Abstract

This survey study investigates how local staff at a partner facility perceived the role of international visiting health care workers and the impact of hosting international workers on the facility and staff.

Current literature documents significant surgical trainee interest in global surgery rotations, trainees’ motivations for seeking international opportunities,1 and how international experiences shape career aspirations.2 Global surgery rotations have proliferated in residency programs to meet these interests, and studies have documented benefits with these rotations in low-resource settings.3 However, it is critical to evaluate how local staff at partner facilities perceive visitors’ roles and contributions to avoid misperceptions and optimize mutually beneficial partnerships—a topic that has not been extensively investigated. Our study evaluated how local staff at a partner facility perceived the role of visitors and the impact of hosting international health care workers on the facility and staff.

Methods

A Qualtrics survey was designed, site tested, revised, and distributed to all clinical and administrative staff at a rural mission hospital in Kenya in August and September 2020. The survey included open- and closed-ended questions on demographic characteristics; the perceived benefits, motivation, and roles of visitors (students, surgical residents, or surgical attending physicians); challenges faced by visitors; and suggestions for enhancing this experience. Quantitative survey data were analyzed descriptively; qualitative data were analyzed thematically to identify dominant themes using the constant comparative method.4 Responses in the thematic analysis reflect the language used by participants with respect to racial or ethnic groups. This study was reviewed and approved by the Wright State University institutional review board. The survey was anonymous and voluntary, and thus met the institutional review board requirements for waiver of informed consent.

Results

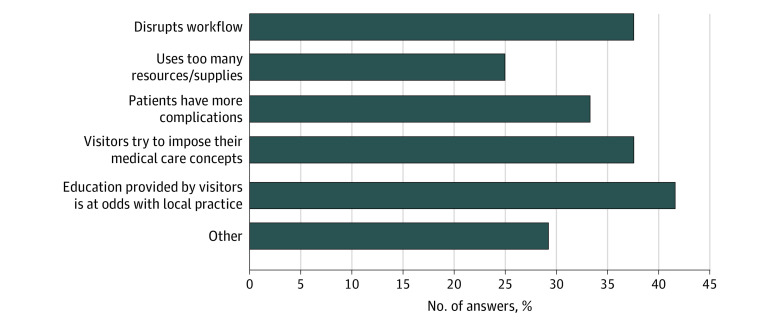

Of 119 total staff, 76 (63.9%) responded to the survey, 42 of whom (55.3%) were male, and 40 of whom (52.6%) were clinical workers. The mean (SD) age was 37.4 (11.4) years. Respondents answered different questions based on their answers to early questions. Sixty of 61 respondents (98.4%) agreed that visitors provided benefits to the host facility, primarily in the areas of education and research (50 of 61 [82.0%]) and clinical care (46 of 61 [75.4%). However, some respondents (24 of 57 [42.1%]) also perceived negative effects, including visitors providing education that did not match local practices (10 of 24 [41.7%]), the imposition of medical care concepts (9 of 24 [37.5%]), disturbance of workflow (9 of 24 [37.5%]), and higher patient complication incidence (8 of 24 [33.3%]) (Figure). Staff perceived different primary motivations for visitors: medical students were perceived to be interested in learning about diseases not seen in their home countries (37 of 65 [56.9%]), residents in helping people in need (32 of 65 [49.2%]), and surgeons in performing procedures not commonly done (34 of 65 [52.3%]). Staff perceived that visitors faced obstacles, including accommodations, language barriers, and working with limited medical supplies and resources. Staff suggested that their experiences with visitors could be improved if visitors were to keep an open mind for better cross-cultural teamwork and not display biases against African individuals or medical training in Africa (Table). Further improvements suggested were communicating clear clinical expectations to visitors and providing them with adequate time on site along with increased interaction with local staff (Table).

Figure. Perceived Negative Impact of International Visitors on Host Facility.

Table. Themes Emerging From Thematic Analysis of Qualitative Data.

| Theme | Description | Representative examples of respondents’ comments |

|---|---|---|

| What obstacles do you believe visitors have in providing care at your hospital? | ||

| Language and/or cultural barrier(s) | Barriers in terms of language and overall culture of the international host facility | “Language barrier and inability to understand the culture of the nearby community.” |

| “Cultural ways of communication.” | ||

| Limited resources | Lack of optimal resources available to visitors, including diagnostic tests, equipment, personnel, and finances | “Inadequate resources: manpower, money, and supplies.” |

| “Inadequate medical supplies at some point compromises the need to offer other medical services that aren’t offered at [this] hospital and also the infrastructure do affect the continuity and maintenance of care. Lack of enough medical specialist personnel in [this] hospital also inhibit the improvement of service delivery.” | ||

| Lack of clear directions, information, and expectations | Visitors were not fully aware of differences in medical practices, resources available to them, and expectations from the host facility | “It takes weeks for visitors to understand what the expectations of care are in the hospital.” |

| “Protocols/algorithms may be significantly different from their home institutions.” | ||

| How can we improve the experience of local staff with visitors? | ||

| Open-mindedness of visitors, teamwork, and professionalism | Visitors should be open to people of different races and ethnicities and should not use hurtful racial statements; moreover, visitors should be open to learning from the local medical staff, trust their training and ability, and accept feedback positively | “I suggest visitors to appreciate Africans and to understand that we are well trained and anything done should not be based on color.” |

| “They believe that America is superior to African, thus hindering their ability to learn from a Black or African colleague.” | ||

| “Visitors especially surgeons should cooperate with us and trust our ability.” | ||

| Opportunities for visitors to learn culture and language and have increased interaction with local staff | Visitors should learn culture and language for improved communication, and should interact more with local staff | “Introduction of social activity for example basketball, football, and music in order to make the visitors interact more staff.” |

| “Let visitors understand about Africa by getting more information about Africa as much as possible.” | ||

| “Teach them Swahili language which is national and mostly all people understand.” | ||

| Provision of housing, transportation, and resources to visitors | Providing housing, transportation, medical supplies, and equipment to help visitors and improve their experience | “Providing required resources for their [visitors’] practice in the facility, means of transportation, and good housing.” |

| “Provision of enough medical supplies and equipment will aid in the smooth running of medical visitors thus improving the service delivery at [our] hospital.” | ||

| Clear direction and expectations for visitors | Visitors should get clear direction and expectations from the host facility and should actively participate in learning | “They [visitors] must be provided with a scheme of work so that they run their duties without difficulties.” |

| “Awarding the visitors enough time for them to learn more within the hospital and the community at large.” | ||

| System-level changes and longer stay for visitors | Some system-level changes, including bidirectional global health and longer stay for visitors, were suggested | “I suggest the visitors should consider initiating exchange program where local nurses and doctors can go work in different countries abroad to help gain experiences in well set facilities and encounter how quality care is given to patients in those countries.” |

| “More time for their [visitors’] stay to be provided.” | ||

Discussion

In this single-site study, local staff felt that visitors were beneficial to their facility in providing research and education opportunities and increasing clinical care capacity. However, more than 40% perceived a negative effect with visitors imposing their medical care concepts onto local practices. These findings corroborate previous work in Namibia where visitors’ application of their own medical practices, irrespective of local context, caused friction among local staff, visitors, and patients.5 Our study also demonstrates perceived workflow disruption and increase in patient complications.

A thematic analysis revealed perception of biases against African individuals and African medical training along with a need to train visitors in local culture and language and provide them with clear directions and expectations. This suggests that medical institutions sending trainees and surgeons abroad could consider including pretrip workshops to discuss expectations, cultural competencies, variation in medical care concepts, implicit biases, and the importance of adhering to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies of professionalism.6 Open and clear communication from facilities to visitors about expectations, effective teamwork, and local resources as well as increased opportunities for interaction between visitors and local staff could improve the experience for all parties as well as patient care. While our study provides valuable information on the perception of the host facility, it is limited in including only one institution data and a relatively small sample size. Our findings warrant further research into the impact of visitors on patient care and continuity after visitors leave the hosting facility.

References

- 1.Powell AC, Casey K, Liewehr DJ, Hayanga A, James TA, Cherr GS. Results of a national survey of surgical resident interest in international experience, electives, and volunteerism. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(2):304-312. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston PF, Scholer A, Bailey JA, Peck GL, Aziz S, Sifri ZC. Exploring residents’ interest and career aspirations in global surgery. J Surg Res. 2018;228:112-117. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.02.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry JA, Groen RS, Price RR, et al. The benefits of international rotations to resource-limited settings for U.S. surgery residents. Surgery. 2013;153(4):445-454. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor SJ, Bogdan R. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resources. 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kraeker C, Chandler C. “We learn from them, they learn from us”: global health experiences and host perceptions of visiting health care professionals. Acad Med. 2013;88(4):483-487. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182857b8a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoehn RS, Davis BR, Huber NL, Edwards MJ, Lungu D, Logan JM. A systematic approach to developing a global surgery elective. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(4):e15-e20. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]