Abstract

Background:

Protective stabilization (PS) is a method of medical restraint used for behavior management for children and adults with special needs for dental care. With the increase in availability and options for behavior management techniques, PS has become less popular and more controversial. This scoping review analyzes the use of PS for dental care for adults with special needs within the literature.

Methods:

A review of publications between 1990 and 2020 was conducted in Ovid Medline, Embase, and Dentistry and Oral Sciences Source using the search terms as follows: “protective stabilization,” “dentistry,” “restraint,” “patient positioning,” and “immobilization,” with Boolean operators “AND” and “OR.” Articles were screened by title and abstract and included by full read review with consensus from the research team.

Results:

A total of 298 articles were reviewed and 29 were included as part of the scoping review. The articles include original research, policy guidelines, and clinical commentary reviews.

Conclusion:

There is variable evidence regarding the use of PS as a method of behavioral management for adults with special needs. It is less popular for use due to improvements in alternative methods such as pharmacologic intervention and general anesthesia. PS still has applicable use among this population and is dependent on patient and parental consent, patient selection and safety, and clinician training.

Protective stabilization (PS), a method of medical restraint, has been utilized to evaluate and treat non-cooperative patients, such as patients with special healthcare needs (SHCN) or pediatric patients, in medical and dental settings.1 PS is a method of physical restraint that involves the partial or complete immobilization of a patient’s head, body, and/or extremities for a finite time period.1–3 This restraint is applied in dentistry for assessment and treatment purposes in patients who are unable to cooperate or remain still for care.1–5 The existing literature is based more in pediatric populations, but this information can be viewed from the lens of application for adults with SHCN.1,2,6 In adult populations, PS is predominantly used for patients with SHCN whose developmental, acquired, intellectual, or physical disabilities result in behavioral and/or movement difficulties that challenge routine outpatient dental care.7 Examples include persons with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), cerebral palsy (CP), tardive dyskinesias, and generalized cognitive impairment or developmental delay.1–3,5

Dental care has been shown to be the most unmet healthcare need for adults with SHCN.8–10 PS has been suggested throughout the literature as a modality to facilitate improved access when other treatment options are unsuccessful, unavailable, or contraindicated.5,6,11–13 Glassman et al stated that general dentists serve as access points for oral care for adults with SHCN who may benefit from use of PS for evaluation and/or treatment.3,12 Application of PS may facilitate a more accurate assessment if complete treatment is not possible, and may then also facilitate an improved and thorough referral.2,12

PS previously was one of few options to enable dental management for adults with SHCN.14 However, increased safety, monitoring, and accessibility of conscious sedation techniques and general anesthesia, as well as improvements and intentions in other behavior guidance techniques such as habituation and desensitization, provide alternative methods for treatment that are currently more widely and well accepted than PS.15–17 Due to improvements in alternative behavior methods, shifts in attitudes have occurred among the healthcare community regarding use of PS.14,18 For example, in the United Kingdom, PS is no longer a legal method of care.14,19 However, within the literature PS still remains a controversial topic. The use of PS reportedly can be traumatic for patients and is perceived to be no longer in accordance with the standard of care with increased access and improvements in alternative techniques.18 Yet PS is supported in the literature as a viable treatment modality to facilitate care for adults with SHCN in the community when other options are contraindicated, unsuccessful, or unavailable and when limited treatment of short duration is required.2,3,12

This scoping review article frames the use of these protocols and compiles the literature for the use of PS for adults with SHCN. The authors stratify what has been published regarding PS techniques, patient/guardian education and consent, indications, contraindications, clinical team considerations, and documentation and maintenance of PS.

Methods

A comprehensive literature review was completed to evaluate the application, clinical guidelines, and perceptions of PS, as well as its application for adults with SHCN. The literature search was conducted with searches in Ovid Medline, Embase, and Dentistry and Oral Sciences Source using the search terms as follows: “protective stabilization,” “dentistry,” “restraint,” “patient positioning,” and “immobilization.” The searches were completed with these terms individually and in various combinations with the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR.” Searches were completed in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020 to accommodate new research and literature.

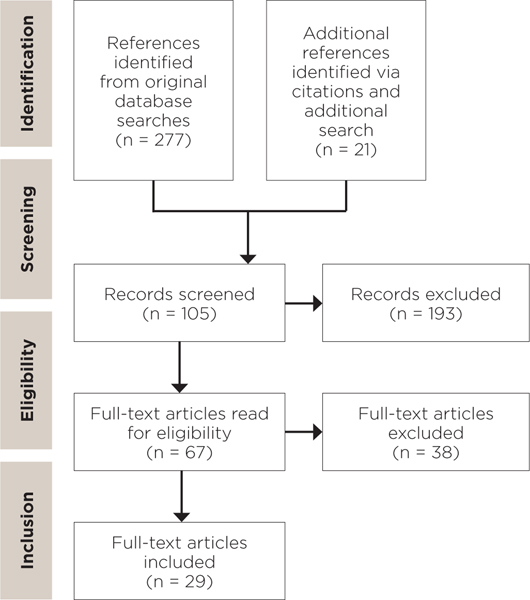

Of 298 results, 29 were relevant to the use of active or passive restraint in providing care to pediatric patients or adults with SHCN based on the selection criteria outlined in Figure 1. These articles were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) relevance to the application of PS for adults with SHCN, (2) published in English language to avoid translation bias, and (3) published 1990 or later to maintain contemporary relevance.

Fig 1.

Selection criteria: English language, published 1990 or after, full article available online, specifically pertaining to the direct use of protective stabilization for pediatric patients or adults with SHCN in clinical practice, including original research studies, literature reviews, practice guidelines, commentaries, and editorial articles.

Articles selected were first reviewed for relevance by title and abstract, followed by full article review of those selected by title and abstract Articles were included based on agreement by the research team. If there was disagreement among the team, those articles in question were re-reviewed until consensus was obtained. Articles selected consisted of original research, clinical guidelines, statutory code, and commentary surrounding PS (Table 1). (To view Table 1, “Included Articles From Scoping Review,” visit compendiumlive.com/go/cced1959.) Source papers were also reviewed from references of literature obtained from the search.

Table 1:

Passive Stabilization Devices

| Device Type | Method | Example Products | Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full body stabilization/ immobilization | Passive | Papoose board® Rainbow Wrap® (PB, Olympic Medical Corporation, Seattle, WA) Joey Board® (Joey Board, Queen Creek, AZ) | Secures extremities as well as full body for immobilization for procedures |

| Extremity stabilization | Passive or active | Velcro® straps Posey Secure Straps® Seat belts (Velcro® Companies, Manchester, NH) | Secures limbs individually to decrease untoward movements |

| Oral stabilization | Passive | Molt® mouth prop (Hu-Friedy Mfg Co, LLC, Chicago, IL) Open Wide Mouth Rest® (Specialized Care Co, Hampton, NH) | Assists in keeping a patient’s mouth open for dental procedures |

| Patient positioning | Active or passive | Hydraulic patient lift Wheel chair tilt | Assists with the transfer of a patient to the dental chair, or assists in the tilted back position of a patient within a non-reclining wheelchair |

PS Techniques

Active restraint involves physical immobilization by a healthcare provider and team, parent, or guardian, while passive restraint involves the use of a mechanical stabilization device for immobilization (Table 2).1,2,6 (To view Table 2, “Passive Stabilization Devices,” visit compendiumlive.com/go/cced1959.) Both are forms of PS. Active restraint can include head holds, therapeutic holds, and hand/arm or leg guarding. Passive restraint is implemented by utilizing a device, such as a Papoose Board® (Olympic Medical Corporation), mouth prop, blanket, or arm and/or wrist straps to hold a patient’s head, body, and/or extremities.2,16 The conventional Papoose Board has individual straps for a patient’s arms, an ankle strap to secure the legs, and wraps around the patient’s body and a stabilizing board with Velcro® secured wrap. Passive restraint implies the patient is secured with these devices. Positioning devices may assist in PS. These include wheelchair head supports, pillows, mouth props, and arm rests. Active and passive restraint may be utilized at the same time for patient care, depending on the clinical circumstance.2,16

Table 2:

Included Articles from Scoping Review

| REFERENCE NUMBER | AUTHORS/ ORGANIZATION | YEAR | TYPE OF ARTICLE | COUNTRY OF ORIGIN | KEY FINDINGS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AAPD | 2018 | Policy Statement/ Best Practices Guidelines | US | These clinical guidelines outline the utilization of PS for pediatric dental patients. |

| 2 | AADMD | 2017 | Policy Statement | US | These clinical guidelines outline the use of stabilization/ restraint for adults, including indications, contraindications, and clinical considerations. |

| 3 | Glassman P | 2008 | Review Article | US | There are several options to facilitate dental treatment for PSHCN, and options depend on patient selection and dental needs. |

| 4 | AAPD | 2015 | Policy Statement/ Clinical Practice Guidelines | US | Proper communication, informed consent, and patient or clinician interventions can direct behavior guidance for pediatric patients |

| 5 | Karibe et al | 2008 | Observational Case Control Study | Japan | Diagnosis of profound cognitive disability may be an indication that PS is necessary to provide dental treatment in a clinic setting. |

| 6 | Martinez Mier EA et al | 2019 | Survey Study | US | Acceptance of different behavior techniques varies by parental ethnicity/ race/ background between Hispanic, black, and white parents. |

| 8 | Newton JT | 2008 | Review Article | UK | There is a place for restraint as a method of behavior management for PSHCN, but there are several considerations, including benefits outweighing the risk, legal concerns of consent/ assent, and efficacy of its use for care. |

| 11 | Frankel RI | 1991 | Survey Study | US | Parents of pediatric patients who were stabilized with a papoose board for dental procedures believed it to be helpful for the completion of dentistry, safer for their child than no restraint for the dental procedure, and 78% did not think there was a later negative effect of use of the papoose board. |

| 12 | Glassman P et al | 2009 | Consensus Statement | US | There are several options that may be utilized to facilitate dental care for PSHCN - choosing which method to use must take into consideration the patient’s health status, support system, financial status, and patient safety |

| 13 | Romer M | 2009 | Review Article | US | There are several confounding factors that impact the use of restraint for dental treatment for PSHCN including informed consent, patient communication, availability/ efficacy of other methods of behavior management, and patient condition/ health. |

| 14 | Kupietzky A | 2004 | Review Article | Israel | PS in combination with conscious sedation can be a viable option to provide dental treatment for an otherwise uncooperative child. It should be clearly explained to parents, and used prior to general anesthesia for option to facilitate treatment. |

| 15 | Costa LR et al | 2020 | Survey Study | UK/ Brazil | Among pediatric dentists surveyed the majority utilize PS for patients with dental fear and dental anxiety, while fewer routinely use, feel comfortable, or are training in pharmacologic based methods for behavior management. Brazil lacks in a balanced curriculum of general anesthesia/ sedation for pediatric dentists |

| 16 | Adair SM, Rockman RA, Schafer TE, Waller JL | 2004 | Survey Study of Pediatric Residency Programs | US | All surveyed pediatric residency programs in the US teach sedation techniques as acceptable behavior management, most teach active and passive sedation as acceptable methods of behavior management. |

| 17 | White et al | 2016 | Survey Study | US | Parental understanding of sedation and restraint options/ techniques is variable but the majority of parents surveyed believe sedation is safe and puts their child to sleep without the need for PS for dental procedures. |

| 18 | Weaver JM | 2010 | Editorial Article | US | With the availability of modern anesthesia and its prolific use for medical procedures, restraint should not be tolerated to facilitate dental care. |

| 19 | Bridgmann AM | 2000 | Review Article | UK | In the UK, restraint constitutes battery and is of particular concern if a patient is competent to consent and does not consent to the use of restraint. For patients who cannot consent clinical judgement with an assessment of “reasonableness” can justify its use. |

| 21 | Peretz B, Gluck GM | 2002 | Review Article | Israel/ US | Restraint is an option for facilitating dental treatment for the uncooperative patient, but dentists should focus on methods that allow for effective and efficient provision of care, as well as methods that support a positive attitude of the dentist. More research is required to evaluate the use of restraint. |

| 23 | AAPD | 2015 | Policy Statement/ Clinical Practice Guidelines | US | These guidelines outline the necessity for and methods of obtaining informed consent for pediatric patients/ incompetent adults. |

| 24 | Kupietzky A, Ram D | 2005 | Survey Study | Israel | Parents of pediatric patients who received positive explanation of PS were more accepting than parents who received a neutral explanation. |

| 32 | Romer M, Filanoa V. | 2006 | Review Article | US | For persons with developmental disabilities, obtaining an accurate medical history, informed consent, and the provision of care with aids/ restraint may be complicated by the need to seek the information through a third party. |

| 34 | Nelson T | 2013 | Review article | US | Behavior guidance techniques exist within a continuum of options that should be attempted and selected based on patient factors such as age, temperament, patient health, parental preferences. |

| 37 | Hirayama A, Fukuda K, Koukita Y, Ichinohe T | 2019 | Case Series | Japan | The addition of IV ketamine to propofol for sedation for dental procedures for intellectually disabled patients aids in patient stabilization without a negative impact on recovery. |

| 38 | Saxen MA, Tom JW, Mason KP | 2019 | Case Series/ Review Article | US | Appropriate planning and preparation, patient pre-operative evaluation and selection, emergency preparedness, and experience are critical to consider when administered office based sedation/ anesthesia for dental care. |

| 40 | Dougall A, Fiske J | 2008 | Review Article | UK | Mental capacity, literacy, and comprehension of a procedure, risks, benefits, alternatives, and process are necessary for valid informed consent for procedures as well as physical intervention/ restraint. |

| 43 | Lee JY, Vann WF, Roberts MW | 2001 | Cost effectiveness study | US | For patients who require multiple conscious sedation appointments for treatment, the break even point for conscious sedation versus general anesthesia is >3 appointments. |

| 44 | Cote CJ, Wilson S | 2006 | Clinical Report | US | The goals of sedation are to safely and effectively complete dental care in a manner to limit dental anxiety and discomfort. The process should include appropriate patient selection, adequate facilities, proper monitoring and emergency services, documentation, and proper use of equipment for sedation and stabilization. |

| 45 | Acs G, Musson CW, Burke MJ | 1990 | Survey Study of Pediatric Residency Programs | US | Among pediatric programs surveyed, oral sedation use increased, other sedation types roughly remained the same, other restraint besides hand over mouth roughly remained the same. |

| 46 | Crossley ML, Joshi G | 2002 | Survey Study | UK | Active and Papoose restraint not well regarded by parents of pediatric patients or pediatric dentists, tell- show-do was the most well accepted and used among survey participants. |

| 50 | Oliver K, Manton DJ | 2015 | Review Article | Australia | Behavior management techniques span a continuum with different modalities and levels of severity. The acceptance and utilization of these modalities are fluid and evolve with different demographics, ages, and over time. |

Education and Consent

Patient and guardian education regarding PS is necessary prior to its implementation.13,16,20,21 The patient and/or the patient’s legal guardian must be educated regarding the purpose, methods, and equipment used.20,22,23 Education is an important part of obtaining informed consent, and full understanding of PS indications, benefits, risks, and alternatives prior to consent is required.13 PS is not highly accepted compared to alternative methods of behavior management such as voice control, habituation, and sedation methods.6,17 However, according to studies by Frankel and Kupietzky, when presented in a constructive, positive, and comprehensive manner, there is increased acceptance, which can allay the negative stereotypes of PS and facilitate acceptance.11,24 When the relative risks and benefits of PS are discussed independently as well as comparatively with other behavior modification modalities, patients and guardians are able to appropriately weigh the risks of PS versus the benefit of the immediacy of care PS can provide.14,24–26

When providing education about PS, the following items should be explicitly discussed: (1) general behavior limitations to provide safe assessment or treatment and indications for use of PS; (2) methodology of PS use, including demonstration of devices; and (3) the psychological impact of PS use. Regarding the latter item, it should be noted that: PS may provide a sense of security; parents/guardians should be involved in active restraints for patient comfort when possible26; and there is potential for patient discomfort, stress, and an adverse response.2,13,17,21,24

Informed consent demonstrates a decision on the part of the patient and/or legal guardian for a procedure.27 This process ensures the patient and/or legal guardian are aware of the implications and process of PS and that patient beneficence, non-maleficence, and autonomy are prioritized and maintained even for patients who are not able to consent for themselves.13,20,22,23,28 The use of PS is a dynamic process and consent for its use can be withdrawn at any time.23

According to the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD), written informed consent for PS should be obtained every time it is used in addition to written consent for the concurring dental procedures.23 When possible, written informed consent should be obtained prior to its use, so the designated consenting party can make an informed decision without the risk of a decision under duress.23,29 Informed consent does not have an explicit duration or expiry, but many protocols define a finite length of time between consent and implementation for validity.22,30 However, prior to implementation of PS, the provider should reconfirm consent and review benefits, risks, and alternatives with the patient and/or guardian, as well as document the updated consent.13,22,23,31 Often times guardians will help with active PS, which is an act of implied consent for the procedure.13,23,32 According to Schuman et al, if explicit consent is not obtained and documented, PS can be legally construed as criminal assault and battery.33

While PS is often utilized for patients who do not make their own medical decisions, patients with physical or movement disorders who are not cognitively impaired may request PS to prevent untoward movements during treatment. Informed consent should still be obtained for the use of PS in this scenario despite the implied consent.23

Patient selection is an important consideration when utilizing PS.2,34 It is intended to facilitate treatment, but can heighten aggravation, aggression, stress, and/or discomfort for some patients.26,34 According to guidelines published by the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry (AADMD) and Nelson, for patients who demonstrate increased disturbance by vocal or physical means, such as those with a history of trauma or psychiatric diagnoses, PS can potentially contribute to more harm and trauma than benefit.2,34

Indications for Use

Thoughtful consideration is necessary before implementing PS for dental care. The risks and benefits of PS must be evaluated critically against alternatives, and use of PS must reflect greater benefit to the patient than potential risk.17,34 Per AADMD and AAPD clinical guidelines, PS should only be used for appointments/assessments of short duration or urgent procedures for uncooperative patients.1,2,4 Techniques should limit untoward movements of the head, body, and limbs during treatment to allow for completion of treatment and should prevent injury to the patient and care team.2,34,35 Additionally, PS should be tolerable by the patient without causing harm.6,34 It is important to note the distinction between general patient discomfort in accordance with limited cooperativity versus the infliction of physical or physiological harm or trauma with the use of PS.8,21,36 According to Hirayama et al, PS may be used with sedation methods to further improve patient comfort and safety without negative impact on patient recovery.37

PS should be considered in adults with SHCN when it will facilitate safe and efficient completion of minimally invasive procedures or accurate assessment for necessary treatment, as stated by Nelson, Costa, and Davila.15,34,35 PS may also be used in conjunction with oral anxiolysis, nitrous oxide, or moderate sedation to increase patient comfort and cooperation for treatment.3,8,14 In emergent circumstances, PS can be used to manage dental urgencies/emergencies when systemic disease implications exist and other options such as sedation and general anesthesia are not available or timely.2,14,34,38 According to Nelson, PS is intended for use in the outpatient dental setting when a patient is unable to tolerate or cooperate for treatment and other less invasive attempted modalities have been unsuccessful and insufficient.6,14,34 It may be considered for patients in which conscious sedation medications or general anesthetics are contraindicated or unavailable in acute situations.18 Such contraindications can include allergy or adverse reactions to sedation medications or concerns for other comorbidities from a cardiopulmonary, neurological, renal, hepatic, or respiratory standpoint.3,26,34 Sedation and general anesthesia may not represent safe or realistic options for routine dental care, such as recall visits.13,34,39 According to Nelson and Newton, PS can be used as an alternative to reduce the need for more invasive methodologies for dental treatment needs.8,34 Dougall states that clinicians should act in the best interest of the patient for care—the risks of neglected, untreated dental disease can supersede the risks and disadvantages of PS in those circumstances where alternative methods may be impossible or untimely.8,28,40 However, when utilizing PS, clinicians must maintain an ethical standard and exhibit a mindful, professional attitude toward the patient to ensure his or her best interests.20,40

During the COVID-19 pandemic, access to care for this patient population is even more limited. Alternatives to PS such as nitrous oxide, general anesthesia, and anxiolysis/sedation are more limited due to heightened personal protective equipment (PPE) requirements, concerns for aerosol-producing procedures, limitations on elective procedures, and reallocation of supplies and personnel.41 PS may serve as an access point for patients of this population to obtain timely care despite limitations due to the pandemic.

Lastly, PS may be the most cost-effective modality in a setting where there are limited financial resources or limited insurance coverage for outpatient sedation or general anesthesia.15,42 Treatment under general anesthesia for significant dental needs has been shown to be more cost-effective than treatment under in-office sedation when treatment may take several appointments, in which case PS may enable some care.43 However, financial reasons alone are not an indication for the use of PS.1,2,15,42,43

Contraindications for use

According to AADMD, AAPD, Nelson, and Costa, PS is contraindicated in scenarios in which the risks outweigh the potential benefits, the providing team is not comfortable or trained in utilizing PS, or when written informed consent is not provided by the patient, their legal guardian, or a durable power of attorney.1,2,15,23,34 If a provider is not comfortable using PS, or a patient or guardian explicitly declines its use, PS should not be implemented.18

Contraindications include: a patient who is cooperative, a patient for whom immobilization can cause physical harm due to a physical or medical condition, and a patient who requires lengthy appointments and significant treatment to be completed in a single visit.2,20,21,31,34 PS should not be applied in a manner that is physically or unduly psychologically traumatic, or where it is not legally permitted.19 It is important to acknowledge that PS is used for patients who may not be inherently cooperative, and thus, the person may resist.2,4–6,20 Implementation may be uncomfortable with resultant resistant behavior, but the clinical distinction between discomfort and physical or psychological harm is critical.

Thoughtful patient selection for use of PS with or without sedation is crucial, and PS should not be implemented for patients for whom it will heighten trauma and anxiety without the use of concomitant sedation.44 This must be assessed and acknowledged by a trained provider implementing PS.36 The patient’s well-being is the highest priority. Patients with intellectual or developmental disabilities may not be cooperative for treatment with PS, but if they express physical pain, psychological pain, or severe discomfort, either physically or verbally, PS should be discontinued and alternatives should be considered.2,5,22,31,34

Team Philosophy of Care

To implement PS in the outpatient dental setting, the provider and clinical staff should be trained in the safe and proper methods of its use, including how to transfer a patient to the dental chair, how to position the patient, how to apply the devices, and how to stabilize the patient without causing harm or trauma.26 Training should include didactic components as well as hands-on methods/simulation.2,16,36,45,46 The extent of formal training providers and clinical staff receive varies across the field of dentistry.45 This training may be acquired in school or clinical practice, but several resources, such as the American Dental Assistants Association, are also available that provide this specific training for the clinical team.47 These include online seminars and didactic training through professional organizations, as well as didactic and hands-on training through continuing education courses.1,48,49 A united, informed, educated, and trained clinical team is paramount to the safe and effective administration of PS.14,50

According to Kupietzky and Ram, much of the negative perception of PS stems from its overuse by clinicians, poor patient education, and poor patient selection.24 A well-trained clinical team should have the expertise and capacity to ensure that patients and their guardians are properly educated and informed on the use of PS, that it is used appropriately and efficiently, and its use causes minimal disturbance or trauma to the patient.1,2,24,34

Documentation and Maintenance

As stated by Glassman et al, documentation of PS use is very important, and should include indication for PS, informed consent, type of immobilization device used, duration of use, and patient response to use.3,12,44 This not only protects the clinician legally, but also aids in future use of PS by having a reminder of effective procedures and patient reactions.1,8,13,26,27 PS devices should be maintained based on manufacturer’s recommendations.26 When not in use, immobilization devices should be stored in a closed space away from view in the event that the devices may invoke discomfort with sight.34

Conclusions

Access to dental care remains a significant issue for adult patients with SHCN. Access to care is currently somewhat limited due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The increase in alternative behavioral and pharmacologic modalities provides viable alternatives to the use of PS that are more readily accepted among clinicians, patients, and guardians than PS. PS may still facilitate a timely, safe, effective, and efficient means of completing dental care or obtaining an accurate assessment for necessary dental care when other alternatives are not available or feasible.

Patient safety, autonomy, and beneficence must be maintained when implementing PS by a trained and unified clinical team that understands the intentions and implications of PS. More research on the implications and effectiveness for use in adults is recommended with a focus on a customized decision-making and assessment strategy to elevate patient safety and clinician diligence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Mark MacEachern for assistance with the literature search for this scoping review.

DISCLOSURE

Grant support was received from NIH grant 1UL1TR003098–01 and UMB Institute for Clinical and Translational Research.

Contributor Information

Sydnee E. Chavis, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Maryland School of Dentistry, Baltimore, Maryland.

Erica Wu, Private Practice, Tustin, California.

Stephanie M. Munz, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery/Hospital Dentistry, University of Michigan School of Dentistry, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Reference Manual. Protective Stabilization for pediatric dental patients. Pediatr Dent 2018;40(special issue):268–73..32074898 [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry. Guidelines on Medical and Dental Procedure Stabilization. August 2017. Accessed 03 April 2020. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5cf7d27396d7760001307a44/t/5e825d339bb76a70f2ee4409/1585601845317/Med-Immobilization-Procedure-Stabilization-PolicyStatement.pdf.

- 3.Glassman P. A review of guidelines for sedation, anesthesia, and alternative interventions for people with special needs. Spec Care Dent. 2009;29(1):9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2008.00056.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Reference Manual. Guideline on Behavior Guidance. Pediatr Dent. 2015:37 (special issue): 266–279.26063555 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karibe H, Umezu Y, Hasegawa Y, et al. Factors affecting the use of protective stabilization in dental patients with cognitive disabilities. Spec Care Dent. 2008;28(5):214–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2008.00037.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez Mier EA, Walsh CR, Farah CC, Vinson LQA, Soto-Rojas AE, Jones JE. Acceptance of Behavior Guidance Techniques Used in Pediatric Dentistry by Parents From Diverse Backgrounds. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2019;58(9):977–984. doi: 10.1177/0009922819845897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Reference Manual. Management of dental patients with special health care needs. Pediatr Dent. 2018;40(special issue):237–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newton JT. Restrictive behaviour management procedures with people with intellectual disabilities who require dental treatment. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2009;22(2):118–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2008.00478.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis CW. Dental care and children with special health care needs: a population-based perspective. Acad Pediatr 2009;9(6):420–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center. 2018. Special Care: An Oral Health Professional’s Guide to Serving Young Children with Special Health Care Needs (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frankel RI. The Papoose Board and mothers’ attitudes following its use. Pediatr Dent. 1991;13(5):284–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glassman P, Caputo A, Dougherty N, et al. Special care dentistry association consensus statement on sedation, anesthesia, and alternative techniques for people with special needs. Spec Care Dent. 2009;29(1):2–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2008.00055.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romer M. Consent, restraint, and people with special needs: A review. Spec Care Dent. 2009;29(1):58–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2008.00063.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kupietzky A. Strap him down or knock him out: Is conscious sedation with restraint an alternative to general anaesthesia? Br Dent J. 2004;196(3):133–138. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4810932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa LR, Bendo CB, Daher A, et al. A curriculum for behaviour and oral healthcare management for dentally anxious children—Recommendations from the Children Experiencing Dental Anxiety: Collaboration on Research and Education (CEDACORE). Int J Paediatr Dent. 2020;(February):1–14. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adair SM, Schafer TE, Rockman RA, Waller JL. Survey of behavior management teaching in predoctoral pediatric dentistry programs. Pediatr Dent. 2004;26(2):143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White J, Wells M, Arheart KL, Donaldson M, Woods MA. A questionnaire of parental perceptions of conscious sedation in pediatric dentistry. Pediatr Dent. 2016;38(2):116–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weaver JM. Why is physical restraint still acceptable for dentistry? Anesth Prog. 2010;57(2):43–44. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-57.2.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bridgmann AM. Mental incapacity and restraint for treatment: Present law and proposals for reform. J Med Ethics. 2000;26(5):387–392. doi: 10.1136/jme.26.5.387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camoin A, Dany L, Tardieu C, Ruquet M, Le Coz P. Ethical issues and dentists’ practices with children with intellectual disability: A qualitative inquiry into a local French health network. Disabil Health J. 2018;11(3):412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peretz B, Gluck GM. The use of restraint in the treatment of paediatric dental patients: Old and new insights. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2002;12(6):392–397. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263X.2002.00395.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shuman SK, Bebeau MJ. Ethical and legal issues in special patient care. Dent Clin North Am. 1994;38(3):553–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Reference Manual. Guideline on informed consent. Pediatr Dent. 2016;38(special issue):351–353.27931476 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kupietzky A, Ram D. Effects of a positive verbal presentation on parental acceptance of passive medical stabilization for the dental treatment of young children. Pediatr Dent. 2005;27(5):380–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katrova LG, Freed JR, Coulter ID. Doctor-patient relationships in global society. Informed consent in dentistry. Folia med (Plovdiv) 2001:43(1–2):173–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dodds AP. Managing the Pediatric Dental Patient. Lecture presented at: Academy of Dental Learning & OSHA Training; 2017; Albany, NY, US. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Capacity Greening P., Consent and Dentistry - Who Decides and How Do They Do It? Prim Dent J. 2015;4(2):67–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Appelbaum PS. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp074045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinnersley P, Phillips K, et al. Interventions to promote informed consent for patients undergoing surgical and other invasive procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(7):CD009445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson OA, Wearne IMJ . Informed consent for elective surgery - What is best practice? J R Soc Med. 2007;100(2):97–100. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.100.2.97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Connick C, Palat M, Pugliese IS. The appropriate use of physical restraints: considerations. J Dent Child 2000;67:256–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romer M, Filanova V. Providing dental care to patients with developmental disabilities: medical/legal issues. New York State Dent J 2006;72(2): 36–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuman NJ, Williams NJ et al. Dentists charged with criminal assault and child abuse - an occupational hazard. J Public Health Dent. 1987;47:36. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson T. The Continuum of Behavior Guidance. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57(1):129–143. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davila JM. Restraint and sedation of a dental patient with developmental disabilities. Spec Care Dentist 1990;10(6):210–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burtner AP. Defensive strategies for the institutional dentist. Spec Care Dentist 1991;11(4):137–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirayama A, Fukuda K, Koukita Y, Ichinohe T. Effects of the addition of low-dose ketamine to propofol anesthesia in the dental procedure for intellectually disabled patients. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2019;19(3):151. doi: 10.17245/jdapm.2019.19.3.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saxen MA, Tom JW, Mason KP. Advancing the Safe Delivery of Office-Based Dental Anesthesia and Sedation: A Comprehensive and Critical Compendium. Anesthesiol Clin. 2019;37(2):333–348. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2019.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solomowitz BH. Treatment of Mentally Disabled Patients with Intravenous Sedation in a Dental Clinic Outpatient Setting. Dent Clin North Am. 2009;53(2):231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2008.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dougall A, Fiske J. Access to special care dentistry, part 3. Consent and capacity. Br Dent J. 2008;205(2):71–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Picciani BLS, Bausen AG, Michalski dos Santos B, et al. The challenges of dental care provision in patients with learning disabilities and special requirements during COVID-19 pandemic. Spec Care Dent. 2020;(May):2–4. doi: 10.1111/scd.12494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cruz S, Chi DL, Huebner CE. Oral health services within community-based organizations for young children with special health care needs. Spec Care Dentist. 2016;36(5):243–253. doi: 10.1111/scd.12174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee JY, Vann WF, Roberts MW. A cost analysis of treating pediatric dental patients using general anesthesia versus conscious sedation. Anesth Prog. 2001;48(3):82–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coté CJ, Wilson S, Casamassimo P, et al. Guidelines for monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures: An update. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2587–2602. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Acs G, Musson CA, Burke MJ. Current teaching of restraint and sedation in pediatric dentistry: a survey of program directors. Pediatr Dent. 1990;12(6):364–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crossley ML, Joshi G. An investigation of paediatric dentists’ attitudes towards parental accompaniment and behavioural management techniques in the UK. Br Dent J. 2002;192(9):517–521. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaccarino J. The Patient with Special Needs: General Treatment Considerations. Bloomingdale, Il; American Dental Assistants Association, 2017. “https://www.adaausa.org/Education/Online-Continuing-Education/View-Course/CourseId/9.” Accessed Dec 17, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 48.McWhorter AG, Townsend JA. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry Symposium. Behavior Symposium Workshop A Report - Current Guidelines/Revision.; 2014:Pediatr Dent;36(2):152–3.48. Contreras CI, Cervantes MJ. Behavior Management Techniques and Protective Stabilization in Pediatric Dentistry. Lecture presented at: Texas State Board of Dental Examiners at the University of Texas Health Science Center Dental School. April 8, 2017: San Antonio. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Contreras CI, Cervantes MJ. Behavior Management Techniques and Protective Stabilization in Pediatric Dentistry. Lecture presented at: Texas State Board of Dental Examiners at the University of Texas Health Science Center Dental School. April 8, 2017: San. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oliver K, Manton DJ. Contemporary behavior management techniques in clinical pediatric dentistry: Out with the old and in with the new? J Dent Child. 2015;82(1):22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]