Abstract

Background:

The opioid crisis has put an increasing strain on US states over the last two decades. In response, all states have passed legislation to implement a portfolio of policies to address the crisis. Although effects of some of these policies have been studied, research into factors associated with state policy adoption decisions has largely been lacking. We address this gap by focusing on factors associated with adoption of naloxone access laws (NAL), which aim to increase the accessibility and availability of naloxone in the community as a harm reduction strategy to reduce opioid-related morbidity and mortality.

Methods:

We used event history analysis (EHA) to identify predictors of the diffusion of naloxone access laws (NAL) from 2001, when the first NAL was passed, to 2017, when all states had adopted NAL. A variety of state characteristics were included in the model as potential predictors of adoption.

Results:

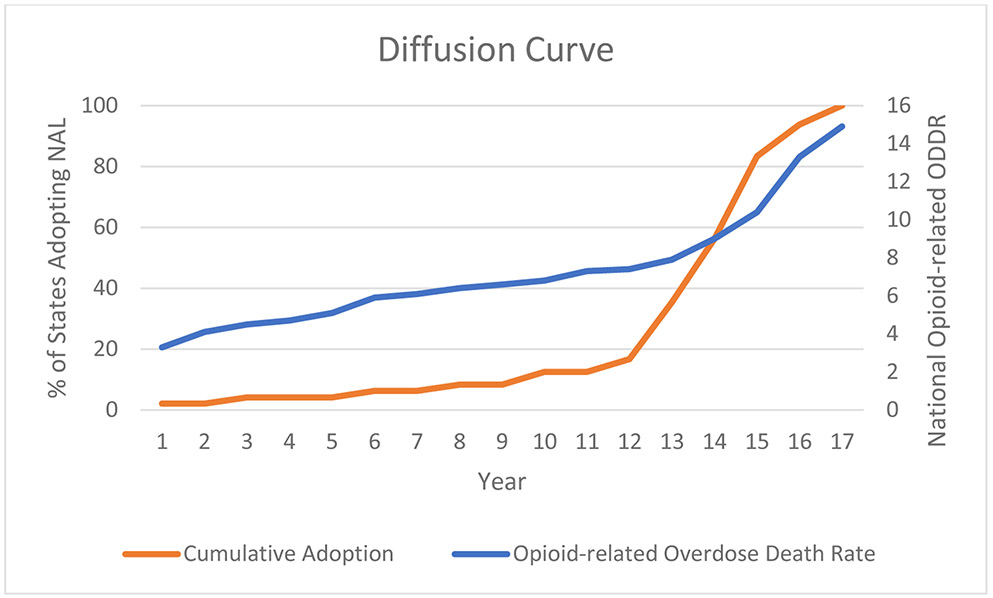

We found that state adoption of NAL increased gradually, then more rapidly starting in 2013. Consistent with this S-shaped diffusion process, the strongest predictor of adoption was prior adoption by neighboring states. Having a more conservative political ideology and having a higher percentage of residents who identified as evangelical Protestants were associated with later adoption of NAL.

Conclusion:

States appear to be influenced by their neighbors in deciding whether and when to adopt NAL. Advocacy for harm reduction policies like NAL should take into account the political and religious culture of a state.

Keywords: Naloxone, naloxone access laws, opioid policy, state policy diffusion, overdose prevention

1. Introduction

In 2019, there were 70,630 drug overdose deaths in the United States, with approximately 70% of these being opioid-related (Hedegaard et al., 2020a; Wilson et al., 2020). The drugs involved in opioid-related overdose deaths have evolved over the last two decades from predominantly prescription drugs, to heroin, to fentanyl and other synthetic opioid analogues. In all, the United States has lost around half a million lives since the beginning of the opioid crisis in 1999, with preliminary results showing that drug overdose deaths have continued to increase into 2020 (Ahmad et al., 2020; Hedegaard et al., 2020a; Wilson et al., 2020). In addition to the lives lost, opioid use disorder and fatal opioid overdoses are imposing a considerable cost on society, estimated at over $1 trillion in 2017 (Florence et al., 2021).

The federal government and many state governments have declared a public health emergency in the face of rising opioid-related overdose deaths (Haffajee and Frank, 2018; Jones et al., 2019). Prior to and in conjunction with these declarations, many state laws and regulations have been enacted to combat the epidemic, including those that restrict opioid prescriptions, establish prescription drug monitoring programs, legalize syringe exchanges, expand access to naloxone, and protect citizens who respond to an overdose from prosecution through Good Samaritan laws (Ansari et al., 2020). Many of these laws had little to no evidence supporting them when they were adopted. In addition, this issue is more pressing in some states as state-level overdose death rates vary. While the national average for the age-adjusted drug overdose death rate was 20.7 per 100,000 in 2018, the highest state, West Virginia, had a rate of 51.5 and the lowest state, South Dakota, had a rate of 6.9, more than a seven-fold difference (Hedegaard et al., 2020b). Despite apparent variation in motivation for state adoption of many of these laws, research regarding factors associated with adoption has largely been lacking.

1.1. History of Naloxone Access Laws

Naloxone is a drug that reverses an opioid overdose if given in enough time and at the appropriate dose. Increasing the accessibility and availability of naloxone has been pursued by states as a harm reduction response to the opioid crisis. Naloxone is made available through three main mechanisms: distribution by community-based organizations, administration by uniformed first responders to an overdose, and dispensing from a pharmacy (Weiner et al., 2019). One type of opioid policy to promote the distribution of naloxone is naloxone access laws (NAL), which typically simplify the process to obtain the opioid overdose antidote and expand both who can receive it and who can distribute it. These laws vary by state and may include one or more of the following provisions: allowing non-patient-specific prescriptions through a standing or protocol order; granting prescriptive authority to pharmacists; allowing third-party prescribing that circumvents the requirement for a provider-patient relationship; and/or removal of professional, civil, or criminal liability from administrating, prescribing, or dispensing naloxone (Davis and Carr, 2017, 2015). In response to a rising death toll from opioid overdoses, New Mexico was the first to pass a NAL in 2001 (N.M. Stat., sec. 24-23-1). Since 2001, all fifty states and the District of Columbia have passed some version of a NAL. Currently, a large majority of states have a NAL that allows a standing order and third-party prescribing, and provides immunity to dispensing pharmacists (Davis and Carr, 2017).

1.2. Evidence for Naloxone and Naloxone Access Laws

Naloxone distribution has become an evidence-based intervention to prevent opioid-related overdose deaths and is included as a component of most local and state responses to the opioid crisis. Indeed, modeling studies have suggested that expanding the access and availability of naloxone in communities is one of the most impactful interventions in decreasing opioid-related overdose deaths (Ballreich et al., 2020; Irvine et al., 2019; Pitt et al., 2018). Studies indicate that naloxone distribution is most effective when targeted towards people who use drugs (Walley et al., 2013; Wheeler et al., 2015), but distribution to family members and law enforcement, as well as co-prescription with high-dose prescription opioids, has also been shown to be effective (Bagley et al., 2018; Coffin et al., 2016; Davis et al., 2014; Green et al., 2020).

By 2017, all states had enacted some form of NAL, with variation across states in included provisions and timing (Davis and Carr, 2017). A systematic review of 11 studies evaluating NAL generally found the laws to be beneficial, with strong evidence that they increase the amount of naloxone available in communities, although findings are mixed regarding the effect on opioid-related mortality (Smart et al., 2020). For instance, Rees et al. (2019), using data from 1999-2014, found that adoption of NAL was associated with a 9-10% reduction in opioid-related deaths compared with states that had no such laws, and McClellan et al. (2018), using 2000-2014 data, found a 14% lower incidence of opioid-related mortality in states that had a NAL. By contrast, other evidence suggests an association between NAL and increased opioid-related mortality, which could result if NAL decreases the perceived danger of opioid use (Erfanian et al., 2019). However, the rigor of the methodologies used in these population-level studies has been questioned (Mauri et al., 2020; Smart et al., 2020). Naloxone access laws can also have collateral effects, facilitating the implementation of overdose education and naloxone distribution programs in states (Lambdin et al., 2018).

1.3. Theoretical Framework for Policy Diffusion

Rogers (2003) first put forth Diffusion of Innovation Theory in 1962 to explain how an innovation gains momentum and spreads across individuals or organizations. Under the assumption that adoptions of an innovation follow a normal distribution over time, he posited that five categories of adopters could be identified: Innovators (two standard deviations ahead of the distribution mean, or first 2.5%), Early Adopters (one standard deviation ahead of the mean, or next 13.5%), Early Majority (between one standard deviation ahead of the mean and the mean, or next 34%), Late Majority (up to one standard deviation after the mean, 34%), and Laggards (one standard deviation or more after the mean, 16%). A normal distribution of adopters over time generates the frequently observed S-shaped diffusion curve of cumulative adoption, which is typically associated with influence among the adopters, either by direct communication between adopters and potential adopters, or through more indirect mechanisms such as competition (Dearing and Cox, 2018).

Walker (1969) applied Diffusion of Innovation Theory to examine American federalism and the policymaking process, with a focus on a state’s political, economic, and social characteristics that influence policy adoption. However, external factors, such as the behavior of neighboring states, are also likely to influence the policymaking process (Berry and Berry, 2018). Therefore, an empirical model must account for both internal and external determinants of state policy diffusion. Berry and Berry (1990), in their seminal paper on state lottery adoption, put forth event history analysis (EHA) as a new methodology to combine these two models. This statistical method allows for examining both internal and external factors that impact state policy adoption using regression techniques on a uniquely structured data set. Subsequent research has recommended that EHA policy diffusion models capture three domains: motivation, resources and obstacles, and external diffusioni effects (Berry and Berry, 2018). Previous literature has examined the diffusion of a wide array of state policies including abortion laws (Mooney and Lee, 1995), education reform (Mintrom, 1997), same-sex marriage laws (Haider-Markel, 2001), HMO reform (Balla, 2001), and health policies under the Affordable Care Act (Volden, 2017).

Only three studies, to our knowledge, have looked specifically at the diffusion of a drug policy across states or cities using EHA. Shipan and Volden (2008) examined the diffusion of anti-smoking policies at the city level for a sample of 675 large cities and found that state government coercion, economic competition of adjacent cities, imitation of specific larger cities deemed to be trend setters, and learning from early adopters were all significant factors in policy adoption. Macinko and Silver (2015) examined impaired driving laws at the state level and found that the proportion of younger drivers in a state and adoption by a neighboring state were strong predictors of first-time law adoption. Bradford and Bradford (2017) examined the diffusion of medical marijuana laws across states and found that the statistically significant predictors of earlier adoption of a marijuana law were state citizen ideology and adoption of the law by neighboring states.

In this study, we use Berry and Berry’s (2018) classification of motivations, resources and obstacles, and external diffusion effects to construct an EHA model of state adoption of NAL. Motivational effects indicate how driven state officials are to adopt a policy. This is represented in our model by the age-adjusted opioid-related overdose death rate of the state in the previous year, the state’s citizen and government ideology in the previous year, and whether the state is in a gubernatorial election year. We hypothesize that a higher opioid-related overdose death rate predicts earlier state adoption of a NAL given the immediacy of the issue, and a more conservative political ideology predicts later adoption given documented opposition to harm reduction strategies (Cloud et al., 2018; Kishore et al., 2019). Although a gubernatorial election year may increase the salience of opioid-related overdose deaths, the effect of this variable may depend on the relative strength of the political parties, which likely varies across states and across time within a state.

Resources and obstacles are factors that can either facilitate or serve as a barrier to adoption of a policy and are represented in our model by state median household income, state population, and the percent of evangelical Protestants and Blacks in the state. We hypothesize that a smaller state population will predict later adoption given the decreased impact of a lower absolute number of opioid-related overdose deaths, and that a larger presence of traditionalist religious groups predicts later adoption given a more likely perspective that drug use is a moral issue (Ezell et al., 2021; Szott, 2020). We hypothesize that states with larger Black populations will adopt NAL later due to policy legacy of more criminal justice-based responses and the greater policy attention to opioid problems in contexts where white populations were particularly affected (Hart and Hart, 2019; Netherland and Hansen, 2016).

External diffusion effects take into account the behavior of neighboring states and are represented in our model by the percent of border states that have enacted a NAL as of the previous year. We hypothesize that adoption of a NAL by neighboring states predicts earlier adoption, as strong influence on the behavior of neighboring states is a common finding in EHA studies (Mallinson, 2020)

1.4. Study objective

This study aims to better understand the state characteristics that predict earlier versus later adoption of a NAL, which have been implemented in all fifty states. States have adopted a variety of policies and laws to address the opioid crisis, providing an opportunity to better understand why states adopt policy interventions in this scenario. Although the effects of some opioid policies and laws have been studied, research into factors associated with state adoption of these policy interventions has largely been lacking. We address this gap by focusing on factors associated with the adoption of naloxone access laws (NAL). To our knowledge, this is the first policy diffusion study on an opioid policy or law and the first to look at how states have responded to a crisis that was later declared a public health emergency.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

We used the Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System (PDAPS, 2017) to identify when each state first implemented a NAL. Data on opioid-related mortality were obtained through the National Vital Statistics System multiple cause-of-death mortality files (CDC, 2020). We used an updated version of political ideology measurements at the state level from Berry et al. (1998) to derive a measure of state government and citizen ideology (Fording, 2018). The presence of a gubernatorial election year was derived from the National Council on State Legislatures, state median household income from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, state population and percentage of Blacks in each state from the United States Census Bureau, and the percentage of evangelical Protestants in each state from the Religious Landscape Study by the Pew Research Center. Means of the study variables, divided into categories where only one state had adopted (2001), more than a third of states had adopted (2013), and nearly all states had adopted (2016), can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable Means and Standard Deviations of Modeled Internal and External Factors Over Naloxone Access Law Diffusion Period

| 2001 Mean and SD |

2013 Mean and SD |

2016 Mean and SD |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid-related Overdose Rate per 100,000 People | 6.30 (2.71) |

14.31 (5.11) |

13.94 (4.00) |

| Citizen Ideology | 43.03 (14.36) |

44.70 (13.76) |

38.50 (7.80) |

| Government Ideology | 45.93 (14.02) |

37.63 (15.85) |

30.96 (10.89) |

| Percent of Neighboring States with NAL Enacted | 1.97 (5.91) |

29.93 (22.05) |

87.50 (13.39) |

| State Median Household Income | 42033.15 (6346.14) |

51281.26 (8176.84) |

57196.29 (1224.26) |

| Percent of Evangelical Protestants | 26.28 (11.29) |

28.23 (11.16) |

28.71 (3.73) |

| Percent of Black Population | 10.89 (9.60) |

11.43 (10.27) |

3.86 (3.94) |

| Gubernatorial Election Year | 0.04 (0.20) |

0.05 (0.22) |

0.29 (0.49) |

| State Population, in Millions | 6.00 (6.36) |

5.68 (5.24) |

3.08 (2.56) |

| Adoption of NAL | 0.02 (0.15) |

0.23 (0.43) |

0.57 (0.53) |

| Time | 1 (0) |

13 (0) |

16 (0) |

629 observations across 47 states from 2001-2017

Both citizen and government ideology scaled from 1-100 with 1= most conservative and 100=most liberal

2.2. Measures and Statistical Approach

For this study, we defined a NAL as present in a given year if a state has implemented any of the provisions that address access to naloxone as reported by the Prescription Drug Abuse Policy System (2017). Our variable of interest is defined by the year that a state implements a NAL for the first time, regardless of the type of provisions it includes, which is referred to as the adoption year throughout the paper.

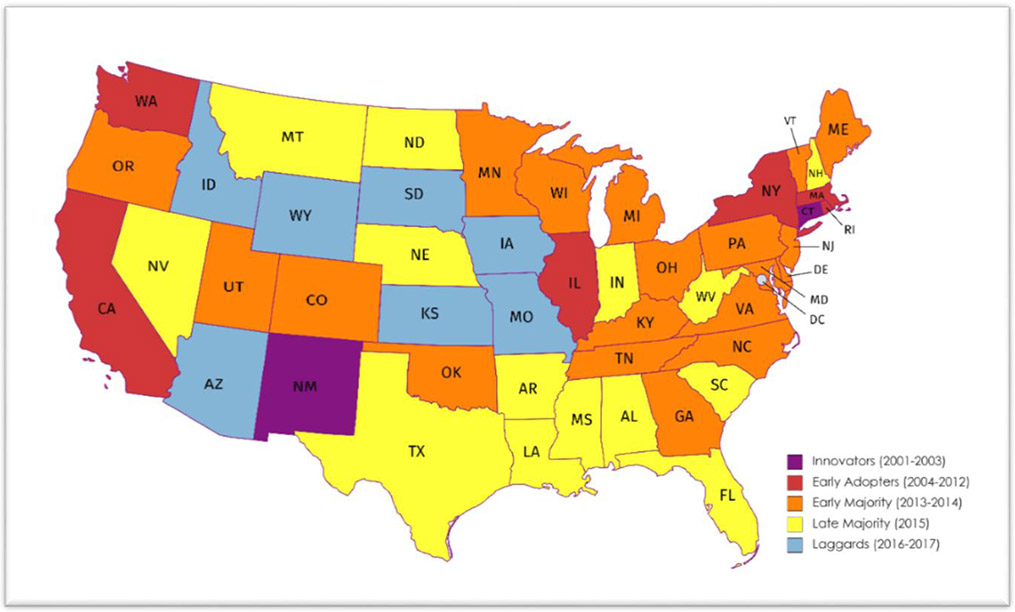

We use adoption of NAL from 2001 to 2017 in all 48 contiguous states to plot a diffusion curve. We use the categories defined by Diffusion of Innovation Theory (Rogers, 2003) to identify states as innovators (first two states to adopt or 4.2% of states), early adopters (next six states to adopt or 12.5% of states), early majority (next 19 states to adopt or 39.6% of states), late majority (next 14 states to adopt or 29.2% of states), and laggards (last seven states to adopt or 14.6% of states).

‘Motivational’ covariates include the age-adjusted state-level opioid-related overdose death rate from the previous year, whether or not it is a gubernatorial election year, and a state’s citizen and government ideology from the previous year. We include measures for both citizen and government ideology (an index measuring 0 for most conservative and 100 for most liberal) as the former captures the relationship between political power and party control in state policymaking institutions and the latter captures voter perceptions of their congressional representatives (Berry et al., 1998). The ideological positions of a state government and its citizens can diverge given frequent changes in party control over time (Berry et al., 2010). This is especially relevant given that the opioid crisis has been termed a ‘bipartisan’ issue (Blendon et al., 2016), although state governments vary on their strategies to address the issue based on political ideology (Grogan et al., 2020).

For our ‘resources and obstacles’ covariates, state population and percentages of Blacks in each state are taken from the Census Bureau estimates for each year, and state median household income is derived from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The percentage of evangelical Protestants in the state is the estimated percent of adults 18 and older who reported this religious affiliation based on a nationally representative telephone survey that allows for state-level estimates. We chose evangelical Protestants as a proxy for the presence of traditionalist religious groups, as done in previous EHA studies (Clark, 2013; Haider-Markel, 2001). Our ‘external diffusion effects’ covariate is the percentage of bordering states that have implemented a NAL as of the previous year.

We model states’ adoption decisions using event history analysis (Berry and Berry, 1990). The basic model for state i in time t is:

Where Pr[ADOPTi,t = 1] is our dependent variable and the probability that the state i will adopt a NAL policy in year t given that the state has not adopted the policy prior to year t, βj are parameters to be estimated, ηi,t denotes an error term, and Φ represents the cumulative normal distribution function. Note that some covariates are lagged as we would expect the effects of most of the ‘motivational’ covariates in the previous year and the bordering states that have implemented a NAL as of the previous year to impact adoption of NAL in the current year. In addition, all covariates are time-varying except for the percentage of evangelical Protestants and Blacks in each state, for which data were limited and there was little fluctuation from year to year (Pew Research Center, 2014; U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). A categorical variable indicating the census division for each state has been added to account for geographic clustering.

Table 1 presents variable means and standard deviations for the covariates in our EHA model across different time points, illustrating how the NAL predictors changed over the study period for states still at risk to adopt NAL. The first column represents variable means for all states in our sample that were at risk to adopt NAL at the beginning of the study period. The second column represents variable means in 2013 for those states that were either early majority, late majority, or laggards. The final column represents variable means in 2016 for laggard states.

2.3. Data Analysis

We plotted a cumulative distribution function to depict the diffusion of NAL across states. We used event history analysis (EHA) to identify predictors of the adoption of NAL from 2001, when the first NAL was passed, to 2017, when all fifty states had adopted NAL. To perform EHA, a data set must be constructed where the study period begins when the first state adopts a NAL (New Mexico in 2001) and each state gets a “0” for each year it is at risk but does not adopt the policy and a “1” for the year that it adopts the policy. After adoption, the state will drop out of the data set. For example, Alabama passed a NAL in 2015. Therefore, there will be 15 observations for Alabama in the EHA dataset from 2001-2015 with years 2001-2014 receiving a “0” for the dependent variable and 2015 will get a “1”. Once this data set is organized correctly, an event history model with time-varying covariates can be estimated using probit regression.

Our estimated coefficients report the instantaneous hazard of adopting a NAL. We also present estimation results as marginal effects, which gives a more straightforward interpretation: the change in the likelihood of adoption for each year given a one-unit increase in the variable under consideration. A positive (negative) marginal effect suggests a greater (lesser) likelihood of adoption in each year. Statistical significance is reported at two levels: p < 0.05 and p < 0.01.

We made several methodological decisions based on the literature and potential violations of probit regression assumptions. First, we used robust standard errors clustered on states to account for repeat observations of each state, and we used a categorical variable for the 9 U.S. census divisions corresponding to each state to control for geographic clustering (Buckley and Westerland, 2004; Macinko and Silver, 2015). Second, we tested for multicollinearity using variance inflation factors (VIF) and removed state median household income from our model due to a VIF > 4, it not being a variable of interest, and its removal resulting in a higher pseudo-R2 for our model (Graham, 2003). Third, we did not include Alaska and Hawaii in the data set as is common in EHA studies given that they do not have border states (Berry and Berry, 1990; Mintrom, 1997). Fourth, we removed North Dakota from the data set because the opioid-related overdose death rate for most years during the study period was missing. Fifth, we logged the state population covariate to minimize the impact of outliers, as done in previous EHA studies (Volden, 2006; Wipfli et al., 2010). Finally, we controlled for duration dependence, as suggested by Buckley and Westerland (2004), by adding a time covariate. Due to our analysis using a relatively high-dimensional data set (i.e. a large number of variables relative to the sample size), we ran a double-selection lasso regression on the significant explanatory variables as a sensitivity analysis (Belloni et al., 2014). All statistical analyses were done using Stata/SE version 16.

3. Results

3.1. Diffusion of Naloxone Access Laws Across Fifty States

As seen in Figure 1, all fifty states adopted a NAL during the study period (2001-2017), with New Mexico adopting the first NAL in 2001. Adoption of NAL appeared gradual until 2013 when there was a rapid increase in state adoption of NAL. For illustrative purposes, Figure 1 overlays the national curve of the age-adjusted opioid-related overdose death rate during the study period (CDC, 2020). The diffusion curve appears similar to the overdose death rate over the study period: initially rising gradually then rapidly increasing starting in 2012. Figure 2 depicts how states are classified according to Rogers’ (2003) Diffusion of Innovation Theory. New Mexico and Connecticut, where NAL passed in 2001 and 2003 respectively, were classified as innovators. Whereas states bordering Connecticut were early adopters of NAL, states bordering New Mexico adopted NAL later. Early adopters appeared across the United States, though most were in the West and Northeast regions. States in the ‘Late majority’ category were predominantly in the Deep South, whereas the ‘laggard’ states were concentrated in the western Midwest, upper Great Plains, and northern Rocky Mountain regions of the United States.

Figure 1. Cumulative Adoption of Naloxone Access Laws in 48 Contiguous States Over Time.

*Death data from the National Vital Statistics System multiple cause-of-death mortality files

*Does not include Alaska or Hawaii (n=48)

*Year 1 corresponds with 2001 and Year 17 corresponds with 2017

*ODDR = Overdose death rate

*NAL = Naloxone access law

Figure 2. Adoption of Naloxone Access Laws Across the Contiguous United States.

3.2. Predictors of Adopting Naloxone Access Laws

Table 2 presents the results of EHA on the adoption of NAL across 47 states from 2001 to 2017, reporting both model coefficients and marginal effects.

Table 2.

Predictors and Marginal Effects of Adopting a Naloxone Access Law

| Coefficient | Robust Standard Errors |

Marginal Effect |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid-related Overdose Rate per 100,000 People | 0.0060 | 0.0190 | 0.0005 |

| Citizen Ideology | −0.0228 | 0.0134 | −0.0019 |

| Government Ideology | 0.0198* | 0.0078 | 0.0016** |

| Percent of Border States with NAL Enacted | 0.0204** | 0.0042 | 0.0017** |

| Percent of Evangelical Protestants | −0.0331** | 0.0127 | −0.0027** |

| Percent of Black Population | 0.0099 | 0.0141 | 0.0008 |

| Gubernatorial Election Year | 0.1100 | 0.2167 | 0.0090 |

| Logged State Population, in Millions | 0.3018** | 0.1163 | 0.0246** |

| Time | 0.1552* | 0.0771 | 0.0127* |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

−629 observations across 47 states from 2001-2017. Census division categorical variable used to control for geographic clustering found to not be statistically significant and not reported.

External Diffusion Effects:

The percent of bordering states that had passed a NAL as of the previous year was found to be the most significant explanatory variable in our model (p < 0.0001). On average, a state has four bordering states. Interpreting the marginal effects, a 25 percentage point increase in the proportion of border states that have passed a NAL in the previous year (i.e., on average one state) increased the likelihood that a state that still had not adopted a NAL would do so by 4.3% in each year (This is computed as the marginal effect (0.0017) multiplied by the 25 percentage points). This explanatory variable remained significant after sensitivity analysis using double-selection lasso regression (p = 0.001).

Motivational Effects:

Of the motivational variables, only government ideology was found to be a statistically significant driver of NAL adoption (p = 0.011). That is, a more liberal government ideology was associated with state adoption of NAL. Specifically, a 10% increase in the government ideology index in the previous year increased the likelihood that a state that still had not adopted a NAL would do so by 1.6% in each year. Government ideology remained a significant explanatory variable after sensitivity analysis using double-selection lasso regression (p = 0.048).

Resources and Obstacles:

Of the resources and obstacles variables, both the percent of evangelical Protestants in the state (p = 0.009) and the logged state population (p = 0.009) had a significant effect on adoption of NAL. A 10% increase in the percentage of evangelical Protestants in a state decreased the likelihood that a state that had not yet adopted a NAL would do so by 2.7% in each year. A one-million-person increase in a state’s logged population increased the likelihood of state adoption by 2.5%. Only the percent of evangelical Protestants was significant using sensitivity analysis with double-selection lasso regression (p = 0.021).

4. Discussion

We found that state adoption of NAL increased gradually, then increased more rapidly starting in 2013. The diffusion curve follows a similar path to the national age-adjusted opioid-related overdose death rate, which also increased linearly then increased more rapidly starting in 2013. These more rapid increases in NAL adoption and the overdose death rate coincided with the emergence of fentanyl as a major contributor to the opioid crisis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020a) along with growing expert consensus on the benefits of naloxone as an overdose prevention strategy (Beletsky et al., 2012; Compton et al., 2013; National Academies of Sciences, 2017) and studies that showed the effectiveness of community naloxone access in decreasing opioid-related mortality (Clark et al., 2014; Walley et al., 2013; Wheeler et al., 2015), although evidence specific to NAL would not appear in the literature until several years later. Previous literature suggests that widespread diffusion of interventions without evidence of effectiveness can occur in a perceived crisis situation (Des Jarlais et al., 2006), which may help explain the more rapid increase of NAL adoption beginning in 2013.

Consistent with an S-shaped diffusion process, the strongest predictor of adoption was prior adoption by neighboring states. Adoption by neighboring states is commonly found to be a significant predictor in EHA models of policy diffusion (Mallinson, 2020), though it is difficult to parse out whether states are learning from or competing with each other (Shipan and Volden, 2008). For instance, proponents of NAL can use neighboring states’ enactment as an argument for focal state enactment, and proponents in a focal state may learn from their counterparts in neighboring states which arguments work best to promote or hinder passage, highlighting the complexities that may underlie efforts to pass or block this legislation.

We found that political ideology and religious beliefs played a role in adoption of NAL, with states that had a more conservative government ideology and higher percentage of evangelical Protestants more likely to adopt NAL later. Historically, harm reduction strategies, such as naloxone distribution, syringe service programs (SSPs), and safe consumption sites (SCSs), have been controversial despite rigorous evidence (Nadelmann and LaSalle, 2017). Opposition to harm reduction services, especially SSPs, has been documented in more conservative states (Cloud et al., 2018; Kishore et al., 2019) and in religious groups (Ezell et al., 2021; Szott, 2020). Despite this opposition, advocates have been successful in changing policy at the state-level (Cloud et al., 2018) and the presence of and solidarity with other grassroots organizations such as ACT UP within a state has been documented as a key factor in proliferation of harm reduction strategies (Tempalski et al., 2007). More recently, tools to integrate harm reduction services into faith-based organizations have been created (Harm Reduction Coalition, 2020), acknowledging efforts for broader coalition-building (Downing et al., 2005).

At a fundamental level, faith-based institutions play important roles in community responses to the opioid crisis like naloxone access and other harm reduction approaches. The trauma of loss following an untimely death is profound, and, with drug-involved deaths, can be extremely isolating for grieving family and friends. Faith-based institutions are critical grief supports, and also may be the only source of care and support for the vulnerable at risk of addiction and those suffering substance use disorders. Some faith-based organizations may consider naloxone, otherwise called the "Lazarus drug", as embodying the promotion of tolerance, human dignity, and redemption; policy makers may see the same medication as an evidence-based, cost-effective approach to overdose mortality reduction. Future research could identify other policy intersections and continue the exploration of their effects.

It is possible that the government ideology and evangelical Protestant variables served as a proxy for the absence of harm reduction strategies or activism. While our analysis did not include variables representing a state’s harm reduction orientation such as number of SSPs as an external effect, future analyses could do so, although there may be issues given that SSP presence is likely jointly determined with NAL adoption. We studied a state's initial adoption of any NAL provision, although different types of NAL provisions may reflect different levels of harm reduction. Future work might examine the adoption of multiple provisions over time, including adoption sequences within states over time, and their relationships to a harm reduction orientation. This may shed light on the complex and evolving relationship between religion, politics, and harm reduction.

From Figure 2, it is evident that state adoption of NAL is not random but appears geographically clustered. If other studies of drug policy find similar clusters in adoption timing, information about the clusters may be used to inform future policy initiatives. For example, Bradford and Bradford (2017) found that, in addition to the effect of neighboring states, a more liberal citizen ideology increased the likelihood of legalizing marijuana for medical use. It is possible that observed predictors for NAL adoption may not be unique but a feature of any progressive law, given that previous research as shown persistent policy diffusion patterns among states with similar demographic and political characteristics (Desmarais et al., 2015). More generally, studies that have examined sequences of state adoption across multiple policies have found relatively consistent patterns in those sequences, suggesting underlying mechanisms of interstate policy influence (Desmarais et al., 2015). Future work could focus on sequences of state adoption of drug policies to better understand interstate influence in this subset of policies.

Nationally, despite the implementation of a variety of opioid policies, overdose deaths continue to increase (Hedegaard et al., 2020a). Innovative policies are needed, which may include harm reduction strategies that may be perceived as controversial like safe consumption sites, drug checking services, and ensuring a safe drug supply (Pardo et al., 2020). Our findings support the idea that advocacy for state-level harm reduction policies might be better-informed by considering the intersection of the political and religious culture of a state.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

The study has several strengths. It is the first to examine the diffusion of a policy across states to address the opioid crisis, which was eventually declared a public health emergency. We used EHA, the hallmark statistical model for studying state policy diffusion (Berry and Berry, 1990), and incorporated a more rigorous design as suggested by Buckley and Westerland (2004) by controlling for duration dependence, geographical clustering, and repeated observations by states. Because the policy innovation chosen for study, adoption of a NAL, occurred over a number of years, we were able to examine the effects of a variety of factors on the diffusion process, as both aspects of NAL and state contexts changed over those years.

There are several limitations to this study. First, grouping all NAL variants together may obscure nuances of the adoption of specific provisions. Some of these NAL variants have been found to be more effective than others in increasing naloxone and impacting other downstream outcomes (Smart et al., 2020). Follow-up studies assessing the adoption of specific types of NAL are needed. Second, we dropped one state from our analysis due to missing data. We note that since the non-contiguous states of Hawaii and Alaska do not have bordering states, their exclusion is common in EHA studies. Third, states may learn from other states that they see as similar but are not bordering states (Bricker and LaCombe, 2020), an effect that our approach would not have captured. Fourth, we use the adoption date as the implementation of NAL rather than the enactment of NAL. Although enacted laws in certain states become effective on predetermined days of the year, the implementation date is likely to serve as a good proxy for a state policymaker’s decision to adopt NAL. Finally, given that this is a state-level analysis, there is limited statistical power for our regression analysis. However, we were able to include the covariates that appeared most salient based on theory and previous literature.

4.2. Conclusion

Our study is the first to examine the diffusion of a policy across states to address the opioid crisis. Our findings show that the adoption of NAL is not random, but is a function of neighboring state behavior, state political ideology, and cultural beliefs within a state. As innovative harm reduction policies are likely needed to address increasing overdose deaths (Hedegaard et al., 2020a), advocacy for these potentially controversial policies might be better-informed by considering the intersection of the political and religious culture of a state.

Highlights.

State adoption of naloxone access laws (NAL) increased rapidly starting in 2013

The diffusion curve follows a similar path to the opioid-related overdose death rate

The strongest predictor of NAL adoption was prior adoption by neighboring states

Political ideology and religious beliefs played a role in adoption of NAL

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Brandeis-Harvard NIDA Center for providing financial support for this paper along with helpful feedback.

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by grant number P30 DA035772. Dr. Green is supported by NIH/NIDA R01DA045745 and DA045848.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interests

No conflict declared

In the policy diffusion literature cited here, “external diffusion” refers to influences on adoption outside a potential adopter, such as the influence of prior adopters. In other diffusion literature, however, the term “externally-driven diffusion” refers to diffusion patterns driven by factors outside the system of adopters and potential adopters, such as national visibility of a problem the innovation is intended to address. In this latter literature, the corresponding term “internally-driven diffusion” includes both factors internal to potential adopters and the influence of prior adopters. For this study, we have adopted the terminology used in the policy diffusion literature.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmad FB, Rossen LM, Sutton P, 2020. Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts [WWW Document]. Natl. Cent. Health Stat URL https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm [Google Scholar]

- Ansari B, Tote KM, Rosenberg ES, Martin EG, 2020. A Rapid Review of the Impact of Systems-Level Policies and Interventions on Population-Level Outcomes Related to the Opioid Epidemic, United States and Canada, 2014-2018. Public Health Rep. 135, 100S–127S. 10.1177/0033354920922975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley SM, Forman LS, Ruiz S, Cranston K, Walley AY, 2018. Expanding access to naloxone for family members: The Massachusetts experience. Drug Alcohol Rev. 37, 480–486. 10.1111/dar.12551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balla SJ, 2001. Interstate Professional Associations and the Diffusion of Policy Innovations. Am. Polit. Res 29, 221–245. 10.1177/1532673X01293001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballreich J, Mansour O, Hu E, Chingcuanco F, Pollack HA, Dowdy DW, Alexander GC, 2020. Modeling Mitigation Strategies to Reduce Opioid-Related Morbidity and Mortality in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2023677. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.23677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beletsky L, Rich JD, Walley AY, 2012. Prevention of Fatal Opioid Overdose. JAMA 308, 1863. 10.1001/jama.2012.14205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belloni A, Chernozhukov V, Hansen C, 2014. High-Dimensional Methods and Inference on Structural and Treatment Effects. J. Econ. Perspect 28, 29–50. 10.1257/jep.28.2.29 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry FS, Berry WD, 2018. Innovation and Diffusion Models in Policy Research, Theories of the Policy Process. Routledge. 10.4324/9780429494284-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry FS, Berry WD, 1990. State Lottery Adoptions as Policy Innovations: An Event History Analysis. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev 84, 395–415. 10.2307/1963526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berry WD, Fording RC, Ringquist EJ, Hanson RL, Klarner CE, 2010. Measuring Citizen and Government Ideology in the U.S. States: A Re-appraisal. State Polit. Policy Q 10, 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Berry WD, Ringquist EJ, Fording RC, Hanson RL, 1998. Measuring Citizen and Government Ideology in the American States, 1960-93. Am. J. Polit. Sci 42, 327–348. 10.2307/2991759 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blendon R, McMurtry C, Benson J, Sayde J, 2016. The Opioid Abuse Crisis Is A Rare Area Of Bipartisan Consensus. Health Affairs Blog. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford AC, David Bradford W, 2017. Factors driving the diffusion of medical marijuana legalisation in the United States. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 24, 75–84. 10.3109/09687637.2016.1158239 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker C, LaCombe S, 2020. The Ties that Bind Us: The Influence of Perceived State Similarity on Policy Diffusion. Polit. Res. Q 1065912920906611. 10.1177/1065912920906611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley J, Westerland C, 2004. Duration Dependence, Functional Form, and Corrected Standard Errors: Improving EHA Models of State Policy Diffusion. State Polit. Policy Q 4, 94–113. 10.1177/153244000400400105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020a. Understanding the Epidemic ∣ Drug Overdose ∣ CDC Injury Center; [WWW Document]. URL https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html (accessed 1.21.21). [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [WWW Document], 2020b. . Natl. Vital Stat. Syst URL https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/deaths.htm (accessed 12.28.20).

- Clark AK, Wilder CM, Winstanley EL, 2014. A systematic review of community opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs. J. Addict. Med 8, 153–163. 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark BY, 2013. Multilateral, regional, and national determinants of policy adoption: the case of HIV/AIDS legislative action. Int. J. Public Health 58, 285–293. 10.1007/s00038-012-0393-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloud DH, Castillo T, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Dubey M, Childs R, 2018. Syringe Decriminalization Advocacy in Red States: Lessons from the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep 15, 276–282. 10.1007/s11904-018-0397-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin PO, Behar E, Rowe C, Santos G-M, Coffa D, Bald M, Vittinghoff E, 2016. Non-randomized intervention study of naloxone co-prescription for primary care patients on long-term opioid therapy for pain. Ann. Intern. Med 165, 245–252. 10.7326/M15-2771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Volkow ND, Throckmorton DC, Lurie P, 2013. Expanded Access to Opioid Overdose Intervention: Research, Practice, and Policy Needs. Ann. Intern. Med 158, 65–66. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CS, Carr D, 2017. State legal innovations to encourage naloxone dispensing. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc 57, S180–S184. 10.1016/j.japh.2016.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CS, Carr D, 2015. Legal changes to increase access to naloxone for opioid overdose reversal in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 157, 112–120. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CS, Ruiz S, Glynn P, Picariello G, Walley AY, 2014. Expanded Access to Naloxone Among Firefighters, Police Officers, and Emergency Medical Technicians in Massachusetts. Am. J. Public Health 104, e7–e9. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing JW, Cox JG, 2018. Diffusion Of Innovations Theory, Principles, And Practice. Health Aff. (Millwood) 37, 183–190. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Sloboda Z, Friedman SR, Tempalski B, McKnight C, Braine N, 2006. Diffusion of the D.A.R.E and Syringe Exchange Programs. Am. J. Public Health 96, 1354–1358. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmarais BA, Harden JJ, Boehmke FJ, 2015. Persistent Policy Pathways: Inferring Diffusion Networks in the American States. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev 109, 392–406. [Google Scholar]

- Downing M, Riess TH, Vernon K, Mulia N, Hollinquest M, McKnight C, Des Jarlais DC, Edlin BR, 2005. What’s Community Got to Do with It? Implementation Models of Syringe Exchange Programs. AIDS Educ. Prev. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. AIDS Educ 17, 68–78. 10.1521/aeap.17.1.68.58688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erfanian E, Collins AR, Grossman D, 2019. The Impact of Naloxone Access Laws on Opioid Overdose Deaths in the U.S. Rev. Reg. Stud 29. [Google Scholar]

- Ezell JM, Walters S, Friedman SR, Bolinski R, Jenkins WD, Schneider J, Link B, Pho MT, 2021. Stigmatize the use, not the user? Attitudes on opioid use, drug injection, treatment, and overdose prevention in rural communities. Soc. Sci. Med 268, 113470. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florence C, Luo F, Rice K, 2021. The economic burden of opioid use disorder and fatal opioid overdose in the United States, 2017. Drug Alcohol Depend. 218, 108350. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fording RC, 2018. State Ideology Data [WWW Document]. URL https://rcfording.com/state-ideology-data/ (accessed 1.7.21).

- Graham MH, 2003. Confronting Multicollinearity in Ecological Multiple Regression. Ecology 84, 2809–2815. 10.1890/02-3114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green TC, Davis C, Xuan Z, Walley AY, Bratberg J, 2020. Laws Mandating Coprescription of Naloxone and Their Impact on Naloxone Prescription in Five US States, 2014–2018. Am. J. Public Health 110, 881–887. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan CM, Bersamira CS, Singer PM, Smith BT, Pollack HA, Andrews CM, Abraham AJ, 2020. Are Policy Strategies for Addressing the Opioid Epidemic Partisan? A View from the States. J. Health Polit. Policy Law 45, 277–309. 10.1215/03616878-8004886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffajee RL, Frank RG, 2018. Making the Opioid Public Health Emergency Effective. JAMA Psychiatry 75, 767–768. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider-Markel DP, 2001. Policy Diffusion as a Geographical Expansion of the Scope of Political Conflict: Same-Sex Marriage Bans in the 1990s. State Polit. Policy Q 1, 5–26. 10.1177/153244000100100102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harm Reduction Coalition [WWW Document], 2020. . Spirit Harm Reduct. Toolkit Communities Faith Facing Overdose. URL https://harmreduction.org/issues/harm-reduction-basics/spirit-of-harm-reduction-a-toolkit-for-communities-of-faith-facing-overdose/ (accessed 12.29.20). [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Hart MZ, 2019. Opioid crisis: Another mechanism used to perpetuate American racism. Cultur. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol 25, 6–11. 10.1037/cdp0000260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M, 2020a. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2019 (NCHS Data Brief No. 394) National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M, 2020b. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2018 (NCHS Data Brief No. 356). National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine MA, Kuo M, Buxton JA, Balshaw R, Otterstatter M, Macdougall L, Milloy M-J, Bharmal A, Henry B, Tyndall M, Coombs D, Gilbert M, 2019. Modelling the combined impact of interventions in averting deaths during a synthetic-opioid overdose epidemic. Addiction 114, 1602–1613. 10.1111/add.14664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MR, Novitch MB, Sarrafpour S, Ehrhardt KP, Scott BB, Orhurhu V, Viswanath O, Kaye AD, Gill J, Simopoulos TT, 2019. Government Legislation in Response to the Opioid Epidemic. Curr. Pain Headache Rep 23, 40. 10.1007/s11916-019-0781-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishore S, Hayden M, Rich J, 2019. Lessons from Scott County — Progress or Paralysis on Harm Reduction? N. Engl. J. Med 380, 1988–1990. 10.1056/NEJMp1901276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambdin BH, Davis CS, Wheeler E, Tueller S, Kral AH, 2018. Naloxone laws facilitate the establishment of overdose education and naloxone distribution programs in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 188, 370–376. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macinko J, Silver D, 2015. Diffusion of Impaired Driving Laws Among US States. Am. J. Public Health 105, 1893–1900. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson D, 2020. The Spread of Policy Diffusion Studies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, 1990-2018. Am. Polit. Sci. Assoc. Prepr 10.33774/apsa-2020-csnt6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mauri AI, Townsend TN, Haffajee RL, 2020. The Association of State Opioid Misuse Prevention Policies With Patient- and Provider-Related Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Milbank Q. 98, 57–105. 10.1111/1468-0009.12436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan C, Lambdin BH, Ali MM, Mutter R, Davis CS, Wheeler E, Pemberton M, Kral AH, 2018. Opioid-overdose laws association with opioid use and overdose mortality. Addict. Behav 86, 90–95. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintrom M, 1997. Policy Entrepreneurs and the Diffusion of Innovation. Am. J. Polit. Sci 41, 738. 10.2307/2111674 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney CZ, Lee M-H, 1995. Legislative Morality in the American States: The Case of Pre-Roe Abortion Regulation Reform. Am. J. Polit. Sci 39, 599. 10.2307/2111646 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadelmann E, LaSalle L, 2017. Two steps forward, one step back: current harm reduction policy and politics in the United States. Harm. Reduct. J 14, 37. 10.1186/s12954-017-0157-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, E., 2017. Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use. 10.17226/24781 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Netherland J, Hansen HB, 2016. The War on Drugs That Wasn’t: Wasted Whiteness, “Dirty Doctors,” and Race in Media Coverage of Prescription Opioid Misuse. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 40, 664–686. 10.1007/s11013-016-9496-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo B, Taylor J, Caulkins J, Reuter P, Kilmer B, n.d. The dawn of a new synthetic opioid era: the need for innovative interventions. Addiction n/a. 10.1111/add.15222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center [WWW Document], 2014. .Relig. Am. US Relig. Data Demogr. Stat URL https://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/ (accessed 12.21.20).

- Pitt AL, Humphreys K, Brandeau ML, 2018. Modeling Health Benefits and Harms of Public Policy Responses to the US Opioid Epidemic. Am. J. Public Health 108, 1394–1400. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescription Drug Abuse Surveillance System [WWW Document], 2017. . Naloxone Overdose Prev. Laws URL http://pdaps.org/datasets/laws-regulating-administration-of-naloxone-1501695139 (accessed 12.21.20).

- Rees DI, Sabia JJ, Argys LM, Dave D, Latshaw J, 2019. With a Little Help from My Friends: The Effects of Good Samaritan and Naloxone Access Laws on Opioid-Related Deaths. J. Law Econ 62, 1–27. 10.1086/700703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM, 2003. Diffusion of innovations, 5th ed. ed. Free Press; Collier Macmillan, New York: London. [Google Scholar]

- Shipan CR, Volden C, 2008. The Mechanisms of Policy Diffusion. Am. J. Polit. Sci 52, 840–857. 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00346.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smart R, Pardo B, Davis CS, 2020. Systematic review of the emerging literature on the effectiveness of naloxone access laws in the United States. Addiction add.15163. 10.1111/add.15163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szott K, 2020. ‘Heroin is the devil’: addiction, religion, and needle exchange in the rural United States. Crit. Public Health 30, 68–78. 10.1080/09581596.2018.1516031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tempalski B, Flom PL, Friedman SR, Des Jarlais DC, Friedman JJ, McKnight C, Friedman R, 2007. Social and Political Factors Predicting the Presence of Syringe Exchange Programs in 96 US Metropolitan Areas. Am. J. Public Health 97, 437–447. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau, 2011. The Black Population: 2010 [WWW Document]. U. S. Census Bur URL https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2011/dec/c2010br-06.html (accessed 3.20.21).

- Volden C, 2017. Policy Diffusion in Polarized Times: The Case of the Affordable Care Act. J. Health Polit. Policy Law 42, 363–375. 10.1215/03616878-3766762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volden C, 2006. States as Policy Laboratories: Emulating Success in the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Am. J. Polit. Sci 50, 294–312. 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00185.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JL, 1969. The Diffusion of Innovations among the American States. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev 63, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, Quinn E, Doe-Simkins M, Sorensen-Alawad A, Ruiz S, Ozonoff A, 2013. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ 346, f174–f174. 10.1136/bmj.f174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner J, Murphy SM, Behrends C, 2019. Expanding Access to Naloxone: A Review of Distribution Strategies. Penn LDI/CHERISH Issue Brief. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ, 2015. Opioid Overdose Prevention Programs Providing Naloxone to Laypersons — United States, 2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 64, 631–635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H, Davis NL, 2020. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2017–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 69. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wipfli HL, Fujimoto K, Valente TW, 2010. Global Tobacco Control Diffusion: The Case of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Am. J. Public Health 100, 1260–1266. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.167833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]