Abstract

Background

In Morocco’s health systems, reforms were accompanied by increased tensions among doctors, nurses and health managers, poor interprofessional collaboration and counterproductive power struggles. However, little attention has focused on the processes underlying these interprofessional conflicts and their nature. Here, we explored the perspective of health workers and managers in four Moroccan hospitals.

Methods

We adopted a multiple embedded case study design and conducted 68 interviews, 8 focus group discussions and 11 group discussions with doctors, nurses, administrators and health managers at different organisational levels. We analysed what health workers (doctors and nurses) and health managers said about their sources of power, perceived roles and relationships with other healthcare professions. For our iterative qualitative data analysis, we coded all data sources using NVivo V.11 software and carried out thematic analysis using the concepts of ‘negotiated order’ and the four worldviews. For context, we used historical analysis to trace the development of medical and nursing professions during the colonial and postcolonial eras in Morocco.

Results

Our findings highlight professional hierarchies that counterbalance the power of formal hierarchies. Interprofessional interactions in Moroccan hospitals are marked by conflicts, power struggles and daily negotiated orders that may not serve the best interests of patients. The results confirm the dominance of medical specialists occupying the top of the professional hierarchy pyramid, as perceived at all levels in the four hospitals. In addition, health managers, lacking institutional backing, resources and decision spaces, often must rely on soft power when dealing with health workers to ensure smooth collaboration in care.

Conclusion

The stratified order of care professions creates hierarchical professional boundaries in Moroccan hospitals, leading to partitioning of care and poor interprofessional collaboration. More attention should be placed on empowering health workers in delivering quality care by ensuring smooth interprofessional collaboration.

Keywords: health services research, qualitative study, hospital-based study, health systems

Key questions.

What is already known?

In hospitals, interprofessional interactions are characterised by conflicts, power struggles, medical dominance and daily negotiated orders that may not serve the best interests of patients.

What are the new findings?

Human resource shortages, poor working conditions and lack of institutional backing of and clarity around internal regulations all limit the decision space for health managers, who rely more on soft power than on formal hierarchy to do their work.

What do the new findings imply?

Reinforcing the role of clinical managers and empowering general practitioners and nurses to take responsibility for coordinating and integrating care may facilitate better integration and coordination of care in hospitals.

Background

Since 2000, health system reforms implemented in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) based on economic incentives (eg, performance-based financing) have generated tensions within the public sector between health workers’ market-driven values and the public service ethos and orientation of health systems.1–4 Most of these reforms, in the age of New Public Management (NPM), target public agencies and aim to foster competition and market-related values (results-based budgeting, contracting and public–private partnerships). This shift may have led to negative externalities such as gaming, goal displacement, corruption and interprofessional conflicts that hinder the quality of health service delivery.5–9 In LMICs, evidence points to increased tensions and power conflicts among members of different health professions because of marketisation of care and the rising expectations of patients, challenging interprofessional collaboration and negatively affecting quality of care.3 4 10

Since 2000, similar NPM reforms have been implemented in Morocco. They include hospital reforms, results-based budgetary reforms, contracting out, restructuring of hospital governance amid increased health needs (epidemiological transition, high burden of non-communicable diseases), growing urbanisation and fragmented health financing.11 12 These reforms aimed at strengthening local health system governance by institutionalising quality assurance programmes, establishing strategic hospital frameworks and performance-based budgeting and redesigning organisational structures.13–16 In Morocco, evidence indicates that these reforms were accompanied by increased tensions among doctors, nurses and health managers,1 17 low interprofessional collaboration and even power conflicts.18–21 Several implementation issues have arisen because of demotivation of health workers,17 22 lack of organisational learning,23 deviant health worker behaviours such as dual private practices and corruption.1 2 24 One factor was the rising discretionary power of unionised health workers (threatening negotiation walkouts, strikes, street protests, resistance to performance-based management), who gained concessions from the Moroccan government in terms of wages after the Arab Spring movement in 2011.2 25

In the field of health policy and system research,26 27 little attention has focused on power relationships among health professionals and managers.4 28 In Morocco, limited evidence is available to describe the nature and quality of interprofessional collaborations between doctors and nurses in hospitals. We set out to decipher the nature of these collaborations by using the theory of negotiated order29 and Mintzberg’s four worldview lenses.30 We specifically explored the perspectives of different health professionals (nurses, doctors, midwives, administrative staff) regarding interprofessional collaborations and power dynamics.

This work is part of a larger study exploring the relationships among leadership, motivation, performance and organisational culture.31–33 Here, we look specifically at the nature of interprofessional collaboration and conflicts from a dynamic, multilevel perspective, evaluating interactions among actors within the broader organisational, social and historical context of medical and nursing professions in Morocco.34–37

Theoretical background

Theories underlying interprofessional power conflicts in hospitals

The organisational sociology of professions provides insightful theories for explaining the nature of interprofessional power conflicts and negotiations that govern the daily practice of health professionals.38–42 Power relations between health professionals in hospitals are often described as being dominated by the medical profession.43 44 In hospitals, professions are organised into hierarchies, with medical specialists at the top, where power is pluralist (formal/informal, soft/hard, collaborative/competitive) and present in daily interprofessional relations.45–47

Strauss introduced the concept of ‘negotiated order’, which explains the constant consensus building and negotiation between interconnected professionals (doctors and nurses), in which each professional category tends to exert influence over the other, grounded in exchange and reciprocity. Both have something the other wants: for doctors, it is access to information from ward nurses, and for nurses, it is the prestige of having a close relationship with the doctors.40

The negotiated order is the consequence of both formal and informal negotiations between professions that traces to the increased specialisation of healthcare professions.40–43 48 The interactions between professional groups and professions play a crucial role in shaping power structures and negotiation processes in hospitals.41 42

Professional silos in hospitals

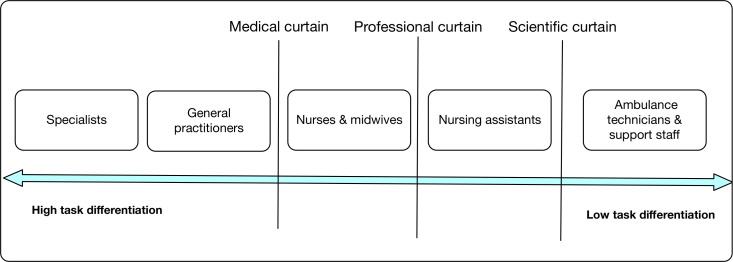

Hospitals are the archetype of professional bureaucracies.49 They are characterised by dual hierarchies: managers at the top holding formal authority over administrative staff but with limited control over the behaviours of professionals. They are also characterised by a multitude of professional partitions separating doctors from nurses and other caregivers.30 50 These interprofessional partitions create many professional silos (or chimneys) that fragment the health system and constrain horizontal integration of care and interprofessional collaboration30 50 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Professional silos (adapted from Glouberman and Mintzberg).30

Medical dominance

The medical profession is characterised by autonomous members who have formed professional structures (virtually hermetically) sealed by collegial bonds and separated from external members (nurses and administrative staff). This partitioning creates a sense of fellow feeling, a strong collective identity and solidarity among doctors that obliges them to support each other and act in the best interest of the medical profession.51 Doctors are organised into professional hierarchies in which seniority and clinical expertise and experience are highly valued. Physicians often resist an overcontrolling hospital administration, which explains why little social control is exerted over physicians.30 49 In contrast, nurses derive their power from their mediator role by connecting physicians to patients and their families. Nurses have more information about patients than physicians do and may use this information to leverage power in exchange for specific resources with doctors.29 52

Health workers’ divergent worldviews

Most studies that have explored how the NPM health system reforms have shaped power interplays and interprofessional collaboration were carried out in the Global North.53–56 In LMICs, including in Morocco, little evidence addresses the individual, organisational and contextual factors that explain interprofessional conflicts.3

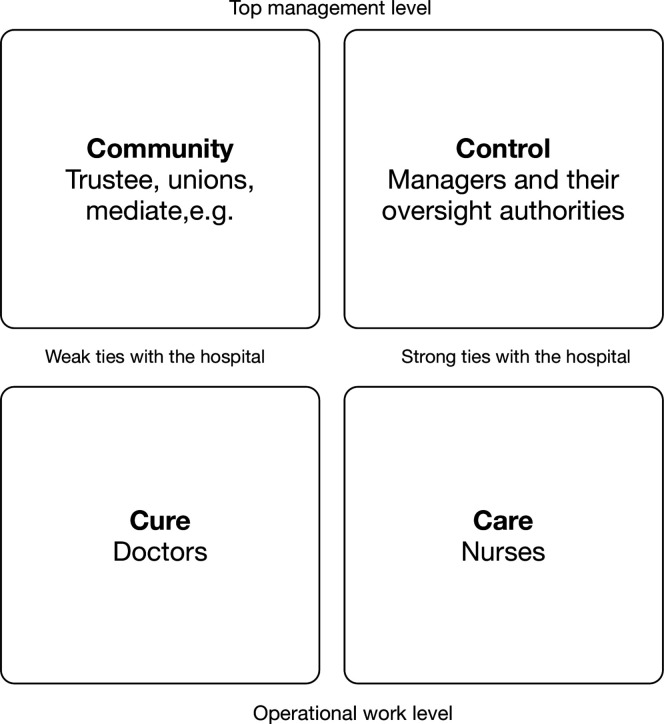

To understand the diversity of health worker perspectives, we used the Glouberman and Mintzberg framework as a heuristic tool to make sense of health worker worldviews and of managers in hospitals (figure 2). According to Glouberman and Mintzberg,30 there are four worldviews in hospitals: cure, care, control and community.30 50 The ‘cure worldview’ is held by doctors committed to treating specific diseases and to interventions that change the conditions of patients, such as caesarean section and medicine prescribing. They have little interest in administrative work. In contrast, nurses hold a ‘care worldview’ that values patient-centred care, and they spend most of their time with patients. A ‘control worldview’ is held by managers and their oversight authority who value control, stability and conformity with procedures. Finally, the ‘community worldview’ is held by the governing board, which holds managers accountable and exerts its power by constraining resource allocations. These boards are represented by boards of trustees, media and politicians.

Figure 2.

Four worldviews.

Brief overview of the Moroccan health system

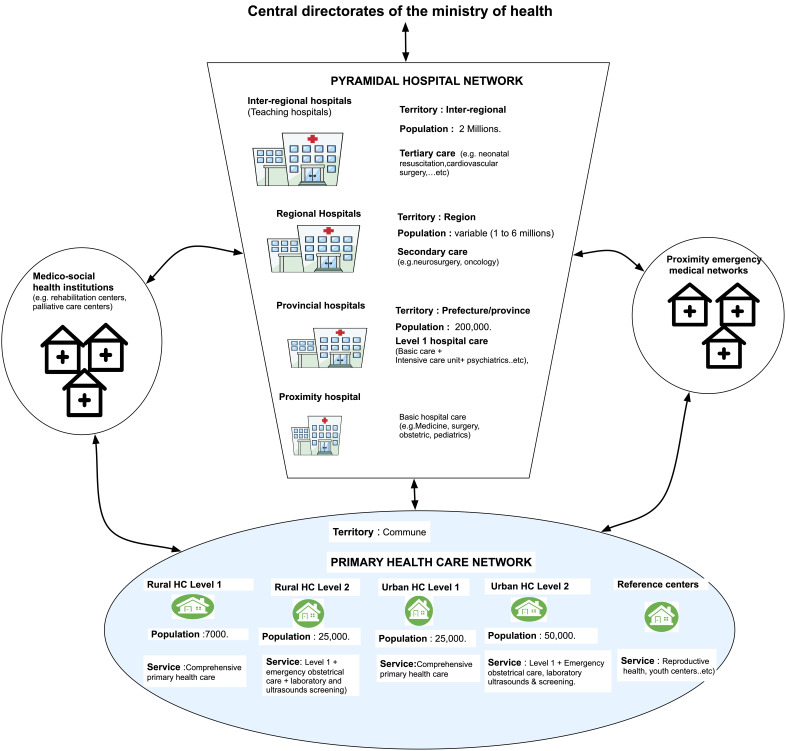

The Moroccan health system is organised into several interconnected healthcare networks in 12 health regions (figure 3). The networks include multiple interacting health actors within and across health districts (circonscription sanitaires), provinces and regions.33 57 The organisation of healthcare follows the administrative governmental deconcentration (12 regions and 82 provinces).

Figure 3.

The Moroccan health system. HC, healthcare.

Primary care is provided by primary care networks consisting of rural and urban healthcare centres in many health circonscriptions (or districts) (838 urban and 1274 rural). There are 12 264 habitants per primary healthcare centre, which provides supportive, preventive and curative care including maternal and neonatal health services.58

Secondary and tertiary care are provided by a pyramidal hospital network that comprises 149 hospitals including (semiautonomous) provincial and regional hospitals and inter-regional (fully autonomous) teaching hospitals with a total of 233 931 beds and 10 psychiatric hospitals with 1454 beds. In the public sector, there is a ratio of 1398 inhabitants per hospital bed. The private sector is highly developed with more than 10 346 beds (8355 medical specialists, 5190 general practitioners). The private and public sectors combined allow for adequate coverage of 993 habitants per hospital bed.

These main networks are interconnected by an emergency care network comprising local emergency units and prehospital emergency units (emergency medical regulation centres, reanimation and emergency services including medical air transportation), and medicosocial institutional networks that include non-acute care (eg, rehabilitation centres and nursing homes).

Methods

For this study, as noted, we sought to understand power dynamics that govern interprofessional collaboration in healthcare settings using the theory of negotiated order29 and Mintzberg’s four worldview lenses.30 More specifically, we compared doctors’ perspectives on interprofessional collaboration with the perspectives of nurses and health managers.

We used a multiple embedded case study design that takes into consideration the role of social and cultural context and allows for flexible exploration of various levels of analysis from the individual to the professional group to the organisational level.59 We also contextualised our findings through a historical analysis following previously published guidance60 61 to elucidate how nursing and medical professions were developed during the colonial and postcolonial eras in Morocco.

Case selection

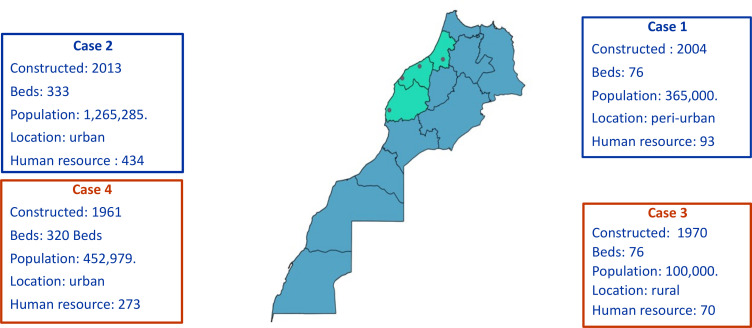

We selected four hospitals designated as EJMH, NHMH, RKMH and SMBA. Our choices were guided by the maximum variation among the study sites (eg, bed numbers, rural and urban areas, population of the catchment areas; figure 4).

Figure 4.

Case study selection.

Participant selection

We selected participants from different professional groups (doctors, nurses, support staff and administrators) and different healthcare units and managers from different organisational levels (senior, middle and operational levels) within the four hospitals. We purposely selected hospitals with contrasting organisational performance (ie, extreme case selection according to Patton62), as indicated by the national quality assurance programmes between 2011 and 2016.

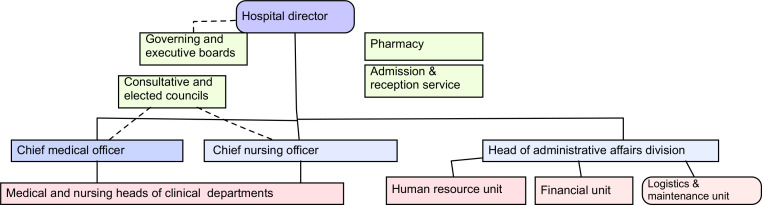

In this study, we posited that perspectives on interprofessional collaboration/conflicts and medical dominance would differ between different front-line health workers (doctors, nurses, administrators) and between clinicians and hybrid managers (health professionals filling additional managerial roles such as head of the medical department) (see box 1 and figure 5). To this end, we included participants from different organisational levels (strategic, eg, governing board; middle, eg, department head; and operational, eg, head of services) (see box 2).63

Box 1. Purposive participant selection.

Senior managers (executive board)

Hospital director.

Chief medical officer (CMO), ‘Chef des pôles des affaires médicales’.

Chief nursing officer (CNO), ‘Chef du pôle des soins infirmiers’.

Administrator, ‘Chef des pôles des affaires administratives’.

Middle managers (head of health departments/services)

Administrative department (‘Pôles des affaires administratives’ OR ‘admission service’): head of unit (human resource (HR) or financial unit).

Pharmacy: pharmacist in chief.

Medical department (ie, mother and child): doctor in charge and nurse in charge.

Surgical department (operating theatre or emergency department): doctor in charge and nurse in charge.

Operational staff

Administrative department: administrator.

Pharmacy: one pharmacist and one technical staff.

Medical department (eg, mother and child unit): one doctor and one nurse.

Operating theatre or emergency unit: one doctor and one nurse.

Figure 5.

Organigram of a Moroccan hospital.

Box 2. Role and responsibilities of health managers.

The hospital director or chief executive officer (CEO) is often a medical doctor. He has oversight authority on all hospital staff. He is responsible for strategic hospital planning and operational management (financial, technical and human resource management). He ensures the continuity of health service delivery, the implementation of central directives, policies, rules and procedures.

He is assisted by an executive board comprising the chief medical officer (CMO), the chief nursing officer (CNO), an administrator in charge of the administrative affairs division (AAD), the doctor in chief of the reception and admission service, the pharmacist in chief and two representatives of elected professional councils (nursing council and council of doctors, dentists and pharmacists). The CMO oversees the coordination of care, organisation of medical activities, resources and the continuing medical education. The CNO is in charge of the coordination of nursing staff planning, activities and continuing education. The administrator oversees the management of human resources, finances, accounting, logistics and support services.

At intermediate level, doctors in chief of department, assisted by nurses in chief, oversee respectively the coordination of medical and nursing activities as well as the coordination of care and management of department resources. At the operational level, each clinical service is managed by a medical doctor, assisted by a nurse in chief, who supervise and coordinate care within their respective span of control.

Data collection

First, we carried out four empirical case studies in the four hospitals using interviews, focus group discussions (FGD) and group discussions between 1 January and 30 June 2018 (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants

| NHMH | EJMH | RKMH | SMBA | |

| Managerial function | ||||

| Senior managers | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Middle managers | 3 | 7 | 2 | 5 |

| Line managers | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Operational staff | 20 | 30 | 17 | 33 |

| Total | 32 | 43 | 26 | 45 |

| Professional profile | ||||

| Doctors | 13 | 14 | 4 | 14 |

| Pharmacists | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Nurses | 14 | 15 | 14 | 20 |

| Administrators | 4 | 11 | 7 | 10 |

| Total | 32 | 43 | 26 | 45 |

| Age category | ||||

| 20–30 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| 31–40 | 11 | 11 | 6 | 17 |

| 41–50 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 11 |

| 51–63 | 6 | 19 | 6 | 14 |

| Total | 32 | 43 | 26 | 45 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 20 | 25 | 10 | 24 |

| Male | 12 | 18 | 15 | 21 |

| Total | 32 | 43 | 26 | 45 |

Interviews

In total, we conducted 68 face-to-face interviews until saturation was reached: 17 at EJMH, 18 at NHMH, 16 at RKMH and 17 at SMBA. The average duration of interviews was 40 min. We followed guidance on qualitative interviewing from Rubin and Rubin regarding, for example, structure, conversational partnerships, follow-up questions and probes.64

Group discussions

We conducted eight FGDs following guidance from Krueger and Casey.65 When the required number of six to eight members for an FGD was not reached, we instead conducted 11 group discussions with a limited number of participants from different professional profiles (doctors, administrators, nurses).

Interviews and FGD guides, pretested in pilot hospital study, are presented in online supplemental files 2 and 3. All interviews, group discussions and FGDs were audio recorded and transcribed at the exception of one interview. In this specific case, the first author took notes and used memory recall at the end of the interview.64 Respondent sociodemographic characteristics are detailed in online supplemental files 4–7. At the end of each interaction, we summarised key themes following guidance from Miles et al66 in field notes. At the time of data collection, the interviewer had a training as a medical doctor in public health, and in public management with an experience as a former hospital manager. This allowed in-depth experiential knowledge about local hospital settings, quick connection with respondents and more in-depth details from interviewees.

bmjgh-2021-006140supp002.pdf (50.4KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-006140supp003.pdf (64.3KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-006140supp004.pdf (44.8KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-006140supp005.pdf (52.4KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-006140supp006.pdf (45KB, pdf)

bmjgh-2021-006140supp007.pdf (48.3KB, pdf)

In a second phase, we conducted a narrative literature review including contextual analysis, and historical analysis of regulation and legislation related to the development of the nursing and medical professions during the colonial (1912–1956) and postcolonial eras.

Data analysis

We first analysed the reasoning, perspectives and meanings attributed to health workers in the four case studies about their perceived roles, sources of power and relationships with other healthcare professions. For our purposes, we adopted the cyclic iterative process described by Yin67 including compilation, interpretation, discussion and drawing conclusions. All data sources were coded using concept and NVivo coding68 and the data managed with NVivo V.10 software.69 We conducted a thematic analysis according to the concept and theories described above. Online supplemental file 8 presents the codes and their frequency as expressed by health managers and health workers.

bmjgh-2021-006140supp008.pdf (47.5KB, pdf)

Next, we carried out a historical analysis as a lens for making sense of the major patterns underlying the emergence of nursing and medical professions in Morocco. Following guidance from Mahoney and Rueschemeyer,61 we used document analysis and review of legal regulations and historical documents to unravel the processes that may underlie how nursing and medical professions emerged during the colonial and postcolonial eras in Morocco and how they may explain our empirical findings.

Results

In the next section, we present how health workers (doctors and nurses) and health managers (hospital directors and clinical managers) described power dynamics underlying their interprofessional collaborations. We start with the history of medical and nursing professions in Morocco that allows better understanding the power interplays among nurses, doctors and the health administration.

History of medical and nursing professions in Morocco

Before independence

The professionalisation of Western medicine in Morocco was initiated during the French Protectorate (1912–1956) after the decline of eastern medicine in the 19th century (Al-Qaraouine University in Fes stopped teaching medicine in 1893). Medicine was primarily practised by French military doctors in regional and provincial hospitals or in their own private practices. Their practice was regulated by a ‘French’ college of physicians created in 1941.70 Medicine was taught only to French colonial students in a medical school in Casablanca.71

Nursing education was based on practice, learning on the job, 6-month internships in regional hospitals and mentorship from French physicians. Trainees graduated as ‘Adjoints Spécialistes de la santé’ or ‘registered nurses’ in diversified nursing disciplines (prenatal and early childcare, pharmacy, surgery, electroradiology, biology, biochemistry, hygiene and preventive medicine, maternal delivery, medicine, ophthalmology, microbiology, serology and haematology, social medicine and psychiatry) (Arrété viziriel du 5 October 1913).72

Later, in 1941, formal nursing education began with the creation of a French school of nursing and social assistants in Casablanca. A nursing diploma was conferred, called the ‘Diplome d’Etat Francais d’Infirmières Hospitalières’, and accredited by the French authorities. In 1944, the colonial administration created nursing schools for Muslims in Casablanca, the ‘Ecole d’auxiliaires médico-sociales Musulmanes’, which conferred a diploma that was considered less prestigious and produced general practice nurses (nursing assistants and registered nurses) (‘Infirmier Breveté’ or ‘Mommarida’).

After independence in 1956

In 1956, Morocco had only 55 doctors.71 To address the acute shortage in nurses and medical staff, the Moroccan government has implemented successive educational reforms since an initial national health conference in 1959.71 73 74 These reforms comprised the creation of faculties of medicines (1962 in Rabat, 1975 in Casablanca).

Medical training lasted 7 years and produced about 400 medical students a year. In late 1990, new educational reforms were implemented aimed at training 3000 doctors annually by extending the staffing and student capacities of existing faculties and creating new ones in different locations (Marrakech and Fes in 1999, Oujda in 2008, Agadir in 2016, Tangier in 2017).75 However, in 2018, more than 5800 Moroccan doctors immigrated to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries.76 In addition, in 2021, there is an increased mobility of medical doctors from the public sector to the private sector. Evidence supports also that despite the legal prohibition of dual practice in Morocco,77 it is still common and mostly unregulated.78

During the period between 1956 and 1973, reforms were aimed at extending the number of nursing schools in various locations to address the acute shortage of nurses. In 1973, a new nursing educational reform was implemented to enhance the quality of nursing training. Nurses graduated as qualified registered nurses, or ‘infirmier diplômé d’état’. This diploma was accredited by the Ministry of Higher Education only in 2013, however. Online supplemental file 1 summarises the major historical development of the professions of medicine and nursing in Morocco during the colonial and postcolonial eras.

bmjgh-2021-006140supp001.pdf (80.4KB, pdf)

In the next section, we present the perspectives of health workers on medical dominance in hospitals as expressed by health workers and managers in the four case studies.

Professional hierarchies

According to physicians interviewed in the four hospitals, doctors represent the tip of the professional hierarchy pyramid in hospitals. Respondents emphasise the importance of professional values by expressing their strong commitment to their professional ethos and strong collegial bonds, with limited ties to formal hospital administration. This relationship can be seen from outside the collegial bonds among the physicians, as this pharmacist (EJMH 25) describes:

In this hospital, similarly to all public hospitals, doctors do not consider the administration as a friend. They are often against it. The administration is their enemy. Honestly speaking, they do not facilitate the task for hospital managers. Implementing change in health units and throughout the hospital is really challenging for the director.

At work, the doctors strongly rely on teamwork, collegiality and maintaining a good relationship with medical colleagues or ‘confrères’ to meet patient needs. This professional allegiance is used to counterbalance the decisions of hospital directors, such as establishing an obligation to increase occupation rates and end external consultations in inpatient departments. The doctors achieve their allegiance through ‘coping strategies’,4 such as over-referral of patients (ie, referring patients to other hospitals when it is not necessary), absenteeism and strikes.

Clinical managers (ie, doctors who have managerial tasks in addition to their clinical duties) are more respected by their medical colleagues than formal administrators because of the solidarity among the clinicians. According to one clinical manager, hybrid managers play an important role in reducing professional resistance and ensuring compliance with organisational policies, such as activity transfer of the operating theatre from an old to a new hospital location.

The head of a surgical department (EJMH 13) asserts that his influence over physicians stems from respecting professional boundaries, his sense of collegiality and his aim to protect the interests of the medical community. An example is averting potential litigation from unsatisfied patients by teaching new surgeons how to convince patients or their families to sign medical waivers. This respondent says:

Hierarchical authority does not exist in the coordination of care between doctors in public hospital settings. The relationship between doctors is governed by mutual respect and friendliness. […] In general, heads of units have no formal authority over doctors, in contrast with the authority they hold over nurses. We [clinical managers] are considered by doctors as a confrère [colleague] with additional administrative tasks. We are never considered as a hierarchy.

In EJMH, a medical head of department was highly respected for his clinical expertise and professional seniority and his role as a member of the regional order of physicians (researcher note 17 January 2018). As this pharmacist (EJMH 25) reports:

In this hospital, there is a second director [referring to the medical head of the mother and child department] highly respected by doctors. A specific set of rules governs the relationship between clinicians, the head of the department, and the formal administration. They constrain and force hospital managers to get their things done their way. They appointed among them a leader on the basis of his knowledge and seniority. He was so influential that the director could not convince surgeons to replace their old surgical instruments with new sets. No one could force the surgeons to use the new sets!!! Even though this altered the quality of the sterilisation process with old boxes, non-adapted to the autoclave (the boxes remained opened). In this case, the administration could not make the necessary changes.

Respondents, regardless of their professional profile (specialist, hybrid manager or administrator), consider that interprofessional collaboration is ensured through consensus building and constant negotiation and not through formal authority flows. Hybrid managers and administrators were obliged to rely on soft power dynamics and continuous negotiation to ensure adequate coordination of care.

According to one general practitioner head of a department (NHMH 31):

It is not easy for me as a general practitioner to supervise specialists’ activities at the outpatient department. In the beginning, they were resistant. It was difficult to build a trust relationship. By getting to know them more closely and by working with them, I managed to understand their needs and tried to resolve organisational issues. We succeeded in working as a team. Managing this medical department is about teamwork…. We are constantly looking to find consensus and agreed-upon solutions in planning our clinical consultation agenda. Coordination between doctors is about respecting their opinions and trying to find an agreed-upon solution for all.

A general administrator (EJMH 8) also speaks of their specialised role in the care of collaborations:

By allocating the adequate material to specialists, there were no further power struggles, (and) dominance related to the use of the equitable use of surgery rooms at the operating theatre by different surgeons. Things are getting smoother after the interprofessional commissions (commissions including head of department and frontline workers) were created. This has eased the conflicts between surgeons and heads of departments, we (managers) could only play a palliative role and not a curative role in dealing with professionals.

Why soft power is better in dealing with physicians

Our analysis shows that to alleviate the power of physician expertise, hybrid managers use their personal informal relationships, mutual adjustment (replacing doctors in their shifts and expecting them to do the same) and consensus building to ensure a smooth continuity of care and comprehensive patient-centred care. This strategy explains why clinical managers emphasise participative decision-making, task delegation and collegiality among doctors, as this surgeon and chief of clinical services (NHMH 11) does:

I am close to the personnel; I have an accessible management style. I try to be close to physicians, I try not to create tensions, and they listen to me a bit. I try to understand their specific needs.

They argue that informal personal relationships are more effective than managerial control to gain trust of colleagues and get work done. This trust is based on expected social exchange and reciprocity from colleagues. They use ‘smart power’45 by gaining the trust of health workers rather than exerting authority, which is often ineffective because of the lack of institutional backing, as occurs when a chief executive officer (CEO) cannot apply regulations and procedures out of fear from unions and because of their limited decision space in terms of sanctions and disciplinary actions. From another surgeon and head of a department (EJMH 13):

Doctors may leave patients in the reanimation service for days. I cannot reprimand them, otherwise they will react aggressively, and they will fight back. They often agree to comply when I tell them gently to take care of patients.

In addition to weak institutional backing, hospital CEOs also lack managerial decision space. Their legitimate power is supported by hospital legislation and organisational decree that CEOs have authority over all personnel.63 79 Yet this power is limited because of the inability of hospital directors in the Moroccan context to mobilise additional resources or carry out disciplinary actions against their staff. These functions are centralised at the central and regional levels. In the Moroccan context, despite multiple accountability mechanisms, such as a web form and phone number for complaints and clinical audits, CEOs have insufficient power to sanction health professionals at the local level unless the central and regional authorities trigger the disciplinary actions.

According to one CEO (EJMH 7):

Hospital directors do not have sufficient power in managing staff. They do not have sufficient resources to motivate staff. They do not have the power to sanction deviant behaviours. To give you an example, I have two medical specialists, one of them is highly productive, the other is just doing the minimum required tasks. I am not able to motivate the well-performing specialist. They both have the same salary and the same career opportunities in the public sector!

This lack of decision space is also explained by the lack of clarity in internal regulations and ambiguity in terms of role clarity and attribution (ie, division of responsibilities). According to the head of a financial unit (EJMH 3):

Regulations of institutionalised administrative permanence (shift carried by managerial teams in off duty hours…) did not provide specifications about who will be doing the shift. Do administrative shifts mean a shift by an administrative staff? Or by chief nursing officers who carry out administrative functions? What does administrative permanence mean? Which tasks should be carried out? These arguments were discussed by administrative staff. They also claimed that there is no compensation for this extra amount of work.

Specialists setting the rules of the game

Specialist doctors regulate their own consultation scheduling and weekly amount of work in the hospital. The administration does not set the daily consultation rate. The physicians dictate to the administration the maximum number of consultations they will do 1 day/week, with a maximum of 12 weekly. They also avoid managerial meeting (researcher notes 16 and 17).

According to the head of a financial unit (SMBA 36):

Appointments are given directly by physicians and not by the admission and reception service. Physicians also set the maximum number of consultations (12 to 15 consultations a week).

We observed during our fieldwork that physicians came to the hospital at their own convenience to do rounds individually with the available nurse. Hence, nurses derive power from their knowledge about patients in the hospital ward. No staff meetings are held. We also observed that specialists seldom participated in multidisciplinary meetings. In EJMH, for instance, specialists were not present in at least two meetings despite having been invited by the CEO.

According to interviewees (a hospital pharmacist and a hospital administrator), physicians also can counterbalance the power of the hospital CEO by thwarting formal administrative procedures. As the pharmacist puts it (EJMH 25):

What could the administration do against the surgeons in this case [surgeon reluctance to replace old surgical instruments with the new set]? Sending an complaint letter is useless!!! Doctors will eloquently respond to it!! The administration has a limited say in surgeons’ decisions. Their technical knowledge allows them to self-endorse their decisions or even exert counterproductive pressures on the director. They could deliberately send two unsatisfied patients to the director’s office. He will be then occupied for the rest of the morning.

Nursing professional hierarchy

We found that the context of the nursing profession in Morocco is characterised by the dominance of a strong nursing identity as well as an acceptance of the hospital hierarchies. Nurses have a strong collective identity, an ‘esprit de corps’. According to a nurse and team leader from an emergency department (EJMH 43):

During shifts, we work as a team with simplicity, personal relationships, and kindness. We communicate about problems. When I notice that something is wrong, I do not shout at my team members. People do not like to be brutalised. If someone is tired, he is replaced by another. The nursing tasks flow smoothly. If I start shouting at them, there will be no respect, and work will not be done.

Nurses were also organised into a nursing hierarchy. Front-line nurses and midwives accept direct supervision from nurses in charge of clinical units. The nursing hierarchical line was perceived as useful in organising workflows and clarifying roles and reducing workload. According to a chief nursing officer (EJMH 1):

We designed for each nursing team a team leader. He is responsible for drug and material distribution during day and night shifts and during the weekends or holidays. The departing team passes on the instructions to the team leader, who verifies and notifies the reception of material, drugs, and medical instructions.

However, although they complied with the hospital authorities, nurses held discretionary power. The acute shortage of nurses constrains the power of managers to sanction absenteeism because it is difficult to replace nursing staff. According to a nurse in chief of an emergency department (SMBA 17):

I tolerate that some nurses come late. I could not exercise my authority over them and send complaint letters. The administrative procedure takes time! Meanwhile, nurses might send a medical certificate that covers their absence. I will then be obliged to look for replacements for their shifts. I prefer to replace them for 20 minutes or more rather than reprimanding them for being late.

Because of the acute shortage of nurses, managers’ authority is constrained related to human resource management. CEOs could not oblige nurses to come to work outside of formal working hours and prefer to negotiate and seek compromises with nurses to fill the acute shortage, according to one hospital CEO (EJMH 7):

[…]Another daily challenge is the human resource shortage. For example, a nurse in a shift could not come to work and handed to the administration a medical certificate during the weekend. I have no administrative authority to bring extra nurses to fill this position. I just rely on my personal relationship with them. He [the requested replacement] could accept by expressing that he appreciated helping me because of my individual consideration. On the other hand, he could also refuse to come, and I have no authority to force him because he had already worked during his shifts according to work schedule.

Divergent perspectives between doctors and nurses

All nurse interviewees expressed the need for mutual respect and adjustment and reduced status difference with doctors as a way to facilitate care coordination. According to a nurse in chief of a clinical department (EJMH 12):

In my opinion, the relationship between doctors, nurses, and administrators needs to be fluid. We are all complementary. Doctors could not work without us and vice versa. Before, nurses carried out physiotherapy for inpatients without a formal prescription from doctors. They adjusted mutually. Now, junior nurses are not willing to carry out these tasks without a formal written prescription from doctors and approval from their nurse in chief. This has created barriers to the fluid coordination of care. This explains the actual tense climate between nurses and doctors. (FGD, nurses)

In contrast, doctors considered that setting professional boundaries is essential for ensuring mutual respect. They expressed that the job of nurses is to follow medical instructions, as this surgeon (EJMH 13) asserts:

A status difference between doctors and nurses is essential to the natural equilibrium. It has to be built on respect. Nurses should always talk to doctors with respect. I am talking here from the nurses’ standpoint. If this respect is lost, the professional barrier between nurses and doctors is withdrawn!

This divergent perspective and lack of common understanding of interprofessional collaboration has led to increased bargaining between nurses and doctors, as this surgeon describes:

Now, nurses start calling doctors by their first names. Physicians could not give instructions anymore. Respect is lost. Nurses start negotiating in applying medical instructions. In this specific case, asserting excessive control techniques will not serve physicians’ best interests.

Nurses engage in bargaining with doctors because they are unable to negotiate institutionally regarding inadequate staffing and suboptimal working conditions, as this nurse (EJMH 35) says:

In my opinion, our relationships with doctors and supervisors are friendly, we can discuss, communicate without problems. They could not anymore interfere with our nursing practices because the necessary working conditions are not met and because there are no specific nursing occupational regulations. If doctors start overcontrolling our practices, this will lead them to failure. (FGD, nurses)

Discussion

Our study findings confirmed the dominance of medical specialists occupying the tip of the professional pyramid. Our study showed, in line with others,56 80–84 that physicians can impose their own work schedules on hospital managers and divert from the hierarchical line to serve the interests of their medical community by reinforcing their professional autonomy within the enclaves of their clinical departments.

Our study also shows the existence of professional hierarchies50 that counterbalance the power of formal hierarchies.49 85 86 This is in line with the role of professional identities in settings with multiple professional silos, transforming the hospital into a highly compartmentalised structure (pigeonholing).15 87 This medical professional hierarchy and compartmentalisation of care reflect the notion of a professional hierarchy.41 42

These professional boundaries are explained by the existence of a stratified order in care professions (eg, specialists vs generalists, surgeons vs medical specialists, doctors vs nurses).29 88 89 These social boundaries or ‘professional partitionings’ are based on the level of expertise, clinical seniority and shared norms and values.88 They lead to observed instances of social closures, as described by Weber,90 which refers to a form of social stratification relying on the exclusion of individuals from professional groups formed based on educational credentials indicating competency.50 80 88 89 91

Our study also highlights the contradicting and contrasting perspectives of nurses and doctors. This diversity of professional worldviews can be traced back to the socialisation process in medical and nursing schools.92 Waring and Currie asserted that ‘Professional groups produce strong social and cognitive boundaries that provide a cultural and institutional framework within which clinical performance is interpreted and enacted at a local level’.82

In Morocco, the socialisation process of doctors could be traced to medical education reforms after independence in 1956 and in 1997 and in 2015.93 94 These reforms strongly influenced the professional socialisation of doctors by extending the duration of medical studies to 7 years, establishing multiple medical and surgical specialisations and extending the role played by the national order of physicians in regulating the deontology of the medical profession95–98 (see online supplemental file 1).

In line with other studies,4 30 49 99 we also found that there are many rifts between doctors and nurses. Previous authors29 38 52 have asserted that nurses may turn to other sources of power to counterbalance the medical professional hierarchy either by monopolising ward information or by engaging in coping strategies (strikes, absenteeism), with negative consequences for patient-centred care.50 100 101

The divide between nursing and medical education could be explained in the Moroccan context by an education programme that remained unstructured and informal until 1973 and produced less qualified nursing assistants or ‘infirmier breveté’. Only later, during 1973–1993, was the duration of nursing studies extended to 3 years in newly created nursing institutes, ‘Institut de formation aux carrières de santé’.102 This contrast between medical and nursing professional development and the insufficient adaptation of nursing regulations may explain the medical dominance. To date, no college of nurses has been created, and regulations place the nursing profession under the tutelage of physicians.103

These interprofessional conflicts explain the power struggles in the daily delivery of care in hospitals.85 104 Such power struggles are essential to ensure better adaptation to complex clinical challenges41 43 81 and smooth interprofessional cooperation.44 105 However, the lack of managerial control may lead to deviant behaviours that can alter the public service and professional ethos and favour maximisation of self-interest by establishing informal rules governing these behaviours.29 85 106–108 In Morocco, this lack of managerial control, similar to other North African countries,109 stems from the semiautonomous statute of hospitals and the subsequent limited decision spaces of managers in terms of human resources management and additional resource mobilisation.14 Health managers are also facing pre-existing structural challenges such as the acute shortage and demotivation of physicians due to lack of career development opportunities, poor working conditions and unsatisfactory remuneration in the public sector.17 22 78

According to Strauss, these negotiated orders in hospitals and in healthcare in general are shaped by the divergent values, stakes, legitimacy and goals among the actors and the complexity of the negotiation issue.110 Structural factors also bind them, including resource availability (eg, an acute nurse shortage), organisational capability (in our case, lack of institutional backing and inability to improve working conditions), medical dominance and power, the subspecialisation of care professions and the division of labour.40 101 110

Both doctors and nurses are constantly negotiating with health service managers for the required resources to carry out their jobs. This situation, with a focus on control, positions the health administration as a ‘patronage profession’ that derives its power from controlling the resources that health practitioners require to do their work.41 Health workers counterbalance managerial power by bypassing rules and regulations or limiting access of patients to care (eg, limiting the number of consultations per day) or by engaging with the community or adopting negative work attitudes (absenteeism, dysfunctional patient–provider interactions).4 The result is a top management that fears the loss of control and introduces new rules, which in turn leads to a top-heavy bureaucratic and ineffective healthcare organisation structure.38 46

This process also explains why health managers in our study often relied on ‘soft power’45 to deal with physicians and nurses, bringing attention to the importance of clinical managers (physicians with managerial duties) who connect the dots between the formal hierarchy and front-line health workers.111–114 Clinical managers or professional elites hold considerable power, legitimacy and control over clinical department resources (staff, material). Their allegiance is oriented towards collegiality and the notion of solidarity within each professional category, as described previously.56 81 82 88 89 99

We also found indications that unions play a major role in building internal alliances, counterbalancing the authority of formal hierarchy. In Morocco, physicians are allied in a union of physicians who work in the public sector (Syndicat independant des Médecins du Secteur Public). Nurses are organised into professional associations (midwives) and coordinating committees within various public administration labour unions.

This study has some limitations. The historical analysis was limited by the available relevant historical data and the time constraints of our study (part of a PhD study). We acknowledge that we did not explore the perspective of hospital oversight authority such as provincial and regional health officers, and central directors. However, this study focused in particular on the everyday politics that are essential to explain what constrain health policy implementation at local levels.115

We acknowledge the methodological issues in the retrospective study of historical accounts. Our findings, as in all retrospective research, might be affected by recall bias.116 By validating our findings against different data sources (individual interviews, historical documents, regulations, FGDs, human resource archives), we improved the accuracy of the information collected.

In this work, the multiple embedded case study design proved appropriate for allowing the theoretical replication, described previously,59 of both the negotiated order theory29 and the four worldviews30 in four Moroccan hospitals.

Future research might explore the use of other theories (principal agent theories, transaction cost theories, shadow hierarchy) to explain the interlinkage between top-down implementation of health policies, power dynamics and the interprofessional collaboration at local levels.117

Conclusion

Effective hospital managers need to understand the nature of these negotiated orders and how they influence daily coordination of care.118 119 They also need to overcome professional boundaries by promoting open communication and prohibiting deviant behaviours that negatively affect quality of care. Managers should also incentivise teamwork and interprofessional collaboration by reducing status differences between different groups of health providers (eg, quality circles).112 120–123

Attention should be placed on the empowerment of general practitioners and nurses to take responsibility for coordinating and integrating care from a patient-centred perspective.124 This step would allow for better integration of care by producing flat horizontal, hub-like coordination systems.50

We stress that top-down hierarchical control and performance management reforms that have been implemented are poorly adapted to the nature of professional bureaucracies in which health workers hold other informal sources of power that best serve their interests.29 In response, policymakers need to decentralise key human resource functions at the hospital level and transform hospitals to autonomous entities ‘Etablissement Public de Santé’.109 More attention should also be paid to the promotion of professional public service values by reforming medical and nursing education around patient-centred care and the development of social accountability mechanisms.125

In summary, health managers need to adapt their leadership practices to fit the needs of each specific professional category by: (1) reducing status differences and empowering general practitioners and nurses; (2) involving doctors and specialists in participatory decision-making and providing them with the necessary resources to experience their self-efficacy and autonomy as related to their psychological needs; (3) walking the talk and showing individual consideration for administrators and direct supervision for low-level cadres; and (4) carefully selecting hybrid managers to better serve the public interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants from the four hospitals for their willingness to participate in the study. We are thankful to the anonymous reviewers for their the insightful comments.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @drbelrhiti

Contributors: All three authors contributed to the original design and analysis and writing of the manuscript. ZB carried out the data collection. SVB and BC revised the different versions of the manuscript. ZB edited the final draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The PhD work of which this study is a part was funded through a PhD framework agreement between the Belgian Directorate-General for Development Cooperation and the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable as no data sets were generated and/or analysed for this study.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The research protocol was approved by the Moroccan Institutional Review Board (No 90/16) of the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Rabat, and the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp (No 1204/17). All participants were informed prior to the conduct of the research, and written consent forms were signed by the respondents and countersigned by the researcher. A signed copy was given to each respondent.

References

- 1.Cohen S. The politics of social action in Morocco. Middle East - Topics & Arguments 2014;2:74–82. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Errami Y, Cargnello CE. The pertinence of new public management in a developing country: the healthcare system in Morocco. Can J Adm Sci 2018;35:304–12. 10.1002/cjas.1417 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badejo O, Sagay H, Abimbola S, et al. Confronting power in low places: historical analysis of medical dominance and role-boundary negotiation between health professions in Nigeria. BMJ Global Health 2020;5:e003349. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilson L, Schneider H, Orgill M. Practice and power: a review and interpretive synthesis focused on the exercise of discretionary power in policy implementation by front-line providers and managers. Health Policy Plan 2014;29:iii51–69. 10.1093/heapol/czu098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denhardt K. Enhancing ethics in the public service: setting standards and defining values. Public Service in Transition 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denhardt RB, Denhardt JV. The new public service: serving rather than steering. Public Adm Rev 2000;60:549–59. 10.1111/0033-3352.00117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turcotte-Tremblay A-M, Gali-Gali IA, De Allegri M, et al. The unintended consequences of community Verifications for performance-based financing in Burkina Faso. Soc Sci Med 2017;191:226–36. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hope Sr KR. The new public management: a perspective from Africa. New public management. Routledge, 2005: 222–38p.. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hope K, Hope Sr KR. The new public management: context and practice in Africa. International Public Management Journal 2001;4:119–34. 10.1016/S1096-7494(01)00053-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oduro-Mensah E, Kwamie A, Antwi E, et al. Care decision making of frontline providers of maternal and newborn health services in the greater Accra region of Ghana. PLoS One 2013;8:e55610. 10.1371/journal.pone.0055610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Decret n°2-06-656 relatif l'organisation hospitalière 2007.

- 12.Belghiti Alaoui A. Strategies de capacitation en stewardship Au MAROC: RAPPORT de Recherche. RABAT: DHSA; 2003: 169 p. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belghiti AA, Sahel A AZ. Stratégies de capacity building en stewardship Au Maroc Institut de médecine; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belghiti AA, Boffin N, Brouwere D. L’espace de décision de la gestion des ressources humaines sanitaires au Maroc. Rabat: Royaume du Maroc, Ministère de la santé; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaise P, Kegels G. A realistic approach to the evaluation of the quality management movement in health care systems: a comparison between European and African contexts based on Mintzberg's organizational models. Int J Health Plann Manage 2004;19:337–64. 10.1002/hpm.769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blaise PJ, Dujardin B, Kegels G. Culture qualité et organisation bureaucratique, Le défi Du changement dans les systèmes publics de santé: une évaluation réaliste de projets de qualité en Afrique 2004.

- 17.Belrhiti Z, Van Damme W, Belalia A, et al. Does public service motivation matter in Moroccan public hospitals? a multiple embedded case study. Int J Equity Health 2019;18:160. 10.1186/s12939-019-1053-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cours des comptes . Rapport de la cours des comptes sur les centre Hospitalier provincial de Skhirat -Temara. Rabat: Royaumes du Maroc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cours des comptes . Rapport de la cours des comptes sur les centres Hospitalier Régional Marakech. Rabat: Royaume du Maroc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cours des comptes . Rapport de la cours des comptes SUR Le centres Hospitalier Mohamed V de Tanger. Royaume du Maroc: Cours des Comptes; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchal B, Van Belle S, De Brouwere V, et al. Studying complex interventions: reflections from the FEMHealth project on evaluating fee exemption policies in West Africa and Morocco. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:469. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Semlali H. The Morocco Country Case Study : Positive Practice Environements Global Health Workforce Alliance 2010.

- 23.Akhnif E, Macq J, Meessen B. The place of learning in a universal health coverage health policy process: the case of the RAMED policy in Morocco. Health Res Policy Syst 2019;17:21. 10.1186/s12961-019-0421-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohamed A, Youssef EW, Malika S, et al. The ethical dimension in the new public management: revisiting the theory of accountability, the case of public finances in Morocco. Eur Sci J 2016;12:440–7. 10.19044/esj.2016.v12n31p440 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buehler M, demands L. Labour demands, regime Concessions: Moroccan unions and the Arab uprising. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 2015;42:88–103. 10.1080/13530194.2015.973189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.edKwamie ABA, Lehmann U. Leadership, management and organizational cultures. In: Health policy and systems research reader on human resources for health. Geneva: WHO, 2017G A, K S, V G,. [Google Scholar]

- 27.AHPSR . Open Mindsets : Participartory Leadership for Health flagship report 2016. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Håvold JI, Håvold OK. Power, trust and motivation in hospitals. Leadersh Health Serv 2019;32:195–211. 10.1108/LHS-03-2018-0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strauss AL. Negotiations: varieties, contexts, processes, and social order. Jossey-Bass Inc Pub, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glouberman S, Mintzberg H. Managing the care of health and the cure of Disease—Part I: differentiation. Health Care Manage Rev 2001;26:56–69. 10.1097/00004010-200101000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belrhiti Z, Van Damme W, Belalia A, et al. Unravelling the role of leadership in motivation of health workers in a Moroccan public Hospital: a realist evaluation. BMJ Open 2020;10:e031160. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belrhiti Z, Van Damme W, Belalia A, et al. The effect of leadership on public service motivation: a multiple embedded case study in Morocco. BMJ Open 2020;10:e033010. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belrhiti Z. Unravelling the role of leadership in motivation of health workers in four Moroccan hospitals. Morocco: Vrije Universiteit Brussel & Institute of Tropical Medicine, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dinh JE, Lord RG, Gardner WL, et al. Leadership theory and research in the new millennium: current theoretical trends and changing perspectives. Leadersh Q 2014;25:36–62. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marion R, Rumsey MG. Organizational leadership and complexity mechanisms. In: Oxford Handbook of leadership, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uhl-Bien M. Complexity leadership :part 1. Unites States of America: Information aged publishing, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viitala R. Leadership in transformation: a longitudinal study in a nursing organization. J Health Organ Manag 2014;28:602–18. 10.1108/JHOM-02-2014-0032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crozier M. The bureaucratic phenomenon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crozier M, Friedberg E. L'acteur et Le Système 1977.

- 40.Strauss A, Fagerhaugh S, Suczek B. Social organization of medical work. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson TJAssociation BS, ed. Professions and power Kindle edition. Oxon, UK & New York, USA: Routledge Revivals, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friedson E. Profession of medicine: a study of the sociology of applied knowlege: Dodd. Mead & Company 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hugman R. Power in caring professions. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, London: The MacMillan Press LTD, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Day R, Day JV. A review of the current state of Negotiated order theory: an appreciation and a critique. Sociol Q 1977;18:126–42. 10.1111/j.1533-8525.1977.tb02165.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nye JS. Soft power. Foreign Policy 1990;80:153–71. 10.2307/1148580 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nugus P, Greenfield D, Travaglia J, et al. How and where clinicians exercise power: interprofessional relations in health care. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:898–909. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bachrach P, Baratz MS. Two faces of power. Am Polit Sci Rev 1962;56:947–52. 10.2307/1952796 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fiandt K, Doeschot C, Lanning J, et al. Original research: characteristics of risk in patients of nurse practitioner safety net practices. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2010;22:474–9. 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00536.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mintzberg H. The structuring of organizations. readings in strategic management. Springer, 1989: 322–52p.. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glouberman S, Mintzberg H. Managing the Care of Health and the Cure of Disease—Part II:Integration. Health Care Manage Rev 2001;26:70–84. 10.1097/00004010-200101000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davies B, Savulescu J. Solidarity and responsibility in health care. Public Health Ethics 2019;12:133–44. 10.1093/phe/phz008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mechanic D. Sources of power of lower participants in complex organizations. Adm Sci Q 1962;7:349–64. 10.2307/2390947 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cooper DJ, Hinings B, Greenwood R, et al. Sedimentation and transformation in organizational change: the case of Canadian law firms. Organization Studies 1996;17:623–47. 10.1177/017084069601700404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Friedland R, Alford RR. Bringing society back in : symbols, practices and institutional contradictions. In: Powell WW, DiMaggio PJ, eds. The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1991: 232–63p.. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scott RW. Institutions and organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kitchener M. Mobilizing the logic of managerialism in professional fields: the case of academic health centre mergers. Organization Studies 2002;23:391–420. 10.1177/0170840602233004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Decret n°2-14-562 du 7 chaoual 146 (24 juillet 2015) pris pour l’application de la loi -cadre n°>34-09 relative au système de santé et l’offre de soins, en ce qui concerne l’organisation de l’offre de soins, la carte sanitaire et les schémas régiionaux de l’offre de soins 2015.

- 58.InMaroc Rdusanté Mdela, ed. Carte Sanitaire et situation de l’offre de soins 2019. Rabat, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yin RK. Case study research and applications: design and methods. Thousand Oaks, California, USA: Sage publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mahoney J. Qualitative methodology and comparative politics. Comp Polit Stud 2007;40:122–44. 10.1177/0010414006296345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mahoney J, Rueschemeyer D. Comparative historical analysis. Comparative historical analysis in the social sciences 2003:3–38. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 63.l’arrêté du Ministère de la Santé N° 456-11 du 2 Rajeb 1431 (6 juillet 2010) portant règlement Intérieur des Hôpitaux; publié au Bulletin Officiel N° 5926 du 12 rabii II 1432 (17 Mars 2011) 2011.

- 64.Rubin HJ, Rubin IS. Qualitative interviewing: the art of hearing data. Sage, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC: Sage publications, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis. 3 ed. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC: Sage, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yin RK. Qualitative research from start to Finish. New York, London: The Guilford Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC: Sage, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 69.QSR International Pty Ltd . NVivo qualitative data analysis software. 11.4 ED; 2014.

- 70.Dahir du 1 juillet 1941 modifié par dahir du 7 mai 1949 instituant l’Ordre des médecins 1941.

- 71.Akhmisse M. Histoire de la médecine au Maroc des origines l’avènement du protectorat. In: Moussaoui D, Dessarps MR, eds. Histoire de la médecine Au Maroc et dans les pays Arabes et Musulmans. Casablanca: Association Marocaine d’Histoire de la Médecine, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Agyou A. Histoire de la profession infimière Au Maroc Rabat: Ministère de la santé, Maroc; 2019.

- 73.Ghoti M. Histoire de la Médecine au Maroc, le 20 siècle :1896-1994; 1995.

- 74.Moussaoui D, Dessarps MR. Histoire de la médecine au Maroc et dans les pays Arabes et Musulmans Casablanca: Association Marocaine d’Histoire de la Médecine 1995.

- 75.Fourtassi M, Abda N, Bentata Y, et al. Medical education in Morocco: current situation and future challenges. Med Teach 2020;42:973–9. 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1779921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.OECD . Recent trends in international migration of doctors, nurses and medical students; 2019.

- 77.Dahir n°1-15-26 du 29 rabii II 1436 (19 février 2015) portant promulgation de la loi n°131-13 relative l’exercice de la médecine, 131-13 2013.

- 78.WHO . Health workforce snapshot Morocco. Geneva: World health organisation, regional officer for the eastern mediterraneen; 2020. Report No.: WHO-EM/HRH/645/E.

- 79.Arrêté n° 2.06.620 Du 24 Rabii premier 1428 (13 avril 2007) relatif aux règlement interieur Du conseil des infirmièrs Du Ministère de la santé 2007.

- 80.Ackroyd S. Organization Contra organizations: professions and organizational change in the United Kingdom. Organization Studies 1996;17:599–621. 10.1177/017084069601700403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thorne ML. Colonizing the new world of NHS management: the shifting power of professionals. Health Services Management Research 2002;15:14–26. 10.1258/0951484021912798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Waring J, Currie G. Managing expert knowledge: organizational challenges and managerial futures for the UK medical profession. Organization Studies 2009;30:755–78. 10.1177/0170840609104819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Freidson E. Professionalism, the third logic: on the practice of knowledge. University of Chicago press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kitchener M, Kirkpatrick I, Whipp R. Supervising Professional Work under New Public Management: Evidence from an ‘Invisible Trade’. British Journal of Management 2000;11:213–26. 10.1111/1467-8551.00162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Begun JW, Thygeson M. Managing complex healthcare organizations. In: Handbook of healthcare management. Northampton: Edward Elgar, 2015: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mintzberg H. Structure in fives: designing effective organizations. New Jersey, USA: Prentice-Hall, Inc, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Blaise P, Sahel A, Afilal R. Ten years of quality projects and their effect on the organisational culture of the Morrocan health care system. Quality in services: higher education, health care, local government. 7th" Toulon-Verona" Conference; 2-3 September 2004, Toulon, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bucher R, Strauss A. Professions in process. Am J Sociol 1961;66:325–34. 10.1086/222898 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kirkpatrick I, Ackroyd S, Walker R. Professions and Professional Organisation in UK Public Services. In: The new managerialism and public service professions. Springer, 2005: 22–48p.. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Weber M. Economy and society: an outline of interpretive sociology. Univ of California Press, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 91.van Mook WNKA, de Grave WS, Wass V, et al. Professionalism: evolution of the concept. Eur J Intern Med 2009;20:e81–4. 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Moore WE. The professions: roles and rules. Russell Sage Foundation, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Décret n° 2-96-796 Du 11 chaoual 1417 (19 février 1997) fixant Le régime des études et des examens en Vue de l'obtention Du doctorat, Du diplôme d'études supérieures approfondies et Du diplôme d'études supérieures spécialisés ainsi que les conditions et modalités d'accréditation des établissements universitaires assurer La préparation et La délivrance de CES diplômes 1997.

- 94.CNCES . CAHIER des NORMES PEDAGOGIQUES NATIONALESDUDIPLOME de DOCTEUR en MEDECINE. Rabat: Commission Nationale de Coordination de l'Enseignement Supérieur, Ministère de l’éducation nationale, formation professionnelle, enseignement supérieur et recherche scientifique; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Le décret n° 2-64-422 du 26 joumada II 1384 (2 novembre 1964 intituant l’ordre des médecins. 1964.

- 96.Décret n° 2-82-356 Du 16 rebia II 1403 (31 janvier 1983) fixant Le régime des études et des examens en Vue de l'obtention Du diplôme de docteur en médecine (Arabe) 1983.

- 97.Décret n° 2-85-144 du 7 hija 1407 (03 aout 1987) fixant le régime des études et des examens en vue de l’obtention du diplôme de docteur en pharmacie 1987.

- 98.Décret n° 2-82-444 Du 16 rebia II 1403 (31 janvier 1983) fixant Le régime des études et des examens en Vue de l'obtention Du diplôme de docteur en médecine dentaire (Arabe) 1983.

- 99.Noordegraaf M. Risky business: how professionals and professional fields (must) deal with organizational issues. Organization Studies 2011;32:1349–71. 10.1177/0170840611416748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Freidson E. Professional dominance: the social structure of medical care. Transaction Publishers, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Regan TG. Some limits to the hospital as a negotiated order. Soc Sci Med 1984;18:243–9. 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90086-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Décret N° 2.93.602 Du 29 Octobre 1993 creation of Instituts de formation aux Carrières de Santé (IFCS) « 1993.

- 103.Arrêté n° 2.06.620 Du 24 Rabii premier 1428 (13 avril 2007) relatfi aux règlement interieur Du conseil des infirmièrs Du Ministère de la santé 2007.

- 104.Mintzberg H, Van der Heyden L. Organigraphs: drawing how companies really work. Harv Bus Rev 1999;77:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nathan ML, Mitroff II. The use of Negotiated order theory as a tool for the analysis and development of an Interorganizational field. J Appl Behav Sci 1991;27:163–80. 10.1177/0021886391272002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fine GA. Negotiated orders and organizational cultures. Annu Rev Sociol 1984;10:239–62. 10.1146/annurev.so.10.080184.001323 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Maines DR, Charlton JC. The negotiated order approach to the analysis of social organization. Studies in Symbolic Interaction 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Harris JE. The internal organization of hospitals: some economic implications. The Bell Journal of Economics 1977;8:467–82. 10.2307/3003297 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.De Geyndt W. Does autonomy for public hospitals in developing countries increase performance? evidence-based case studies. Soc Sci Med 2017;179:74–80. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.02.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Strauss A. Interorganizational negotiation. Urban Life 1982;11:350–67. 10.1177/089124168201100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Belrhiti Z, Nebot Giralt A, Marchal B. Complex leadership in healthcare: a scoping review. Int J Health Policy Manag 2018;7:1073–84. 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ford R. Complex leadership competency in health care: towards framing a theory of practice. Health Serv Manage Res 2009;22:101–14. 10.1258/hsmr.2008.008016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Uhl-Bien M, Marion R, McKelvey B. Complexity leadership theory: shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge era. Leadersh Q 2007;18:298–318. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Plsek PE, Wilson T. Complexity, leadership, and management in healthcare organisations. BMJ 2001;323:746–9. 10.1136/bmj.323.7315.746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gilson L. Everyday politics and the leadership of health policy implementation. Health Syst Reform 2016;2:187–93. 10.1080/23288604.2016.1217367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Van Belle SB, Marchal B, Dubourg D, et al. How to develop a theory-driven evaluation design? lessons learned from an adolescent sexual and reproductive health programme in West Africa. BMC Public Health 2010;10:741. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Héritier A, Lehmkuhl D. The shadow of hierarchy and new modes of governance. J Public Policy 2008;28:1–17. 10.1017/S0143814X08000755 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Barasa EW, Molyneux S, English M, et al. Hospitals as complex adaptive systems: a case study of factors influencing priority setting practices at the hospital level in Kenya. Soc Sci Med 2017;174:104–12. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gilson L, Agyepong IA. Strengthening health system leadership for better governance: what does it take? Health Policy Plan 2018;33:ii1–4. 10.1093/heapol/czy052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zimmerman B, Lindberg C, Plsek P. A complexity science primer: what is complexity science and why should I learn about it. Adapted From: Edgeware: Lessons From Complexity Science for Health Care Leaders, Dallas, TX: VHA Inc, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zimmerman B, Lindberg C, Plsek P. Edgeware: lessons from complexity science for health care leaders. 2nd ed. USA: Irving, Tex: VHA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zimmerman JE, Rousseau DM, Duffy J, et al. Intensive care at two teaching hospitals: an organizational case study. Am J Crit Care 1994;3:129–38. 10.4037/ajcc1994.3.2.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kernick D. Complexity and healthcare organization: a view from the street. Radcliffe Publishing, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Carmont S-A, Mitchell G, Senior H, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness, barriers and facilitators to general practitioner engagement with specialist secondary services in integrated palliative care. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2018;8:385–99. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ferrinho P, Van Lerberghe W, Fronteira I, et al. Dual practice in the health sector: review of the evidence. Hum Resour Health 2004;2:14. 10.1186/1478-4491-2-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials