Abstract

Fusobacterium nucleatum may be implicated in cases of emphysematous cholecystitis (EC) and carries a high mortality risk, especially in individuals with heart disease, renal insufficiency, and underlying malignancy. Fusobacterium infections are rarely detected in the setting of cholecystitis possibly due to the difficulty with properly culturing the bacteria. We describe a case of a patient with EC in whom blood cultures were positive for growth of F. nucleatum in one of two samples. The patient was treated with empiric antibiotic therapy consisting of metronidazole and cefepime. In patients with EC and negative cultures, it is possible that they may have an undetected infection with fusobacteria, which carries a high mortality risk. As such, clinicians should maintain a high degree of suspicion of obligate anaerobic infection in patients who have negative blood culture for growth in the setting of EC and consider continuation of adequate antimicrobial coverage.

Keywords: emphysematous cholecystitis, fusobacterium nucleatum emphysematous cholecystitis, culture negative, anaerobic, fusobacterium nucelatum

Introduction

Emphysematous cholecystitis (EC) is an acute variant of cholecystitis, characterized by air in the gallbladder lumen, wall, or surrounding tissues without an abnormal communication with the gastrointestinal tract [1]. Acute cholecystitis is associated with inflammation of the gallbladder, with at least 90% of cases arising from cholelithiasis. The rare emphysematous variant is associated with less than 3% of cholecystitis cases with a mortality rate of 15%-20% in comparison to the 1.4% mortality in patients with cholecystitis. It should be noted that patients with EC may also have concurrent gallstones [2,3]. The underlying etiology is thought to be infection resulting in gangrene and subsequent necrosis of the gallbladder. EC is most commonly seen in males over 50 years old. Other associated medical conditions include cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and neoplasms [4].

Patients usually present with right upper quadrant pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, and occasionally positive Murphy’s sign [5,6]. Ultrasound (US) is the best initial imaging modality for detection, although the ability to visualize EC varies based on the amount of air in the gallbladder. The most sensitive imaging technique is CT. Diagnosis of EC is based on the clinical presentation and imaging [5,7]. EC is approached as a life-threatening condition, so patients should be administered antibiotics and undergo a cholecystectomy as soon as possible.

Secondary bacterial infections in acute cholecystitis are commonly due to the enteric organisms Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Streptococcus faecalis, and Enterococci [8,9]. Clostridium perfringens is uniquely seen in patients with EC [10].

Our patient was found to have bacteremia secondary to Fusobacterium nucleatum in the setting of EC. Fusobacteria are obligate anaerobic bacteria commonly found in the oropharyngeal and gastrointestinal tracts [11,12]. Infection is usually associated with colorectal carcinoma and immunocompromised individuals [13]. Fusobacteria are usually sensitive, with low rates of resistance, to penicillins, metronidazole, and clindamycin [12,14].

Case presentation

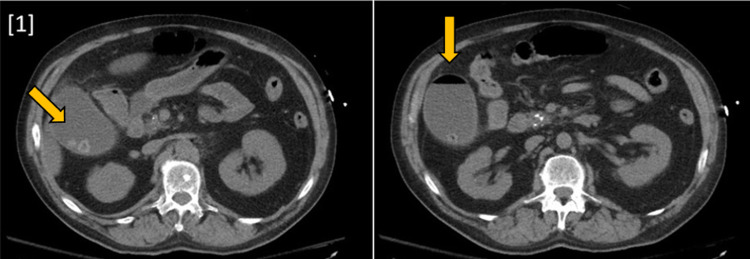

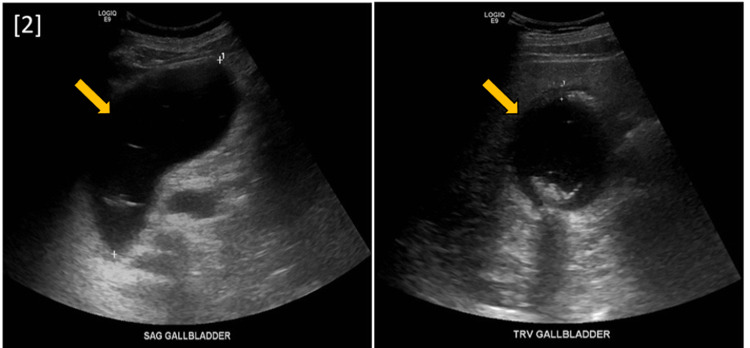

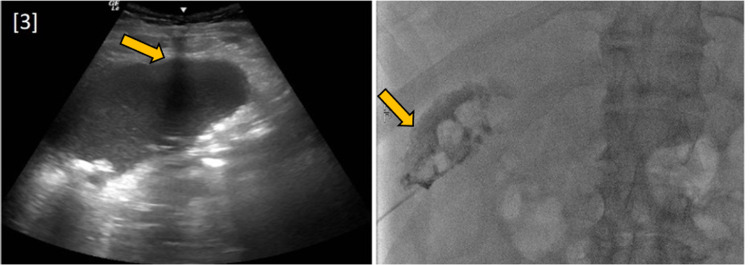

A 63-year-old male with a history of extensive alcohol and drug use, pancreatitis, hypertension, and gout was brought to the emergency department by emergency medical services due to a few days of stupor. Physical examination was significant for blood pressure of 167/87 and pain in the right upper quadrant. Labs demonstrated anion gap metabolic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, hyponatremia, elevated liver enzymes, and acute kidney injury with severe uremia. Non-contrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed a distended gallbladder with an air-fluid level, confirming the diagnosis of EC (Figure 1). These findings were consistent with those found in the initial US (Figure 2). The patient received an emergency percutaneous cholecystostomy tube (Figure 3) and was started on empiric antibiotic therapy consisting of metronidazole and cefepime. Later in the course of admission, one of two blood cultures was positive for growth of F. nucleatum.

Figure 1. CT abdomen and pelvis without contrast showing a distended gallbladder with air-fluid collection and multiple stones as well as a peri-cholecystic fluid reaction.

Figure 2. Right upper quadrant ultrasound (sagittal and transverse sections) showing moderately distended gallbladder with sludge and stones. Additionally, air present in the fundus is highly suggestive of emphysematous cholecystitis.

Figure 3. Fluoroscopic image-guided percutaneous cholecystostomy tube placement.

Discussion

The prevalence of Fusobacterium in cholecystitis is likely underestimated due to the low incidence of positive blood cultures and the methods of obtaining fluid samples. Fusobacterium nucleatum is a known cause of odontogenic infections, pleural empyemas, and brain abscesses [15]. Fusobacterium nucleatum infections can also precipitate Lemierre Syndrome, a thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein [16]. However, Fusobacterium bacteremia is an uncommon infection, which accounts for approximately 0.9% of patients with bacteremia and carries an overall mortality rate of 40.7% even when patients receive appropriate antibiotic treatment. Heart failure, renal insufficiency, and malignancy are independent risk factors for mortality [17]. The low prevalence of Fusobacterium blood cultures is partially due to the fact that the organism is an obligate anaerobe. One study showed that appendicitis caused by anaerobic organisms only resulted in a positive blood culture 50% of the time [18].

Another source of low prevalence of EC secondary to Fusobacterium may be the method through which culture specimens are obtained. The specimens must be obtained and transported in an anaerobic environment. There are multiple documented cases of patients infected with F. nucleatum in which specimen cultures were negative for growth. In these cases, the infection was only detected when 16S rRNA gene polymerase chain reaction of the sample was utilized [19].

Cholecystostomy tubes are an easy way to access fluid from the gallbladder, especially in patients who are not candidates for cholecystectomy. However, the tube exposes the fluid to air, which can kill obligate anaerobic bacteria. Directly collecting sample fluid in an anaerobic environment from the gallbladder may be more likely to grow the bacteria responsible for EC. Identification of Fusobacterium may not alter management in the setting of acute cholecystitis as it is sensitive to current recommended antibiotic therapy [20]. However, clinicians should have suspicion for anaerobic etiology for EC in the setting of negative fluid and blood cultures, and continuation of antibiotic treatment should be considered to cover for Fusobacterium and other obligate anaerobic microorganisms that may be difficult to culture.

Conclusions

Fusobacteria may be implicated in cases of EC. Bacteremia with this organism carries a high mortality risk, especially in individuals with heart disease, renal insufficiency, and underlying malignancy. Fusobacterium infections are rarely detected in the setting of cholecystitis and this may be due to the difficulty culturing the bacteria with current techniques. Despite negative cultures, patients with EC may have infection with fusobacteria, which carries a high mortality risk. As such, clinicians should maintain a high degree of suspicion of obligate anaerobic infection in patients who have negative blood culture for growth in the setting of EC and consider continuation of adequate antimicrobial coverage.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.A comparative appraisal of emphysematous cholecystitis. Mentzer RM, Jr. Jr., Golden GT, Chandler JG, Horsley JS, 3rd 3rd. Am J Surg. 1975;129:10–15. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(75)90159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kowalski A, Kashyap S, Mathew G, Pfeifer C. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Clostridial Cholecystitis. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perforated emphysematous cholecystitis and Streptococcus bovis. Mora-Guzmán I, Martín-Pérez E. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2019;111:166–167. doi: 10.17235/reed.2018.5826/2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clinical practice. Acute calculous cholecystitis. Strasberg SM. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2804–2811. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0800929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emphysematous cholecystitis: a deadly twist to a common disease. Safwan M, Penny SM. J Diagn Med Sonogr. 2016;32:131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emphysematous cholecystitis. Mhamdi S, Mhamdi K. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:0. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1814551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Point-of-care ultrasound diagnosis of emphysematous cholecystitis. Al Hammadi F, Buhumaid R. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2020;4:107–108. doi: 10.5811/cpcem.2019.11.45337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acute cholecystitis. Indar AA, Beckingham IJ. BMJ. 2002;325:639–643. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7365.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cross-sectional imaging of acute and chronic gallbladder inflammatory disease. Smith EA, Dillman JR, Elsayes KM, Menias CO, Bude RO. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:188–196. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emphysematous cholecystitis. Yen WL, Hsu CF, Tsai MJ. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2016;28:37–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tcmj.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fusobacterium nucleatum infections: clinical spectrum and bacteriological features of 78 cases. Denes E, Barraud O. Infection. 2016;44:475–481. doi: 10.1007/s15010-015-0871-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Implication of Fusobacterium necrophorum in recurrence of peritonsillar abscess. Ali SA, Kovatch KJ, Smith J, Bellile EL, Hanks JE, Hoff PT. Laryngoscope. 2019;129:1567–1571. doi: 10.1002/lary.27675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The link between Fusobacteria and colon cancer: a fulminant example and review of the evidence. King M, Hurley H, Davidson KR, Dempsey EC, Barron MA, Chan ED, Frey A. Immune Netw. 2020;20:0. doi: 10.4110/in.2020.20.e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre's syndrome. Riordan T. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:622–659. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00011-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bacteria and fungi in acute cholecystitis. A prospective study comparing next generation sequencing to culture. Dyrhovden R, Øvrebø KK, Nordahl MV, Nygaard RM, Ulvestad E, Kommedal Ø. J Infect. 2020;80:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2019.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemierre's syndrome due to Fusobacterium necrophorum. Kuppalli K, Livorsi D, Talati NJ, Osborn M. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:808–815. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fusobacterium bacteremia: clinical significance and outcomes. Su CP, Huang PY, Yang CC, Lee MH. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19949758/ J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2009;42:336–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Recovery of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria from patients with acute appendicitis using blood culture bottles. Jiménez A, Sánchez A, Rey A, Fajardo C. Biomedica. 2019;39:699–706. doi: 10.7705/biomedica.4774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Detection of Fusobacterium nucleatum in culture-negative brain abscess by broad-spectrum bacterial 16S rRNA gene PCR. Chakvetadze C, Purcarea A, Pitsch A, Chelly J, Diamantis S. IDCases. 2017;8:94–95. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, et al. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:3–16. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]