Abstract

Background

Bladder cancer (BC) is the ninth most common malignant tumor. We constructed a risk signature using immune-related gene pairs (IRGPs) to predict the prognosis of BC patients.

Methods

The mRNA transcriptome, simple nucleotide variation and clinical data of BC patients were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (TCGA-BLCA). The mRNA transcriptome and clinical data were also extracted from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets (GSE31684). A risk signature was built based on the IRGPs. The ability of the signature to predict prognosis was analyzed with survival curves and Cox regression. The relationships between immunological parameters [immune cell infiltration, immune checkpoints, tumor microenvironment (TME) and tumor mutation burden (TMB)] and the risk score were investigated. Finally, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was used to explore molecular mechanisms underlying the risk score.

Results

The risk signature utilized 30 selected IRGPs. The prognosis of the high-risk group was significantly worse than that of the low-risk group. We used the GSE31684 dataset to validate the signature. Close relationships were found between the risk score and immunological parameters. Finally, GSEA showed that gene sets related to the extracellular matrix (ECM), stromal cells and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) were enriched in the high-risk group. In the low-risk group, we found a number of immune-related pathways in the enriched pathways and biofunctions.

Conclusions

We used a new tool, IRGPs, to build a risk signature to predict the prognosis of BC. By evaluating immune parameters and molecular mechanisms, we gained a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the risk signature. This signature can also be used as a tool to predict the effect of immunotherapy in patients with BC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-021-08486-0.

Keywords: Immune-related gene pairs, Bladder cancer, Prognosis, Immune cell infiltration, Immune checkpoints, Tumor microenvironment (TME), Tumor mutation burden (TMB)

Background

There were an estimated 80,470 new cases and 17,670 deaths as a result of bladder cancer (BC) in 2019, and BC is the ninth most common malignant tumor [1]. Nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) accounts for 75% of BCs, and 50% of NMIBC cases progress to muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) [2]. The main treatment for NMIBC is transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) followed by bladder irrigation, and the treatment strategy for MIBC is usually radical cystectomy combined with cisplatin chemotherapy [3]. The prognosis of patients with BC confined to the mucosa or submucosa is relatively good, and the 5-year survival rate is approximately 80%; however, the 5-year survival rate of BC patients with advanced metastasis is only 15%, and routine treatment has unsatisfactory effects [4, 5]. Therefore, it is essential to identify biomarkers that can reliably predict the prognosis of BC patients and to develop more effective targeted drugs to guide the treatment of BC.

An increasing number of studies have indicated that immune system disorders are closely related to tumorigenesis and development [6–8]. Therefore, immunotherapy has become a promising antitumor strategy in which the body’s own immune response is induced to recognize tumors as foreign antigens and inhibit the proliferation and metastasis of tumor cells by inducing active or passive immune effects [9, 10]. In the past few years, immunotherapy has changed the treatment of solid tumors, and numerous cancer patients have experienced durable responses and long-term survival benefits [11]. To date, Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) immunotherapy, the gold standard for high-risk NMIBC, has been the most successful; it induces inflammatory cell infiltration and cytokine production in the bladder mucosa, resulting in an immune response against tumor cells [12, 13]. For NMIBC patients with BCG failure, quadruple immunotherapy with BCG, interferon, interleukin-2 (IL-2) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GMCSF) has also demonstrated success [14]. However, side effects are very common with BCG, and more than 90% of patients have symptoms of cystitis [15, 16]. In addition, the in-depth study of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as inhibitors of programmed death-1 (PD-1), programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), has led to breakthroughs in immunotherapy [17]. In phase II clinical trials, neoadjuvant use of ICIs in patients with MIBC has shown pathological complete responses [18]. In summary, immunotherapy still has considerable potential in BC. In addition, tumor mutation burden (TMB), also defined as the total number of somatic coding errors, has been considered closely related to tumors [19]. Recent studies also confirmed that TMB was an essential biomarker to predict the effect of ICIs and immunotherapy in tumors, and the TMB level was significantly increased in responders [20–22].

In this study, we identified immune-related gene pairs (IRGPs) based on immune gene data downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. The IRGPs related to prognosis were selected to build a risk signature via least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox regression. A microarray dataset (GSE31684) obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database was used to validate the accuracy of the risk signature (Fig. 1). The relationship between the immunological parameters (immune cell infiltration, immune checkpoints, tumor microenvironment (TME) and TMB) and the risk score was investigated. Finally, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was used to explore the molecular mechanisms of the risk score.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the current study. BC, bladder cancer; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; IRGs, immune-related genes; IRGPs, immune-related gene pairs; TME, tumor microenvironment; TMB, tumor mutation burden; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis

Methods

Data acquisition

The mRNA transcriptome data, simple nucleotide variation and clinical information of patients with BC were downloaded from the TCGA database (TCGA-BLCA) (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). The mRNA transcriptome data and clinical information were also obtained from GSE31684 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). After excluding normal samples, 411 patient samples in the TCGA database were analyzed to build a risk signature for evaluating prognosis, and 93 patient samples in GSE31684 were used to validate the signature. A list of immune-related genes (IRGs) was obtained from the Immunology Database and Analysis Portal (ImmPort) [23]. The clinical information of BC patients in the TCGA and GSE31684 databases is shown in Table 1. Then, the TMB of each sample could be calculated as the number of somatic mutations counted in the total length of exons [24]. Moreover, an independent cohort of patients with metastatic urothelial cancer (mUC) receiving PD-1 blockade therapy, as described in the IMvigor210 (mUC) trial, was also included to validate our signature (the mRNA and clinical data were obtained from the package “IMvigor” of R software). The clinical information of BC patients in the TCGA and GSE31684 databases is shown in Table 2. The need for ethical approval was waived because the data we used were obtained from public databases.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients obtained from the TCGA database and GSE31684

| Basic information | TCGA (n = 409) | GSE31684 (n = 72) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 69 (median) | 68.015 (median) | |

| Gender | Female | 106 | 55 |

| Male | 303 | 17 | |

| Grade | High | 385 | 69 |

| Low | 21 | 3 | |

| Unknow | 3 | – | |

| Stage | I & II | 132 | 14 |

| III & IV | 275 | 58 | |

| Unknow | 2 | – | |

| T classification | T1 & T2 | 124 | 22 |

| T3 & T4 | 253 | 50 | |

| TX | 1 | – | |

| Unknow | 31 | – | |

| N classification | N0 | 237 | 44 |

| N1 &N2 & N3 | 131 | 28 | |

| NX | 36 | – | |

| Unknow | 5 | – | |

| M classification | M0 | 194 | 41 |

| M1 | 11 | 31 | |

| MX | 202 | – | |

| Unknow | 2 | – |

BC bladder cancer, TCGA the The Cancer Genome Atlas

Table 2.

Characteristics of the patients obtained from the IMvigor210

| Basic information | IMvigor210 (n = 348) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Less than 1 year | 176 |

| 1–2 years | 99 | |

| More than 2 years | 73 | |

| Gender | Female | 76 |

| Male | 272 | |

| Subtype | I & II | 213 |

| III & IV | 135 | |

| Response | CR/PR | 68 |

| SD/PD | 230 | |

| NA | 50 |

BC bladder cancer, CR complete response, PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease

IRGPs

We paired the IRGs in each sample and compared the expression between the two. If the expression of the first IRG was higher than the expression of the second IRG, the value of the IRGP was 1; otherwise, the value was 0 [25]. Then, the gene pairs whose ratio was 0 to 1 in less than 20% of samples were deleted to retain gene pairs that might be related to survival [26].

The risk signature

These IRGPs and the survival time were considered for further analysis. IRGPs significantly related to prognosis were identified via univariate Cox regression (P < 0.05). The risk signature was constructed via LASSO regression, and the number of variables included was reduced and overfitting was effectively avoided by constructing a penalty function. The penalty parameter (λ), a hyperparameter for the risk signature, was determined by tenfold cross-validation following the lowest partial likelihood deviance. The IRGPs included in the risk signature and the corresponding coefficients were obtained through the determined λ value. The risk score was calculated based on the coefficients. The appropriate cutoff value for dividing BC patients into a high-risk group and a low-risk group was determined via the TCGA database by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The accuracy of the risk signature was also estimated via ROC curve analysis. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the log-rank test were used to compare the overall survival (OS) between the high-risk group and the low-risk group. Then, univariate and multivariate Cox regression were performed to evaluate whether the risk score was an independent predictor of poor OS in BC patients. Subgroup analyses were performed to prove the robustness of the signature. The GSE31684 and IMvigor210 cohorts were used to validate the signature. In addition, the immune-related signatures from six other articles were compared with the current IRGP signature [27–32].

Immune parameters

To assess immune infiltration in different risk groups, cell type identification by estimating relative subsets of RNA transcripts (CIBERSORT) was used. CIBERSORT is a deconvolution algorithm that can predict the abundance of 22 immune cells, including naïve B cells, memory B cells, plasma cells, CD8 T cells, naïve CD4 T cells, and resting CD4 memory T cells, based on gene expression profiles (GEPs) [33–35]. The GEPs from the TCGA database were uploaded and used to analyze immune cell infiltration.

The relationship between the risk score and the expression of common immune checkpoints in BC was estimated, including PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA4, lymphocyte activating 3 (LAG3), B and T lymphocyte associated (BTLA) and hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2 (HAVCR2).

The immune score (the infiltration level of immune cells), the stromal score (the infiltration of stromal cells) and tumor purity were calculated using the GEPs of TCGA database via Estimation of Stromal and Immune cells in Malignant Tumor tissues using Expression data (ESTIMATE) to explore the TME further [36, 37]. Then, we investigated the relationship between the risk score and the results of ESTIMATE. The impacts of the immune score and stromal score on the survival of all BC patients were also evaluated via the Kaplan–Meier method. Finally, we assessed whether there was a correlation between the risk score and the TMB.

The GSE31684 and publicly available “IMvigor210” datasets were used to perform the same analysis to determine the changes in immune parameters and risk score.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

In the current study, we used GSEA to explore the molecular mechanisms underlying the risk score. The gene sets of “c2.cp.kegg.v7.1.symbols.gmt” and “c5.go.v7.2.symbols.gmt” from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) were downloaded for further analysis. The phenotype labels were high-risk group and low-risk group. Normalized enrichment scores (NESs), the nominal P value (NOM P value) and the false discovery rate Q value (FDR Q value) were acquired. NOM P value < 0.05 and FDR Q value < 0.25 were considered to indicate significant enrichment.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R 4.03 software. The log-rank test and univariate and multivariate Cox regression were completed via the survival package of R. LASSO Cox regression was performed via the glmnet package of R. All ROC curves were generated via the survival ROC package of R. The nomogram and the calibration were illustrated via the rms package of R. ESTIMATE analysis was achieved via the estimate package of R. Fisher’s exact tests were used to estimate differences in clinical variables between the groups in the TCGA database. Pearson test was used for all correlation analysis.

Results

Construction of the IRGP signature

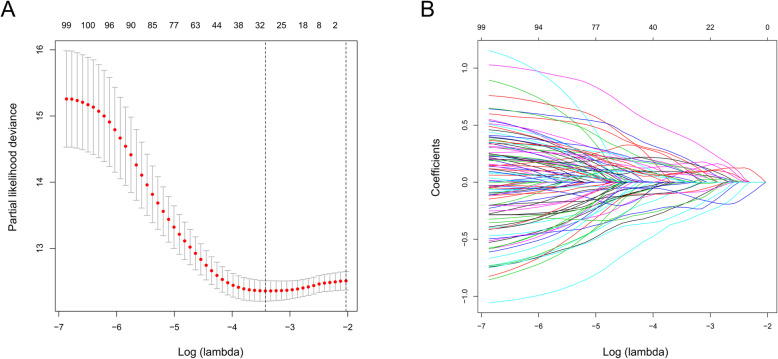

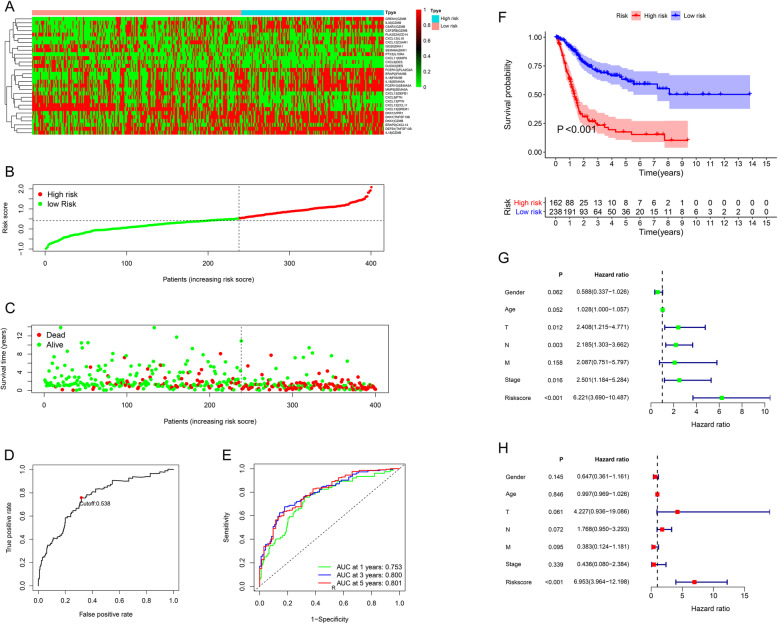

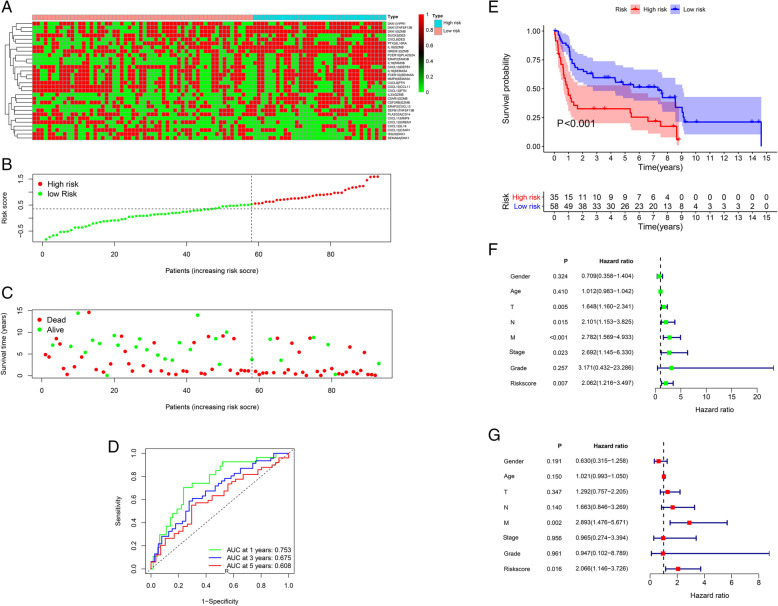

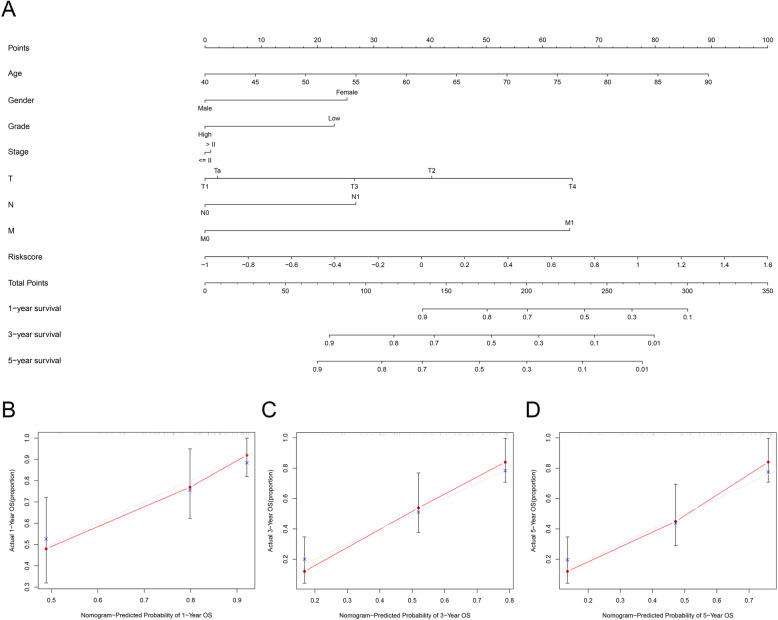

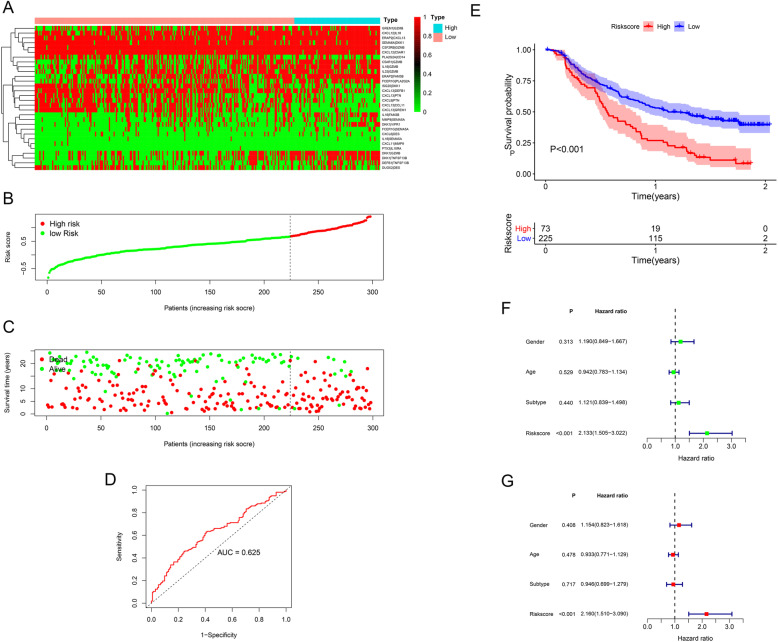

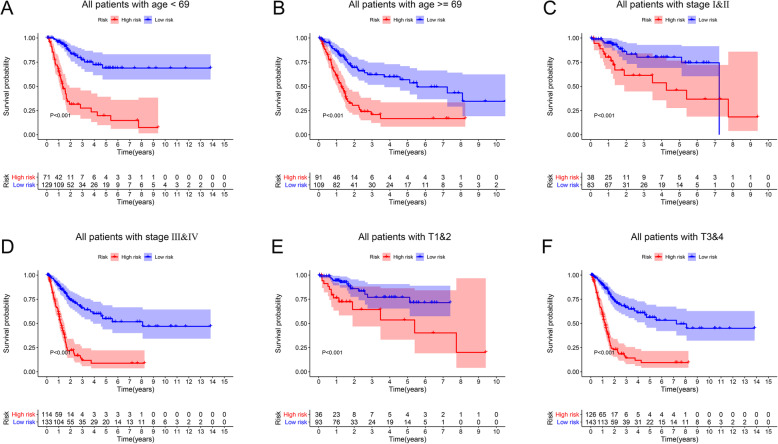

After filtering out unqualified IRGPs, 652 IRGPs remained. Then, 104 IRGPs significantly related to prognosis were identified via univariate Cox regression (P < 0.05) and used as candidate pairs for signature building. The risk score was calculated based on the coefficients of the selected IRGPs obtained from LASSO Cox regression (the optimal λ was 0.03253915) (Fig. 2A-B). Ultimately, 30 IRGPs were included in the risk signature (Table 3, Fig. 3A-C). Through ROC curve analysis, the cutoff value that divided BC patients into the high-risk group and low-risk group was determined to be 0.538 (Fig. 3D). The ROC curve results showed a moderate prognostic power of the risk score [area under the curve (AUC) at 1 year = 0.758, AUC at 3 years = 0.800, AUC at 5 years = 0.801] (Fig. 3E). The results of Kaplan-Meier survival analyses and Fisher’s exact tests revealed that a high risk score was significantly correlated with advanced age (P = 0.021), advanced clinical stage (P < 0.001), high T classification (P = 0.007), high N classification (P = 0.002), high M classification (P < 0.001) and poor OS (P < 0.001) (Table 4, Fig. 3F). Univariate Cox regression showed that T stage [hazard ratio (HR) = 2.408, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.215–4.771, P = 0.012], N stage (HR = 2.185, 95% CI = 1.303–3.662, P = 0.003), clinical stage (HR = 2.501, 95% CI = 1.184–5.284, P = 0.016) and risk score (HR = 6.221, 95% CI = 3.690–10.487, P < 0.001) were closely related to poor prognosis in BC (Fig. 3G). We then performed multivariate Cox regression, which identified only the risk score as associated with prognosis (HR = 6.953, 95% CI = 3.964–12.198, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3H). The nomogram could predict the survival probability of 1-year, 3-year and 5-year OS (Fig. 4A). The calibration curve revealed the accuracy of the prediction using the nomogram (Fig. 4B-D). To validate that the risk signature performed similarly for other datasets, the independent cohort from the GSE31684 dataset was employed for external validation. We divided BC patients from GSE31684 into a high-risk group and a low-risk group (Fig. 5A-C). The ROC curve results showed a moderate prognostic power for BC patients of the risk score (AUC at 1 year = 0.753, AUC at 3 years = 0.675, AUC at 5 years = 0.608) (Fig. 5D). Kaplan-Meier curves revealed that the prognosis of the high-risk group was worse than that of the low-risk group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5E). The Cox regression results indicated that the risk score was an independent predictor of poor OS in BC (Fig. 5F-G). The nomogram could predict the survival probability of 1-year, 3-year and 5-year OS (Fig. 6A). The calibration curve revealed the accuracy of the prediction using the nomogram (Fig. 6B-D). Another cohort from the IMvigor210 dataset was also subjected to the same analysis to validate the signature (Fig. 7A-G). A series of subgroup analyses performed on data from the TCGA (Fig. 8A-F), GSE31684 (Supplementary Fig. S1A-F) and IMvigor210 (Supplementary Fig. S2A-D) indicated that the risk signature was robust.

Fig. 2.

Construction of the IRGP signature by LASSO regression analysis. LASSO coefficient profiles of the included genes in TCGA-BLCA (A). Selection of the optimal parameter (λ) in the LASSO model for TCGA-BLCA (B). LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; BLCA, bladder cancer; IRGP, immune-related gene pair

Table 3.

Information on the 30 selected IRGPs

| Gena pair 1 | Full name | Gene pair 2 | Full name | Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCER1G | Fc fragment of IgE receptor Ig | PLA2G2A | phospholipase A2 group IIA | 0.115 |

| FCER1G | Fc fragment of IgE receptor Ig | SEMA5A | semaphorin 5A | 0.085 |

| ERAP2 | endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 2 | CXCL13 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 13 | 0.025 |

| ERAP2 | endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 2 | FAM3B | FAM3 metabolism regulating signaling molecule B | 0.390 |

| CXCL9 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9 | PTN | pleiotrophin | −0.182 |

| CXCL11 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 11 | MMP9 | matrix metallopeptidase 9 | −0.334 |

| CXCL6 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 6 | DES | desmin | −0.055 |

| CXCL12 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 | IL18 | interleukin 18 | 0.210 |

| CXCL12 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 | C5AR1 | complement C5a receptor 1 | 0.128 |

| CXCL13 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 13 | DEFB1 | defensin beta 1 | −0.010 |

| CXCL13 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 13 | CCL11 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 11 | −0.087 |

| CXCL13 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 13 | GREM1 | gremlin 1, DAN family BMP antagonist | −0.112 |

| CXCL13 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 13 | PTN | pleiotrophin | −0.254 |

| DEFB1 | defensin beta 1 | TNFSF13B | TNF superfamily member 13b | 0.183 |

| MMP9 | matrix metallopeptidase 9 | SEMA5A | semaphorin 5A | 0.164 |

| ISG20 | interferon stimulated exonuclease gene 20 | DKK1 | dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1 | −0.183 |

| DUOX2 | dual oxidase 2 | DES | desmin | −0.090 |

| PLA2G2A | phospholipase A2 group IIA | CD14 | CD14 molecule | −0.221 |

| IL18 | interleukin 18 | SEMA5A | semaphorin 5A | 0.066 |

| IL18 | interleukin 18 | FAM3B | FAM3 metabolism regulating signaling molecule B | 0.087 |

| IL18 | interleukin 18 | GZMB | granzyme B | 0.124 |

| PTX3 | pentraxin 3 | IL10RA | interleukin 10 receptor subunit alpha | 0.173 |

| SEMA6A | semaphorin 6A | DKK1 | dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1 | −0.057 |

| C5AR1 | complement C5a receptor 1 | GZMB | granzyme B | 0.091 |

| DKK1 | dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1 | TNFSF13B | TNF superfamily member 13b | 0.084 |

| DKK1 | dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1 | VIPR1 | vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 1 | 0.007 |

| DKK1 | dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1 | GZMB | granzyme B | 0.097 |

| GREM1 | gremlin 1, DAN family BMP antagonist | GZMB | granzyme B | 0.082 |

| IL33 | interleukin 33 | GZMB | granzyme B | 0.009 |

| CSF2RB | colony stimulating factor 2 receptor subunit beta | GZMB | granzyme B | < 0.001 |

Fig. 3.

Characteristics of the IRGP signature using the TCGA. The score of included IRGPs in different groups (A). The categorization of BC patients into different groups (B). The survival status of patients in the high-risk group and low-risk group (C). Through ROC curve analysis, the cutoff value for dividing BC patients into the high-risk group and the low-risk group was determined to be 0.538 (D). The AUC of the ROC curve results showed a moderate prognostic power of the risk score (E). The results of Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed that a high-risk score was significantly related to poor OS (F). Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses demonstrated that the risk score was an independent prognostic factor (G-H). TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; BLCA, bladder cancer; BC, bladder cancer; IRGPs, immune-related gene pairs; AUC, area under curve; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; OS, overall survival

Table 4.

Differences in the characteristics of BC patients between the high risk and low risk in TCGA

| Basic information | Low risk | High risk | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.021 | |||

| ≤ 69 | 138 | 75 | ||

| > 69 | 100 | 87 | ||

| Gender | 0.143 | |||

| Female | 55 | 48 | ||

| Male | 183 | 114 | ||

| Stage | < 0.001 | |||

| I&II | 93 | 36 | ||

| III&IV | 143 | 126 | ||

| T | 0.007 | |||

| T1&T2 | 83 | 38 | ||

| T3&T4 | 133 | 114 | ||

| N | 0.002 | |||

| N0 | 152 | 81 | ||

| N1–3 | 61 | 65 | ||

| M | < 0.001 | |||

| M0 | 132 | 61 | ||

| M1 | 2 | 9 |

Fig. 4.

Nomogram (TCGA). The nomogram could predict the probability of 1-year, 3-year and 5-year OS (A). The calibration curve revealed the accuracy of the nomogram for predicting 1-year (B), 3-year (C) and 5-year (D) OS. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; OS, overall survival

Fig. 5.

Validation of the IRGP signature using GSE31684. The score of included IRGPs in different groups (A). The categorization of BC patients into different groups (B). The survival status of patients in the high-risk group and low-risk group (C). The AUC of the ROC curve results showed a moderate prognostic power of the risk score (D). The results of Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed that a high-risk score was significantly related to poor OS (E). Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses demonstrated that the risk score was an independent prognostic factor (F-G). BC, bladder cancer; IRGPs, immune-related gene pairs; AUC, area under the curve; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; OS, overall survival

Fig. 6.

Nomogram (GEO). The nomogram could predict the survival probability of 1-year, 3-year and 5-year OS (A). The calibration curve revealed the accuracy of the nomogram for predicting 1-year (B), 3-year (C) and 5-year (D) OS. GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; OS, overall survival

Fig. 7.

Validation of the IRGP signature using IMvigor210. The scores of the included IRGPs in different groups (A). The categorization of BC patients into different groups (B). The survival status of patients in the high-risk group and low-risk group (C). The AUC of the ROC curve results showed that the risk score had moderate prognostic power (D). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed that a high risk score was significantly related to poor OS (E). Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses demonstrated that the risk score was an independent prognostic factor (F-G). BC, bladder cancer; IRGPs, immune-related gene pairs; AUC, area under the curve; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; OS, overall survival

Fig. 8.

Subgroup analyses (TCGA). Subgroup analyses were performed based on age (A-B), clinical stage (C-D) and T stage (E-F) to confirm the robustness of the risk signature. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas

A comparison of the current model with the previous model by using data from the TCGA (Fig. 9A-C), GEO (Fig. 9D-F) and IMvigor210 (Fig. 9G), revealed that the model had acceptable accuracy, with the largest AUC value obtained with data from the TCGA.

Fig. 9.

Comparison of signatures. AUC for multiple signatures at 1 year (A), 3 years (B), and 5 years (C) using TCGA datasets via ROC curves. AUC for multiple signatures at 1 year (D), 3 years (E), and 5 years (F) using GEO datasets via ROC curves. AUC for multiple signatures at 1 year (G) using IMvigor210 datasets via ROC curves. AUC, area under the curve; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; IRGPs, immune-related gene pairs; IRGs, immune-related gene; IRLncRNA, immune-related long non-coding RNA

Evaluation of immune parameters

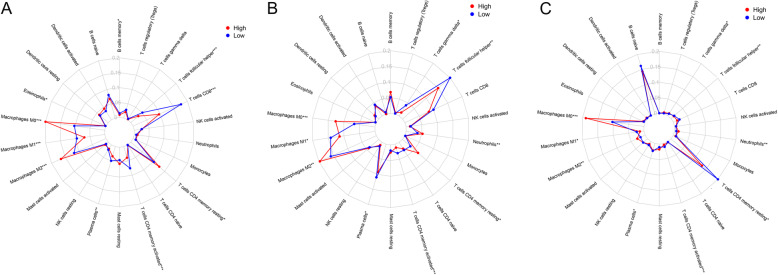

CIBERSORT was used to evaluate immune cell infiltration in different risk groups. The results were visualized by radar plot. Memory B cell memory, resting memory CD4 T cells, eosinophils, plasma cells, CD8 T cells, activated memory CD4 T cells, follicular helper T cells, M0 macrophages, M1 macrophages and M2 macrophages were differentially enriched in the different risk groups. The levels of memory B cells (P = 0.040), plasma cells (P = 0.006), M1 macrophages (P < 0.001), CD8 T cells (P < 0.001), activated memory CD4 T cells (P < 0.001) and follicular helper T cells (P < 0.001) were higher in the low-risk group than in the high-risk group. The levels of M0 macrophages (P < 0.001), M2 macrophages (P < 0.001), eosinophils (P = 0.031) and resting memory CD4 T cells (P = 0.022) were higher in the high-risk group than in the low-risk group (Fig. 10A). The other two datasets, GSE31684 (Fig. 10B) and IMvigor210 (Fig. 10C), were used to verify the related changes in immune cells in the TCGA database. The results obtained from the three datasets were mostly consistent.

Fig. 10.

Immune cells and risk scores. In the TCGA, the levels of memory B cells, plasma cells, M1 macrophages, CD8 T cells, activated CD4 memory T cells and follicular helper T cells were higher in the low-risk group than in the high-risk group, and the levels of M0 macrophages, M2 macrophages, eosinophils and resting CD4 memory T cells were higher in the high-risk group than in the low-risk group (A). The other two databases, GSE31684 (B) and IMvigor210 (C), were used to verify the related changes in immune cells in the TCGA database. The results obtained from the three datasets were mostly consistent. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001

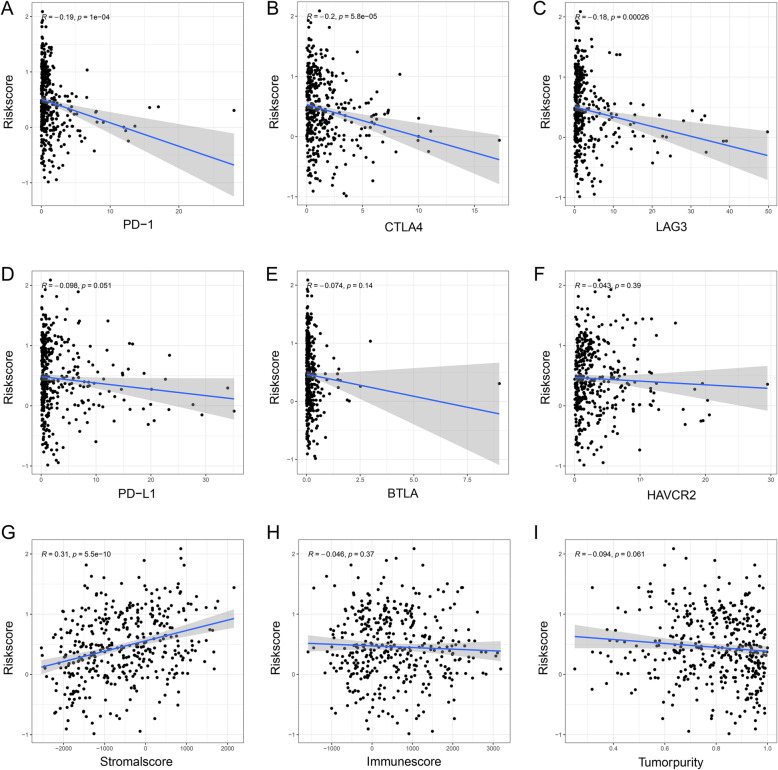

Then, the relationship between the risk score and the expression of common immune checkpoints in BC was explored. We found that the expression levels of PD-1 (correlation coefficient = − 0.19, P < 0.001) (Fig. 11A), CTLA4 (correlation coefficient = − 0.20, P < 0.001) (Fig. 11B), and LAG3 (correlation coefficient = − 0.18, P < 0.001) (Fig. 11C) were significantly negatively correlated with the risk score. However, there was no significant difference between the risk score and other immune checkpoints, including PD-L1 (correlation coefficient = − 0.098, P = 0.051) (Fig. 11D), BTLA (correlation coefficient = − 0.74, P = 0.140) (Fig. 11E), and HAVCR2 (correlation coefficient = − 0.043, P = 0.390) (Fig. 11F). We also confirmed that the stromal score was significantly positively correlated with the risk score (correlation coefficient = 0.31, P < 0.001) (Fig. 11G). However, there was no significant correlation between the immune score and tumor purity (correlation coefficient = − 0.046, P = 0.370) (Fig. 11H) or risk score (correlation coefficient = − 0.094, P = 0.061) (Fig. 11I). The related immune changes were also observed using GSE31684 (Supplementary Fig. S3A-I) and IMvigor210 (Supplementary Fig. S4A-I). The results obtained from the three datasets were mostly consistent.

Fig. 11.

Immunological parameters and risk scores (TCGA). The expression levels of PD-1 (A), CTLA4 (B), and LAG3 (C) were significantly negatively correlated with the risk score. However, there was no significant difference between the risk score and other immune checkpoints, including PD-L1 (D), BTLA (E), and HAVCR2 (F). The stromal score (G) was significantly positively correlated with the risk score. There was no significant correlation between the immune score (H), tumor purity (I) and risk score. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; PD-1, programmed death-1; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4; LAG3, lymphocyte activating 3; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; BTLA, B and T lymphocyte associated; HAVCR2, hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2; BC, bladder cancer

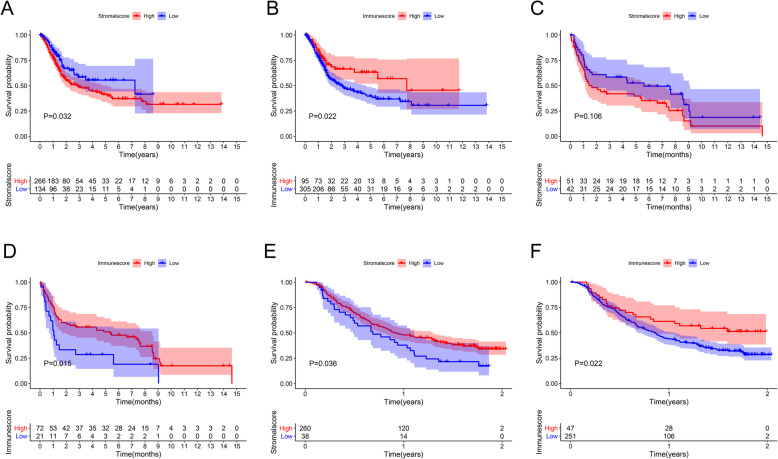

A high stromal score (P = 0.032) (Fig. 12A) and a low immune score indicated a poor prognosis in BC (P = 0.022) (Fig. 12B). We performed the same survival analysis using GSE31684 (Fig. 12C-D) and IMvigor210 (Fig. 12E-F). The results obtained from the three datasets revealed that a high immune score was closely correlated with a good prognosis.

Fig. 12.

Immune microenvironment and prognosis. A high stromal score (A) and a low immune score (B) indicated a poor prognosis in the TCGA. We performed the same survival analysis using GSE31684 (C-D) and IMvigor210 (E-F). The results obtained from the three datasets revealed that a high immune score was closely related to a good prognosis. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas

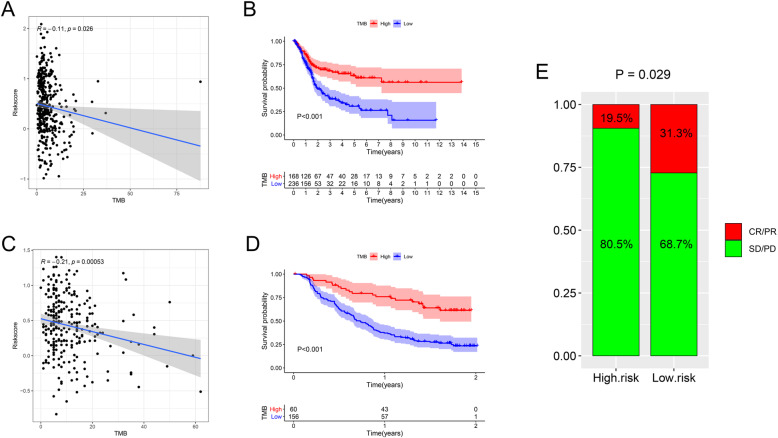

In the TCGA, the level of TMB was significantly negatively correlated with the risk score (correlation coefficient = − 0.11, P = 0.026) (Fig. 13A), and an increased level of TMB correlated with improved OS (P < 0.001) (Fig. 13B). These results were consistent with the results obtained from IMvigor210 (Fig. 13C-D). Moreover, in the IMvigor210 cohort, low-risk patients had more significant immunotherapy effects (PD-1 blockade therapy) (Fig. 13E).

Fig. 13.

TMB. In the TCGA, the level of TMB was significantly negatively correlated with the risk score (A), and an increased level of TMB correlated with improved OS (P < 0.001) (B). These results were consistent with the results obtained from IMvigor210 (C-D). Moreover, in the IMvigor210 cohort, low-risk patients had more significant immunotherapy effects (PD-1 blockade therapy) (E). TMB, tumor mutation burden; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; OS, overall survival; CR, complete response, PR, partial response, SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease

GSEA

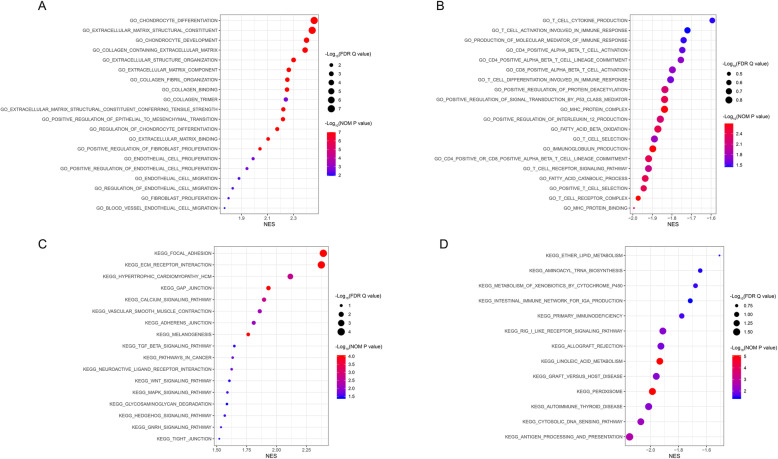

We used GSEA to explore the molecular mechanisms underlying the risk score. The Gene Ontology (GO) results, as shown in Table 5 and Fig. 14A, revealed the most significant signaling pathways enriched in the high-risk phenotype. The GO results, as shown in Table 6 and Fig. 14B, revealed the most significant signaling pathways enriched in the low-risk phenotype. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) results, as shown in Table 7 and Fig. 14C, revealed the most significant signaling pathways enriched in the high-risk phenotype. The KEGG results, as shown in Table 8 and Fig. 14D, revealed the most significant signaling pathways enriched in the low-risk phenotype [38].

Table 5.

Gene sets enriched in the high risk phenotype via GO

| Gene set name | NES | NOM p-val | FDR q-val |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO_CHONDROCYTE_DIFFERENTIATION | 2.459 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| GO_EXTRACELLULAR_MATRIX_STRUCTURAL_CONSTITUENT | 2.444 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| GO_CHONDROCYTE_DEVELOPMENT | 2.400 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| GO_COLLAGEN_CONTAINING_EXTRACELLULAR_MATRIX | 2.389 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| GO_EXTRACELLULAR_STRUCTURE_ORGANIZATION | 2.301 | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

| GO_EXTRACELLULAR_MATRIX_COMPONENT | 2.264 | < 0.001 | 0.002 |

| GO_COLLAGEN_FIBRIL_ORGANIZATION | 2.253 | < 0.001 | 0.002 |

| GO_COLLAGEN_BINDING | 2.250 | < 0.001 | 0.002 |

| GO_COLLAGEN_TRIMER | 2.241 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| GO_EXTRACELLULAR_MATRIX_STRUCTURAL_CONSTITUENT_CONFERRING_TENSILE_STRENGTH | 2.222 | < 0.001 | 0.003 |

| GO_POSITIVE_REGULATION_OF_EPITHELIAL_TO_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION | 2.219 | < 0.001 | 0.003 |

| GO_REGULATION_OF_CHONDROCYTE_DIFFERENTIATION | 2.175 | < 0.001 | 0.005 |

| GO_EXTRACELLULAR_MATRIX_BINDING | 2.105 | < 0.001 | 0.011 |

| GO_POSITIVE_REGULATION_OF_FIBROBLAST_PROLIFERATION | 2.042 | < 0.001 | 0.018 |

| GO_ENDOTHELIAL_CELL_PROLIFERATION | 1.990 | 0.002 | 0.024 |

| GO_POSITIVE_REGULATION_OF_ENDOTHELIAL_CELL_PROLIFERATION | 1.942 | 0.002 | 0.031 |

| GO_ENDOTHELIAL_CELL_MIGRATION | 1.881 | 0.006 | 0.040 |

| GO_REGULATION_OF_ENDOTHELIAL_CELL_MIGRATION | 1.833 | 0.006 | 0.049 |

| GO_FIBROBLAST_PROLIFERATION | 1.801 | 0.006 | 0.056 |

| GO_BLOOD_VESSEL_ENDOTHELIAL_CELL_MIGRATION | 1.770 | 0.011 | 0.063 |

Gene sets with NOM p-val < 0.05 and FDR q-val < 0.25 were considered significant

GO Gene Ontology, NES normalized enrichment score, NOM nominal, FDR false discovery rate

Fig. 14.

GSEA. Gene sets enriched in the high-risk phenotype via GO (A). Gene sets enriched in the low-risk phenotype via GO (B). Gene sets enriched in the high-risk phenotype via KEGG (C). Gene sets enriched in the low-risk phenotype via KEGG (D). GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; NES, normalized enrichment scores; NOM P value, nominal P value; FDR Q value, false discovery rate Q value

Table 6.

Gene sets enriched in the low risk phenotype via GO

| Gene set name | NES | NOM p-val | FDR q-val |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO_T_CELL_CYTOKINE_PRODUCTION | −1.594 | 0.034 | 0.227 |

| GO_T_CELL_ACTIVATION_INVOLVED_IN_IMMUNE_RESPONSE | −1.721 | 0.036 | 0.195 |

| GO_PRODUCTION_OF_MOLECULAR_MEDIATOR_OF_IMMUNE_RESPONSE | −1.740 | 0.034 | 0.192 |

| GO_CD4_POSITIVE_ALPHA_BETA_T_CELL_ACTIVATION | −1.747 | 0.028 | 0.188 |

| GO_CD4_POSITIVE_ALPHA_BETA_T_CELL_LINEAGE_COMMITMENT | −1.754 | 0.019 | 0.183 |

| GO_CD8_POSITIVE_ALPHA_BETA_T_CELL_ACTIVATION | − 1.798 | 0.019 | 0.160 |

| GO_T_CELL_DIFFERENTIATION_INVOLVED_IN_IMMUNE_RESPONSE | −1.807 | 0.024 | 0.161 |

| GO_POSITIVE_REGULATION_OF_PROTEIN_DEACETYLATION | −1.836 | 0.006 | 0.146 |

| GO_POSITIVE_REGULATION_OF_SIGNAL_TRANSDUCTION_BY_P53_CLASS_MEDIATOR | −1.838 | 0.004 | 0.149 |

| GO_MHC_PROTEIN_COMPLEX | −1.838 | 0.002 | 0.150 |

| GO_POSITIVE_REGULATION_OF_INTERLEUKIN_12_PRODUCTION | −1.859 | 0.006 | 0.146 |

| GO_FATTY_ACID_BETA_OXIDATION | −1.872 | 0.004 | 0.147 |

| GO_T_CELL_SELECTION | −1.889 | 0.017 | 0.156 |

| GO_IMMUNOGLOBULIN_PRODUCTION | −1.898 | 0.002 | 0.163 |

| GO_CD4_POSITIVE_OR_CD8_POSITIVE_ALPHA_BETA_T_CELL_LINEAGE_COMMITMENT | −1.919 | 0.004 | 0.157 |

| GO_T_CELL_RECEPTOR_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | −1.920 | 0.008 | 0.161 |

| GO_FATTY_ACID_CATABOLIC_PROCESS | −1.936 | 0.004 | 0.168 |

| GO_POSITIVE_T_CELL_SELECTION | −1.944 | 0.004 | 0.194 |

| GO_T_CELL_RECEPTOR_COMPLEX | −1.972 | 0.002 | 0.260 |

| GO_MHC_PROTEIN_BINDING | −1.994 | 0.006 | 0.369 |

Gene sets with NOM p-val < 0.05 and FDR q-val < 0.25 were considered significant

GO Gene Ontology, NES normalized enrichment score, NOM nominal, FDR false discovery rate

Table 7.

Gene sets enriched in the high risk phenotype via KEGG

| Gene set name | NES | NOM p-val | FDR q-val |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG_FOCAL_ADHESION | 2.390 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| KEGG_ECM_RECEPTOR_INTERACTION | 2.374 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| KEGG_HYPERTROPHIC_CARDIOMYOPATHY_HCM | 2.115 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| KEGG_GAP_JUNCTION | 1.932 | < 0.001 | 0.027 |

| KEGG_CALCIUM_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 1.896 | 0.002 | 0.031 |

| KEGG_VASCULAR_SMOOTH_MUSCLE_CONTRACTION | 1.860 | 0.006 | 0.035 |

| KEGG_ADHERENS_JUNCTION | 1.809 | 0.008 | 0.042 |

| KEGG_MELANOGENESIS | 1.763 | < 0.001 | 0.057 |

| KEGG_TGF_BETA_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 1.648 | 0.031 | 0.114 |

| KEGG_PATHWAYS_IN_CANCER | 1.633 | 0.017 | 0.118 |

| KEGG_NEUROACTIVE_LIGAND_RECEPTOR_INTERACTION | 1.625 | 0.017 | 0.119 |

| KEGG_WNT_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 1.606 | 0.034 | 0.117 |

| KEGG_MAPK_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 1.590 | 0.028 | 0.123 |

| KEGG_GLYCOSAMINOGLYCAN_DEGRADATION | 1.586 | 0.038 | 0.121 |

| KEGG_PROGESTERONE_MEDIATED_OOCYTE_MATURATION | 1.572 | 0.041 | 0.126 |

| KEGG_HEDGEHOG_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 1.568 | 0.030 | 0.124 |

| KEGG_GNRH_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | 1.537 | 0.028 | 0.137 |

| KEGG_TIGHT_JUNCTION | 1.522 | 0.039 | 0.138 |

Gene sets with NOM p-val < 0.05 and FDR q-val < 0.25 were considered significant

KEGG The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, NES normalized enrichment score, NOM nominal, FDR false discovery rate

Table 8.

Gene sets enriched in low risk phenotype via KEGG

| Gene set name | NES | NOM p-val | FDR q-val |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG_PEROXISOME | −1.986 | < 0.001 | 1.467 |

| KEGG_LINOLEIC_ACID_METABOLISM | −1.934 | < 0.001 | 1.397 |

| KEGG_ANTIGEN_PROCESSING_AND_PRESENTATION | −2.150 | 0.002 | 1.568 |

| KEGG_CYTOSOLIC_DNA_SENSING_PATHWAY | −2.070 | 0.004 | 1.419 |

| KEGG_RIG_I_LIKE_RECEPTOR_SIGNALING_PATHWAY | −1.912 | 0.008 | 1.425 |

| KEGG_AUTOIMMUNE_THYROID_DISEASE | −2.013 | 0.008 | 1.479 |

| KEGG_GRAFT_VERSUS_HOST_DISEASE | −1.959 | 0.008 | 1.425 |

| KEGG_ALLOGRAFT_REJECTION | −1.926 | 0.012 | 1.431 |

| KEGG_PRIMARY_IMMUNODEFICIENCY | −1.777 | 0.028 | 1.053 |

| KEGG_METABOLISM_OF_XENOBIOTICS_BY_CYTOCHROME_P450 | −1.678 | 0.030 | 0.943 |

| KEGG_ETHER_LIPID_METABOLISM | −1.507 | 0.031 | 0.691 |

| KEGG_AMINOACYL_TRNA_BIOSYNTHESIS | −1.645 | 0.036 | 0.895 |

| KEGG_INTESTINAL_IMMUNE_NETWORK_FOR_IGA_PRODUCTION | −1.716 | 0.039 | 0.969 |

Gene sets with NOM p-val < 0.05 and FDR q-val < 0.25 are considered as significant

KEGG The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, NES normalized enrichment score, NOM nominal, FDR false discovery rate

Discussion

BC is the most common malignant tumor of the urinary system and has complex biological behavior, a high recurrence rate and a high metastasis rate [39]. Among the BC treatments being studied, immunotherapy seems to be the most promising [40]. In 1990, BCG was approved for immunotherapy for BC and achieved great success, but it should be recognized that approximately 40% of BC patients have no response to BCG, and even 15% of BCs progress to MIBC after treatment [41, 42]. In recent years, new findings have suggested that tumor cells can escape the immune response by affecting immune checkpoints [43, 44]. Therefore, research on ICIs to prevent immune escape is receiving much attention at present [45–47]. Five ICIs, pembrolizumab, nivolumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab and avelumab, have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of advanced and metastatic BC [48]. One study indicated that in PD-L1-positive BC patients, durvalumab showed controlled safety and meaningful clinical activity [49]. In summary, the immunology of BC is worthy of further exploration. Importantly, in this study, we constructed a prognostic risk signature by using IRGPs, which is significant for furthering the understanding of the immune response in BC.

In general, GEPs identified from large public databases can be used to build risk signatures. However, there are many deficiencies in traditional construction schemes. The overfitting of a small sample training set and lack of sufficient verification can reduce the accuracy of statistics [50]. In some public databases, such as TCGA, the number of tumor samples is far greater than that of normal samples, and paired data are scarce [51]. If a model is constructed by screening differentially expressed genes (tumor vs normal), its robustness is doubtful. This problem can be solved by jointly considering GEPs from multiple databases. Unfortunately, the data from multiple platforms are difficult to standardize because of biological heterogeneity and technical biases [52]. Hence, we built our risk signature using IRGPs, which were identified based on the relative ranking and pairwise comparison of gene expression within the same patient, thus overcoming the batch effects encountered when data from different platforms are analyzed [25, 53]. Additionally, this new method also avoids issues related to an imbalance between the numbers of tumor samples and normal samples. Some tumor studies have shown convincing results using this method [54, 55].

Our risk signature was constructed with 30 IRGPs consisting of 28 IRGs. A high risk score independently predicted poor prognosis in BC patients. CD14 was among the 28 IRGs, and BC cells with high CD14 expression have been shown to produce tumor-promoting inflammation and promote tumor cell proliferation [56]. Joint blockade of complement C5a receptor 1 (C5AR1) and PD-1 prevented lung cancer metastasis and improved the prognosis of patients [57]. Overexpression of Dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1 (DKK1) has been shown to be related to poor OS in patients with BC [58]. An increased level of serum interleukin 18 (IL18) was found in patients with BC, which might be the result of the patients’ immune systems fighting to inhibit the growth of tumor cells [59]. Upregulated matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9) is closely related to the metastasis of BC [60, 61]. In another study, the knockdown of pentraxin 3 (PTX3) activated the proliferation of BC cells and enhanced the metabolism of tumor cells [62]. In this study, CIBERSORT was used to evaluate immune cell infiltration in the different risk groups. The levels of memory B cells, plasma cells, M1 macrophages, CD8 T cells, activated memory CD4 T cells and follicular helper T cells were higher in the low-risk group than in the high-risk group. The levels of M0 macrophages, M2 macrophages, eosinophils and resting memory CD4 T cells were higher in the high-risk group than in the low-risk group. Recent studies have indicated that high infiltration levels of CD8 T cells and CD4 T cells can exert anti-BC effects [63, 64]. High levels of M2 macrophages were significantly associated with poor prognosis in patients with BC, and metastasis of BC cells was inhibited by inducing M1 macrophage polarization [65]. In the low-risk group, the main effector immune cell infiltration level was increased, implying a stronger immune response, which may be the reason for the better prognosis of the low-risk group.

The level of TMB and the expression of immune checkpoints (PD-1, CTLA4 and LAG3) were both significantly negatively correlated with the risk score, suggesting that in the low-risk group, with the immune response enhanced, the expression of immune checkpoints was also increased, but fortunately, the immune response was activated more than suppressed, and the response to immunotherapy or ICIs could be more effective.

ESTIMATE was performed to analyze the association between the TME and the risk score. The TME, the cellular environment of tumor cells, is mainly composed of immune cells, stromal cells, extracellular matrix (ECM), small organelles and secreted proteins [66]. The results of our research demonstrated that the infiltration level of stromal cells was upregulated in the high-risk group, but there was no correlation between the immune score, tumor purity and risk score. Due to many different subtypes of immune cells, although some infiltrating immune cells in the high-risk group could not produce immune effects, they were clustered in both the high-risk group and the low-risk group via CIBERSORT analysis, and it was possible that there was no difference in the total immune score between the two groups. Additionally, low immune scores and the level of TMB were associated with poor OS in patients with BC. Therefore, we believe that immunotherapy is effective for patients with BC.

We did the same analysis with the GSE31684 dataset. Unfortunately, the results from the TCGA data were only partially observed in the results of the analysis of the GSE31684 dataset. There might be many reasons for this discrepancy. First, the changes in the TME and immune checkpoints were quite complicated. Second, the sample size of each BC data cohort in the GEO database was smaller than that in the cohorts in the TCGA database, and no mutation data were included. Third, the sequencing methods and data normalization used for each data cohort in the GEO database were not as advanced and rigorous as those used for the TCGA data cohorts. Given the deficiencies of the GEO data, the IMvigor210 dataset was also used for analysis, and we observed that more immune-related changes were found in the TCGA data than in the IMvigor210 data, but some results were still inconsistent. This discrepancy may be because the included samples were all advanced metastatic BC. Despite the limitations of the validated cohorts, we still found that many immune-related changes were consistent across the three cohorts (TCGA, GEO and IMvigor210), some immune cells (including M0 macrophages, M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages, activated memory CD4 T cells and resting memory CD4 T cells) showed the same changes. Moreover, TMB and some immune checkpoints also showed the same changes in the IMvigor210 data (there are no mutation data in GSE31684), suggesting that immunotherapy can achieve significant benefits in low-risk BC patients.

Finally, the molecular mechanisms underlying the risk score were explored via GSEA. The GO results showed that gene sets related to the ECM, stromal cells (chondrocytes, endothelial cells and fibroblasts) and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) were enriched in the high-risk group. Focal adhesion and ECM-receptor interaction, all connected with ECM, were the top two significant enrichment pathways in the high-risk group via KEGG. The enrichment of stromal cells in the high-risk group was consistent with the ESTIMATE results. However, we think it was valuable to discover that ECM, which constitutes scaffolds of tissues and organs, was enriched in the high-risk group [67]. The ECM is one of the most abundant components in the TME, and as the key to maintaining tissue homeostasis, the ECM is a dynamic environment, and ECM disorder can promote tumor occurrence, progression, and metastasis by inducing EMT [68–72]. The literature has shown that focal adhesion-related molecules, such as focal adhesion kinases (FAKs), play a vital role in EMT and upregulate the metastatic capacity of tumor cells in BC [73–75]. We also found that a high risk score was related to advanced M stage (metastasis). In the low-risk group, we found that there were a number of immune-related pathways in the enriched pathways and biofunctions via GO and KEGG, such as T cell receptor complex, immunoglobulin production, CD4-positive or CD8-positive alpha-beta T cell lineage commitment, primary immunodeficiency, intestinal immune network for IgA production and RIG I-like receptor signaling pathway, which might imply the activation of immune responses in the low-risk group.

However, the limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, our study was a retrospective analysis, and the results need to be verified by a prospective cohort study. Second, the specific mechanism of the immunological parameters changing with the risk score was not studied in depth. Third, our analysis of the biofunctions underlying the risk score was not verified by in vitro or in vivo experiments.

Although our research had some limitations, the IRGP risk signature that we constructed for BC could predict the prognosis of patients, and use of this signature will be helpful for individualized treatment decisions, clinical decision-making and evaluation of the benefits of immunotherapy. In addition, the relevant genes included in the risk signature could also be used for further research to identify new therapeutic targets for BC.

Conclusions

In this study, we used a new tool, IRGPs, to build a risk signature to predict the prognosis of BC. By evaluating immune parameters and molecular mechanisms, we gained further understanding of the mechanisms underlying the risk signature. The signature could also be used as a tool to predict the effect of immunotherapy in patients with BC.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Fig. 1. Subgroup analyses (GEO). Subgroup analyses were performed based on age (A-B), clinical stage (C-D) and T stage (E-F) to confirm the robustness of the risk signature. The median of age was 68.015. GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Fig. 2. Subgroup analyses (IMvigor210). Subgroup analyses were performed based on age (A-B) and subtype (C-D) to confirm the robustness of the risk signature.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Fig. 3. Immunological parameters and risk scores (GEO). The expression levels of BTLA (A) and CTLA4 (B) were significantly negatively correlated with the risk score. However, there was no significant correlation between the risk score and other immune checkpoints, including PD-1 (C), PD-L1 (D), LAG3 (E), and HAVCR2 (F). The immune score (G) was significantly negatively correlated with the risk score. There was no significant correlation between the stromal score (H), tumor purity (I) and risk score. GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; PD-1, programmed death-1; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4; LAG3, lymphocyte activating 3; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; BTLA, B and T lymphocyte associated; HAVCR2, hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2; BC, bladder cancer.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Fig. 4. Immunological parameters and risk scores (IMvigor210). The expression levels of PD-1 (A), BTLA (B), and CTLA4 (C) were significantly negatively correlated with the risk score. However, there was no significant correlation between the risk score and other immune checkpoints, including PD-L1 (D), LAG3 (E), and HAVCR2 (F). The stromal score (G) was significantly positively correlated with the risk score. The immune score (H) was significantly negatively correlated with the risk score. There was no significant correlation between tumor purity (I) and the risk score. PD-1, programmed death-1; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4; LAG3, lymphocyte activating 3; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; BTLA, B and T lymphocyte associated; HAVCR2, hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2; BC, bladder cancer.

Acknowledgements

We thank the TCGA and GEO for sharing large amounts of data.

Abbreviations

- BC

Bladder cancer

- NMIBC

Nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer

- MIBC

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer

- BCG

Bacillus Calmette-Guerin

- IL-2

Interleukin-2

- IRGPs

Immune-related gene pairs

- GSEA

Gene set enrichment analysis

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- TURBT

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor

- GMCSF

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- ICIs

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- PD-1

Programmed death-1

- PD-L1

Programmed death ligand-1

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4

- TMB

Tumor mutation burden

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- LASSO

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- IRGs

Immune-related genes

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- ImmPort

Immunology Database and Analysis Portal

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- OS

Overall survival

- CIBERSORT

Cell type identification by estimating relative subsets of RNA transcripts

- GEPs

Gene expression profiles

- LAG3

Lymphocyte activating 3

- BTLA

B and T lymphocyte associated

- HAVCR2

Hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2

- ESTIMATE

Estimation of Stromal and Immune cells in Malignant Tumor tissues using Expression data

- NESs

Normalized enrichment scores

- NOM P value

Nominal P value

- FDR Q value

False discovery rate Q value

- MSigDB

Molecular Signatures Database

- AUC

Area under the curve

- HR

Hazard ratio

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- C5AR1

C5a receptor 1

- DKK1

Dickkopf WNT signaling pathway inhibitor 1

- IL-18

Interleukin 18

- MMP9

Matrix metallopeptidase 9

- PTX3

Pentraxin 3

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- FAKs

Focal adhesion kinases

Authors’ contributions

YF, LY, CZK and JBB contributed to the design of the study. YF, LY and SSS performed the statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation and manuscript revisions and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Project of Liaoning Distinguished Professor [Grant No. 2012145], the Shenyang Plan Project of Science and Technology [Grant No. F17–230–9-08], China Medical University’s 2017 Discipline Promotion Program [Grant No. 3110117040], China Medical University’s 2018 Discipline Promotion Program, and the 2017 National Key R&D Program Key Projects of Precision Medical Research [No. 2017YFC0908000].

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the TCGA repository (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), GSE31684 repository, (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE31684), and IMvigor210 (http://research-pub.gene.com/IMvigor210CoreBiologies/).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chuize Kong, Email: kongchuize_cmu@sina.cn.

Lei Yin, Email: yinleicmu@163.com.

References

- 1.SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2016, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/based on November 2018 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site.

- 2.Nabavizadeh R, Bobrek K, Master VA. Risk stratification for bladder cancer: biomarkers of inflammation and immune activation. Urol Oncol. 2020;38(9):706–712. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li F, Guo H, Wang Y, Liu B, Zhou H. Profiles of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and prognostic genes associated with the microenvironment of bladder cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;85:106641. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rouanne M, Roumiguié M, Houédé N, Masson-Lecomte A, Colin P, Pignot G, Larré S, Xylinas E, Rouprêt M, Neuzillet Y. Development of immunotherapy in bladder cancer: present and future on targeting PD(L)1 and CTLA-4 pathways. World J Urol. 2018;36(11):1727–1740. doi: 10.1007/s00345-018-2332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts JT, Ricci S, Dogliotti L, Oliver T, Moore MJ, Zimmermann A, Arning M. Long-term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(21):4602–4608. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duan S, Wang P, Liu F, Huang H, An W, Pan S, Wang X. Novel immune-risk score of gastric cancer: a molecular prediction model combining the value of immune-risk status and chemosensitivity. Cancer Med. 2019;8(5):2675–2685. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angell H, Galon J. From the immune contexture to the Immunoscore: the role of prognostic and predictive immune markers in cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25(2):261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gentles AJ, Newman AM, Liu CL, Bratman SV, Feng W, Kim D, Nair VS, Xu Y, Khuong A, Hoang CD, Diehn M, West RB, Plevritis SK, Alizadeh AA. The prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across human cancers. Nat Med. 2015;21(8):938–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter BW, Halpenny DF, Ginsberg MS, Papadimitrakopoulou VA, de Groot PM. Immunotherapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment: Current Status and the Role of Imaging. Journal of thoracic imaging. 2017;32(5):300-12. 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000291. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Lin P, Guo YN, Shi L, Li XJ, Yang H, He Y, et al. Development of a prognostic index based on an immunogenomic landscape analysis of papillary thyroid cancer. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11(2):480-500. 10.18632/aging.101754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Arora S, Velichinskii R, Lesh RW, Ali U, Kubiak M, Bansal P, Borghaei H, Edelman MJ, Boumber Y. Existing and emerging biomarkers for immune checkpoint immunotherapy in solid tumors. Adv Ther. 2019;36(10):2638–2678. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01051-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kresowik TP, Griffith TS. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Immunotherapy. 2009;1(2):281–288. doi: 10.2217/1750743X.1.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pettenati C, Ingersoll MA. Mechanisms of BCG immunotherapy and its outlook for bladder cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2018;15(10):615–625. doi: 10.1038/s41585-018-0055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinberg RL, Nepple KG, Velaer KN, Thomas LJ, O'Donnell MA. Quadruple immunotherapy of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, interferon, interleukin-2, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor as salvage therapy for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 2017;35(12):670.e677–670.e614. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Böhle A, Jocham D, Bock PR. Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin versus mitomycin C for superficial bladder cancer: a formal meta-analysis of comparative studies on recurrence and toxicity. J Urol. 2003;169(1):90–95. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamm DL, van der Meijden PM, Morales A, Brosman SA, Catalona WJ, Herr HW, Soloway MS, Steg A, Debruyne FM. Incidence and treatment of complications of bacillus Calmette-Guerin intravesical therapy in superficial bladder cancer. J Urol. 1992;147(3):596–600. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)37316-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roufas C, Chasiotis D, Makris A, Efstathiades C, Dimopoulos C, Zaravinos A. The expression and prognostic impact of immune cytolytic activity-related markers in human malignancies: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2018;8:27. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gust KM, Rebhan K, Resch I, Shariat SF, Necchi A. Immune checkpoint inhibition in muscle-invasive and locally advanced bladder cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2020;30(4):547–556. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang C, Li Z, Qi F, Hu X, Luo J. Exploration of the relationships between tumor mutation burden with immune infiltrates in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(22):648. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.10.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forschner A, Battke F, Hadaschik D, Schulze M, Weißgraeber S, Han CT, Kopp M, Frick M, Klumpp B, Tietze N, Amaral T, Martus P, Sinnberg T, Eigentler T, Keim U, Garbe C, Döcker D, Biskup S. Tumor mutation burden and circulating tumor DNA in combined CTLA-4 and PD-1 antibody therapy in metastatic melanoma - results of a prospective biomarker study. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):180. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0659-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang F, Wei XL, Wang FH, Xu N, Shen L, Dai GH, Yuan XL, Chen Y, Yang SJ, Shi JH, Hu XC, Lin XY, Zhang QY, Feng JF, Ba Y, Liu YP, Li W, Shu YQ, Jiang Y, Li Q, Wang JW, Wu H, Feng H, Yao S, Xu RH. Safety, efficacy and tumor mutational burden as a biomarker of overall survival benefit in chemo-refractory gastric cancer treated with toripalimab, a PD-1 antibody in phase Ib/II clinical trial NCT02915432. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(9):1479–1486. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodman AM, Kato S, Bazhenova L, Patel SP, Frampton GM, Miller V, Stephens PJ, Daniels GA, Kurzrock R. Tumor mutational burden as an independent predictor of response to immunotherapy in diverse cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16(11):2598–2608. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhattacharya S, Andorf S, Gomes L, Dunn P, Schaefer H, Pontius J, et al. ImmPort: disseminating data to the public for the future of immunology. Immunologic research. 2014;58(2-3):234-9. 10.1007/s12026-014-8516-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Kang K, Xie F, Mao J, Bai Y, Wang X. Significance of tumor mutation burden in immune infiltration and prognosis in cutaneous melanoma. Front Oncol. 2020;10:573141. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.573141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun XY, Yu SZ, Zhang HP, Li J, Guo WZ, Zhang SJ. A signature of 33 immune-related gene pairs predicts clinical outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2020;9(8):2868–2878. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo J, Liu P, Wang L, Huang Y, Wang Y, Geng W, Chen D, Bai Y, Yang Z. Establishment of an immune-related gene pair model to predict colon adenocarcinoma prognosis. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):1071. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07532-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qiu H, Hu X, He C, Yu B, Li Y, Li J. Identification and validation of an individualized prognostic signature of bladder cancer based on seven immune related genes. Front Genet. 2020;11:12. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu J, Wang H, Ma T, He Y, Shen M, Song W, Wang JJ, Shi JP, Wu MY, Liu C, Wang WJ, Huang YQ. Identification of immune-related genes as prognostic factors in bladder cancer. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):19695. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76688-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Shen C, Dong D, Zhong X, Wang Y, Yang X. Identification and verification of an immune-related lncRNA signature for predicting the prognosis of patients with bladder cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;90:107146. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xing Q, Liu S, Jiang S, Li T, Wang Z, Wang Y. Prognostic model of 10 immune-related genes and identification of small molecule drugs in bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA) Transl Androl Urol. 2020;9(5):2054–2070. doi: 10.21037/tau-20-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Y, Zhang L, He S, Guan B, He A, Yang K, Gong Y, Li X, Zhou L. Identification of immune-related LncRNA for predicting prognosis and immunotherapeutic response in bladder cancer. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12(22):23306–23325. doi: 10.18632/aging.104115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng Y, Hong X, Yu C, Li H, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Wang T, Wang X. Preclinical analysis of novel prognostic transcription factors and immune-related gene signatures for bladder cancer via TCGA-based bioinformatic analysis. Oncol Lett. 2021;21(5):344. doi: 10.3892/ol.2021.12605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M, Alizadeh AA. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 2015;12(5):453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye L, Zhang T, Kang Z, Guo G, Sun Y, Lin K, Huang Q, Shi X, Ni Z, Ding N, Zhao KN, Chang W, Wang J, Lin F, Xue X. Tumor-infiltrating immune cells act as a marker for prognosis in colorectal cancer. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2368. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L, Zhu P, Tong Y, Wang Y, Ma H, Xia X, Zhou Y, Zhang X, Gao F, Shu P. An immune-related gene pairs signature predicts overall survival in serous ovarian carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:7005–7014. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S200191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martinez E, Vegesna R, Kim H, Torres-Garcia W, Trevino V, Shen H, Laird PW, Levine DA, et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun. 2013;4(1):2612. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li B, Geng R, Wu Q, Yang Q, Sun S, Zhu S, Xu Z, Sun S. Alterations in immune-related genes as potential marker of prognosis in breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:333. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alfred Witjes J, Lebret T, Compérat EM, Cowan NC, De Santis M, Bruins HM, Hernández V, Espinós EL, Dunn J, Rouanne M, et al. Updated 2016 EAU guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;71(3):462–475. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wołącewicz M, Hrynkiewicz R, Grywalska E, Suchojad T, Leksowski T, Roliński J, Niedźwiedzka-Rystwej P. Immunotherapy in bladder cancer: current methods and future perspectives. Cancers. 2020;12(5):1181. doi: 10.3390/cancers12051181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herr HW, Morales A. History of bacillus Calmette-Guerin and bladder cancer: an immunotherapy success story. J Urol. 2008;179(1):53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seidl C. Targets for therapy of bladder cancer. Semin Nucl Med. 2020;50(2):162–170. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2020.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bellmunt J, Powles T, Vogelzang NJ. A review on the evolution of PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy for bladder cancer: the future is now. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;54:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katz H, Wassie E, Alsharedi M. Checkpoint inhibitors: the new treatment paradigm for urothelial bladder cancer. Med Oncol. 2017;34(10):170. doi: 10.1007/s12032-017-1029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cunha LL, Marcello MA, Rocha-Santos V, Ward LS. Immunotherapy against endocrine malignancies: immune checkpoint inhibitors lead the way. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2017;24(12):T261-81. 10.1530/ERC-17-0222. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Popovic A, Jaffee EM, Zaidi N. Emerging strategies for combination checkpoint modulators in cancer immunotherapy. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2018;128(8):3209-18. 10.1172/jci120775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Kobold S, Pantelyushin S, Rataj F, Vom Berg J. Rationale for Combining Bispecific T Cell Activating Antibodies With Checkpoint Blockade for Cancer Therapy. Front Oncol 2018;8:285-93. 10.3389/fonc.2018.00285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Alhalabi O, Rafei H, Shah A, Siefker-Radtke A, Campbell M, Gao J. Targeting advanced urothelial carcinoma-developing strategies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2019;31(3):207–215. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Massard C, Gordon MS, Sharma S, Rafii S, Wainberg ZA, Luke J, Curiel TJ, Colon-Otero G, Hamid O, Sanborn RE, O’Donnell PH, Drakaki A, Tan W, Kurland JF, Rebelatto MC, Jin X, Blake-Haskins JA, Gupta A, Segal NH. Safety and efficacy of durvalumab (MEDI4736), an anti-programmed cell death Ligand-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, in patients with advanced urothelial bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(26):3119–3125. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.9761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li B, Cui Y, Diehn M, Li R. Development and validation of an individualized immune prognostic signature in early-stage nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(11):1529–1537. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ouyang W, Ren L, Liu G, Chi X, Wei H. LncRNA MIR4435-2HG predicts poor prognosis in patients with colorectal cancer. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6683. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leek JT, Scharpf RB, Bravo HC, Simcha D, Langmead B, Johnson WE, Geman D, Baggerly K, Irizarry RA. Tackling the widespread and critical impact of batch effects in high-throughput data. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(10):733–739. doi: 10.1038/nrg2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eddy JA, Sung J, Geman D, Price ND. Relative expression analysis for molecular cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2010;9(2):149–159. doi: 10.1177/153303461000900204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Popovici V, Budinska E, Tejpar S, Weinrich S, Estrella H, Hodgson G, Van Cutsem E, Xie T, Bosman FT, Roth AD, et al. Identification of a poor-prognosis BRAF-mutant-like population of patients with colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(12):1288–1295. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peng PL, Zhou XY, Yi GD, Chen PF, Wang F, Dong WG. Identification of a novel gene pairs signature in the prognosis of gastric cancer. Cancer Med. 2018;7(2):344–350. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheah MT, Chen JY, Sahoo D, Contreras-Trujillo H, Volkmer AK, Scheeren FA, Volkmer JP, Weissman IL. CD14-expressing cancer cells establish the inflammatory and proliferative tumor microenvironment in bladder cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(15):4725–4730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424795112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ajona D, Ortiz-Espinosa S, Moreno H, Lozano T, Pajares MJ, Agorreta J, Bértolo C, Lasarte JJ, Vicent S, Hoehlig K, Vater A, Lecanda F, Montuenga LM, Pio R. A combined PD-1/C5a blockade synergistically protects against lung cancer growth and metastasis. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(7):694–703. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wei R, Rodrìguez RA, Mullor M, Tan Z, Gui Y, Hu J, Zhu T, Huang X, Zhu Y, Xu J. Analyzing the prognostic value of DKK1 expression in human cancers based on bioinformatics. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(8):552. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bukan N, Sözen S, Coskun U, Sancak B, Günel N, Bozkirli I, Senocak C. Serum interleukin-18 and nitric oxide activity in bladder carcinoma. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2003;14(3):163–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qin Z, Wang Y, Tang J, Zhang L, Li R, Xue J, Han P, Wang W, Qin C, Xing Q, et al. High LINC01605 expression predicts poor prognosis and promotes tumor progression via up-regulation of MMP9 in bladder cancer. Biosci Rep. 2018;38(5):BSR20180562. doi: 10.1042/BSR20180562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 61.Liu F, Zhang H, Xie F, Tao D, Xiao X, Huang C, Wang M, Gu C, Zhang X, Jiang G. Hsa_circ_0001361 promotes bladder cancer invasion and metastasis through miR-491-5p/MMP9 axis. Oncogene. 2020;39(8):1696–1709. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-1092-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matarazzo S, Melocchi L, Rezzola S, Grillo E, Maccarinelli F, Giacomini A, Turati M, Taranto S, Zammataro L, Cerasuolo M, et al. Long pentraxin-3 follows and modulates bladder cancer progression. Cancers. 2019;11(9):1277. doi: 10.3390/cancers11091277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oh DY, Kwek SS, Raju SS, Li T, McCarthy E, Chow E, Aran D, Ilano A, Pai CS, Rancan C, et al. Intratumoral CD4(+) T cells mediate anti-tumor cytotoxicity in human bladder cancer. Cell. 2020;181(7):1612–1625.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hartana CA, Ahlén Bergman E, Zirakzadeh AA, Krantz D, Winerdal ME, Winerdal M, Johansson M, Alamdari F, Jakubczyk T, Glise H, Riklund K, Sherif A, Winqvist O. Urothelial bladder cancer may suppress perforin expression in CD8+ T cells by an ICAM-1/TGFβ2 mediated pathway. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0200079. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu J, Duan X. PA-MSHA induces apoptosis and suppresses metastasis by tumor associated macrophages in bladder cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2017;17(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s12935-017-0445-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li P, Cao J, Li J, Yao Z, Han D, Ying L, Wang Z, Tian J. Identification of prognostic biomarkers associated with stromal cell infiltration in muscle-invasive bladder cancer by bioinformatics analyses. Cancer Med. 2020;9(19):7253–7267. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eble JA, Niland S. The extracellular matrix in tumor progression and metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2019;36(3):171–198. doi: 10.1007/s10585-019-09966-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Luo Y, Zeng G, Wu S. Identification of microenvironment-related prognostic genes in bladder cancer based on gene expression profile. Front Genet. 2019;10:1187. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.01187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shintani Y, Hollingsworth MA, Wheelock MJ, Johnson KR. Collagen I promotes metastasis in pancreatic cancer by activating c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase 1 and up-regulating N-cadherin expression. Cancer Res. 2006;66(24):11745–11753. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Torzilli PA, Bourne JW, Cigler T, Vincent CT. A new paradigm for mechanobiological mechanisms in tumor metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22(5–6):385–395. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19(11):1423–1437. doi: 10.1038/nm.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hynes RO. The extracellular matrix: not just pretty fibrils. Science. 2009;326(5957):1216–1219. doi: 10.1126/science.1176009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li D, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Zhan C, Li X, Ba T, Qiu Z, E F. Lv G, Zou C, et al. CADM2, as a new target of miR-10b, promotes tumor metastasis through FAK/AKT pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0699-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang TY, Wu ML, Chang CI, Liu CI, Cheng TC, Wu YJ. Bornyl cis-4-hydroxycinnamate suppresses cell metastasis of melanoma through FAK/PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways and inhibition of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(8):2152. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kong DB, Chen F, Sima N. Focal adhesion kinases crucially regulate TGFβ-induced migration and invasion of bladder cancer cells via Src kinase and E-cadherin. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:1783–1792. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S122463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Fig. 1. Subgroup analyses (GEO). Subgroup analyses were performed based on age (A-B), clinical stage (C-D) and T stage (E-F) to confirm the robustness of the risk signature. The median of age was 68.015. GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Fig. 2. Subgroup analyses (IMvigor210). Subgroup analyses were performed based on age (A-B) and subtype (C-D) to confirm the robustness of the risk signature.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Fig. 3. Immunological parameters and risk scores (GEO). The expression levels of BTLA (A) and CTLA4 (B) were significantly negatively correlated with the risk score. However, there was no significant correlation between the risk score and other immune checkpoints, including PD-1 (C), PD-L1 (D), LAG3 (E), and HAVCR2 (F). The immune score (G) was significantly negatively correlated with the risk score. There was no significant correlation between the stromal score (H), tumor purity (I) and risk score. GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; PD-1, programmed death-1; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4; LAG3, lymphocyte activating 3; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; BTLA, B and T lymphocyte associated; HAVCR2, hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2; BC, bladder cancer.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Fig. 4. Immunological parameters and risk scores (IMvigor210). The expression levels of PD-1 (A), BTLA (B), and CTLA4 (C) were significantly negatively correlated with the risk score. However, there was no significant correlation between the risk score and other immune checkpoints, including PD-L1 (D), LAG3 (E), and HAVCR2 (F). The stromal score (G) was significantly positively correlated with the risk score. The immune score (H) was significantly negatively correlated with the risk score. There was no significant correlation between tumor purity (I) and the risk score. PD-1, programmed death-1; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4; LAG3, lymphocyte activating 3; PD-L1, programmed death ligand-1; BTLA, B and T lymphocyte associated; HAVCR2, hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 2; BC, bladder cancer.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the TCGA repository (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), GSE31684 repository, (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE31684), and IMvigor210 (http://research-pub.gene.com/IMvigor210CoreBiologies/).