Abstract

Objectives:

Cytolytic vaginosis is a very rare entity that may be clinically misdiagnosed as vulvovaginal candidiasis. The aim of this study was to determine the incidence of cytolytic vaginosis in patients displaying symptoms similar to vulvovaginal candidiasis and to develop a clinicopathological diagnostic and therapeutic approach.

Materials and Methods:

In total, 3000 cervical smear samples were evaluated at our center between 2015 and 2018. Patients whose PAP smears demonstrated significant epithelial cytolysis, naked nuclei, excessive increase in lactobacilli population, absent or minimal neutrophils and no microorganisms were subjected to a symptom assessment questionnaire and had their vaginal pHs measured. They were classified into two groups according to their complaints, symptoms and vaginal pHs: Cytolytic vaginosis and Asymptomatic intravaginal lactobacillus overgrowth. A standardized NaHCO3 Sitz bath therapy was applied to the cytolytic vaginosis group.

Results:

Fifty-three of the patients (1.7%) were diagnosed as cytolytic vaginosis. After Sitz bath therapy, there was a statistically significant decrease in the cytolysis and lactobacillus scores of the patients. Vaginal discharge of 43 (81%) patients ceased completely while that of the remaining 10 (19%) patients decreased after the therapy. The improvement was statistically significant (P < 0.001). There was a complete resolution in 28 (96%) patients with severe; and in 21 (94%) patients with intermediate vaginal discomfort, after the therapy. Dyspareunia was resolved in 35 (97%) patients (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Cytolytic vaginosis is a rare entity that can be diagnosed with the help of cytopathology and has a therapy based on the modulation microbiota by decreasing the vaginal pH.

Keywords: Bacterial, candidiasis, cytolytic vaginosis, lactobacillus, PAP smear, vulvovaginal

INTRODUCTION

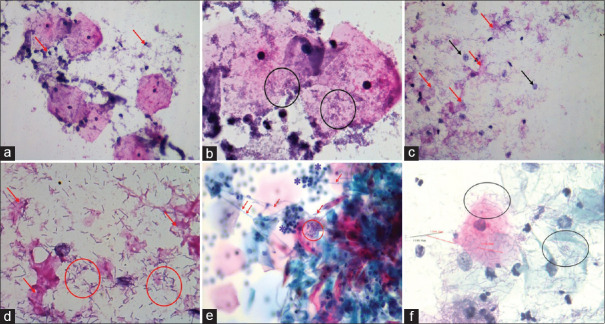

Vulvovaginal irritation and vaginal discharge are common complaints among gynecological patients that apply to outpatient clinics. The most common causes of vaginal discharge are bacterial vaginosis, candida infections and trichomoniasis.[1,2] Bacterial vaginosis is the most common cause of vaginal discharge among all etiological agents.[3,4,5] Vaginosis is a term which is used to describe the imbalance of normal vaginal microbiota. It is a distinct entity and should be differentiated from vaginitis.[6] In bacterial vaginosis, the smear is loaded with bacterial groups and sparse neutrophils [Figure 1a, b].

Figure 1.

The cytopathological features of bacterial vaginosis: a) Sparse neutrophil leucocytes in the background (arrows), (PAP, 400X). b) Bacterial accumulation (circles), (PAP, 1000X). c) Cytolytic vaginosis: marked cytolysis (red arrows) and bare nuclei (black arrows), (PAP, 400X). d) Abundant small lactobacilli measuring between 2 and 10 µm. (circles), (PAP, 1000X). e) Candida vulvovaginitis: Candidal hyphae (arrows), neutrophils (stars) and spores (circle). (PAP, 1000X). f) Lactobacillosis: Abundant lactobacilli with size longer than normal (circles). (PAP, 1000X)

On the other hand, cytolytic vaginosis (CV) is a rare disorder which mimics vaginitis, especially candidiasis, due to the similar patient complaints and symptoms such as white vaginal discharge, vulvar erythema, pruritus, dyspareunia and dysuria.[7] In patients with symptoms and signs of vaginal candidiasis unresponsive to antifungal medication, CV should be considered in the differential diagnosis.[2]

CV was first described by Cibley and Cibley in 1982. The authors stated that the symptoms of CV were similar to vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC). They realized that those were two different entities due to the differences in microscopic interpretation.[7] The main microscopic finding of CV was an overgrowth of lactobacilli, abundant naked nuclei together with disruption of the squamous epithelial cells and findings of cytolysis. In their study, Cibley and Cibley pointed out that the majority of the patients with a clinical impression of having chronic VVC had CV instead.[7]

Lactobacilli are the main microorganisms colonizing the vaginal microbiota of women of reproductive age. They produce hydrogen peroxide, lactic acid and bacteriocins which help to maintain the normal vaginal pH at acidic values between 3.8 and 4.2.[5] If lactobacilli decrease in number, the vaginal pH increases and an unfavorable environment is created for bacteria other than lactobacilli, resulting in an overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria. This results in an environment that predisposes the development of bacterial vaginosis.[5]

In a recent study conducted by Xu et al.,[8] explaining the pathophysiology of CV, the quantity of Lactobacillus crispatus was stated to be higher in patients with CV, while Lactobacillus sp. L-YJ was detected to be higher in healthy women. Beghini J, et al.,[9] detected different forms of lactic acid in patients with VVC, CV and bacterial vaginosis. In CV, symptoms increase in a cyclical manner in contrast to VVC. The symptoms are more prominent during the luteal phase. Cibley and Cibley determined the pathognomonic criteria of CV as increased number of lactobacilli, with epithelial cytolysis, lack of neutrophils, absence of microorganisms such as Trichomonas, Gardnerella, or Candida along with presence of a white vaginal discharge with a pH between 3.5 and 4.5.[7,10]

Treatment of CV entails raising the vaginal pH temporarily to basic values in order to decrease the excessive number of lactobacilli by using NaHCO3 douches or Sitz baths.[7]

The aim of the present study is to determine the incidence of CV and to establish a standardized NaHCO3 therapy regimen in Turkish gynecological patients, using a clinicopathological approach as well as emphasize the importance of this rare entity which may clinically mimic VVC.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

In this retrospective study, we evaluated 3000 cervical smear specimens of patients from two centers from 2015 to 2018. The smears were prepared by conventional manual PAP staining method.[11] Harris Hematoxylin (Bright-Slide, Istanbul, Turkey), Papanicolaou EA 50 solution (Bes-Lab, Ankara, Turkey), Orange G 6 solution (DDK, Vigevano, Italy) and 96% ethyl alcohol were used in PAP staining.

Patients whose cervical smears displayed marked epithelial cytolysis with prominent bare nuclei, prominent lactobacillus overgrowth and absent or minimal accompanying neutrophils, without pathognomonic findings of bacterial vaginosis, trichomonas vaginalis or candida infection were selected. We employed a similar scale that Spiegel, et al.[12] used in their study consisting of epithelial cytolysis rate, lactobacilli quantity, neutrophils, findings of bacterial vaginosis, candida hyphae and spores and trichomonas vaginalis and scored each variable from 0 to 3. All evaluations, were performed by a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ni-U microscope, Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) attached to a digital camera system including a micrometer scale (NiconDigitalSight DS-L3, Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at ×20 and ×40 magnifications by an experienced pathologist. In order to prevent investigator bias, suspended slides were consulted with experienced and impartial senior cytopathologists who were not included in the study. The patients whose lactobacilli and cytolysis scores were 2 and 3, neutrophil scores were 0 and 1, and bacterial vaginosis, candida hyphae and spore and trichomonas scores were 0, were clinically reevaluated with a symptom questionnaire. The symptomatic patients were included in the study. Asymptomatic patients were excluded. The gynecologist performed vaginal pH measurements, via pH sticks (ColorKim, Istanbul, Turkey). The symptomatic patients with vaginal pH ≤4.5 received a course of NaHCO3 Sitz bath therapy. One course of therapy included sitting in a solution consisting of one tablespoonsful of NaHCO3 dissolved in 4 L of lukewarm tap water every other 2 days, for 10 days.

Statistical analysis

Shapiro–Wilk test was used for assessing whether the variables follow normal distribution or not. Continuous variables were presented as median (minimum: maximum). Categorical variables were reported as n (%). Wilcoxon test was used in comparison between pre and post-operative values according to the normality test result. Categorical variables were compared between groups using the McNemar test. SPSS (IBM Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0, Armonk, New York: IBM) was used for statistical analysis and a value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All the patient informed consent statements for the participation in the study and publication for research purposes for the study exist in the patient files.

Ethical board approval date: 05/03/2018; approval number: 2018/3.

This study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

RESULTS

In the present study 2932 of 3000 randomly selected gynecologic patients' PAP smears were sufficient for evaluation (98%). PAP smears of 68 patients did not comply to sufficiency criteria of the Bethesda reporting system. Two of these cases did not contain enough numbers of squamous epithelial cells for evaluation and three of them had prominent fixation artifacts. Sixty three patients' cervical smears displayed marked epithelial cytolysis with prominent bare nuclei, lactobacillus overgrowth, absent or minimal neutrophils. The Bethesda diagnoses of the patients included 8 atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), (0.2%); 12 low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LGSIL), (0.4%) and 5 high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL), (0.17%), [Table 1]. Malignant diagnosis were not encountered.

Table 1.

Cytological characteristics of 3000 randomly selected PAP smears

| Total PAP smears | PAP smears sufficient for evaluation | PAP smears insufficient for evaluation | PAP smears with marked cytolysis, abundant lactobacilli, no/sparse neutrophils, no microorganism | PAP smears with ASCUS diagnoses | PAP smears with LGSIL diagnoses | PAP smears with HGSIL diagnoses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 3000 | 2932 | 68 | 63 | 8 | 12 | 5 |

PAP smears were reevaluated in terms of epithelial cytolysis, quantity of lactobacilli, and quantity of neutrophils. Each variable was scored using a “0 to 3” scale, [Table 2].

Table 2.

Cytological characteristics of the patients in re-evaluation of the PAP smears

| Score | Cytolysis | Neutrophil | Lactobacillus | Bacteria | Fungi hyphae & spores | Trichomonas vaginalis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 53 | 53 | 53 |

| 1 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 11 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 42 | 0 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

In the present study, we determined that 53 of the patients whose lactobacilli and cytolysis scores were 2 and 3, neutrophil scores were 0 and 1, and bacterial vaginosis, candida hyphae and spore and trichomonas scores were 0, had vulvovaginal symptoms whereas 10 patients were asymptomatic. Those patients were considered as having asymptomatic intravaginal lactobacillus overgrowth. The incidence of CV among 3000 gynecological patients was 1.7%. We determined that 43 (85%) CV patients had previously been treated with antifungal agents and had not responded to the therapy. After one course of NaHCO3 Sitz bath therapy there was a statistically significant improvement in the vaginal discharge status of the patients (P < 0.001). The discharge ended completely in 43 (81%) patients after the treatment. The discharge of 10 (19%) patients decreased after the treatment. There was a statistically significant improvement in the vulvovaginal discomfort status of the patients after treatment (P < 0.001). It was observed that 21 (94%) patients with moderate discomfort in the genital area did not have any discomfort after the treatment. In 96% of patients with severe discomfort (n = 28) the discomfort resolved completely after the treatment. There was a statistically significant improvement in patients with dyspareunia after the treatment (P < 0.001). It was observed that dyspareunia resolved in 36 (97%) of symptomatic patients after the treatment.

The ages of the symptomatic patients ranged between 18 and 57. Mean age of the patients was 35. All of the 53 patients had vaginal discharge. The color of the discharge was white in most of the patients (83%), (n = 44). After vaginal discharge, the most common symptom encountered pruritus (92.4%). Forty patients (75.4%) reported exacerbation of the symptoms during the premenstrual period. All of the patients' vaginal pH was <4.5. The detailed patient characteristics are demonstrated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of the patients according to the questionnaire

| Symptom | Patients (n) |

|---|---|

| White discharge | 44 (83%) |

| Yellow discharge | 5 (9%) |

| Clear discharge | 4 (8%) |

| Green discharge | 0 |

| Foul odor in the discharge | 4 (7.5%) |

| Pruritus on genital area | 49 (92.4%) |

| Dyspareunia | 38 (71.6%) |

| Dysura | 23 (43.3%) |

| Long term antibiotic usage | 0 |

| History of vaginal douche | 9 (16.9%) |

| Exacerbation of the symptoms during the premenstrual period | 40 (75.4%) |

| Vaginal pH <4.5 | 53 (100%) |

| Menopause | 7 (13.2%) |

| Pregnant | 3 (5,6%) |

| Puerpera | 3 (5.6%) |

DISCUSSION

Vaginal discharge is the most common complaint in the demographic encountered in gynecological practice.[13] Bacterial, candidal and/or parasitic infections comprise the most common etiological factors of vaginal discharge.[1,2] CV is a relatively rare cause of vaginal discharge. The clinical presentation is similar to VVC.[7,14] Five lactobacilli per 10 squamous cells are considered to represent the normal vaginal flora. While maintaining this number protects the vagina against candidiasis, increase in the number of lactobacilli may result in CV.[10]

The symptoms of CV are caused by the lactobacilli overgrowth. Although the lactobacilli overgrowth is of unknown etiology, chronic vulvar discomfort such as burning and itching are the common symptoms. Cibley and Cibley concluded that these symptoms may be related to excess lactic acid produced by the lactobacilli and the interaction between the byproducts from species of normal vaginal microbiota and different lactobacilli species.[7] In the present study, 18 (34%) patients had moderate, 35 (66%) patients had severe vulvar discomfort. A relationship was suggested between CV and patients with diabetes.[10] The diabetes status of the patients in the present study was unavailable.

CV can be identified based on the quantity of lactobacilli, the morphology of the epithelial cells, and the absence or presence of Candida species and other pathogens, [Figure 1c, d]. Misdiagnosis of VVC can be avoided with such an approach.[15] In a study of Suresh, et al.,[14] conducted with 1152 patients, the incidence of CV was determined to be 3.9%. In a study of Cerikcioglu et al.,[10] 7.1% of the patients who clinically presented with the symptoms of VVC were diagnosed as CV. Demirezen et al.[16] determined the incidence of CV as 1.83%, among 2947 patients with vulvovaginitis symptoms. In the present study the incidence of CV was determined to be 1.7% (n = 53), in accordance with the findings of Demirezen, et al.[16] The reason why the results of Cerikcioglu, et al.[10] were higher, compared with the literature might be because the authors selected a specific group of patients which only had vulvovaginal complaints mimicking candidiasis.

Cytopathological differential diagnosis include candida vaginitis, bacterial vaginosis, lactobacillosis, leptotrichosis, trichomonas vaginitis and actinomycosis.

As the symptoms of VVC mimic those of CV, it is crucial to exclude candidasis. In the previous studies, this exclusion was performed microbiologically.[7,15,16] In a study of Hillier, et al., the authors excluded candidiasis through the absence of candida yeast cells or leucocytes on Gram's stain.[17] In a study of Demirezen, et al.,[16] the diagnosis of CV was made based on cytological criteria such as bare nuclei, lactobacilli overgrowth and fragmented cytoplasm due to cytolysis.

In the present study, we used a cytopathological and clinical based approach to reach the diagnosis of CV. On PAP stained slides, we excluded the microbial etiologic factors causing vaginits by evaluating the neutrophil density, as well as detecting candida, trichomonas and bacterial vaginosis findings, cytomorphologically. Spiegel, et al.[12] used a scale for the patient evaluation in CV. The number of lactobacilli can be estimated by using the Spiegel scale of 0––4+ (none = 0, rare = 1+, few = 2+, moderate = 3+, many = 4+). We used a similar scale in the present study.

In candida infections, fungal hyphae and spores are visualized in PAP smears [Figure 1e]. There is a prominent neutrophilic inflammatory cell infiltration in candidiasis. Cytomorphological changes include nucleomegaly and occasional prominent nucleoli.

In the present study, we detected that both the squamous epithelial cells and the background were covered by abundant lactobacilli and bare nuclei due to the prominent lysis of the squamous cell cytoplasm [Figure 1c, d]. We conclude that especially if the lactobacilli population invading the epithelial cells are of smaller size, this may cause a diagnostic problem among inexperienced pathologists as they may be misdiagnosed as “clue cells” of the bacterial vaginosis. These cells are referred to as “false clue cells” in the literature.[14,16,18] We suggest that, upon detecting such cells, the cytopathologists should perform the interpretation on higher magnifications, i.e., 100x magnification. There is a clear line between the sizes of the bacteria causing bacterial vaginosis and CV. The microorganisms (G. vaginalis) causing bacterial vaginosis are small rods having average dimensions of 0.4 μm; ranging between 1.0–1.5 μm, whereas the size of the lactobacilli in asymptomatic women ranges between 5 and 15 μm.[19,20]

In lactobacillosis, extremely long lactobacilli are present in the vaginal wet mount preparations or cervicovaginal smears,[20] [Figure 1f]. A healthy woman normally has vaginal lactobacilli between 5 and 15 μm in length, whereas the lactobacilli in the symptomatic patients with lactobacillosis range from 40 to 75 μm in length.[21]

In the present study, the length of the lactobacilli, which were measured using a digital micrometer scale, ranged between 2 and 10 μm, and there was prominent cytolysis.

Leptotrichs are segmented, long, filamentous gram positive bacteria that may be associated with Trichomonas vaginalis infection. The length of the bacteria range between 10-20 μm (longer than lactobacilli). Loop formations may be seen in conventional smears. They tend to form clusters in liquid based preperations. Neutrophilic inflammation may be associated with leptotrichosis.[22,23]

The symptoms of Trichomonas vaginitis differ from that of CV in that foul smelling, greenish and thick vaginal discharge are the characteristic symptoms of Trichomonas vaginitis. Cytopathological features of trichomonas vaginitis include nucleomegaly, hyperchromasia, pseudocoilocytes (halo cells), cells without nuclei and with no accompanying cytolysis (ghost cells), cytoplasmic orangophylia, and neutrophilic inflammation in the background.[24]

Actinomyces are Gram-positive anaerobic or microaerophilic, filamentous bacteria. They are non-motile and they do not form spores. The bacteria are 1 μm in length and form cotton ball like clusters.[25,26]

There is no cytolysis in squamous epithelium in none of the diseases included in the differential diagnosis, above. Lactobacillus, which is the only abundant microorganism in CV, is the only species of bacteria that can cause cytolysis in cervicovaginal intermediate squamous epithelium by hydrolyzing cytoplasmic glycogen.[27]

Hills RL stated that women with CV may present with complaints of vulvovaginal itching and thick, white discharge whose severity increases during the lutheal phase, before the menstrual period. These patients might attempt treatment from multiple health care providers with various medications such as antifungals or metronidazole, without any improvement of symptoms. As the author pointed out, these women could even be referred to psychiatric counseling.[20] Starting an empiric treatment for vulvovaginal symptoms without considering the possibility of CV would be negligent. Since the clinical presentation of VVC and CV are similar, specific care should be taken to obtain an accurate diagnosis in patients with VVC-like symptoms.[15] In the present study we performed a detailed cytopathological PAP smear interpretation, measured the vaginal pHs of the suspected patients along with interpretation of a detailed patient questionnaire in order to obtain an accurate diagnosis of CV.

Despite recommendations by Centers for Disease Control and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, in routine gynecological practice, testing for vaginal infections is not widely used.[8] Clinicians generally use empirical, experience based therapeutic regimens while interpreting vulvovaginal complaints and symptoms of the outpatient clinic patients.

In conclusion, we wanted to emphasize that cytopathologists or pathologists should be aware that there is a rare disorder called CV and they should warn the clinicians that the patient might have CV when they see prominent epithelial cytolysis with marked bare nuclei and lactobacillus overgrowth and absent or minimal accompanying neutrophils, when examining PAP smears under the microscope. The clinicians should not start empirical antifungal therapy to patients that have complaints and symptoms similar to VVC and fail to respond long-term antifungal treatments before they take a detailed patient history and get the results of microbiologic wet mount/vaginal cultures or PAP smears. It should be kept in mind that there is a rare clinical entity called CV, which resembles VVC by means of clinical symptoms; and the patients' symptoms improve after one course of standardized NaHCO3 Sitz bath therapy.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Osset J, Garcia E, Bartolome RM, Andreu A. Role of lactobacillus as protector against vaginal candidiasis. Med Clin (Barc) 2001;22:285–8. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(01)72089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reis AJ. Treatment of vaginal infections: Candidiasis, bacterial vaginosis, and trichomoniasis. J Am Pharma Assoc (Wash) 1997;37:563–9. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)30241-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cullins VE, Dominguez L, Guberski T, Secor M, Wysocki SR. Treating vaginitis. Nurse Pract. 1999;24:46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmid GP. The epidemiology of bacterial vaginosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1999;67(Suppl 1):S17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(99)00133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mashburn J. Etiology, diagnosis, and management of vaginitis. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2006;51:423–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verstraelen H, Swidsinski A. The biofilm in bacterial vaginosis: Implications for epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment: 2018 update. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2019;32:38–42. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cibley J, Cibley J. Cytolytic vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:1245–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(12)90736-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu H, Zhang X, Yao W, Sun Y, Zhang Y. Characterization of the vaginal microbiome during cytolytic vaginosis using high-throughput sequencing. J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33:e22653. doi: 10.1002/jcla.22653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beghini J, Linhares IM, Giraldo PC, Ledger WJ, Witkin SS. Differential expression of lactic acid isomers, extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer, and matrix metalloproteinase-8 in vaginal fluid from women with vaginal disorders. BJOG. 2015;122:1580–5. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerikcioglu N, Beksac MS. Cytolytic vaginosis: Misdiagnosed as candidal vaginitis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2004;12:13–6. doi: 10.1080/10647440410001672139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raju K. Evaluation of PAP stain. Biomed Res Ther. 2016;3:490–500. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiegel CA, Amsel R, Holmes KK. Diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis by direct gram stain of vaginal fluid. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:170–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.1.170-177.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan SA, Amie F, Altaf S, Tanveer R. Evaluation of common organisms causing vaginal discharge. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2009;21:90–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suresh A, Rajesh A, Bhat RM, Rai Y. Cytolytic vaginosis: A review. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2009;30:48–50. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.55490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu Z, Zhou W, Mu L, Kuang L, Su M, Jiang Y. Identification of cytolytic vaginosis versus vulvovaginal candidiasis. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2015;19:152–5. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demirezen S. Cytolytic vaginosis: Examination of 2947 vaginal smears. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2003;11:23–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Klebanoff SJ, Eschenbach DA. The relationship of hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli to bacterial vaginosis and genital microflora in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:369–73. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turovskiy Y, Noll KS, Chikindas ML. The etiology of bacterial vaginosis. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;110:1105–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.04977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ventolini G, Schrader C, Mitchell E. Vaginal lactobacillosis. J Clin Gynecol Obstet. 2014;3:81–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hills RL. Cytolytic vaginosis and lactobacillosis.Consider these conditions with all vaginosis symptoms. Adv Nurse Pract. 2007;15:45–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korenek P, Britt R, Hawkins C. Differentiation of the vaginoses-bacterial vaginosis, lactobacillosis, and cytolytic vaginosis. Internet J Adv Nurs Pract. 2002;6:59. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bibbi M, Wilbur DC. Comprehensive Cytopathology. In: Bibbi M, Wilbur DC, editors. Supra gingival microbes. Philadelphia, U.S.A: Saunders Elsevier; 2008. pp. 103–5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mestrovic T, Profozic Z. Clinical and microbiological importance of Leptothrix vaginalis on Pap smear reports. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44:68–9. doi: 10.1002/dc.23385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cristophe Noel J, Aloghe CE. Morphologic criteria associated with trichomonas vaginalis in liquid-based cytology. Acta Cytol. 2010;54:582–6. doi: 10.1159/000325181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García-García A, Ramírez-Durán N, Sandoval-Trujillo H, Romero-Figueroa MS. Pelvic actinomycosis. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2017;2017:9428650. doi: 10.1155/2017/9428650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nissi R, Blanco Sequeiros RB, Lappi-Blanco E, Karjula H, Talvensaari-Mattila A. Large bowel obstruction in a young woman simulating a malignant neoplasm: A case report of actinomyces ınfection. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:756768. doi: 10.1155/2013/756768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng L, Botswick DG. Essentials of Anatomic Pathology. In: Cheng L, Botswick DG, editors. Gynecologic cytology. New York, USA: Springer; 2011. p. 13. [Google Scholar]