Abstract

BACKGROUND

The use of herbal supplements and alternative medicines has been increasing in the last decades. Despite popular belief that the consumption of natural products is harmless, herbs might cause injury to various organs, particularly to the liver, which is responsible for their metabolism in the form of herb-induced liver injury (HILI).

AIM

To identify herbal products associated with HILI and describe the type of lesion associated with each product.

METHODS

Studies were retrieved using Medical Subject Headings Descriptors combined with Boolean operators. Searches were run on the electronic databases Scopus, Web of Science, MEDLINE, BIREME, LILACS, Cochrane Library for Systematic Reviews, SciELO, Embase, and Opengray.eu. Languages were restricted to English, Spanish, and Portuguese. There was no date of publication restrictions. The reference lists of the studies retrieved were searched manually. To access causality, the Maria and Victorino System of Causality Assessment in Drug Induced Liver Injury was used. Simple descriptive analysis were used to summarize the results.

RESULTS

The search strategy retrieved 5918 references. In the final analysis, 446 references were included, with a total of 936 cases reported. We found 79 types of herbs or herbal compounds related to HILI. He-Shou-Wu, Green tea extract, Herbalife, kava kava, Greater celandine, multiple herbs, germander, hydroxycut, skullcap, kratom, Gynura segetum, garcinia cambogia, ma huang, chaparral, senna, and aloe vera were the most common supplements with HILI reported. Most of these patients had complete clinical recovery (82.8%). However, liver transplantation was necessary for 6.6% of these cases. Also, chronic liver disease and death were observed in 1.5% and 10.4% of the cases, respectively.

CONCLUSION

HILI is normally associated with a good prognosis, once the implied product is withdrawn. Nevertheless, it is paramount to raise awareness in the medical and non-medical community of the risks of the indiscriminate use of herbal products.

Keywords: Herb-induced liver injury, Drug induced liver injury, Dietary supplements, Herbal hepatotoxicity, Liver transplantation

Core Tip: The use of herbal supplements has been increasing in the last decades. Despite popular belief that natural products are harmless, they might cause herb-induced liver injury (HILI). This study aimed to identify herbal products associated with HILI. The search strategy retrieved 5918 references. In the final analysis, 446 references were included, with a total of 936 cases reported. We found 79 types of herbs related to HILI. Most of these patients had complete clinical recovery (82.8%). However, liver transplantation was necessary for 6.6% of these cases. Also, chronic liver disease and death were observed in 1.5% and 10.4%, respectively.

INTRODUCTION

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is the term used to describe liver test abnormalities and liver dysfunction caused by various medications[1]. In the last decades, the use of herbal supplements, natural products, and alternative medicines has risen considerably, which is consistently underreported by patients[2-4]. Despite popular belief that the consumption of natural products is harmless, herbs might cause injury to various organs. This is true particularly to the liver, which is responsible for their metabolism[2]. Even in the absence of data that substantiates safety or efficacy, the market of herbal and alternative medicines has greatly expanded, reaching up to US$83.1 billion in 2012[5]. Herb-induced liver injury (HILI) is a term currently used to describe liver injury related to herbal medicines, which both physicians and patients should be aware.

Unlike conventional medicines, herbal products generally have multiple compounds. This makes their pharmacological characteristics and safety unclear[6]. Most patients use them for general health improvement, health maintenance, and weight loss[7]. HILI manifestations can vary depending on the causing product, ranging from asymptomatic cases with increased transaminases to fulminant liver failure, resulting in liver transplantation or death[8,9]. Some assessment scores can improve the diagnostic process, which is frequently unclear.

The purpose of the present study is to identify herbal products associated with liver injury and describe the type of lesion associated with each product. A systematic review was conducted by searching published studies regarding HILI cases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations contained in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines[10]. Our systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), maintained by York University (CRD42020190931).

Data sources

Studies were retrieved using the terms described in the Appendix. Searches were run in June 2020 on the electronic databases Scopus, Web of Science, MEDLINE (PubMed), BIREME (Biblioteca Regional de Medicina), LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature), Cochrane Library for Systematic Reviews, SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online), Embase, and Opengray.eu. Languages were restricted to English, Spanish, and Portuguese. There was no date of publication restrictions. The reference lists of the retrieved studies were submitted to manual search.

Inclusion criteria and outcomes

Clinical case reports or case series involving herbal drug use and hepatotoxicity were included in the study. Studies were excluded if they were not a case reports or a case series or if they were not related to the topic. If there was more than one study published using the same case, the variables were complemented with both articles. Studies published only as abstracts were included, as long as the data available made data collection possible. The outcome measured was recovery, chronic liver disease, or death.

Study selection and data extraction

The search terms used for each database are described in the Appendix. An initial screening of titles and abstracts was the first stage to select potentially relevant papers. The second step was the analysis of the full-length papers. In this step, some studies were removed for lack of clinical information. Two independent reviewers extracted data using a standardized data extraction form after assessing and reaching consensus on eligible studies. The same reviewers separately assessed each study and extracted data about the characteristics of the subjects and the outcomes measured. The variables collected were demographic data, herbs used, clinical presentation, liver function tests, biopsy results, comorbidities, comedications, and treatment. Other variables assessed were: Temporal relationship between drug intake and onset of symptoms; exclusion of alternative causes of liver injury such as viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, biliary tract obstruction, pre-existing liver disease, pregnancy and acute hypotension; extra-hepatic manifestations such as rash, fever, arthralgias, eosinophilia, and cytopenia; intentional or accidental reexposure to the herb; and previous report in the literature of cases of HILI in accordance with Maria and Victorino System of Causality Assessment in Drug Induced Liver Injury[11] for posterior score computation. A third party was responsible for divergences in study selection and data extraction, clearing them when required.

Data management and statistical analysis

The patterns of liver injury were classified using R-value, which is defined as the number of times above the upper limit of normal (ULN) of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) divided by the number of times above the ULN of serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP). R equal or greater than 5 was defined as hepatocellular HILI, while a R under 2 was defined as cholestatic HILI, and a R between 2 and 5 was defined as "mixed". When the liver function tests were insufficient or other patterns had been established via histology (steatosis, granulomatous hepatitis, ductopenia, sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, veno-occlusive disease), lesions were classified using data from both biopsy and clinical manifestations. When the data was insufficient to classify the lesion, it was defined as not typeable. The Maria and Victorino score was completed with available data. When the information was insufficient, it was considered as the minimum possible score. Simple descriptive statistics, such as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), frequency, and median were used to characterize the data. Data were summarized using RStudio (version 4.0.2).

RESULTS

Systematic review

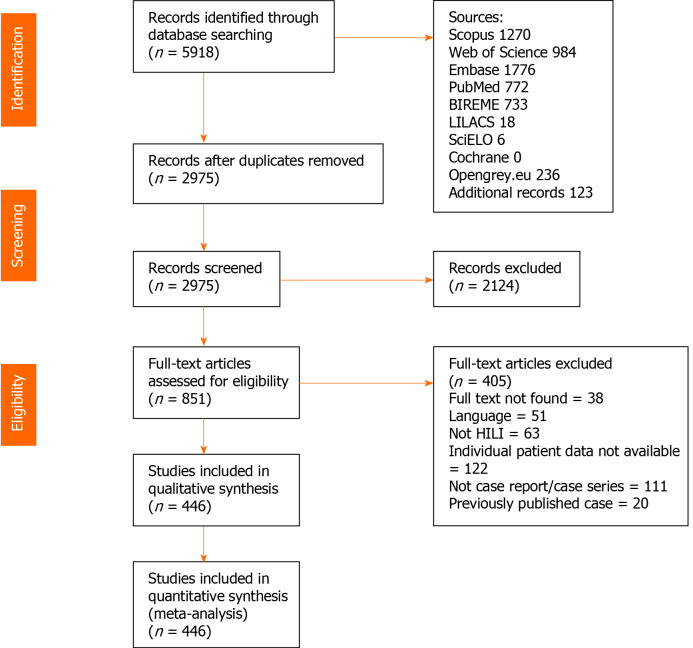

Using the search strategy, 5918 references were found, and 2943 references were excluded because they were duplicates. After analyzing titles and abstracts, 2124 references were excluded, and 851 full-text papers were analyzed. In the final analysis, 446 references were included, including 936 cases. A flowchart illustrating the search strategy is shown in Figure 1. Studies included were either case reports or case series.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart. HILI: Herb-induced liver injury.

Case reports from the United States, Germany, China, Spain, and Italy were the most common (27%, 11%, 8.3%, 6.2%, and 5.3%, respectively). A total of 936 patients were included, corresponding to 611 (65.2%) females. Every patient had used some type of herb or herbal product. It was found that 79 different types of herbs and herbal products induced liver injury. In 54 (4.9%) patients, it was not possible to identify the herb that was used. These data are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The prevalence of herbs or herbal compounds found in the systematic review

| Variable |

Patients, n = 936 (%) |

| Number of herbs per case | |

| One | 823 (87.9) |

| Two | 87 (9.2) |

| Three | 17 (1.8) |

| Four | 9 (0.9) |

| Herbs | 1084 (100) |

| He-Shou-Wu | 91 (8.3) |

| Green tea extract | 90 (8.3) |

| Herbalife | 64 (5.9) |

| Kava kava | 62 (5.7) |

| Greater celandine | 48 (4.4) |

| Multiple herbs | 38 (3.5) |

| Germander | 35 (3.2) |

| Hydroxycut | 35 (3.2) |

| Skullcap | 35 (3.2) |

| Kratom | 33 (3.0) |

| Gynura segetum | 29 (2.6) |

| Garcinia cambogia | 29 (2.6) |

| Ma huang | 27 (2.4) |

| Chaparral | 26 (2.4) |

| Senna | 25 (2.3) |

| Aloe vera | 22 (2.0) |

| Jin Bu Huan | 19 (1.7) |

| Oxyelite | 17 (1.5) |

| Valerian | 16 (1.4) |

| Red Yeast Rice | 16 (1.4) |

| Black Cohosh | 15 (1.3) |

| Noni | 14 (1.2) |

| Senecio | 14 (1.2) |

| Turmeric | 13 (1.2) |

| Dictamnus dasycarpus | 12 (1.1) |

| No-xplode | 12 (1.1) |

| St. John’s Wort | 12 (1.1) |

| Black catechu | 11 (1) |

| LipoKinetix | 11 (1) |

| Others | 159 (14.6) |

| Ginseng | 10 (6.2) |

| Pennyroyal oil | 9 (5.6) |

| Cascara-Sagrada | 9 (5.6) |

| Ashwagandha | 9 (5.6) |

| Atractylis gummifera | 8 (5) |

| Comfrey | 8 (5) |

| Psoralea corylifolia | 8 (5) |

| Field Horsetail | 7 (4.4) |

| Citrus aurantium | 7 (4.4) |

| Equinácea | 6 (3.7) |

| Heliotropium | 5 (3.1) |

| Saw palmetto | 5 (3.1) |

| Syo-saiko-to | 5 (3.1) |

| Ba Jiao Lian | 4 (2.5) |

| Crotalaria | 3 (1.8) |

| Impila | 3 (1.8) |

| Mistletoe | 3 (1.8) |

| Erva-mate | 3 (1.8) |

| Kombucha tea | 3 (1.8) |

| Soy isoflavones | 3 (1.8) |

| Centella asiática | 3 (1.8) |

| Red Bush tea | 3 (1.8) |

| Milk thistle | 3 (1.8) |

| Mentha piperita | 2 (1.2) |

| Tussilago farfara | 2 (1.2) |

| Aesculus hippocastanum | 2 (1.2) |

| Tinospora crispa | 2 (1.2) |

| Malva | 2 (1.2) |

| Margosa oil | 2 (1.2) |

| Nerium oleander | 1 (0.6) |

| Chinese Herbal Medicine | 1 (0.6) |

| Maya nut | 1 (0.6) |

| Eucalyptus globulus | 1 (0.6) |

| Pelargonium sidoides | 1 (0.6) |

| Lesser celandine | 1 (0.6) |

| Kudzu root extract | 1 (0.6) |

| Grifola frondosa | 1 (0.6) |

| Adenostyles alliariae | 1 (0.6) |

| Argemone Mexicana | 1 (0.6) |

| Willow bark tea | 1 (0.6) |

| Pioscoreae rhizome | 1 (0.6) |

| Green coffee | 1 (0.6) |

| Chamomile | 1 (0.6) |

| Chaga tea | 1 (0.6) |

| Yang ti cao | 1 (0.6) |

| Orthosiphon aristatus | 1 (0.6) |

| Solanum nigrum | 1 (0.6) |

| Mango | 1 (0.6) |

| Isabgol | 1 (0.6) |

| Unknown | 54 (4.9) |

Age ranged from 3-d-old to 88-year-old (mean age was 42 years). Of all patients, 823 (87.9%) ingested only one type of herb with known potential for liver injury. Only 9 (0.9%) patients used four herbs that had known potential for liver injury at the same time. The most prevalent herbs and herbal products were He-Shou-Wu, green tea extract, Herbalife, kava kava, and greater celandine (8.3%, 8.3%, 5.9%, 5.7%, 4.4%, respectively). The most common reasons to use these products were weight loss, psychiatric disorders, and pain control (25.6%, 9.2%, 8.1%, respectively). A previous report of liver injury by the implied herb was described in 855 cases (98.1%). The summary results can be found in Table 2, which is detailed in the supplementary material (Appendix 1 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Baseline features of herb-induced liver injury in 936 patients

| Variable |

Patients, n = 936 (%) |

| Mean age (yr) | 42.67 |

| Sex (female) | 611 (65.2) |

| Race | |

| White | 82 (8.7) |

| Black | 9 (0.9) |

| Other | 53 (5.6) |

| Country | |

| United States | 253 (27) |

| Germany | 103 (11) |

| China | 78 (8.3) |

| Spain | 58 (6.2) |

| Italy | 50 (5.3) |

| South Corea | 40 (4.2) |

| Others | 354 (37.8) |

| Application | |

| Weight loss | 145 (15.4) |

| Psychiatry disorders | 52 (5.5) |

| Pain control | 46 (4.8) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 41 (4.3) |

| Skin problems | 37 (3.7) |

| Health improvement | 34 (3.6) |

| Physical improvement | 34 (3.6) |

| Sleep disorders | 24 (2.5) |

| Symptoms | |

| Jaundice | 437 (46.3) |

| Abdominal pain | 212 (22.4) |

| Nausea | 163 (17.2) |

| Hepatomegaly | 131 (13.8) |

| Fatigue | 131 (13.8) |

| Urine alteration | 127 (13.4) |

| Coluria | 120 (12.7) |

| Hematuria | 7 (0.7) |

| Vomiting | 117 (12.4) |

| Ascites | 104 (11) |

| Pruritus | 84 (8.9) |

| Stools alteration | 57 (6) |

| Clay colored | 53 (5.6) |

| Melena | 4 (0.4) |

| Anorexia | 49 (5.1) |

| Encephalopathy | 39 (4.1) |

| Asthenia | 34 (3.6) |

| Malaise | 33 (3.5) |

| Diarrhea | 33 (3.5) |

| Abdominal distension | 30 (3.1) |

| Weakness | 27 (2.8) |

| Fever | 22 (2.3) |

| Lethargy | 19 (2) |

| Hyporexia | 19 (2) |

| Splenomegaly | 17 (1.8) |

| Myalgia | 14 (1.4) |

| Altered mental status | 14 (1.4) |

| Weight loss | 13 (1.3) |

| Antibodies | |

| ANA | 48 (5) |

| ASMA | 25 (2.6) |

| AMA | 7 (0.7) |

| Anti-dsDNA | 2 (0.2) |

| cANCA | 2 (0.2) |

| Actin | 1 (0.1) |

| Anti-LKM | 1 (0.1) |

| AMA-M2 | 1 (0.1) |

| pANCA | 1 (0.1) |

| Rheumatoid factor | 1 (0.1) |

| AST (U/L) | 1324 |

| ALT (U/L) | 1462 |

| ALP (U/L) | 283 |

| GGT (U/L) | 260 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 28.37 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 7.71 |

| HILI pattern | |

| Hepatocellular | 660 (70) |

| Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome | 92 (9.7) |

| Cholestatic | 80 (8.5) |

| Mix | 78 (8.3) |

| Granulomatous hepatitis | 6 (0.6) |

| Steatosis | 5 (0.5) |

| Ductopenia | 3 (0.3) |

| Nontippable | 2 (0.2) |

| Other | 10 (1) |

| Use duration (d) | 125 |

| Latency (d) | 121 |

| Stop and manifestation (d) | 1 |

| Normalization liver function (d) | 77 |

| Comorbidities | |

| Dyslipidemia | 40 (4.2) |

| Obesity | 37 (3.9) |

| Hypertension | 36 (3.8) |

| Alcohol use | 26 (2.7) |

| Hypothyroidism | 26 (2.7) |

| Osteoarthritis | 13 (1.3) |

| Psoriasis | 10 (1) |

| Anxiety | 9 (0.9) |

| Asthma | 9 (0.9) |

| Depression | 9 (0.9) |

| Smoking | 7 (0.7) |

| None | 350 (37.1) |

| Other medications | |

| Vitamins and minerals | 63 (6.6) |

| Antihypertensive | 53 (5.6) |

| NSAIDs | 45 (4.7) |

| Estrogen/progesterone | 40 (4.2) |

| Diuretics | 23 (2.4) |

| Paracetamol | 23 (2.4) |

| Statins | 23 (2.4) |

| SSRI | 17 (1.8) |

| Antibiotics | 15 (1.6) |

| Corticoid | 15 (1.6) |

| Benzodiazepine | 14 (1.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus drugs | 14 (1.5) |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 12 (1.3) |

| None | 452 (47.9) |

| Temporal relation | 26 (15.6) |

| Biopsy | 383 (40.5) |

| Viral hepatitis | |

| Hep A | 3 (0.4) |

| Hep B | 5 (0.6) |

| Hep C | 8 (0.9) |

| CMV | 2 (0.2) |

| HSV | 2 (0.2) |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 2 (0.2) |

| Bile duct obstruction | 2 (0.2) |

| Other causes | |

| Pregnancy | 3 (0.3) |

| Acute hypotension | 2 (0.2) |

| Rechallenge | 79 (8.3) |

| Previous report hepatotoxicity | 855 (88.5) |

| Causality | |

| Definitive | 22 (2.3) |

| Highly probable | 8 (0.8) |

| Probable | 122 (12.9) |

| Possible | 49 (5.1) |

| Improbable | 2 (0.2) |

| Excluded | 7 (0.8) |

| Maria and Victorino | |

| Treatment | 8.69 ± 3.93 |

| Supportive care | 699 (66.1) |

| Liver transplantation | 70 (6.6) |

| Corticoid | 39 (3.6) |

| Acetylcysteine | 29 (2.7) |

| Ursodeoxycholic acid | 28 (2.6) |

| Adenosylmethionine | 21 (1.9) |

| Glutathione | 20 (1.8) |

| Vitamin K | 18 (1.6) |

| Glycyrrhizin | 18 (1.6) |

| Polyene phosphatidylcholine | 18 (1.6) |

| Antibiotics | 17 (1.5) |

| Cholestyramine | 4 (1.1) |

| Outcome | |

| Recovery | 782 (82.8) |

| Chronicity | 14 (1.5) |

| Death | 98 (10.4) |

ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; GGT: Gamma-glutamyl transferase; Hep: Hepatitis; CMV: Cytomegalovirus; HSV: Herpes simplex virus.

The most common clinical presentation of the reviewed cases of HILI was jaundice, present in 437 (46.3%) cases, followed by abdominal pain and nausea (22.4% % and 17.2%, respectively). Hepatomegaly and fatigue were present in 131 (13.8%) patients, and 120 (12.7%) patients had choluria. Liver function and injury tests usually presented significant alterations. Overall aspartate aminotransferase and ALT were elevated approximately 22 and 28 times its respective ULN, and ALP was around two times elevated its normal range. Other liver marker results are described in Table 2.

Among all patients, a liver biopsy was performed in 383 (40.5%) cases. The most common pattern of HILI was hepatocellular, in 660 (70%) cases, followed by sinusoidal obstruction syndrome in 92 (9.7%) cases, and cholestatic in 80 (8.5%) cases. The mean time of herb use was 125 d with a median of 42 d. The mean time between drug use and start of the first clinical or laboratory manifestation was 121 d with a median of 42 d. The mean time to recovery was 77 d with a median of 60 d.

Dyslipidemia was the most frequent comorbidity, which was present in 40 (4.2%) cases, followed by obesity and hypertension (3.8% and 3.9%, respectively). Vitamins and minerals were utilized by 63 (6.6%) patients. Other commons drugs used were antihypertensives, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and progestin estrogen pills (5.6%, 4.7%, and 4.2%, respectively). The temporal relation between starting the co-medication and liver injury was positive only in 26 (15.6%) of 166 patients who used another drug. Viral hepatitis as a cause of liver injury was possible only in 20 cases; eight (0.9%) of them had a positive test for hepatitis C.

Rechallenge was positive in only 79 (8.3%) cases, whereas in 180 cases there was no available information. The mean Maria and Victorino System of Causality Assessment score was 8.69 (3.93, SD) and median 9, which indicates herbs as an unlikely cause for liver injury in overall reported cases. The most prevalent treatments consisted of supportive care (66.1%), such as herbal withdrawal and intravenous fluid replacement. Among patients who received some intervention, the treatments used were liver transplantation, corticoid, acetylcysteine, and ursodeoxycholic acid (6.6%, 3.6%, 2.7%, and2.6%, respectively). Complete recovery occurred in 782 (82.8%) of patients. Chronic liver disease and death were observed in 1.5% and 10.4% of the cases, respectively.

Subgroup analysis

Regarding the 14 most prevalent herbs (Table 3), He-Shou-Wu (Polygonum multiflorum) was the most prevalent with 91 cases reported and Jin Bu Huan (Lycopodium serratum) the least with 19 cases. Greater celandine (Chelidonium majus) and Kava (Piper methysticum) were more reported in Germany (81.2%, 65%, respectively) and He-Shou-Wu and Tusanqi (Gynura segetum) were more reported in China (54.9% and 75.8%, respectively). Green Tea extract (Camellia sinensis), skullcap (Scutellaria spp.), kratom (Mitragyna speciosa), garcinia cambogia (Garcinia gummi-gutta), ma huang (Ephedra sinica), chaparral (Larrea tridentata), and Jin Bu Huan were more reported in United States. The mean age was higher for skullcap and Tusanqi or Gynura segetum (54 years) cases and lower for Senna or Senna spp. (33 years) cases. Male patients were more likely to be affected by He-Shou-Wu and kratom (51.6% and 62%, respectively). Female patients comprised of 90.7% of the cases reported of HILI caused by garcinia cambogia.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the 14 main herbs that induced-liver injury

| Generic or trade names |

Latin name |

n

|

Age (mean) |

Sex (male) (%) |

Country/territory (%) |

Symptoms (%) |

AST (mean) |

ALT (mean) |

ALP (mean) |

GGT (mean) |

BT (mean) |

BD (mean) |

Biopsy (%) |

HILI patterns (%) |

Maira and Victorino score (mean) |

Treatment (%) |

Clinical outcome (%) |

| He-Shou-Wu; Fo-ti; Shou Wu Pian | Polygonum multiflorum | 91 | 46 | 47 (51.6) | China (54.9), South Korea (28.5) | Jaundice (80), choluria (17.7), fatigue (15.5), hepatomegaly (13.3) | 1279 | 1511 | 222 | 264 | 10.8 | 6.3 | 20 (31.7) | Hepatocellular (72.5), cholestatic (18.6), mixed (8.7) | 8 | Adenosylmethionine (12.3), glutathione (12.3), glycyrrhizin (12.3), polyene phosphatidylcholine (12.3), supportive care (45.8) | Recovery (93.4), chronification (3.3), died (3.3) |

| Green tea extract | Camellia sinensis | 90 | 44 | 22 (24.4) | Usa (32.5), Spain (19.1), Japan (14.6) | Jaundice (61.4), fatigue (30.4), nausea (27.5), abdominal pain (26) | 1715 | 1870 | 330 | 271 | 12.8 | 9.2 | 36 (60) | Hepatocellular (78.8), cholestatic (8.8), mixed (11.1) | 9 | Liver transplantation (10.5), corticoid (9.4), acetylcysteine (3.1), supportive care (45.8), udca (3.1), supportive care (69.4) | Recovery (91.7), chronification (1.1), died (7) |

| Kava kava | Piper methysticum | 62 | 43 | 15 (24.1) | Germany (65), United States (21.6), Spain (3.3) | Jaundice (86.8), nausea (47.8), fatigue (34.7) | 1206 | 1605 | 310 | 284 | 19 | 10 | 36 (69.2) | Hepatocellular (77.4), cholestatic (9.6), mixed (8) | 8 | Liver transplantation (23.9), corticoid (4.2), suportive care (57.7) | Recovery (91.9), died (8) |

| Greater celandine | Chelidonium majus | 48 | 49 | 8 (17) | Germany (81.2), Italy (8.3) | Jaundice (34.2), choluria (31.4), pruritus (28.5), nausea (27.7) | 631 | 1109 | 321 | 236 | 11.5 | 6.9 | 34 (79) | Hepatocellular (72.9), cholestatic (6.2), mixed (20.8) | 10 | Udca (6.1), corticoid (4), glutathione (2), supportive care (87.7) | Recovery (97.9), died (2) |

| Germander | Teucriumchamaedrys | 35 | 49 | 11 (31.4) | France (28.5), Greece (22.8), United States (14.2) | Jaundice (77.1), nausea (17.1), choluria (17.1), abdominal pain (17.1) | 1091 | 1127 | 251 | 183 | 13.7 | 9.1 | 13 (40.6) | Hepatocellular (94.2), mixed (5.7) | 12 | Udca (15.7), vit K (13.1), liver transplantation (5.2), supportive care (65.7) | Recovery (97.1), died (2.8) |

| Skullcap | Scutellaria spp. | 35 | 54 | 9 (25.7) | United States (45.7), Australia (14.2), Scotland (11.4) | Jaundice (68), nausea (15.3), choluria (20) | 859 | 1234 | 227 | 359 | 14 | NA | 12 (67.7) | Hepatocellular (74.2), CHOLESTATIC (5.7), MIxed (14.2) | 9 | Liver transplantation (11.1), corticoid (2.7), udca (2.7), supportive care (77.7) | Recovery (85.7), died (14.2) |

| Kratom | Mitragyna speciosa | 33 | 36 | 20 (62) | United States (75), Canada (6.2), Sweden (6.2) | Jaundice (70), choluria (53.3), abdominal pain (43.5), nausea (23.3), fatigue (23.3) | 1125 | 957 | 304 | 258 | 11.7 | 11.3 | 11 (39.2) | Hepatocellular (45.4), cholestatic (27.2), mixed (21.2) | 11 | Acetylcysteine (12.7), udca (7.6), corticoid (5.1), liver transplantation (5.1), supportive care (48.7) | Recovery (90.6), died (9.3) |

| Tusanqi or Jusanqi | Gynura segetum | 29 | 54 | 14 (48.2) | China (75.8), Hong Kong (20.6), New Zeeland (3.4) | Ascites (100), hepatomegaly (86.9), jaundice (26) | 469 | 460 | NA | NA | 1 | 0.5 | 1 (50) | Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (100) | 4 | Glutathione (6.6), antibiotics (6.6), furosemide (6.6), supportative care (80) | Recovery (50), chronification (22.2), died (27.7) |

| Garcinia cambogia; Malabar tamarind | Garcinia gummi-gutta | 29 | 45 | 3 (10.3) | United States (39.2), Italy (35.7) | Abdominal pain (56), jaundice (44), nausea (40), vomiting (24), fatigue (16) | 1918 | 1927 | 243 | 249 | 10.9 | 7.5 | 12 (50) | Hepatocellular (86.2), cholestatic (10.3), mixed (3.4) | 10 | Liver transplantation (20.6), acetylcysteine (10.3), corticoid (3.5), supportive care (65.5) | Recovery (96.6), died (3.4) |

| Ma huang | Ephedra sinica | 27 | 44 | 8 (32) | United States (68), South Korea (12), United Kingdom (8) | Abdominal Pain (72.7), nausea (63.6), jaundice (54.5), fatigue (45.4), hepatomegaly (36.3) | 3173 | 2092 | 188 | 161 | 12.5 | NA | 10 (55.5) | Hepatocellular (96), mixed (4) | 9 | Liver transplantation (19.2), corticoid (3.8), urine alkalization (3.8), hemodialysis (3.8), diuretics (3.8), suportive care (65.3) | Recovery (92), died (8) |

| Chaparral | Larrea tridentata | 26 | 44 | 9 (34.6) | United States (80.7), Australia (7.6), Canada (7.6) | Jaundice (84), abdominal pain (40), fatigue (36), nausea (28), pruritus (24) | 1300 | 1081 | 189 | 317 | 17.7 | 9.6 | 10 (43.4) | Hepatocellular (84.6), steatosis (15.3) | 11 | Corticoid (7.6), liver transplantation (7.6), vit K (3.8), supportive care (80.7) | Recovery (92.3), died (7.6) |

| Senna; Sene | Senna spp. | 25 | 33 | 5 (21.7) | India (24), Italy (16), Yemen (16) | Jaundice (43.4), abdominal pain (34.7), encephalopathy (20), asthenia (20), choluria (13) | 1637 | 1688 | 477 | 128 | 7.4 | 5.1 | 7 (50)) | Hepatocellular (84), cholestatic (4), mixed (12) | 10 | Antibiotics (9.6), vit K (12.9), lactulose (6.4), liver transplantation (3.2), acerylcysteine (3.2), supportive care (58) | Recovery (81.8), died (18.1) |

| Aloe Vera | Aloe vera | 22 | 50 | 5 (22.7) | South Korea (18.1), Spain (9), Usa (9) | Abdominal pain (50), jaundice (40.9), fatigue (31.8), nausea (27.2) | 1762 | 1300 | 414 | 167 | 10.1 | 8.7 | 11 (52.3) | Hepatocellular (86.3), cholestatic (4), mixed (9) | 11 | Antibiotics (4.1), liver transplantation (4.1), vit K (4.1), hemodialysis (4.1), supportive care (75) | Recovery (85.7), chronification (4.7), died (9.5) |

| Jin Bu Huan | Lycopodium serratum | 19 | 46 | 2 (10.5) | United States (73.6), Canada (10.5), Italy (10.7) | Fatigue (52.6), hepatomegaly (42.1), pruritus (36.8), jaundice (31.) | 596 | 1057 | 231 | 185 | 7.5 | NA | 6 (40) | Hepatocellular (84.2), cholestatic (5.2), mixed (10.5) | 13 | Cholestyramine (15.7), supportive care (84.2) | Recovery (100) |

ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; GGT: Gamma-glutamyl transferase; BT: Total bilirubin; BD: Direct bilirubin; NA: Not available; UDCA: Ursodeoxycholic acid.

Jaundice was the most prevalent symptom for all herbs. Kava had the higher prevalence of jaundice (86.8%). Ascites was present in all cases of Tusanqi (100%). These data are summarized in Table 3. Ma huang cases presented the highest mean values of aspartate aminotransferase and ALT (3173 UI/L and 2092 UI/L, respectively) and Tusanqi the lowest (469 UI/L, 460 UI/L, respectively). Senna cases presented the highest mean values of ALP (477 UI/L) and Ma huang the lowest (188 UI/L). Mean total bilirubin was increased in all herbs other than Tusanqi. Of the 14 most prevalent herbs, 13 had a predominant hepatocellular pattern of hepatic injury. Every Tusanqi case presented sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (100%).

As for Maria & Victorino score, the highest mean score was 13 (possible) in Jin Bu Huan and the smallest was 4 in Tusanqi. Kava kava patients had the highest liver transplantation rates (23.9%), follow by garcinia cambogia and ma huang (20.6% and 19.2%, respectively). The supportive care was herbal withdrawal and fluid replacement, and symptomatic treatment were adopted in the most cases. Recovery rate was more than 85% for almost all herbs, except in Tusanqi and Senna (50% and 81.8%, respectively). The mortality rate was higher for Tusanqi (27.7%), follow by senna and skullcap (18.1%, 14.2%). Besides that, 22.2% of the cases of HILI caused by Tusanqi developed chronic liver disease. These data are further detailed in the Supplementary Material.

DISCUSSION

Herbal and dietary supplements are commonly used for both specific health improvement and specific illnesses[3]. Although they might seem harmless, most patients are unaware of the consequences of the use of herbs or herbal derivates[12-14], as are many health professionals[15-17]. Herbs generally demand a higher metabolism of the liver, especially in compounds, which might cause HILI[6,18]. Furthermore, for the majority of these supplements, the incidence of adverse effects, toxic constituents, mechanism of action, and pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and histological patterns are unclear[3]. Therefore, it is difficult to recommend and monitor these products safely.

Host-related risk factors for DILI include age, sex, daily dose, metabolism profile, and drug interactions[19]. In our systematic review, females represented 65.2% of all cases, and they were more affected by liver injury than men. This has been previously described in the literature and might be associated with a higher use of these products by women[20,21]. Recent reports have emphasized the higher incidence of liver injury in patients over 40 years-old, increasing along with age[2], as seen in our results. The concomitant use of other drugs was low (only 166 patients of 936 cases), and the temporal relationship between drug exposure and the start of manifestations was positive in only 26 cases. The most common comorbidities found in the review were dyslipidemia, obesity, and hypertension. Besides, alcohol use and smoking were reported in only a few cases, 26 and 7 patients, respectively. The relationship among comorbidities and HILI prognosis needs to be further investigated in prospective studies.

The daily dose and metabolism profile were not evaluated by most articles. In only 3 cases the route of administration of the herb was not oral. In a 6-mo-old infant, an enema prepared from the roots of an unknown herb was given, and the child died[22]. A previously healthy 22-year-old woman used suppositories made of a mixture of unidentified plants, culminating in death 72 h after hospital admission[23]. Also, a 40-year-old woman received five injections of an aqueous solution of mistletoe and presented elevated liver tests, the outcome was not reported[24].

Despite the wide spectrum of herbal drugs or products, the median time from starting the herb to the onset of HILI was between 21 and 90 d, similarly to what has been described in the literature[21,25]. Normalization of liver function occurred in a mean of 77 d. In severe cases, death occurred only a few days after hospitalization due to fulminant liver failure. The development of chronic liver disease was reported only in 1.5% of cases, a smaller rate than other studies[26,27].

The clinical manifestations and the diagnosis are similar to DILI. However, patients must often be persuaded into revealing a history of herbal use, since most of them do not think of these supplements as medications with potential risks[2,7]. Clinical symptoms of HILI vary significantly. Lots of HILI patients might be asymptomatic with mild biochemical liver abnormalities[2,3,25]. In our findings, patients frequently presented with fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. In more severe cases, cholestatic symptoms such as jaundice, pruritus, clay-colored stools, and dark urine were present. These clinical manifestations are similar to the ones reported in DILI[28,29].

To clarify data and assess causality, the Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Model[30] and Maria and Victorino System of Causality Assessment[11] can be used. We assessed causality in our systematic review using Maria and Victorino because it has other clinical elements, and it is more simple than other assessments of causality. The overall Maria and Victorino score findings were low, which could translate into unlikely causality (mean 8.69 ± 3.93 SD). However, most case reports that classified a herb an unlikely cause for HILI did not provide sufficient data. Therefore, these results might not be completely accurate. In addition, authors often evaluated the causality of cases as certain, very likely, or likely but did not present the data used in this assessment[31-34].

DILI and HILI lesion patterns are generally classified into hepatocellular, cholestatic, and mixed based on pathological features[35]. These three types can be evaluated using an R-value, which is defined as the number of times above the ULN of serum ALT divided by the number of times above the ULN of serum ALP. R equal to or greater than 5 was defined as hepatocellular HILI, while a R under 2 was defined as cholestatic HILI, and a R between 2 and 5 was defined as "mixed"[25]. Although liver histology tends to have a small impact on establishing the diagnosis of HILI[36], it was performed in 383 (40.9%) cases. We found the following patterns: Hepatocellular (70%), cholestatic (8.5%), mixed (8.3%), and sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (9.7%). The last one was the second most prevalent type, and it is an obliterative inflammation of the terminal hepatic venules. In more severe forms, this carries a higher risk for mortality[37].

Moreover, it is important to note that HILI is often self-limited. Nevertheless, chronic hepatic liver disease, acute liver failure, death, and liver transplantation are commonly related repercussions[2,28]. Between 2% and 10% of reported cases of liver failure in Spain have been attributed to herbal products or dietary supplements[38]. In the United States, herbal or dietary supplement use was the fourth leading cause of DILI requiring liver transplantation[39]. In our systematic review, 70 cases (6.6% of patients who needed medical intervention) had acute liver failure and underwent liver transplantation. In addition, we found an elevated overall mortality of 10.4%. This was almost three times higher than the mortality or liver transplantation rate of 4.1% reported by Zhu et al[27] or the 3.2% reported by a retrospective study with 1985 patients[40]. However, such difference might be explained in our study due to publication bias, since severe cases are more likely to be reported and published. Despite the elevated mortality rate, 782 (82.8%) patients recovered, and only 14 (1.5%) developed chronic liver disease.

Subgroup analysis

Polygonum multiflorum : Polygonum multiflorum, also known as He-Shou-Wu or Fo-ti, was our most prevalent herb. In China it is the most common cause of HILI[41]. It is mainly used as a hair supplement and to improve insomnia and coordination. Liver injury was more frequently reported in middle-aged men (51.6%) without significant risk factors; the ingest dose usage varied from 3 g/d to 20 g/d[42] with the first clinical or laboratory manifestation occurring approximately 58 d after the start of the herbal product. Some reports include benefits for headaches, dizziness, graying of the hair, constipation, and liver disease[41,43]. The onset of symptoms was normally short, around a month, with a good resolution after discontinuation of the product[44]. The main symptoms included jaundice, choluria, fatigue, anorexia, and hepatomegaly[42,44]. The most common lesion was hepatocellular followed by cholestatic, differing from the literature that includes mixed as the second most common pattern[41,44]. The mechanism of injury is probably immunologically mediated[41,45]. Rechallenge can help confirm the diagnosis but is not recommended[46,47]. In most cases, the withdrawal of the herb was enough to resolve symptoms[48]. Normalization of liver tests typically occurred around 30 d after withdrawal of the herbal product. Corticosteroids should not be prescribed[41]. In our systematic review, the patients received adenosylmethionine, glutathione, glycyrrhizin, and polyene phosphatidylcholine. Their efficacy or improvement in outcomes is uncertain.

Camellia sinensis : Also known as green tea, it can be found in many herbal preparations, and it is consumed as a drink worldwide. The exact prevalence of symptomatic green tea extract induced acute liver injury is not entirely understood, but it is undoubtedly low in comparison to the wide-scale use of these products[49]. In our research, the mean age of green tea induced HILI was 44 years, with a significantly higher prevalence in women (78.6%), probably associated with a higher use of this herb by women. The onset of symptoms varied from 9 d to 120 d with 0.7 g/d to 3 g/d of extract[50]. In our review, most cases presented the first manifestation around 35 d after the first dose was used, with ingested doses varying from 400 mg/d to 1.8 g/d[51,52]. Obesity, overweight, and dyslipidemia were the most common comorbidities. The most common symptoms were jaundice, fatigue, nausea, and abdominal pain. Most patients recovered rapidly with the withdrawal of the herbal compound. Nevertheless, fatal cases of acute liver failure have been described[18,49]. The mechanism by which green tea may have such effects has not been entirely elucidated[49], but catechins such as epigallocatechin-3-gallate and epicatechin-3-gallate appear to be the main hepatotoxic components[18,51,53-55]. Toxicological studies suggest that green tea induced HILI has a hepatocellular pattern[56], as found in our study. Normalization of liver function tests occurred generally in a couple of months. The treatment includes withdrawal of the herb and corticosteroids in selected cases. In more severe cases, liver transplantation might be required[9,57].

Piper methysticum : Piper methysticum roots, also called kava kava, are used for preparation of a recreational and ceremonial drink in Oceania and are used to treat anxiety and insomnia[58]. People consuming kava kava have reported feeling more sociable, tranquil, and generally happy. The first alteration or liver function tests alteration typically occurred in 90 d. Liver injury was more prevalent in middle aged woman (75.9%). In our review, most cases presented the first manifestation around 35 d of the first ingestion, with doses varying from 50 mg/d to 1 g/d[59]. Clinical cases of kava induced HILI suggest idiosyncratic or immunoallergic reactions as cause for liver injury[60]. In our systematic review, the patients normally presented with jaundice, nausea, and fatigue, with elevation in serum aminotransferase and mild increase in alkaline phosphatase. Hepatocellular pattern was the most common type of HILI reported, followed by cases of cholestatic and mixed hepatitis, similar to previous reports in the literature[61]. In most instances, liver injury resolved within 1 mo to 3 mo after discontinuing kava kava. Although, if fulminant liver failure develops, a liver transplant might be necessary[8,60,62].

Chelidonium majus : Also known as greater celandine, it is usually used to treat gastrointestinal disorders and dyspepsia[62]. HILI was more prevalent in middle age women (83%) with ingested doses varying from 4 or 5 spoons of dried leaves in 150 mL of water to 600 mg per day in capsules[59]. Greater celandine associated HILI typically arises after 1 mo to 6 mo, causing jaundice, choluria, pruritus, and nausea, including moderate to marked elevations in serum aminotransferase levels[63]. The pattern of injury is usually hepatocellular and liver histology resembles acute viral hepatitis[64]. Immunoallergic mechanisms may trigger the injury[65]. Fatal cases after ingestion of greater celandine are rare and are generally associated with previous liver disease. Patients generally present a rapid recovery after discontinuation of the herb, and normalization of liver parameters occurred in approximately 60 d[63,64].

Teucrium chamaedrys : Also known as germander, it includes more than 250 species of plants in the mint family (genus: Teucrium). It is used for weight control and management of diabetes and hyperlipidemia[66]. Germander associated HILI generally started within 2 wk to 18 wk after the use of capsules or tea[66]. Ingested dose varied from two tablespoons to 1600 mg/d[67,68]. Higher prevalence occurred in middle-aged women (68.6%). The most common symptoms were jaundice, nausea, choluria, abdominal pain, and fatigue. The principal pattern of liver injury was hepatocellular[69]. Germander-induced HILI probably occurs due to both direct toxicity and secondary immune reactions, with a varying contribution of these two mechanisms in different patients[70]. The manifestations are usually self-limited once the herb is withdrawn; normalization of liver parameters occurred generally in a couple of months. However, ursodeoxycholic acid, vitamin K, and liver transplantation might be needed for therapy in severe cases[71].

Scutellaria spp. : The dried leaves and stems of Scutellaria spp., also known as skullcap, are used as a herbal extract or herbal tea to treat anxiety, stress, and insomnia[72]. Other indications are health improvement and pain management. The mechanism of skullcap induced HILI is not entirely known. In reported cases, the onset of symptoms and jaundice occurred within 1 wk to 12 wk, and the serum enzyme pattern was typically hepatocellular, followed by mixed hepatitis[72,73]. Ingested dose varied from 400 mg until 16 g daily[73,74]. In this review, the mean age of skullcap-induced HILI was 54-years-old with a significantly higher prevalence in women (74.3%). Other common symptoms included nausea and choluria. Osteoarthritis and hypertension were common problems reported by the patients. Skullcap induced HILI is usually mild-to-moderate in severity and resolves rapidly once the herb is stopped; normalization of liver function tests occurred in 3 mo[72]. However, the mortality rate found in our systematic review was considerable (14.2%) and, in some cases, required liver transplantation[75-77]. This rate may also be due to publication bias, since only more severe cases are generally reported.

Mitragyna speciosa : Mitragyna speciosa, also known as kratom, is a psychotropic and opioid-like drug extracted from the leaves of the kratom tree[78,79], which is used as a recreational drug and pain killer[80]. In this review, the mean age of kratom-induced HILI was 36 years, with a higher prevalence in men (62%). The onset of kratom induced HILI usually takes place within 1 wk to 8 wk after regular use of powder or tablets, ingested doses varied from 3 g to 15 g daily[81,82]. The cause of kratom induced HILI is unknown. The most common pattern of HILI was hepatocellular, but cholestatic and mixed were also prevalent. Patients who presented with acute liver injury due to kratom usually recovered after it was discontinued; normalization of liver parameters occurred in 40 d. There is no evidence that corticosteroids can shorten the course of the illness or improve outcomes[81]. Some patients used acetylcysteine and ursodeoxycholic acid. In more severe cases, liver transplantation was necessary[83].

Gynura segetum: Also known as Tusanqi or Jusanqi, it is commonly used in China. The herb is typically consumed for traumatic injuries[84]. In this review, the mean age of Tusanqi induced HILI was 54-years-old with a slightly higher prevalence in women (51.8%). The most common clinical manifestations included ascites, hepatomegaly, and jaundice. Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome was reported in all cases. Its extent in inducing hepatotoxicity is not sufficiently understood[85] but can be associated with pyrrolizidine alkaloids, as do many other herbs[86]. Symptoms generally began around 75 d after the use of the drug[85]. Tusanqi consumption is associated with high mortality[87]. In our systematic review, it was the herb with the worst recovery and prognosis. In some cases, liver transplantation might be required[85].

Garcinia gummi-gutta : Also known as garcinia cambogia, it is a herb usually sold as a weight loss product[88]. In this review, HILI induced by this product affected more commonly middle-aged women (89.7%), with ingested doses varying from 640 mg to 1400 mg/d[89,90]. Patients typically present abdominal pain, jaundice, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and elevations in serum aminotransferase levels in 1 wk to 4 wk after starting the product, although latency has been reported to be higher (3 mo to 12 mo) in some cases[91]. Garcinia induced HILI pattern is generally hepatocellular and immune features are uncommon. In most cases, liver injury resolves within 1 mo to 3 mo after discontinuation of the herb. However, if fulminant hepatitis develops, a liver transplantation might be performed[88,92]. Rechallenge should be avoided.

Ephedra sinica: Also known as ma huang, it is used worldwide as a weight loss agent and bodybuilding supplement. In this review, HILI induced by this product was more prevalent in middle-aged women (68%), with ingested doses varying from 100 mg/d to 8 g/d[73,93]. The main symptoms of ma huang induced HILI include abdominal pain, nausea, jaundice, fatigue, and hepatomegaly. The time for onset of symptoms ranged from a few weeks to more than 6 mo, with an average of 12 wk[94]. The most common lesion pattern was hepatocellular, which is consistent with previous literature findings[73]. The major adverse events reported were cardiovascular, including hypertension, palpitations, myocardial infarction, seizures, transient ischemic attacks, cerebrovascular accidents, and sudden death[94,95]. Recovery occurred within 1 mo to 6 mo after the herb was stopped. However, acute liver failure and necessity for liver transplantation have been reported[96].

Larrea tridentata : Chaparral is a botanical extract of the woody shrub known as Larrea tridentate, which is claimed to have beneficial effects for many conditions from skin rashes to cancer[97]. In this review, Chaparral-induced HILI was more prevalent in middle-aged women (65.4%), with ingested doses varying from 150 mg/d to 600 mg/d[98]. The most common symptoms included jaundice, abdominal pain, fatigue, and nausea. Chaparral induced HILI generally started within 3 wk to several years. Nevertheless, it began usually within 3 wk to 12 wk of starting daily ingestion or increasing daily dosage[97,99]. Pattern of liver injury was typically hepatocellular, but steatosis was also reported. Chaparral leaf extracts have multiple components that can affect intrahepatic pathways, including those involving cyclooxygenases and lipoxygenases[97,100]. Liver transplantation can be performed in severe cases, although withdrawal of the herb is usually enough for the clinical manifestations to resolve[99]. Normalization of liver function tests typically occurred in around 50 d.

Senna spp. : Senna (Cassia species) is a popular herbal laxative that can cause liver injury when used in high doses for longer than recommended periods[101]. In this review, the mean age of senna-induced HILI was 33-years-old, with a higher prevalence in women (78.3%), and an ingested dose varying from 15 mg to 300 mg/d[102,103].The main symptoms include jaundice, abdominal pain, encephalopathy, asthenia, and choluria. The time to onset of senna induced HILI was usually after 3 mo to 5 mo of use, and the pattern of serum enzyme elevations was hepatocellular[101]. Liver injury from long term senna use is rare, and most cases have been self-limited and rapidly reversible after stopping the herb, typically in 1 mo[104]. However, cases with a severe course with signs of acute liver failure have been described[105,106].

Aloe vera: Aloe vera is derived from a cactus-like plant, a member of the Lily family that grows best in arid climates[107]. It is popularly used for weight loss and constipation. In this paper, the mean age of aloe vera-induced HILI was 50 years with a higher prevalence in women (77.3%). The main symptoms include abdominal pain, jaundice, fatigue, and nausea. The injury typically arises between 3 wk to 24 wk after starting oral aloe vera[107]. Hepatocellular was the most common pattern of lesion. Rare cases of liver injury reported with aloe vera use have had idiosyncratic features[16]. In our systematic review, a poor prognosis was normally associated with the consumption of multiple herbs and resulted in liver transplantation and death[108]. However, it is typically self-limited once the herb is stopped. Normalization of liver tests typically occurred in 50 d.

Lycopodium serratum : It is a popular and widely used Chinese herb, also known as Jin Bu Huan. It is generally used for insomnia and pain management. In this review, the mean age of Lycopodium serratum-induced HILI was 46 years with a higher prevalence in women (89.5%), and ingested doses varied from 2-4 tablets/d, in which the concentration was unknown[109,110]. Patients generally present fatigue, hepatomegaly, pruritus, and jaundice. The onset of liver test abnormalities or clinical manifestation occurs within 2 wk to 24 wk of starting the herbal supplement[111]. The enzyme pattern was typically hepatocellular and recovery happened generally within 1 mo to 2 mo after withdrawal of the herb[111,112]. Mechanism of hepatotoxicity is not well understood, but it can be direct hepatotoxicity or an idiosyncratic reaction in some cases[113,114]. Jin Bu Huan induced HILI is usually self-limited and rapidly reversible after withdrawal of the herb. Rechallenge leads to the recurrence of injury and should be avoided. Some patients received cholestyramine, but the efficacy is questionable.

Study limitations

Some publications may have escaped the literature search, resulting in selective retrieval and incomplete listing of herbs, herbal supplements, herbal compounds, botanical names, and ingredients. Although 79 different herbal products with hepatotoxicity were identified from the literature, the causality assessment was incomplete due to lack of data in the majority of cases. Identification of the causative agent was also a limitation as herbs consist of dozens of potentially individual hepatotoxic specific chemicals. The situation is even more complex in herbal mixtures, such as Herbalife, which may also present additional chemicals as non-herbal ingredients that need evaluation.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review comprehensively gathered data from case reports and case series in the literature to provide an overview for physicians suspecting HILI and their patients. Further research should evaluate the potential HILI risk (incidence and prevalence) and clinical characteristics and identify hepatotoxic compounds of herbs and their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. It is necessary to improve our knowledge on possible risk factors for the development of liver injury, to validate causality assessment tools, and to improve treatment efficacy for HILI. The discussion of the risk of herbal use with the patients is paramount. The authors hope that these findings can offer direction for health professionals and scientific research and thus help to avoid liver failure associated with HILI in the future.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

In the last decades, the use of herbal supplements in the East and in the West, natural products, and alternative medicines has risen considerably, which is consistently underreported by patients. Despite popular belief that the consumption of natural products is harmless, herbs might cause injury to various organs. Herb-induced liver injury (HILI) is a term currently used to describe liver injury related to herbal medicines. The manifestations can vary depending on the causing product, ranging from asymptomatic cases with increased transaminases to fulminant liver failure, resulting in liver transplantation or death.

Research motivation

Our motivation was to gather data from case reports and case series in the literature to provide an overview for physicians suspecting HILI and to raise awareness for the risk associated with self-prescribed use of herbal products.

Research objectives

We aimed to review systematically the literature to identify herbal products associated with liver injury and describe the type of lesion associated with each product.

Research methods

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations contained in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidelines. Studies were retrieved using comprehensive search terms on nine electronic databases with no date of publication restrictions. Clinical case reports or case series involving herbal drug use and hepatotoxicity were included in the study. Studies were excluded if they were not case reports or case series or if they were not related to the topic. The variables collected were demographic data, herbs used, clinical presentation, liver function tests, biopsy results, comorbidities, comedications, and treatment, and the outcome measured was recovery, chronic liver disease, or death. Causality was assessed using the Maria and Victorino System of Causality Assessment in Drug Induced Liver Injury. Simple descriptive statistics, such as the mean ± standard deviation, frequency, and median were used to characterize the data. Data were summarized using RStudio (version 4.0.2), and the patterns of liver injury were classified using R value.

Research results

A total of 446 references corresponding to 936 cases were included. Case reports from the United States were the most common, and 65.2% of patients were females. The most prevalent herbs and herbal products were He-Shou-Wu, green tea extract, Herbalife, kava kava, and greater celandine, and a previous report of liver injury by the implied herb was described in 855 cases (98.1%). The most common clinical presentation of the reviewed cases was jaundice (46.3%), followed by abdominal pain and nausea (22.4% and 17.2%, respectively). The most common pattern of HILI was hepatocellular, in 660 (70%) cases, followed by sinusoidal obstruction syndrome in 92 (9.7%) cases and cholestatic in 80 (8.5%) cases. The mean Maria and Victorino System of Causality Assessment score was 8.69 (3.93, standard deviation) and median. The most prevalent treatments consisted of supportive care (66.1%), such as herbal withdrawal and intravenous fluid replacement. Complete recovery occurred in 782 (82.8%) of patients. Chronic liver disease and death were observed in 1.5% and 10.4% of the cases, respectively.

Research conclusions

This systematic review comprehensively gathers data from case reports and case series in the literature to provide an overview for physicians suspecting HILI and their patients. Further research should evaluate the potential HILI risk (incidence and prevalence) and clinical characteristics and identify hepatotoxic compounds of herbs and their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. It is necessary to improve our knowledge on possible risk factors for the development of liver injury, to validate causality assessment tools, and to improve treatment efficacy for HILI. The discussion of the risk of herbal use with the patients is paramount. The authors hope that these findings can offer direction for health professionals and scientific research and thus help to avoid liver failure associated with HILI in the future.

Research perspectives

Herbs and herbal products are a growing cause of liver damage that patients and physicians should be aware. Patients should be specifically asked about the use of herbs and herbal products because patients often do not consider them to be harmful. Further research should evaluate the potential HILI risk (incidence and prevalence) and clinical characteristics and identify hepatotoxic compounds on herbs and their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors have nothing to disclose.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Federação Brasileira De Gastroenterologia.

Peer-review started: February 23, 2021

First decision: March 28, 2021

Article in press: May 25, 2021

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zheng YW S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

Contributor Information

Vinícius Remus Ballotin, School of Medicine, Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Caxias do Sul 95070-560, RS, Brazil.

Lucas Goldmann Bigarella, School of Medicine, Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Caxias do Sul 95070-560, RS, Brazil.

Ajacio Bandeira de Mello Brandão, Post-Graduate Program in Medicine, Division of Hepatology, Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre (UFCSPA), Porto Alegre 90050-110, RS, Brazil.

Raul Angelo Balbinot, Department of Clinical Gastroenterology, Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Caxias do Sul 95070-560, RS, Brazil.

Silvana Sartori Balbinot, Department of Clinical Gastroenterology, Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Caxias do Sul 95070-560, RS, Brazil.

Jonathan Soldera, Department of Clinical Gastroenterology, Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Caxias do Sul 95070-560, RS, Brazil. jonathansoldera@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Suk KT, Kim DJ. Drug-induced liver injury: present and future. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2012;18:249–257. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2012.18.3.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amadi CN, Orisakwe OE. Herb-Induced Liver Injuries in Developing Nations: An Update. Toxics. 2018;6 doi: 10.3390/toxics6020024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet] 2012 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rashrash M, Schommer JC, Brown LM. Prevalence and Predictors of Herbal Medicine Use Among Adults in the United States. J Patient Exp. 2017;4:108–113. doi: 10.1177/2374373517706612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gyasi RM. Unmasking the Practices of Nurses and Intercultural Health in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Useful Way to Improve Health Care? J Evid Based Integr Med. 2018;23:2515690X18791124. doi: 10.1177/2515690X18791124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byeon JH, Kil JH, Ahn YC, Son CG. Systematic review of published data on herb induced liver injury. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;233:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng EX, Navarro VJ. Liver Injury from Herbal, Dietary, and Weight Loss Supplements: a Review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2015;3:93–98. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2015.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartnik C, Subramanian R. Kava Kava, Not for the Anxious: A Case of Fulminant Hepatic Failure After Kava Kava Supplementation: 2373. Offic J Am Coll Gastroenterol . 2017;112:S1292. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yellapu RK, Mittal V, Grewal P, Fiel M, Schiano T. Acute liver failure caused by 'fat burners' and dietary supplements: a case report and literature review. Can J Gastroenterol. 2011;25:157–160. doi: 10.1155/2011/174978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maria and Victorino (M & V) System of Causality Assessment in Drug Induced Liver Injury 2012. In: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012– . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grieco A, Miele L, Pompili M, Biolato M, Vecchio FM, Grattagliano I, Gasbarrini G. Acute hepatitis caused by a natural lipid-lowering product: when "alternative" medicine is no "alternative" at all. J Hepatol. 2009;50:1273–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piccolo P, Gentile S, Alegiani F, Angelico M. Severe drug induced acute hepatitis associated with use of St John's wort (Hypericum perforatum) during treatment with pegylated interferon α. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009 doi: 10.1136/bcr.08.2008.0761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chow HC, So TH, Choi HCW, Lam KO. Literature Review of Traditional Chinese Medicine Herbs-Induced Liver Injury From an Oncological Perspective With RUCAM. Integr Cancer Ther. 2019;18:1534735419869479. doi: 10.1177/1534735419869479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashar BH, Rice TN, Sisson SD. Medical residents' knowledge of dietary supplements. South Med J. 2008;101:996–1000. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31817cf79e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bottenberg MM, Wall GC, Harvey RL, Habib S. Oral aloe vera-induced hepatitis. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1740–1743. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valente G, Sanges M, Campione S, Bellevicine C, De Franchis G, Sollazzo R, Mattera D, Cimino L, Vecchione R, D'Arienzo A. Herbal hepatotoxicity: a case of difficult interpretation. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010;14:865–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navarro VJ, Bonkovsky HL, Hwang SI, Vega M, Barnhart H, Serrano J. Catechins in dietary supplements and hepatotoxicity. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2682–2690. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2687-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chalasani N, Björnsson E. Risk factors for idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2246–2259. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chalasani N, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, Davern T, Serrano J, Yang H, Rochon J Drug Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) Causes, clinical features, and outcomes from a prospective study of drug-induced liver injury in the United States. Gastroenterology 2008; 135: 1924-1934, 1934.e1-1934. :e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin NH, Yang HW, Su YJ, Chang CW. Herb induced liver injury after using herbal medicine: A systemic review and case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e14992. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wainwright J, Schonland MM. Toxic hepatitis in black patients in natal. S Afr Med J. 1977;51:571–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adrane NB, Skalli S, Chabat A, Bencheikh RS. Two fatal cases following use of plant mixtures for weight gain. Procee Clin Toxicol . 2013:268–268. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muhlbauer B, Wille H, Puntmann I. Mistletoe-induced autoimmune-hepatitis. Proceedings of the Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Archives Of Pharmacology. New York: Springe, 2004: R157-R157. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang JB, Zhu Y, Bai ZF, Wang FS, Li XH, Xiao XH Branch Committee of Hepatobiliary Diseases and Branch Committee of Chinese Patent Medicines; China Association of Chinese Medicine. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Herb-Induced Liver Injury. Chin J Integr Med. 2018;24:696–706. doi: 10.1007/s11655-018-3000-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu Y, Li YG, Wang Y, Wang LP, Wang JB, Wang RL, Wang LF, Meng YK, Wang ZX, Xiao Xiao H. [Analysis of Clinical Characteristics in 595 Patients with Herb-induced Liver Injury] Zhongguo Zhongxiyi Jiehe ZaZhi. 2016;36:44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu Y, Niu M, Wang JB, Wang RL, Li JY, Ma YQ, Zhao YL, Zhang YF, He TT, Yu SM, Guo YM, Zhang F, Xiao XH, Schulze J. Predictors of poor outcomes in 488 patients with herb-induced liver injury. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2019;30:47–58. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2018.17847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chalasani NP, Hayashi PH, Bonkovsky HL, Navarro VJ, Lee WM, Fontana RJ Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. ACG Clinical Guideline: the diagnosis and management of idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:950–66; quiz 967. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.European Association for the Study of the Liver Clinical Practice Guideline Panel: Chair; Panel members; EASL Governing Board representative. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Drug-induced liver injury. J Hepatol. 2019;70:1222–1261. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) in Drug Induced Liver Injury 2012. In: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012– . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rabe C, Musch A, Schirmacher P, Kruis W, Hoffmann R. Acute hepatitis induced by an Aloe vera preparation: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:303–304. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vitalone A, Menniti-Ippolito F, Moro PA, Firenzuoli F, Raschetti R, Mazzanti G. Suspected adverse reactions associated with herbal products used for weight loss: a case series reported to the Italian National Institute of Health. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67:215–224. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0981-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whiting PW, Clouston A, Kerlin P. Black cohosh and other herbal remedies associated with acute hepatitis. Med J Aust. 2002;177:440–443. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pelkonen O, Pasanen M, Lindon JC, Chan K, Zhao L, Deal G, Xu Q, Fan TP. Omics and its potential impact on R&D and regulation of complex herbal products. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140:587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee WJ, Kim HW, Lee HY, Son CG. Systematic review on herb-induced liver injury in Korea. Food Chem Toxicol. 2015;84:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teschke R, Frenzel C. Drug induced liver injury: do we still need a routine liver biopsy for diagnosis today? Ann Hepatol. 2013;13:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan CQ, Crawford JM. Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (hepatic veno-occlusive disease) J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4:332–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garrido-Gallego F, Muñoz-Gómez R, Muñoz-Codoceo C, Delgado-Álvarez P, Fernández-Vázquez I, Castellano G. Acute liver failure in a patient consuming Herbalife products and Noni juice. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:247–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong LL, Lacar L, Roytman M, Orloff SL. Urgent Liver Transplantation for Dietary Supplements: An Under-Recognized Problem. Transplant Proc. 2017;49:322–325. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu Y, Niu M, Chen J, Zou ZS, Ma ZJ, Liu SH, Wang RL, He TT, Song HB, Wang ZX, Pu SB, Ma X, Wang LF, Bai ZF, Zhao YL, Li YG, Wang JB, Xiao XH Specialized Committee for Drug-Induced Liver Diseases. Division of Drug-Induced Diseases, Chinese Pharmacological Society. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: Comparison between Chinese herbal medicine and Western medicine-induced liver injury of 1985 patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:1476–1482. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Polygonum Multiflorum. In: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dong H, Slain D, Cheng J, Ma W, Liang W. Eighteen cases of liver injury following ingestion of Polygonum multiflorum. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22:70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Y, Yang L, Liao Z, He X, Zhou Y, Guo H. Epidemiology of drug-induced liver injury in China: a systematic analysis of the Chinese literature including 21,789 patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:825–829. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835f6889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lei X, Chen J, Ren J, Li Y, Zhai J, Mu W, Zhang L, Zheng W, Tian G, Shang H. Liver Damage Associated with Polygonum multiflorum Thunb.: A Systematic Review of Case Reports and Case Series. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:459749. doi: 10.1155/2015/459749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rao T, Liu YT, Zeng XC, Li CP, Ou-Yang DS. The hepatotoxicity of Polygonum multiflorum: The emerging role of the immune-mediated liver injury. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2021;42:27–35. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jung KA, Min HJ, Yoo SS, Kim HJ, Choi SN, Ha CY, Kim TH, Jung WT, Lee OJ, Lee JS, Shim SG. Drug-Induced Liver Injury: Twenty Five Cases of Acute Hepatitis Following Ingestion of Polygonum multiflorum Thunb. Gut Liver. 2011;5:493–499. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2011.5.4.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teschke R, Genthner A, Wolff A, Frenzel C, Schulze J, Eickhoff A. Herbal hepatotoxicity: Analysis of cases with initially reported positive re-exposure tests. Dig Liver Dis . 2014;46:264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, Wang L, Saxena R, Wee A, Yang R, Tian Q, Zhang J, Zhao X, Jia J. Clinicopathological features of He Shou Wu-induced liver injury: This ancient anti-aging therapy is not liver-friendly. Liver Int. 2019;39:389–400. doi: 10.1111/liv.13939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panis B, Wong DR, Hooymans PM, De Smet PA, Rosias PP. Recurrent toxic hepatitis in a Caucasian girl related to the use of Shou-Wu-Pian, a Chinese herbal preparation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:256–258. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000164699.41282.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Green Tea. In: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarma DN, Barrett ML, Chavez ML, Gardiner P, Ko R, Mahady GB, Marles RJ, Pellicore LS, Giancaspro GI, Low Dog T. Safety of green tea extracts : a systematic review by the US Pharmacopeia. Drug Saf. 2008;31:469–484. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200831060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patel SS, Beer S, Kearney DL, Phillips G, Carter BA. Green tea extract: a potential cause of acute liver failure. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5174–5177. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i31.5174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prieto de Paula JM, Gómez Barquero J, Franco Hidalgo S. [Toxic hepatitis due to Camellia sinensis] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;31:402. doi: 10.1157/13123613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arzenton E, Magro L, Paon V, Capra F, Apostoli P, Guzzo F, Conforti A, Leone R. Acute hepatitis caused by green tea infusion: a case report. Adv Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf . 2014;3 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mazzanti G, Menniti-Ippolito F, Moro PA, Cassetti F, Raschetti R, Santuccio C, Mastrangelo S. Hepatotoxicity from green tea: a review of the literature and two unpublished cases. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:331–341. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gallo E, Maggini V, Berardi M, Pugi A, Notaro R, Talini G, Vannozzi G, Bagnoli S, Forte P, Mugelli A, Annese V, Firenzuoli F, Vannacci A. Is green tea a potential trigger for autoimmune hepatitis? Phytomedicine. 2013;20:1186–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oketch-Rabah HA, Roe AL, Rider CV, Bonkovsky HL, Giancaspro GI, Navarro V, Paine MF, Betz JM, Marles RJ, Casper S, Gurley B, Jordan SA, He K, Kapoor MP, Rao TP, Sherker AH, Fontana RJ, Rossi S, Vuppalanchi R, Seeff LB, Stolz A, Ahmad J, Koh C, Serrano J, Low Dog T, Ko R. United States Pharmacopeia (USP) comprehensive review of the hepatotoxicity of green tea extracts. Toxicol Rep. 2020;7:386–402. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Molinari M, Watt KD, Kruszyna T, Nelson R, Walsh M, Huang WY, Nashan B, Peltekian K. Acute liver failure induced by green tea extracts: case report and review of the literature. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1892–1895. doi: 10.1002/lt.21021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Humberston CL, Akhtar J, Krenzelok EP. Acute hepatitis induced by kava kava. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2003;41:109–113. doi: 10.1081/clt-120019123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moro PA, Cassetti F, Giugliano G, Falce MT, Mazzanti G, Menniti-Ippolito F, Raschetti R, Santuccio C. Hepatitis from Greater celandine (Chelidonium majus L.): review of literature and report of a new case. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;124:328–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kava Kava. In: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Teschke R, Schwarzenboeck A, Hennermann KH. Kava hepatotoxicity: a clinical survey and critical analysis of 26 suspected cases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:1182–1193. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283036768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Campo JV, McNabb J, Perel JM, Mazariegos GV, Hasegawa SL, Reyes J. Kava-induced fulminant hepatic failure. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:631–632. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Teschke R, Frenzel C, Glass X, Schulze J, Eickhoff A. Greater Celandine hepatotoxicity: a clinical review. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11:838–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Celandine. In: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stickel F, Pöschl G, Seitz HK, Waldherr R, Hahn EG, Schuppan D. Acute hepatitis induced by Greater Celandine (Chelidonium majus) Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:565–568. doi: 10.1080/00365520310000942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Germander. In: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Laliberté L, Villeneuve JP. Hepatitis after the use of germander, a herbal remedy. CMAJ. 1996;154:1689–1692. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dag M, Özturk Z, Aydnl M, Koruk I, Kadayfç A. Postpartum hepatotoxicity due to herbal medicine Teucrium polium. Ann Saudi Med. 2014;34:541–543. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2014.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bunchorntavakul C, Reddy KR. Review article: herbal and dietary supplement hepatotoxicity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:3–17. doi: 10.1111/apt.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goksu E, Kilic T, Yilmaz D. Hepatitis: a herbal remedy Germander. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2012;50:158. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2011.647993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mattéi A, Rucay P, Samuel D, Feray C, Reynes M, Bismuth H. Liver transplantation for severe acute liver failure after herbal medicine (Teucrium polium) administration. J Hepatol. 1995;22:597. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80458-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Skullcap. In: LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2012 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Woo HJ, Kim HY, Choi ES, Cho YH, Kim Y, Lee JH, Jang E. Drug-induced liver injury: A 2-year retrospective study of 1169 hospitalized patients in a single medical center. Phytomedicine. 2015;22:1201–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Braude MR, Bassily R. Drug-induced liver injury secondary to Scutellaria baicalensis (Chinese skullcap) Intern Med J. 2019;49:544–546. doi: 10.1111/imj.14252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Estes JD, Stolpman D, Olyaei A, Corless CL, Ham JM, Schwartz JM, Orloff SL. High prevalence of potentially hepatotoxic herbal supplement use in patients with fulminant hepatic failure. Arch Surg. 2003;138:852–858. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.8.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kesavarapu K, Kang M, Shin JJ, Rothstein K. Yogi Detox Tea: A Potential Cause of Acute Liver Failure. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2017;2017:3540756. doi: 10.1155/2017/3540756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]