Abstract

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a rare condition, mostly due to genetic deficiency of complement C1 inhibitor (C1-INH). The rarity of HAE impedes extensive data collection and assessment of the impact of certain factors known to affect the course of this disabling and life-threatening disease. Establishing a global registry could assist to overcome such issues and provides valuable patient data from different countries. The HAE Global Registry is a disease-specific registry, with web-based electronic support, where data are provided by physicians and patients through a dedicated application. We collected data between January 1, 2018, and August 31, 2020. Data on 1297 patients from 29 centers in 5 European countries were collected. At least one attack was recorded for 497 patients during the study period. Overall, 1182 patients were diagnosed with HAE type 1 and 115 with type 2. At the time of database lock, 389 patients were taking long-term prophylactic medication, 217 of which were on danazol. Most recorded attacks affected the abdomen, were generally moderate in severity, and occurred in patients who were not on prophylactic treatment (70.6%, 6244/8848). The median duration of attacks was 780 min (IQR 290–1740) in patients on prophylactic medication and 780 min (IQR 300–1920) in patients not on continuous prophylactic medication. In conclusion, the establishment of a registry for C1-INH-HAE allowed collection of a large amount of data that may help to better understand the clinical characteristics of this disease. This information may enhance patient care and guide future therapeutic decisions.

Keywords: Hereditary angioedema, Global, Registry, Database, Attacks, C1-inhibitor, Prophylaxis

Introduction

Angioedema is a localized, self-limiting swelling of the extremities, face, genitals, gastrointestinal tract, and upper airway mucosa. Although it is a common symptom of allergic reactions or chronic urticaria (generally with wheals), patients rarely have angioedema in the absence of wheals. In these cases, angioedema can be acquired or hereditary. A consensus meeting held in 2012 gave the first classification of angioedema without wheals [1]. Hereditary angioedema due to C1-inhibitor deficiency (C1-INH-HAE) is the best-characterized and most common form of HAE. Although this rare disease is still underdiagnosed, the estimated prevalence reported in the literature is 1:50,000 [2]. C1-INH-HAE has a well-defined pathogenetic mechanism and several approved therapies [3].

Despite these achievements, the lack of aggregated data makes the epidemiologic aspects vague. We do not know whether C1-INH-HAE patients have specific comorbidities compared with those in the general population. C1-INH-HAE is characterized by different clinical phenotypes [4], but we cannot stratify patients based on their phenotype because the frequency, duration, and severity of angioedema symptoms have not been prospectively collected in a large population under strict, predefined criteria. Disease registries were created to address these needs.

The use of registries started in the 1930s in the UK and USA as a means to systematically collect data on cancer patients [5]. A patient registry is defined as an organized system that collects, analyzes, and disseminates the data and information on a group of people defined by a particular disease, condition, exposure, or health-related service, and that serves a predetermined scientific, clinical, or/and public health (policy) purpose [6]. Depending on the main inclusion criteria, registries are categorized as disease or condition registries, product registries, and health services registries. Product registries for C1-INH-HAE were developed as part of post-marketing surveillance for newly approved treatments [7, 8]. Some of these registries also aim to capture epidemiological data on disease course, but with the recruitment bias of being treatment-oriented [9, 10]. Country-based databases and registries also exist but have limitations in the number of entries and recruited patients [11–13]. An attempt to create a European registry started in 2002 but could not be maintained [14]. Here, we present the design and initial data from the first Hereditary Angioedema Global Registry (HGR).

The objective of this international multicenter disease registry is to gather homogeneous laboratory and clinical data on patients with hereditary angioedema and to evaluate therapeutic options to manage this disease. The competent board (Comitato Etico Indipendente Milano Area A, Registro Sperimentazioni n. 2015/ST/253) of the coordinating center in Milan approved the registry protocol as an investigator-initiated observational study in 2016 and the amended version on February 27, 2017.

Materials and Methods

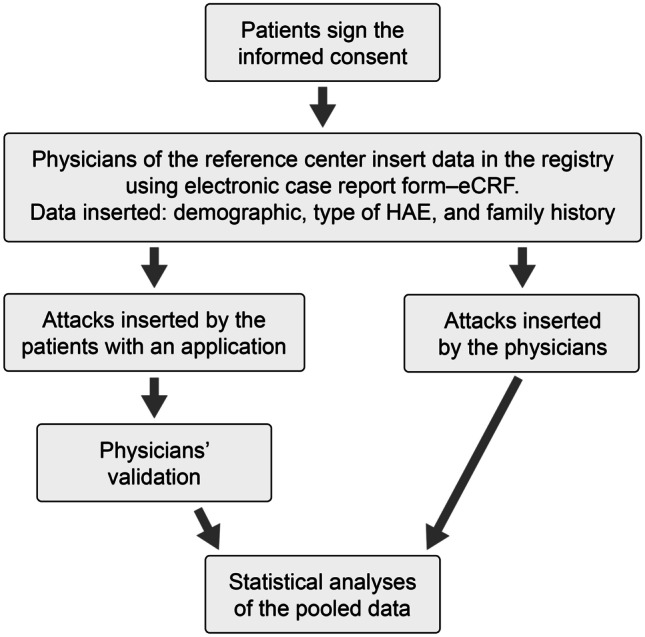

The principal investigator at each center was responsible for obtaining a competent ethics committee/institutional review board approval. Each of them identified other co-investigators who collect patients’ informed consent and insert their data in the registry. Upon acceptance of the informed consent, the treating physician transferred data of the case report form (CRF) to a specifically designed electronic form (eCRF). Physicians filled the eCRF with data about the center and record the entry in the registry. Data included demographics; contact details; date and age of diagnosis; type of HAE; levels of functional and antigenic C1-INH, C4, C1q, and anti-C1-INH antibodies; and family history of HAE. Data on SERPING1 gene transcript, protein mutations, comorbidities, long-term prophylaxis, follow-up, and attacks was also entered. The SERPING1 genotype was labeled according to the last HUGO nomenclature [15]. Conversion from other nomenclatures was obtained by direct connection with the Mutalyzer software [16]. In addition to signing a specific informed consent, patients consented to long-term storage of biological material (plasma and DNA) for research purposes. Only protocol-related data were collected. To normalize differences in reference values, diagnostic parameters were transformed into a percentage of normal by a converter.

When eCRF for a specific patient has been built, the patient him/herself could directly provide data on angioedema (AE) attacks (i.e., duration, severity, and treatment of each angioedema episode) either on paper, using a web form, or by a mobile application (App). These data were directed to a staging area for physician validation before being considered amenable for statistics (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart explaining how the registry works

While the registry contained some retrospective historical values, such as laboratory data, age at diagnosis, all real-time data on the attacks was collected prospectively. Therefore, this study can be considered primarily a prospective cohort study.

The registry governance was approved during the first HGR Conference held in Bucharest, on April 13, 2018. An independent non-profit foundation (HGRF), made of representatives of patients’ associations, was in charge of funding and delegated all the management to the HAE Global Registry Board (HGRB). The HGRB oversees operational tasks, assisted by the HAE Global Registry Scientific Committee (HGRSC) which supervises issues of competence. No registry member, center, group, or board could access the entire set of data. All registry members, as single or group, could propose new studies based on the aggregated data, by addressing their request to the HGRSC. Analysis and studies based on data obtained at local centers was allowed at any time. Members of the HGRB and HGRSC were elected to be representatives of different cultural and geographic backgrounds. Their offices have a 2-year term with no more than one consecutive renewal. Angioedema centers could join the registry upon request from the HGRB. The registry quality-control system periodically checks registry entries and compliance of eCRF with the source data. For each dataset, the system could trace the time and author.

We collected data on living C1-INH-HAE type 1 or type 2 patients from all participating centers. The diagnosis of C1-INH-HAE type 1 and 2 was based on the following criteria: C1-INH-HAE type I was diagnosed when functional and antigenic C1-INH were ≤ 50% of normal, and type II when functional C1-INH was ≤ 50% and antigenic C1-INH was > 50% of normal. Normal values were 70–130% for functional C1-INH, 70–115% for antigenic C1-INH, and 60–140% for antigenic C4.

The following patients’ data were included in this study: number of patients per center, age, gender, HAE diagnosis, number of patients recording at least one attack, the tool used for recording the attacks, and the number of recorded patients during the study period. In addition, the distribution of patients taking long-term prophylactic medication according to the type of prophylaxis, gender, and age was extracted, using the ongoing situation at the time of database lock, that is, on August 31, 2020.

Data on valid attacks occurring from January 1, 2018, to August 31, 2020 were included in this analysis. We recorded the total valid attacks, attack location, severity, duration, and the use of prophylactic treatment. We assessed the severity of attacks, according to their interference with activities of daily living, as: ‘mild’ if no interferences were experienced, ‘moderate’ in case of partial interference, and ‘severe’ for complete incapacity.

Results

Patients

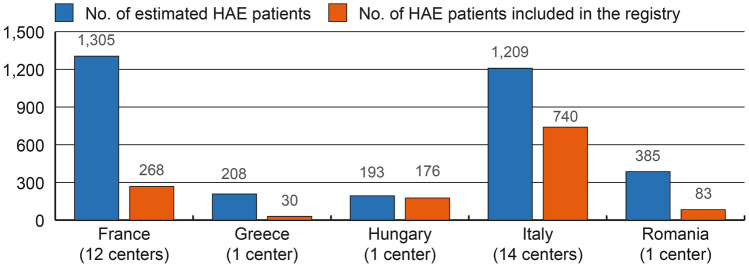

At the end of the analyzed 32-month period, the total number of living patients in the registry was 1297, from 29 centers, most of which (> 50%) were from Italy (Fig. 2). It is interesting to note that the Hungarian center encompassed almost the entire Hungarian estimated patient population.

Fig. 2.

Total number of estimated HAE patients and number of HAE patients recorded in the registry. The estimations of the total affected population were based on 1:50,000 rate [2] to the most updated population data in each country [17]

The registry’s patient disposition is presented in Table 1. Approximately 12% of the recorded patients were under age 18. The number of females is slightly higher than males (56%). The most represented type of HAE is type 1, accounting for 91% of patients. The median age at diagnosis was 23 years, but some were not diagnosed until the age of 80.

Table 1.

Data recorded in the registry in the period of the study

| Charachteristics | N (%; median; range; IQR [years of age]) |

|---|---|

| Pediatrica patients | 140 (11%; 11; 2-17; 8-14) |

| Adultb patients | 1,157 (89%;46; 18-92; 32-59) |

| Gender | N (%) |

| Males | 569 (44%) |

| Females | 728 (56%) |

| Type of C1-INH-HAE | N (%) |

| Type 1 | 1,182 (91%) |

| Type 2 | 115 (9%) |

| Age at diagnosis (n=1295) | (mean; median; range; IQR) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | (25; 23; 0-80; 10-36) |

| No. of patients inserted attacks during the study period | |

| Patients with ≥1 attack | 497 |

| Attack inserted by the app | 359 |

| Attack inserted by a physician | 138 |

| No. of patients recorded during the study period | |

| Up to January 2018 | 440 |

| Up to January 2019 | 790 |

| Up to January 2020 | 1,129 |

a<18 years of age, b≥18 years of age, IQR = interquartile range

Of the entire patient population in the registry, 829 (64%) were holding an account enabling them to register attack characteristics by themselves. Among those who had the account and recorded at least one attack (n = 410), 86% registered the attack by themselves, while 14% of attacks were recorded by physicians.

From the beginning to the end of the analysis period, the number of recorded patients has almost tripled. Overall, less than 50% of patients in the database had at least one recorded attack. The growth rate of the database is depicted in Table 1. Laboratory data at diagnosis, when available, is reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Laboratory data at diagnosis in HAE type 1 (n=1,182) and 2 (n=115)

| Parameter | C1-INH-HAE type 1 (mean; median; IQR) | C1-INH-HAE type 2 (mean; median; IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| C4 (% of normala) | 18; 15; 1–26 | 19; 18; 3–26 |

| Antigenic C1-INH (% of normalb) | 20; 20; 9–26 | 107; 108; 53–156 |

| C1-INH function (% of normalc) | 20; 17; 2–30 | 20; 18; 9–30 |

a60 to 140%, b70 to 115%, c70 to 130%

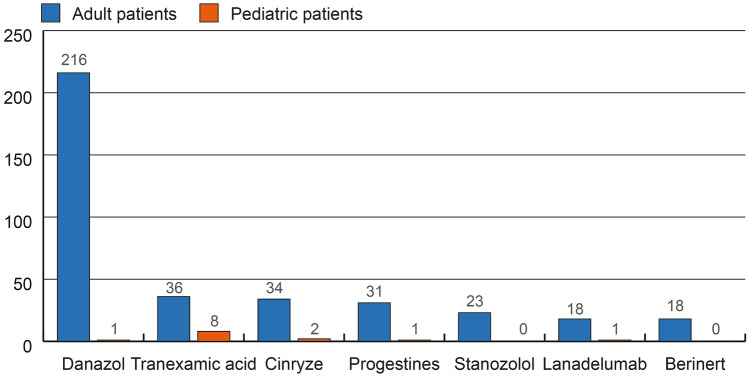

Until the data-cut on the 31st of August 2020, 389 patients were taking long-term prophylactic medication, of the majority were using attenuated androgens like danazol (Fig. 3), which was also administered in a high percentage of female patients (45%, Table 3). Interestingly, 40 out of 240 (17%) patients taking androgens (danazol or stanozolol) at the database lock have started using it during the study period.

Fig. 3.

Adult and pediatric patients taking long-term prophylaxis (LTP) at the time of database lock. Pediatric patients were < 18 years of age. Adult patients were ≥ 18 years of age, Berinert: I.V. and S.C. are considered off-label

Table 3.

Drugs taken for long-term prophylaxis (LTP)

| Drugs | Total | Pediatric patientsa | Adult patientsb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | M | F | ||

| Danazol | 217 | 0 | 1 | 118 | 98 |

| Tranexamic acid | 44 | 6 | 2 | 11 | 25 |

| Cinryze | 36 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 26 |

| Progestines | 32 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 31 |

| Stanozolol | 23 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 19 |

| Lanadelumab | 19 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 9 |

| Berinertc | 18 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 16 |

| Total | 389 | 8 | 5 | 152 | 224 |

a<18 years of age, b≥18 years of age, cI.V. and S.C. Off-label use

Recorded Angioedema Attacks

In the period considered, the total validated attacks were 8848, attributable to 497 patients (Table 4). Most attacks (71%) occurred in patients not on prophylactic medication. The most frequently affected sites were the abdominal area and the skin. The severity of attacks was considered moderate, and attack duration was similar in patients with and without prophylaxis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Location, severity, and duration of attacks in the period considered.

| Attacks with prophylaxis (n=2641) | Attacks without prophylaxis (n=6244) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sitea | ||

| Cutaneous neck/face | 185 (6%) | 404 (6%) |

| Abdominal | 1277 (40%) | 3017 (42%) |

| Cutaneous others | 1279 (40%) | 2759 (38%) |

| Oral cavity/larynx | 82 (3%) | 202 (3%) |

| Other sites (including genital attacks) | 368 (12%) | 867 (12%) |

| Severity | ||

| Mild | 759 (29%) | 1568 (25%) |

| Moderate | 1333 (50%) | 3206 (51%) |

| Severe | 549 (21%) | 1470 (24%) |

| Duration | ||

| Time in minutes (median; IQR [min])b | 780; 290–1740 | 780; 300–1920 |

Some attacks affected more than one site, valid attacks in the period (01 Jan 2018<= Start Date<=31 Aug 2020) attack duration < 12 days (22 records were excluded because attack duration was >12 days). Percentages represent the proportions within the same category (i.e., with prophylaxis/without prophylaxis)

Discussion

A global registry for HAE permits collection of valuable data from many patients affected by this rare disease across countries and cultures. The implementation of this registry was possible thanks to the first initiative of the Italian Network for C1-INH-HAE (ITACA) established in 2012, which in 2018 decided to expand its data collection framework to other European countries: Greece, Hungary, France, Romania [18]. The first attempt to form an European HAE registry was in 2002, involving centers from Italy, Germany, Hungary, Denmark, France, Spain, the UK, Norway, Poland, and Switzerland [14]. However, this enterprise was not maintained for many reasons. Other similar registries, involving patients with HAE, were also attempted. For example, a product registry for patients using Berinert (pdC1-INH, CSL-Behring) was created and reported in 2016 [8]. In addition, country-based registries also collected patient data. In Greece, Psarros et al. were able to gather data and report on 116 patients [11]. However, data collected by the Greek registry was in an eCRF form but were not monitoring the progression of attacks and changes in drug treatment. The Spanish registry, reported by Roche and colleagues [13], also recorded long-term prophylaxis (LTP), highlighting a high prevalence of attenuated androgen use. However, it is worth noting that this report was published in 2005 when drug options were limited. In the meantime, global experience (i.e., Canada, Brazil, International guidelines) has been published [19, 20].

Type of HAE

The proportion of patients affected by C1-INH-HAE type 1 and type 2 enrolled in this study was 91% and 9%, respectively, which is in-line with data reported by others in the literature [2, 21]. In comparison, nationwide surveys carried out in Italy [2] and Denmark [21] found prevalence of C1-INH-HAE type 1 of 87% and 94%, respectively.

Attack Location

The most common site of attack in this study was the abdomen. A survey carried out in Spain, Germany, and Denmark [22] also reported that the abdominal area (or intestinal involvement) was the most common site of attack.

Long-Term Prophylaxis

In this study, 30% of patients were maintained on LTP at the database lock. Bygum and colleagues, in a Danish nationwide survey, found a similar proportion (29%) [21]. It is worth noting that the most commonly used drug for LTP was attenuated androgens. These drugs have some advantages, such as low price and easy (oral) administration, but this is at a cost of many adverse effects [23]. In recent years, new targeted drugs carrying a lower risk of adverse effects have been approved as LTP for C1-INH-HAE. In this database, most patients treated with danazol and stanozolol began their prophylaxis therapy many years ago, and only 17% started using it during the study period.

Duration of Attacks

The duration of attacks with or without prophylaxis was similar. This might be due to the fact that patients with severe disease preferred to use prophylaxis because it shortens the duration of attacks, or due to the fact that patients without prophylaxis promptly treated acute attacks with on-demand therapy.

Real-Time Recording

Among the other advantages of this specific registry is an easy-to-use application (App) in the smartphones of the patients. This enables a prompt recording of the characteristics of the attack and alerts physicians about self-treatment. This way, the patients may timely observe the efficacy of on-demand treatment, disease severity, and the need for starting prophylaxis or switching to another drug. Among the other advantages, the registry could capture data about a switch in prophylactic treatment and monitor the use of new drugs. It should be noted that the recent market entry of the anti-kallikrein monoclonal antibody lanadelumab [24, 25], the data about its use is represented only in the last year of the study period.

Limitations

This registry also has some limitations. First, the completeness of the data on recorded attacks is a matter of concern, as only 497 patients reported ≥ 1 attack. Of these patients, 359 (72%) recorded the attack by the App. The attacks from the remaining 138 were inserted by physicians. No attacks were recorded for 800 patients, thus raising some doubts regarding patient compliance. Another critical issue is the validation of attacks by physicians, which may result in a workload not always sustainable without adequate staff support.

Second, the registry needs to be fed continuously. So far, few European countries participate in this project, and the involved countries are far from covering the whole national patient population. Several HAE reference centers, even in the participating countries, did not provide data to this registry. Hungary is an exception, as it seems to have included the larger majority (91%) of the evaluated patients.

Finally, the dates of the first onset of symptoms were not captured, and dates about the diagnosis alone do not allow us to know what was the cause of delay in diagnosis. We can only calculate the mean delay of the diagnosis from the reference age of 20 years, as it was shown that 85% of HAE patients were already symptomatic during the first two decades of life [26]. The delay in diagnosis for HAE is estimated to range between 12 and 16.3 years from the first onset of symptoms [10, 13, 21, 27]. According to these presumptions, the mean delay in the diagnosis found in our study was circ. 5 years.

Conclusions

The establishment of a global registry for C1-INH-HAE allows physicians to collect and analyze a large amount of data about this rare disease. In the near future, a new version of the registry with additional tools is planned. This instrument will enable physicians to perform more analyses and obtain better understanding of the natural course of C1-INH-HAE, as well as evaluate quality-of-life and effectiveness of on-demand and prophylactic treatments.

Acknowledgments

The late Professor Marco Cicardi from Milano, Italy, made an indispensable contribution toward the establishment of this registry. We are grateful for his invaluable work in both research and patient care for hereditary angioedema patients, in Italy and worldwide. Prof. Cicardi passed away on August 2019.

Abbreviations

- C1-INH

C1 inhibitor

- C1-INH-HAE

Hereditary angioedema due to C1-Inhibitor deficiency

- CRF

Case-report form

- eCRF

Electronic case report form

- HAE

Hereditary angioedema

- HGR

HAE Global Registry

- HGRB

HAE Global Registry Board

- HGRSC

HAE Global Registry Scientific Committee

- IQR

Interquartile range

- LTP

Long-term prophylaxis

Author Contribution

All the authors contributed equally to the design of the research, analysis of the results, and writing of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Milano within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. Publishing support and journal styling services were provided by SEEd Medical Publishers and funded by AAEE onlus (Associazione volontaria per l’angioedema ereditario ed altre forme rare di angioedema).

Availability of Data and Material

Data available upon request from the authors.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

The competent board (Comitato Etico Indipendente Milano Area A, Registro Sperimentazioni n. 2015/ST/253) of the coordinating center in Milan approved the registry protocol as an investigator-initiated observational study in 2016 and the amended version on February 27, 2017.

Disclaimer

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

AZ received speaker/ consultancy fees from BioCryst, CSL Behring, Pharming, and Takeda. HF received honoraria and travel grants from CSL Behring, Shire/Takeda, Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, Octapharma, Kalvista and Pharming; and/or served as a consultant for these companies and has participated in clinical trials/registries for BioCryst, CSL Behring, Pharming, Kalvista and Shire. LB received honoraria and travel grants from CSL Behring, Novartis, Pharming and Takeda, and her institute received research funding from CSL Behring, Novartis and Takeda. NB received travel grants from CSL Behring, Shire-Takeda, Pharming Group NV, Chiesi Pharmaceuticals GmbH and speaker fees from Shire-Takeda and Glaxo-Smith Klein. AEG received research grants from Shire-Takeda. FP received speaker fees from Shire-Takeda, Novartis, CSL Behring. IB-G- reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Shire-Takeda and Biocryst, and non-financial support from Pharming and CSL Behring. MC received travel grants from CSL Behring, Menarini, Novartis, Shire-Takeda and consultancy fees from Biocryst, CSL Behring, Shire-Takeda. His Institution received scientific grants from CSL Behring and Shire-Takeda. LV, NA, MR, and MCR report no conflicts of interest.

Consent to Participate

Patients gave a written informed consent.

Consent for Publication

Patients gave a written informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cicardi M, Aberer W, Banerji A, et al. Classification, diagnosis, and approach to treatment for angioedema: consensus report from the Hereditary Angioedema International Working Group. Allergy. 2014;69:602–616. doi: 10.1111/all.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zanichelli A, Arcoleo F, Barca M, et al. A nationwide survey of hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency in Italy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:11. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0233-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busse PJ, Christiansen SC. Hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2020;2020(382):1136–1148. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra180801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cicardi M, Zuraw BL (2018) Angioedema Due to Bradykinin Dysregulation, The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, Volume 6, Issue 4, Pages 1132–1141, ISSN 2213–2198, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2018.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Laires P, Barros A, Lopes F, et al. Regispt: Registry of Registries In Portugal. Value Health. 2015;18:A563. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.1837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaletel M, Kralj M. (2016) Methodological guidelines and recommendations for efficient and rational governance of patient registries. PARENT 1–232. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/ehealth/docs/patient_registries_guidelines_en.pdf (last accessed December 2020)

- 7.Maurer M, Aberer W, Bouillet L, et al. (2013) Hereditary angioedema attacks resolve faster and are shorter after early icatibant treatment. Stover CM, ed. PLoS ONE 8: e53773; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0053773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Riedl MA, Bygum A, Lumry W, et al. Safety and usage of C1-inhibitor in hereditary angioedema: Berinert Registry Data. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:963–971. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Longhurst HJ, Zanichelli A, Caballero T, et al. Comparing acquired angioedema with hereditary angioedema (types I/II): findings from the Icatibant Outcome Survey: acquired versus HAE in the IOS. Clin Exp Immunol. 2017;188:148–153. doi: 10.1111/cei.12910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zanichelli A, Magerl M, Longhurst H, et al. (2013) Hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency: delay in diagnosis in Europe. All Asth Clin Immun 9: 29; https://doi.org/10.1186/1710-1492-9-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Psarros F, Koutsostathis N, Farmaki E, et al. Hereditary angioedema in Greece: the first results of the Greek Hereditary Angioedema Registry. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2014;164:326–332. doi: 10.1159/000366276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallbris L, Nordenfelt P, Björkander J, et al. The establishment and utility of Sweha-Reg: a Swedish population-based registry to understand hereditary angioedema. BMC Dermatol. 2007;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roche O, Blanch A, Caballero T, et al. Hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency: patient registry and approach to the prevalence in Spain. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94:498–503. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zingale LC, Bork K, Farkas H, et al. The European Register of Hereditary Angioedema: Experience and Preliminary Results. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:S276. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anon. Home | HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee. Available at https://www.genenames.org/ (last accessed October 2020)

- 16.Anon. Mutalyzer 2.0.32 — Welcome to the Mutalyzer website. Available at https://mutalyzer.nl/ (last accessed October 2020)

- 17.Anon. Population of European countries 2020. Statista. Available at https://www.statista.com/statistics/685846/population-of-selected-european-countries/ (last accessed October 2020)

- 18.Cancian M, Perego F, Senter R, et al. Pediatric angioedema: essential features and preliminary results from the Hereditary Angioedema Global Registry in Italy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020;31:22–24. doi: 10.1111/pai.13170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.S Betschel J Badiou K Binkley et al 2019 The International/Canadian Hereditary Angioedema Guideline Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 15 10.1186/s13223-0190-3768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Grumach AS, Valle SOR, Toledo E, et al. Hereditary angioedema: first report of the Brazilian registry and challenges. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e338–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bygum A. Hereditary angio-oedema in Denmark: a nationwide survey. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1153–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caballero T, Aygören-Pürsün E, Bygum A, et al. The humanistic burden of hereditary angioedema: Results from the Burden of Illness Study in Europe. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014;35:47–53. doi: 10.2500/aap.2013.34.3685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riedl MA. Critical appraisal of androgen use in hereditary angioedema: a systematic review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;114:281–288.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.EMA. Available at https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/takhzyro-epar-product-information_it.pdf (last accessed December 2020)

- 25.AboutPharma. Lanadelumab contro angioedema ereditario disponibile in Italia. AboutPharma. Available at https://www.aboutpharma.com/blog/2020/05/14/lanadelumab-contro-angioedema-ereditario-disponibile-in-italia/ (last accessed October 2020)

- 26.Agostoni A, Cicardi M. Hereditary and acquired C1-inhibitor deficiency: biological and clinical characteristics in 235 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1992;71:206–215. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199207000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouillet L, Launay D, Fain O, et al. Hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency: clinical presentation and quality of life of 193 French patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111:290–294. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request from the authors.