Key Points

Question

Do onsite contraceptive services with and without incentives increase verified prescription contraceptive use compared with usual care among women with opioid use disorder at high risk for unintended pregnancy and do so in a cost-beneficial manner?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 138 participants, a significant graded increase in verified prescription contraceptive use was seen in participants assigned to usual care vs contraceptive services vs contraceptive services plus incentives at the 6-month end-of-treatment assessment. Both contraceptive services and contraceptive services plus incentive interventions yielded economic benefits.

Meaning

Results of this study suggest that onsite contraceptive services exceeded usual care, but that the combination of contraceptive services with incentives for attending follow-up visits to assess contraceptive satisfaction was the most efficacious and cost-beneficial intervention.

Abstract

Importance

Rates of in utero opioid exposure continue to increase in the US. Nearly all of these pregnancies are unintended but there has been little intervention research addressing this growing and costly public health problem.

Objective

To test the efficacy and cost-benefit of onsite contraceptive services with and without incentives to increase prescription contraceptive use among women with opioid use disorder (OUD) at high risk for unintended pregnancy compared with usual care.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A randomized clinical trial of 138 women ages 20 to 44 years receiving medication for OUD who were at high risk for an unintended pregnancy at trial enrollment between May 2015 and September 2018. The final assessment was completed in September 2019. Data were analyzed from October 2019 to March 2021. Participants received contraceptive services at a clinic colocated with an opioid treatment program.

Interventions

Participants were randomly assigned to receive 1 of 3 conditions: (1) usual care (ie, information about contraceptive methods and community health care facilities) (n = 48); (2) onsite contraceptive services adapted from the World Health Organization including 6 months of follow-up visits to assess method satisfaction (n = 48); or (3) those same onsite contraceptive services plus financial incentives for attending follow-up visits (n = 42).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Verified prescription contraceptive use at 6 months with a cost-benefit analysis conducted from a societal perspective.

Results

In this randomized clinical trial of 138 women (median age, 31 years [range, 20-44 years]), graded increases in verified prescription contraceptive use were seen in participants assigned to usual care (10.4%; 95% CI, 3.5%-22.7%) vs contraceptive services (29.2%; 95% CI, 17.0%-44.1%) vs contraceptive services plus incentives (54.8%; 95% CI, 38.7%-70.2%) at the 6-month end-of-treatment assessment (P < .001 for all comparisons). Those effects were sustained at the 12-month final assessment (usual care: 6.3%; 95% CI, 1.3%-17.2%; contraceptive services: 25.0%; 95% CI, 13.6%-39.6%; and contraceptive services plus incentives: 42.9%; 95% CI, 27.7%-59.0%; P < .001) and were associated with graded reductions in unintended pregnancy rates across the 12-month trial (usual care: 22.2%; 95% CI, 11.2%-37.1%; contraceptive services: 16.7%; 95% CI, 7.0%-31.4%; contraceptive services plus incentives: 4.9%; 95% CI, 0.6%-15.5%; P = .03). Each dollar invested yielded an estimated $5.59 (95% CI, $2.73-$7.91) in societal cost-benefits for contraceptive services vs usual care, $6.14 (95% CI, $3.57-$7.08) for contraceptive services plus incentives vs usual care and $6.96 (95% CI, $0.62-$10.09) for combining incentives with contraceptive services vs contraceptive services alone.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this randomized clinical trial, outcomes with both onsite contraceptive service interventions exceeded those with usual care, but the most efficacious, cost-beneficial outcomes were achieved by combining contraceptive services with incentives. Colocating contraceptive services with opioid treatment programs offers an innovative, cost-effective strategy for preventing unintended pregnancy.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02411357

This randomized clinical trial assesses whether offering usual care, contraceptive services without incentives, or contraceptive services with incentives in opioid use disorder treatment programs results in a graded increase in prescription contraceptive use and produces cost-benefits.

Introduction

Increases in maternal opioid use have led to an almost doubling of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) in the US in the past 10 years.1 Monitoring and treatment of NAS are associated with longer hospital stays after delivery, averaging nearly 16 days.2 The increased prevalence of NAS combined with extended hospitalization has increased US postnatal care costs to nearly $600 million per year, more than 80% of which is covered by Medicaid.2 These costs do not include additional health care costs later in life or non–health care costs often associated with NAS diagnoses (eg, special education).3,4,5

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Pediatrics have called for increased efforts to reduce opioid use during pregnancy and NAS, including ensuring access to contraception to prevent unintended pregnancy among women who use opioids.6,7 More than 75% of women with opioid use disorder (OUD) report having had an unintended pregnancy,8,9,10 but they are less likely to use any contraception and more likely to use less effective nonprescription methods such as condoms compared with women who do not use drugs.11 They also report wanting easier access to contraception.12,13

To our knowledge, there is only a single controlled study in this area, the pilot for the current trial.14 That trial tested a novel 2-component intervention informed by behavioral economics that combined (1) provision of onsite contraceptive services guided by the patient-centered World Health Organization (WHO) Contraceptive Decision-Making Tool for Family Planning Clients and Providers15 with (2) financial incentives for attending follow-up visits to assess method satisfaction in an effort to increase prescription contraceptive use, defined as pills, patch, ring, injection, intrauterine device (IUD), and implant. People with OUD often struggle with other co-occurring psychiatric conditions and wide-ranging psychosocial instability that may pose difficulties in making the effort to initiate and maintain prescription contraceptive use. In this intervention, colocating contraceptive services with an opioid treatment program was expected to reduce the burden associated with initiating use and the incentives were expected to reduce the burden associated with adhering to follow-up visits. Incentives were earned solely for attending follow-up visits.

Participants in the pilot trial were women at high risk of unintended pregnancy receiving medication for OUD. Results of the pilot trial suggested that the intervention increased contraceptive use and may decrease unintended pregnancy as compared to usual care, but the small sample size and lack of a postintervention assessment limited the strength of the conclusions drawn. Moreover, the design did not allow us to parse the contributions of the contraceptive services and incentives components of the intervention to the outcomes nor did we assess the cost-benefit of the intervention. The aim of this trial was to test whether offering usual care, contraceptive services without incentives, or contraceptive services with incentives in OUD treatment programs results in a graded increase in prescription contraceptive use and produces cost-benefits.

Methods

Participants

In a randomized clinical trial, women ages 20 to 44 years receiving medication for OUD who were at high risk for an unintended pregnancy at trial were enrolled between May 2015 and September 2018. The final assessment was completed in September 2019. Data were analyzed from October 2019 to March 2021. Participants were recruited from an opioid treatment program in Burlington, Vermont. Eligible participants had no plans to become pregnant in the next 6 months and provided written informed consent. The eMethods in the Supplement report the full eligibility criteria. The University of Vermont Institutional Review Board approved the trial and an independent data and safety monitoring board assembled for this trial provided oversight. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline for randomized clinical trials.

Conditions

Trial staff enrolled and randomized participants (1:1:1) based on computer-generated stratified randomization sequences prepared by the trial statistician (eMethods in the Supplement).

Usual Care

Consistent with OUD treatment guidelines,16 participants in the usual care (UC) group received UC consisting of a general information brochure about contraceptive methods and contact information for community contraceptive service facilities.

Contraceptive Services

At the first trial visit, using the WHO Tool15 as a guide, trial staff, typically a nurse practitioner, met with each of the participants in the group receiving contraceptive services (CS) in the colocated CS clinic and talked with them about whether a prescription contraceptive method aligned with their values, preferences, and goals. If so, using shared decision-making, staff helped the participant choose the method that best suited them, provided method-specific educational counseling, and gave them the method free. Pills, patches, and rings were dispensed immediately; participants were given the opportunity to initiate these methods in the clinic and offered a 12-month supply. Injections, IUDs, and implants were administered or inserted immediately by trial staff.

Regarding follow-up visits to assess method satisfaction, the WHO Tool calls for up to 2 visits depending on the method, but WHO has encouraged adaptation of the tool to tailor it to different settings and populations, including increasing the number of follow-up visits.17 In the general population, prescription contraceptive discontinuation in the first 6 months after initiation can exceed 50%.18 There were concerns it would be even higher among people with OUD, so participants were scheduled to attend 13 onsite follow-up visits over the 6-month intervention period. Visits were weekly for the first 2 months, then every other week for 2 months, then monthly for the last 2 months, based on the general population’s discontinuation pattern.18

At each follow-up visit, participants provided a urine specimen for pregnancy testing and completed the Time-Line Followback Sexual Behavior Interview19,20 for the period since their last visit or assessment (see below). The interview was adapted slightly to focus on pregnancy risk rather than HIV risk. Participants who had initiated prescription contraception were asked about method satisfaction, including assistance managing side effects, and could discontinue or switch methods at any time. Participants who had not initiated prescription contraception at their initial meeting with trial staff, perhaps because they wanted to consider different methods or talk with their partner, were offered assistance in selecting a method if interested and could initiate a method at any of the 13 visits. Participants were never required to initiate a prescription method, could choose to use nonprescription methods, or not use any method. Each participant was also offered condoms and emergency contraception at every visit.

Contraceptive Services Plus Incentives

Participants in this group received the same contraceptive services described above coupled with financial incentives (CS+) to increase attendance at the WHO-recommended follow-up visits. Incentives were independent of participants’ choices around contraceptive use; participants who initiated a prescription method but discontinued it, who used nonprescription methods, or did not use any method still earned an incentive at any visit they attended. Incentives started at $15 for the first visit and increased by $2.50 for each consecutive follow-up visit attended. Incentives were provided in the form of gift cards for retailers of each participant’s choice rather than cash. Maximum possible earnings over the 6-month intervention period were $437.50.

After randomization, all participants completed a 10-item true-false quiz to ensure that they understood their assigned condition. For example, the UC quiz included the item “The study will provide you with birth control supplies” (false); for CS, “You will be asked to attend 13 follow-up visits as part of the study but will not receive any financial incentives for attending these visits” (true); and for CS+, “In order to earn incentives, you must use 1 of the 6 methods of birth control offered in the study” (false). After each participant completed the appropriate quiz, trial staff discussed any incorrect answers with them so the details of their assigned condition were clear.

Participants in any of the 3 groups who became pregnant could continue in the protocol and were offered assistance accessing community services such as options counselors and prenatal care facilities.

Assessments

All participants completed assessments 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after randomization. At each assessment, participants provided a urine specimen for pregnancy testing and completed the Time-Line Followback Sexual Behavior Interview. Participants who reported using prescription contraception for the 28 days prior to the 6-month and 12-month assessments were asked if trial staff could verify their self-reported use owing to long-standing concerns in the field about the reliability of self-reported contraceptive use21 and substantial discrepancies between self-report and verified contraceptive use.22 Verification was by pill count (pill), medical record review (injection), pelvic examination (ring, IUD), or palpation (implant); no participants reported using a patch. At the 6-month assessment, participants were again asked about their pregnancy intentions for the next 6 months. Participants were compensated $50 to $65 per assessment independent of whether they were using contraception, consented to verification, or had become pregnant.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was verified prescription contraceptive use at the 6-month assessment. It was assumed that participants who did not complete an assessment were not using prescription contraception. In addition, if a participant became pregnant, all subsequent assessments were recorded as not using prescription contraception.

Secondary outcomes were verified prescription contraceptive use at the 12-month assessment, verified long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) method (ie, IUD or implant) use at the 6-month and 12-month assessments, and the percentage of participants with unintended pregnancies during the 12-month trial period. Participants who became pregnant and reported the pregnancy was intended (n = 3) were not included in the unintended pregnancy analysis.

A cost-benefit analysis from a societal perspective (ie, health care and non–health care related sectors) of the intervention conditions (ie, CS, CS+) over the 12-month trial period was conducted.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared between conditions using analyses of variance and χ2 tests. Cochran-Armitage χ2 tests for trend were used to test for a graded effect across the 3 treatment conditions (UC vs CS vs CS+) on the primary and all secondary outcomes. Statistical significance was based on P < .05. Pairwise comparisons between conditions were based on Pearson χ2 tests. Absolute risk reduction (ARR) and number needed to treat (NNT) were computed along with corresponding 95% CIs as measures of effect size. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (SAS Institute). With the current sample size of 138 participants, power for the Cochran-Armitage test for trend is greater than 95% using α = .05 to detect a graded effect across the UC, CS, and CS+ conditions in verified prescription contraceptive use at the 6-month assessment assuming ordered proportions differ by 20% (eg, 5% vs 25% vs 45% or 20% vs 40% vs 60%).

Regarding the cost-benefits analysis, the probability of unintended pregnancy for each participant during the 12-month trial period was calculated from the number of months of documented prescription contraceptive use multiplied by the derived monthly likelihood of unintended pregnancy associated with each contraceptive method used.23,24

Contraceptive services costs in both CS and CS+ were derived using a microcosting approach25 and included costs to provide contraceptive counseling, a 12-month supply of the method, and all costs incurred to attend any of the 13 follow-up visits. CS+ costs included the additional costs to procure and distribute the gift cards. Costs of contraceptive services obtained from community facilities were estimated from the literature.26,27 All costs were inflated to 2019 US dollars based on the medical services component of the Consumer Price Index.

Benefit-cost ratios (ie, value of unintended pregnancies avoided divided by condition costs) were calculated for each comparison of conditions. The benefits for each comparison were calculated by multiplying the estimated societal cost of an unintended pregnancy in this population by the incremental difference in effectiveness between conditions. The net cost was the difference in costs between conditions. The interventions were deemed cost beneficial if the ratios exceeded 1.00. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed to estimate the uncertainty of the results. Further details about this analysis are available in the eMethods in the Supplement.

Results

Participants

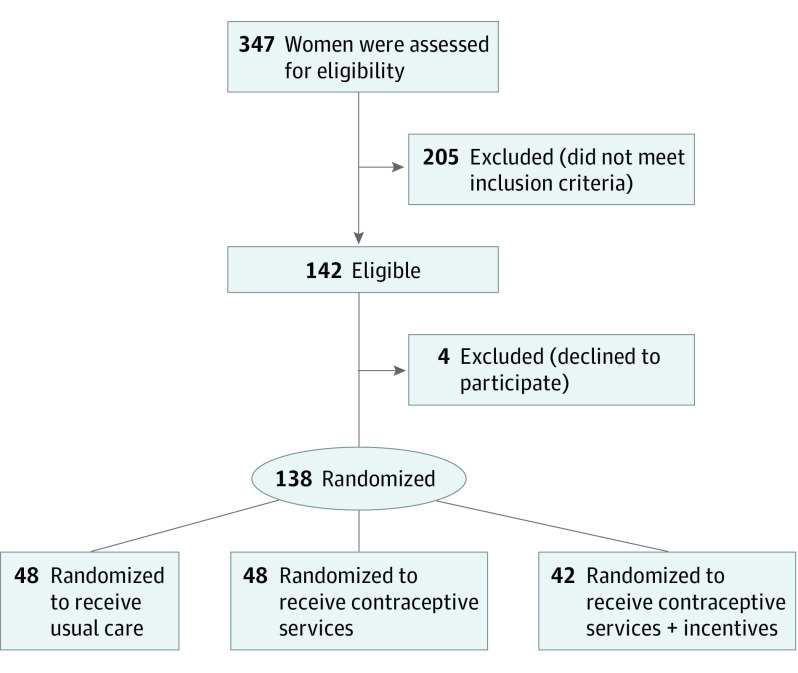

A total of 138 participants (median age, 31 years [range, 20-44 years]) were randomly assigned to UC (n = 48), CS (n = 48), or CS+ (n = 42) conditions between May 5, 2015, and September 19, 2018, when recruitment ended (Figure 1). The final assessment was completed in September 2019. Most participants (88.4%; 122 of 138) reported at least 1 prior unintended pregnancy. Although participants did not have to report interest in using prescription contraception to be eligible, most (87.0%; 120 of 138) reported plans to start prescription contraception in the near future, with half indicating preference for an implant or IUD (51.4%; 71 of 138). There were no significant differences between conditions in baseline characteristics (Table 1).

Figure 1. Participant Flow Diagram.

Table 1. Characteristics of Participants.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (n = 48) | Contraceptive services (n = 48) | Contraceptive services plus incentives (n = 42) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 30.6 (6.0) | 32.0 (5.2) | 31.6 (4.9) |

| Race | |||

| White racea | 43 (90) | 45 (94) | 40 (95) |

| Non-White raceb | 5 (10) | 3 (6) | 2 (5) |

| Education, mean (SD), y | 12.1 (1.7) | 12.0 (1.7) | 12.0 (1.6) |

| Never married | 36 (75) | 29 (62) | 31 (74) |

| Current smoker | 42 (88) | 43 (90) | 38 (90) |

| Has steady male sexual partner | 40 (85) | 42 (89) | 37 (90) |

| One or more unintended pregnancies in lifetime | 41 (85) | 42 (88) | 39 (93) |

| Intends to start prescription birth control within next week | 42 (88) | 41 (85) | 37 (88) |

| Prefers a long-acting method of birth control | 24 (50) | 25 (52) | 22 (52) |

Race was reported by the participants. White participants were also all non-Hispanic.

Non-White participants were as follows: American Indian (n = 4), Asian (n = 1), Black (n = 4), and Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (n = 1).

Follow-up Visit Attendance

As expected, follow-up visit attendance was significantly greater for participants in the CS+ group compared with participants in the CS group (78.7% [463 of 588] vs 29.5% [198 of 672]; P < .001).

Verified Prescription Contraceptive Use

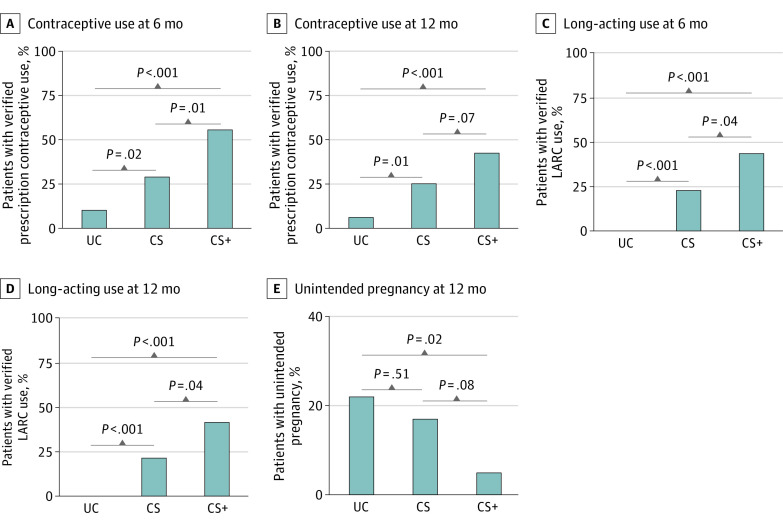

The 3 conditions differed significantly on the primary outcome measure, verified prescription contraceptive use at the 6-month assessment (P < .001; Figure 2A; Table 2). Verified prescription contraceptive use was greater for participants in the CS+ group compared with participants in the CS group (54.8% [23 of 42; 95% CI, 38.7%-70.2%] vs 29.2% [14 of 48; 95% CI, 17.0%-44.1%]; NNT = 4; 95% CI, 3-18; P = .01). Both interventions produced greater verified contraceptive use compared with UC (10.4% [5 of 48; 95% CI, 3.5%-22.7%]; NNT = 3; 95% CI, 2-4, P < .001 and NNT = 6; 95% CI, 3-31; P = .02, for CS+ and CS, respectively). Similar results were observed at the 12-month assessment (Figure 2B; Table 2), although the difference between CS+ and CS was less pronounced (42.9% [18 of 42] vs 25.0% [12 of 48]; P = .07). Participants completed 94.9% (131 of 138) and 92.0% (127 of 138) of all scheduled 6-month and 12-month assessments, respectively, with no differences among conditions.

Figure 2. Percentage of Participants With Verified Prescription Contraceptive Use, Verified Long-acting Reversible Contraceptive Use, and Who Experienced an Unintended Pregnancy.

A and B, The percentage of participants with verified prescription contraceptive use at the end of the 6-month intervention period and at the end of the 12-month trial in the 3 conditions. Verified use was defined as a self-report of adherence to a method for the 28 days leading up to the assessment and verification based on pill count (pill), medical record review (injection), palpation (implant), or pelvic examination (ring, intrauterine device [IUD]). C and D, Percentage of participants with verified long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC; IUD or implant) use at the end of the 6-month intervention period and at the end of the 12-month trial. E, Percentage of participants who experienced an unintended pregnancy during the 12-month trial period. For panels A-D, n = 48 for usual care (UC), n = 48 for contraceptive services (CS), and n = 42 for contraceptive services plus incentives (CS+) and for panel E, n = 45 for UC, n = 42 for CS, and n = 41 for CS+. All Cochran-Armitage χ2 tests for trend were significant (P ≤ .025). Significance levels for pairwise comparisons are based on Pearson χ2 tests.

Table 2. Outcome Measures.

| Outcome measure | Conditiona | % (95% CI) | P valueb | Comparison | ARR (95% CI)c | NNT (95% CI)d | P valuee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verified contraceptive use: 6 mo | Contraceptive services plus incentives | 54.8 (38.7 to 70.2) | <.001 | CS+ vs UC | 44.4 (27.0 to 61.7) | 3 (2 to 4) | <.001 |

| Contraceptive services | 29.2 (17.0 to 44.1) | CS vs UC | 18.8 (3.3 to 34.2) | 6 (3 to 31) | .02 | ||

| Usual care | 10.4 (3.5 to 22.7) | CS+ vs CS | 25.6 (5.8 to 45.5) | 4 (3 to 18) | .01 | ||

| Verified contraceptive use: 12 mo | Contraceptive services plus incentives | 42.9 (27.7 to 59.0) | <.001 | CS+ vs UC | 36.6 (20.1 to 53.1) | 3 (2 to 5) | <.001 |

| Contraceptive services | 25.0 (13.6 to 39.6) | CS vs UC | 18.7 (4.7 to 32.8) | 6 (4 to 22) | .01 | ||

| Usual care | 6.3 (1.3 to 17.2) | CS+ vs CS | 17.9 (−1.5 to 37.2) | 6 (3 to −67) | .07 | ||

| Verified LARC use: 6 mo | Contraceptive services plus incentives | 42.9 (27.7 to 59.0) | <.001 | CS+ vs UC | 42.9 (27.9 to 57.8) | 3 (2 to 4) | <.001 |

| Contraceptive services | 22.9 (12.0 to 37.3) | CS vs UC | 22.9 (11.0 to 34.8) | 5 (3 to 10) | <.001 | ||

| Usual care | 0.0 (0.0 to 7.4) | CS+ vs CS | 19.9 (0.8 to 39.1) | 5 (3 to 121) | .04 | ||

| Verified LARC use: 12 mo | Contraceptive services plus incentives | 40.5 (25.6 to 56.7) | <.001 | CS+ vs UC | 40.5 (25.6 to 55.3) | 3 (2 to 4) | <.001 |

| Contraceptive services | 20.8 (10.5 to 35.0) | CS vs UC | 20.8 (9.3 to 32.3) | 5 (4 to 11) | <.001 | ||

| Usual care | 0.0 (0.0 to 7.4) | CS+ vs CS | 19.6 (0.8 to 38.4) | 6 (3 to 115) | .04 | ||

| Unintended pregnancy: 12 mo | Contraceptive services plus incentives | 4.9 (0.6 to 15.5) | .03 | CS+ vs UC | 17.3 (3.5 to 31.2) | 6 (4 to 29) | .02 |

| Contraceptive services | 16.7 (7.0 to 31.4) | CS vs UC | 5.5 (−11.0 to 22.1) | 19 (5 to −9) | .51 | ||

| Usual care | 22.2 (11.2 to 37.1) | CS+ vs CS | 11.8 (−1.2 to 24.8) | 9 (4 to −78) | .08 |

Abbreviations: ARR, absolute risk reduction; CS, contraceptive services; CS+, contraceptive services plus incentives; LARC, long-acting reversible contraceptive; NNT, number needed to treat; UC, usual care.

Usual care, n = 48; contraceptive services, n = 48; and contraceptive services plus incentives, n = 42 for all outcomes except unintended pregnancy where n = 45 for usual care, n = 42 for contraceptive services, and n=41 for contraceptive services plus incentives.

P value based on Cochran-Armitage χ2 tests.

Positive values for absolute risk reduction represent increased use of contraception (ie, reduction of nonuse).

Negative values for number needed to treat represents number to harm (ie, number of participants to treat to have 1 fewer positive outcomes).28

P value based on Pearson χ2 tests.

Verified LARC Use

Similar results were seen for the secondary outcome of verified LARC use at the 6-month and 12-month assessments (Figure 2C and D; Table 2). At the 6-month assessment, verified LARC use was greater in CS+ compared with CS (42.9% [18 of 42] vs 22.9% [11 of 48]; P = .04). Verified LARC use was greater in CS+ and CS compared with UC (0.0% [0 of 48]); P < .001 for both). Similarly, at the 12-month assessment, verified LARC use was greater in CS+ than CS (40.5% [17 of 42] vs 20.8% [10 of 48]; P = .04) and levels in CS+ and CS exceeded those in UC (0.0% [0 of 48]; P < .001 for both).

Unintended Pregnancy

There was a significant difference between conditions in the percentage of participants with 1 or more unintended pregnancies during the 12-month trial period among those with complete assessment data (P = .03; Figure 2E, Table 2), with the proportion in CS+ lower than UC (4.9% [2 of 41] vs 22.2% [10 of 45]; P = .02), but not CS (16.7% [7 of 42]; P = .08). UC and CS were not different (P = .51).

Cost-Benefit Analysis

The estimated costs of an unintended pregnancy among people with OUD from a societal perspective, the total costs and benefits of each condition per participant, and the benefit-cost ratios of each comparison are presented in Table 3. Overall, each dollar invested yields $5.59 (95% CI, $2.73-$7.91) in societal benefits for CS vs UC, $6.14 (95% CI, $3.57-$7.08) for CS+ vs UC and $6.96 (95% CI, $0.62-$10.09) for CS+ vs CS.

Table 3. Cost-Benefit Analysis Over 12 Months.

| Variable | Measure (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care | Contraceptive services | Contraceptive services plus incentives | |

| Cost of an unintended pregnancy, $a | 85 122 | 85 122 | 85 122 |

| Average unintended pregnancy rate per participant | 0.19 (0.18-0.20) | 0.14 (0.12-0.17) | 0.10 (0.07-0.13) |

| Incremental effectiveness relative to usual care | NA | 0.05 (0.03-0.08) | 0.09 (0.06-0.012) |

| Incremental effectiveness relative to contraceptive services | NA | NA | 0.04 (0.00-0.08) |

| Benefits per participant relative to usual care, $b | NA | 4344 (2260-6553) | 8001 (5314-10 535) |

| Benefit per participant relative to contraceptive services, $b | NA | NA | 3657 (408-6659) |

| Average cost per participant, $ | 204 (56-426) | 981 (732-1234) | 1506 (1323-1679) |

| Incremental cost relative to usual care, $ | NA | 777 (440-1076) | 1302 (1025-1549) |

| Incremental cost relative to contraceptive services, $ | NA | NA | 525 (187-833) |

| Benefit-cost ratios relative to usual carec | NA | 5.59 (2.73-7.91) | 6.14 (3.57-7.08) |

| Benefit-cost ratio relative to contraceptive servicesc | NA | NA | 6.96 (0.62-10.09) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Costs were identified from both health care and non–health care care-related sectors (ie, societal perspective). Health care costs based on national estimates,29,30 adjusted to Vermont state equivalents.31 Non–health care costs were based on both national estimates3,32 and Vermont-specific estimates.33,34 All calculations weighted to reflect the proportion of each unintended pregnancy outcome observed during the trial. See Supplement for additional information about how this value was derived.

Calculated by multiplying the cost of an unintended pregnancy (row 1) by the incremental effectiveness of each intervention condition compared with usual care (row 3) and to each other (row 4).

Calculated by dividing the benefits per participant in each intervention condition relative to usual care (row 5) and to each other (row 6) by the incremental cost per participant in each intervention condition relative to usual care (row 8) and to each other (row 9). Higher benefit-cost ratios indicate a greater economic benefit. These ratios are not additive.

Discussion

This study provides strong empirical data that use of prescription contraception can be significantly increased and unintended pregnancies decreased in women with OUD at high risk for unintended pregnancy. We observed a graded effect on verified prescription contraceptive use and on unintended pregnancies, with the worst outcomes in the UC condition, intermediate outcomes in the CS condition, and the best outcomes in the CS+ condition. These results systematically replicate an earlier finding that CS+ increases use of prescription contraception compared with UC14 and suggests that the effect is sustained through 12 months, that there are corresponding decreases in unintended pregnancy, and that both the contraceptive services and incentives components of the intervention independently contribute to these outcomes.

We believe the present study provides new knowledge regarding the economic value of colocating contraceptive services with an OUD treatment program and to date the first estimate of the health care-related and non–health care-related costs of an unintended pregnancy among people with OUD. These results suggest that CS and CS+ were associated with better economic outcomes than current policy recommendations when considering the substantial cost of an unintended pregnancy in this population ($85 122). The considerable returns on investment for CS and CS+ compared with UC were due to reductions in unintended pregnancy relative to UC. CS+ increased the overall 12-month cost per participant, but there was still a sizable return on investment due to the greater reduction in unintended pregnancy with CS+. These findings suggest that the additional cost of the CS+ intervention is offset by the substantial societal cost-benefits associated with averting an unintended pregnancy in this population.

Differences in unintended pregnancy and benefit-cost ratios may owe in part to significant differences in LARC use across conditions. LARC methods are the most effective forms of reversible contraception, in part because they last for a minimum of 3 years and they are not prone to user error. Despite half of all participants reporting a preference for a LARC method at trial intake, none of the participants in the UC group had a verified LARC method at either the 6-month or 12-month assessment, consistent with low rates of use among women with OUD and other SUDs.11 The present results suggest that reducing barriers to LARC initiation and continuation by providing free insertion in a colocated clinic and frequent follow-up visits to assess method satisfaction increases LARC use substantially, but that the addition of other interventions such as financial incentives to increase attendance at the follow-up visits are needed to bring LARC use in line with women’s stated desires.

Limitations

This study has limitations. There have been debates about contraception and financial incentives.35 We agree with others that the potential for coercion is high when large incentives are made contingent on contraceptive use, such as past efforts to make welfare payments dependent on implant use36 or the Project Prevention $300 cash payments for sterilization or LARC insertion.37 In contrast, our empirically based approach builds on a robust scientific literature on the use of financial incentives with patients with SUDs to increase drug abstinence and other treatment goals such as appointment attendance38 and uses gift cards of much smaller value that are offered over time. However, in instances in which there is opposition to incentives, the CS condition is an efficacious alternate that provides substantial cost-benefits relative to UC. Other potential limitations of the trial include the small, predominantly White population sample and the intensity of the intervention. The large intervention effects may obviate concerns about sample size. While most women treated for OUD are White,39 it will be important to assess efficacy in other racial/ethnic populations given a history of reproductive injustice among non-White women. Whether the number of follow-up visits can be reduced while retaining efficacy is also an important empirical question.

Conclusions

Overall, the findings of this randomized clinical trial provide treatment programs with 2 rigorously evaluated, efficacious, and cost-beneficial interventions, with the best outcomes achieved by combining colocated contraceptive services with incentives. These results provide sorely needed information that will help address the growing public health problems of opioid use during pregnancy and NAS.

Trial Protocol

eMethods. Additional Methods

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Hirai AH, Ko JY, Owens PL, Stocks C, Patrick SW. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and maternal opioid-related diagnoses in the US, 2010-2017. JAMA. 2021;325(2):146-155. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.24991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strahan AE, Guy GP Jr, Bohm M, Frey M, Ko JY. Neonatal abstinence syndrome incidence and health care costs in the United States, 2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(2):200-202. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fill MA, Miller AM, Wilkinson RH, et al. Educational disabilities among children born with neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3):e20180562. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan PL, Wang Y. The opioid epidemic, neonatal abstinence syndrome, and estimated costs for special education services. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(13)(suppl):S264-S269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peacock-Chambers E, Leyenaar JK, Foss S, et al. Early intervention referral and enrollment among infants with neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2019;40(6):441-450. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ko JY, Wolicki S, Barfield WD, et al. CDC Grand Rounds: Public health strategies to prevent neonatal abstinence syndrome. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(9):242-245. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6609a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patrick SW, Schiff DM; COMMITTEE ON SUBSTANCE USE AND PREVENTION . COMMITTEE ON SUBSTANCE USE AND PREVENTION. A public health response to opioid use in pregnancy. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3):e20164070. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heil SH, Jones HE, Arria A, et al. Unintended pregnancy in opioid-abusing women. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;40(2):199-202. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meschke LL, McNeely C, Brown KC, Prather JM. Reproductive health knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among women enrolled in medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2018;27(10):1215-1224. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2017.6564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith C, Morse E, Busby S. Barriers to reproductive healthcare for women with opioid use disorder. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2019;33(2):E3-E11. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terplan M, Hand DJ, Hutchinson M, Salisbury-Afshar E, Heil SH. Contraceptive use and method choice among women with opioid and other substance use disorders: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2015;80:23-31. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinowitz N, Muqueeth S, Scheibler J, Salisbury-Afshar E, Terplan M. Family planning in substance use disorder treatment centers: opportunities and challenges. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51(11):1477-1483. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1188944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacAfee LK, Harfmann RF, Cannon LM, et al. Substance use treatment patient and provider perspectives on accessing sexual and reproductive health services: barriers, facilitators, and the need for integration of care. Subst Use Misuse. 2020;55(1):95-107. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2019.1656255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heil SH, Hand DJ, Sigmon SC, Badger GJ, Meyer MC, Higgins ST. Using behavioral economic theory to increase use of effective contraceptives among opioid-maintained women at risk of unintended pregnancy. Prev Med. 2016;92:62-67. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization . John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Center for Communication Programs. Decision-making tool for family planning clients and providers. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/9241593229index/en/

- 16.American Society of Addiction Medicine . Public policy statement on substance use, misuse, and use disorders during and following pregnancy, with an emphasis on opioids. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/substance-use-misuse-and-use-disorders-during-and-following-pregnancy.pdf?sfvrsn=644978c2_4

- 17.World Health Organization . Decision-making tool for family planning clients and providers: technical adaptation guide. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/Technical_adaptation_guide.pdf

- 18.Nelson AL, Westhoff C, Schnare SM. Real-world patterns of prescription refills for branded hormonal contraceptives: a reflection of contraceptive discontinuation. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):782-787. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181875ec5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wein Hardt LS, Carey MP, Misato SA, Carey KB, Cohen MM, Wickramasinghe SM. Reliability of the timeline follow-back sexual behavior interview. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20(1):25-30. doi: 10.1007/BF02893805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weinhardt LS. Effects of a detailed sexual behavior interview on perceived risk of HIV infection: preliminary experimental analysis in a high risk sample. J Behav Med. 2002;25(2):195-203. doi: 10.1023/A:1014888905882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuart GS, Grimes DA. Social desirability bias in family planning studies: a neglected problem. Contraception. 2009;80(2):108-112. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson HN, Borrero S, Lehman E, Helot DL, Chuang CH. Measuring oral contraceptive adherence using self-report versus pharmacy claims data. Contraception. 2017;96(6):453-459. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trussell J, Aiken ARA, Micks E, Guthrie KA. Efficacy, safety, and personal considerations. In: Hatcher RA, Nelson AL, Trussell J, et al, eds. Contraceptive Technology. Ayer Co Publishers, Inc.; 2018: 95–128. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaughan B, Trussell J, Kast K, Singh S, Jones R. Discontinuation and resumption of contraceptive use: results from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Contraception. 2008;78(4):271-283. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu X, Grosseto Nardini HK, Ruger JP. Micro-costing studies in the health and medical literature: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2014;3:47. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trussell J, Lalla AM, Doan QV, Reyes E, Pinto L, Gricar J. Cost effectiveness of contraceptives in the United States. Contraception. 2009;79(1):5-14. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trussell J, Hassan F, Lewin J, Law A, Filonenko A. Achieving cost-neutrality with long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Contraception. 2015;91(1):49-56. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altman DG. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ. 1998;317(7168):1309-1312. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trussell J, Henry N, Hassan F, Prezioso A, Law A, Filonenko A. Burden of unintended pregnancy in the United States: potential savings with increased use of long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2013;87(2):154-161. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu G, Kong L, Leslie DL, Corr TE. A longitudinal healthcare use profile of children with a history of neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Pediatr. 2019;204:111-117.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . National Health Expenditure Data. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/

- 32.Lino M, Kuczynski K, Rodriguez N, Schap T. Expenditures on Children by Families, 2015. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/crc2015_March2017.pdf

- 33.Child Care Resource. Chittenden County Child Care Statistics. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://www.childcareresource.org/for-everyone/chittenden-county-child-care-statistics/

- 34.Kolbe T, Kieran K. Study of Vermont State Funding for Special Education: Executive Summary. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://legislature.vermont.gov/assets/Legislative-Reports/edu-legislative-report-special-education-funding-study-executive-summary-and-full-report.pdf

- 35.Lucke JC, Hall WD. Under what conditions is it ethical to offer incentives to encourage drug-using women to use long-acting forms of contraception? Addiction. 2012;107(6):1036-1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03699.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gold RB. Some lawmakers continue to promote contraceptive use in return for welfare. State Reprod Health Monit. 1995;6(1):3–, 6.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Project Prevention . http://www.projectprevention.org. Accessed March 1, 2021.

- 38.Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101(2):192-203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive . Treatment episode data set: admissions 2018. (TEDS-A-2018).Accessed March 1, 2021. https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/study/treatment-episode-data-set-admissions-teds-2018-nid19019

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods. Additional Methods

Data Sharing Statement