SUMMARY

Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (PMD) is an X-linked leukodystrophy caused by mutations in Proteolipid Protein 1 (PLP1), encoding a major myelin protein, resulting in profound developmental delay and early lethality. Previous work showed involvement of unfolded protein response (UPR) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress pathways, but poor PLP1 geno-type-phenotype associations suggest additional pathogenetic mechanisms. Using induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) and gene-correction, we show that patient-derived oligodendrocytes can develop to the pre-myelinating stage, but subsequently undergo cell death. Mutant oligodendrocytes demonstrated key hallmarks of ferroptosis including lipid peroxidation, abnormal iron metabolism, and hypersensitivity to free iron. Iron chelation rescued mutant oligodendrocyte apoptosis, survival, and differentiation in vitro, and post-transplantation in vivo. Finally, systemic treatment of Plp1 mutant Jimpy mice with deferiprone, a small molecule iron chelator, reduced oligodendrocyte apoptosis and enabled myelin formation. Thus, oligodendrocyte iron-induced cell death and myelination is rescued by iron chelation in PMD pre-clinical models.

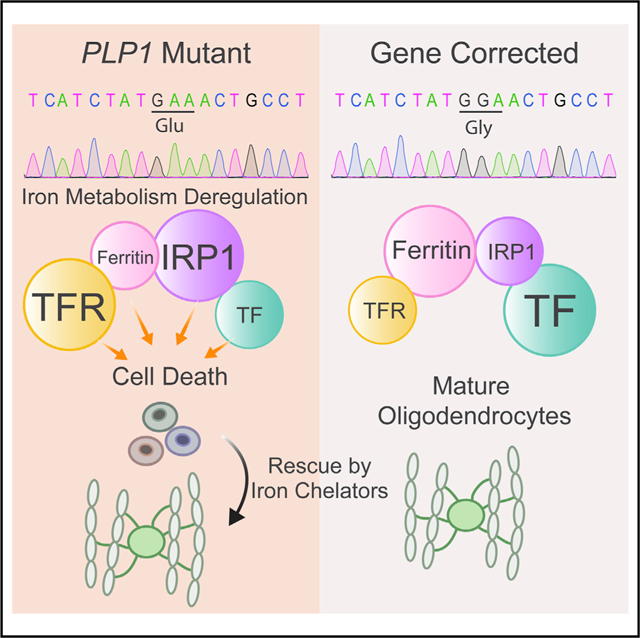

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease is a pediatric leukodystrophy causing oligodendrocyte cell death. Nobuta et al. show that mutations in human PLP1 gene cause iron-induced cell death through lipid peroxidation, abnormal iron metabolism, and hypersensitivity to free iron. Iron chelation rescues cell death, offering a therapeutic direction for a disease without current treatments.

INTRODUCTION

Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (PMD) is a congenital X-linked recessive leukodystrophy caused by mutations in the Proteolipid Protein 1 (PLP1) gene with an incidence of 1:200,000 to 1:500,000 (Hobson and Kamholz, 1999). PLP1 is one of the main protein components in myelin of the CNS, and lack of myelination is the main pathological characteristic of the disease. Accordingly, the clinical presentation can show pervasive neuro-developmental delay and generalized low muscle tone. Early-severe (aka connatal) PMD patients show respiratory difficulties and nystagmus at birth and later neurodegeneration and death at early teenage years (Woodward, 2008).

PLP1 mutations comprising gene duplications, and missense point mutations of PLP1 can result in marked hypomyelination of the CNS (Woodward, 2008). While loss-of-function mutations also can occur, these typically show the mildest phenotypes (Sistermans et al., 1996). How these PLP1 mutations lead to lack of myelination, however, is not well understood, and therefore no curative treatment options are currently available. Studies in mice and tissue culture cells have shown that oligodendrocytes, the myelinating cells of CNS, can be dysfunctional and abnormal Plp1 trafficking in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of oligodendrocytes can lead to apoptosis by activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) (Dhaunchak and Nave, 2007; Elitt et al., 2018; Krämer-Albers et al., 2006). These studies suggest deficiencies in oligodendrocyte survival rather than problems of myelin composition with mutant PLP1. The involvement of ER stress and activation of the UPR could be confirmed in human oligodendrocyte cell models that were derived from patients’ induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (Nevin et al., 2017; Numasawa-Kuroiwa et al., 2014). Of note, a recent study demonstrated that only a subset of PLP1 mutations show activation of an UPR in patient iPSC-derived oligodendrocytes (Nevin et al., 2017). Together with the lack of a consistent genotype-phenotype correlation in patients, this result suggests the existence of additional pathobiological mechanisms that lead to dysfunctional oligodendrocytes or myelin formation in PMD. Here, we therefore investigated the cell biological consequences of PLP1 mutations in greater detail using patient iPSC-derived oligodendrocytes and genetically corrected controls as a model system.

RESULTS

PLP1G74E Mutant Oligodendrocytes Develop but Subsequently Die and Cannot Properly Differentiate into Myelinating Cells

To generate human cellular models of PMD, we initially obtained a skin biopsy from a PMD patient with early-severe PMD who presented with nystagmus, respiratory distress, loss of developmental milestones, spasticity, and hypomyelination (Gupta et al., 2012). Genotyping revealed a point mutation in PLP1 gene at G74E (hereafter PLP1G74E mutation), which causes a single amino acid change from glycine to glutamic acid in the second transmembrane domain (Figures 1A and 1C). We generated patient iPSC lines by episomal reprogramming (Diecke et al., 2015) that showed typical features of pluripotency (expression of OCT4, TRA 1–60, and generation of mature teratomas) and normal karyotype (Figures S1A–S1C).

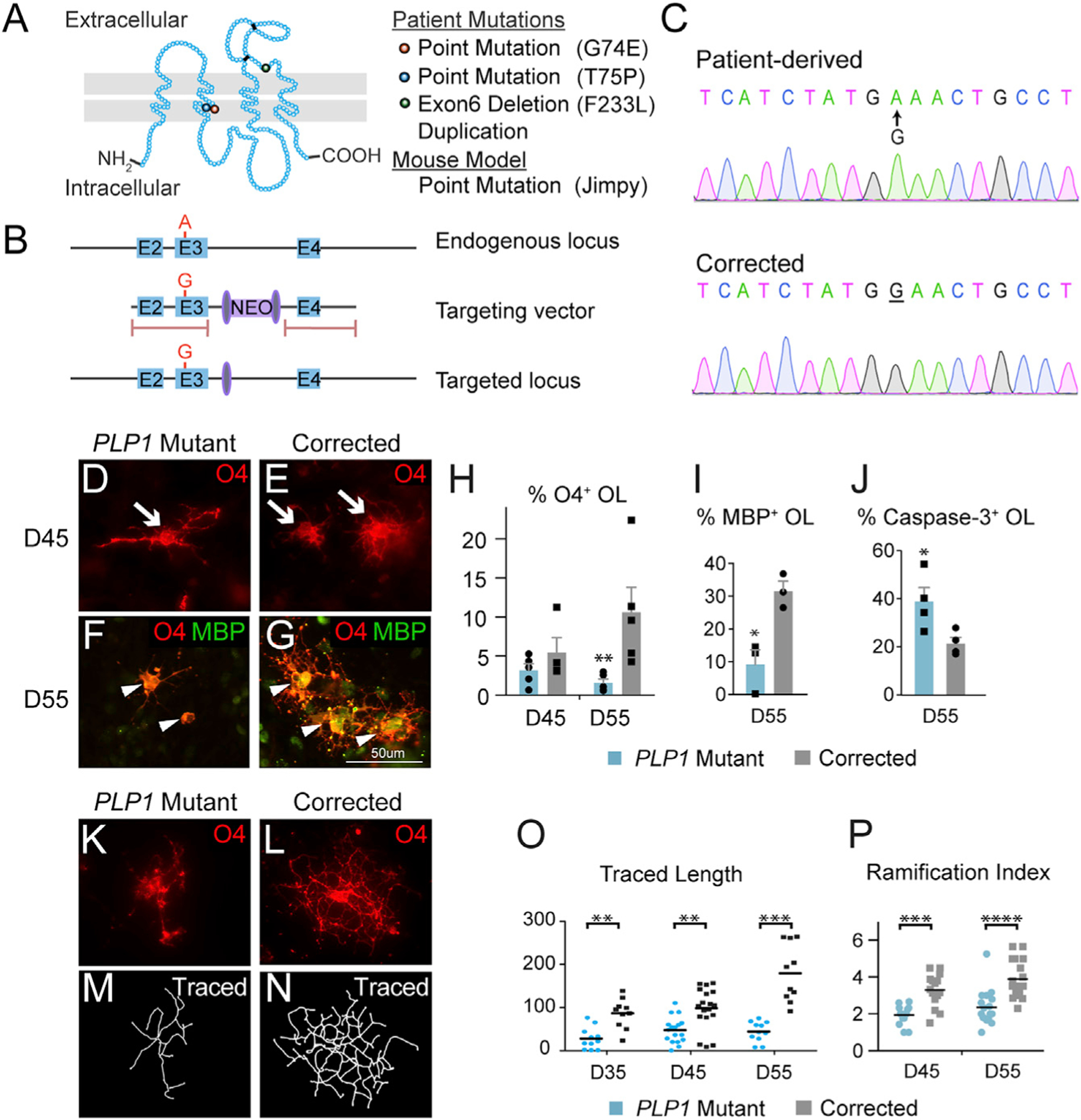

Figure 1. PMD Oligodendrocytes Die Prematurely and Fail to Differentiate with Ramified Morphology.

(A) Three G74E, T75P, and F233L point mutations in PLP1 described in this paper are located in the second transmembrane domain or extracellular domain. An additional duplication mutation as well as a mouse point mutation (Jimpy mouse) were investigated in this study.

(B) Gene targeting strategy to correct the G74E point mutation in exon 3. The targeting vector was cloned into an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector along with neomycin resistant cassette flanked by loxP sites. Pink bars represent locations for homologous recombination. The neomycin cassette was removed by a transient Cre transfection.

(C) Sanger sequencing validated the accurate correction.

(D and E) On D45, mutant (D) and corrected (E) iPSCs had differentiated to normal-appearing O4+ OPCs.

(F and G) On D55, the mutant (F) cells were fewer, morphologically simpler, and expressed minimum levels of the maturation marker MBP compared to the corrected cells (G).

(H) Quantification of O4+ cells by flow cytometry on D45 and D55 showed progredient loss of cells (n = 3–5, biological replicates).

(I) Immunofluorescent quantification of MBP+/O4+ cells at D55 showed a differentiation block of mutant cells (n = 3–4, biological replicates).

(J) PLP1 mutant cells showed an increased fraction of caspase-3+/O4+ cells at D55 (n = 3–4, biological replicates).

(K–P) Assessment of morphological complexity in O4+ cells using Sholl analysis software. Immunofluorescent images of O4+ cells were captured, then individual cell morphology was reconstructed by tracing the O4 stained branches assisted by Fiji plugin software Simple Neurite Tracer. Quantification showed failure of the mutant cells (K, M, O, P) to achieve time-dependent increase in total traced length and ramification index (n = 11–18 cells/treatment) compared to the corrected cells (L, N, O, P).

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

To assess potential phenotypic abnormalities in patient-derived oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs), we adapted an established protocol (Figure S2A; Douvaras and Fossati, 2015; Wang et al., 2013). Oligodendrocyte differentiation of these lines evidenced significant clone-to-clone variability (Figure S2B), prompting us to develop line-specific isogenic controls for this study. To that end, we corrected the PLP1G74E mutation in this patient’s iPSCs using adeno-associated virus-mediated homologous recombination (Figure S2D). Reassuringly, PMD mutant and gene-corrected iPSCs now showed similar differentiation dynamics as determined by appearance of neural rosettes and SOX1-, PAX6-, NKX2.2-, OLIG2-, and PLP1-expressing cells (Figure S2E) and reduced variability in oligodendrocyte generation within subclones (clonal lines obtained from single colonies after gene-correction of a parental clone) (Figure S2C). Expression of O4, a marker of oligodendrocytes at a pre-myelinating stage with immature morphology, first appeared around day 35 (D35) in both mutant and corrected cells and increased subsequently (Figure S2F). Although on D45 numbers of mutant and corrected O4+ cells were similar (Figures 1D, 1E, and 1H), by D55 we observed significant losses of O4+ mutant cells compared to isogenic controls (Figures 1F, 1G, 1H, and S2G). The onset of this phenotype was accompanied by induction of the mutant PLP1 protein in mutant cells at around D45 (Figure S2F). Remaining O4+ mutant cells failed to differentiate into MBP+ cells with mature and ramified oligodendrocyte morphology (Figures 1K–1P) and did not acquire robust expression of the mature marker myelin basic protein (MBP) (Figures 1F, 1G, and 1I). While we found approximately twice as many caspase-3+ mutant cells on D55, indicating apoptosis, this mechanism alone did not account for the observed 5-fold levels of cell attrition and suggested additional mechanisms of cell death (Figures 1J and S2H).

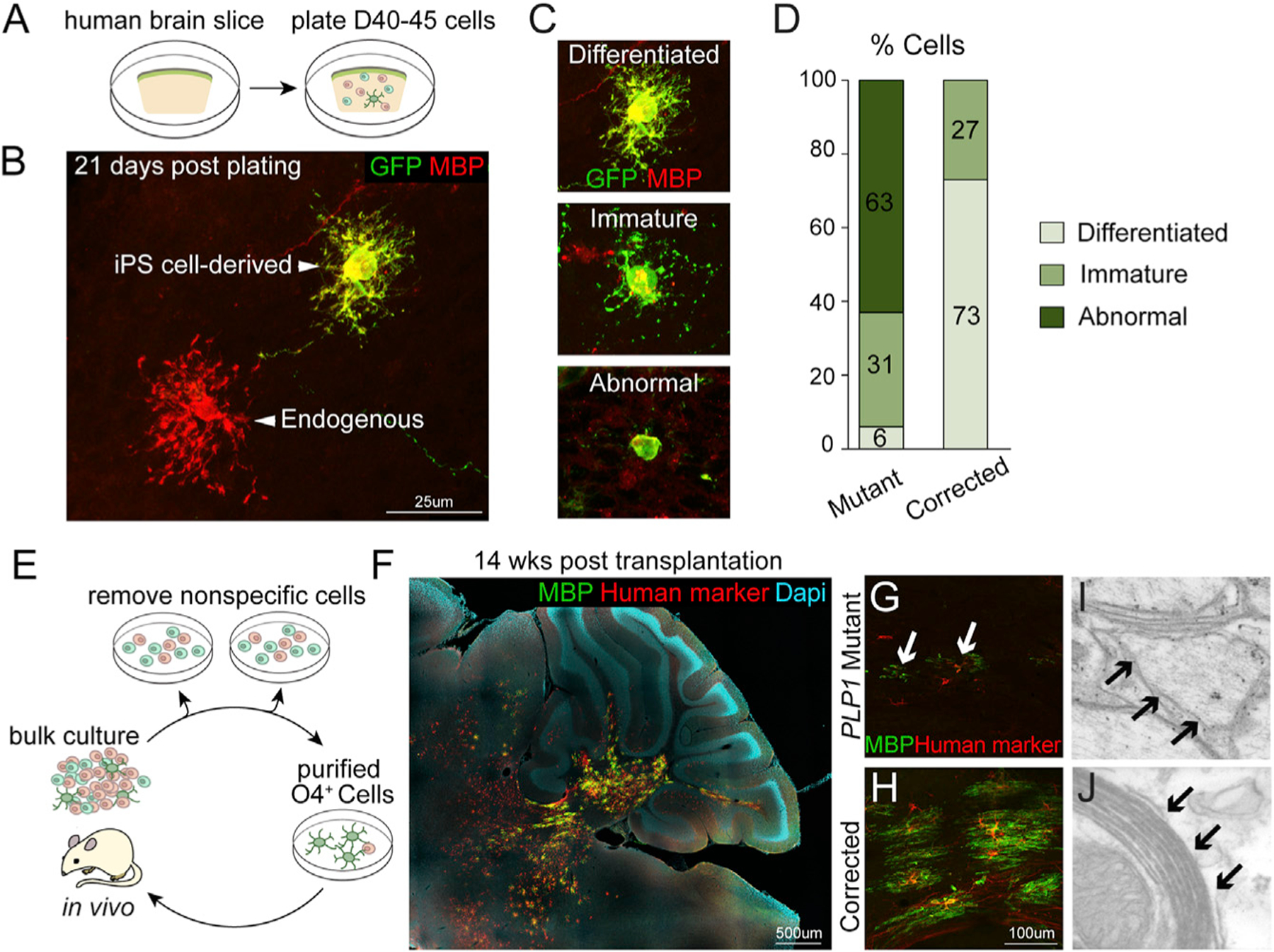

Next, we sought to test the myelination capacity of human PMD mutant and gene-corrected OPCs. When plated on previously established human fetal brain slice explant cultures (Figure 2A; see STAR Methods) (Hansen et al., 2010) and analyzed at the limit of culture duration (3 weeks), mutant cells failed to acquire mature oligodendrocyte morphology or expressed minimal level of MBP, contrasting the gene-corrected cells (Figures 2B–2D). We then transplanted mutant and corrected OPCs into the brains of immunocompromised Shiverer (Shi) mice, which lack compact myelin due to disruption of the Mbp gene and die at around 16 weeks of age (Roach et al., 1983). We purified iPSC-derived OPCs by O4+ antibody-based immunopanning (Harrington et al., 2010; Figure 2E) and transplanted them into the cerebellum of Shi mice at postnatal day (P) 1. Unlike mutant cells, 13 weeks post-transplantation near animal’s death, corrected human OPCs migrated from the injection site and differentiated into robustly MBP+ oligodendrocytes that exhibited a typical morphology with membrane ensheathment of multiple axons (Figures 2F and 2H) (mean MBP+/human specific marker+ cells per unit area: mutant 0.875 ± 0.295, corrected 8.125 ± 0.990, t test p = 0.0003). Electron microscopic analysis showed restoration of compact myelin in areas transplanted with corrected cells (G-ratio 0.8453 ± 0.02878) but not with mutant cells (G-ratio 0.9238 ± 0.00975, t test p = 0.0039) (Figures 2I and 2J). In contrast, most mutant cells even failed to survive in the host brain (Figure 2G). Thus, the PLP1G74E mutation rendered oligodendrocytes unable to survive or achieve terminal differentiation in vitro, in explant slices ex vivo, or in mouse brain in vivo.

Figure 2. Gene Correction in PLP1G74E Mutation Rescues Oligodendrocyte Differentiation and Axonal Myelination.

(A) Schematic of co-culture system of human brain slice and EGFP-labeled, iPSC-derived OPCs.

(B) At 21 days after co-culture, iPSC-derived gene corrected oligodendrocytes (EGFP+/MBP+) showed similar morphologies as endogenous oligodendrocytes (EGFP−/MBP+).

(C) Classification of MBP+ cells based on morphological complexity.

(D) PLP1G74E mutant oligodendrocytes had mostly abnormal or immature morphologies (n = 6–9 slices/ group, total number of transplanted oligodendrocytes pooled for analysis).

(E) For in vivo transplantation, O4+ OPCs were purified by removal of lectin+ nonspecific cells, followed by O4 immunopanning. Cells were transplanted into the cerebellum of postnatal immune-deficient Shiverer mice (n = 3–4).

(F) MBP (green) and the human-specific antibody STEM121 (red) detected many corrected iPSC-derived oligodendrocytes after transplantation. The composite image was constructed by automated tiling of images taken at 10× magnification. (G and H) Corrected cells (H) engrafted and efficiently differentiated to MBP+ oligodendrocytes whereas transplanted PLP1G74E mutant cells (G) failed to survive in the host brain.

(I) Electron microscopy of the transplanted area. Only thinly and loosely myelinated axons were found in Shiverer mouse transplanted with PLP1G74E mutant cells.

(J) Electron microscopy of area transplanted with corrected cells revealed multi-layer, compact myelin.

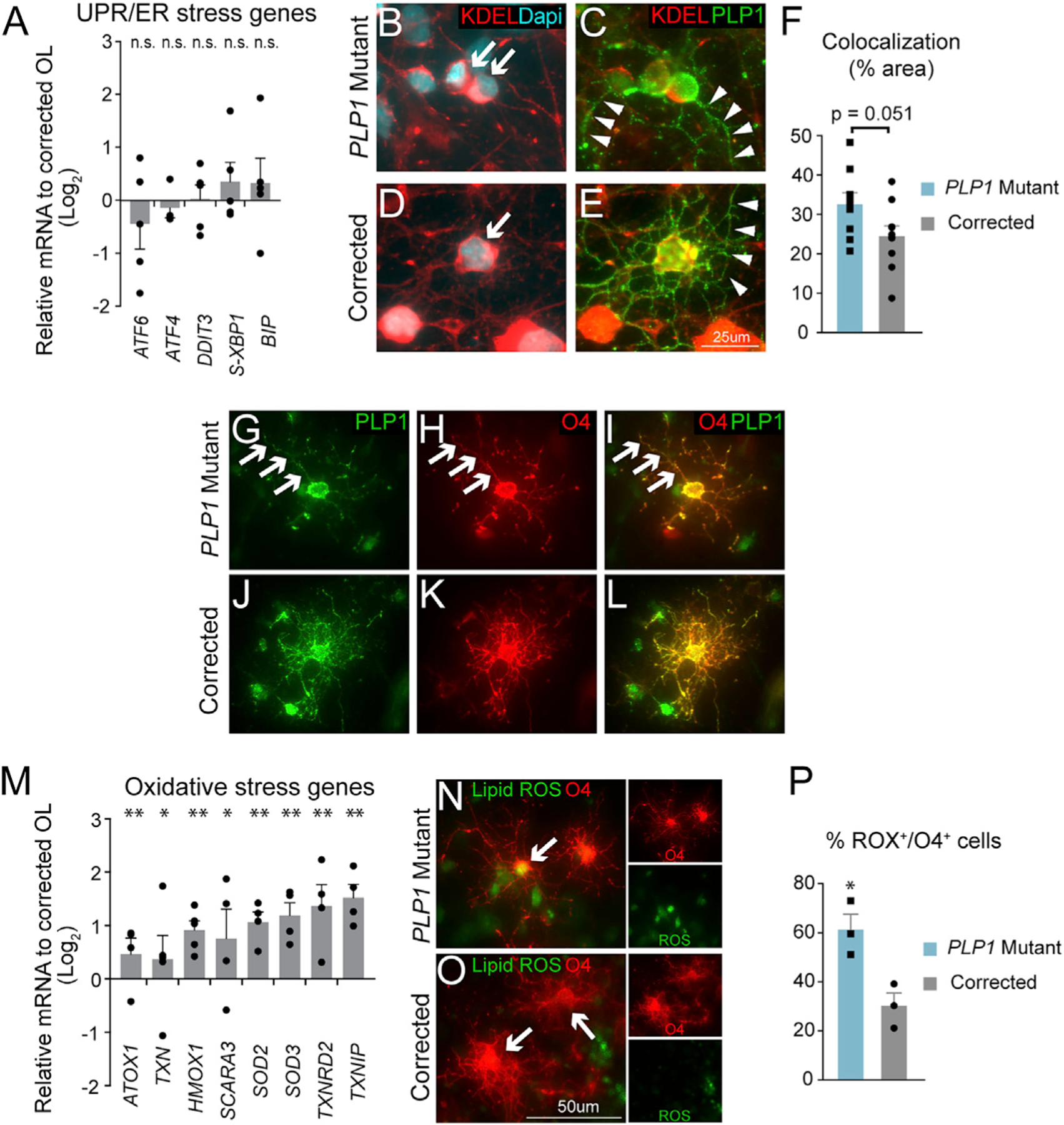

Lack of ER Stress and Unfolded Protein Response in PLP1G74E Mutant Cells

ER stress and activation of the UPR pathway leading to apoptosis is implicated for PLP1 mutations in mouse models (Dhaunchak and Nave, 2007; Elitt et al., 2018; Krämer-Albers et al., 2006; Numasawa-Kuroiwa et al., 2014; Southwood et al., 2002; see also Nevin et al., 2017). Because conventional apoptosis could only partially explain observed cell death (see above), we next investigated the underlying mechanisms of the survival and differentiation deficiency of PMD mutant cells. Surprisingly, we found that UPR/ER stress pathway genes were not activated in purified human O4+ cells from the PLP1G74E mutant oligodendrocytes (Figure 3A). We also did not observe accumulation of the PLP1G74E mutant protein in the ER, instead we found it extensively dispersed from the ER into the fine processes of the cell (Figures 3C, 3E, and 3G–3L). We could find only rare examples of mutant PLP1 protein that co-localized with the ER marker KDEL (Figures 3B, 3D, and 3F), indicating ER retention was minimal. We tested inhibitors of the ER stress pathways but these did not rescue survival PLP1G74E mutant oligodendrocytes in culture (Figure S3A). Finally, transplanted mutant OPCs did not express the ER stress marker CHOP protein in vivo (Figure S3B). Together, these findings indicated that cell death of PLP1G74E mutant OPCs did not involve significant UPR or ER stress pathway activation and suggested additional pathobiological pathways.

Figure 3. Lack of Evidence for ER Stress and Evidence for Abnormal Iron Metabolism and Oxidative Stress in PLP1G74E Mutant OPCs.

(A) qPCR quantification of UPR and ER stress genes in PLP1G74E mutant and corrected OPCs showed no significant difference with corrected cells (n = 3–4, biological replicates).

(B and D) Little co-localization of mutant PLP1G74E protein (B) and the ER marker KDEL (arrows) similar to the corrected (D).

(C and E) Instead PLP1G74E (C) localized to fine processes (arrowheads) similar to wild-type PLP1

(E) in corrected cells (n = 9 fields/group).

(F) Quantification of overlapping (colocalizing) staining with KDEL and PLP1 showed a trend but no significant difference between PLP1G74E mutant and gene corrected oligodendrocytes. (G–L) Evidence of PLP1G74E protein (G–I) transported out of ER to near O4+ cell surface locations similar to wild-type PLP1 in the corrected cells (J–L).

(M) Induction of oxidative stress genes in PLP1G74E mutant cells revealed by qPCR (n = 4–5, biological replicates).

(N–P) Increased levels of oxidative species in live mutant OPCs (N and P) detected with CellROX dye at D55 of differentiation (n = 3, biological replicates) in comparison to the corrected cells (O–P).

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n.s. = not significant. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

Accumulation of Oxidative Species and Activation of Oxidative Stress Genes in PLP1G74E Mutant Oligodendrocytes

Oxidative stress is a common pathogenetic mechanism in many neurological disorders. Indeed, purified PLP1G74E mutant OPCs showed strong induction of several oxidative stress marker genes when compared to gene-corrected OPCs (Figure 3M). Moreover, mutant cultures more strongly labeled with CellROX, a dye that detects reactive oxygen species (ROS) in live cells, compared to gene-corrected cultures, and a higher fraction of mutant OPCs were labeled with the dye (Figures 3N–3P). We conclude that the PLP1G74E mutation induced high oxidation levels in OPCs. The potential causes of increased oxidation are manifold, and we therefore continued to search for additional pathological abnormalities in mutant cells.

Marked Deregulation of Iron Metabolism in Human PLP1G74E Mutant Oligodendrocytes

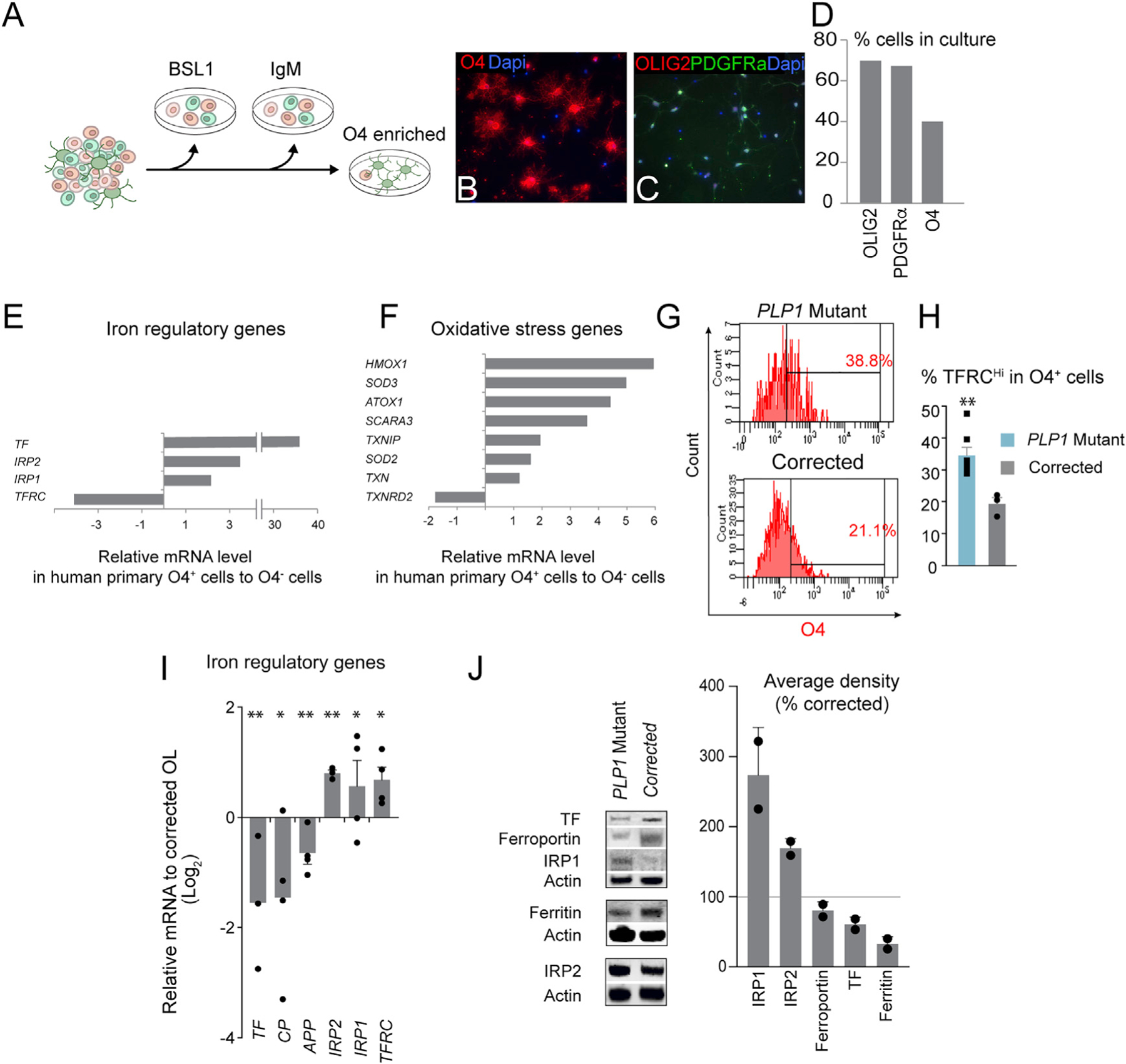

Rodent oligodendrocytes express high levels of transferrin (TF) (Espinosa de los Monteros et al., 1999; Leitner and Connor, 2012; Zhang et al., 2014), the major iron transporter for intracellular uptake of iron (Brissot and Loréal, 2016; Hentze et al., 2010). We confirmed similar findings in human cells, relatively high TF expression in primary fetal human O4+ oligodendrocytes (Figures 4A–4D) compared to other neural cells (Figure 4E) and increased levels of oxidative stress genes (Figure 4F). Dysregulation in iron metabolism can pose oxidative stress for which oligodendrocytes are particularly vulnerable (Back et al., 1998; Butts et al., 2008; Khorchid et al., 2002). We therefore investigated whether iron metabolism was dysregulated in PMD mutant cells. Expression profiling showed several iron regulation genes were indeed significantly de-regulated including transferrin itself (Figure 4I). To further corroborate these findings, we performed quantitative immunoblotting of some key iron regulatory proteins. PLP1G74E mutant OPCs showed a consistent downregulation of TF (iron transporter) and ferritin (iron storage) and upregulation of the iron regulatory protein 1 (IRP1) (Figure 4J). Flow cytometric analysis of mutant and corrected oligodendrocytes revealed an ~2-fold upregulation of the transferrin receptor (Figures 4G, 4H, and S4A).

Figure 4. Unique Iron Regulation and Oxidative Stress in Human Oligodendrocytes and PLP1G74E Mutation.

(A) Schematic of human oligodendrocyte isolation. The brain tissue is dissociated into single cells, and passed through lectin (BSL) and mouse IgM secondary antibody-coated plates to remove non-specific cells. O4+ oligodendrocytes are then positively selected by attaching them to an O4-coated plate.

(B–D) Isolated cells bound to O4 antibody (B and D) showed other markers of oligodendrocyte markers such as OLIG2 and PDGFRα.

(E) qPCR quantification of iron regulatory genes in human endogenous O4+ oligodendrocytes versus the rest of the neural cells unbound to the O4 antibody revealed an exceptionally high TF expression in oligodendrocytes.

(F) Quantification of oxidative stress gene expression in human O4+ oligodendrocytes versus the rest of the neural cells by qPCR revealed naturally high level of oxidative stress in healthy human oligodendrocytes.

(G) Representative flow cytometry plot quantifying the level of TF receptor (TFRC) in O4+ OPCs.

(H) Increased surface expression TFRC in mutant OPCs determined by flow cytometry (n = 3–7, biological replicates). **p < 0.01.

(I) Abnormal expression of iron regulatory genes in mutant OPCs by qPCR (n = 3–4, biological replicates). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

(J) Western blot analysis of iron regulatory proteins (two pooled samples of n = 3–4 biological replicates).

Human PLP1G74E Mutant Oligodendrocytes Exhibit Hallmarks of Ferroptosis: Iron-Toxicity and Lipid Peroxidation

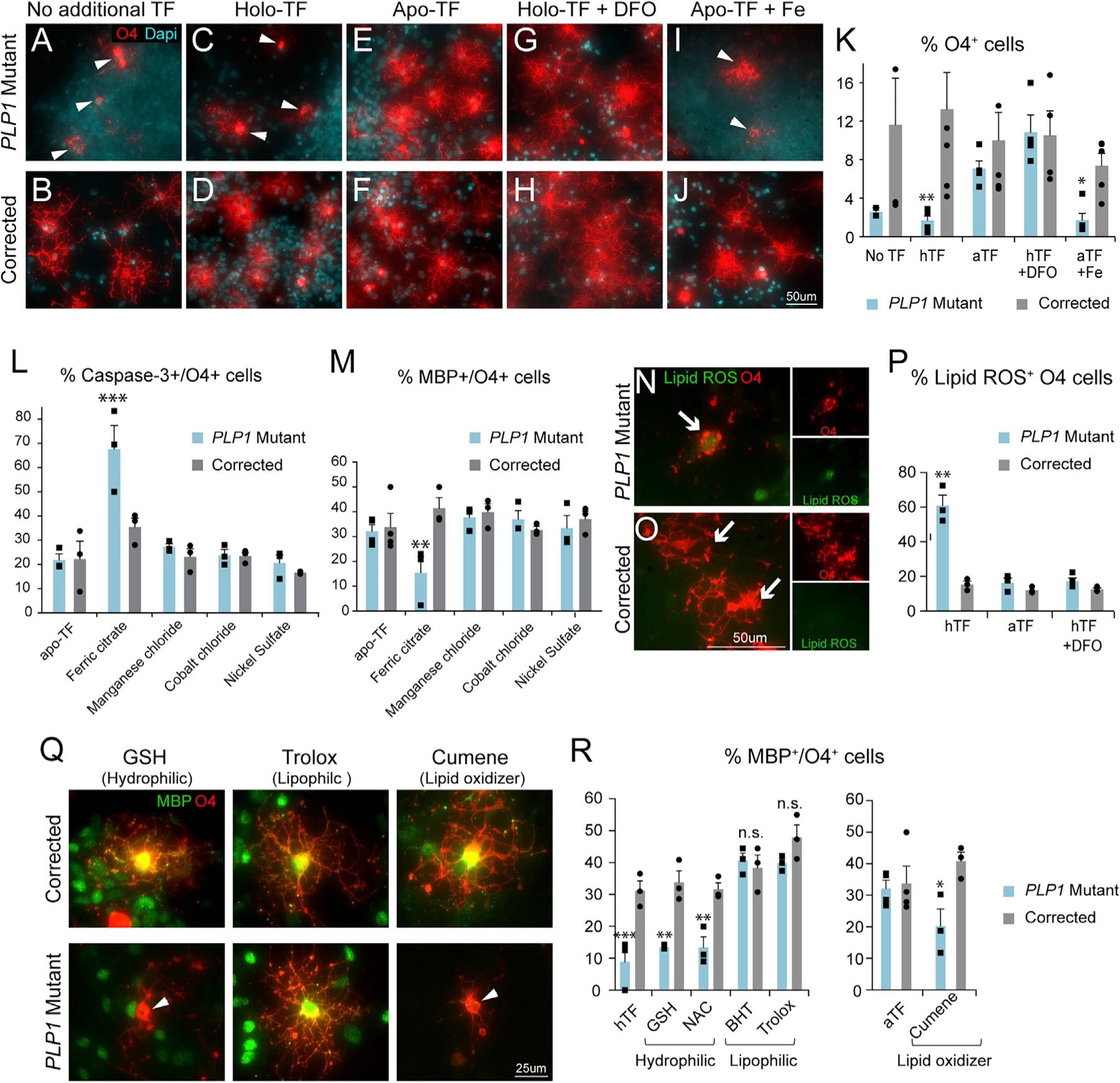

Having observed a dysregulation of key iron metabolism regulatory proteins, we sought to explore potential functional consequences of these expression changes. To investigate the role of TF and free iron, we differentiated mutant and corrected iPSCs without additional TF, with addition of (iron-free) apo-transferrin (TF) or (iron-bound) holo-TF from days 35 to 55. This is the time frame in which mutant oligodendrocyte cell death begins and PLP1 protein expression is initiated (Figure S2F). Remarkably, addition of apo-TF to the media completely restored mutant oligodendrocytes’ viability to the level of genetic rescue (Figures 5A–5F and 5K). Apo-TF is a central extracellular iron transporter and has high affinity for free iron; thus, it effectively reduces free extracellular iron concentration as a chelator while making it available to cells as holo-TF via TF receptors. Because addition of holo-TF did not have beneficial effects (Figures 5C, 5D, and 5K), we deduced that the rescue is caused by the effective decrease of the extracellular iron concentration rather than making more iron available to cells. This conclusion is corroborated by our observation that the two Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved small molecule iron chelators deferoxamine (DFO) and deferiprone (DFP) rescued mutant cells just as Apo-TF treatment did (Figures 5G, 5H, 5K, S4B, and S4C). Elevating the extracellular iron concentration reversed effects of apo-TF in mutant cells suggesting an iron-specific effect (Figures 5I–5K). Indeed, no other divalent transition metal ions tested led to increased apoptosis or halted differentiation in mutant or corrected oligodendrocytes (Figures 5L and 5M). We further found that Apo-TF, DFO, or DFP treatment normalized the overall number of O4+ cells, apoptosis, and differentiation into MBP+ cells (Figures S4B–S4E). Of note, Apo-TF treatment had no significant effect on gene-corrected control oligodendrocytes suggesting that the PLP1G74E mutation increased the sensitivity to iron in oligodendrocytes (Figures 5F and 5K).

Figure 5. Iron Chelation and Lipophilic Antioxidants Rescue Mutant Cell Survival and the Differentiation Block.

(A–D) In the baseline amount of TF or in the presence of iron-bound holo-TF, PLP1G74E mutant O4+ cells (A and C) degenerated on D55, which was rescued in the corrected cells (B and D).

(E and F) Reduction of free iron by apo-TF addition inhibited PLP1G74E mutant O4+ cell death (E) but had no effect on corrected cells (F).

(G–J) Reduction of iron by the iron chelator deferoxamine (DFO) in presence of holo-TF also blocked cell death in PLP1G74E mutant O4+ cells (G), similar to apo-TF. Additional iron administration counteracted the apo-TF effects (I). These treatments had no effect on corrected cells (H and J).

(K) Quantification of O4+ cells in all treatment groups by flow cytometry (n = 3–4, biological replicates).

(L and M) Quantification of cell death (L) and OPC differentiation (M) in O4+ cells.

(N–P) Increased lipid ROS level in PLP1G74E mutant cells (N and P) was rescued by the presence of apo-TF or DFO to the levels of corrected cells (O and P) (n = 3–4, biological replicates).

(Q and R) Immunofluorescence quantification of MBP/O4+ cells revealed that only the lipophilic antioxidants BHT or Trolox, but not the hydrophilic antioxidants GSH or NAC, rescued the differentiation defect of PLP1G74E mutant cells (n = 3–4).

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, n.s. = not significant. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

Iron-mediated cell death can be due to ferroptosis, which comprises iron-toxicity and iron-dependent lipid peroxidation (Dixon et al., 2012). We found that PLP1G74E mutant oligodendrocytes undergo increased oxidative stress and discovered that iron chelation normalizes ROX, an oxidation-sensitive dye in live cells (Figure S4F). To more specifically assess whether cells undergo lipid peroxidation, we optimized an assay for accumulation of lipid ROS for our oligodendrocyte cultures (Naguib, 1998). Indeed, PLP1G74E mutant cultures showed both general and oligodendrocyte-specific increase in lipid ROS, suggesting peroxidization of cellular lipids during differentiation (Figures 5N–5P). We noted that not all mutant cells showed accumulation of lipid ROS (<60% of O4+ cells), and together with the evidence for caspase-3-dependent apoptotic cell death in ~40% of O4+ cells (Figure 1J), we conclude that multiple modes of cell death were at work. Further studies are needed to confirm that lipid ROS production lies downstream of iron induced toxicity in oligodendrocytes affected by PMD that are rescued by chelation.

As shown (Figure 5P), addition of Apo-TF and DFO reduced lipid ROS+ cells to wild-type levels indicating that lipid peroxidation was iron-dependent. We next used a series of lipophilic and hydrophilic antioxidants to assess whether the lipid ROS is responsible for the mutant oligodendrocyte phenotype. Compared to hydrophilic antioxidants GSH and NAC, lipophilic antioxidants BHT and Trolox rescued oligodendrocyte differentiation and/or apoptosis (Figures 5Q, 5R, and S4G), supporting lipid ROS as the key inducer of mutant oligodendrocyte death. These findings indicate that the PLP1G74E mutation renders oligodendrocytes more sensitive to extracellular free iron, which leads to elevated lipid peroxidation, block of differentiation, and cell death—all key hallmarks of ferroptosis-mediated cell death.

Iron Chelation Rescues Survival and Maturation of Transplanted Human PLP1G74E Mutant Oligodendrocytes in Mouse Brains and Human Brain Slices

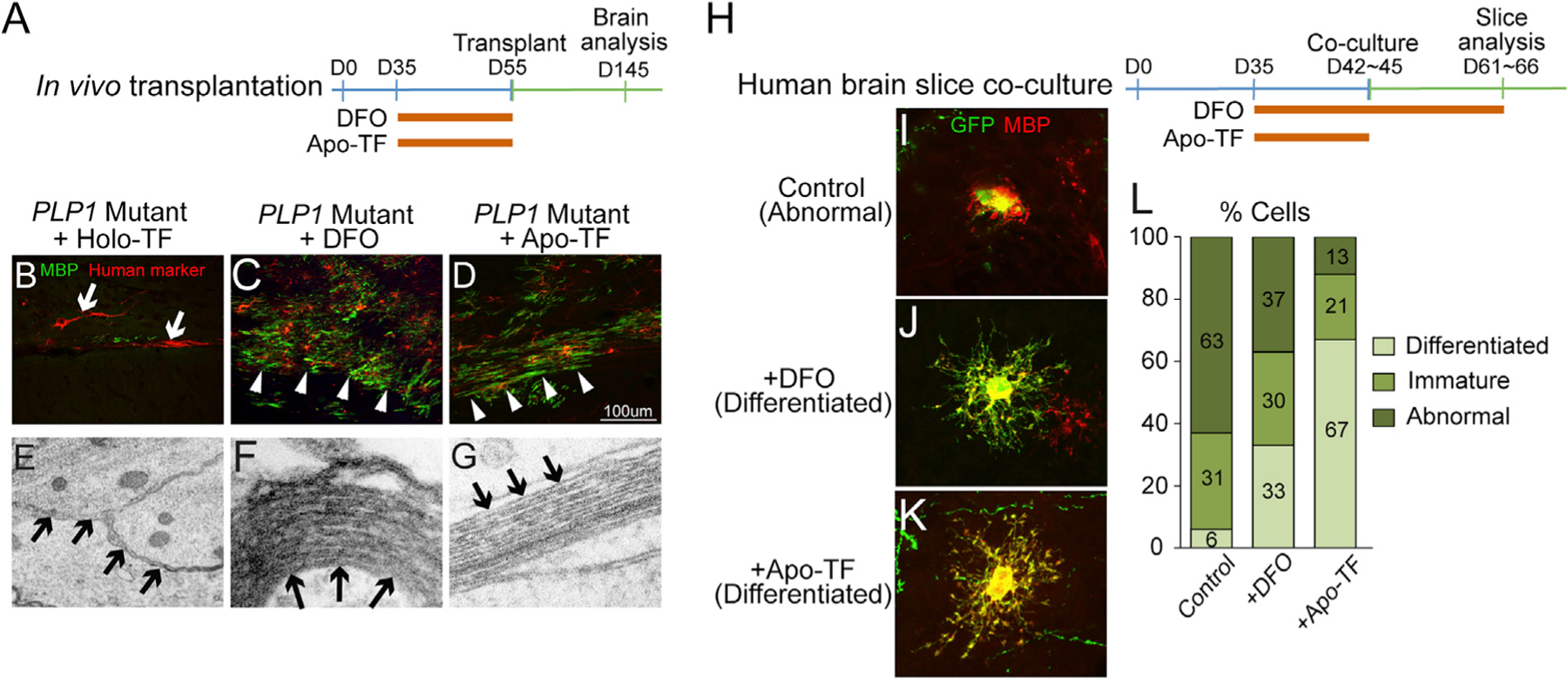

We next asked whether iron chelation would promote survival and differentiation of human PLP1 mutant OPCs in vivo. We tested whether O4+ mutant cells, grown in conditions of iron chelation, had enhanced survival and/or myelinating capacity in vivo. O4+ cells were purified and transplanted into the cerebellum of immunocompromised Shi mice (Figure 6A). Mutant human OPCs pre-treated with apo-TF or DFO from D35–D55 of the differentiation protocol readily engrafted and gave rise to mature MBP+ cells, in contrast to untreated cells (mean MBP+/human specific marker+ cells: untreated 0.875 ± 0.295, apo-TF-treated 8.80 ± 1.20, DFO-treated 8.40 ± 1.470, one-way ANOVA p < 0.0001) (Figures 6B–6D). Ultrastructural analysis showed multilayer ensheathment of axons by mutant apo-TF-treated (G-ratio 0.8318 ± 0.02442, p = 0.0008) or DFO-treated (G-ratio 0.8388 ± 0.0155, p = 0.0013) but not untreated cells (G-ratio 0.9238 ± 0.009750, one-way ANOVA p = 0.031) (Figures 6E–6G). Similarly, when mutant oligodendrocytes were pre-treated with apo-TF or DFO for 7–10 days and then placed on human fetal brain slice cultures, they showed a substantially improved differentiation (Figures 6H–6L). Thus, iron chelator pre-treatment of mutant O4+ OPCs enhanced survival and differentiation in mouse brain in vivo.

Figure 6. Iron Chelation Rescues Phenotypes of PLP1G74E Mutation Post Transplantation and in Slice Explant Culture.

(A) PLP1G74E mutant and corrected OPCs were transiently (D35–D55) treated with apo-TF or DFO before transplantation into the Shiverer mouse.

(B–D) Whereas untreated PLP1G74E mutant OPCs (B) failed to survive in the host brain, transient DFO (C) and apo-TF (D) treated OPCs survived and differentiated to mature MBP+ oligodendrocytes (n = 3).

(E–G) Ultrastructural assessment showed rescue of multi-layer myelination by the apo-TF (G) and DFO-treated (F) PLP1G74E mutant OPCs compared to the absence of myelination in areas transplanted with PLP1G74E mutant OPCs (E).

(H) Schematic of treatment regimen of human slice co-cultures with DFO or apo-TF.

(I–K) Transient and long-term iron chelation DFO (J) and apo-TF (K) rescued the differentiation block of PLP1G74E mutant OPCs (I) as seen by MBP staining of EGFP+ cells (4–8 slices/treatment group, total number of transplanted oligodendrocytes pooled for analysis).

(L) Quantification of differentiation classes used the same criteria as in Figures 2C and 2D.

Iron Chelation Rescues Additional PLP1 Mutations in Human and Mouse Oligodendrocytes

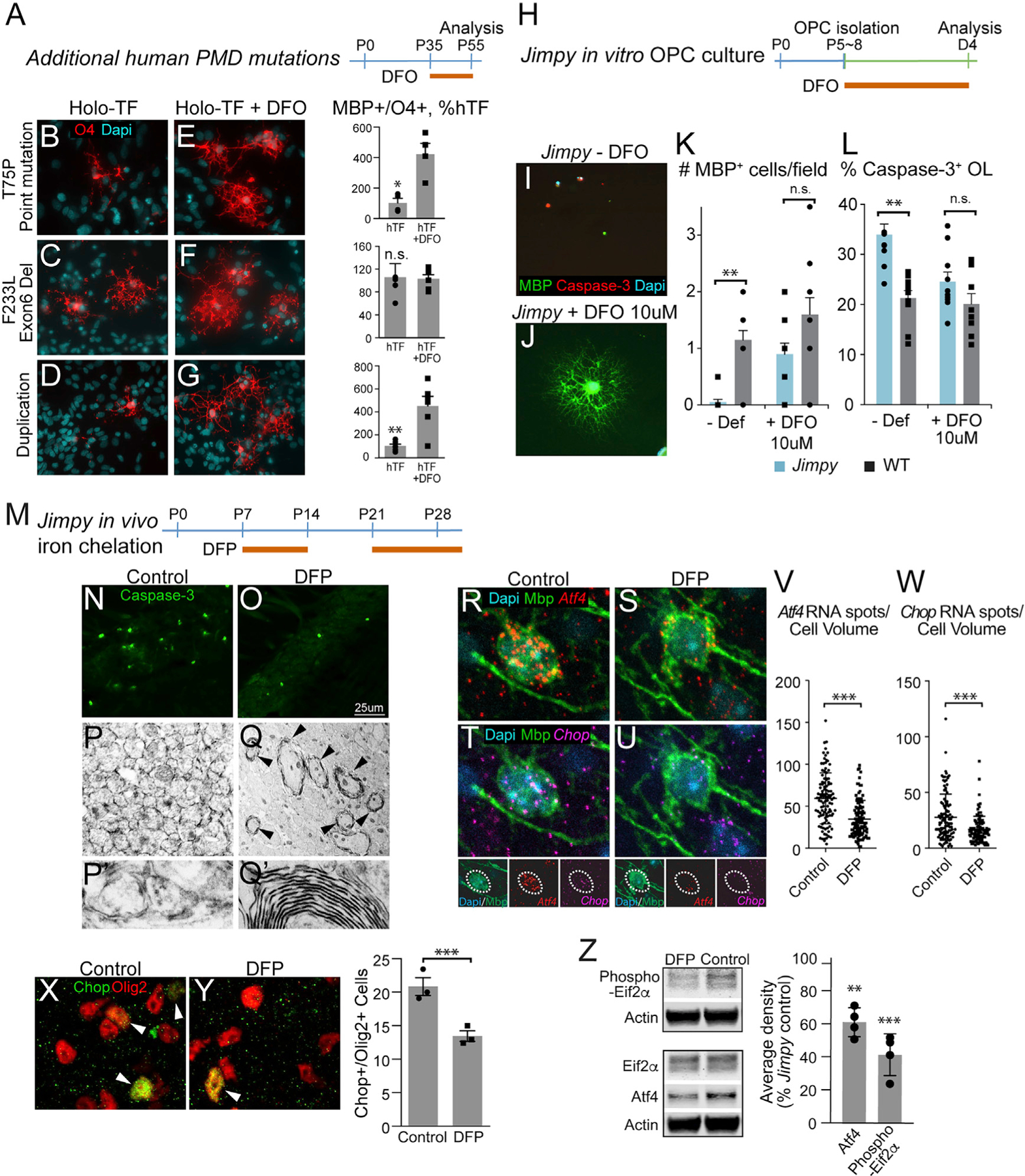

Our findings with the PLP1G74E mutation raised the question whether iron sensitivity is a more common phenomenon in other PLP1 PMD-relevant mutations. To address this question, we generated OPCs from PMD patients carrying a PLP1T75P point mutation (Gupta et al., 2012), another point mutation PL1F233L resulting in exon 6 deletion (Nevin et al., 2017), and PLP1 duplication (Nevin et al., 2017). Remarkably, the PLP1T75P point mutation and the duplication, but not the exon 6 mutations, were also rescued by the iron chelation (Figures 7A–7G). We also investigated the severe PMD Jimpy mouse model that harbors a Plp1 point mutation that affects the splicing of exon 5 (Dautigny et al., 1986; Sidman et al., 1964). While untreated mutant primary Jimpy OPCs in vitro showed inhibited differentiation block and nearly universal cell death within 24 h of growth factor withdrawal (Figures 7H, 7I, 7K, and 7L), 4-day treatment with DFO rescued both parameters to near wild-type OPC levels (Figures 7J–7L). These results demonstrate that the ferroptosis-mediated oligodendrocyte death is not restricted to the PLP1G74E mutation and extends to other PLP1 mutations. Overall, four out of five PLP1 mutations tested showed a rescue by iron chelation. Of note, ferroptosis activation is not mutually exclusive with induction of ER stress because the Jimpy and other Plp1 mutations are known to cause a severe UPR activation (Dhaunchak and Nave, 2007; Ikeda et al., 2018; Krämer-Albers et al., 2006).

Figure 7. Iron Chelation Rescues Phenotypes of Multiple PLP1 Mutations In Vitro and In Vivo.

(A) Treatment strategy to assess effects of DFO in additional human PMD mutations.

(B–G) Differentiation phenotype of additional human PMD mutations after treatment with DFO (E–G) compared to control culture condition (B–D) (n = 3–4, biological replicates). B&E, T75P point mutation; C&F, Exon6 deletion; D&G, duplication.

(H) Jimpy mouse OPCs isolated at postnatal days 5–8 were tested for differentiation phenotype and transiently treated with iron chelation.

(I–L) Jimpy OPCs (I) completely failed to differentiate upon removal of growth factors that was associated with increased cell death. Transient (4 day) DFO treatment (J) rescued both differentiation and cell death as measured by caspase-3 and MBP expression (n = 10 fields/treatment from 2 biological replicates) (K and L).

(M) In vivo iron chelation strategy in Jimpy mice. Subcutaneous injections with the brain-permeable iron chelator deferiprone (DFP) were given from postnatal days 7–14 and 21–death.

(N and O) Corpus callosum of vehicle-treated Jimpy mice (N) at postnatal day 28 showed caspase-3+ apoptotic cells compared to the DFP-treated Jimpy mice (O).

(P–Q′) Electron microscopic analysis of corpus callosum in DFP- (Q) and vehicle-treated (P) Jimpy mice showed surviving oligodendrocytes in the DFP-treated mice. Higher magnification of (P) and (Q) are depicted in (P′) and (Q′), respectively.

(R–W) Fluorescent in situ hybridization (RNA scope) showed a significant reduction in Atf4 (R, S, and V) and Chop (T, U, and W) gene expressions in Mbp+ mature oligodendrocytes after a 7-day in vivo DFP treatment from P7 in Jimpy mice (n = 3–4).

(X and Y) Immunostaining for Chop after a 7-day in vivo DFP treatment from P7 (Y) revealed a reduction in colocalization with pan-oligodendrocyte marker Olig2 (n = 3) compared to the control (X).

(Z) Western blot analysis of Jimpy brain showed significant reductions in UPR/ER stress markers Atf4 and phosphorylated Eif2a in DFP-treated Jimpy mice (n = 4).

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, n.s. = not significant. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

Systemic Treatment of Jimpy Mice with DFP Results in Enhanced Oligodendrocyte Survival and New Myelin Formation

The successful rescue of Jimpy oligodendrocytes in vitro raised the question whether iron chelation may also improve the disease progression in vivo. The Plp1 Jimpy mutation causes a very aggressive disease; mice do not show any myelin formation, develop severe seizures by postnatal week 3, and die around P28 (Dautigny et al., 1986; Sidman et al., 1964). We systemically administered a blood brain barrier-permeable iron chelator DFP to Jimpy mice from P7–P14 and P21–P28 by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections (Figure 7M). A 1-week long interruption (P14–P21) was introduced to prevent anemia (Figure S5D). As shown in Figures 7N–7Q′, DFP treatment substantially reduced levels of apoptosis in corpus callosum in Jimpy mice (45.63% ± 5.61% reduction from vehicle, t test p > 0.001), and allowed the formation of new myelin in the corpus callosum as determined by electron microscopy at P28. In addition, astrogliosis and microglia activation in the white matter were both reduced (Figure S5E). We also observed a slight improvement of overall animal survival (Figure S5C). Notably, a 7-day course of DFP treatment was sufficient to significantly reduce the UPR/ER stress markers Atf4, phosphorylated Eif2α, and Chop (Elitt et al., 2018) in Jimpy OPCs and mature oligodendrocytes in vivo (Figures 7R–7W and S5G–S5J). These findings indicate that ferroptosis-like stress also influences the UPR/ER pathway in Jimpy, a severe PMD mutation, and iron chelation substantially rescues this pathophysiology.

DISCUSSION

Our findings highlight dysregulation of iron metabolism as a significant pathobiological mechanism mediating OPC cell death in severe PMD models. We found evidence for ferroptotic as well as apoptotic cell death mechanisms in PMD oligodendrocytes. Both human and mouse PMD OPCs showed a decrease of transferrin, ferritin, iron export proteins APP and CP, and increased or unchanged IRP1/2 and transferrin receptor expression. While indicating a dysregulated iron metabolic response, the condition of PMD oligodendrocytes is distinct from classic iron overload in hemochromatosis where increased hepatic intracellular iron is associated with high ferritin and ferroportin and low levels of transferrin receptor (Recalcati et al., 2006; Siah et al., 2005). Consistent with ferroptosis, PMD oligodendrocytes exhibited lipid peroxidation and phenotypic rescue by iron chelation (Figures 5N and 5P; Dixon et al., 2012). However, we also found that apoptosis marker caspase-3 was enriched among some mutant cells and that iron chelation also normalized caspase-3 levels to control levels (Figure 5L). Similarly, we observed a reduction of ER stress and apoptosis in Jimpy oligodendrocytes rescued by DFO (Figures 7R–7W and S5G–S5J). These data suggest that the severe iron sensitivity we observed in PMD oligodendrocytes involve various cell pathogenetic mechanisms of iron-induced ferroptosis, ER stress (Feng and Stockwell, 2018), and apoptosis, and these pathways in some PMD lines are benefitted by chelation. We conclude that mechanisms of Fe-induced cell death in PMD oligodendrocyte are complex, and further studies are needed to define precise pathway interactions in a patient- and/or mutation-specific manner.

A recent publication described a drug screening platform based on cultured Jimpy oligodendrocytes and found the small molecule Ro 25–6981, an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, to enhance survival (Elitt et al., 2018). While the functional target of Ro 25–6981 was independent of an NMDA receptor, authors showed its modulatory effects on UPR signaling and subsequent increase in myelin in Jimpy mice. DFP is a FDA-approved drug for clinical use in pediatric population thus a viable treatment option for PMD. As shown in Jimpy mice, DFP significantly reduced ER stress-UPR markers, suggesting the beneficial effect of DFP in PLP1 mutations that lead to ER stress-UPR. In contrast, most ER stress-UPR inhibitors (Maly and Papa, 2014) and Ro 25–6981 are not approved for clinical use, and administration of NMDA receptor antagonist (Ro 25–6981) to infant patients whose CNS is still developing may not be ideal.

Unlike gene and cell therapeutic approaches (Gupta et al., 2012), iron chelation aims to support endogenous mutant OPC survival through the “critical window” of transition from pre-myelinating to myelinating stages. Indeed, we found that pre-transplant iron chelation was sufficient to promote survival and myelination of mutant oligodendrocytes in human slice culture and in vivo for several months post-transplantation in Shiverer mice (Figures 6A–6F). For both slice culture system and in vivo transplantation, we characterized the myelin at the limit of the culture duration (3 weeks) or at the end of the lifespan of the Shiverer hosts (~14–16 weeks) (Figures 6A–6F and 6H–6L). Up to these points, we observe myelin formation by electron microscopy (EM). This suggests that PMD oligodendrocytes are most vulnerable to iron-induced toxicity during dynamic differentiation at the onset of mutant PLP1 expression. While our findings suggest that DFP could be an appropriate therapy for selected PMD patients, it will be important to optimize drug dosage, timing for administration, and the long-term benefit to oligodendroglial survival and myelination. Evidence in the literature suggests the involvement of iron pathobiology in multiple sclerosis and neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation, (Hayflick et al., 2006; Kruer et al., 2010; Stephenson et al., 2014), which suggests our findings might have wider significance beyond PMD.

STAR★METHODS

LEAD CONTACT AND MATERIALS AVAILABILITY

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Marius Wernig (wernig@stanford.edu). Plasmids and iPS cell lines generated in this study are available upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Animals

All data shown involving animal procedures were performed according to protocols approved by the Stanford University and University of California San Francisco Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Animals were group-housed in barrier facility with 12 hour dark/light cycle. Animals received husbandry care and monitoring from veterinary and animal care staff. No animal was involved in previous procedures or drug testing. Care was taken not to disturb the animals except during cage changing, due to their seizure susceptibility. Mixed background, male and female Mbp knockout Shiverer mice (available from Jackson laboratories) crossed with immunocompromised NRG mice (available from Jackson laboratories) at postnatal day 1 were used for in vivo transplantation studies. All Shiverer mice showed tremor starting around postnatal day 12. They were seizure-prone starting around postnatal day 60. Mixed background, male Plp1 mutant Jimpy mice at postnatal day 7 to 40 (only male Jimpy mice show mutant phenotype) were revived from frozen embryos (MRC Harwell, UK). All Jimpy mice showed tremor starting around postnatal day 11. They were seizure-prone starting around postnatal day 20.

Cell lines

iPS cells from PMD patients (all males) harboring G74E and T75P mutations were generated from patient fibroblasts. All procedure was approved by UCSF Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from both patients. Patients were males 1 to 2 years of age with absence of myelination by MRI, and clinical manifestations of early-severe PMD. iPS cells from PMD patients harboring F233L and duplication mutations were received from Dr. Paul Tesar. iPS cell lines were microplasma negative. Cells were cultured in 37C humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Cell lines have not been authenticated.

Primary cell cultures

Primary oligodendrocytes from the cortex of Jimpy (males) or wild-type male littermate mice at postnatal day 5–8 were isolated by immunopanning. All data shown involving animal procedures were performed according to protocols approved by the Stanford University and University of California San Francisco Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Human primary oligodendrocytes from fetal cortical tissue (males and females of gestational weeks 20 to 23) were collected from elective pregnancy termination specimens at San Francisco General Hospital with patient consent. Cells were cultured in 37C humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

METHOD DETAILS

iPS cell generation and culture

Fibroblasts from two PMD patients (G74E and T75P mutations) enrolled in a clinical study (http://Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01005004) were obtained under approval from UCSF Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Study Protocol13–10806). All iPS cell lines were established by electroporation of a CoMiP episomal vector containing 4 reprogramming factors (OCT4, KLF4, SOX2, and c-MYC) following a published protocol (Diecke et al., 2015).

iPSCs were maintained on CF1 MEF feeder cells in ES medium containing Knockout DMEM/F12, 20% knockout serum replacement, non-essential amino acids, Glutamax (Life Technologies), and 10ng/ml human basic FGF (Thermo Fisher). Pluripotency was confirmed by expression of TRA1–60 (Cell Signaling), OCT3/4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), as well as teratoma formation and differentiation into ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm lineages. A normal karyotype was confirmed in all lines. Mycoplasma contamination has been confirmed negative in all iPSC lines.

Gene targeting

AAV plasmid and targeting vector design

5′ homologous arm (1.2kb) containing wild-type PLP1 exon 3 sequence, and 3′ homologous arm (1.3K) containing intron 3 sequence were amplified from genomic DNA of the patient’s father by PCR. A PGK promoter and neomycin resistance cassette flanked by two loxP sites was inserted between 5′ and 3′ homologous arms. The construct was cloned into pAAV packaging plasmid.

AAV was produced using a highly recombinogenic AAV-DJ AAV serotype (Melo et al., 2014) in HEK293T cells as described (Xu et al., 2012). pAAV containing wild-type PLP1 sequence, pHelper, and pRC-DJ were co-transfected and three days later, HEK293T cells were collected, suspended in benzonase buffer, and subjected to 3 rounds of freeze-thaw cycles to homogenize the cells. Homogenate was incubated with benzonase to digest DNA, spun at 5000RCF for 15min, and the supernatent containing AAV was used for iPSC infection.

iPSCs were infected by seeding 0.25 × 106 cells plated on to matrigel coated 6-well plate in NutriStem XF/FF Culture medium (Reprocell). One day after infection, medium was changed to ES cell medium and MEF feeder cells were added. Two to three days after infection, neomycin (100ug/ml) was added to the culture for approximately 1 week.

Neomycin resistant iPSC colonies presumably incorporated the targeting vector were manually picked, expanded, and checked for homologous recombination by PCR using primers designed to detect recombination junctions spanning endogenous PLP1 allele and non-endogenous neomycin resistance gene, or PGK promoter. The primer locations are depicted in pink and green arrows in Figure S2D. Following this initial PCR screen, the mutant locus was sequenced to confirm the gene correction to wild-type sequence. To exclude the possibility of multiple integrations, Southern blot analysis using a probe against neomycin resistance gene was performed. The 300bp probe template was obtained from digestion of the targeting pAAV plasmid with PSTI and SapI followed by gel extraction. The P32 labeled probe was made with Klenow labelin kit (Agilent) and purified with microspin columns (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). 10ug of genomic DNA was digested overnight with EcoRI and separated by electrophoresis. DNA was blotted on to a nylon membrane and crosslinked. The neomycin probe was incubated for 3 hours at 65° C. Following washes, signals were detected by autoradiography film (Kodak). After confirmation of a single integration of the targeting construct, the neomycin resistant gene was excised by transfecting a Cre expression plasmid containing puromycin resistant gene with FuGENE6 (Promega). Three days post transfection, puromycin (1ug/ml) was added to the medium for 2 days to select Cre expressing colonies. Resistant colonies were picked and evaluated for neomycin sensitivity and loss of neomycin sequences by genomic PCR. Complete PLP1 cDNA was sequenced to confirm intact splice sites.

OPC differentiation

A previously published protocols for directed iPSC differentiation to OPCs (Douvaras and Fossati, 2015; Wang et al., 2013) were used with the following modifications: human ES cell medium and human ES cell medium without basic FGF were used in place of mTeSR and custom mTeSR, respecitvely. The concentration of SAG was 0.5uM, T3 was 40ng/ml, NT3 was 1ng/ml. Penicillin-Streptomycin was omitted from N2 medium, HGF from PDGF medium, and HEPES from Glia medium. When apo-TF or holo-TF was used in PDGF medium and Glia medium, commercially available N2 supplement (Life Technologies) was replaced with: 6.3ng/ml progesterone, 5.2ng/ml selenite, 16.11ug/ml putrescene, 5ug/ml human insulin, and 150ug/ml human TF (either apo- or holo- form, R&D).

On day 0, iPSCs between passage 18 and 20 were plated at 0.25×106/well on a matrigel-coated 6-well plate with ES medium without basic FGF, supplemented with dual SMAD inhibitors, RA, and ROCK inhibitor thiazovivin. From day 1 to day 4, N2 medium was gradually increased by 25% each day, reaching 100% on day 4. On day 8, dual SMAD inhibitors were replaced with SAG. On day 12, cells were lifted, dissociated, and seeded on Petri dishes for sphere formation. On day 20, the medium was changed to PDGF medium. On day 30, spheres were plated on poly-L-ornithine/laminin-coated plates. On day 45, the medium was changed to Glia medium. Most differentiation assays were conducted at day 55 unless otherwise stated.

Small molecules and peptide treatments

The following drugs were added to OPC differentiation culture from day 35 to 55: apo-TF (150ug/ml), holo-TF (150ug/ml), deferoxamine (10uM), deferiprone (30uM), GSH (1mM), NAC (0.25mM), BHT (100uM), Trolox (60uM), cumene hydroperoxide (1:5000), Ammonium iron citrate (5ug/ml), Ferric citrate (15uM), Manganase chloride (15uM), Cobalt chloride (15uM), Nickel Sulfate (15uM), GSK2656157 (200nM), Kira6 (50nM).

In vivo Cell transplantation

All data shown involving animal procedures were performed according to protocols approved by the Stanford University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Initially, we transplanted unpurified neural progenitor cells at around days 60–80 of the differentiation protocol into Shiverer mice. However, the overproliferation presumably of more primitive cells complicated the analysis. We therefore purified O4+ cells at day 55 from the bulk culture by immunopanning (see method described below). 12,000 O4-immuno-panned cells/site in 0.5ul volume were transplanted in postnatal day 1 of Shiverer;Rag2−/−mice. Site of transplantation was cerebellar white matter, identified by coordinates (0.9mm medial-lateral, 3.0mm posterior,1.8mm ventral) from lambda. Animals were sacrificed by transcardiac perfusion with 4% PFA + 0.25% glutaraldehyde at 13 week post transplantation, and 50um sagittal brain sections were used for immunohistochemistry. Quantification of stained MBP and human specific marker STEM121 was done by calculating % STEM121+ cells that coloalize with MBP staining.

OPC differentiation on human slice culture

Fetal cortical tissue (gestational weeks 20 to 23) was collected from elective pregnancy termination specimens at San Francisco General Hospital with previous patient consent. Research protocols were approved by the Committee on Human Research (Institutional Review Board) at University of California, San Francisco. Human slice culture was prepared as described (Hansen et al., 2010). Cultured iPSC-derived spheres at day 40–45 were dissociated with accutase, resuspended in PDGF medium, and labeled with GFP lenti virus overnight. Cells were washed twice to remove viral particles, resuspended in approximately 6ul DMEM/F12, and plated onto human slice culture prepared a day before. A fraction of the EGFP+ cells differentiated to MBP expressing mature oligodendrocytes. Slice culture was fixed with 4% PFA for 15min, cryoprotected, and sectioned at 14um for immunohistochemistry. To quantitatively assess the degree of oligodendrocyte maturation, we classified the EGFP+/MBP+ cells into three categories based on morphological complexity (differentiated, immature, abnormal).

Jimpy in vitro OPC differentiation assay

Cortical OPCs were immunopurified from postnatal day 5–8 Jimpy or wild-type littermate mice as described (Harrington et al., 2010). After 3 days in culture with proliferation factor PDGF-AA, OPCs were directed to differentiate by removal of PDGF-AA and addition of a differentiation factor T3. Cells were fixed 24hrs after initiation of differentiation for histological analysis. Deferoxamine was added to media throughout the four-day culture at 10uM concentration.

Jimpy in vivo iron chelation treatment

Jimpy mice were subcutaneously injected with 30mg/kg deferiprone in sterile PBS, during P7 to P14 and P21 to P28 for survival study, and P7 to P14 for ER stress-UPR study. Care was taken to minimize disturbance of the mice during injection to avoid seizures. For histological assays requiring electron microscopy assay, brains were collected after cardiac perfusion with 4% PFA containing 0.25% glutaldehyde at P28 and sectioned with a vibratome. Quantification of GFAP and Iba1 was done by calculating fluorescent intensity in stained sections using Fiji software.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization

Three-color smFISH was performed on corpus collosum containing fixed frozen sections from Jimpy mice using Advanced Cell Diagnostics RNAscope® Fluorescent Multiplex Reagent Kit and probes. Briefly, cryosections (14um thick) were mounted on glass slides and washed in RNase free PBS for 5 mins and baked at 60°C for 30 mins and were further fixed in 4% neutral buffered paraformaldehyde for 15 min at 4°C. Next, sections were dehydrated in 50%, 70% and 100% ethanol for 5 mins at room temperature and air-dried. Target retrieval was then performed with RNAscope reagents for 3 mins at 95 °C and sections were further washed with distilled water followed by washes in 100% ethanol 2–3 times. After drying, sections were permeabilized with Protease IV reagent for 15 mins at 40°C, washed and maintained in RNase free water until hybridization step. Probes (Mm-Atf4 (405101), Mm-Pdgfra-C2 (480661-C2), Mm-Ddit3-C3 (317661-C3); C2 and C3 probes were diluted at 1:50 ratio in channel 1 probe) were mixed and pre-heated to 40°C for 5 mins and then added to the sections for 2hr at 40°C. After probe hybridization, sections were washed two times 2 mins each and further incubated in AMP 1-FL for 30 min at 40°C, washed two times, incubated in RNAscope AMP 2-FL for 15 min at 40°C, washed two times, incubated in RNAscope AMP 3-FL for 30 min at 40°C, washed two times and incubated in AMP 4-FL-Alt B solution for 15 mins at 40°C, washed two times and counterstained with RNAscope DAPI for 30 s. All wash steps were performed with RNAscope 1× wash buffer. Where indicated, after the RNAscope assay, the slides were blocked in 5% Horse serum/0.05% TX-100 in PBS, followed by 1 hr of MBP antibody incubation at RT, followed by three washes in PBS and secondary antibody incubation for 1hr at RT and mounted with prolong gold antifade. Quantification of RNA spots was performed on images acquired at 63× on Lecia SP5 upright AOBS confocal microscope.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated at described time points with Trizol reagent (Life Technologies) or RNAeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) following manufacturer’s protocols. Contaminating DNA was removed with TURBO DNA-free kit (Life Technologies). cDNA was obtained with High-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Life Technologies). SYBR green-based qPCR was conducted in LightCycler 480 with manufacturer’s reagents (Roche) with the primer sets indicated in the key resources table. See Table S1 for primer sequences.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Olig12 | Courtesy of Charles Stiles | N/A |

| NKX2.2 | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank | Cat# 74.5A5 |

| SOX1 | R&D | Cat# AF3369 |

| PAX6 | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank | Cat# Pax6 |

| O4 | Mouse Hybridoma | N/A |

| PLP1 | Abcam | Cat# 28486 |

| Tra1-60 | Cell Signaling | 4746T |

| Oct3/4 | Santa Cruz | sc-5279 |

| MBP | AbD Serotec | Cat# MCA409S |

| Cleaved Caspase-3 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 9664S |

| KDEL | Abcam | Cat# ab50601 |

| GFP | Aveslab | Cat# GFP-1020 |

| Human cytoplasmic marker | Clontech | Cat# STEM121 |

| NeuN | EMD Millipore | Cat# MAB377 |

| PDGFRα | BD Bioscience | Cat# 556001 |

| Transferrin | Abcam | Cat# ab137744 |

| Ferritin | Novus Biologicals | Cat# NB600-920 |

| IRP1 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 20272 |

| IRP2 | Cell Signaling | Cat# 37135S |

| Transferrin receptor | BD Bioscience | Cat# 561939 |

| Ferroportin | Novus Biologicals | Cat# NBP1-21502 |

| beta Actin | Sigma | Cat# A5441 |

| GFAP | Fisher | Cat# 13-0300 |

| Iba1 | Wako | Cat# 019-19741 |

| EIf2α | Cell Signaling | Cat# 9722 |

| Phospho-EIf2α | Fisher | Cat# MA5-15133 |

| ATF4 | Aviva Systems Biology | Cat# ARP37017 |

| CHOP | Fisher | Cat# MA1-250 |

| O4-APC | Miltenyi Biotec Inc | 130-099-211 |

| TFRC-GFP | BD Biosciences | 561939 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| AAV serotype DJ | This paper | Melo et al., 2014 |

| Lenti-GFP | Addgene | Tet-O-FUW-EGFP |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Dermal fibroblasts from PMD patients | This paper | N/A |

| Human brain tissues from fetal gestational week 20 to 23 | This paper | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| T3 | Sigma | Cat# T6397 |

| SB431542 | Tocris | Cat# 1614 |

| LDN193189 | Stemgent | Cat# 04-0074 |

| SAG | Shenzhen Shengjie Chemical | Cat# 912545-86-9 |

| Thiazovivin | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc-361380 |

| basic FGF | Thermo Fisher | Cat# PHG0024 |

| PDGF-A | Peprotech | Cat# 100-13A |

| IGF | Peprotech | Cat# 100-11 |

| NT3 | Peprotech | Cat# 450-03 |

| Human apo-transferrin | R&D | Cat# 3188-AT-100MG |

| Human holo-transferrin | R&D | Cat# 2914-HT-100MG |

| Deferoxamine | Sigma | D9533 |

| Deferiprone | Sigma | 379409 |

| GSH | Sigma | G4251 |

| NAC | Sigma | A9165 |

| BHT | Sigma | 47168 |

| Trolox | Sigma | 238813 |

| Cumene hydroperoxide | Life Technologies | C10446 |

| Ammonium iron citrate | Sigma | F5879 |

| Ferric citrate | Sigma | F3388 |

| Manganase chloride | Sigma | M8054 |

| Cobalt chloride | Sigma | 255599 |

| Nickel Sulfate | Sigma | 227676 |

| GSK2656157 | EMD Millipore | 5046510001 |

| Kira6 | Courtesy of Papa lab, UCSF | N/A |

| NutriStem Xf/FF culture medium | Reprocell | 01-0005 |

| Bandeiraea Simplicifolia Lectin I | Vector Laboratories | L1100 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| CellROX® ROS sensor | Thermo Fisher | Cat# C10444 |

| Click-iT Lipid Peroxidation Imaging Kit | Thermo Fisher | Cat# C10446 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| iPS cells from PMD patients | This paper | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse (Mbp knockout Shiverer) | Jackson laboratories | Mpbshi |

| Mouse (Immunocompromized) | Jackson laboratories | NRG, NOD-Rag1null IL2rgnull, NOD rag gamma |

| Mouse (Plp1 mutant Jimpy) | MRC Harwell | Plp1 < jp > |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Table S1 for qPCR primer sequences. | N/A | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| CoMiP episomal vector containing reprogramming factors OCT4, KLF4, SOX2, and c-MYC | Diecke et al., 2015 | N/A |

| AAV plasmid containing PLP1 gene | This paper | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Simple Neurite Tracer | Fiji plugin software | N/A |

Electron Microscopy

Animals were cardiacly perfused with 4% PFA containing 0.25% glutaldehyde. Alternative vibratome sections were kept for immunohistochemistry and EM, which were post-fixed in 4% glutaraldehyde for several days. Regions of interest determined by immunohistochemistry were micro-dissected, fixed in 2% osmium tetroxide and embedded in resin. Ultrathin sections were placed onto copper grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead, and examined with a Hitachi H-600 or TEM 1400 Transmission Electron Microscopes. Use of TEM 1400 was supported by NIH grant SIG number 1S10RR02678001.

Flow Cytometry

The bulk culture was detached using Accutase, dissociated, rinsed, and resuspended in PBS containing1% BSA. Cells were incubated with O4-APC and TFRC-GFP for 10min at room temperature. Following a wash with PBS, cells were suspended in PBS containing 5mM EDTA and analyzed with FACSAria II Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences) and FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Dead cells were excluded by Dapi staining.

Morphological complexity assessment

Cultures at described days were live-stained with O4 antibody for 30min, followed by Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody for 30min. After fixation, images were taken at 40X magnification in Leica microscope equipped with CCD camera. Individual cell morphology was reconstructed by tracing the O4 stained branches assisted by a Fiji plugin software Simple Neurite Tracer (Frangi et al., 1998). Traced images were analyzed with Sholl analysis software (Fiji) (Ferreira et al., 2014). Ramification index, which integrates the number of branches from soma and number of intersections, as well as the total length of traced line were presented in results.

Reactive oxygen species assessment

General ROS assessment: After live O4 staining to identify OPCs, the CellROX® ROS sensor (Thermo Fisher) was used at 1:500 dilution of the ROX reagent following manufacturer’s protocol, with a following modification: incubation with ROX reagent was increased to 60min.

Lipid ROS assessment

Click-iT® Lipid Peroxidation Detection with Linoleamide Alkyne (LAA) (Thermo Fisher) was used following manufacturer’s protocol with the following modifications: LAA stock solution was added to the culture at 10uM concentration from day 49 to 55 every other day. On day 55, cultures were live-stained with O4 first, then manufacturer’s LAA detection protocol was followed. Quantification of LAA+ cells was conducted under Leica microscope equipped with CCD camera within 2 days of detection.

Western blot analysis

Isolated 50,000 O4+ oligodendrocytes were pelleted and snap frozen until analysis. Cell pellet was homogenized in lysis buffer, separated by electrophoresis following manufacturer’s protocol (Bolt Mini gel, Thermo Fisher), transferred, and incubated with primary antibodies overnight. Proteins were visualized using Li-Cor western blot detection system.

Isolation of human primary OPCs

Fetal brain tissues described in the human slice culture section was dissociated with papain for 10min. Single cell suspension was passed onto series of culture dishes coated with BSL (Bandeiraea Simplicifolia Lectin I) to remove microglia and endothelial cells, IgM secondary antibody to avoid non-specific binding, and O4, to isolate O4+ OPCs. At the end of O4 binding, adherent cells were washed, and detached with Trypsin, and collected by centrifugation. Cells were directly homogenized in Trizol for RNA collection.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Each in vitro experiment was repeated at least three times. Number of biological replicates included in each experiment can be found in figure legends. Number of mice used in in vivo experiments can be found in figure legends. For statistical analysis, two-sided one way ANOVA and t test with normal distribution, log-rank survival test, or one way Chi-square tests were used as appropriate. * indicates p value < 0.05, ** p value < 0.01, *** p value < 0.001, n.s. = not significant. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. No data point was excluded from analyses unless animal’s early death due to seizure, or culture contamination occurred.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

This study did not generate/analyze datasets or codes. Original data for figures in this study are available through the Lead Contact, M. Wernig.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

PLP1 mutations in Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease cause iron-induced oligodendrocyte death

Gene correction in patient-derived iPSCs rescues PLP1 mutant oligodendrocyte cell death

Iron chelators and lipophilic antioxidants rescue mutant oligodendrocyte cell death

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Daniel Morrison for assistance in electron microscopy, Nobuko Uchida for the human-specific STEM121 antibody, Brian Popko for advice on the manuscript, and Hideyuki Okano for human PMD iPSC lines. Members of the Wernig and Rowitch laboratories provided advice on experimental design and the manuscript. H.N. acknowledges postdoctoral fellowship support from the European Leukodystrophy Association and career transition fellowship support from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. M.C. acknowledges funding support from Career Development Grant awarded by Cerebral Palsy Alliance Research Foundation Inc. This work was supported by funding from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (to M.W. and D.R.), the European Leukodystrophy Association, the New York Stem Cell Foundation (to M.W.), Action Medical Research, the Adelson Medical Research Foundation, the National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, and the European Research Council (to D.R.). M.W. was a Tashia and John Morgridge Faculty Scholar at the Child Health Research Institute at Stanford.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2019.09.003.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Back SA, Gan X, Li Y, Rosenberg PA, and Volpe JJ (1998). Maturation-dependent vulnerability of oligodendrocytes to oxidative stress-induced death caused by glutathione depletion. J. Neurosci 18, 6241–6253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brissot P, and Loréal O (2016). Iron metabolism and related genetic diseases: A cleared land, keeping mysteries. J. Hepatol 64, 505–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts BD, Houde C, and Mehmet H (2008). Maturation-dependent sensitivity of oligodendrocyte lineage cells to apoptosis: implications for normal development and disease. Cell Death Differ. 15, 1178–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dautigny A, Mattei MG, Morello D, Alliel PM, Pham-Dinh D, Amar L, Arnaud D, Simon D, Mattei JF, Guenet JL, et al. (1986). The structural gene coding for myelin-associated proteolipid protein is mutated in jimpy mice. Nature 321, 867–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaunchak AS, and Nave KA (2007). A common mechanism of PLP/DM20 misfolding causes cysteine-mediated endoplasmic reticulum retention in oligodendrocytes and Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 17813–17818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diecke S, Lu J, Lee J, Termglinchan V, Kooreman NG, Burridge PW, Ebert AD, Churko JM, Sharma A, Kay MA, and Wu JC (2015). Novel codon-optimized mini-intronic plasmid for efficient, inexpensive, and xeno-free induction of pluripotency. Sci. Rep 5, 8081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, et al. (2012). Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149, 1060–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douvaras P, and Fossati V (2015). Generation and isolation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc 10, 1143–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elitt MS, Shick HE, Madhavan M, Allan KC, Clayton BLL, Weng C, Miller TE, Factor DC, Barbar L, Nawash BS, et al. (2018). Chemical Screening Identifies Enhancers of Mutant Oligodendrocyte Survival and Unmasks a Distinct Pathological Phase in Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease. Stem Cell Reports 11, 711–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa de los Monteros A, Kumar S, Zhao P, Huang CJ, Nazarian R, Pan T, Scully S, Chang R, and de Vellis J (1999). Transferrin is an essential factor for myelination. Neurochem. Res 24, 235–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H, and Stockwell BR (2018). Unsolved mysteries: How does lipid peroxidation cause ferroptosis? PLoS Biol. 16, e2006203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira TA, Blackman AV, Oyrer J, Jayabal S, Chung AJ, Watt AJ, Sjöström PJ, and van Meyel DJ (2014). Neuronal morphometry directly from bitmap images. Nat. Methods 11, 982–984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangi F, Niessen WJ, Vinc KL, and Viergever MA (1998). Multiscale vessel enhancement filtering. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. Comput. Sci 1946, 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N, Henry RG, Strober J, Kang SM, Lim DA, Bucci M, Caverzasi E, Gaetano L, Mandelli ML, Ryan T, et al. (2012). Neural stem cell engraftment and myelination in the human brain. Sci. Transl. Med 4, 155ra137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen DV, Lui JH, Parker PR, and Kriegstein AR (2010). Neurogenic radial glia in the outer subventricular zone of human neocortex. Nature 464, 554–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington EP, Zhao C, Fancy SP, Kaing S, Franklin RJ, and Rowitch DH (2010). Oligodendrocyte PTEN is required for myelin and axonal integrity, not remyelination. Ann. Neurol 68, 703–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick SJ, Hartman M, Coryell J, Gitschier J, and Rowley H (2006). Brain MRI in neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation with and without PANK2 mutations. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol 27, 1230–1233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, and Camaschella C (2010). Two to tango: regulation of Mammalian iron metabolism. Cell 142, 24–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson GM, and Kamholz J (1999). PLP1-Related Disorders. In GeneReviews, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, and Pagon RA, et al. , eds. (Seattle: University of Washington; ). [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Hossain MI, Zhou L, Horie M, Ikenaka K, Horii A, and Takebayashi H (2018). Histological detection of dynamic glial responses in the dysmyelinating Tabby-jimpy mutant brain. Anat. Sci. Int 93, 119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorchid A, Fragoso G, Shore G, and Almazan G (2002). Catecholamine-induced oligodendrocyte cell death in culture is developmentally regulated and involves free radical generation and differential activation of caspase-3. Glia 40, 283–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krämer-Albers EM, Gehrig-Burger K, Thiele C, Trotter J, and Nave KA (2006). Perturbed interactions of mutant proteolipid protein/DM20 with cholesterol and lipid rafts in oligodendroglia: implications for dysmyelination in spastic paraplegia. J. Neurosci 26, 11743–11752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruer MC, Paisán-Ruiz C, Boddaert N, Yoon MY, Hama H, Gregory A, Malandrini A, Woltjer RL, Munnich A, Gobin S, et al. (2010). Defective FA2H leads to a novel form of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA). Ann. Neurol 68, 611–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner DF, and Connor JR (2012). Functional roles of transferrin in the brain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1820, 393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly DJ, and Papa FR (2014). Druggable sensors of the unfolded protein response. Nat. Chem. Biol 10, 892–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo SP, Lisowski L, Bashkirova E, Zhen HH, Chu K, Keene DR, Marinkovich MP, Kay MA, and Oro AE (2014). Somatic correction of junctional epidermolysis bullosa by a highly recombinogenic AAV variant. Mol. Ther 22, 725–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naguib YM (1998). A fluorometric method for measurement of peroxyl radical scavenging activities of lipophilic antioxidants. Anal. Biochem 265, 290–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevin ZS, Factor DC, Karl RT, Douvaras P, Laukka J, Windrem MS, Goldman SA, Fossati V, Hobson GM, and Tesar PJ (2017). Modeling the Mutational and Phenotypic Landscapes of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease with Human iPSC-Derived Oligodendrocytes. Am. J. Hum. Genet 100, 617–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numasawa-Kuroiwa Y, Okada Y, Shibata S, Kishi N, Akamatsu W, Shoji M, Nakanishi A, Oyama M, Osaka H, Inoue K, et al. (2014). Involvement of ER stress in dysmyelination of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher Disease with PLP1 missense mutations shown by iPSC-derived oligodendrocytes. Stem Cell Reports 2, 648–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recalcati S, Alberghini A, Campanella A, Gianelli U, De Camilli E, Conte D, and Cairo G (2006). Iron regulatory proteins 1 and 2 in human monocytes, macrophages and duodenum: expression and regulation in hereditary hemochromatosis and iron deficiency. Haematologica 91, 303–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach A, Boylan K, Horvath S, Prusiner SB, and Hood LE (1983). Characterization of cloned cDNA representing rat myelin basic protein: absence of expression in brain of shiverer mutant mice. Cell 34, 799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siah CW, Trinder D, and Olynyk JK (2005). Iron overload. Clin. Chim. Acta 358, 24–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidman RL, Dickie MM, and Appel SH (1964). Mutant Mice (Quaking and Jimpy) with Deficient Myelination in the Central Nervous System. Science 144, 309–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sistermans EA, de Wijs IJ, de Coo RF, Smit LM, Menko FH, and van Oost BA (1996). A (G-to-A) mutation in the initiation codon of the proteolipid protein gene causing a relatively mild form of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease in a Dutch family. Hum. Genet 97, 337–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwood CM, Garbern J, Jiang W, and Gow A (2002). The unfolded protein response modulates disease severity in Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Neuron 36, 585–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson E, Nathoo N, Mahjoub Y, Dunn JF, and Yong VW (2014). Iron in multiple sclerosis: roles in neurodegeneration and repair. Nat. Rev. Neurol 10, 459–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Bates J, Li X, Schanz S, Chandler-Militello D, Levine C, Maherali N, Studer L, Hochedlinger K, Windrem M, and Goldman SA (2013). Human iPSC-derived oligodendrocyte progenitor cells can myelinate and rescue a mouse model of congenital hypomyelination. Cell Stem Cell 12, 252–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward KJ (2008). The molecular and cellular defects underlying Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Expert Rev. Mol. Med 10, e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Morishita W, Buckmaster PS, Pang ZP, Malenka RC, and Südhof TC (2012). Distinct neuronal coding schemes in memory revealed by selective erasure of fast synchronous synaptic transmission. Neuron 73, 990–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chen K, Sloan SA, Bennett ML, Scholze AR, O’Keeffe S, Phatnani HP, Guarnieri P, Caneda C, Ruderisch N, et al. (2014). An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci 34, 11929–11947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate/analyze datasets or codes. Original data for figures in this study are available through the Lead Contact, M. Wernig.