Abstract

Behavior change communication (BCC) aids in the prevention of both communicable and noncommunicable diseases in clinical settings and public health. Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases in the future need to be tackled by developing behavioral immunity through effective BCC strategies. Health education and Information Education and Communication gradually evolved to BCC primarily focusing on creating a conducive environment for promoting behavior change. Various theories/models operating at the individual, inter-personal, and community levels were put forward to explain the core constructs of behavior change. Each theory/model has its own strengths and weaknesses in its applicability. In practice, no theory is perfect and each has certain limitations. Hence, a battery of theories may be needed to develop a BCC strategy. This review article critically appraises the evolution of BCC, the strengths and weaknesses of BCC theories/models and it's applicability from the past to the future. This review will benefit postgraduates and public health workers in understanding the concepts of BCC and applying the same in their practice.

Keywords: Behavior change, COVID 19, emerging, models, theories

INTRODUCTION

Behavior change communication (BCC) plays a key role in clinical settings and public health in the prevention of both communicable and noncommunicable diseases. In the future, it aids in tackling the outbreaks from the emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. BCC is “an interactive process with communities (as integrated with an overall program) to develop tailored messages and approaches using a variety of communication channels to develop positive behaviours; promote and sustain individual, community and societal behavior change; and maintain appropriate behaviours (pp: 3).”[1] BCC which gradually evolved over years emphasizing primarily on providing a conducive environment has certain theories/models for explaining its core constructs. These theories/models are applied at various levels and have unique strengths and weaknesses in their applicability. A BCC strategy in any program should have a theoretical base for effective planning and evaluating an intervention. This review article critically appraises the evolution of BCC, the strengths and weaknesses of BCC theories/models and its applicability from the past to the future. This review will benefit postgraduates and public health workers in understanding the concepts of BCC and applying the same in their practice.

EVOLUTION OF TERM “BEHAVIOR CHANGE COMMUNICATION”

In 1792, the concept of health education (HE) was developed and it was extensively used in 1980s as a cost-effective intervention for disseminating information for the prevention of diseases.[2] John M. Last defines HE as “the process by which individuals and groups of people learn to behave in a manner conducive to the promotion, maintenance or restoration of health (pp: 920).”[3] It assumes that knowledge determines attitudes and attitudes in turn influences the behavior.[3] Education alone is not sufficient to initiate a behavior change because the target population requires access to proven preventive measures.[3] For example, educating antenatal women about maternal anemia will not lead to increased intake of iron rich foods unless they have access to it.

In order to plug the existing gaps in HE, Information Education and Communication (IEC) came into practice in the early 1990s.[4] IEC as stated by the World Health Organization “is an approach which attempts to change or reinforce a set of behaviours in a target audience regarding a specific problem in a predefined period of time (pp: 3).”[4] IEC activities were concerned with carrying out research on audiences to determine an effective way of delivering the appropriate information.[5] It caters to the different needs of the people through various communication tools such as posters, brochures, radio broadcasts, and TV spots.[5] It takes for granted that creating awareness will automatically leads to action and is made with the assumption that one size fits all.[4]

IEC gradually evolved to BCC and it is a part of BCC. IEC is substantially concerned with awareness generation while BCC goes one-step forward and its action-oriented.[5] BCC is based on an analog which symbolizes emotional side as the elephant, rational/analytical side as the rider and environment as the path.[6] In that analog, it is stated that in order to make the elephant and the rider stay on the course, it is necessary to shorten the distance and remove the obstacles along the path.[6] Thus, BCC is primarily concerned with creating a conducive environment which will enable people to change their behavior from the negative to the positive side.

EXPLORING THE THEORIES/MODELS OF BEHAVIOUR CHANGE COMMUNICATION ALONG WITH ITS STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES

BCC has various well-established theories/models that operate at the individual, inter-personal, and community levels. A theory is “a statement of concepts and their inter-relationships that shows and/or why a phenomenon occurs (pp: 232).”[7] While, a model is “a tool used to facilitate theory construction, typically a written or a graphic representation of a theory or one of its components (pp: 232).”[7] A model would be useful for visualizing how the core constructs of the theory interact to affect a behavior, but a model alone is not sufficient to provide an explanation. It is a dire need to know about a theory because it acts as a tool in identifying a problem and finding a way for changing the situation.[7] Theories which explain individual behaviors are Health Belief Model (HBM), theory of planned behavior (TPB), and transtheoretical model (TTM) while theories which explain group behaviors are social comparison theory, social impact theory, and social cognitive theory.[8,9]

THEORIES/MODELS APPLIED FOR BEHAVIOR CHANGE COMMUNICATION AT THE INDIVIDUAL LEVEL

In 1950s, in order to understand the people's behavior of rejecting free tuberculosis screening tests, HBM was developed by the social scientists at the US Public Health Services.[10] This theory mainly focuses on the individual's perception of the threat of a particular health problem and the appraisal of the recommended behaviors for solving that problem.[10] Consider an example of resorting to breast cancer screening by an elderly woman. Screening is influenced by that woman's perception about the risks/severity of contracting a breast cancer. Woman's perception about the benefits/barriers in performing a screening also affects the uptake of screening. Events that motivate that woman and her self-efficacy also act as positive vibes in performing a screening.

The usefulness of HBM as a whole is not tested and only the selected components of the model have been studied.[11] It does not take into account the environmental and the economic factors that influence the behaviors.[10] Social norms and peer influences which has a significant effect on behavior change is merely neglected.[11] For instance, smoking in adolescents mainly relies on the social influences and peer pressure. HBM is more descriptive in nature and does not suggest a strategy for action.[10]

The social norms and peer influences which were neglected in HBM were addressed in the TPB. Fisbhein added a construct of Perceived Behavioural Control in the Theory of Reasoned Action and converted it into TPB in 1994.[12] It states that individual's behavioral intention is the most important determinant of a behavior and is based on the principle that people weigh the merits and demerits before practicing a new behavior.[12] For Example, the behavioral intention to test for Chlamydia, a sexually transmitted disease is influenced by attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Here, attitude is the individual's positive/negative feelings toward the test. Subjective norms constitute the individual's beliefs regarding other people's opinion about Chlamydia testing. Perceived behavioral control is the individual's perceptions about the ease/difficulty in performing the test.

Like HBM, this theory also ignores the components of environmental and economic factors.[11] It believes that attitude change will simultaneously lead to a behavior change.[12] In real life situations, individuals first change their behavior and then gradually change their attitudes. For instance, helmet usage laws in India made the people to gradually change their negative attitude about the helmets as they got accustomed to the new behavior. Fear, mood, past experiences, and motivation are not given due importance.[11] As behaviors can change over time, assuming that behavior is the result of a linear decision-making process is a major flaw.[12]

The cyclical nature of change process in stages which were ignored in the previous two individualistic theories had been given due importance in TTM. Prochaska and Diclemente in 1970s, developed TTM/stages of change theory to compare smokers in therapy and self-changers along a behavior change continuum.[13] TTM operates on the assumption that people do not change behaviors quickly and decisively but change occurs continuously through a cyclical process.[13,14] The process of change is proposed in six stages.[13,14] Consider an example of smoking cessation where a smoker travels in stages from pre-contemplation to relapse/termination in a cyclical manner. In precontemplation, a smoker is unaware of the harmful effects of smoking and has no intention in quitting. In contemplation, he is aware of the harmful effects of smoking and the benefits of quitting. In preparation, he intends to quit smoking within the next 1 month. In action, he stopped smoking for < 6 months and in maintenance, he stopped smoking for more than 6 months. In relapse, he smokes again and in termination, he has no desire to smoke again.

As a psychological theory at the individual level, TTM does not focus on the structural and the environmental issues.[11] The relationship between each stages is not clearly stated.[12] Each of the stages may not be suitable for characterizing every population. A study on condom usage among sex workers in Bolivia discovered that few participants were in the pre-contemplation stage and few were in the contemplation stage.[11] The time element for each stage is not mentioned, i.e., how much time is needed for each stage or how long a person can remain in a particular stage.[13]

THEORIES/MODELS APPLIED FOR BEHAVIOR CHANGE COMMUNICATION AT THE INTER-PERSONAL LEVEL

The environmental factors which were overlooked in most of the individualistic theories were addressed in the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) by Albert Bandura. It operates at the inter-personal level and focuses on the psycho-social aspects.[8] Social Learning Theory evolved into SCT in 1986 by the addition of the construct of self-efficacy.[15] According to this theory, there is a dynamic reciprocal interaction between the personal/cognitive factors, the environmental influences and the behavior.[15] This theory proposes that behavior is not only driven by self but also by external forces.[11] Let us take for example, while performing an exercise for weight loss, certain factors such as environment, behavioral capability (knowledge/skill), self-control, observational learning (role models), reinforcements (incentives), and emotional coping responses (stress management) will also influence the behavior.

SCT fails to explain the extent to which each factor influences the behavior.[15] It does not take into account the past experiences and expectations.[11] It also ignores the biological difference between the individual and the genetic factors.[11] Applicability of all the constructs of SCT may be difficult in developing a focused public health program.[15]

THEORIES/MODELS APPLIED FOR BEHAVIOR CHANGE COMMUNICATION AT THE GROUP OR COMMUNITY LEVEL

Unlike the above-mentioned theories, Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) theory developed by E. M Rogers in 1962 is applied at the community level focusing on the socio-cultural aspects.[8] Initially, it originated in communication fields to explain how, over time, an idea/product gains momentum and diffuses through a specific population.[16] DOI theory aids in accelerating the adoption of public health programs.[12] Take for example, in rural areas everyone will not use toilets abruptly but it takes time to diffuse within a social system. There are five adopter categories in DOI theory.[17] To begin with, innovators are the first to use a toilet and early adopters represent opinion leaders and are comfortable using a toilet. Early majority need to see the evidence before using a toilet and late majority will use it after being tried by a majority. Finally, laggards are the hardest group to change as they are very conservative and bound by tradition. The efficiency of a new idea and it is consistency with the values, experiences, and needs of the people are the key factors which facilitates the diffusion of an innovation.[17]

In DOI theory, it is arduous to measure what exactly causes the adoption of an innovation.[11] Another weakness is the one-way flow of information from the sender to the receiver.[16] Resources and social support to adopt a new behavior is not highlighted.[17] It cannot be applied in cessation/prevention programs.[16] Participatory approach for the adoption of a new behavior is not mentioned.[17]

NEWER APPROACHES IN BEHAVIOR CHANGE COMMUNICATION

The concept of positive deviance (PD) is based on the observation that “in every community/organization, there are a few individuals/groups whose uncommon but successful behaviours and strategies have enabled them to find better solutions to problems than their neighbours who face the same challenges and barriers and have access to same resources (pp: 2).”[18] It deals with identifying solutions for common problems that are already existing in the system.[19] It was first applied in 1970s in nutritional researches but the PD approach that was followed in Vietnam for the issue of malnutrition in 1990s is a prototype one.[20,21]

Another new approach in BCC is the Trials of Improved Practices (TIPS) which is “a participatory formative research approach used to test and refine potential health interventions on a small scale before introducing them broadly (pp: 1).”[22] It was first applied in 1979 by the Manoff Group in Indonesia's Nutrition Communication and Behaviour Change Project.[22] Now, it is widely applied in nutrition, hygiene practices, human immunodeficiency virus prevention, school health, maternal health, family planning, use of insecticide treated bed nets and prevention of indoor air pollution. TIPS also aids in the improvement of practices of caregivers and health-care providers.[22]

APPLICABILITY OF BEHAVIOR CHANGE COMMUNICATION-PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE

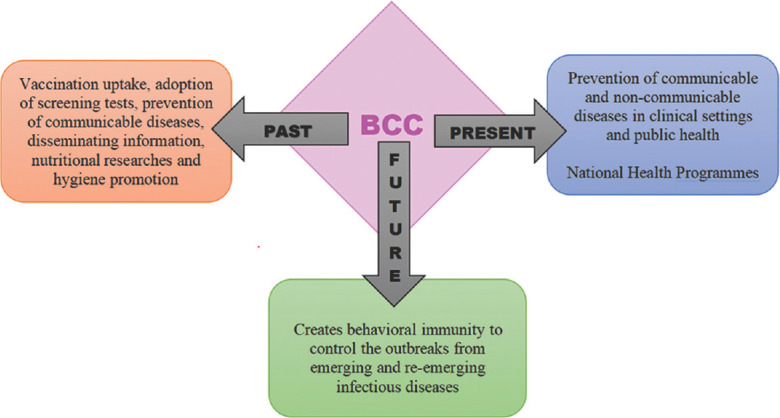

BCC has valid applications in both clinical settings and public health from the past to the future [Figure 1]. In clinical settings, BCC helps in counseling for de-addiction and screening tests, increases the patient's knowledge about his health problem and improves the doctor–patient communication.[1] In public health, it aids in contradicting the myths and misunderstandings present in the society. In the National Health Programmes, IEC activities and BCC interventions are widely used to guide the people regarding the benefits available under various schemes/programs and its accessibility.[5] It influences policy makers to promote new services and also aids in the inter-professional collaboration.[1]

Figure 1.

Applicability of behavior change communication in the past, present, and future

In the future, newer challenges like outbreaks from emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases need to be addressed. Emerging infectious diseases are “those due to newly identified and previously unknown infections which cause public health problems either locally/internationally (pp: 1).”[23] While re-emerging infectious diseases are “those due to the reappearance and increase of infections which are known, but had formally fallen to levels so low that they were no longer considered a public health problem (pp: 1).”[23] Some of the recent emerging infections are Ebola, H1N1 Influenza, MERS, Avian Influenza, SARS, Hanta virus, Zika virus and COVID 19 and re-emerging infections are malaria, tuberculosis, cholera, pertussis, pneumonia, and gonorrhea.[24] In the absence of effective drug/vaccine, these emerging diseases may be tackled by developing behavioral immunity through effective BCC strategies having a theoretical base. BCC theories/models may be applied at the individual, inter-personal, or community levels for the control of current COVID 19 pandemic [Table 1].

Table 1.

Applying behavior change communication theories/models at various levels to control the current COVID-19 pandemic

| Level | BCC theories/models | Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Individual level (psychological) | Health belief model | Perceived risks, benefits and barriers - Mass media campaigns and reminders from physicians |

| Theory of planned behavior | Subjective norms - Advice from family members, peer pressure and experience sharing Attitude and perceived behavioral control - Showing positive outcomes and providing personal protective aids |

|

| Trans-theoretical model | Precontemplation - Create awareness and provide information Contemplation - Help talk about pros and cons, affirm his strengths/abilities, give hope and suggest tips on quitting unhygienic practices Preparation - Assist in developing action plans Action - Giving rewards, social support and problem solving Maintenance - Reminder communications and obtaining feedback Relapse - Reassurance and assist in problem solving |

|

| Inter-personal level (psycho-social) | Social cognitive theory | Create awareness, provide information, social support (work from home, online classes, economic support from government), role models and emotional coping responses |

| Community level (socio-cultural) | Diffusion of innovation theory | Innovators and early adopters - provide informationEarly and late majority - Showing evidence of reduction in COVID cases due to lockdown Laggards - Peer pressure, showing mortality and morbidity statistics and enforcing strict rules |

| Positive deviance approach and trials of improved practices | Identify PD in the community and discover the successful behaviours for managing economic crisis during lockdown and make others apply it |

PD: Positive deviance, BCC: Behavior change communication

CONCLUSION

BCC had evolved over years from HE and concentrates mainly on providing a conducive environment for promoting a sustained behavior change. Various theories/models demonstrating behavior change were put forward and in practice, no theory is perfect and has certain limitations. A battery of theories may be needed to develop a BCC strategy. Therefore, an integrated behavioral model utilizing two or more theories operating at the individual, inter-personal, and community level may yield better results.[25] BCC has valid applications in both clinical settings and public health in the prevention of communicable and noncommunicable diseases. In the foreseeable future, outbreaks from emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases need to be tackled with behavioral immunity.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge all the faculties and postgraduates in the Department of Community Medicine, Sri Manakula Vinayagar Medical College for their valuable comments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Family Health International. Strategic framework: Behaviour Change Communication (BCC) for HIV/AIDS. Family Health International. 2002. [Last accessed on 2020 May 30]. Available from: http://www.hivpolicy.org/Library/HPP000533.pdf .

- 2.World Health Organization. Education for Health. World Health Organization. 1988. [Last accessed on 2020 May 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/topics/health_education/en/

- 3.Park K. Textbook of Preventive and Social Medicine. 25th ed. Jabalpur: Banarasidas Bhanot; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Information, Education and Communication: Lessons from the Past; Perspectives for the Future. World Health Organization. 2001. [Last accessed on 2020 May 30]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/67127/WHO_RHR_01.22.pdf;jsessionid=13A031E706DF802881068E08834DD7AA?sequence=1 .

- 5.National Health Mission. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. IEC/BCC. National Health Mission. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 May 30]. Available from: https://nhm.gujarat.gov.in/iec-bcc.htm .

- 6.Haidt J. The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom. 1st ed. New York: Basic Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas J. Scholarly views on theory: Its nature, practical application and relation to world view in business research. Int J Behav Med. 2017;12:231–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mckee N, Manoncourt E, Yoon CS, Carnegie R. Involving people, Evolving Behaviours: The UNICEF Experience. 1st ed. Paris: UNESCO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackenzie KR. Theories of group behaviour. Int J Group Psychother. 2015;39:271–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenstock I, Strecher V, Becker M. The Health Belief Model and HIV Risk Behaviour Change. 1st ed. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Family Health International. Behavior-Change-A-Summary-of-Four-MajorTheories. Family Health International. 2002. [Last accessed on 2020 May 30]. Available from: https://www.scribd.com/document/22685465/Behavior-Change-A-Summary-of-Four-MajorTheories .

- 12.Fishbein M, Middlestadt SE, Hitchcock PJ. Using Information to Change Sexually Transmitted Disease-Related Behaviours. 1st ed. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prochaska JO, Diclemente CC. Towards a Comprehensive Model of Change. 1st ed. New York: Plenum Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12:38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandura A. The Social and Policy Impact of Social Cognitive Theory. 1st ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaminski J. Diffusion of innovation theory. Can J Nurs Inform. 2011;6:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tufts University. Basic field guide to the Positive Deviance Approach. 2010. [Last accessed on 2020 May 30]. Available from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a1eeb26fe54ef288246a688/t/5a6eca16c83025f9bac2eeff/1517210135326/FINALguide10072010.pdf .

- 19.Baxter R, Taylor N, Kellar I, Lawton R. Learnings from positively deviant wards to improve patient safety: An observational study protocol. BMJ Open. 2015;5:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wishik SM, Vynckt VD. The use of nuritional positive deviants to identify approaches for modification of dietary practices. Am J Public Health. 1976;66:38–42. doi: 10.2105/ajph.66.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marsh DR, Schroeder DG, Dearden KA, Sternin J, Sternin M. The power of positive deviance. BMJ. 2004;329:1177–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manoff Group. Trials of Improved Practices: Engaging People, Enhancing Impact. 2015. [Last accessed on 2020 May 30]. Available from: https://coregroup.org/wp-content/uploads/media-backup/documentts/1._TIPs_for_Core_Group_1.pdf .

- 23.World Health Organization. Emerging Infectious Diseases. World Health Organization. 1997. [Last accessed on 2020 May 30]. https://www.who.int/docstore/world-health-day/en/documents1997/whd01.pdf .

- 24.John Hopkins Medicine. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 May 30]. Available from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/emerging-infectious-diseases .

- 25.Health Behaviour and Health Education. Integrated Behavioural Model. Health Behaviour and Health Education. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 May 30]. Available from: https://www.med.upenn.edu/hbhe4/part2-ch4-integrated-behavior-model.shtml .