channels through the PLC and PKC signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2017;312:L326–L333. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00468.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alamri A, Bron R, Brock JA, Ivanusic JJ. Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 expressing corneal sensory neurons can be subdivided into at least three subpopulations. Front Neuroanat. 2015;9(71) doi: 10.3389/fnana.2015.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bessac BF, Jordt SE. Breathtaking TRP channels: TRPA1 and TRPV1 in airway chemosensation and reflex control. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:360–370. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00026.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bandell M, Story GM, Hwang SW, Viswanath V, Eid SR, Petrus MJ, Earley TJ, Patapoutian A. Noxious cold ion channel TRPA1 is activated by pungent compounds and bradykinin. Neuron. 2004;41:849–857. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Millqvist E, Bende M, Löwhagen O. Sensory hyperreactivity--a possible mechanism underlying cough and asthma-like symptoms. Allergy. 1998;53:1208–1212. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1998.tb03843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brooks SM. Irritant-induced chronic cough: Irritant-induced TRPpathy. Lung. 2008;186 (Suppl 1):S88–S93. doi: 10.1007/s00408-007-9068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benso B, Bustos D, Zarraga MO, Gonzalez W, Caballero J, Brauchi S. Chalcone derivatives as non-canonical ligands of TRPV1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2019;112:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2019.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benítez-Angeles M, Morales-Lázaro SL, Juárez-González E, Rosenbaum T. TRPV1: Structure, endogenous agonists, and mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21) doi: 10.3390/ijms21103421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szallasi A, Sheta M. Targeting TRPV1 for pain relief: Limits, losers and laurels. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21:1351–1369. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.704021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muller C, Morales P, Reggio PH. Cannabinoid ligands targeting TRP channels. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;11(487) doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salehi B, Quispe C, Chamkhi I, El Omari N, Balahbib A, Sharifi-Rad J, Bouyahya A, Akram M, Iqbal M, Docea AO, et al. Pharmacological properties of chalcones: A review of preclinical including molecular mechanisms and clinical evidence. Front Pharmacol. 2021;11(592654) doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.592654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scheau C, Badarau IA, Mihai LG, Scheau AE, Costache DO, Constantin C, Calina D, Caruntu C, Costache RS, Caruntu A. Cannabinoids in the pathophysiology of skin inflammation. Molecules. 2020;25(25) doi: 10.3390/molecules25030652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Starkus J, Jansen C, Shimoda LMN, Stokes AJ, Small-Howard AL, Turner H. Diverse TRPV1 responses to cannabinoids. Channels (Austin) 2019;13:172–191. doi: 10.1080/19336950.2019.1619436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calina D, Buga AM, Mitroi M, Buha A, Caruntu C, Scheau C, Bouyahya A, El Omari N, El Menyiy N, Docea AO. The treatment of cognitive, behavioural and motor impairments from brain injury and neurodegenerative diseases through cannabinoid system modulation-evidence from in vivo studies. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9) doi: 10.3390/jcm9082395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karoly HC, Mueller RL, Bidwell LC, Hutchison KE. Cannabinoids and the microbiota-gut-brain axis: Emerging effects of cannabidiol and potential applications to alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2020;44:340–353. doi: 10.1111/acer.14256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ribeiro A, Almeida VI, Costola-de-Souza C, Ferraz-de-Paula V, Pinheiro ML, Vitoretti LB, Gimenes-Junior JA, Akamine AT, Crippa JA, Tavares-de-Lima W, et al. Cannabidiol improves lung function and inflammation in mice submitted to LPS-induced acute lung injury. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2015;37:35–41. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2014.976794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cintosun A, Lara-Corrales I, Pope E. Mechanisms of cannabinoids and potential applicability to skin diseases. Clin Drug Investig. 2020;40:293–304. doi: 10.1007/s40261-020-00894-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zholos AV. TRP channels in respiratory pathophysiology: the role of oxidative, chemical irritant and temperature stimuli. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13:279–291. doi: 10.2174/1570159x13666150331223118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reilly CA, Taylor JL, Lanza DL, Carr BA, Crouch DJ, Yost GS. Capsaicinoids cause inflammation and epithelial cell death through activation of vanilloid receptors. Toxicol Sci. 2003;73:170–181. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas KC, Sabnis AS, Johansen ME, Lanza DL, Moos PJ, Yost GS, Reilly CA. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 agonists cause endoplasmic reticulum stress and cell death in human lung cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:830–838. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.119412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Agopyan N, Head J, Yu S, Simon SA. TRPV1 receptors mediate particulate matter-induced apoptosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L563–L572. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00299.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cabral LD, Giusti-Paiva A. The transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 antagonist capsazepine improves the impaired lung mechanics during endotoxemia. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;119:421–427. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tani M, Kotani S, Hayakawa C, Lin ST, Irie S, Ikeda K, Kawakami K, Onimaru H. Effects of a TRPV1 agonist capsaicin on respiratory rhythm generation in brainstem-spinal cord preparation from newborn rats. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:327–338. doi: 10.1007/s00424-016-1912-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang J, Yu HM, Zhou XD, Kolosov VP, Perelman JM. Study on TRPV1-mediated mechanism for the hypersecretion of mucus in respiratory inflammation. Mol Immunol. 2013;53:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bonvini SJ, Belvisi MG. Cough and airway disease: The role of ion channels. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2017;47:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Belvisi MG, Miura M, Stretton D, Barnes PJ. Capsazepine as a selective antagonist of capsaicin-induced activation of C-fibres in guinea-pig bronchi. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;215:341–344. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leung SY, Niimi A, Williams AS, Nath P, Blanc FX, Dinh QT, Chung KF. Inhibition of citric acid- and capsaicin-induced cough by novel TRPV-1 antagonist, V112220, in guinea-pig. Cough. 2007;3(10) doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Talbot S, Abdulnour RE, Burkett PR, Lee S, Cronin SJ, Pascal MA, Laedermann C, Foster SL, Tran JV, Lai N, et al. Silencing nociceptor neurons reduces allergic airway inflammation. Neuron. 2015;87:341–354. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim BG, Park MK, Lee PH, Lee SH, Hong J, Aung MM, Moe KT, Han NY, Jang AS. Effects of nanoparticles on neuroinflammation in a mouse model of asthma. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2020;271(103292) doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2019.103292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tränkner D, Hahne N, Sugino K, Hoon MA, Zuker C. Population of sensory neurons essential for asthmatic hyperreactivity of inflamed airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:11515–11520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411032111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baral P, Umans BD, Li L, Wallrapp A, Bist M, Kirschbaum T, Wei Y, Zhou Y, Kuchroo VK, Burkett PR, et al. Nociceptor sensory neurons suppress neutrophil and γδ T cell responses in bacterial lung infections and lethal pneumonia. Nat Med. 2018;24:417–426. doi: 10.1038/nm.4501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abe K, Watanabe N, Kumagai N, Mouri T, Seki T, Yoshinaga K. Circulating kinin in patients with bronchial asthma. Experientia. 1967;23:626–627. doi: 10.1007/BF02144161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dolovich J, Back N, Arbesman CE. Kinin-like activity in nasal secretions of allergic patients. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1970;38:337–344. doi: 10.1159/000230287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ricciardolo FLM, Folkerts G, Folino A, Mognetti B. Bradykinin in asthma: Modulation of airway inflammation and remodelling. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;827:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ternesten-Hasséus E, Johansson K, Löwhagen O, Millqvist E. Inhalation method determines outcome of capsaicin inhalation in patients with chronic cough due to sensory hyperreactivity. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2006;19:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dicpinigaitis PV, Dobkin JB, Reichel J. Antitussive effect of the leukotriene receptor antagonist zafirlukast in subjects with cough-variant asthma. J Asthma. 2002;39:291–297. doi: 10.1081/jas-120002285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Groneberg DA, Niimi A, Dinh QT, Cosio B, Hew M, Fischer A, Chung KF. Increased expression of transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 in airway nerves of chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1276–1280. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-174OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Millqvist E. TRP channels and temperature in airway disease-clinical significance. Temperature. 2015;2:172–177. doi: 10.1080/23328940.2015.1012979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McLeod RL, Fernandez X, Correll CC, Phelps TP, Jia Y, Wang X, Hey JA. TRPV1 antagonists attenuate antigen-provoked cough in ovalbumin sensitized guinea pigs. Cough. 2006;2(10) doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blanc P, Liu D, Juarez C, Boushey HA. Cough in hot pepper workers. Chest. 1991;99:27–32. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lankatilake KN, Uragoda CG. Respiratory function in chilli grinders. Occup Med (Lond) 1993;43:139–142. doi: 10.1093/occmed/43.3.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Muralidhara , Narasimhamurthy K. Non-mutagenicity of capsaicin in albino mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 1988;26:955–958. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(88)90094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Surh YJ, Lee SS. Capsaicin in hot chili pepper: Carcinogen, co-carcinogen or anticarcinogen? Food Chem Toxicol. 1996;34:313–316. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(95)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Park KK, Surh YJ. Effects of capsaicin on chemically-induced two-stage mouse skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 1997;114:183–184. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)04657-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Georgescu SR, Sârbu MI, Matei C, Ilie MA, Caruntu C, Constantin C, Neagu M, Tampa M. Capsaicin: Friend or foe in skin cancer and other related malignancies? Nutrients. 2017;9(1365) doi: 10.3390/nu9121365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rogers DF, Aursudkij B, Barnes PJ. Effects of tachykinins on mucus secretion in human bronchi in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;174:283–286. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meini S, Mak JCW, Rohde JAL, Rogers DF. Tachykinin control of ferret airways: Mucus secretion, bronchoconstriction and receptor mapping. Neuropeptides. 1993;24:81–89. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(93)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ramnarine SI, Hirayama Y, Barnes PJ, Rogers DF. ‘Sensory-efferent’ neural control of mucus secretion: Characterization using tachykinin receptor antagonists in ferret trachea in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;113:1183–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Szallasi A, Blumberg PM. Vanilloid (Capsaicin) receptors and mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:159–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Karmouty-Quintana H, Cannet C, Sugar R, Fozard JR, Page CP, Beckmann N. Capsaicin-induced mucus secretion in rat airways assessed in vivo and non-invasively by magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150:1022–1030. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.O'Donnell DE, Elbehairy AF, Berton DC, Domnik NJ, Neder JA. Advances in the evaluation of respiratory pathophysiology during exercise in chronic lung diseases. Front Physiol. 2017;8(82) doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Smutzer G, Devassy RK. Integrating TRPV1 receptor function with capsaicin psychophysics. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2016;2016(1512457) doi: 10.1155/2016/1512457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Burki NK, Lee LY. Mechanisms of dyspnea. Chest. 2010;138:1196–1201. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Winning AJ, Hamilton RD, Shea SA, Guz A. Respiratory and cardiovascular effects of central and peripheral intravenous injections of capsaicin in man: evidence for pulmonary chemosensitivity. Clin Sci (Lond) 1986;71:519–526. doi: 10.1042/cs0710519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Leung JM, Tiew PY, Mac Aogáin M, Budden KF, Yong VF, Thomas SS, Pethe K, Hansbro PM, Chotirmall SH. The role of acute and chronic respiratory colonization and infections in the pathogenesis of COPD. Respirology. 2017;22:634–650. doi: 10.1111/resp.13032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Linden D, Guo-Parke H, Coyle PV, Fairley D, McAuley DF, Taggart CC, Kidney J. Respiratory viral infection: A potential “missing link” in the pathogenesis of COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28(28) doi: 10.1183/16000617.0063-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang Z, Bafadhel M, Haldar K, Spivak A, Mayhew D, Miller BE, Tal-Singer R, Johnston SL, Ramsheh MY, Barer MR, et al. Lung microbiome dynamics in COPD exacerbations. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:1082–1092. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01406-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Adaszek Ł, Gadomska D, Mazurek Ł, Łyp P, Madany J, Winiarczyk S. Properties of capsaicin and its utility in veterinary and human medicine. Res Vet Sci. 2019;123:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, Fukuchi Y, Jenkins C, Rodriguez-Roisin R, van Weel C, et al. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-456SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hillas G, Perlikos F, Tsiligianni I, Tzanakis N. Managing comorbidities in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:95–109. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S54473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eschenbacher WL. Defining Airflow Obstruction. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis (Miami) 2016;3:515–518. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.3.2.2015.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tetley TD. Inflammatory cells and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2005;4:607–618. doi: 10.2174/156801005774912824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang Y, Xu J, Meng Y, Adcock IM, Yao X. Role of inflammatory cells in airway remodeling in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:3341–3348. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S176122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sethi S, Mahler DA, Marcus P, Owen CA, Yawn B, Rennard S. Inflammation in COPD: Implications for management. Am J Med. 2012;125:1162–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Barbu C, Iordache M, Man MG. Inflammation in COPD: Pathogenesis, local and systemic effects. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2011;52:21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Audrit KJ, Delventhal L, Aydin Ö, Nassenstein C. The nervous system of airways and its remodeling in inflammatory lung diseases. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;367:571–590. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2559-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tóth BI, Benko S, Szöllosi AG, Kovács L, Rajnavölgyi E, Bíró T. Transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 signaling inhibits differentiation and activation of human dendritic cells. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1619–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang M, Zhang Y, Xu M, Zhang H, Chen Y, Chung KF, Adcock IM, Li F. Roles of TRPA1 and TRPV1 in cigarette smoke -induced airway epithelial cell injury model. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;134:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bose P, Bathri R, Kumar L, Vijayan VK, Maudar KK. Role of oxidative stress and transient receptor potential in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Indian J Med Res. 2015;142:245–260. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.166529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dietrich A. Modulators of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels as therapeutic options in lung disease. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2019;12(23) doi: 10.3390/ph12010023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jian T, Chen J, Ding X, Lv H, Li J, Wu Y, Ren B, Tong B, Zuo Y, Su K, et al. Flavonoids isolated from loquat (Eriobotrya japonica) leaves inhibit oxidative stress and inflammation induced by cigarette smoke in COPD mice: The role of TRPV1 signaling pathways. Food Funct. 2020;11:3516–3526. doi: 10.1039/c9fo02921d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Xiong M, Guo M, Huang D, Li J, Zhou Y. TRPV1 genetic polymorphisms and risk of COPD or COPD combined with PH in the Han Chinese population. Cell Cycle. 2020;19:3066–3073. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2020.1831246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Deering-Rice CE, Johansen ME, Roberts JK, Thomas KC, Romero EG, Lee J, Yost GS, Veranth JM, Reilly CA. Transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1) is a mediator of lung toxicity for coal fly ash particulate material. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;81:411–419. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.076067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Barnes PJ. Neurogenic inflammation in the airways. Respir Physiol. 2001;125:145–154. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wortley MA, Birrell MA, Belvisi MG. Drugs Affecting TRP Channels. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;237:213–241. doi: 10.1007/164_2016_63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tagaya E, Yagi O, Sato A, Arimura K, Takeyama K, Kondo M, Tamaoki J. Effect of tiotropium on mucus hypersecretion and airway clearance in patients with COPD. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2016;39:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kichko TI, Kobal G, Reeh PW. Cigarette smoke has sensory effects through nicotinic and TRPA1 but not TRPV1 receptors on the isolated mouse trachea and larynx. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;309:L812–L820. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00164.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sadofsky LR, Ramachandran R, Crow C, Cowen M, Compton SJ, Morice AH. Inflammatory stimuli up-regulate transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 expression in human bronchial fibroblasts. Exp Lung Res. 2012;38:75–81. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2011.644027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Seki N, Shirasaki H, Kikuchi M, Himi T. Capsaicin induces the production of IL-6 in human upper respiratory epithelial cells. Life Sci. 2007;80:1592–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gabay C. Interleukin-6 and chronic inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8 (Suppl 2)(S3) doi: 10.1186/ar1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nassini R, Pedretti P, Moretto N, Fusi C, Carnini C, Facchinetti F, Viscomi AR, Pisano AR, Stokesberry S, Brunmark C, et al. Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 channel localized to non-neuronal airway cells promotes non-neurogenic inflammation. PLoS One. 2012;7(e42454) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Karlsson JA, Zackrisson C, Lundberg JM. Hyperresponsiveness to tussive stimuli in cigarette smoke-exposed guinea-pigs: A role for capsaicin-sensitive, calcitonin gene-related peptide-containing nerves. Acta Physiol Scand. 1991;141:445–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1991.tb09105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Belvisi MG, Birrell MA, Khalid S, Wortley MA, Dockry R, Coote J, Holt K, Dubuis E, Kelsall A, Maher SA, et al. Neurophenotypes in airway diseases. Insights from translational cough studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:1364–1372. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201508-1602OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Blanc FX, Macedo P, Hew M, Chung KF. Capsaicin cough sensitivity in smokers with and without airflow obstruction. Respir Med. 2009;103:786–790. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Doherty MJ, Mister R, Pearson MG, Calverley PM. Capsaicin responsiveness and cough in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2000;55:643–649. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.8.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wong CH, Morice AH. Cough threshold in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54:62–64. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Deslee G, Burgel PR, Escamilla R, Chanez P, Court-Fortune I, Nesme-Meyer P, Brinchault-Rabin G, Perez T, Jebrak G, Caillaud D, et al. Impact of current cough on health-related quality of life in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2091–2097. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S106883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Morice AH, Millqvist E, Bieksiene K, Birring SS, Dicpinigaitis P, Domingo Ribas C, Hilton Boon M, Kantar A, Lai K, McGarvey L, et al. ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(55) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01136-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ternesten-Hasséus E, Larsson C, Larsson S, Millqvist E. Capsaicin sensitivity in patients with chronic cough- results from a cross-sectional study. Cough. 2013;9(5) doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Terada K, Muro S, Ohara T, Haruna A, Marumo S, Kudo M, Ogawa E, Hoshino Y, Hirai T, Niimi A, et al. Cough-reflex sensitivity to inhaled capsaicin in COPD associated with increased exacerbation frequency. Respirology. 2009;14:1151–1155. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cho PSP, Fletcher HV, Turner RD, Patel IS, Jolley CJ, Birring SS. The relationship between cough reflex sensitivity and exacerbation frequency in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lung. 2020;198:617–628. doi: 10.1007/s00408-020-00366-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Fahy JV. Type 2 inflammation in asthma - present in most, absent in many. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:57–65. doi: 10.1038/nri3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Mishra V, Banga J, Silveyra P. Oxidative stress and cellular pathways of asthma and inflammation: Therapeutic strategies and pharmacological targets. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;181:169–182. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Vieira Braga FA, Kar G, Berg M, Carpaij OA, Polanski K, Simon LM, Brouwer S, Gomes T, Hesse L, Jiang J, et al. A cellular census of human lungs identifies novel cell states in health and in asthma. Nat Med. 2019;25:1153–1163. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0468-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Danahay H, Pessotti AD, Coote J, Montgomery BE, Xia D, Wilson A, Yang H, Wang Z, Bevan L, Thomas C, et al. Notch2 is required for inflammatory cytokine-driven goblet cell metaplasia in the lung. Cell Rep. 2015;10:239–252. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Gour N, Wills-Karp M. IL-4 and IL-13 signaling in allergic airway disease. Cytokine. 2015;75:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wills-Karp M, Luyimbazi J, Xu X, Schofield B, Neben TY, Karp CL, Donaldson DD. Interleukin-13: Central mediator of allergic asthma. Science. 1998;282:2258–2261. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Webb DC, McKenzie AN, Koskinen AM, Yang M, Mattes J, Foster PS. Integrated signals between IL-13, IL-4, and IL-5 regulate airways hyperreactivity. J Immunol. 2000;165:108–113. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ren YF, Li H, Xing XH, Guan HS, Zhang BA, Chen CL, Zhang JH. Preliminary study on pathogenesis of bronchial asthma in children. Pediatr Res. 2015;77:506–510. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Schiffers C, Hristova M, Habibovic A, Dustin CM, Danyal K, Reynaert NL, Wouters EF, van der Vliet A. The transient receptor potential channel vanilloid 1 is critical in innate airway epithelial responses to protease allergens. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2020;63:198–208. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2019-0170OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Jing X, Yan W, Zeng H, Cheng W. Qingfei oral liquid alleviates airway hyperresponsiveness and mucus hypersecretion via TRPV1 signaling in RSV-infected asthmatic mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;128(110340) doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Satia I, Nagashima A, Usmani OS. Exploring the role of nerves in asthma; insights from the study of cough. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;179(113901) doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.113901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Zhang G, Lin R-L, Wiggers M, Snow DM, Lee L-Y. Altered expression of TRPV1 and sensitivity to capsaicin in pulmonary myelinated afferents following chronic airway inflammation in the rat. J Physiol. 2008;586:5771–5786. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.161042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Yocum GT, Chen J, Choi CH, Townsend EA, Zhang Y, Xu D, Fu XW, Sanderson MJ, Emala CW. Role of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 in the modulation of airway smooth muscle tone and calcium handling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2017;312:L812–L821. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00064.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Deering-Rice CE, Stockmann C, Romero EG, Lu Z, Shapiro D, Stone BL, Fassl B, Nkoy F, Uchida DA, Ward RM, et al. Characterization of transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1) variant activation by coal fly ash particles and associations with altered transient receptor potential ankyrin-1 (TRPA1) expression and asthma. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:24866–24879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.746156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]